Abstract

The internationalization of the renminbi (RMB) raises important questions concerning dynamics of transformation within the post-crisis global monetary order. International political economists have predominantly analysed the currency’s cross-border evolution as a consequence of China’s macroeconomic conditions, domestic politics, and currency statecraft within a broader framework of international monetary hierarchy. In this article, we draw upon insights from financial geography to rethink the rise of the RMB as a process of transnational market-making involving actors and political agency across distinctive scales. We develop a multi-scalar framework that illuminates the distinctive agency of London and Hong Kong in this process, conceptualizing it as a form of subnational infrastructural power that facilitates financial market-making in concert with (and despite) dynamics of interstate geopolitics. This goes some way in remedying the scalar deficiency of existing theories of political economy of international money, as well as integrating considerations of power and political agency into financial geography perspectives. Empirically, we trace how the unique development of London’s offshore RMB market reflects this interplay between private financial actors, municipal-level authorities, and national political priorities. Finally, we discuss how IFC-led market-making relates to system-level dynamics by both facilitating ‘tipping points’ in global monetary change, as well as diluting national monetary power.

Introduction

The renminbi’s (RMB) rise within the post-crisis international monetary system (IMS) sparked renewed interest in the determinants of currency internationalization and the dynamics of global monetary change. The currency’s emergence into the global financial and monetary system was underpinned by a novel and distinctly political strategy for expanding the currency’s transnational reach, through the development of offshore RMB markets first in Hong Kong and then in key international finance centres such as London and Singapore. A decade after Zhou Xiaochuan (Citation2009) issued his landmark call for international monetary reform, though, the RMB has clearly not yet assumed a meaningful role as an international reserve and investment currency. Nor is it likely, based on current trends, to soon become one. Recent research on the dynamics of the IMS points to the continued entrenchment of the dollar (Cohen & Benney, Citation2014; Fichtner, Citation2017; Winecoff, Citation2015).

In this article we suggest that notwithstanding the RMB’s stalled momentum as a ‘challenger’ currency (Cohen, Citation2019), there remain political aspects of the process of RMB transnationalization that are of considerable interest to scholars of global finance, but which are not yet captured adequately by existing approaches to the political economy of international money. Existing theories that situate the nation-state as the primary locus of monetary power do not yet capture the full spectrum of change and continuity in the IMS. They tend to underspecify the mechanisms that link gradual changes to moments of rapid systemic transformation, whilst neglecting the relationships between distinctive ‘levels’ of analysis or treating them as unduly static (Cohen, Citation2015; Helleiner & Kirshner, Citation2012a; Kirshner, Citation1997). Such approaches to examining international currencies do not, in our view, capture the overlapping financial and geopolitical transformations characteristic of the contemporary global political economy.

We develop a multi-scalar framework highlighting the role of IFCs as pivotal sites of agency and power alongside nation-states within processes of transnational RMB market-making. Focusing empirically on the role of London and Hong Kong in the politics of constructing offshore RMB markets, we argue that such an approach to theorizing international monetary relations can better illuminate the interaction between more gradual, granular changes and larger systemic transformations. Highlighting the political agency of IFCs and the importance of their relationships with state power enables observers of transnational monetary politics to develop more nuanced theories of how national state structural power emerges within the global financial system, the conditions under which rising monetary influence produces a ‘tipping point’ in a broader process of systemic monetary change, and how monetary sovereignty is both augmented and diluted by the agency of subnational actors.

In developing these arguments, we advance the literature on the political economy of international money in four ways. First, we bring IPE and financial geography into a more constructive theoretical dialogue over the spatial dimensions of transnational monetary power. We argue that networked and multi-scalar interdependencies forged through the RMB’s globalizing influence prompt conceptual rethinking of transformative dynamics within the IMS. Specifically, framing currency internationalization as a predominantly state-centric phenomenon has obscured the importance of agency exercised by and within international financial centres (IFCs). Developing a more geographically nuanced understanding of what we refer to as RMB transnationalization reveals different facets of emerging Chinese monetary power.

Second, we draw on Michael Mann (Citation1984) to theorize the infrastructural power embedded in IFCs. We argue that as spatially concentrated sites of institutional, epistemic, and ideological authority, IFCs shape currency transnationalization by exerting subnational agency and authority. This enables them to sew together actors at different political levels into institutionalized patterns of financial interdependence, catalysing monetary change by operating at the interstices of the state-market matrix. Rather than rejecting the central role of the state, we argue for a more spatially sensitive reading of the diffuse ways in which state authority underpins global finance. Importantly, the transnational linkages between global cities are both constituted through and dependent upon sovereign state authority but also possess discrete forms of power and authority in their own right, modifying the parameters of state influence over transnational financial markets and creating new vulnerabilities. City-level infrastructural power thus shapes global financial developments, feeding into national and global arenas of political action and potentially both enhancing and diminishing the structural power of states that contain IFCs.

Third, we undertake a case study of IFC infrastructural power in shaping London’s emergence as the global hub for RMB foreign exchange trading and the largest Western hub for RMB deposits and bond issuance (City of London Corporation and PBOC, Citation2018). Drawing upon a dataset of policy documents and interviews with key public and private actors in London and Hong Kong, we trace the influence of multi-level and transnationally networked agents of RMB transnationalization by examining cooperative efforts in establishing offshore RMB markets between the City of London, UK government agencies, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), and central Chinese authorities. Through this empirical focus on the role of the City of London Corporation and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, we demonstrate that public authorities and private firms within IFCs are important agents in shaping RMB transnationalization. London and Hong Kong play distinctive roles in the current international monetary order not necessarily representative of IFCs in general, but which are critical nodes for processes of both change and continuity in the current IMS. Our aim is not, therefore, a functionalist and generalizable theory of IFC agency as infrastructural power, but rather, through a more historical institutionalist lens, to better understand contemporary processes of offshore market-making necessary for currency transnationalization, and thereby to point towards how IFCs can play an important role in catalyzing change at particular historical junctures. The analysis demonstrates how RMB transnationalization is being shaped by this infrastructural power in ways that evade existing theories of monetary dynamics.

Finally, we draw these claims together to examine how infrastructural power relates to deeper processes of change in the international monetary system. The construction of financial market infrastructure, the strengthening of transnational monetary linkages, and the institutionalized expansion of financial networks enlarge the policy space available to Chinese policymakers in the event of future instability surrounding the dollar. In doing so they lay the foundation for future ‘tipping points’ within the international monetary order – periods of rapidly accelerated and networked socio-economic transformation. The qualitative establishment of an offshore RMB market infrastructure enables a potentially rapid quantitative increase of RMB trading within intensified efforts to promote its international role. Although the infrastructural power we identify at work in RMB transnationalization in itself is clearly insufficient for engendering structural change in the IMS, our findings demonstrate that this does not render infrastructural power epiphenomenal. Rather, it points to the increasingly complex and multi-scalar processes of market-making through which structural change necessarily takes place, and to the benefits of integrating such processes into theories of change and continuity in the IMS.

