Abstract

How do governments allocate the burden of adjustment of reform programs sponsored by international financial institutions? While the political economy literature is ripe with theoretical arguments about this issue, we have a limited empirical understanding of the distributional effects of these programs, except for a few informative case studies. We argue that governments allocate adjustment burdens strategically to protect their own partisan supporters while seeking to impose adjustment costs upon the partisan supporters of their opponents. Using hitherto under-explored individual-level Afrobarometer survey data from 12 Sub-Saharan African countries, we employ large-N analysis to show that individuals have consistently more negative evaluations and experiences of IMF structural adjustment programs when they supported opposition parties compared to when they supported the government party. Partisan differences in evaluations are greater when governments have greater scope for distributional politics, such as in the public sector and where programs entail more quantitative performance criteria, which leave governments discretion about how to achieve IMF program targets. Negative evaluations are also more prevalent among ethnically powerless groups compared to ethnically powerful groups. These results emphasize the significant role of borrowing governments in the implementation of IMF-mandated policy measures. They also stress the benefits of reducing the number of IMF conditions in limiting the scope for harmful distributive politics.

Introduction

Distributive politics is a ubiquitous fact of political life: governments of all types seek to reward their supporters through a range of policy choices (Kramon & Posner, Citation2013). However, we know less about how structural adjustment programs (SAPs) mandated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—often triggered by economic crises and designed to resolve them—affect government behavior towards different partisans. While scholars analyzed macro-level effects of IMF programs on a diverse set of outcomes such as economic growth, debt, income inequality, repression, political stability, conflict, state capacity, education spending, and health (Abouharb & Cingranelli, Citation2007; Dreher, Citation2006; Ortiz & Béjar, Citation2013; Pettifor, Citation2001; Pion-Berlin, Citation1983; Reinsberg et al., Citation2019; Stubbs et al., Citation2020; Stubbs & Kentikelenis, Citation2018; Vreeland, Citation2003), we know little about the micro-level perceptions and distributive consequences of such programs. This omission is problematic because many IMF-induced reform programs have been met with fierce resistance, leading to civil strife, political instability, the risk of a coup and economic decline (Abouharb & Cingranelli, Citation2007; Casper, Citation2017; Hartzell et al., Citation2010; Keen, Citation2005; Walton & Ragin, Citation1990). Given the role of distributive conflict as a precursor of political instability, we need to better understand the local distributional effects of IMF policy pressures and the strategic behavior of governments in dealing with the Fund as a purveyor of neoliberal economic reform.

Against this background, we turn to the individual perceptions and experiences of the distributional effects of IMF programs in developing countries. We argue that governments use their discretion within such programs to favor individuals and groups aligned to them to the detriment of those individuals and groups whose allegiances lay elsewhere. Facing pressures to comply with IMF-mandated reforms, we expect governments to engage in more intensive distributional politics than they would otherwise do. They will lump adjustment burdens such as civil-service retrenchment, tax hikes, and spending cuts on opposition supporters while seeking to protect their own supporters as much as possible. As a result of such distributional politics, we expect to find highly unequal perceptions and experiences of the same country-level IMF program.

Our argument has some precedence in the literature on patronage politics (Brierley, Citation2021; Carlitz, Citation2017; Ejdemyr et al., Citation2018; Poulton & Kanyinga, Citation2014) and the partisan allocation of aid funds (Anaxagorou et al., Citation2020; Briggs, Citation2014; Dreher et al., Citation2022; Jablonski, Citation2014; Lio Rosvold, Citation2020), which establish that governments skew the distribution of public goods towards supporters and away from groups who support other political parties. Transferring these insights to the context of IMF programs, we examine how governments seek to use IMF programs for their political advantage by distributing the monies and opportunities associated with these programs to their supporters while lumping the pain of adjustment amongst supporters of the opposition. As a result, we expect government supporters to have markedly different evaluations and experiences of IMF program lending compared to opposition supporters even when considering that partisan supporters will view their government more favorably and opposition voters will hold more negative views of the incumbent administration (Evans & Andersen, Citation2006; Fernández-Albertos et al., Citation2013; Popescu, Citation2013).

To test our argument, we use hitherto under-explored data from the first wave of the Afrobarometer covering 21,531 individuals from 12 Sub-Saharan African countries in 1999–2001—a peak point of IMF SAPs in the region. Using multivariate regression analysis, we find that evaluations of the economic effects of IMF SAPs differ significantly between individuals who voted for the incumbent party and individuals who voted for the political opposition. Specifically, the probability that individuals consider themselves worse off due to the IMF SAP is 54.4% for individuals who supported the winning party in the last election but 70.2% for individuals who supported the losing party. These differences are more pronounced where governments have control over the allocation of resources such as for public-sector workers and where IMF SAPs leave governments greater scope for allocating adjustment burdens as they see fit. Importantly, because we control for predispositions of different partisans to evaluate the incumbent administration differently, our findings are unlikely to be driven by mere perceptions. In countries where politics is organized along ethnic power relations, our alignment argument manifests itself along ethnic lines, too. We find evidence that opposition supporters endure increased hardship relative to government supporters in the context of IMF programs. These results demonstrate heterogeneous perceptions and experiences of IMF SAPs and identify partisan and ethnic politics as important drivers of such effects.

Our article makes two contributions to debates in international relations, international political economy, and comparative politics. First, we extend the distributive politics literature to studying an important contextual factor: how distributive politics evolves under IMF programs. Our individual-level approach nuances existing macro-level cross-country IPE literature, extends the literature on the local political economy of foreign aid (Anaxagorou et al., Citation2020; Briggs, Citation2014; Dreher et al., Citation2022; Jablonski, Citation2014; Lio Rosvold, Citation2020) and the sub-national distributional politics literature (Brierley, Citation2021; Carlitz, Citation2017; Ejdemyr et al., Citation2018; Poulton & Kanyinga, Citation2014) to understand government efforts at distributional politics in the face of IMF program lending demands.

Our second contribution is to the vast literature on the socio-economic effects of IMF SAPs (Blanton et al., Citation2018; Dreher, Citation2006; Lang, Citation2021; Marchesi & Sirtori, Citation2011; Öniş, Citation2009; Reinsberg et al., Citation2022; Woods, Citation2006). We complement existing macro-level evidence with micro-level evidence from Afrobarometer that allows us to unpack the mechanisms of distributive politics in the implementation of IMF SAPs. Our findings therefore demonstrate how global forces interact with local politics to affect distributive outcomes in developing countries. Where IMF literature has considered the role of public opinion, rather than assessments of elites such as financial market actors (Breen & Doak, Citation2021; Goes, Citation2022; Goes & Chapman, Citation2021), it has done so from an aggregate perspective—conceiving public opinion as a constraint to government decision-makers (Henisz & Mansfield, Citation2019; Shim, Citation2022)—rather than examining heterogeneous individual perspectives about IMF SAPs within the public. While a small literature has examined the determinants of public opinion towards the IMF and other international organizations in general (Breen & Gillanders, Citation2015; Dellmuth & Tallberg, Citation2021; Edwards, Citation2009; Kaya et al., Citation2020), ours is the first to focus on public opinion on IMF SAPs while allowing for opinions to diverge as a result of distributional politics.

