Abstract

New agricultural technologies such as improved maize varieties (IMVs) promise important benefits – increased incomes, lower workloads, and better food security – among others. When such technologies are introduced, they can denaturalize and expose gender norms and power relations because the adoption of such technologies inevitably requires women and men to renegotiate the rules of the game. This article asks: How do women negotiate power relations and their expression in gender norms to secure benefits from improved maize varieties (IMVs), and more broadly, to expand their decision-making space? We draw on data from four Nigerian case-studies, two from the North and two from the Southwest. The findings are analyzed through a conceptual framework utilizing five different concepts of power. Findings are remarkably similar across all sites. Women are constrained by powerful gender norms which privilege men's agency and which frown upon women's empowerment. There is limited evidence for change in some contexts through expansion in women's agency. The implications for maize research and development is that an improved understanding of the complex relational nature of empowerment is essential when introducing new agricultural technologies.

Introduction

Deep-seated gender norms – expectations governing women’s and men’s behaviors – create important differences in the ability of women, men, and young women and men to learn about, try out, adapt, and benefit from new agricultural technologies and practices (Petesch et al., Citation2017). The ability of women to participate effectively in agricultural innovation processes often demands that norms change in order to facilitate women's ability to set goals and act upon them. This is an interactive process whereby women (can) become ever more able to express their agency and force change in norms, and this change in norms allows further expansion in women's capacity. Fundamentally, normative change is about shifts in power relations. While normative change occurs globally and at all levels down to local, the shifts in power relations that herald normative change can be experienced as liberating – or as deeply threatening.

Developing an understanding of the relationship between gender norms, women's ability and willingness to express their agency, and the uptake of agricultural technologies, is an important step toward improving the capacity of agricultural research for development (AR4D) to design and scale innovations (ibid.). Achieving this ambition is highly relevant to maize. Maize is the most important food crop in sub-Saharan Africa and is widely consumed in Nigeria (Gaya et al., Citation2017). Average yield in Nigeria is around a quarter of the global average and well below a number of other sub-Saharan African countries (Oyinbo et al., Citation2018). Improved maize varieties (IMVs) include traits offering resilience to drought, disease, pests, improved higher nitrogen use efficiency, cookability, and higher yields, among others. Abdoulaye et al. (Citation2018) conducted a study utilizing nationally representative plot, and household-level data from major maize-producing regions of Nigeria, to assess the impacts of adoption of IMVs on maize yield and household economic welfare outcomes. This showed that adoption of IMVs typically increased maize grain yield by 574 kg/ha. The ability of both women and men to obtain benefits from IMVs has important implications for poverty alleviation and food security.

This article discusses data from Nigeria in four maize-based farming systems, two in the South and two in the North, to develop a rich understanding of the interactions between gender norms, agency, and the ability of women and men to benefit from IMVs. IMVs have been introduced over the past five to 10 years in each community and were widely perceived by respondents to be one of the most significant agricultural innovations they had experienced. Data were obtained as part of the global GENNOVATE (Enabling Gender Equality in Agricultural and Environmental Innovation) research initiative. GENNOVATE applies a comparative case study approach deploying standardized instruments to identify factors which hinder, facilitate and promote men and women's individual and collective capacities for engaging in agricultural innovation processes (Petesch et al., Citation2018).

New technologies such as IMVs promise important benefits – increased incomes, lower workloads, and better food security among others. As such they can denaturalize and expose gender norms and power relations because the adoption of such technologies inevitably requires women and men to renegotiate the rules of the game. A host of decisions need to be made – for example labor may be re-allocated, inorganic fertilizers purchased, crops may be switched between women- and men-managed plots, and the types of benefit household members expect to secure may change (Farnworth et al., Citation2017; Mutenje et al., Citation2019; Theriault et al., Citation2017). This article discusses gendered perceptions of benefits from IMVs; the focus is on the power relations that facilitate, or hinder, realization of those benefits, rather than the benefits themselves.

The article is structured as follows. We open with a conceptual framework to help us analyze and interpret fieldwork data. We then present our research design, followed by findings. The discussion and conclusion reflect on our conceptual framework, the data, and lessons learned.

Conceptual Framework

Cornwall (Citation2016) remarks that women's empowerment has now become a mainstream development concern. It has largely lost its feminist transformational roots, which in the halcyon days in the 1980s and 1990s focused on redressing ‘power inequalities, asserting the right to have rights, and acting … to bring about structural change in favor of equality’ (ibid. p. 343). Robbed of its radical character, empowerment is – she claims – now frequently treated as akin to a destination reached through the development sector's equivalent of motorways. Cornwall argues against reducing dimensions of women's experience to measurable indicators and instrumental understandings of empowerment. These tend, she argues, to focus more on what empowered women can do for achieving desirable development goals rather than on building an understanding of empowerment as desirable in itself. To understand what this means it is useful to reflect on Kant (Citation1983, originally 1785) who postulated: ‘Now I say that man … exists as an end in himself, not merely as a means for arbitrary use by this or that will: he must in all his actions, whether they are directed toward himself or to other rational beings, always be viewed at the same time as an end … Rational beings are called persons because their nature already marks them out as ends in themselves … (and as an object of reverence).’ Bearing in mind the necessity to treat people as ends in themselves and as objects of reverence, our purpose is to develop insights into the power relations that facilitate or hinder women's ability to realize benefits they value from improved maize and more broadly to examine their decision-making space. In particular, we are interested in ‘seeing’ evidence for empowerment processes in play. To help us do this, our framework draws on a widely accepted definition of agency, and applies five different enactments of power relations to help us interpret the findings. These are power within, power with, power to act, power over, and a new concept (Galié and Farnworth, Citation2019) power through.

Concepts of power

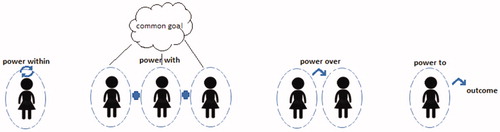

Sen (Citation1997, p. 2) argues ‘empowerment is, first and foremost, about power; changing power relations in favor of those who previously exercised little power over their own lives.’ Rowlands (Citation1997) points out that talking about power as process has strong implications for how we understand empowerment, and brings together and consolidates various definitions of power. We use them in this paper to help us interpret our data:

Power within is a transformation of individual consciousness which leads to a new self-confidence to act.

Power with is power that results from individuals organizing and acting collectively to address common concerns.

Rowlands defines power to as the ability to bring about an outcome, or to resist change. It creates new possibilities without dominating or subordinating anyone. Allen (Citation1999) instrumentalizes this concept as power to act in order to achieve a desired outcome. We use this revised sense in this article, as we are specifically interested in knowing whether individual, nonorganized women are able to secure benefits from improved maize through their own actions.

Power over refers to controlling power and suggests a relation of domination or subordination between individuals (Pansardi, Citation2012). It can be responded to with compliance or resistance.

These definitions of power are interactive. A sense of power within facilitates the ability to take part in collective action (and power within can be iteratively strengthened through power with). These definitions of empowerment share a conceptualization of power which seems to consider power as something like a ‘property’ which can be ‘owned' by an individual ('I am empowered') (Galié and Farnworth, Citation2019). visualizes these definitions of power. Each pictogram suggests that there is an empowerment boundary which is intrinsically associated with individuals. At the same time, the definitions recognize that an individual empowerment boundary is capable of expanding to accommodate an increase in personal empowerment (ibid.).

Figure 1. Representation of four definitions of power. Source. Galié and Farnworth, Citation2019.

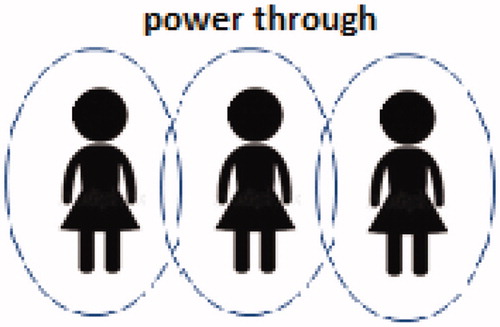

Power through is a new concept (Galié & Farnworth, Citation2019). It is already understood that power can have normative dimensions which allow it to exist and be exercised in the absence of any apparent agency (e.g., through the workings of cultural norms). However, power through adds a new dimension. The concept suggests that individuals can win, or lose, their empowerment status through changes in the empowerment status of people in significant relationships (partners, siblings, parents, etc.) to them. For this reason, individual empowerment boundaries merge with those of significant others ().

