This publication marks the third in a series of special issues arising from the SOAS Annual Philippine Studies Conferences. After previously exploring the North (the Cordilleras in 2020) and the South (Mindanao in 2022), this edition circles back and focuses its attention on the central region of the Philippine Archipelago: the Visayas. The five-day conference, held completely online right in the middle of the pandemic, brought together a phenomenal set of scholars, writers and artists into a virtual conference room – the highest number we have had on record – with three keynote and plenary speakers each, twenty-four paper presenters, fifteen artists, two feature films and twenty shorts produced specially for the conference. The online format also engendered the creation of a virtual exhibit that the Brunei Gallery co-hosted with Philippine Studies at SOAS University of London.

The fundamentals

When we first began to conceptualize the rudiments of the conference, we knew that like the other Philippine geographies we had previously focused on, the Visayas would be a contested construct – spatially, linguistically and even socio-politically. In our conference communiqués, would we use the English translation of the endonym of the region? Was there an obligation to disrupt the orthography of the languages of colonization and spell Visaya with a B, the way one hears it spoken by native speakers? Our rather safe decision was to use English as the language for the addresses and presentations, and by default the orthography we recommended in the articles that would proceed from them. But the slipperiness of the language, even at this very basic level, would come up again and again, not only during the conference itself but also in the final editing of the articles for this special issue.

In the same way, we needed to do some bean-counting. Which islands were included in the Visayan region and why? And how did the Visayas, as a collective spatial term, expand or contract through time? As a geographical unit, we worked with incontestable inclusions – starting with the island of Panay, marked by the earliest historical designation (Baumgartner Citation1974), followed by six of the island provinces, namely Negros, Cebu, Bohol, Leyte, Samar and Siquijor, plus a clustering of a couple of hundred smaller islands enclosed by the Visayan Sea. Despite the protestations during the Q and As at the Conference, we stuck to our non-inclusion of Palawan, Romblon and Mindoro, and the rest of the MIMAROPA Region (only established by Republic Act 10879 in July 2016), despite these islands’ deep linguistic and historical connections to the Visayas.

Additionally, we needed to deal with diacritic marks. Born in Cebu myself, I was acutely aware of the significance of the Tagalog inflection of Bisáya as opposed to the Cebuano (Sugbuanon) way of saying Bisayâ. Embodied in these seemingly trivial inflections were centuries-old political and linguistic come-uppances, not only between the central Tagalog regions of Luzon, but also with the other provinces and ethnolinguistic groups within the Visayan region itself. At the conference, there were obvious tensions surrounding not only Manila but also Cebuano imperialism, the latter hogging the term Bisayâ or Bini-sayâ as being equivalent to the Cebuano language and the lingua franca of the Visayas, when in fact, there are four other major languages in the Visayan region: Waray, Hiligaynon, Kinaray-a and Akeanon. During the open discussions at the Conference, for example, a person born and raised in Iloilo City said he would rather identify as Ilonggo than Bisayâ, and that he would not consider Hiligaynon as Binisayâ (here equal to the Cebuano language). To complicate it even further, someone born in Samar would more likely say he is Waray – not Bisayâ. Pre-1954, the latter designation would have been perfectly fine until, according to George Borrinaga’s analysis, things changed with the popularity of a film starring Nida Blanca called Waray-Waray (Borrinaga Citation2019, 178) The changing geo-political and cultural landscapes of the region have many acceding to the Visayan appellation only via locus nativitatis – which even then, is only as stable as rhizomatic inter-regional kinship through affinity, mass migrations (especially to Mindanao), and the next Republic Act from the Philippine government.

The Visayas as cultural text

It is within this mélange of contestations and disruptions that the organizers put together the conference titled Kaagi: Tracing Visayan Identities in Cultural Texts. Taking its cue from the Cebuano word for narrated history, and the Hiligaynon word ági meaning ‘traces of passing especially on water’ – ‘Kaagi’ looked into the ways in which texts, objects and performances negotiate, mediate and translate the slippery word ‘Bisaya’ into an identifier for collective evocations of regional culture, language and artistic practice from the Visayas. We specifically chose the term Kaagi as both a thematic placeholder and a point of intellectual origin, as the term evokes paths made legible on water as well as traces of identities, events and memories written in impermanence and time.

Professor Emeritus and Philippine national artist Resil Mojares introduced the conference (and this special issue), with an article on the Visayas as a field of academic research, as he painted a broad landscape, or rather seascape, of generative markers for collective Visayan identity and its future iterations. In this special issue, his piece is followed by another state of the field article by the grand dame of Visayan literature, Merlie M. Alunan, a multi-awarded poet, publisher and editor of three pioneering books on literature written in languages from the Visayas: Sa Atong Dila: An Introduction to Visayan Literature (Citation2015); Susumaton: Oral Narratives of Leyte (Citation2016), and Tinalunay Hinugpong nga Panurat ha Waray (Citation2017). Her personal narrative explores the marginal in Philippine literature and how she, as a writer of both Cebuano and English, has negotiated a space for a more vibrant inscription of Visayan literature and regional languages onto the national stage.

