Abstract

Informal milk trading in peri-urban Nairobi plays a key role in supporting both livelihoods and nutrition, particularly among poor households. Gender dynamics affect who is involved in and benefits from milk trading. To better understand gendered constraints and opportunities in informal, peri-urban dairy marketing, a qualitative study was conducted in 2017 with 45 men and 50 women milk traders in Dagoretti, a peri-urban area of Nairobi, Kenya. The findings show that milk trading is more lucrative for older men than for women and younger men among the respondents. This article illustrates the differences between these women’s and men’s experiences as milk traders and explores the reasons behind these differences. It discusses the implications of the findings for agricultural research and development interventions that aim to enhance the sustainability and equity of the dairy sector.

Keywords:

Introduction

Poor women farmers, traders, and consumers in many low and middle-income countries rely largely on informal markets to sell and purchase food (van Veenhuizen, Citation2006). Yet, little is known about the potential of these informal agri-food markets as a source of employment for women (Rubin & Manfre, Citation2014) and, consequently, on best approaches to support them in such enterprises. In dairy, anecdotal evidence indicates that while informal milk sales constitute a unique business opportunity (and an important source of income) for poor women because of the limited financial input required, women struggle to stay in the business.

Considerable debate exists on how to improve the gender responsiveness of agricultural research for development projects. Herein, we contribute new perspectives to this debate by conducting qualitative research on the gender-specific opportunities and constraints experienced by traders in the informal milk sector of the dairy value chain in peri-urban Nairobi, Kenya, where informal milk trading is pursued by both women and men. The findings informed the development of an intervention to enhance urban milk safety and nutrition by MoreMilk – an ILRI-led project that this study is part of. In this article, we discuss potential approaches that can be used to address the identified gendered constraints and opportunities in order to enhance the potential of informal dairy marketing as a source of employment for women. The findings can contribute to supporting the equity and sustainability of Kenya’s peri-urban milk markets. They can also contribute to a better understanding of the gendered aspects of milk markets in sub-Saharan Africa, where women face constraints like the ones identified in this study.

In this article, we first review the literature on key concepts and issues in gender-sensitive value chain analysis and informal milk trading in peri-urban Nairobi. We introduce the MoreMilk trader intervention, which this study is designed to inform, followed by the study methodology. We then present the findings according to the key constraints to milk trading that emerged and use these findings to develop a framework that informs the MoreMilk trader intervention. We conclude with considerations on developing interventions based on gender accommodative or transformative approaches.

Background: literature review and the MoreMilk study

Gender analysis of agriculture value chains

Gender analysis of value chains examines how men and women experience unequal costs and benefits as products or services move from production to processing, marketing, consumption, and disposal in a globalized food system (Rubin & Manfre, Citation2014). In the context of agriculture-based policies and development interventions, upgrading agricultural value chains (e.g., making value chain actors more competitive by reducing their costs, improving efficiency, and/or enhancing product distinctiveness) is a means of promoting pro-poor economic and social progress by enhancing the efficiency of production and marketing and thereby the “value” of products and the “benefits” accrued (Stoian et al., Citation2018). Applying a gender lens to value chain analysis helps to identify how gender-based opportunities and constraints and systems of gender relations affect how women and men participate in and benefit from value chains (Farnworth et al., Citation2015).

Gender-based barriers affect market participation in various ways. Gender norms often assign non-remunerated activities, such as domestic work, to women, which reduces women’s time and energy to generate income through value chains (Elson, Citation1999). Women often have limited access to and control over assets relative to men, which limits their capacity to engage in more profitable activities within a value chain and in more lucrative value chains (Quisumbing et al., Citation2015). Policies regulating property ownership, labor codes, and service provision, among others, can undermine women’s ability to, for example, own collateral to secure business loans, take advantage of job opportunities, and access agriculture inputs and services (Coles & Mitchell, Citation2010). Finally, technologies are often developed based on the needs and preferences of men, which may limit women’s ability to upgrade their activities in value chains (Farnworth et al., Citation2015). For example, regulations in Kenya require milk traders to use large metal milk containers, which are more hygienic than plastic ones. These containers are often too heavy for women to carry, limiting their ability to transport large quantities of milk.

Gender analysis also reveals how value chain development changes gender roles and dynamics toward gender equity and enhanced value chain competitiveness (Rubin & Manfre, Citation2014). Evidence of this can be found in research on livestock intensification and dairy marketing interventions which have been shown to decrease women’s control over milk in favor of men, and increase women’s workload (Njuki et al., Citation2016). Such outcomes hinder progress toward gender equality and lead women to disengage from raising livestock, undermining the intervention’s potential (Tavenner et al., Citation2018).

Much of the debate about development interventions that respond to gender-based constraints and opportunities in the food system is on whether accommodative or transformative gender approaches are preferred (Stoian et al., Citation2018). Gender-accommodative approaches, a type of gender-responsive intervention, recognize and respond to the specific needs and realities of men and women, based on their existing roles and responsibilities as shaped by existing social and economic structures. Accommodative approaches do not question the systemic barriers in a context. In contrast, gender-transformative approaches aim to catalyze social change by addressing norms that constrict a particular group. A transformative intervention, for example, leverages existing norms that are conducive to gender equality while engaging with communities to question norms that may limit progress on gender equality (Galiè & Kantor, Citation2016). With increased attention to gender in agricultural research for development, a new challenge is to determine the relative benefits of using gender accommodative or gender transformative approaches for the effectiveness of development interventions and policies, an issue that we address in the discussion section.

Informal milk trading in peri-urban Nairobi

Kenya is one of the largest milk producers in Africa, with most milk produced by smallholders and more than 70% sold in the informal market (Roesel & Grace, Citation2014). “Informal markets” in low- and middle-income countries are defined as those in which small-scale traders operate, often without licenses, generally escaping regulation, using traditional processing practices, and often motivated by short-term income generation (Roesel & Grace, Citation2014). In this study, “informal milk markets” refers to the buying and selling of milk that does not undergo pasteurization in industrial plants. Many of the traders use traditional handling and processing practices, such as boiling milk and often do not fully comply with dairy sector regulations.

In Kenya, like in many countries, the informal milk sector supports the nutrition and livelihoods of rural and peri-urban poor households through two main pathways:

Milk provides essential nutrients to consumers. Consumption of safe milk has been found to improve anthropometrics, cognitive function, and nutritional deficits among children (Willett et al., Citation2019). Malnutrition is high in Kenya (34% stunted) and concentrated in poorer areas (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, ICF International, Citation2014). Poor households in Nairobi spend 38% of their food expenditures on animal source foods, of which 37% is spent on dairy products (14% of total food expenditures) (Mtimet et al., Citation2015). Most households rely on the informal sector to source milk. This milk is often raw or contaminated with pathogenic microorganisms that cause diarrhea, thereby decreasing the ability of the body to absorb nutrients and yielding negative health consequences despite the nutritional value of milk.