Figure 2. Representation of power through. Source. Galié and Farnworth, Citation2019.

The critical issue is the way in which a change in a person's individual empowerment status is perceived by the community to affect those significant relationships. In particular, community perceptions of whether women and men are continuing to perform gender in ways which conform to locally accepted gender norms seem key. Galié and Farnworth cite case studies of women becoming economically empowered through various development initiatives. However, over a short period of time many of these women experienced economic and social disempowerment. The wider community rejected the idea that women could earn significant monies as this was considered to disempower men. Being the wife of a disempowered man – and being a ‘bad wife’ because she had disempowered him through earning more than him – led to women being disempowered too.

The concept helps to explain why women's economic empowerment initiatives are so often interpreted, particularly by men, as a zero-sum game. However, the converse is not necessarily true: community members may consider that women have been positively empowered through an improvement in their husband's empowerment status – whether or not the woman is actually able to experience improved agency as a consequence of her husband's empowerment. Power through lifts the processes of power away from the workings of individual agency by capturing an involuntary aspect of empowerment and disempowerment processes. Throughout this process, the concept of power through allows the experience of empowerment and disempowerment to remain distinctive and personal to an individual: it is not abstract.

Concepts of agency

Kabeer (Citation1999) argues that empowerment intrinsically involves processes by which people who have been denied the ability to make choices acquire such an ability. Defining – and realizing – one's aspirations is critical if one is to be able to live a good life, one in which women and men are able ‘to imagine, to wonder and … to know’ (Nussbaum & Sen, Citation1993, pp. 1–2). We – the authors of this article – are fundamentally interested in understanding empowerment as a process toward enhanced self-understanding, which in turn facilitates the ability of individuals to make choices which matter to them. This entails a journey toward people perceiving themselves as ‘able and entitled [our emphasis] to occupy … decision-making space’ (Sen, Citation1997, 87).

Kabeer (Citation1999) considers that the ability to exercise choice can be thought of in terms of three inter-related dimensions: Resources (preconditions) → Agency (process) → Achievements (outcomes). Resources, including material, human and social resources, underpin the ability to make meaningful choices. Agency is the ability to define one’s goals and – critically – to act upon them. Achievements refers to evidence that empowerment has actually happened (ibid.). Farnworth et al. (Citation2020) generally agree with this definition, however, they contest the uni-directionality of Kabeer's schema. Enhanced agency can equally be a mechanism for securing resources. They conclude that Kabeer's three dimensions are better conceptualized as multi-directional and iterative. Furthermore, it is helpful to reflect that agency can be articulated through decision-making, bargaining and negotiation, deception and manipulation, subversion and resistance (Kabeer, Citation1999). As a consequence of this complexity, the workings of agency can be extremely difficult to capture. Cornwall (Citation2016) highlights the value of understanding the ‘hidden pathways’ that women travel on their journeys toward empowerment. Women can be involved in highly complex bargaining and strategizing which may at times appear counter-intuitive. Manda and Mvumi's (Citation2010) research in Zimbabwe indicates that culturally normative gender roles in stored grain management and marketing were articulated in all case-study households. However, behind the scenes women developed multiple strategies to strengthen their control over stored maize. In some cases, apparent acceptance of 'defeats' was a necessary corollary to achieving a more important long-term objective (this would not have been immediately evident to an observer). Galié and Farnworth (Citation2019) term the disjuncture between what is done, and what is seen to be done – in order to apparently conform to locally valid gender norms – the gender norms façade.

Building on Kabeer (Citation1999), Sachs and Santarius (Citation2007) suggest three proxies for assessing achievements: recognition, distribution of resources, and access to opportunities. First, recognition means an acknowledgement of the identities and roles individuals freely choose to adopt in a society. The concept refers to awareness of the ‘self’, as well as recognition of the public aspects of this self by others (ibid.). We add that reducing the divergence between individual self-awareness, and public recognition of that self-awareness, may help to reduce the tiring necessity of maintaining a gender norms façade. Second, Sachs and Santarius argue that analyzing the distribution of resources is a way of establishing the degree to which the right to self-determination has become normatively established. Equity in resource distribution, we add, could be considered a material expression of the realization of their first proxy - recognition of the public aspect of the self. Third, and this relates fundamentally to the concept of meaningful choice, individuals need access to opportunities to realize the first two proxies. The ability to deploy agency is meaningless unless opportunities to select between options are available.

We bring together these concepts of power and agency to help us reflect upon the Nigerian fieldwork data. Prior to this, we use the conceptual framework to consider some of the broader Nigerian literature. This is to help us contextualize our own contribution.

Literature Review

In Nigeria, gender-specific identifications between crops or livestock and their growers were common in the past, particularly in specific ethnic groups. For example, ‘ephemeral’ annual crops, including maize, cassava, melon, cocoyam and beans, were widely considered ‘women's crops’ (Ezumah & Di Domenico, Citation1995; Peterman et al., Citation2011). Hausa-Fulani women were – and are – prominently engaged in producing and marketing dairy products though men generally own cattle (Peterman et al., Citation2011). Among the Igbo, Yoruba and some other ethnic communities, yam is still considered a prestigious male crop which is closely associated with indigenous cosmologies (Obidiegwu & Akpabio, Citation2017). The gendered hierarchy of crops is evident in the following citation, which apparently pertains today. ‘Cassava is planted by women, unlike yam, the king of all crops that is planted by men’ (Nwapa, 1975, cited in ibid., 2017, p. 33). This literature suggests that, in relation to crop choice, individuals have historically rarely had freedom of choice. Rather, crop choice has been primarily determined by gender. Today, gendered identifications of women or men with specific crops and livestock products is waning, though it still exists to some extent. It may be tentatively suggested that public acknowledgement of the self (Sachs & Santarius, Citation2007), with women freely selecting the crops they want to grow, is becoming more common.

Public recognition of the self is necessarily tied to self-awareness: women need to have been able to develop their power within and act upon it in order to obtain recognition. Little research appears to have been conducted in farming communities on how women feel about themselves and the ways in which they exercise agency. Aguda-Oluwoa and Onib (Citation2017), using a Self-Esteem Index with 1200 women in SW Nigeria, found positive correlations between women's self-esteem and their economic empowerment. Single women (single, divorced, separated, widowed) were more economically driven than married women. Enete and Amusa (Citation2010) examined decision-making processes in cocoa-farming households and found that better educated, more experienced married women contributed more than less educated women to intra-household decision-making. However, many factors constrained the efficacy of women's participation. Limiting factors included higher numbers of adult men in the household, men's assertions that women have no ideas about farming and that women are subordinate to men, and low self-esteem among women. These examples show how the ways in which men sometimes articulate their power over women serve to limit women's sense of power within and power to act.

Some researchers find correlations between the amount of money women provide to the household and their ability to exert effective agency. Angel-Urdinola and Wodon (Citation2010) used Core Welfare Questionnaire Indicator (CWIQ) surveys implemented in eight Nigerian states in 2003 to study intra-household decision-making. They found that women who contribute more income to the household experience higher decision-making power, particularly when they are the main contributor. Women in the poorest households experience ‘especially low’ decision-making power because they are rarely the main provider of household income (ibid., p. 397). Interestingly, though, when poor women are able to contribute more absolute income, this raises their effective decision-making power more strongly than among non-poor women. Overall, women's ability to exercise their agency is stronger in relation to domains normatively associated with women: food, education and health. It is lower with respect to productive assets (ibid.). A game playing study of rural households near Kano in northern Nigeria suggests that gender norms may trump economic contributions (Munro et al., Citation2010). The findings indicated that senior wives receive more money from their husbands than junior wives regardless of the size of each women's own contribution. The rationale for favoring senior wives is not clear, nor whether they exercise more agency than junior wives (ibid.).

