Abstract

Female entrepreneurship drives tourism development in resource-scarce destinations but little is known about why local women engage in business and what determines their success in a time of a life event crisis. This knowledge is important as it can support policies on regional regeneration and poverty alleviation. This study draws upon the Bourdieu's model of practice with its notions of capital, agents, field, and habitus to examine the experiences of women running tourism enterprises in a destination with the legacy of an anthropogenic environmental disaster, the Aral Sea region. Semi-structured interviews with women entrepreneurs in Uzbekistan (n = 18) and Kazakhstan (n = 15) showcase prevalence of the necessity-based and extrinsic motivations in a time of crisis. Interviews also demonstrate the importance of social capital women entrepreneurs built with such agents of entrepreneurial practice as family, friends, policymakers, employees, and competitors. The original contribution of the study is in revealing how local cultural traditions reinforce various types of capital, strengthen the field of knowledge, and shape habitus of women entrepreneurs in critical times. Another original contribution is in highlighting how the experience of past life event crises has aided in psychological coping of women tourism entrepreneurs during COVID-19.

Introduction

Female entrepreneurship contributes significantly to socio-economic prosperity, especially in countries of the Global South (Ramadani et al., Citation2015), where it often provides the only source of household income, thus reducing local poverty and inequality (Rosca et al., Citation2020). For example, in Morocco, women entrepreneurs run hospitality enterprises in remote, rural destinations employing a considerable number of local people (Alonso-Almeida, Citation2012). Likewise, female entrepreneurship represents an important driver of the tourism industry in Uganda whereby women enhance the socio-economic well-being of local communities by providing employment opportunities, especially to those considered disadvantaged, such as residents of rural areas (Katongole et al., Citation2013). Lastly, evidence from Kenya pinpoints how women entrepreneurs recycle solid waste, thus not only conserving the environment but also providing a means of livelihood for local low-income groups (Climate and Clean Air Coalition, 2018).

These examples showcase women entrepreneurs as enablers of the world’s transition towards the goal of socio-economic and even environmental sustainability, particularly in disadvantaged and resource-scarce communities (Kimbu & Ngoasong, Citation2016). Empowerment of women to develop and maintain entrepreneurial skills has therefore become a policymaking priority (Foss et al., Citation2019). Female entrepreneurship as a driving force for achieving the goals of sustainable development has been repeatedly recognised by many (inter)national organisations, including the United Nations (CitationFigueroa-Domecq et al., 2022).

Scholarly interest in women entrepreneurs is growing. The systematic review by Cardella et al. (Citation2020) identifies 2848 articles on female entrepreneurship, with most published in the last decade. The growth in research is attributed to the need for academics to support the global and national political agendas on facilitating female entrepreneurship (Gherardi, Citation2015). Research can inform the design of more effective policymaking interventions by reinforcing the understanding of what motivates women to engage in business and how this motivation can be sustained (Cavada et al., Citation2017). Ultimately, research on gender and sustainable entrepreneurship can underpin social policies at various levels of decision-making (Foss et al., Citation2019). In the context of this study social policies are understood as the policies encouraging social and economic participation among groups that are either underrepresented or seen as vulnerable in local communities (Diekmann & McCabe, Citation2011). Participation of women in the labour market remains challenging, especially from the perspective of equal opportunities, levels of remuneration and work-life balance (European Commission, 2022). These challenges are particularly pronounced in certain parts of the world, such as Central Asia, where participation rates of female labour force have been established as very low (Khitarishvilli, Citation2016). Hence, research on gender and sustainable entrepreneurship can contribute to social policies designed to widen participation of women in local labour markets, thus promoting a more active role played by women in local communities.

Despite the welcomed growth in academic investigations on women entrepreneurs, some critical knowledge gaps remain. First, there are limited studies on female entrepreneurship in emerging economies (Tajeddini et al., Citation2017). The systematic review by Correa et al. (Citation2021) identifies 77 articles targeting women entrepreneurs in developing countries. This is only 3% of the total number of publications on female entrepreneurship as revealed by the broader review of Cardella et al. (Citation2020). Local contexts determine the motives of women to become entrepreneurs and affect their business success (Xheneti et al., Citation2019). As Ribeiro et al. (Citation2021) posit, the findings of “western” research on women entrepreneurs cannot be directly applied to other contexts due to variations in resource availability and governance models. This calls for a stream of nuanced studies on women entrepreneurs in emerging economies.

Second, sectoral coverage of research on female entrepreneurship is restricted. While many studies have considered women entrepreneurs in manufacturing, education, and retail (Kakabadse et al., Citation2018), fewer investigations have been undertaken in tourism (Cole, Citation2018). This is concerning because local economies, especially in developing countries, are dependent on tourism revenues (Thirumalesh Madanaguli et al., Citation2021). Further, the review of female entrepreneurship research in emerging economies by Correa et al. (Citation2021) identifies only six studies focusing on micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). This is a key drawback as MSMEs represent most business profiles in developing countries, especially within the tourism sector (Kimbu et al., Citation2021).

Lastly, an important research gap is the yet insufficient understanding of women motivations to become entrepreneurs alongside the strategies women adopt to sustain this motivation under variable external conditions (Correa et al., Citation2021). More specifically, studies have paid little attention to such external disruptors as life event crises as enablers of female entrepreneurship (Nakamura & Horimoto, Citation2020). Although investigations have started looking at women entrepreneurs in critical times, these investigations are predominantly concerned with the COVID-19 pandemic (Manolova et al., Citation2020). Studies do not consider female entrepreneurship in the context of localised, but prolonged, life event crises (Bastian et al., Citation2018). This is an important theoretical drawback because crises, while being destructive for traditional business models and damaging for local communities, can spark creativity (Monllor & Murphy, Citation2017). Empirical research on women entrepreneurs in localities affected by the legacy of disastrous events are therefore needed (Nakamura & Horimoto, Citation2020). Such studies can provide useful insights into how female entrepreneurship emerges and sustains in the circumstances which are far from normal (Asgary et al., Citation2012).

Research on female entrepreneurship in the context of life event crises becomes particularly important considering rapidly unfolding climate change that will intensify anthropogenic disasters in destinations across the world (Filimonau & De Coteau, Citation2020). These disasters will irreversibly affect local (environmental and socio-economic) conditions and resources, thus hindering livelihoods and hampering business prospects of residents (Grube & Storr, Citation2018). It is important to understand how/if women entrepreneurs can foster the adaptation and revitalisation of local communities that may or will have experienced a prolonged effect of a disastrous event (Khalil et al., Citation2020).

This study has set to examine the phenomenon of female entrepreneurship in a destination affected by the legacy of an anthropogenic environmental disaster, the Aral Sea region. The study draws upon such theories of social sciences and business management as Maslow’s Theory of Needs, Theory of Social Capital, Bourdieu’s Practice Theory, and Social Practice Theory to understand what motivates women to become tourism entrepreneurs in unfavourable external circumstances and how this motivation is sustained. The study evaluates factors contributing to business success of women tourism entrepreneurs in the context of a life event crisis. Ultimately, the study responds to the call for more empirical investigations of women entrepreneurs running tourism MSMEs in emerging economies.

Literature review

Motivations of women entrepreneurs

Motivations of women to become entrepreneurs can be explained by Maslow’s Theory of Needs (Lee, Citation1996). This theory advocates that people are motivated to satisfy their needs in a hierarchical order i.e., starting with basic, or lower-order, towards more sophisticated, or higher-order, needs. The basic needs are attributed to moneymaking required for immediate household support (Ganesan et al., Citation2002). The more sophisticated needs usually occur once the basic needs have been satisfied. For example, once the enterprise becomes sufficiently profitable for comfortable living, women entrepreneurs may begin thinking of other business and personal goals (Winn, Citation2005).

