ABSTRACT

In the West, women have practiced law and advocated greater gender diversity in the legal profession for more than a century. In Qatar, concepts such as “equality of opportunity” and “diversity or inclusion in the profession” are virtually unexplored by research and only beginning to appear in casual conversations. While the number of women studying law in Qatar has significantly increased, the number of women practicing law as prosecutors, judges and lawyers has not directly correlated. This article will use Qatar as a case study to analyze how culture and modern development affect the feminization of Qatar’s bar and bench.

Introduction

A diverse legal profession is more just, productive and intelligent because diversity, both cognitive and cultural, often leads to better questions, analyses, solutions, and processes.Footnote1

In Qatar, concepts such as “equality of opportunity” and “diversity or inclusion in the profession” are virtually unexplored by research and only beginning to appear in casual conversations.Footnote6 While the number of women studying law in Qatar has significantly increased, the number of women practicing law as prosecutors, judges and lawyers has not directly correlated. Enlisting female law graduates to join Qatar’s legal profession and diversify it remains a complicated issue due to a mix of social, cultural, and logistical obstacles.

Qatar: evolution of the state and legal education

Qatar is a small nation in the form of a peninsula extending northward into the Arabian Sea from the southeastern edge of Saudi Arabia.Footnote7 The nation’s total land area is about 11,500 square kilometers and its total resident population is about 2.7 million peopleFootnote8 with an estimated 12% of the resident population holding Qatari citizenship.Footnote9 The country is a constitutional monarchy ruled by the Al-Thani family and has the second largest GDP per capita in the world with oil and natural gas sources contributing the most to revenue.Footnote10

To understand Qatari legal diversity and meaningfully compare it to Western bars, one must put the Qatari bar’s evolution in the context of the country’s modern development instead of conducting a side-by-side comparison of current statistics with those of the West. As an example, by 1878, when lawyers in the United States were forming the American Bar Association and Committee on Legal Education & Admissions to the Bar,Footnote11 nearly a decade after the first woman was admitted to practice law,Footnote12 and five years after the first African-American woman was licensed to practice law,Footnote13 Qatar was occupied by the Ottomans.Footnote14 By the 1930’s, when women had been admitted as members to the ABA,Footnote15 and had already formed the National Association of Women Lawyers,Footnote16 there were more law students registered in US law schools than there were residents of the State of QatarFootnote17 and the people of Qatar were starving.Footnote18

It was only in the 1950’s, after the exportation of oil,Footnote19 that Qatar’s first modern primary schools opened with a school for boys opening in 1952 followed shortly by a school for girls in 1955.Footnote20 Prior to “modern” schools, education existed in the form of the Mutawa (مُطَوَّع) Footnote21 and the Katateeb (الكتاتيب).Footnote22 Formal non-religious women’s primary education initially was not well received, and Qatar’s first headmistress, Amnah Mahmood Al Gidah, spent much of her time advocating and convincing parents of its value and necessity.Footnote23

Most of the girls were prevented from attending school. People were against formal education because they believed it was anti-religious and corruptive. So, I used to explain to them how Islam considered education obligatory for both males and females who should seek it from the moment of birth until death.Footnote24

Emiri Decree officially established QU as a public university in 1977 and formal undergraduate legal education began in 1993 with the establishment of the College of Shari’a.Footnote28 By 2003, QU had six CollegesFootnote29 and enrolled about 8,600 students of whom 73% were women.Footnote30 A College of Law, autonomous from the College of Shari’a and Islamic Studies, began operations in 2004 and was formally created in 2006.Footnote31 By 2015, the College of Law enrolled 1375 undergraduate students, of whom 62% were female.Footnote32 By Fall Semester 2017, the College of Law enrolled 557 male undergraduate students, 42 male LLM students, 1,111 female undergraduate students, and 63 female LLM students.Footnote33

Three new law schools opened in Qatar in recent years.Footnote34 The Police College opened in 2013 pursuant to Emiri Decree.Footnote35 The Police College operates under the direction of the Ministry of Interior and offers a four-year Bachelor’s degree in law and police science with the aim of training future police officers.Footnote36 The program is taught in Arabic. In 2015, Hamad Bin Khalifa University began offering a Juris Doctorate degree in law.Footnote37 The program, taught in English, graduated its first batch of 13 students in 2018 and will graduate its second batch of 12 students in 2019.Footnote38 Finally, in 2016, the Rule of Law and Anti-Corruption Centre, in collaboration with the University of Sussex, opened a graduate program offering students an L.L.M. in Corruption, Law and Governance.Footnote39 The program is taught in English and graduated its first batch of 15 students during December of 2018.Footnote40

Qatar: evolution of the legal profession

In Qatar, lawyering, as it is known in the West, is a recent profession. While mediation of disputes is an ancient practice with the Prophet MuhammadFootnote41 himself known for mediating disputes in Medina,Footnote42 formal court processes with attorneys or legal figures representing aggrieved parties are not.

Traditionally, when disputes would arise between tribes, a “hakam” (الحكم),Footnote43 or mediator, would attempt to mediateFootnote44 with local Sheikhs and/or the Shari’a courts offering the final resolution of all disputes.Footnote45 Qatar deviated away from traditional dispute resolution when H.H. Sheikh Abdalla bin Jassim Al-Thani signed the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (hereinafter “APOC”) concession on 17 May 1935. By signing the APOC concession, he agreed to allow jurisdiction of any British APOC employees and non-Muslim foreigners to rest solely with the British government and its courts.Footnote46 This effectively created a dual-court system allowing non-Muslim expatriates to have access to the common law principles of the British courts and Qatari and Muslim expatriates to have access to traditional means and Shari’a courts. In 1971, after Qatar ceased being a British protectorate,Footnote47 the Adlia court, a civil and commercial court, replaced the British courts for non-Muslim expatriates.Footnote48 In 2003, a unified judicial court which combined the Shari’a and Adlia courts was created.Footnote49

Qatar’s legal profession: current statistics

Given the relatively short period during which the formal study and practice of law has been available, Qatar has seen remarkable growth in its legal services profession. Qatar currently has more than 160 attorneys licensed to plead before the courts,Footnote50 a formal Bar Association run by a Board of Directors,Footnote51 and QU has graduated more than 1,100 law students since 1993.Footnote52 The Ministry of Justice’s Center for Legal and Judicial Studies has trained more than 74 “Judge Assistants,”Footnote53 69 “Assistant Prosecutors,”Footnote54 52 “Lawyers” who will be licensed to plead before the Courts,Footnote55 and 636 “Legal Researchers”Footnote56 entering different state agencies and institutions.Footnote57 In 2015, there were a total of 198 judicial officers working within the various courts run by the Supreme Judiciary Council.Footnote58 In addition to local law firms, two foreign firms are licensed by the Ministry of JusticeFootnote59 and 26 foreign law firms are licensed to operate under the Qatar Financial Centre.Footnote60

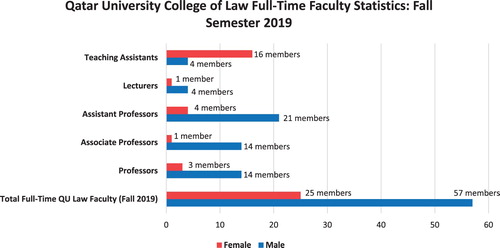

However, despite extremely fast-pace growth in the legal services market, diversity in Qatar’s legal profession is still lagging behind. QU College of Law has graduated more than 700 female law students since the University began offering law degrees in 1993.Footnote61 Yet, despite the number of educated women graduating with law degrees, the State of Qatar only has two female prosecutors,Footnote62 eight female judicial officers,Footnote63 women constitute 19% of licensed attorneys able to plead before the Courts, and Qatari women represent less than 18% of licensed attorneys. Footnote64 While women comprise almost 30% of the law faculty at QU, the number of female faculty in positions higher than “Teaching Assistant” remains almost 13% of total faculty, versus almost 75% for the male faculty ( and ).Footnote65

Figure 1. Qatar University College of Law Full-Time Faculty Statistics for the Fall Semester 2019.

Notes: Email from QU College of Law to author, supra note 65.

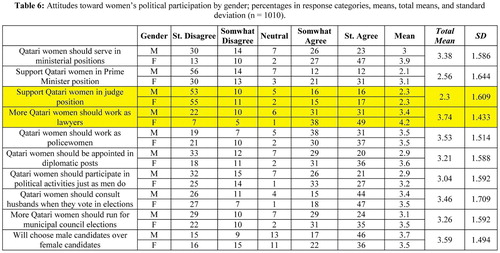

Figure 2. Table 6 from Transitional society and participation of women in the public sphere: A survey of Qatar society (emphasis added).

