Abstract

Since 2015 it has become clear that various manuscripts that once belonged to the Turgot family archive are missing. This paper reports on the recent recovery in Japan of photographs of some of these manuscripts and presents a case study of the images of the famous draft known as Valeurs et monnaies. It allows one to appreciate the practices of previous editors of Turgot’s writings as well as the writing process of the author.

1. Introduction

From the early 1970s the study of the original writings of Anne Robert Jacques Turgot (1727–1781) was for many years hampered by the inaccessibility of the single largest collection of manuscripts of this prominent Enlightenment thinker, economic theorist and statesman of the Ancien Régime. The eventual sale in 2015 of the archive of the Turgot family, kept since the 19th century at the castle of Lantheuil in Normandy, raised hopes that a study of these papers would again be possible. Amongst them were known to be many of the source texts used by the principal editors of Turgot’s works, that is, Pierre Samuel Du Pont (1739–1817) in the early 19th century and Gustave Schelle (1845–1927) in the early 20th century. In turn, virtually the whole subsequent secondary literature about Turgot has, directly or indirectly, relied on these two classic editions of Turgot’s Œuvres.Footnote1 Since 2015, with their transfer to the Archives Nationales, several of these sources have indeed become accessible.Footnote2 Among them are famous pieces, for instance, Turgot’s drafts of the Éloge de Gournay (1759), his reports on the prize essays of Saint Peravy and Graslin (1767) and copies of three of the “Letters on the Grain Trade” (1770).Footnote3

Unfortunately, however, about two dozen other documents, which previous editors had indicated as also being part of the Archives de Lantheuil, and among which are some of Turgot’s most significant contributions, are not among the papers that now make up the Fonds Turgot.Footnote4 The reasons for this discrepancy are not fully understood and, more importantly, the originals of the missing pieces remain elusive. Fortunately, however, photographs of several pieces were recently found in Japan, in the library of the late professor Takumi Tsuda after his death in February 2021. This paper discusses some of the digital reproductions that were made of those photographs.Footnote5 They provide access to the originals of several of Turgot’s writings, including drafts and notes for his discours aux sorboniques (1750), the draft known as Valeurs et monnaies (normally, but incorrectly, dated to 1769), and his memoir on taxation for Benjamin Franklin (1778). The general aim of this paper is to provide a case study of the long-term consequences of editorial decisions for the reception of economic ideas. Section 2 provides a brief historical overview of the publication history of Turgot’s writings. Section 3 looks at one of the recovered pieces and presents new, but preliminary, insights that an original manuscript affords. Section 4 draws conclusions.

2. A (very) brief publication history

The ways in which the post-humous reputation of “great authors” is shaped by adoring biographers and editors is not always sufficiently appreciated. In Turgot’s case, the turbulent decade after his death and, considerably later, the publication of the first edition of his collected works during the comparative calm of the Empire, were in a sense decisive.

One important reason why during his own lifetime Turgot’s reputation as an author was far from settled is that, due to a combination of scholarly perfectionism and the discretion demanded from high government officials, he had allowed only few of his writings to be published. Moreover, those works that did appear in print, including his five contributions to the Encyclopédie and the Réflexions sur la formation et la distribution des richesses, were published anonymously.Footnote6 This reticence did, of course, not prevent him from establishing a certain reputation as a man of letters even from a relatively early age. The men and women of the prominent intellectual circles in which he moved certainly knew about his authorship of some anonymous works. In addition, the survival of neat manuscript copies testifies to a more restricted circulation of some other writings already during his lifetime.Footnote7 Nevertheless, this only established his reputation as an author amongst a more select audience. The wider public knew him in the first place as a briefly successful and then disgraced minister, who had been painted by his detractors as an inflexible “man of system”. However, what precisely this philosophical “system” had consisted of was not easy to know so long as no single account of his ideas was available, or a wider selection of his writings was published.

These were the tasks to which two of his friends and collaborators, Du Pont and Condorcet, set themselves after Turgot’s death. Du Pont, who acted as the latter’s literary executor,Footnote8 published Mémoires sur la vie et les ouvrages de M. Turgot the year after his friend’s death.Footnote9 This work was not only meant as a vindication of Turgot’s actions during his tenure as minister of finance, which had invariably been motivated by a perfect devotion to le bien public. It also established an enduring image of the great man’s almost saintly personal qualities of modesty, simplicity, sincerity, and steadfastness and of an author with wide-ranging intellectual interests. The latter aspect was further magnified in Condorcet’s Vie de M. Turgot of Citation1786, which “endeavoured to make M. Turgot known to the world as a philosopher, rather than as a minister” (Condorcet Citation1787, ix–x). Indeed, Condorcet portrayed Turgot’s opinions as forming a comprehensive and consistent “system”, one that emphasised the perfectibility of which humans, society and the political and legal orders were ultimately capable. In comparison, Du Pont’s biographical sketch was more factual and, important in the present context, it provided a detailed chronological account of Turgot’s varied writings, many of which had remained unseen. To repair this defect, Du Pont promised a publication of a collected works (Du Pont Citation1782, ii). It was, however, a promise that would not be fulfilled for over a quarter of a century.

Instead, in the decade after Turgot’s death some of his further writings did start to appear in print, but in a haphazard fashion. Two of his English correspondents, Josiah Tucker in 1782Footnote10 and Richard Price in 1785,Footnote11 included in their publications transcripts of letters they had received from the late Frenchman. In addition, in subsequent years (re)publications appeared of several official mémoires and letters that Turgot had written in his capacity of intendant. These included, in 1788 a first print edition of three of the letters on the grain trade to Turgot’s one-time superior Terray;Footnote12 republications in 1789 of Mémoires on the “Marque des Fers” and “sur l’usure”;Footnote13 in 1790 of the Mémoire […]des Carrières et des Mines,Footnote14 and in 1798 of the Mémoire […] sur la surcharge des impositions.Footnote15 Other publications were the Mémoire sur les administrations provinciales, which appeared in a number of forms in 1787 and 1788,Footnote16 and a Mémoire about the independence struggle of the United States in 1791.Footnote17 In addition to these contributions originally written by Turgot in an official capacity, a corrected edition of the Réflexions was published in 1788Footnote18 and two editions of an early work, Le Conciliateur appeared 1788 and 1791 respectively.Footnote19 All these prints were not a single orchestrated effort to publish Turgot writings. They were initiated by various persons,Footnote20 and all they had in common was that they were attempts to wield the authority of a reformist statesman of the old regime in various debates that took place within the significantly altered political context of the early Revolution.Footnote21 The only arguable exception to this, the 1788 edition of the rather theorical Réflexions, had a more direct impact in Britain where it was translated and published several times.Footnote22

Despite all these publications of different pieces of Turgot’s writings, it is unlikely that they allowed contemporary readers to form a good impression of his overall economic and political philosophy and of the breath of his writings. Some apt commentary on this point was provided in the foreword of the English translation of the Réflexions of 1793. The importance of Turgot was not yet fully understood, it was asserted. He had indeed been “one of the first political characters which the present century has produced”, not only as a statesman, but also as an author. The principal reason, however, why Turgot had not yet reached the high “degree of celebrity” he deserved was that “his writings, being in detached pieces, are little known beyond the limits of his own country; [and] not even there have his countrymen paid the tribute due to his excellent productions, by collecting and publishing them together” (1793, i).

This may have been an implicit admonition of Du Pont whose promise of a collected works was by then already more than a decade old. In the event it was another 15 years before he would keep it, a long delay that was mostly due to the political upheavals in France and the ever-busy personal life of the editor on both sides of the Atlantic.

When the nine volumes of his Œuvres de M. Turgot eventually started to appear in 1809 this was a crucial act of conservation that shaped the reputation of the man and the reception of his writings throughout the 19th century. Du Pont’s edition included for the first time some of Turgot’s writings that the latter had not obviously intended for publication or distribution. These previously unseen pieces derived from Turgot’s manuscripts and correspondence to which Du Pont had had sole access for nearly three decades, and which he had guarded closely, even carrying them to America and back.Footnote23 Among the writings published for the first time were, besides various pieces of correspondence, contributions such as the two discourses that the young Turgot had delivered at the Sorbonne in 1750, his Éloge de Gournay of 1759 and Valeurs et monnoies. Such pieces would be hailed by various interpreters of subsequent generations as pioneering contributions. For example, the Éloge de Gournay was given enlarged significance by 19th century French economists who read it as an early clarion call for liberal reform.Footnote24 The Journal des Économistes, for instance, would style this text

the intellectual charter of that imposing liberal school, which would bring forth the economists of the Constituante as well as those who today defend the great conquests of the revolution. That beautiful funeral oration, a critique of the present, was to become the programme of the future (Monjean Citation1844, 62).

