Abstract

Drawing on the literature that examines business models, feminist ethics of care and social policy, this article develops a theoretical framework for uncovering gender influences on sustainable business models by women entrepreneurs in a highly patriarchal and established tourism destination. Gender influences are socially embedded drivers that inform how women entrepreneurs create and operate sustainable business model archetypes and manifest as doing gender (accepting and complying with gendered perceptions) and redoing gender (resisting gendered perceptions by displaying masculine traits or taking advantage of their femineity) in the business realm. Empirically, the article provides a qualitative analysis of in-depth interviews with women owner-managers of fourteen small tourism firms in Turkey. The study provides evidence of gender influences that materialise as gendered perceptions of identity, role expectations and legislative practices (regulative). The managerial and social policy implications that encourage and support women entrepreneurs in pursuing sustainable business models are critically examined.

Introduction

This study shows that women entrepreneurs who create sustainable business models and require gender-aware policy and practical support to enable them to overcome gendered biases in sustainable tourism development. A business model describes how a firm creates, operates and captures value for its key stakeholders (customers, resource providers, employees) and can be is a source of innovation and competitive advantage for entrepreneur owner-managers (Manolova et al., Citation2020). We specifically focus on how gender influences the characteristics of the sustainable business models of women-owned tourism businesses. Due to patriarchal values and the role of women in the family, women face challenges such as access to finance and networking opportunities; entrepreneurship is perceived as a masculine role (Eraydın & Türkün-Erendil, Citation2002; Swail & Marlow, Citation2018). In a recent commentary, Manolova et al. (Citation2020) argue that the development of business models can only be fully understood by taking into consideration both the economic and social structures in which women-owned businesses operate and the gender issues they encounter in pursuing business opportunities.

We see a research gap regarding the incorporation of gender in the study of sustainable business models. Specifically, we seek to contribute to the sustainable tourism literature regarding how women entrepreneurs develop sustainable business models by responding to context-specific gender factors in the tourism industry. Studies linking entrepreneurship and sustainability have used green entrepreneurship, environmental entrepreneurship and sustainable entrepreneurship, sometimes interchangeably, reflecting various forms of sustainability (Gast et al., Citation2017). An example is tourism businesses that target green certifications from regulators as evidence of their sustainability practices (Dunk et al., Citation2016). In terms of gender, women entrepreneurs are seen as typically undertaking business activities associated with the tourism sector (e.g. offering cleaning, catering and childcare services; making and selling products such as bread or cheese), while men are often associated with performing manufacturing activities (Pettersson & Heldt Cassel, Citation2014; Cicek et al., 2017). Vatansever and Arun (Citation2016) speculate that female entrepreneurs and male entrepreneurs differ in how they practice green entrepreneurship. Review studies have found that feminine entrepreneurial characteristics, such as ethics of care and ethically oriented decisions, are more frequently attributed to women than to men (Hechavarria, 2016; Outsios & Farooqi, Citation2017). Women entrepreneurs are known to define strategies that ensure their business activities will create positive benefits for society, achieve commercial goals and serve defined community needs around tourism (Kimbu & Ngoasong, Citation2016).

Understanding the gendered influences on sustainable business models also matters for the attainment of gender equality in patriarchal or male-dominated tourism destinations. We use the word patriarchal to refer to destinations that have social structures and practices in which men govern and are perceived as oppressing and exploiting women (Beechey, 1979; Walby, Citation1989). For instance, evidence on Turkey (Sarigil & Sarigil, Citation2021) reveals societal perceptions where women should not be outside of the home; they are expected to stay at home to take care of housework (Maden, Citation2015). Studies on other developing countries, such as Cameroon (Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019) and Lebanon (Tlaiss & Kauser, Citation2019) also reveal how societal perceptions and attitudes towards entrepreneurs are biased in favour of men, creating a struggle for women-owned businesses to gain legitimacy. Knowledge of gendered influences can inform policy practices towards achieving both long-term, social and environmental sustainability (Bocken et al., Citation2014) and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal 5, which aims to achieve gender equality by empowering all women and girls. This article, therefore, addresses the following research question: What are the characteristics of sustainable business models for small tourism businesses? How does gender influence the development of sustainable business models by women entrepreneurs?

In addressing the above questions, this study contributes to the tourism literature on how women entrepreneurs do gender (Pettersson & Heldt Cassel, Citation2014) by reconceptualising gender influences at the intersection of sustainable business model archetypes (Bocken et al., Citation2014; Uslu et al., Citation2015) and ethics of care and gender role socialisation theory (Chodorow, Citation1971; Gillian, 1982). We derive a theoretical framework for understanding gender influences on the development of sustainable business models by women entrepreneurs in a highly patriarchal and established tourism destination. We argue that gender influences are gendered perceptions of identity, role expectations and legislative practices (regulative) that are socially embedded drivers informing the entry choices and post-entry strategic decisions of women entrepreneurs about the types of sustainable business models to pursue. We develop this theoretical argument by investigating the circumstances under which gender influences result in either acceptance (compliance), ignore/challenge (defiance) of identity, expectation and regulation in women entrepreneurs’ decision-making about their choice of sustainable business model archetypes.

This study also contributes to the tourism literature by uncovering how doing and redoing gender (Maden, Citation2015; Pettersson & Heldt Cassel, Citation2014) constitute gender-aware entrepreneurial responses used by women entrepreneurs to respond to perceived gendered challenges in the pursuance of sustainable business models. Vatansever and Arun (Citation2016) recommend that strengthening the role of women in sustainable development requires further study. We complement the limited existing studies that link entrepreneurship to the environment in Turkey (Uslu et al., Citation2015) by providing a qualitative analysis of in-depth interviews with women owner-managers of small tourism businesses in Turkey. Turkey is a suitable research context because of the large proportion of women entrepreneurs that operate in tourism (Maden, Citation2015) and because unsubstantiated claims allude to women entrepreneurs being more sustainability-oriented rather than economically-oriented.

Tourism is one of Turkey’s most dynamic and fastest-growing economic sectors (OECD, Citation2020) with 45.8 million international tourists and 126.4 million domestic trips in 2018. In that year, tourism accounted for 7.7% of total employment (2.2 million people) and 3.8% of GDP. The gender gap in TEA (Total Entrepreneurial Activity) is reported as much as 60% in Turkey (GEM, 2021). Furthermore, according to Women’s Financial Inclusion Data (WFID, Citation2022), only 9% of Turkish SMEs are women owned/-led. According to the Tourism Strategy of Turkey 2023, achieving sustainability in the tourism sector requires providing entrepreneurship support to women (Ministry of Culture & Tourism, Citation2020). Moreover, almost all sustainable tourism projects in Turkey claim to integrate the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 5 (gender equality) (Guzeloglu & Gulc, Citation2021).