From currency internationalization to transnationalization

Scholarship on international currencies has a rich lineage within IPE. Early contributions focused on the political economy of sterling (Cohen, Citation1971; Strange, Citation1971), and subsequent assessments explored the US dollar’s relevance to American power (Gilpin, Citation1987; Strange, Citation1987). These approaches to international money were linked to theories of hegemonic or structural power that view possession of the international currency as a hallmark of global dominance, framing the analysis of international currency usage within a context of great power rivalry and systemic transition (C. Kindleberger, Citation1981). Cohen (Citation1998) reshaped understandings of monetary geography by illustrating the hierarchical topography of international currencies, yet confined his theorization to the interaction between sovereign states and between states and private sector financial actors. China’s emergence as a global economic power in conjunction with Beijing’s ambitions in promoting the currency’s rise has catalyzed a rich literature examining how the RMB’s international usage reflects China’s expanding global presence (Chin, Citation2014; Chin & Helleiner, Citation2008; Chin & Wang, Citation2010; Helleiner & Kirshner, Citation2012b; Hung, Citation2013). Given the literature’s origins in the study of hegemonic world powers, and the importance of currencies in great power politics, it is unsurprising that scholarship on the RMB often commences with considerations of national characteristics as determinants of currency internationalization. National determinants of monetary power have been theorized in various ways. From a geopolitical perspective, international money is conceptualized as a facet of national power exercised through monetary statecraft largely in a zero-sum world (Cohen, Citation2019; Helleiner & Kirshner, Citation2012a; Kirshner, Citation2008). The agents of monetary power are identified as large states, ‘the great and near-great powers’ (Kirshner, Citation1997, 23), capable of exercising coercive influence over other states and repositioning themselves within the global currency hierarchy. Conversely, Cohen’s (Citation2006) framework for the ‘macrofoundation of monetary power’ views monetary power as deriving from monetary autonomy — a state’s capacity to avoid and ameliorate macroeconomic adjustment costs.

Although political economists have incorporated sub-national spatial scales into the investigations of RMB internationalization and monetary transformation more broadly, these have not cohered into sustained theoretical consideration of their distinctive modalities of power. Those scholars who do explicitly examine political scales such as the global city tend to treat them as important ‘sites’ of contestation wherein national interests are pursued ( Pardo et al., Citation2019; Subacchi & Huang, Citation2012 ). As Li (Citation2018, 452) has aptly observed, ‘it is still analytically important to recognize the role of Hong Kong in the different policymaking stages that led to the maturation of the world’s first offshore renminbi center. But the subnational political leverage that facilitated this has been scantily acknowledged by researchers.’ Yet notwithstanding this admonition, Li’s emphasis rests not on theorizing the transnational agency of Hong Kong as a world city, but rather the empirical matter of Hong Kong’s ‘leverage’ within the broader dynamics of national policymaking and Beijing’s pursuit of monetary power. From the prevailing IPE of money perspective, the urban scale features as a resource for accumulating national power through robust macroeconomic structures and national financial systems (Chey, Citation2013; Chin, Citation2014; Helleiner & Malkin, Citation2012; Otero-Iglesias & Vermeiren, Citation2015; Volz, Citation2014), rather than a modality of power deserving distinct conceptualization.

This brief survey prompts the question: to what extent are theoretical frameworks that take national macroeconomic and geopolitical power as their conceptual point of departure still adequate for understanding the deepening presence and significance of the RMB within the international monetary system? Our answer is a nuanced one. We do not deny the relevance of national economic and geopolitical motivations and strategies associated with the rise of the RMB. The role of IFCs in promoting RMB transnationalization has to be situated within the dynamics of interstate geopolitics. But we do argue that adopting the territorial nation-state as the theoretical point of departure for analyzing currency internationalization occludes forms of power and trajectories of change that cannot be subsumed into a framework that interprets the RMB’s fortunes as a function of Chinese state interests and national capitalist development. Our ultimate outcome of interest remains understanding systemic change in the international monetary order, but we are concerned equally with the granular and multi-scalar processes of institutional development and political-economic agency that both enable and generate systemic change.

For this reason, we propose currency transnationalization rather than internationalization to denote the broader process of expanding the significance of a currency beyond the territorial jurisdiction of a currency-issuing nation-state. This decouples the concept of international money from that of national state sovereignty, with two consequences. Firstly, a currency’s transnationalization is not measured purely through its quantitative share of global reserves or cross-border transactions – but rather through the spatial dispersal of the qualitative institutional infrastructure that supports usage. And secondly, the preferences and policies of the issuing nation-state are deprivileged as the de facto theoretical starting point. Reframing the rise of the RMB as a process of currency transnationalization highlights the genuinely transnational axis of qualitative as well as quantitative financial transformation that cuts across and through different national spaces yet remains embedded within privileged and networked spatial sites. It also highlights the more dispersed and de-territorialized forms of monetary sovereignty practiced within the contemporary global economy (see Agnew, Citation2005).

Economic and financial geographers have problematized the global monetary and financial system in a more spatially complex manner than IPE. Their conceptual mapping of the international monetary system (Wójcik et al., Citation2016) and global financial networks (Coe et al., Citation2014) helps us transcend methodological nationalism. According to Agnew (Citation2010, 221) the impact of globalization on geography “entails its reformulation away from an economic mapping of the world in terms of state territories towards a more complex mosaic of states, regions, global city-regions, and localities differentially integrated into the global economy.” From this perspective, globality is defined by a combination of global networks and localized territorial fragmentation. Accordingly, there is an increasing importance of cross-border flows to spatially uneven networks (Agnew, Citation2010, 220–21). This focus on the networks and linkages connecting the actual spaces of transnational finance — global cities — illuminates the role of sub-national actors and agency. It shows how institutions within IFCs shape financial markets in ways that feed back into national and global arenas of political action.

These geographic scales are not static. As a dynamic social construction, scale is ‘periodically transformed’ by different actors, power struggles, and institutional processes. Scales feedback reciprocally into social, political, and economic processes (Brenner, Citation2001). Dominant financial centres like the City of London are, for example, able to influence and mould the conception of ‘national’ interests and policies pursued by their host governments while also internalizing global forces through their cosmopolitan networks of international banks and financiers. IFCs should be understood as sites that are simultaneously local, national, and global. They globalize local, subnational spaces via opening them up to worldwide networks and flows. This in turn reshapes national politics by driving adaptive national governance strategies and policies that respond to the presence of highly globalized localities within national territory (Sassen, Citation2008). Understanding the linkages between national and global monetary power requires that we take seriously the construction of these scales through their interaction with actors operating within global cities.

The frameworks and concepts being developed within economic geography yield insights that help us ‘chart’ emerging monetary dynamics. But they also tend to understate notions of power and contestation that are the theoretical bedrock of IPE approaches. As Wójcik (Citation2013, 2739) observes, power is an understudied concept within literature on IFC networks. Similarly, Martin (Citation2008) presses for increased engagement with political dimensions in the context of rapidly changing spaces of economic regulation. But as Agnew (Citation2012, 576) laments, too often ‘when “the state” is brought in, it is either as an exogenous force introducing shocks or as sets of policies and plans functional to the interests of presumed dominant groups’. Discussing the role of London within the internationalization of the RMB, Hall (Citation2017, 2) notes that the financial geography and global cities literature needs to, ‘better understand the role of the state, and financial and monetary authorities in particular, in shaping the reproduction and developments of international financial centres’. In this sense, despite well-placed calls for greater political sensitivity, the conceptualization of global finance by geographers remains curiously devoid of political agency underpinning power relations. These conceptions of the power exercised within the international monetary system remain thin. They tend to either revert back into a black-boxed notion of national state interests in affecting macro-level monetary changes (for example, Wójcik et al., Citation2016), or to focus on IFC development itself as the outcome of interest (Töpfer & Hall, Citation2018).

