ABSTRACT

The aim of the survey was to determine the prevalence of all types of lesions associated with contact dermatitis in commercial broiler chickens using pathomorphological methods. Contact dermatitis in commercial broiler chickens was monitored for a period of one year. The samples were taken from a fattening Ross 308 hybrid farm. The annual production cycle was 696,000 birds. The investigations were performed by clinical examination of chickens which showed obvious signs of contact dermatitis on their carcasses in the slaughterhouse. The number and type of contact dermatitis lesions in the different flocks were determined through a meat inspection process. In addition to the gross examination, a histological study on a predetermined proportion of tissue samples was conducted. The total number of contact dermatitis lesions was 152,215 (21.87%). The occurrence was most prevalent during the winter-spring and autumn seasons – 88,932 (12.77%), as opposed to 63,283 (9.1%) during the summer period. Lesions on the plantar skin surface of the foot were predominant – 109,272 (15.7%). This was followed by contact dermatitis lesions on the breast, affecting the sternal bursa – 36,888 (5.3%). The contact dermatitis lesions in the tarsometatarsal joint region were the least prevalent – 6,055 (0.87%).

1. Introduction

The aetiology of contact dermatitis is unclear. The condition is usually encountered in commercial broiler flocks and turkeys (Martland Citation1984; Allain et al. Citation2013). It was initially observed and described by McFerran et al. (Citation1983); later, clinical and pathological findings were presented by Greene (Greene et al. Citation1985). The high prevalence of contact dermatitis among broiler chickens is associated with poor welfare and economic conditions. Losses are mainly attributed to slaughterhouse contamination of carcasses with contact dermatitis lesions (Pattison Citation1987). An examination of losses recorded between 1984 and 1987 revealed an average tarsometatarsal contact dermatitis prevalence of 21%; in some flocks, this reached 90% (McIlroy et al. Citation1987; Bruce et al. Citation1990). Furthermore, skin lesions are considered to be the main point of entry for pathogenic microorganisms, which can cause complications and new lesions of different types – cellulites, gangrenous dermatitis, osteomyelitis (Dinev, Citation2009; Crespo and Shivaprasad, Citation2013; Gornatti-Churria et al, Citation2017).

Epidemiological surveys linked the increased prevalence of the condition to various production aspects, including increased population density, slaughter at a higher age and bigger male to female ratio in the flock (Bruce et al. Citation1990). The appearance of contact dermatitis lesions has also been linked to bad litter conditions, particularly when it occurred suddenly or within a short period of time (McIlroy et al. Citation1987; Bruce et al. Citation1990; Kaukonen et al. Citation2017). Lesions similar to those observed in broiler chickens were encountered in turkeys, housed on wet litter (Martland Citation1984). Recently, an examination of the pain caused by foot pad dermatitis, in the context of turkey poults, noted that the condition may have an adverse effect on mobility and linked it to weight loss (Da Costa et al. Citation2014; Wyneken et al. Citation2015). High humidity in poultry facilities was also highlighted as a predisposing factor (Bruce et al. Citation1990).

From an epidemiological perspective, the factors related to the incidence of contact dermatitis in broiler chickens in the 1980s and the 1990s were analysed and compared using data from large-scale field surveys (McIlroy et al. Citation1987; Menzies et al. Citation1998). In a number of studies, contact dermatitis lesions on the breast and tarsometatarsal joint area were suggested as economically relevant (Greene et al. Citation1985).

The purpose of the present study was to determine the prevalence and severity of contact dermatitis lesions in commercial broiler chicken flocks using pathomorphological research methods.

2. Material and methods

The cases of contact dermatitis in commercial broiler chickens were recorded over a period of one year. Chickens originated from one Ross 308 poultry farm located in Bulgaria. The annual production rate was 696,000 broilers. The observations focused on 36 broiler flocks; 24 flocks consisting of 20,000 chickens (during the winter-spring and autumn seasons), and 12 flocks consisting of 18,000 broilers (during the summer). Gender was not taken into account. The mean stocking density was 18.87/1 m2 and 17.00/1 m2 respectively, depending on the season, and the poultry house area was 1,060 m2. During the experimental period, chickens received different rations depending on the fattening stage. The company’s aim was to produce broilers with an average live weight of 2.1–2.2 kg. The same immunoprophylaxis programme was used for broilers and original breeder flocks. The state of the litter, the relative air humidity and the age at which contact dermatitis lesions appeared were all recorded. Straw was used as litter in all cases.