Recent studies indicate that women-led businesses may have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, with the result that some of the progress previously made towards encouraging women’s entrepreneurship may have been jeopardized (GEM 2021; Manolova et al., Citation2020). Women entrepreneurs are seen as more excluded from entrepreneurship, compared to men (OECD, 2022). Understanding their lived experiences as individuals is a useful starting point when considering the structural interventions necessary to support them at the social policy level (Minnaert et al., Citation2009). The policy discourse of exclusion reveals a “gendered” argument that it is socially desirable for women as mothers or housewives to be less engaged in entrepreneurship. Critiques of this gendered argument see it as a cause rather than a result of exclusionary policies (Ahl & Nelson, Citation2015; Kimbu et al., Citation2019; Minnaert et al., Citation2009; OECD, Citation2021). Supportive social policies enhance the role of women entrepreneurs in sustainable development (Kim & Bramwell, Citation2019). In the next section, we provide a literature review and a description of the research method. This is followed by the study’s findings, and we offer a discussion and conclusions to finish.

Understanding gender influences on sustainable business models in tourism

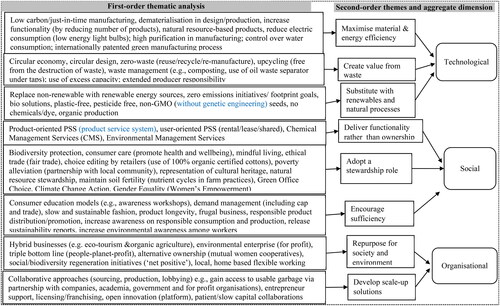

The research of Boons et al. (Citation2013) argues that sustainable development requires radical and systematic efforts. This means that sustainability issues should be incorporated into any new model at an early stage; sometimes, even before launching the new business. Bocken et al. (Citation2014), provide a framework that can be used to determine whether or not an existing enterprise has a sustainable business model and, if so, the characteristics of the sustainable business model. In their research, Bocken et al. (Citation2014, p.48), describe sustainable business model archetypes as “groupings of mechanisms and solutions that may contribute to building up the business model for sustainability.” The groupings they describe are: technological, social and organisational. In technological groupings, the focus is on three objectives: to maximise material and energy efficiency; to create value from “waste”; and to substitute waste-generating production with renewables and natural processes. In social groups, the focus is again on three key objectives: to deliver functionality rather than ownership (provide services that satisfy users’ needs without having to own the physical product); to adopt a stewardship role (proactively engage with all stakeholders to ensure their long-term health and well-being); and to encourage sufficiency. Finally, in organisational groups, a key focus is for entrepreneurs to re-purpose the business for societal/environment impact as well as develop scale-up solutions to maximise the impacts.

Our aim here is to complement these studies by integrating and linking the sustainable business model (Bocken et al., Citation2014) with a gender perspective (Leu, Eriksson & Müller, 2018) to uncover how women entrepreneurs actively mobilise resources from wherever possible to create and operate businesses that contribute to sustainable development (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020; Yachin & Ioannides, Citation2020). As owner-managers of small tourism firms, women entrepreneurs can use their businesses to facilitate sustainable development, for example through engaging with their spatial environment to design tourism products that display technological and social components of a business model. Being embedded within their local communities also provides opportunities to be part of community-based collective mobilisation (Jørgensen et al., Citation2021) that enhance their capacity to create private for-profit models (Zhang & Zhang, Citation2018) through which their small tourism firms can contribute to sustainable development.

The gender perspective (Leu, Eriksson & Müller, 2018) that we adopt integrates the theoretical constructs of (i) ethics of care (Gillian, 1982; Held, Citation2014), and (ii) gender role socialisation (Chodorow, Citation1971), both of which emphasise the importance of identity and roles as underpinning the traditional female and male stereotypes viewed in the decision processes of entrepreneurs (Gillian, 1982). An integrative theoretical construct reflects social constructionist feminism in which the term gender is socially constructed for exploring the experiences of women entrepreneurs. Gender perceptions of identity and roles are useful for uncovering gender influences on sustainable business models while highlighting the social construction of gender through a series of individual acts and daily interactions with others (Diaz-Garcia & Welter, Citation2013).

Since gender is constructed through daily interactions, researchers can also elaborate on gender-neutral contexts we suggest that ethics of care theory provides a framework for uncovering women’s acts, as individuals, and their daily interactions with others when explore and implement a sustainable business model. Care is defined here as a relational process whereby someone does the caring and there is someone, or something, being cared for (Noddings, Citation1984). Female and male entrepreneurs can practice ethics of care in their sustainability-related activities where owners/managers are seen as behaving relational when they demonstrate care for society and the environment (Hawk, Citation2011). Ethics of care is not only relational but also rational since it allows entrepreneurs to make logical decisions for the financial benefit of their businesses (Fors & Lennerfors, Citation2019). For example, creating value from waste by practising ethics of care can protect nature (relational) but also reduce cost savings (rational). An example like this, is evidence that humans are not only rational but also relational in their sustainability practices (Fors & Lennerfors, Citation2019).

In organisations, male/female gender, sexuality and bodies can be classified into two groups: men are more likely to follow organisational rules, arrangements and assumptions, while women are assumed to be unable to do so, due to family and reproductive obligations (Noddings, Citation1984). Such a gender analysis of sustainable business models, in relation to ethics of care, might reveal potential challenges, and/or opportunities, for improving gender equality while creating business opportunities (Pla-Julian & Guevara, 2019). The tourism social entrepreneurship literature reveals that although women entrepreneurs are driven by financial needs, their societal impact aspirations reflect their caring responsibilities and their motivation to serve defined community needs around tourism (Kimbu & Ngoasong, Citation2016).

As the above discussion reflects, there is a growing number of studies that acknowledge the intersection of gender factors, entrepreneurial responses and sustainability (Braun, Citation2010; Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020; Hechavarria 2016; Outsios & Farooqi, Citation2017; Vatansever & Arun, Citation2016). These studies reveal that gender influences can be uncovered by focusing on: (i) identity, as shaping women entrepreneurs’ choices and risk/results orientations; (ii) gender roles within a family (mum, dad, husband, wife, housewife, etc.), as shaping women’s entrepreneurial behaviours in terms of their choices of type of sustainable business model archetype to pursue; (iii) extended gender roles (societal), as evidenced in society’s perceptions about men versus women, which can affect women’s confidence and legitimacy in pursuing sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship; and (iv) gender characteristics, such as reproductive health challenges that pose risks for women versus men in balancing the pursuit of business and life choices around childcare. We see gender influences as crystallising around entrepreneurial choices (those made by entrepreneurs during business formulation and execution) and entrepreneurial behaviours, both of which are reflected in women’s entrepreneurial journeys through sustainable tourism (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020).

