Abstract

During the reproductive season of the white-tailed deer, 36 diluted semen samples from deer were evaluated before freezing, and at the time of thawing. The samples were obtained by electro ejaculation from three sedated deer with a mixture of Zoletil® and xylazine hydrochloride. Samples were diluted with three commercial extenders Biladyl®, Trilady® and Bioxcell® and frozen by applying two freezing curves, the one used for sheep and goat, and the recommended for deer semen. The response variable was the Semen Quality Index for Deer (SQID%) obtained from the estimation of the percentage of gross motility, progressive motility, alive sperms, normal sperms and sperm concentration. The results of the statistical analysis showed differences (p = 0.0301) between the extenders before freezing, resulting Bioxcell® with greater SQID (60.77%), while for Triladyl® and Biladil® rates were 48.39% and 33.01%, respectively. As for the evaluated freezing curves, no differences were found (p = 0.5502) between the recommended curve for deer semen and the curve used for sheep and goat semen. In the present study, the use of the SQID as response variable turned out to be useful in the assessment of diluents and freezing curves.

1. Introduction

White-tailed deer is one of the wildlife species with greater economic importance in Mexico, by the number of animals that are traded annually for various uses, mainly for hunting. White-tailed deer is tolerant to human activity, and adapts to a wide variety of ecosystems, being one of the game species with wide distribution in Mexico (Galindo-Leal & Weber Citation1998). Species of greatest importance for sport hunting tend to be the same in the American Continent, where the tropical region highlighting countries such as Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela and Peru (Perez & Ojasti Citation1996). For all benefits that white-tailed deer represents as species, studies about biology are essential to carry out their conservation and management.

In Mexico, profitability of land through hunting has motivated diversified farmers to implement new technology to improve deer quality to be used as game trophy. Such is the case of genetic improvement that currently is carried out in the northeastern region in the States of Coahuila, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas, through the introduction of outstanding stallions and application of assisted reproduction techniques such as artificial insemination (Clemente-Sanchez et al. Citation2012).

Sperm conservation plays an important role in the breeding management of wild populations (Holt Citation2000). Given the commercial importance of the white-tailed deer it is essential to study the means to preserve germplasm that may, on one side, contribute to the reproductive success of the species, and on the other side, as a mean to maintain native populations, and as a tool for genetic improvement in the market of game trophies.

Therefore, in this research it was raised to analyze three commercial semen extenders (Biladyl®, Triladyl® and Bioxcell®) of greater use in animal husbandry for freezing semen. Simultaneously, they were assessed two curves of semen freezing, the first recommended for deer semen, and a second that is used for cryopreservation of sheep and goat semen, as an alternative to freeze deer semen.

2. Material and methods

On February, March, October and December, 2013, nine electro ejaculates of three mature deer (3.5 years old) were obtained. Deers were confined in pens separately, and pens were surrounded with deer-mesh 2.30 m height, in a total area of 1800 m2, with shadows, feeders and waterers. Deers were adapted to closure during six months before research, and were fed with a diet consisting of 30% of ground dehydrated alfalfa and 70% of a commercial concentrate for deer with 18% protein, and clean water all the time of the experiment.

There were analyzed a total of 36 semen samples from nine ejaculates at the rate of four samples per ejaculate. Of the 36 samples, 18 were used to know the possible effect of diluents on the Semen Quality Index for Deer (SQID) before freezing, and the remaining 18 were used to know the possible effect of the freezing curves on the SQID at the time of thawing. Treatments were set by the combination of three diluents with two freezing curves (3 × 2 = 6 treatments), where each treatment had three replicates ().

Table 1. Matrix arrangement of treatments and semen samples used to test semen extenders and freezing curves on deer semen.

2.1. Semen collection

Deers were contained chemically by using a mixture of Zoletil® (4.4 mg k−1) and xylazine hydrochloride (2.2 mg k−1) applied intramuscularly by using propelled darts with a CO2 rifle. Once deer was immobilized, it was eyes and ears covered and moved to the laboratory. To expose the deer penis it was followed the procedure described by Drew and Amass (Citation2004). Once the penis glans was exposed, it was hold with a cotton glove and a gauze strip. Next, a lubricated electro-ejaculator was introduced into the rectum towards the internal penis as close as possible. Intervals of four seconds of electric stimulation and three seconds rest were applied till obtain ejaculation. Only six intervals were needed to achieve the ejaculation that was collected in a conical plastic tube graduated 15 ml, previously tempered at 36°C.

