Abstract

This article researches the instrument of peer review among states, which is widely used by international organizations to monitor state compliance with international anticorruption norms. Despite their widespread use, little is known about the conditions under which peer reviews bear significance in the global fight against corruption. This article seeks to shed light on this by considering the authority that three major, yet hitherto understudied, peer reviews carry: the OECD Working Group on Bribery, the Council of Europe’s Group of States against Corruption, and the Implementation Review Mechanism of the UN Convention against Corruption. Authority is conceptualized as a social relation between the institution carrying authority (the peer review) and the intended audience (mostly states). Drawing upon original survey data and expert interviews, the findings reveal that the three peer reviews have different degrees of authority. The article subsequently explains the observed variation in authority, by looking at the membership sizes and compositions of the peer reviews, their institutional designs, and the types of officials that are involved in the review process.

1. Introduction

Peer reviews among states are the most commonly used monitoring instrument in the international anticorruption regime. Pioneered by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in the 1990s, today the Council of Europe, the United Nations (UN) and the Organization of American States use peer review to monitor compliance with their anticorruption conventions. Peer review is a system of reciprocal, intergovernmental evaluations in which states’ policy performance is periodically assessed by experts from other states (the peers) (Pagani, Citation2002). These experts identify policy shortcomings, write a report, and make recommendations for improvement. Though peer reviews are often used to monitor states’ compliance with hard law obligations, such as international conventions, they lack sanctioning tools. Thus, they cannot force states to heed their recommendations but instead seek to advance policy reform by stimulating policy learning, by providing technical assistance, and by organizing peer and public pressure.

Despite some skepticism about the capacity of peer reviews to generate these outcomes (Schäfer, Citation2004, Citation2006), several studies show that peer reviews can have effects in states. Some peer reviews have featured in parliamentary debates (De Ruiter, Citation2010), have had framing effects on domestic policies (López-Santana, Citation2006), and have instigated peer and public pressure on governments (De Ruiter, Citation2013; Meyer, Citation2004). Not all peer reviews, however, seem equally successful in this regard. In the global anticorruption regime, the OECD Working Group on Bribery (WGB) is hailed by Transparency International as ‘the gold standard in monitoring’1 and is credited for mobilizing the necessary support for the United Kingdom’s Bribery Act (Pieth, Citation2013). The Implementation Review Mechanism (IRM) of the UN Convention against Corruption, in turn, is claimed to be ‘urgently needing improvement’2 and has been criticized for signaling various weaknesses (Rose, Citation2015, p. 106). If all peer reviews are soft-governance mechanisms, then why do some of them seem to matter more than others?

This article seeks to shed light on this by considering the authority peer reviews carry. Authority is understood as a mode of social control that is rooted in the collective recognition of an actor’s or institution’s legitimacy (Cronin & Hurd, Citation2008a; Hurd, Citation1999). This means that authority does not inhere in an actor’s or institution’s ability to force subordinates into compliance with their commands, but rests on the shared recognition that deference to an authority is the right and appropriate thing to do. Considering the importance that constructivist scholarship adheres to authority and legitimacy for state compliance with international norms and rules (Checkel, Citation2001; Hurd, Citation1999), authority offers a particularly useful lens to study peer reviews.

How much authority do different peer reviews in the field of anticorruption have? And how can we explain possible variation in the authority of peer reviews? This article aims to answer these questions.3 To this end, it compares three anticorruption peer reviews: the OECD’s Working Group on Bribery (WGB), the Council of Europe’s Group of States against Corruption (GRECO), and the UN’s IRM. These three peer reviews monitor state compliance with a combination of legally binding and nonbinding anticorruption norms and cannot sanction states. They are, however, set apart on several dimensions that potentially affect their authority: Their membership sizes and compositions, their institutional designs, and the officials they involve in the review process.

Although many scholars engage with the question of authority and legitimacy beyond the state (whether held by intergovernmental organizations, private actors, or civil society) (Cronin & Hurd, Citation2008b; Cutler, Citation1999; Hall & Biersteker, Citation2002; Hansen & Salskov-Iversen, Citation2008; Lake, Citation2010; Zürn, Binder, & Ecker-Ehrhardt, Citation2012), thus far few systematic empirical assessments of the authority of multilateral and global governance institutions have been conducted. Existing studies are limited in number and often draw upon an understanding of authority as formal-legal or delegated authority (e.g. Hooghe & Marks, Citation2015; Voeten, Citation2008).4 Such a delegated understanding of authority (Barnett & Finnemore, Citation2004, p. 22) is useful for studying the authority of IO bureaucracies but fails to capture differences in the authority of soft-governance instruments, which by definition have been transferred limited formal competences. This study adds to this research, using an original dataset of responses to a survey on the relational authority of peer reviews. In addition, it offers one of the first fine-grained analyses of the institutional and organizational-level characteristics that affect the development of relational authority in global governance. An important body of literature deals with the question of what drives citizens’ support for international organizations (e.g. Dellmuth & Tallberg, Citation2015; Edwards, Citation2009; Johnson, Citation2011). Yet, little is known about how international policy instruments compare in their authority, let alone how possible variation in their authority can be explained. Finally, this article advances understanding of the design and functioning of three major, yet hitherto understudied, peer reviews. Such insights are not only relevant to international political economy scholars for their empirical focus on anticorruption and antibribery. This study uncovers the factors that affect the authority of a governance instrument that is widely used to deal with the challenges facing the global political economy. Consider, for instance, the Trade Policy Review Mechanism of the World Trade Organization and the OECD’s Economic and Development Review Committee, which are both peer reviews.

The next section introduces the concept of authority as a social relation. After providing some background information (Section 3), Section 4 explains how relational authority can be studied empirically and introduces the study’s data sources and methods: 45 interviews with officials who are directly involved in the peer reviews such as IO Secretariat staff members, diplomats, and national anticorruption experts, and an online survey targeting the same type – though a much larger number – of officials as for the interviews. Section 5 compares the authority of the three peer reviews. The findings reveal that the GRECO is accorded more authority than the WGB and the IRM. These differences would not have been identified had a more traditional approach to authority been taken. Section 6 then explains the observed variation in authority. The main argument is that the number and composition of states that participate in the peer reviews, the institutional designs of the peer reviews, and the types of officials that are involved in the review process, explain differences in the peer reviews’ authority. Section 7 concludes and discusses the broader implications of the findings for studying authority in global governance.

2. Authority in global governance

2.1. Relational authority

In the age of globalization, states are decreasingly able to deal with certain governance problems on their own (Grande & Pauly, Citation2005). Authority is relocated from states to transnational, subnational, nonstate, and private actors, which may be better adept at addressing these issues than states (Bernstein, Citation2011; Cutler, Haufler, & Porter, Citation1999; Hall & Biersteker, Citation2002; Hansen & Salskov-Iversen, Citation2008; Scholte, Citation2011). In addition, IOs and their bureaucracies are seen to possess some degree of autonomy and authority in their actions (Barnett & Finnemore, Citation2004; Bauer & Ege, Citation2016; Busch & Liese, Citation2017; Zürn et al., Citation2012). The anticorruption regime is a good example of these trends. Though states continue to be the prime addresses of most anticorruption conventions, a range of international and nonstate actors play an important role in the formation and enforcement of the anticorruption regime, such as the nongovernmental organization (NGO) Transparency International (Gutterman, Citation2014; Wang & Rosenau, Citation2001) and the private sector (Hansen, Citation2011).

Despite growing recognition that international, nonstate and private actors have some authority in global affairs, a lot remains unknown. What type of authority do these actors carry and why do some of them seem more authoritative than others? Evidently, the authority of nonstate actors and international institutions is different from the formal or legal authority of states. Furthermore, an understanding of authority as ‘delegated authority’, that is the transfer of decision-making powers to IOs (Barnett & Finnemore, Citation2004, p. 22), is inapplicable to the host of soft-governance instruments that have not been delegated any decision-making powers or that exhibit minimal variation in this regard. This article therefore engages with a different type of authority: Authority as a social relation (Barnett & Finnemore, Citation2004; Cronin & Hurd, Citation2008a; Hurd, Citation1999; Lake, Citation2009, Citation2010).

