Abstract

The present article offers the first quantitative history of behavioural economics (BE) from the 1970s to the 2010s. We document the foundation of the field by Kahneman and Tversky in the 1980s and 1990s; the separation of experimental market economics and BE in the 1990s; the decreasing importance of psychology in the 1990s onward; and the rise of European authors after the 2000s. Overall, we show that after the 1990s, BE transformed from a unified American research program with a clearly identifiable core, to a multipolar and international research program with relatively independent subspecialties. Despite claims that BE is mostly an empirical venture, we show that the field is heavily structured by theoretical contributions. A handful of seminal models capture most of the citations in the field and explain how the subspecialties in BE emerged, stabilised, and became more autonomous from the historical core.

1. Introduction

Behavioural economicsFootnote1 (BE) emerged at the end of the 1970s. In the early years of the program, BE was easy to identify: it was comprised of a handful of individuals working in a well identified research program within the Sloan Foundation and Russell Sage Foundation between 1984 and 1992. For historians, BE was mostly identified by this institutional affiliation.

After the 1990s, the success of BE grew exponentially (Geiger Citation2017). Foundational BE theorists, Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler, won the Nobel Prize in economics in 2002 and 2017, respectively, thus consolidating the dominant position of the research program in economics. A second and third generation of behavioural economists emerged as the historical figures of the field grew older, and the research themes of the program diversified.

One attempt to tell the history of BE is undertaken by Heukelom (Citation2014), who provides a comprehensive account of both the context in which BE emerged in the 1970s and the program’s evolution in the Sloan-Sage Foundations up to mid-1990s. This time frame comprises a particularly important period for BE. It covers the evolution of a “small research program” into a “dominant” one (Heukelom Citation2014, 199), the emergence of the intertemporal choice and dual-system approach as among the main legacies of the initial program (Heukelom Citation2014,172), and the emerging distinction between BE and the experimental market economics (EME) approach of Vernon SmithFootnote2 at the end of the 1980s (Heukelom Citation2014, 187; Svorenčík Citation2016).

More generally, plenty of attention has been devoted in the historical literature to the origins of BE from the 1950s to the 1980s, with a central focus on contributions made by Kahneman and Amos Tversky. However, in subsequent decades, BE became increasingly difficult to precisely pinpoint to a single institution, journal, or set of authors. In turn, telling the story of BE as a research program became more daunting. As argued by Angner (Citation2019), BE’s success means that all of economics are now a little bit of BE. This has led historians of the field to approach BE through specific studies that only capture part of the more global history of the program, with a focus on certain subspecialties and very specific historical episodes (Svorenčík Citation2016; Grüne-Yanoff Citation2016; Lisciandra Citation2018).

One way to improve on the existing historical literature is to use quantitative tools that are particularly helpful for assessing large research fields spanning over multiple decades (Claveau and Gingras Citation2016; Cherrier and Svorenčík Citation2018). In the case of BE, such tools are particularly beneficial for linking what is already known from the historical literature about the early years of the program to what has yet to be documented about the more recent transformations of BE. The present article offers the first quantitative history of BE from the 1970s to the 2010s.

Most notably, the analysis presented here shows how BE transformed from a unified and centralised American research program with a clearly identifiable core to a multipolar, decentralised, and international research program with relatively independent subspecialties. These new subspecialties became stabilised and structured around a handful of theoretical contributions, which account for most of the citations in BE. In other words, although it is often claimed that BE makes economics more empirical and applied (Chetty Citation2015), theoretical contributions retain a central role in how the field is structured.

2. Methodology

2.1. Corpus

BE cannot be simply reduced to a set of journals, authors, or institutions, especially after the 2000s when the program grew very rapidly.Footnote3 In the quantitative literature, two strategies that have been used to identify the BE. The key-word approach consists in looking for articles with relevant keywords, and finding related articles from there (Levallois et al. Citation2012; Geiger Citation2017). The literature approach consist in identifying a set of literature reviews and handbooks on BE to form a corpus of the most important articles in the field (Braesemann Citation2019).

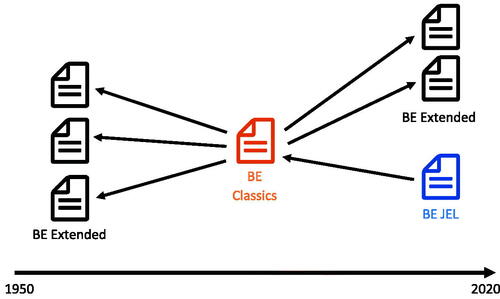

For the present article, we chose to employ a four-step approach using JEL codes and combining data from Clarivate’s Web of Science (WoS) and EconLit ():

STEP 1. JEL corpus: We compiled all articles considered to be BE in EconLit, based on the following JEL codes: Micro-Based Behavioural Economics, Macro-Based Behavioural Economics, Behavioural Finance, and Neuroeconomics.

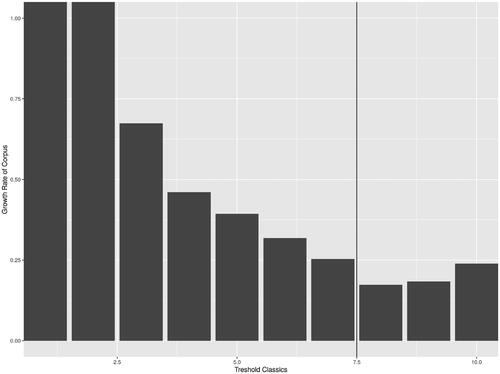

STEP 2. CLASSICS corpus: We compiled the CLASSICS of our JEL corpus, which included all articles that were cited by at least eight articles in our JEL corpus.

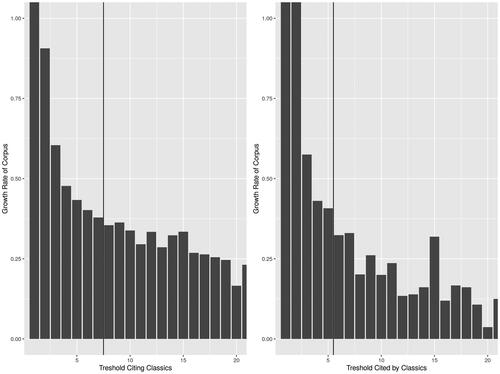

STEP 3. EXTENDED corpus: We compiled all articles that cited at least eight articles from our CLASSICS corpus or that were cited by at least six articles in our CLASSICS corpus.

STEP 4. Final corpus: We combined our CLASSICS corpus and EXTENDED corpus.

To create our initial JEL corpus, we used JEL codes to generate a list of 2,369 articles published between 2003 and 2016, and we successfully identified 1,054 articles in WoS. On their own, JEL codes are not enough to identify BE publications because they only capture economics article, and post 2000s articles. Therefore, they cannot capture alone how the field emerged in the 1980s or how it evolved in the decades afterwards.

To compile articles defined as the CLASSICS of BE, we identified 446 commonly referenced articles that were cited by at least eight of the articles from our JEL corpus. The CLASSICS articles span a larger time period than the JEL articles because some of them were published as early as the 1950s; they span multiple disciplines; and they are important to behavioural economists. To chose the citation threshold for the CLASSICS corpus, we examined the growth rate of the corpus at different thresholds, and we stopped when the growth rate increased rapidly (Appendix 9.1).

Next, we created an EXTENDED corpus by identifying articles that are strongly related to those included in our CLASSICS corpus. We compiled articles that cite at least eight of the articles from our CLASSICS corpus, as well as those that are cited by at least six of the articles in our CLASSICS corpus (Appendix 9.1). This citation threshold enabled us to capture articles strongly related to BE: they talk about BE and are talked about in BE.

Finally, we combined the articles from our CLASSICS corpus and EXTENDED corpus. It is worth noting that the vast majority of CLASSICS articles were already recaptured in step 3. The final corpus included 5,423 articles, published between 1945 and 2018.

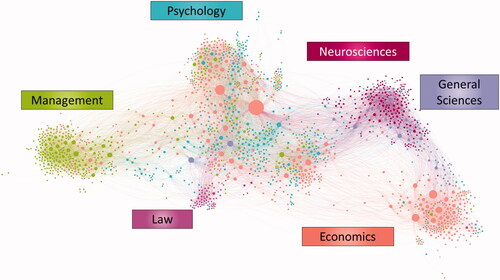

To identify the discipline of the journal in which each article in the final corpus was published, we used the US National Science Foundation (NSF) classification system. This system includes 143 fields of research (e.g., sociology, psychiatry), which are themselves grouped under two large domains: natural sciences, engineering, and biomedical sciences (NSE) and social sciences and humanities (SSH). For our own classification, we first grouped nine sub-categories of psychology into one category, and we focussed our attention on the most highly represented disciplines within the final corpus: economics, management, psychology, neurosciences, general sciences, law and others.

