ABSTRACT

Keeping sows in single housing systems with farrowing crates can affect animal health and welfare. The aim of this study was to investigate the behaviour and health of lactating sows kept in a novel group housing system which could be easily installed on commercial farms. The housing system had five farrowing pens without crates, a common area and an area only available for piglets. Data from 25 sows were collected in five batches. Sows’ location and activity, suckling behaviour and floor soiling were analysed by video or direct observation. Skin lesions were determined using a lesion score. Group housing of sows did not increase the number of skin injuries, since the lesion score decreased during the housing period (19.2 vs. 16.3 vs. 12; p < .05). Before the piglets left the pens, sows were mostly inside the pens (83.4%; p < .05) and the highest faecal-soiling was found in the common area. The common area was used intensively by the sows, particularly since the piglets left the pens (4th week: 63.5%). The suckling frequency remained constant (6th week: 1.2/h); cross-suckling occurred rarely (7.6%). Sows were able to perform natural behaviours in the new housing system, potentially increasing animal welfare.

1. Introduction

In most countries it is still common practice to keep sows in single housing systems with farrowing crates, from parturition until the end of lactation. The farrowing crate was originally introduced because it has fewer space requirements and requires less labour to maintain. Moreover, it also reduces piglet crushing by the sow as well as providing a safe means of access for the farmer compared to traditionally used individual loose-housing pens (Edwards and Fraser Citation1997). However, the confinement also restricts the natural behaviour of the sow (EFSA Citation2007) and the social pressure for a general abolition of the farrowing crate is increasing (Baxter et al. Citation2012).

Under semi-natural conditions sows leave their herd one to two days before farrowing and start to search for an appropriate nesting site (Jensen Citation1986; Stolba and Wood-Gush Citation1989). For the first few days following farrowing, the sow and piglets remain in or close to the nest, returning to the herd after approximately 10 days (Jensen Citation1986). Farrowing crates hinder the sow from selecting a nest-site, carrying out normal nest-building behaviour, or leaving the nest for eliminative behaviour (EFSA Citation2007; Špinka Citation2009) which can lead to a higher risk of stereotyped behaviour, e.g. vacuum chewing or bar biting (Arellano et al. Citation1992; Arey and Sancha Citation1996). The farrowing crate itself can also cause a higher incidence of skin lesions (Verhovsek Citation2007).

As a consequence of this, several studies concerning alternative farrowing systems have been carried out (Edwards and Fraser Citation1997; Johnson and Marchant-Forde Citation2009; Baxter et al. Citation2012). These alternative systems can be divided into individual housing systems, group housing systems and combined systems; the latter being systems where the sows are housed individually in early lactation and in groups in later lactation (Johnson and Marchant-Forde Citation2009). Group housing throughout lactation can be divided into two systems: one where the communal area is only available to the sows, and one where the sows and their litters live together in a wider group (van Nieuwamerongen et al. Citation2014). According to van Nieuwamerongen (Citation2014), group housing of sows during lactation is closer to the natural conditions of the sow and so, due to increasing the free space and the possibilities for exploration and social interaction, it may improve the welfare for the sows and piglets. However, difficulties such as aggressive behaviour between the sows were reported for group housing systems, enabled by the possibilities for social interaction (Hultén et al. Citation1995; Weary et al. Citation2002). Hultén et al. (Citation1995) observed that primiparous group housed sows showed more skin lesions than single-housed sows as they fought to establish dominance hierarchies. Hence, providing sufficient space to escape from higher ranking sows may be an important factor for reducing stress (van Nieuwamerongen Citation2014)

When the piglets were not able to follow the sow to the common area the sows spent increasingly less time with their piglets and suckling activity greatly declined (Weary et al. Citation2002), causing early weaning (Bøe Citation1993). Furthermore, disturbances in suckling behaviour, caused by cross-suckling (Braun Citation1995) can also occur as well as an increased rate of piglet mortality due to crushing (Marchant et al. Citation2000, van Nieuwamerongen et al. Citation2014). Due to this and to the required space, the group housing and other alternative systems are still restricted commercially (Baxter et al. Citation2012; van Nieuwamerongen et al. Citation2014). Nevertheless, there is a need for improving the welfare of sows and their piglets in intensive pig production, and thus for developing animal-friendly housing systems which can be used under practical farming conditions.

In the present study, we investigated a novel group housing system for sows during the lactation period which is suitable to be easily installed on commercial farms. Data concerning behaviour and skin injuries were collected for the first time in this housing system which differed from systems investigated in earlier studies. In several studies concerning group housing systems, sows got food by individual troughs either inside the pens (Arey and Sancha Citation1996; Bohnenkamp et al. Citation2013) or in the activity area where water was also available by drinkers (Wülbers-Mindermann Citation1992; Wechsler Citation1996; Weary et al. Citation2002; Kutzer Citation2009; Li et al. Citation2010). In the present study, sows were fed ad libitum by a sow-feeder in a common area to encourage the sows to use this area for active behaviour. To motivate the sow to visit the pen regularly after feeding, water was given inside the pens by drinking bowls. Furthermore, sows were given the possibility of choosing freely between different farrowing pens and the common walking area. Behavioural analyses should reveal whether the sows utilized the additional space, i.e. the common area, and whether they continued to spend time in their own farrowing pen. The detection of skin lesions using a lesion score was used as an indicator for the occurrence of aggressive behaviour between the group-housed sows. Furthermore, suckling behaviour and the occurrence of cross-suckling were analysed.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals and housing

The study was carried out on the research farm of the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Foundation, Germany. On the research farm, a total of 80 sows (genetics: BHZP) were kept, and every two weeks about eight sows gave birth to piglets. For the present study, data from 25 sows with first to ninth parity and their litters were collected in a total of five batches. During gestation, the sows were housed in a dynamic group of about 35 sows (2.42 m2 per animal) with an electronic feeding system and concrete flooring (activity area with slatted; lying areas with solid flooring). Sows were transferred to the farrowing system seven days before the expected day of farrowing.