In summary, addressing the question of how gender influences the characteristics of sustainable business models developed by women entrepreneurs in an established tourism destination requires three interlinked investigations. First, we identify the sustainable business model archetypes in terms of technological, social and organisational from analysing women-owned businesses. Second, we examine how gender factors (identity, roles and characteristics) constitute opportunities, risks or challenges for women in pursuing their desired sustainable business model archetypes. Third, we unpack the gender influences that enable sustainable business models for women entrepreneurs and show how these provide opportunities for social policy interventions that address persistent biases facing women entrepreneurs to contribute to sustainable development.

Thams et al. (Citation2018) suggest that as progressive, national policies become institutionalised and accepted, there will be more opportunities for women to attain directorships. Social policy implications matter because, despite global recognition that women are in a disadvantaged position compared to men, governmental policies continue to position women entrepreneurs in a gender-neutral manner in both developed (Ahl & Nelson, Citation2015; Noddings, Citation1984) and developing countries (Kimbu et al., 2019). Samad and Alharthi (Citation2022) illustrate the importance of social policies on women’s entrepreneurship in sustainable tourism by focusing on how women’s work is perceived. They suggest that the tourism sector should assure that women receive support from the community and from their families by reducing conflicts that involve cultural norms, such as certain jobs in tourism being more appropriate for women.

Another perspective on sustainability suggests that rather than treating social policies in tourism (Minnaert et al., Citation2009) as being separate from environmental policies, there should be important linkages made with other sectors to ensure complementary benefits for sustainable tourism development (Kim & Bramwell, Citation2019; Kimbu et al., 2019). Alarcón and Cole (Citation2019), Eger et al. (Citation2022) and Ferguson & Alarcón (Citation2015) all claim that sustainable tourism, SDG 5 gender equality and other sustainable development goals are interconnected. They argue that there is no sustainability in tourism without gender equality. For instance, UN Women (Citation2018a, Citation2018b) reports that women are 14 times more likely to die in a disaster than men, therefore, in planning, policymaking and implementing tourism, especially in relation to climate change resilience, women’s voices are essential. This example clearly demonstrates the relation between SDG 13 (“Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts”), SDG 5 (“Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”) and sustainable tourism. Some of the important complementarities are highlighted as part of our empirical analysis, alongside the primary focus on gender influences on sustainable business model archetypes.

Methods

Research setting and design

This study seeks theory development from in-depth and context‐relevant case studies (Miles et al., Citation2014) of women-owned, sustainable business models in an established tourism destination. Our chosen established destination is Turkey, where tourism is one of the fastest-growing economic sectors. Alongside Mexico, Italy and Greece, Turkey is an established destination where less than 50% of women are in work and where policy interventions can significantly address this disadvantage by increasing women’s participation in sustainable development through business creation (OECD, Citation2008, p. 11). Policy documents signal the potential for linking entrepreneurship, environment/sustainability and gender through green entrepreneurship by women (CP/RAC., Citation2012). According to the Tourism Strategy of Turkey 2023, achieving sustainability in the tourism sector includes providing entrepreneurship support to women (Ministry of Culture & Tourism, Citation2020). Additionally, almost all sustainable tourism projects in Turkey claim to integrate the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 5 (gender equality) (Guzeloglu & Gulc, Citation2021).

Turkey is also a suitable research setting due to persistent gender inequality in its entrepreneurship sector. According to Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, the levels of total early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA) by gender is 10.3% women and 21.1% men, i.e. there are still two or more men starting and running a new business for every woman doing the same (GEM, 2022). Women-led businesses have borne the brunt of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, implying that the progress made, pre-pandemic, towards greater gender equality in entrepreneurship may have been jeopardized (Manolova et al., Citation2020). Without understanding and addressing gender influences on sustainable business models by women entrepreneurs the a risk of worsening existing inequalities. Finally, we also selected Turkey because it offers us the opportunity to access a cross‐section of tourism businesses (Yachin & Ioannides, Citation2020) with sustainable business models that are women-owned. Examples of tourism businesses in Turkey include eco-tourism, medical tourism, textile and fashion businesses in tourist centres, agribusinesses that supply food to the hospitality sector, restaurant chains and hospitality services, renewable energy, transport and travel services (Uslu et al., Citation2015).

Our real-life context was the lived experiences of women entrepreneurs in Turkey. We used women-owned, sustainable business models as case studies (Yin, Citation2009) for illustrating the creation and operation of sustainable business model archetypes. Our study consisted of multiple cases of women-owned, sustainable business models, with the woman owner-managers representing study participants whose lived experiences constituted qualitative data that supports theory building (Miles et al., Citation2014; Yin, Citation2009).

In terms of the researcher’s positionality, the approach taken reflected an insider-outsider perspective, the first author being the insider (Turkish, female, academic researcher who shares a cultural background with the research participants) and the second author being the outsider (male, academic researcher). This perspective allowed for an interviewer-interviewee discussion to inform the study participants and for data collection. An insider has easy access to the culture being studied and is regarded as “one of them” (Sanghera & Thapar-Björkert Citation2008). An insider is able to ask more meaningful, and/or insightful questions, due to possession of a priori knowledge of the diverse local contexts, language (in this case, Turkish language, including colloquial language and non-verbal cues), which is advantageous for qualitative researchers (Holmes, Citation2020). The value of having the outsider perspective is to enhance the objective and critical analysis of the participants’ experiences, as an outside expert (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020).

Sampling and data collection

A combination of purposive sampling and maximum variation sampling techniques was used to ensure the selection of Turkish women managers in tourism firms who had ownership and decision-making responsibilities (Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019). The recruitment and primary data collection were undertaken by the Turkish, female co-author, who recruited the owner-managers from own networks and persons that we had identified from publicly available information from an online review of the country context of gender and sustainable tourism in Turkey. Maximum variation sampling techniques ensured that the sample was diverse in terms of the types, size and scope of the tourism businesses, and with respect to the women’s family statuses (Yachin & Ioannides, Citation2020).