Turgot’s adoption as a patron saint by what Schumpeter (Citation1954, 841) called the French “laissez-faire ultras” was not conducive to critical reflections on Du Pont’s role as editor. On several points his presentation was followed uncritically. For example, Du Pont’s lyrical descriptions of Turgot’s personal qualities in the biographical account of 1782, which was included in slightly edited form in volume one of the collected works, were adopted in a succession of 19th century biographies that would sometimes verge on hagiography. More importantly, in the present context, the fidelity of Du Pont’s transcription of various pieces was not subjected to any critical enquiry for many decades. When in 1844 Eugène Daire (1798–1847) published a new edition of Turgot’s Œuvres, he did criticise Du Pont for the order of presentation of the writings, which had been “un véritable chaos en neuf volumes” (Daire and Dussard Citation1844, I, v). In its place Daire offered a thematically ordered selection in two volumes, starting with what by now were seen as Turgot’s most lasting contributions, namely those to political economy, in the first place the Réflexions, then Valeurs et Monnaies etc. However, apart from modernising spellings throughout, Daire simply adopted Du Pont’s transcriptions of the writings, without apparently feeling the need to consult any 18th century versions.

The private collection from which Du Pont had produced many of his transcripts, in the meantime, was largely neglected until the last decades of the 19th century. After Du Pont had finished with these papers, they were returned to the descendants of Turgot’s brother, Étienne François, who were of the Sousmont branch of the family, and who kept them at the chateau of Bons. Subsequently they were moved to Mondeville, and finally, by approximately the middle of the century, to Lantheuil where they were joined to archives of the Saint-Clair branch of the Turgot family.Footnote25 There the collection was occasionally visited, for example in September 1887 by Léon Say (1826–1896).Footnote26

Systematic work on the papers was started in the last decade of the 19th century by Étienne Dubois de l’Estang (1851–1909), who at that time was the custodian of the family archive. Some years later Dubois agreed to collaborate with Gustave Schelle in the preparation of a new collected works. Schelle was the first scholar to subject Du Pont’s transcriptions to a critique. His doubts about Du Pont’s reliability had previously been raised by a study of the significant differences between the text of the Réflexions as it was found in the Œuvres (which reproduced the version that Du Pont had originally published in the Ephémérides) and those of the corrected 1770 off-prints and the 1788 edition.Footnote27 Once Schelle commenced his collaboration with Dubois and was able to study the collection at Lantheuil, he started to find other infidelities. For example, the text of the two discourses that Turgot had presented at the Sorbonne in 1750, had, according to Schelle (Citation1909, 34), been fortement remanié by Du Pont.

When eventually presenting his new edition, the five volume Œuvres de Turgot et documents le concernant (Citation1913–1923), Schelle emphasised the “imperfections” that he had found throughout Du Pont’s edition, and especially in the transcripts based on pieces found in the Lantheuil collection. These errors had required “many further rectifications” (Schelle i, 4). There can be no doubt that Schelle’s edition was a major scholarly achievement. Not only was it the first (and still only) systematic revision of Du Pont’s transcriptions of Turgot’s various writings, it also revised the selection of included materials. In addition to further items that had become available during the 19th century through other publicationsFootnote28, Schelle extended the selection by the inclusion of many previously unknown pieces from the Lantheuil archiveFootnote29 and other archives and by printing a large part of Turgot’s correspondence with Du Pont, which previously had remained hidden in the archive of the latter’s descendants in America.Footnote30 At the same time, he also expressed reservation about some of the pieces that Du Pont had included. For example, he decided not to include some of Turgot’s translations and poetry, for instance the verses of Élégie de Tibulle which Du Pont (ix, 124–127) had transcribed “correctly, bar a few words”, because it was “of insufficient interest to be reproduced” (Schelle i, 235).Footnote31 Another example was that, even while including the early work Le Conciliateur, he seriously contested Du Pont’s attribution to Turgot (cf. n.19).

Schelle’s edition proved to be an enduring contribution. Subsequent generations of scholars often referred to it as the “definitive edition” (e.g., Vigreux Citation1947, 2; Meek Citation1973, 4). Even though subsequent discoveries of further correspondence meant that this was not exactly true as far as the available materials are concerned,Footnote32 Schelle’s superior scholarship in the preparation of transcripts of Turgot’s original writings was rarely contested. Part of the reason for this is that there is simply no question that Schelle’s edition is more accurate than the two previous ones. In addition, however, as was noted, where it concerned the pieces that belonged to the Lantheuil archive, it was for a long time impossible to verify Schelle’s scholarship.Footnote33 Especially these papers would have challenged the abilities and judgement of an editor, since, as was also noted, they comprised writings that Turgot had not intended for publication in the form in which they survived.

The recent availability of the papers of the Fonds Turgot has for the first time made it possible to obtain a more detailed impression of Schelle’s (and Du Pont’s) editorial practices where it concerned these papers. The general impression one gets is that Schelle’s transcriptions did indeed often improve on those of Du Pont. At the same time, however, the former in most cases continued his predecessor’s practice of producing substantially cleaned up versions from the available materials. This involved constructive, and sometimes creative and selective, efforts of producing more intelligible versions from rough drafts. To be fair to Schelle, two somewhat contrasting cases may briefly be mentioned. The first case is the new transcript Schelle (i, 595–622) produced of the Éloge de Gournay, which corrected the “quite numerous changes” (i, 595) that Du Pont had made to the original text. Like the latter, however, Schelle failed to indicate that Turgot had made various corrections and additions to his draft, or that the file from which the transcript was produced contained further initial drafts and pieces of biographical information that had been provided by correspondents.Footnote34 A second case is Turgot’s famous letter to Louis XVI of 24 August 1774, accepting the position of contrôleur généneral. Already during Turgot’s tenure neat copies of this letter, made by his secretaries, started to circulate and soon after it became a prop in the legend of his short period in power. For instance, in 1793 the Literary and Biographical Magazine and British Review (11, July–December, p.244) praised it as “a letter to be recorded in letters of gold”.Footnote35 The draft of this letter, however, far from being a serene piece of writing, is covered with deletions and corrections that testify to Turgot’s struggle to come up with the right wording.Footnote36 In this case Schelle did in fact intimate these features in an indirect manner. After transcribing the letter (iv, 109–113) he reprinted a passage from an article by Dubois de l’Estang (Citation1894). This earlier commentator had noted Turgot’s many alterations and had observed that rather than considering them as imperfections that make the letter difficult to read, and which ought to be ironed-out by an editor, “precisely these deletions and replacements are what is of interest. They show us the laboured efforts of the author and allow us, in a way, to capture in action his methods of redaction”.Footnote37

It must be said that Schelle did not seem to share this interest in Turgot’s process of writing and redaction. Even though he reprinted Dubois’s observations in this case, he did not include similar reflections anywhere else and in this, as in all cases produced clean versions of texts without any indication of what the sources had looked like. The reason to make this point is not to condemn this aspect of Schelle editorial judgement. In the early 20th century there would likely have been commercial reasons as well as editorial conventions that made it unfeasible to produce a collected works of Turgot that paid detailed attention, in its transcriptions and accompanying commentary, to the imperfections of draft manuscripts. But if we may absolve Schelle from misjudgement at the time, this does not mean that we should continue to adopt the same practice of ignoring the various states of Turgot’s writings.

To appreciate these various states, one does of course need access to original sources and as was noted in the introduction, this has remained a problem for a number of texts even after the sale of the Lantheuil archive. The availability of digital images of some of the missing manuscripts now offers this access. The next section aims to give some impression of what may be gained from examining previously unseen drafts.

3. The Japanese collection

The Appendix A to this paper provides a list of items that were previously part of the Turgot family archive at Lantheuil, but are currently missing from the Fonds Turgot. Images of a number of these have recently become available after a search in the late Professor Tsuda’s extensive photograph collection.Footnote38 Since none of the corresponding physical manuscripts are present in the Fonds Turgot, they are currently the only access we have to the originals of these particular texts, most of which have previously been known only through the transcripts produced by Du Pont and/or Schelle.Footnote39

While a closer study of all these documents is likely to provide new insights,Footnote40 here only one piece will be considered in some more detail as a kind of case study. This is the text generally known as “Value and Money”. There can be no doubt that the document of which photographs were found in professor Tsuda’s library was the source for both known transcripts, namely Du Pont (iii, 256–293) and Schelle (iii, 79–98). Especially in the 20th century this contribution has held a special fascination to commentators mostly because Turgot’s discussion has been thought to anticipate by a century the analyses of the phenomena of value and exchange of early neo-classical economists (see, e.g., Kauder Citation1965; Groenewegen Citation1970, Citation1982, Citation1983; Jaffé Citation1974; Hutchison Citation1982; Herland Citation1982; Desai Citation1987; Erreygers Citation1990; Hervier Citation1997; Defalvard Citation1998; Dos Santos Ferreira Citation2002; Theocarakis Citation2006; Menudo Citation2010; Yamamoto Citation2016). However, none of these commentators had the benefit of seeing the original draft of “Value and Money”. An inspection of (photos of) this draft provides new insights, some of which are substantial.