The investigations were performed by a clinical examination (monitoring and registration) of chickens which showed obvious signs of contact dermatitis on their carcasses in the slaughterhouse. The number and the type of contact dermatitis lesions in the different flocks were both determined through meat inspection. All birds were slaughtered at the age of 36–42 days. The gender of chickens with clinical lesions was not recorded. In addition to the number of affected chickens, the localization and content of contact dermatitis was registered. An evaluation system focusing on the lesions’ area and depth after gross examination, similar to the model proposed by Michel et al. (Citation2012), was used.

For the pathological study, 3 samples from the respective lesion type were obtained from each flock where they were observed. For this purpose, pieces of skin and subcutaneous tissue, including parts of the damaged and adjacent intact area, 1–2 cm in diameter, were fixed in 10% neutral formalin, routinely processed and embedded in paraffin. The cuts, approximately 5 µm, were stained with haematoxylin/eosin (H/E).

During the meat inspection of each flock with skin lesions, the results from routine bacteriological examinations for enterobacteriae and Gram-positive cocci were taken into consideration, as required by the relevant meat inspection hygienic standards. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica Citation6.Citation1 (software). The significance level was set at P < 0.01.

3. Results

Varying levels of severity of the different types of contact dermatitis lesions were recorded in all broiler flocks in the farm during the study. The distribution of skin lesions, including their frequency and localization, is listed in . The total number of contact dermatitis lesions was 152,215 (21.87%), with seasonal prevalence during the winter-spring and autumn seasons: 88,932 (12.77%); this can be contrasted with the summer period: 63,283 (9.1%).

Table 1. Localization and prevalence of lesions specific for contact dermatitis, P < 0.01.

Lesions on the plantar skin surface of the foot (plantar pododermatitis; PPD) were most frequently encountered – 109,272 (15.7%). The appearance of PPD was usually associated with a rapid or sudden dampening of the litter. Wet litter was found: when the ambient humidity on the premises exceeded 70% (in 8 facilities) as a result of the reduction of ventilation rates in order to save fuel for heating purposes (in 8 facilities); after flooding due to a watering system failure (1 premise); and after using a high-protein content ration (>22%) in the grower stage (6 premises). The incidence of lesions in different flocks ranged from 1% to 31%. In 78,648 (11.3%) of the cases, PPD was detected during the winter-spring and autumn. In 30,624 (4.4%) cases it was recorded during the summer of the one-year experimental period. PPD-specific lesions were detected clinically in broilers aged 21–30 days, regardless of the season.

Clinically, after an inspection of the affected chickens, lesions were noticed after the onset of lameness, impaired locomotion or after periods of lying down. The lesions’ surface was covered with brown-black crusts, which were removed along with profuse faecal mass stuck to them. The extent of the lesions varied from small erosions covered with a brown scab to deep ulcerations affecting the subcutis and underlying tissues. Frequently, erosions and ulcers were surrounded by perifocal inflammatory swelling (). In more advanced stages, macerated lesions were detected, and birds were dehydrated due to prolonged periods of lying down and the inability to eat or drink ().

Figure 1. Moderate to strong swelling affecting the metatarsal region due to perifocal inflammatory oedema in plantar pododermatitis.

Figure 2. Plantar pododermatitis lesions, having undergone maceration. Marked dehydration emerging on tarsometatarsal aspects of legs (arrows) likely to prolonged lying down and inability to reach food and water.

PPD lesions, detected in the slaughterhouse after the removal of litter and faecal mass tightly stuck to the foot pads, had a diameter of 1–1.5 cm. The depth of the ulcers varied between 1–2 and 5–6 mm; this was determined through transverse cuts. The lesions were distinctly separated from the intact tissue. Most frequently, they appeared as crater-like grooves surrounded by an indented haemorrhagic area ().

Figure 3. Plantar pododermatitis lesion exposed after removal of faecal mass and litter stuck on it. Well-demarcated crater-like ulcers surrounded by sharply demarcated haemorrhagic zone.

Breast contact dermatitis lesions affecting the sternal bursa were next in prevalence – 36,888 (5.3%). Most of them – 30,624 (4.4%) – were observed during the summer, and the incidence during the other seasons was five times lower (6,264 or 0.9%). In all instances, the earliest appearance of lesions was in chickens older than 36 days of age in the slaughterhouse, when approximately 50% of the flocks with an average live weight > 2 kg were slaughtered.