In Section 7, we also study author affiliation. Studying affiliation raises multiple questions. How to handle author with multiple affiliations or how to compare countries with vastly different organizations? For example, France has one central research institutions with the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique that almost always end up as the most occurring one because many researchers are associated with it one way or another. At the opposite, in Germany, the Max Planck Institutes is split in multiple institutes, which makes the Max Planck either rare (when institutes are counted as unique institutions) or the top institutions (when institutes are grouped).

In our case, we face an additional challenge. Author affiliation was determined using information about authors in the Web of Science database. However, affiliations are not per author, but instead per institutional departments. For example, in the case of an article with two authors from the same department, the department (and institution or country associated with it) is only counted once. Similarly, a single-authored article where the author has three affiliations can result in one article having three affiliations. While in some cases we can inferred the institutional affiliation for each author (e.g., one institution, multiple authors), in others we can’t (e.g., two institutions, three authors).

For the purpose of this article, we are mainly interested in the relationship between European and American research groups. Namely, how much collaboration we observe between the two groups, and what are their relative importance over time. Therefore, to mitigate some of the biases induced by the ways the database is structured, we restructure the information in two ways. First, for each article, we only kept one occurrence of each unique institutions (university, research institute…) to avoid the multiplication of observations resulting from the variety of departments observed in some institutions. In other words, for each article, authors are group by their institutional affiliation as research team. For example, in an article with two authors from Princeton and one author from Stanford, we only know that the article was written by one team from Princeton and one from Stanford, but not that the individual ratio was two third. Second, and more importantly, for the purpose of our analysis, we mostly looked at the share of papers authored by European and American economists. While we do not have individual affiliation, we know with certainty when a paper has only European authors, only American authors, or a mix of the two. To study the internationalisation of behavioural economics (Section 7), we based our analysis on this reliable information rather than on approximation resulting from counting occurrences (Appendix 9.3).

In the Appendices 9.3 and 9.4 we still counted the occurrence of countries and institutions using our per-research team approximation. Given the relatively low number of co-authors in economics, we believe that this approximation should not be too far off from what we could observe on a per-author basis, however, it remains only an approximation to find the top occurring institutions. For our analysis, we only used the table from Appendix 9.4 (most occurring institutions in each non-US country) to identify the most occurring non-American institutions in our corpus. This is only used to cross-check our narrative and the literature in relation to what we know about the development of a European behavioural economics rather than as a quantitative evaluation.

2.2. Analysis

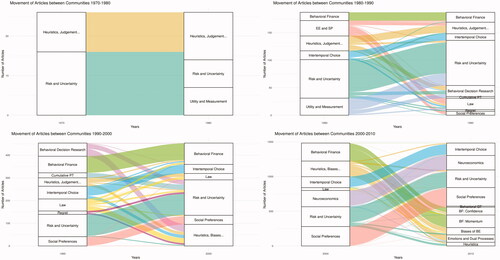

From our corpus, we built co-citation networks by decade, from the 1970s to the 2010s.Footnote4 We built co-citation networks using the references of our corpus. When a given article in the BE literature cited two other articles, a link was created between the two articles. This particular approach provided us an indication of the relationship between the two articles, with the added advantage of creating some continuity between networks. For example, a reference that remained important across all decades was present in all of the networks, even when the corpus between two decades was completely different. This enabled easier comparisons between periods, as there was less sensitivity to the bounds of the chosen time frame. The chosen bounds were centred around Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979), which is often considered to be the foundational text of BE. The networks offer a good indication of how behavioural economists’ citations transformed 10, 20, 30, and 40 years after the publication of this foundational article.

While behavioural economics has been approached quantitatively to investigate the increasing importance of the field (Geiger Citation2017) or the relationship between economics and psychology Braesemann (Citation2019), studying the structural evolution of the field using network analysis has yet to be done. Network analysis has, for example, been used to the evolution of all economics by Claveau and Gingras (Citation2016). Our approach differs in two ways. We focussed on a sub-field of economics rather than all economics, and we used co-citation analysis rather than bibliographic coupling. These two characteristics makes our work closer to Truc, Claveau, and Santerre (Citation2021) who investigated the evolution of economics methodology through time.

To build our networks, we excluded the weakest co-citation links, using a threshold where all documents that were co-cited less than τ times have no link. To make networks easier to compute and more readable, we chose varied thresholds for different decades as the corpus increased in size. We set the threshold value for each decade at a point where it made the growth rate of the corpus increase rapidly, while also taking other considerations into account, such as computation constraints, readability, and comparability between networks. The chosen thresholds make cardinal metrics more difficult to use, as we did not build all networks using the same τ value. However, some comparisons are possible, as some decades have the same τ value (). Moreover, we also used ordinal metrics to ensure that intertemporal comparisons are still possible.

Table 1. Chosen thresholds.

We weighted the strength of the relationship between two co-cited articles using cosine similarity. The strength of two co-cited articles in an individual article is inversely proportional to the overall citation count of the co-cited documents. For example, an article like Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) is cited by the majority of the corpus. Therefore, the probability that an article will be co-cited with Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) is very high and does not necessarily indicate a significant relationship unless it happens very often.

One caveat of the WoS database is that books are neglected, both as contributions and in references. Therefore, our study largely ignore the influence of books. Moreover, while all identified references were used to construct our network, identify our clusters, and build our narrative, the final visualisation of our networks only includes references for which we could identify an associated discipline. This does not impact the results in the paper except for the fact that the share of disciplines in the network is computed on the number of references with an identified discipline rather than the total number of references.

The focus of our analysis was the evolution of the structure of networks between decades and, more particularly, the evolution of clusters within networks. We detected clusters with a Leiden modularity-based algorithm (Traag, Waltman, and van Eck Citation2019), using the same parameters between decades.Footnote5 To interpret and name these clusters, we used a combination of metrics. We identified the most distinctive concepts of each cluster by applying the term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) to the titles of documents in the cluster. We also looked at the most represented disciplines in the cluster, the top articles, and the top authors. To identify stable clusters across decades, we paid particular attention to the stability of distinctive concepts between decades, the movement of articles between clusters, and a selection of top references (Appendix 9.2). Finally, although we named most clusters based on their distinctive concepts, we also drew on our own expertise to determine how to best interpret and name the clusters. For example, we renamed the term “effect,” which was very distinctive of some clusters focussed on particular biases, to “biases,” in order to reflect the concept’s particular usage in BE (e.g., endowment effect, default effect).

In the final visualisation of our networks, we positioned each individual reference (nodes) using Force Atlas 2, a force-based layout that reduce crossing links (edges) as much as possible. While clusters and positions are determined using two different approaches, one strength of visualising networks is that it allows us to cross-check both sources of information: clusters (colour-coded using Leiden) tend to be spatially grouped together (positions using Force Atlas 2) despite both procedures being independent.

Co-citation networks can be interpreted as a representation of the way the discussion and literature is structured within behavioural economics. In our case, references that tend to be cited together are understood as part of the same cognitive specialty (Claveau and Gingras Citation2016), and therefore, tend to be part of the same clusters and spatially close to each other. At the opposite, if two clusters have nothing in common in their literature, then we should find two clusters with no link between them. While the spatial positions approximate proximity or similarity between clusters, it is not enough. The reduction of all the information to a two-dimensional space is only an approximation of the complex relationship observed. To complete our analysis, we used different metrics to measure what is observed visually. For example, visually, clusters that appear far from most of the network can be considered “separated” from the rest of the network. While it is true visually, one way to confirm that is to look at how independent these clusters are from the rest of the network. To achieve that, we used an inwardness indicator () to measure how independent clusters are from the rest of the network. In other words, in the case of behavioural finance, this indicator gives us a clue about how much do researchers in behavioural finance rely (or not) on research from the rest of behavioural economics relatively to their own.

Table 2. Weighted share of inward links by cluster.

In a co-citation network, each node is a reference. Unlike researchers network, nodes do not represent individual. Two references in the same cluster might include individuals that are part of very different institutional or co-authorship networks, however they are considered part of the same cluster because their contributions are part of the same literature. We can still learn a lot about individual positions in behavioural economics by the way individuals circulate (or not) between these different clusters. Looking at all the articles of a given author in the network informs us about how individual specialise and contribute (or not) to different specialties. Most authors, tend to have their article in the same clusters. Like in the case of disciplinary boundaries, moving between cognitive specialties is hard, especially when two specialties have little in common (MacLeod Citation2018). Thus, most researchers tend to contribute actively to one or two research specialty. For example, if one where to look up all Ernst Fehr’s articles, we would find that most of his contributions are in the Social Preferences and the Neuroeconomics clusters. At the opposite, some researchers cross thick boundaries. For example, we find very few authors that contribute to both Behavioural Finance and Intertemporal Choice. However, Richard Thaler is one exception. Being both the founder of Behavioural Finance, and one of the founders of Behavioural economics, Thaler contributed actively to both clusters from the early days (Thaler Citation1980, Citation1981; De Bondt and Thaler Citation1985), a rare feat considering that Behavioural Finance is a very independent specialty from the rest of BE (). Co-citations networks, despite not representing individuals, allows us to track how, when and which of Thaler’s contributions are important in behavioural economics.

