?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

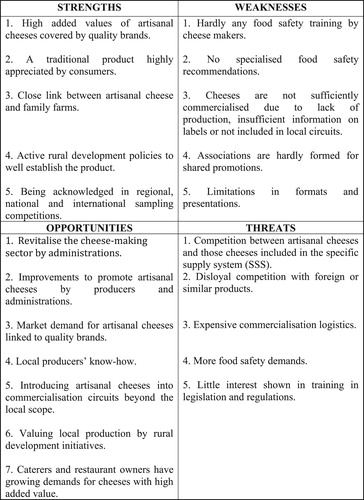

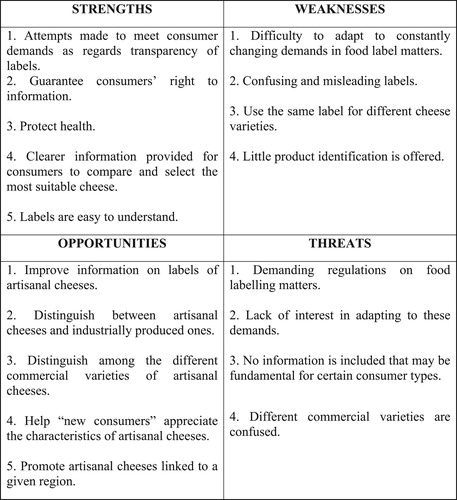

Correct food labelling is primordial for consumers to receive truthful information and help them with their purchasing decisions. This renders the need to adapt each label to fulfil the demands of the new regulations in force. Artisanal cheese with no Designation of Origin has traditionally presented defects that affect its commercialization from incomplete or misleading information on labels. As the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats analysis in this sector has revealed the need to update labelling to adapt to legal changes, this study evidences non-compliances to be corrected and proposes correct generic design labels for several commercialized cheese types with no Protected Designation of Origin on the European market. The information on 76 artisanal cheese labels from several types with neither Designation of Origin nor containers, produced by different cheese makers in Gran Canaria Island (Spain), was analyzed. Most deficiencies that didn’t meet current legislation involved: origin (100%); quantity of ingredients (89.5%); conservation (86.84%); denomination (79%); ingredients (67.10%); marked identification (61.8%); marked dates (58%); milk processing (27%); batch (20%); net quantity (16%). A label model is proposed that covers and meets everything legally set out, favours competitiveness in making artisanal products, and allows their controlled commercialization throughout the European Union.

I. Introduction

Food labelling must provide consumers with clear information about products on sale. Hence according to current legislation, any kind of incomplete, incorrect or misleading label must be avoided. (EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011).

Food crises, growing and stricter customer demands and new consumer habits have brought about changes in food labelling regulations that amend previously proposed label models. Moreover, it has been evidenced that product labels clearly impact purchasing decisions (Hartmann et al. Citation2018).

Nowadays, legislation on general labelling requirements is ample and applies to all foods, while particular regulations exist for specific foods. (Royal Decree 1334/1999 of 31 July)

Legislation in Europe that affects the compulsory information to be shown on food labels is controlled by EC Regulation No. 853/2004 (European Comunities Citation2004), which sets out specific hygiene requirements for foods of animal origin, and by EU Regulation No. 1169/2011 on the provision of food information to consumers.

Spanish State legislation includes Royal Decree 1334/1999, by means of which general regulations on the labelling, presentation and advertising of food products were passed and repealed, except for Articles 12 (about lots) and 18 (about the language labels must be written in).

It is known that one of the characteristics that most influences consumers is the region where the foods they select come from (Trabelsi Trigui and Giraud Citation2012). Hence for products with no Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) in particular, it is understood that any provided information must adapt as much as possible to what is legally expected.

As regards artisanal cheeses with no PDO, other Royal Decrees (RD) can be cited, such as RD 1113/2006, by means of which quality regulations for cheeses and processed cheeses were passed, and RD 818/2015, by means of which Annexes I and II were modified.

Cheese is an important product due to its major global consumption (17 kg per person/year in the EU). Given the long-standing tradition of this livestock activity on the Gran Canaria Island (Canary Islands, Spain) and throughout the Canaries in general (GOBCAN, 2015), with the highest cheese intake per inhabitant and production figures in Spain (11.02 versus 7.66 kg person/year), according to the 2017 Food Intake Report in Spain (MAPA Citation2018), this region was taken as the study area to conduct this study. It can be extrapolated to any other label for artisanal cheeses with no PDO prepared in line with current legislation.

The whole Gran Canaria (GC) region has about 400 cheese-making health records. It is estimated that some 12,250 t of cheese is made, of which 52.4% correspond to raw-milk cheese (Ruiz-Morales et al. Citation2016). Of these, the GC Island has about 80 cheese-making businesses from animals of autochthonous breeds, and with no PDO. This high production varies according to cheese types; it depends on maturity times (semi-hard and/or hard), the milk type employed (pure or mixed) and coverings (oil, paprika or roasted ground corn known as gofio). Approximately 34% are produced as hard cheeses and 46% are semi-hard (AIDER GC Citation2018).