Milk trading can be a livelihood strategy and source of income for both women and men (MoLD, Citation2010). In Kenya, informal milk markets contribute to the livelihoods of approximately 600,000 farm households and 365,000 trader households (Roesel & Grace, Citation2014). Women represent approximately 45% of informal milk traders in peri-urban Kenya (Mutavi et al., Citation2016). Yet, little is known about the gendered constraints faced by milk traders and the gendered opportunities for income and upgrading that peri-urban milk trading offers.

The MoreMilk project and this study

“MoreMilk: Making the most of milk” (MoreMilk) is a 5-year project that aims to enhance milk safety and child nutrition in peri-urban Nairobi. It is led by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in collaboration with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), and other partners such as the KDB. One component of MoreMilk focuses on training milk retailers to increase hygienic milk handling and business practices. Hygienic milk-handling practices have the potential to enhance milk safety and the nutritional status of consumers (McDermott et al., Citation2015), as well as support the businesses and livelihoods of milk traders (Rademaker et al., Citation2015). Supporting these businesses is important for the longer-term sustainability of the intervention: anecdotal evidence suggests that milk trading in Nairobi has a high turn-over, largely a consequence of the inability of operators to grow their businesses, which could reduce the longevity of the impact of training retailers.

Additional anecdotal evidence from an ILRI project in 2000 showed that, while both male and female milk traders experienced many of the same benefits and challenges in the sector, women felt disadvantaged by limited access to credit and negotiation power with milk distributors relative to their male counterparts (Alonso et al., Citation2018). We undertook this study to research the gender dimensions of milk trading in peri-urban Nairobi. The study addressed the overall research question: What are the gendered opportunities and constraints in informal milk trading in peri-urban Nairobi? The insights from this study were used to inform the MoreMilk training curriculum for dairy traders to better address the constraints faced by women and men milk traders, thereby aiding both the nutritional and livelihood enhancement goals of the project.

Methodology

Our study is a qualitative, exploratory analysis of the gendered opportunities, constraints, and dynamics in informal milk trading in Dagoretti, a peri-urban area of Nairobi. The exploratory nature of the study was necessary because of the existence of anecdotal evidence on gendered constraints faced by milk traders vis-à-vis the lack of published gender analysis on the topic. Based on the preceding literature review we identified “sensitizing concepts”Footnote1 (Bowen, Citation2006) to frame our exploration of gendered constraints and opportunities in informal milk trading, such as access to and control over resources; mobility; decision-making. We then used an inductive, grounded theory approach (Collins & Stockton, Citation2018) to develop a framework based on our findings. Given the exploratory nature of our study, we engaged with a small number (small-N) of respondents that we selected purposely as the most informative on our research topic to acquire thick descriptions and deep understandings of our topics. The strategic selection of a few case studies and in-depth analysis of them can provide a larger volume of more nuanced information than most large random samples can (Mahoney & Goertz, Citation2006). We followed the principle of saturation in identifying the number of respondents. Saturation is reached when new incoming data produces little or no new information to address the research question (Given, Citation2016). We note that, with caution, that findings from small-N studies can be “extrapolated” (rather than “generalized”) to similar settings and inform development interventions subject to further testing and analysis (Donmoyer, Citation2012; Galiè, Citation2013).

In this study, we integrate three approaches that were designed to complement and sequentially build off one another. Six single-sex focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted: three with women and three with men for a total of 20 men and 22 women participants. Four of these FGDs were held with individuals currently involved in milk trading and two with former traders. Emerging themes were used to refine the discussion guides used in the semi-structured individual interviews (SSIIs), which were held with 22 men and 27 women. Of these, 42 were currently operating as milk traders and seven were former traders who had abandoned the business. Next, preliminary hypotheses were generated and tested in four key informant interviews (KIIs) with three men and a woman who have experienced current milk traders and are members of a large trader association. We interviewed in total 38 current women traders, 12 women former traders, 34 men current traders, and 11 men former traders. A field team of six individuals – three facilitators and three note-takers – who were fluent in Swahili and English and had experience conducting qualitative research conducted all interviews in June 2017. ILRI and IFPRI researchers trained the facilitators and notetakers, were present in all FGDs, and selected SSIIs and KIIs, and also reviewed the notes taken on the same day to ensure their quality and facilitate discussion among team members about the emerging findings.

Recruitment of participants

Recruitment of FGDs and SSIIs participants sought to maximize variation and capture a broad range of trader experiences. We broadly identify those that we recruited as “traders,” because the different trader roles that men and women take in the milk value chain were not yet clear to us at the start of recruitment (see ).

The selection criteria were identified in consultation with ILRI experts on the Kenya dairy sector. To ensure that the FGDs involved different types of milk traders, we recruited individuals with a range of characteristics, including having a license to sell milk (or not having one); operators of different types of business (shop, sell without premises); those with different sources of milk (own farm, neighbors); traders who left the sector (former traders) (see and for details). The latter group was considered key in providing information on constraints retailers may face – that force them to exit the business. All participants were (or had been) traders or owners of a retail milk business (not employees selling milk on someone’s behalf). While ethnicity is an important characteristic in Kenya, we did not collect this information because of ethnic tensions at the time of fieldwork.

Table 1. Sampling framework for focus group discussions.

Table 2. Sampling framework for semi-structured individual interviews.

FGD and SSII participants were identified by a facilitator from ILRI through recruitment of retailers located in visible places – including mobile traders met on the streets – and subsequent snowball sampling. We recruited traders who satisfied the selection criteria until we obtained a balance of participants with different characteristics ( and ) and we reached saturation of responses (Nelson, Citation2017). SSII participants were also identified during FGDs as individuals who provided more detail or different views relative to other participants. The KII participants were identified based on their ability to provide an overview of the informal milk sector in peri-urban Nairobi. All four had long-term experience in milk trading and two of them were also senior members of the dairy traders’ association ().

Table 3. Sampling framework for key informant interviews.

Content of discussions and interviews

Because of the exploratory nature of our study, we developed open-ended semi-structured questions focused on broad topics related to retail, which included “opportunities in milk trading;” “constraints faced;” “decision-making patterns,” to guide FGDs, SSIIs, and KIIs. These topics provided a loose framework on potentially important issues for gender analysis in milk retail while allowing participants to freely discuss what they thought was relevant under each topic.

FGDs explored the overall research question in a group setting to allow different opinions to be expressed and discussed simultaneously. Questions focused on: (1) opportunities offered by dairy trading (compared to other businesses); (2) obstacles to becoming and being a milk trader; (3) obstacles to improving the business; and (4) satisfaction with the milk business. Questions specific to characteristics of the group (e.g., women or men, current or former traders) were also asked. For example, we asked women whether they felt women traders faced constraints that were different from those experienced by men (and about men’s constraints in the men’s groups), and we asked former retailers why they had left the business. The six FGDs took place in a private room of a public cafeteria in Dagoretti.