Using purposive sampling, we recruited 14 women-owned businesses, that we deemed to be suitable (Yin, Citation2009) for providing in-depth accounts of the lived experiences of women tourism entrepreneurs in Turkey. We interviewed the woman owner-manager of each business (). Data collection took place in two phases, first, in October 2019 as part of a pilot study and, second, from November 2020 to April 2021. The need to have such a big gap is also due to delays in participants’ availability due to the pandemic covid-19. Informed by the literature review, our interview questions included: the characteristics of the sustainable business model archetype (technology, social and organisational archetypes) (Bocken et al., Citation2014; Yachin & Ioannides, Citation2020), gender factors and associated influences on women’s entrepreneurship (e.g. Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020; Hechavarria, 2016).

Table 1. Women entrepreneurs studied.

The interviews were conducted through a combination of face‐to‐face interviews and over Skype (Yachin & Ioannides, Citation2020), the latter being unavoidable due to the travel restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Interviews were conducted in Turkish and each lasted one hour on average. Data collection was stopped when the materials were highly repetitive and had reached data saturation (Jennings, Citation2005). With the consent of the interviewees, the interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim in Turkish and English, cross-checked and triangulated by the co-authors prior to data analysis (Decrop, Citation1999; Yin, Citation2009). To validate the findings, we adopted the suggestion of Bruton et al. (2011). Specifically, we corroborated the findings through expert interviews with five key informants: a senior government official from the union of municipalities, an enterprise development manager at the Istanbul Chamber of Commerce, a member of the Business Council for Sustainable Development in Turkey (responsible for sustainability) and a representative of the Women’s Environment, Culture and Business Cooperative.

Data analysis

This study adopted a qualitative content analysis of the data (interview transcripts, documents and field notes) through within-case analysis, cross-case analysis and theory-building phases (Miles et al., Citation2014). The within-case analysis served to uncover codes related to gender influences on sustainable business models in tourism from the perspective of each women entrepreneur. The data were analysed using Nvivo to identify descriptive categories as first-order codes. In cross-case analysis, we compared the codes across the within-case analyses to deepen our understanding and improve the building of a reliable theory (Miles et al., Citation2014). The data analysis followed the Gioia method, which consists of categorising participants’ accounts as first-order, structuring these into second-order codes, and, subsequently, aggregating theoretical dimensions (Gioia et al., Citation2013; Ngoasong & Lamptey, 2021).

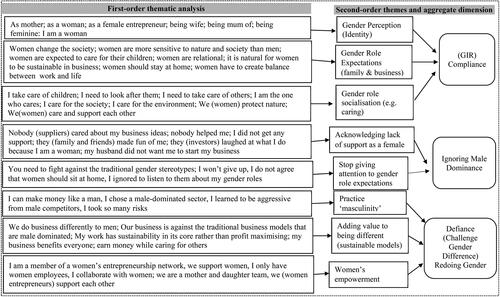

Participants’ accounts are keywords or phrases within entire responses captured in transcripts and fieldnotes (Gioia et al., Citation2013). The content was analysed to create a data analytic structure of the sustainable business model archetypes (technology, social and organisational), for the women-owned businesses () and to understand how gender factors influenced how women entrepreneurs made decisions about engaging in sustainable business model practices (). While doing this, we highlighted sections of the accounts provided by participants for use as direct quotations in support of the analysis (Kimbu & Ngoasong, Citation2016). Using cross-case analysis, to compare how the conceptual themes are reflected in each case, enabled us to discover aggregate themes for theorising the gender influences.

Findings

The characteristics of women-owned sustainable business model archetypes

The business practices of the women entrepreneurs revealed the characteristics of their sustainable business model archetypes (Bocken et al., Citation2014) in terms of technological, social and organisational archetypes (). However, while some women entrepreneurs gave accounts that fit one of the three archetypes, others spoke about entry decisions to establish a traditional business and, subsequently, made a shift to more technological archetypes. Some of the women had the intention when they started up the traditional business, while for others, the intention emerged and evolved organically. The accounts provided by half of the participants (F1, F2, F3, F5, F11, F13 and F14) reflected ethics of care for the environment alongside financial goals to create profit-making businesses, as exemplified in the following quotes:

I create solutions to social problems by combining both organic agriculture and eco-tourism […] we transformed the village into an eco-village that serves the economy, society and nature. [Interview, F2]

When I started, I had two important goals – decreasing poverty and increasing awareness of environmental protection. [Interview, F5]

F4, F8, F9 and F12 were examples of businesses that gradually shifted to more sustainable business models. While most of the tourism activities of women entrepreneurs involved home-based manufacturing and cooking, these four women entrepreneurs went beyond home-based tourism in ways that challenged patriarchy (Boonabaana, Citation2014). For instance, F8’s business sought to maximise material and energy efficiency by using renewables and natural processes in constructing ecotourism and agrotourism buildings.

Building a house with a straw bale and plastering method is low-cost and environmentally friendly. […] To construct a completely ecological building that has a very low carbon footprint, we convert the soil into a building soil that is resistant to fire, consumes less energy and provides moisture balance with many benefits for the environment. We do recycle and rainwater harvesting where we collect, store, treat and use rainwater in the toilet bowl with a water booster. [Interview, F8]

A collaborative approach was inherent in the business models of F5 and F6. For example, F5’s business, located in Ayvalik (a sea-side tourist town in the Balikesir province), was an example of a woman-owned business model that created commercial value from waste (Manolova et al., Citation2020) through a collaborative approach. Rather than simply selling handicrafts to visitors, the business ran workshops where visitors learned how to co-create handicrafts from waste. Here the women entrepreneur created awareness for how tourists can move away from simply buying a new product to learning how to create and/or reuse existing products, thereby promoting sustainability values in the tourism sector. Our data also revealed a collaborative approach in the cooperative model used to increase women’s visibility in tourism for gender equality (Sefer, Citation2020).