Breast skin lesions were of various shapes and sizes. In some cases, they were virtually round, 2–3–5–6 cm in diameter, whereas in other cases – strip-like and oblong, 3–4–7–8 cm in length (). It should be noted that the breast plumage of these birds was in a poor condition or absent. The skin was covered with litter and faecal mass stuck to it. In cases of ulcerations, serous or haemorrhagic subcutaneous oedema was usually seen after the removal of the skin. Superficial breast muscles were affected only in the most severe cases.

Figure 4. Breast, skin lesion of an erosive necrotic type in a 38-day broiler chicken after processing at the slaughterhouse.

The lowest prevalence of contact dermatitis lesions was observed on tarsometatarsal joints – 6,055 (0.87%). During the winter-spring and the autumn period, their frequency was almost twice higher than their frequency in the summer period: 4,020 (0.57%) vs 2,035 (0.3%). Lesions of this type could be observed in the farm, but in our study they were detected in the slaughterhouse. The lesions in initial stages were outlined on a hyperaemic surface, sometimes bleeding or eroded, with an area of 2–3 cm2, and in their major part, in dorsal tarsometatarsal joint areas. In more advanced stages, the affected skin was necrotic, with dirty grey colour ().

Figure 5. Contact dermatitis in the region of tarsometatarsal joints. Affected skin is necrotic, and of dirty grey colour.

The extent to which contact dermatitis lesions are observed, as well as the area covered, is presented in . Superficial lesions (erosions) were predominant for all lesion types. Depending on the affected area, plantar lesions were mostly under 1 cm2 (81.3%), whereas those larger than 1 cm2 were most prevalent among breast (84.8%) and tarsometatarsal (75.15%) lesions.

Table 2. aExtent and area of observed contact dermatitis lesions, P < 0.01.

During meat inspection in the slaughterhouse, 420 (≈9%) out of the 4,685 chickens with deep breast lesions were regarded as inappropriate for human consumption and 1,670 (35.6%) were declared fit for processing after the removal of affected areas.

The routine bacteriological examinations which were performed, as per hygienic standards, did not show any differences between intact chickens and those with contact dermatitis lesions.

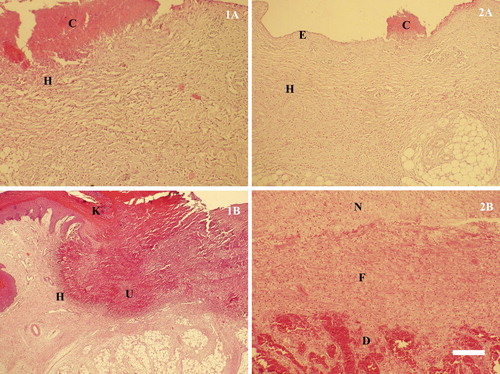

Histologically, the studied samples showed alterations depending on the stage of skin lesions development. In the early stage, subepidermal heterophilic infiltration was usually seen. For erosions, in addition to the inflammatory cell infiltration, typical degenerative necrobiotic changes of the superficial epidermal layers were observed. Deep ulcerations were characterized with the simultaneous occurrence of inflammatory degenerative and necrobiotic changes which affected all epidermal layers and penetrated deep into the dermis. In general, degenerative ulceration was differentiated from the adjacent intact tissue via a heterophilic zone ().

Figure 6. Histological structure of lesions in different stages of contact dermatitis. (1) Plantar lesions: 1A – a superficial lesion manifesting itself in an erosive skin defect, covered by crustose detritus (C) and heterophilic infiltration (H) in the underlying layers; 1B – a deep ulcerative lesion exhibiting defective keratinization in Str. intermedium (K), especially around the ulcer (U) and heterophilic infiltration (H) of the adjacent epidermis. (2) Breast lesions: 2A – an erosive lesion (E) affecting the epidermal layer, remainders of crustose detritus on the surface and heterophilic infiltration (H) in the underlying layers (C); 2B – advanced stage of organizing a lesion defect manifesting itself in the growth of fibrous tissue (F), from the destructive surface (D), which replaces the deposited necrotic detritus (N), H/E, Bar = 30 µm.