Once the semen was collected, deer was moved back to its pen where the antagonist Tolazine® was applied intramuscularly at a dose of 2.0 mg k−1 to reverse the effect of the tranquilizer; simultaneously, the collection tube was placed in a water bath at 35°C and immediately proceeded to dilution for assessment and calculation of the response variables and the SQID values.

2.2. Preparation of extenders

The preparation of each extender was carried out according to the instructions recommended by the manufacturer, and made according to the volume of the ejaculated.

For the dilution of Biladyl® only 0.5 g of the concentrate fraction A and 3.9 mL redistilled water were used to prepare the stock solution, plus 1.0 mL of egg yolk and 0.1 mL (100 µL) of the cocktail AB to make a volume of 5.0 mL of the fraction without glycerin. For the second fraction, it was used 1.0 mL of egg yolk plus 4.0 mL of solution B, consisting of 2.5 mL of the concentrate of fraction B, and 1.5 mL of water redistilled to obtain a total of 5.0 mL of fraction B with glycerin, to make a total of 10.0 mL for diluting the volume of semen obtained, at the rate of one part of semen and five parts of extender.

The Triladyl® extender was prepared using 2.0 mL of the concentrated Triladyl®, 6.0 mL of redistilled water and 2.0 mL of egg yolk to obtain a total of 10.0 mL of diluent to dilute the volume of semen obtained at the rate of one part of semen and five parts of diluent.

To make the solution with Bioxcell® it was used only 2.0 mL of concentrate and 8.0 mL of redistilled water to obtain a total of 10.0 mL that was used for dilute the volume of semen obtained at the rate of one part of semen and five parts of diluent.

In order to know the effect of the extenders, 18 semen samples were evaluated considering the five variables to estimate the SQID for the respective extender.

2.3. Semen evaluation

Evaluation of semen was done for the total of 36 samples to estimate the variables: gross motility (GM), progressive motility (PM), sperm concentration (SC), alive sperms (AS) and normal sperms. Each determination was made following the procedures described by Arenas-Baez (Citation2011). The values of these variables were used to calculate the SQID according to the model built by Clemente-Sanchez et al. (Citation2012).

2.4. Freezing curves

The packaging of 18 semen samples was done at room temperature by using tubes Eppendorf Easypet® 2.0 mL, depositing 0.5 mL of diluted semen, according to the treatment and in a time of 10 minutes after obtaining the ejaculated.

The curve recommended for freezing sheep (Salamon and Maxwell Citation1995) and goat semen (Dorado Citation2003), as well as the curve used for freezing deer semen (Drew & Amass Citation2004) were applied manually. The procedure for applying the sheep and goat curve and once the semen was packaged, tubes were fixed in aluminium sticks and placed inside a crystal container filled with cotton, and exposed for cooling (5°C) for one hour. After this time, sticks with tubes were exposed to nitrogen vapours for a period of 15 minutes on a separate frame 6.0 cm from the level of nitrogen. Then, the sticks were immersed in liquid nitrogen for another 15 minutes, and finally placed in a nitrogen thermo for storage.

To apply the freezing curve recommended for white-tailed deer semen, the tubes also were placed in aluminium sticks and put inside of a glass container with cotton for its cooling at 5°C, but now for three hours. Immediately, sticks were also placed on a frame 6.0 cm separate of the nitrogen level to receive the vapours for a period of 15 minutes. After this time, sticks with tubes were also immersed into the nitrogen for another 15 minutes, and finally moved to the storage thermo.

In order to know the effect of freezing curves, 18 semen samples were thawed for 45 s in a water bath at 36°C. Then, the five variables considered in the model were estimated, and used to calculate the SQID for the respective freezing curve.