The first, perhaps not substantial yet significant, thing to note is that the very title “Valeurs et Monnoies” may have been given to this text by Du Pont. The only mention of this work during Turgot’s life is likely to be the non-descript reference by Morellet to “your papers on value”, while the main fragment of the text that is found amongst the latter’s papers has the title “Valeur estimative. Valeur appréciative”.Footnote41 Moreover, soon after the author’s death, Du Pont (Citation1782, 107–108) described the document as “un Mémoire très-simple & très-savant sur l’origine des Monnoies” without giving a specific title. It seems possible, therefore, that Du Pont thought of the title Valeurs et Monnoies only at a later stage. It is found on the covering page of the manuscript (spelled as Valeurs et Monnoyes) and at the beginning of the published version in Du Pont’s Oeuvres de M. Turgot (Du Pont iii, 256).Footnote42 Subsequently, the same title was adopted, with a modernised spelling of the last word, by Daire (i, 75) and Schelle (iii, 79) and by subsequent editions and translations.

Turgot might not even have considered a title for the text that we know, because it turns out that it was originally part of a more extended document. On top of the first page of the manuscript the sentence that is known as the beginning of the text,Footnote43 is in fact preceded by a sentence that carries on from a (missing) preceding page. That sentence is crossed out, presumably by Turgot himself, which may suggest that he separated the fragment, subsequently named Valeurs et monnaies, from a longer text.Footnote44 There is no way of telling how much more extended the preceding passages of the original text were and what topics they dealt with. Somewhat similarly, the very end of the text does not exactly break off at the point suggested in the published transcripts. Du Pont and Schelle both reproduce the last full sentence which finishes with “les deux possesseurs des mays offrissent la meme quantité pour la meme quantité de bois”. In the manuscript version, however, there is one further (undeleted) statement that breaks off half-sentence. It reads “la meme cause cause obligeroit les proprietaires […]”. This is a curious end to the text and it raises the question whether, like the beginning of the surviving text, it originally ran over (an) additional (missing) page(s). An argument against this conjecture is that after the broken-off sentence a large part of the page is left empty. This seems to favour the conclusion that Turgot stopped at this point rather than that the text originally continued.Footnote45 Whatever may have been the case, it should be noted that by failing to mention that the document started and ended mid-sentence, both Du Pont and Schelle gave the impression of a more self-contained text than it really is.

More importantly, these previous editors completely ignored a further fascinating feature of the document, namely the many alterations that Turgot made throughout the text to original phrasings of his ideas.Footnote46 This feature of the text is significant for at least two reasons.

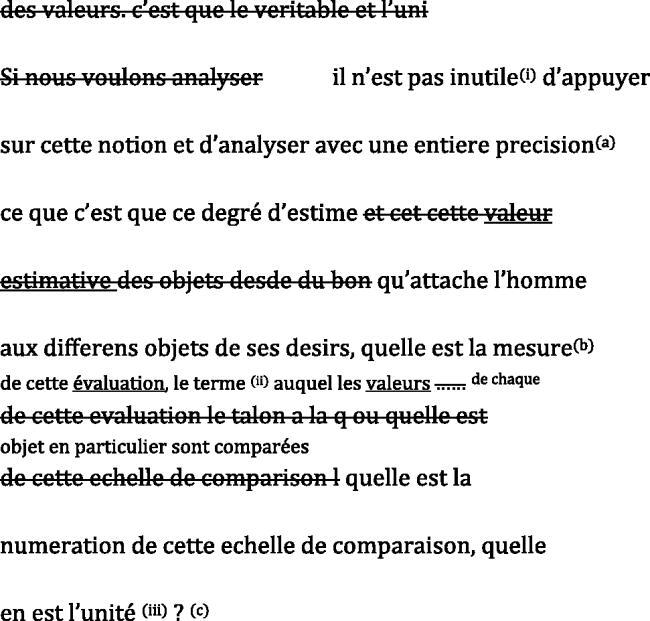

In the first place, the frequent deletions and alternative formulations added between lines or in margins makes the text difficult to read in places. This may explain, at least in part, the differences between the transcripts of Du Pont and Schelle. In the opinion of the latter editor (Schelle, iii, 79) the former had introduced “quite a number of changes” (assez nombreuses alterations) to his transcript of the manuscript. By implication, Schelle claimed that his transcript was more faithful to the original. Partly because Du Pont was known to have taken liberties in editing other writings by Turgot (see above p.6), it has generally been accepted that Schelle’s version was more reliable. The photos of the original show that the issue is not so straightforward. As a single illustration of the way in which the messy nature of Turgot’s draft may have led the two editors to produce different transcripts, we may consider a passage in which the notion is developed that it should be possible to express the subjective “esteem values” an isolated person attaches to various object on some “comparative scale”.

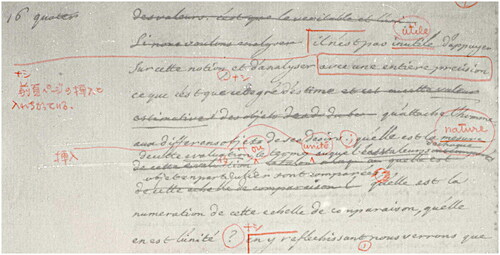

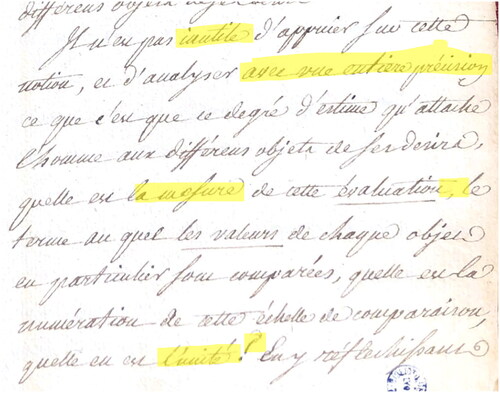

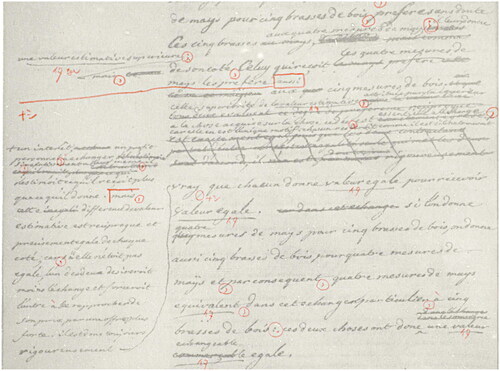

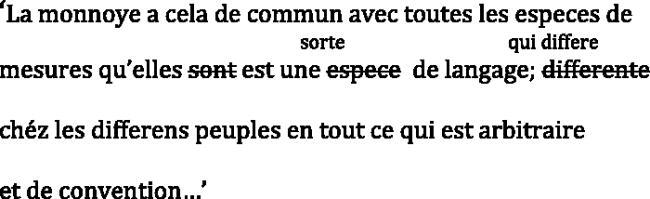

The fragment in gives an impression of the messy state of the passage.Footnote47 A transcript that takes the deletions and rewrites into account is the following:

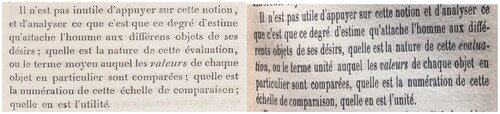

Both Du Pont and Schelle consistently reproduced only the words that were not crossed out and hence tried to decipher Turgot’s rephrasings between the lines ().

Their transcripts disagree on (i) the word “inutile”, for which Schelle has “utile” (ii) the phrase “de cette évaluation, le terme”: Du Pont has “de cette évaluation, ou le terme moyen” and Schelle has “de cette évaluation, ou le terme unité”; and (iii) the word l’unité, for which Du Pont has l’utilité. Arguably, differences (i) and (iii) are simple slips by Schelle and Du Pont respectively. Difference (ii), however, appears to be the result of alternative attempts to slightly “improve” Turgot’s text by adding two words. In addition, it appears that Schelle decided to maintain some inaccurate renderings by Du Pont. That is, both transcripts (a) omit the phrase “avec une entiere precision” (Schelle, but not Du Pont, inserted it instead in the preceding paragraph of the text); (b) the word “mesure” is replaced with “nature”; and (c) the question mark at the end of the passage is not reproduced.