Patrick Flores, born in Iloilo and cognizant of its languages, and also a world-renowned curator and critic for South East Asian Art (he is currently the Deputy Director for Curation and Exhibitions at the National Gallery in Singapore), explores the current state of Philippine contemporary art coming from the Visayas. Flores does this by examining the exhibition component of VIVA ExCon 2020 (Visayas Islands Visual Arts) through a pan-Visayan word ‘kalibutan’. With cognates in Cebuano, Hiligaynon and Waray, the word simultaneously means both the world and consciousness, and becomes for Flores and the curatorial team at VIVA a vernacular that can be used as both method and theory, as it references ‘the tropic nature of curatorial work, an attentiveness to how materials, contexts and sensibilities transpose from condition to condition’ (Flores Citation2023).

These state of the field pieces on Visayan history, literature and art, are complemented by four research articles that amplify the three keynote calls for deep-diving into the study of the languages of the Visayan region and using them as anchors for ways of knowledge-making and exchange, as well as their calls for moving towards intersectionalities, interconnectedness, inter-regional and pan-regional area studies.

These trajectories are exemplified in Mary Dorothy Jose’s article (Citation2023), with its exploration of photographs of Visayan women ‘displayed’ at the 1904 St Louis World’s Fair. The article, which includes a good number of rarely published photos, highlights the significance of looking at social class, ethnicity and gender in enriching the analysis of how certain women were misrepresented within the context of the American civilizational index and its colonizing agenda. Voltaire Q. Oyzon’s ‘Winaray without Tears: Annotations on the Translations and Transcriptions of Bisayan Terms and Phrases in Alcina’s Historia (1668)’ (Citation2023), is a painstaking look at mistranslations/misapplications of Alcina’s works by various scholars through the years, including the much revered William Henry Scott. The article is a valuable example of how the sometimes mindless devaluation of local language and culture by translations and scholars, can be repaired by the acumen of a meticulous linguist who is also a first language speaker of a marginalized language.

‘The Anthropological Signification of the “Man with No Breath” in Visayas and Mindanao Epics’, by Myfel Paluga and Andrea Ragragio, elaborates on the socio-symbolic significations of breath and the absence of breath as an expression of indigenous reasoning and applies it to a broader South East Asian understanding of the soul. In ‘An Anthropological Rethinking of the Pintados and Early Tattooing in the Visayas, Central Philippines’, also by Ragragio and Paluga, the authors go beyond the portrayal of tattooing as the domain of warriorship and masculinity and widen the field of inquiry not only through other social practices, but also into local tattooing practices beyond the Visayan region.

Kaagi as both archive and memory

Carrying on with the twin purpose of these Conference special issues as both inscriptive and memory-making, I end this introduction with a brief description of the range, depth and groundedness of knowledge that was produced and exchanged at the event.

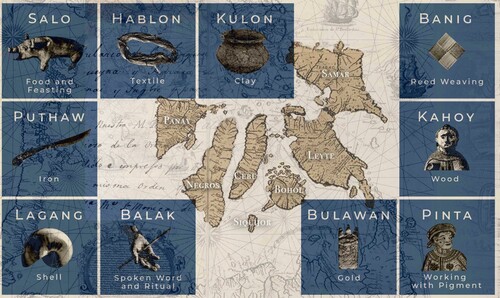

By virtue of its online format, we have been able to archive the programme and its full proceedings at the conference’s virtual room: https://kaagi.philippinestudies.uk/conference/. We have also been able to publish an interactive online exhibit (see ) that continued the trajectory of using Visayan vernaculars as intellectual starting points. The exhibit explores the connections between colonial archives and cultural practices from the Visayan region by drawing on sources dating up to the seventeenth century, most specially the dictionary Vocabulario de la lengua Bisaya, Hiligueyna y Haraia de la Isla de Panai y Sugbu, written by Alonso de Méntrida (1559–1637), an Augustinian friar who was appointed Prior to the island of Panay, from 1607 to 1611 (the rare manuscript is now kept at the SOAS Special Collections and Archives and has been fully digitized and made available at https://digital.soas.ac.uk/AA00001460/00001). The exhibit’s interactive portal features ten categories of early contact cultural artefacts and extends the exploration by accompanying these with works by contemporary Filipino artists who adapt, transform and subvert these representations in their practices. Zeroing in on pan-Visayan words for ten tangible and intangible material categories, namely, textile, wood, clay, iron, food, iron work, spoken word and ritual, shell, gold and pigment, each section of the exhibit begins with a brief examination of the history of the material, then lets contemporary practitioners from the Visayas present their work and describe how they have transformed the medium.