When attempting to understand the implications of findings such as these, it is useful to note that many rural households are not unitary. Rather, women and men generally operate different production, business and consumption systems, with connections at certain points (Verschoor et al., Citation2019). Studies of polygamous and monogamous households show that in both cases spouses invest only part of their endowments into a common fund (ibid.; Munro et al., Citation2010). In the North, Hausa women usually manage their own plots and hire labor for agricultural tasks. Despite seclusion Hausa women can be highly active traders who engage in transactional relationships, often involving money, with their husbands (Verschoor et al., Citation2019).

We noted above that examining the distribution of resources is one way of establishing the degree to which a woman's right to self-determination has become normatively established. Despite their strong involvement in farming, many rural Nigerian women face markedly weaker access than men to land, inputs, irrigation, credit, extension and markets, and they experience greater time poverty (Forsythe et al., Citation2016; Olaosebikan et al., Citation2019; Oseni et al., Citation2015; Takeshima & Yamauchi, Citation2012; Ugwuja & Nweze, Citation2018). Regarding access to land, women across the country manage smaller plots, and their right to land is often weak, particularly over the long term (Oyerinde, Citation2008). This can be largely ascribed to the prevalence of patrilineal kinship and inheritance systems across the country, which can also have the psychological effect of creating ‘severe cultural inhibitions to the aspirations … of women’ (Iruonagbe, Citation2009, p. 207). The situation of women does not appear to have improved much over time. Dillon and Quinones (Citation2009) examined gender-differentiated asset dynamics in Northern Nigeria between 1988 and 2008. They found that the value and number of women's assets increased more slowly than men's assets, leaving men relatively better off after two decades had elapsed.

With respect to labor, women – particularly in the South – conduct most or all productive tasks on their own plots, including land preparation, planting, weeding, applying inputs, harvesting, processing, storing and preparing food items. Furthermore, women work on men-managed plots and conduct most household tasks (Peterman et al., Citation2011). In the South, strong male command over household labor (women's labor as well as the labor of junior men and children) and higher use of herbicides – due to men controlling decisions on how to allocate financial resources – on men's plots, is an important contributory factor to gender productivity gaps (Oseni et al., Citation2015; O'Sullivan et al., Citation2014). Women are directly discriminated against in rural wage markets, being paid on average 14% less than men for the same work even if they have the same qualifications and experience (SOFA, Citation2011). This may result in perceptions that the opportunity costs of women moving into off-farm income generation are higher than those for men. However, this hypothesis requires substantiation.

These findings suggest that male power over women is structurally entrenched. Nevertheless, there is evidence for women exerting their agency. Enabling factors can include their seniority in the household, income cohort, ethnic community, and their economic contributions. Relaxation in gender norms around who grows what suggests that increasing numbers of women are experiencing a sense of power within, and as a consequence are exercising power to act. Taken together the findings suggest that farming women need to negotiate deep patriarchal and patrilineal constraints when attempting to exert agency.

Research Design

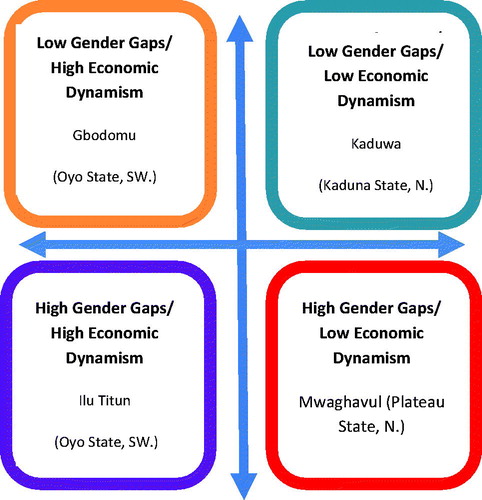

The methodology builds on GENNOVATE research protocols (Badstue et al., Citation2018). Community selection was based on a purposive, maximum diversity sampling approach guided by two criteria considered significant for assessing gender differences in agricultural innovation: (i) economic dynamism, and (ii) gender gaps in resources and capacities. A 2 × 2 matrix was developed with wide or narrow gender gaps on one axis, and high or low economic dynamism on the other (). Economic dynamism was assessed through consideration of levels of infrastructure development, market orientation among smallholder farmers, relative percentages of buyers and sellers in markets, livelihood diversification including on and off-farm employment, and the level of natural resource endowment for agriculture. Gender gaps were assessed through considering the school enrollment rates of boys and girls, levels of women's leadership, and women's mobility norms. Application of the matrix resulted in the selection of four villages, two in northern Nigeria and two in southwest Nigeria (). The community place names are pseudonyms.

The research teams carried out 15 sex-disaggregated data collection activities in each community (). Methods included three sex-disaggregated focus group discussion (FGD) instruments. The first was conducted with low-income women and men, the second with middle-income women and men, and the third with young women and men (six FGDs per study community). A further nine semi-structured interviews (SSI) were conducted in each location: (i) a community profile with men and women key informants to obtain local demographic, social, economic, agricultural, and political information, (ii) innovation pathway interviews with two men and two women known for trying new things in agriculture, and (iii) life story interviews, likewise conducted with two men and two women. In total, 269 people (139 women: 130 men) across the four communities were interviewed (). The data analyzed in this article are drawn from all study sites. The data were gathered in standardized formats, cleaned, and systematically coded using NVivo social science software.

Table 1. Research tools.

Table 2. Overview of respondents.

This section presents the study sites. Gbodomu is a community with around 20,000 inhabitants in Oyo State in southwest Nigeria and is located in savannah vegetation and lowland rainforest zones. Located near a major town, Gbodomu is the most prosperous of the four communities. It is electrified, has a daily market, good roads, post offices, banks, and primary and secondary schools with other tertiary institutions in close proximity. The dominant ethnic community is Yoruba (70%) with the remainder identifying in almost equal numbers as Igbo, Hausa, Sabe, Fulani, Egede, Abassa, Boro and Tifi. People practice Christianity, Islam, and Animism. Most people are farmers cultivating a wide range of food and cash crops. Few women hold positions of authority, though some older women are elected to oversee market affairs. Women experience good mobility within the community, and girls and boys have equal opportunity to attend schools.

Ilu Titun is a village of 2500 people in Oyo State and experiences an equatorial climate. It has hardly any infrastructural development, lacks electricity, and has poor roads. Its only major institution is a primary school. Most residents are Yoruba cultivating crops for their own consumption and they sell processed and unprocessed crops in a weekly local market. This is patronized by traders from distant locations. Some older women are elected as Iyalodes. They are in charge of settling disputes among women and have some influence in local market management. Women are able to move freely within the village but not beyond it.

Sabon Birni is a community of 15,000 in Kaduna State in northern Nigeria. It experiences a tropical climate. Major facilities include a weekly market, a health clinic, and primary and secondary schools. Sabon Birni is reputed for its agricultural productivity, business dynamism, and local industrial products. About half the population is Hausa, 40% Kurama, and the remainder are Amawa, Gure, Kahugu and Chawai. Most respondents were Christian, although a large number of Muslims inhabit the village. While Christian women experience few mobility restrictions within the village Muslim women’s mobility in public spaces is limited.

Mwaghavul is a village of about 2000 people in Plateau State in northern Nigeria. This is within the northern Guinea Savannah agro-ecological zone and the climate is near temperate. Mwaghavul is electrified, has a primary school and nearest the market is 4 km away. Everyone belongs to the Mwaghavul ethnic community and the majority are small-scale farmers. Few women hold leadership positions, men often restrict their wives’ mobility outside the local village, and parents invest more in boys’ education.

To help keep track of community locations, the abbreviation (SWN) to indicate South West Nigeria is appended to mentions of Gbodumu and Ilu Titun and the abbreviation (NN) to indicate Northern Nigeria is appended to mentions of Sabon Birni and Mwaghavul.