Lee (Citation1996) posits that women entrepreneurs can be driven by such higher-order needs as achievement; affiliation; autonomy; and dominance. Achievement is explained by desire to showcase individualized effort and obtain extra rewards, such as increased business profits or public recognition (Sadi & Al-Ghazali, Citation2010). Affiliation is associated with willingness to help local communities or build close(r) relationships with them (Alonso-Almeida, Citation2012). Autonomy (sometimes defined as independence) suggests desire to be non-dependent on others’ opinions or resources (Tajeddini et al., Citation2017). Lastly, dominance is attributed to willingness to execute power, become a leader, and control others, such as employees (Kourtesopoulou & Chatzigianni, Citation2021). Importantly, by satisfying these higher-order needs, women entrepreneurs do not only develop their business enterprise, but can also build a stronger “self” (Badzaban et al., Citation2021). This underlines the importance of supporting progression of women entrepreneurs from basic to more sophisticated needs as this will facilitate their professional growth, but also personal development.

One of the main critiques of Maslow’s Theory of Needs when applied to the context of entrepreneurial motivation is the assumption of linearity of needs i.e., if basic needs have not been met, then an entrepreneur is unlikely to move on to satisfy more sophisticated needs (Cavada et al., Citation2017). Empirical evidence from the field of female entrepreneurship demonstrates that the more sophisticated needs can in fact coexist with the basic needs. For instance, Nakamura and Horimoto (Citation2020) show that women entrepreneurs in Japan make money while aiming to enhance the well-being of local communities. Similar findings are revealed by a study of women entrepreneurs in Morocco (Alonso-Almeida, Citation2012). Another critique of Maslow’s Theory of Needs is its ethnocentrism (Hofstede, Citation1984) as its ideas originated in the west, thus not accounting for the potential effect of other factors, most notably national culture, on entrepreneurial motivation in other geographies. This highlights the need to better understand what motivates women entrepreneurs in non-western contexts.

An alternative, but related, approach to explaining women motivations to establish a business enterprise categorises the drivers of entrepreneurship as necessity- and opportunity-based (Monllor & Murphy, Citation2017). Necessity-based entrepreneurship is driven by desire to satisfy basic needs. It emerges in response to a dire situation, such as poverty (Bastian et al., Citation2018). In contrast, opportunity-driven entrepreneurship is motivated by the option to either increase business profits or satisfy higher-order needs. Necessity-based entrepreneurship can thus be more applicable to women in developing countries due to high poverty levels (Kimbu & Ngoasong, Citation2016). Opportunity-based entrepreneurship is arguably more typical for women in developed economies whereby there is more money available and/or this money is easier to access (Correa et al., Citation2021). Opportunity-based entrepreneurship can also be observed in developing countries; however, it largely occurs among the established entrepreneurs i.e., women who have already satisfied their basic needs. For example, Alonso-Almeida (Citation2012) showcases how experienced women entrepreneurs in Morocco aim to contribute to societal wellbeing rather than make money.

In summary, motivations of women entrepreneurs are linked to life necessities and opportunities. Rewards, such as profit-making and recognition, represent important extrinsic motivators and so do various intrinsic factors, such as desire to help communities. Motivators differ depending on the local context in which women-run enterprises operate.

Determinants of successful female entrepreneurship

Multiple factors are associated with success and failure of women entrepreneurs (Savage et al., Citation2022). These factors include socio-demographic characteristics (for example, education level), psychological traits (for instance, personal risk perception) and professional features (for example, previous managerial and occupational skills and experience) (Huarng et al., Citation2012). These numerous factors and the significant impact of local political and social-economic settings have led Bull and Willard (Citation1993) to argue that establishing a universal, global model for (female) entrepreneurship is unlikely. Instead, localised studies are necessitated examining the determinants of female entrepreneurship in specific regions and economic sectors (Bastian et al., Citation2018).

Among other determinants, personal connections are critical for women entrepreneurs (Badzaban et al., Citation2021). Theory of Social Capital explains this by the need to have large social networks for initial resource acquisition and marketing (Farr‐Wharton & Brunetto, Citation2007). These networks can also be used if business performance is poor and external support is required (Yetim, Citation2008). Positive association exists between the size of social networks of women entrepreneurs and their business success, especially in developing countries (Thirumalesh Madanaguli et al., Citation2021). This is because local communities tend to rely on interpersonal relationships in difficult times. For example, Lukiyanto and Wijayaningtyas (Citation2020) demonstrate how the local cultural trait of Gotong royong, or communal assistance, in Indonesia supports MSMEs in a time of crisis.

Bourdieu’s Practice Theory (Bourdieu, Citation2005) reiterates importance of social capital for women entrepreneurs but highlights further determinants of business success. Three additional types of capital are introduced: economic, cultural, and symbolic (Cakmak et al., Citation2018). Economic capital exemplifies availability of resources to run a business, such as personal savings for initial investment or business development (Aldás-Manzano et al., Citation2012). Cultural capital represents the extent of women entrepreneurs’ understanding of the local context in which they choose to operate (Kungwansupaphan & Leihaothabam, Citation2016). For instance, a non-local entrepreneur may receive limited support towards their business from residents. Lastly, symbolic capital explains how women entrepreneurs are perceived by the local people (De Clercq & Voronov, Citation2009). Better perceptions increase loyalty and patronage.

Another determinant of female entrepreneurship in Bourdieu’s Practice Theory is the notion of field which explains the context of business activity (Bourdieu, Citation2005). Women entrepreneurs should know the field in which they choose to operate, be it geographical (for example, a specific destination) or sectoral (for instance, tourist accommodation). Better knowledge of the field correlates with business success (Huarng et al., Citation2012). Further, women entrepreneurs should know the agents within the field such as clients, suppliers, and policymakers (Forson et al., Citation2014). For example, if a woman entrepreneur chooses to run a restaurant, but has no knowledge of local food preferences, then their business venture is likely to fail. Likewise, if a woman entrepreneur has no support of their business from local authorities, then their enterprise becomes challenging to run.

Bourdieu’s Practice Theory also uses the notion of habitus to explain the socially embedded norms, values, attitudes, and behaviours shared by people with similar backgrounds (Bourdieu, Citation2005). Habitus combines all types of capital and implies knowledge of the field alongside its agents (Cakmak et al., Citation2018). Habitus is developed throughout lifetime and becomes a form of identity (Cakmak et al., Citation2021). For example, once women start associating themselves with a class of entrepreneurs, they develop specific attitudinal and behavioural patterns determining how business resources are used and agents are dealt with. For instance, positive association has been established between women’s entrepreneurial experience and their risk propensity (Brindley, Citation2005). (More) experienced entrepreneurs are more likely to accept risks as they better understand their domain of business and have established (better) links with the key actors of relevance within this domain to be used with risk minimisation purposes.

Bourdieu’s Practice Theory has informed Social Practice Theory (Reckwitz, Citation2002) which highlights other determinants of female entrepreneurship through the notions of meaning, competency, and material. The meaning factor requires women entrepreneurs to understand why they have chosen to engage in business and what their business aims to achieve. For example, some women run tourism and hospitality enterprises purely for moneymaking, but some aim to help the local people (Alonso-Almeida, Citation2012). The competency factor implies possession of appropriate “know how.” For instance, marketing skills are critical but not always available for tourism entrepreneurs (Tajeddini et al., Citation2017). Lastly, the material factor necessitates access to resources. In the context of tourism these resources are represented by money, but also adequate road infrastructure, for example (Ribeiro et al., Citation2021). The extent to which all three factors of Social Practice Theory are fulfilled by women entrepreneurs determines the level of success of their business enterprise.