2.5. Statistical analyses

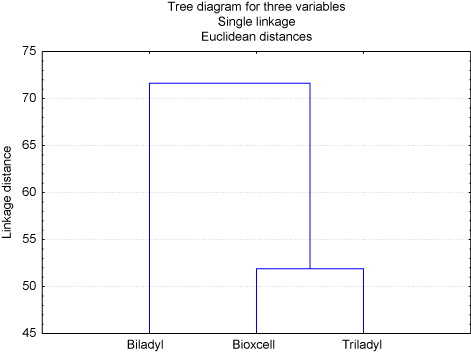

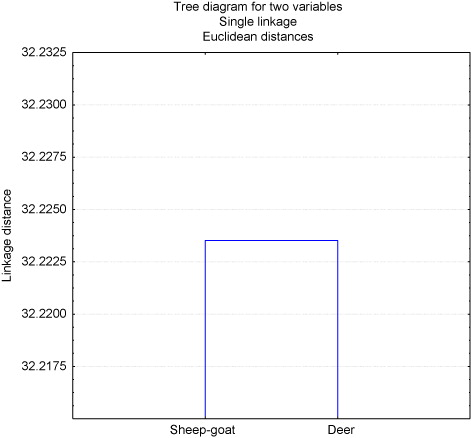

A cluster multivariate analysis was done as exploratory technique to know the trend of extenders, by calculating the Euclidean Index that group extenders for its similarity considering the five variables used to estimate the SQID (Arenas-Baez Citation2011). In the same way, it was made to know the trend of the freezing curves. This analysis was done by using the Statistica programme (v 7.0).

Known trends of diluents and freezing curves, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was made using the GLM procedure on the SQID variable to determine the effect of diluents and curves, before and after freezing, respectively (Arenas-Baez Citation2011). To select the best extender, a Tukey test (p < 0.05) was conducted. The statistical analysis was done using the SAS programme (v 9.1.3).

3. Results and discussion

All samples of pure semen that were subjected to the treatments suffered reduction in its quality index. The SQID of diluted semen before freezing varied in a range of 10.37% to 66.02% with average of 47.38% (±19.12), which indicates that according to the criteria of classification of the model, the diluted semen resulted from bad to good quality. In the same way, the SQID when thawing it returned to decrease in all samples, showing a variation from 7.09% to 59.39%, with average of 33.64% (±19.43), obtaining semen that was from bad to regulate quality, according to the classification criteria of the model ().

Table 2. Estimation of the semen quality index of deer (SQID) before freezing, and at the time of thawing.

During the semen evaluation, the gradual phenomenon of declining in motility, as well as in SC and AS from fresh semen to the time of thawing, showed 30% reduction. These results are consistent with those reported by several researchers (Asher et al. Citation2000; Holt Citation2000; Drew & Amass Citation2004; Mendoza Citation2008) so it should be considered for the cryopreservation of sperm cells to be subsequently used in artificial insemination to make doses that should contain a high number of sperm, that varies between 25 and 100 million of sperms, according to the insemination technique to be used. The semen collection by electro ejaculation has been successfully in deer by using both, fresh and frozen semen, which makes it an efficient technique. However, semen quality obtained in this study contrasts with the results reported by Arenas-Baez (Citation2011), who reported SQID obtained in white-tailed deer in a range from good to excellent.

The semen parameters used routinely are still useful for the evaluation of semen of many species (Drew & Amass Citation2004; Malo et al. Citation2005; Roldan et al. Citation2009; Arenas-Baez Citation2011), so these to be considered in the model developed by Clemente-Sanchez et al. (Citation2012) this model becomes a tool that standardizes its quality value in a rating index. The SQID supports the criterion of Muiño et al. (Citation2005) and Hafez and Hafez (Citation2002) who mentioned that the assessment of gross and PM as parameters of the semen quality are not sufficient to predict the fertilizing capacity of sperm. Since reproductive function in ungulates is mainly influenced by environmental factors, other semen parameters related to management, nutrition and health, may affect the quality and quantity of semen, even more in the case of wild deer, where environmental and nutritional conditions may not be controlled, so the authors recommend the use of the SQID as a tool for the standardization of the process in the assessment of semen.