In a relational understanding, authority is a mode of social control that is rooted in the collective recognition of an actor’s or institution’s legitimacy (Cronin & Hurd, Citation2008a; Hurd, Citation1999). Authority does not inhere in formal-legal competences, but rests on the shared belief that deference to an authority is the right and appropriate thing to do. It therefore only exists to the extent that it is collectively recognized to exist. A relational understanding of authority squares well with this article’s aim of studying the authority of international policy instruments that seem to have some authority in global governance which cannot be captured by a formal-legalistic or delegated understanding of the concept. The larger social group of the peers bestows authority on a peer review (based on their perceptions that the instrument is appropriate), not formal rules and laws. Consequently, a peer review might be an authoritative instrument in the eyes of some individuals, but much less so for others. The degree of authority then hinges on the strength of the legitimacy perceptions held by varying shares of the intended audience.

Relational authority offers a particularly relevant lens for studying the significance of peer reviews, which seek to inform public policy-making in two main ways. The first is through persuasive processes of peer and public pressure (Guilmette, Citation2004; Meyer, Citation2004; Pagani, Citation2002). If states are found to be incompliant with international norms, this behavior is exposed to the peers and the public. The ensuing reputational costs of such exposure might motivate national administrations to implement policy reform. The second way in which peer reviews seek to inform policy-making processes is by stimulating learning among administrative élites (Lehtonen, Citation2005; Radaelli, Citation2008, Citation2009). Peer review offers unique opportunities for bureaucrats to meet colleagues from abroad, to exchange experiences, and to broaden understanding of the policy problem at hand. National policy-makers may not just learn from the output produced (i.e. the findings of the evaluation exercise) but possibly even more so from their participation in the review, for instance, by acting as an evaluator or attending plenary sessions. What matters then is not the direct use of the outcome of peer reviews (as is the aim of exerting peer and public pressure) but the indirect ways in which peer reviews shape public policy-making by enlightening policy-makers (Lehtonen, Citation2005, p. 170).

Irrespective of whether we look at peer reviews as compliance or learning-oriented exercises, authority seems highly relevant for the successful execution of the abovementioned processes. Absent such authority, it is unlikely that national administrations would take advice from their peers, surrender their own judgment on their policy approach, and reconsider their policies. To the extent that peer reviews carry authority, it is therefore important to investigate why some of them are more authoritative than others. That said, in its focus on authority, this study neither assesses state compliance with a peer review’s recommendations nor researches a peer review’s effectiveness in eradicating corruption on the ground. Hence, this article should be understood as an important – though first – step in assessing the importance of peer reviews in global governance.

2.2. Under what conditions do peer reviews carry authority?

As argued above, a relational approach is useful for studying the authority of peer reviews. The literature on relational authority remains, however, silent on the factors that foster authority. Consulting the literatures on socialization, institutionalism, and peer reviews, three factors possibly explain variation in authority: A peer review’s membership size and composition, its institutional design, and the types of officials that are involved in the peer review.

First, a peer review’s membership size and composition can be global (in the UN), (sub)regional (e.g. the GRECO), or defined by the level of socio-economic development of its members (the OECD). The literature on peer reviews underscores the importance of value‐sharing, like-mindedness, and mutual trust among the officials involved in a peer review (Pagani, Citation2002; Thygesen, Citation2008). Peer review might be a rather intrusive process; states open their doors to colleagues from abroad, disclose (potentially sensitive) information, and allow them to assess their performance. For officials to unquestioningly give up private judgment and defer to an authority’s commands, some degree of trust in the relationship seems necessary. It seems plausible that some peer review contexts are more conducive to developing an atmosphere of like‐mindedness and trust than others. The socialization literature maintains in this regard that social interactions in IOs can have reorienting effects on the identities and interests of the officials involved (Checkel, Citation2001; Johnston, Citation2001). Through their participation in a peer review, officials’ views may converge on what is legitimate behavior and new norms may be internalized. Such socialization and learning processes may be more likely to occur in peer reviews with small and homogeneous memberships, consequently, fostering trust and like‐mindedness among delegates. This, in turn, is expected to strengthen the authority of peer reviews.

Second, peer reviews exist in different forms. Once peer review is chosen as a monitoring instrument, decision makers face many questions. Should the mechanism be consensus-based? How transparent and inclusive should the mechanism be toward NGOs? And which sources of information may be consulted for the evaluations? Decision makers negotiate, or even fight, over institutional design because these decisions have consequences (Koremenos, Lipson, & Snidal, Citation2001). Institutional design therefore seems a potentially relevant factor in explaining authority. It is, however, unclear how institutional design links to authority and which specific factors possibly enhance or weaken it. These are therefore treated as empirical questions, explored through an inductive research design.

The third factor concerns the officials that are involved in a peer review. Some peer reviews mostly involve substantive experts on the topic of anticorruption, whereas others bring in a combination of substantive experts and permanent delegates. Substantive experts are usually prosecutors, judges, and bureaucrats who act as delegates to the plenary sessions and conduct the evaluations. The permanent delegates, mostly career diplomats, bring in knowledge about the instrument of peer review, the procedures related to it, and international negotiations. Though most reviews are carried out by substantive experts, the share of diplomats attending plenary sessions is comparably higher in the IRM than in the WGB and the GRECO. The presence of diplomats at plenary sessions is expected to negatively influence a peer review’s authority in two ways. First, peer reviews that involve diplomats may be more politicized than peer reviews that only involve substantive experts. Politicization is frequently discussed in relation to the protection and pursuit of state interests, political bias, and unequal treatment (Donnelly, Citation1981; Freedman, Citation2011), which can be expected to negatively affect (what is supposed to be) a technical and objective peer review. Substantive expertise, in contrast, might invoke the impression of ‘depoliticization’ and ‘objective’ knowledge, and as such enhance authority (Barnett & Finnemore, Citation2004, p. 24). Second, peer reviews that mainly involve substantive experts constitute a more homogenous group of officials. As mentioned before, homogeneity might be conducive to socialization processes, which can relate to the type of states involved but also to the type of delegates sent. The likelihood of views to converge may be higher among officials with a similar professional background.

3. Peer reviews in the international anticorruption regime

Peer reviews are a popular monitoring instrument in the international anticorruption regime. Next to the three mechanisms studied here, the Organization of American States, the African Union, and the OECD at the sub-regional level (i.e. the Istanbul Action Plan against Corruption) use peer reviews. As shown below, the WGB, GRECO, and IRM are chosen as case studies, as they exhibit interesting differences in their memberships, their institutional designs, and the officials that are involved in the peer reviews ().

Table 1. The main features of the peer reviews.

3.1. The WGB

The WGB, which has been in operation since 1999, monitors the implementation and enforcement of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention and the Anti-Bribery Recommendation in 43 states.5 Its membership comprises all OECD member states and several non-OECD states that are key players in international trade. The WGB consists of representatives from all States Parties, most of which are substantive experts on corruption, such as law enforcement experts and tax experts. Diplomats are only involved to a limited extent.

The monitoring process of the WGB is intergovernmental, which means that civil society and the private sector are formally not involved in the evaluation process. However, informally, they are consulted during the on-site visits. Monitoring is divided into several phases, each of which focuses on a different step toward implementation and enforcement of the Convention. Typically, the reviews consist of a combination of self- and mutual-evaluations in the form of questionnaires and, from Phase 2 onwards, an on-site visit of about a week.

After the evaluation is completed and a draft evaluation report is formulated, the report is discussed in the WGB plenary. Meetings are held behind closed doors in order to stimulate a free and frank exchange of views and facilitate peer pressure (Bonucci, Citation2014). During these meetings, the report can be modified and is adopted by means of the consensus minus one principle, meaning that the state under review is exempted from voting. All country evaluation reports, which include recommendations for improvement, are subsequently published online.

