ABSTRACT

In this paper, we describe for the first time a finding of fetal maceration in a wild Iberian hind (Cervus elaphus hispanicus, Erxleben, 1777). Fetal maceration seems to occur in fetuses that have died and have not been expelled due to insufficient dilation of the cervix, but which allows the penetration and ascent of germs through the birth canal. It can occur at any stage of gestation, although it is more common in mid to late gestation. In our case, the stage of development and skeleton ossification and the degree of eruption of the premolar teeth of the mandible allow us to infer that the death of the fetus and the process of maceration occurred from the end of gestation. This discovery occurred during the butchering of a female hunted as part of the management programme to reduce the abundance of the population in Quintos de Mora, Spain. Although the female was in good body condition, she was selected because she had no calf and had an aged appearance. We describe the case in detail and draw attention to the interest of recording the rates of pregnancy losses and abortions in studies of fitness and population dynamics in wildlife.

Introduction

Many of the pathological conditions that are easily identifiable in domestic livestock at routine check-ups often go unnoticed in wild animals. This is especially true for reproductive disorders such as foetal loss, including foetal maceration. They have been described in a wide variety of domestic species (Purohit Citation2012) such as cows (Krishna and Rao Citation2011), goats (Mehta et al. Citation2005; Ajitkumar et al. Citation2007; Rautela et al. Citation2016), sheep (Senthilkumar et al. Citation2022) and dogs (Bozkurt et al. Citation2018; Begum et al. Citation2019; Ece and Çelik Citation2021). Also in captive-bred buffaloes (Sood et al. Citation2009); but they are not commonly described in wildlife. Fetal maceration involves fetal death with retention of the fetus in utero indefinitely. It can occur at any stage of gestation (Purohit Citation2012), although it is most common in mid to late gestation (Roberts Citation2004). Fetal maceration differs from mummification in that in mummification the fetal membranes shrivel and dry, the allantois, amnion and fetal fluids are reabsorbed, and the uterus contracts over the fetus and moulds it into a dry, contorted mass (Noakes et al. Citation2009) whereas in maceration the tissues are resorbed due to a combination of putrefaction and autolysis (Selvaraju et al. Citation2020) in which the soft parts disintegrate leaving only the bones (Drost Citation2007; López Citation2017). Incomplete abortion after the third month of gestation may involve a retention process and result in fetal mummification or fetal maceration. Fetal maceration, which the exact etiology is not known, is the disintegration of a fetus that has died and could not be aborted due to lack of cervical dilatation (Dalal et al. Citation2018). The fetus has not been expelled but germs ascend through the birth canal, facilitating the process (Bhattacharyya et al. Citation2015). Termination of gestation with foetal disorders is not very frequent in large and small ruminants (Purohit and Gaur Citation2011). Fetal maceration may occur at any stage of gestation (Dalal et al. Citation2018), and fetal maceration occurring after the third month of gestation in cows has shown well-developed fetal bones (Hailat et al. Citation1996). The consequences of these abortive processes are that future fertility is always in doubt (Noakes et al. Citation2001) since the longer the process lasts, the greater the damage to the endometrium and the worse the prognosis (Bhattacharyya et al. Citation2015). Other consequences caused by this process are the economic losses that occur in the livestock sector by increasing the time between calvings and obtaining fewer calves per cow (Azizunnesa et al. Citation2010).

In this paper, we describe for the first time the occurrence of a case of foetal maceration in a free-ranging female Iberian deer (Cervus elaphus hispanicus Erxleben, 1777). We discuss the importance of recording these cases in wildlife monitoring. These rates have implications for fecundity, fertility and population dynamics.

Case report

The case presented below is that of a female that harvested on 24 January 2017 as part of a population size reduction effort on hunting season from October 2016 to February 2017, in which the females selected are primarily those that are not accompanied by calf, i.e. those that have not given birth that season. This particular female was selected because although she was in a good body condition, she was alone and without calf and her appearance was one of advanced age. She belongs to the Quintos de Mora National Reserve, central Spain (39°25′08″N 4°03′36″W) located in the mesomediterranean bioclimatic floor with dry-subhumid ombroclimate (Gómez-Manzaneque Citation1988).

From the external examination carried out as a standardized protocol of body condition score (Audige et al. Citation1998) a good body condition was established. The total weight of the animal was 79.8 kg, and white hair and the appearance of an adult-old animal were observed.