Theoretical framework

Our argument draws together three hitherto unconnected strands of literature. First, the literature on patronage politics portrays governments as strategic actors that use rewards and punishments to retain office (Kitschelt & Wilkinson, Citation2007; Kopecký et al., Citation2012; Kramon & Posner, Citation2013; Panizza et al., Citation2018), but has not answered whether and how submission to IMF SAPs affects the scope for distributional politics by governments. Second, the political economy literature on IMF SAPs has examined the causes and consequences of IMF SAPs for a range of socioeconomic outcomes, as well as conditions for country compliance with IMF SAPs (Reinsberg et al., Citation2021; Citation2022; Rickard & Caraway, Citation2019; Stone, Citation2002). Much of this work is based on large-N country-level analysis, while some earlier work uses case studies to analyze the distributive politics of IMF program implementation (Haggard & Kaufman, Citation1992; Nelson, Citation1984; Reno, Citation1996). A key limitation is the lack of micro-level evidence on the perceptions and experience with IMF SAPs. Third, remedying this gap, we take inspiration from the burgeoning sub-national foreign aid literature, which shows that governments can use aid for political gain (Briggs, Citation2014; Dreher et al., Citation2022; Isaksson & Kotsadam, Citation2018; Jablonski, Citation2014). While this literature has focused on how governments allocate the spoils of aid as a source of unearned income, it lacks comparable analysis for how they allocate the burdens of adjustment.

The politics of alignment

A voluminous literature examines patronage politics where politicians provide a pick-and-mix range of goods including private goods, club goods, and programmatic ones to reward existing supporters and in some cases coax new ones to the fold (Harris & Posner, Citation2019; Kitschelt & Wilkinson, Citation2007; Kramon & Posner, Citation2013; Panizza et al., Citation2018). At the heart of patronage is a clientelist exchange whereby incumbents provide goods to their supporters, who continue to reward incumbents electorally. These exchanges are especially relevant in information-poor contexts of developing countries, where they guarantee voters access to benefits that they may not obtain otherwise in elections where politicians make programmatic promises (Chandra, Citation2004; Kitschelt & Wilkinson, Citation2007; Van de Walle, Citation2001).

Patronage politics is particularly prominent in Sub-Saharan Africa. Built upon inter-elite bargains under authoritarian rule (Joseph, Citation1987; Van de Walle, Citation2001), it remained an important tool for politicians after democratization (Bratton & van de Walle, Citation1997; Kopecký et al., Citation2012; Van de Walle, Citation2007). Patronage exists across different institutional contexts, such as federalist states and unitarist states, while extending well beyond Sub-Saharan Africa, to include countries in Europe and Latin America (Kopecký et al., Citation2016; Oliveros, Citation2021; Panizza et al., Citation2018; Szarzec et al., Citation2022).

In the African context, the politics of alignment is often also along co-ethnic lines, as the existing distributional literature suggests (e.g. Carlitz, Citation2017; Ejdemyr et al., Citation2018; Poulton & Kanyinga, Citation2014). Previous research argues that ethnicity is a heuristic for politicians to use when doling out benefits to groups and for individual voters to coalesce around to make their voices heard (Chandra, Citation2004). Patronage politics can occur through civil-service appointments (Brierley, Citation2021), infrastructure projects (Harding, Citation2015), and welfare programs (Harris & Posner, Citation2019; Kramon & Posner, Citation2013). For example, ‘political parties in Ghana and South Africa use a sizeable part of the public sector as an arena for patronage appointments’ (Kopecký, Citation2011, pp. 721–722). While patronage extends deep into the civil service of some African countries, it is remarkably prevalent in different parts of the civil service and across levels of seniority (Kopecký, Citation2011, p. 722).

Politicization of senior appointments in the public sector enables political leaders not only to reward their allies with offices they can use to enrich themselves but also to allow these individuals to reward their own networks in clientelist exchanges (Van de Walle, Citation2001).

Patronage politics flourishes where governments have access to significant sources of unearned income. A burgeoning literature on the local distributional politics of foreign aid finds that governments engage in distributional politics, with political leaders divvying up aid to their supporters (Briggs, Citation2014; Dreher et al., Citation2022; Isaksson & Kotsadam, Citation2018; Jablonski, Citation2014). For example, incumbent leaders direct aid funds to their birth regions, especially when they face competitive elections (Dreher et al., Citation2022, p. 165). They also bias the allocation of project aid from multilateral development banks towards constituencies with higher vote shares for the incumbent and those that share the same ethnicity (Jablonski, Citation2014, p. 295). Similar patterns of behavior were found in earlier case-study research finding evidence of biased allocation of public goods along partisan lines as part of the structural adjustment process (Herbst, Citation1990; Keen, Citation2005; Reno, Citation1996). We contend that governments make the same distributional choices highlighted in the local political economy of foreign aid literature in the areas where they retain discretion in compliance with IMF mandates.

Our key takeaway from this literature is that politicians have a good idea of who their voters are and where they live, that they act to reward them individually. They target spending geographically, even within their own constituencies, to reward voters for their collective support (Chandra, Citation2004; Harris & Posner, Citation2019; Oliveros, Citation2021). Given this level of information that government parties have, we expect that they also know who to target with the burden of adjustment when facing austerity pressures. To date, however, there is limited evidence on how governments who engage in patronage politics respond to pressures for adjustment. In their ground-breaking volume, Kitschelt and Wilkinson (Citation2007, p. 3) note that governments have resisted the attempts of international financial institutions to reduce the size of their states because it ‘threatens their patronage and hence their ability to win elections and stay in power’. However, this view is too simplistic, contradicting the evidence that governments have complied with most IMF-mandated reforms. To better understand how IMF SAPs affect patronage politics, we first need to understand the purpose of these programs.

The politics of alignment under IMF adjustment programs

Countries in dire economic straits often turn to the IMF—an international financial institution that provides emergency loans in exchange for government commitments to fiscal austerity and structural reforms (Babb, Citation2013; Stone, Citation2002; Stubbs & Kentikelenis, Citation2018; Vreeland, Citation2003). IMF adjustment programs de-regulate, privatize state assets, and retrench the state—to weaken patronage networks, encourage export-led economic growth, and benefit farmers in the rural economy (Bates, Citation1981; Friedman, Citation2000; Vreeland, Citation2003; World Bank, Citation1981). Much of the literature on IMF SAPs is at the country-level (Stubbs & Kentikelenis, Citation2018; Vreeland, Citation2003; Walton & Ragin, Citation1990), examining a range of socio-economic outcomes such as economic growth, debt, health, income inequality, government spending, repression, political stability, and conflict (Abouharb & Cingranelli, Citation2007; Dreher, Citation2006; Ortiz & Béjar, Citation2013; Pettifor, Citation2001; Pion-Berlin, Citation1983; Reinsberg et al., Citation2022; Stubbs et al., Citation2020; Stubbs & Kentikelenis, Citation2018).

A complementary political economy literature draws on case studies to cast light on the politics of implementation (Haggard & Kaufman, Citation1992; Nelson, Citation1984; Reno, Citation1996; Waterbury, Citation1992). Following their lead, we argue that political leaders face a set of potentially competing demands from different individuals and groups: they need to credibly satisfy the IMF to keep funds flowing; they need to respond to organized lobbies; and they need to enact policy choices to garner themselves enough support for re-election or to retain political power. The last is of particular interest to us.

Considering their continued incentives for patronage politics, we expect governments will lump adjustment burdens on opposition supporters while trying to protect their own supporters. If politicians know who to hire and where to spend money to reward their supporters—as demonstrated by the literature on patronage politics and the local politics of foreign aid—they will also know who to fire in the public sector and which public services to cut to target individuals and constituencies who do not support them.

An important consideration is whether governments have enough discretion for distributive politics when they are under IMF tutelage. While cross-country research has examined government discretion in the adjustment process (Beazer & Woo, Citation2016; Stone, Citation2002; Stubbs et al., Citation2020; Vreeland, Citation2003), conventional wisdom would expect decreasing scope for distributive politics when governments need to make cuts. However, this overlooks that governments not only allocate benefits but also costs.

Even though IMF SAPs regularly contain macroeconomic targets for tax revenue, public spending, and public-sector employment, they do not specify which groups and individuals to retrench in the public sector or who to target with cuts to welfare spending. Governments thus retain some discretion in how they comply with IMF conditions and use this flexibility for their own political advantage. By targeting their political opponents and opposition supporters with the costs of adjustment, governments under IMF programs can still fulfill adjustment targets. If decision-makers utilize this process to protect and even possibly reward their own supporters whilst placing the burdens of adjustment on opposition supporters, we should observe a divergence in perceptions and experiences of IMF SAPs across partisan lines. Our first hypothesis reads as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Partisan supporters of the government view the consequences of IMF program lending less negatively than partisans who supported the opposition.

