?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The study was conducted for describing the rearing and husbandry practice of indigenous goats in the North Shewa zone. A total of 216 farmers were interviewed for the household survey. Data collected through a questionnaire (survey) were described by descriptive statistics using SPSS. The first objective of keeping goats in all districts was for income. Natural pasture (shrubs and bushes) and river water were the major sources of goat feeding and watering, respectively both in dry and wet seasons in the three districts. Among the interviewed goat keepers 94.4% in Berehet, 84.7% in Basona-Worena and 90.3% in Minjar-Shenkora had their own indigenous breeding male goat. The average flock size per monitored households in Berehet, Basona-Worena and Minjar-Shenkora districts was 14.70 ± 10.95, 7.43 ± 3.94 and 14.52 ± 11.36 goats, respectively. Growth rate, body conformation and coat colour for the breeding buck and litter size, body size or appearance and pedigree for does were the first, second and third selection criteria, respectively in all districts. Feed shortage, disease and labour shortage were the first, second and third-ranked constraints for goat production in the study districts, respectively.

1. Introduction

Goat (Capra hircus) is one of the most important components of the world’s livestock-based farming system, as they are multi-purpose animal producing meat, milk, hide, fibre, manure and hauling light loads. In the world goats traditionally have a strong influence on the socio-economic life of human populations, especially in rural and less-favoured regions. During 2000–2013 there was an important increase in the goat population worldwide (33.79% or an average per year of 2.6%) (Skapetas and Bampidis Citation2016). Among the continents, Asia constantly holds the first place having a contribution to the total goat population of 59.38% and an increase in goat numbers during 2000–2013 by 30.23%. Africa takes second place with a 35% contribution and increase (Skapetas and Bampidis Citation2016).

In Africa goats are kept in varied agro-ecological zones and management systems. They also kept in small herds on diverse farms in the continent, from the humid coastal zones in West Africa to the highlands of Ethiopia (Peacock Citation2005). The majority of the goat population is found in large flocks in the arid and semiarid lowlands which are the characteristics of pastoral and agro-pastoral production systems (Tegegn, Kefyalew, and Solomon Citation2016). Goats play an important socio-economic role in many African local communities. The African goat population represents 30% of Africa’s ruminant livestock and produces about 17 and 12% of its meat and milk, respectively (Agossou et al. 2017). Goats are mainly kept in the traditional system. The traditional system is made up of pastoral systems and agropastoral systems. Goats are mainly kept to produce milk, meat or fibre Mahmoud (Citation2010). Since goats are playing an important economic source of income (meat, milk, fibre, job) in developing countries, including SSA countries, studying and maintaining its genetic diversity in adaptive agro-ecological zones is very important Patrick Baenyi et al. (Citation2020).

Ethiopia has the largest livestock population in Africa and is a homeland of a large number of goat populations which are kept in various production systems and different agro-ecological zones of highlands, sub-humid, semi-arid and arid environments (Getinet Citation2016). Livestock plays an important role in providing export commodities, such as live animals, hides and skins to earn foreign exchanges for the country (CSA Citation2012). Goat production is one of the integral parts of livestock farming activity of the country. The majority of the goat population is found in large flocks in the arid and semi-arid Lowlands. Goats in the highlands are widely distributed in the mixed crop-livestock production systems with very small flock sizes (Tesfaye Citation2004). Almost all goat population is managed by resource-poor smallholder farmers and pastoralists under traditional and extensive production systems (Solomon Citation2014).

According to CSA (2021), the number of goats reported in the country is estimated at about 30.20 million and with respect to breed, almost all goats are indigenous accounting for 99.99% (CSA Citation2012). The previous research (FARM Africa Citation1996) on phenotypic characterization indicated that there are about 12 goat types in Ethiopia, while a genetic study that used microsatellite markers showed only eight distinctively different types of goats in Ethiopia (Tesfaye Citation2004). However, the current molecular study on domestic goats by Getinet (Citation2016) does not support the former classifications of the indigenous goat populations. After a detailed analysis of the goat population based on production systems, agro-ecologies, goat families, admixture and phylogenetic network analyses he classified the 12 Ethiopian goat populations into seven goat types.

Goats are browsers and highly selective feeders and have a strategy that enables them to thrive and produce even when feed resources, except bushes and shrubs, appear to be non-existent. Thus, the presence of goats in mixed species grazing systems can lead to a more efficient use of the natural resource base and add flexibility to the management of livestock. This characteristic is especially advantageous in fragile environments (Adane and Girma Citation2008). According to Workneh (Citation1992), the habitats of these indigenous goat breeds extend from the arid lowlands (the pastoral and agro-pastoral production system) to the humid highlands (mixed farming systems) covering even the extreme tsetse-infested areas of the country. Furthermore, goats have a small body size, broad feeding habits, adaptation to unfavourable environmental conditions and short reproductive cycles. These provide them with a comparative advantage over other species to suit the circumstances of especially resource poor livestock keepers (Alemayehu Citation1993). They play an important socioeconomic role as food source, milk, skin, manure, income generation, prestige, wealth status and socio-cultural wealth in rural areas (Tesfaye Citation2009; Bekalu Citation2014; Alubel Citation2015; Alefe Citation2014). In addition to these, there are no banking facilities in rural areas and an easy way to store cash for future needs is through the purchase of small ruminants (IBC 2004).

Despite the wide distribution and large size of the Ethiopian goat population, the productivity and the contribution of this sector to the national economy are below the potential. Goat production accounts for 16.8% of the total meat supply (Ameha Citation2008) and 16.7% of milk consumed in the country (Tsedeke Citation2007). The average annual meat consumption per capita in the country is estimated to be 8 kg/year which was lower than the global average meat consumption (38 kg/year) and the average meat consumption of the USA (124 kg per capita per year) (Ameha Citation2008). The average carcass weight of Ethiopian goats is 10 kg, which is the second lowest in sub-Saharan Africa (Adane and Girma Citation2008). This may be due to different factors such as poor nutrition, the prevalence of diseases, lack of appropriate breeding strategies and poor understanding of the production system as a whole (Tesfaye 2009). Thus, it is critical to improve the low productivity to satisfy the increasing demand for animal protein and improve the livelihood of livestock keepers and the economic development of the country at large.