Notes: Al-Ghanim, supra note 98, at 57.

Qatar is progressing at lightning speed in comparison to the West (the United States only crossed the threshold of 30% feminization of the bar in 2005,Footnote66 which was 136 years after the first woman was admitted to practice law in one of its statesFootnote67) with Qatar hitting 19% feminization merely 25 years after the establishment of formal legal education.Footnote68 However, the argument should be made that legal educational providers and the profession itself need to make greater efforts to embolden women to practice law if they truly seek gender diversification of the local bar.Footnote69

Qatar’s feminization efforts

Qatar’s official policies, legislation and international accords indicate that gender diversity in Qatar’s workforce is a priority. Qatar’s constitution allows women equal rights and opportunities for education under the law.Footnote70 The Labour Law provides that women and men shall receive equal pay for equal work and that women “shall be entitled to the same opportunities of training and promotion” as their male colleagues.Footnote71 The former Human Resources Law, provided that women were entitled to paid maternity leave,Footnote72 breastfeeding hours,Footnote73 and Qatari mothers of disabled children were allowed up to three years of fully-paid disability leave.Footnote74 The new Civil Human Resources Law, provides more generous maternity leave policies and increases the leave for Qatari mothers of disabled children.Footnote75

Qatari women’s right to development is an essential element of the “Social Development Pillar” contained in Qatar’s National Vision 2030 (hereinafter “QNV 2030”).Footnote76 “Social Development” is one of four pillars deemed essential for Qatar’s modern development and encompasses the creation of “a system dedicated to social welfare and protection for all citizens and to bolstering women’s role in society and empowering them to be active community members.”Footnote77 Concrete actions towards increasing women’s empowerment were set out in the Qatar National Development Strategy 2011-2016 (hereinafter “NDS”)Footnote78 as were methods for improving women’s work-life balance.Footnote79 Qatar acceded to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women in March 2009 and continues to affirm its commitment to the same.Footnote80 Finally, H.H. Sheikha Mozah Bint Nasser Al-Misnad, mother of H.H. the Emir of Qatar, Footnote81 as well as her daughters, H.H. Sheikha Hind bint HamadFootnote82 and H.H. Sheikha Mayassa bint Hamad,Footnote83 play major roles inspiring women and promoting their advancement.Footnote84

Yet, despite the significant efforts taken by Qatar’s ruling family and governmental authorities, women’s participation in the workforce remains low.Footnote85 As stated in the NDS,

… traditional views about appropriate avenues for women’s employment (educational, administrative or clerical) prevail, despite the new opportunities created by Qatar’s economic development … Although women have higher average educational attainment level than men, there appears to be a “glass ceiling” in employment and promotion for women.Footnote86

Diversity challenges: culture, restrictive social norms & kinship systems

Cultural obstacles and more restrictive social norms arguably create the biggest barrier for feminization of the legal profession in Qatar.Footnote87 Specific expectations regarding women’s societal roles coupled with fears of earning a negative reputation in the community and the lack of role models, tend to discourage women, even those who study law, from pursuing legal careers.

While Qatar has witnessed incredible modernization efforts and increased wealth since the 1960’s, one historian noted that this accelerated modernization has not destroyed memories of tribal group power or “the lineage groupings and consequent cultural attitudes and norms of Qataris themselves as quickly as might be expected in classic Western models of development.”Footnote88 He argues that,

… the hold of tribal ‘tradition’, especially in relation to the marriage practices of women, traditional dress and expected social roles, is often increased, not decreased by wealth and the pursuit of acceptable social status within an extremely wealthy but still extremely lineage-based society.Footnote89

Qatari kinship systems also play a significant role influencing women’s employment decisionsFootnote95 and recent research argues that traditional societal roles constitute substantial obstacles to women entering male-dominated professions. In 2017, Dr Kaltham Al-Ghanim studied responses from more than 1000 Qatari nationals regarding their perceptions of women’s rights.Footnote96 She found that 70% of respondents believed Qatari women should obtain their husband’s permission prior to working and neither age nor educational attainment mattered regarding men’s attitudes in this regard.Footnote97 Additionally, she found that 65% of respondents agreed with the statement that Qatari married women should work only when they have their husbands’ permission and that the majority of respondents strongly agreed with the statement that “Only Certain Jobs Are Suitable For Qatari Women.”Footnote98 Dr Al-Ghanim also discovered about 50% of men surveyed did not believe women should work in gender-mixed workplaces while female respondents with more education were more positive about the idea.Footnote99 Dr Al-Ghanim argued that,

… women’s aspirations for work and economic advantages may encourage them to rise above certain restrictive values. Generally, the women respondents were more supportive than the men respondents to women entering new roles even though some new roles were not widely embraced by either, such as work in the media, as lawyers or judges, or military occupations.Footnote100

Yet, while Qatari society might become more accepting of women practicing law, this change does not yet appear to be encouraging more female law students to pursue legal careers. Many Qatari female undergraduate students studying law at QU express that they are not interested in becoming a licensed attorney. Overwhelmingly, the majority of female students who participate in a mandatory Externship Program during their senior (4th) year of studies prefer jobs in the government or nonprofit sectors rather than with Qatari or international law firms.Footnote104 This figure is in line with College of Law alumni statistics that measure only about 6% of total graduating students choosing to become licensed attorneys.Footnote105

Natural feminization of the Qatari bar

While research suggests that women naturally enter the practice of law as lawyer density (the number of lawyers per member of the population) increases, looking at Qatar’s attorney statistics, it is doubtful that its legal profession will naturally achieve substantial lawyer density any time soon.Footnote106

A correlation exists between increased gender diversity and a lawyer density of 2,000 people per lawyer; when the majority of countries studied achieved this level of lawyer density, they obtained at least 30% feminization of the bar.Footnote107 In Qatar, as all legal residents are entitled, and occasionally required, to access the services of the local courts, official population data suggests the country is not yet close to a lawyer density of 2,000 people per attorney. As of February 2018, Qatar’s total resident population stood at little more than 2.7 million people.Footnote108 During the same time, the Supreme Judiciary Council List of Lawyers contained 152 names.Footnote109 If we calculate the attorney density by dividing the total number of licensed lawyers by member of the population, Qatar would have a lawyer density of one lawyer per 17,766 people, nowhere near the 2,000 people per attorney bench.

However, while there might be only 152 local attorneys licensed by the State, there are many more attorneys employed by local law firmsFootnote110 and the licensed foreign law firms operating in Qatar.Footnote111 If we were to estimate that there are nearly 300 foreign licensed attorneys working in Qatar, our statistics regarding lawyer density would be different; Qatar’s lawyer density would be one lawyer per 5,974 people, much closer to the critical threshold associated with 30% feminization of the bar.

Increasing the number of attorneys in Qatar remains a challenge for two key reasons. First, the majority of residents in Qatar are not Qatari citizens, but legal residents holding visas that require regular renewal.Footnote112 Second, Qatar’s “Advocacy Law” and its amendments, which govern the legal profession, specifically state that one of the requirements to the admission of the practice of law in Qatar is Qatari citizenship or G.C.C. citizenship “on the condition of dealing with reciprocity and subject to the approval of the Committee.”Footnote113 Given the limited number of Qatari citizens and the current political disputes within the G.C.C., it is doubtful that Qatar’s legal profession will substantially increase to the levels correlating with increased feminization in the near future.Footnote114

Further, it is important to note that even if Qatar’s legal population did rapidly attain a lawyer density near 2,000 people per attorney, it remains unlikely that 30% of those attorneys will be women absent significant cultural, social and legal changes.Footnote115 Dr Cynthia Fuchs Epstein, a prominent sociologist and author of what is widely considered the pioneering research regarding the socio-historical circumstances of women entering the legal profession in the United States, remarked on this more than 30 years ago.

