Each year, the number of people affected by humanitarian emergencies continues to increase, and the contexts become more complex, requiring thoughtful, intentional innovation and the creation of an evidence base that informs programme design, implementation and practice. In 2015, the numbers of people forcibly displaced from their homes hit a record high, with a 75% increase in two decades, rising from 37.3 million in 1996 to 65.3 million by the end of 2015.Citation1 This translates to 24 persons being displaced from their homes every minute of every day in 2015, as a result of persecution, conflict, generalised violence or human rights violations. This trend is expected to continue.Citation1 In addition, there were 19.2 million new displacements associated with natural disasters in 113 countries.Citation2

The right to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) is an indispensable part of the right to health and is dependent upon a number of factors that include availability and accessibility to quality evidence-based services. While entire populations benefit from access to SRH services and rights, women and adolescent girls face a host of particular vulnerabilities. It is estimated that around 26 million women and girls of reproductive age are living in emergency situations around the world and face increased threats to their sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), requiring access to quality services.Citation3

While services such as food aid, shelter, water and sanitation, security and basic health services are crucial in the early stages of a humanitarian crisis, the provision of reproductive health services has been recognised as an additional priority early in an emergency.Citation4,Citation5 Commendable progress has been made to make SRHR services available since the mid-90s, when a landmark report highlighted the lack of comprehensive SRH care among populations in crises.Citation6 This state of affairs triggered the 1995 formation of the Inter-agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises (IAWG), a network of organisations dedicated to addressing the gaps in the provision of SRH services to communities affected by conflict and disaster. For more than two decades, organisations and individuals affiliated to IAWG have made concerted efforts to advance reproductive health through advocacy, research, standard setting and guidance development.Citation5 To this end, major strides have been made, although much more remains to be done.

In 2008, Reproductive Health Matters (RHM) dedicated a journal issue to the theme of conflict and crises, a well-timed issue that shed light on the devastating implications of conflict and crises on women and girls, highlighted ongoing response efforts and identified the unmet SRHR needs of populations in these fragile settings. Nearly 10 years later, with record numbers of people facing crises and displacement, it is once again time to draw attention to advances made, share best practices and discuss challenges in service implementation in crises and protracted humanitarian settings. A global evaluation conducted from 2012 to 2014Citation5 revealed that while considerable advances have been made, some of the concerns raised and gaps identified in RHM’s 2008 issue still ring true today. Building on previous work, the articles published in this journal issue cover a range of complex and sensitive topics such as safe abortion care, gender-based violence, sexual violence against men and sex work among refugees. Studies also address quality improvement and training of health workers with the aim of improving practice and care for better maternal and newborn health outcomes.

Progress continued

Following the formation of IAWG in 1995, a need was identified for technical guidelines that would inform the implementation of SRH services in the field. Subsequently, in 1999, a ground-breaking authoritative guidance, Reproductive Health for Refugees: An Inter-agency Field Manual (IAFM), was published.Citation7 The IAFM outlines the SRH services to be provided during different phases of a humanitarian emergency. It was revised and released for field testing in 2010, however, input from field practitioners and various humanitarian actors on this revised IAFM necessitated yet another round of revisions, which will be published in 2018. Through a process of intersectoral collaboration, the latest revisions were intended to respond to the changing nature of the field in the past decade and incorporate the latest evidence in SRH practice. In this issue, Foster et al describe the current revisions on the IAFM. Most notable is the repositioning of unintended pregnancy prevention and the explicit incorporation of safe abortion care.

One of the chapters in the IAFM is on the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP), a set of SRH services to be implemented during the early phase of an emergency. To achieve effective implementation of the MISP, health providers and other stakeholders need not only to understand its objectives but also to create an environment that facilitates its implementation, ensuring availability of the necessary supplies for the lifesaving SRH activities. In their article, Krause et al look back at progress made and the successful efforts that have led to increased uptake and implementation of MISP in emergency settings. Early assessments of the MISP implementation in acute humanitarian settings generated mixed results, revealing low MISP awareness, inadequate SRH training among humanitarian actors, logistical difficulties and poor coordination.Citation8 Current reports show consistent availability and high awareness of MISP as a standard among responders, pointing to the success of this multi-stakeholder collaboration and the various initiatives put in place to address the shortfalls.