4. Discussion

The results of this one-year study on contact dermatitis in broiler chickens originating from one fattening farm, including both clinical surveys and slaughter meat inspection, showed a more moderate prevalence of the condition (21.87%), compared to other recent studies (Haslam et al. Citation2007; Allain et al. Citation2009). From a comparative perspective, PPD was the most prevalent (15.7%), which is very similar to the data (11%) reported by Haslam et al. (Citation2007) but is far lower than the numbers provided by Ekstrand et al. (Citation1997) and Allain et al. (Citation2009) – 38% and 90%, respectively. The variations of PPD occurrence among the flocks in our study (from 1% to 31%) were approximately twice lower than the data reported by Haslam et al. (Citation2007) – from 0 to 71.5%. The fact that PPD was the most frequent lesion could be attributed to the quality of the litter, and therefore the contact between the plantar skin surface and the litter. Among the common risk factors, we are inclined to add fast-growing broiler flocks, the age at which they are slaughtered, etc. (de Jong et al. Citation2012; Bassler et al. Citation2013; Tullo et al. Citation2017). With regards to the findings of Greene et al. (Citation1985), namely that breast and tarsometatarsal lesions were of economic significance, we believe that PPD, leading to a worsened welfare of the flock, is also related to a loss of produce for poultry farmers. We can confirm that the usage of a histologically-validated footpad dermatitis scoring system to examine samples taken from processing plants is suitable for evaluating the severity of lesions in broiler flocks (Pagazaurtundua & Warriss Citation2006; Michel et al. Citation2012).

The prevalence of the other observed types of contact dermatitis lesions affecting the tarsometatarsal joint skin (0.87%) was comparable to that reported by Haslam et al. (Citation2007) – 1.3% but it was much less frequent than the values obtained in the field – 59%, similar to Allain et al. (Citation2009), and those obtained in experimental studies (88% – Kjaer et al. Citation2006; 80.5% – Kristensen et al. Citation2006). The substantial difference could be attributed to environmental conditions, especially in relation to experiments.

The observed breast injuries are referred to as skin lesions, and not separately as breast blisters and breast burns (Allain et al. Citation2009). The prevalence of this lesion type in the present study (5.3%) is almost equal to the data reported by Allain et al. (Citation2009) – 5.2%, but higher (0.02%; Haslam et al. Citation2007) or significantly lower (49.3%; Greene et al. Citation1985) than other research studies.

The seasonal prevalence of contact dermatitis types in our results was dependent on the air humidity and the population density of poultry houses. During the more humid seasons (winter-spring and autumn), PPD (11.3%) and tarsometatarsal joint skin dermatitis (0.57%) were more commonly observed than the summer (4.4% and 0.3% respectively). A seasonal pattern of PPD incidence was also reported in a survey conducted in the UK, where the autumn prevalence (18.1%) was almost twice higher than the summer one (10.2%) (Pagazaurtundua & Warriss Citation2006). This relationship was attributed to the effect of higher air humidity on the quality of the litter, as also supported by studies in Northern Ireland claiming that 83% of the outbreaks occurred during the winter (McIlroy et al. Citation1987). Surprisingly, Haslam et al. (Citation2007) did not establish a seasonal effect on the incidence of contact dermatitis lesions in the tarsometatarsal joint region. At the same time, the same research team found a seasonal effect in some years but not in others (Menzies et al. Citation1998).

In our study, besides in more humid seasons, PPD and tarsometatarsal skin lesions were generally observed in cases of inadequate ventilation; diets with higher protein content; and a case of watering system failure in one of the poultry houses. All these circumstances resulted in lower litter quality. Faeces from the wet litter tend to easily stick to the plantar foot surface and it is highly probable that they pose a high risk of contact dermatitis development due to the erosive effects of faeces and the increased ammonia concentrations (Jensen et al. Citation1970; Martland Citation1985; Ekstrand et al. Citation1997; Bessei Citation2006; Mayne et al. Citation2006). We could not comment on the litter type as a factor which promotes the development of contact dermatitis, as only straw was used in our study. However, there is evidence that the condition was less prevalent when birds were reared on wood shavings (Sirri et al. Citation2007).

The higher prevalence of the third type of skin lesions, localized in the breast region, was recorded during the summer, and among chickens heavier than 2 kg, when the total mass per square metre exceeded 35.00 kg. With respect to population density, our data are comparable to those of Dawkins et al. (Citation2004), Ekstrand et al. (Citation1997), Haslam et al. (Citation2006), Martrenchar et al. (Citation2002), but the seasonal expression was different. It is acknowledged that the higher population density of birds impedes the locomotion and forces birds to lie down. As a result, the continuous contact with the litter predisposes them to dermatitis, affecting the skin of the breast region (Shanawany Citation1992). The appearance of breast skin lesions during the summer in our study was also associated with the prolonged period of extremely high ambient temperatures, when the thermal comfort of the birds was disturbed. The hot weather also results in certain factors responsible for dermatitis appearance, such as high air temperature and overheating of the litter in the building.