The future of women in the legal profession cannot be viewed as a simple progression from exclusion to inclusion, with accession to all the rights, privileges, and responsibilities due to any true member of the profession. As in the past, women’s future position in the legal world will not depend solely on women’s own ambitions, interests, or legal abilities, but on how receptive others may be to these characteristics. It will depend on the disappearance of the stereotypes that define women as unlikely professional partners for men. It will also depend on the decision of the men who guard the gates to the inner core of professional life at all strata of the bar … Footnote116

Overcoming obstacles: learning from other cultures

In order to encourage more Qatari women to pursue legal careers, it is important to understand why previous generations of women, albeit from other cultures, chose to pursue legal careers so we may better harness and amplify those motivations in Qatar. As an example, in the United States, women’s entrance into the profession was slow until the 1970’s.Footnote121 Despite the fact that women accounted for 1.1% of all licensed attorneys by 1910, women constituted merely 4.7% of all licensed attorneys six decades later in 1970.Footnote122 As law school enrollments nearly doubled between 1963 and 1978,Footnote123 and as the number of lawyers increased by 33% in less than a decade,Footnote124 the United States witnessed a massive growth in women lawyers in the 1970s and 1980s.Footnote125

In her seminal book, Dr Fuchs Epstein remarked on several shared characteristics of the women lawyers she interviewed. First, the parents of the women lawyers were more educated than other parents.Footnote126 Second, a significant percentage, almost a quarter, of the mothers of the women lawyers had a college or professional degree.Footnote127 Third, researchers found a statistically significant correlation between a mother’s education when it was related to the encouragement of her daughter’s education.Footnote128 Fourth, a significant amount of the women lawyers expressed that their mothers possessed “unusual vigor and managerial skill” and described their mothers as “doers,” in either a professional or avocational sense.Footnote129 Fifth, “women who attended college in the 1960’s and 1970’s were more affected by their peers in deciding on law as a career than preceding generations.”Footnote130

In Qatar, female law students and lawyers today share many of these same characteristics that Dr Fuchs Epstein’s subjects did in the 1960’s and 1970’s. First, more young women than ever before in the nation’s history have educated parents. Recently reported education statistics show that, as of 2015, the population of Qatari men with university or higher graduate degrees was 29.2% and the population of Qatari women with university or higher graduate degrees was 37.2%.Footnote131 Second, the statistics show that Qatari females constitute the highest proportion of university graduates at 31% followed by non-Qatari female graduates at 27%.Footnote132 Recent datasets collected by the Social and Economic Survey Research Institute (SESRI) and World Values Survey indicate that a significant majority of Qatari respondents, just over 93% of males and 95% of females, strongly agreed with the statement that one of their main goals was to make their parents proud.Footnote133 Other datasets collected by SESRI regarding education in Qatar showed that Qatari men and women who had completed a university degree were more likely to pay for tutors for their children than Qatari men and women without university degrees.Footnote134

Third, while we might not yet have statistical data in Qatar showing a link between educated parents and parental, particularly motherly, encouragement of their daughters’ education with a higher probability of daughters becoming legal professionals, we do have anecdotal evidence. At Qatar’s first Women in Law Conference held on 22 March 2018, many of the prominent Qatari legal professionals spoke about or alluded to their families supporting their higher education and career choices, despite those career choices being considered socially deviant in the general community.Footnote135

Women should join the courtroom. In 1985, it was the first year that Qatari ladies were allowed to study abroad. So, I went to Egypt to study law. I graduated from Cairo and joined the Ministry of Justice. Qatar did not have an Office of Public Prosecution at that time. [When the Office of Public Prosecution was created,] I was one of the first ladies who joined. It wasn’t easy. A young lady? I was one woman out of 70 people who joined [the office]. It was in 2003, Family Prosecution. Now I am Head of Juvenile and Family Prosecution.Footnote136

Fifth, with respect to the role and influence of peers, a recent study confirmed Dr Fuchs Epstein’s previous findings in a modern context, by arguing that in socially restrictive cultures “where social norms limit women’s interactions with strangers, it is important to ask whether training with self-identified friends (with whom interactions are likely less restricted) can have an impact.”Footnote141 The scholars concluded that women belonging “to more restrictive social groups were particularly sensitive to peer involvement” and were significantly more likely to change business and financial behavior when they had peer support than women from less socially restricted cultures.Footnote142 In Qatar, this same phenomenon has been observed at QU College of Law through its Externship Program. After analyzing participation data collected from 394 female law students during the course of 11 academic semesters, this author discovered that female law students self-selected to attend externships with female peers more than 60% of the time. During all semesters analyzed, only 149 female students, about 38%, had chosen to be the single female student participating in an externship alone with an employer. The majority of female students chose to participate with at least one female peer. By contrast, male students opted to participate as the only male student during an externship experience 46% of the time.

While seemingly different at first glance, upon closer inspection, Qatari women entering the law today share common traits with American women who entered the law in the 1960s and 1970s. As Dr Fuchs Epstein has noted, in the 1960s and 1970s many complex factors led to the dramatic growth in women’s law school enrollment in the United States including, an increase in demand for legal services due to a growing economy, increasing community concern for individual rights and egalitarianism, rising attorney salaries, more complex and increased government regulation, and a substantial amount of youth interested in pursuing law to accomplish socially oriented goals.Footnote143 Today, in Qatar, most if not all of these same factors are currently influencing Qatar’s legal profession as the State increasingly plays a more significant role in world business and politics.Footnote144 Similarly, in the 1960s and 1970s, female attorneys entering the job market faced career choices “structured by the interplay between discrimination, adaptation to that discrimination, and opportunity.”Footnote145 Today, in Qatar, as was the same in America in the 1960’s and 1970’s, many legal employers believe that women’s clustering in certain professions, such as government employment, reflects women’s preferences, and not necessarily the results of a system of gender stereotyping, explicit and implicit discrimination, and bias.Footnote146 While some members of the local community openly object to women working in certain legal careers,Footnote147 due to religious or cultural views,Footnote148 the more common view is subtler and protective; that women themselves prefer lower-ranking legal specialties and/or jobs that compete less with women’s home life and family roles.Footnote149

When I applied to be a judge, there were no forms for applying. So, I gave my papers to the clerk and waited for a year and worked [in another job]. Finally I heard that they were interviewing judges and [I went]. The Chief told me my application never reached him. Sometimes [the Ministry employees] were not referring female applicants. There were more than 50 men who showed up for interviews and I was the only woman. During my interview the first question was, “Can you do the job if you get married? Can you balance your job and family and children?” After the interview, I doubted [I would get an offer] but then I was accepted with three other [women].Footnote150

Conclusions

Western scholars predominantly argue that diversity in the legal profession is important because it reflects the profession’s core ideals: equality, access to justice and the elimination of bias and discrimination.Footnote152 The ABA has argued that when the bar reflects a diverse array of lawyers and the bench reflects a diverse array of judges, the public has “greater trust in the mechanisms of government and the rule of law.”Footnote153 The ABA has also argued that, as a population ages and becomes more ethnically, racially and culturally diverse, so should the population of professionals in the legal field.Footnote154 The U.S. Supreme Court remarked that diversity is important because law graduates often possess the skills and social networks preferred for civic leadership positions and frequently represent a significant proportion of a country’s leadership.Footnote155 Industry has shown that in an increasingly multinational and cross-cultural business world, a more diverse team offers different perspectives, life experiences, linguistic skills, knowledge about international markets, legal regimes, different geographies, and current events, which makes those law offices more effective for their clients.Footnote156

While some of these rationales resonate more readily in Western democracies than in Qatar,Footnote157 they all remain important considerations for Qatar’s continued legal diversity efforts, at least regarding gender. The “Leadership Rationale”Footnote158 applies in Qatar, where many law graduates hold prominent positions in governmental ministries and the private sector and also comprise some of the Emir’s close advisors. In fact, the Prime MinisterFootnote159 and three out of 14, or 21%, of the members of Qatar’s Council of Ministers hold law degreesFootnote160 while one Minister holds degrees in Sharia.Footnote161 The “Business Rationale”Footnote162 also applies in Qatar as findings from G.C.C. data collected in 2014 suggest that G.C.C. companies and law firms would do well to add more women to top leadership positions.