The review process does not end with the publication of the reports. All countries are subjected to intensive follow-up monitoring to assess whether they have implemented the recommendations from previous phases. Only after their performance is considered satisfactory, meaning that they have sufficiently addressed the review recommendations, can countries move on to the next review phase. In case of continued noncompliance or if states reverse their legislation after the review, the WGB can decide that states need to redo an evaluation round (Bonucci, Citation2014).

3.2. The GRECO

The GRECO, which consists of the 47 Council of Europe member states, Belarus and the United States, has been reviewing states’ compliance with a range of legally binding and nonbinding anticorruption instruments since 2000. The GRECO plenary meets on average four times a year in Strasbourg and mostly consists of substantive anticorruption experts. Like in the WGB, diplomats are only marginally involved.

In terms of institutional design, the GRECO evaluations consist of self-assessment checklists, a desk review by the reviewing team, and a country visit that gives other stakeholders the opportunity to express their views.6 Once a country evaluation report has been drafted, the report is discussed and ultimately adopted by the GRECO plenary, with the reviewed state exempted from voting. Like the WGB, these meetings are held behind closed doors. Country evaluation reports, once they have been adopted, are not automatically published online. This only happens after the reviewed state has given its consent to do so. The GRECO may, however, decide to make the executive summary publicly available.

Contrary to the WGB, the GRECO reviews are organized thematically: Each evaluation round focuses on a different theme. States can only move on to the next review round once their performance is deemed (globally) satisfactory under the previous round. Follow-up monitoring is also organized slightly differently. The GRECO monitors member state implementation of review recommendations under the so-called compliance round, which requires states to regularly report on the progress they have made. In case of continued noncompliance with review recommendations, the noncompliance procedure is launched, which adds further pressure on states to comply.

3.3. The IRM

Finally, the IRM has been in operation since 2010 and is presently reviewing the performance of 183 states. Compared to the WGB and GRECO, it involves a larger share of diplomats in the review process. The country reviews are, however, carried out by substantive experts.

As to its institutional design, the IRM borrows several features from the other reviews, such as the combination of self-assessment checklists and country visits.7 The degree of obligation is, however, lower: Country visits are optional, the reviewed state is responsible for providing information and decides on whether – and which – nonstate actors may be consulted in the review process. Moreover, the review report reflects the consensual outcome of the reviewing team and the reviewed state, which means that in principle the reviewed state can block the adoption of the report. Like the GRECO, country reports are not automatically made publicly available, apart from the executive summaries.

Another difference with the other mechanisms concerns the meetings of the Implementation Review Group. This is an intergovernmental group of all states parties to the convention, which oversees the operation and performance of the peer review. Meetings take place in a closed setting but, in contrast to the WGB and GRECO, the group does not discuss individual country evaluation reports, let alone modifies or adopts these collectively. Thus, the information exchange among states is limited to a discussion of thematic reports and more general experiences with the peer review.

4. Studying the authority of peer reviews

To study the authority of the WGB, GRECO and IRM, the following definition of authority is used:

An institution acquires authority when its power is believed to be legitimate. Authority requires legitimacy and is therefore a product of the shared beliefs about the appropriateness of the organisation’s proceduralism, mission and capabilities (Cronin & Hurd, Citation2008a, p. 12).

Of particular interest, therefore, are perceptions of: (1) the appropriateness of a peer review’s purpose (i.e. its mission), (2) the correct application of procedures, notably the absence of political bias and the uniform application of rules (i.e. its proceduralism) and (3) a peer review’s ability to deliver meaningful outcomes (i.e. its capabilities). To this end, a methodological framework of relational authority is applied that is discussed more extensively in the author’s previous work (Carraro & Jongen, Citation2018; Conzelmann & Jongen, Citation2014), and which is summarized in . The different dimensions and subdimensions of authority reported in this table are informed by an exploratory study (Conzelmann & Jongen, Citation2014) an analysis of the mission statements of the three peer reviews, and the existing literature on peer reviews (i.e. Bossong, Citation2012; Lehtonen, Citation2005; Pagani, Citation2002; Radaelli, Citation2008).

Table 2. Operationalizing authority.

The relevant audience for this study are the officials and delegates who are directly involved in the peer reviews, such as IO Secretariat members, national anticorruption experts who have acted as delegates or evaluators, and diplomats. External actors (e.g. business or civil society) are excluded as they are often insufficiently familiar with the peer reviews to assess their procedural integrity, capacities, and purpose in sufficient detail. Moreover, in contrast to external nonstate actors, the national anticorruption experts who are directly involved in the peer review are usually also responsible for implementing policy recommendations.

To compare and explain the authority of peer reviews, a mixed-methods approach is taken. The quantitative data consist of an original online survey, which was implemented between July 2015 and December 2015. The survey, which was fully anonymous to disincentivise respondents to give socially desirable answers, studies perceptions of the mission, proceduralism, and capabilities of the peer reviews. Statistical analyses (One-Way Analyses of Variance; LSD post-hoc test) are applied to compare the mean scores of the peer reviews on the various dimensions of authority and to identify statistically significant variation among them.

The analyses draw upon the data collected from 272 respondents out of 558 sampled officials,8 marking a response rate of 48.8%.9 For the WGB and the GRECO, the survey was distributed among all the substantive experts and IO Secretariat members who were involved in the peer reviews between January 2014 and June 2015 and for whom contact information could be retrieved. For the IRM, the survey was sent out to all UN Secretariat members involved in the IRM, one substantive expert per State Party, and one diplomat per State Party with diplomatic representation in Vienna, and for whom contact information could be retrieved.10 As the sample of IRM respondents is not representative of the total population,11 several weighting adjustments were made for the IRM to correct this imbalance.12 The analyses were also conducted without weighting.

Next to the survey, 45 semi-structured interviews were conducted with Secretariat members, diplomats, and national civil servants. To compare the authority of peer reviews, the interviews were used to contextualize the survey findings and to elicit meaning from them. To explain variation in authority, interviews served to test the relevance of three explanatory factors (membership size and composition, institutional design, and the types of officials involved) and to explore other possible explanations.

5. The authority of peer reviews

Applying the measures of authority developed earlier, how do the WGB, the GRECO, and the IRM fare in terms of their mission, proceduralism, and capabilities?13

5.1. Mission

The mission dimension concerns the appropriateness of the purpose of a peer review, of the IO that organizes it, and of the assessment standards that are used in the evaluations. shows that peer review is in principle appreciated as a monitoring tool in the anticorruption regime: M = 3.46 (WGB), M = 3.34 (GRECO), and M = 3.35 (IRM; 1–4 scale). Compared to expert reviews, peer reviews actively involve national administrations in the review process, giving bureaucrats from different member states the opportunity to meet, exchange views, and learn from each other’s experiences (interviews 16, 18, 21, 22, 30, 41). The entire review process is a learning experience, not just the output (i.e. the report) that the country evaluation produces. Another advantage compared to independent reviews is that governmental experts may be more mindful of the national context in which policy reform needs to be implemented, as they deal with similar policy problems in their home countries (interviews 8, 21).

Table 3. Mission.

Although the surveyed officials hardly questioned the use of peer review as such, interviews shed light on the subtler differences in their assessment of the peer reviews’ missions. Notably, whereas in the WGB and the GRECO most delegates agree on the broader aims these peer reviews serve, views diverge on the IRM’s purpose. Several Western European delegates see peer review as a compliance-oriented endeavor, which warrants the use of peer and public pressure (interviews 20, 22, 27, 45). In contrast, several delegates from other regional groups see peer review predominantly as a nonintrusive exercise that is aimed at promoting mutual learning (interviews 11, 19, 28). There is no place for peer and public pressure in such a constructive mechanism. Both perspectives appear irreconcilable, translating into different views of what the IRM should do and how it should be designed to do this. This has led to dissatisfaction among predominantly Western European delegates, who feel they have pulled the short end of the stick. Interestingly, this dichotomy in perspectives of a peer review’s mission differs from other accounts in the literature which hold that both aims can be integrated in the framework of a single peer review (Lehtonen, Citation2005). Likewise, the WGB and the GRECO are seen as both compliance and learning exercises.