3. The 1970s: the emergence of a behavioral economics community

3.1. The origins of the program: a short contextual history

During the 1950s and 1960s, the University of Michigan’s psychology department garnered success and grew rapidly. It is often considered to be one of the main sources of origin for BE (Heukelom Citation2010). It hosted multiple research programs that aimed to weaken the separation between economics and psychology. These included, among others, George Katona’s survey of consumer behaviour, Clyde Coombs’ mathematical psychology, and Ward Edwards’ behavioural decision research.

Clyde Coombs was a student of L. L. Thurstone. He developed mathematical psychology, a research program that would be defined by its mathematical approach rather than by its subject content (Coombs, Dawes, and Tversky Citation1970), meaning that it could be applied to a wide range of phenomena. Ward Edwards was the son of an economist, and he studied psychology at Harvard University under the influence of Frederick Mosteller, a statistician and psychometrician who attempted, with Philip Nogee in 1951 (Mosteller and Nogee Citation1951), to experimentally measure how individuals value additional money income. The results of these experiments suggested that individuals engage in optimisation and that additional money income has diminishing marginal utility. However, these experiments also demonstrated many of the practical difficulties of measuring economic utility experimentally (Heukelom Citation2014, 37). In 1958, Edwards moved to the University of Michigan and developed his own program, the experimental counterpart to Coombs’ mathematical psychology, and focussed on investigating Leonard Savage’s decision theory in experimental settings.

At this point in history, economists, particularly after Friedman (Citation1953), understood behavioural axioms to be positive theories — general characterisations of human behaviour. However, psychologists understood those axioms to be normative benchmarks to be empirically investigated (Heukelom Citation2010, 200). Following this interpretation, it appeared to psychologists that the role of economists was to develop a normative decision theory — a general characterisation of what rational behaviour ought to be — while psychologists should investigate how closely people follow this normative benchmark. This Michigan approach was very successful up until the 1970s, but as various important members moved to other institutions or retired, and as the visibility of mathematical psychology and behavioural decision making decreased in importance, the importance of Michigan in psychology subsided (Heukelom Citation2014, 95). However, the division of labour between economic theory as a normative benchmark, and psychology as a descriptive approach lived up, and was taken up by some of Edwards student like Slovic, Lichtenstein, and Tversky who developed a critical perspective on economic theory.

Amos Tversky obtained his PhD under the supervision of Edwards and Coombs, and he contributed actively to mathematical psychology, the theoretical counterpart to Edwards’ empirical approach. Tversky left Michigan in 1969 to return to his alma mater, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where he met Daniel Kahneman. While Tversky was a student of Edwards and Coombs, Kahneman was not. Most of Kahneman’s research before the 1970s focussed on investigating the psychology of vision using experiments. The collaboration that subsequently emerged between Kahneman and Tversky was particularly fruitful, as Tversky could provide Kahneman with a normative framework for experimentally testing behaviour deviations, and Kahneman could provide Tversky with insight into the empirical validity of Savage and Edwards’ assumptions. In the 1970s, Tversky and Kahneman started a collaboration that would lead to the development of two foundational texts in BE (Tversky and Kahneman Citation1974; Kahneman and Tversky Citation1979). Along with other psychologists such Paul Slovic and Sarah Lichtenstein, who were also former students of Edwards, they developed an approach that aimed to identify systematic departures from John Von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern’s axiomatic approach, while maintaining the role of that axiomatic approach as a normative theory. This led to the identification of two important systematic deviations, with Lichtenstein and Slovic (Citation1971)’s preference reversal and Tversky and Kahneman (Citation1974)’s heuristics approach.

In parallel to this American movement towards more psychology in economics, German economists also developed an interest for experiments in the 1950s. A small group initiated by Heinz Sauermann, with Reinhard Selten as one of the early and most prominent members of the group, brought economics and psychology closer thought experiments (Maas and Svorenčík Citation2016, 192). Reinhard Selten played an important role in the development of experimental economics in Germany (and Europe) and became one of the founders of the German Society for Experimental Economics Research in the 1977s (Svorenčík Citation2021). While not directly related to the heuristics and biases program of Kahneman and Tversky, this group of researchers in Europe was interested in increasing the collaboration between psychologists and economists,Footnote6 and by bounded rationality approaches in economics.Footnote7 This interest for psychology led to the emergence of what some have called the “Selten School of Behavioral Economics” (Selten, Ockenfels, and Sadrieh Citation2010).

While this community formed before the Heuristics and Biases program in the United-States, behavioural economics (and more largely experimental economics) remained a US-dominated field from the 1970s to the 2000s (Section 4). However, despite the lack of influence of the German community on the international scene in the early years of BE, we find that the German tradition remained strong throughout the years, and found a place within the program as the European influence grew in the 2000s (Section 7).

3.2. Critical Experiments bridging psychology and economics

Our corpus was not made to investigate the origins of BE, but rather the formation of BE itself. In the 1970s, BE understood as the heuristics and biases program did not exactly exist. However, the 1970s co-citation network offers a good starting point for investigating the structural transformation of BE over the years.

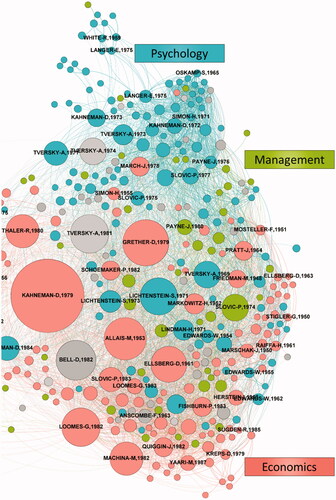

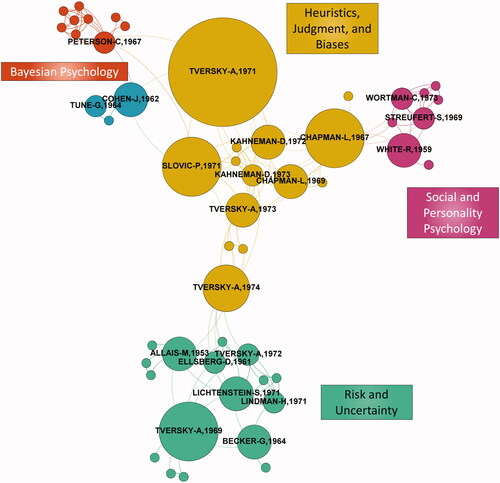

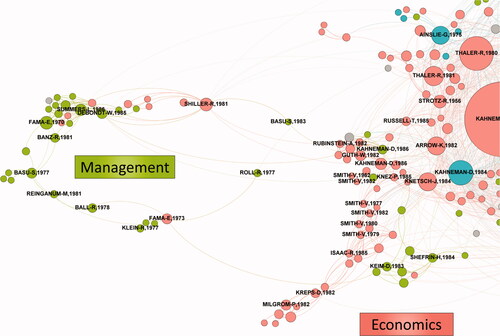

The 1970s network is dominated by psychology articles, with 86% of its nodes situated in that discipline. We find that most of the relevant actors needed to understand the emergence of BE are identified, with key articles by Tversky, Kahneman, Slovic, and Lichtenstein. These publications are all heavily connected and cited, indicating that a successful intellectual community emerged during the 1970s around the work of these four main actors (). At the margin of this historical core, we also find older psychology references from the 1960s, from the subfields of Bayesian psychology, where some of the work of Edwards is found, and social and personality psychology.

Figure 2. Co-citations of articles published between 1970 and 1979 (node size = citations by the corpus, colour-coded by clusters, τ = 2, network generated from the references of 39 articles). Grey nodes are smaller-clusters.

One notable structural element of the 1970s network is the separation that existed between topics related to psychology (biases and heuristics) and topics related to economics (risk and uncertainty). All of the articles published in the fields of management and economics are situated in the risk and uncertainty cluster. References to economics indicate that the BE program was already understood to be a critical assessment of economics. We find Friedman and Savage (Citation1948) cited in relation to the Friedman-Savage utility function, which would serve as a theoretical benchmark for many experiments. We also find some of the most important proto-experimentalists: Becker, Degroot, and Marschak (Citation1964), who developed the Becker-DeGroot-Marschak method, most notably used in the endowment effect literature to measure willingness to pay, and Allais (Citation1953) and Ellsberg (Citation1961), who pointed out anomalous predictions resulting from expected utility theory with paradoxes in relation to risk and uncertainty.