Female leaders in the GCC countries exhibit four leadership behaviors correlated with organizational effectiveness more often than their male counterparts do: inspiration, people development, efficient communication, and participative decision-making. Three of these behaviors are among the leadership styles that [McKinsey’s] global survey of top executives found the most effective in addressing the global challenges of the future … .Footnote163

Acknowledgements

This paper was made possible by NPRP grant #9-341-5-047 from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation). The statements made herein are solely the responsibility of the author. Thank you to Arnaud Montouché, Emily Tomczak, Sara A. AlMohanadi, Maryam A. Al-Maraghi, Amna A. Al-Ansari, the AALS Externship Scholarship Committee’s inaugural Works-in-Progress participants, Paula M. Young of Qatar University, Carole Heyward of Cleveland State, and the anonymous peer reviewers for their constructive feedback and insight during the revision process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 ABA Sec. of Litig. 2011 Corp. Couns. CLE Seminar, Diversity in the Legal Profession: The Next Steps, 5, (Feb. 17–20, 2011), https://apps.americanbar.org/litigation/committees/corporate/docs/2011-cle-materials/08-Staying-The-Course/08a-diversity-legal-profession%20.pdf.

2 See ABA Diversity & Inclusion Portal, https://www.americanbar.org/diversity-portal.html (last visited Nov. 19, 2017); see also ABA Ctr. for Prof. Resp., Diversity Initiatives, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/cprdiversityplan.html (last visited Oct. 30, 2017); see also ABA Comm. on Women in the Prof., Goal III Report: An Annual Report on Women’s Advancement into Leadership Positions (Apr. 2017), https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/women/2016_goal3_women.authcheckdam.pdf; see also Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of L. Schools §205 (Am. Bar Ass'n 2017); see also Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of L. Schools §206 (Am. Bar Ass'n 2017).

3 See The Law Society, Diversity Profile of the Solicitors’ Profession 2015, 2, (Oct. 2016), https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/support-services/research-trends/promoting-diversity-in-the-legal-profession/.

4 See Avocats Barreau Paris, Valeurs et missions, Egalité Professionnelle, https://www.avocatparis.org/nos-engagements/valeurs-et-missions/egalite-professionnelle/le-barreau-de-paris-signe-le-pacte-de (last visited Jan. 28, 2018).

5 Id. at https://www.avocatparis.org/nos-engagements/valeurs-et-missions/egalite-professionnelle/le-barreau-de-paris-vote-pour-legalite (last visited Jan. 28, 2018).

6 See The Peninsula Qatar, Role of women in legal field stressed (Mar. 26, 2018), https://www.thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/26/03/2018/Role-of-women-in-legal-field-stressed, see also Al Raya Newspaper Qatar, طالبن بوضع تصور علمي لمستقبل المرأة … قانونيات لـ الراية (Mar. 23, 2018) https://www.raya.com/news/pages/7ebd57a6-004c-4890-9559-b2ba4b04ffac (Qatar’s first Women in Law Conference was held on Mar. 22, 2018. The conference explored: women in leadership; initiatives law firms and departments have taken to increase women in Qatar’s legal profession; the realities of gender bias in Qatar; how to use GRIT and Growth Mindset to advance women in the profession; popular literature related to success; women in the courtroom; and how women should approach salary negotiations.)

7 Qatar Tourism Authority, Nat’l Profile: https://www.visitqatar.qa/learn/essential-qatar/national-profile.html (last visited Feb. 24, 2018).

8 Qatar Tourism Authority, supra note 8.

9 See CIA The World Factbook ‘Qatar’, Population: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/qa.html (last visited Feb. 24, 2018) [hereinafter CIA].

10 CIA supra note 10 at Introduction and Economy (last visited Feb. 24, 2018).

11 Sandy Ogilvy, A Concise History of Field Placements, Handout from Externships 9: Coming of Age Conf., Plenary I: How Far We Have Come & How Far We Need To Go, U. of Georgia School of L., Athens, GA (Mar. 9, 2018).

12 See Nat’l Ass’n of Women Law., NAWL History page, https://www.nawl.org/p/cm/ld/fid=20 (last visited Mar. 26, 2018).

13 Id.

14 See Zekeriya Kurşun, The Ottomans in Qatar, 15–16 (The Isis Press Istanbul, 2002), see also Allen J. Fromherz, Qatar: A Modern History, 60–61 (I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2012), see also David B. Roberts, Qatar: Securing the Global Ambitions of a City-State, 17 (London, Hurst & Company, 2017). (The Ottomans invaded Qatar in 1871 were repelled by the Qataris during the Battle of Wajbah in 1893.)

15 Nat’l Ass’n of Women Law., supra note 13.

16 Id.

17 Ogilvy, supra note 12 (showing that by 1917, in the U.S., there were 146 law schools enrolling 24,503 law students); see also Fromherz, supra note 15, at 1, 74–75; and Roberts supra note 15 at 17–18 (citing Michael Field, The Merchants: The Big Business Families of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States, 210 (Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press, 1985) and Rosemarie Said Zahlan, Creation of Qatar, 15 (Croom Helm London, 1979) and Jill Crystal, Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rulers and merchants in Kuwait and Qatar, 117 (Cambridge Univ. Press 1990). (showing that the collapse of the pearl industry during the 1920’s caused significant hardship to the Qatari population. Later deemed the ‘years of hunger’ it is estimated that the population of Qatar fell from almost 30,000 people in 1908 to around 10,000 inhabitants during the 1930’s. By 1940, the population of Qatar was estimated to contain about 16,000 residents but the British Political Resident described Doha as, ‘little more than a miserable fishing village straggling along the coast for several miles and more than half in ruins.’)

18 See Crystal supra note 18, at 117.

19 See Crystal supra note 18, at 117–119. (The discovery of oil in 1939 initially did not bring significant changes to Qatar’s economy or its population due to World War II. However, once the Petroleum Development Qatar Limited oil company began exporting oil in 1949, dramatic increases in revenue created substantial changes to the Qatari economy, population and modern development.).

20 See Abeer Abu Saud, Qatari women, past and present, 173 (Longman 1984). (Note that prior to 1956, there were Koranic schools and the author refers to the first attempt of a modern school which closed in 1938 due to lack of funding.); See also Crystal supra note 18, at 128 (citing Nasir Muhammad al-Uthman’s 1980 statement in Arabic that, “the first modern school, Islah al-Muhammadiyya, opened in 1949, offering history, math, geography and some English.”)

21 For a more in-depth discussion of the Mutawa and Katateeb see: Ali Alhebsi, Lincoln D. Pettaway and Lee “Rusty” Waller, A History of Education in the United Arab Emirates and Trucial Sheikdoms, The Global ELearning J. Vol. 4, Issue 1, 1–7, (2015) [hereinafter Alhebsi](‘Mutawa’ pronounced MOO-TA-WAH; ‘Katateeb’ pronounced EL-QUAY-TEH-TEEB).

22 Alhebsi, supra note 22, at 2. (The Mutawa is another name for the Imam of the Mosque (the religious leader of the community) who traditionally taught children moral obligations as well as how to read the Quran. The Mutawa typically educated students in his home or in the local Mosque. In more affluent communities, students were educated in the Katateeb; a specific physical location resembling modern primary schools where students learned the Holy Quran, Islamic teachings, writing, reading, and basic mathematics.)

23 See Saud supra note 21, at 173.

24 See Saud supra note 21, at 173.

25 Id. at 174.

26 See Id., see also Qatar U., Our History, https://www.qu.edu.qa/theuniversity/history.php (last visited July 15, 2016), see also Joy S. Moini, et al., The Reform of Qatar University, xviii- xix (RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA 2009), https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG796.html (last visited July 15, 2016) (Initially, the school offered two distinct Colleges of Education, one for men and one for women.)

27 See Saud supra note 21, at 174.

28 See Id.; see also Qatar U. C. of Law, Dean’s Message: Welcome to the College of Law, https://www.qu.edu.qa/law/about_us/college/ (last visited July 15, 2016); and Martin Partington, Qatar Int’l Ct. & Dispute Resolution Ctr, The Development of Professional Legal and Judicial Training in Qatar 17 (2012).

29 See Moini et al., supra note 27, at xiii, xix (The six colleges were: (1) Education; (2) Humanities and Social Sciences; (3) Science; (4) Sharia, Law, and Islamic Studies; (5) Engineering; and (6) Business and Economics).

30 Id. at 9–10.

31 See Qatar U. C. of Law, https://www.qu.edu.qa/law/about_us/History.php (last visited July 15, 2016).

32 Dr Mohamed Al-Khulaifi, Dean of Qatar U. C. of Law, Address at the Annual Law School Dinner (Sept. 3, 2015).

33 Interview with Fatma M. Al-Mesleh, Associate Dean of Student Affairs, Qatar U. C. of Law, in Doha, Qatar (Oct. 6, 2017) (Compiled during Oct. 2017, data showed there were: 382 male freshman students (347 Qatari); 89 male sophomore students (77 Qatari); 43 male junior students (32 Qatari); 43 male senior students (32 Qatari); 18 male private law LLM students (14 Qatari); 31 male public law LLM students (28 Qatari); 507 female freshman students (441 Qatari); 273 female sophomore students (241 Qatari); 180 female junior students (144 Qatari); 151 female senior students (128 Qatari); 35 female private law LLM students (26 Qatari); and 28 female public law LLM students (27 Qatari).