Given this long-standing cheese-making tradition on the Canaries, Decree 50/Citation1995, of 24 March, was passed to control this production. This Decree defines Cheese with the Traditional Characteristics of the Canary Islands, produced on premises with limited production, like those made on the Canaries following traditional methods and using raw milk obtained on farms themselves, which are left to harden for less than 60 days.

To be considered as such, Cheese with Traditional Characteristics must also fulfil EU Regulation No. 853/2004, European Council, of 29 April 2004, Annexe III, Section IX, on requirements related to brucellosis and tuberculosis in Chapter I.I.2. This makes the Canaries a region, the first Spanish Autonomous Community (SAC) ‘officially unharmed’ by caprine, ovine and bovine brucellosis, and by bovine tuberculosis, as declared by the EU. (The Regional Canaries Government of Agriculture, Livestock, Fishing and Waters, 2017).

Cheese-making businesses have maintained their artisanal character and, thanks to the improvements and adaptations made according to the technical health-related regulations, they have accomplished acknowledged cheeses. Indeed from 2009 to the present-day in the ‘World Cheese Awards’, a relevant showroom followed by press that specialises in world gastronomy (ICCA Citation2009), cheeses from the Canaries obtained 15 medals for the GC Island of the 35 medals awarded in this SAC in 2018 (Inter-Insular Council of GC Citation2018)

SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) is a management tool that helps strategic planning processes by providing necessary information for performing actions and taking corrective measures (Muñiz and González Citation2010). It allows work to be done with all information, has many applications and can be used in different analysis units (Martínez Pedros and Milla Gutiérrez Citation2012). It allows results to be concluded that can be communicated to non-specialised publics without much difficulty. It is based on an internal analysis (detecting the strengths or weaknesses that imply competitive advantages or disadvantages) and an external analysis (to identify and analyse threats and opportunities) (Donet Sepúlveda and Juárez Varón Citation2015).

SWOT has been used by different institutions and organizations, such as the Inter-Insular Council of GC, the Insular Association of Rural Development of Gran Canaria (AIDER GC, 2007) and the Regional Canaries Government, to analyse the artisanal cheese sector. However, the SWOT analysis has not been used to conduct a study into artisanal cheese labelling to date.

Having considered the relevance and interest in improving and obtaining correct labels, avoiding deficient or mistaken information for artisanal cheeses with no PDO, the aim of this work has been to propose, by means of SWOT analysis and complying with current legislation, the adequate information to be evidenced in labels designs that suitably informs consumers about the different artisanal cheese types. This label model obtained from cheeses produced on the GC Island as a reference, will cover legal requirements, it´ll promote competitiveness and it´ll allow to control the marketing for any European cheeses with the same production characteristics.

II. Materials and methods

II. 1. Material

II.1.1. Artisanal cheese labels

To conduct this study, 52 cheese-making businesses were visited from 17 towns on the GC Island. From these businesses, 76 labels were directly collected from whole artisanal cheeses with neither PDO nor sold in containers. The intention was to represent the produced varieties (maturity) of the cheeses made with raw milk from the animals owned by cheese makers, which were hard or semi-hard cheeses, from the GC Island with no PDO and are currently commercialized. These labels also included those from those cheese-making businesses with commercially acknowledged production. The collected labels covered different cheese maturity times and milk’s origins (see ). No cheese surface covering or processing was considered because this information was not included on the labels.

Table 1. Distribution of the labels collected for this study.

II.1.2. Labelling legislation

In order to conduct a study about the labels removed from artisanal cheeses with neither PDO nor sold in containers, the Community Provisions were used and directly apply from EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council, dated 25 October 2011, EU Regulation No. 853/2004, European Council, dated 29 April 2004, along with National Provisions taken from Spanish RD 1113/2006 of 29 September, RD 818/2015 of 11 September, RD 126/2015 of 27 February, RD 1181/2018 of 21 September, RD 1334/1999 of 31 July (repealed except for Article 12 on lots and Article 18 about the language labels must be written in), and RD 1808/1991 of 13 December; and Regional Provisions from Decree 50/Citation1995 of 24 March. The criteria to be contemplated for their suitability were:

Being included as ‘Cheese with the Traditional Characteristics of the Canary Islands’ (Decree 50/Citation1995 of 24 March)

List of compulsory mentions to be met shown on labels:

- The food’s denomination: completed in accordance with the origin of its milk and its maturity. EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011, Spanish RD 1113/2006 of 29 September; Spanish RD 818/201 of 11 September; Spanish RD 126/2015 of 27 February.

- List of ingredients: EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011, Spanish RD 1113/2006 of 29 September and Spanish RD 818/2015 of 11 September.

- Covering and processing cheese surfaces: (Spanish RD 1113/2006 of 29 September and Spanish RD 818/2015 of 11 September).

- Ingredient or technological coadjutant: (EU Regulation No. 1169/201, European Council of 25 October 2011).

- Quantity of specific ingredients or specific categories of ingredients: Fatty matter content. (EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011, Spanish RD 1113/2006 of 29 September and Spanish RD 818/2015 of 11 September).