Our aim is to address these complementary gaps within the IPE and financial geography approaches. By connecting the multi-scalar sensitivity of geographers to the power—political and macro—oriented disposition of IPE we hope to address the narrow scalar imaginaries of IPE and the political deficit within financial geography. This raises a key theoretical issue - what are the sources and characteristics of IFC agency?

Theorizing the infrastructural power of IFCs

We conceptualize IFCs as transnationally networked sites of infrastructural power sewing together sub-national, national, and global actors into institutionalized patterns of financial interdependence. Interdependence in this sense captures both cooperative and competitive dynamics that play out within and between IFCs. Theorizing IFC agency in this way departs from existing frameworks that struggle to bridge the relational and structural aspects of IFC power. A first such framework conceptualizes IFCs as a reflection of private sector interests developing economies of scale and favourably shaping regulatory environments (Kindleberger, Citation1973). This reflects a tendency to treat the IFC as a political domain within which private actors challenge state authority (Agnew, Citation2010). Secondly, they can be conceptualized as subnational tools for the pursuit of national interests, accumulating financial wealth and extending monetary power, for example as agents of ‘economic patriotism’ (Clift & Woll, Citation2012; Morgan, Citation2012). In this reading they embody a linear extension of sovereign state power. They have been further conceived as distinct political agents in themselves, operating as municipal authorities in competition against other urban centres and subnational political authorities, and responding to their own localized political constituencies (Pauly, Citation2011). These relational accounts of IFC politics rest uneasily with accounts of IFC development and networks that emphasize the significance of structural complementarities and provide explanations of institutional stability rather than dynamics of change (Wójcik, Citation2013).

Approaching IFCs as sites of infrastructural power synthesizes these perspectives. Based on a view of societies as constituted by ‘multiple overlapping and intersecting sociospatial networks of power’, Mann’s (Citation1984) seminal account of state formation highlights infrastructural power as a distinctive source of state influence over civil society, enabling the implementation of governance decisions through a defined territory but also allowing both the state and non-state actors to maintain autonomy and independent interests. As Weiss defines it, the “broad tapestry of infrastructural power [comprises the] state’s ability to link up with civil society groups, to negotiate support for its projects, and to coordinate public–private resources to that end”. (Weiss, Citation2006, 168).

We depart from Mann by challenging his emphasis on the logic of ‘territorial centralization’ and the associated claim that infrastructural power increases the ‘territorial boundedness of social interaction’ (Mann, Citation1993: 59; Citation1984: 210). We suggest that the specific spatial properties of IFCs, their internally cosmopolitan and transnationally networked nature, serve to partially ‘denationalize the national’ (Sassen, Citation2008; Citation2013) rendering it sensitive to a wider set of global relations. This constrains the territorialized logic of sovereignty by requiring shared sovereignty and complex patterns of multi-scalar transnational cooperation to achieve desired governance outcomes. Here we agree with Agnew’s claim (Citation2005: 442) that under conditions of globalization ‘the transactional balance is increasingly tipping in favour of a networked system of political authority that challenges territorialized state sovereignty as the singular face of effective sovereignty’. Thus while the infrastructural power of IFCs can enhance the global reach of state power, it also imposes new constraints on the unilateral logic of territorialized sovereignty. Emphasizing the mutual dependence between state power and public and private actors within IFCs we emphasize the condition of ‘governed interdependence’ (Weiss, Citation1998). Governance is a negotiated relationship in which both state and societal actors maintain autonomy, but which is nevertheless delimited and directed by broader goals set and monitored by the state. In turn, this produces ‘transformative capacity’ to coordinate structural economic change in response to external pressures (Weiss, Citation1998).

In the monetary realm, infrastructural power operates transnationally through the networks and nodes that comprise both the conduits for capital flows and the arrangement of rules, institutions, and authority that structure these flows. Applying the concept to dollar internationalization, Konings (Citation2011, 6–13) refers to the historical development of a ‘transnational infrastructure’ of financial relations, constituted through the Euromarkets and governed by American rules relating to the trading of dollar debt, involving a form of authority not over territorially concentrated subjects but rather over networks and communities of financial activity. The IFCs that host global financial markets may thus be said to have a form of spatiality dramatically distinct from their host states (Wójcik, Citation2013). Although the infrastructures of digital communications and professional services that constitute contemporary global finance are embedded within different national territories, the transnationally interconnected manner in which this embedding occurs through a network of cosmopolitan world cities renders these infrastructures sensitive to a wider set of global relations (Sassen, Citation2008; Citation2013).

Within this global network that is both nationally embedded and singularly denationalized, the infrastructural power of IFCs is central to the process of transnational market-making. IFCs constitute sub-national but globally interconnected spaces of governed interdependence where new market practices, regulatory approaches, epistemic framings and policy agendas are devised and implemented. In conjunction with other actors across multiple scales, ranging from other subnational authorities, to state agencies, transnational financial firms, foreign governments and global institutions, they shape the infrastructural foundations for global finance. In the context of the IMS, they are crucial actors in determining how to create the conditions for trading and circulating offshore currencies. IFCs exist at the intersection of state, private, and para-state actors (such as the City of London Corporation), who coordinate and build relationships across these lines, consolidating the international financial centre itself but also transnational financial networks. In so doing, they pull together the bases of social power, conceptualized by Mann (Citation1984) as the ‘raw material’ of infrastructural power: ideological, political, and economic.

There are two key mechanisms for this deployment of infrastructural power in financial market-making. The first is by mediating contentious geopolitical interstate relations. The authority of subnational authorities within IFCs to represent financial communities as well as their embeddedness within broader national power structures enables them to pursue interests that are distinct but often synergistic with national political priorities. The second mechanism of IFC infrastructural power is by close association with and authority over the financial institutions whose activities constitute transnational financial networks. This embeddedness within the private sector likewise permits the pursuit of interests that, whilst not mapping neatly onto those of financial capital, are often highly aligned.

These patterns of interaction between national monetary statecraft, transnational capital, and IFC infrastructural power are conceptually nuanced but theoretically significant. For as long as deepening financial transnationalization is seen as in the national political interest, then the infrastructural power exercised by IFCs constitutes a significant component in enabling structural linkages to form, aligned with broader institutional and economic transformations. But this bolstering of national structural power by IFCs is not inevitable. IFC political authorities continue to ‘prime’ themselves and their constituent financial communities for financial market-making even when the high politics of geopolitical manoeuvrings are working against the interests of IFCs as specific nodes in the networks of transnational capital.

Infrastructural capacities of IFCs are closely linked to patterns of structural power within the global financial system. For Susan Strange, structural power comprised the ability ‘to decide how things shall be done, the power to shape frameworks within which states relate to each other, relate to people, or relate to corporate enterprises’ (Strange, Citation1994, 25). Such power does not derive from the mere existence of the structures themselves, but through the capacity to exert strategic control and sovereign authority over processes that work through these structures in order to bring about a relationship of leverage and dependency. In Strange’s case, this was predominantly a story of the power of the US state manifesting through control over transnational financial, productive, and knowledge networks, founded upon a territorially based yet global security apparatus. One of the more noteworthy limitations of Strange’s framework however is its lack of a clearly specified notion of historical transformation (May, Citation1996). Strange’s framework provided an account of the benefits of structural power once it had already come to exist but offered no clues as to how such structural capacity emerges historically. We suggest that such clues might be found in more granular and subnational patterns of institutional transformation that generate the transnationally extensive structures upon which nationtal state power is founded within globalization.