3.1. Effect of diluents

The result of the exploratory multivariate cluster analysis, showed that the five variables considered to estimate the SQID, at the time of been diluted, showed similarity in the two extenders, but one extender spread considerably (p < 0.05) of the remaining two. Biladyl® is grouped separately from the others and Bioxcell® and Triladyl® show great similarity between them, according to the Euclidean Index estimated ().

This trend was confirmed by the results of the ANOVA where there was difference (p = 0.0301) between Biladyl®, Triladyl® and Bioxcell®. Values of SQID before freezing showed averages of 60.77% for Bioxcell®, while for Triladyl® was 48.39% and for Biladyl® 33.01%. The Tukey test showed no differences (P > 0.05) between Bioxcell® and Triladyl® (60.77% and 48.39%), in the same way, between Biladyl® and Triladyl® (33.01% and 48.39%), but Bioxcell® remains different from Biladyl®, so that Bioxcell® could be suggested as the best extender (60.77%) to be used in the conservation of fresh semen of white-tailed deer ().

Table 3. Effect of semen extender before and after freezing, and effect of freezing curve at the time of thawing on the percentage of semen quality index of deer (SQID).

With respect to the semen diluted with Biladyl® the results agree with Roldan et al. (Citation2009), who obtained the highest percentage of motility after thawing with semen diluted in a base of Test-Tris than with Biladyl®. This effect as mentions Garcia (Citation2002), may be due to reduced time of sperm survival because the toxic effect of high concentrations of glycerol due to Biladyl® is added to the semen into two fractions. There are few references regarding the effect of this diluent, although, as mentioned Salamon and Maxwell (Citation1995), the most widely used cryoprotectant is glycerol and its concentrations have been sufficiently studied. However, the cryoprotectant concentration depends on the diluter and especially the osmotic pressure (Watson Citation2000).

Regarding the use of Triladyl®, Marinez-Pastor et al. (Citation2009) mentioned that this diluent has been used for cryopreservation of wild ruminants’ semen. The present investigation has to Triladyl® as the second best diluent, which coincides with Asher et al. (Citation2000), who reported its use in semen of chital deer collected by electro ejaculation, and also reported by Carballo (Citation2005) on the cryopreservation of bovine semen, where sperm motility after thawing was higher with Triladyl®, probably because the difference in the environmental conditions and the species in which the experiment was conducted.

The use of Bioxcell® in this study was the best extender for fresh deer semen, compared to the other two, which coincides with Gil et al. (Citation2003), who reported that Bioxcell® is an alternative for the conservation of ram semen. Similarly, Sariözkan et al. (Citation2010), demonstrated that the use of Bioxcell® with or without centrifugation and sperm washing, facilitates the conservation of fresh semen in goats. However, in this study the SQID with semen diluted with Bioxcell® declined during the freezing time showing no difference (p = 0.3684) with the other diluents at the time of thawing ().

3.2. Response of the freezing curves

According to the Euclidean Index, the results on the SQID at the time of thawing, showed a similarity of 50% between sheep and goat and deer curves, (). The difference in the procedure between the two curves consisted in variation in cooling time that remains semen at temperature of 5°C, prior to the reduction of temperature up to –196°C. The time applied for the curve of sheep and goat was one hour, while for the curve of deer it was three hours. From these times, the procedure in both curves was the same.

The result of the exploratory analysis on freezing curves was corroborated to estimate the effect of freezing curves where the ANOVA showed no difference (p = 0.5502) in the SQID between the freezing curves recommended for sheep and goats (30.80% ± 20.43%) and the curve recommended for deer (36.50% ± 19.15%). This suggests that deer sperm is a cell that support a quick cooling speed, based on that reported by Holt (Citation2000) who recommends that the optimum cooling rate for sperm cells must be slow enough to avoid a lethal effect to the cell, but fast enough to reduce to a minimum the harmful effects of prolonged exposure to high concentrations of salt.