- Net food quantity: (EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011)

- Minimum duration data or expiry date: (EU Regulation No. 1169/2011,European Council of 25 October 2011)

- Special conditions for conservation and/or use: (EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011)

- The (trade) name and address of the food company operator: (EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011)

- Country or place of origin: (EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011)

- How cheese is to be used: (EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011)

- Nutritional information: (EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011)

- Marked identification: (EU Regulation No. 853/2004, European Council of 29 April 2004)

- Heat treatment: (EU Regulation No. 853/2004, European Council of 29 April 2004)

- Lot (Spanish RD 1334/1999 of 31 July)

- Language labels are written in: (Spanish RD 1334/1999 of 31 July)

II.2. Method

II.2.1. The SWOT analysis for the ‘Artisanal Cheese Sector’

We drew up our own SWOT analysis protocol (see Figure 1), modified according to the data provided by other organizations (AIDER GC Citation2007, Citation2013; MAPA Citation2018; MAPAMA Citation2017; The Regional Canaries Government 2014–2020). This protocol covers various aspects from rural development policies (valuing local products from a given area, promotion, commercialization, food safety, the sector forming). The document provided us the information about deficiencies and weaknesses in the real situation of the artisanal cheese sector. So, this was the basis to plan an specific SWOT analysis to optimize its labelling by assigning a real added value and helping correctly promote the product by considering its local assignation and lack of PDO.

II.2.2. Analyzing labels

The SWOT analysis indicated the necessity to observe the current state in adequacy of the labels of artisanal cheeses without PDO, to consider it as an opportunity to improve their promotion and introduction in commercial circuits outside the local area.

Thus, after collecting labels from farms, the information printed on them was analyzed to verify if it fulfilled the corresponding regulations on food labelling currently in force. This was necessary to obtain the degree of compliance for each of the items pointed by the legal indications for these cheeses.

III. Results and discussion

III.1. A SWOT analysis of cheese labels

By applying the protocol model proposed in Section II.2.1, and provides some evidence for certain SWOT aspects of today’s labelling situation for artisanal cheeses with neither PDO nor sold in containers.

The detected SWOT aspects, which provide a real overview of the situation, evidence the need to study if the information on artisanal cheese labels with neither PDO nor sold in containers is correct in order to provide the benefits that the analysis indicated and to encourage promoting products linked to a given region.

It is important to perform this analysis to obtain a final label that is as accurate and correct as possible because the use of incorrect or confusing terms (especially statements made about health properties) can distort the desired message and consumers’ real perceptions (Lee et al. Citation2013).

It is necessary to consider that the artisanal nature of the cheeses herein presented is appealing to consumers who support healthy lifestyles, which would explain why they seek ‘local food products’ more (Adams and Salois Citation2010) and them being willing to pay higher prices for these products (Asioli et al. Citation2017). Consumers prioritize a product that stands out for being traditional, authentic, artisanal and offering clear traceability (Trabelsi Trigui and Giraud Citation2012) that meet their distinction expectations.

Signs appear more frequently on labels that indicate special quality in response to consumer demands to obtain products that guarantee safety and healthiness (Vannoppen et al. Citation2001).

III.2. Current degree of label compliance

After considering the criteria set out in Section II.1.2, we now go on to indicate the extent of the fulfilment of the labels herein included compared to each item considered in general labelling regulations and on specific cheese labelling.

Food denomination: Its legal or descriptive denomination should appear (EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011). However, this is not necessary for those whose food denomination clearly refers to the substance or product in question (Spanish RD 126/2015 of 27 February). Moreover according to Spanish RD 1113/2006 of 29 September, this ‘cheese’ denomination should be completed in accordance with: milk’s origin (by indicating those species if cow’s milk is not used for cheeses with no specific denomination or are not protected by an individual regulation; «cheese mixture» when milk comes from two species or more, and in descending order of proportions); its maturity (by indicating ‘matured cheese’ or the facultative denomination according to the criteria shown in ):

Table 2. Denomination criteria according to Spanish RD 1113/2006 of 29 September.

The study of the 76 labels herein collected showed that 79% failed to fulfil the information in this section. The recorded failures were due to lack of indications about not only the species for the cheeses made with milk other than cow’s milk, but also the proportions of milk used in cheeses made from milk mixtures.

List of ingredients: After the legend «ingredients», all the ingredients should be included in decreasing weight order (Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011), except for those to which no other ingredient was added other than dairy products, food enzymes, ferments and salt. The ‘cheese mixture’ should indicate the animal species in decreasing weight order, along with their minimum percentages in the mixture (Spanish RD 1113/2006 of 29 September). In this section, non-compliances came to 67.10%, mainly for not indicating species in cheese mixtures, the decreasing weight order or minimum percentages.

Ingredient or technological coadjutant: this includes those ingredients used to produce cheese, can cause allergies or intolerance and are found in the end product, albeit it having been modified (EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011). They should be typographically distinguished, but are unnecessary if the food denomination clearly refers to the substance or product in question.

The present study did not detect non-compliances for this section because all the labels reflected the cheese denomination by referring to the product in question. However, only 5.26% typographically highlighted the ‘milk’ ingredient.