Hypothesis 2: The partisan gap in IMF program evaluations is particularly strong among individuals in public-sector employment.

By contrast, quantitative conditions leave decision-makers a good deal of discretion about how to reach particular targets, such as reducing budget deficits, increasing revenues, and reducing the number of state employees (Stubbs et al., Citation2020). Therefore, decision-makers retain discretion over budget decisions, such as imposing new taxes, de-funding public services, or dismissing public-sector employees. Governments will use this discretion to benefit individuals in government-supporting areas, whilst harming those in opposition strongholds (Appiah-Kubi, Citation2001; Campos & Esfahani, Citation1996). The discretion over how to achieve quantitative performance targets means that decision-makers can incorporate domestic political considerations into the negotiation, design, and implementation of IMF-sponsored adjustment measures to bolster their own political advantage. We would expect the partisan gap in individual experiences of IMF lending to be greatest when governments are under IMF SAPs with more quantitative conditions, which we characterize as high-discretion programs. These high-discretion programs leave governments the most room to engage in distributive politics. This leads to our third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: The partisan gap in IMF program evaluations is particularly strong when IMF programs leave governments more discretion for distributive politics.

Case-study evidence on the distributional politics of adjustment

We provide evidence on our proposed mechanisms with an inter-temporal case study of Ghana. Our subsequent large-N analysis suggests that Ghana reflects an average case from the Afrobarometer sample, given that similar patterns of diverging IMF SAP evaluations and partisan politics occur in Malawi, Tanzania, and Zambia. A case-study approach allows us to overcome a key limitation of the survey data: they only represent a snapshot in time. Drawing on a rich body of literature on Ghanaian politics (Abdulai & Hickey, Citation2016; Appiah-Kubi, Citation2001; Brierley, Citation2021; Handley, Citation2007; Harding, Citation2015; Ninsin, Citation1998; Youde, Citation2005), we exploit inter-temporal variation in the Ghanaian case due to a change in government while the country was under IMF assistance. This allows us to demonstrate how the allocation of adjustment burdens across different societal groups changes as the party controlling the government changes.

We find that both the Rawlings government and the subsequent Kufour administration tried to use IMF funding to protect their own supporters. Rawlings advantaged party elites in the privatization and liberalization process while rolling out a social support package that disproportionally benefited his own supporters. Kufour, who had his support base among local entrepreneurs, implemented a raft of pro-business reforms and regional infrastructure projects to reward long-standing areas of support and swing states which helped him gain office.

With the backing of the Fund, Rawlings turned the state-controlled economy established under Kwame Nkrumah into a liberal market economy, involving privatization of SOEs and the liberalization of the Ghanaian economy to foreign investors. These reforms continued with the Kufour administration who submitted the country under the HIPC initiative, which linked debt relief to further conditionality. From this perspective, both administrations complied with the IMF’s reform agenda, whilst having different support bases.Footnote1

Adjustment policies of the Rawlings administration

For two decades, Ghana was ruled by Jerry Rawlings, first as military chief (1981–1993) and then as elected leader of the National Democratic Congress (NDC) (1993–2001). Facing re-election for the first time, Rawlings asserted himself through distributive politics. Ninsin (Citation1998, pp. 226–227) astutely observes how Rawlings used the state to reward would-be supporters with the distribution of limited national resources:

Rawlings and his party men won the 1996 elections because the electorate perceived them as the ones who control the scarce resources needed for development of their communities. They were also the ones with demonstrable capacity and commitment to deliver or punish communities that do not show sufficient support at the polls.

Privileging party elites in the privatization process

Rawlings utilized the IMF-mandated divestiture process—the transfer of SOEs into private hands—for political gain, through a variety of questionable practices (Appiah-Kubi, Citation2001). For example, the Divestiture Implementation Committee (DIC), the government agency created to handle the process, never publicized the initial divestiture transactions—interested parties were simply requested to contact the DIC or the relevant sector ministry. Appiah-Kubi (Citation2001, p. 224) notes that this lack of transparency led to ‘widespread allegations of opportunistic behavior by bureaucrats and top government executives eager to cream off sizeable rents from their control of SOEs’.

The period 1989–1999 saw over 70% of Ghana’s SOEs privatized (ibid: 211). Between 1991–1998, divestiture receipts on average accounted for 8.5% of total government revenue (ibid: 216). While this revenue stabilized the Ghanaian economy, it also allowed the government to stabilize taxes and helped Rawlings maintain partisan support. As Appiah-Kubi (Citation2001, p. 217) describes: the forgoing of tax increases provided a ‘congenial sociopolitical atmosphere that paved the way for the smooth transition from military rule to democratic multi-party governance’.

Privatization and the maintenance of public sector salaries

Privatizing SOEs not only provided a significant source of revenue for the government during the 1990s but also increased employment rates and wages in previously moribund SOEs (Appiah-Kubi, Citation2001, p. 214). The Rawlings administration used its control over the public sector to reward those working in it, despite being under pressure from the Fund to bring tax receipts and spending closer into balance. In spring 2000, amidst an IMF program, the Rawlings government announced via the state radio a ‘20-percent across-the-board salary hike for civil servants, teachers, nurses and members of the judiciary’ (The New Humanitarian, Citation2000). This did not go unnoticed by the Fund. In late May 2000, the IMF representative to Ghana, Girma Bergashaw said to Reuters he was ‘uncomfortable with [the] 20% wage increase announced this week by the government for some categories of public sector workers’ (GhanaWeb, Citation2000). These sizeable salary increases dovetailed with other policies promoted by the Rawlings administration which sought to privilege public-sector workers, providing some evidence that the government sought to protect particular groups from the burdens of adjustment.

Support packages and the protection of particular groups from the burdens of IMF adjustment

The government’s distributional approach to IMF program lending followed a long-standing policy that was already evident in its Program of Action to Mitigate the Social Costs of Adjustment (PAMSCAD). Developed by the Ghanaian health and education ministries, PAMSCAD was designed to maintain political support for the government (Jeong, Citation1995). In unusually blunt language, the World Bank noted the politics of this support: ‘While these actions may not translate into direct support for adjustment per se, they may foster confidence in the government at a critical time’ (Marc et al., Citation1995, p. 35). Notwithstanding the debate about the effectiveness of the PAMSCAD in ameliorating the negative consequences of conditionality (Boafo-Arthur, Citation1999; Jeong, Citation1995; Marc et al., Citation1995), it was designed to the cushion government supporters from these burdens. It provided wide-spread support for a range of sectors which the government relied upon for support (Marc et al., Citation1995, pp. 103–106).

In contrast with their active involvement in the design, implementation, and compliance with IMF program lending, the Rawling’s administration displayed little effort to mediate the negative domestic effects of the IMF and other Western powers selling gold on the international market. The gold sale would have detrimental economic consequences in the Ashanti area of the country, a hotbed of opposition support. The Rawlings administration’s muted reaction indicated that saving the jobs of individuals who mostly voted for the opposition was not a government priority. Beyond expressing ‘concern’ about the IMF’s decision (GhanaWeb, Citation1999a), the government did little to stop the sale taking place even though the Ashanti Goldfields Company (AGC) indicated that 2,000 workers may have to be laid off as a result of the slump in gold prices (GhanaWeb, Citation1999b). In her detailed account of the affair Handley (Citation2007) notes how President Rawlings had also developed a personal animosity towards the AGC CEO Sam Jonah, because of his criticism of the President. Rawlings regarded Jonah as a threat to his power; this animosity spilled over into the political choice to not support the Ashanti Gold Company to weaken its CEO and thereby see off his potential threat. Without much surprise, the region overwhelmingly favored the opposition in the December 2000 election (Anebo, Citation2001, p. 83).