34 (huge thanks to Maryam Abdulla Al-Mannai, my Honors student, for compiling this information)

35 See Police C. website, https://www.moi.gov.qa/policecollege/ (last visited Mar. 25, 2018) (Emiri decree (161) for 2013.)

36 See Id. at Study Plan page, https://www.moi.gov.qa/policecollege/studying_plan.html (last visited Mar. 25, 2018).

37 See HBKU C. of Law, About the College of Law, https://www.hbku.edu.qa/en/cl/about (last visited Dec. 2, 2019).

38 See Id.

39 See U. of Sussex, https://www.sussex.ac.uk/study/masters/courses/law-politics-and-sociology/corruption-law-and-governance-delivered-in-qatar-llm (last visited Mar. 25, 2018); see also Peninsula Newspaper, ROLACC opens online applications for LLM, (Jan. 31, 2018), https://thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/31/01/2018/ROLACC-opens-online-applications-for-LLM.

40 See Centre for the Study of Corruption, official blog for the Centre for the Study of Corruption at the University of Sussex, First set of students graduate on University of Sussex’s LLM in Corruption, Law and Governance in Doha, Qatar, https://scscsussex.wordpress.com/2018/12/28/first-set-of-students-graduate-on-university-of-sussexs-llm-in-corruption-law-and-governance-in-doha-qatar/ (Dec. 28, 2018) (last visited Oct. 7, 2019).

41 Peace be Upon Him.

42 See Fromherz, supra note 15, at 29.

43 (‘hakam’ pronounced HA-KM).

44 Fromherz, supra note 15, at 29.

45 See Partington, supra note 29 at 14.

46 See Dr Yousof Ibrahim Al-Abdulla, A Study of Qatari-British Relations 1914–1945, Thesis for (M.A.) MacGill Univ. Montreal, 2nd ed., page 102 (2000) (Appendix IV contains a letter drafted by the Office of the Political Resident in the Persian Gulf on Apr. 17, 1935 to Shaikh Abdullah bin Qasim al Thani, Ruler of Qatar, stating, His Majesty’s Government have learnt of the proposal made in the second sub-paragraph of the Eighteenth Article of the Draft Concession which you recently gave to Mr Mylles in the course of the negotiations which have been taking place between you and him and which reads as follows : ‘If any dispute or quarrel should take place between any of the foreign employees of the Company, and any of the Shaikh’s subjects, their trial shall be held before the shaikh [sic] and in his Shara (Religious) Courts.’ I have been instructed by His Majesty’s Government to inform you in regard to this that this condition is one of which they cannot approve, and that an indispensable pre-condition of their approval to the grant by you of any concession, to whomsoever it may be, is a definite understanding that Jurisdiction over the person and property of British and British protected subjects and of the subjects of non-Moslem [sic.] foreign powers will lie solely with His Majesty’s Government.)

47 See Fromherz, supra note 15, at 66–73; see also Roberts supra note 15 at 17. (H.H. Sheikh Abdulla bin Jassim Al-Thani signed a formal treaty on Nov. 3, 1916 that, although not specifically saying so, served as the legal foundation for granting Qatar protectorate status with the British government.)

48 See Gabriela Knaul (Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers), Rep. of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers on her mission to Qatar, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/29/26/Add.1, at 4–5 (Mar. 31, 2015) [hereinafter Knaul]; see also Partington, supra note 29, at 14.

49 See Knaul, supra note 59, at 4–5; see also Partington, supra note 29, at 14.

50 See Supreme Judiciary Council List of Lawyers, https://www.sjc.gov.qa/ar/Pages/Lawyers.aspx (last visited Oct. 7, 2019) [hereinafter List of Lawyers].

51 See Qatar Lawyer’s Ass’n, Board of Directors, https://www.qla.qa/bod/ (last visited Mar. 25, 2018).

52 Interview with Fatma M. Al-Mesleh, Associate Dean of Student Affairs, Qatar U. C. of Law, in Doha, Qatar (Mar. 25, 2018).

53 ‘Judge Assistant’ is an unofficial translation of: دورات تدريبية لمساعدي القضاة

54 ‘Assistant Prosecutor’ is an unofficial translation of: دورات تدريبية لمساعدي النيابة العامة

55 ‘Lawyer’ is an unofficial translation of: دورات تدريبية للمحامين تحت التدريب

56 ‘Legal Researcher’ is an unofficial translation of: دورة تدريبية للباحثين القانونيين الجدد

57 Email from Hazem T. Aboulezz, Legal Researcher, Center for Legal & Judicial Studies, to Noof M. Al-Sobai, Honors student, Qatar University (Mar. 22, 2018 7:44AST) (on file with author) (huge thanks to Noof M. Al-Sobai, my Honors student, for compiling this information).

58 See Knaul, supra note 59, at 15. (Unfortunately, despite our best efforts, we were unable to procure more recent statistics regarding the total number of judges currently in Qatar).

59 See Partington, supra note 29, at 16 (stating Simmons & Simmons (UK); Patton Boggs, now Squire Patton Boggs (U.S.); and UGGC (Fr.) are the only foreign law firms licensed to practice law under the Ministry of Justice; note that UGGC stopped operating in Qatar during 2015).

60 See Qatar Fin. Centre, Pub. Register, https://www.qfc.qa/en/Operate/CRO/Pages/PublicRegister.aspx (last visited Mar. 25, 2018).

61 Interview with Fatma M. Al-Mesleh, Associate Dean of Student Affairs, Qatar U., C. of L., in Doha, Qatar (Oct. 6, 2017).

62 GCC women power through glass ceiling, Arab News (Apr. 16, 2015, 3:00 AM) https://www.arabnews.com/middle-east/news/733126 (showing that Mariam Abdullah Jaber was appointed the first District Attorney in Qatar in 2003); see also Hiba Fathi, مريم الجابر لـ «العرب »: لا توجد نيابات حكراً على الرجال , AlArab Newspaper (Feb. 2, 2017, 1:53 PM) https://www.alarab.qa/story/1087485/مريم -الجابر-لـ-العرب -لا-توجد-نيابات -حكرا-على -الرجال (showing that Maryam’s sister, Amal Jaber, became Doha’s second female prosecutor).

63 Email from Fatma Al-Mal, Judge, State of Qatar Supreme Judiciary Council, to author (Mar. 11, 2018, 15:22AST) on file with author (The four women who have already trained as Judge Assistants and are now Judges are: Fatma Al-Mal, a criminal judge, and Aisha AlEmadi, Hessa AlSulaiti, and Maha AlThani, who are civil judges); Interview with Reem AlNaimi, Judicial Assistant, State of Qatar Supreme Judiciary Council, in Doha, Qatar (Nov. 22, 2017) (The three women who are training as Judicial Assistants and will eventually seek appointment as Judges are: Reem AlNaimi, Eman Al-Shahrani and Mariam Al-Hudaifi. Note that during Mar. 2018, the Supreme Judiciary Council announced that Sara M. Al-Mesleh had been chosen to participate as a Judge Assistant and possible future judge pending training.)

64 See List of Lawyers, supra note 61 (which lists 29 registered female attorneys out of a total of 152 registered attorneys (19%) and 27 registered Qatari female attorneys (17.76%) (huge thanks to Maryam Yaqoub Al-Jefairi, my Honors student, for compiling this information).

65 Email from QU College of Law to author, entitled “LAWC Directory fall 2019 – دليل أعضاء كلية القانون خريف 2019” (Sept. 26, 2019) (on file with author).

66 Ethan Michelson, Women in the Legal Profession, 1970–2010: A Study of the Global Supply of Lawyers, Indiana J. of Global Legal Studies Vol. 20, Issue 2, 1071–1137, 1083 (2013).

67 See Nat’l Ass’n of Women Law., supra note 13 (to see that in 1869, Arabella Babb Mansfield became the first American woman lawyer admitted to the bar); See also Cynthia Fuchs Epstein, Women in Law 37 (3rd ed. 2012).