We also considered F10, who ran a restaurant chain through franchising, which is an organisational archetype of a sustainable business model. The chain operated eight organic food restaurants in Ankara (5), Hatay (3) and İstanbul (1), each offering what the owner called a “Green Menu”. The restaurants each had in-house food waste management systems that separated cooking oil from water in the kitchens. The waste oil was collected, stored and transported to the municipality for safe disposal. Green menu and waste management are core sustainability goals that enable small businesses to comply with environmental regulations (e.g. Dunk et al., Citation2016), yet they constitute a financial cost for small businesses such as F10. A franchising model facilitates the delivery of functionality and sufficiency by sharing risks and rewards with other franchisees, while ensuring strict adherence to a chain-wide, controlled waste management regime. F10 told us:

One of our franchise conditions is: If someone [child, homeless, refugee] comes to your door and says that “I’m hungry” you must feed him/her. This is the culture of the Turks. But unfortunately, it has been forgotten in many places. [Interview, F10]

Gender influences as drivers of sustainable business models

provides accounts of gender influences in the women entrepreneurs’ narratives, aggregated into three themes: compliance with gender identity and role (GIR), ignoring male dominance and defiance of (challenging) gender difference. The first two aggregate themes relate to doing gender, while the third relates to redoing gender. Let us consider women entrepreneurs F9 and F12, both of whom had men as co-founders of their businesses. Both women shared experiences that reflected the dynamics of doing gender in an entrepreneurship context (Swail & Marlow, Citation2018). They gave accounts of the circumstances under which having men as co-founders were either helpful or challenging for creating and operating their sustainable business models. However, when faced with challenges, the women entrepreneurs’ responses can be described as redoing gender.

Grant support was being given to those who wanted to commercialise their project. I applied with my thesis supervisor and now he is the co-founder of the firm. I did not face any difficulties in terms of getting support with my partner. [Interview, F9]

People [stakeholders, investors, suppliers] have the perception that as a woman, I cannot deal with problems by being so friendly, emotional and sensitive. When I share my thoughts in meetings, I get reactions like you might be looking emotional because you are a woman. But, when my male partners share their thoughts, nobody tries to analyse their thoughts or behaviours. Therefore, I started to lose my softness. You involuntarily begin acting like men. Compassion and sentimentality should not be just the feelings associated with me since I am a woman; men can have these feelings too. [Interview, F12]

The above quotation is related to defiance through challenging gender differences, biases and stereotypes in than, rather than simply displaying feminine traits through caring (Fors & Lennerfors, Citation2019), the entrepreneurs we studied simultaneously displayed traits traditionally considered to be feminine and masculine, while adding value to the caring characteristics (e.g. through building relationships with others).

We interviewed women entrepreneurs who were unable to secure financial support despite the fact that they clearly articulated to potential finance providers how they were managing their care responsibilities, such as by organising childcare, to effectively demonstrate their commitment to running a start-up business. Even F5, who was single and did not have a child, identified the societal perception that childcare responsibilities would restrict a woman’s ability to run a business. However, she spoke about how being a woman presented a further challenge. The account she provided in the quotation below, is related to redoing gender in the sense that she defies societal expectations by actively demonstrating that feminine and masculine interpretations can produce similar outcomes.

For men, nobody is surprised if they become an entrepreneur. For women, it is more surprising. Sometimes, nobody takes you seriously because you are a woman. I can’t remember how many times I describe a way of doing things to a male counterpart and he said no, let me tell you how to do it and then he told me the same thing I had already said. […] I started in 2007 and much has changed since that time. But class-structured society and classic business models for money have never changed in Turkey. The expectation from female entrepreneurs is to make money the same way men do. Environmental entrepreneurship is even more challenging. [Society tends to] expect us [female entrepreneurs] to pursue solely financial outcomes. [Interview, F5]

The above societal expectation that women entrepreneurs should focus solely on generating financial outcomes reflects experiences in contexts where women feel they should ignore male dominance (Diaz-Garcia & Welter, Citation2013; Tlaiss & Kauser, Citation2019). Our data shows how women entrepreneurs can overcome this expectation. Studies in Turkey have focused on how women do gender (Maden, Citation2015). Our data reveals how women re-do gender by challenging existing biases. To uncover evidence of re-doing gender, we examined how women entrepreneurs draw on organisational archetypes of sustainable business models involving collaborations that empower women. Collaborations, such as through cooperatives, raise awareness of, and access to, resources for those women who have the agency to act on the resources (Kimbu et al., 2019). The following are illustrative quotes from F6 (women farmers’ cooperative), F10 (collaborating with the municipality on waste management) and F5 (collaborating with multinational corporations):

We work with female farmers. I am the founder, farmer, and marketer of a women’s cooperative […] We generate income for our members (women farmers) by offering them a common market in the local bazaar for the private sale of their produce. [Interview, F6]

We have access to our usable garbage thanks to collaboration with corporations like Unilever, M&S, Vodafone. I took part in the Civil Involvement Project at the Sabanci University to increase awareness and responsibility for the environment and social problems like women’s empowerment. That is where I knew the companies interested in a positive public image for their companies. [Interview, F5]

We give our oil waste to municipalities in every province we have a contract with. Previously, there were regional companies, but now this is organized by the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization. The separated oils to capture are evaluated and recycled in facilities that produce materials, such as fuel and soap in Turkey. [Interview, F10]

Unilever Turkey became our main sponsor by providing rental support for our studio, raw material shipping cost, full-time salary payment of employees and sharing its waste and providing support in public relations services when we first started. [Interview, F5]

Discussion

Theoretical contributions

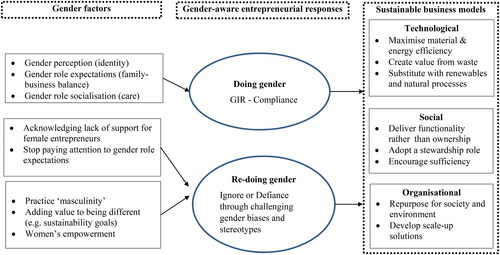

We provide three significant contributions to the gender, entrepreneurship and social policy debate. First, based on our findings, we propose a theoretical framework for uncovering gender influences on sustainable business models in women’s tourism entrepreneurship (). Extending existing understanding of gender influences are evident in the gender-aware entrepreneurial responses that are seen in the decisions and choices of women entrepreneurs (Tucker, Citation2022), our framework depicts the route through which gender influences can be uncovered: gender factors (e.g. gender perception, gender role expectations, gender role socialisation on ethics of care) trigger women’s entrepreneurial responses (doing, and/or re-doing, gender) leading to the development of desired sustainable business model archetypes. Doing gender includes compliance with perceived gender identity and roles while redoing gender consists of women challenging gender differences, biases and stereotypes through their decisions and choices. Doing and re-doing gender, as entrepreneurial responses, manifest how women pursue their sustainable business models by distinctively drawing on social, environmental and technological archetypes.

Figure 3. A framework for gender influences on sustainable business models in women’s tourism entrepreneurship.