The key issues that emerged from the FGDs were used to refine some of the questions developed for the SSIIs. SSIIs took place at each milk trader’s business to allow them to continue serving clients while being interviewed.Footnote2 In cases when the vendor preferred to not undertake interviews at their premises, SSIIs occurred in a nearby cafeteria. SSIIs focused more on individual experiences related to milk trading in (1) intra-household decision making; (2) access to productive capital; (3) access to financial services; (4) relationship with other actors in the milk value chain; (5) involvement in community groups for the milk value chain; and (6) gender norms affecting one’s involvement in milk trading. Some clear patterns about gendered involvement and constraints in the milk value chain emerged during the FGDs and were confirmed recurrently during the 49 SSIIs.

We conducted an initial validation of these patterns with four key informants. We developed an additional set of KII questions to assess the validity of our identified patterns and to elicit more details. The four KIIs took place at local cafeterias in Dagoretti. KII questions asked about: (1) the roles in the value chain commonly filled by women and men and why; (2) how women and men upgraded their milk business; (3) other, non-milk business opportunities for women and men; and (4) access to financial services. The iterative approach to conducting FGDs, SSIIs, and finally KIIs ensured emerging themes stemming from retailers’ distinct experiences could be fully explored and documented.

Data analysis

The interviews were recorded to ensure completeness of the information and transcribed and translated from Swahili to English by two professional translators. The transcripts were uploaded into a qualitative analysis software package (NVivo Version 11). Transcripts were coded by a team of two research analysts and two gender scientists. Coding was based on a codebook of deductive codes developed by the team. The initial version was based on key themes from our research questions and team discussions during fieldwork. Open coding, in which common themes are identified and assigned codes, was used, which allowed emerging themes to be captured. The team identified a set of most meaningful emerging themes for analysis. Discrepancies in the coding among the team members (such as length of text included under a code), were identified through NVivo and harmonized. The data were examined to identify emerging patterns among women and men. We also checked whether other social markers, such as age, education, and marital status, could explain the differences in experiences between women and men. Consensus analysis was undertaken, and patterns were synthesized and interpreted as we present next.

Results

We first describe trader roles in the informal milk value chain. We then present the characteristics of the participants and their roles along the value chain. Next, we describe the constraints and determinants of business lucrativeness. We then conclude with a section on traders’ overall satisfaction with milk trading.

Overview of informal milk trading

Women and men mentioned four different roles that actors assume in trading along the milk value chain in peri-urban Nairobi, from production to retailing: producers; brokers, who buy from producers and sell in bulk to retailers or distributors; distributors, who buy bulk quantities from brokers and sell to retailers; and retailers, who sell milk to consumers for daily useFootnote3 (see ). Retailers sold milk from six main types of retail locations. Small shops sell milk alongside basic commodities, such as sugar, soap, oil, eggs, bread, and often employ one or two assistants. Large shops sell milk and a larger variety of commodities, often with several employees (e.g., a small supermarket). A milk bar is a small retail outlet that sells only milk and is often found roadside. An “ATM” is used in Nairobi to indicate premises where a vendor sells refrigerated milk that is dispensed through a machine that resembles an ATM that dispenses money. Some ATMs are found inside shops, but ATM-only premises are also common. Finally, some milk retailers sell their milk roadside (street vendor) with no premises or sell to passersby or door-to-door (mobile vendor). provides an overview of the different roles in the milk trading value chain, the type of retail in which they were involved, their role in the retail business, and the type of premises.

Table 4. Overview of the milk trading value chain.

Description of participants

The women who participated in FGDs, SSIIs, and KIIs, and were at the time of the interview, involved in selling milk, were an average of 36 years old and, mostly, did not have a license to sell dairy products (14 licensed and 24 not licensed), were married (29 married, eight single), were retailers (33 retailer, four producers and retailers, and one broker), sold both unpacked (or informal) and packed milk (everyone sold unpacked milk – as per selection criteria; some mentioned occasionally adding packed milkFootnote4 to the products they sold; a few always sold both),Footnote5 sold from rented premises (23 rented and one owned their premises), had a small shop (21 had a small shop, seven sold on the street with no premises, four had milk bars, four had ATMs, one sold from her farm), sold milk alongside other commodities (22 sold milk alongside other commodities while 14 sold only milk), sold an average of 33.8 liters of milk daily (range of 1–250 liters – the latter, a key informant who sold from a milk ATM), and sourced milk mainly by having it delivered to their shops by brokers or through dairy cooperatives (20 sourced from brokers, six from dairy cooperatives, four from own farm, eight received milk from a mixture of these sources) (). The women who were formerly milk traders (not currently in the business) differed from active traders mostly in terms of their role in the value chain. Former traders had mostly been brokers and mostly sourced milk directly from producers (see discussion next for an interpretation of these characteristics).

Table 5. Characteristics of participants in focus group discussions and semi-structured interviews.

For some characteristics, men and women who were current traders were similar. Participant men were on average 37 years old, were mostly married (26 were married, eight were single), sold mostly from rented premises (17 rented and two owned their premises), and sold mostly from small shops (nine sold from small shops and four from large shops). These men differed from current women retailers in that their businesses focused more exclusively on milk (15 sold milk with other commodities and 14 sold milk only), sold unpacked (informal) milk more than packed milk, and were mostly licensed (24 were licensed and 10 were not). They sold, on average, 132 liters of milk daily (with a range of less than 10–1000 liters – the latter quantity sold by a key informant with a large shop). They mostly sourced their milk directly from producers (16 sourced from producers only, 8 from brokers, 4 from their own farm, and the remaining 6 sourced from a mixture of these sources) and were involved in milk trading in various capacities as traders, distributors, brokers or any combination of these roles ().

Constraints and determinants of lucrativeness in milk retail

Milk trading was considered by all participants to be a viable business opportunity for poor women and men in peri-urban Nairobi, because of the low initial capital investment needed to start a business (as low as US$1), and because milk is sold daily, yields cash readily, and can offer quick returns on a relatively small investment. Both men and women participants mentioned two major constraints: “milk spoilage” and “fluctuations in milk supply” (mostly in the dry season – December to February – when pasture for cows is scarce, milk productivity is low, and demand is high because of religious festivities). Only women frequently mentioned “high purchase prices” as a constraint, which relates directly to reduced milk availability. Further discussions with the participants revealed gendered differences in these constraints, the severity of these constraints, and the implications these constraints had for their businesses, which are elaborated next.

All participants agreed that milk trading is lucrative under certain conditions; men and women had different experiences meeting these conditions. First, participants explained that low purchasing prices are important, because the retailing price of milk in peri-urban areas is uniform across retailers (although prices fluctuate seasonally), and sourcing milk at lower prices is the main way to increase profit margins. Men and women participants explained that more remote producers provided cheaper prices. Thus, where milk is sourced, and the gender dynamics affecting access to these sources of milk, emerged as factors influencing the profitability of the milk retail business. Second, participants explained that selling milk in large quantities is important for lucrative milk business, because the profit per liter of milk is small (between US$0.03 and US$0.05), and retailers can only accumulate significant earnings by selling larger quantities. Third, milk quality and safety were considered important, because low-quality milk accelerates milk spoilage, which entails a loss of both the investment to purchase the milk and the potential earning from the lost sale.