For designing a sustainable genetic improvement programme, considering the compatibility of the genotypes with the farmers’ breeding objectives and the production systems is crucial (Markos Citation2006). To design improvement measures relevant to specific systems and thereby properly respond to the growing domestic and foreign demands for live goats and goat products, characterizing different goat breeds/populations, describing their external production characteristics in a given environment, managing and identifying different constraints are important. A few breeding programmes had been established in developing countries, but most of them failed Mahmoud (Citation2010). Most of these projects have focused on goat improvement rather than on educating the people who kept the animals. Fewer selected and well-characterized breeds for producing milk, meat or fibre have been developed, while the majority are not genetically exploited as a result of the lack of selection schemes and breeding organizations (Galal et al. Citation1996). In addition, the production systems are mostly extensive, which make record-keeping very difficult, resulting in underutilization and inadequate exploitation of many potentially valuable breeds Mahmoud (Citation2010). The research and breeding work has been carried out mainly by research organizations, with little participation from the farmers. Several crossbreeding programmes have also been established in different countries to obtain suitable and improved genotypes Mahmoud (Citation2010).

Even though various research and development activities have been carried out in the past, no significant increase in productivity was achieved in the country (FARM Africa Citation1996; Alemayehu Citation1993; Nigatu Citation1994; Mahilet Citation2012; Belete Citation2013; Alefe Citation2014; Ahmed Citation2013; Alubel Citation2015; Tsigabu Citation2015; Feki Citation2013). In addition, in the Amhara region Halima et al. (Citation2012), Hulunim (Citation2014) and Alubel (Citation2015) characterized the phenotypic characteristics, goat production systems, and production and reproduction performances. However, the North Shewa zone is a less focused area, especially on goat genetic resources rather than two decades of FARM Africa (Citation1996) work. To make the best use of goat keeping operations, it is important and a prerequisite to have a comprehensive understanding of the whole situation by assessing the production environment, husbandry and rearing practices of farmers.

From the Amhara region, the North Shewa zone has the second largest goat population around 820,947 heads (CSA 2015–2016) this may be the significance of goats rather than other livestock species. Despite its large size and significance in terms of meat, cash income and skin production, there is a lack of information on these goat genetic resources. In addition, the absence of adequate information on the characteristics of breeds potentially leads to wrong decisions and genetic erosion through cross-breeding, replacement and dilution (Zewdu Citation2008). Thus, assessing the rearing and husbandry practices of farmers on this goat genetic resource is essential for efficient utilization and conservation of genetic resources as well as to plan different developmental strategies like community-based genetic improvement programmes.

1.1. Objectives

1.1.1. General objective

➢ Assessment of rearing and husbandry practice of indigenous goat population in the North Shewa zone

1.1.2. Specific objectives

➢ To assess the husbandry practice of indigenous goats in the study area

➢ To assess the rearing practice of goats in the study area

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

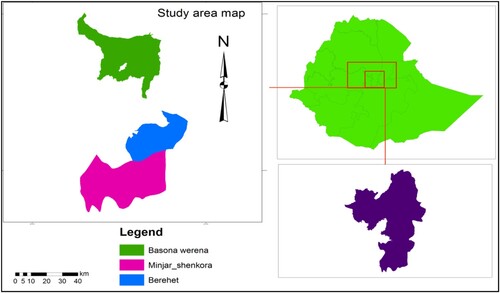

This study was conducted in three districts namely, Berehet, Minjar-Shenkora and Basona-Worena of the North Shewa zone of the Amhara regional state ().

2.2. Sampling techniques and sample size determination

2.2.1. Sampling techniques

Based on the information obtained from the secondary data sources the districts (twenty-seven) in the zone were stratified according to their agro-ecological variations low land (<1500 m above sea level), midland (1500–2500 m above sea level) and high land (>2500 m above sea level). From each agroecological zones, one district was purposively selected based on a relatively large goat population and agro-ecology representations. From each district, three kebeles were purposively selected again based on a relatively large goat population and agro-ecology representations. From each sample kebele households were stratified according to their ownership of goats; goat owners (households which have at least two goats) and not goat owners (households which have ≤ one goat). From the total goat owner households, representative sample households were randomly selected for the interview about their husbandry practices.

2.2.2. Sample size determination for household and goats

A sample size of the households was determined according to the formula given by Cochran (Citation1977).

n = sample size; Z = standard normal deviation (1.96 for 95% confidence level); P = 0.15 (estimated population variability proportion, 15%); q = 1-P i.e. (0.85); e = level of precision (0.05).

Based on the formula, to increase the accuracy adding up to 10% of the sample size on this calculated sample is recommended. 196*10/100 = 19.6 = 20, 196 + 20 = 216 goat owner households were interviewed about management practices.

2.3. Data types and methods of data collection

2.3.1. Data types and collection methods for husbandry practices

For each household survey, structured and pre-tested questionnaires were used. The structured questionnaires were adopted to collect all the pertinent information in a single visit by formal survey methods (ILCA Citation1990). The livestock survey tool developed by Workneh and Rowlands (Citation2004) was used as a checklist in designing the questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed to obtain information from respondents on household socio-economic characteristics of farmers, the composition of livestock species, breeding practices of goats; husbandry practices and goat production constraints. Group discussions were carried out with two groups per district. The discussion was held with DAs, model farmers, village leaders and socially respected individuals.

2.4. Data management and statistical analysis

All data gathered during the study period were coded and recorded in Microsoft Excel 2007. Data generated from questionnaires were described and summarized by using descriptive statistics. Chi-square (x2) test was carried out to assess the statistical significance among categorical variables using district as a fixed effect. Index was calculated for data that need ranking like reasons for keeping goats, selection criteria associated with breeding females and males, feed resources for goats during the dry and wet seasons, goat production constraints and disease observed. The formula for index (Sum of (3 x ranked first + 2 x ranked second + 1 x ranked third) given for an individual reason divided by the sum of (3 x ranked first + 2 x ranked second + 1 x ranked third)) for all reasons (Kosgey 2004).