It would be worthwhile these labels specifying that they are food products void of ingredients, additives or ‘free ofs’ so that consumers make fewer mistakes when attempting to understand them (Asioli et al. Citation2017) because it has been shown that such indications on labels influence a product being perceived as healthier and people being willing to pay a higher price for it (Hartmann et al. Citation2018). Thus correct label designing is considered very interesting as information about a product’s healthiness is a determining factor for it to be selected (Hartmann et al. Citation2018).

Cheese surface coverings and processing: According to Spanish RD 1113/2006 of 29 September, other ingredients employed in human food or, if applicable, authorized ingredients, can be used to process cheese surfaces. In the artisanal cheeses with neither PDO nor sold in containers made on the GC Island, oil, gofio (roasted ground corn) or paprika is used for coverings. Of these three, gofio is more likely to cause allergy or intolerance if mixed with cereals containing gluten (wheat, rye, barley, oats, spelt, durum wheat). So it must be declared on labels (EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011).

Consumer health concerns are partly explained by the growing number of diseases related with food allergies and intolerances that some specific food products or components like gluten cause (Asioli et al. Citation2017).

On those studied labels mentioning ‘gofio’, there is no indication of flour differing from that of ‘millet (corn)’. It was not possible to observe the degree of compliance given the impossibility of verifying the surface processing that cheese makers applied to the different cheeses they produce because they systematically label them with the same model.

Quantitative indication of ingredients: According to Spanish RD 1113/2006 of 29 September, the minimum fatty matter content must be indicated per 100 g of product. However, this is not compulsory when it forms part of nutritional labelling. Labels could mention ‘Fatty’ (cheese with 45%–60% fat content of the total dry extract) or ‘Extra-fatty’ (cheese with more than 60% of fat content of the total dry extract). The degree of not complying with fat content information came to 89.5% of the labels because it was either not mentioned or appeared as ‘semi-fatty’.

One study into the impact of healthy labelling (as regards fat and salt contents) examined consumers’ flavour perceptions and cheese preferences (Schouteten et al. Citation2015). It clearly evidenced that the indication of ‘low in fat’ or ‘low salt content’ had an impact on consumers’ expectations and perceptions. An extensive review by Fernqvist and Ekelund (Citation2014) concluded that health-related labels influenced product acceptance, so that the presence of this label information had a negative influence in the sensory consumeŕs perception, in an experiment conducted by Szakály et al. (Citation2020) on Trappista cheese from Hungary. Also, Barros et al. (Citation2016), found that consumers proposed health, sensory and economic conditioning when purchase fresh cheeses from Brazil with mentions about ‘salt content’ or ‘probiotic microorganisms’ on the label.

Net food quantity: EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011 contemplates the exception of it not being compulsory to mention net quantity on products sold as units or weighed before consumers. This item was absent on only 16% of the labels. Net quantity was expressed as units of weight (kilograms or grams) on all the other labels, exactly as the regulation sets out.

In a study on the labelling of cheeses made from raw milk and marketed online in Austria, (Schoder et al. Citation2015), it was observed that according to Directive CE 2000/13 and Regulation No. 853/2004, the non-compliance regarding the information of the net weight was 46.3%.

Minimum duration date or expiry date: The present study took into account only the minimum duration date owing to the maturity times of cheeses (semi-hard and hard), as set out in Art. 24 of EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011. The following must be included: «best before … », followed by the day and month for those cheeses whose duration was less than 3 months (semi-hard); «best before … », followed by the month and year for these cheeses with a longer duration (hard). A reference about conservation conditions should appear to ensure the indicated duration. Non-compliances of this labelling requirement were found on 58% of the labels because it appeared as an ‘expiry date’, or the day, month or year was not mentioned. A lower non-compliance (39.8%) was detected by Schoder et al. (Citation2015) in the information about the expiry date on the labelling of Austrian cheeses made from raw milk.

Thompson et al. (Citation2020), in their study about the verification by the consumers of the expiry-dates in the labels of dairy products, valued the importance of this factor as influencing in the food waste habits.

Special conservation and/or use conditions: This indication, as set out in EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011, and also in Spanish RD 1113/2006 of 29 September, should appear in its matured cheese definition. The semi-hard and hard cheeses from the GC Island, made with pressed paste (AIDER G.C Citation2007) should be kept at 8°C–12°C (Romero del Castillo and Mestres Lagarriga Citation2004; ICCA Citation2018). Of all the studied labels, 86.84% did not meet this section as they either failed to mention these details or indicated inappropriate temperatures. Schoder et al. (Citation2015) detected that there was non-compliance with the information on the preservation requirements in the 50.9% of the cheeses sold online in their study.

In a study on the implementation of the HACCP system in the production line of UF fresh cheese (El-Hofi et al. Citation2010), it is demanded to include as labelling requirement of this ready-to-eat product, the instruction to the consumer for keeping refrigerated it, as a control point.

The (trade) name and address of the food company operator: The name, trade name and address of the operator or importer in charge of commercializing food should appear as set out in EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011. All the studied labels correctly showed the information included in this section. On the contrary, in the study carried out by Schoder et al. (Citation2015), it is showed that 38.8% of the labels lacked in this information.