Topics of high concern

Abortion

The topic of abortion remains highly relevant in any context, but more so in humanitarian settings where access to safe abortion and post-abortion care (PAC) is ever more pressing.Citation9 The collapse of the health system in an emergency, for example, reduces access to contraceptives for women who wish to delay pregnancy. Access to safe abortion is even more relevant in such settings because conflict and displacement increase women’s vulnerabilities to sexual violence, including rape. Women who subsequently experience unwanted pregnancy may not be able to access safe abortion services, leading them to unsafe abortion with severe health consequences.Citation10 In crisis settings, comprehensive abortion care (both safe abortion and post-abortion care) needs to be prioritised to address the high maternal mortality and morbidity from complications of unsafe abortion. The United Nation’s Population Fund (UNFPA) estimates that 25–50% of maternal deaths in refugee settings are due to complications of unsafe abortion.Citation11 Despite this reality, access to abortion-related services is still neglected in humanitarian responses, partly due to its highly politicised nature as well as the health providers’ attitudes and misconceptions of the restrictiveness of national abortion laws. McGinn et al 2016 discuss four reasons typically given by humanitarian non-governmental organisation (NGOs) for the gaps in abortion services: the need is not recognised; abortion is considered too complicated to be provided in crises; donors do not fund abortion services and abortion is believed to be illegal.Citation9 It is obvious that more work is still needed to make safe abortion available in order to improve women’s health and save lives.

In this journal issue, three papers focus on provision of abortion care in crisis situations. In their paper, Radhakrishnan et al address legal and policy barriers to safe abortion care. They argue that abortion services fall within the scope of the protections granted under international humanitarian and human rights law, and thus, call for safe abortion to be offered within the category of protected and non-discriminatory medical care in humanitarian crises. Despite the existing unmet needs in safe abortion and post-abortion care in humanitarian settings, Chukwumalu et al build a case for the possibility of implementing comprehensive PAC services in politically unstable and culturally conservative settings like Puntland, Somalia. The authors assert that despite the fact that abortion and modern contraception are sensitive and stigmatised matters, there are approaches that can be utilised to increase uptake. Finally, Tousaw et al provide insights into the possibility of working within legal constraints to expand access to abortion care services among displaced populations in Chiang Mai, Thailand. The authors report on in-depth qualitative interviews conducted with women on their experiences with a Safe Abortion Referral Programme (SARP) meant to reduce barriers to safe and legal abortion care in Thailand. The positive experiences expressed by the Burmese women immigrants show that referral programmes for safe and legal abortion can be successful in settings with a large displaced and migrant population. The women particularly appreciated the friendly programme staff, accompaniment to the facility, interpretation at the facility, safety of services and the lack of any costs incurred by the women.

Gender-based violence

Sexual violence as a form of gender-based violence (GBV) has occurred through history and has long been associated with war and well documented in recent humanitarian settings. Some early documentation includes the targeted mass rapes and murders of women in Bangladesh’s Liberation War of 1971. In the 1990s, the world was treated to the horrors of systematic rape of women in the Balkans and during the Rwandan genocide. The current sexual abuses in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Syria provide further examples.Citation12–15 Sexual violence (SV) survivors experience negative physical, psychological and social outcomes that may last a lifetime. A literature review by Robbers and Morgan on prevention and response to SV among female refugees shows that placing a strong emphasis on programmes that engage and educate communities has the potential to target underlying causes of SV. The review suggests that SV interventions that engage community members in their design and delivery address harmful gender norms through education and advocacy, and facilitate strong cooperation between stakeholders could maximise the efficient use of limited resources. Of note is that strong evidence around what works in SV programmes is still scarce and the sensitive nature of the topic can be a contributing factor to the lack of evidence. Stark and Ager 2011Citation16 lamented the lack of strong methods to quantify the magnitude of GBV in emergency settings. A recent integrative review found that a range of GBV prevention activities recommended by the global humanitarian community are currently being applied in a variety of settings. However, evidence on the effectiveness of GBV prevention programmes, interventions and strategies, especially among refugee populations, is limited.Citation17

While Robbers and Morgan focused their review on sexual violence against women refugees, it is important to mention that sexual violence among men in conflict also merits attention. Although women are disproportionately affected by sexual violence, particularly during conflict, male survivors of sexual violence have much less access than females to reproductive health programmes and are generally ignored in gender-based violence discourse. Furthermore, humanitarian organisations that offer SRH services are often not equipped to address physical and psychological complications experienced by male survivors of sexual violence.Citation18 In their commentary in this issue, Chynoweth et al shed light on sexual violence against men in conflict and forced displacement, providing suggestions on how to improve services to and uptake by this overlooked population.