Sources of milk and purchasing prices

Whereas most men and women stated that sourcing milk directly from producers was a key determinant of higher profits, it was primarily older men (older than 30 years) who sourced milk from producers. Most women and younger men, instead, sourced milk from brokers and distributors. Out of the eight men who sourced from brokers, seven were young men (average of 24 years old) who had only been in business for a couple of months and had not established good sourcing networks. Two had very large shops in which milk was not a priority commodity, making it not worth it for them to travel far to source milk from producers, they argued. Another was a distributor who, by nature of his job, sourced milk from a broker and distributed it in Nairobi. Sourcing milk from brokers translated to higher purchasing prices and lower milk quality, according to participants.

When asked why they did not source directly from producers, women referred to gender norms that limit their freedom of movement, such as those that prevent them from using private motorbikes at any time of day or public transportation during pre-dawn hours when milk is commonly sourced, and those that discourage them from interacting with men outside their families. Also, both women and men explained that women’s ability to source milk was limited by time constraints: women are customarily in charge of preparing breakfast and readying children for school during the time when one would need to source milk. Of the four women who sourced milk directly from producers, three operated their business with their husbands (who were in charge of milk sourcing) and one lived near a milk producer. One woman also emphasized the influence of reputational concerns on women’s freedom of movement. She explained, “Married women fear travelling far, because the husband may feel that you have gone for other issues that are not business-related.” (SSII, woman, June 2017).

Most women agreed that unmarried women could move around more easily than married women, because unmarried women are less constrained by household chores, children, and their husband’s control. All participants also mentioned women’s physical challenges in handling the weight of metal containers filled with milk (as compared to men) and how this made it more difficult for women to source and transport milk. A woman milk retailer explained:

The main limitation [to a prosperous business] is the source of milk being far and not easily accessible to women. Men can use motorbikes and bicycles to travel to the source. Also, the 50-litre aluminium cans that are used to transport milk are very heavy for women. (KII, woman, June 2017)

Because of these factors, many women sourced their milk solely through brokers and distributors, who delivered milk to their businesses, and bought it at higher prices than when purchasing from producers directly. Alternatively, some women hired men to source milk from producers for them, increasing their costs relative to men retailers who could transport milk themselves. These costlier options drive lower profit margins for women relative to men, who can more easily source from producers directly.

Notably, all participants in the FGD of former women milk traders once sourced their milk from producers directly. While this may be the result of purposive (non-random) sampling and a small sample, it nonetheless offers insight into the experiences of women who broke barriers that generally restrict women from sourcing milk directly from producers. These participants quit their businesses, they explained, because using public transport to carry the milk from the producers to urban areas meant waiting on the roadside for the matatu (small bus for public transportation), greater exposure to authorities who enforced the dairy industry rules and regulations, and higher transaction costs: lengthy roadside-waits meant that milk could spoil faster, they explained. Also, it made them feel unsafe. Traveling by matatu also meant that these women had to use smaller containers that fit in the matatu. These smaller containers are plastic and do not comply with health regulations, thereby exposing women to the risk of costly fines.

The overall amount of milk women traded was low because of the restricted space in matatus and because of their limited physical strength. The women argued that they were disadvantaged compared to men who could use private transport to carry dairy board approved containers that were made of metal, significantly larger, and able to hold larger quantities of milk. Additionally, women argued that their transaction costs were higher relative to men because the cost of using one’s own transportation, as men do, is lower compared to using public transport – an option that is not readily available to women, because of the required capital. Yet, using public transport was cheaper than hiring men to transport milk. The women added that it was scarier for women to face the authorities than for men because women felt physically vulnerable.

Finally, despite these women being able to travel to source milk from producers, they could only travel to nearby areas. They typically could not spend the evening or night outside their home, as men can, and could not reach faraway producers who offered better prices. Limits on their freedom of movement reduced their profits relative to men, who could travel to faraway producers. Although these women broke gender-based norms on freedom of movement by using public transportation during pre-dawn hours or by traveling to rural areas, their freedom of movement was still limited by other gender-based constraints – whether norms or safety concerns – that discouraged these women from spending the night away from home to reach their cheaper milk providers.

In the FGD of men former traders, participants had been brokers and retailers. Most had incurred debts they could not repay, which ultimately caused them to quit. They reported two main reasons for incurring these debts: (1) financial losses caused by authorities who harassed them and confiscated their milk and (2) poor quality milk that trapped retailers between customers asking for compensation and producers denying responsibility and refusing to reimburse them. The men who worked as brokers reported that authorities harassed them and confiscated their milk, because they failed to comply with regulations for uniforms, including safety-specific clothes to wear while driving motorbikes and hygienic-specific clothes to wear when handling the milk. This was logistically challenging for these brokers, as their job entailed continuously switching between driving and delivering milk. Women former traders did not mention “confiscated milk” as a constraint, possibly because men dealt with large quantities (compared to women) and incurred larger financial losses from confiscation compared to women who transported smaller quantities.

Roles in the milk-trading value chain and volumes of milk sold

Selling large volumes of milk was considered necessary for a business to be lucrative because the profit per liter of milk is low (between US$0.03 and US$0.05). The volume of milk sold was affected by the role along the value chain and the type of retail establishment (). Because they enjoy greater freedom of movement, as discussed earlier, men may occupy any of the milk trading roles and often combine them, for example, broker and distributor, distributor and retailer. Men were, therefore, able to participate in more nodes of the value chain and have more lucrative experiences, overall, relative to women in the dairy sector. They were also better positioned to trade both small and large quantities to a variety of buyers – a versatile position that women do not enjoy.

In contrast to men who occupied multiple roles along the milk value chain and readily handled large quantities of milk, women generally only occupied the final node by selling directly to consumers as retailers. All participants referred to women’s engagement with household chores and safety to explain why women were retailers only. Women and men frequently brought forward another reason why retailers were more commonly women. They believed that women have a natural inclination toward cleanliness and gentleness (qualities that participants assumed men do not possess), which are necessary to sell milk to customers.

Some women and men argued that married women faced more difficulties in milk trading relative to unmarried women. As was the case for freedom of movement, social norms dictate that married women have more household chores and family responsibilities relative to their husbands, which prevented them from engaging in business as extensively. One woman argued that married women enjoyed more safety in their shops than unmarried women because the former could discourage inappropriate treatment from male customers by mentioning her husband. At the same time, according to the same participant, when these same norms about appropriate interactions between a married woman and an unrelated man are taken seriously, they are a burden to the business:

See this hotel?Footnote6 The lady who used to work there was married. Her husband had put up the hotel for her. It was a very classic hotel with everything, even a TV. But despite her efforts, at the end of the day she couldn’t even cover for rent. That is because everyone would say she is married and can’t interact with her customers. I once went there. The lady was so busy with her family that she did not interact with men: she was protecting her marriage. (SSII, woman, June 2017)

The range of experiences shown in these findings indicates that social norms around behavior for women exist on a continuum that results from balancing norms establishing women’s “appropriate behaviors,” as single or married when interacting with unrelated men and doing domestic chores. Men do not appear to be constrained in a similar way.