The results of the performed bacteriological tests allowed us to confirm that the microbial factor had no major role in the etiogenesis of contact dermatitis; rather, it had a complicating effect. The relevance of gender cannot be discussed as the chickens originated from mixed flocks (almost an equal number of male and female birds). Therefore, gender was not taken into account as a factor in our analysis on lesion occurrence.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the results allowed us to conclude that the prevailing type of contact dermatitis in broiler chickens was plantar pododermatitis, which, together with skin lesions in the tarsometatarsal joint region, was highly dependent on the poor state of the litter (increased humidity). Lesions on the breast skin were the least prevalent and mainly associated with population density in the building, particularly in the finisher stage of broiler chicken production.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks to the owners and practicing vets of the Apetit Ltd poultry farm and Evrovarhat poultry slaughterhouse – Stara Zagora, for kindly providing us with data and access for performing the present research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Allain V , Huonnica D , Rouinaa M , Michel V. 2013. Prevalence of skin lesions in turkeys at slaughter. Br Poult Sci. 54:33–41. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2013.764397

- Allain V , Mirabito L , Arnould C , Colas M , Le Bouquin S , Lupo C , Michel V. 2009. Skin lesions in broiler chickens measured at the slaughterhouse: relationships between lesions and between their prevalence and rearing factors. Br Poult Sci. 50:407–417. doi: 10.1080/00071660903110901

- Bassler AW , Arnould C , Butterworth A , Colin L , De Jong IC , Ferrante V , Ferrari P , Haslam S , Wemelsfelder F , Blokhuis HJ. 2013. Potential risk factors associated with contact dermatitis, lameness, negative emotional state, and fear of humans in broiler chicken flocks. Poult Sci. 92:2811–2826. DOI:10.3382/ps.2013-03208.

- Bessei W. 2006. Welfare of broilers: a review. Worlds Poult Sci J. 62:455–466. doi: 10.1079/WPS2005108

- Bruce DW , McIlroy SG , Goodall EA. 1990. Epidemiology of a contact dermatitis of broilers. Avian Pathol. 19:523–537. doi: 10.1080/03079459008418705

- Crespo R , Shivaprasad HL. 2013. Developmental, metabolic, and other noninfectious disorders. In: Swayne DE , Glisson JR , McDougald LR , Nolan LK , Suarez DL , Venugopal N , editors. Diseases of poultry. 13th ed. Ames (IA ): Wiley-Blackwell; p. 1257–1258.

- Da Costa MJ , Grimes JL , Oviedo-Rondón EO , Barasch I , Evans C , Dalmagro M , Nixon J. 2014. Footpad dermatitis severity on Turkey flocks and correlations with locomotion, litter conditions and body weight at market age. J Appl Poult Res. 23:268–279. doi: 10.3382/japr.2013-00848

- Dawkins MS , Donnely CA , Jones TA. 2004. Chicken welfare is influenced more by housing conditions than by stocking density. Nat. 427:342–344. doi: 10.1038/nature02226

- de Jong IC , van Harn J , Gunnink HV , Hindle A , Lourens A. 2012. Footpad dermatitis in Dutch broiler flocks: prevalence and factors of influence. Poult Sci. 91:1569–1574. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02156

- Dinev I. 2009. Clinical and morphological investigations on the prevalence of lameness associated with femoral head necrosis in broilers. Br Poult Sci. 50:284–290. doi: 10.1080/00071660902942783

- Ekstrand C , Algers B , Svedberg J. 1997. Rearing conditions and foot-pad dermatitis in Swedish broiler chickens. Prev Vet Med. 31:167–174. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(96)01145-2

- Gornatti-Churria CD , Crispo M , Shivaprasad HL , Uzal FA. 2017. Gangrenous dermatitis in chickens and turkeys. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2:188–196.

