abstract

In a postcolonial, deeply patriarchal culture, decisions are often made for Indian women about every aspect of their life – beginning with whether they will be allowed to be born. This is followed by every life decision, including education and marriage. A ‘surrogate decision-maker’ is a guardian who decides for an adult incapable of making their own decisions due to a mental health condition, or as a substitute based on a patient’s stated or predicted wishes. However, the majority of Indian women are ‘controlled’ and ‘allowed’ or otherwise regarding everything. No choice in women’s life is women’s own, including decisions about deeply personal experiences such as giving birth.

Our article is embedded in feminist epistemology and uses voice-centred relational analysis of interviews with four women from impoverished backgrounds in Bihar, India, to explore decision making around childbirth and throughout their lives. The surrogate decision-makers in the birth environment are: 1) healthcare and non-healthcare providers, and/or 2) family members (who play the dominant role in every other decision about women’s lives). They communicate amongst themselves about a woman’s active bodily experience. Through I-poems we present women’s varied levels of resistance and non-resistance to obstetric violence, which can be looked at as an extension of their response to violence in their routine lives. We find similarities in women’s conditioning to endure, and argue that women should be the key stakeholders of their decisions about themselves and their bodies, which includes decisions about birth.

Introduction

A ‘surrogate decision-maker’ is a guardian who decides for an adult incapable of making their own decisions due to a mental health condition. This could also be a substitute who decides based on the stated wishes of a patient or based on predictions (Hammami et al. Citation2020). In this article we use the term ‘surrogate decision-maker’ in relation to people who engage in informal decision-making for women during childbirth, which is an extension of how decisions are made for girls and women throughout their lives. In deeply patriarchal cultures women have a limited decision-making role, especially about their sexual, reproductive and maternal health and needs (Jeejebhoy & Santhya Citation2018; Koski, Stephenson & Koenig Citation2011). While the culture of violence presents one end of patriarchy, the denial of pleasure to women presents the other (hooks Citation2000).

Our study is based in Bihar, a state in the postcolonial country of India, which reports a total fertility rate of 3 children per woman – the highest among all Indian states (Government of India (GOI) Citation2020). Around 48% of the 107 million population of Bihar is women (GOI Citation2011) and 76.2% of the childbirths take place in healthcare institutions (GOI Citation2020). There are several indicators that reveal a lack of women’s agency in Bihar. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) reports that only 12.6% of women were paid in cash for their work, only 28.8% had completed 10 years of education, and 40.8% (now aged 20–24 years) were married before they turned 18 (GOI Citation2020). This highlights that child marriage is a persistent issue in the state.

The high rates of gender-based violence and crimes against women show further disempowerment and oppression of women (Dhar et al. Citation2018; Jejeebhoy & Santhya Citation2018). Intimate partner violence is another key issue in the state (Dhar et al. Citation2018). The NFHS-5 reports that 40% of women have experienced spousal violence and 2.8% experienced it during pregnancy. Among the women surveyed who were aged 18–29 years, 8.3% reported experiencing sexual violence before they turned 18. Gender-based discrimination is also evident in other indicators, such as female sterilisation (34.8%), which is much higher than male sterilisation (0.1%), and the decreasing sex ratio (908) at birth (GOI Citation2020). (Sex ratio is the ratio of the number of females born per 1000 males in a population. It is usually presented with just the number of females as the number of males (1000) is standard.)

A culture of violence and subjugation is a part of a patriarchal structure, where women and girls have limited agency over their bodies and lives. This seems to extend to the obstetric setting as well. Lack of consent and explanation of obstetric interventions are key indicators in this context, the incidence of which is often very high (Bhattacharya et al. Citation2013; Patel, Das & Das Citation2018), further indicating a lack of women’s consent and choice in obstetric birth environments. This is normalised, as is being ‘allowed’ to do anything in women’s routine lives. This is a result of girl’s and women’s positioning at the intersections of several ‘female’ disadvantages, which increase their vulnerability (Sen & Iyer Citation2012; Chattopadhyay Citation2018; Chadwick Citation2018). While this is common in patriarchal and postcolonial settings, the extent may vary between different contexts, states and countries, reflecting in women’s low expectations even when desiring respectful care (Espinoza-Reyes & Solis Citation2020; Bhattacharya et al. Citation2013; Afulani et al. Citation2019; United Nations Citation2019; Lambert et al. Citation2018). This is a characteristic of the medical model of care around childbirth, a result of the gradual transition from home as the more common and accepted birth setting, to domination by the obstetric birth setting over the last decades, which continued the alienation of women’s reproductive rights (Oakley Citation1984; Hill Citation2019).

Factors driving obstetric violence are best understood through intersectionality (Sen, Reddy & Iyer Citation2018). In Bihar, women face discrimination based on socio-demographic factors including, but not limited to, gender, marital status, religion, caste, occupation, skin colour, age, number of children, economic status, disability and personal hygiene (Patel, Das & Das Citation2018; Dhar et al. Citation2018; Mayra, Matthews & Padmadas Citation2021). The resulting imbalance in power between the woman and care providers leads to women experiencing obstetric violence (Sen et al. Citation2018; Mayra, Matthews & Padmadas Citation2021). This may result in women’s voices and choices being disregarded, and in the act of not seeking consent and deciding for women as surrogate decision-makers in an obstetric setting (Madhiwala et al. Citation2018).