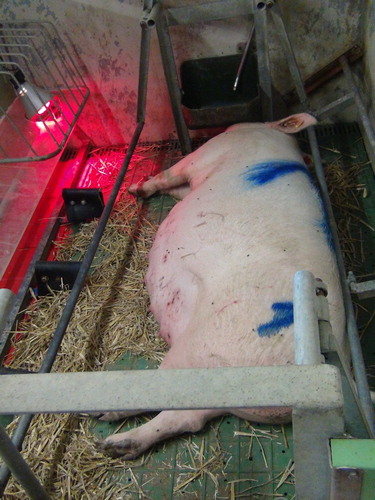

The group housing farrowing system consisted of five single pens for farrowing (2 m × 2.5 m) and a common area (6.1 m × 1.9 m) in the centre ( and ). In addition, an area (0.7 m × 2.5 m) only available for the piglets (piglet area) was located between two farrowing pens. Instead of farrowing crates, the pens were equipped with flexible iron bars and rubber bollards to prevent crushing of piglets by the sow. The sows were able to move freely, they could turn around inside the pens, leave them and meet other sows in the common area. After entering the group housing system, the sows could select the farrowing pens by themselves. At the beginning of birth, the farrowing pens were closed in order to prevent the sows from disturbing by penmates. Pens were reopened within the following 12 hours. Until the end of the lactation period, every sow had access to each farrowing pen since there was no controlling unit at the entrance.

Figure 2. Farrowing pen with low-perforated flooring, flexible iron bars and rubber bollards in front of the piglet nest (Photo: Schrey).

The sows were fed ad libitum with a commercial dry lactation meal by a feeder located in the common area. Water was only available in drinking bowls for sows and piglets in the five pens. Each pen and the piglet area were equipped with a water-heated piglet nest (0.3 m × 2.4 m). A flexible step at the entrance of the pens prevented the piglets from leaving the farrowing pens during the first days of life. Grown up, the piglets could pass the steps and meet other sows and piglets. To ensure that all piglets (including the weaker ones) could leave the pens, apertures in the pens’ board were opened when the first piglets started leaving the pens.

Three farrowing pens (pens 1, 2 and 5) had plastic flooring with a low perforation (0.7%), the other two pens were fitted with plastic slats (29% perforation) with a central lying area to accommodate the sows’ shoulders. In the common area, the floor was equipped with plastic slats (29% perforation). In each pen, straw for nest building was provided to the sows. In the three pens with low perforation, each sow was given about 10-litre loose, long straw per day until the end of lactation. In the other pens, the sows received the same amount of straw until the third day after entering the housing system for nest building. In the common area, no straw was given. In two batches, one sow (first or eighth parity) had to leave the group housing system prematurely at the 8th or 14th day after the sows had entered the system due to difficulties during birth or lactation (agalactia). For behavioural analyses, only batches with five sows were considered.

Within the first 2 days after farrowing, the maximum litter size was balanced at 14 piglets per litter. Piglets received individual ear tags and boars were castrated five days post-partum, on average. Piglets were weaned on average 35 days post-partum.

2.2. Skin lesions

To analyse the occurrence of aggressive interactions, skin lesions (i.e. scratches caused by the teeth of another sow) were documented by one observer when the sows entered the farrowing system, three days later and when the sows left the system. Several parts of the body, i.e. head, ears, shoulder/neck, side, ham, belly, back, vulva and tail were scored by a scoring-system from 0 to 3 (Parratt et al. Citation2006). Score 0 was given for a body part if no scratches were found. Score 1 was assigned if less than 5 superficial scratches were observed, and score 2 was given if five to 10 superficial scratches or less than 5 deep scratches were detected. Score 3 described a body area with more than 10 superficial scratches or more than 5 deep scratches. A cumulative lesion score (min.: 0/max.: 51) was calculated for each sow as the sum of the scores for the different body parts. Additionally, the occurrence of shoulder lesions was recorded for the right and left shoulder of each sow at the beginning and at the end of the study. Only wounds, i.e. bleeding and/or crusted lesions were documented. Superficial lesions with only swelling or reddening of the skin were not considered. Both fresh and healing lesions were documented.