The ideas of Bourdieu are criticised for being overly deterministic i.e., they assume that all (social or work) events are determined by previously existing causes (Spigel, Citation2013). This has interesting implications for the entrepreneurial context. An entrepreneur is someone who starts a business afresh, thus implying high probability of risk. Although entrepreneurs can learn from previous causes of (un)successful business or social ventures, they do not necessarily possess first-hand experience of running a business enterprise (Trivedi & Petkova, Citation2021). This calls for a better understanding of the extent to which the Bourdieu’s ideas can (not) apply to the entrepreneurial context given their deterministic nature. Another critique of Bourdieu is his limited consideration of gender (Thorpe, Citation2010). While the principles outlined in the Bourdieu’s work have been found relevant for men, there remains little research on the applicability of Bourdieu’s Practice Theory to women (Sklaveniti & Steyaert, Citation2020). This highlights female entrepreneurship as an interesting research object in the context of Bourdieu’s studies.

In summary, to succeed, women entrepreneurs should understand the field in which they choose to operate alongside its agents. Women entrepreneurs need to link to these agents to build various types of capital. Lastly, women entrepreneurs should recognize what their business is about, possess appropriate skills to run it and have access to necessary resources.

Female entrepreneurship in a time of crisis

The relationship between entrepreneurship and crises represents an emerging research domain in risk, crisis and disaster studies; however, this relationship remains under-examined in the context of tourism management, especially from the gender perspective (Portuguez Castro & Gómez Zermeño, Citation2021). Research suggests that crises have significant negative impacts on entrepreneurial activity at a destination level (Ritchie & Jiang, Citation2021). However, crises can also motivate tourism entrepreneurs to invest in business to make it more resilient (Dahles & Susilowati, Citation2015). Crises can even promote “disaster entrepreneurship” in specific destinations whereby the affected communities and businesses mobilise resources to overcome the negative impacts of disastrous events (Badoc-Gonzales et al., Citation2022).

COVID-19 has become the impetus for generating a high volume of research on female entrepreneurship in a time of crisis. The research has considered the negative impact of the pandemic on women-run business enterprises (Grandy et al., Citation2020), examined the learning experiences of women entrepreneurs (Afshan et al., Citation2021), and investigated their coping strategies (Hennekam & Shymko, Citation2020). Studies have not however been concerned specifically with women tourism entrepreneurs (Frederick & Adam, Citation2022) which is a major shortcoming given the detrimental effect of COVID-19 on the sector.

The literature on female entrepreneurship in a time of the pandemic has emphasised that disasters and crises can impose not only the negative but also positive effects. This is aligned with the postulates of Chaos Theory and the ideas of Nietzsche (“from Chaos comes order”) which highlight that a new organisational paradigm can emerge from the relationships disrupted by chaos (Bull & Willard, Citation1993). Disasters and crises offer scope for innovation and creativity (Portuguez Castro & Gómez Zermeño, Citation2021) as demonstrated by the emergence of new business models in tourism during COVID-19, such as ghost kitchens (Cai et al., Citation2022) and virtual wine tasting tours (Wen & Leung, Citation2021). Further, Theory of Diffusion of Innovation suggests that new ideas can penetrate society prompter in a time of crisis (Dibra, Citation2015). This is because, in critical situations, people are inclined to overcome such traditional barrier to entrepreneurship as fear of the new (Afshan et al., Citation2021).

When translated onto the topic of entrepreneurship, this suggests that disasters and crises can trigger the necessity-based and opportunity-based motivations of women entrepreneurs (Monllor & Murphy, Citation2017). A short-lived disastrous event, such as a hurricane, prompts the necessity-based motivation which forces women entrepreneurs to help their households and local communities (Basco, Citation2015). However, if a disastrous event has a prolonged effect, then the opportunity-based motivation may occur (Linnenluecke & McKnight, Citation2017). For instance, Chernobyl and Fukushima, with their legacy of anthropogenic disasters, have gradually become popular tourist destinations in the result of largely opportunistic entrepreneurial activity (Jang et al., Citation2021; Yankovska & Hannam, Citation2014).

Nakamura and Horimoto (Citation2020) highlight the need to study female entrepreneurship in a time of a life event crisis. Using the case of disasters in Japan, they develop a conceptual framework to understand what motivates women to become entrepreneurs in unfavourable environmental conditions and what factors contribute to sustaining their entrepreneurial motivation. Nakamura and Horimoto (Citation2020), but also Afshan et al. (Citation2021), argue that a disastrous event triggers a critical reassessment of the physical and emotional capabilities among prospective women entrepreneurs whereby they decide how they can accelerate the recovery. Confidence of women in their business abilities is more important for starting an enterprise in a time of a life event crisis than any other factor, including money (Hennekam & Shymko, Citation2020). As for the barriers to female entrepreneurship in a time of a life event crisis, Nakamura and Horimoto (Citation2020) highlight the critical role of under-developed social networks, while Villaseca et al. (Citation2021) also showcase prejudices over gender roles in moneymaking and access to finance in local societies, especially in developing countries.

The conceptual framework by Nakamura and Horimoto (Citation2020) highlights the relevance of Theory of Social Capital, Bourdieu’s Practice Theory and Social Practice Theory for understanding the phenomenon of female entrepreneurship in a time of a life event crisis. For instance, it highlights the criticality of the meaning factor as defined by Social Practice Theory in women’s decisions to run a business enterprise during unfavourable conditions. Likewise, Villaseca et al. (Citation2021) reveal society-driven gender prejudices as a barrier to women entrepreneurship which corresponds to the field, agents and habitus factors as defined by Bourdieu.

While being seminal in that it shed light on the phenomenon of female entrepreneurship in a time of a life event crisis, the study by Nakamura and Horimoto (Citation2020) was conceptual. Further, it did not consider the contexts of prolonged crises i.e., disastrous events with a legacy, such as Chernobyl. Lastly, Nakamura and Horimoto (Citation2020) did not focus on women entrepreneurs in tourism. This current study will adopt the conceptual framework of Nakamura and Horimoto (Citation2020) and draw upon the theoretical foundations discussed earlier to understand the phenomenon of female entrepreneurship in critical times. The focus will be on women-run tourism MSMEs in a destination with the legacy of a disaster, the Aral Sea region.

The local context: female entrepreneurship in the Aral Sea region

The Aral Sea region (), shared by Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, is often portrayed as home to one of the planet’s worst anthropogenic environmental disasters (Loodin, Citation2020). The desiccation of the Aral Sea, formerly the world's fourth largest lake, caused predominantly by agricultural activities, began in the 1960s (Micklin, Citation1988). By the 2010s the Aral Sea largely dried up which directly affected 3.5 million people, mostly fishermen, who provided over half of regional economic activity prior to the disaster (Ataniyazova, Citation2013). Reduced employment opportunities prompted migration from the region (Loodin, Citation2020).

Figure 1. The studied region of the Aral Sea. Source: Nations Online (Citation2022).

In 2010s the Aral Sea region emerged as a popular tourism destination. The sinister past of the region and its fishing industry’s heritage attracted visitors engaging in dark, eco-, adventure and heritage tourism activities (Saidmamatov et al., Citation2020). For example, in Uzbekistan, tourists are attracted by the lower Amudarya state’s biosphere reserve, the ship cemetery in Muynak, the ancient fortresses in Khorezm, and the Nukus Art Museum (Saidmamatov et al., Citation2021). In 2019, only in Uzbekistan, over 2.5 million tourists visited the Aral Sea region which signified a more than two-fold growth compared to 2018 (Uzbek Tourism, 2019). Over 20% of visitors to the region were international, mostly from the neighbouring countries of Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan, but also from Russia, China, Germany and Japan (Matyakubov et al., Citation2021).

Tourism facilitated entrepreneurship among women. For example, in Uzbekistan, almost 50% of tourism enterprises in the Aral Sea region are run by women (personal communication with a representative from the Uzbek Tourism, November 2021). While there is no regional figure for Kazakhstan, country-wide statistics suggest that 87% of business owners in the national tourism sector are women (personal communication with a representative from the Kazakh Tourism, December 2021). Most women-run business enterprises in the Aral Sea region are MSMEs represented by small-sized hotels, guest houses, transport and foodservice providers, tour guides, crafts, and souvenir shops (Matyakubov et al., Citation2021).