A second important element is the role of Tversky and Kahneman (Citation1974) as a bridge between the risk and uncertainty cluster and the heuristics, judgement, and biases cluster. Along with Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979), this was one of Tversky and Kahneman’s most cited articles. It established much of what would become their collaborative research program in relation to heuristics and biases. Other weaker links also exist between the risk and uncertainty cluster and the heuristics, judgement, and biases cluster; however, they are not visible here because we focussed only on the most important co-citations. This fundamental structure points to the central role that Tversky and Kahneman’s collaboration played in bringing these two clusters of literature together.

Finally, we also find that Tversky is much more present than Kahneman in the 1970s network. Most notably, Tversky, Lichtenstein, and Slovic are present in both the risk and uncertainty cluster and the heuristics, judgement, and biases cluster. These researchers worked on both themes before Kahneman and Tversky began to collaborate. Tversky’s articles in the risk and uncertainty cluster are single-authored (Tversky Citation1969, Citation1972), while articles by Kahneman in the heuristics, judgement, and biases cluster are co-authored with Tversky (Kahneman and Tversky Citation1972, Citation1973). Thus, Kahneman and Tversky’s collaboration served as a catalyst to help bring together an existing literature dominated by Tversky, Lichtenstein, and Slovic; before Kahneman began to collaborate with Tversky, his work was almost completely absent from this literature.

4. The 1980s: the Sloan-Sage years

4.1. Prospect theory and the rise of economics

Kahneman and Tversky’s collaborative approach initiated a research program that developed very quickly from the 1980s onwards. Between 1984 and 1992, BE found an anchor with the help of two private foundations, the Sloan Foundation and the Russell Sage Foundation. According to Heukelom (Citation2012, Citation2014), the support of these foundations helped to give BE a “sense of mission” and catalysed different trends of research that would construct BE as a “new behavioural sub-discipline in economics” (Heukelom Citation2014, 149). More particularly, it also crystallised the collaboration between psychologists Kahneman and Tversky with economists such as Richard Thaler. The latter, for example, introduced applied BE to the field of finance and helped to disseminate BE’s ideas to new corners of the economics community.

The BE research program formally emerged in 1984 at the Sloan Foundation under the presidency of Albert Rees, a labour economist from Chicago. He persuaded Eric Wanner, a psychologist with an interest in cognitive sciences, to join the Sloan Foundation as a program officer for the cognitive sciences program in 1982. One year later, Wanner with the support of Rees, proposed a new plan for the application of cognitive sciences in economics, with the help of Kahneman, Tversky, and Thaler. From the start, this program was conceived as highly interdisciplinary, as Wanner and Rees elected a mix of psychologists and economists to its advisory committee (Heukelom Citation2014, 153). Early on, Kahneman and Tversky were concerned about their ability as psychologists to develop models that would be sophisticated enough to have lasting impacts in economics (Heukelom Citation2014, 152). Rapidly, the program became a place where strategical considerations were discussed: how to make BE’s impact in economics more meaningful, what stance should be taken regarding the relationship between BE and neoclassical economics, and how to maintain a balance between economics and psychology in the program (Heukelom Citation2014, 159).

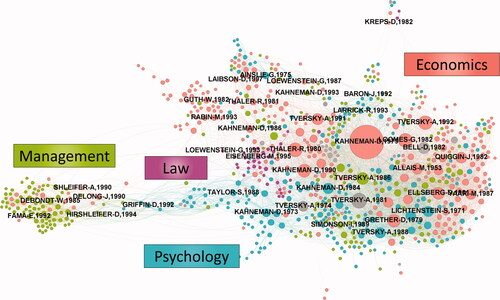

Our analysis of the 1980s co-citation network highlights multiple important transformations in the field during this time period:

Economics gained increasing prominence in BE during the 1980s, as reflected both in the number of articles published in economics journals and in the importance measured by citations. We find that 42% of the nodes are situated in economics, 29% in psychology, and 19% in management.

The “historical core” of BE emerged during this time period, as a main component composed of three clusters, identified below. This historical core is where we find much of the variety of the field in term of disciplines, as well as many members of the Sloan-Sage Foundations.

Multiple new themes emerged, including intertemporal choice, experimental market economics, proto-social preferences, and behavioural finance.

4.2. The formation of BE’s core

We find three main clusters forming BE’s core in the 1980s: heuristics, judgement, and biases; utility and measurement; and risk and uncertainty. The heuristics, judgement, and biases cluster is largely composed of articles published in psychology journals in the 1970s, which were also found in the previous decade’s network. We find very few economics publications in this cluster, which may be understood to comprise the psychological foundations of Kahneman and Tversky’s research program . The utility and measurement cluster is composed of experimental articles in psychology and economics, as well as some older articles such as Mosteller and Nogee (Citation1951) in economics and Edwards (Citation1954) in psychology. Finally, the risk and uncertainty cluster is similar to the cluster of the same name in the previous decade’s network; in the 1980s, however, this body of literature became more oriented towards economics.

Figure 3. Co-citations of articles published between 1980 and 1989 (node size = citations by the corpus, colour-coded by clusters, τ = 2, network generated from the references of 121 articles).

In the 1980s, most of Kahneman, Tversky, Slovic, and Lichtenstein’s articles were still published in psychology journals. However, during this time period, these researchers increased the number of articles they published in economics and helped to bring their psychological program into economics (Kahneman and Tversky Citation1979; Slovic and Lichtenstein Citation1983). Especially after Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979), BE authors increasingly co-cited the psychological literature on risk and uncertainty from the 1960s and 1970s (e.g., Edwards, Tversky, Slovic, and Lichtenstein) with economics articles (e.g., articles by Raiffa, Mosteller, Stigler, Machina, Grether, and Loomes) ().

The plan to bring economics and psychology together under the auspices of the Sloan-Sage Foundations rapidly transformed the research literature. By the 1980s, Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) had become a central reference in bridging an already large psychology literature to the emerging core of BE, focussed on risk and uncertainty. The decreasing importance of Tversky and Kahneman (Citation1974) in the network indicates that BE as an economic program quickly became more oriented towards the question of risk and uncertainty, with a central theoretical economics model, rather than the more general questions of heuristics, judgments, and biases, as framed by psychologists.

The heuristics, judgement, and biases cluster is a foundation cluster that remains very important throughout much of the field’s history, until the 2010s (Appendix 9.2). One particular trait of this cluster is that unlike most clusters, it becomes more outward-looking over time (). In other words, over time, the articles in this cluster are increasingly co-cited with articles outside of the cluster, rather than articles within the cluster. It thus serves as a “resource-cluster” that groups a collection of articles on biases and experiments: its articles are not important because they formed a research program of their own, but rather because authors in other subspecialties of BE used its articles as resources to develop new research directions (Section 6). One possible explanation is that unlike other more stable clusters (e.g., risk and uncertainty, intertemporal choice), this cluster has no central theoretical reference to unify related articles.

Another important development for bridging economics and psychology in the 1980s was the growing contributions of economists in the network. We find Loomes and Sugden (Citation1982), Grether and Plott (Citation1979), and Machina (Citation1982) in the three main clusters of the decade. Proto-experimentalists such as Allais (Citation1953) and Ellsberg (Citation1961) were increasingly cited and remained central in the field. Thaler (Citation1980) also emerged as a central figure of the field, as one of its three main founders.

In the 1970s, the research literature on experimental anomalies linked economics and psychology by its critical dimension. By the 1980s, one of the characteristic features of BE’s core was the association of this experimental literature with new critical theoretical contributions. As observed by Svorenčík (Citation2021, 345) with pioneers of experimental economics like Selten, one driving force of experimental economics was the realisation that “experimental research is most potent when it goes in tandem with economic theory”. Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) cemented the critical literature of the 1970s, with a theoretical contribution oriented towards economics. We also find theoretical contributions from other authors throughout the 1980s, such as the integration of regret in economics by Loomes and Sugden (Citation1982). Sloan-Sage members did not believe that reporting experimental anomalies alone would be enough to change the field of economics: “simply accumulating more demonstrations of anomalies or of the unrealistic character of foundational assumptions seems unlikely to have a serious impact on mainstream economics.”Footnote8 Rather, efforts to change decision and consumer theory became an important aspect of the emerging BE core (Thaler Citation1980).

4.3. Emerging new directions

Another important transformation in the 1980s network is the emergence of new clusters around the historical core. In the 1980s network, we observe multiple minor clusters emerging on the margins of the historical core, including clusters focussed on intertemporal choice, experimental market economics and proto-social preferences, and behavioural finance (). Most of the articles in this part of the network are situated in economics or management (i.e., finance).