2.3. Behavioural observations

The behaviour of sows and piglets was continuously video recorded during the housing period. Seven cameras (Everfocus EQ550, lens EVF-2810DC, Everfocus, Taiwan), one above each respective pen and two above the common area, were installed and connected with a digital video recorder (Everfocus ECOR264–9 × 1, Everfocus, Taiwan). The sows were marked individually on their backs and thigh muscles with a commercial livestock-marking spray when they were transferred to the group housing system. The marks were renewed once a week. The videos were analysed for three batches with regard to the sows’ activity and location during one day in the first week after the sows had been transferred to the group housing system (i.e. before farrowing), in the second week (i.e. immediately after farrowing) and in the fourth and sixth week (i.e. after the piglets left the pens), respectively. Each day was divided into three observation periods from 06:00 h to 10:00 h, 13:00 h to 17:00 h and 00:00 h to 04:00 h. The posture (lying, sitting, standing or walking) and location of each sow were recorded using time sampling (instantaneous sampling) every 10 minutes. The videos were observed by one trained person.

Suckling behaviour was analysed in three batches once a week, starting when the piglets left the farrowing pens (i.e. from the third until the sixth week after the sows had entered the system). For this purpose, direct recording by one trained person during a period of three hours per day was carried out, listing the location and the time of each suckling. Furthermore, the occurrence of cross-suckling was recorded by analysing the number of own (i.e. appertaining to the sow) and foreign piglets during the suckling periods. For this purpose, each piglet originating from the same litter was marked with the same colour using livestock-marking spray. Piglets received individual ear tags before they could leave the pens, thus enabling individual identification.

The dunging behaviour of the animals in the group housing system was recorded by the observation of floor soiling once a week. Different areas available for the sows (each pen and the common area) were given a score from 0 to 3. Score 0 described a clean area, score 1 was a low grade soiled area. Score 2 was given if a moderate occurrence of faeces could be found. Score 3 was assigned if an area was highly soiled with faeces.

2.4. Statistics

The statistical analysis was performed using the software package IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 23, IBM, New York, USA). The data were tested for normal distribution using frequency distribution vertical-bar graphs and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov-test. Since data were normally distributed, univariate analysis of variance was carried out followed by post hoc tests (Student–Newman–Keuls) according to the following models:

Cumulative lesion score:

where y is the = cumulative lesion score; µ is overall mean; batchi is effect of batch of experiment (i = batch 1–5); timeij is effect of time of observation within batch (j = 1–3); eij is random residual error.

Floor soiling:

where y is the floor soiling score in the pens or in the common area; µ is overall mean; batchi is effect of batch of experiment (i = batch 1–5); timeij is effect of week within batch (j = 1–6); eij is random residual error.

For behavioural data, frequency distributions and cross tables were created. To detect significant differences between frequencies or percentages for behavioural data, Chi-Square tests were conducted. The following behavioural variables were analysed:

Percentage of sows’ location in different weeks (statistical unit: group; data averaged for day/week)

Percentage of sows’ location in the morning/afternoon/night (statistical unit: group; data averaged for four hours per time of day)

Percentage of sows’ activity during the housing period in different pen areas (statistical unit: group, data averaged for day/week and for all weeks)

Percentage of sows’ activities in the course of housing period (statistical unit: group, data averaged for day/week)

3. Results

3.1. Skin lesions

The mean cumulative lesion score of sows declined significantly with the increasing housing period ().

Figure 3. Means and standard deviations of the cumulative lesion score for the sows in the group housing system (n = 25 sows). Significant differences are indicated by different letters (p < .05).

Considering all sows, shoulder lesions were not observed at the left and in 8.7% at the right shoulder when the sows entered the group housing system. At the end of lactation, shoulder lesions occurred in 4.3% of the sows at the left and in 8.7% at the right shoulder. Hence, during the housing period, shoulder lesions increased by a mean of 2.2% in total (left shoulder 4.3%; right shoulder 0%).

3.2. Behavioural observations

During the entire observation period, the sows were observed more often in the pens compared to the common area (54.4% vs. 45.6% of all observations, p < .05). The piglets started leaving the pens 10.6 days post-partum, on average (min.: 7 days; max.: 14 days).

During the second week after entering the housing system, i.e. the time between parturition and the moment when the piglets could leave the pens, sows spent significantly less time in the common area compared to the pens (16.6% in the common area vs. 83.4% in the pens, p < .05). During this week, the sows were observed either in the common area or in their ‘own pen’ (82.9%) where the litter was housed (). Visiting another pen than their own occurred very rarely (0.4%). During the fourth and sixth week, all sows spent time in different pens, abandoning their previous pens and the common area was used more frequently. Sows spent significantly more time in the common area compared to the pens during the fourth week (p < .05). During the sixth week, the sows were observed roughly with the same frequency in the common area and in the pens (p > .05).

Table 1. Sows’ location related to all observations (%) in different weeks.

Sows spent more time in the common area during the day from 06:00 h to 10:00 h and from 13:00 h to 17:00 h compared to night-time from 00:00 h to 04:00 h (34.2% and 35.2% vs. 30.6%, p < .05). The pens with low-perforated flooring (pens 1, 2 and 5) were used more frequently compared to the other pens (65.4% vs. 34.6%, p < .05).

Inside the pens as well as in the common area the most frequent activity of the sows was lying (90.2% in the pens and 71.6% in the common area). However, standing and walking were found more frequently in the common area compared to the pens (26.8% vs. 8.4%; p < .05). Sitting did not differ between both locations (). In the course of the housing period, the frequency of lying was approximately constant, apart from a slight increase during the second week after entering the housing system. Sitting was consistently rarely observed ().