Ghanaian adjustment politics under the Kufour administration

On January 7, 2001, the Rawlings administration lost power to the opposition leader John Agyekum Kufour from the New Patriotic Party (NPP). The NPP was strongly tied to the indigenous entrepreneurial elite, a group that suffered under Rawlings (GhanaWeb, Citation2001a; Handley, Citation2007). The new Kufour administration continued its engagement with the IMF. Facing dire economic circumstances, Kufour instructed his administration to adopt the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative to unlock debt relief and free up fiscal space. The initiative reduced Ghana’s debt overhang to facilitate investment into the domestic economy. The new administration enacted many adjustment reforms to promote the business sectors of the economy, which favored Kufour’s entrepreneurial base, while at the same time ignoring the demands of civil society organisations who did not (Crawford & Abdulai, Citation2009, pp. 102–103). This is illustrated by a union leader who complained about the spending cuts proposed by the Kufour administration:

Mr Chigabatia expressed regret that workers have been left out in the debate on the economy even though the decisions taken affect them directly. He said workers are tired of the countless reform and economic packages fashioned by the World Bank and IMF, adding, “none of these things has served the interest of workers.” (…) Mr Chigabatia said issues such as salaries should not be put in the budget as they have the tendency of putting undue pressure on workers (GhanaWeb, Citation2001b).

Our illustrative case of Ghana provides us with some evidence that governments may utilise the flexibility given to them in complying with IMF mandates to advantage their partisans and place the burdens of adjustment disproportionately on supporters of the opposition. We found that such patterns of distributional politics are particularly salient where governments have direct control over policy implementation, notably for public-sector employment, public infrastructure, and the divestiture process. To probe the plausibility of these findings beyond the case of Ghana, we now turn to our large-N analysis using Afrobarometer data.

Data and methods

We test our hypotheses using Afrobarometer survey data, which is used to study a wide range of topics (Barnes & Burchard, Citation2013; Bratton et al., Citation2012; Brazys & Kotsadam, Citation2020; Harris & Hern, Citation2019). We are the first to leverage it to study distributive politics in the context of IMF SAPs. We utilize the first wave of Afrobarometer, which includes 12 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa surveyed between 1999 and 2001. This survey wave has the unique advantage of asking people directly about their experience with IMF SAPs. In addition, sub-Saharan Africa is a region ripe with IMF SAPs, particularly around the time when the survey was fielded. Table B1 in the supplemental appendix lists all survey countries with survey dates, IMF programs, and government partisanship.

Table 1. Partisanship and pocketbook evaluations comparing program countries and non-program countries.

Outcomes of interest

Our main outcome of interest is how people evaluate the pocketbook effects of the IMF SAP. The corresponding survey question from Afrobarometer—measured on a five-point Likert scale—is:

What effect do you think [the SAP] has had on the way you live your life? Has it made it worse, had no effect, or made it better?

□ A lot worse

□ Worse

□ Neither better nor worse

□ Better

□ A lot better

□ Do not know/not applicable

Figure A1 in the supplemental appendix shows the distribution of responses to this question. A plurality of respondents say that their personal economic circumstances had become ‘a lot worse’ (33.4%) or ‘worse’ (24.8%), but a sizeable share of respondents found their economic circumstances slightly improved (21.2%) or even significantly improved (6.9%). The remainder did not experience any difference (13.6%). The distributions look similar across the 12 survey countries, providing reassurance that positive responses are not driven by individual country experiences. These results demonstrate that IMF SAPs have heterogeneous distributional effects, creating both winners and losers. For subsequent analysis, we create the dichotomous variable SAP made my life worse for ‘a lot worse’ or ‘worse’ responses.

In further analysis, we also gauge sociotropic evaluations—how respondents assess the socioeconomic effects of the IMF SAP on their society (Figure A2). Our outcome variable, SAP hurts most people, captures agreement with the statement that the ‘[SAP] has hurt most people and only benefited a minority’, as opposed to agreement with the statement ‘the [SAP] has helped most people; only a minority have suffered’ and individuals who cannot agree with either. Figure A2 in the supplemental appendix shows the distribution of responses. While most respondents strongly agree that the SAP has hurt most people (61.3%), some respondents strongly agree with the exact opposite statement (16.8%), while the groups who moderately support either side are about equal-sized (around 10%). A negligible share of respondents is undecided (1.7%).

Key predictors

Our main independent variable at the individual level comes from an Afrobarometer question indicating whether the individual is a supporter of the party that won the most recent election, a supporter of an opposition party, or not a supporter of any party. Figure A3 shows that most people did not identify themselves with a party (44.6%). Of the remainder, a plurality supported the incumbent (36.6%), and the fewest supported the losing party (18.8%). Since our theoretical argument makes clear predictions only for respondents with a partisan affiliation, we drop non-partisan supporters in our main analysis. Hence, we capture the effect of being an Opposition Supporter relative to being a government supporter. In robustness checks, we add the neutral category, comparing government supporters and opposition supporters against non-partisan individuals.

Another individual-level predictor draws on occupational information of the respondent available from Afrobarometer. We create the binary variable Public-sector worker, which captures whether a respondent works in the public sector. This includes members of the armed forces, government workers, politicians, security workers, and teachers.Footnote2 About 5% of all respondents in the Sub-Saharan African survey countries are public-sector workers.

At the country level, we exploit two additional pieces of information. First, we capture whether a country is under an IMF program in the year of the Afrobarometer. According to our theoretical argument, an IMF SAP intensifies distributional conflict along partisan lines. Therefore, the relationship between partisan allegiance and adverse pocketbook evaluations of IMF SAPs should be stronger when the country is under an IMF program, compared to a country whose IMF SAP experience is more distant.

In addition, we follow our theoretical argument and distinguish two kinds of IMF conditionality that leave governments different levels of discretion for partisan-based distributive politics. Specifically, we count the number of quantitative performance criteria, which define macroeconomic targets that governments must reach but without a detailed set of measures of how to do so; and respectively, the number of structural performance criteria, which include detailed policy measures that often have narrow distributional effects and that leave governments limited discretion over how to achieve IMF policy objectives (Biglaiser & McGauvran, Citation2022; Reinsberg et al., Citation2019). We draw all IMF-related variables from the IMF Monitor Database (Kentikelenis et al., Citation2016).

Control variables

We control for three sets of confounding influences. First, we include country-fixed effects. This allows us to control for (un)observed country characteristics that do not vary between individuals. Second, we add a range of standard demographics, using logged age, dummies for whether the respondent is male, lives in an urban area, has at least secondary education, and is unemployed (Almond & Verba, Citation1963; Kaufman & Zuckermann, Citation1998). To capture political interest, we measure whether respondents said they always or often listen to the news on the radio and whether they consider themselves as always interested in politics. As an objective indicator of political knowledge, we measure whether the respondent (correctly) recalled the name of the finance minister. Furthermore, we use a binary indicator to capture whether the respondent is satisfied with democracy as currently practiced in the country. Finally, we tap into core economic values by measuring support for free markets, the public sector, and privatization of SOEs. Controlling for these values limits the extent that they condition evaluations of IMF-sponsored measures. Third, we augment the control set by gauging respondent evaluations of the state of the economy and the performance of the president (Kaufman & Zuckermann, Citation1998). Specifically, we capture whether respondents think the economy is worse than twelve months ago and whether they expect it to deteriorate in the next twelve months. We include these variables to ensure that our results are not driven by individuals who are generally more pessimistic about the economy. In addition, we include a binary variable indicating whether respondents are dissatisfied with the performance of the incumbent. This helps us isolate evaluations of the IMF SAP as opposed to more general government policies while also proxying the extent to which respondents ‘(dis)like’ a particular government that may affect both their IMF SAP evaluation and their partisan orientations. The appendix describes all the variables (Table A1).