The second subdimension of mission, the appropriateness of the IO hosting the peer review, is rather uncontroversial. The OECD, Council of Europe and the UN are commonly perceived as appropriate fora: M = 3.39 (WGB), M = 3.41 (GRECO), M = 3.48 (IRM; 1–4 scale). The OECD, which is composed of many of the main exporting nations, is well-placed to monitor states’ performance in the criminalization of foreign bribery. Moreover, both the OECD, which is traditionally seen as a technical expert body, and the Council of Europe are appreciated for their expertise. The UN, in turn, is often considered the only organization with the legitimacy and resources available to carry out a peer review on a global scale.

Finally, based on the survey findings, the peer reviews exhibit limited differences in the appropriateness of their assessment standards: M = 3.15 (WGB), M = 3.20 (GRECO), and M = 3.22 (IRM: 1–4 scale). Such standards can be formally institutionalized from the start or can gradually develop in the process of peer reviewing. The high levels of appropriateness reported in the survey are surprising considering the variation in legal and nonlegal instruments under review and some of the critique raised in interviews. Interviewed delegates particularly criticized the GRECO’s assessment standards of the fourth evaluation round, which deals with nonbinding legislation (interviews 32, 33, 35, 39). Delegates reportedly disagree about what constitutes good performance and compliance under this review theme (interviews 22, 32, 33, 35).14 Furthermore, interviewees found the standards of assessment in the GRECO vaguer, leading to longer discussions over what the minimum standards and expectations are. This finding corroborates Pagani’s (Citation2002) argument about the importance of unambiguous assessment standards and criteria in conducting a peer review (see also: Porter & Webb, Citation2007).

5.2. Proceduralism

The proceduralism dimension relates to the extent to which political bias is absent in the review process and to which states are treated uniformly. shows that the GRECO is perceived as comparably less politically biased (M = 2.97) than the IRM (M = 2.60; p ≤ .01) and the WGB (M = 2.44; p ≤ .001; 1–4 scale). The effect size is medium (an eta squared value of 0.06). In the WGB, historical, diplomatic, and trade relations between countries reportedly come to the fore in discussions. Mutually sympathetic states stand up for each other to prevent one another from receiving recommendations that are difficult to implement. Likewise, neighboring countries or states with a similar legal system are at times perceived to be more lenient toward each other (interviews 8, 40, 41, 42, 44), with several delegates admitting to do so themselves (anonymous interviews). This situation is not unique to the WGB but also happens in the GRECO (interviews 22, 31, 34, 35) and other peer reviews, such as the Universal Periodic Review on Human Rights (Carraro, Citation2017). The plenary can partly offset such politically-motivated behavior, as delegates that themselves received certain recommendations may be particularly adamant on making sure that other states do not get away with fewer or less far-reaching recommendations than they did (interviews 33, 41). Finally, and surprisingly perhaps, many interviewed officials reported that the IRM reviews are very technical and not politically biased; it is a legal compliance exercise (interviews 20, 24, 29, 45). Back‐scratching or behind‐the‐scenes trade‐offs are seemingly absent. Plenary sessions are, however, more often perceived as politicized (interviews 20, 27, 41, 45).

Table 4. Proceduralism.

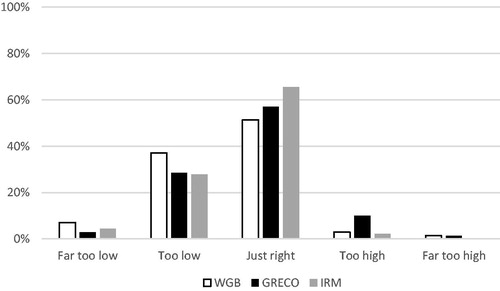

Less variation can be found when it comes to perceptions of uniform rule application: M = 2.61 (IRM), M = 2.53 (GRECO), M = 2.43 (WGB; 1–3 scale). As mean values do not indicate whether uniformity in the application of standards is perceived as too low or too high, a bar chart is created to display the distribution of responses (). Even though a majority perceives this to be just right, a significant share considers this to be too low, particularly in the WGB. Importantly, these scores do not report on absolute differences in uniform rule application between the mechanisms. What this analysis does reveal is that the extent to which context‐specific expectations of uniform treatment are satisfied is somewhat lower in the WGB than in the IRM and GRECO. Interviews, for instance, revealed that the GRECO has pursued an approach of assessing each country on its own merits from the Fourth Evaluation Round onward (interviews 22, 32, 33, 37, 39). The extent to which standards of assessment are applied uniformly was overall assessed positively, although the GRECO has comparably the largest share of respondents that consider the degree to which this is done too high.

5.3. Capabilities

The capabilities of a peer review relate to its ability to deliver meaningful outcomes. As mentioned before, this study does not investigate whether the three peer reviews successfully perform several outcomes but looks at whether they are perceived to do so. reveals variation in several of these.

Table 5. Capabilities.

First, the GRECO and even more so the WGB are viewed as comparably better capable of organizing peer and public pressure on states than the IRM. For peer pressure, mean scores are 2.92 (WGB), 2.69 (GRECO), and 2.30 (IRM; p ≤ .001; 1-4 scale) and for public pressure 2.61 (WGB and GRECO) and 2.10 (IRM; p ≤ .001; 1-4 scale). The effect size is an eta squared value of 0.12 for peer pressure and 0.10 for public pressure. Peer pressure as a form of soft-persuasion is intrinsically linked with the OECD, and the WGB is no exception to this (Bonucci, Citation2014; Guilmette, Citation2004). WGB delegates mentioned that they had experienced peer pressure personally or that they had witnessed other delegates coming under social pressure during plenary sessions (interviews 40, 41, 42, 43). In the WGB and the GRECO, this pressure takes the form of the peers asking critical questions and requesting evidence of progress made. Other options are to publish critical press statements, to send technical delegations to underperforming states, or to contact the Minister of Justice. Interestingly, none of the interviewed officials mentioned the existence of peer pressure in the IRM and reportedly no direct questioning takes place between delegates during plenary sessions (interviews 20, 41). As one of them said: ‘No pressure is exerted at all. The IRG [Implementation Review Group] is just countries reading out statements’ (interview 20).

Second, the IRM (M = 2.85) is viewed much more favorably than the WGB (M = 2.44; p ≤ .01) and the GRECO (M = 2.34; p ≤ .001; 1–4 scale) regarding its ability to identify and substantiate technical assistance needs.15 The effect size is medium: 0.07. Importantly, however, African delegates are much more positive about the IRM’s capability to organize technical assistance than the Western European delegates, which accounts for the IRM’s higher mean value.16 As African countries are among the main recipients of technical assistance and Western European countries benefit the least from this, these different assessments are rather unsurprising.17 One interviewed delegate expressed her appreciation mentioning that they had managed to implement the review recommendations with the help of donor funding and the UN’s assistance (interview 30). The type of technical assistance that the UN provides and facilitates in the framework of the UN is unique, although the Council of Europe also operates several technical assistance and cooperation programs to assist states with implementing reforms. However, none of the interviewed delegates referred to any of these projects in interviews, and awareness about them seems to be low. Instead, at times the GRECO review process itself and the ensuing review recommendations are considered an indirect form of technical assistance (interviews 22, 38).