We therefore differentiate the infrastructural power of an IFC from the more macro-oriented structural power of the nation-state. This is to emphasize an analytical shift in both the nature and locus of this power, such that the infrastructural power of IFCs is different—and in our conception—prior to the structural power generated through IFCs. The infrastructural power of IFCs is distinct because they contain the institutional capacity, technical know-how, and international networks to construct and maintain transnational financial markets, thereby laying the foundation for longer-term development of structural power within the global financial system. In contrast to prevailing theories of the relationship between IFCs and other actors in the global political economy, the nation-state is potentially able to leverage the infrastructural power of IFCs, but it is not the direct source of that power. It is the peculiar global-local cosmopolitanism of IFCs — functioning as entrepôt hosts for transnational financial institutions, and linking national financial structures with foreign financial centres — that serves as the crucial source of their power and influence.

It should be clear that what we are emphatically not suggesting is the bypassing of national state power in global monetary transformation. In terms of their relationship to national state power, IFCs clearly remain subordinate. But this can nonetheless enhance their infrastructural power even as it diminishes their direct relational power, as IFCs are able to facilitate the construction of offshore networks precisely because they exert forms of sub-national political agency and transnational connectivity that are distinctly insulated from democratic and diplomatic/geopolitical pressures. This has been the case in both Hong Kong and the City of London, and we therefore echo calls for financial geography to connect its focus on the networked relations between IFCs to the larger political context of state power (Agnew, Citation2012; Hall, Citation2017). As the following sections illustrate, the dynamics of market-making and institutional development that constitute RMB transnationalization reflect the interplay of these top-down and bottom-up forms of transnational political agency.

Infrastructural power in RMB transnationalization

Deploying this conception of infrastructural power, we analyze the role of London and Hong Kong in RMB transnationalization from three vantage points. First, we briefly identify the historical, institutional, and geographic factors involved in the formation of their infrastructural power. We then turn to the implications of their embeddedness within the UK and China’s broader national policy frameworks and global geopolitical context, detailing how this not only catalyzes and activates but also conditions infrastructural power. Finally, we trace how key agents within London and Hong Kong have exercised infrastructural power in the process of offshore RMB market development. The analysis is not directed towards evaluating the ultimate success of RMB ‘internationalization’ itself as a consequence of infrastructural power. Rather, it is oriented towards the market-making processes within broader dynamics of transnationalization, highlighting the way that the HKMA and City of London Corporation have operated both beneath and between Chinese and British national interests and state policies in establishing the institutional foundations of a new transnational financial market. Such offshore markets are necessary conditions for the systemic transnationalization of a currency, and we demonstrate how systemically important nodes in the international monetary system such as London and Hong Kong play a role in their construction and development. As the penultimate section will explore, such IFC infrastructural power entails a form of contingent causality, an indispensable (though not sufficient) facilitator of structural change in the presence of other key enabling factors.

The foundations of london’s and Hong Kong’s infrastructural power

London and Hong Kong have each long served as important IFCs, ranked second and third respectively within the global hierarchy (Yeandle & Wardle, Citation2019).Footnote1 Although distinctive in both form and function, the political agency of each is shaped by deep historical-institutional legacies. This is reflected in the power wielded by the respective agencies mandated to advance international competitiveness and financial market infrastructure in each centre - the City of London Corporation and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority. The infrastructural nature of this power stems from two inter-related sources. First, the historical legacies of their relationship to greater state- and empire-based political power structures. And secondly, their territorially centralized epistemic authority that has developed in tandem with their close embeddedness with private financial market sectors. These two factors have generated for these IFCs the capacity to extend the infrastructural foundations of state power under conditions of financial globalization.

Both the City of London and Hong Kong have a defined but limited degree of autonomy from a larger national concentration of sovereign power - specific freedoms that distinguish them from other sub-national political authorities. For the City, this takes the shape of the City of London Corporation - a local government authority whose status and power reflects the vital commercial and financial centrality of London within the UK political economy. It is at once a local governing authority, a domestic political power, and an international lobbyist for the financial interests of the City (Green, Citation2018). These objectives are underpinned by a set of distinctive political privileges that are linked to the City Corporation’s status as the, ‘oldest continuous democratic commune in the world’, with a constitution that is based in the, ‘ancient rights and privileges’ of citizens (Glasman, Citation2014), but now with business representation outweighing that of individual residents. The City Corporation also has a permanent representative within Parliament, the City Remembrancer, with responsibility for advancing the City’s interests in the national legislative process (Mathiason et al., Citation2012).

Hong Kong is granted a similar political autonomy under the ‘one country, two systems’ framework established by Deng Xiaoping. As a ‘Special Administrative Region’ (SAR), Hong Kong has a mini-constitution known as the ‘Basic Law’, a ‘hybrid regime’ combining both democratic and authoritarian elements (Fong, Citation2013). Half of the seats in the Hong Kong Legislative Council are chosen via popular election yet the government head, known as the Chief Executive, ‘remains handpicked by an election committee controlled by Beijing and cannot be held accountable to the Hong Kong people’ (Fong, Citation2013, 859). Although the city’s de facto political autonomy has been significantly eroded since reunification, its retention of its own monetary authority, currency, and legal system has enabled it to retain a liberal laissez-faire regulatory order germane to the development of the offshore RMB. Chinese leaders have consistently reiterated the importance of these institutional features and their commitment to Hong Kong’s leading financial role in Chinese economic development and external financial liberalization (Fung & Yau, Citation2012, 108).

Both the Hong Kong SAR and the City of London have also historically been defined by close interdependent relations between public and private sectors and interests, resulting in a degree of insulation from popular democratic and broader national political pressures. This is manifest institutionally in London via the overrepresentation of business votes within the City Corporation’s Court of Common Council as well as the pro-business lobbying role exercised by the Corporation on behalf of financial services. In the case of Hong Kong, long-standing business domination of politics spans the transition from its colonial status under British rule to its post-colonial return to Chinese rule. Under both colonial and Chinese rule, local business elites were viewed as integral to mediating state-society relations and were brought into a symbiotic relationship with the Hong Kong government (Goodstadt, Citation2000). This was expressed institutionally in the overwhelming presence of business interests in the Basic Law Consultative Committee that designed Hong Kong’s constitution, as well as business sector domination of the Chief Executive role post-handover (Ortmann, Citation2015). These interdependent relations between public authorities and financial and professional services firms deeply embedded in global financial networks have produced a territorialized epistemic capacity that is relevant not only to their role in the domestic political economy, but also in their forging of new ‘axes’ (Wójcik, Citation2013) of transnational financial cooperation, conflict, and interdependency.