According to the results obtained in this study, it is advisable that in future researches, the freezing is carried out as recommended by Salamon and Maxwell (Citation2000), in what the shape of the curve should be of a parabola, instead of the decrease of temperature in a linear way, considering that changes in the rate of cooling, temperature intervals, and temperature ranges cause lethal damage to the cell. For this reason, the cooling of semen must be slowly in order to maintain the characteristics of proteins in seminal plasma that interact with the proteins of the sperm nucleus, and that the sensitivity of the sperm to shock by cold is determined by the species, and characteristics of the individual and the ejaculate. (Watson Citation1995; Byrne et al. Citation2000; Yoshida Citation2000; Dorado Citation2003).

Finally, it is advisable to follow up researches with deer semen, testing new alternatives of commercial diluents as the AndroMed®, as well as temperatures and times of thawing, as reported by Dorado (Citation2003), that thawing of semen performs at 39°C during 30 s, while Marinez-Pastor et al. (Citation2009) carried out at 65°C for 6 s on Iberian red deer semen.

4. Conclusion

It is concluded that of the extenders Biladyl®, Triladyl® and Bioxcell® it is recommended to use Bioxcell® for the semen dilution of white-tailed deer, for its use on fresh semen. The use of Bioxcell® is more convenient for deer semen, because it is not made with animal protein ingredients that could reduce the fertility of sperm cells. Both, the curve used in the cryopreservation of semen of sheep and goats and the recommended curve for deer semen, may be used without affecting the rate of the SQID. However, the use of the curve for sheep and goats would be recommended given the less time spent in the freezing procedure. The SQID was a useful tool in the assessment of extenders and studied freezing curves. Because the observed deviation in the estimation of the variables included in this study, it is suitable for future researches, make evaluations by using computer programmes as the Computer Assisted Sperm Analysis (CASA) to reduce the possible experimental error.

Funding

The authors acknowledge to SEP-CONACYT fund for the financial support under the project number 0166903, and to Laboratory of Assisted Reproduction, of the Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus SLP.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arenas-Baez P. 2011. El fotoperiodo y su relación con la reproducción del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus miquihuanensis) en el altiplano potosino [The photoperiod and its relation to the reproduction of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus miquihuanensis) in the Potosino Plateau]. [master's thesis]. Montecillo (Estado de México): Colegio de Postgraduados.

- Asher GW, Berg DK, Evans G. 2000. Storage of semen and artificial insemination in deer. Anim Reprod Sci. 62:195–211. 10.1016/S0378-4320(00)00159-7

- Byrne GP, Lonergan P, Wade M, Duffy P, Donovan A, Hanrahan JP, Boland MP. 2000. Effect of freezing rate of ram spermatozoa on subsequent fertility in vivo and in vitro. Anim Reprod Sci. 62:265–275.

- Carballo GDM. 2005. Comparación de dos diluyentes comerciales para criopreservar semen de bovino bajo condiciones de campo en el trópico húmedo [Comparison of two commercial extenders for cryopreservation of bovine semen under field conditions in the humid tropic]. [bachelor's thesis]. Veracruz: Universidad Veracruzana.

- Clemente-Sanchez F, Arenas-Baez P, Gallegos-Sanchez J, Mendoza-Martinez G, Rosas-Rosas OC. 2012. Índice de calidad de semen fresco de venado cola blanca aplicado a la selección de reproductores [Fresh semen quality index of whitetail deer applied to the selection of breeder males]. In: Memorias del XIII Simposio sobre venados de México. Toluca: UNAM-CEPANAF-UAEM; p. 57–61.

- Dorado JMM. 2003. Respuesta a la congelación-descongelación del esperma de macho cabrío [Response to freeze-thawed of goat sperm] [dissertation]. Córdoba: Universidad de Córdoba.

- Drew M, Amass K. 2004. Semen production and artificial insemination of white-tailed deer. Mt. Horeb (WI): Safe-Capture International, Inc; p. 54.

- Galindo-Leal C, Weber M. 1998. El venado de la Sierra Madre Occidental, Ecología, Manejo y Conservación [The deer in the Sierra Madre Occidental, Ecology, Conservation and Management]. México (DF): Ediciones Culturtales SA de CV-Conabio; p. 272.

- Garcia BD. 2002. Influencia del dilutor, raza y mes en la crioconservación del semen ovino [Influence of the extender and month in the cryopreservation of ram semen]. [master's thesis]. Chapingo: Universidad Autónoma Chapingo.