Third, the IRM (M = 2.68) is perceived as comparably less capable of presenting an accurate overview of reviewed states’ performances than the WGB (M = 2.96; p ≤ .0518) and the GRECO (M = 3.07; p ≤ .001; 1–4 scale). The effect size is 0.05. The evaluation reports of the IRM may give a very accurate depiction of the legal situation in a country but such legal analyses do not say much about a country’s anticorruption performance (interview 45). Furthermore, IRM delegates mentioned that they have rather little insight into how precisely the review of other countries is conducted or what the report is based on (interviews 22, 34, 41). Compared to the IRM, thorough assessment procedures ascertain that ‘the OECD actually gets to the bottom of things’ (interview 42), and ‘everything is on the table … you know everything’ in the WGB (interview 41). Section 6 explores the factors that fueled feelings of doubt and concern about the accuracy of the IRM’s evaluation reports.

Fourth, as to international cooperation and learning, the peer reviews expose little variation in their mean scores: for learning M = 2.94 (WGB), M = 2.97 (GRECO), M = 2.91 (IRM) and for international cooperation: M = 2.91 (WGB), M = 2.72 (GRECO) and M = 2.79 (IRM), both assessed on a 1–4 scale. They are valued for their potential to form international networks, which can be useful for mutual legal assistance and extradition requests, and to organize policy learning. Several delegates reported that they had learnt a lot from the review exercises and that the evaluations involved a valuable exchange of views (interviews 16, 17, 21, 25, 29, 31, 36). Participating in a peer review gives a fresh, outsider’s perspective on matters, revealing issues that previously had never been considered or that were simply taken for granted (interviews 30, 36). Furthermore, peer review enables delegates to establish contacts with colleagues from countries that they would otherwise hardly interact with (interviews 8, 30). In line with earlier scholarship on learning in peer reviews, notably in the OECD’s Environmental Performance Review (Lehtonen, Citation2005), learning reportedly takes place during country visits and plenary discussions (interviews 4, 31, 36, 42). Despite overall positive accounts of learning, what these mean scores do not show is that the Western European delegates are overall more skeptical about the IRM’s ability to foster mutual learning and international cooperation compared to African and Asia-Pacific delegates.19

Finally, the three peer reviews do not differ much in the extent to which they are perceived to deliver practically feasible recommendations, though the GRECO is viewed most favorably in this regard: M = 3.01 (GRECO), M = 2.78 (WGB), and M = 2.82 (IRM; 1-4 scale).20 Like with the IRM’s ability to organize policy learning and foster international cooperation, the Western European delegates and to a lesser extent the Latin American and Caribbean delegates are very skeptical about the IRM’s ability to execute this function, especially when compared to their African colleagues.21

6. Explaining differences in the authority of peer reviews

Now to that we know that the GRECO is more authoritative than the WGB and the IRM, how can these differences be explained? Notably,

Why is there disagreement about the functions of the IRM but not of the WGB and the GRECO?

Why is the WGB comparably less capable of applying the procedures fairly and consistently (proceduralism)?

Why are the WGB and the GRECO perceived as better able to exert peer and public pressure than the IRM (capabilities)?

Why is the IRM comparably less capable of delivering an accurate overview of reviewed states’ performance (capabilities)?

6.1. Membership size and composition

The first possible explanation for the observed differences in authority lies in the membership sizes and compositions of the peer reviews. Based on the literature, trust and like-mindedness were expected to be higher among delegates in the smaller-sized WGB and the GRECO compared to the IRM. This, in turn, was expected to foster their authority.

Indeed, the analyses show that the IRM has comparably less authority than the GRECO and, though less markedly, the WGB. Yet, can these differences also be attributed to variation in the memberships of the peer reviews and, if so, is this due to higher levels of trust and like-mindedness in the smaller peer reviews? To study this, delegates were asked to what extent they agree with the following statements:

I trust the other state delegates in the peer review and

Member states of the [peer review] have a common understanding of how to fight corruption.

Response options were: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, 4 =strongly agree.

Against expectations, shows that trust among delegates is not higher in the WGB (M = 2.84) and the GRECO (M = 2.92) than in the IRM (M = 2.93). The extent to which states are perceived to maintain a shared understanding of how to fight corruption also does not vary substantially across the three peer reviews: M = 2.71 (WGB), M = 2.83 (GRECO), and M = 2.71 (IRM).22 Thus, the survey finds no support for the initial expectation that mutual trust and a shared understanding of how to fight corruption hinge on membership size. One plausible explanation for the high levels of trust across the three peer reviews, regardless of their membership sizes, is that all evaluations are carried out by substantive experts on anticorruption, such as bureaucrats, prosecutors, judges, and academics. These experts can be considered to have formed an epistemic community of like-minded actors with shared norms, which transcends national boundaries (Haas, Citation1992). Several interviews, furthermore, suggest that substantive experts are considered to be driven less by political considerations (interviews 3, 20), hence fostering trust in the review process. Further research is, however, needed to confirm this.

Table 6. Mutual trust and a common understanding of how to fight corruption.

Does this mean that a peer review’s membership size and composition do not matter? On the contrary, it seems highly relevant for authority. Compared to the other two peer reviews, the IRM brings together states with vastly different cultures and experiences with peer reviews. Many European and Latin American and Caribbean officials participate in up to three anticorruption peer reviews, whereas most African and Asia-Pacific states only participate in the IRM. These different experiences with peer reviews translate into divergent views and expectations of what the IRM should do and how it should be designed to do this, which relates to the mission of the IRM (see also: Joutsen & Graycar, Citation2012). Furthermore, as shown below, their participation in multiple peer reviews gives several delegates a reference point against which the authority of the IRM is assessed.

Compared to their less‐experienced counterparts, delegates that have more experience with peer reviews, which mostly come from Western Europe and the Latin American and Caribbean Group of States, are also more supportive of surrendering control over the evaluations. From the first negotiations onwards, these officials favored the establishment of, what they call, a transparent, inclusive, and effective mechanism. Discussing their views on the IRM, quite a few of them directly compared the IRM to the GRECO, the WGB, and sometimes the peer review of the Organization of American States. Often, the IRM falls short of their expectations of what a peer review should do and how it should do this (interviews 3, 6, 15, 22, 25, 38, 45). Points of critique are the lack of transparency of the mechanism and the rather controlled input by NGOs in the review process (interviews 18, 20, 23, 24, 25). The WGB and the GRECO have set the bar high in terms of their expectations of what a peer reviews should do and can do.

Many delegates that are less experienced with peer review seem more hesitant to surrender sovereignty, to permit other stakeholders (e.g. civil society and academia) access to the peer review, and to increase the transparency of the IRM (interviewees 11, 19, 22, 26). One Asia-Pacific delegate expressed her concerns over restricting the reviewed states’ say over the formulation of their own evaluation reports, as it might provide the evaluators with an opportunity to criticize the reviewed states’ political systems (interview 19). Another delegate mentioned that several delegates feel uneasy with a revision of IRM procedures. Giving up control in one area (for instance, the publication of reports) might spark a domino effect in other areas, resulting in a gradual loss of sovereignty (anonymous interview). In their view, states first need to gain confidence in the peer review process, before sovereignty can be transferred.

6.2. Institutional design

As shown before, the IRM brings together states with vastly different experiences with peer reviews. Delegates differ in their views and expectations of what a peer reviews should and can do. To reach the necessary consensus for establishing a peer review in the UN, compromises had to be made (Joutsen & Graycar, Citation2012). The IRM’s large and diverse membership, and the corresponding divergence in views of the purpose it serves, have affected the mechanism’s institutional design. As we will see now, several institutional design features of a peer review affect its authority, notably: (1) the discussion of country reports in plenary sessions, (2) the procedures for the adoption of the report, (3) the degree of obligation of a peer review, and (4) follow-up monitoring.

6.2.1. The discussion of country reports in plenary sessions

Whereas plenary discussions of country reports form an integral part of the WGB and the GRECO reviews (i.e. experts convene to discuss country reports, modify them, and adopt them collectively), individual reports are not discussed in plenary sessions of the IRM. Such plenary discussions are, however, important as they provide the institutional structures for peer pressure to take shape. They help create transparency about other states’ policy performance and offer opportunities for direct dialog among delegates (interviews 6, 9, 38, 41). Furthermore, extensive plenary discussions on individual country reports are seen to perform a quality check of the review recommendations and contribute to their practical feasibility (interview 21). Several delegates mentioned that because individual country evaluations are not discussed in plenary meetings of the IRM, it is not possible to exert peer pressure (interviews 6, 15, 45). States can voluntarily take the floor and present their progress, but reportedly only focus on their achievements (interviews 27, 41). Few possibilities exist for a direct exchange of views or to broach comments of a more critical tone (interview 20). Moreover, in the absence of a good insight into how other states perform, it becomes very difficult to identify and criticize laggards.