Methodological considerations

People may not have pertinent perceptions about IMF SAPs if they never heard about these programs; in fact, respondent evaluations of the IMF SAP are missing if a respondent has not heard about it. In our sample, 33.8% of the respondents have heard about the SAP in their country. We estimate models on the sub-sample of those SAP-aware respondents.Footnote3

In our main analysis, we use linear-probability models with country-fixed effects, which provide readily interpretable coefficient estimates.Footnote4 With just twelve countries in the dataset, assumptions necessary for random-effects estimation are unlikely to be met, fixed-effects models allow us to control for unobserved country heterogeneity (Greene, Citation2003). In robustness tests, we estimate pooled probit models and multi-level random-intercept models, which allow us to include country covariates alongside individual-level variables (Schmidt-Catran & Fairbrother, Citation2016). We use survey weights, available from the Afrobarometer dataset, ensuring the representativeness of respondent samples for the country population and adjusting for different population sizes across sample countries. For inference purposes, we compute robust standard errors clustered on countries.

Results

Illustrative evidence

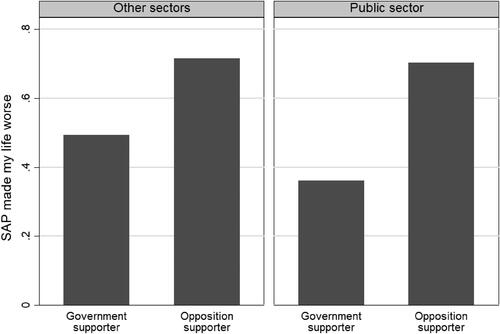

Before proceeding with multivariate analysis, we look descriptively at the patterns in the data. plots the prevalence of negative pocketbook evaluations of IMF SAPs across different partisans and for different occupational groups. Two striking facts stand out. First, across sectors of employment, opposition supporters are more likely to have negative pocketbook evaluations of the IMF SAP than government supporters. A t-test confirms that this partisan difference is statistically significant in both sub-samples (p < 0.01). Second, the partisan gap is higher in the public sector, and this seems to be driven by lower dissatisfaction among government supporters. Taken together, these findings are consistent with the argument that during times of economic pressure induced by IMF SAPs, governments lump adjustment burdens on the opposition while protecting their own partisan supporters.

Evidence from multivariate analysis

Turning to multivariate analysis, we examine the relationship between partisan allegiances and IMF SAP pocketbook evaluations for individuals in non-program countries and program countries (). Consistent with our expectations, we find that IMF SAPs intensify distributional politics along partisan lines. When a country is not (currently) under an IMF program, partisan allegiance is unrelated to respondent beliefs that the IMF SAP made their life worse. In contrast, when a country is under an IMF program, opposition supporters are more likely to report that their life is worse due to the IMF program. In terms of effect magnitudes, based on the last model for program countries, the probability of a negative IMF SAP evaluation is 69.9% (61.8%-78.0%) among opposition supporters, compared to just 49.3% (45.1%-53.4%) among government supporters.Footnote5 This difference of about twenty percentage points is statistically significant (p < 0.01) and robust against the inclusion of control variables. These results provide evidence for our first hypothesis that partisan supporters of opposition parties view the personal consequences of IMF SAPs more negatively than partisans who supported the incumbent.

Coefficient estimates of control variables are consistent with theoretical expectations, although few of them are statistically significant. We find some evidence for differences in IMF SAP evaluations by age, gender, (un)employment, and political interest. Where people are more satisfied with democracy in their country, they are less critical of IMF SAPs. People are more critical with IMF SAPs if they support capitalism and favor privatization, possibly due to unfulfilled expectations of capitalist development. In the models with extended control variables, we find that individuals with generally more pessimistic evaluations of the economy and the performance of the incumbent are more likely to express negative evaluations of IMF SAPs.

presents the results from interaction models where we allow for the effect of partisan alignment to vary by the occupational group of respondents. We expected that individuals who are in public-sector employment and supported opposition parties view the consequences of IMF program lending more negatively than those public-sector employees who supported the incumbent party, and that this partisan difference is larger than the partisan difference in other sectors. The results corroborate our expectations. While we continue to find significant differences in IMF SAP evaluations by partisan allegiance, there is now an additional statistically significant increase in the prevalence of negative IMF SAP evaluations among public-sector workers who voted for the opposition (p < 0.05). In substantive terms, the partisan difference is about 35 percentage-points in the public sector, with the likelihood of a negative pocketbook evaluation of 77.2% (68.1%-86.2%) among opposition supporters and 42.3% (34.6%-49.9%) among government supporters. Conversely, the partisan difference is only 19 percentage-points in other sectors, with 69.0% (60.7%-77.3%) of opposition supporters and 50.1% (46.3%-53.9%) of government supporters having a negative IMF SAP pocketbook evaluation. This analysis provides support for hypothesis 2 that the partisan gap in IMF program evaluation is particularly strong among individuals in public sector employment.

Table 2. Partisanship, public-sector employment, and pocketbook evaluations in program countries.

exploits country-level variation in the design of IMF SAPs in program countries. We expected partisan differences in IMF SAP evaluations to be more pronounced when IMF SAPs afford governments with more discretion as to how to allocate adjustment burdens. This should be true for programs with more quantitative performance criteria, as opposed to programs with fewer such criteria. The results corroborate this expectation. Coefficient estimates for opposition supporters are substantively larger and statistically significant in high-discretion programs, with above-median number of quantitative performance criteria. In low-discretion programs, there is no significant partisan difference in negative IMF SAP evaluations. In substantive terms, the likelihood of a negative pocketbook evaluation is 71.5% (62.9%-80.1%) among opposition supporters and 47.0% (41.3%-52.6%) among government supporters, which equals a partisan difference of 25 percentage-points. In the low-discretion scenario, the partisan difference is only 14 percentage-points.Footnote6 The results provide evidence supporting hypothesis 3 that the partisan gap in IMF program evaluations is particularly strong when IMF programs leave governments more discretion for distributive politics.

Table 3. Partisanship and pocketbook evaluations in program countries at different levels of government discretion.

In the appendix, we use an alternative way to test whether partisan differences in IMF SAP evaluations are less pronounced when IMF SAPs entail more structural performance criteria, compared to when they entail fewer such criteria. This is because structural conditions are widely regarded as limiting government discretion. The results corroborate this expectation. High-discretion IMF programs, with a below-median number of structural conditions, tend to be related to a larger partisan gap in IMF SAP pocketbook evaluations. In contrast, for low-discretion programs, the partisan gap is insignificant (Table A2).

We are concerned that our results may not be evidence of distributive politics but rather the ideological pre-dispositions of respondents toward a specific government that make them evaluate any government policy less favorably. We already controlled for the level of satisfaction with the incumbent and subjective assessments of the national economy, but this may be insufficient to fully mitigate subjectivity bias. Therefore, we now use objective hardship outcomes. The Afrobarometer survey includes indicators of deprivation for a range of items such as food, water, health care, and money income. For each of these items, respondents indicate the frequency with which they (and their family) have gone without these items in the past year. To obtain an index of deprivation, we add up responses across all items provided no data are missing.

shows the results. We find that opposition supporters are less deprived than government supporters in countries without ongoing IMF programs, which reflects average pre-existing differences across partisan groups. With IMF SAPs, we find a positive relationship between being an opposition supporter and the deprivation index. The most credible model includes standard demographics but no performance evaluations, which could be affected by deprivation. We therefore believe that the results are strongly consistent with the notion that partisan-based differences in deprivation are the result of actual distributional politics rather than mere perceptions.

Table 4. Partisanship and deprivation comparing program countries and non-program countries.