Figure 4. Percentage of sows’ activities in the course of housing period relating to total number of observations.

Table 2. Sows’ activity during the housing period (number of observations (n) and percentage (%)).

3.3. Floor soiling

During the entire housing period the common area was more soiled compared to the pens (mean score: 1.43 vs. 0.91; p < .05). For the common area the highest faecal-soiling (p < .05) was found in the second week (). Accordingly, the pens showed the lowest soiling during this time. From the second to the third week the soiling of the common area decreased, with the result that floor soiling was approximately balanced between pens and the common area until the end of lactation.

3.4. Suckling behaviour

The suckling frequency did not change during the lactation period of 35 days (1.3 sucklings per hour in the third week vs. 1.2 sucklings per hour in the sixth week). With regard to the suckling location, the sows nursed the piglets roughly with the same frequency in the common area and in the pens (49.3% vs. 50.7%; p > .05). Concerning the occurrence of cross-suckling, on average 0.8 foreign piglets and 9.3 own piglets were observed per sow during the suckling periods. The mean percentage of cross-suckling piglets relating to all suckling piglets was 7.6%. During the course of lactation, this number remained almost constant (8.3% in the third week and 7.2 in the sixth week). In 48.9% of cases of cross-suckling the piglet suckled at the same foreign sow during the entire lactation period. This phenomenon differed between the batches (53.3% in batch 1, 22.2% in batch 2 and 71.8% in batch 3), thus individual differences between the piglets’ cross-suckling strategies seem to exist.

4. Discussion

4.1. Skin lesions

In the present study, sows showed a decrease in skin lesions from the time when entering the group housing system until the end of the housing period. During pregnancy, the sows were all kept in a dynamic group, where aggressive interactions can occur causing skin injuries. The decrease in the lesion score during the farrowing and lactation period indicated that sows did not carry out injurious aggressive behaviour towards each other in the group housing system. Arey and Sancha (Citation1996) observed a low occurrence of aggression between group housed sows during lactation as well. However, Weary et al. (Citation2002) described aggressive behaviour during the first 24 hours after the sows were allowed to mix. In contrast to Weary et al. (Citation2002), sows in the present study as well as in the study of Arey and Sancha (Citation1996) already became acquainted with each other during pregnancy, which could explain the differences in the occurrence of aggressive behaviour. When unacquainted sows meet for the first time, an increase in skin lesions could be expected as most aggressive interactions occur during the first two to three days after mixing in order to establish a social hierarchy (Biswas et al. Citation1995; Arey Citation1999). However, familiar sows showed less aggressive behaviour after mixing, due to the ability to recognize each other although they were separated for six weeks (Arey Citation1999). Furthermore, the occurrence of agonistic behaviour can be influenced by parity and weight distribution within a group (Verdon et al. Citation2015) and the social rank is positively correlated with the parity and weight of the sow (Arey Citation1999). Strawford et al. (Citation2008) found that older sows (fourth parity or higher) showed more aggressive behaviour than primiparous sows. Verdon et al. (Citation2015) concluded that primiparous sows should have the possibility of avoiding older sows or should be housed together with sows of roughly the same age. In the present study, the age of the sows varied from the first to the ninth parity. Thus, an influence of the sows’ age on aggressive behaviour seems possible. Nevertheless, this effect was not observed, probably due to the acquaintance of sows before grouping and the opportunity for primiparous sows to escape from older dominant sows. Furthermore, when primiparous sows were used for group housing it was ensured that the group consisted of at least two gilts and they were grouped with second parity sows only.

The investigated group housing system had to be integrated into an existing part of an old building, leading to compromises concerning the dimensions of the common area. Thus, higher levels of aggressive behaviour could be expected due to fewer opportunities for lower-ranking sows to avoid dominant sows or due to a limited access to the feeder. However, our results showed that the occurrence of aggressive behaviour was low and no problems caused by dominant sows (e. g. blocking the access to the feeder) were observed. Furthermore, there were also possibilities for sows to retreat from their pen mates since the farrowing pens were always accessible. Though, since other circumstances (e.g. groups containing gilts and old sows) may lead to such problems and considering that the common area was used intensively by the sows for different behaviours (resting and active behaviour, defaecating) an amplified width of the common area (at least 2.4 m) might offer even more advantages to the sows.

The incidence of shoulder lesions in the group housing system was relatively low in comparison to results of previous studies investigating the occurrence of shoulder lesions in farrowing crates. Thus, Bonde et al. (Citation2004), studying health problems of lactating sows in commercial Danish sow herds, observed that shoulder wounds occurred in 12% of the sows in farrowing crates (ranging from 3% to 25%). Schmidt et al. (Citation2014), who investigated the occurrence of shoulder lesions in German sow herds, found that 6–22% of the sows housed in conventional pens with farrowing crates showed severe (i.e. bleeding or crusted) shoulder lesions during lactation, confirming that shoulder lesions are a common problem in conventional single housing systems for sows. We decided to consider only bleeding and/or crusting lesions since these were clearly to define and have a higher impact on animal welfare. Schmidt et al. (Citation2014), investigating the occurrence of shoulder lesions in farrowing crates used a lesion score from 0 to 4. The author distinguished lesions which are relevant for animal welfare (lesions with crusting and bleeding wounds; score 3 and 4) from those which are not yet relevant for animal welfare (hairless lesions and swelling without scab; score 1 and 2). However, it might not be excluded that the early stages are not painful at all. According to Herskin et al. (Citation2011), there is a lack of knowledge concerning the relation between pain and decubital shoulder ulcers. The authors assumed that the development and presence of shoulder ulcers are painful.