6.2.2. The procedures for adopting reports

The GRECO and the WGB adopt country reports by means of the consensus minus one principle, which stipulates that all states need to agree on the formulation of the final report, apart from the reviewed state. In the IRM, in contrast, the adoption of the report is based on a constructive dialog among a selected group of members of the reviewing team and representatives from the state under review. As shown below, this affects the capabilities and the proceduralism of the peer reviews.

As to the capabilities dimension, the approach of constructive dialog explains why IRM reports are perceived as slightly less accurate than the reports of the WGB and the GRECO. IRM delegates have little insight into the negotiations and discussions that precede the formulation of the final reports (interviews 6, 41). The report is decided by consensus, which leaves the impression that states can freely modify their own report or have an important say over its content (interviews 4, 6, 20, 38, 41). As the authority concept employed in this study rests on subjective perceptions, rather than objective conditions or actual conduct, these views clearly have negative implications for the IRM’s authority. Irrespective of whether states modify their own reports, the perception that they (might) do so has negative effects for authority. At the same time, several other delegates, mostly from African and Asia-Pacific states, are more pleased with this procedure. They opine that it fosters a sense of ownership of the review report and makes states more inclined to listen to their peers and to implement the recommendations (interviews 11, 19). In the GRECO and the WGB, in contrast, delegates generally appreciate that the states cannot block the adoption of the report or remove some of its sharp edges (interviews 9, 22, 38). Direct references were made to the IRM as a less desirable alternative (interviews 3, 6, 15, 22, 38).

A second way in which the procedures for adopting reports matter is in relation to political bias in the reviews, which is part of the proceduralism dimension. The consensus minus one principle, as it is used in the WGB and the GRECO, appears to be a double-edged sword. Though overall appreciated, it is also seen to promote backscratching among delegates (interviews 8, 40, 42). Once a recommendation is issued to a state, this recommendation becomes a standard in future evaluations (interviews 17, 22). Consequently, delegates have an interest in preventing the classification of standards that would negatively affect their own country. Importantly, however, the GRECO and the WGB plenary meeting are often perceived to abate the implications of such backscratching. If some state delegates are biased, the remainder of the plenary is there to balance out such considerations, to ensure consistency in the evaluations, and to uphold their quality (interviews 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 34, 37).

As we saw earlier, the WGB is overall perceived as more politically biased than the GRECO, though both have comparable working procedures. Interviews suggest that various factors cancel out – or mitigate – the positive effects of the plenary discussion on the WGB’s authority. The United States, for instance, has a powerful position in plenary discussions of the WGB. They have the resources to prepare in detail for meetings, can send large delegations, and serve on the management committee, which sets out the direction of the WGB (interviews 3, 4, 6, 8, 40). Furthermore, the OECD Convention is largely modeled after the United States’ Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which makes them the most active enforcer of the convention and enables them to put pressure on other states to step up their game (Rose, Citation2015, pp. 92–93; interview 40). These factors are perceived to give the United States a disproportionally strong influence in the WGB (interviews 33, 40, 42), which conflicts with the notion of peer review as an instrument of equals. The finding that size matters in peer reviews is not unique to the WGB, but has also been claimed to exist in other OECD peer reviews (Porter & Webb, Citation2007). Marcussen even goes as far as to claim that the OECD has started to function as ‘an ideational agent for the United States’ (Citation2004, p. 101). Perceptions of unequal influence have negative implications for the WGB’s authority in terms of its proceduralism. Importantly, however, several delegates also mentioned that because of the United States’s active involvement, the WGB is able to exert considerable pressure on laggard states, enhancing the peer review’s effectiveness (interviews 4, 6, 33, 40).

6.2.3. The degree of obligation of a peer review

The degree of obligation of a peer review concerns the discretionary leeway states maintain over their own evaluation exercises. In the GRECO and WGB, country visits are obligatory, information is collected from a variety of sources and, in the WGB, it is mandatory to publish reports. In the IRM, in contrast, the reviewed state retains much more ownership of the review, which makes the collection of information and publication of results a much more controlled process (interviews 2, 3, 6, 18, 13, 20).

Like the procedures for adopting reports, the degree of obligation of a peer review affects the perceived accuracy of review output. In the IRM, which maintains the lowest degree of obligation, the effects of this feature on the capabilities of the instrument are two-pronged. Some Western delegates are concerned that the evaluation exercises may go less in-depth, as country visits are voluntary and nonstate actors are possibly excluded from providing input (interviews 3, 6, 15, 23). As one UN official mentioned when it comes to accessing information: ‘we are at the mercy of the state party under review’ (interview 2). Though not directly referring to the voluntary basis of country evaluations, other officials also indicated that a country visit is important to accurately assess a state’s performance (interviews 12, 13, 20, 30; GRECO interviews 1, 10, 16). Moreover, as country reports are not discussed in plenary sessions of the IRM, the country visit offers the only opportunity for delegates to exert some peer pressure (interview 20).

In contrast, several Asia-Pacific and African delegates espouse more support for the wide margins this peer review grants to the reviewed state (interviews 11, 19). Arguments in favor of the IRM’s present procedures are that, in these delegates’ view, fewer states would join the mechanism if these provisions were mandatory.

6.2.4. Follow-up monitoring

Finally, both the WGB and the GRECO have advanced systems in place to monitor states’ implementation of review recommendations from previous evaluation rounds. To this day, such a system for follow-up monitoring does not exist in the IRM, which leaves the evaluations a one-off exercise. Follow-up monitoring was frequently raised in connection to a peer review’s ability to exert pressure on states, that is, the capabilities dimension.

In the WGB and the GRECO, peer review is an iterative process. Follow-up monitoring is seen to enhance peer accountability and to put pressure on states to implement recommendations (interviews 6, 7, 8, 19, 21, 32). Even the threat of more intense and regular follow-up monitoring, in cases of substandard performance, may suffice to motivate states to beef up their anticorruption efforts (interviews 6, 8). The absence of a system for follow-up monitoring in the IRM then also explains why pressure in this peer review is felt to be lower (interviews 6, 20). As one IRM and WGB delegate explained:

At the OECD you just know … that after a while you have to report on what you have done. You work towards that and you make sure that you can present results. And then at the UN, there will be a report with recommendations, but that’s it.

Hence, in addition to the lack of discussion on country reports, the absence of a system for follow-up monitoring explains why peer and public pressure do not materialize in the IRM.

6.3. The officials that are involved in a peer review

A third explanation for differences in authority can be found in the officials that are involved in a peer review. In all three peer reviews, the evaluation exercises are carried out by substantive experts, which is deemed crucial for carrying out a thorough review, to arrive at an accurate assessment of states’ policy performances, and to provide to-the-point recommendations. Yet, of the three peer reviews, the IRM involves comparably the largest share of diplomats. In line with expectations, their attendance at plenary sessions adds a political element to meetings and creates a diplomatic atmosphere (interviews 6, 9, 15, 41, 45). Diplomats are seen to steer the discussion away from substantive anticorruption issues to inherently political, procedural matters (interviews 6, 45). Importantly, however, this political atmosphere was only reported to exist in the plenary sessions. The evaluations themselves, which are carried out by substantive experts, are perceived as technical and objective (interviews 20, 24, 29).