Results

In the Introduction, we suggested that new technologies, because they promise important benefits – increased incomes, lower workloads, better food security, etc. – can denaturalize and expose gender norms and power relations. This is because the adoption of such technologies inevitably requires women and men to renegotiate the rules of the game. In this section, we use our conceptual framework to analyze how women and men talk about benefits from IMVs. We focus on the power relations that facilitate, or hinder, their realization of these benefits. Beyond this, we explore how norms help to determine the extent of women's decision-making space.

As part of our commitment to treating people as ends in themselves, we cite respondents frequently. In order to simplify referencing, we provide citations with varying degrees of detail about the respondent. We primarily group respondent views according to their gender and income cohort (low or middle-income) and in such cases do not repeat such information alongside every quotation. In cases where opinions were the same across all respondents and study sites, we indicate this. We only provide further information when respondent views are more singular.

Trends in women's and men's relative empowerment

First, we explore trends in women's and men's relative empowerment over the past decade in each location. Is women's sense of agency increasing, or decreasing, as an absolute value? What do men think about how their own agency has changed in the same time frame? This information provides us with a contextual understanding of how gender norms, in relation to agency, may be shifting over time.

Our data was developed through two exercises. First, we asked middle-income respondents to participate in a trend analysis called the Ladder of Power and Freedom (Petesch & Bullock, Citation2018). Respondents are asked to rate on a scale from 1 to 5 the ability of most village men (if a men's FGD) or most village women (if a women's FGD) in the community to make important decisions. These include decisions about their work, starting or maintaining an income-generating activity, and whether to start or end a relationship with the opposite sex. Participants are then asked to think back and locate the step men and women in the community typically found themselves on ten years ago, and to reflect upon the reasons for any changes.

summarizes the findings. A score of 1 represents very little decision-making power, while 5 represents the ability to make most major life decisions. In all communities, women and men report relatively low historical and current decision-making power. There are notable gender differences. In Mwaghavul (NN) and Sabon Birni (NN) – communities experiencing low economic dynamism, women perceived that the agency of women has fallen slightly over the past decade. However, men from these communities consider that men's agency has increased by over one step. Men in Gbodomu (SWN) and Ilu Titun (SWN), the high economic dynamism communities, report very similar levels of increase. Women in Ilu Titun (SWN) also consider that women's agency has improved by one step, and in Gbodomu (SWN) women consider it has doubled. In Mwaghavul (NN) and Gbodumu (SWN) women and men report very similar levels of current agency whereas in the other two locations women's reported agency is at least a step lower than men's.

Table 3. Trends (mean) in perceptions of agency level for middle-income men and women across the four study sites.

Low-income respondents participated in a different trend analysis. This is called the Ladder of Life (Petesch, Citation2018). They are asked to develop a poverty line for their community, during the course of which they discuss how to define poverty, including material and non-material factors. They then distribute households in the community above or below the poverty line (using 20 seeds) and explain the rationale for their distribution. Following this, they are asked to repeat the exercise focusing on the situation ten years ago. The ensuing discussion focuses on the reasons for any changes in the percentages of households placed below and above the poverty line.

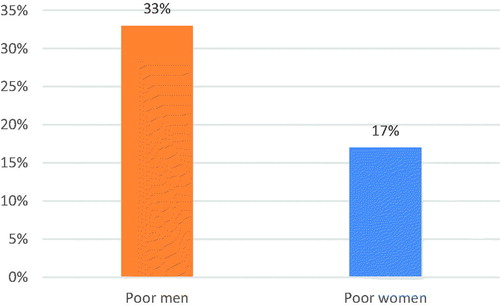

collates findings from all four communities. In the narrative discussion, low-income women in Mwaghavul (NN) and Sabon Birni (NN) considered that improved maize alongside improvements to other crops are the primary reason for households being able to improve their economic status over the past decade. They reported that better access to improved maize varieties and high market demand have improved morale, with both women and men investing more in maize and working harder on their farms. In the other two sites, low-income women do not discuss maize specifically, but they associate the ability of households to move out of poverty with better agricultural markets. Women in Gbodomu (SWN) provided an iterative cause–effect rationale, arguing that markets are improving due to more people becoming involved in agri-business.

Overall, however, low-income women perceive a considerably more limited movement out of poverty for their households (17%) than do low-income men (33%). This could be due to differences in benefit sharing within the household. It could also reflect differences in how women and men experience and perceive poverty, and potentially differences in their aspirations.

Experiences of Agency and Power. Women Maize Farmers

The next set of fieldwork activities focused on the ways in which power is enacted to facilitate, or hinder, women's and men's access to the benefits of IMVs. We report on this, and more broadly on how power relations constrain or liberate agency in other fields of life important to the respondents.

Women respondents everywhere experienced strengthened power to act benefits. They remarked that IMVs are easy to adopt, mature quickly, and have higher yields. Women prioritized the contribution of improved maize to securing household food security. This helps them meet their ascribed gender roles as food providers. They pointed out that early ripening means that income flows start earlier, helping women to meet household expenditures on time. Women process maize into snack food products which are sold in local markets. ‘Different products can be got from maize like ogi, tuwo, and eko’ (Gbodomu, SWN), and ‘We make pap, tuwo, fufo, elubo, and a host of other things from maize. This increases our income’ (Ilu Titun, SWN). A low-income woman was typical of all women in that she viewed the contribution of improved maize synergistically: ‘Improved maize is our top innovation because now farmers will not get hungry. It is an early source of income for households, and it matures within three months.’

At the same time, though, women felt they could not maximize their benefits from IMVs due to men's dominance of decision-making. This was particularly the case for married women. In low-income respondent cohorts, married women explained that their ability to take advantage of IMVs is restricted primarily by the nature of their relationship to their husbands. ‘Women have to ask their husbands to take decisions, because men believe that they are the boss. Women are subject to them and need to be submissive. Women are expected to consult their husbands in everything they do’ (Sabon Birni, NN). Married women frequently expressed a fear that openly expressing self-confidence was perilous because it could endanger their relationship to their husband, upon whom they depend for access to productive resources, including land. Women recognized that they were prone to internalizing their lack of self-confidence when they described a mindset of dependence on husbands as a major obstacle to moving forward in life. They acknowledged that such dependence could contribute directly to women's impoverishment: ‘If a woman believes that it is her husband’s responsibility to supply all the needs in the home and her main assignment is to breed and raise children, then she will never come out of poverty’ (Sabon Birni, NN). Women in Gbodomu (SWN) and Ilu Titun (SWN) agreed and they highlighted additional factors, including lack of money, lack of support, and laziness. These in themselves are symptomatic of women's low self-esteem and weak agency.

Turning now to middle-income married women, a woman in Ilu Titun (SWN) remarked ‘tough men like my husband don’t give women freedom to make decisions.’ When married middle-income women report agency, this is typically in relation to tasks already perceived as within women's domain. In Mwaghavul (NN), for instance, women reported ‘I can carry out and implement a few decisions in my home because my husband wants me to show initiative’, and ‘our husbands leave some responsibility to their wives.’ Gbodomu (SWN) is the only location where some middle-income married women articulate a significant degree of power within and power to act. They argued that whilst men were traditionally responsible for meeting their wife's needs, today women with their own resources – money and land – are independent. One said, ‘I work and cater for my family and I make decisions about the clothing I want to buy for myself, food to prepare and eat for all members of my family. I have farm land and I control it.’ Another woman reported, ‘We women have made enough money to allow us enjoy the freedom to make major decisions. I believe money determines our level of power and freedom.’