IFC infrastructural power and national interests in RMB transnationalization

A key distinguishing feature of Chinese currency transnationalization has been a state-sponsored commitment to promote its usage through a set of interrelated policies. London’s and Hong Kong’s infrastructural power have primed them to play distinctive roles in this process of the RMB’s offshore expansion. Their capacity to do so also depends upon the prevailing political relationship between their host nation states, alongside wider global geopolitical contexts and national macroeconomic policies. The exercise of infrastructural power by these IFCs has taken place within and is therefore subordinate to the authority of sovereign state power. Yet as theorized above, IFC infrastructural power is qualitatively distinctive to territorialized sovereign state power. IFC power exhibits distinctive transnational spatial properties and scalar forms of agency, producing outcomes that deterritorialize and complicate sovereign authority by necessitating shared sovereignty and complex patterns of multi-scalar governance across geographically extensive networks.

The post-financial crisis conjuncture opened up important policy space for increased engagement between the UK and China. The crisis prompted complementary developments that catalyzed closer Sino-UK political cooperation and deeper financial interdependence. Chinese elites had responded to the crisis of the dollar-based global financial system by pushing for an increased role for alternatives to the dollar (Chin & Wang, Citation2010; Zhou, Citation2009), of which RMB internationalization formed an important strategic element. On the UK side, Chancellor George Osborne made closer economic (and particularly financial) ties with China a cornerstone of the 2010 Coalition’s economic policy. Britain’s courtship of Chinese finance was in part motivated by a long-term assessment of the international monetary order that projected a relative decline of US financial power and a rising global volume of Chinese capital flows. The Bank of England estimated that China’s gross international investment position could reach 30 per cent of world GDP by 2025 (Bank of England, Citation2013). With this expectation in mind, the UK government sought to position London favourably to take advantage of changing global financial conditions by establishing it as a major centre for RMB-business (HM Treasury 2014). This involved a concerted diplomatic effort, including taking a softer stance on China’s currency value after the crisis, during a time when the US and EU had criticized China for securing economic recovery by undervaluing the RMB (Szalay, Citation2019).

This alignment of state interests created significant policy space for city-level authorities to redouble efforts to expand and strengthen offshore RMB markets. The Chief Executive of the HKMA had already mooted the development of offshore RMB markets as early as 2001 (Yam, Citation2001), but his proposal had been rebuffed by Beijing policymakers preoccupied with restructuring and listing the state-owned banking sector (Gruin, Citation2019). Post-crisis, Hong Kong’s distinctive political and economic characteristics placed the city in an ideal position, not just to channel foreign capital in and out of China as it had traditionally done throughout the reform era, but to act as an experimental locus of offshore RMB market development. Due to its embeddedness within both public and private global financial networks, this role included serving as model for RMB hub development as well as a substantive infrastructural centre for offshore currency clearing and exchange.

Converging national priorities also created the political context for the City of London Corporation and major transnational banks based in the UK to begin exploring the potential for an offshore RMB market in London (Green, Citation2018: 294). The City of London Corporation’s Special Advisor to Asia, Sherry Madera, recalls how in 2012 the UK government approached the City Corporation and instructed them that,

We need to do something to really support the RMB entrance into the UK, build awareness, help advise both sides on how it is that we can create an environment that supports RMB usage.Footnote2

With institutional and epistemic support from the City of London Corporation, RMB internationalization became a UK government policy, integrated into and coordinated through the annual UK-China Economic and Financial Dialogues conducted at the ministerial level. But, as we examine in greater detail in the next section, the actual construction of the markets has been the preserve of the Corporation, leveraging its unique political identity to act in tandem with a wider network of transnational private actors as well as other city-level authorities such as the HKMA.

In this manner, London’s and Hong Kong’s infrastructural power within this particular post-crisis conjuncture played an important role in shaping national policy. This intentional development of offshore RMB markets is a novel feature when compared to historical forms of currency internationalization, one that emerged so as to draw upon the privileged position of Hong Kong within the global financial system itself (Subacchi, Citation2016). Through a variety of policies such as the Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (RQFII), the Chinese government began to explore offshore RMB markets as a means of incrementally increasing the supply of external liquidity while simultaneously insulating the domestic market from the risks (principally in the form of destabilizing capital flows) associated with capital account liberalization (Subacchi, Citation2016). Insulation also rendered the currency more attractive, by enabling the RMB to be traded without restriction, in contrast to the tightly regulated onshore CNY market. Institutional dynamics of RMB transnationalization provide a concrete expression of Hong Kong’s privileged status, with the city functioning as a first-mover laboratory for many of the major policy innovations that established the offshore RMB market and which would be replicated in other offshore RMB hubs. As the strategy of developing offshore RMB markets in Taipei, Singapore, and London as a mechanism of currency transnationalization evolved, this dynamic of gradual political negotiation and market development was informed by and bolstered Hong Kong’s status as China’s ‘bridge to global capital’.

Deep interlinkages between mainland financial conditions and HK’s positioning as the experimental locus for RMB transnationalization, alongside London’s momentum in developing an offshore RMB market, have conditioned the ways in which each IFC’s infrastructural power has translated into broader transformation. Yet although macroeconomic policies such as capital account liberalization have a significant impact upon the headline growth of offshore markets, national macroeconomic and geopolitical policies are not necessarily in a zero-sum or conflictual relationship with IFC infrastructural power. The underlying process of institutional change through market-making enabled by infrastructural power continued to unfold despite higher-level trajectories of national state policy. This scalar differentiation in the nature of the agency exercised is made clear in the perspective offered by a senior HKMA official:

Governor Zhou Xiaochuan made a good analogy about RMB internationalization. It is proceeding in a wave-like path – sometimes there is up and sometimes there is down. But if you take a long-term perspective, they are moving in the direction of being more open and more liberalised. So when you look at just one year or two years, there of course will be some adjustment and some consolidation. But people are becoming more and more convinced and comfortable that this will be a process that will take decades to fully materialise. One of our jobs in the meantime is to manage the ‘ground-level’ aspects of this process and ensure it runs as smoothly as possible.Footnote3

Another HKMA official, in describing the BJ-HK relationship alluded to its potential synergies as well as tensions:

[Beijing authorities] are the main drivers of RMB internationalization, and the main players to give incentives for the use of RMB as an investment currency. And I think the Chinese authorities have done a pretty good job in continuing to emphasize their long-term strategic vision for the RMB as an international currency. […] So this helps us in our job and the process of putting in place market foundations, and cooperating with other authorities and financial institutions, because they also read the signs from higher on up.Footnote4

Yet this statement also makes clear the distinction between Beijing’s strategic policy ‘vision’ and the actual work undertaken by the HKMA in forging and utilizing transnational intergovernmental networks and relationships with private sector actors, within the parameters and ‘strategic vision’ established by national-level authorities.

In sum, the embeddedness of IFCs within broader national geopolitics and state economic policy illustrates three points. Firstly, that the infrastructural power of London and HK both catalyzed and then influenced the development of state policy by their respective governments towards RMB transnationalization, deepening Sino-UK financial relations. Secondly, that these state policies have also conditioned IFC infrastructural power amidst the uncertainty of shifting geopolitical and macroeconomic circumstances. And thirdly, that national state power and IFC infrastructural power have been exercised on different trajectories and at different scales within the RMB transnationalization process, such that despite broader political tensions between China and the UK, IFC authorities have continued the institutional and epistemic work underpinning the process of financial market-making.

Infrastructural power in the growth of london’s offshore RMB market

The London RMB market has experienced rapid growth since its foundation. By 2016, London had dethroned Singapore as the largest RMB clearing centre outside of China. Between 2017 and 2018, the dim sum bond market (for RMB denominated bonds issued and traded outside of China) grew by 260 per cent. In January 2019, the London market accounted for 36 per cent of total offshore RMB transactions and trading volumes for the RMB exceeded those for the pound against the euro for the first time. London is now the dominant offshore RMB hub outside of China.