Country or place of origin: In line with EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011, which expects origin to be displayed if its absence is misleading for consumers, and with Spanish RD 1181/2018 of 21 September, which expects dairy product labels to indicate «Milk’s origin: (place where milk was milked and processed)» (as milking and processing operations may concur on the same farm in the same country), this information must appear on the labels of all the cheeses that have these characteristics.

No such information on the traceability of the milk employed as an ingredient was found on the labels herein studied, perhaps because this regulation was recently published. Therefore, including this information on the new labelling model is proposed. According to (Trabelsi Trigui and Giraud Citation2012), more importance is attached to the region of origin than to the country or brand, and it strongly influences consumer choices. Regional products help to support local producers, and confer social, sensorial and emotional values that consumers appreciate more than other functional labelling aspects related to nutrition and health.

How cheese is to be used: this indication was not considered necessary as it would only come into play if such information were missing or it was difficult to suitably use this food (EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011).

Nutritional information: As the studied cheeses are commercialized as whole units, labels are directly stuck onto rinds of cheeses not placed inside containers. Hence including nutritional information on labels is not compulsory, in accordance with Spanish RD 1113/2006 of 29 September, EU Regulation No. 1169/2011, European Council of 25 October 2011 and Spanish RD 818/2015 of 11 September, which make this indication exempt on cheeses not sold in containers.

Nonetheless, Trabelsi Trigui and Giraud (Citation2012) found that the product information shown on labels about product composition influenced their commercialization, stimulating buyers to make healthier food choices when the nutrition information is easily accessible, comprehensible and consistent (Watson et al. Citation2014). In 2013 Lee et al. also conducted a study to detect the influence that the term ‘organic’ marked on food labels had on consumers. They found that consumers perceived them to contain fewer calories and offered a higher nutritional value, and were willing to pay more for them. Hartmann et al. (Citation2018) detected that consumers preferred those products that specified lack of certain components (free of) on labels and perceived them as being healthier.

Lot: According to Art. 12 of Spanish RD 1334/1999 of 31 July, the ‘lot’ indication or the letter «L» must appear on labels. This information did not correctly appear on 20% of the studied labels because it was missing or proved misleading/incorrect.

Language labels must be written in: Article 18 of Spanish RD 1334/1999 of 31 July states that compulsory information on labels must be expressed in at least the official State language. All our studied labels met this requirement.

Marked identification: As products were of animal origin, this mark must be oval and include the name or initials of the country in question, the establishment’s authorization number and the ‘Economic Community’ initials (R (EU), in line with EU Regulation No. 853/2004, European Council, of 29 April 2004). Of all the studied labels, 61.8% displayed mistakes in this section, usually when abbreviating countries, e.g.: Spain (‘ES’) and Economic Community (‘EC’).

Heat treatment: The legend «made with raw milk» must appear on labels for being products that do not undergo milk heat treatment (EU Regulation No. 853/2004, European Council, of 29 April 2004). This information did not appear on 27% of the labels or it indistinctly formed part of other items. Displaying this information on labels is very important because the results of some studies (Asioli et al. Citation2017) indicate that increasingly more consumers from industrialized countries are showing more interest in knowing production methods and the components in the food products they purchase.

Dagmar Schoder et al. (Citation2015), found that 4.6% of the cheeses in their study were erroneously labelled as ‘made with pasteurized milk’ or ‘with heat treatment’, and the legend ‘made with raw milk’ was not evident in 36% of the cheeses.

III.2.1. Information about cheeses with PDO

Unlike the artisanal cheeses with no PDO that are the target of the present study, the protection condition of those cheeses with PDO marks certain differences on their labels. In the Canaries, cheese production is considerable and cheeses belong to three PDO types: PDO Queso Majorero (Order of 16 February 1996) (Spanish Goberment Citation1996) on the Fuerteventura Island; PDO Queso Palmero (Order of 31 August 2001) (Spanish Goberment Citation2001) on the La Palma Island; PDO Queso de Flor de Guía/Queso de Media Flor de Guía/Queso de Guía (Royal Decree RDGIAA of 15 April 2008) (Spanish Goberment Citation2008; European Communities Citation2006, Citation2010), which covers three municipalities on the GC Island, namely Gáldar, Moya and Santa Maria de Guía. On them, apart from requirements stated by general legislation, their own regulation expects the specific inclusion of the following items on their labels ():

Cheese made by cheese makers on their own farms with milk from their own herds

Cheese made by cheese makers on their own farms with recently milked raw milk exclusively from their own herds

Cheese made with raw milk from cheese makers’ own cattle

Table 3. The characteristic aspects expected to be shown on labels of cheeses with DO from the Canaries.

Consumers increasingly demand quality guarantees, which they look for in food label information to guide their preferences, as previously verified in products with PDO and PGI (Protected Geographic Indication) (Trabelsi Trigui and Giraud Citation2012) as a sign of their authenticity, and of guaranteeing their traceability and the sensorial quality related to their place of origin. However, not always they are willing to pay more for the quality signal provided by de PDO label, as could be contrasted by Bonnet and Simioni (Citation2001), with French Camembert cheeses.