One important new dimension that emerged during this time period was research focussed on intertemporal choice. In the 1980s, behavioural economists such as Thaler and George Loewenstein investigated the question of dynamic inconsistencies through a psychological lens. One important goal for them was to explain why supposedly rationale people impose rules on themselves when they anticipate a self-control problem. This question was empirical in nature, but behavioural economists rapidly developed alternative theories to address it (). The most important articles of this time period were Thaler (Citation1981), which explored empirical anomalies in relation to time, and Thaler and Shefrin (Citation1981) and Loewenstein (Citation1987), which explored alternative theories integrating the concepts of self-control and ego-depletion in economics. As with the theme of risk and uncertainty, behavioural economists also extensively cited earlier work related to intertemporal choice to emphasise that BE’s anomalies were not new: among older references, we find Strotz (Citation1955), which made an early attempt to address intertemporal inconsistencies in economics, as well as multiple references to Ainslie (Citation1975), which provided psychological foundations for the topic.

Figure 5. Zoom in on the margins of the core (colour-coded by discipline). Grey nodes are “other” disciplines.

Figure 6. Co-citations of articles published between 1990 and 1999 (node size = citations by the corpus, colour-coded by clusters, τ = 3, network generated from the references of 303 articles). Grey nodes are smaller-clusters.

Another important cluster of the 1980s is experimental market economics and proto-social preferences. This mixed unstable cluster will split into multiple separate clusters in the next decade (Appendix 9.2). This shows that unlike intertemporal choice, social preferences did not emerge as a clear new research direction in the 1980s. Rather, the experimental market economics and proto-social preferences cluster consists of a mix of experimental articles involving interactive games, which we regroup into two dimensions.

The first dimension of this cluster is focussed on experimental markets, with many articles by Vernon Smith. In the words of Starmer, there are “disagreements between folks who view themselves as experimental economists and others who identify themselves as behavioral economists. I see apparent lines of fracture between different camps using experimental methods.”(Maas and Svorenčík Citation2016, 177). Smith was a member of the Sloan-Sage Foundations in the early years of the program. However, his particular approach stemmed from a different psychological tradition than Kahneman and Tversky (Svorenčík Citation2016), and he left the program because of the resulting epistemological and methodological differences (Heukelom Citation2014, 162). While most behavioural economists were interested in how individual deviates from standard models, the experimental market economics tradition of Vernon Smith focussed on how market mechanisms led to equilibrium. This led to important differences in experimental methods, theoretical results, and policy recommandations (Heukelom Citation2014, 162). The particular position of Smith within BE is reflected in the network. He is not highly co-cited in our corpus, and most of his articles are co-cited together, in relative isolation from the rest. In other words, it is clear that by the 1980s, the BE community considered Smith’s approach to be distinct from the rest of BE.

A second dimension of this cluster is focussed on what we call “proto-social preferences.” The articles on proto-social preferences are identified as part of the same cluster as Smith’s experimental economics research because they are also concerned with game theory and experiments involving interactions (e.g., bargaining games, market games). However, unlike the articles by Smith, these articles are more critical of economics. We find here works by Güth, Schmittberger, and Schwarze (Citation1982) and Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler (Citation1986), which would go on to provide the foundations for more research on fairness in the 1990s. The former showed that people in the ultimatum game — one of the central experiments on social preferences — do not behave selfishly. The latter showed that people sometime favour fairness norms in market settings.

We also find in this cluster some of the game theorists concerned with this particular theme, such as Rubinstein (Citation1982) and Binmore, Shaked, and Sutton (Citation1985), who both became critical of BE afterwards. Along with Avener Shaked, Ken Binmore would become one of the most vocal critics of BE (Binmore Citation1999; Binmore and Shaked Citation2010a), deeming the social preferences approach to be unscientific (Binmore and Shaked Citation2010b). Overall, this cluster groups together many heterogeneous articles, which for the most part, would go on to become relatively unimportant in BE. However, some of these articles, such as Güth, Schmittberger, and Schwarze (Citation1982), laid out the foundations for one of the most stable and important clusters of the 2000s, with their concern for social preferences.

Finally, further from the core, we find the cluster of behavioural finance emerging, with foundational articles such as Shiller (Citation1981) and De Bondt and Thaler (Citation1985). Early on, behavioural finance emerged as a relatively independent — and separate — new research direction. The articles in this cluster are the most inward-looking of all clusters in the 1980s, and across all four time periods, behavioural finance remains the most inward-looking cluster of all (). Moreover, most articles in the behavioural finance cluster never change clusters across decades, indicating that articles in this cluster are well identified and that the frontiers between this cluster and the rest of BE are not porous (Appendix 9.2). However, we do find a small group of articles that have stronger relations to the historic core of BE, with a focus on applying prospect and self-control theories to explain financial market anomalies (Shefrin and Statman Citation1984). Another interesting characteristics of the behavioural finance cluster is that its critical nature structures the network. As key voices in the “rational-behavioural debate in financial economics” (Brav, Heaton, and Rosenberg Citation2004), financial economists such as Eugene Fama occupy a central role in this cluster, with some of the most cited articles in the decade. This contrasts with the rest of the behavioural economists, who favour citing critical articles such Allais (Citation1953), rather than the theoretical contributions they target.

Overall, BE was heavily structured in the 1980s by Kahneman and Tversky’s work in economics and psychology. They remained important in the psychology literature, while also gaining increasing importance in economics. In economics, Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) provided the theoretical foundation for BE’s historic core. BE became a program oriented towards identifying experimental anomalies, while also proposing alternative models in economics based upon psychological concepts such as framing (Kahneman and Tversky Citation1979) and regret (Loomes and Sugden Citation1982). In addition to shaping BE’s historic core, Kahneman and Tversky’s move towards economics also promoted a variety of new approaches in BE, as reflected in the emerging clusters of intertemporal choice, experimental economics, (proto-)social preferences, and behavioural finance.

5. The 1990s: an established program

5.1. The end of the Sloan-Sage program

In 1992, the Sloan-Sage Foundations BE program came to an end. It was also around that time that the field became increasingly popular (Geiger Citation2017). As it spread in economics, BE became less of a centralised research program comprised of a handful of personalities.

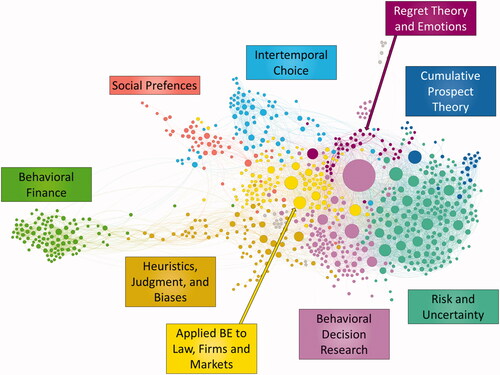

Our analysis of the 1990s co-citation network illustrates the following important changes that occurred during that decade ():

The influence of Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) became consolidated, as multiple new clusters emerged around prospect theory.

Behavioural finance, social preferences, and intertemporal choice emerged more clearly as new research directions, with concerns more distinct from the psychological origins of Kahneman and Tversky.

Experimental market economics articles become less significant in the literature, confirming the separateness of experimental market economics from BE.

Law emerged as a new distinct discipline in the literature, as new prospects for the application of BE gained relevance.

5.2. The consolidation of prospect theory and Kahnemman and Tversky

The first important transformation of the network is the consolidation of Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) as one of the most important articles in the network. The number of citations to Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) in the original corpus tripled from 54 to 150, from the 1980s to the 1990s. In the 1980s, Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) was cited 1.6 times more often than the second most cited article of that decade (Grether and Plott Citation1979). By the 1990s, this ratio increased to 2.7. In the 1990s, the three most cited articles in the network were all authored by Kahneman and Tversky (Kahneman and Tversky Citation1979; Tversky and Kahneman Citation1981, Citation1992). Moreover, even as we observe new clusters emerging, most of these clusters have a relatively low-weighted inwardness, which suggests that are part of a more global research program ().

Table 3. Weighted share of inward links by cluster in the 1990s network.

We find a variety of new clusters that appear in the 1990s around Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979), all of which have a strong historical relation to the program. The risk and uncertainty cluster is similar to the same-named clusters from the previous decades’ networks. All of the most cited articles in this cluster are also similar to those cited in the 1970s. We find classics such as Allais (Citation1953), Ellsberg (Citation1961), and a variety of articles by Tversky, Slovic, and Lichtenstein. We also find some of the theoretical articles published in the 1980s, which became more cited during the 1990s, including: Loomes and Sugden (Citation1982) and Bell (Citation1982), with their focus on regret theory; Quiggin (Citation1982), with its integration of rank dependent utility; and Yaari (Citation1987), with the dual theory of choice.