The governments of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan have committed to supporting women entrepreneurs in the Aral Sea region. This commitment is driven by the recognition of limited economic alternatives within the region whereby tourism represents the only vehicle of regeneration and poverty alleviation (Saidmamatov et al., Citation2020). In Uzbekistan, the importance of female entrepreneurship is prescribed at the top level of policymaking i.e., in the presidential resolution "On further measures to improve the system of support and ensure active participation of women in the life of society" of the 5th of March 2021. As part of this resolution, the national government simplified the process of registering women-run enterprises and provided dedicated grant aid (personal communication with a representative from the Uzbek Tourism, November 2021).

In Kazakhstan, female entrepreneurship is supported by a range of governmental initiatives, such as The Roadmap of 2025 and The Programme of Development of Effective Occupation and Entrepreneurship “ENBEK” (2017-2021). As part of these initiatives, women entrepreneurs can access business subsidies (personal communication with a representative from the Kazakh Tourism, December 2021). In Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan women tourism entrepreneurs are also supported with grants from UNESCO.

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) were registered in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan aiming to promote female entrepreneurship. For example, in Uzbekistan, there are over 500 such NGOs. The largest is the “Women's Committee of Uzbekistan” which has 214 territorial divisions, including 14 in the Aral Sea region (personal communication with a representative from the Uzbek Tourism, November 2021). In Kazakhstan, female entrepreneurship is supported by such NGOs as the “Fund of Support of Women Entrepreneurs,” “The Council of Businesswomen,” and The Fund “Social Dynamics” (personal communication with a representative from the Kazakh Tourism, December 2021).

The research gap

In summary, women account for many tourism entrepreneurs in the Aral Sea region. Little is however known about the motivation of local women to engage in tourism business. The determinants of successful female entrepreneurship in this unique destination which has the legacy of one of the planet’s worst anthropogenic environmental disasters also remain unexplored.

This study will draw upon theories of motivation (Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs), practice and capital (Theory of Social Capital, Bourdieu’s Practice Theory, Social Practice Theory) to explore what has prompted tourism entrepreneurship among local women in the Aral Sea region and what has aided them to succeed in doing business despite the destination’s grim past and scarcity of resources. By bridging these theories, the study aims to not only add to the yet limited body of knowledge on women tourism entrepreneurs in developing countries, but also provide insights into the phenomenon of female tourism entrepreneurship in a time of a life event crisis. This can be useful from the perspective of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic which continues to disrupt MSMEs in destinations around the world. This can also be useful in the context of other disasters and crises, such as climate change. By investigating the phenomenon of female tourism entrepreneurship in light of disastrous events whose magnitude and frequency are likely to intensify in the future, this study will enhance the understanding of copying strategies and identify the determinants of success among women tourism entrepreneurs in developing countries and beyond. This will build psychological and business resilience and contribute to the socio-economic sustainability of tourism businesses and their host local communities.

Methodology

Although the phenomenon of female entrepreneurship has attracted significant research interest to date, there are limited studies on the experiences of women tourism entrepreneurs in a time of a life event crisis, such as an anthropogenic disaster. This underlines the exploratory nature of the current project which dictates the selection of qualitative research methods for primary data collection and analysis. Qualitative research is best suited for under-examined social phenomena in immature study contexts (Matthews & Ross, Citation2014).

Data were collected by the method of in-depth, semi-structured interviews. Focus groups were considered but abandoned due to logistical difficulties of arranging mutually suitable meeting times for busy women entrepreneurs. Semi-structured interviews were chosen because of their design flexibility enabling researchers to amend an interview schedule at short notice considering the emerging research needs (Ghauri & Gronhaug, Citation2005).

Interview questions were developed based on the literature review. The seminal work by Nakamura and Horimoto (Citation2020) was used as a basis supplemented with the findings from Cardella et al. (Citation2020), Correa et al. (Citation2021), Kimbu and Ngoasong (Citation2016), Monllor and Murphy (Citation2017), and Thirumalesh Madanaguli et al. (Citation2021). The interview schedule consisted of four sections aiming to establish the (1) motivations of women to start a tourism enterprise in a time of a life event crisis; (2) determinants of successful entrepreneurship in difficult times; (3) experiences of running a business during unfavourable conditions. A set of questions also aimed to understand (4) the impact of COVID-19 on women entrepreneurs as another life event crisis on top of the Aral Sea’s desiccation.

The interview schedule was developed in English, the language of the literature review. It was professionally back translated into Uzbek, Kazakh and Russian i.e., the languages commonly spoken in the Aral Sea region. The schedule was reviewed for content and face validity by four academics majoring in tourism/hospitality management and small family business. The pilot study involved three women entrepreneurs in Uzbekistan and two in Kazakhstan. Minor changes were applied to the wording of interview questions for clarity of expression following the pilot feedback. A copy of the final schedule is provided in Supplementary Material (Appendix 1).

Study participants were purposively recruited among women entrepreneurs whose tourism enterprises operated in the Aral Sea region of Uzbekistan (Nukus, Kungrad, Muynak) and Kazakhstan (Aralsk, Ayteke Bi and Kyzylorda). The inclusion of women entrepreneurs from both Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan was considered beneficial for a comparative analysis. Despite being former Soviet Union’s republics, both countries have developed unique political and socio-economic contexts. Comparing the experiences of women entrepreneurs in two countries was seen as an opportunity to reveal the effect of the local context which Ribeiro et al. (Citation2021) highlight as potentially significant.

Access to study participants was facilitated by the local NGOs working with women entrepreneurs in the Aral Sea region of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. These NGOs assisted the researchers in identifying and short-listing information-rich cases among their members (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). These members were contacted by email or phone call explaining the project and requesting participation. This was followed on with another phone call aiming to provide further project’s details, answer questions, and assure prospective participants in the study’s anonymity. Only business enterprise owners were invited to participate. During recruitment, effort was made to achieve an inclusive sample in terms of its sub-sectoral coverage. To this end, women entrepreneurs representing MSMEs with various specialisms (for example, hotel, restaurant, tour operator, retail) were recruited.

Interviews were administered face-to-face on business premises of women-run enterprises in September-October 2021 in Uzbekistan and October-November 2021 in Kazakhstan. Interviews were conducted by members of the research team who spoke Uzbek, Kazakh and Russian fluently. No financial incentives were offered for participation. Prior to interviewing, prospective study participants were reassured in complete anonymity of the study’s findings, thus reducing the effect of social desirability bias (Chung & Monroe, Citation2003). The sample size was determined by perceived saturation which was detected with 18 interviews in Uzbekistan and 15 interviews in Kazakhstan. Although saturation is no longer considered important in qualitative research (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021), Thomson (2010 cited by Marshall et al., Citation2013) suggests that it is normally reached with 10-30 interviews which this study confirms. Interviews lasted, on average, 48 minutes; they were recorded, transcribed, and professionally translated by the research team members. presents the study’s participants.

Table 1. Study participants (n = 33).

The interview transcripts were analysed thematically by the same members of the research team who conducted interviews following the guidelines by Gibbs (Citation2012). For data trustworthiness, the transcripts were independently read by two members of the research team to establish patterns of meanings (Berg, Citation2009). The raw data were coded deductively following the guidelines by Azungah (Citation2018). Codification was applied independently by two members of the research team. Codification was facilitated by NVivo 12 software, and the draft coding structures were compared and discussed (Jones et al., Citation2013). Data were re-read and re-coded in the case of identified discrepancies in codification (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). Lastly, as suggested by Burnard (Citation1991), the final data coding structures were presented to four volunteers from the study participants. The volunteers were requested to consider the results of data codification and confirm their meaningfulness.