- Greene JA , McCracken RM , Evans RT. 1985. A contact dermatitis of broilers - clinical and pathological findings. Avian Pathol. 14:23–38. doi: 10.1080/03079458508436205

- Haslam SM , Brown SN , Wilkins LJ , Kestin SC , Warriss PD , Nicol CJ. 2006. Preliminary study to examine the utility of using foot burn or hock burn to assess aspects of housing conditions for broiler chicken. Br Poult Sci. 47:13–18. doi: 10.1080/00071660500475046

- Haslam SM , Knowles TG , Brown SN , Wilkins LJ , Kestin SC , Warriss PD , Nicol CJ. 2007. Factors affecting the prevalence of foot pad dermatitis, hock burn and breast burn in broiler chicken. Br Poult Sci. 48:264–275. doi: 10.1080/00071660701371341

- Jensen LS , Martinson R , Shumaier GA. 1970. A foot pad dermatitis in Turkey poults associated with soybean meal. Poult Sci. 49:76–82. doi: 10.3382/ps.0490076

- Kaukonen E , Norring M , Valros A. 2017. Evaluating the effects of bedding materials and elevated platforms on contact dermatitis and plumage cleanliness of commercial broilers and on litter condition in broiler houses. Brit Poultry Sci. 58:480–489. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2017.1340588

- Kjaer JB , Su G , Nielsen BL , Sorensen P. 2006. Foot pad dermatitis and hock burn in broiler chickens and degree of inheritance. Poult Sci. 85:1342–1348. doi: 10.1093/ps/85.8.1342

- Kristensen HH , Perry GC , Prescott NB , Ladewig J , Ersboll AK , Wathes CM. 2006. Leg health and performance of broiler chickens reared in different light environments. Br Poult Sci. 47:257–263. doi: 10.1080/00071660600753557

- Martland MF. 1984. Wet litter as a cause of plantar pododermatitis, leading to foot ulceration and lameness in fattening turkeys. Avian Pathol. 13:241–252. doi: 10.1080/03079458408418528

- Martland MF. 1985. Ulcerative dermatitis dm broiler chickens: the effects of wet litter. Avian Pathol. 14:353–364. doi: 10.1080/03079458508436237

- Martrenchar A , Boilletot E , Huonnic D , Pol F. 2002. Risk factors for foot-pad dermatitis in chicken and Turkey broilers in France. Prev Vet Med. 52:213–226. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(01)00259-8

- Mayne RK , Hocking PM , Else RW. 2006. Foot pad dermatitis develops at an early age in commercial turkeys. Br Poult Sci. 47:36–42. doi: 10.1080/00071660500475392

- McFerran JB , McNulty MS , McCracken RM , Greene JA. 1983. Enteritis and associated problems. Proceedings of the International Union of Immunological Societies; Disease Prevention and Control in Poultry Production; University of Sydney; Australia.

- McIlroy SG , Goodall EA , McMurray CH. 1987. A contact dermatitis of broilers - epidemiological findings. Avian Pathol. 16:93–105. doi: 10.1080/03079458708436355

- Menzies FD , Goodall EA , McConaghy DA , Alcorn MJ. 1998. An update on the epidemiology of contact dermatitis in commercial broilers. Avian Pathol. 27:174–180. doi: 10.1080/03079459808419320

- Michel V , Prampart E , Mirabito L , Allain V , Arnould C , Huonnic D , Le Bouquin S , Albaric O. 2012. Histologically-validated footpad dermatitis scoring system for use in chicken processing plants. Br Poult Sci. 53:275–281. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2012.695336

- Pagazaurtundua A , Warriss PD. 2006. Measurements of footpad dermatitis in broiler chickens at processing plants. Vet Rec. 158:679–682. doi: 10.1136/vr.158.20.679

- Pattison M. 1987. Problems of diarrhoea and wet litter in meat poultry. In: Harsign W , Cole DJA , editors. Recent advances in animal nutrition. London : Butterworths; p. 27–37.

- Shanawany MM. 1992. Influence of litter water-holding capacity on broiler weight and carcass quality. Arch Geflügelkd. 56:177–179.

- Sirri F , Minelli G , Folegatti E , Lolli S , Meluzzi A. 2007. Foot dermatitis and productive traits in broiler chickens kept with different stocking densities, litter types and light regimen. Ital J Anim Sci. 6(Suppl. 1):734–736. doi: 10.4081/ijas.2007.1s.734

- Statistica 6.1 . https://statistica.software.informer.com/6.1/ .

- Tullo E , Fontana I , Peña Fernandez A , Vranken E , Norton T , Berckmans D , Guarino M. 2017. Association between environmental predisposing risk factors and leg disorders in broiler chickens. J Anim Sci. 95:1512–1520.

- Wyneken CW , Sinclair A , Veldkamp T , Vinco LJ , Hocking PM. 2015. Footpad dermatitis and pain assessment in Turkey poults using analgesia and objective gait analysis. Br Poult Sci. 5:522–530.