Another population that is particularly vulnerable to gender-based violence in crisis situations is people engaged in sex work. The phenomenon of sex work among refugees, including adult females and males as well as unaccompanied female and male minors, urgently needs to be addressed in humanitarian assistance. Refugees involved in sex work are for the most part invisible in humanitarian settings and are more vulnerable to GBV, especially if sex work is illegal in the host country. There are anecdotal reports of sex workers across many refugee settlements, from the camps for Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh to the streets of Athens. Survival sex and exploitation is noted, for example, due to inadequate access to basic essentials such as food and water.Citation19, Citation20 Rosenberg and Bakomeza have highlighted the need for programming around refugee sex workers. Presenting the results of a pilot project in Uganda, they show the feasibility of adapting existing rights-based and evidence-informed interventions with sex workers to humanitarian contexts. Their findings further demonstrate how taking a community empowerment approach can facilitate the refugees’ access to a range of critical information, services and support options – from information on how to use contraceptives and where to get referrals to friendly HIV testing and treatment, to peer counselling and protective peer networks.

Maternal and newborn health

The UNFPA estimates that the maternal mortality ratio in humanitarian crisis settings is nearly twice the global average ratio (417/100,000 live births in humanitarian settings compared to global levels of 216/100,000 live births). Countries in humanitarian crises represent 61 per cent of the total number of maternal deaths worldwide.Citation21 During the last two decades, maternal and newborn health (MNH) has seen relative progress in its integration into primary health services in humanitarian emergencies. MNH also recorded most appeals for funding with the largest proportion (56%) of all reproductive health components in humanitarian health appeals from 2009 to 2013, and was the most funded.Citation21 Providing quality maternal and newborn care is still challenging due to lack of qualified staff, training and support supervision. Hynes et al shared their work on an approach to improve maternal and neonatal care in North Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Using a longitudinal quasi-experimental design, they explored whether a participatory quality improvement (QI) intervention could be used in a protracted conflict setting to improve facility-based maternal and newborn care. The authors found quality improvements in the active management of the third stage of labour (AMTSL) and essential newborn care (ENC) after training of health providers.

Strengthening capacity

Further, three articles in this issue have addressed capacity building of health workers to improve care of maternal and newborn health. Sami et al discuss a training with the aim of changing attitudes and knowledge towards evidence-based newborn care practices among facility and community health workers in South Sudan. They demonstrate that such training is possible in conflict and post-conflict settings and has the potential to increase, in particular, community health workers’ knowledge on neonatal health. Tran et al have discussed a strategy of Sexual and Reproductive Health Clinical Outreach Refresher Training (S-CORT) that can be implemented early in a humanitarian response, for service providers operating in acute humanitarian settings and needing to rapidly refresh their knowledge and skills. The authors conducted interviews with participants who attended clinical management of sexual violence survivors (CMoSVS) and manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) training to solicit their views on S-CORT. The participants identified this approach as respectful to human rights and quality of care principals. Although this approach may not be conclusive at this time, S-CORT is a promising model of training in an acute phase of an emergency. Yalahow et al explored the possibility of offering reproductive health education to physicians, nurses and midwives in a post-conflict environment of Mogadishu, Somalia. At the time of their study, there was inconsistent reproductive health education. They suggest the development of creative strategies such as stakeholder engagement to improve the breadth and depth of evidence-based education.

Sexual and reproductive rights are human rights

Protecting the human rights of populations displaced by humanitarian crises, especially women and children, is essential and integral to any humanitarian response. One particular paper in this issue highlights the shortcomings of institutional efforts to recognise, respect and protect the sexual and reproductive rights of women and girls as fundamental human rights. In her paper, Laporta points specifically to the agreement between the European Union and Turkey in March 2016, which put economic, political and security interests centre stage, and was in violation of the human rights of refugees, including the sexual and reproductive rights of women. This agreement highlights the inadequacies of the institutions in European countries and the European Commission in fulfilling their human rights obligations towards the refugees during the recent dramatic exodus across the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe to find safety.Citation1 Laporta reports in this paper on the process and outcome of a complaint lodged with the European Ombudsman by the organisation, Women’s Link Worldwide, to demand accountability from the responsible institutions to protect women and children.