3. Result and discussion

3.1. Farming system and non-farming activities

In the study area mixed crop-livestock production system is an important way of life for the community. A large number of animals like goats are kept and an immense area of land is cultivated. In the Basona-Worena district livestock has a major role in the source of income than Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora districts due to the low potential of the land they have for crop production and small land size per household relative to the Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora districts (). Similarly, Solomon et al. (Citation2010) indicate that the contribution of livestock production is higher than other farm and off-farm activities in the highland of the Amhara region of the North Shewa zone. On the other hand, Tariku et al. (Citation2021) reported that livestock is the main source of income in the Loka Abaya district. During the off-season (when there is no crop cultivation activity) the farmers in the study areas were participating in off-farm activities such as local trading (38.7%), making of charcoal (22.6%) and collection of fuel wood for sale and daily labourer in Basona-Worena district. Similarly, in Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora also participated in local trading (19.6% and 26.2%), cultivation of vegetables (33.9% and 11.9%) such as tomato, cabbage and onion as a daily labourer along with farming activities and making of charcoal and collection of fuel wood for sale (30.4% and 33.3%) which was mentioned as major offseason activities in the study areas, respectively. Similarly, Hulunim (Citation2014) who reported the main reasons (limited income and seasonal nature of agriculture activities and large family size) why farmers in rural Ethiopia participated in off-farm activities and at Siti relatively high percentage of respondents (33.04%) were practiced charcoal making and collection of fuel wood for sale, respectively.

Table 1. The contribution of farming and non-farming activities for the source of food and cash income.

3.2. Composition of livestock per household

The number of goats is higher than all livestock species recorded per household (). This is due to the behaviour of tolerating feed shortage more than other livestock. Respondents in Berehet (lowland) and Minjar-Shenkora (midland) districts had significantly (P < 0.05) higher goats (16.8 and 16.60) than Basona-Worena district (9.80). On the other hand, the average number of sheep per household was significantly (P < 0.05) high (9.80 ± 2.67) in the Basona-Worena district (high land agro-ecology). This may be due to the agro-ecological effect (adaptation behaviour of goats and sheep). Livestock species which constitute the largest share in the value of livestock assets of a household are defined as the principal animal (Fredu et al. Citation2009). Moreover, the trend of goat rearing was increasing due to their significance as they can tolerate different environmental factors than other livestock, the trend/emphasis of farmers that they give for each livestock; market demand and the level of each livestock significance for their livelihood make the proportion difference. Similarly Solomon et al. (Citation2010) reported that the specific factors determining flock size include the availability of land and feed, the role of livestock as the major source of livelihood and the reliability of crop production. Despite the shortage of grazing land and crop residues, large flocks of sheep are maintained in subalpine areas.

Table 2. Livestock holding per household.

The average number of goats owned per household was 14.40. On the contrary, this result was higher than the report of FARM AFRICA (Citation1996), Mahilet et al. (2012) and Ahmed (Citation2013) who reported 10, 7.6 and 8.12 in Central Highland, Horro, Guduru, Wollega zone and East Hararghe zone, respectively. This could be due to agro-ecological difference, feed resource availability and incidences of diseases. On the other hand, Abraham et al. (Citation2017) reported that the mean flock size of goats in Begait Goat is 43.67 ± 17.49 goats per household which are higher than this result. This difference may be the agro-ecological or farming system difference.

3.3. Goat flock structure by age group

There is a significant (p < 0.05) difference in the average goat populations in each of all age and sex categories across districts except castrated goats (). The proportion of the different categories of animals reflects the management decision of the producers which, in turn, is determined by their production objectives (Solomon et al. 2010). Breeding does take a major portion (5.4 ± 4.3, 2.7 ± 1.1 and 5.7 ± 4.8) in Berehet, Basona-Worena and Minjar-Shenkora districts, respectively, followed by kids <6 months. This result is similar to (Yemane et al. Citation2020; Hulunim Citation2014; Alefe Citation2014; Belete Citation2013; Alubel Citation2015) who reported that doses are higher than the other flock structure age group. The larger proportion of breeding implies the production of a larger number of kids and that was the reason for this large proportion of kids in the study area which has a direct impact on selection intensity and breeding. On the contrary, Tariku et al. (2020) reported 2.49 ± 0.14 which is lower than this result. The average goat flock size as well as adult females and kids less than 6 months owned per household in Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than Basona-Worena district. The proportion of kids <6 months, male kids 6–12 months and bucks (>1 year) in the Berehet district were slightly higher than the contribution of their counterparts in the Basona-Worena and Minjar-Shenkora districts. On the other hand in the Minjar-Shenkora district the proportion of female kids 6–12 months and doe (>1 year) was higher than Berehet and Basona-Worena districts. The relatively higher flock size of goats indicates the importance of goat production was higher and they have a strong interest in goat breeding in the community.

Table 3. The flock structure of goats.

3.4. Purpose of keeping goat

The primary breeding objective of goat keepers was producing marketable goats for generating more income which can be used for different household expenses in all study areas with index values of 0.41, 0.56 and 0.42, in Berehet, Basona-Worena and Minjar-Shenkora districts, respectively. This was important for the payment of social duties, emergency cases, and educational fees and for other household expenses like purchasing food, especially at the time of drought in Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora districts. In agreement Ahmed et al. (2013) reported that most of the farmers in all districts primarily reared goats for generating income which is used for emergency cases. In contrast Laouadi et al. (Citation2018) reported that the primary reasons cited for goat keeping are obtaining milk or meat for home consumption 58.5%. Meat and saving were the second and third objectives in all study districts with index values of 0.14, 0.07 and 0.213 in Berehet, Basona-Worena and Minjar-Shenkora districts, respectively (). This is similar to the report of Wondim and Teshager (Citation2022) and Tegegn et al. (2016) who reported that the first, second and third objectives of farmers in the Galan district and the Benchi Maji zone were income, meat and saving with index values of 0.42, 0.32 and 0.16 of, respectively. This indicates that in the mixed crop-livestock production system farmers mainly keep small ruminants as a source of income and meat. In contrast this in the pastoral and agro-pastoral systems (Alefe Citation2014; Belete Citation2013) in the Shebelle zone and Arsi-Bale zone reported that milk was the primary objective of farmers. This indicates that Ethiopian goats in the lowland are highly valued and reared mainly for milk and meat production, whereas in the highland part of the country kept mainly for cash income and meat production.