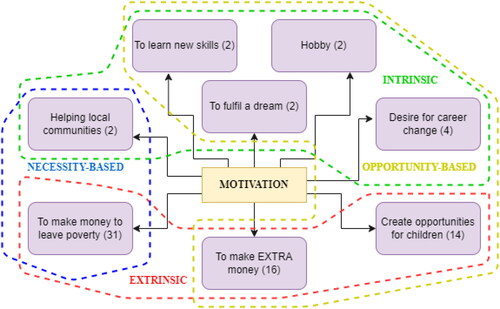

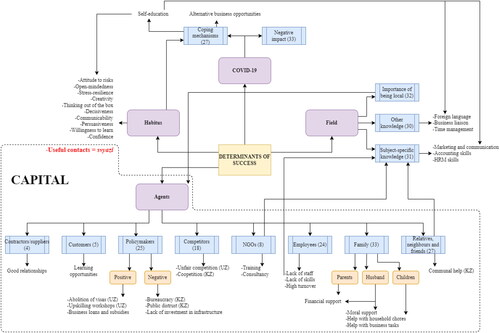

The guidelines provided by Guest et al. (Citation2006) were followed when presenting the final data coding structures ( and ). Guest et al. (Citation2006) propose to focus on so-called high frequency codes in data codification i.e., the codes attracting the largest number of mentions in interview transcripts. Contrasting this approach, the final data coding structures reported in the current study contained all codes regardless of their mentioned frequency. This is to account for any unpopular, but potentially significant, viewpoints, opinions and perspectives that can be easily overlooked when applying the high frequency codes approach recommended by Guest et al. (Citation2006).

Figure 2. Results of data coding: Motivation of women entrepreneurs in the Aral Sea region.

Legend: Light yellow box presents the theme. Light violet boxes present the sub-themes. Red coloured dashed lines indicate extrinsic motivators. Green coloured dashed lines indicate intrinsic motivators. Blue coloured dashed lines indicate necessity-based motivators. Dark yellow coloured dashed lines indicate opportunity-based motivators. Figures in brackets reflect the number of times a specific code was mentioned by the study participants i.e., frequency of mentioning.

Findings

Motivation

Moneymaking was the main motivator for the study participants to start an enterprise in a time of a life event crisis (). High regional unemployment driven by the Aral Sea’s desiccation prompted women to seek alternative ways of generating income for livelihood support. Witnessing increasing numbers of tourist arrivals to the region, women recognised this as a source of earning money in a time of extreme need.

Only a small number of women entrepreneurs were concerned with helping local communities (). The study participants would often refer to the “…need to look after [their] own families first before helping others” (UZ3) as the reason why “helping communities” was not a strong enough motivator. Some women entrepreneurs acknowledged that, only having fulfilled their immediate financial needs after years of business activity, they would think about broader societal benefits of their enterprise. This showcases the necessity-based motivation as the key driver of female tourism entrepreneurship in a time of a life event crisis.

Less than a half of the study participants spoke about various opportunities as their main motivator (). Among these opportunities, the (1) desire to support children financially after parents’ death/retirement; (2) willingness to increase business profits; and (3) desire to pursue a new career were cited most frequently. Combined with moneymaking as the key motivator, this indicates the prevalence of extrinsic motivations among women entrepreneurs in the Aral Sea region:

When I started, I didn’t think of any opportunities. I needed to survive, earn money to buy food. When you’re hungry, it’s difficult to think of something else, you know… As I’ve earned enough, I’ve started thinking of the opportunities. Now I’m thinking of how my business will benefit my children; I’m also thinking where else to invest to build equity… (KZ15)

Determinants of success

Agents and capital

The study participants discussed various agents and different types of capital as the determinants of entrepreneurial success in a time of a life event crisis. Immediate family was cited as often the only source of economic capital whereby either parents or a husband would help with money for initial investment (). Husband was also considered crucial to provide moral support to women entrepreneurs, but also help them with household duties and occasional business tasks. Children were also mentioned in the context of day-to-day business assistance. Children were considered a crucial agent in terms of knowledge and experience transfer for business legacy.

Figure 3. Results of data coding: Determinants of success for women entrepreneurs in the Aral Sea region.

Legend: Light yellow box presents the theme. Light violet boxes present the sub-themes. Light blue boxes present the codes. Light orange boxes present the sub-codes. Figures in brackets reflect the number of times a specific code was mentioned by the study participants i.e., frequency of mentioning. UZ stands for Uzbekistan and KZ stands for Kazakhstan.

Relatives, neighbours, and friends were considered important in building the capital of women entrepreneurs (). This agent provided informational support, such as by advising on where to locate a hotel or restaurant, thus enhancing the cultural capital. This agent also shared their business skills with women entrepreneurs, such as on how to manage employees or market the enterprise, thus contributing to better knowledge of the field. The role of this agent was particularly important for women tourism entrepreneurs in Kazakhstan which was due to the national cultural tradition of reciprocal communal help to be requested in a time of need:

In Kazakhstan, we have the tradition of Asar which is about helping your neighbours and friends. It’s taught from childhood, especially in small places, like our region. Grandmothers and mothers teach us this, it goes from generation to generation. By helping others, you learn. For example, if our neighbour’s boat breaks down, we help them and, I’m sure, they will help us if needed… (KZ4)

Difficult to say how they [policymakers] support small business. They do offer [business] loans, but it’s extremely difficult to get these. So many institutions need to be involved, and the requirements are so tough. You need to know the right people among them [policymakers] to access finance. I’d better go and ask someone else if I needed money for business development… (KZ7)

You cannot imagine how difficult [it is] to find staff. Young people don’t want to stay here, they go to Tashkent or Bukhara. The remaining folk, they need to be trained, but then they go anyway sooner or later. There is no choice for me but to learn everything myself… (UZ9)

I think it’s part of our culture, it’s our nomadic connections that prevent us from competing with each other. The region is small, we all know each other, we know who does what. Everyone wants to provide a good service as we understand this is in everyone’s best interest. We look at each other and learn… (KZ10)

The field

When describing the field of their business activity, the study participants discussed its three key elements (). First, they spoke about the importance of being local to the Aral Sea region as a means of gaining access to the main agents. Women entrepreneurs emphasised the need to know the local traditions, such as Asar in Kazakhstan, to obtain support and resources. Second, women entrepreneurs recognised the significance of subject-specific knowledge in the field of tourism, such as marketing and communication, but also accounting and human resource management (HRM). HRM knowledge was considered crucial given staff shortages as highlighted earlier. Lastly, women entrepreneurs discussed the significant role of other relevant knowledge to their field, such as foreign languages and business liaison skills:

I’m local, I am born and raised here, so I know who to contact if I needed help. For example, if my guests want fish and I don’t have it, I can call my acquaintance in who is a fisherman, and he’ll deliver that to me in no time. It’s just a matter of explaining to my guest that the fish will come soon. If they aren’t Uzbek, I’ll struggle with that as my English is none. Language is important if you want to be a tourism entrepreneur…(UZ8)

Habitus

The study participants discussed various qualities which they considered essential for entrepreneurs, thus drawing upon the idea of the habitus (). All these qualities were represented by so-called “soft skills,” including creativity, communicability and willingness to learn. Stress resilience was acknowledged as a crucial skill and the study participants claimed to have developed it with time. Many women entrepreneurs suggested that the stress of everyday business tasks was incomparable to the stress of living in a destination with a bleak future, such as the Aral Sea region. Some study participants spoke about how the legacy of the anthropogenic environmental disaster affected their attitude to risks. No risk was considered greater than the one they experienced in the past, which reduced risk aversion of women tourism entrepreneurs, thus encouraging them to pursue endeavours which might have otherwise been seen unacceptable:

When it all started [the desiccation], we lost our jobs. I had to do something to survive even though I feared it wouldn’t work out. Imagine, there was a huge empty building where the town’s department store once was. No one wanted it because it was so big! I bought it to start a hotel business. Big decision, big risk, but no bigger than losing everything we had before (KZ13)