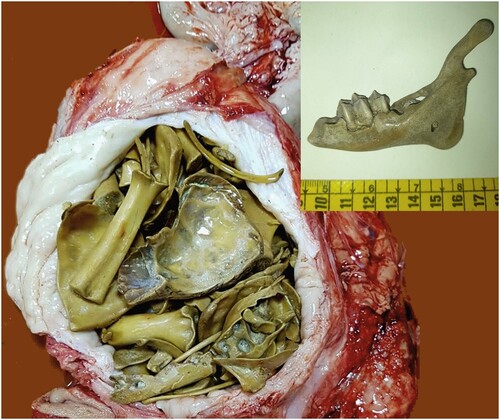

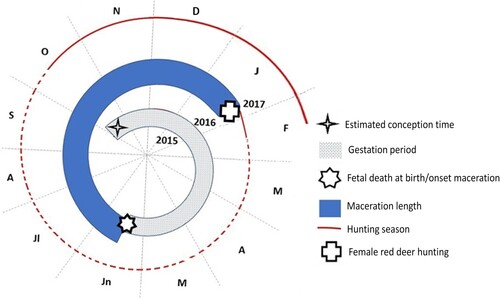

The external genitalia were classified as normal, without discharge or bad odour, and eviscerated for internal examination. When the uterus was removed to verify the presence of the fetus, it was not of a normal consistency and an incision was made and fetal bones were found within the uterus with no fluid in the uterus (see ). A regressing corpus luteum was found in the ovaries. The hind was 11 years old, age determined through growth marks on the teeth (Azorit et al. Citation2004; Azorit Citation2011). shows the chronology of the process, allows us to infer that the maceration process occurred at the end of gestation.

Discussion

When the embryo dies, in maceration process, there is a purulent discharge without expulsion resulting in emphysema within 24–48 h and maceration begins in three to four days (Singh et al. Citation2019). The uterine wall thickens and the cervix enlarges and hardens (Vinha Citation1981). In the case of our hind, the uterine wall was very thickened and whitish in colour and could be said to be a case of chronic inflammation. The pregnancy reached full term, but the fetus could not be born or was aborted and from its stage of development, the total ossification of the fetal skeleton and the degree of eruption of the premolars of the mandible, specifically, the third premolar is observed fully formed with its three cusps (see ), allow us to infer that the maceration process occurred at the end of gestation. It follows, therefore, that the hind retained the fetus in her uterus for more than 15 months, and in maceration status for 7 months, from the estimated time of fetal death at parturition in June 2016 (average parturition date 1 June 2016) until January 2017, when she was hunted (see ). Future fertility after these processes is always in doubt (Noakes et al. Citation2001), as the longer the process lasts, the greater the damage to the endometrium and the worse the prognosis (Bhattacharyya et al. Citation2015). In the case of the hind studied, the uterus was compacted and occupied by the bony remains of the macerated fetus, so this female could no longer have become pregnant or gestated new offspring. It seems that she would not have been able to naturally expel the fetal remains either. Contrary to what has been described in similar cases (England Citation1998; Rashidat et al. Citation2011), our hind was in good body condition. This means that she had already overcome the process, that she had made the fetus a part of herself and that she presented absence of symptoms. A regressing corpus luteum was found in the ovaries as in other similar cases (Arthur et al. Citation1989). The most interesting thing about this case is that after overcoming the maceration process, the hind returned to a good physical condition but with its reproductive capacity annulled.

Taking into account all the adult hinds analysed at the Quintos de Mora Center from the 1990s to the present, this case is the only one detected among 2743 necropsies performed, and if we were to take into account only the hinds of that season (2016–2017) this case accounts for 1 of the 73 hinds hunted. Fetal maceration is one more of the casuistry showing fetal loss in the study area. Although infrequent, there are occasions in which the delivery is complicated and both the fetus and the mother die (1 case found on 27 June 2023), others in which there is only evidence of fetal death (1 case observed through photo-trapping cameras) and others in which only the mother is known to have died (1 case on 27 June 2023). It is not known if the abortion was caused by trauma, by the advanced age of the hind or by an infectious process of Brucellosis. It was not possible to perform laboratory tests to determine a possible predisposing infectious affectation of the process, or abortion.

Although only one case of fetal maceration has been described in the area, it suggests that this fetal loss occurs in hinds and leaves the way open to examine its incidence in wild populations and reproductive rates and its impact on population dynamics. Even if it is as small as the one detected in cows the probability of occurrence should be considered among other factors of fertility decline. This finding encourages future systematic case-recording studies. Furthermore, distinguishing among a variety of agents involved in pregnancy loss could serve to increase our knowledge of population fitness. Similarly, more specific information on female reproductive senescence and age-related fertility or fecundity decline in an ecosystem is of great interest for population wildlife management.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data used is available and can be provided upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajitkumar G, Kuriakose AM, Ghosh KNA, Sreekumaran T. 2007. Fetal maceration in a goat. Indian J Anim Reprod. 28:107–108.

- Arthur GH, Noakes DE, Pearson H. 1989. Veterinary reproduction and obstetrics, 6th ed. London: Baillier Tindall.

- Audige L, Wilson PR, Morris RS. 1998. A body condition score system and its use for farmed red deer hinds. N Z J Agric Res. 41:545–553. doi:10.1080/00288233.1998.9513337.

- Azizunnesa SB, Das BC, Hossain MF, Faruk MO. 2010. A case study on mummified fetus in a heifer. Univ J Zool Rajshahi Univ. 28:61–63. doi:10.3329/ujzru.v28i0.5289.