To lend further support to this interpretation, we split the sample of program countries, considering high-discretion programs and low-discretion programs. Consistent with our expectations, we find that the partisan gap with respect to deprivation is large and statistically significant in the high-discretion scenario. In contrast, the partisan gap is indistinguishable from zero in the low-discretion case (Table A3).

A final concern is that our assumption that governments can identify partisans may be unrealistic. A plausible alternative is that governments observe which districts voted for them in the last election and tailor their support accordingly. Therefore, we would expect constituencies that primarily voted for the opposition to have more negative pocketbook views of the IMF SAP than constituencies who voted for the incumbent. We source constituency-level data on the vote share for opposition parties from the African Elections Database for all countries with available data that overlap with the Afrobarometer country sample (AED, Citation2022). We obtain a significantly positive relationship between the opposition vote share and the prevalence of a negative pocketbook evaluation of the IMF SAP (Table A4). To address the concern that governments indeed target constituencies, rather than individuals, we augment the model by including partisanship at the individual level. We find a significantly positive coefficient of opposition supporter that is similar in size as in our earlier regressions (p < 0.01), despite the positive constituency-level variable (Table A5). This increases our confidence in the validity of our theoretical argument which posits an individual-level alignment mechanism.

Robustness tests

Our main findings withstand a battery of additional robustness tests that are presented in detail in the supplemental appendix. First, we re-run our models using survey-adjusted probit regressions and continue to find a statistically significant difference in IMF SAP pocketbook evaluations across partisan groups (Table A6), even when considering individuals employed in the public sector (Table A7). Our results also hold for random-intercept multi-level models that include country-level characteristics such as economic growth, inflation, democracy, and institutional quality. The partisan gap in IMF SAP evaluations is significant among all individuals (Table A8) and is even larger for individuals in public-sector employment (Table A9).

Second, we extend our sample of respondents to include non-partisans. From an empirical perspective, this increases the power of our inferences, at the cost of including a group of respondents for which we have not formulated ex ante theoretical expectations. Our focus therefore remains on the effect difference between partisans. An F-test confirms that the difference between opposition supporters and government supporters with respect to the IMF SAP pocketbook assessment remains strongly statistically significant (Table A10).Footnote7

Third, upon removing country-fixed effects, we can exploit cross-country institutional variation which leads us to expect that distributive politics matters less when several parties share executive power, for instance under a ‘government of national unity’. Irrespective of individual partisan allegiance, the likelihood of negative IMF SAP evaluations is strictly lower for governments of national unity compared to other governments. Moreover, the partisan difference in IMF SAP pocketbook evaluations is insignificant for governments of national unity, but statistically significant for all other governments (Table A12).

Fourth, to extend our findings beyond pocketbook evaluations, we also consider sociotropic evaluations of IMF SAPs. We continue to find a strongly significant positive relationship between being an opposition supporter and a negative IMF SAP evaluation (Table A13). When considering different sectors of employment, we find no statistically significant difference for public-sector workers compared to workers in other sectors. This is plausible because the survey question is cast in deliberately broader terms, which makes it possible for adverse pocketbook evaluations to co-exist with relatively more positive sociotropic evaluations (Table A14).

Fifth, excluding individual countries from the sample, we find our coefficient estimates to be relatively unaffected. The coefficient of opposition supporter is always statistically significant (p < 0.01), while the conditional effect estimates for public-sector workers remains at least marginally significant in four out of seven models (Table A15).

Recognizing that African politics often operates along ethnic lines (Bratton et al., Citation2012), we probe the extent of distributional politics in IMF SAPs based on ethnic allegiances. We would expect that individuals belonging to an ethnically discriminated group will have less favorable evaluations of the IMF SAP than members of a powerful group. To test this hypothesis, we rely on group status information from the Ethnic Power Relations dataset (Vogt et al., Citation2015). While Afrobarometer does not record the ethnicity of respondents, it identifies the main language that respondents speak. This makes it possible to infer the ethnic group from the language spoken, at least for some countries.Footnote8 Our remaining sample has 6,136 individuals from five countries, of which 4,795 individuals are members of the powerful group and 1,341 individuals are from powerless groups. The sample further reduces when requiring that individuals must have heard about the SAP in their country. Using ethnicity data, we find a significantly higher likelihood of a negative pocketbook evaluation of IMF SAPs among members of powerless groups, compared to members of powerful groups (Table A16).

In sum, these robustness tests corroborate our main finding that partisan allegiances affect how governments allocate adjustment burdens of IMF SAPs, with the result of diverging assessments of such programs among partisan (or ethnic) groups.

Conclusion

How do governments allocate the burden of adjustment from IMF-mandated policy reform programs? Leveraging the first wave of the Afrobarometer—fielded at the heyday of structural adjustment in 12 Sub-Saharan African countries—we examine how political allegiances shape how individuals evaluate the consequences of IMF SAPs for their economic fortunes. We argue that governments under IMF adjustment pressure will inflict adjustment burdens on opposition supporters while protecting their own partisan supporters from the adverse effects of structural adjustment. We find more negative adjustment experiences among opposition supporters compared to government supporters. These differences cannot be explained by ideological predispositions of respondents toward the incumbent government, which we ensure by including relevant control variables.

Several additional tests lend further credence to our argument. We find the partisan divide to be more pronounced among public-sector workers. We also find evidence for more intense partisan-based distributive politics for governments with high-discretion programs, as measured by the number of quantitative performance criteria. These additional findings bolster our argument because they indicate that the extent of partisan-based distributional politics is greater where governments have direct control over distributive outcomes as well as discretion to do so. In addition, there is evidence of higher deprivation among opposition supporters relative to government supporters in the context of IMF SAPs, indicating that our results cannot be explained by mere perceptions. Finally, we show that our results are not limited to political allegiances, given that powerless ethnic groups are more likely to report negative SAP effects compared to powerful ethnic groups. Our analyses provide evidence that proximity to power is an important factor in how citizens are protected from or burdened with the consequences of IMF program lending.

We note three limitations of our study. First, while surveys like Afrobarometer are designed to capture perceptive effects, we took several remedies to this problem, notably by controlling for perceptions of government performance more generally and by measuring objective hardship outcomes. However, future research should further validate our findings using survey questions that are more explicitly designed to dismiss potential alternative explanations. A second obstacle to identification is the lack of panel data. As the Afrobarometer survey provides only a snapshot in time, we cannot control for unobserved respondent heterogeneity. However, we carefully consider information about timing with respect to survey years, IMF SAPs, past elections, as well as the wording of survey instruments. Our qualitative case study exploited inter-temporal variation in the partisan control of the government under otherwise similar contextual conditions. Future research could address these challenges by designing surveys motivated by questions like ours. Third, though our theoretical mechanisms should be universally applicable, our empirical findings are limited to respondents from twelve African countries. While this is the largest sample available for a micro-level test of distributional effects in the context of SAPs, future research should seek to replicate the findings in other world regions. Extensions could also focus on other international financial institutions and the role of political alignment across levels of government (Bracco et al., Citation2015; Clegg, Citation2021).

Our theoretical argument and findings extend the study of patronage politics and insights from the local political economy of foreign aid into new areas, demonstrating their relevance for understanding the distributional consequences of IMF compliance. We show that governments intensify distributive politics when facing austerity pressures, leading to more adverse views of IMF SAPs among opposition supporters. While IPE case studies have long known about the distributive politics of IMF SAP implementation, they downplayed the role of partisan allegiances relative to interest groups. Our research indicates the importance of partisan allegiances to better understand who is burdened with the costs of adjustment.