Agro-food products from southern Europe more frequently take PDO as a quality distinction and an authenticity-based system (Krystallis et al. Citation2012) as more ethical production practices and sustainability aspects are sought (Krystallis et al. Citation2012, Citation2017). This practice also helps maintain local production in areas where origin is linked to both the tradition and quality of food items.

III.3. Proposed model with full information to be placed on labels

In Citation2005, Cheftel reviewed the legal horizontal and vertical principles for labelling by studying all the points indicated in European regulations and analyzing information on labels, which was provided on a voluntary basis at that time (allergens, quality and origin, organic production and nutritional information). This author concluded the importance of improving the labelling of traditional foods, new foods and genetically modified foods and proposed some recommendations. Similarly, the study by Katz and Williams (Citation2011) evidenced the need for a clear definition of what a ‘clean label’ is with it specifying lack of artificial ingredients and natural production methods.

Therefore, we stress the importance of a correct up-to-date food label design to be applied to artisanal cheeses with no PDO to help consumers understand and better perceive them, to act as a guide to cheese makers as a communication process, and to support those who intend to introduce these products into a specific legal framework.

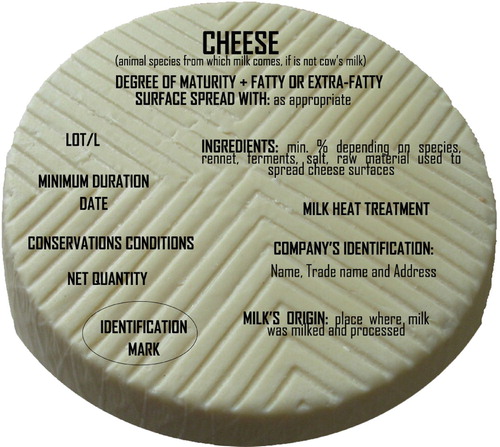

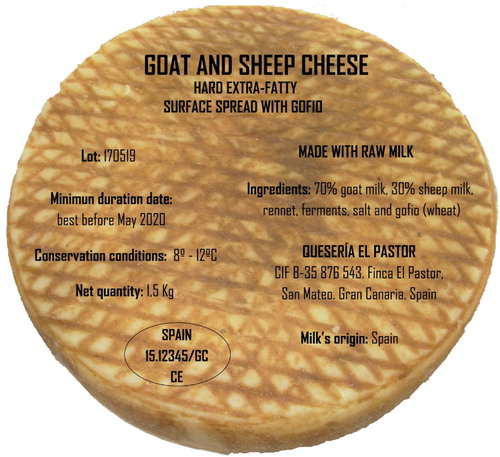

Based on the obtained results, we list the aspects that need to appear on all the labels used with artisanal cheeses produced with neither PDO nor sold in containers as follows:

- Cheese (animal species from which milk comes if not cow’s milk)

- Degree of maturity + ‘fatty or extra-fatty’

- Surface spread with: oil, gofio or paprika, as appropriate

- Milk heat treatment: pasteurized or ‘made with raw milk’

- Ingredients: min. % depending on species, rennet, ferments, salt, raw material used to spread cheese surfaces

- Lot / L: numerical identifying code

- Minimum duration date

- Conservation conditions: temperature

- Net quantity

- Company’s identification: name, trade name and address

- Identification mark

- Milk’s origin: place where milk was milked and processed

- The figures below generally illustrate this information on the label model for all the cheeses prepared with neither PDO nor sold in containers (), along with an example of specific cheeses with these characteristics commercialized in Spain ().

IV. Conclusion

The SWOT analysis of the labels of artisanal cheeses with neither PDO nor sold in containers on the Canaries evidences the need to correctly design up-to-date labels for these products for them to adapt to the latest changes set out in current regulations. It would serve as a tool to make better known how to further improve the qualities of these cheeses, which would favour their competitiveness in the sector by helping consumers select them.

The defects currently found, such as cheese makers using the same label for different artisanal cheese varieties (according to milk’s origin, maturity time and/or surface covering), or lack of legends specifying the use of raw milk or surface coverings, which could be considered to be added value, should be corrected by encouraging cheese makers to train in specific food safety labelling matters according to regulations.

A correct label model that specifies the special characteristics of these artisanal cheeses may help to differentiate the distinct quality marks on the labels of cheeses with no PDO on a par with those protected by a recognized quality mark. The information of this regulation-based proposal would include other aspects like traceability (compulsory) and nutritional value according to degree of maturity (voluntary), which would make them more acceptable by all EU consumers.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to their families and farm cheese producers for all the support they provided.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adams DC, Salois MJ. 2010. Local versus organic: a turn in consumer preferences and willingness-to-pay. Renewable AgricFood Syst. 25(4):331–341.

- Asioli D, Aschemann-Witzel J, Caputo V, Vecchio R, Annunziata A, Næs T, Varela P. 2017. Making sense of the “clean label” trends: a review of consumer food choice behavior and discussion of industry implications. Food Res Int. 99:58–71.

- Barros CPD, Rosenthal A, Walter EHM, Deliza R. 2016. Consumers’ attitude and opinion towards different types of fresh cheese: an exploratory study. Food Sci Technol. 36(3):448–455.