Table 4. The purpose of keeping goat.

None of the respondents ranked skin, manure and gift as the primary objectives of goat keeping in the study area, but as a byproduct traditionally skin was used as a sack for storage of different commodities locally known as ‘shilcha’, and as a mat in the house or locally known as ‘mintaf’. The present study was similar to the results of Hulunim (Citation2014) and FARM-Africa (Citation1996) in the Siti zone of the Somali region and phenotypic characterization of goats in Ethiopia and Eritrea which reported that the traditionally made goat skin was used as water containers locally known as ‘qerbid’, respectively. According to the respondents, besides producing different products, goats also provide manure to maintain soil fertility in mixed crop livestock and agro-pastoral production systems.

3.5. Husbandry practices of indigenous goats

3.5.1. Source of feed during dry and wet seasons

The availability of feed for goats in the study area depends on the season (). However, natural pasture and shrubs were the major feed sources of goats both in dry and wet seasons in all study districts. This implied that farmers in the study area did not produce improved fodder or forage and they are totally dependent on natural pasture due to the limited access of farmers for the development of cultivated forage due to small land holdings and agro-climatic factors. The study was in agreement with Belete (Citation2013), Ahmed (Citation2013), Biruh (Citation2013) and Hulunim (Citation2014) who reported that natural pasture was the major source of feed in the Bale zone, Horro Guduru Wollega zone and Bati, Borena and Siti zones, respectively. The common crop residue used as supplementary feed in Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora districts were chickpea, sorghum, maize, wheat and barley, while vetches, bean, pea, wheat and barley were common in the Basona-Worena district, respectively. In contrast Laouadi et al. (Citation2018) reported that the practice of feeding fodder crops was common (64.1% of farmers), with a predominance of wheat and barley fed and concentrate feeding is seldom practiced (8.49%).

Table 5. Source of feed during the dry and the wet season.

Almost all respondents in the study area reported severe seasonal shortage of feed mostly experienced in the dry season this was caused by the prevailing erratic rainfall patterns in the lowlands and lack of experience to preserve feed for the dry season feeding. During this period most farmers feed their goat leaves from trees, bushes, crop residues, local brewery by-products (‘Attela’ and ‘Brint’) and wheat bran or ‘furishika’ in Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora districts, while in the Basona-Worena district farmers also provide cereal crops in addition to the above mentioned. Salt supplementation was also a common practice; however, the amount of salt varies depending on the season. Even though farmers gave supplements for newly kidding does, sick goats recover and for the castrated buck to fatten they did not give them to healthy ones. Generally, awareness creation about effective feed management, cultivation of improved forage and conservation of feed resources are vital measures to solve feed shortages during the dry season.

3.5.2. Grazing practices

During the dry season, (81.9%) of goat owners in Berehet, 79.2% in Minjar-Shenkora and (67.7%) in the Basona-Worena district practiced free browsing/grazing (). Yemane et al. (Citation2020) reported that free grazing/browsing, riverside grazing/browsing, aftermath grazing and herding were the major grazing management types for goats in the dry season. In the wet season, 61.1% of goat owners in Berehet and 66.7% in Minjar-Shenkora herded their goats, while in Basona-Worena, 88.9% of goat owners herded their goats (). The reasons for a higher percentage of farmers herded in the wet season were to protect crops from damage and to prevent goats from predators. However, kids were separately kept around back yard until they are able to walk and browse properly. On the other hand, in the dry season most farmers practice free grazing/browsing as most of the land is free from crops.

Table 6. Grazing method practiced.

3.5.3. Herding practices of households

The main objectives of herding were to prevent goats from damaging crops, theft and predators (). Goat flocks in all districts were herded with sheep (25.0%), cattle (19.0%), equine (6.0%) and (13.9%) of goats were herded separately (). In contrast to this result Tariku et al. (Citation2021) and Shegaw et al. (Citation2021) reported that goats reared in the Aroresa district and South Western Ethiopia were herded separately from other livestock, respectively. Goat flock grazing separately from other livestock prevent the spread of many diseases across the livestock. Around (38.9%) of farmers in Berehet and (41.7%) in Minjar-Shenkora districts herded all species together, while in the Basona-Worena district, (36.1%) of farmers kept their goats with sheep. The majority of farmers in Berehet (61.1%) and in the Minjar-Shenkora district (65.3%) herded their goats together with neighbouring household’s goats but, the rest of the households herded their goat flock separately from other household flocks. The reason why they herded their goats together with neighbouring goats was the communal grazing land that they have, they also travel up to two hours to the grazing land locally called ‘bulsha’. Grazing goats with other goats (from the neighbours) can often lead to inbreeding within the flocks. In contrast in Basona-Worena districts most of the farmers (66.7%) did not mix their goats with other household goats because of that they did not have enough communal grazing land, whereas the remaining (33.3%) were mixing their goat flocks with adjacent households in the village.

Table 7. Way of goat herding practice.