We also find the emergence of cumulative prospect theory as a cluster that is directly related to risk and uncertainty. Tversky and Kahneman (Citation1992) cumulative prospect theory is a development of traditional prospect theory that incorporates, among others things, insights from Quiggin (Citation1982)’s rank dependent utility. One improvement that cumulative prospect theory offers over traditional prospect theory is that decision makers never choose first-order stochastically dominated options. However, this comes at the expense of some of the psychological richness of traditional prospect theory, as some cognitive processes, such as the editing phase of prospect theory, are no longer modelled.

Another directly related cluster that emerges in the 1990s is regret theory and emotions. This cluster is mostly composed of articles in psychology. We find here most of the articles by Loomes and Sugden on their regret theory, as well as articles in consumer research and psychology on similar questions (Simonson Citation1992). We also find a variety of articles that are more generally concerned with how emotions and cognitive processes impact decisions (Larrick Citation1993).

From a disciplinary point of view, one notable trait of the 1990s network is the rise of law as a distinct cluster that forms around the work of Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler (Citation1990) on Coase theorem and the endowment effect (). This cluster is concerned with the effect of biases in relation to contracts, negotiations, firms, and transaction costs. For example, the endowment effect prevents effective allocations as predicated by Coase theorem because individuals disproportionately value property rights that they already possess compared with those they could exchange. Therefore, the initial allocation of property rights matters: initial ineffective allocations may be maintained simply because individuals become unwilling to exchange something they already own. We also find more general articles on what a “capable” individual is in accordance with the law, given the biases highlighted by behavioural economists. More generally, this cluster also hosts applied articles to management like Thaler (Citation1985), Thaler’s first article about mental accounting and published in Marketing Science.

Figure 7. Co-citations of articles published between 1990 and 1999 (node size = citations by the corpus, colour-coded by disciplines, τ = 3, network generated from the references of 303 articles). Grey nodes are “other” disciplines.

Finally, another cluster that relies heavily on Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) emerges: behavioural decision research. This cluster is particularly interesting, since between 1990 and 1999, Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) is situated here rather than in the risk and uncertainty cluster. This cluster is also dominated by articles published in psychology, with 50% of the cluster’s articles published in psychology, 36% in management, and 12% in economics. Besides articles by Kahneman and Tversky, we find among the most cited articles in this cluster Payne, Bettman, and Johnson (Citation1992) and Simonson (Citation1989). Payne, Bettman, and Johnson (Citation1992) describes behavioural decision research as the direct legacy of Edwards and Herbert Simon’s research:

Almost 40 years ago, Edwards (Citation1954) provided the first major review for psychologists of research on decision behaviour done by economists, statisticians, and philosophers. He argued that work by economists and others on both normative and predictive decision models should be important to psychologists interested in judgement and choice. About the same time, Herbert Simon (Citation1955) argued that if economists were interested in understanding actual decision behaviour, then research would need to focus on the perceptual, cognitive, and learning factors […] Nearly four decades later, a clear and separate area of inquiry has emerged, which we refer to as Behavioural Decision Research (BDR). This area is intensely interdisciplinary, employing concepts and models from economics, social and cognitive psychology, statistics, and other fields. It is also nearly unique among subdisciplines in psychology, because it often proceeds by testing the descriptive adequacy of normative theories of judgement and choice (Payne, Bettman, and Johnson Citation1992, 88).

This cluster may be interpreted as comprising the more experimental side of BE, with articles concerned with testing and applying BE to psychology, marketing, and consumer research, with a strong interest in consumer decision processes. Unlike most “new” behavioural economists (Sent Citation2004), these psychologists also tends to be more prone to cite Simon’s work. However, this cluster will not survive the next decade and most citations remain limited to seminal papers.

5.3. New stable clusters

New research directions that emerged in the 1980s evolved to form distinct clusters in the 1990s that would last for the next 30 years: behavioural finance, intertemporal choice, and social preferences. In these clusters, we find some of the latter articles by BE’s founders, Kahneman, Tversky, and Thaler, but we also find new personalities emerging. These clusters are also the three most inward-looking, signalling that these new research directions had not yet become independent by the 1990s, although they would become more so over time (). This is particularly true for behavioural finance, the most insular cluster.

By the 1990s, the behavioural finance cluster had grown in size and formed a distinct — and important — community in BE. De Bondt and Thaler (Citation1985) became the most cited and co-cited article of this cluster. We also find new important articles emerging, with Jegadeesh and Titman (Citation1993) on momentum effect in second place and De Long et al. (Citation1990) on investor sentiment in third place. Articles by Fama and Sharpe still occupy an important position in this cluster, with the fifth, sixth, and seventh most cited articles. In other words, in the 1990s, the behavioural finance cluster is still very much centred by the critical approach of the efficient market hypothesis and modern financial theory.

The intertemporal choice cluster, which relies heavily on the work of Thaler (Citation1980) and Thaler (Citation1981) in the 1980s, includes a more diverse set of articles in the 1990s. We find here the emerging work of Akerlof (Citation1991), Loewenstein and Prelec (Citation1992), and Laibson (Citation1997). Ainslie (Citation1975) remains the most cited article of the cluster across the network, thus confirming the foundational role of Ainslie’s work.

Finally, social preferences emerges as a distinct cluster, clearly focussed on fairness and pro-social behaviour, rather than the more heterogeneous cluster focussed on interaction in the 1980s. In the 1990s, Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler (Citation1986) on fairness in the market remains the most cited article of this cluster. This article comprised an important first step towards the integration of fairness in BE. It showed that in some situations, a concern for fairness could prevent market equilibrium. This question of market equilibrium remained important throughout the 1990s, as new important empirical articles emerged. Fehr, Kirchsteiger, and Riedl (Citation1993) tested the impact of fairness on market mechanisms in the laboratory. Roth et al. (Citation1991) investigated the heterogeneity of market and bargaining behaviour, by implementing experiments in a variety of cities across the globe. At the same time, researchers in the social preferences literature were also querying the empirical validity of game theory. Most notably, Güth, Schmittberger, and Schwarze (Citation1982), emerged as the foundational article testing the ultimatum game in the laboratory and the most cited article in this cluster. The anomalies resulting from these experiments steered behavioural economists towards finding an alternative theory of pro-social behaviour. One of the first successful attempts was made by Rabin (Citation1993), who incorporated fairness in game theory. This publication became the third most cited article in the cluster by the 1990s. This new research direction was also helped by the column of Camerer and Thaler (Citation1995), who compiled anomalies in relation to prosocial behaviour and who singled-out Rabin (Citation1993) as making one of the most serious attempts to incorporate psychology into game theory.

One emerging pattern that we find in BE is that as new research dimensions emerge, they stabilise around central theoretical — and mathematical — contributions. Theoretical contributions become the most cited articles of stable clusters over time, and clusters with central theoretical contributions tend to become more stable and more inward-looking (Appendix 9.2 and ). This tends to confirm Rabin’s view: BE is structured by the integration of psychological insight into theoretical mathematical frameworks inspired by economics (Rabin Citation1998, Citation2002, Citation2013). It is through theoretical contributions that stable subspecialties emerged in BE.

Early behavioural economists and experimentalists put a lot of efforts on theoretical contributions for two reasons. First, they knew that to successfully influence economics they needed to accumulate traditional scientific capital, a common pattern observed by sociologists of science with emerging fields (Bontems and Gingras Citation2007). For example, Charles Plott, like Rabin (Earl and Peng Citation2012), explicitly adopted a Trojan Horse strategy and encouraged experimentalists to appear “traditional”: “‘Don’t sell yourself as an experimental economist. There are no jobs for experimental economists. There are jobs for traditional people.’” (Maas and Svorenčík Citation2016, 40). As explicitly expressed by Kahneman, economists suffer from “theory-induced blindness” (Kahneman Citation2011, 2087). The main way to accumulate traditional scientific capital in economics is not to discover new empirical anomalies, but to show proficiency in theoretical modelling.

Second, when behavioural economics and behavioural finance emerged with many anomalies and a variety of psychological explanations for them, economists explicitly called-out economists for lacking a “blueprint for change”(Kleidon Citation1986). Even before that, as we have showed from discussions within the Sloan-Sage Foundations, behavioural economists knew that experiments would not be enough to impact mainstream economics, and that alternative models would be necessary (Section 4.2). If behavioural economists wanted to change economics, they would need a model to explain anomalies, otherwise neoclassical theory would remain the better alternative.

The strategy adopted by behavioural economists worked. The specialty became important in economics, and theoretical successes became central to the structure of the field. Paradoxically, these models would latter become the centre of many critics of the program. For Berg and Gigerenzer (Citation2010) behavioural economics’ models are too similar to neoclassical economics to be distinguishable from it. For Spiegler (Citation2019), behavioural economics is mostly “atheoretical” because its models are simple distortion of familiar functions rather than new theoretical foundations for economics.