According to Rolandsdotter et al. (Citation2009), risk factors for the occurrence of shoulder lesions are long uninterrupted lying periods. Cleveland-Nielsen et al. (Citation2004) described a lower risk of shoulder lesions for loosely housed sows due to spending more time standing and moving around compared to confined sows. In the present study sows could use a common area. We found that the sows obviously used this area for active behaviour (i.e. standing, walking and feeding), thus probably reducing the total lying period compared to confined sows. Furthermore, the texture of flooring, especially fully slatted floor and wet or soiled floor, can increase the risk of shoulder lesions (Bonde et al. Citation2004). Except for these risk factors concerning the housing system, the body condition of the sows, as well as the sow’s parity and the weaning weight of the piglets can influence the occurrence of shoulder lesions (Zurbrigg Citation2006).

4.2. Behavioural observations

During the second week after entering the group housing system, sows obviously spent most of the time in the farrowing pens. During this time, between parturition and the moment when the piglets could leave the pens, the sows left the pens purely for feeding and dunging. According to the present results, sows under semi-natural conditions spent most of the time in the nest and were observed there in 90% of the observations two days post-partum. With increasing age of the piglets, the sows could be observed more frequently outside the nest-site (Jensen Citation1986; Stangel and Jensen Citation1991). Furthermore, we found that during the second week the sows were almost exclusively in their ‘own pen’ (82.9%), where the litter was housed. Visiting another pen than their own pen occurred very rarely (0.4%). Our findings indicate that the sows precisely recognize and recover their own litter after spending time in the common area for feeding and dunging. Likewise, Horrell and Hodgson (Citation1992) as well as Maletínská et al. (Citation2002) recorded that sows could identify their own litter already in an early post-partum period (first 24 h) largely by odours. During the later lactation period, the recognition was based on acoustic and optical cues as well (Illmann et al. Citation2002, Mayer et al. Citation2006). The sows spent most of the time in their own farrowing pens, together with the litter, although they could use the common area during the second week. In contrast, Weary et al. (Citation2002) who enabled the sows to use a get-away area, described an increasing use of this area, starting in the early lactation (from 2 h on day 6 to more than 14 h on day 27) and a decrease in suckling behaviour. In contrast to our study, only the sows could use this area while piglets had access to a separate piglet area. In our study the sows could only escape from the piglets during the second week of the housing period when the piglets were not able to leave the pens. Sows might have a higher need for maternal affection during this early post-partum period and thus hardly left their farrowing pens. Later on, piglets could follow the sows into the common area where suckling was also performed.

We observed that the piglets left the pens at the age of 10.6 days, on average, and met unfamiliar sows and piglets from other litters. Thereafter, all sows spent time in different pens, abandoning their previous pens and the common area was used more frequently. Similarly, sows under semi-natural conditions abandoned the nest and returned to the flock about 10 days after farrowing (Jensen Citation1986, Jensen and Redbo Citation1987). Thus, the sows were allowed to carry out their natural behaviour in the group housing system.

Bohnenkamp et al. (Citation2013), who investigated sows in a similar group housing system, also observed that sows preferred the farrowing crate until the piglets could leave the pens and thereafter the sows spent increasing time in the running area. However, those pens were equipped with farrowing crates and an electronical sow identification system at the entrance, thus each sow had only access to a personal farrowing crate. The time when the piglets could leave the pens and meet other piglets was fixed on the fifth day after parturition, due to removing a flexible step at the entrance. In contrast, in the present study the sows and piglets were kept without regulation from outside, thus enabling them to decide freely how to move within the housing system.

Concerning the different farrowing pens, sows preferred the pens with low-perforated flooring as those were used more frequently compared to the other pens. After farrowing, straw was provided exclusively inside the pens with low-perforated flooring until the end of lactation. Hence, the daily provision of straw could have influenced the presence of the sows although the provided amount of straw was not high. Furthermore, the flooring type itself could have influenced the presence of the sows. The low-perforated floor might be more comfortable for the sows during lying and posture changes. Phillips et al. (Citation1996) investigated the preferences of sows concerning different types of flooring (solid concrete, plastic-coated and metal-slatted floor) offered as free choice in farrowing crates. The sows preferred concrete flooring, especially during farrowing. The author observed that the pre-exposure to certain flooring types before testing influenced the later choosing behaviour of the sows. Thus, sows previously housed on concrete floor, preferred the same flooring type after farrowing. With increasing time, sows showed gradually more acceptance of the unfamiliar flooring types (plastic and metal). In the present study, sows had lying areas of solid concrete floor during pregnancy, thus an influence on the behaviour, i.e. on the preference of the low-perforated floor might be possible, although the materials differed (concrete vs. plastic). According to Ducreux et al. (Citation2002), the preference for different flooring types is also influenced by the ambient temperature. The authors offered litter, concrete and slatted floor to growing pigs (70 kg) at low (18°C) and high (27°C) temperature. Pigs housed at low temperature preferred litter; whereas pigs housed at high temperature chose concrete or slatted floor. In the novel group housing system, the pens were in the same room and large variation of the ambient temperature was not found. Beside the flooring texture, the presence of the sows in the pens might also be influenced by the different locations of the pens within the housing system, for instance the proximity to the feeding system. Pen 1 and 5, which were preferred by the sows, were close to the sow feeder.