The impact of COVID-19

Lastly, the study participants discussed their entrepreneurial experiences considering COVID-19 (). Although the pandemic negatively affected tourism in the Aral Sea region, women entrepreneurs highlighted various coping strategies they adopted to overcome the consequences. Some women spoke about alternative business avenues they pursued to generate income, such as food delivery and farming. Besides, women highlighted the opportunities provided by COVID-19 to self-reflect upon their business activities, but also invest in self-education (). Many study participants discussed how they learnt English and attended various trainings to better prepare themselves for a post-pandemic future. Importantly, many women highlighted how the environmental disaster they experienced in the past shaped a more optimistic attitude towards COVID-19 despite its significant damage. The past disaster was seen beneficial in the context of coping with the pandemic:

The pandemic was devasting. We were completely shut down for many months, with no income. However, what I’ve learnt from the past is that there’s always the sun after the dark. So, I watched the YouTube videos to self-educate myself, I attended the trainings organised by the local tourism board. The disasters we had in the past [the Aral Sea desiccation and the breakup of the Soviet Union] taught me to never give up (UZ16)

Discussion and conclusion

Theoretical implications

The study of women tourism entrepreneurs in a destination with the legacy of an anthropogenic environmental disaster enabled a better understanding of their motivations to start a business enterprise during unfavourable conditions. Thus, the study responded to the Correa et al. (Citation2021)’s call for more research on the motives of women entrepreneurs in emerging economies and under variable external conditions. The study indicated that female entrepreneurship in the Aral Sea region is largely driven by the necessity-based and extrinsic motivations. This finding aligns with Movono and Dahles (Citation2017) who highlight moneymaking as the main motive but contradicts Alonso-Almeida (Citation2012) and Ngoasong and Kimbu (Citation2019) who establish intrinsic motivation as key for women entrepreneurs in developing countries.

This mixed evidence suggests a strong effect of the local context as highlighted by Ribeiro et al. (Citation2021). This calls for more empirical research on the motives of women tourism entrepreneurs in various types of emerging economies (for example, developing and transitional) and different regions (for instance, Africa and Central Asia), preferably using larger samples or samples which are not purposively selected. The research should aim at providing a more in-depth evaluation of the exact motives behind female tourism entrepreneurship by reducing potential effect of social desirability bias. The research should also strive to assess how intrinsic motivation can be facilitated and promoted depending on the local study context alongside its political, socio-economic, cultural, and environmental conditions.

From the theoretical perspective, this study confirmed the value of Bourdieu’s Practice Theory (Bourdieu, Citation2005) and Social Practice Theory (Reckwitz, Citation2002) for analysis of the determinants of success for women-run MSMEs in a resource-scarce destination. More specifically, the study demonstrated the relevance of the notions of capital, field, agents, and habitus when explaining how women tourism entrepreneurs sought to obtain access to the limited resources of the case studied region for sustained business performance.

The study showcased the critical role of immediate family of women entrepreneurs in business success. This confirms the literature which has established significant help which spouses provide to women-run enterprises, especially in the initial phases of business development (Huarng et al., Citation2012). This current study, however, also demonstrated that another actor within immediate family i.e., children, could be instrumental in business success, especially in remote and resource-scarce destinations, such as the Aral Sea region. This reinforces the call to better understand the role of children in female tourism entrepreneurship set by Canosa and Schänzel (Citation2021). The systematic review undertaken by Canosa and Schänzel (Citation2021) identified only 10 studies mentioning, directly or indirectly, children as the agents of entrepreneurship. More research is warranted on this topic, especially in the contexts with limited socio-economic opportunities or in the destinations prone to prolonged disasters and crises.

The study reconfirmed the important role of social networks of women entrepreneurs in their business success. Although this was repeatedly highlighted in the literature (Badzaban et al., Citation2021), the novel contribution of this current study is in linking social connections to the cultural traits of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. The concept of useful connections (“svyazi”) was previously discussed in the “dark” context of business corruption in post-Soviet states i.e., as a means of obtaining extra benefits by overpassing rules (Karhunen et al., Citation2018). This current study shows that “svyazi” can also play a positive role, especially in a resource-scarce destination due to the legacy of a life event crisis. Future research is warranted specifically into the mechanisms of developing and maintaining “svyazi” by women tourism entrepreneurs in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, but also other post-Soviet countries. Policymakers can facilitate “svyazi” by organising workshops for women tourism entrepreneurs and inviting the agents that are difficult to engage, such as contractors/suppliers or prospective employees, to participate.

Policy and management implications

The study established the controversial role of policymakers as agents of business success in the Aral Sea region. Positive perception of policymakers in Uzbekistan indicates that policy interventions to support female entrepreneurship, as suggested earlier in the text, are likely to be effective in this tourism context. This is because positive image of policymakers in Uzbekistan will contribute to the industry uptake of the applied measures. In contrast, the negative perception of policymakers in Kazakhstan is concerning as it pinpoints a potentially limited scope for effective policy interventions due to public distrust. The government of Kazakhstan should learn from Uzbekistan how to build trust among women entrepreneurs. Workshops aiming to exchange best practices in promoting female tourism entrepreneurship can be organised between the two countries. These workshops should engage local NGOs whose help with training and upskilling of women entrepreneurs, especially in Uzbekistan, was recognised as significant.

Given that the Aral Sea region suffers from sustained environmental and socio-economic problems, dedicated policies are required to facilitate intrinsic motivation among local women entrepreneurs. These policies should encourage women to think about the wider societal implications of their business, such as poverty alleviation. To facilitate intrinsic entrepreneurship, policymakers can design dedicated programmes supporting business enterprises that have set to create social impact. For example, interest-free loans can be offered to women entrepreneurs who aim to employ, (re-)train or upskill residents. Alternatively, subsidies should be offered to business enterprises saving the environment. For instance, as Matyakubov et al. (Citation2021) argue, small-sized, family-run hotels installing solar panels for energy generation or water desalination in the Aral Sea region can be supported financially. Policies can also take the form of government-sponsored upskilling training programmes provided to prospective and existing employees of women-run tourism MSMEs to increase their productivity and qualifications.

Dedicated policies are also necessitated to encourage small family business in the Aral Sea region and enable inter-generational learning. Study and maintenance grants can be offered by national governments to children of women entrepreneurs who have chosen to pursue a tourism career in the destinations with limited economic alternatives.

From the perspective of social policy design, this study outlined the need for dedicated interventions aiming to enhance human needs for work, health, education, security, and wellbeing in the Aral Sea region of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. By encouraging and supporting women entrepreneurs, policymakers in both countries will showcase life-long opportunities to local people, thus preventing migration to more prosperous regions. Policymakers should consider women entrepreneurs in the Aral Sea region as key agents of change (Rosca et al., Citation2020) as women-run tourism MSMEs can aid in combating gender and societal inequality, fighting unemployment and promoting the destination and its sustainable tourism offer to visitors. Ultimately, this current study indicated that women tourism entrepreneurs in the Aral Sea region might provide potentially the only type of social capital which policymakers in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan could meaningfully utilize with the purpose of regional regeneration. Policymakers should therefore consult or even engage women tourism entrepreneurs in the design of social policies to be implemented in the region in question, but also in other regions of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

Contribution to knowledge and future research needs

The study produced some novel findings, thus extending the current body of knowledge on the determinants of female entrepreneurship in tourism. First, the study highlighted the importance of such agent as relatives, neighbours, and friends which was in addition to the (more traditional agent of) immediate family. “Svyazi” with this agent were found instrumental to facilitate business activity, especially in a time of a life event crisis. The important role of relatives, neighbours, and friends for women entrepreneurs in the Aral Sea region is partially attributed to the cultural influence, especially in Kazakhstan, with its strong nomadic traditions and customs of communal help, “Asar.” “Asar” was previously identified in the literature as a driver of social cohesion in local communities (Darmenova & Koo, Citation2021). This current study suggests that it is also a key success factor for women-run tourism MSMEs, especially in remote and resource-scarce destinations. Future research is necessitated into how the cultural traits of reciprocity, such as Asar in Kazakhstan or Gotong royong in South-East Asia (Lukiyanto & Wijayaningtyas, Citation2020), can be mobilized to support female entrepreneurship in destinations with limited resources or disaster legacy.