Overall, behavioural economics is probably less mathematical than traditional economics (Braesemann Citation2019, 5), and behavioural did contribute to the shift away from theory towards more empirical work (Angrist et al. Citation2020). However, theoretical contributions throughout the history of the field remained an important driving force that both structured the field and contributed to its success.

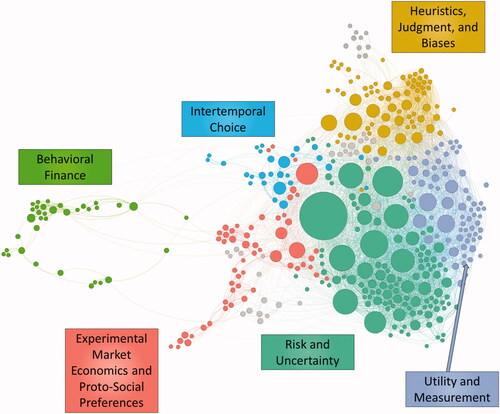

6. The 2000s: beyond Kahneman and Tversky

6.1. First Nobel Prize

The 2000s mark an important milestone for BE. In 2002, Kahneman received the Nobel Prize in economics for “having integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgement and decision-making under uncertainty”.Footnote9 It is also during this decade that some critical economists would take an explicit stand against BE (Binmore Citation1999; Gul and Pesendorfer Citation2008).

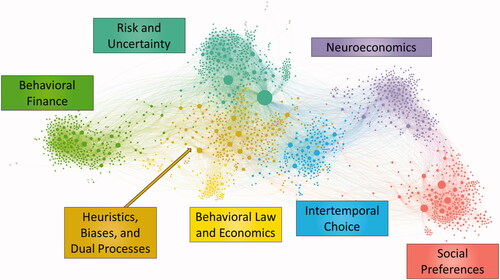

In our analysis of the 2000s co-citation network, we find evidence of five structural transformations that occurred during this period:

The centrality of Kahneman and Tversky in BE decreased, along with psychology more generally.

The heuristics, judgement, and biases literature became less centred around older articles from Kahneman and Tversky, in favour of newer economics articles.

The intertemporal choice, social preferences, and behavioural finance literatures became more distinctly separate from the historical core of BE, with social preferences and behavioural finance being more autonomous clusters.

Neuroeconomics rapidly emerged as an important new research direction, comprised mostly of articles published outside of economics.

Behavioural approaches to law and economics became more autonomous, forming a distinct cluster comprised almost entirely of law articles.

6.2. The decreasing relative importance of Kahneman and Tversky and psychology

The 2000s marked the beginning of the decreasing centrality of Kahneman and Tversky in BE. First, while the number of citations for Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) triples in the 2000s, Fehr and Schmidt (Citation1999) becomes the third most cited article in the network and the most cited article excluding works by Kahneman and Tversky. Moreover, Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) is only cited twice as often as Fehr and Schmidt (Citation1999) in the 2000s, thus marking the diminished dominance of Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) compared with the 1990s. Second, more than 50% of the 1980s and 1990s networks were composed of clusters dominated by Kahneman and Tversky (e.g., risk and uncertainty; heuristics, judgement, and biases). By the 2000s, these clusters comprise only 35% of the network. Thirdly, most secondary clusters in the 1980s and 1990s included an article by Kahneman and Tversky among their most cited. By the 2000s, the centrality of older articles by Kahneman and Tversky — and to some extent Thaler — had shifted in favour of articles emerging in the 1990s, by new personalities such as David Laibson, George Loewenstein, Ernst Fehr, Gary Bolton, Terrance Odean, and Jack Hirshleifer. Overall, BE developed new directions that were increasingly independent from the historical origins of the program. Finally, by the 2000s and 2010s, emerging subspecialties of the previous decades had become more independent from the rest of the network, transforming BE into a collection of subspecialties rather than a relatively unified program ().

With Kahneman’s Nobel Prize and the recognition of BE as a legitimate new approach, the field developed very rapidly in the 2000s (Geiger Citation2017). BE authors had already identified important topics of study, with the three dimensions of bounded rationality already established (risk and uncertainty, intertemporal choice, and social preferences), behavioural finance emerging as a distinct cluster, and strong interest forming for behavioural law and economics in the 1990s. In the 2000s, these dimensions expanded as distinct suspecialties with their own foundations, particularly in the case of the social preferences and behavioural finance clusters, which had drifted away from the historical core.

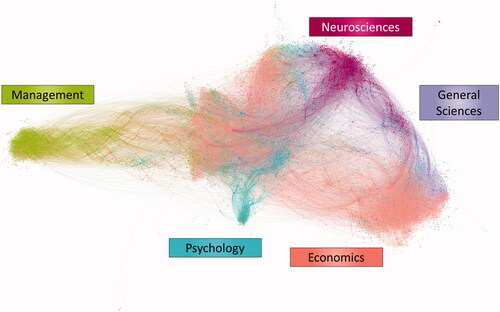

The decreasing importance of Kahneman and Tversky is also reflected in the more general decline of psychology in the 2000s network ().Footnote10 In the 1980s and 1990s networks, around 29% of the articles were published in psychology. This proportion fell to 20% in the 2000s. This transformation is particularly visible in the heuristics, judgement, and biases cluster, at the historical core of BE. In the 1980s and 1990s networks, this cluster was dominated by foundational articles by Kahneman and Tversky, published in the 1970s in psychology. During those two decades, 73–76% of the articles in this cluster were published in psychology. In the 2000s network, psychology remains the dominant discipline in this cluster, but the proportion of articles published in psychology in only 44%. With the exception of Tversky and Kahneman (Citation1974), Kahneman and Tversky’s older articles are cited less often in the 2000s networks compard with previous decades, in favour of more recent articles published in economics. In the 2000s, we find a variety of topics that have in common biases from experiments in economics, dual-processes approaches, and the impact of emotions on decision making. This literature includes multiple post-1980s papers by Kahneman and Tversky related to biases (e.g., framing, endowment), some of the more recent articles by Kahneman related to dual processes (Kahneman Citation2003a,b), and more general articles about economics and psychology by other personalities in the field (Thaler Citation1980; Rabin Citation1998; Loewenstein et al. Citation2001). As BE developed, it thus became less reliant on the historical psychological core of the 1970s, in favour of more recent articles on the same questions in economics.

Table 4. Share of psychology in the network per decade.

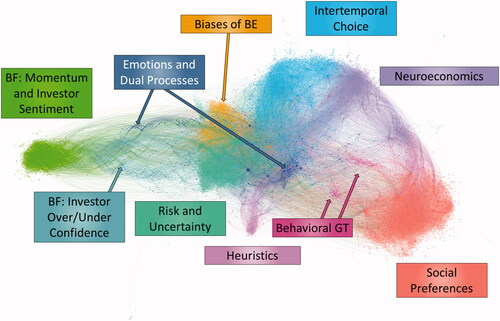

6.3. Specialising autonomous clusters

The 2000s mark a period of time when what is often identified as contemporary BE really emerged. In the 1990s, the three bound of rationality were still emerging and much of BE was still structured by Kahneman and Tversky (Citation1979) as the central and most important theoretical contribution of the field. During the 2000s, the three bounds of rationality came to be of roughly equal importance, all with their own central theoretical contributions that emerged as distinctively more cited by other papers in the same cluster, thus making the cluster more autonomous from the historical core.

We find a similar trajectory among the three bounds of rationality. When these clusters first emerged, the most cited articles tended to be experimental anomalies, pointing out the flaws of standard economics theory. After a decade, a handful of theoretical articles came to capture most of the co-citations, as these clusters organised themselves around a handful of theoretical contributions. In the social preferences cluster, we find three theoretical contributions among the three most cited articles: Fehr and Schmidt (Citation1999), Rabin (Citation1993), and Bolton and Ockenfels (Citation2000). While Rabin (Citation1993) modelled how individual behaviour depends on one’s perceptions of the intentions of others, Fehr and Schmidt (Citation1999) and Bolton and Ockenfels (Citation2000) modelled pro-social behaviour as preferences with inequity aversion. In the intertemporal choice cluster, we find a similar situation, with three theoretical contributions as the most cited: Laibson (Citation1997) on the incorporation of hyperbolic discounting, Loewenstein (Citation1996) on the integration of emotions and “visceral” factors on decision making (mostly applied to intertemporal choices), and O'Donoghue and Rabin (Citation1999) on the inclusion of self-control and time-inconsistent preferences in economic theory.

This trend tends to make these clusters more self-sufficient over time, as they come to rely more on their own literature rather than on the network as a whole. Looking at the weighted share of inward links by cluster, we find that all three bounds of rationality become more inward-looking overtime (). This also confirms what we can observe visually (): In the 2000s, the social preferences and behavioural finance clusters are the most inward-looking and autonomous clusters of the network. However, while the behavioural finance cluster became autonomous almost immediately upon its emergence in the 1980s, this autonomy was built over time for social preferences, intertemporal choice, and risk and uncertainty.