Figure 1. Curated by Dr Maria Cristina Martinez-Juan, this interactive online exhibit entitled KAAGI: Tracing Visayan Identities in Cultural Texts, co-hosted by the Brunei Gallery at SOAS and Philippine Studies at SOAS can be accessed at https://kaagi.philippinestudies.uk/exhibition/.

In the Kahoy (‘Wood’) section, Floy Quintos and Emil Marañon bring forward a set of Philippine Santos from around the region that are diverse in form, speaking from a deep knowledge and experience with the ways early sculptors used wood in these powerful ritual objects. Raymund Fernandez in his video Looking for Nick Salumer follows them as a contemporary artist whose practice branches out from painting to installation and performance, while finding its roots in his identity as a master carver from the Visayas.

The Hablon (‘Textile’) section features a beautiful film directed by Luna Mendoza and shot in Iloilo, that breaks down the long and complicated history of piña or pineapple silk fabric. This is followed by Norberto Roldan's video Incantations in the Land of Virgins, Monsters, Sorcerers and Angry Gods, which describes his use of the Patadyong tradition of Negros and how this underpins his philosophy of an art that speaks so eloquently against political violence.

The Balak, or ‘Spoken word and Ritual’, section needs a special mention as the deepest exploration of its topic in the exhibition. Dr. Josel B. Mansueto reaches back to the time of Pigafetta and Magellan before moving on to document some of the fascinating rituals performed by contemporary healers in Siquijor. Junel Tumaroy walks us through his evocative and enigmatic paintings and found relief pieces that deeply connect with his role as a healer. Adonis Dorado follows with a reading of his Cebuano poem, ‘Kabilin’, while visual artist Liby Limoso works with Leopoldo Caballero, a Sugidanun Epic chanter from Garangan Calinog, Iloilo, to record his performance of an excerpt from Tikong Kadlum (Black Dog), the first story in the epic series. Finally, the section ends with an exploration of ‘Unang Balak ni Antonio Pigafetta', a spoken-word installation by Roy Lu that works with the words recorded by Pigafetta on that first visit to the Visayas in 1521 and the list of words (and worlds) he created to categorize a people who would later be colonized under Spain for 300 years.

While some contributors to the exhibit, like Norberto Roldan and Marian Pastor Roces, are well known, some artists still fly very much under the radar, like Panday Mario, a virtuoso iron-smith working in Carigara, Leyte (in the ‘Puthaw' section) and Jacquelou Curambao–Aballe from Bohol (in the ‘Pigment’ section), and we are happy to have the privilege of including them in the exhibit. Curating the exhibition was very much a process of discovery, and video by video, slide by slide, the juxtaposition of history and contemporary practice created a rolling revelation of what it may mean to trace the contours of an amorphous Visayan collective identity. If the emergent themes of the vernacular as theory and method, localization and interconnectedness hold true, the Visayas then becomes a rich and multi-faceted place of meeting that can recast our current conceptions of authorship, originality, authenticity and, maybe most importantly, value.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alunan, Merlie M. 2015. Visayas: Sa Atong Dila: An Introduction to Visayan Literature. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- Alunan, Merlie M. 2016. Susumaton: Oral Narratives of Leyte. Manila: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Alunan, Merlie M. 2017. Tinalunay Hinugpong nga Panurat ha Waray. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- Baumgartner, Joseph. 1974. “The Bisaya of Borneo and the Philippines: A New Look at the Maragtas.” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 2 (3): 167–170.

- Borrinaga, George E. R. 2019. “Solidarity and Crisis-Derived Identities in Samar and Leyte, Philippines, 1565 to Present.” PhD Thesis, University of Hull. https://hull-repository.worktribe.com/output/4222102

- Flores, Partick. 2023. “In Terms of Kalibutan: Motes on Method via the Visayas.” South East Asia Research 31 (3).

- Jose, Mary Dorothy dL. 2023. “A Feminist Analysis of Colonial Representations of Visayan Women at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition.” South East Asia Research 31 (3): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0967828X.2023.2229488.

- Oyzon, Voltaire Q. 2023. “Winaray Without Tears: Annotations on the Translations and Transcriptions of Bisayan Terms and Phrases in Alcina’s Historia (1668).” South East Asia Research 31 (3): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0967828X.2023.2233897

- Paluga, Myfel D., and Andrea Malaya M. Ragragio. 2023. “The Anthropological Signification of the ‘Man with No Breath’ in Visayas and Mindanao Epics.” South East Asia Research 31 (3): 1–24. doi:10.1080/0967828X.2023.2234820

- Ragragio, Andrea Malaya M., and D. Paluga Myfel. 2023. “An Anthropological Rethinking of the Pintados and Early Tattooing in the Visayas, Central Philippines.” South East Asia Research 31 (3): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0967828X.2023.2233896