Milk quality and spoilage

Men’s ability to access milk directly from producers also reduced their chance of receiving milk that was spoiled, adulterated (e.g., by being watered-down and augmented with margarine) or contaminated (e.g., via non-hygienic containers) as compared to those who received milk from brokers or distributors. Milk quality is important because receiving low-quality milk from producers, brokers, or distributors exposes retailers to the risk of milk spoilage, which represents a loss, both the money invested (if the milk provider does not reimburse) and the potential earnings (lost opportunity to sell). Most men and women participants also mentioned that receiving low-quality or unsafe milk, which goes bad quickly, often results in the loss of customers who either inadvertently bought spoiled milk from the shop and refused to purchase from the same retailer again or chose to shop elsewhere after realizing that the milk they were about to purchase was spoiled. In other words, adulterated or contaminated milk might still be sold, but retailers – often unwittingly – face the risk of tarnishing their reputations.

Women and young men retailers who received milk delivered to their shops reported experiencing more milk losses than those, predominantly more experienced men, who sourced directly from producers. This happened possibly because of the higher number of intermediaries involved in the delivery to these retailers (as compared to the shopkeepers who sourced directly from producers) and longer delivery time, which increase the chances of milk adulteration, contamination, and therefore spoilage. Because women and young men were less able to source milk from producers directly, milk spoilage and adulteration were major problems that often forced them to close their businesses. As one woman explained:

If I had the opportunity or knew where farmers are, I would be going to the farmers myself to collect milk, because those who supply us with milk adulterate it by putting either water or margarine, which makes it look good, yet it is of poor quality. (SSII woman, June 2017).

All participants mentioned an additional issue that negatively affected women’s milk retailers: a widespread belief that lactating women would spoil the milk by mixing it with their own breast milk. All women participants reported having to close the business while they were breastfeeding their children. Some women did not go back to their business for years, because they perceived that customers did not trust the cleanliness of their premises when the children were present during business hours. All participants, men and women alike, confirmed that children should not be seen at milk selling premises, because customers would think children dirtied containers and milk. Customers would also blame the shopkeeper if the milk went bad, and brokers or distributors would not take responsibility for the spoiled milk they delivered if children were around the premises. Consequently, women with children incurred heavy losses; men did not incur such losses, because gender norms exclude them from serving as the primary caregiver to their children. Some of the women who sold milk alongside other commodities declared that they had stopped selling unpacked (informal) milk and started selling packed milk from the formal dairy sector. Packed milk was replaced by the provider company when spoiled, free of charge. Profit margins with packed milk, however, were extremely low, because packed milk is much more expensive to purchase than unpacked milk.

Financial endowments and resilience

Financial resilience, although not mentioned among the main constraints listed by participants, emerged during the discussions as an important aspect of retailers’ business sustainability. Women seemed to be less financially resilient to milk losses than men, a gender disparity that aggravates the financial losses from spoiled milk. The women declared that they often had to abandon their businesses after receiving spoiled milk three or four times. Men did mention the constraint of receiving spoiled milk but did not mention having to close the business consequently. Moreover, women were said to often have access to less cash than men and to control fewer assets than men. A man from the KIIs stated:

In terms of finances, men are more advantaged [than women]. To obtain a loan from a bank one must show collateral. Men have the land, which they can use to buy a vehicle for transport. Men can sell a cow or two to get a motorbike … a man owns everything including the wife. (KII, man, June 2017)

Limited access to financial services meant that women could not invest in purchasing large quantities of milk or in assets needed to enhance their business as exemplified by the type of items listed when asked what assets they would need to improve their business. All women mentioned a desire for a refrigerator, and the majority also wanted to rent a better shop that was, for example, free from mice and cleaner. Some added that they needed more cash to buy more milk and satisfy customers’ demands. Two mentioned ATMs (roughly a US$3000 investment) and two others wanted measuring cups. The men mentioned they needed to buy a motorbike (instead of renting it), an ATM, a shop (rather than rent), a car, and a refrigerator. Clearly, women’s financial aspirations were less ambitious than men’s.

Many participants explained that limited financial resources hindered the development of women’s businesses. As a former trader stated:

Men, especially in Kenya, are more into entrepreneurship than women, especially with milk. When it comes to empowerment, women are more vulnerable, and they don’t have the resources to start the business, and they also fear risking. When the milk ATMs hit the market, for example, they were costing more than 500,000 KSH (US$5,000) and women rarely can make huge investments, especially in the informal sector. … If you find a woman working in a business, it is most likely her husband’s. (KII, man, June 2017)

Satisfaction with and opportunities offered by the milk business

Finally, the study explored participants’ overall satisfaction with the milk business. Both women and men were satisfied with their work as milk traders, but for different reasons. Men were satisfied because milk trading brings money. They generally considered the business to be lucrative and worthy of investment for some years to come. Some participant men recounted personal experiences – which were common to men milk retailers – of entering the milk business, profiting, investing their earnings in other businesses, and hiring cheap labor to continue managing their milk sales while they managed other businesses. As one man stated:

I am satisfied with being a milk retailer, because the money I get from this business has helped me educate my children and construct a house for my family. I have also invested in another business – green grocery – where I sell vegetables alongside the milk business. (SSII, man, June 2017)

The men emphasized that milk retail is flexible in terms of working hours (allowing them to also do other jobs) and in terms of running it (allowing them to hire workers).

Women milk retailers also said that they were satisfied with their businesses and wished to remain engaged in the same business in 2-years’ time. However, the scope of their satisfaction seemed to result from more modest – relative to men – expectations about the benefits. For women, milk provided a limited income. Women’s profits per liter were low; the quantities they sold were low; the losses due to spoilage were high. They often closed their business when breastfeeding or caring for small children. Consequently, women explained, they rarely relied on milk as the only commodity they sold. Rather, selling milk was necessary to provide a full range of staples, such as eggs, bread, and milk, for customers. Also, selling milk provided immediate and daily returns on investment, which women used to feed their families. As one woman explained

Yes, I am satisfied with the milk business, because it provides me with the daily basic needs. [However,] milk does not have constant good profits, and that is why I am dealing with a variety of commodities in my shop. … If you decided to just sell milk alone, you won’t make it. (SSII, woman, June 2017)

Also, women found it convenient that milk – different from other commodities – is sold mostly in the morning and evening, allowing them to close when they needed to do household chores. They were satisfied with their businesses also because they lacked the financial means and the opportunities to engage in other revenue-generating alternatives; the milk business, they agreed, requires very limited initial financial investment compared to other businesses. Finally, according to a key informant, women had lower expectations about their earnings than men:

The majority [of retailers in milk trading] are women, and especially young women. Milk dispensing requires a lot of patience and commitment. Young men are actively looking for other sources of income; they may not be able to concentrate with selling milk. In terms of payment, you find a young man may reject a job where they are paid eight thousand, but a lady of the same level of education may agree to do the job for that much. (KII, man, June 2017)

Discussion

Proposed framework for this study

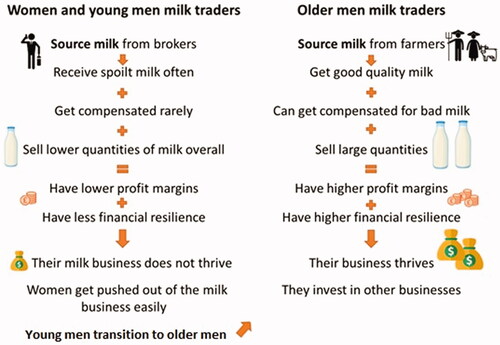

We organized our findings into a framework () that summarizes how we understand participant women and men to experience milk trading in the informal sector in peri-urban Nairobi. Three key factors emerged that increase the lucrativeness of the milk business according to the participants: (1) low purchase prices (and consequently higher profit margins); (2) selling milk in larger quantities; (3) high quality and safe milk. All three factors occur more readily when retailers source the milk directly from producers. These factors were influenced by four intersecting social markers: gender, age, marital and economic status. Education did not seem to strongly determine the experiences of our participants. Ethnicity could potentially be an important factor but was not explored due to expected sensitivities at the time of the study.

Figure 1. The gendered milk trading value chain experienced by study participants in peri-urban Nairobi (source: authors’ elaboration).

Gender

Overall, women were less likely than older men to source directly from producers, sell large quantities of milk, engage in nodes of the value chain beyond retail, and consequently, generate significant income. Young men also faced similar constraints. However, women cannot overcome these constraints as young men can, because gender norms restrict women’s freedom of movement and hold married women and mothers responsible for domestic labor. Both norms are widely documented to limit the involvement of women in business in Sub-Saharan Africa (Heckert et al., Citation2020).

Age

Younger men were less established as milk retailers than older men and faced many constraints like those faced by women. They sourced from brokers, because they had no capital to purchase or rent a vehicle to reach producers, nor had they established relationships with producers. As with women of all ages, younger men often received bad quality milk and had difficulty claiming compensation from brokers. They dealt with small quantities of milk, because of limited capital, and therefore did not find milk alone to be a source of good income. Older men had more opportunities to acquire vehicles to source and sell milk and travel to remote areas to establish relationships with producers. Slowly, men could build savings to expand their business. As women grew older, however, their opportunities did not follow a similar path; responsibilities and household chores related to marriage and children limited women’s trading opportunities, as has been documented across sub-Saharan Africa (Arora, Citation2015; Wekwete, Citation2014).

Marital status

Marital status had important implications for women: being married for women was positively contributing to their business when a woman was operating with her husbands (e.g. sharing business-related tasks); also, women mentioned leveraging "being married" to fence off inappropriate customer behavior. Being married, on the other hand, was a constraint to the business when household chores prevented women from engaging in specific business-related activities (e.g. sourcing milk from producers early in the morning) or when it restricted their freedom of movement or interaction with unrelated men based on gender norms about appropriate conduct. Men of all ages were not affected by marital status, according to our findings.

Economic status

Participants who discussed limited capital described their inability to invest in better facilities, purchase larger quantities of milk, or withstand financial losses. Because these constraints seemed most severe for women and younger men, economic status arguably intersects with gender and age. That is younger women may have the lowest economic status when compared to younger men or older women, while older men may be most well off. Limited financial assets are one of the main constraints for women’s involvement in business in Sub-Saharan Africa (Campos & Gassier, Citation2017).

provides a framework based on our key findings. It shows that the high turn-over of operators in peri-urban Nairobi’s milk value chain is gendered: for women retailers, high turn-over relates to being pushed out of business, whereas for men, it relates to entering other nodes and businesses. A larger sample is recommended to assess the relevance of our findings for Kenyan traders in informal milk trading at large.

What approaches for the MoreMilk intervention?

This gendered analysis of the milk value chain was designed to inform the development of a training curriculum for milk retailers for the MoreMilk project, which aims to be responsive to gender-based constraints and opportunities. Indeed, the findings from this study show that the success and growth of the businesses of women and men who operate in the informal milk sector are affected by gender dynamics. Moreover, the findings reveal that informal milk trading is a good income-generation opportunity for men and women, and particularly important for women who have limited alternative business opportunities in peri-urban settings, compared to men. Integrating gender considerations into the MoreMilk training is important for enhancing the project’s effectiveness and impact. Addressing the business-related constraints experienced by women and men milk retailers is likely to increase the viability and longevity of their businesses, which is likely to increase the possibility that the retailer intervention successfully improves the quality of milk being consumed and the nutritional status of their consumers. Furthermore, gender-responsive training can help progress gender equality by enhancing women’s business opportunities.

In addition to industry-specific knowledge focused on increasing milk safety and hygiene, such as the ability to assess milk quality thereby reducing the chance of spoilage, a gender-responsive training could include, for example, negotiation skills targeted to women and less-experienced men, which may enhance their ability to negotiate purchasing prices or compensation for bad milk. Also, the training could enhance women’s knowledge on accessing and managing credit, thereby addressing women’s limited financial resilience. It could also strengthen entrepreneurship by focusing on enhancing personal initiative and a proactive mindset, which has been shown to increase profits among small-scale entrepreneurs (Campos et al., Citation2017).

However, the MoreMilk intervention, along with agricultural development programs in general, face a major challenge to their attempts to promote gender equity: the potential of these interventions may be limited if the root causes of the gendered constraints are not addressed. The cases of the former women milk retailers, who had sourced milk from producers and still experienced business failures, indicate that an intervention to support women milk retailers to source their milk from producers directly may not be viable, unless some of the gender norms, such as those that prevent women from using their own transport, are addressed together with the issue of gender-based violence. Only by tackling some of these deep-rooted social norms that disadvantage women can interventions enhance the equity of the milk value chain and the sustainability of women entrepreneurs who operate in it. For example, should training interventions accept the social norm that discourages women from operating private vehicles and work around its implications, including profit margins and business sustainability, or should it rather engage in gender-transformative approaches and support gender-equitable attitudes toward women’s operation of private transport – to address the root of the constraints?

Much research designed to inform development projects may encounter these complex gender dynamics that can affect whether the intervention is successful. Yet, they may have no mandate to address them. MoreMilk, for example, was designed as a “technical” intervention to address milk safety and nutrition. Although, as these findings suggest, gender-based constraints may underlie the intervention’s capacity to bridge the gender gap, the project’s intervention was not envisioned to address gender norms, partly due to the necessity to first establish if such an intervention can have positive effects on milk safety and child nutrition.