It should be noted that on all six points the neat copy of the passage that is found in Morellet’s papers in Lyon agrees with Turgot’s draft (). Even though that source, unfortunately, yields counterparts for about one third of the text only, it is generally speaking the most reliable version to check the “Lantheuil” manuscript against whenever the wording in the latter is in doubt.Footnote48

It would go too far to say that the differences between, on the one hand, the manuscripts and, on the other, the transcripts of Du Pont and/or Schelle are as frequent throughout the text as they are in this short passage, but they are quite typical for the variations one finds in other places too. This is one good reason why neither published transcript (nor other subsequent published versions that were based on them) can always be relied upon and why it is fortunate that we now have access to the original.

The second, perhaps more important, reason why the original draft provides additional insights is that the many deletions and rewritings tell us something about Turgot’s writing process. This is something that cannot be appreciated from the cleaned-up transcripts of Du Pont and Schelle. The general impression one gets from the frequent alterations is of an author who took great care in, and struggled with, finding mots justes

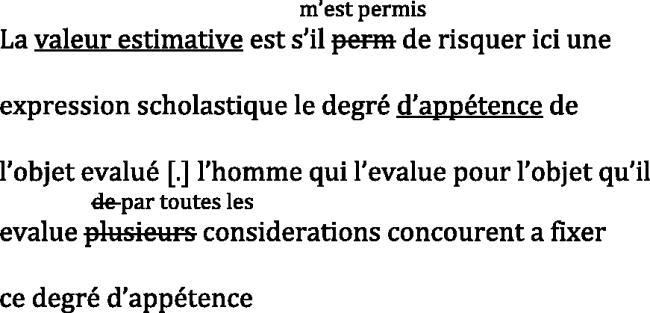

Two illustrations may be given. First, after having earlier introduced the notion of “esteem value” (valeur estimative), the draft manuscript has the following deleted passage (p.27):

This is the only place where Turgot compares his notion of valeur estimative to the scholastic notion of appétence, a French rendering of the Latin appetencia/appetitus or in English “appetite”. The fact that he wondered whether he should be “permitted to risk” this “Scholastic expression”, and the fact that he subsequently deleted the entire passage, suggests that he felt that the comparison may not be appropriate. This reticence may have been based on more superficial considerations, i.e., the general disdain in which Scholastic philosophy was held among litterati of his time and with which one would therefore not want to be associated. Alternatively, Turgot may have been aware that the way in which “appetite” had been understood by, for example, Aquinas was substantially different from what he had in mind. Aquinas’s discussions of the notion had distinguished between natural, sensory and intellectual appetites and had ascribed teleological “good” ends to different classes of tendencies.Footnote49 Turgot’s notion of valeur estimative, by contrast appears to be narrower and more subjective.

Nevertheless, the passage at least shows that he was steeped in the doctrines of the Schoolmen, something which he owed of course to his theological training. Without reading too much into it, the passage is a further indication that Turgot’s intellectual frame of reference was perhaps not so “incredibly modern” (Desai Citation1987, 197) as some commentators have assumed. This intellectual context is more apparent in two of his other writings that also develop one of the central notions in “Value and Money”, namely that in any voluntary exchange both parties would typically “benefit equally”. The idea that voluntary onerous exchanges involve by their nature contracts of equality had a very long history in western legal thought. In an earlier draft, which anticipates some of the arguments worked out at greater length in “Value and Money”, Turgot had actually adopted some of the specific language that was customary in the earlier legal tradition. This can be seen for example in a passage where Turgot gave the following definition of voluntary exchange:

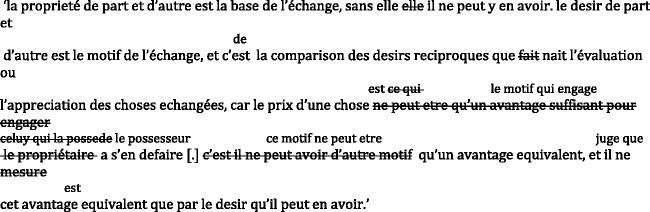

Property on both sides is the basis of exchange; without it exchange could not take place; desire on both sides is the motive of exchange, and it is the comparison of the reciprocal desires from which the evaluation arises, or the appreciation of exchanged things, because the price of a thing, the motive which engages the owner to dispose of it, that motive can be nothing but an equivalent advantage; and he only judges that advantage to be equivalent by the desire which he has for it (Schelle i, 379; emphasis added; my translation).Footnote50

Besides the question why the notion of “equal advantage” in free exchanges was so important to Turgot, despite the fact that later theorists like Edgeworth and Wicksell realised that it is not possible to arrive deductively at a unique exchange ratio in the case of isolated trade between two utility maximising individuals,Footnote52 additional questions have been raised about the way the former attempted to demonstrate this notion in “Value and Money”. One particular passage has often been discussed in which Turgot gives a numerical example that appears intended to illustrate how the average of two esteem values is found. In this example Turgot assumes as the initial positions of two traders meeting on a desert island that ‘[…] the one would exchange three measures of corn for six armfuls of wood, the other would give him six armfuls of wood only for nine measures of corn’ (Groenewegen Citation1977, 142 translated from Daire i, 86). The exchange ratio, or “appreciative value” eventually agreed upon is, according to Turgot, four measures of corn for five armfuls of wood. Commentators have pointed out two kinds of problems with this numerical example.

First, the example appears to contradict Turgot’s contention that both traders gain in the bargain. If the initial positions are to be interpreted as valeurs estimatives, then the corn owner ends up receiving 5 armfuls of wood for 4 measures of corn, while at the outset he ‘esteemed’ 3 measures of corn to be worth as much as 6 armfuls of wood. And the wood owner, who ends up receiving 4 measures of corn for 5 armfuls of wood, ‘esteemed’ 6 of his armfuls of wood to be worth 9 measures of corn. Thus, both traders make concessions to arrive at their bargain, rather than appear to gain in the process.Footnote53

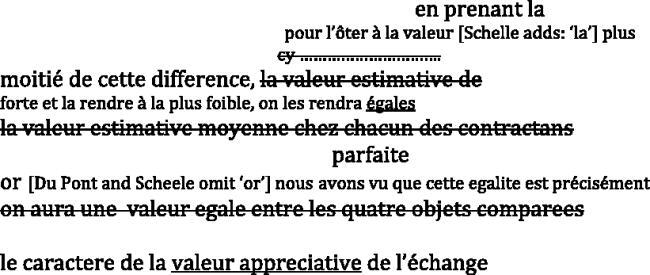

Second, it is hard to see how Turgot arrives at the exchange ratio agreed upon by the two isolated traders. His suggestion of a rule of averaging the difference between their initial ratios, is awkwardly phrased:

by taking half of this difference in order to subtract it from the higher value and to add it to the lower value, they are made equal. We have seen that this perfect equality is precisely the characteristic of appreciative value in exchange.Footnote54

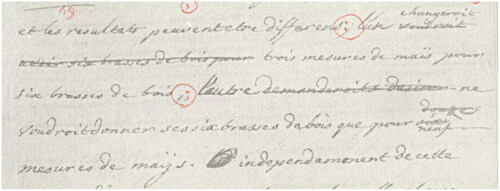

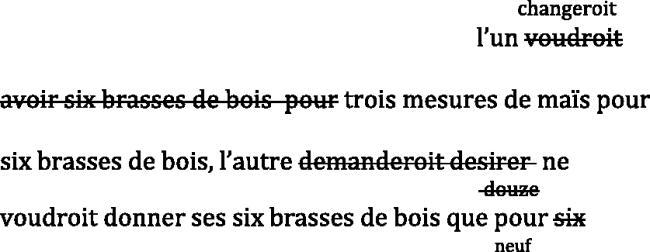

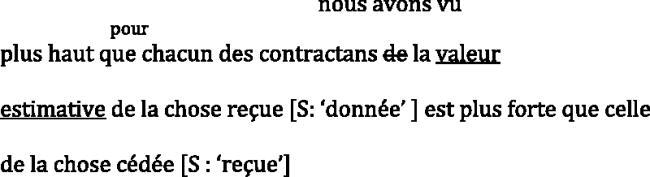

Of course, none of the modern commentators on this contested passage had the benefit of seeing the original manuscript. The neat transcripts by Du Pont and Schelle on which they have had to rely have arguably added to the temptation to read too much consistency into the text and to offer intricate attempts at reconstructing the logic of Turgot’s arguments. If there is any new light that the original draft throws on the difficulties that have been identified in the secondary literature, then it is that Turgot himself also struggled mightily with his example. This can be seen, first, in the passage where he proposes the initial positions (p.23). It shows that he twice changed the initial position of the wood owner ().