- Azorit C. 2011. Guía para la determinación de la edad del ciervo ibérico (Cervus elaphus hispanicus) a través de su dentición: revisión metodológica y técnicas de elección. Anales Real Academia Ciencias Veterinarias Andalucía Oriental. 24:235–264.

- Azorit C, Muñoz-Cobo J, Hervás J, Analla M. 2004. Aging through growth marks in teeth of Spanish red deer. Wildl Soc Bull. 32(3):702–710. doi:10.2193/0091-7648(2004)032[0702:ATGMIT]2.0.CO;2.

- Begum MM, Roshini ST, Bhuvaneshwari V. 2019. Management of fetal maceration in a 2-year-old Toy Poodle. Indian Vet J. 6(6):57–58.

- Bhattacharyya HK, Dar SA, Fazili MR. 2015. Fetal maceration in crossbred Holstein Frisian heifer – a case report. Int J Vet Sci. 1(1):1–4.

- Bozkurt G, Sidekli O, Aksoy G, Cortu A, Agaoglu AR. 2018. The case of fetal maceration in two different bitches. J Vet Sci Ani Husb. 6(1):104. doi:10.15744/2348-9790.6.104.

- Dalal J, Singh G, Dutt R, Patil SS, Gahalot SC, Yadav V, Sharma K. 2018. Delivery of macerated and reabsorbed fetus through flank approach – a case report. Explor Anim Med Res. 8(2):222–224.

- Drost M. 2007. Complications during gestation in the cow. Theriogenology. 68(3):487–491. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2007.04.023.

- Ece T, Çelik HA. 2021. Case of fetal maceration in a dog. Kocatepe Vet J. 14(1):166–170.

- England GCW. 1998. Ultrasonographic assessment of abnormal pregnancy. Vet Clin: Small Anim Pract. 28(4):849–868. doi:10.1016/S0195-5616(98)50081-2.

- Gómez-Manzaneque F. 1988. Algunos taxones interesantes del suroeste madrileño. Stu Bot. 7:257–261.

- Hailat N, Lafi S, Al-Sahli A, Abu-Basha E, Fathalla M. 1996. Twin fetal maceration in a cow associated with persistent corpus luteum and closed cervix. Bov Pract. 30:83–84. doi:10.21423/bovine-vol1996no30p83-84.

- Krishna KM, Rao BS. 2011. Foetal maceration in a cow. Indian Vet J. 88(6):64–65.

- López J. 2017. Maceración fetal. R Vet. www.reproduccionveterinaria.com.

- Mehta V, Sharma MK, Bhatt L. 2005. Macerated fetus in goat. Indian J Anim Reprod. 26:75–76.

- Noakes DE, Parkinson DJ, England GCW. 2009. Abnormalities of development of conceptus and its consequences. Veterinary reproduction and obstetrics (9th ed.). Filadelfia: Saunders Harcourt.

- Noakes DE, Parkinson TJ, England GCW. 2001. Abnormal development of the conceptus and its consequences. In: Noakes D.E., editor. Arthur’s veterinary reproduction and obstetrics. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; p. 138.

- Purohit GN. 2012. Domestic animal obstetrics. 632., Germany: Eds Purohit GN, Lambert Academic Publishers.

- Purohit GN, Gaur M. 2011. Etiology, antenatal diagnosis and therapy of fetal complications of gestation in large and small domestic ruminants. Theriogenology Insight – An Int J Reprod Anim. 1(1):43–62.

- Rashidat M, Nenshi PM, Ate IU, Bello A, Allam L. 2011. Foetal maceration associated with Brucella ovis infection in a Yankassa ewe. . REDVET Electron J Vet Med. 12(3):1–6.

- Rautela R, Yadav DK, Katiyar R, Singh SK, Das GK, Kumar H. 2016. Fetal maceration in goat: a case report. Int J Sci Environ Technol. 5:2323–2326.

- Roberts SJ. 2004. Veterinary obstetrics and genital diseases. Theriogenology, Indian reprint, 2nd ed. New Delhi: CBS Publishers and Distributors.

- Selvaraju M, Prakash S, Varudharajan V, Ravikumar K, Palanisamy M, Gopikrishnan D, Manokaran S. 2020. Obstetrical disorders in farm animals: A review. J Pharm Innov. 9(9):65–74.

- Senthilkumar K, Periyannan M, Manokaran S, Selvaraju M, Aadhithya Muthuswamy J, Palanisamy M, Gopikrishnan D. 2022. A case report of foetal maceration due to uterine torsion in a Mecheri sheep. J Pharm Innov. 11(1):904–905.

- Singh G, Dutt R, Kumar S, Kumari S, Chandolia RK. 2019. Gynaecological problems in she dogs. Haryana Vet. 58:8–15.

- Sood P, Vasishta NK, Singh M. 2009. Use of novel approach to manage macerated fetus in a crossbred cow. Vet Record. 165:347–348. doi:10.1136/vr.165.12.347.

- Vinha NA. 1981. Fisiopatología uterina en la vaca. Veterinaria (Montevideo). 17(75):13–16.