The presence of diplomats at plenary sessions also affects the capabilities of a peer review. First, diplomats’ main area of expertise lies in international diplomacy and negotiations, not in substantive anticorruption issues (interviews 18, 20). Consequently, diplomats often do not have the necessary background knowledge to ask critical questions about other states’ performances (interview 20). Second, and related to this, if states send career diplomats to attend these sessions instead of substantive experts, there are fewer opportunities for mutual learning. To stimulate mutual learning and knowledge transfer, the more substantive experts attending plenary sessions, the better it is for the peer review (interview 18, also GRECO interview 9). An additional consideration is that diplomats do not bring the knowledge acquired in the peer review back to the capitals for policy-making purposes (interview 16). Consequently, they cannot be turned into what Marcussen calls ‘reform entrepreneurs in their home countries’ (2004, p. 92).

The rather large share of diplomats attending IRM meetings clarifies why pressure in this peer review is felt to be lower and why plenary sessions are perceived as highly political. In the WGB and the GRECO, plenary sessions are mostly attended by substantive experts. This reportedly keeps the discussions technical, relatively nonpolitical, and facilitates peer pressure (interviews 3, 5, 6, 16). This corresponds to the point made by Barnett and Finnemore (Citation2004) that technical expertise might create the impression of depoliticization and objectivity. It also offers one explanation for the high levels of trust, reported earlier.

summarizes the three explanatory factors and the differences in authority they have helped to explain.

Table 7. Explaining authority.

7. Conclusion

How much authority do different anticorruption peer reviews have? And if they differ in their authority, how can these differences be explained? This study has shown that the GRECO is commonly perceived as more authoritative than the WGB and the IRM. This is a significant revelation considering some of the critique on peer reviews (and soft‐governance instruments more broadly), which tends to paint all peer reviews with the same brush or discards the instrument as a second‐best option to more binding agreements (Schäfer, Citation2004, Citation2006). It also indicates that there must be certain factors that either positively or negatively affect the authority of global governance institutions. Notably, the membership size and composition of a peer review, specific institutional design features, and the officials that are involved in the evaluation process influence a peer review’s authority.

This study was one of the first comparative analyses of relational authority in global governance. In addition, it ventured into new territory by seeking to explain differences in authority. What can we take from these findings for studying the authority of international policy instruments and organizations? First, the findings make a case for studying authority as a sociological rather than a normative concept (Keohane, Citation2006). This article does not go as far as to claim that only perceptions of governing institutions matter for authority to develop, as opposed to what these governing institutions actually do. However, perceptions do matter. As shown in the IRM, the possibility that some states modify their reports, manipulate the review process, and take advantage of the IRM’s lenient procedures, influences the IRM’s authority in the eyes of predominantly Western European delegates. When designing international policy instruments, we should therefore not only consider how specific procedures affect the practical functioning of these instruments (e.g. do they offer sufficient opportunities for peer and public pressure?) but also how they will be perceived to function (are they perceived as fair and accurate?). Second, and related to this, authority is a relational concept. Characteristics of the states that an international monitoring body or organization seeks to regulate do matter, so does their coherence (see also: Bernstein, Citation2011, p. 21). As shown in the IRM, many Western European delegates emphasize the need for transparency and effectiveness. Several African and Asia-Pacific have introduced a competing discourse about the importance of nonintrusiveness and sovereign equality. In peer reviews with large and diverse memberships, delegates may hold diverging views about what peer review is and should do. Third, the findings suggest that authority is often assessed against a reference point. Delegates who are familiar with the GRECO and the WGB are on average less positive about the IRM’s authority than newcomers to peer review. The GRECO and the WGB set the bar high in terms of their expectations of a peer review, which has negative implications for the IRM’s authority.

Taking an inductive approach, this article explored the different institutional and organizational-level characteristics that make some peer reviews more authoritative than others. Logically, the next step is to test whether these also hold for peer reviews in other policy areas and organizations. In addition, this study’s scope did not allow for an analysis of how authority develops over time, nor of how delegates’ authority perceptions compare to those of external actors, such as business or civil society. Finally, now that we know which peer reviews are comparably more authoritative than others and why, it is time to ‘go domestic’ again and to empirically probe the microprocesses that connect authority at the international level to reforms in member states. To find out how authority, member state compliance, and policy effectiveness causally connect, case study analyses of member states provide a good starting point. This will offer a more complete picture of how authority plays out domestically and the significance of peer reviews in the global fight against corruption.

List of Interviews

1) GRECO delegate, Western European and Others Group

2) UNODC official

3) IRM and WGB delegate, Western European and Others Group

4) WGB delegate, Western European and Others Group

5) GRECO delegate, Western European and Others Group

6) IRM and WGB delegate, Western European and Others Group

7) OECD official

8) OECD official

9) Council of Europe official

10) Council of Europe official

11) IRM delegate, African Group

12) UNODC official

13) IRM delegate, Western European and Others Group

14) GRECO, IRM, WGB delegate, Eastern European Group

15) GRECO and IRM delegate, Eastern European Group

16) Council of Europe official

17) Council of Europe official

18) UNODC official

19) IRM delegate, Asia-Pacific Group

20) IRM delegate, Western European and Others Group

21) GRECO delegate, Western European and Others Group

22) GRECO and IRM delegate, Eastern European Group

23) IRM delegate, Latin American and Caribbean Group

24) IRM delegate, Latin American and Caribbean Group

25) IRM delegate, Latin American and Caribbean Group

26) IRM delegate, African Group

27) IRM delegate, African Group

28) IRM delegate, Asia-Pacific Group

29) IRM delegate, Latin American and Caribbean Group

30) IRM delegate, Asia-Pacific Group

31) GRECO delegate, Eastern European Group

32) GRECO delegate, Western European and Others Group

33) GRECO and WGB delegate, Western European and Others Group

34) GRECO delegate, Eastern European Group

35) GRECO delegate, Eastern European Group

36) GRECO delegate, Eastern European Group

37) GRECO delegate, Western European and Others Group

38) GRECO and IRM delegate, Eastern European Group

39) GRECO delegate, Eastern European Group

40) WGB delegate, Western European and Others Group

41) IRM and WGB delegate, Western European and Others Group

42) WGB delegate, Non-European

43) WGB delegate, Eastern European Group

44) WGB delegate, Non-European

45) IRM delegate, Western European and Others Group

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Thomas Conzelmann, Giselle Bosse, Valentina Carraro, Marcia Grimes, Ellen Gutterman, Anja Jakobi, the three anonymous reviewers, and the participants in the ISA Annual Convention (Atlanta 2016) for their comments on earlier versions of this article. The author is also very grateful to Ian Lovering and Christophe Leclerc, who offered invaluable research assistance.

Disclosure statement

The author does not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hortense Jongen

Hortense Jongen is Postdoctoral Researcher at the School of Global Studies of the University of Gothenburg, where she works on a research project on legitimacy in private global governance. From 2013 to 2017, she was a PhD Candidate and subsequently Postdoctoral Researcher at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences of Maastricht University. Her PhD dealt with the authority of peer reviews among states in the global fight against corruption.

Notes

1 http://www.oecd.org/corruption/anti-bribery/anti-briberyconvention/oecdworkinggroupon-briberyininternationalbusinesstransactions.htm. Accessed 11-4-2018

2 http://www.transparency.org/news/feature/uncac_review_mechanism_up_and_running_but_urgently_needing_improvement. Accessed 11-4-2018.

3 This research is part of the research project ‘No Carrots, No Sticks: How Do Peer Reviews Among States Acquire Authority in Global Governance?’ (2013–2017), led by Thomas Conzelmann at Maastricht University.

4 Another example is the International Authority Database, developed at the WZB in Berlin.

5 http://www.oecd.org/corruption/anti-bribery/anti-briberyconvention/oecdworkinggrouponbriberyininternationalbusinesstransactions.htm. Accessed 21-9-2017.

6 https://rm.coe.int/rules-of-procedure-adopted-by-greco-at-its-1st-plenary-meeting-strasbo/168072bebd. Accessed 22-9-2017.