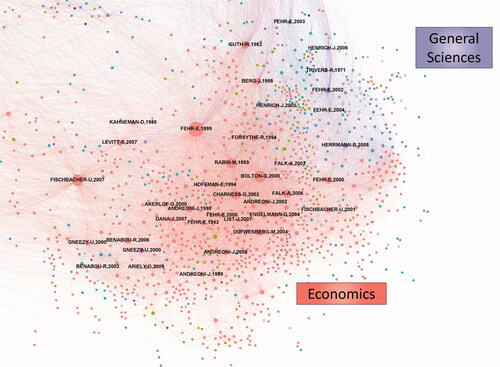

Figure 8. Co-citations of articles published between 2000 and 2009 (node size = citations by the corpus, colour-coded by clusters, τ = 5, network generated from the references of 1414 articles). Grey nodes are smaller-clusters.

Figure 9. Co-citations of articles published between 2000 and 2009 (node size = citations by the corpus, colour-coded by disciplines, τ = 5, network generated from the references of 1414 articles). Grey nodes are “other” disciplines.

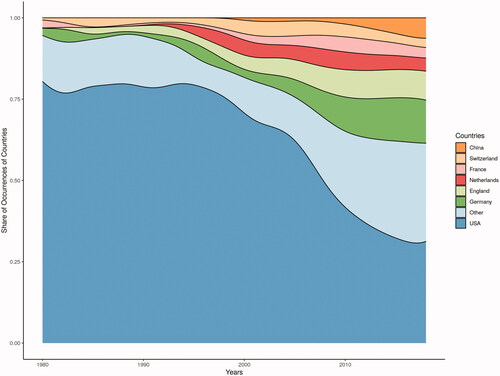

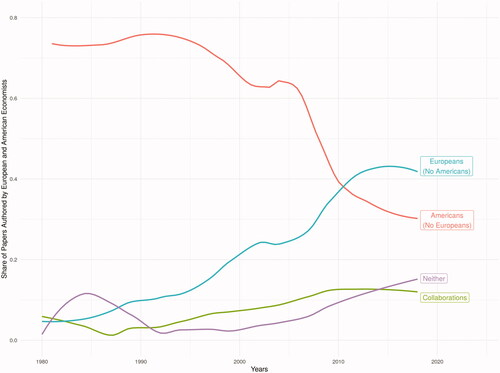

Figure 10. Share of papers authored by European and American Economists. We classified papers into four categories: (1) papers by authors with European and others affiliations with no Americans affiliations, (2) papers by authors with American and others affiliations with no European affiliations, (3) Authors with neither Europeans nor Americans affiliations and (4) papers of authors were at least one affiliations is American and one European.

Figure 11. Co-citations of articles published between 2010 and 2018 (node size = citations by the corpus, colour-coded by clusters τ = 5, network generated from the references of 3 517 articles). Grey nodes are smaller-clusters.

The only cluster that becomes more outward-looking in the 2000s is the heuristics, judgement, and biases cluster. This reflects the particular — and central — role of this cluster. It is not a cluster with a well-identified central contribution, but is rather comprised of an association of articles on multiple biases and experiments that are at the foundation of BE. In that sense, it serves as a “resource-cluster” for the rest of the network, providing the foundations necessary for new subspecialties to emerge. This also makes for less consistent intertemporal stability of references, as this cluster is positioned at the frontiers of all other clusters (Appendix 9.2).

Besides clusters becoming more autonomous in the 2000s, we also find important transformations in the behavioural finance cluster regarding its central references. The two most cited articles in this cluster in the 1990s, De Bondt and Thaler (Citation1985) and Jegadeesh and Titman (Citation1993), lose their central importance by the 2000s. Instead, we find among the top three cited articles from the late 1990s a variety of new central personalities, related to investor psychology, overconfidence, and over/under-reactions (Daniel, Hirshleifer, and Subrahmanyam Citation1998; Odean Citation1998; Barberis, Shleifer, and Vishny Citation1998). The emergence of these new personalities also coincide with Fama becoming less important in the network, with only Fama and French (Citation1993) positioned among the top ten most cited articles in the 2000s. In 2019, Fama stated provocatively: “I’m probably the most important behavioural-finance person, because without me and the efficient-markets model, there is no behavioural finance.”Footnote11 This may have been true in the 1990s, when behavioural finance was heavily structured by its critical dimension; however, by the 2000s and 2010s, behavioural finance had become less focussed on criticising traditional finance theory.

The cluster of BE applied to law is also more distinctive in the 2000s. In the 1990s, it consisted of a mix of BE articles, mostly focussed on the endowment effect, and law articles. By the 2000s, 58% of the articles in this cluster are in law (compared with 23% previously), with Jolls, Sunstein, and Thaler (Citation1998) as the most cited and unifying article. We find a variety of concepts represented in this cluster. As in the in 1990s, we find a concern for how different biases may impact legislation and market transactions. However, unlike the previous decade’s network, we also find a strong interest in hindsight bias (individuals thinking they would have successfully predicted a past event) rather than the endowment effect. We also find an emerging interest in the questions of paternalism and nudges.

Finally, neuroeconomics represents an important new emerging cluster in the 2000s. This community emerges very rapidly: although it was completely absent from the 1990s network, it is the fourth biggest cluster in the 2000s network. This cluster is composed almost entirely of articles published outside of economics. We find that 95% of the articles are published in a cognitive sciences journal or a general sciences journal (e.g., Nature, Science). The most cited article in economics, Camerer, Loewenstein, and Prelec (Citation2005), is the tenth most cited article in the cluster overall. From this point of view, the neuroeconomics cluster may be understood to follow a similar trajectory as the 1970s network, dominated as it is by non-economics articles. However, one main difference is that in the 1970s, the BE network included past seminal economics papers, which were extensively cited (Allais Citation1953; Ellsberg Citation1961). In the case of the neuroeconomics cluster, we find almost no economics articles cited, and the few economics articles that are cited focus on how neurosciences may inform BE. The articles from this cluster are sometime co-cited across the network with articles from other clusters, but most of the time, neuroeconomics is concerned with neuroeconomics, with a weighted share of inward links of 0.84.

7. The 2010s: the confirmation of a multipolar world

7.1. Second Nobel Prize and the rise of Europeans

The 2010s also marked an important milestone for BE, as Richard Thaler, the third founder of the program, won the Nobel Prize in 2017. The 2010s saw the continued transition of the field that was already underway in the 2000s (). BE is no longer just about Kahneman and Tversky. Rather, it has come to comprise a combination of subspecialties, which have some degree of autonomy from the historical core. This is confirmed by the fact that the BE network has gotten sparser over time, even as the threshold values are kept constant (). It is expected that co-citation network become sparser as the number of article increases or the co-citation threshold increases, however, combined with increasing inwardness (), we do find that the decreasing density is not randomly distributed across the network. More importantly, in the 2010s, clusters that have historically been dominated by Kahneman and Tversky are no longer the largest. Rather, the social preferences cluster is the largest during this decade, followed by intertemporal choice (or behavioural finance if we combine the two new sub-clusters titled BF) ().

Figure 12. Co-citations of articles published between 2010 and 2018 (node size = citations by the corpus, colour-coded by disciplines, τ = 5, network generated from the references of 3517 articles). Grey nodes are “other” disciplines.

Figure 13. Zoom in on the social preferences cluster (colour-coded by discipline). Grey nodes are “other” disciplines.

Table 5. Density of networks per decade.

This rise of the social preferences cluster may also be associated with another transformation in the field, related to the decreasing uni-polarity of the network. One leading figure of BE in the 2010s, Ernst Fehr, is not American. Rather, he is an Austrian-Swiss economist. The decreasing importance of Kahneman and Tversky is accompanied by the decreasing importance of American authors more generally in BE. From the 2000s onwards, the field has become more diverse in the nationalities of its contributors. In the 1980s and early 1990s, around 75% of BE articles were authored by American economists without European (). This proportion decreased to 60% in the mid-2000s, and to 30% by the end of the 2010s. While American and European economists increased their collaborations in BE papers from close to 0% in the 1980s to around 12% in the 2010s, most of the increasing importance of European economists is explained by papers authored by European economists without American. The increasing importance of European is leads to an increasing occurrence of national affiliations to German, English, Dutch, French, and Swiss institutions (Appendix 9.3). By the very end of the 2010s, we also observe a sharp rise of Chinese economists with Germany, England, and China as the most occurring national affiliations in BE, after the United States (Appendix 9.3 for more detailed on occurring national affiliations).