In terms of policy implications, our study suggests that governments from developing countries have more leeway than commonly thought when it comes to choosing how to implement IMF adjustment programs. We have shown that governments are strategic actors that do not simply execute demands from international organizations but do so in a way that benefits their own political fortunes. Importantly, our findings suggest that the choices that governments make in the context of IMF programs—in addition to the inherent distributional consequences of IMF conditions—may exacerbate inequality, which in turn may have negative consequences for economic development and political stability. While the Fund has limited opportunities to interfere in domestic politics to mitigate harmful distributive politics, its primary policy lever is the design of its adjustment programs. In this regard, our article chimes with previous studies that advocate for easing conditionality burdens, albeit for reasons unrelated to lack of capacity and government ownership. Our research suggests that reducing the number of quantitative performance criteria can reduce the scope for governments to engage in harmful distributional politics.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1 MB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kristin Bakke, Inken von Borzyskowski, Zeynep Bulutgil, Lorenzo Crippa, Sam Erikletian, Adam Harris, Michael Heaney, Jennifer Hodge, Saliha Metinsoy, Neil Mitchell, Julie Norman, Tom O'Grady, Kit Rickard, Mike Seiferling, Byunghwan Son, Thomas Stubbs, Katerina Tertytchnaya, Kevin Young, and participants of the UCL research seminar on Comparative Political Economy (8 October 2020), the IPEG seminar at Groningen University (17 November 2021), the University of Glasgow Comparative Politics cluster and the workshop on ‘The political economy of the security − development nexus’ for excellent comments. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Replication material for this article is available on Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/INTTLH).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bernhard Reinsberg

Bernhard Reinsberg is a Reader in Politics and International Relations at the University of Glasgow and a Research Associate in Political Economy at the Centre for Business Research at the University of Cambridge. His research broadly covers the political economy of international organisations—such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund—and seeks to contribute to a better understanding of the socio-political effects of their development programs using large-N analysis and causal inference techniques for observational data.

M. Rodwan Abouharb

M. Rodwan (Rod) Abouharb is an Associate Professor of International Relations, University College London. His research examines the correlates of physical-integrity rights respect and the realization of economic and social rights. He is interested in the processes that affect the civility of relations between government and its citizens, in particular how integration into the international economic system affects the onset of civil war and human rights abuses within countries. His individual and collaborative work, cross-national in nature, is conducted within the framework of behavioral political science.

Notes

1 The IMF’s Monitoring of Fund Arrangements (MONA) database shows that Ghana met all quantitative targets in its 1995 ESAF program. While the IMF transitioned to a new system for collecting information during 1999–2003, we lack implementation records for the 1999 ESAF program. However, other IMF reports indicate that the Ghanaian government was highly committed to implement program targets [https://www.imf.org/external/np/loi/2000/gha/01/index.htm].

2 Our results are robust to modifications to this definition. Results are qualitatively similar when dropping security workers, and also when dropping politicians.

3 Results are robust to using a Heckman-type selection model in which we jointly estimate the determinants of program awareness and program evaluations for those being aware. We found that being a radio listener makes a respondent more aware of an IMF SAP while unlikely affecting IMF SAP evaluations. Results are available on request from the authors.

4 Results are similar using non-linear binary response models.

5 All CIs based upon 95% confidence.

6 These differences already appear in the raw data, both for quantitative conditions (Figure A4) and structural conditions (Figure A5).

7 We find no statistically significant difference of either partisan group relative to non-partisans in the public sector, beyond the already existing gap in the economy as a whole (Table A11).

8 We disregard countries where ethnicity is not salient and where ethnicity ascriptions based on language are impossible.

References

- Abdulai, A.-G., & Hickey, S. (2016). The politics of development under competitive clientelism: Insights from Ghana’s Education Sector. African Affairs, 115(458), adv071–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adv071

- Abouharb, M. R., & Cingranelli, D. (2007). Human rights and structural adjustment: The impact of the IMF and World Bank. Cambridge University Press.

- AED. (2022). African Elections Database. Retrieved June 1, 2022, from https://africanelections.tripod.com/

- Almond, G. A., & Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton University Press.

- Anaxagorou, C., Efthyvoulou, G., & Sarantides, V. (2020). Electoral motives and the subnational allocation of foreign aid in sub-Saharan Africa. European Economic Review, 127, 103430–103432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2020.103430

- Anebo, F. K. G. (2001). The Ghana 2000 elections: Voter choice and electoral decisions. African Journal of Political Science, 6(1), 69–88. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajps.v6i1.27304

- Appiah-Kubi, K. (2001). State-owned enterprises and privatisation in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 39(2), 197–229. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X01003597

- Babb, S. L. (2013). The Washington consensus as transnational policy paradigm: Its origins, trajectory and likely successor. Review of International Political Economy, 20(2), 268–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2011.640435

- Barnes, T. D., & Burchard, S. M. (2013). “Engendering” politics: The impact of descriptive representation on women’s political engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa. Comparative Political Studies, 46(7), 767–790. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414012463884

- Bates, R. (1981). Markets and states in Tropical Africa. University of California Press.

- Beazer, Q. H., & Woo, B. (2016). IMF conditionality, government partisanship, and the progress of economic reforms. American Journal of Political Science, 60(2), 304–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12200

- Biglaiser, G., & McGauvran, R. J. (2022). The effects of IMF loan conditions on poverty in the developing world. Journal of International Relations and Development, 25, 806–833.

- Blanton, R. G., Early, B., & Peksen, D. (2018). Out of the shadows or into the dark? Economic openness, IMF programs, and the growth of shadow economies. The Review of International Organizations, 13(2), 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9298-3

- Boafo-Arthur, K. (1999). Ghana: Structural adjustment, democratization, and the politics of continuity. African Studies Review, 42(2), 41–72. https://doi.org/10.2307/525364

- Bracco, E., Lockwood, B., Porcelli, F., & Redoano, M. (2015). Intergovernmental grants as signals and the alignment effect: Theory and evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 123, 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.11.007

- Bratton, M., Bhavnani, R., & Chen, T. (2012). Voting intentions in Africa: Ethnic, economic or partisan? Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 50(1), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2012.642121

- Bratton, M. R., & van de Walle, N. (1997). Democratic experiments in Africa: Regime transitions in comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press.

- Brazys, S., & Kotsadam, A. (2020). Sunshine or curse? Foreign Direct Investment, the OECD anti-bribery convention, and individual corruption experiences in Africa. International Studies Quarterly, 64(4), 956–967. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqaa072

- Breen, M., & Doak, E. (2021). The IMF as a global monitor: Surveillance, information, and financial markets. Review of International Political Economy (forthcoming). https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2021.2004441

- Breen, M., & Gillanders, R. (2015). Political trust, corruption, and ratings of the IMF and the World Bank. International Interactions, 41(2), 337–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2014.948154

- Brierley, S. (2021). Combining patronage and merit in public sector recruitment. The Journal of Politics, 83(1), 182–197. https://doi.org/10.1086/708240

- Briggs, R. C. (2012). Electrifying the base? Aid and incumbent advantage in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 50(4), 603–624. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X12000365

- Briggs, R. C. (2014). Aiding and abetting: Project aid and ethnic politics in Kenya. World Development, 64, 194–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.05.027

- Campos, J. E., & Esfahani, H. S. (1996). Why and when do governments initiate public enterprise reform? The World Bank Economic Review, 10(3), 451–485. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/10.3.451

- Carlitz, R. D. (2017). Money flows, water trickles: Understanding patterns of decentralized water provision in Tanzania. World Development, 93, 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.11.019

- Casper, B. A. (2017). IMF programs and the risk of a coup d’état. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(5), 964–996. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002715600759

- Chandra, K. (2004). Why ethnic parties succeed: Patronage and ethnic headcounts in India. Cambridge University Press.

- Clegg, L. (2021). Taking one for the team: Partisan alignment and planning outcomes in England. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 23(4), 680–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120985409

- Crawford, G., & Abdulai, A.-G. (2009). The World Bank and Ghana’s poverty reduction strategies: Strengthening the state or consolidating neo-liberalism? Labour, Capital and Society, 42(1–2), 82–115.