The majority of men respondents in low- and middle-income cohorts supported their wives' engagement in local market interactions – including the sale of maize and maize products, or in off-farm occupations, provided their wife's income is primarily allocated to household needs – an example of men expressing power over women. Women's freedom to work was contingent upon all observers agreeing that such work was secondary and complementary to men's contributions. ‘We see working mothers as hardworking and responsible. They have to struggle so they can complement the efforts of their husbands. That is the way we see it here’ (low-income man, Sabon Birni, NN). Whilst some men in low- and middle-income cohorts in Ilu Titun (SWN) and Sabon Birni (NN) were ambivalent about the necessity of women securing money, men in Mwaghavul (NN) and Gbodomu (SWN) supported it. ‘It's good because she will help in supplementing her husband’s income’ (low-income man, Mwaghavul, NN). These remarks are examples of power through: men are happy for women to earn money provided it remains under men’s control and is less than men’s contribution. Were women to earn more, then men would fear being disempowered in the eyes of the community.

The ability of women to make money from maize is not only governed directly by their husbands. Embedded gender norms, particularly around mobility, infuse the wider environment and mean that women's access to opportunities is considerably more restricted than it is for men. Women respondents, regardless of age and income cohort, repeatedly remarked that it is hard to earn significant money from local sales of processed maize products, yet it is very difficult for women to enter large maize markets selling unprocessed improved maize. All respondents understand that profits from selling improved maize unprocessed and in bulk are high at larger markets. However, men almost exclusively patronize these markets. Only three women, from Ilu Titun (SWN), Gbodomu (SWN), and Mwaghavul (NN), had become unprocessed maize buyers and sellers, and none were particularly successful. The difficulties women face in trying to grow maize businesses may be partly related to a lack of business acumen and experience, but a primary reason is limited personal mobility in all four communities (albeit to a lesser extent in Gbodomu, SWN). In Sabon Birni (NN), for instance, women chafed at how the local market is not large enough to accommodate their maize processing and other agri-business ventures, but they are not permitted travel to more distant markets where ‘there are always people ready to buy’. The male village head remarked that access to such markets is ‘very easy because the road is good and trucks are available. However, women find it difficult to go there because we prefer that our wives patronize the local market. Men are meant to travel far - not women.’

The findings so far suggest that men provide their wives with a limited freedom to act - albeit with a number of provisos attached. This partly trumps women's ability to develop their power to act to realize their agency and select between options.

However, widows and separated women reported stronger power within and power to act. ‘I now have a little power and freedom because I am no longer with my husband. We are separated and he has moved in with another woman. So I make my own decisions’ (divorced woman, Ilu Titun, SWN). ‘The affairs of my home are my sole responsibility except in a few cases where I have to ask my son’s opinion’ (widow, Sabon Birni, NN). Nevertheless, the findings show that overall normative environment has gendered effects – including mobility restrictions, which affect all women. These limit the ability of women to maximize their benefits from IMVs, and, more broadly, affect their ability to realize their agency in other domains.

Experiences of Agency and Power. Men Maize Farmers

We now examine how men respondents consider they benefit from IMVs. The findings suggest that the relationship between the introduction of IMVs, and the ability of men to secure benefits, is substantially stronger than it is for women.

Improved maize facilitates clear power to act benefits for men in all income cohorts and locations. Higher market prices combined with higher yield strengthen male incomes (over which they have almost total control in contrast to women) and as a consequence, men experience improved spending power. Men everywhere agreed that the traits expressed in IMVs enable ‘a quick source of income.’ This is because ‘the new maize, with early maturity, high demand, and high prices in the market can help you overcome poverty. Without improved maize, this is difficult.’ Echoing other male FGD participants, another man added, ‘Most of us make a lot of profit from sales of our produce and this has given us some level of freedom to do what we want. There is no power without money’. As a consequence, argued a third participant, they now have ‘the power and freedom to make many major life decisions’. Men in the two South West research sites did not mention the contribution of IMVs to household food security. However, in the North, ensuring the household has sufficient maize is an important element of men's gender identity. Northern men respondents remarked that ‘Maize is the most important crop for men because it is our major household food crop’. Although men in all locations partly or largely command women's labor and incomes, no men mentioned women as contributing to their success as maize farmers.

It is not clear from the data whether, or how, women benefited from men’s income. Often, women are responsible for putting food on the table but may not have sufficient income to do so effectively. In this light, the commitment of men in the two Northern sites to ensuring sufficient maize to cover food security needs may well be very important to ensuring women can meet their gender roles adequately. Women in all sites may experience increased status, and potentially improved living standards, due to an increase in their husband’s income. This comes back to the concept of ‘power through’ whereby a person may benefit — even if they have not exercised agency — through their significant relationships to the person whose power has increased. And, if income is pooled, women may benefit directly provided they have sufficient say in intra-household decision-making.

Respondent rationalizations for gender inequalities in power

In the Introduction, we suggested that the ability of women to participate effectively in agricultural innovation processes may necessitate normative change in order to facilitate women's ability to set goals and act upon them. Our data suggest that the respondents recognize that normative change – to a greater or lesser degree – is taking place in their communities, and that such changes have an effect on women's and men's agency. We wanted to know how respondents feel about such changes. Do they support them? In particular, what do they think when women appear to become empowered?

In FGDs, young women and men, and low-income women and men, were asked to discuss what gender equality means, and whether they believe it to be a good or bad thing. Middle-income women and men discussed vignettes in which the normative roles of women and men were reversed (Elias et al., Citation2018).

The majority of respondents, regardless of their own gender, did not see gender equality as positive. Indeed, many strongly disagreed. Male respondents were most outspoken with only two young men, from FGDs in Mwaghavul (NN) and Gbodomu (SWN), arguing that men and women are equal. All young women, and all middle-income women, in all study locations disagreed with the concept of gender equality. However, low-income adult women in all locations agreed with gender equality. How did respondents justify their views?

First, most young and low-income men provided religious justifications for why women and men cannot be equal. One young man from Sabon Birni (NN) explained that ‘God created men to rule over women. Saying they are equal goes against what God has ordained’. A low-income man from Mwaghavul (NN) argued that ‘even God himself said that man is the head. The woman is under him.’ While religion – in these cases Christianity – is used to justify cultural norms of gender inequality, men contended that the practice of gender equality leads to women claiming freedoms, which cause them to express behaviors that directly threaten male power over women. ‘Gender equality is a very bad thing. The moment you let women hear about women and men being equal, you will see what their reaction will be. They will be so very rude. A woman should not be allowed to have the same opportunities as a man, because they have every tendency to be proud‘ (young man, Gbodomu, SWN). This view was held by most men.

Women broadly agreed that since men are the head of the household, women cannot be equal. However, they did not justify inequality in the same ways as men. The findings show that all young women asserted that gender equality is a bad thing, ‘because the man is the head of the family. He must be treated with great respect’ (Gbodomu, SWN). Low-income adult women recognized the reality of gender inequality, but critiqued it. ‘There is no equality between a man and a woman because society believes men are the head of the family. We, however, feel there should be some form of consideration for women’ (Gbodomu, SWN).

Second, since men pay lobola (bride price) to their wife's parents upon marriage, some men consider women are the property of men, and so equality is impossible. A low-income man (Ilu Titun, SWN) stated, ‘Women are never going to be equal to men, they are like any other property I own. I am responsible for all her needs, she is below me, we can never be equated. Gender equality is bad.’ This view was expressed widely by men across the study communities.

Third, for some respondents gender norms, and norms associated with ethnic identity, intersect and indeed merge with each other. In Ilu Titun (SWN), for example, a woman explained that Yoruba culture means ‘the husband has to provide money for feeding of the family. He can't do the household chores. It is not allowed.’ The fusing of ethnic identity with gender identity suggests that unpicking and questioning gender norms could be tantamount to querying ethnic identity as well.