The emergent theoretical framework demonstrates the importance of doing and redoing gender in women’s tourism entrepreneurship at the intersection of gender factors, entrepreneurial responses (Diaz-Garcia & Welter, Citation2013; Tlaiss & Kauser, Citation2019) and sustainable business models (Bocken et al., Citation2014; Eger et al., Citation2022; Ferguson & Alarcón, Citation2015). Women entrepreneurs respond to gender factors through compliance, ignorance or defiance. Their response is evidenced in complying with or ignoring gender bias by doing gender (Swail & Marlow, Citation2018); whereas defying gender biases reflects re-doing gender. We suggest that doing and re-doing gender constitute gender-aware entrepreneurial responses because the women entrepreneurs are responding to gender influences (Tucker, Citation2022) by risking their resources in the pursuit of business opportunities (Kimbu & Kimbu, 2016). Thus, we complement the existing debate in sustainable tourism about the gendering of sustainability in not only recognising how sustainability legitimises change and continuity (for women) in relation to tourism (Tucker, Citation2022) but also by providing a framework for understanding the entrepreneurial responses used by women entrepreneurs to seek legitimacy and change through sustainable business model archetypes.

The second theoretical contribution of this study is the fourteen qualitative case studies of sustainable business model archetypes of women entrepreneurs in the tourism sector. When viewed through the lens of sustainable business model archetypes (Bocken et al., Citation2014), we find strong evidence that women entrepreneurs are more likely than men to consider the environmental and social implications of their businesses. Our findings show that sustainability, through ethics of care, is core to the women’s business models in pre-entry, post-entry, or transformation of traditional business models. In the tourism industry of Turkey the focus has so been financial outcomes by men entrepreneurs (Cicek et al., 2017). The case studies demonstrate the relevance of business model thinking as a useful construct (Bocken et al., Citation2014) for understanding the role of women entrepreneurs in sustainable tourism development in a patriarchal tourism destination. Our findings begin to signal what future research might be needed to understand the circumstances under which women entrepreneurs can combine all three archetypes when pursuing tourism entrepreneurship and to what impacts.

Overall, our findings suggests that gender identity construction and gender role compliance are shaping women’s sustainability-driven tourism entrepreneurship in Turkey. Women entrepreneurs incorporate the traditionally feminine characteristics of care and support into their small and medium-sized enterprises. Considering that the tourism industry in Turkey has been called a women-intensive sector (Çiçek et al., Citation2017), gaining legitimacy allows women to experience a highly constructed gender socialisation in a traditionally male-dominated society. Incorporating feminine characteristics and legitimising male dominance reflects the notion of doing gender (Swail & Marlow, Citation2018). Yet, not all the evidence points to compliance with socially constructed gender identities and roles, in relation to owner-managers of tourism businesses. Attempts to resist and defy gendered perceptions constitute redoing gender. This is reflected in women entrepreneurs displaying both feminine and masculine characteristics in their pursuit of tourism entrepreneurship.

In our third contribution, we complement existing studies that have applied the feminist perspective of embracing the masculine or attenuating the feminine (Swail & Marlow, Citation2018). We introduce the ethics of care perspective (Gillian, 1982; Noddings, Citation1984) for identifying gender influences as a key driver for enabling the development of a sustainable business model in an established tourism destination. Ethics of care is relational and processual. Being relational is perceived as a feminine trait that challenges women to gain legitimacy in male-dominated entrepreneurship; however our analysis shows that ethics of care is not only relational but also rational since it allows women entrepreneurs to make logical decisions for the benefit of their businesses (Fors & Lennerfors, Citation2019). For example, creating value from waste by practising ethics of care can protect nature (relational) but also reduce cost savings (rational). Acknowledging research that uncovers the traditional feminine traits of entrepreneurs of all genders as having an influence on entrepreneurial practice (Fors & Lennerfors, Citation2019), we suggest that doing and redoing gender are similarly legitimate strategies in women’s tourism entrepreneurship and sustainable tourism development.

Implications for policy and practice

The findings of this study have practical implications for women entrepreneurs who wish to develop sustainable business models, to secure resources from finance and business support providers, and to operate their businesses in a sustainable manner (Georg et al., Citation2021). At a strategic level, and considering existing patriarchal dominance, it is prudent for women entrepreneurs to consider how doing (compliance and ignore) and redoing (defiance) gender can enhance their pursuit of sustainable business models. Knowing that gender influences can be enablers of, or barriers to, achieving the changes that are needed to ensure the sustainability of their business models, can help women entrepreneurs to consider how to do and redo gender for the benefit of their businesses. External networks are also important for helping women entrepreneurs to redo gender. Our findings suggest that being part of networks, including governmental, multinational corporations and non-governmental organisations (e.g. women’s cooperatives) is important as these networks enable women to gather information, resources and advice.

In terms of policy implications, the Turkish government has developed environmental legislation that encourages the incorporation of sustainability practices in the tourism sector (Guzeloglu & Gulc, Citation2021). Without actively encouraging women-owned tourism businesses to improve their environmental performance by adopting environmental practices that adhere to these legislations, the role of women in promoting sustainable development through tourism can be undermined. As the OECD (Citation2021) entrepreneurship policy report highlights, the role of women entrepreneurs in the tourism sector, and how they were affected more than men entrepreneurs during the COVID-19 pandemic. The women entrepreneurs we studied, faced difficulties in securing buy-in from environmentally-focused suppliers and customers because of the lack of audited evidence of their compliance with environmental legislation. This example demonstrates why women’s entrepreneurship policy needs to be better contextualised. The government needs to increase the awareness and usage of environmental legislation in the tourism industry, similar to what is currently being done in the Turkish energy-related sectors (Guzeloglu & Gulc, Citation2021). As suggested by Kimbu et al. (2019), networks that support women entrepreneurs are effective in facilitating the exchange of information among government, and private sector, resource providers (e.g. financial providers) and in linking women-owned businesses to markets.

A major challenge facing government authorities is where tourism policymaking occurs in isolation from environmental policymaking, especially due to the ministerial structures of government (Kim & Bramwell, Citation2019). Supportive social policies that incentivise greater access to finance, and reduce the number of bottlenecks facing women entrepreneurs, should be viewed as complementary to environmental and tourism policies. Rather than view women entrepreneurs through a gender-equal or gender-neutral lens, the right framework condition is gender-aware (Ahl & Nelson, Citation2015). This includes investing in public infrastructure that is relevant to women (e.g. funded nursery schools and sanitary facilities). Such investment can complement the support that targets all businesses (e.g. easing market access through targeted tax incentives that reward environmentally focused, sustainable business models). Delayed governmental action, such as investments and tax incentives, could lead to business closures since the opportunity to help save entrepreneurs’ businesses, and/or revive them, immediately after the pandemic will have been lost, further disadvantaging women in the post COVID-19 pandemic era.