Or in transcript:

A likely reason for the double correction (“six” to “twelve” to “nine”) is that Turgot, by considering alternative initial ratios for the wood owner, attempted to find one that would yield a convenient ratio as the solution, when averaged with the initial ratio of the corn owner. If one considers the three alternative ratios then the following average solutions suggest themselves:

The solution when using the second alternative that Turgot considered (but then deleted), is identical to the one he gives a little further in the text. To be precise, by using “wood prices” one obtains the ratio of 5: 4, i.e., averaging 3: 6 and 12: 6. Alternatively, by using “corn prices”, one obtains the ratio of 4: 5, i.e., averaging 12: 24 and 12: 6 which gives 4: 5. If this explains why Turgot used the latter ratio,Footnote55 then this also suggests that he made the second change (turning the initial ratio of the wood owner from 12: 6 to 9: 6) after having written the subsequent passages without also making the required changes to the solution (which would have been to change «4: 5 » to « 1: 1 », or « 3: 4 »).

Of course, this is merely one way to explain the inconsistency in the numerical example. It must be acknowledged that having access to (pictures of) the original manuscript, even though it provides fascinating new insights, does not necessarily mean one can reliably reconstruct Turgot’s thought processes. Instead, a more important conclusion suggests itself. It is that one should be careful not to overinterpret the text. What the original draft exhibits in abundance is the very sketchy nature of Turgot’s analysis. Indeed, the full passage in which the final exchange ratio of “four measures of corn for five armfuls of wood” is proposed (p.24) is perhaps the messiest of the whole text. It is shown in .

This gives us an impression of the text that is very different from what students have been given before. That is to say, the attempts by Du Pont and Schelle to present Turgot’s ideas in a cogent manner turn out to have involved much more editorial effort than could have been suspected by any of the later commentators on this particular contribution of Turgot. The original text, we can see now, was a very tentative draft. This should guard against any overly confident interpretations of the logic of Turgot’s arguments.

4. Conclusion

Over the 240 years since Turgot’s death a corpus formed of what are considered his most significant writings. Our understanding of his writings has evolved with it, and of course with the changing traditions in economic thought and its historiography. At least to some extent the various re-interpretations by successive generations of historians of economic and political thought was shaped by the editions through which Turgot’s writings were handed down. The efforts of the most significant editors, Du Pont in the early 19th century and Schelle in the early 20th century, were crucial for the preservation and propagation of Turgot’s writings.

However, one shortcoming of their editions, as was argued in the preceding sections, is that they paid little attention to the various states in which Turgot had left his writings. Amongst these writings were ones that were clearly authorised for publication by Turgot, for example, the corrected off-prints of the Réflexions of 1770, which he was keen to distribute amongst friends. Others were clean manuscript copies intended for an official readership and, probably, for limited circulation as well, such as the Mémoire de l’usure of 1770. Then there were letters, intended for the eyes of correspondents and possibly for some further dissemination. And finally, there were private drafts that either formed the basis for clean copies or that were abandoned, such as “Valeurs et monnoies”. One interesting feature of this last kind of documents is what they afford us glimpses into Turgot’s thinking and writing processes. At the same time, one needs to be careful not to attribute the same status to such writings as one should to those that he intended to be read. A fuller appreciation of these points can only be obtained by efforts to access the original versions of his writings, as far as this is possible. As long as such originals remain elusive, the photographs from professor Tsuda’s collection are a valuable substitute.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Julia Fleider Marchevsky who acted as the discussant of my paper during the ESHET conference in Padua, and to two anonymous referees.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 By “indirectly” I mean that other editions of Turgot’s writings that have frequently been used by students of his work, derive in turn from either the Du Pont or the Schelle editions without going back to 18th century documents. For example, Daire’s popular two-volume edition of 1844 was a rearranged selection, with modernised spellings, from Du Pont’s edition. Frequently used 20th century compilations such as Vigreux (Citation1947), the Calmann-Lévy edition Turgot. Ecrits économiques (1970) and the selection by Ravix and Romani (Citation1997) were, in turn, adopted from Schelle’s edition.

2 The collection was renamed Fonds Turgot after their transfer. Only a part of the total collection (745AP/1-745AP/102) relates directly to A.R.J. Turgot (primarily the documents in 745AP/38-745AP/53). These have been digitised and made available online. This part of the collection yields relatively few surprises in terms of previously unedited pieces. One exception is discussed in van den Berg and Russell (Citation2020).

3 Digital images are at https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/media/FRAN_IR_054019/c-3se7ehwg2-6bezeegugzbx/FRAN_0041_0988_L; https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/media/FRAN_IR_054019/c-3se7ehwg2-6bezeegugzbx/FRAN_0041_1082_L and https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/media/FRAN_IR_054019/c-4u9ryhtsv–14w9l2g7i0kdl/FRAN_0041_2341_L, respectively.

4 The absence from the collection of these pieces first became horribly apparent to me in December 2015 when Ms. Aristide-Hastir of the Archives Nationales kindly sent me an inventory of the acquired collection. It allowed a comparison between what had been sold and the information about the erstwhile contents of “AL” that can be pieced together from Schelle’s edition (for my initial findings see https://listserv.yorku.ca/cgi-bin/wa?A2=2106b&L=SHOE&D=0&P=10604829). A fuller listing of the pieces missing from the Fonds Turgot is given in the appendix.

5 During the 1960s and 1970s, professor Tsuda visited various French archives where he photographed many documents. From 1967 he visited the Lantheuil collection on several occasions. For further details about professor Tsuda’s life, see Nishizawa and van den Berg (Citation2021). In September 2022 the Archives Nationales made a selection of images from this photograph collection available online alongside the digital version of the Fonds Turgot. Special thanks are due to the family of Professor Tsuda for giving permission for the photographing of the images and to professors Tamotsu Nishizawa and Tomomi Fukushima, both of Teikyo University, Tokyo, for their indispensable help in allowing me to identify the relevant documents and in arranging for their reproduction.

6 Parts of three official reports by Turgot were also already published during his life and these would be republished during the early years of the Revolution (see notes 13, 14 and 15). In addition, Turgot published some translations, including in 1755 Questions importantes sur le commerce based on Josiah Tucker; works dealing with religious tolerance, Le Conciliateur in 1754 (see n.19) and Vérités opposées […] Bélisaire in 1767 and some pieces of poetry. A short version of his Éloge de Gournay was also published in 1759 (see n.24).

7 We know for instance that Turgot had neat manuscript copies made of the Discours aux Sorboniques (letter to Caillard 16 Oct. 1770 in Schelle iii, 417). The arguments in this early work were known, for instance, to Hume (see letter dated 16 June 1768 in Greig 1932, 179–181). Other neat copies of some pieces written in his capacity of Intendant have survived such as the copy of the Mémoire sur l’usure (see n. 15) and copies of letters 5, 6, and 7 of the letters on the grain trade. Also see n.36.

8 A month after Turgot’s death, in April 1781 Du Pont stated in a letter to Malesherbes that “only I have all his manuscripts” (cited in Schelle Citation1888a, 213, n.1).

9 Du Pont (Citation1782). A second edition was published in 1788.

10 Letter dated 12 September 1770 in Tucker (Citation1782, 3rd ed., ix–xiii). On page 92 Tucker mentions another letter he had received from Turgot dated 18 February 1777, but only quotes a single phrase about the republican nature of the new American nation. This letter was never published and is missing. Another letter purportedly addressed to Tucker (dated 10 December 1773) was first published in 1810 by Du Pont (ix, 369–375). In fact, however, it can be shown that the addressee was in fact the much less well-known Englishman, Joseph Wimpey (1712–1795). See van den Berg (Citation2021).

11 Letter dated 22 March 1778 in Price (Citation1785, 88–106). The letter was also included in Honoré de Mirabeau (Citation1785). Turgot’s criticisms of the constitutions of some emerging American states turned out to be controversial in the new world and prompted John Adams’s lengthy Defense of 1788. See Thomas (Citation1977, 170–178).

12 A year of publication is missing on the latter pamphlet, but Schelle’s supposition that it was 1788 is confirmed by a notice in the Gazette de France of 17 June 1788 (202). Place of publication and publisher are omitted, but the notice states that the work was for sale at “Desenne au Palais-Royal”. This notice appeared soon after permission for publication had been granted on 4 June 1788, after this work had been submitted to the censor together with the 1788 editions of Le Conciliateur, the Réflexions and Mémoire sur les administrations provinciales. See BnF Archives et manuscrits Fr. 21987 Registres des permissions tacites 1784-1789, p.104. I thank Gabriel Sabbagh for this last reference (private correspondence 2/5/22). Cf. notes 19, 18 and 16 respectively.

13 These two texts, written in 1773 and 1770 respectively, were published together. Excerpts of the latter text, taken from an official manuscript copy, had already appeared in 1780 in a work reputedly by the abbé Gouttes. As far as I know, the only known manuscript copy, with the title Mémoire sur l’usure, is in the Goldsmith Library. It accords precisely with the paragraph references given by Gouttes.