Fourth, the key gender norms façade is that men are the household head and provider, and that women are primarily homemakers and mothers. Vignette exercises – whereby respondents are asked to discuss the potential benefits of role reversals, for example that women earn money and men stay at home caring for children – elicited horrified responses from middle-income respondent groups in three of the four study communities. Women and men alike argued that the man who stays at home would be considered a victim of witchcraft, and be called a ‘boy-boy’, ‘house boy’, a ‘fool’, and a ‘woman wrapper’. The concept of power through helps us understand that negative community judgments of gendered role performance can rapidly lead to significant questioning of a man's masculinity. Only in Gbodomu, close to a major town, did some middle-income respondents find some benefit in role reversals. A woman said that the rigidity of gender norms meant that urban couples want to live away from their broader family in flats, ‘so that they can do whatever they want without any external influence that will meddle with how they run their family.’ Another woman commented, ‘Some people might say the husband has been charmed [bewitched] by the wife, while other people would say that’s the way of the learned.’ Men in Gbodomu accepted working at home provided they can control the income of their working wife. ‘If she will faithfully hand over the proceeds to the husband, it is not a bad idea for the husband to contribute to the housework and care for children.’ said one man.

Women had mixed feelings about becoming breadwinners alongside their husbands. Approximately half of all women respondents, regardless of age or income cohort, said they admired women who work outside the home: ‘The woman who goes out to make money to meet her responsibilities in the home is a virtuous woman’ (Mwaghavul, NN). The other half criticized such women, seeing them as irresponsible mothers and potentially unfaithful. ‘This category of women does not have much time to take proper care of their children’ (Sabon Birni, NN).

Discussion

Walter Benjamin (discussed in Richter, Citation2016) argued that the thing to be scrutinized [in our case, how gender norms affect women's ability to secure benefits from IMVs] needs to be torn out of its context in order to become thinkable in a new way. ‘It has to step into our vision and consciousness as an unanchored object … that asks to be reinterpreted along with the cultural framework from which it emerged’ (ibid., p. 96). The introduction of IMVs, and our fieldwork discussions with respondents about IMVs, in the four study communities, would certainly appear to have allowed the respondents to think about ‘the thing’ – in our case women's empowerment and their agency – in a new way.

The literature review established that rural Nigerian communities tend to be strongly asymmetric and patriarchal. Benefits flow much more strongly to men than to women through patrilineal kinship systems and patriarchal norms which tilt the playing field against women (van Staveren & Ode Bode, Citation2007). Our findings demonstrate that women and men farmers secure benefits from IMVs. However, men accrue more benefits and benefit directly. Men have unfettered mobility and opportunity. They can access markets near and far. The maize they sell is unprocessed and requires no transformation. Men do not question their right to devote profits from maize primarily to their own concerns, nor their right to secure a high level of control over the monies women make. Undoubtedly, some men are constrained in maximizing their benefits from IMVs, for example low-income men are likely to find it harder than higher-income men to exponentially expand the productivity and volume of IMVs due to lower investment capacity. However, the findings show that being a man trumps other forms of intersectionality when it comes to benefiting from IMVs.

Conversely, women find it considerably more difficult to benefit. They are restricted to local markets. They have to expend considerable time on transforming maize into salable products with low profit margins. Women are expected to devote the monies they make to household concerns and to provide monies to their husband. Women's benefits relate to the fact that IMVs increase the absolute size of the ‘maize cake’. They expect to get a larger slice as a consequence. However, the absolute potential of IMVs for boosting women's incomes and other options of importance to women is hampered by gender norms that significantly restrict the agency of most women.

There is no evidence that respondents are under any illusions that women and men are equal. In fact, they demonstrate high levels of consciousness that this is most certainly not the case. The ways they legitimize gender inequalities are importantly different, however. Some men retreat to a mythical space to claim that gender inequalities are ordained by God himself. As such, gender inequalities are beyond the reach of any form of rational questioning by human beings. At the same time, the very process of constantly attempting to re-naturalize gender norms that privilege men has the effect of denaturalizing that norm and thus opening it to question. A second line is therefore to suggest that women are property. Through the payment of bride price, men are entitled to take most decisions. At this juncture we acknowledge that a few men respondents openly supported gender equality. We postulate that other men supportive of gender equality may have felt muted by others. The findings show that men who try to renegotiate their masculinity and to take on roles normatively ascribed to women are harshly condemned. It is only in one community that some men, and some women, are open to contemplating role reversals.

Nearly all women asserted that men are the head of the household. However, their views were nuanced. Young women expressed fear of challenging male household heads. By way of contrast, low-income adult women implied that this norm was not fit for purpose. The reality gap between the norm, and the opportunity costs of maintaining this norm, seem too large for women with very low-economic margins. Most married middle-income women publicly fell in with the norm. Only middle-income married women with considerable money had sufficient ‘power and freedom’ to disassociate themselves from this norm, as did single women.

How are we to interpret resistance to gender equality? There is no reason to believe that our respondents are unaware of the economic costs of restricting women's income generation capacity to a level lower than that of men, yet the culturally determined ‘price’ (women's empowerment) for leveling up seems to be too high for many men to contemplate. Kandiyoti (Citation1988) argues that women strategize carefully to promote their gender interests within the set of specific constraints and opportunities presented by the social institutions which characterize their community. She terms this the ‘patriarchal bargain’ because men reciprocate by providing women with certain privileges (ibid.). The very public ‘rejection’ by most women in this study of gender equality could be interpreted as them upholding their part of the patriarchal bargain. A failure to openly challenge men does not necessarily mean, however, that challenge does not occur. We postulate – and here more research is needed – that actively maintaining a separation between women's and men's worlds may be a deliberate strategy by women to protect their ability to express their agency. We return here to the concept put forward by Cornwall (Citation2016) that women negotiate their journeys toward empowerment on hidden pathways. Furthermore, supporting gender norms that privilege men as heads of household can be considered a strategy for ensuring that men uphold their part of the patriarchal bargain. When men withdraw from the bargain, this can present women with unbearable costs, including losing access to land, their homes, their status, and, in many parts of Nigeria under customary law, custody of their children (Iruonagbe, Citation2009; van Staveren & Ode Bode, Citation2007).

The concept of power through provides further insights into the reluctance of many men to facilitate women's agency. As a reminder, this concept suggests that a person can be empowered, or disempowered, without them having acted. The concept of power through captures an involuntary aspect of empowerment and disempowerment. This allows a reading that men can feel actively disempowered through a positive change in women's empowerment. This can occur when gender norms – expressed by community members – which privilege men as decision-makers and breadwinners condemn and even ostracize men who appear to fall short, or who wish to expand the definition of what 'being a man' can mean. As a consequence, women's empowerment can seem like a zero-sum game to men: the more power women have, the less power men have (and in particular, the less masculine they are). The critical issue here is how power is perceived, by men themselves and by women and men in the broader community. Since gender relationships in the communities we discuss are configured primarily by power over dynamics, it is not surprising that men may fear demotion.

Conclusion

In 1899, Veblen (cited in van Staveren & Ode Bode, Citation2007: 903) writing of America, said, ‘For the modern man the patriarchal relation of status is by no means the dominant feature of life, but for women … this relation is the most real and the most formative factor of life.’ Though more than a century has passed, and the country is different, this observation seems very pertinent to our findings in Nigeria. Our fieldwork findings are not particularly novel: they are largely borne out by the Literature Review. We hope, though, that our conceptual framework helps us think about such findings in a new way. In so doing, we further hope that we have engineered a return to some of the more radical, less instrumental thinking that typified work on gender in the 1980s and 1990s. We recognize that our focus is unapologetically supportive of maximizing women's agency. In so doing, we acknowledge that considerably more work needs to be done to understand and support men and boys in ways which focus on their own needs. In particular, it is important to engage men in ways which promote gender equality as a ‘win-win’ rather than a ‘negative-sum game’, which promote acceptance of shared responsibilities (e.g., performing unpaid tasks together), which encourage positive thinking about decision-making processes, and which motivate men to promote gender equality in and outside their homes (Farnworth et al., Citation2020).

Even so, we contend that gender inequalities, which disadvantage women remain in serious danger of being ‘naturalized’ in the development discourse. Anderson and Sriram (Citation2019) liken the struggle to get the AR4D system to recognize gender equality as a global good with global benefits as akin to the task of Sisyphus. Sisyphus, in Greek mythology, was the king of Corinth who was punished in Hades by having repeatedly to roll a huge stone up a hill only to have it roll down again as soon as he had brought it to the summit.