3.5.4. Source of water and watering point for goats

More than half (58.3%) and nearly half (47.2%) of respondents in the study districts used the river as the major source of water for their goats (58.3%) in the dry and wet season, respectively (). Similarly, Tariku et al. (Citation2021); Yemane et al. (Citation2020) and Shewangzaw et al. (Citation2018) reported that rivers as the most important sources of water during dry and wet seasons (). In addition, Abraham et al. (Citation2017), Ahmed (Citation2013), Bekalu (Citation2014) and Hulunim (Citation2014) reported that rivers are the most important sources of water for goats, particularly during the dry season. In the Basona-Worena district, most (90.3%) of goat keepers used clean water for their goats, while only 68.1% and 73.6% of respondents in the Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora districts, respectively used clean water for their goats in the dry season. In the wet season, 79.2% of respondents in the Basona-Worena district used muddy water for their goats. In Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora districts, a relatively low proportion of respondents (59.7% and 70.8%, respectively) used muddy water for their goats in the wet season. During the rainy season rainwater and pond (muddy and smelly) water are used for the goats in Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora districts. However, there should be care to ensure that the water is clean and that the rainwater is not clean and contaminated Tariku et al. (Citation2021). During the dry season the forage usually lacks moisture and hence the animals need water quite frequently; it’s advisable that the goats be provided with water adlib. In addition, under dry conditions the animals are quite stressed and hence can influence their productive and reproduction capacity adversely.

Table 8. Source and quality of water for goats.

3.5.5. Housing of goat

The majority (80.6%) of respondents in the Basona-Worena district shared their family house with their goats due to the humid nature of the climate and the high presence of predator ‘hayna’ (). Similarly, Tariku et al. (Citation2021) reported that in most cases the goats were housed along with their owners’ houses in the Sidama zone. On the other hand, in the Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora districts 65.3% and 72.2% of respondents keep their goats in the paddock (traditionally called ‘gatta’) which is separate from the family house (). Yemane et al. (Citation2020) reported that the majority (66.2%) of farmers kept their goats in a separate house with a roof at night. In contrast, Shegaw et al. (Citation2021) reported that about 76.5% of the respondents across all studied areas reported that goats housed without other animals, while 22.8% reported that goats housed with other animals, especially housed with sheep (92.5%). and cattle (7.5%). However, housing goats separately can help to prevent the spread of zoonotic diseases. Respondents indicated why they used such types of houses in the two districts were fewer predators and the relatively hot climate and they assumed the goats’ reproduction rate is decreased if they are housed in roofed houses in the low land areas. As a result, most of the observed adult goats’ houses in Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora districts were not able to protect goats from predation, theft and climate extremes. In addition, most of the house floor is made up of mud which is difficult to clean and can spread parasites. The poor housing management practices of respondents could lead to low productivity. Therefore, the farmers should be aware of the role of an improved housing system to increase the productivity of goats.

Table 9. Type of house and housing material.

On the other hand, 72.7% of farmers across all districts reported that they did not house their goats together with other animals. This result agreed with the result of Alubel (Citation2015) who reported that the majority (70.0%) of respondents in the Ziquala, Tanqua and Abergelle districts did not house their goats with other animals. As per the report of the farmers in all the study districts, goat owners housed all sex and age groups of goats together except newborn kids. The report also agrees with the result of Ahmed (Citation2013) who reported that all sex and age groups of goats in Horro Guduru Wollega were housed together at night except newborn kids.

3.5.6. Castration and fattening practices of goats

About 81.0% of respondents practiced castration and it was primarily practiced to improve the fattening potential, to make the buck docile or to control mating to some extent and to acquire a better price by selling the fattened goats (). On contrary, Tariku et al. (Citation2021) reported that most of the respondents from the Aroresa district did not castrate their bucks. Most (91.4%) of farmers in the study area practiced castration by traditional method and the remaining (8.6%) of farmers used the modern castration method. In line with this result Shegaw et al. (Citation2021) reported that about 90.6% of the respondents practiced castration, while 9.4% reported that not castrated. Goats were castrated by selected farmers that use traditional material ‘allolo’ and modern burdizzo in all districts. On the contrary, Wondim and Teshager (Citation2022) reported that about two-thirds of respondents practiced the modern method of castration indicating that goat keepers in the study districts have access to local veterinary services. Almost all of the respondents in the study area castrated their goats between the age of 1 and 2 years and some of them castrated when they were above 2 years. In addition, in the study area farmers usually practiced castration at the end of the main rainy season (mainly in September and October) when there was high availability of good quality and quantity of natural pasture and the season they prefer as a better fattening time, especially in April and May.

Table 10. Castration practices of goats.

The type and number of goats to be fattened depends on the wealth status of the farmers. Across all districts all farmers used the same category of castrated goat for fattening purposes. In the study districts, 74.7% of the farmers were supplying their castrated goats with supplementary feeds such as grain, salt, local brewery by-products (‘Attela’ and ‘Brint’), food left over and concentrates like wheat bran to some extent. Bekalu (2016) reported that in Bahirdar Zuria 68.89% of the farmers were providing their goats with supplementary feeds such as wheat bran, Grain, salt and local brewery by-products (‘Attela’ and ‘Brint’) for about 1–2 weeks.

3.6. Rearing practices of goats in the study area

3.6.1. Sources of breeding bucks

Most (94.4%) in Berehet, 90.3% in Minjar-Shenkora and in Basona-Worena 79.2% of the respondents had their own local breeding buck (). Among the interviewed goat keepers 91.7%, in Berehet, 76.4% in Basona-Worena and 86.1% in Minjar-Shenkora districts used their own flock as a source of buck and the remaining respondents in each district purchased buck from the market. Almost all farmers reported that when the flocks did not have a breeding buck, they relied on bucks from village flocks to serve the female goats in all study districts. This result was in agreement with the report of Belete (Citation2013) and Alubel (Citation2015) who reported that 89% and 98.89% % of respondents had their own flock as the source of buck, respectively.

Table 11. Breeding buck sources.