As standing and walking occurred more frequently in the common area compared to the pens, the sows obviously used the common area for active behaviour, which was also encouraged by the location of the feeder in the common area. All in all, the most observed behaviour was lying (81.8%). Standing and walking were found in 16.8% and sitting in 1.5% of all observations. Götz (Citation1991) studied behavioural activities of sows in farrowing crates during lactation and in comparison to our results a higher occurrence of lying (92.1% and 85%), less standing (7.3% and 11.9%) and more sitting (0.7% and 3.1%) was found for the first and fourth week of nursing, respectively. Lambertz et al. (Citation2015), who compared conventional farrowing crates to loose-housing pens where the crates were opened, found similar results (86–93% lying, 9–10% standing and 1–3% sitting) without any differences between the housing systems. Likewise, Chidgey et al. (Citation2016) observed 88% lying, 9% standing and 4.6% sitting at the sixth day after farrowing for sows housed in crates. The higher proportion of activity that we found in group housing of sows indicates that the motion behaviour of the animals is promoted by the availability of a common area.

4.3. Floor soiling

During the second week, the time between the parturition and the moment when the piglets could leave the pens, the highest faecal-soiling for the common area (p < .05) and the lowest for the pens was found. This result is in accordance with Van Putten (Citation1978) who reported that sows leave the nest for defaecating and urinating. From the third week, the soiling of the common area decreased and the soiling of the pens increased. This is probably related to the changing presence of the sows as the sows were observed more frequently in the common area since the piglets could leave the pens. According to Špinka (Citation2009), pigs use specific dunging areas and they avoid lying in soiled areas. In the present study, the sows used the common area to separate functional areas for feeding, resting and defaecating. Since the piglets could leave the pens, the sows spent more time resting in the common area and the area for defaecating was reduced. The sows started to use certain pens as a defaecating area, which were not used for resting anymore. Likewise, Verhovsek (Citation2007) noted an increase in soiling in the lying area, as well as a change in resting behaviour of sows in single loose-housing pens. This was obviously related to the time when the piglets left the nest and changed the place for defaecating. In the present study, we observed floor soiling in general and did not differ between sows and piglets. However, it was observed that piglets and sows chose the same places for defaecating. After the piglets left the pens both, sows and piglets were defaecating in certain pens and in the common area.

4.4. Suckling behaviour

The suckling frequency remained nearly constant during the observation period (1.3 sucklings per hour in the third week vs. 1.2 sucklings per hour in the sixth week). Jensen (Citation1986) also observed a regular frequency of suckling throughout lactation for sows kept under semi-natural conditions, with 1.3 sucklings per hour on average. Weaning under semi-natural conditions occurred at the age of 14–17 weeks post-partum (Jensen Citation1986; Jensen Citation1988; Petersen Citation1994). Similar to the present results, Šilerová et al. (Citation2006) noticed that the maternal nursing investment did not decline substantially during the fourth and sixth week after birth. In contrast, Weary et al. (Citation2002), as well as Pedersen et al. (Citation1998) noticed a significant decrease in the suckling frequency during the first four weeks post-partum. In both studies, the systems were equipped with a get-away area for the sows, where the piglets could not follow the sow, and with a piglet area.

Concerning the location of suckling, no clear preference was found from the third to the sixth week (49.3% in the common area vs. 50.7% in the pens). In contrast, during the first days of life before the piglets could leave the pens, the sows preferred their own pen for suckling. The common area as suckling location could offer disadvantages due to disturbances of sucklings by foreign piglets. In the present study, a negative influence on the suckling behaviour due to cross-suckling piglets was not found. The occurrence of cross-suckling was 7.6%, on average remaining constant until the end of lactation. In contrast, Maletıínská and Špinka (Citation2001) found that 29% of the suckling piglets were cross-sucklers in a group housing system, observing that the litter size mainly influenced the occurrence of cross-suckling. Wülbers-Mindermann (Citation1992) observed 5–28% cross-suckling, depending on the group size (from five to 11 sows). Hence, the author found that a group size of five sows showed the lowest incidence of cross-suckling, which may explain the low occurrence of cross-suckling in the present study. Further findings in the present study were that in about half of the cases of cross-suckling, the piglets suckled at the same foreign sow for the rest of the lactation period while in the other cases of cross-suckling the piglets changed between different sows. This occurrence of varying cross-suckling types is in accordance with previous studies (Wülbers-Mindermann Citation1992; Braun Citation1995; Brodmann and Wechsler Citation1995; Maletıínská and Špinka Citation2001).