7 http://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNCAC/Publications/ReviewMechanism-Basic-Documents/Mechanism_for_the_Review_of_Implementation_-_Basic_Documents_-_E.pdf. Accessed 22-9-2017.

8 Several officials were sampled for more than one peer review. 532 distinct individuals were contacted. Respondents who filled out the survey for two peer reviews were included as separate entries.

9 Any respondent who answered Question 1 was included in the study. The total number of missing values per question did not exceed 10%, except for one survey item (11%). The number of missing values was quite proportional to the total number of responses per case study, but comparably highest for the GRECO. To deal with missing data, respondents were excluded pairwise in the analyses.

10 Considering their active involvement, diplomats were included in the survey of the IRM. For a considerable number of countries, diplomats are the only representatives to attend these sessions. Vienna is the location of the United Nations Office on Drugs on Crime, where most IRM-related meetings are held.

11 More responses were collected from national experts and diplomats from Western European states than from the Asia-Pacific Group of states.

12 Weighting ratios can be obtained upon request.

13 For a comparative assessment of the authority of the IRM and the UPR, see Carraro and Jongen (2018).

14 This round deals with corruption in the funding of political parties and electoral campaigns.

15 Without weighting, differences between the IRM and the WGB become significant at p ≤ .05 and the GRECO at p ≤ .01.

16 M = 3.31 (African) and M = 2.46 (Western Europe).

17 http://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNCAC/WorkingGroups/ImplementationReviewGroup/18-22June2012/V1252420e.pdf Accessed 24-4-2018.

18 Without weighting, differences become significant at p ≤ .01.

19 For mutual learning: M = 3.20 (Africa) and M = 2.50 (Western Europe). For international cooperation: M = 3.25 (Africa) and M = 2.32 (Western Europe).

20 Without weighting, differences become significant: between OECD and GRECO (p ≤ .05) and between the GRECO and the IRM (p ≤ .05).

21 M = 2.48 (Western European), M = 2.54 (Latin America and Caribbean), M = 3.31 (Africa).

22 Without weighting, differences between the GRECO and the IRM become significant at p ≤ .05.

References

- Barnett, M., & Finnemore, M. (2004). Rules for the world: International organizations in global politics. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Bauer, M. W., & Ege, J. (2016). Bureaucratic autonomy of International Organizations’ Secretariats. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(7), 1019–1037.

- Bernstein, S. (2011). Legitimacy in Intergovernmental and Non-State Global Governance. Review of International Political Economy, 18(1), 17–51.

- Bonucci, N. (2014). Article 12. Monitoring and follow-up. In M. Pieth, L. Low, & N. Bonucci (Eds.), The OECD convention on bribery: A commentary (2nd ed., pp. 534–576). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bossong, R. (2012). Peer reviews in the fight against terrorism: A hidden dimension of European security governance. Cooperation and Conflict, 47(4), 519–538.

- Busch, P.-O., & Liese, A. (2017). The Authority of International Public Administrations. In M. W. Bauer, C. Knill, & S. Eckhard (Eds.), International bureaucracy: Challenges and lessons for public administration research (pp. 97–122). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Carraro, V. (2017). The United Nations treaty bodies and universal periodic review: Advancing human rights by preventing politicization? Human Rights Quarterly, 39(4), 943–970.

- Carraro, V., & Jongen, H. (2018). Leaving the doors open or keeping them closed? The impact of transparency on the authority of peer reviews in international organizations. Global Governance, 24(4), forthcoming.

- Checkel, J. T. (2001). Why comply? Social learning and European identity change. International Organization, 55(3), 553–588.

- Conzelmann, T., & Jongen, H. (2014). Beyond Impact: Measuring the Authority of Peer Reviews among States. Conference paper presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions, Salamanca, 10–15 April 2014.

- Cronin, B., & Hurd, I. (2008a). Introduction. In B. Cronin & I. Hurd (Eds.), The UN Security Council and the Politics of International Authority (pp. 3–22). London, New York: Routledge.

- Cronin, B., & Hurd, I. (Eds.). (2008b). The UN Security Council and the Politics of International Authority. London, New York: Routledge.

- Cutler, A. C. (1999). Location ‘authority’ in the global political economy. International Studies Quarterly, 43(1), 59–81.

- Cutler, A. C., Haufler, V., & Porter, T. (Eds.). (1999). Private authority and international affairs. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- De Ruiter, R. (2010). EU soft law and the functioning of representative democracy: The use of methods of open co-ordination by Dutch and British Parliamentarians. Journal of European Public Policy, 17(6), 874–890.

- De Ruiter, R. (2013). Full disclosure? The open method of coordination, Parliamentary debates and media coverage. European Union Politics, 14(1), 95–114.

- Dellmuth, L. M., & Tallberg, J. (2015). The social legitimacy of international organisations: Interest representation, institutional performance, and confidence extrapolation in the United Nations. Review of International Studies, 41(03), 451–475.

- Donnelly, J. (1981). Recent trends in UN human rights activity: Description and Polemic. International Organization, 35(04), 633–655.

- Edwards, M. S. (2009). Public support for the international economic organizations: Evidence from developing countries. The Review of International Organizations, 4(2), 185–209.

- Freedman, R. (2011). New mechanisms of the UN human rights council. Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights, 29(3), 289–323.

- Grande, E., & Pauly, L. W. (2005). Complex sovereignty and the emergence of transnational authority. In E. Grande & L. W. Pauly (Eds.), Complex sovereignty: Reconstituting political authority in the twenty-first century (pp. 285–299). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Guilmette, J.-H. (2004). Peer Pressure Power: Development Cooperation and Networks - Making Use of Methods and Know-How from the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) and the International Research Development Centre (IDRC). Retrieved from https://idl-bnc.idrc.ca/dspace/bitstream/10625/25923/1/119954.pdf

- Gutterman, E. (2014). The legitimacy of transantional NGOs: Lessons from the experience of transparency international in Germany and France. Review of International Studies, 40(02), 391–418.

- Haas, P. (1992). Introduction: Epistemic communities and international policy coordination. International Organization, 46(01), 1–35.

- Hall, R. B., & Biersteker, T. J. (Eds.). (2002). The emergence of private authority in global governance (Vol. 85). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hansen, H. K. (2011). Managing corruption risks. Review of International Political Economy, 18(2), 251–275.

- Hansen, H. K., & Salskov-Iversen, D. (Eds.). (2008). Critical perspectives on private authority in global politics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2015). Delegation and pooling in international organizations. The Review of International Organizations, 10(3), 305–328.

- Hurd, I. (1999). Legitimacy and authority in international politics. International Organization, 53(2), 379–401.

- Johnson, T. (2011). Guilt by association: The link between states’ influence and the legitimacy of intergovernmental organizations. The Review of International Organizations, 6(1), 57–84.

- Johnston, A. (2001). Treating international institutions as social environments. International Studies Quarterly, 45(4), 487–515.

- Joutsen, M., & Graycar, A. (2012). When experts and diplomats agree: Negotiating peer review of the UN convention against corruption. Global Governance, 18(4), 425–439.

- Keohane, R. O. (2006). The Contingent Legitimacy of Multilateralism. GARNET Working Paper: No: 09/06.

- Koremenos, B., Lipson, C., & Snidal, D. (2001). The rational design of international institutions. International Organization, 55(4), 761–799.

- Lake, D. (2009). Relational authority and legitimacy in international relations. American Behavioral Scientist, 53(3), 331–353.

- Lake, D. (2010). Rightful rules: Authority, order and the foundations of global governance. International Studies Quarterly, 54(3), 587–613.

- Lehtonen, M. (2005). OECD environmental performance review programme: Accountability for Learning? Evaluation, 11(2), 169–188.

- López-Santana, M. (2006). The domestic implications of European soft law: Framing and transmitting change in employment policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 13(4), 481–499.

- Marcussen, M. (2004). The OECD as ideational artist and arbitrator: Reality or dream? In B. Reinalda & B. Verbeek (Eds.), Decision making within international organizations (pp. 90–105). New York: Routledge.