68 See Michelson, supra note 66, at 1082. (Figure 1. Feminization of Legal Professions in Eighty-Six Countries, 1960–2010, shows that the U.S. achieved 19% feminization of the bar around 1985).

69 See Knaul, supra note 59, at 15, (noting that in 2015, only two out of 198 judges were female); See also Qatari Law. Ass’n, supra note 62, (noting that one female attorney, Aisha Saad Nasser, is a member of the Qatari Law. Ass’n Board of Directors).

70 Permanent Constitution of State of Qatar, Arts. 34–35, 49 (Qatar); see also Qatar’s Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, Qatar’s Fourth National Human Development Report: Realising Qatar National Vision 2030, The Right to Development, 51, (June 2015) [hereinafter HDR 4] https://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/knowledge/Doc/HDR/Qatar_Fourth_National_HDR_Realising_QNV2030_The_Right_to_Development_2015_EN.pdf.

71 Law 14 of 2004, on the promulgation of Labour Law, art. 93 (Qatar) (Jul. 6, 2004) https://www.almeezan.qa/LawArticles.aspx?LawTreeSectionID=12652&lawId=3961&language=en.

72 Law 8 of 2009, on Human Resources Management, art. 108 (Qatar) (Apr. 23, 2009) https://www.almeezan.qa/LawPage.aspx?id=2644&language=en.

73 Id. at art. 109.

74 Id. at art. 110.

75 Law No. 15 of 2016, on the promulgation of the Civil Human Resources Law, arts. 73 & 74 (Qatar) (Nov. 23, 2016) https://www.almeezan.qa/LawPage.aspx?id=7102&language=ar.

76 See General Secretariat For Development Planning, Qatar National Vision 2030, (July 2008) [hereinafter QNV] https://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/qnv/Documents/QNV2030_English_v2.pdf; see also HDR 4, supra note 71, at 49–68.

77 Qatar National Vision 2030 Social Development page, Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, https://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/qnv/Pages/SocialDevelopment.aspx, (last visited Sept. 10, 2018); see also QNV, supra note 86.

78 Qatar General Secretariat for Development Planning, Qatar National Development Strategy 2011–2016, Towards Qatar National Vision 2030, 175–176 (March 2011) [hereinafter NDS], https://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/nds/Documents/Downloads/NDS_EN_0.pdf.

79 Id. at 174–175.

80 See U.N. Comm. on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women : initial reports of States parties / Qatar, at 3, U.N. Doc. CEDAW/C/QAT/1 (21 Mar. 2012) [CEDAW]; see also Qatar ‘committed to protecting rights of women’, Gulf Times (Oct. 11, 2017, 11:34 PM) https://www.gulf-times.com/story/567060/Qatar-committed-to-protecting-rights-of-women.

81 H.H. Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad Al Thani

82 See Sheikha Hind underlines interconnection between education, sustainable development, The Peninsula Qatar (Jul. 9, 2019) https://thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/11/07/2019/Sheikha-Hind-underlines-interconnection-between-education,-sustainable-development

83 Qatar has made great strides in gender equality: Mayassa, Gulf Times (Mar. 14, 2019) https://www.gulf-times.com/story/624915/Qatar-has-made-great-strides-in-gender-equality-Ma

84 CEDAW 1, supra note 30, at 8; see also Gender Equality, The Peninsula Qatar (Mar. 20, 2019) https://www.thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/20/03/2019/Gender-equality

85 State of Qatar, Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, Statistics, Topics Listing, Labour Force, Quarterly Bulletin – Labour Force Survey, First Quarter (Q1) 2018, table 1, Figure 1 (2018) (on file with author) (showing that for Q1 of 2018, there were 66,985 economically active Qatari males and 37,720 economically active Qatari females. 68% of Qatari men were economically active while only 37% of Qatari women were economically active).

86 NDS, supra note 88, at 175.

87 See Rania Maktabi, Female lawyers on the rise in Kuwait: Potential agents of reform?, Nat’l U. of Singapore Middle East Institute, Middle East Insights, Insight No. 163, (May 23, 2017), https://mei.nus.edu.sg/themes/site_themes/agile_records/images/uploads/Download_Insight_163_Maktabi.pdf (for a discussion regarding statistics of female lawyers and female law students in Kuwait); see also Katherine Zoeph, Sisters in Law, The New Yorker, Letter from Jeddah, (Jan. 11, 2016) https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/01/11/sisters-in-law, (for a general discussion regarding female law students in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia).

88 Fromherz, supra note 15, at 4.

89 Fromherz, supra note 15, at 8.

90 Professor Mokhtar M. Metwally, Nat’l Center for Economic Research, U. of Qatar, Determinants of National Employment in the State of Qatar, 87 (Jan. 2002).

91 Id. at 88.

92 Id. at 95.

93 Id.

94 State of Qatar, Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, Statistics, Topics Listing, Labour Force, Quarterly Bulletin – Labour Force Survey, First Quarter (Q1) 2018, table 12 (2018) (on file with author) (showing that for Q1 of 2018, only 33% of Qatari women were willing to work in the private sector versus 50% of Qatari men).

95 Fromherz, supra note 15, at 5–7. (Fromherz makes persuasive arguments about philosophical and sociological perspectives regarding tradition and modernity and that Western perspectives regarding anomie do not apply as well to Qatar).

96 Dr Kaltham Al-Ghanim, Transitional society and participation of women in the public sphere: A survey of Qatar society, Int’l J. of Humanities and Social Science Research, Volume 3, Issue 2, 51–63, (Feb. 2017).

97 Al-Ghanim, supra note 98, at 56.

98 Id. at 56–57.

99 Id. at 56.

100 Id.

101 Al-Ghanim, supra note 98, at 57.

102 Id.

103 Id.

104 See Melissa Deehring, Five Years Later : Why More Gulf Law Schools Should Add an Externship Pedagogy, Nat’l U. of Singapore Middle East Institute Insights, Rule of Law Series, MEI Insight No. 160, 3–4, (Feb. 13, 2017), https://mei.nus.edu.sg/publication/insight-160-five-years-later-why-more-gulf-law-schools-should-add-an-externship-pedagogy/.

105 Interview with Fatma M. Al-Mesleh, Associate Dean of Student Affairs, Qatar U., C. of L., in Doha, Qatar (Mar. 23, 2018).

106 Michelson, supra note 66, at 1075; … lawyer feminization in most parts of the world corresponds closely to the expansion of lawyer populations. In most countries, achieving a critical threshold density of lawyers (the number of people per lawyer) is a precondition of achieving a critical threshold proportion of lawyers who are women. Very rarely have countries reached a significant level of lawyer feminization via pathways that do not include significant bar expansion. Id.

107 Id. at 1084–1086.

108 See Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics website, Monthly figures on total population page, https://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/statistics1/StatisticsSite/pages/population.aspx (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (showing the total population was 2,700,390 with 2,017,612 males and 682,778 females).

109 See List of Lawyers, supra note 61.

110 Quick internet searches of Qatari law firm websites show that, in addition to the Qatari lawyers, there are more than 80 foreign attorneys working in seven large Qatari law firms. See Ghada Darwish Law Firm website, Our Team page, https://gdarwish.com/our-team/ (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (four foreign attorneys); see also Sultan Al-Abdulla & Partners website, Professionals page, https://qatarlaw.com/professionals/ (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (18 foreign attorneys); Al Sulaiti Law Firm website, Our Team page, https://alsulaitilawfirm.com/team (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (23 foreign attorneys); Al-Ansari & Associates website, People page, https://www.alansarilaw.com/all-people/ (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (10 foreign attorneys); Law Offices of Gebran Majdalany website, Professionals page, https://www.gebranmajdalany.com/professionals.html (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (13 foreign attorneys); Khalid Al-Attiya Law Firm website, Firm Lawyers page, https://www.alattiya-legal.com/firm_lawyers (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (nine foreign attorneys); Mashael Al-Sulaiti for Legal Advocacy & Arbitration website, Our People page, https://sulaitilaw.com/Our-People.html (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (four foreign attorneys).