5. Conclusions

In the novel group housing system the sows were allowed to carry out natural behaviour patterns and piglets became acquainted with unfamiliar sows and piglets at the same age as observed under semi-natural conditions. The common area was used intensively by the sows, particularly with increasing age of the piglets. The occurrence of shoulder lesions and skin injuries was low as was the percentage of cross-suckling. The frequency of suckling was not affected by group housing. We, therefore, conclude that, with regard to the examined parameters, the group housing system investigated in this study offers the possibility of increasing the welfare of sows under practical farming conditions.

Acknowledgements

The study was part of the dissertation programme ‘Animal Welfare in Intensive Livestock Production Systems’. We are grateful to Gerd Dahlke for planning the conception of the investigated group housing system. Thanks also go to the staff of the research farm for their assistance during the study and to Nina Volkmann for her support with statistics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arellano P, Pijoan C, Jacobson L, Algers B. 1992. Stereotyped behaviour, social interactions and suckling pattern of pigs housed in groups or in single crates. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 35:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(92)90006-W

- Arey DS. 1999. Time course for the formation and disruption of social organisation in group-housed sows. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 62:199–207. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(98)00224-X

- Arey DS, Sancha ES. 1996. Behaviour and productivity of sows and piglets in a family system and in farrowing crates. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 50:135–145. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(96)01075-1

- Baxter E, Lawrence A, Edwards S. 2012. Alternative farrowing accommodation: welfare and economic aspects of existing farrowing and lactation systems for pigs. Animal. 6:96–117. doi: 10.1017/S1751731111001224

- Biswas C, Pan S, Ray S. 1995. Agonistic ethogram of freshly regrouped weaned piglets. Indian J Anim Prod Manage. 11:186–188.

- Bøe K. 1993. Maternal behaviour of lactating sows in a loose housing system. Appl Anim Behav Sci 35:327–338. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(93)90084-3

- Bohnenkamp AL, Meyer C, Müller K, Krieter J. 2013. Group housing with electronically controlled crates for lactating sows. Effect on farrowing, suckling and activity behavior of sows and piglets. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 145:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2013.01.015

- Bonde M, Rousing T, Badsberg JH, Sørensen JT. 2004. Associations between lying-down behaviour problems and body condition, limb disorders and skin lesions of lactating sows housed in farrowing crates in commercial sow herds. Livest Prod Sci. 87:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.livprodsci.2003.08.005

- Braun S. 1995. Individual variation in behaviour and growth of piglets in a combined system of individual and loose housing in sows [master’s thesis]. Skara: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine.

- Brodmann N, Wechsler B. 1995. Strategien von fremdsaugenden Ferkeln bei der Gruppenhaltung ferkelführender Sauen [Strategies of cross-suckling piglets in a group housing system for lactating sows]. KTBL Schrift. 370:237–246.

- Chidgey KL, Morel PC, Stafford KJ, Barugh IW. 2016. Observations of sows and piglets housed in farrowing pens with temporary crating or farrowing crates on a commercial farm. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 176:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2016.01.004

- Cleveland-Nielsen A, Bækbo P, Ersbøll A. 2004. Herd-related risk factors for decubital ulcers present at post-mortem meat-inspection of Danish sows. Prev Vet Med. 64:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2004.05.004

- Ducreux E, Aloui B, Robin P, Dourmad J, Courboulay V, Meunier-Salaün M. 2002. Ambient temperature influences the choice made by pigs for certain types of floor. Journées de la Recherche Porcine. 34:211–216.

- Edwards S, Fraser D. 1997. Housing systems for farrowing and lactation. Pig J. 39:77–89.

- EFSA. 2007. Animal health and welfare aspects of different housing and husbandry systems for adult breeding boars, pregnant, farrowing sows and unweaned piglets. The EFSA J. 572:1–13.

- Götz M. 1991. Changes in nursing and suckling behaviour of sows and their piglets in farrowing crates. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 31:271–275. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(91)90012-M

- Herskin MS, Bonde M, Jørgensen E, Jensen KH. 2011. Decubital shoulder ulcers in sows: a review of classification, pain and welfare consequences. Animal. 5:757–766. doi: 10.1017/S175173111000203X

- Horrell I, Hodgson J. 1992. The bases of sow-piglet identification. 1. The identification by sows of their own piglets and the presence of intruders. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 33:319–327. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(05)80069-3

- Hultén F, Lundeheim N, Dalin A, Einarsson S. 1995. A field study on group housing of lactating sows with special reference to sow health at weaning. Acta Vet Scand. 36:201–212.

- Illmann G, Schrader L, Špinka M, Šustr P. 2002. Acoustical mother-offspring recognition in pigs (Sus scrofa domestica). Behaviour. 139:487–505. doi: 10.1163/15685390260135970

- Jensen P. 1986. Observations on the maternal behaviour of free-ranging domestic pigs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 16:131–142. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(86)90105-X

- Jensen P. 1988. Maternal behaviour and mother – young interactions during lactation in free-ranging domestic pigs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 20:297–308. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(88)90054-8

- Jensen P, Redbo I. 1987. Behaviour during nest leaving in free-ranging domestic pigs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 18:355–362. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(87)90229-2

- Johnson AK, Marchant-Forde JN. 2009. The welfare of pigs: welfare of pigs in the farrowing environment. Dordrecht: Springer; p. 141–188.