The type of mating practiced was (100%) uncontrolled mating within the household’s flock and between neighbouring flocks. The main reasons for this uncontrolled mating were lack of awareness, insufficient bucks, communal watering points and browsing areas. Laouadi et al. (Citation2018) and Abraham et al. (Citation2017) reported that the majority of breeders (96.2%) apply a free mating system, holding bucks in the herd. The replacement animals are sourced either from own flock (40.0%), from outside (5.7%) or from both (54.3%). According to Kosgey (Citation2004), an advantage of natural uncontrolled mating is that it allows for all-year-round breeding. On the other hand, uncontrolled mating together with small flock sizes and poor/absent record keeping on the pedigree is expected to result in severe inbreeding which leads to poor growth rates. The current study was similar to the report of Mahilet (Citation2012) who reported that almost all of the respondents in Hararghe highland did not practice special management for the breeding buck.

In the study area, half (52.1%) of the goat owners kept bucks for fattening, 31.4% for mating and 16.5% for socio-cultural benefit. The majority of the respondents (73.1%) could not identify the sire of a kid, while some of them (26.9%) could identify only by the coat colours of kids. The reason was that identifying the sire of the kid was difficult because many different goat flocks of different households were grazed on communal grazing land and watered in communal watering points in the village. This study showed that goats were not milked in the study areas because none of the respondents reported who keep goats for milk. This is in agreement with the report of FARM Africa (Citation1996) and Tegegn et al. (Citation2016) that goats were not milked in parts of Gojam, Wollega, Keffa and Wolayta. However, reports by Girum (2010) for Short-Eared Somali Goats and (FARM Africa Citation1996) showed goats are milked in all other parts of the country except in high land and central highland parts of the country.

3.6.2. Selection criteria for breeding buck

Body size or appearance, growth rate, coat colour, pedigree, adaptability, libido and age were considered as buck selection criteria in all districts (). Among these traits growth rate, body size or appearance and coat colour were the first, second and third criteria in all study districts, respectively. In contrast to this result Alubel (Citation2015) reported that body conformation was the first selection criterion in the North Gonder zone on the central highland goat. In addition, Wondim and Teshager (Citation2022) reported that in the Abaya district selection criteria of breeding buck were conformation/appearance, colour (white and red), and growth rate of buck were ranked the first, second and third, respectively. This may be due to the difference in environment, objectives and the contribution of goats to the owners in their economy. Whereas in other areas Abraham et al. (Citation2017) reported that selection criteria for the buck were body size, growth rate and libido with the indices of 0.329, 0.232 and 0.183, respectively. Bucks that grow at a faster rate are the most preferred bucks by most of the farmers in all the study sites with red and fawn colour in the Basona-Worena district, while in Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora districts red, white and fawn red spotted with white coat colours were preferred, respectively. In the study area age is also a selection criterion by farmers, a buck that has milk teeth was mostly preferred by farmers for future breeding purposes.

Table 12. Selection criteria for breeding buck.

3.6.3. Selection criterion for breeding does

Across all districts litter size or twining ability, appearance and pedigree were ranked as the first, second and third for selection of breeding doe by goat owners, respectively (). Colour and fertility traits (kidding interval, kid survival and age at sexual maturity) were also mentioned as selection criteria, however, with lower ranking proportions. In contrast to this Tariku et al. (Citation2021) reported that appearance, coat colour and milk yield were the first, second and third selection criteria of breeding doe in the Sidama zone, respectively. This difference is due to agro-ecological and farmers’ socio-cultural practices in different areas. Tegegn et al. (Citation2016) and Ahmed (Citation2013) reported that the litre size was the most highly rated trait in selecting breeding females in the Bench Maji zone and Guduru districts, respectively. In contrast Wondim and Teshager (Citation2022) reported that conformation/appearance is the main criterion for the selection of doe in both districts. The most preferred coat colour of goats was fawn, white, red and red with white spotted coat colour patterns, in Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora districts, while in the Basona-Worena district red and fawn coat colours were preferred, respectively. The preference of farmers for a particular coat colour might be associated with socio-cultural practices, market demand, disease tolerance and environmental factors Zewdie (2008). Similar to Halima et al. (Citation2012) and Alubel (Citation2015) observation, black coat colour was not preferred by the owners in Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora, while in the Basona-Worena district black and white coat colours were not preferred by farmers, respectively. As a result goat keepers gave more weight to cash income generation (meat production/growth) this implies that designing a goat improvement strategy programme should be designed considering these differences accordingly.

Table 13. Selection criteria for breeding doe.

3.7. Major goat diseases

The major goat diseases were shoat pox, mange mite, Pasteurellosis, PPR (Pest des Petits Ruminants), CCPP (Contagious Caprine Pleuro Pneumonia), fasciolosis, diarrhea and anthrax existing health problems were identified and ranked by the respondents and translated to their veterinary equivalents with the support of animal health workers in the respective area (). Among these diseases, the most common disease affecting the goats and causing them for most losses in the Basona-Worena district was pasteurellosis followed by Fasciolosis and Diarrhea, whereas in the Berehet district pasteurellosis followed by PPR (peste des petitis ruminants) and shoat pox and in Minjar-Shenkora district pasteurellosis followed by PPR (pest des petits ruminants) and diarrhea were the most serious diseases as reported by farmers in the respective order. This indicated that the government should strengthen the veterinary service and be aware of the community in animal health improvement strategy interventions at area specific level. This study was similar to the report of Bekalu (Citation2014) in the West Gojam zone pasteurellosis and PPR were the most commonly affecting diseases of goats and causing the most losses. Similarly, Abraham et al. (Citation2017) reported that respondents indicated that diseases affect all age groups of goats and mortalities from the disease are high.

Table 14. Major goat diseases.

The great production loss caused by disease problems could be due to the climatic conditions of the study area, which might aggravate the prevalence of disease and poor nutrition for goats. Moreover, inadequate health management by farmers, less efficient veterinary service and frequent occurrence of drought in the study areas increased the problem. Most of the farmers were using modern drugs from government clinics and open markets. As the respondents stated that almost all farmers get government veterinary services in the study areas.