Shaw (Citation2008 – originally 1903, p. 343) wrote, ‘the reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore, all progress depends on the unreasonable man.’ Working on gender equality still demands a commitment to being unreasonable. It is in this light that we suggest merely introducing improved technologies into deeply gendered environments does not mean that women and men will benefit equally. Indeed – though this hypothesis needs more research – it is possible that such technologies may deepen gender gaps in the normative settings described. The findings suggest that men, on the basis of their privileged agency, freedom of movement, and better access to productive assets, may pull away from women – in same households – in terms of the incomes they receive, and with respect to the formation of different kinds of capital. This in turn may mean that women – over time – are less able to adopt new technologies such as IMVs, and that they may find it ever harder to capture benefits. Rather than enhancing women's agency, innovations may actually entrench and deepen gender inequalities. As a reminder, Dillon and Quinones (Citation2009) provided evidence, cited in the Literature Review, that this process is already happening. They assessed the value and number of women’s and men’s assets over a 20-year time period (1988 to 2008), noting that women’s assets increased more slowly than men’s assets, leaving women relatively worse off. This in turn leads us to question the framing of gender norms by respondents in the communities discussed in this article as ‘natural’ and God-given. Risseeuw (Citation2005), in a study of gender relations in Sri Lanka under colonial rule, shows that although descriptive and injunctive norms and sanctions appear designed to maintain gender relations in a steady state, they are in fact undergoing constant change. She demonstrates how gender relations with regard to property were imperceptibly transformed over time such that concepts of access, control and ownership which would have appeared to one generation as unthinkable came to seem normal or obvious to later generations.

Further maize-based systems research into community and intra-household decision-making processes in relation to adoption processes, and how women and men expect to benefit from adopting improved varieties of maize, is important. As part of this, it would be valuable to examine in more detail the associations people make with the concept of ‘gender equality’, and to widen understandings of the different ways power – in the various formulations outlined in this paper – is enacted in specific contexts. An improved, research-based understanding of the complex relational nature of empowerment could facilitate the ability of Agricultural Research for Development (AR4D) to develop more effective strategies to enhance women’s empowerment whilst supporting men. As part of this, feminist action research methodologies which allow women and men respondents to co-produce research with formally-trained scientists (Feldman, Citation2018; Farnworth et al., Citation2016; Farnworth, Citation2007) should be considered. Gender transformative approaches (GTA) are also important because they engage with the complexity of gender to support women and men to act on the norms, attitudes and wider structural constraints that limit their opportunities and outcomes (Cole et al., Citation2014, p. 7). GTAs can be enormously effective in fostering normative change in a very short time (Farnworth et al., Citation2018).

Acknowledgements

This paper draws on data collected as part of GENNOVATE case studies in Nigeria funded by the CGIAR Research Programs on Maize. Development of research design and field methodology was supported by the CGIAR Gender & Agricultural Research Network, the World Bank, the governments of Mexico and Germany, and the CGIAR Research Programs on Wheat and Maize. Data analysis was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The authors wish to thank the women and men farmers who participated in this research, as well as the local data collection team and the data coding team. A special thank you also goes to Patti Petesch and to Dr. Alessandra Galié for kindly commenting on an earlier draft of this paper. The views expressed in the article are those of the authors and not of any organization.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cathy Rozel Farnworth

Dr. Cathy Farnworth is a gender specialist with over 20 years’ experience in pro-poor and gender-responsive value chain development, mainstreaming gender in projects and research, and gender-transformative methodologies. Cathy has a particular interest in change processes and how they affect smallholder agriculture systems. She has obtained significant experience in many countries in Sub Saharan Africa and South and South East Asia.

Lone Badstue

Dr. Badstue is a Rural Development Sociologist focusing on gender, social heterogeneity and informal institutions in relation to agriculture and natural resources management. She has 20+ years’ experience in research and applied development related to local people’s perspectives, technological change and innovation processes, local livelihoods and farmer decision making.

George J. Williams

George J Williams is a freelance researcher and editor, most recently with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in Texcoco, Mexico. His work focuses on gender and social inclusion in rural and urban settings of the Global South.

Amare Tegbaru

Dr. Amare Tegbaru (now retired) was International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) Gender Research Coordinator. He has a PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Stockholm.

Hyeladi Ibrahim M. Gaya

Dr. Hyeladi Ibrahim Musa Gaya holds a Ph.D in Agricultural Economics from University of Maiduguri, Nigeria, where he is currently a lecturer. At the time of this study Gaya was working with IITA as a Postdoctoral Research Fellow and on the PROSAB project. Gaya is experienced in qualitative and quantitative research methods, in gender analysis and gender mainstreaming.

References

- Abdoulaye, T., Wossen, T., & Awotide, B. (2018). Impacts of improved maize varieties in Nigeria: Ex-post assessment of productivity and welfare outcomes. Food Security, 10(2), 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-018-0772-9

- Aguda-Oluwoa, A. A., & Onib, A. (2017). Impact of self-esteem and marital status on the desire to attain economic empowerment among women in South West, Nigeria. Sociology and Social Work Review 1/2017. http://globalresearchpublishing.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Impact-of-self-esteem-and-marital-status-on-the-desire-to-attain-economic-empowerment-among-women-in-South-West-Nigeria.pdf

- Allen, A. (1999). The power of feminist theory: Domination, resistance, solidarity. Westview Press.

- Anderson, S., & Sriram, V. (2019). Moving beyond sisyphus in agriculture R&D to be climate smart and not gender blind. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 3, 84. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00084

- Angel-Urdinola, D., & Wodon, Q. (2010). Income generation and intra-household decision making: A gender analysis for Nigeria. In World Bank. Gender disparities in Africa’s labor market. (pp. 381–406.) World Bank. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/27738/

- Badstue, L., Petesch, P., Feldman, S. L., Prain, G., Elias, M., & Kantor, P. (2018). Qualitative, comparative and collaborative research at large scale: an introduction to GENNOVATE. Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security, 3(1), 1–27. https://agrigender.net/views/collaborative-research-at-large-scale-an-introduction-to-GENNOVATE-JGAFS-312018-1.php

- Cole, S. M., Kantor, P., Sarapura, S., & Rajaratnam, S. (2014). Gender transformative approaches to address inequalities in food, nutrition, and economic outcomes in aquatic agricultural systems in low-income countries. CRP AAS. Program Working Paper: AAS-2014-42. https://www.worldfishcenter.org/content/gender-transformative-approaches-address-inequalities-food-nutrition-and-economic-outcomes-0

- Cornwall, A. (2016). Women’s empowerment: What works? Journal of International Development, 28(3), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3210

- Dillon, A., & Quinones, E. J. (2009). Gender differentiated asset dynamics in northern Nigeria. Background paper prepared for Food and Agricultural Organization (2010) State of Food and Agriculture. FAO.

- Elias, M., Ranieri, J., Petesch, P., Kennedy, G. (2018). Using vignettes to explore gender dimensions of household food security and nutrition. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329399589_Using_vignettes_to_explore_gender_dimensions_of_household_food_security_and_nutrition/citation/download

- Enete, A. A., Amusa, T. A. (2010). Determinants of women’s contribution to farming decisions in cocoa based agro-forestry households of Ekiti State, Nigeria. Field Actions Science Reports [Online], 4. http://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/396

- Ezumah, N. N., & Di Domenico, C. M. (1995). Enhancing the role of women in crop production: A case study of Igbo women in Nigeria. World Development, 23(10), 1731–1744. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(95)00075-N

- Farnworth, C. R. (2007). Achieving respondent-led research in Madagascar. Gender & Development, 15(2), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070701391482

- Farnworth, C. R., Badstue, L., & Cole, S. M. (2020). Engaging men in gender-equitable practices in maize in sub-Saharan Africa. GENNOVATE resources for scientists and research teams. CDMX, Mexico: CIMMYT.