Conclusion

Through qualitative case studies of women-owned businesses developed in Turkey, this article derives a theoretical framework for uncovering gender influences on sustainable business models. Women entrepreneurs pursue sustainable business model archetypes (Bocken et al., Citation2014) through entrepreneurial responses to context-specific gender factors that influence their engagement in sustainability (Tucker, Citation2022). The findings reveal that: (i) women entrepreneurs create value that is financial/economic and societal (solving societal and/or environmental problems); and (ii) gender factors influence women’s pursuit of sustainable business models (e.g. Manolova et al., Citation2020). Our findings suggest that women entrepreneurs in the tourism industry differ from their male counterparts in their attitudes and behaviours in that they are more likely to consider the environmental implications of their businesses.

Our purposive sampling focused on 14 women-owned tourism businesses in Turkey to derive a theoretical framework from empirical case studies. The limited sample can be viewed as a limitation. Future research that applies our proposed framework () to study women entrepreneurs in other regions of Turkey, or other tourism destinations, can strengthen the generalisability of the findings. Future research applying the ethics of care perspective to cross-national gender influences (Noddings, Citation1984) or to contrast men and women entrepreneurs can advance our theoretical insight. Future research should also consider women entrepreneurs who aspire to engage in sustainability but have not created/operated sustainable business models, due to the gender biases we uncovered. For progressive social policy to impact more women entrepreneurs, all women entrepreneurs require support, irrespective of whether or not they have adopted sustainable business model archetypes.

Though not our primary focus, much of our data collection occurred during the COVID-19 period, which was characterised by severe travel restrictions. The women entrepreneurs spoke about business closures, cancellations of sales and supplies, and the consequent loss of revenue. Future research is needed to interrogate why the women were often more badly affected by the pandemic than men through in-depth study of the impact of the pandemic, and the women’s interpretations of it. According to Manolova et al. (Citation2020) women entrepreneurs should take advantage of opportunities created by COVID-19. Seven of our interviews were rescheduled and conducted via Skype, an adaptation that reflects the increased use of digital technology for businesses to infuse sustainability into their business models (George et al., Citation2021). Qualitative and quantitative research can enhance knowledge about how women tourism entrepreneurs are pivoting their sustainable business models in the highly uncertain, and digitally enabled, post-pandemic environment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gizem Kutlu

Gizem Kutlu completed her PhD in Management at the Department of Public Leadership and Social Enterprise at The Open University Business School, UK. She recently started work as a Lecturer in Business and Management at Coventry University London. Her research and teaching interests have a primary focus on the intersection of environmental entrepreneurship, sustainability, and gender. Her current research explores how gender (gender identity/role) influences sustainable practices of women-owned and men-owned SMEs in Turkey.

Michael Z. Ngoasong

Michael Z. Ngoasong is a Senior Lecturer in Management and Head of Department for Public Leadership and Social Enterprise at The Open University Business School, UK. He is also a Senior Research Associate, School of Tourism and Hospitality, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Michael has conducted externally funded research projects ondevelopment-led tourism entrepreneurship, digital entrepreneurship, women entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship in emerging and transforming economies.

References

- Ahl, H., & Nelson, T. (2015). How policy positions women entrepreneurs: A comparative analysis of state discourse in Sweden and the United States. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(2), 273–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.08.002

- Alarcón, D. M., & Cole, S. (2019). No sustainability for tourism without gender equality. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 903–919. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1588283

- Beechey, V. (1979). On Patriarchy. Feminist Review, (3), 66. https://doi.org/10.2307/1394710

- Bocken, N. M. P., Short, S. W., Rana, P., & Evans, S. (2014). A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. Journal of Cleaner Production, 65, 42–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.11.039

- Boonabaana, B. (2014). Negotiating gender and tourism work: Women’s lived experiences in Uganda. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(1–2), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358414529578

- Boons, F., Montalvo, C., Quist, J., & Wagner, M. (2013). Sustainable innovation, business models and economic performance: An overview. Journal of Cleaner Production, 45, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.08.013

- Braun, P. (2010). Going green: Women entrepreneurs and the environment. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 2(3), 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566261011079233

- Bruton, G. D., Khavul, S., & Chavez, H. (2011). Microlending in emerging economies: Building a new line of inquiry from the ground up. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 718–739. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.58

- Chodorow, N. (1971). Being and doing: A cross-cultural examination of the socialization of males and females. Gornick and Moran.

- Cicek, D., Zencir, E., & Kozak, N. (2017). Women in Turkish tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 31, 228–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2017.03.006

- CP/RAC. (2012). Green entrepreneurship in Turkey. Regional Activity Center for Cleaner Production Report 2011, Mediterranean Action Plan.

- Decrop, A. (1999). Triangulation in qualitative tourism research. Tourism Management, 20(1), 157–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00102-2

- Diaz-Garcia, M. C. D., & Welter, F. (2013). Gender identities and practices: Interpreting women entrepreneurs’ narratives. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 31(4), 384–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242611422829

- Dunk, R. M., Gillespie, S. A., & MacLeod, D. (2016). Participation and retention in a green tourism certification scheme. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(12), 1585–1603. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1134558

- Eger, C., Munar, A. M., & Hsu, C. (2022). Gender and tourism sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1459–1475. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1963975

- Eraydın, A., & Türkün-Erendil, A. (2002). Konfeksiyon sanayiinde yeniden yapılanma süreci, degisen kosullar ve kadın emegi: ne kazandılar, ne kaybettiler? Iktisat Dergisi, 430, 2425.

- Ferguson, L., & Alarcón, D. M. (2015). Gender and sustainable tourism: Reflections on theory and practice. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(3), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.957208

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., Kimbu, A., de Jong, A., & Williams, A. M. (2020). Sustainability through the tourism entrepreneurship journey: A gender perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1562–1585. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1831001

- Fors, P., & Lennerfors, T. T. (2019). The individual-care nexus: A theory of entrepreneurial care for sustainable entrepreneurship. Sustainability, 11(18), 4904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184904

- Gast, J., Gundolf, K., & Cesinger, B. (2017). Doing business in a green way: A systematic review of the ecological sustainability entrepreneurship literature and future research directions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 147, 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.065

- GEM. (2021). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2021/2022 global report: Opportunity amid disruption. London.

- GEM. (2021). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2021/2022 global report: Women’s entrepreneurship, thriving through crises.