3.8. Major constraints of goat production

Feed shortage, disease and drought were the first, second and third goat production constraints across all districts (). Similarly, Hulunim (Citation2014) and Tegegn et al. (Citation2016) indicated that disease occurrences and drought were ranked the first, second and third and in the Benchi Maji zone feed shortage was ranked as the first, disease ranked the second frequently mentioned constraint, respectively. In contrast, Abraham et al. (Citation2017) reported that water shortage, feed and grazing land shortages and inadequate veterinary services were ranked first, second and third, respectively. On the other hand, Yemane et al. (Citation2020) reported that the three primary constraints of goat production were disease, feed shortage and lack of superior genotype with an index of 0.36, 0.258 and 0.201, respectively. Lack of superior genotype was also reported as a constraint, especially in the Basona-Worena district, the farmers prefer goat breeds that can adapt to highland climatic conditions. Improved rangeland management can be one alternative to minimize feed shortage by resorting to and increasing the productivity of degraded land grazing/browsing areas.

Table 15. The major goat production constraints.

4. Conclusion

Goat production is an important component of farming activity in the study areas by providing multifunctional roles to smallholder farmers. However, it is characterized by low-input subsistence and multiple production objectives in marginal environments. Relatively higher flock size was found in the Berehet and Minjar-Shenkora districts than in the Basona-Worena district. The existing feed situation in each area limits the size and the contribution of goats to the livelihood of the community. In spite of the high economic role, goat production is constrained by lack of feed, disease, lack of labour, drought, predator and lack of superior genotype. The majority of farmers were illiterate and it has a negative impact on management practices for feeding, housing, herding, castration and breeding of goats. As a result, the performances of goat productivity decreased. The breeding practice of goats was uncontrolled and it has an important factor in the growth performance of goats and leads to inbreeding problems. Goat keepers in the study area gave more emphasis to economically important traits growth and twining rate than conformational or qualitative traits this is important in the improvement intervention programme.

4.1. Recommendations

➢ To efficiently utilize these special features of indigenous breeds, there is a need for planning and implementing viable breeding programmes that fit the existing low-input production systems and environment.

➢ In the mixed crop-livestock production system, where the generation of cash income through increased commercial goat production is the prominent farmers’ priority so, improving reproductive performances to increase the number of marketable goats should be targeted.

➢ To prevent uncontrolled natural mating and to increase productivity, establishing buck selection strategy and management systems at the community level and castrating non-productive bucks should be implemented.

➢ The research institute and extension workers should work together with the community in a genetic improvement programme to avoid an inbreeding problem and unwanted bucks mating their does.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets used to support that the finding of the present study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abraham H, Gizaw S, Urge M. 2017. Begait goat production systems and breeding practices in Western Tigray, North Ethiopia. Open J Anim Sci. 07:198–212. doi:10.4236/ojas.2017.72016

- Adane H, Girma A. 2008. Economic significance of sheep and goat. In: Alemu Y, Merkel RC, editors. Sheep and goat production handbook for Ethiopia. Ethiopian sheep and goat productivity improvement program, USAID; p. 1–4.

- Ahmed S. 2013. On-farm phenotypic and production system Characterization of indigenous goats in Horro Guduru Wollega Zone, Western Ethiopia [MSc Thesis]. Haramaya, university; p. 112.

- Ahmed S, Kebede K, Effa K, Kirmani MA. 2013. Assessment on management practice of goat owners and reproductive performance of indigenous goats in Horro Guduru Wollega Zone, Western Ethiopia [MSc Thesis]. Haramaya University, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia.

- Alefe, T. 2014. Phenotypic characterization of indigenous goat types and their production system in Shabelle Zone, South Eastern Ethiopia [MSc Thesis]. Haramaya University; p. 130.

- Alemayehu N. 1993. Characterization (phenotypic) of indigenous goats and goat husbandry practices in East and South-eastern Ethiopia [MSc Thesis]. Presented to the School of Graduate Studies of Alemaya University of Agriculture; p. 135.

- Alubel, A. 2015. On-farm phenotypic characterization and performance evaluation of Abergelle and central highland goat breeds as an input for designing community-based breeding program [MSc Thesis]. Haramaya university; p. 147.

- Ameha S. 2008. Sheep and Goat Meat Characteristics and Quality. In: A. Yami, R. C. Merkel, editors. Sheep and Goat Production Handbook for Ethiopia. Ethiopian Sheep and Goats Productivity Improvement Program (ESGPIP). Addis Ababa: USAID; p. 323–328.

- Baenyi SP, Junga JO, Tiambo CK, Birindwa AB, Karume K, Tarekegn GM, Ochieng JW. 2020. Production systems, genetic diversity and genes associated with prolificacy and milk production in indigenous goats of Sub-Saharan Africa: a review. Open J Anim Sci. 10:735–749. doi:10.4236/ojas.2020.104048

- Bekalu Muluneh. 2014. Phenotypic characterization of indigenous goat types and their production system in West Gojam Zone of Amhara Region, Ethiopia [MSc Thesis]. Haramaya university; p. 109.

- Belete A. 2013. On farm phenotypic characterization of indigenous goat types and their production system in bale zone of Oromia region, Ethiopia [MSc Thesis]. Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Through School of Range Science and Animal Science; p. 116.

- Biruh T. 2013. Phenotypic and production system characterization of Woyto Guji Goats in Lowland areas of South Omo Zone [MSc thesis]. Submitted to School of Animal and Range Science, School of Graduate Studies Haramaya University; p. 89.

- Cochran WG. 1977. Sampling techniques. 3rd ed. John Wiley and Sons.

- CSA. 2012. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Agricultural sample survey 2011/2012 (2004 E.C.) Report on crop and livestock product utilization (private peasant holdings, meher Season) No. 532, Vol.3, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- FARM Africa. 1996. Goat types of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Physical description and management systems. Nairobi, Kenya: Published jointly by FARM-Africa, London, UK, and ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute); p. 76.

- Feki M. 2013. Community-Based Characterization of Afar Goats Breeds in Aysaita District of Afar Region. MSc thesis submitted to School of Animal and Range Science, School of Graduate Studies Haramaya University. 129pp.