14 This publication followed the version of the text as it had appeared in the Ephémérides du citoyen text in 1767 and was published in Paris by Froullé.

15 This little-known reprint has “An VI” on its frontispiece and gives as publisher “Chaignieau aîné”. On the last page (p.58) it has “A Limoges, le 20 septembre 1766”. Parts of the report had already been published in the Ephémérides du citoyen in 1767, in support of Quesnay’s distinction between petite and grande culture. This edition may be related to the rare prints made on behalf of a lesser-known son of Mirabeau around 1788/9. I thank Gabriel Sabbagh for the last point (private correspondence 20/2/21).

16 This memoire on administrative reform was written by Du Pont under the instruction of Turgot. About the complicated history of its publication see Schelle (iv, 568–574). About its reception in the early revolution see Whatmore (Citation1996).

17 Turgot wrote this piece of advice to the king not to get militarily involved in the fight between Britain and its colonies in April 1776. It was published by Du Pont in Citation1791a. For an earlier English translation of most of this piece and the inclusion in a French work by Mazzei in 1788 see De Vivo and Sabbagh (Citation2015).

18 This edition, later acknowledged as the most faithful version (see n.27), was advertised in the same notice in the Gazette de France as being for sale with the bookseller “Desenne au Palais-Royal, no 142”, in the same octavo format and with the same prices of 2 livres as the 1788 editions of the letters on the grain trade (see above n.12). This may suggest that the two publications were initiated by the same person. Against this conjecture however, it should be noted that the two productions look quite different from each other.

19 This work was first published in small numbers in 1754. The 1788 edition is normally attributed to Naigeon and the Citation1791b edition was due to Du Pont. Schelle (i, 391–392 n.a) contested that Turgot was the author, but it is safest to conclude that this issue is not settled.

20 The roles of Du Pont and Condorcet in some of these publications have often been discussed (see Groenewegen Citation1974). Rieucau and Sabbagh (Citation2022) provide further details of especially Condorcet’s role. Those of others, like Naigeon, Mirabeau the younger, La Rochefoucauld and Brissot could perhaps be explored further.

21 The reception of Turgot’s writings within the context of various political disputes during the Revolution is a fascinating subject that cannot be discussed here.

22 Different editions of the English translation appeared in 1791, 1793, 1795, and 1801. De Vivo and Sabbagh (Citation2015) appear to have settled the longstanding question of the identity of the translator by identifying Benjamin Vaughan (1751–1835). The English translation of Condorcet’s Life of M. Turgot (1787), which was very likely due to Vaughan as well, also included a translation of “Fondation”.

23 For an account see Saricks (Citation1965, 314–315), see also Du Pont’s own admission (ix, iii) of the “audacity of daring to cross the Atlantic twice with so many precious manuscripts”.

24 The short version that had already been published in the Mercure de France (August 1759, 201–210) had left out most of Turgot’s “programmatic” reflections. The version published by Du Pont (Oeuvres vol. iii, 320–375) was soon quoted at length by Dugald Stewart in notes added to his “Account of the Life and Writings of Adam Smith, LL.D.” (see Stewart Citation1811, 139–144), and was given as evidence of the growth of free trade thinking in both France and Britain. The edition of Daire and Dussard (Citation1844, I, 262–291), which was the occasion for Monjean’s long article, raised the reputation of Turgot’s Éloge further, becoming a reference point for various liberal economists of 19th century for the origin the phrase “laissez faire, laissez passer”, as chronicled by Oncken (Citation1886).

25 See Dubois de l’Estang (Citation1894).

26 See his breathless account “Les papiers de Turgot” in Le Journal des débats, of 27 September 1887. This liberal French statesman and grandson of the economist Jean-Baptiste Say, described his visit as a kind of pilgrimage during which he had what can best be described as a quasi-religious experience, when the grand ministre, despite being dead for a century, appeared in Say’s presence: “Holding in my hand the paper on which the great minister dashed off the famous programme that he offered to Louis XVI, I believed for an instant that he was with me, that the fine figure in the pastel painting by Ducreux hanging on the wall, came alive and repeated to me in that penetrating voice, so precious to those who loved him […], what he said to the king, when taking charge of the contrôle general: ‘These people, for whom I will sacrifice myself are so easily led astray that, perhaps, I will incur their hatred from the measures that I will take to defend them against harassment’”.

27 Schelle (Citation1888b) is a classic contribution to Turgot scholarship, which established the superiority of the 1788 edition, something ever since accepted by all students. See, e.g., Meek (Citation1973) and Groenewegen (Citation1977).

28 For instance Daire and Dussard (Citation1844) had included 25 previously unpublished letters of Turgot and had reprinted Turgot’s 1755 translation of Tucker, with notes. Vignon (Citation1862) had published Turgot’s correspondence with the Trudaines, Henry (Citation1883) had published many of the letters between Turgot and Condorcet, Kniess (Citation1892) had published Turgot’s letters on criminal justice. All of these were adopted by Schelle.

29 Schelle especially selected many early writings present in the Lantheuil collection that Du Pont had decided not to use. The fact that very few unknown pieces are found in the Fonds Turgot shows that his use of that collection was rather comprehensive (cf. note 2 above).

30 Schelle had first realised the significance of this correspondence when preparing his first work, Schelle (Citation1888a) and had established contacts with Henry Algernon du Pont (1838–1926).

31 Since this piece is amongst manuscripts missing from the Fonds Turgot (see appendix), Du Pont’s transcript is the only one we have.

32 For instance, Turgot’s extensive correspondence with the duchesse d’Enville, which Schelle tried to locate in vain (see Schelle i, 7 n.1) was later found in Belgium and published by Ruwet in Citation1976; other letters have continued to resurface.

33 See Groenewegen (Citation1977, xxxiv, n.124) for an instance of an unsuccessful attempt to get access to the originals in order to verify existing transcripts.

34 745AP/40, dossier 2 (See https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/media/FRAN_IR_054019/c-3se7ehwg2-6bezeegugzbx/FRAN_0041_0988_L). The related materials start with image 30, which is a title page. Images 31-39 show two initial drafts; images 41-42 show another early sketch with various questions about Gournay’s life on the right-hand side answered on the left. It includes an intriguing statement (im.41): ‘En 1744 [Gournay] en angleterre et en hollande pour augmentere ses liaisons de commerce, et ses connoissances dans le commerce. il a beaucoup connu le ministre walpole et le lord chesterfield. il Ecrivit unjour [toujours?] a ce dernier…’. Image 43 shows the beginning of a long letter to Marmontel dated Paris 22 July, as reproduced in Schelle (i, 595), which continues with the known version of the Éloge reproduced in Schelle (i, 595–622). This letter has 48 numbered pages (presented out of order) and runs from images 43 to 79. It contains frequent corrections and additions not indicated by Schelle. This is followed by images 80–92 that show Gournay’s obituary in the Mercure de France with annotations by Turgot. Finally, images 93-95 show a letter from Jean Gabriel Montaudoin de la Touche 91722-1781) which provides further biographical details about Gournay.

35 For the lyrical description of the letter by Leon Say see note 26 above. Since Say saw the Lantheuil version he must have known that it was not actually flamboyantly “dashed off” (écrit, au courant de la plume).

36 The letter is in AN 745AP/44 dossier 1. See https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/media/FRAN_IR_054019/c-9q0akhscm-w2su4qd7t8ur/FRAN_0041_2895_L. A neat version of the letter is reportedly in AN AA//71.

37 Dubois went on to give an analysis of what he believed Turgot’s style of writing and redaction to be. While this discussion now seems dated, the very focus on the state of writing and what it may say about the author’s process of composing his writings is rather modern.

38 The size of the full collection is very large, comprising photographs made in many French archives in the later 1960s and early 1970s. A full inventory is in the process of being drawn up by scholars in Japan as part of a project that aims to make Tsuda’s collection available to researchers.

39 Brief comments in the appendix on most of these manuscripts will need to suffice here.

40 In fact, Tsuda (Citation1974) already examined four different drafts in the Lantheuil archive of Turgot’s discours of 1750 (item 5 of the appendix). His pioneering study, being published in Japanese which accompanied French transcripts of the drafts, was hard to appreciate, at least before to the advent of reliable AI-aided translations, by scholars unable to read that language.

41 For a study of this and other fragments of “Value and Money” in Morellet’s manuscripts in Lyon, see van den Berg (Citation2014), written at a time when the only comparison possible was with the transcripts of Du Pont and Schelle. About the relation between the Lyon version and the Lantheuil draft considered here, see below n.48.