- Gil J, Rodriguez-Irazoqui M, Lundeheim N, Soderquist L, Rodriguez-Martinez H. 2003. Fertility of ram semen frozen in Bioexcell® and used for cervical artificial nsemination. Theriogenology. 59:1157–1170.

- Hafez ESE, Hafez B. 2002. Reproducción e inseminación artificial en animales [Reproduction and artificial insemination in animals]. Séptima edición. México (DF): McGraw-Hill Interamericana Editores; p. 694.

- Holt WV. 2000. Fundamental aspects of sperm cryobiology: the importance of species and individual differences. Theriogenology. 53:47–58.

- Malo AF, Garde JJ, Soler AJ, García AJ, Gomendio M, Roldan ERS. 2005. Male fertility in natural populations of red deer is determined by sperm velocity and the proportion of normal spermatozoa. Biol Reprod. 72:822–829. 10.1095/biolreprod.104.036368

- Marinez-Pastor F, Martinez F, Alvarez M, Maroto-Morales A, Garcia-Alvarez O, Soler AJ, Garde JJ, De Paz P, Anel L. 2009. Cryopreservation of Iberian red deer (Cervus elaphus hispanicus) spermatozoa obtained by electroejaculation. Theriogenology. 71:628–638.

- Mendoza NP. 2008. Efecto de la metionina protegida en el crecimiento de astas y evaluación del semen de ciervo rojo (Cervus elaphus) en el trópico [Effect of protected methionine on the growing antlers and semen evaluation of red deer (Cervus elaphus) in the tropic]. [dissertation]. Montecillo: Colegio de Postgraduados.

- Muiño R, Fernández M, Areán H, Viana JL, López M, Fernández A, Peña AI. 2005. Nuevas tecnologías aplicadas al procesado y evaluación del semen bovino en centros de inseminación artificial [New technologies for the processing and evaluation of bovine semen in centers of artificial insemination]. Aragón (España): Información Técnica Económica Agraria. 101:175–191.

- Perez EM, Ojasti J. 1996. La utilización de la fauna silvestre en la América Tropical y recomendaciones para su manejo sustentable en las sabanas. Sociedad Venezolana de Ecología [The use of wildlife in tropical America and recommendations for sustainable management in the savannas]. Ecotropicos. 9:71–82.

- Roldan ERS, Ganan N, Gonzalez R, Garde JJ, Martinez F, Vargas A, Gomendio M. 2009. Evaluación de la calidad del semen, crioconservación del esperma y fecundación in vitro en el lince ibérico (Lynx pardinus), una especie gravemente amenazada [Evaluation of semen quality, sperm cryopreservation and in vitro fertilization in the Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus), a highly endangered species.]. Reprod Fertil Dev. 21:848–859. 10.1071/RD08226

- Salamon S, Maxwell WMC. 1995. Frozen storage of ram semen I. Processing, freezing, thawing and fertility after cervical insemination. Anim Reprod Sci. 37:185–249. 10.1016/0378-4320(94)01327-I

- Salamon S, Maxwell WMC. 2000. Storage of ram semen. Anim Reprod Sci. 2:77–111. 10.1016/S0378-4320(00)00155-X

- Sariözkan S, Bucak MN, Tuncer PB, Tasdemir U, Kinet H, Ulutas PA. 2010. Effects of different extenders and centrifugation washing on postthaw microscopic-oxidative stress parameters and fertilizing ability of angora buck sperm. Theriogenology. 73:316–323.

- Watson PF. 1995. Recent developments and concepts in the cryopreservation of spermatozoa and the assessment of their post-thawing function. Reprod Fertil Dev. 7:871–891. 10.1071/RD9950871

- Watson PF. 2000. The causes of reduced fertility with cryopreserved semen. Anim Reprod Sci. 60–61:481–492. 10.1016/S0378-4320(00)00099-3

- Yoshida M. 2000. Conservation of sperms: current status and new trends. Anim Reprod Sci. 60–61:349–355. 10.1016/S0378-4320(00)00125-1