- Bonnet C, Simioni M. 2001. Assessing consumer response to protected designation of origin labelling: a mixed multinomial logit approach. Eur Rev Agric Econ. 28(4):433–449.

- Canary Government. 1995. Decree 50/1995, 24 March, by which the Register of Makers of Cheeses with Traditional Characteristics was set up for those premises with limited production on the Canaries to govern their operation. Official Canaries Publication No 49, Friday 21 April 1995, pp. 3206–3210.

- Canarian Institute of Agro-Food Quality (ICCA) (GOBCAN). 2009. Canary Cheese Promotion. https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/agp/icca/temas/promocion/concursos/worldcheese2009/indexwc2009.html. Consulted (20.09.2020).

- Canarian Institute of Agro-Food Quality (ICCA). 2018. Regional Canaries Government. (GOBCAN). Guía de Quesos de Canarias. Regional Canaries Government. Canary Islands. https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/agp/icca/temas_calidad/quesos/ Consulted (20.09.2020).

- Cheftel CJ. 2005. Food and nutrition labelling in the European Union. Food Chem. 93:531–550. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.11.041.

- Donet Sepúlveda JC, Juárez Varón D. 2015. Cuadernos de Marketing y Comunicación Empresarial. Vol. I. 2014. Plan de Marketing para la Creación de una Marca Infantil en el Sector Textil Hogar. Area de Innovación y Desarrollo S.L. http://hdl.handle.net/10251/83663.

- El-Hofi M, El-Tanboly ES, Ismail A. 2010. Implementation of the Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) system to UF white cheese production line. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Technologia Alimentaria. 9(3):331–3422.

- European Communities. 2004. Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004, laying down specific hygiene rules for on the hygiene of foodstuffs. Official J Eur Communities L. 139:55.

- European Communities. 2006. Regulation (EC) no 510/2006 of the Council «Queso de Flor de Guía»/«Queso de Media Flor de Guía»/«Queso de Guía» No CE: ES-PDO-005-0605-21.05.2007 IGP () DOP(X). Official J Eur Communities C. 315:18–25.

- European Communities. 2010. Commission Regulation (EU) No 783/2010 of 3 September 2010 entering a name in the register of protected designations of origin and protected geographical indications [Queso de Flor de Guía/Queso de Media Flor de Guía/Queso de Guía (PDO)]. Official J Eur Communities. 234:3–4.

- European Communities. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers, amending Regulations (EC) No 1924/2006 and (EC) No 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Commission Directive 87/250/EEC, Council Directive 90/496/EEC, Commission Directive 1999/10/EC, Directive 2000/13/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Directives 2002/67/EC and 2008/5/EC and Commission Regulation (EC) No 608/2004. Official Journal of the European Communities. L 304, of 22 November 2011, pp. 18–63.

- Fernqvist F, Ekelund L. 2014. Credence and the effect on consumer liking of food – a review. Food Qual. Preference. 32:340–353.

- Hartmann C, Hieke S, Taper C, Siegrist M. 2018. European consumer healthiness evaluation of ‘free-from’ labelled food products. Food Qual Prefer. 68:377–388.

- Inter-Insular Council of GC (Cabildo G.C.). 2018. http://cabildo.grancanaria.com/-/noticia-los-quesos-de-gran-canaria. Consultado el 4 de diciembre de 2018.

- Inter-Insular Council of Rural Development of GC (AIDER G.C). 2007. “Descubriendo Nuestro Quesos. Queso Artesano de Gran Canaria”. Asociación Insular de Desarrollo Rural de Gran Canaria (AIDER G.C.) Gran Canaria. ISBN 978-84-612-137. Depósito legal GC.550-2007.

- Inter-Insular Council of Rural Development of GC (AIDER G.C). 2018. Quesos de Gran Canaria. http://www.quesosdegrancanaria.com/. Consulted on 17 September 2018.

- Inter-Insular Council of Rural Development of GC (AIDER G.C). Programa Comarcal de Desarrollo Rural de Gran Canaria 2007–2013.

- Katz B, Williams LA. 2011. Cleaning up processed foods. Food Technol. 65(12):33.

- Krystallis A, Chrysochou P, Perrea T, Tzagarakis N. 2017. A retrospective view on designation of origin labeled foods in Europe. J Int Food Agribusiness Marketing. 29(3):217–233.

- Krystallis A, Grunert KG, de Barcellos MD, Perrea T, Verbeke W. 2012. Consumer attitudes towards sustainability aspects of food production: insights from three continents. J Marketing Manage. 28:334–372. doi:10.1080/0267257x.2012.658836.

- Lee WCJ, Shimizu M, Kniffin KM, Wansink B. 2013. You taste what you see: do organic labels bias taste perceptions? Food Qual Prefer. 29(1):33–39.

- Martínez Pedros D, Milla Gutiérrez A. 2012. La elaboración del plan estratégico y su implantación a través del cuadro integral. Ediciones Díaz de Santos.

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente (MAPAMA). The Spanish Government. 2017. Diagnóstico y Análisis Estratégico del Sector Agroalimentario Español. Análisis de la cadena de producción y distribución del sector de lácteos.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Fishing and Food (MAPA). 2018. The Spanish 2017 Food Intake Report. The Spanish Government.