42 The title page of the manuscript is, however, probably of a later date: under the title a comment is included in the same hand (possibly that of Dubois de l’Estang), which refers to Du Pont’s edition as having “asses exactement reproduit” the original and dates the latter to “1767 or 1768”. Admittedly, it is possible that the title of the text as found in Du Pont’s edition occurred on a title page, now lost, that was due to Turgot. See https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/mm/media/download/FRAN_ANX_013449.pdf

43 This sentence reads in the manuscript (including original wording and corrections):

44 Another, maybe less likely, possibility is that the part that has survived was only separated from the preceding page(s) by someone else at a later date. It seems impossible to be sure. In any case, given the fact that there are many deletions on the surviving pages, the fact that the part-sentence on the top of the first page is crossed out may not constitute strong evidence that Turgot decided to separate the surviving pages from a text that was originally longer.

45 Note however that in one place earlier in the manuscript the text also stops half-page, only to be continued on the next. Previously Groenewegen (Citation1977, xxvii) speculated about the possibility that a longer version may have existed and in van den Berg (Citation2014) is argued that fragments found in Morellet’s manuscripts may be seen as confirming this suspicion. These additional fragments are not found in the “Japanese” version.

46 Prior to having the photos, the only way of trying to establish whether the original document was a clean copy or a messy draft was to ask the only person known to have seen it. The reply I received from professor Tsuda to my query led me to believe that the document is question was a clean text (see van den Berg Citation2014, n.27). There may have been a miscommunication.

47 Professor Tsuda’s annotations, in red pen, add to the impression of messiness, but they were made on his photographs of the document and are of course not expected to appear on the (still elusive) original. What is clear from these annotations is that Tsuda meticulously compared the wording of the manuscript with Schelle’s transcript. In picture one, the annotations in Japanese in the left margin relate to discrepancies with that transcript. The first two annotations concern the phrase “avec une entiere precision” and state that Schelle “deleted” it and “inserted [it] on the previous page”. The third annotation says that Schelle “inserted” the word ou.

48 Van den Berg (Citation2014) provides a transcript of the Lyon fragments. At the time I assumed that these fragments could be considered accurate renderings of the wording of the Lantheuil manuscript. This assumption is vindicated by Tsuda’s photographs. What I could not appreciate at the time of writing was one significant difference between the two versions: the version in Lyon must have been produced as a neat copy from the very messy original draft that ended up at Lantheuil.

49 For an introduction to Aquinas’s notions of appetite see Kenny (Citation1994) chapter 5.

50 Schelle transcribed this passage from a document now in the Fonds Turgot (see https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/media/FRAN_IR_054019/c-3se7ehwg2-6bezeegugzbx/FRAN_0041_0970_L). The original passage contains some deletions and corrections and reads:

51 For detailed studies of this tradition see Gordley (Citation1991, Citation2006).

52 For this point see, e.g., Groenewegen (Citation1970, 189) or Faccarello (Citation1992, 275). Some commentators have demurred. Defalvard (Citation1998) argued at some length that Turgot’s unique exchange ratio can be obtained in an analytically consistent manner as long as it is assumed that the bargaining power of the parties is equal. Dos Santos Ferreira (Citation2002), for his part, examined Turgot’s notion of “equality in exchange” in terms of modern cooperative game theory, which allows for formal solutions to the indeterminacy of the exchange ratio in situations of isolated exchange (bilateral monopoly) by means of an agreed sharing rule. The equal sharing of benefits of exchange is one such sharing rule. Given the historical context, the latter reading is perhaps less likely to be a correct portrayal of what Turgot intended to do. In “Value and Money” he appears to distance himself from the jurisprudential idea that equality in exchange is something that is intended by contracting parties and a “principle of justice” shared by the individuals involved. Instead, he tried to portray it as the unintended outcome of the confrontation of the subjective and opposing wills of contracting parties.

53 Readers of Schelle’s transcript are more likely to have noted this contradiction because of two infelicitous alterations made by this editor to the conclusion Turgot draws from his example (p.26; replacement words by Schelle in brackets):

Thus Schelle reverses the meaning of the sentence, which now implies that both parties lose in the exchange. While this editor may have found this change necessary to make Turgot’s statement consistent with the numerical example, it contradicts the latter’s other statements that both traders “gain equally”. At the same time, Schelle’s intervention is likely to have had the inadvertent effect of focusing the attention of some later readers on this issue. As Hervier (Citation1997, 88–91) pointed out, two solutions to this problem with the numerical example have been proposed. Some commentators assume that Turgot made the mistake of reversing the esteem values of the two traders. Once this mistake is corrected it is clear both traders gain in the exchange. It should be noted that several commentators fail to state that they adopt this ‘correction’ when interpreting Turgot's example. With the correction, the situation becomes that the owner of wood thought 6 armfuls of wood to be worth 3 measures of corn, and he ends up getting as much as 4 measures of corn for 5 armfuls of wood; the owner of corn, for his part, thought 9 measures of corn to be worth 3 armfuls of wood, but he ends up receiving as much as 5 armfuls of wood for 4 measures of corn. An alternative solution to the “reversed esteem values approach” is to argue that the initial positions of the two traders are not their esteem values at all, but their “initial trial bid based on the estimate of the other trader’s minimum acceptable “price”” (Jaffé Citation1974, 381 n.2). This reading is supported by Turgot's remarks that the traders keep their esteem values “secret” from each other and that they “sound out” each other “by lower offers and higher demands” (1977, 142). While the interpretation that the initial positions do not express esteem values appears sound, it also implies that the numerical example is not actually illustrating Turgot’s central contention, namely that both traders gain equally.

54 The rephrasings of this passage in the manuscript shows that Turgot struggled for a formulation. In transcript it reads:

55 In favour of this interpretation is that in the manuscript (24) the first sentence where Turgot writes his solution of four measures of corn for five measures of wood, there is a deletion that suggests that he initially was going to write that in the final exchange the corn owner would receive four, rather than five, units of wood. These alternative formulations would be consistent with a wavering between ratios obtained with either “wood prices” or “corn prices”. In transcript the passage reads: “au moment où l’échange se fait, la val celuy qui donne son maÿs pour quatre par exemple quatre mesures de mays pour cinq brasses de bois". After this statement Turgot consistently sticks with four measures of corn for five armfulls of wood.

References

- Condorcet, J.-A.-N. de Caritat, marquis de. 1787. The Life of M. Turgot, Comptroller General of the Finances of France in the Years 1774, 1775 and 1776. London: Johnson.

- Condorcet, J.-A.-N. de Caritat, marquis de. 1786. Vie de M. Turgot. London.

- Daire, E., and H. Dussard. 1844. Œuvres de Turgot. 2 Vols. Paris: Guillaumin.

- Defalvard, Hervé. 1998. “Valeurs et Contrats à la Lumière de Turgot [1769].” Revue économique 49 (6): 1573–1599. doi:10.2307/3502624.

- De Vivo, G., and G. Sabbagh. 2015. “The First Translator in English of Turgot’s Réflexions sur la Formation et la Distribution des Richesses: Benjamin Vaughan.” History of Political Economy 47 (1): 185–199. doi:10.1215/00182702-2847363.

- Desai, M. 1987. “A Pioneering Analysis of the Core: Turgot’s Essay on Value.” Recherches Économiques de Louvain 53 (2): 191–198. doi:10.1017/S0770451800083135.

- Dos Santos Ferreira, R. 2002. “Aristotle’s Analysis of Bilateral Exchange: An Early Formal Approach to the Bargaining Problem.” The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 9 (4): 568–590. doi:10.1080/0967256021000024709.

- Dubois de l’Estang, E. 1894. “Turgot et la famille royale.” In Association française pour l’avancement des sciences. Congrès de Caen. Paris: Chaix.

- Du Pont, P.-S. 1782. Mémoires sur la vie et les ouvrages de M. Turgot. Philadelphie: ministre d’État.

- Du Pont, P.-S., ed. 1787. Œuvres posthumes de M. Turgot, ou Mémoire de M. Turgot sur les administrations provinciales, mis en parallèle avec celui de M. Necker, suivi d’une Lettre sur ce plan et des Observations d’un républicain sur ces mémoires et en général sur le bien qu’on doit attendre de ces administrations dans les monarchies. Lausanne.

- Du Pont, P.-S., ed. 1791a. Mémoire sur les colonies américaines, sur leurs relations politiques avec leurs métropoles et sur la manière dont la France et l’Espagne ont dû envisager les suites de l’indépendance des États-Unis de l’Amérique, par feu M. Turgot. Paris: Du Pont.

- Du Pont, P.-S., ed. 1791b. Le Conciliateur, ou Lettres d’un ecclésiastique à un magistrat sur les affaires présentes, par feu M. Turgot. Paris: Du Pont.

- Du Pont, P. S. 1808–1811. Œuvres de M. Turgot, Ministre d’état, Précédées et Accompagnées de Memoires et de Notes Sur sa vie, Son Administration et Ses Ouvrages. 9 Vols. Paris: Bellin.