- Fredu N, Mathij E, Decker J, Tollen E. 2009. Rural livestock asset portfolio in northern Ethiopia: A microeconomic analysis of choice and accumulation. Contributed Paper prepared for presentation at the International Association of Agricultural Economists Conference, August 16-22, 2009, Beijing, China.

- Galal ESE, Metawi HRM, Aboul-Naga AM, Abdel-Aziz. 1996. Performance of and factors affecting the smallholder sheep production system in Egypt. Small Rumin. Res. 19:97–102.

- Getinet M. 2016. Molecular characterization of Ethiopian indigenous goat populations: genetic diversity and structure, demographic dynamics and assessment of the kisspeptin gene polymorphism Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Applied Genetics Addis Ababa University. 274p.

- Halima H, Michael B, Barbara R, Markos T. 2012. Phenotypic characterization of Ethiopian indigenous goat populations. Afr J Biotechnol. 11(73):13838–13846.

- Hulunim G. 2014. On-farm phenotypic characterization and performance evaluation of Bati, Borena and Short Eared Somali Goat Populations of Ethiopia. MSc thesis, Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Haramaya University, Ethiopia. 140p.

- ILCA. 1990. (International livestock centre for Africa). Livestock research Manual systemmanual. ILCA, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Part I. 287p.

- Kosgey IS. 2004. Breeding objectives and breeding strategies for small ruminants in the tropics. Ph.D. Thesis. Wageningen University, the Netherlands.

- Laouadi M, Tennah S, Kafidi N, Antoine-Moussiaux N, Moula N. 2018. A basic characterization of small-holders’ goat production systems in Laghouat area, Algeria. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-018-0131-7.

- Mahilet D. 2012. Live characterization of Hararghe highland goat and their production system in eastern Hararghe. M.Sc. thesis presented to School of Graduate Study of Haramaya University..

- Mahmoud Abdel Aziz. 2010. Present status of the world goat populations and their productivity. Lohmann Information 45 (2): 42.

- Markos T. 2006. Productivity and Health of Indigenous Sheep Breeds and Crossbreds in the Central Ethiopia Highlands [PhD dissertation]. Uppsala: Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences, Swedish University of Agricultural Science(SLU), 74 p.

- Nigatu A. 1994. Characterization of indigenous goat types & husbandry practices in Southern Ethiopia MSc. Thesis, Alemaya University of Agriculture. Alemaya, Ethiopia..

- Peacock C. 2005. Improving goat production in the Tropics. A manual for development work. Oxfam: Farm Africa.

- Shegaw A, Elias B, Dessalegn G. 2021. Indigenous Goat Husbandry Practices and Its Production Environment in Case of South Western Ethiopia. American Journal of Zoology. 4(1):1–8. doi:10.11648/j.ajz.20210401.11.

- Shewangzaw A, Aschalew A, Addis G, Malede B, Assemu T. 2018. Small ruminant fattening practices in Amhara region, Ethiopia. Agriculture & Food Security. 7(1). http://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-018-0218-9.

- Skapetas B, Bampidis V. 2016. Goat production in the World: present situation and trends. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 28, Article #200. Retrieved September 23, 2022, from http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd28/11/skap28200.html.

- Solomon A. 2014. Design of Community Based Breeding Programs for Two Indigenous Goat Breeds of Ethiopia [PhD desertation]. BOKU-University of Natural Resources and Life sciences, Department of Sustainable Agricultural Systems, Division of Livestock Sciences, Vienna, Austria, p. 100.

- Solomon G, Tegegne A, Gebremedhin B, Hoekstra D. 2010. Sheep and goat production and marketing systems in Ethiopia: Characteristics and strategies for improvement. Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, working paper 23. International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.61p.

- Tariku W, Hankamo A, Banerjee S. 2021, June 28. Traditional Husbandry Practices of Goats in Selected Districts of Sidama Zone, Southern Ethiopia. PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square.

- Tegegn F, Kefyalew A, Solomon A. 2016. Characterization of goat production systems and trait preferences of goat keepers in Bench Maji zone, south western Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research. 11(30):2768–2774.

- Tesfaye A. 2004. Genetic Characterization of Indigenous Goat Populations of Ethiopia Using Microsatellite DNA markers [PHD thesis]. National Dairy Institute, Haryana, India, 188 p.

- Tsedeke K. 2007. Production and Marketing of Sheep and Goats in Alaba, SNNPR [Msc thesis]. Hawassa: Hawassa University.

- Tsegaye T. 2009. Characterization of goat production systems and on- farm evaluation of the growth performance of grazing goats supplemented with different protein sources in Metema, Amhara Region, Ethiopia [MSc Thesis]. Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Haramaya University, Ethiopia, p. 108.

- Tsigabu G. 2015. Phenotypic characterization of indigenous goat types and their production system in Gambella region Ethiopia. MSc. Thesis, Haramaya university.93p

- Wondim A, Teshager M. 2022. Indigenous goat selection and breeding practices in pastoral areas of West Guji zone, Southern Oromia. Theriogenology, Genetics and Breeding. 10(1):33–41.

- Workneh A, Rowlands J. 2004. Design, excuetion and analysis of livestock breed survey in Oromia Regional state, Ethiopia. OADB (Oromia Agricultural Development Bureau), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and ELRI, Nairobi, Kenya.260pp .

- Workneh Ayalew. 1992. Preliminary Survey of Indigenous Goat Types and Goat Husbandry Practices in Southern Ethiopia [M.Sc. Thesis]. Alemaya University of Agriculture. Alemaya, Ethiopia, 156 p.

- Yemane G, Melesse A, Taye M. 2020. Evaluation of production systems and husbandry practices of Ethiopian indigenous goats. Online J Anim Feed Res. 10(6):268–277. https://doi.org/10.51227/ojafr.2020.36.

- Zewdu E. 2008. Characterization of Bonga and Horro indigenous sheep breeds of smallholders for designing community based breeding strategies in Ethiopia. MSc. thesis submitted to the department of animal science, school of graduate studies, Haramaya University, 33 p.