111 Quick internet searches show the two Ministry of Justice licensed foreign law firms employing 22 foreign attorneys. See Simmons & Simmons website, https://www.simmons-simmons.com/en/People/Contacts?page=2&firstname=&lastname=&Regions=Middle+East&mode=2 (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (11 foreign lawyers); see also Squire Patton Boggs website, https://www.squirepattonboggs.com/en/locations/doha?explore=team (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (11 foreign lawyers). Quick internet searches show seven of the 26 QFC licensed law firms employing more than 60 foreign lawyers. See Clyde & Co. website, https://www.clydeco.com/locations/office/doha (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (15 foreign lawyers); Al Tamimi Law Firm website, https://www.tamimi.com/our-firm/find-a-lawyer/?searchLocation=1471 (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (14 foreign lawyers); K&L Gates website, https://www.clydeco.com/locations/office/doha (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (nine foreign lawyers); Dentons website, https://www.dentons.com/en/our-professionals/people-search-results?Locations={F77E12C3-5200-44E9-AAB6-1D5C2897FA64} (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (nine foreign lawyers); Eversheds website, https://www.eversheds-sutherland.com/global/en/where/middle-east/qatar/people/index.page? (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (eight foreign lawyers); Pinsent Masons website, https://www.pinsentmasons.com/en/people/?regions=408 (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (four foreign lawyers); Allen & Overy website, https://www.allenovery.com/search/Pages/peopleresults.aspx?k=*&r=aooffice%3d%22AQREb2hhCGFvb2ZmaWNlAQFeASQ%3d%22&officeid=738aa486-ad56-11e0-b8b7-68e94724019b (last visited Mar. 26, 2018) (four foreign lawyers).

112 For a description about how Qatar’s immigration system affects the independence judicial and legal system see, Knaul, supra note 59, at 11; For demographic estimates regarding the nationality of Qatar’s residents see Gulf Labour Markets and Migration website, https://gulfmigration.eu/qatar-estimates-foreign-residents-qatar-country-citizenship-selected-countries-c-2015-2016/ (last visited Mar. 19, 2018).

113 See Law 23 of 2006 regarding Enacting the code of law practice, art. 13 (Qatar) (June 29, 2006) and Law 1 of 2018 regarding Amending the Legal Practice Law promulgated by No. 23 of 2006, art. 13 (Qatar) (Jan. 2, 2018).

114 The G.C.C. nations of Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the U.A.E., have initiated a political blockade against Qatar since June 5, 2017, during which time their citizens have been advised to leave Qatar. See AlJazeera, Qatar: Beyond the Blockade (Feb. 15, 2018) https://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/specialseries/2018/02/qatar-blockade-180212075226584.html.

115 For a detailed description of the complex interplay of factors that contributed to the increase of women in law in the United States see, Fuchs Epstein, supra note 68 at 9–33; Thus growth [of the legal profession], the changing shape of the profession, the move toward egalitarianism and the legal machinery to achieve it, the undermining of the gate-keeping function of the professional elitists, pressure from groups such as black and women’s movement activists, and government regulation have created an opening of structure and opportunities in the late 1960s and 1970s. Id. at 16.

116 Id. at 304.

117 HDR 4 supra note 71, at 67–68. While society recognizes the capacities of women as workers, it does not recognize their capacities as leaders, with only 32% viewing women capable of performing a leadership role … there is an obvious need for public education on the advantages of women’s leadership and gender equalities.

118 Al-Ghanim, supra note 98, at 56. (Showing that the majority of respondents strongly agreed that Qatari women should consult with their husbands before voting in elections and indicated an automatic preference for male political candidates based on no other factor than gender.)

119 As an example, See Law 14 of 2004, on the promulgation of Labour Law, art. 94 (Qatar) (Jul. 6, 2004) (translated into English as “Women shall not be employed in dangerous arduous works, works detrimental to their health, morals or other works to be specified by a Decision of the Minister”), see also Id. at art. 95 (“Women shall not be employed otherwise than in the times to be specified by a Decision of the Minister.”).

120 See as example Middle East Media Research Institute, Qatari TV Host Ali Al-Muhannadi: Women Must Leave the House as Little as Possible and Obtain Husband's Permission Whenever They Do, TV Monitor Project, Clip 7316 (Jun. 3, 2019) https://www.memri.org/tv/qatari-host-rashid-muhannadi-woman-wife-leave-house-husband-permission-enter-paradise-sin/transcript.

121 Fuchs Epstein, supra note 68, at 2–3.

122 Fuchs Epstein, supra note 68 at 2.

123 Id. at 12 (United States law school enrollments increased from 54,000 to 126,000 between 1963 and 1978.)

124 Id. at 11–12 (Between 1960 and 1969, the number of practicing attorneys in the United States increased by 33% which was a significant increase from the 14% growth the profession witnessed a decade earlier).

125 Id. at 3 (“After decades of virtually no movement, the number of women lawyers grew radically in the decade of 1970 to 1980, from 13,000 to 62,000 (from 4% to 12.4%) and the proportion of women in the law schools rose from 4% in the 1960’s to 8% by 1970, and then to 33% by 1980.”) For a description of the complex interplay of sociological, political and historical factors triggering women’s entrance into the profession see note 119.

126 Id at 17–19.

A 1961 National Opinion Research Center study of college students who chose law as a profession showed that 46% of the students opting for law had fathers with B.A.’s or higher decrees, as opposed to 21% of the students choosing careers other than the law. Mothers of pre-law students also had more education than those of their schoolmates: 21% of the mothers of the pre-law students had B.A.s or higher degrees, compared with 16% of the mothers of their schoolmates. Id. at 17.

127 Id. at 18.

128 Id. (citing Rita Lynne Stafford, An Analysis of Consciously Recalled {Professional Involvement for American Women in New York State (1966) (unpublished PhD thesis, New York University) (on file with the Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, New York University) (“When Stafford asked her sample of eminent women lawyers about fathers’ and mothers’ encouragement of their professional ambitions, 75% said that their mothers had encouraged them, and 65% said their fathers had encouraged them.” Id. at 23).

129 Fuchs Epstein, supra note 68, at 20–21 (“The influence of the mother, not as a model but as a “force,” may have been more important than any other single factor in guiding some of these daughters into law, although it is difficult to say exactly how their influence was manifested.” Id. at 22.)

130 Id. at 25. (2.8% of the graduating women at Barnard College in 1969 went to law school but merely two years later, in 1971, the percentage had increased to 5.8%. In addition, “An article exploring the changing mood toward law school in 1974 observed that one-third of a recent graduating class at Smith applied, and one-half of the Radcliffe class of 1971 actually went on to law school.” Id. (referencing Susan Edmiston, Portia Faces Life: The Trials of Law School, Ms 2, no. 10, 74 (Apr. 1974)).

131 State of Qatar, Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, Education In Qatar, Statistical Profile 2016, 17 (June 2017) https://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/Social/Education/2016/Education_Statistical_Pro%EF%AC%81le_2016_En.pdf, last visited Apr. 1, 2019.

132 Id. at 49.

133 Inglehart, R., C. Haerpfer, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin & B. Puranen et al. (eds.). 2014. World Values Survey: Round Six - Country-Pooled Datafile Version: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp. Madrid: JD Systems Institute.

134 Qatar Education Study (QES) 2012 Parents Survey [dataset]. Doha, Qatar: Social and Economic Survey Research Institute (SESRI, https://sesri.qu.edu.qa/) [distributor]. May 15, 2018 version (data indicates that about 48% of Qatari women who self-identified as university graduates indicated their children used private tutors versus about 36% of Qatari women who self-identified as having completed less education (primary through secondary). Data indicates that about 66% of Qatari men who self-identified as university graduates indicated their children used private tutors versus about 38% of Qatari men who self-identified as having completed less education (primary through secondary)).

135 See also Melissa Deehring, Teaching the Women, Peace and Security Agenda in MENA Law Schools, LEXIS MENA Bus. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2020) [hereinafter Deehring LEXIS] (mentioning the oral history project Voices of Qatari Women in International Law and Diplomacy in which almost all of the women profiled and interviewed mentioned their mothers as strong positive personalities and influencers of their daughters’ education and career.)

136 As example Maryam AlJabor, Head of Juvenile and Family Prosecution, State of Qatar Office of Public Prosecution, Remarks at the Women in Law Conference, Qatar University College of Law, Doha, Qatar (Mar. 22, 2018) (translated into English during live translation at the conference).

137 Gulf Women ix-x (Amira El-Azhary Sonbol ed. 2012).

138 Id. at ix.

139 See Deehring LEXIS, supra note 139 (citing as example Melissa Deehring, Voices of Qatari Women in International Law and Diplomacy Oral History Project, Campus & Student Life in Qatar (@students_qatar) Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/tv/B47g6mBH5D1/?igshid=mxppcwc6e7va (last visited Nov. 29, 2019); Community Connect Doha (@communityconnectdoha) Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/p/B468GywATUj/?igshid=t7ucpuqy4x4q (last visited Nov. 29, 2019)).