- Dellmuth, L. M., & Tallberg, J. (2021). Elite communication and the popular legitimacy of international organizations. British Journal of Political Science, 51(3), 1292–1313. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000620

- Dreher, A. (2006). IMF and economic growth: The effects of programs, loans, and compliance with conditionality. World Development, 34(5), 769–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.11.002

- Dreher, A., Fuchs, A., Parks, B., Strange, A., & Tierney, M. (2022). Banking on Beijing: The aims and impacts of China’s Overseas Development Program. Cambridge University Press.

- Edwards, M. S. (2009). Public support for the international economic organizations: Evidence from developing countries. The Review of International Organizations, 4(2), 185–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-009-9057-6

- Ejdemyr, S., Kramon, E., & Robinson, A. L. (2018). Segregation, ethnic favoritism, and the strategic targeting of local public goods. Comparative Political Studies, 51(9), 1111–1143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414017730079

- Evans, G., & Andersen, R. (2006). The political conditioning of economic perceptions. The Journal of Politics, 68(1), 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00380.x

- Fernández-Albertos, J., Kuo, A., & Balcells, L. (2013). Economic crisis, globalization, and partisan bias: Evidence from Spain. International Studies Quarterly, 57(4), 804–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12081

- Friedman, T. L. (2000). The Lexus and the Olive Tree. Anchor Books.

- GhanaWeb. (1999a). NDC expresses concern over sale of gold reserves by IMF and UK. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/artikel.php?ID=7914

- GhanaWeb. (1999b). S. Africa says European gold tour cancelled. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/business/S-Africa-says-European-gold-tour-cancelled-7729

- GhanaWeb. (2000). IMF criticises Ghana wage, tax increases. May 31st. https://mobile.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/IMF-criticises-Ghana-wage-tax-increases-10430

- GhanaWeb. (2001a). Kufour’s arrival means big changes for Ghana business. January 11th. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/business/Kufour-s-arrival-means-big-changes-for-Ghana-business-13007

- GhanaWeb. (2001b). Budget is a Foundation Budget- Nduom. April 4th. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/2001-Budget-is-aFoundation-Budget-Nduom-14490

- GhanaWeb. (2001c). IMF, World Bank support Ghana. July 3rd. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/IMF-World-Bank-support-Ghana-16322

- Goes, I. (2022). Examining the effect of IMF conditionality on natural resource policy. Economics & Politics. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecpo.12214

- Goes, I., & Chapman, T. L. (2021). The Power of Ideas: IMF Surveillance and Natural Resource Sector Reform. Working Paper.

- Greene, W. H. (2003). Econometric analysis (4th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Haggard, S. & Kaufman, R. R. (Eds.). (1992). The politics of economic adjustment: International constraints, distributive conflicts and the state. Princeton University Press.

- Handley, A. (2007). Business, government, and the privatisation of the Ashanti Goldfields Company in Ghana. Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, 41(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2007.10751350

- Harding, R. (2015). Attribution and accountability: Voting for roads in Ghana. World Politics, 67(4), 656–689. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887115000209

- Harris, A. S., & Hern, E. (2019). Taking to the streets: Protest as an expression of political preference in Africa. Comparative Political Studies, 52(8), 1169–1199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018806540

- Harris, J., & Posner, D. (2019). (Under what conditions) do politicians reward their supporters? Evidence from Kenya’s Constituencies Development Fund. American Political Science Review, 113(1), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000709

- Hartzell, C. A., Hoddie, M., & Bauer, M. E. (2010). Economic liberalization via IMF structural adjustment: Sowing the seeds of civil war? International Organization, 64(2), 339–356. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818310000068

- Henisz, W. J., & Mansfield, E. D. (2019). The political economy of financial reform: de jure liberalization vs. de facto implementation. International Studies Quarterly, 63(3), 589–602. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqz035

- Herbst, J. (1990). The structural adjustment of politics in Africa. World Development, 18(7), 949–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(90)90078-C

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2005). Malawi – request for a three-year arrangement under the poverty reduction and growth facility and additional interim assistance under the enhanced initiative for heavily indebted poor countries [EBM/05/71]. https://archivescatalog.imf.org/Details/ArchiveExecutive/125181805.

- Isaksson, A.-S., & Kotsadam, A. (2018). Chinese aid and local corruption. Journal of Public Economics, 159, 146–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.01.002

- Jablonski, R. (2014). How aid targets votes: The impact of electoral incentives on foreign aid distribution. World Politics, 66(2), 293–330. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887114000045

- Jeong, H.-W. (1995). Liberal economic reform in Ghana: A contested political agenda. Africa Today, 42(4), 82–104.

- Joseph, R. A. (1987). Democracy and prebendal politics in Nigeria: The rise and fall of the Second Republic. Cambridge University Press.

- Kaufman, R., & Zuckermann, L. (1998). Attitudes toward economic reform in Mexico: The role of political orientations. American Political Science Review, 92(2), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.2307/2585669

- Kaya, A., Handlin, S., & Günaydin, H. (2020). Populism and voter attitudes toward international organizations: Cross-country and experimental evidence on the International Monetary Fund. Political Economy of International Organization Conference. https://bit.ly/2Q76mlc.

- Keen, D. (2005). Liberalization and conflict. International Political Science Review, 26(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512105047897

- Kentikelenis, A., Stubbs, T., & King, L. (2016). IMF conditionality and development policy space, 1985–2014. Review of International Political Economy, 23(4), 543–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2016.1174953

- Kitschelt, H., & Wilkinson, S. I. (2007). Citizen–politician linkages: An introduction. In H. Kitschelt and S. I. Wilkinson (Eds.), Patrons, clients, and policies: Patterns of democratic accountability and political competition (pp. 1–49). Cambridge University Press.

- Kopecký, P. (2011). Political competition and party patronage: Public appointments in Ghana and South Africa. Political Studies, 59(3), 713–732. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00887.x

- Kopecký, P., Mair, P., & Spirova, M. (2012). Party patronage and party government. Oxford University Press.

- Kopecký, P., Meyer Sahling, J.-H., Panizza, F., Scherlis, G., Schuster, C., & Spirova, M. (2016). Party patronage in contemporary democracies: Results from an expert survey in 22 countries from five regions. European Journal of Political Research, 55(2), 416–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12135

- Kramon, E., & Posner, D. (2013). Who benefits from distributive politics? How the outcome one studies affects the answer one gets. Perspectives on Politics, 11(2), 461–474. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592713001035

- Lang, V. (2021). The economics of the democratic deficit: The effect of IMF programs on inequality. The Review of International Organizations, 16(3), 599–623. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-020-09405-x

- Lio Rosvold, E. (2020). Disaggregated determinants of aid: Development aid projects in the Philippines. Development Policy Review, 38(6), 783–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12465

- Marc, A., Graham, C., Schacter, M., & Schmidt, M. (1995). Social action programs and social funds: A review of design and implementation in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank World Bank Discussion papers. 274. World Bank.

- Marchesi, S., & Sirtori, E. (2011). Is two better than one? The effects of IMF and World Bank interaction on growth. The Review of International Organizations, 6(3–4), 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-011-9107-8

- Nelson, J. M. (1984). The political economy of stabilization: Commitment, capacity, and public response. World Development, 12(10), 983–1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(84)90025-1

- Ninsin, K. A. (1998). Postcript: Elections, democracy and elite consensus. In K. A. Ninsin (Ed.), Transition to Democracy. CODESRIA.

- Oliveros, V. (2021). Patronage at work: Public jobs and political services in Argentina. Cambridge University Press.

- Öniş, Z. (2009). Beyond the 2001 financial crisis: The political economy of the new phase of neo-liberal restructuring in Turkey. Review of International Political Economy, 16(3), 409–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290802408642

- Ortiz, D. G., & Béjar, S. (2013). Participation in IMF-sponsored economic programs and contentious collective action in Latin America, 1980–2007. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 30(5), 492–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894213499677