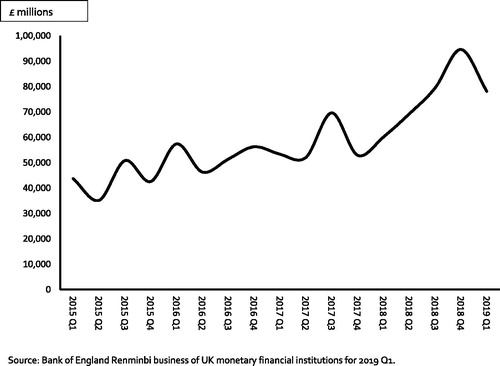

above shows the development of RMB-denominated foreign exchange trading in London. The market has experienced rapid growth, with total average daily turnover across the range of foreign exchange deals involving RMB almost doubling its volume between 2015 and 2019, increasing its average daily turnover from £43 billion to £78 billion. In global terms, this remains a tiny percentage (around 1.5 per cent) of average global forex turnover of $5.1 trillion daily in 2019.Footnote5

London’s rapid emergence as an offshore RMB hub has been contingent upon the infrastructural power exercised by the HKMA and the City of London as networked sites of financial market-making. Market-making has been underpinned by these institutions’ capacity to exercise a transnational political agency that is relatively insulated both from national-level political pressures and interstate diplomatic dynamics. For example, inter-governmental diplomatic relations between the UK and China froze in 2012 when UK Prime Minister David Cameron met publicly with the Dalai Lama. But despite these major diplomatic tensions, City Corporation representatives continued to be welcomed to government policy meetings across China,Footnote6 and at a time when the UK Government no longer had access, these links kept the project alive.Footnote7 This exemplifies the City Corporation’s ‘chameleon-like’ ability to both speak on behalf of the UK Government while simultaneously being identified as distinctively independent from UK national state institutions.Footnote8

The embeddedness of their agency within the broader national strategic economic interests detailed previously compelled the HKMA and the City Corporation to navigate these interests. This involved revealing and resolving potential obstacles that might be glossed over in diplomatic enthusiasm, as well as reconciling national-level differences by focusing on non-politicized aspects of market development. Additionally, deploying this agency has involved drawing upon their embeddedness within existing market structures. This has provided a focal point for private market actors to coalesce around in their efforts to influence policy decisions, while also enabling the countervailing capacity of political authorities to shape market perceptions and preferences regarding monetary affairs and policy decisions. Although market demands and state policy each played their role, the City of London was engaged more closely with the former whilst the HKMA more forcefully with the latter. In playing such a role, they have navigated the liminal zone between the bottom-up demands of local and transnational market actors, and the top-down imperatives of interstate contestation and cooperation.

The story of London’s offshore RMB market development is therefore one of the HKMA and the City of London operating at the nexus of market demands and national-state prerogatives.Footnote9 Early signs of differences in approach, expectations, and capacity between British and Chinese central authorities that could potentially give rise to conflict over the integration of RMB business into the City of London were recognized by the agencies in each financial centre (Subacchi & Huang, Citation2012). Following Hong Kong’s emergence as the institutional blueprint for offshore RMB market development, the London financial community rapidly began to mobilize efforts to attract and secure part of the nascent CNH market pool. Much of the initial enthusiasm came not from the central government, but from the City in concert with the London financial community.Footnote10 Those financial institutions with longstanding ties to the Chinese and Hong Kong markets and significant presence in contemporary offshore finance, in particular HSBC and Standard Chartered, recognized the nature of this opportunity early on.Footnote11 These major British-based transnational banks have since been at the forefront of cooperative efforts towards RMB transnationalization along the HK-London axis (Bank of England, Citation2013).Footnote12

Historical-institutional, cultural, and personal ties between London and Hong Kong created complementarities that helped facilitate networking, policy development, and market-making. A small group of influential financiers with ties to both the City and Hong Kong were instrumental to establishing networks of private bankers and city-level officials and connecting these networks to national policymakers. Xavier Rolet (formerly the CEO of the London Stock Exchange), Sir Gerry Grimstone (previously member of the China Group at City UK, and Sir Mark Boleat (then of the City Corporation Policy and Resources Committee) were particularly significant. These individuals used their personal status and influence to create ties with China, both within and beyond the remit of the UK Financial Services Trade and Investment Board, a national government-industry organization of which they each were key members.Footnote13 The more formal establishment of the Hong Kong-London forum was important because it prevented the existence and maintenance of these links becoming dependent on any one individual, institutionalizing cooperation. The City Corporation came to serve as the key adviser to the wider UK regulatory authorities and the BOE over issues of financial stability linked to RMB business, while also steering the UK Treasury’s policy towards maximizing London’s ability to deal in RMB (City of London Corporation, Citation2013). Epistemic factors were also significant, with the UK government limited in terms of its financial knowledge, resources and private sector experience. This led to a heavy reliance upon private sector knowledge, coordinated by City Corporation officials, to develop the processes on the ground (City of London Corporation, Citation2015a).

Both the significance and the nature of IFC infrastructural power are evident in the Sino-UK negotiations over institutional arrangements for fostering offshore RMB expansion. Despite the enthusiasm from the private sector, the Bank of England was reluctant to sign a bilateral currency swap agreement, which had been a core element of the initial HK strategy that was replicated in the Taipei and Singaporean cases. This was in contrast to either the Treasury, or the City of London, which had their respective reasons for supporting a currency swap deal. Whilst the Treasury was concerned with the broader political implications of the race to secure early-mover advantage, the City Corporation was responding to strong calls from the London financial community.Footnote14 Financial firms were concerned that they were going to be left behind by Singapore and potentially also Frankfurt if they did not recognize that market development was contingent upon institutionalized measures to increase liquidity and facilitate payments and clearing.Footnote15 Cooperation between London and Hong Kong unfolded within a broader context of IFC and national-level competition to attract international business.

As the momentum swelled in favour of gaining RQFII status and securing a London-based RMB clearing bank to deepen access to RMB assets, the City of London was actively mediating between these diverse stakeholders and their respective interests.Footnote16 In October 2013 London secured the first foreign RQFII quota ahead of regional centres such as Singapore, Seoul, and Taipei or other leading IFCs such as New York. Political relations rather than trading volumes or volume of RMB deposits were instrumental, and the City Corporation’s post-crisis pressure upon UK national policy as well as efforts to nurture relational proximity directly with Chinese policymakers drew in a wide range of private and public actors.Footnote17 Institutional developments subsequently outpaced the growth in RMB trading volumes as higher-order political volatilities buffeted both the Sino-UK relationship as well as China’s broader external liberalization, yet key corporate actors in London continued to support the City Corporation’s efforts for continued momentum in establishing the institutional foundations for London’s RMB business.Footnote18

The PBOC was reluctant to establish an offshore RMB clearing bank in London, since the historical linkages between London and Hong Kong meant that it was initially seen as less necessary for London to receive its own clearing bank. The HKMA sought to convince British officials and the City of London that they could trust Hong Kong to provide the necessary clearing and payments infrastructure for a burgeoning London RMB business.Footnote19 This included extending the operation of the RMB payments system by five hours to facilitate RMB clearing through HK from London and European time zones. It took over two years to reach agreement on these institutional and policy aspects of monetary cooperation, and the 2014 appointment of CCB as the clearing bank was initially intended to complement the existing clearing and settlement infrastructure for RMB trading in Hong Kong as well as provide London with the necessary institutional foundations for a further expansion of its offshore RMB markets.