Second, the study showcased employees as a critical agent in business success of women-run tourism MSMEs. Although HRM is recognised as a major issue in tourism operations, research on female entrepreneurship does not pay sufficient attention to the problem of recruiting and retaining employees (CitationTabassum et al., 2019). This may be partially attributed to the size of women-run enterprises which require only a small number of recruits. However, many local contexts are characterised by labour outflows from remote/rural to urban areas. This raises questions about HRM challenges for local women entrepreneurs and how these challenges can be overcome. A dedicated research avenue is warranted to examine this management issue.

Third, the study highlighted the positive effect of the region’s remoteness, its resource scarcity, and a life event crisis on building relationships of women entrepreneurs with such agent of entrepreneurial practice as competitors. In Uzbekistan, these relationships are underpinned by the idea of competition; however, in Kazakhstan, women entrepreneurs are more likely to collaborate for mutual benefit. Although this benefit is largely financial, this draws upon the idea of coopetition. This finding provides an interesting reflection upon Theory of the tragedy of the commons (Hardin, Citation1968). This theory suggests that, in a time of resource scarcity, people tend to maximise the use of resources to gain maximum benefits. This translates well into the context of Uzbekistan; however, this idea does not apply to women entrepreneurs in Kazakhstan. This finding may be partially attributed to the cultural trait of reciprocal communal help which is more widespread in Kazakhstan than Uzbekistan. However, the exact mechanisms of coopetition in a destination with the disaster legacy need to be established which highlights a promising avenue for future research.

Fourth, this study tested empirically the conceptual framework proposed by Nakamura and Horimoto (Citation2020) which attempted to provisionally explain how life event crises could drive female entrepreneurship. This current study refined this framework by showcasing that a life event crisis triggered largely the necessity-based, extrinsically driven motivation which could evolve into the opportunity-based and intrinsic motivation with time. Further, Nakamura and Horimoto (Citation2020) highlighted social networks and societal traditions, such as negative attitudes towards women leaders, as potential barriers towards female entrepreneurship in Japan. In contrast, this current study demonstrated that these factors could become the determinants of success depending on the local context. The Soviet-inherited concept of “svyazi” and the nomadic tradition of reciprocity, Asar, facilitated female tourism entrepreneurship in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan in a time of a life event crisis. This calls for more nuanced research into the cultural and societal drivers and barriers of female entrepreneurship in tourism, especially in disadvantaged communities and destinations.

Lastly, this current study established positive associations between the experience of women tourism entrepreneurs of past life event crises and their perception and behaviour towards more recent critical events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Research has previously demonstrated limited organisational learning of tourism enterprises with a subsequent negative effect on business resilience, even in the destinations prone to consecutive disasters (Bhaskara & Filimonau, Citation2021). This current study indicated how the experience of past crises contributed to resilience of women tourism entrepreneurs. This was evidenced by specific attitudes towards COVID-19 whereby most study participants, albeit acknowledging its significant detrimental effect, developed effective copying mechanisms. Although this coping was predominantly attributed to building mental resilience, it enabled women entrepreneurs to grow a more positive outlook on a post-pandemic future. Using the idea of “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” (UZ1) women tourism entrepreneurs in the Aral Sea region considered COVID-19 as an opportunity to learn and rethink business directions, thus making themselves better prepared for future disastrous events. This finding calls for longitudinal, inter-disciplinary, research on organisational and individual learning in women-run tourism MSMEs in a time of a life event crisis. This research should engage scholars from disaster management, (tourism and hospitality) business management and psychology to generate a more comprehensive understanding of coping mechanisms and how these could be facilitated.

Limitations

As with any research, this study had limitations. The main limitation was attributed to the exploratory, qualitative nature of this project which implied restricted generalisability of the study’s findings. Purposive sampling was another limitation, and the application of random sampling could have offered further novel insights into this study’s findings. Lastly, the case studied region of the Aral Sea was unique in its history of anthropogenic environmental degradation. Replication of the study’s findings in other destinations impacted by a life event crisis should be done with caution due to potential influence of the local context as established earlier in the text.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Viachaslau Filimonau

Viachaslau Filimonau is a Faculty Member in the School of Hospitality and Tourism Management at the University of Surrey, UK, and a Visiting Research Fellow at the Hotelschool the Hague, the Netherlands. His research interests include sustainable mobilities, water and carbon footprint management in tourism and hospitality operations, and environmental management in tourism and hospitality enterprises.

Umidjon Matyakubov

Umidjon Matyakubov is Senior Lecturer in Sustainable Tourism at the Urgench State University, Uzbekistan. His research interests include sustainable tourism, ecological tourism, agritourism and sustainable hotel management.

Murodjon Matniyozov

Murodjon Matniyozov is Lecturer in Regional Tourism at the Urgench State University, Uzbekistan. His research interests include tourism economics and ecological tourism.

Aiman Shaken

Aiman Shaken is Senior Lecturer at the Department of Recreational Geography and Tourism, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Kazakhstan. Her research interests include assessment of the recreational potential of destinations, big data-based destination management, and agritourism.

Mirosław Mika

Mirosław Mika is Professor in Tourism Geography at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland. His research interests include local/regional tourism development, management of tourist destinations and tourism planning.

References

- Afshan, G., Shahid, S., & Tunio, M. N. (2021). Learning experiences of women entrepreneurs amidst COVID-19. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 13(2), 162–186. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-09-2020-0153

- Aldás-Manzano, J., Martínez-Fuentes, C., & Pardo-del-Val, M. (2012). Women entrepreneurship and performance. In M. A. Galindo & D. Ribeiro (Eds.), Women’s entrepreneurship and economics (pp. 89–108). Springer.

- Alonso-Almeida, M. M. (2012). Water and waste management in the Moroccan tourism industry: The case of three women entrepreneurs. Women's Studies International Forum, 35(5), 343–353.

- Asgary, A., Anjum, M. I., & Azimi, N. (2012). Disaster recovery and business continuity after the 2010 flood in Pakistan: Case of small businesses. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 2, 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2012.08.001

- Ataniyazova, A. O. (2013). Health and ecological consequences of the Aral Sea crisis. In The 3rd World Water Forum Regional Cooperation in Shared Water Resources in Central Asia, Kyoto.

- Azungah, T. (2018). Qualitative research: Deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qualitative Research Journal, 18(4), 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-D-18-00035

- Badoc-Gonzales, B. P., Mandigma, M. B. S., & Tan, J. J. (2022). SME resilience as a catalyst for tourism destinations: A literature review. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40497-022-00309-1

- Badzaban, F., Rezaei-Moghaddam, K., & Fatemi, M. (2021). Analysing the individual entrepreneurial resilience of rural women. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40497-021-00290-1

- Basco, R. (2015). Family business and regional development—A theoretical model of regional familiness. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 6(4), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2015.04.004

- Bastian, B. L., Sidani, Y. M., & El Amine, Y. (2018). Women entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: A review of knowledge areas and research gaps. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 33(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-07-2016-0141

- Berg, B. L. (2009). Qualitative research methods for the social science. Pearson Education.