Natural disasters

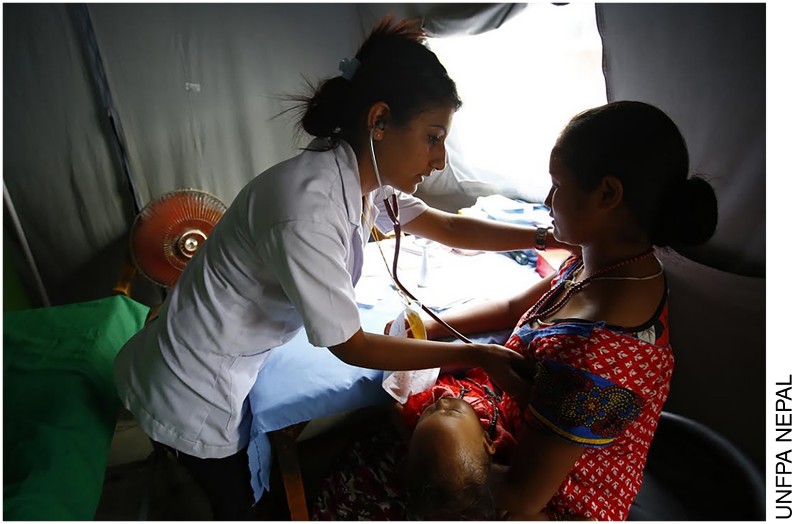

One of the notable gaps identified in this journal issue was the limited number of submissions on responses to natural disasters. The only, yet important, contribution in this area is by Chaudhary et al, who discuss the integration of sexual and reproductive health services in the humanitarian response to the Nepal 2015 earthquake. The devastating earthquake left 1.4 million women and adolescent girls in need of humanitarian assistance. The authors describe the response provided by the Ministry of Health of Nepal, with support from UN agencies and several other organisations, and outline 10 recommendations to be considered for future preparedness. They emphasise prioritising SRH needs in disaster preparedness plans for health. They argue that rosters for health workers trained in SRH services for emergencies need to be developed among other priorities.

More research is needed

As illustrated, this issue covers a range of topics in diverse settings from across the globe and contributes to the pool of evidence that guides practice. However, although the field has expanded, and programmes are addressing some of the delicate topics, more robust research is not only needed but urgently required to build evidence on how to offer critical, lifesaving sexual and reproductive health services in these unique settings. Most importantly, humanitarian practitioners, academics and donors need to find ways of identifying policy and legal barriers that undermine the sexual and reproductive rights of these populations and collectively strive to remove obstacles blocking the realisation of these fundamental human rights. Consultations on how best the humanitarian community can address the scarcity of robust research in such settings are necessary. While studies using a variety of methodologies such as mixed methods, descriptive, quasi-experimental designs and impact evaluations are valuable and needed, the limitations of these methodologies may restrict their applicability in a broader context. It goes without saying that conducting research in humanitarian settings is replete with challenges such as insecurity and instability, competing and conflicting priorities, and lack of funding. Nevertheless, it is worth recognising that without robust data, it will be difficult to innovate and accelerate efforts to meet SRHR.

RHM remains committed to offering an avenue for publication of emerging evidence in the field and welcomes continued submission on this topic.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our heartfelt thanks to the Editorial Committee of this issue, who provided much appreciated support throughout the process. Editorial Committee members include: Ian Askew, Hyam Bashour, Karl Blanchet, Sarah Chynoweth, Sandra Krause, Therese McGinn and Anthony Zwi. We are also immensely grateful to all the reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive reviews. Special thanks to the RHM editorial team, Sarah Pugh for coordinating and leading the editorial process of this issue, Pathika Martin, for her invaluable support throughout the entire process, in particular the coordination of the copy editing and production phase, and Maria Halkias, for her support on cover design, promotion and dissemination in preparation of this issue as well as upon its publication. Lastly, we would like to acknowledge the Dutch Government for their generous financial contribution towards this issue.