140 Gulf Women, supra note 141, at 153–155.

141 See generally Erica Field, Seema Jayachandran, Rohini Pande, and Natalia Rigol, Friendship at Work: Can Peer Effects Catalyze Female Entrepreneurship?, Faculty Research Working Paper Series, Harvard Kennedy School of Government, RWP 15-019, 4 (Apr. 2015).

142 Id. at 20–21.

143 Fuchs Epstein, supra note 68, at 11–16.

144 Deehring LEXIS, supra note 139 (mentioning Qatar’s growing influence in world trade and international investments, peace negotiations, and military alliances and referencing: Saeed Shah et al., ‘Taliban Five,’ Once Held at Guantanamo, Join Insurgency’s Political Office in Qatar, Wall. St. J. (Oct. 30, 2018) https://www.wsj.com/articles/taliban-five-once-held-at-guantanamo-join-insurgencys-political-office-in-qatar-1540890148; Eric Knecht, Qatar Investment Authority aims to reach $45 billion in U.S. investments: CEO, Reuters (Jan. 13, 2019) https://www.reuters.com/article/us-qatar-investments-united-states/qatar-investment-authority-aims-to-reach-45-billion-in-u-s-investments-ceo-idUSKCN1P7090; Qatar’s investment in Germany to reach €35bn in next 5 years, The Peninsula (Qatar) (Oct. 18, 2018) https://www.thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/18/10/2018/Qatar%E2%80%99s-investment-in-Germany-to-reach-%E2%82%AC35bn-in-next-5-years; Mark Brown, Qatar’s Sheikha Mayassa tops art power list, The Guardian (London) (Oct. 24, 2013); The Office of Her Highness Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, UN Secretary-General re-appoints HH Sheikha Moza as UN Sustainable Development Goals’ Advocate, Doha (May 9, 2019) https://www.mozabintnasser.qa/en/news/un-secretary-general-re-appoints-hh-sheikha-moza-un-sustainable-development-goals%E2%80%99-advocate%C2%A0; Qatar Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, Foreign Policy, Preventative Diplomacy page https://www.mofa.gov.qa/en/foreign-policy/preventive-diplomacy (last visited Jul. 28, 2019); #IPU140 Assembly in Doha to focus on education, gender equality and counter-terrorism, Inter-Parliamentary Union Press Release (Apr. 1, 2019) https://www.ipu.org/news/press-releases/2019-04/ipu140-assembly-in-doha-focus-education-gender-equality-and-counter-terrorism; Shereena Qazi, Intra-Afghan talks with Taliban under way in Qatar, AlJazeera (Doha) (Jul. 7, 2019) https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/07/qatar-hosts-intra-afghan-summit-peace-talks-taliban-190706134720995.html; Brad Lendon, Qatar hosts largest US military base in Mideast, CNN (Jun. 6, 2017) https://edition.cnn.com/2017/06/05/middleeast/qatar-us-largest-base-in-mideast/index.html.)

145 Fuchs Epstein, supra note 68, at 77; see also Id. at 63–76 and 209–237.

146 Id. at 78–87.

147 Such as being a judge, particularly a criminal judge, and/or a public prosecutor.

148 Surah An-Nisa 4:34–42 which refers to men being the protectors of women and women’s obedience is the most commonly cited reference for this thinking. https://quran.com/4/34?translations=18,21,22,84,95 (Thank you to my former law student, Maryam Ahmed Al-Maraghi, for helping me research this issue.)

149 Fuchs Epstein, supra note 68, at 86–89.

150 Alreem Al Naimi, Judge Assistant, State of Qatar Supreme Judicial Council, Remarks at the Women in Law Conference, Qatar University College of Law, Doha, Qatar (Mar. 22, 2018).

151 Melissa Deehring, The Push for Practical Skills Education in Qatar: Results from an Externship Program, Int’l Rev. of L., Vol. 2016, Issue 2 (2016) https://www.qscience.com/doi/pdf/10.5339/irl.2016.10.

152 See Eli Wald, A Primer on Diversity, Discrimination, and Equality in the Legal Profession or Who is Responsible For Pursuing Diversity and Why, 24 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 1079, 1079–81 (2011); see also Paul M. George and Susan McGlamery, Women and Legal Scholarship: A Bibliography, Faculty Scholarship Paper 1248, (1991) https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/1248 (last visited Mar. 25, 2018); Sandra Petersson, New Zealand Bibliography of Women and the Law 1970–2000, 32 Victoria U. Wellington L. Rev. [ix] (2001); Jason P. Nance & Paul E. Madsen, An Empirical Analysis of Diversity in the Legal Profession, Conn. L. Rev. Vol 47, No. 2, 217, 279–281 (Dec. 2014) (section II. Literature Review and Theory provides a well-written overview of pro-diversity arguments); see generally ABA Women in the Prof. Resources, Articles, Reports, Research, & Organizations / Initiatives – By Topic, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/women/resources/articles_reports_research_topic.html#diversity) (last visited Mar. 25, 2018); Nat’l Ass’n of Women Lawyers, https://www.nawl.org/ (last visited Mar. 20, 2018); Mary Jane Mossman, The First Women Lawyers: A Comparative Study of Gender, Law and the Legal Professions 54 (2006); Jean McKenzie Leiper, Bar Codes: Women in the Legal Profession (2006).

153 ABA Sec. of Litig. supra note 2, at 5 (This argument is referred to as the ‘Democracy Rationale’).

154 ABA Sec. of Litig. supra note 2, at 5. (This argument is referred to as the ‘Demographic Rationale’).

155 Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 332–3 (2003) (“Individuals with law degrees occupy roughly half the state governorships, more than half the seats in the U.S. Senate, and more than a third of the seats in the U.S. House of Representatives.”), see also Deborah L. Rhode, Lawyers as Leaders, 1 (2013) (“Although they account for just 0.4% of the population, lawyers are well-represented at all levels of [American] leadership, as governors, state legislators, judges, prosecutors, general counsel, law firm managing partners, and heads of corporate, government, and non-profit organization.”); see also ABA Sec. of Litig. supra note 2, at 5 (This argument is referred to as the ‘Leadership Rationale’).

156 ABA Sec. of Litig. supra note 2, at 9 (This is referred to as the ‘Business Rationale’).

157 (The ‘Democracy’ or ‘Demography’ rationales might work better in cultures where work-related social identity is the prevailing culture instead of tribal lineages or in countries where citizens compose the majority of legal residents.)

158 Supra note 141.

159 See Government Communications Office, State of Qatar website, Prime Minister And Minister Of Interior page, available at https://www.gco.gov.qa/en/about-qatar/the-prime-minister/ (showing H.E. Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser bin Khalifa Al Thani, Prime Minister And Minister Of Interior holds a law degree from Beirut Arab U.) (last visited Mar. 19, 2018).

160 See Government Communications Office, State of Qatar, Council Of Ministers, https://www.gco.gov.qa/en/ministries/minister-of-justice/ (last visited Mar. 19, 2018) (H.E. Dr Khalid bin Mohamed Al Attiyah, Deputy Prime Minister And Minister Of State For Defence Affairs; H.E. Dr Hassan Bin Lahdan Saqr Al Mohannadi, Minister Of Justice; H.E. Dr Issa Saad Al Jafali Al Nuaimi, Minister Of Administrative Development, Labour And Social Affairs hold law degrees).

161 See Id. (H.E. Dr Gaith bin Mubarak Al Kuwari, Minister Of Endowments (Awqaf) And Islamic Affairs holds degrees in Sharia).

162 Supra note 142.

163 McKinsey & Company, Women Matter: Time to accelerate: Ten years of insights on gender diversity, 16 (Oct. 2017); see also Credit Suisse Research Inst., The CS Gender 3000: The Reward for Change, 25–27 (Sept. 2016) (Researchers found that by increasing the number of women in top management positions within an organization, companies directly increased their share price. Companies who had at least 33% women in top management paid a dividend 6.8% higher and companies who had more than 50% women in top management, paid an annual dividend 14.8% higher than average.)

164 Fuchs Epstein, supra note 68 at 306.

165 Id.

166 Id. at 307.

167 Id.

168 Alreem Al Naimi, supra note 150.