- Kutzer TM. 2009. Untersuchungen zum Einfluss einer frühzeitigen Kontaktmöglichkeit zwischen Ferkelwürfen auf Sozialverhalten, Gesundheit und Leistung [dissertation]. Justus-Liebig-University Giessen.

- Lambertz C, Petig M, Elkmann A, Gauly M. 2015. Confinement of sows for different periods during lactation: effects on behaviour and lesions of sows and performance of piglets. Animal. 9:1373–1378. doi: 10.1017/S1751731115000889

- Li Y, Johnston L, Hilbrands A. 2010. Pre-weaning mortality of piglets in a bedded group-farrowing system. Journal of Swine Health and Production. 18:75–80.

- Maletínská J, Špinka M. 2001. Cross-suckling and nursing synchronisation in group housed lactating sows. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 75:17–32. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(01)00178-2

- Maletínská J, Špinka M, Víchová J, Stěhulová I. 2002. Individual recognition of piglets by sows in the early post-partum period. Behaviour. 139:975–991. doi: 10.1163/156853902320387927

- Marchant J, Rudd A, Mendl M, Broom D, Meredith M, Corning S, Simmins P. 2000. Alternative and conventional farrowing systems. Vet Rec. 147:209–214. doi: 10.1136/vr.147.8.209

- Mayer C, Hillmann E, Schrader L. 2006. Verhalten, Haltung, Bewertung von Haltungssystemen. Brade W, Flachowsky G, editors. Schweinezucht und Schweinefleischerzeugung - Empfehlungen für die Praxis, Landbauforschung Völkenrode, Sonderheft. 296:94–121.

- Parratt CA, Chapman KJ, Turner C, Jones PH, Mendl MT, Miller BG. 2006. The fighting behaviour of piglets mixed before and after weaning in the presence or absence of a sow. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 101:54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2006.01.009

- Pedersen LJ, Studnitz M, Jensen KH, Giersing A. 1998. Suckling behaviour of piglets in relation to accessibility to the sow and the presence of foreign litters. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 58:267–279. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(97)00149-4

- Petersen V. 1994. The development of feeding and investigatory behaviour in free-ranging domestic pigs during their first 18 weeks of life. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 42:87–98. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(94)90149-X

- Phillips P, Fraser D, Thompson B. 1996. Sow preference for types of flooring in farrowing crates. Can J Anim Sci. 76:485–489. doi: 10.4141/cjas96-074

- Rolandsdotter E, Westin R, Algers B. 2009. Maximum lying bout duration affects the occurrence of shoulder lesions in sows. Acta Vet Scand. 51:44. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-51-44

- Schmidt N, Schäffer D, von Borell E. 2014. Erfassung von Schulterläsionen bei Zuchtsauen - Vergleich von Abferkelbuchten. Proceedings of the Conference of the German Society for Animal Production e. V. (DGFZ); Sep 17–18; Rostock.

- Šilerová J, Špinka M, Šárová R, Slámová K, Algers B. 2006. A note on differences in nursing behaviour on pig farms employing individual and group housing of lactating sows. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 101:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2006.01.002

- Špinka M. 2009. The ethology of domestic animals: an introductory text: behaviour of pigs. CAB International: Wallingford. p. 177–191.

- Stangel G, Jensen P. 1991. Behaviour of semi-naturally kept sows and piglets (except suckling) during 10 days postpartum. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 31:211–227. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(91)90006-J

- Stolba A, Wood-Gush D. 1989. The behaviour of pigs in a semi-natural environment. Anim Prod. 48:419–425. doi: 10.1017/S0003356100040411

- Strawford M, Li Y, Gonyou H. 2008. The effect of management strategies and parity on the behaviour and physiology of gestating sows housed in an electronic sow feeding system. Can J Anim Sci. 88:559–567. doi: 10.4141/CJAS07114

- van Nieuwamerongen S, Bolhuis J, van der Peet-Schwering C, Soede N. 2014. A review of sow and piglet behaviour and performance in group housing systems for lactating sows. Animal. 8:448–460. doi: 10.1017/S1751731113002280

- van Putten G. 1978. Nutztierethologie: Schwein [Farm Animal Behaviour: Pig]. Berlin-Hamburg: Sambraus Verlag Paul Parey.

- Verdon M, Hansen CF, Rault J-L, Jongman E, Hansen LU, Plush K, Hemsworth P. 2015. Effects of group housing on sow welfare: a review. J Anim Sci. 93:1999–2017. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-8742

- Verhovsek D. 2007. Haltungsbedingte Schäden, Verhalten und biologische Leistung von Sauen in drei Typen von Abferkelbuchten [dissertation]. University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna.

- Weary DM, Pajor EA, Bonenfant M, Fraser D, Kramer DL. 2002. Alternative housing for sows and litters part 4. Effects of sow-controlled housing combined with a communal piglet area on pre-and post-weaning behaviour and performance. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 76:279–290. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(02)00011-4

- Wechsler B. 1996. Rearing pigs in species-specific family groups. Anim Welfare. 5:25–35.

- Wülbers-Mindermann M. 1992. Characteristics of cross-suckling piglets reared in a group housing system [Specialarbete]. Skara: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine.

- Zurbrigg K. 2006. Sow shoulder lesions: risk factors and treatment effects on an Ontario farm. J Anim Sci. 84:2509–2514. doi: 10.2527/jas.2005-713