- George, G., Merrill, R. K., & Schillebeeck, S. J. D. (2021). Digital sustainability and entrepreneurship: How digital innovations are helping tackle climate change and sustainable development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(5), 999–1027. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258719899425

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press.

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Guzeloglu, F. T., & Gulc, A. (2021). Sustainable tourism projects in Turkey. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 5(1), 55–73.

- Hawk, T. F. (2011). An ethic of care: A relational ethic for the relational characteristics of organizations. In Applying care ethics to business (pp. 3–34).

- Hechavarría, D. M. (2016). Mother nature’s son? The impact of gender socialization and culture on environmental venturing. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 137–172. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-10-2015-0038

- Held, V. (2014). The ethics of care as normative guidance: Comment on Gilligan. Journal of Social Philosophy, 45(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/josp.12051

- Holmes, A. G. D. (2020). Researcher positionality - A consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research - a new researcher guide. International Journal of Education, 8(4), 1–10.

- Jennings, G. R. (2005). Interviewing: A focus on qualitative techniques. In B. W. Ritchie, P. Burns, & C. Palmer (Eds.). Tourism research methods: Integrating theory with practice (pp. 99–117). CABI.

- Jørgensen, M. T., Hansen, A. V., Sørensen, F., Fuglsang, L., Sundbo, J., & Jensen, J. F. (2021). Collective tourism social entrepreneurship: A means for community mobilization and social transformation. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103171

- Pla-Julián, I., & Guevara, S. (2019). Is circular economy the key to transitioning towards sustainable development? Challenges from the perspective of care ethics. Futures, 105, 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.09.001

- Kim, S., & Bramwell, B. (2019). Boundaries and boundary crossing in tourism: A study of policy work for tourism and urban regeneration. Tourism Management, 75, 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.04.019

- Kimbu, A. N., Ngoasong, M. Z., Adeola, O., & Afenyo-Agbe, E. (2019). Collaborative Networks for Sustainable Human Capital Management in Women’s Tourism Entrepreneurship: The Role of Tourism Policy. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1556329

- Kimbu, A. N., & Ngoasong, M. Z. (2016). Women as vectors of social entrepreneurship. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.06.002

- Maden, C. (2015). A gendered lens on entrepreneurship: Women entrepreneurship in Turkey. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 30(4), 312–331. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-11-2013-0131

- Manolova, T. S., Brush, C. G., Edelman, L. F., & Elam, A. (2020). Pivoting to stay the course: How women entrepreneurs take advantage of opportunities created by the COVID-19 pandemic. International Small Business Journal, 38(6), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242620949136

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook and the coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

- Ministry of Culture and Tourism. (2020). Tourism strategy of Turkey 2023 and action plan. Retrieve from https://www.ktb.gov.tr/Eklenti/43537,turkeytourismstrategy2023pdf.pdf?0&_tag1=796689BB12A540BE0672E65E48D10C07D6DAE291

- Minnaert, L., Maitland, R., & Miller, G. (2009). Tourism and social policy: The value of social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(2), 316–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.01.002

- Ngoasong, M. Z., & Kimbu, A. N. (2019). Why hurry? The slow process of growth in women-owned businesses in resource-scarce contexts. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 40–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12493

- Noddings, N. (1984). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education. University of California Press.

- OECD. (2021). Entrepreneurship policies through a gender lens. OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship. OECD Publishing, Paris, 1–169.

- OECD. (2008). Gender and sustainable development: Maximising the economic, social and environmental role of women.

- OECD. (2020). Tourism trends and policies.

- Outsios, G., & Farooqi, S. A. (2017). Gender in sustainable entrepreneurship: Evidence from the UK. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 32(3), 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-12-2015-0111

- Pettersson, K., & Heldt Cassel, S. (2014). Women tourism entrepreneurs: Doing gender on farms in Sweden. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 29(8), 487–504. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-02-2014-0016

- Samad, S., & Alharthi, A. (2022). Untangling factors influencing women entrepreneurs’ involvement in tourism and its impact on sustainable tourism development. Administrative Sciences, 12(2), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12020052

- Sanghera, G. S., & Thapar-Björkert, S. (2008). Methodological dilemmas: Gatekeepers and positionality in Bradford. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 31(3), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701491952

- Sarigil, B. O., & Sarigil, Z. (2021). Who is patriarchal? The correlates of patriarchy in Turkey. South European Society and Politics, 26(1), 27–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2021.1924986

- Sefer, B. (2020). A gender- and class-sensitive explanatory model for rural women entrepreneurship in Turkey. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 12(2), 191–210.

- Swail, J., & Marlow, S. (2018). Embrace the masculine; attenuate the feminine’ – gender, identity work and entrepreneurial legitimation in the nascent context. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 30(1-2), 256–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1406539

- Thams, Y., Bendell, B. L., & Terjesen, S. (2018). Explaining women’s presence on corporate boards: The institutionalization of progressive gender-related policies. Journal of Business Research, 86, 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.043

- Tlaiss, H. A., & Kauser, S. (2019). Entrepreneurial leadership, patriarchy, gender, and identity in the Arab World: Lebanon in focus. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(2), 517–537. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12397

- Tucker, H. (2022). Gendering sustainability’s contradictions: Between change and continuity. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1500–1517. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1839902

- UN Women. (2018a). Gender equality in the 2030 Agenda: Gender-responsive water and sanitation systems.

- UN Women. (2018b). Turning promises into action: Gender equality in the 2030 agenda for sustainable development.

- Uslu, Y. D., Hancıoğlu, Y., & Demir, E. (2015). Applicability to Green Entrepreneurship in Turkey: A Situation Analysis. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 1238–1245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.266

- Vatansever, Ç., & Arun, K. (2016). What color is the green entrepreneurship in Turkey? Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 8(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-07-2015-0042

- Walby, S. (1989). Theorising patriarchy. Sociology, 23(2), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038589023002004

- WFID. (2022). Towards women’s financial inclusion: A gender data diagnostic of Turkey.

- Wu, J., & Si, S. (2018). Poverty reduction through entrepreneurship: Incentives, social networks, and sustainability. Asian Business & Management, 17(4), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-018-0039-5

- Yachin, J. M., & Ioannides, D. (2020). Making do in rural tourism: The resourcing behaviour of tourism micro-firms. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(7), 1003–1021. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1715993

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research methods (4th Ed.). Sage.

- Zhang, L., & Zhang, J. (2018). Perception of small tourism enterprises in Lao PDR regarding social sustainability under the influence of social network. Tourism Management, 69, 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.05.012