- Farnworth, C. R., Jafry, T., Rahman, S., & Badstue, L. (2020). Leaving no one behind: how women seize control of wheat–maize technologies in Bangladesh. Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue Canadienne D'études du Développement, 41(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2019.1650332

- Farnworth, C. R., Stirling, C. M., Chinyophiro, A., Namakhoma, A., & Morahan, R. (2018). Exploring the potential of household methodologies to strengthen gender equality and improve smallholder livelihoods: research in Malawi in maize-based systems. Journal of Arid Environments, 149, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2017.10.009

- Farnworth, C. R., Stirling, C. M., Sapkota, T., Jat, M. L., Misiko, M., & Attwood, S. (2017). Gender and inorganic nitrogen: the implications of moving towards a more balanced use in the tropics. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability (Sustainability), 15(2), 136–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2017.1295343

- Farnworth, C. R., Choudhary, A., Kantor, P., & Sultana, N. (2016). Gender relations and improved technologies in small household ponds in Bangladesh: rolling out novel learning approaches. In gender in aquaculture and fisheries: The long journey to equality. Asian Fisheries Science Special Issue, 29S (2016), 161–178.

- Feldman, S. (2018). Feminist science and epistemologies: Key issues central to GENNOVATE’s research program. GENNOVATE resources for scientists and research teams. CIMMYT. https://gennovate.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/FEMINIST_SCIENCE_AND_EPISTEMOLOGIES_Gennovate_Tool.pdf

- Forsythe, L., Posthumus, H., & Martin, A. (2016). A crop of one’s own? Women’s experiences of cassava commercialization in Nigeria and Malawi. Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security, 1 (2), 110–128. https://doi.org/10.19268/JGAFS.122016.6

- Galié, A., & Farnworth, C. R. (2019). Power through: a new concept in the empowerment discourse. Global Food Security, 21, 13–17. https://authors.elsevier.com/sd/article/S2211912418301299

- Gaya, H. I., Tegbaru, A., Bamire, A. S., Abdoulaye, T., & Kehinde, A. D. (2017). Gender differentials and adoption of drought tolerant maize varieties among farmers in northern Nigeria. European Journal of Business and Management, 9(5). https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/EJBM/article/view/35330/36352

- Iruonagbe, C. (2009). Patriarchy and women's agricultural production in rural Nigeria. Journal of Cultural Studies, 2, 207–222.

- Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change, 30(3), 435–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125

- Kandiyoti, D. (1988). Bargaining with patriarchy. Gender and Society, 2(3), 274–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124388002003004

- Kant, I. (1983). Grounding for the metaphysics of morals. In I. Kant (Ed.), Ethical philosophy, (James W. Ellington, Trans). Hackett. (Originally published 1785.)

- Manda, J., & Mvumi, B. M. (2010). Gender relations in household grain storage management and marketing: The case of Binga District, Zimbabwe. Agriculture and Human Values, 27(1), 85–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-008-9171-8

- Munro, A., Bereket, K., Tarazona-Gomez, M., Verschoor, A. (2010). The lion’s share. An experimental analysis of polygamy in Northern Nigeria. GRIPS Discussion Papers 10-27, National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228321153_The_Lion's_Share_An_Experimental_Analysis_of_Polygamy_in_Northern_Nigeria

- Mutenje, M., Farnworth, C. R., Stirling, C. M., Thierfelder, W. C., Mupangwa, W., & Nyagumbo, I. (2019). A cost-benefit analysis of climate-smart agriculture options in Southern Africa: balancing gender and technology. Ecological Economics, 163, 126–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2018.1557315

- Nussbaum, M., & Sen, A. (1993). Introduction. In M. Nussbaum and A. Sen (Eds.). The quality of life. Clarendon Press.

- Obidiegwu, J. E., & Akpabio, E. M. (2017). The geography of yam cultivation in southern Nigeria: Exploring its social meanings and cultural functions. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 4(1), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jef.2017.02.004

- Olaosebikan, O., Abdulrazaq, B., Owoade, D., Ogunade, A., Aina, O., Ilona, P., Muheebwa, A., Teeken, B., Iluebbey, P., Kulakow, P., Bakare, M., & Parkes, E. (2019). Gender-based constraints affecting biofortified cassava production, processing and marketing among men and women adopters in Oyo and Benue States, Nigeria. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology, 105, 17–27. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0885576518300456

- Oseni, G., Corral, P., Goldstein, M., & Winters, P. (2015). Explaining gender differentials in agricultural production in Nigeria. Agricultural Economics, 46(3), 285–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12166

- O'Sullivan, M., Rao, A., Banerjee, R., Gulati, K., & Vinez, M. (2014). Levelling the field: Improving opportunities for women farmers in Africa (English). World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/579161468007198488/Levelling-the-field-improving-opportunities-for-women-farmers-in-Africa

- Oyerinde, V. O. (2008). Potentials of common property resources in a Nigerian rainforest ecosystem: An antidote to rural poverty among women. A paper presented at the Governing Shared Resources: Connecting local experience to global challenges, the Twelfth Biennial Conference of the International Association for the study of Commons. Cheltenham England. https://iasc-commons.org/conferences-global/

- Oyinbo, O., Chamberlin, J., Vanlauwe, B., Vranken, L., Kamara, A., Craufurd, P., & Maertens, M. (2018). Farmers’ preferences for site-specific extension services: Evidence from a choice experiment in Nigeria. Bio-economics Working Paper Series Working Paper 2018/4. file:///C:/Users/Anwender/Downloads/BioeconWP_2018_04_submitted.pdf

- Pansardi, P. (2012). Power to and power over: two distinct concepts of power? Journal of Political Power, 5(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2012.658278

- Peterman, A., Quisumbing, A., Behrman, J., & Nkonya, E. (2011). Understanding the complexities surrounding gender differences in agricultural productivity in Nigeria and Uganda. Journal of Development Studies, 47(10), 1482–1509. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2010.536222

- Petesch, P. (2018). Ladder of Life: Qualitative data collection tool to understand local perceptions of poverty dynamics. GENNOVATE resources for scientists and research teams. CIMMYT. http://gender.cgiar.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Ladder-of-Life-Gennovate.pdf

- Petesch, P., & Bullock, R. (2018). Ladder of Power and Freedom: Qualitative data collection tool to understand local perceptions of agency and decision-making. GENNOVATE resources for scientists and research teams. CIMMYT. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/92128

- Petesch, P., Badstue, L., Camfield, L., Feldman, S., Prain, G., & Kantor, P. (2018). Qualitative, comparative and collaborative research at large scale: The GENNOVATE field methodology. Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security, 3, 28–53. https://agrigender.net/views/the-GENNOVATE-field-methodology-JGAFS-312018-2.php

- Petesch, P., Badstue, L., Williams, G., Farnworth, C., & Umantseva, A. (2017). Gender and innovation processes in maize-based systems. GENNOVATE Report to the CGIAR Research Program on Maize. GENNOVATE Research Paper. CIMMYT.

- Richter, G. (2016). Inheriting Walter Benjamin. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Risseeuw, C. (2005). Bourdieu, power and resistance: Gender transformation in Sri Lanka. In D. Robbins (Ed.). Sage masters of modern social thought: Pierre Bourdieu, 93–112. London/New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Rowlands, J. (1997). Questioning empowerment: Working with women in Honduras. Oxfam. https://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/questioning-empowerment-working-with-women-in-honduras-121185

- Sachs, W., & Santarius, T. (2007). Fair future: Resource conflicts, security, and global justice. Zed Books.

- Sen, G. (1997). Empowerment as an Approach to Poverty, Working Paper Series 97.07. Background paper for the UNDP Human Development Report. UNDP.

- Shaw, G. B. (2008). 1903) Man and Superman. Maxims for Revolutionists. https://www.sandroid.org/GutenMark/wasftp.GutenMark/MarkedTexts/mands10.pdf

- SOFA (2011). The role of women in agriculture. ESA working paper no. 11-02, Agriculture Development Economics Division, FAO, Rome. http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/am307e/am307e00.pdf.