An alternative approach would be to address some of the gendered constraints, for example, by creating a gender-responsive woman-producer to woman-vendor delivery channel. Such an intervention would need to examine whether a direct women-producer to women-vendor channel could provide producers with a reliable market for their milk, and vendors with a reliable source of milk, and under what conditions such arrangements would work along the accommodative to transformative continuum: institutional arrangements (women only or mixed cooperatives, contracting, etc.); technologies (milk processing to increase shelf life of milk; more productive breeds); creation of a social enabling environment by addressing gender-discriminating social norms (arrangements with male-led transports; support women-led transports; identification of community leaders supportive of businesswomen).

Even if MoreMilk decided to adopt gender-transformative approaches and address some of these social norms, the question remains whether they would be successful in promoting a more equitable value chain vis-à-vis complex social and gender norms. For example, even if the gender norm discouraging women from using public transport to remote areas in pre-dawn hours suddenly changed and the community supported women’s travel, gender-based constraints, such as gender-based violence, which is beyond the scope of agricultural research for a development project, may still discourage women from using public transport.

Conclusions

This study reveals key constraints faced by participant men and, especially, women milk traders in peri-urban Nairobi, sheds light on the importance of urban dairy retailing for poor women and men, and discusses potential implications for projects that, for example, aim to enhance the equity, sustainability, and safety of dairy markets. The findings show that three key factors affect the lucrativeness of the milk business according to the participants: low purchasing prices, milk sold in larger quantities, and good milk quality. Gender dynamics and norms, together with age, marital and economic status, strongly affected the ability of women and younger men to participate effectively in milk trading, develop a viable business, and earn a living from milk trading.

These findings shed light on the high turnover of milk retailers in peri-urban Nairobi. Milk retail, in the narratives of our participants, is generally a lucrative business for men who, after a few years in the business, upgrade their businesses, for example, by acquiring more expensive commercial assets, opening a new franchise location, or hiring employees. Women, however, mostly find the milk value chain less lucrative and difficult to navigate, because they are unable to fully participate due to social restrictions on their freedom of movement and customary domestic responsibilities (especially for married women). Yet, milk retail still offers a business opportunity that they value.

Because the three main constraints identified in this study as affecting the lucrativeness of the milk business for women (particularly around freedom of movement, household chores, and financial endowments) are documented in the literature to affect women entrepreneurs in other African countries, the findings may be relevant to researchers exploring gendered opportunities and constraints in milk markets beyond Kenya. These findings also prompt questions about the difficulties faced by agricultural research for development projects and policies in addressing gender norms for both effectiveness and progress toward gender equity. What level of engagement can a “technical project” like MoreMilk be expected or able to undertake to mitigate gender-discriminating norms? Additionally, how sustainable can the results of a gender-responsive intervention be if it does not address the root causes of gender discrimination? Finally, how can agricultural research for development institutions, which must often prioritize technological advancements around agriculture, engage in addressing systemic gender discrimination that goes beyond agriculture?

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the ILRI Institutional Research Ethics Committee (Ref. IREC2017-20) and IFPRI Institutional Review Board (#00007490).

Consent to participate

Written consent to conduct the interview and record it was obtained from all participants in either English or Kiswahili. As compensation, FGD participants were offered 1000 KSH (approximately US$10) – to cover transport and compensate for the income lost by closing their business during the discussion – and refreshments. SSII and KII participants were offered 300 KSH (approximately US$3)Footnote7. Such sums were considered not to bias responses given the exploratory nature of our study (vis-à-vis, for example, an evaluation of project effectiveness).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Alessandra Galiè, Silvia Alonso, Nelly Njiru, Jessica Heckert, Emily Myers; Methodology: Alessandra Galiè, Nelly Njiru, Jessica Heckert, Emily Myers; Formal analysis and investigation: Alessandra Galiè, Nelly Njiru; Writing – original draft preparation: Alessandra Galiè, Nelly Njiru; Writing – review and editing: Alessandra Galiè, Nelly Njiru, Jessica Heckert, Emily Myers, Sylvia Alonso; Funding acquisition: Silvia Alonso; Resources: Silvia Alonso; Supervision: Alessandra Galiè.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. Authors are responsible for the correctness of the statements provided in the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alessandra Galiè

Alessandra Galiè works as Team Leader: Gender at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) based in Kenya. Her research integrates gender analysis in livestock value chains with a particular focus on women’s empowerment, animal genetics, human nutrition, and seed governance. Before joining ILRI she worked at the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) undertaking gender research in empowerment, seed governance, and participatory plant breeding. Alessandra holds a Ph.D. from Wageningen University, Netherlands, and an MA in Social Anthropology of Development from the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Nelly Njiru

Nelly Njiru currently works at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) as a Research Officer 1. She holds a Master of Science degree in Agricultural and Applied Economics. She is involved in both quantitative and qualitative research integrating a gender lens in livestock and feed value chains. Her work has a keen focus on institutional structures that limits efforts towards realization of gender equality and women’s empowerment. Further she has experience in facilitating multi-stakeholder platforms geared towards enhancing market access for value chain actors, capacity building and design of learning materials.

Jessica Heckert

Jessica Heckert is a Research Fellow in the Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division at the International Food Policy Research Institute. Using both quantitative and qualitative methods, her research addresses questions related to the intersection of gender dynamics and health outcomes, the factors that lead to productive and healthy outcomes for young women and men during the transition to adulthood, and the development of metrics for measuring women’s empowerment. She is a social demographer and earned a Ph.D. in Demography and Human Development & Family Studies from the Pennsylvania State University in 2013.

Emily Myers

Emily Myers is a research analyst in the Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division at the International Food Policy Research Institute. At IFPRI, she is involved with qualitative research about gender and development. She also works on the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI). In addition to her research activities, she facilitates IFPRI’s Gender Task Force, a cross-institutional group that supports researchers incorporating gender into their work, identifies knowledge gaps pertaining to gender, disseminates IFPRI’s gender research, and links relevant gender policy research within the CGIAR. She has a Master’s degree in public health from Emory University.

Silvia Alonso

Silvia Alonso is a Senior Scientist at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. She has more than 10 years of experience in public health research, both in Europe and internationally, focusing on the impacts of livestock production on human health. Her current research explores how to leverage livestock value chains to improve health and nutrition. She is leading the first large-scale field trial of an intervention in informal markets to improve food safety and child nutrition in peri-urban Nairobi. She is a Diplomate of the European College of Veterinary Public Health and the Chair of the ethics IRB at ILRI.

Notes

1 “Sensitizing concepts are constructs that are derived from the research participants’ perspective, using their language or expressions, and that sensitize the researcher to possible lines of inquiry” (Given, Citation2008).

2 Interviews were paused if a prospective client stopped at the premises to maintain privacy.

3 While all participants generally identified themselves in one of these roles, the “name” they attached to the role varied. Some may have called themselves a “middleman” while others described their role as a “broker.” To streamline the name assigned to each role, we analyzed the description participants gave of their activities and assigned a name to each role as reported in .