Throughout this process of market institution-building, the HKMA and the City were well aware of the need for an integrated and holistic approach to market development, in order that ‘the two governments, their regulatory institutions, and the market participants understand each other’s objectives’ (City of London Corporation, Citation2013, p. 13).Footnote20 The UK-China Economic and Financial Dialogue held in September 2011 laid the foundations for the City to launch the City of London Initiative on London as a Centre for Renminbi Business, encompassing a vision of London developing as the ‘Western hub’ for the international RMB market, complementing Hong Kong as the pre-eminent offshore RMB centre (City of London Corporation, Citation2013). Conversely, the ‘Hong Kong – London Forum’ was established in January 2012 by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority to promote cooperation on the development of offshore RMB business. The forum meets twice a year, with a focus upon the joint development of clearing and settlement systems, on improving CNH liquidity overseas, and on developing an increased range of CNH products.

The City Corporation’s and the HKMA’s market embeddedness not only helped catalyze these institutional initiatives, but more importantly has played a central role in their operation and effectiveness, with evidence of close consultation on how to reconcile market needs in the areas of trade settlement, capital raising, and the issuance of investment products. The depth of private sector involvement in shaping regulatory and policy choices is apparent in the sophistication of a complex network of working groups established by the City, supporting London’s RMB business development (City of London Corporation, Citation2016b; Citation2016a) through public-private sector partnerships active since 2010 not only in London but via the City’s representative offices in Beijing, Hong Kong, and mainland China (City of London Corporation, Citation2015b). In the post-crisis efforts to construct an offshore market and drum up support for RMB business, the role of these offices changed from that of ‘reactive/sounding board’, to ‘putting them into action in terms of really pushing forward … City of London agendas specifically in those regions’.Footnote21

In this sense, the HKMA and the City of London have to a large extent seen their role as facilitating the growth of RMB business through engaging with the market itself, as distinct from the higher-level policy strategies adopted at the national level. As a senior HKMA manager observed, ‘as a regulatory agency but also as Hong Kong’s “financial representative”, we have to do a lot to manage the demands of different stakeholders.’Footnote22 This dynamic is underscored in the views of the HK financial community:

The HKMA is very active in responding to the needs of the HK financial community. They know that they have to work hard to maintain HK’s competitiveness as a financial centre. The Mainland financial industry is developing rapidly, and also the global financial landscape is changing too. They want to preserve HK’s unique market knowledge and position, but they need to do that whilst listening to Beijing at the same time.Footnote23

Yet crucially, as this examination of the development of London’s offshore RMB markets has illustrated, this aim of facilitating market-making by engaging with private sector actors also necessarily involves the deepening and leveraging of intergovernmental networks. The infrastructural power of Hong Kong and London has enabled the sewing together of social, political, and economic connections in ways that neither interstate politics nor private economic networks permit. As the following section discusses, this has implications for how we think about global monetary change and transformation.

Infrastructural power and implications for structural change

Our empirical findings illustrate the discrepancy between trajectories of RMB transnationalization when viewed at different spatial scales. Transnational currency market-making is neither purely a function of macroeconomic developments nor policy choices made in national capitals. Rather, the infrastructural power of London and Hong Kong was instrumental in establishing the institutional foundations of a new transnational financial market in offshore RMB. In this section we examine the implications of this market-making process for broader patterns of structural change in the IMS in two ways. First, concerning the empirical question of a shift in global monetary hierarchies, we suggest that the market-making role of IFCs affects the ‘tipping point’ at which networked externalities catalyze rapid transformative changes in the usage of a currency relative to another. Second, we explore the implications of IFC agency for structural monetary power. We contend that the role of IFCs in underpinning monetary change also creates new points of vulnerability and complexity for sovereign state power, such that increasing currency usage does not neatly reflect rising global monetary influence.

Our point of departure is our initial assumption that even without either a stark decoupling of regional economic spheres of influence or the wholesale catastrophic breakdown of the international monetary and financial system, systemic change will occur in the future. This constitutes a non-linear process in which network externalities may retard change until a tipping point is reached that catalyzes rapid transformation (see He & Yu, Citation2014). Chinn and Frankel (Citation2005) attempted to account for such network inertia in their speculative modelling of the Euro’s potential challenge to the Dollar, but did not seek to identify the precise point at which a ‘tipping phenomenon’ (Citation2005, 16) would take place. Reluctance to engage in such forecasting is sensible. We similarly point to how (without predicting when) the exercise of IFC infrastructural power can be expected to accelerate the onset of such a tipping point in a non-linear process of systemic change.

The concept of tipping points first entered social science lexicon in the 1970s to describe the decisive moment when new black entrants into urban communities would trigger white-flight (Schelling, Citation1971). It has since been generalized as a social scientific principle by Gladwell (Citation2006), referring to the rapid and viral spread of transformative social dynamics. Tipping points have three key characteristics. Firstly, they represent a contagious logic of social behavioural change. Secondly, they exhibit a multiplier effect whereby small or incremental changes can suddenly have big impacts. And finally, the pattern of transformation is rapid. Of the three characteristics, Gladwell (Citation2006) points to the rapidity principle as the most significant.

How might we apply this concept to international monetary dynamics? Firstly, financial markets often behave in accordance with such networked logics of contagious behaviour. Changing sentiments can drive widely reproduced behavioural decisions to buy or sell particular currencies. Secondly, small or incremental changes, like the gradual development of offshore RMB markets through regulatory and institutional adjustment, can suddenly have a big impact – setting in place the foundations for a quantitative take-off in market usage of a specific currency. Finally, there is the potential for rapid transformation in terms of the liquidity, velocity, and volume of market transactions adjusting in response to changing market or political sentiments. Our application of tipping points echoes Gladwell’s theorization, but departs from it in one critical respect - we draw attention to the institutional and qualitative foundations of quantitative tipping points. Whereas Gladwell’s account takes for granted the institutional foundations that enable tipping points, we highlight how quantitative take-offs in socio-economic phenomena are both potentially hastened and hindered by qualitative-institutional factors.

The role of tipping points within the IMS can be illustrated through the rise of the Eurodollar market. US dollars deposited offshore in the City of London were initially used by British banks to finance international trade, overcoming restrictions on the use of sterling. Offshore Eurodollar rates became tightly interdependent with US onshore rates from 1966, extending the international reach of US monetary policy while increasing sensitivity to the London market (Green, Citation2016). Eurodollar transactions experienced a quantitative take-off from 1973 as OPEC states quadrupled oil prices and recycled their surging dollar revenues through Western banks. This boom in offshore dollar liquidity intermediated through London marked a tipping point in the international usage of the offshore dollar with governments borrowing heavily to cover the rising cost of oil imports (Altamura, Citation2017: 99-100). It coincided with a period of international monetary disorder during the 1970s, with the delinking of the dollar from gold, the shift to floating rates, and discussions over reintroducing capital controls. The infrastructural foundations of the Eurodollar market ensured that international demand for dollars and momentum for financial liberalization continued to grow despite wider monetary instability, cementing the dollar’s hegemony and generating vast flows of hot money that undermined sterling’s international standing by fuelling devaluations in 1967 and 1976 (Dickens, Citation2005: 216).