- Erreygers, G. 1990. “Turgot et le fondement subjectif de la valeur.” Cahiers d'économie politique 18 (1): 149–169. doi:10.3406/cep.1990.1103.

- Faccarello, G. 1992. “Turgot et L’économie Politique Sensualiste.” In Nouvelle Histoire de la Pensée Economique, Vol. i, 254–288. Paris: Editions de la Découverte.

- Gordley, J. 1991. The Philosophical Origins of Modern Contract Doctrine. New York: OUP.

- Gordley, J. 2006. Foundations of Private Law. Property, Tort, Contract, Unjust Enrichment. Oxford: OUP.

- Groenewegen, P. D. 1970. “A Reappraisal of Turgot’s Theory of Value, Exchange and Price Determination.” History of Political Economy 2 (1): 177–196. doi:10.1215/00182702-2-1-177.

- Groenewegen, P. D. 1974. “[Review of R.L. Meek’s] Turgot on Progress, Sociology and Economics.” History of Political Economy 6 (4): 478–481. doi:10.1215/00182702-6-4-478.

- Groenewegen, P. D. 1977. The Economics of A.R.J. Turgot. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Groenewegen, P. D. 1982. “Turgot: Forerunner of Neo-Classical Economics?” Keizai Kenkyu 33 (2): 119–133.

- Groenewegen, P. D. 1983. “Turgot’s Place in the History of Economic Thought: A Bicentenary Estimate.” History of Political Economy 15 (4): 585–616. doi:10.1215/00182702-15-4-585.

- Henry, C. 1883. Correspondance inédite de Condorcet et de Turgot, 1770–1779. Paris: Charavay frères.

- Herland, M. 1982. “En marge d’un bicentenaire: valeur et prix chez Turgot.” Revue Économique 33 (3): 426–445. doi:10.2307/3501332.

- Hervier, A. 1997. “Juste Prix et Valeur Chez Turgot.” Economies et Sociétés 25 (1): 71–107.

- Hutchison, T. W. 1982. “Turgot and Smith.” In Turgot économiste et administrateur, edited by C. Bordes and J. Morange, 33–45. Paris: PUF.

- Jaffé, W. 1974. “Edgeworth’s Contract Curve: Part 2. Two Figures in Its Protohistory: Aristotle and Gossen.” History of Political Economy 6 (4): 381–404. doi:10.1215/00182702-6-4-381.

- Kniess, C. 1892. Carl Friedrichs von Baden Brieflicher Verkehr mit Mirabeau und Du Pont. Heidelberg: Winter.

- Meek, R. L. 1973. Turgot on Progress, Sociology, and Economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Menudo, J. 2010. “Perfect Competition in a.-R.-J. Turgot: A Contractualist Theory of Just Exchange, Économies et Sociétés, série PE.” Histoire de la pensée économique 44,12: 1885–1916.

- Mirabeau. 1785. Considerations on the Order of Cincinnatus; to Which Are Added, as Well Several Original Papers Relative to That Institution, as Also a Letter from the Late M.Turgot, Comptroller of the Finances in France To Dr. Price, on the Constitution of America; and an Abstract of Dr. Price’s Observations on the Importance of the American Revolution. London: Johnson.

- Naigeon, ed. 1788. Le Conciliateur, ou Lettres d’un ecclésiastique à un magistrat sur les affaires présentes, par feu M. Turgot. S.l.

- Nishizawa, T., and R. van den Berg. 2021. “Obituary: Takumi Tsuda (1929–2021).” The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 28 (6): 1041–1043. doi:10.1080/09672567.2021.1967431.

- Kauder, E. A. 1965. History of Marginal Utility Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Kenny, A. 1994. Aquinas on Mind. Paperback ed. London and New York: Routledge.

- Price, R. 1785. Observations on the Importance of the American Revolution, and the Means of Making It a Benefit to the World. To Which is Added a Letter from M. Turgot, Late Comptroller-General of the Finances of France. Dublin: White, Whitestone et al.

- Monjean, M. 1844. “Oeuvres de Turgot.” Journal des économistes 9: 56–74.

- Oncken, A. 1886. Die Maxime Laissez faire et laissez passer. Ihr Ursprung, ihr Werden. Berner Beiträge zur Geschichte der Nationalökonomie. Vol. 2. Bern: Wyss.

- Ravix, J.-T., and P.-M. Romani. 1997. Anne Robert Jacques Turgot. Formation et distribution des richesses. Paris: Flammarion.

- Rieucau, N., and G. Sabbagh. 2022. “Jefferson’s Unknown Informant on Necker in 1789: An Episode of Diplomatic History Involving Condorcet.” History of European Ideas 48 (6): 764–777. doi:10.1080/01916599.2021.1997158.

- Ruwet, J. 1976. Lettres de Turgot à la duchesse d’Enville (1764-74 et 1777-80). Louvain: Bibliotheque de l’Universite/Leiden: Brill.

- Saricks, A. 1965. Pierre Samuel Du Pont de Nemours. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas.

- Schelle, G. 1888a. Du Pont de Nemours et l’école physiocratique. Paris: Guillaumin.

- Schelle, G. 1888b. “Pourquoi les “Réflexions” de Turgot sur la formation et la distribution des richesses ne sont-elles exactement connues?” Journal des économistes 47, 3: 2–16.

- Schelle, G. 1909. Turgot. Paris: Alcan.

- Schelle, G. 1913–1923. Oeuvres de Turgot et documents le concernant. 5 Vols. Paris: Félix Alcan.

- Schumpeter, J. A. 1954. History of Economic Analysis. London: Routledge. Reprint 1994.

- Stewart, D. 1811. Biographical Menmoirs of Adam Smith, LL.D. of William Robertson, D.D. and of Thomas Reid, D.D. Edinburgh: Ramsey.

- Theocarakis, N. J. 2006. “Nicomachean Ethics in Political Economy: The Trajectory of the Problem of Value.” History of Economic Ideas 14 (1): 9–53.

- Thomas, D. O. 1977. The Honest Mind: The Thought and Work of Richard Price. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tsuda, T. 1974. “Churugo no Mihappyōshiryō [The Unpublished Materials of Turgot].” Economic Review, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo, 25, 1 (January) 50–67, Part 1; 25, 2 (May) 131–161, Part 2.

- Tucker, J. 1782. Cui Bono? Or, an Inquiry, What Benefits Can Arise Either to the English or the Americans, the French, Spaniards, or Dutch, from the Greatest Victories, or Successes, in the Present War?: Being a Series of Letters, Addressed to Monsieur Necker, Late Controller General of the Finances of France. London: Cadell

- Van den Berg, R. 2014. “Turgot’s Valeurs et Monnaies: Our Incomplete Knowledge of an Incomplete Manuscript.” The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 21 (4): 549–582. doi:10.1080/09672567.2013.792362.

- Van den Berg, R., and D. Russell. 2020. “Turgot’s Calculations on the Effects of Indirect Taxation.” The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 27 (6): 983–1010. doi:10.1080/09672567.2020.1790622.

- Van den Berg, R. 2021. “Turgot and Wimpey on the Collection and the Uses of Economic Data.” Paper Prepared for the THETS conference in Chester.

- Vigreux, P. 1947. Turgot Textes Choisis Paris: Dalloz.

- Vignon, E. J. M. 1862. Études historiques sur l'administration des voies publiques en France aux dix-septième et dix-huitième siècles. Vol. 3. Paris: Dunod

- Whatmore, R. 1996. “From Constitution-Building to the Reformation of Manners: Three Theories of Modern Citizenship in France, 1763-1793.” In Contemporary Political Problems, edited by I. Hampsher-Monk, 1234–1242. Belfast: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Yamamoto, E. 2016. “Churugo to Gurasuran No Shukankachiriron [The Roles of A. R. J. Turgot and J.-J.-L. Graslin in the Subjective Theory of Value in the Late 18th Century].” The History of Economic Thought 58 (1): 21–48. doi:10.5362/jshet.58.1_21.

Appendix A.

Turgot’s missing manuscripts

Below is a list of items (manuscripts, letters) that were once part of the family archive of the Turgot family at the castle of Lantheuil, Calvados, Normandy. For all, apart from items 1 and 5, this claim is based on Gustave Schelle’s indications of “AL” (Archives de Lantheuil) as source for various transcriptions throughout his classic Oeuvres de Turgot. Since the sale of the family archive in 2015, and its transfer to the Archives Nationales, none of the listed items have been recovered. However, in some cases (items 6, 7 and 19) alternative versions are located in other archives, and in other cases (items 1, 3, 4, 5, 16, 22 and 23) photographs have been found in the late professor Takumi Tsuda’s collection. It should be noted that the list may not be complete.