4 Pasteurized milk sold in plastic sachets or ultra-heat treated (UHT) milk in cartons processed industrially (formal milk sector).

5 Raw milk is milk that has not undergone a pasteurization process.

6 A “hotel” is local word for a very small restaurant on the street side selling basic meals.

7 SSII participants were offered less than FGD participants, because the SSIIs were conducted at their premises, which allowed them to continue selling the milk and meant that they did not incur transportation costs.

References

- Alonso, S., Muunda, E., Ahlberg, S., Blackmore, E., & Grace, D. (2018). Beyond food safety: Socio-economic effects of training informal dairy vendors in Kenya. Global Food Security, 18, 86–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2018.08.006

- Arora, D. (2015). Gender differences in time-poverty in rural Mozambique. Review of Social Economy, 73(2), 196–221. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2015.1035909

- Bowen, G. A. (2006). Grounded theory and sensitizing concepts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(3), 12–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500304

- Campos, F., Frese, M., Goldstein, M., Iacovone, L., Johnson, H., McKenzie, D., & Mensmann, M. (2017). Teaching personal initiative beats traditional business training in boosting small business growth: Supplementary materials. Science, 357(6357), 1287–1290. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan5329

- Campos, F., & Gassier, M. (2017). Gender and enterprise development in Sub-Saharan Africa: A review of constraints and effective interventions. World Bank Group.

- Coles, C., & Mitchell, J. (2010). Gender and agricultural value chains and practice and their policy implications. A review of current knowledge and practice and their policy implications. Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Collins, C. S., & Stockton, C. M. (2018). The central role of theory in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918797475

- Donmoyer, R. (2012). Can qualitative researchers answer policymakers’ what-works question? Qualitative Inquiry, 18(8), 662–673. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800412454531

- Elson, D. (1999). Labor markets as gendered institutions: Equality, efficiency and empowerment issues. World Development, 27(3), 611–627. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00147-8

- Farnworth, C. R., Kantor, P., Kruijssen, F., Longley, C., & Colverson, K. E. (2015). Gender integration in livestock and fisheries value chains: Emerging good practices from analysis to action. International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology, 11(3–4), 262–279. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/IJARGE.2015.074093

- Galiè, A. (2013). The empowerment of women farmers in the context of participatory plant breeding in Syria: Towards equitable development for food security. Wageningen University and Research Centre.

- Galiè, A., & Kantor, P. (2016). From gender analysis to transforming gender norms: using empowerment pathways to enhance gender equity and food security in Tanzania. In J. Njuki, J. R. Parkins, & A. Kaler (Eds.), Transforming gender and food security in the global south. International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and Routledge.

- Given, L. (2008). The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. SAGE.

- Given, L. M. (2016). 100 questions (and answers) about qualitative research. SAGE.

- Heckert, J., Myers, E., & Malapit, H. J. (2020). Developing survey-based measures of gendered freedom of movement for use in studies of agricultural value chains. Discussion paper #1966. Intl Food Policy Res Inst.

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, ICF International. 2014. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Nairobi, Kenya.

- Mahoney, J., & Goertz, G. (2006). A tale of two cultures: Contrasting quantitative and qualitative research. Political Analysis, 14(3), 227–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpj017

- McDermott, J., Johnson, N., Kadiyala, S., Kennedy, G., & Wyatt, A. J. (2015). Agricultural research for nutrition outcomes – Rethinking the agenda. Food Security, 7(3), 593–607. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-015-0462-9

- MoLD. (2010). Kenya national dairy master plan 2010. Volume I: A situational analysis of the dairy sub-sector. Ministry of Livestock Development (MoLD).

- Mtimet, N., Walke, M., Baker, D., Lindahl, J., Hartmann, M., & Grace, D. (2015). Kenyan awareness of aflatoxin: An analysis of processed milk consumers. IAAR.

- Mutavi, S. K., Kanui, T. I., Njarui, D. M., Musimba, N. R., & Amwata, D. A. (2016). Innovativeness and adaptations: The way forward for small scale peri-urban dairy farmers in semi-arid regions of South Eastern Kenya. International Journal of Scientific Research and Innovative Technology, 3(5), 1–14.

- Nelson, J. (2017). Using conceptual depth criteria: Addressing the challenge of reaching saturatio. Qualitative Research, 17(5), 554–570. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794116679873

- Njuki, M. J., Wyatt, A., Baltenweck, I., Yount, K., Null, C., Ramakrishnan, U., Webb Girard, A., & Sreenath, S. (2016). An exploratory study of dairying intensification, women’s decision making, and time use and implications for child nutrition in Kenya. The European Journal of Development Research, 28(4), 722–740. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2015.22

- Quisumbing, A. R., Rubin, D., Manfre, C., Waithanji, E., van den Bold, M., Olney, D., Johnson, N., & Meinzen-Dick, R. (2015). Gender, assets, and market-oriented agriculture: Learning from high-value crop and livestock projects in Africa and Asia. Agriculture and Human Values, 32(4), 705–725. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9587-x

- Rademaker, I. F., Koech, R. K., Jansen, A., & Van der Lee, J. (2015). Smallholder dairy value chain interventions: The Kenya Market-Led Dairy Programme (KMDP) – Status Report. Wageningen UR Centre for Development Innovation. kmdp_smallholder_dairy_value_chain_interventions.pdf(snv.org)

- Roesel, K., & Grace, D. (Eds.). (2014). Food safety and informal markets: Animal products in sub-Saharan Africa. Routledge.

- Rubin, D., & Manfre, C. (2014). Promoting gender-equitable agricultural value chains: issues, opportunities, and next steps. In A. R. Quisumbing, R. Meinzen-Dick, T. L. Raney, A. Croppenstedt, J. A. Behrman, & A. Peterman (Eds.), Gender in agriculture: Closing the knowledge gap (pp. 287–313). Springer.

- Stoian, D., Donovan, J., Elias, M., & Blare, T. (2018). Fit for purpose? A review of guides for gender-equitable value chain development. Development in Practice, 28(4), 494–509. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2018.1447550

- Tavenner, K., Fraval, S., Omondi, I., & Crane, T. A. (2018). Gendered reporting of household dynamics in the Kenyan dairy sector: Trends and implications for low emissions dairy development. Gender, Technology and Development, 22(1), 1–19.

- van Veenhuizen, R. (2006). Cities farming for the future. Urban agriculture for sustainable cities. IIRR, RUAF, IDRC. https://www.idrc.ca/en/book/cities-farming-future-urban-agriculture-green-and-productive-cities

- Wekwete, N. N. (2014). Gender and economic empowerment in Africa: Evidence and policy. Journal of African Economies, 23(suppl 1), i87–i127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejt022

- Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., Garnett, T., Tilman, D., DeClerck, F., Wood, A., Jonell, M., Clark, M., Gordon, L. J., Fanzo, J., Hawkes, C., Zurayk, R., Rivera, J. A., De Vries, W., Majele Sibanda, L., … Murray, C. J. L. (2019). Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet, 393(10170), 447–492. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4