Antenatal care at a temporary birthing centre following the 2015 earthquake in Nepal

Antenatal care at a temporary birthing centre following the 2015 earthquake in Nepal

References

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Global trends forced displacement in 2015. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR); 2016. Read: Section I – Introduction; Section II – Refugee Population. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/statistics/unhcrstats/576408cd7/unhcr-global-trends-2015.html

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Center. Global report on internal 2016 displacement. 2016. http://www.internal-displacement.org/assets/publications/2016/2016-global-report-internal-displacement-IDMC.pdf

- UNFPA. UNFPA state of the world population 2015. Chapters 1 & 2; 2015. p. 15–57. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/sowp/downloads/State_of_World_Population_2015_EN.pdf

- Austin J, Guy S, Lee-Jones L, et al. Reproductive health: A right for refugees and internally displaced persons. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16(31):10–21. Available from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0968808008313512# doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31351-2

- Chynoweth, SK. Advancing reproductive health on the humanitarian agenda : the 2012–2014 global review. Confl Health. 2015;9(Suppl. 1):I1. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-I1. Available from: https://conflictandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-I1

- Wulf D. 1994 Refugee women and reproductive health care: reassessing priorities: results of year-long study of availability and feasibility of reproductive health services for refugee women in eight countries. Women’s Refugee Commission. Available from: file:///C:/Users/monic/Downloads/Reassessing_Priorities_-_1994_BW_scan.pdf

- Inter-agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in crises: reproductive health for refugees: An inter-agency field manual. Geneva; 1999.

- Onyango MA, Hixson BL, McNally S. Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for reproductive health during emergencies: time for a new paradigm? Glob Public Health. 2013;8:342–356. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23394618. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2013.765024

- UNFPA. State of the world population 1999. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/swp_1999_eng.pdf

- McGinn T. Reproductive health of war-affected populations: what do we know? Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2000;26:174–180. doi: 10.2307/2648255

- McGinn T, Casey, S. Why don’t humanitarian organizations provide safe abortion services? Confl Health. 2016;10:8. doi: 10.1186/s13031-016-0075-8

- D’Costa B, Hossain S. Redress for sexual violence before the international crimes tribunal in Bangladesh: lessons from history, and hopes for the future. Crim Law Forum. 2010;21:331–359. doi: 10.1007/s10609-010-9120-2

- Sharlach L. Rape as genocide: Bangladesh, the Former Yugoslavia, and Rwanda. New Polit Sci. 2000;22:89–102. doi: 10.1080/713687893

- Hossain M, Zimmerman C, Watts C. Preventing violence against women and girls in conflict. Lancet. 2014;383(9934):2021–2022. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60964-8

- Olujic MB. Embodiment of terror: gendered violence in peacetime and wartime in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Med Anthropol Q. 1998;12(1):31–50. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1525/maq.1998.12.1.31/pdf doi: 10.1525/maq.1998.12.1.31

- Stark L, Ager A. A systematic review of prevalence studies of gender-based violence in complex emergencies. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2011;12(3):127–134. doi: 10.1177/1524838011404252

- Tappis H, Freeman J, Glass N, et al. Effectiveness of interventions, programs and strategies for gender-based violence prevention in refugee populations: an integrative review. PLoS Curr Disasters. 2016. doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.3a465b66f9327676d61eb8120eaa5499

- Onyango MA, Hampanda K. Social constructions of masculinity and male survivors of wartime sexual violence: an analytical review. Int J Sex Health. 2011;23:237–247. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2011.608415

- Glinski S. Clandestine sex industry booms in Rohingya refugee camps. [updated 2017 Oct 23; cited 2017 Nov 23]. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bangladesh-rohingya-sexworkers/clandestine-sex-industry-booms-in-rohingya-refugee-camps-idUSKBN1CS2WF

- Damon A, Arvanitidis B, Nagel C. The teenage refugees selling sex on Athens streets. CNN. [updated 2017 Mar 14; cited 2017 Nov 23]. Available from: http://www.cnn.com/2016/11/29/europe/refugees-prostitution-teenagers-athens-greece/index.html

- UNFPA. Maternal mortality in humanitarian crises and in Fragile settings. November UNFPA 2015. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/MMR_in_humanitarian_settings-final4_0.pdf

- Tanabe M, Schaus K, Tastogi S, et al. Tracking humanitarian funding for reproductive health: a systematic analysis of health and protection proposals from 2002–2013. Confl Health. 2015;9(Suppl. 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-S2