With the qualitative foundations of the offshore RMB market now well-established, a rapid quantitative expansion of market volume and velocity in the future is possible. This is an important difference from the pre-crisis IMS, in which such socially embedded networks and the institutional foundations for offshore RMB trading did not exist. IFC infrastructural power has increased the potential for political or economic events to constitute a critical juncture in catalyzing systemic change – with rapid quantitative shifts in currency usage. In sum, the effect of IFC infrastructural power is not merely to stimulate the quantitative expansion of the RMB’s transnational usage, but also to establish qualitative institutional foundations that shift the threshold for a ‘tipping phenomenon’ to take hold, whether this be triggered by a significant shift in China’s capital account policy, or dramatic deterioration in the economic fundamentals of other competing currencies.

IFC infrastructural power in RMB transnationalization also has consequences for the broader development of China’s monetary power. The construction of a transnational axis of offshore RMB markets points to the gradual emergence of an institutionalized nexus for Chinese global structural power. At the same time, the establishment of institutional foundations within systemically significant Western financial markets such as the City of London is important. In such circumstances, the exercise of infrastructural power not only increases the potential for deeper structural change, but by facilitating the reorientation of monetary networks through an existing dominant Western IFC rather than outside it, potentially lessens the geographical and geopolitical volatility of such change. London’s greater integration with circuits of Chinese finance represents a partial reorientation of the Anglo-American financial market heartlands, via the City’s pivot towards China and away from a euro-Atlantic financial space, rather than their displacement through a territorial relocation of globally oriented financial infrastructure within Asia itself.

This is not, then, a unidirectional process of change. In his account of US monetary power, Konings (Citation2011) argues that the construction of the dollar-oriented financial infrastructure did not simply intensify the governance power of the American state. Because of the indirect nature of infrastructural power, beyond more direct forms of authority and regulation, its expansion can create contradictions and tensions for existing institutional governance capacities (see also Fichtner, Citation2017). For Konings, these constraints emerge from the ‘contradictions’ of internationalising finance within a spatially under-theorised international market order. Yet homing in on the political context and agencies exercised by IFCs offers a more nuanced view of the impact of infrastructural power for the extensity and vulnerability of Chinese structural power within global finance.

These networks are janus-faced and multi-directional in terms of their bearing upon Chinese monetary power. On one hand, they facilitate the greater international influence, supply of, and demand for China’s currency within international markets, with all the attendant benefits associated with this. But on the other hand, due to the sociospatial extensity of these networks and their dependency upon the cooperative efforts of multiple actors involved in forming and sustaining them, they create new points of political vulnerability, contingency, and dependency. When monetary sovereignty is practiced through transnational networks, and across spaces connected by privileged nodal points, this sovereignty is not simply a crude multiplier of structural power. It is simultaneously both more extensive and yet more constrained by its reliance upon the authority of multiple actors across multiple dynamic scales. The paradox of increased Chinese structural power through offshore RMB markets, then, is that its development relies upon pooling sovereignty through increased concertation of multiple authorities. Rising Chinese monetary influence comes with the downside of decreasing sovereign control. This exemplifies the limitations of Mann’s theorization – it assumes a logic of increasing territorial centralization and boundedness that does not capture the specific nature or implications of the infrastructural power of IFCs.

Recent political dynamics both within and between China and the UK demonstrate the vulnerability and contingency of transnational offshore RMB networks. They raise questions about the capacity for transnational networks of IFC cooperation to survive within a context of sharpening geopolitical rivalry, economic nationalism, and domestic tensions surrounding the status of the City and Hong Kong as IFCs embedded within national political structures. Relations between each respective IFC and their host nation-states have become more fraught in recent years. In the UK, the vote for Brexit and the disorderly process of EU-secession has prohibited the arrangement of a framework to govern the post-Brexit relationship between the City and European financial markets. These have deepened the climate of uncertainty surrounding the City’s relationship to European financial markets and challenged the long-standing presupposition of UK government support for the City’s international role. At the same time, Brexit has prompted the City Corporation to intensify efforts to proactively promote UK financial interests abroad by using its extensive network.Footnote24

Regarding China, Xi Jinping’s project to centralize power and authority within the CCP, buoyed by China’s strong post-crisis growth and increased international influence, has provoked increasingly sharp political tensions between the Mainland authorities and Hong Kong. The ‘one country, two systems’ framework has looked evermore fragile in the face of Xi’s tightening grip on power. Widespread popular resistance to Beijing’s political domination began with the Umbrella movement in 2014. Hong Kong’s resistance to the centralization of power intensified with huge protests against a proposed extradition law that would allow Hong Kong residents to be subject to Mainland legal proceedings. Hong Kong’s Chief Executive, Carrie Lam, eventually withdrew the proposed bill. But the deepening political rift between Hong Kong residents and Mainland China, and the fragility of the ‘one country, two systems’ arrangement, raises existential questions about Hong Kong’s future as a liberalized IFC.

As we have shown, the institutional sources of IFC capacity and agency have deep historical foundations. Nonetheless, if the mood and dynamics of national and global politics become sufficiently hostile to the elite capitalist cosmopolitanism required to sustain transnational IFC networks, then the infrastructural foundations of the offshore RMB may be threatened. Our analysis suggests that this is, though, unlikely. Dense transnational elite linkages fostered through IFC-led financial integration act as an important centripetal force that can stabilize global financial linkages during a time of rising nationalism and geopolitical rivalry. Although political unrest in Hong Kong has raised diplomatic tensions between the UK and China, with China decrying the UK’s ‘gross interference’ in Hong Kong, previous examples suggest that cooperation around market-making can proceed despite these tendencies towards sharper diplomatic tensions and a broader cooling of the Sino-UK relationship in recent years (Blitz, Citation2019). This is precisely because of the sub-national agency of IFCs and their unique positioning in meshing together public authority and private interests – acting on behalf of but distinct from national state authority.

Concluding remarks

In this article, we have shown how viewing the global financial order through a more multi-scalar lens captures different levels and trajectories of monetary change. This allows us to apprehend the linkages between incremental and systemic dynamics of transformation. Through the empirical analysis of the City of London and Hong Kong’s dealings with one another, private market actors, and national state agencies in constructing offshore RMB markets, we demonstrate the significance of IFCs as sites of infrastructural power. This power can be exercised both in alignment and in tension with national monetary statecraft promoting currency internationalization. On the basis of these findings, we more speculatively propose that these processes of transnational market-making facilitate the onset of ‘tipping points’ in global monetary change, as well as extend and dilute state monetary sovereignty, thus creating new sources of monetary vulnerability while simultaneously broadening state structural power.

These cooperative efforts indicate changing East-West interactions within the global economy. China is working through London’s financial markets to enhance its global reach, while London looks to China’s rising financial power to maintain its status as a premier IFC. In the process, the dollar-order is being gradually decentred by shifting geographical patterns of financial integration. Although in quantitative terms the dollar is the undisputed dominant international currency and will remain so for the foreseeable future, the processes of IFC-led market making we have identified point to qualitative shifts within the infrastructure of global financial markets that are setting down deep roots for potential future growth of the RMB’s international role.