- Muñiz L, González LM. 2010. Planes de negocio y estudios de viabilidad: software con casos prácticos y herramientas para elaborar DAFO y evaluar un plan de viabilidad. Profit Editorial I.

- Regional Canaries Government. (PDR) Plan de Desarrollo Rural Canarias 2014-2020, Estrategia Europa 2020.

- Romero del Castillo R, Mestres Lagarriga J. 2004. Productos lácteos. Tecnología Univ. Politèc. de Catalunya. Edicions UPC.

- Ruiz-Morales FA, Fresno Baquero MR, Barriga Velo D, Haba Nuévalos E. 2016. El queso artesano ligado a la leche de cabra en España: un sector en continua evolución. Tierras Caprino. N° 16 - pág 44.

- Schoder D, Strauß A, Szakmary-Brändle K, Wagner M. 2015. How safe is European Internet cheese? A purchase and microbiological investigation. Food Control. 54:225–230.

- Schouteten JJ, De Steur H, De Pelsmaeker S, Lagast S, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Gellynck X. 2015. Impact of health labels on flavor perception and emotional profiling: a consumer study on cheese. Nutrients. 7(12):10251–10268.

- Spanish Goverment. 1996. Order de 16 de febrero de 1996, por la que se reconoce la Denominación de Origen Queso Majorero y se aprueba su Reglamento y el de su Consejo Regulador. Boletín Oficial del Estado núm. 223, de 14 de septiembre de 1996, pp. 27883–27890.

- Spanish Goverment. 2001. Orden de 31 de agosto de 2001, por la que se ratifica el Reglamento de la Denominación de Origen «Queso Palmero» y de su Consejo Regulador.

- Spanish Goverment. 2008. (RDGIAA) Resolución de 15 de abril de 2008, de la Dirección General de Industria Agroalimentaria y Alimentación, por la que se concede la protección nacional transitoria a la denominación de origen protegida «Queso Flor de Guía y Queso de Guía» Boletín Oficial del Estado núm. 137, de 6 de junio de 2008, pp. 26260–26263.

- Spanish Royal Decree 1113/2006 of 29 September, by which quality marks were passed for cheeses and processed cheeses. Daily Spanish Government Publication No. 239, 6 October 2006.

- Spanish Royal Decree 1181/2018, 21 September about indicating the origin of the milk used as an ingredient on the labels of milk and dairy products. Daily Spanish Government Publication No. 230, Saturday 22 September 2018, pp. 91664–91669.

- Spanish Royal Decree 126/2015 of 27 February, by which the general regulation was passed for food information from foods not sold in containers to end consumers and groups, for foods sold in containers at points of sale upon comsumers’ requests, and for those sold in containers by business owners for retail sale. Daily Spanish Government Publication No. 54, Wednesday 4 March 2015, pp. 20059–20066.

- Spanish Royal Decree 1334/1999 of 31 July, by which the general labelling, presentation and advertising of food products was passed (tacitly repealed, except for Art. 12 on lots and Art. 18 on the language labels are written in). Daily Spanish Government Publication No. 202, Tuesday 24 August 1999, pp. 31410–31418.

- Spanish Royal Decree 1808/1991 of 13 December, by which the mentions or marks that identify lots to which a food product belongs were passed. Daily Spanish Government Publication No. 308, 25 December 1991.

- Spanish Royal Decree 818/2015 of 11 September, by which Annexes I and II of Royal Decree 1113/2006, 29 September were amended, and by which the quality regulations of cheeses and processes cheeses were passed, and by which the second transitory provision was amended of Royal Decree 4/2014, 10 January, by which the quality regulation for meat, parma ham, cured pork shoulder and Iberian pork loin were passed. Daily Spanish Government Publication No. 219, Saturday, 12 September 2015, pp. 80678–80681.

- Spanish Royal Decree 1181/2018 of 21 of September, relative to the milk origin used as ingredient in the labeling of the milk and dairy products.

- Szakály Z, Soós M, Balsa-Budai N, Kovács S, Kontor E. 2020. The effect of an evaluative label on consumer perception of cheeses in Hungary. Foods. 9(5):563.

- Thompson B, Toma L, Barnes AP, Revoredo-Giha C. 2020. Date-label use and the waste of dairy products by consumers. J Cleaner Prod. 247:119174.

- Trabelsi Trigui I, Giraud G. 2012. Brand proneness versus experiential effect? Explaining consumer preferences towards labeled food products. J Global Scholars Marketing Sci. 22(2):145–162. doi:10.1080/12297119.2012.655097.

- Vannoppen J, Verbeke W, Huylenbroeck GV. 2001. Motivational structures toward purchasing labeled beef and cheese in Belgium. J Int Food Agribusiness Marketing. 12(2):1–29.

- Watson WL, Kelly B, Hector D, Hughes C, King L, Crawford J, Chapman K. 2014. Can front-of-pack labelling schemes guide healthier food choices? Australian shoppers’ responses to seven labelling formats. Appetite. 72:90–97.