- Bhaskara, G. I., & Filimonau, V. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and organisational learning for disaster planning and management. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 46, 364–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.01.011

- Bourdieu, P. (2005). Habitus. In J. Hillier & E. Rooksby (Eds.). Habitus: A sense of place (pp. 43–52). Ashgate.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

- Brindley, C. (2005). Barriers to women achieving their entrepreneurial potential: Women and risk. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 11(2), 144–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550510590554

- Bull, I., & Willard, G. E. (1993). Towards a theory of entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(3), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(93)90026-2

- Burnard, P. (1991). A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Education Today, 11(6), 461–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/0260-6917(91)90009-Y

- Cai, R., Leung, X. Y., & Chi, C. G.-Q. (2022). Ghost kitchens on the rise: Effects of knowledge and perceived benefit-risk on customers’ behavioral intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 101, 103110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103110

- Cakmak, E., Lie, R., & McCabe, S. (2018). Reframing informal tourism entrepreneurial practices: Capital and field relations structuring the informal tourism economy of Chiang Mai. Annals of Tourism Research, 72, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.06.003

- Cakmak, E., Lie, R., Selwyn, T., & Leeuwis, C. (2021). Like a fish in water: Habitus adaptation mechanisms of informal tourism entrepreneurs in Thailand. Annals of Tourism Research, 90, 103262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103262

- Canosa, A., & Schänzel, H. (2021). The role of children in tourism and hospitality family entrepreneurship. Sustainability, 13(22), 12801. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212801

- Cardella, G. M., Hernández-Sánchez, B. R., & Sánchez-García, J. C. (2020). Women entrepreneurship: A systematic review to outline the boundaries of scientific literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1557–1518. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01557

- Cavada, M. C., Bobek, V., & Macek, A. (2017). Motivation factors for female entrepreneurship in Mexico. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 5(3), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2017.050307

- Chung, J., & Monroe, G. S. (2003). Exploring social desirability bias. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(4), 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023648703356

- Climate and Clean Air Coalition. (2018). Women entrepreneurs turning waste into useful products. https://www.ccacoalition.org/ru/node/2479

- Cole, S. (2018). Gender equality and tourism: Beyond empowerment. CABI.

- Correa, V. S., Brito, F., de Lima, R. M., & Queiroz, M. M. (2021). Female entrepreneurship in emerging and developing countries: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-08-2021-0142

- Dahles, H., & Susilowati, T. P. (2015). Business resilience in times of growth and crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 51, 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.01.002

- Darmenova, Y., & Koo, E. (2021). Towards local sustainability: Social capital as a community insurance in Kazakhstan. Journal of Eurasian Studies, 12(2), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/18793665211038143

- De Clercq, D., & Voronov, M. (2009). The role of cultural and symbolic capital in entrepreneurs‘ability to meet expectations about conformity and innovation. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(3), 398–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2009.00276.x

- Dibra, M. (2015). Rogers theory on diffusion of innovation-the most appropriate theoretical model in the study of factors influencing the integration of sustainability in tourism businesses. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195(3), 1453–1462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.443

- Diekmann, A., & McCabe, S. (2011). Systems of social tourism in the European Union: A critical review. Current Issues in Tourism, 14(5), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2011.568052

- European Commission. (2022). Women's situation in the labour market. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/gender-equality/women-labour-market-work-life-balance_en

- Farr‐Wharton, R., & Brunetto, Y. (2007). Women entrepreneurs, opportunity recognition and government‐sponsored business networks. Women in Management Review, 22(3), 187–‐207. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420710743653

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., Kimbu, A., de Jong, A., & Williams, A. M. (2022). Sustainability through the tourism entrepreneurship journey: A gender perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1562–1585. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1831001

- Filimonau, V., & De Coteau, D. (2020). Tourism resilience in the context of integrated destination and disaster management (DM2). International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(2), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2329

- Forson, C., Ozbilgin, M., Ozturk, M. B., & Tatli, A. (2014). Mutli level approaches to entrepreneurship and small business research – transcending dichotomies with Bourdieu. In E. Chell & M. Karatas-Ozkan (Eds.), Handbook of research on small business and entrepreneurship (pp. 54–69). Edward Elgar publications.

- Foss, L., Henry, C., Ahl, H., & Mikalsen, G. H. (2019). Women’s entrepreneurship policy research: A 30-year review of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 409–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9993-8

- Frederick, D., & Adam, I. (2022). Entrepreneurial motivations among COVID-19 induced redundant employees in the hospitality and tourism industry. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 21(1), 130–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2022.2015239

- Ganesan, R., Kaur, D., & Maheshwari, R. C. (2002). Women entrepreneurs: Problems and prospect. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/097135570201100105

- Ghauri, P., & Gronhaug, K. (2005). Research methods in business studies: A practical guide (3rd ed.). Financial Times Prentice Hall.

- Gherardi, S. (2015). Authoring the female entrepreneur while talking the discourse of work-family life balance. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 33(6), 649–666. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242614549780

- Gibbs, A. (2012). Focus groups and group interviews. In: J. Arthur, M. Waring, R. Coe, L.V. Hedges (Eds.), Research methods and methodologies in education, SAGE Publications Ltd, London (2012), pp. 186–192.

- Grandy, G., Cukier, W., & Gagnon, S. (2020). (In)visibility in the margins: COVID-19, women entrepreneurs and the need for inclusive recovery. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 35(7/8), 667–675. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-07-2020-0207

- Grube, L. E., & Storr, V. H. (2018). Embedded entrepreneurs and post-disaster community recovery. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 30(7–8), 800–821. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2018.1457084

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162(3859), 1243–1248. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

- Hennekam, S., & Shymko, Y. (2020). Coping with the COVID-19 crisis: Force majeure and gender performativity. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(5), 788–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12479

- Hofstede, G. (1984). The cultural relativity of the quality of life concept. Academy of Management Review, 9(3), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.2307/258280

- Huarng, K. H., Mas-Tur, A., & Yu, T. H. K. (2012). Factors affecting the success of women entrepreneurs. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 8(4), 487–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-012-0233-4

- Jang, K., Sakamoto, K., & Funck, C. (2021). Dark tourism as educational tourism: The case of ‘hope tourism’ in Fukushima, Japan. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 16(4), 481–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2020.1858088

- Jones, I., Holloway, I., & Brown, L. (2013). Qualitative research in sport and physical activity. Sage.

- Kakabadse, N., Tatli, A., Nicolopoulou, K., Tankibayeva, A., & Mouraviev, N. (2018). A gender perspective on entrepreneurial leadership: Female leaders in Kazakhstan. European Management Review, 15(2), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12125

- Karhunen, P., Kosonen, R., McCarthy, D., & Puffer, S. M. (2018). The darker side of social networks in transforming economies: Corrupt exchange in Chinese Guanxi and Russian Blat/Svyazi. Management and Organization Review, 14(2), 395–419. https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2018.13

- Katongole, C., Ahebwa, W. M., & Kawere, R. (2013). Enterprise success and entrepreneur’s personality traits: An analysis of micro- and small-scale women-owned enterprises in Uganda’s tourism industry. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 13(3), 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358414524979

- Khalil, M. B., Jacobs, B. C., McKenna, K., & Kuruppu, N. (2020). Female contribution to grassroots innovation for climate change adaptation in Bangladesh. Climate and Development, 12(7), 664–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1676188

- Khitarishvilli, T. (2016, June 23–24). Gender inequalities in labour markets in Central Asia. Paper prepared for the joint UNDP/ILO Conference on Employment, Trade and Human Development in Central Asia, Almaty, Kazakhstan.

- Kimbu, A. N., de Jong, A., Adam, I., Ribeiro, A. M., Adeola, O., Afenyo-Agbe, E., & Figueroa-Domecq, C. (2021). Recontextualising gender in entrepreneurial leadership. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103176

- Kimbu, A. N., & Ngoasong, M. Z. (2016). Women as vectors of social entrepreneurship. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.06.002

- Kourtesopoulou, A., & Chatzigianni, E. E. (2021). Gender equality and women’s entrepreneurial leadership in tourism: A systematic review. In M. Valeri & V. Katsoni (Eds.), Gender and tourism (pp. 11–36). Emerald Publishing Limited.