Objectives

The objectives of this study were to:

explore the extent of informal surrogate decision-makers’ role in deciding for women about and during childbirth; and

understand women’s experience and role in decision making about their lives and during childbirth.

Methods

This study is embedded in feminist epistemology and guided by critical feminist theory. We analysed case studies of four women who were interviewed in urban slums and rural villages in Bihar, India. In-depth interviews were conducted in November and December 2019 by adapting a visual arts-based research method called body mapping. The process of data collection was completed through multiple interactions with each participant over a week to generate rich accounts of their experiences and perceptions.

Ethical consent was received from the Research Ethics Review Board at the University of Southampton, UK (reference number 49730). Participants provided formal consent for interviews and audio recording. The female first author facilitated all the interactions with help from a research assistant from Bihar. While we had formal consent from women for this study, we faced many problems in getting access to these women through gatekeepers. This has been seen in other countries with strong patriarchal cultures (Alzyoud et al. Citation2018).

We applied voice-centred relational analysis to analyse the data with the aim to understand decision-making about and during childbirth and its connection with decision-making about women’s lives in general. We shifted our attention from conventional coding methods into pre-existing categories, to emerging voices (Hutton & Lystor 2019). We engaged with the listening guide, which provides an interpretive approach to enable analysis of family life, which involved listening to women’s narratives on their agency about childbirth. It is a creative and non-linear method (Frost Citation2008) that helped to understand the context that shapes and generates narratives of what decision-making means for women in general. The process of analysis through this polyphonic method involved multiple listening to the interview audio recordings. This helped to understand, compare and articulate women’s agency about childbirth, relational to the dynamics of their regular lives, by revisiting the narrative from different analytic angles. Poetic enquiry allows the reader to deeply immerse themselves into the participant’s journey and experiences through the I-poems, which are very emotive and telling (McKenzie Citation2021). This could mean looking into their private and public experiences, where childbirth is a private experience made public.

Voice-centred relational analysis amplifies ‘voices of the silenced by dominant cultural frameworks’, especially in contexts that involve experiencing stigma and shame (Sorsoli & Tolman Citation2008), including childbirth. Previous studies have used it to understand women’s experience with maternal health care, to explore maternal depression and women’s decision to freebirth, which makes it an appropriate analytic choice for this study (Montgomery Citation2012; Edwards & Weller Citation2012; Fontein-Kuipers 2018; McKenzie Citation2021). The listening guide is structured to enable: 1) listening for the plot; 2) listening for the voice of ‘I’, which involves tracing out and arranging a participant’s reference to self in the first person starting with ‘I’, scattered throughout the transcript; 3) listening for contrapuntal voices and relationships which enable the researcher to understand the complex multiple, and often overlapping voices that exist within the same sentence or section of the narrative; and 4) listening for broader social, political and cultural structures that help to thaw out the larger discourses influencing the women’s conceptions of their positionality, linking their narratives to sociocultural factors.

The process includes the generation of ‘I-poems’ which capture their actual voices. In our study the participants’ reference to ‘I’ was supplemented by references to ‘my’ and ‘me’ on a few occasions, to ensure more detail and depth in the narrative and for a richer understanding of the context. There are other pronoun poems that researchers have used to present a different perspective and angle (Chadwick Citation2017). There are different ways of creating and constructing the I-poems; we focus on creating the ‘full’ poems to allow some context into the poems and add more depth to the narrative. Parts of the texts are bold, based on the first author’s subjectivity, to emphasise certain aspects of the poem.

The choice of methods for data collection, analysis and presentation is made mindfully to engage with the audience through their ears, eyes and mind. The aim is to move them to make an impact by stirring their emotions (McKenzie Citation2021).

Findings

We present case studies of four women who shared their experiences. Their names are pseudonyms which they selected. Ria is a 32-year-old mother of a four-year-old girl. Ria has completed 12 years of school education and works as a cleaner in an office and sells cow’s milk. Urmila is a 25-year-old mother of two girls and one boy, who has completed 6 years of formal education. She is a homemaker and gave birth at ages 19, 21 and 23. Ria and Urmila were interviewed in the urban slums of Patna, Bihar. Amrita is a 22-year-old mother of a son and a daughter who gave birth at ages 18 and 20. She manages a small grocery shop and has received no formal education. Pairo is a 29-year-old mother of a son and a daughter. She is a government school teacher who was pursuing her postgraduate studies in arts at the time of data collection. She gave birth at ages 25 and 28. Amrita and Pairo were interviewed in rural villages in Muzaffarpur district, Bihar.

Surrogate decision-making for women’s births

There are three types of surrogate decision-makers during childbirth in the obstetric setting where participants in this study gave birth: 1) qualified healthcare providers in the hospital (nurse midwife, doctor); 2) unqualified care providers and mobilisers (cleaners, MAMTAs, dagarin/dai, ASHAsFootnote1); and 3) women’s birth companions from family/neighbourhood (husband, mother, mother-in-law, etc.). There is a clear distinction between home and hospital-based decision-makers, although category 2 of surrogate decision-makers overlaps to some degree between childbirth-related decision-making in the home and hospital settings.

Pairo, Amrita, Ria and Urmila received healthcare services from doctors and nurses at some point during their childbirth/s in the obstetric setting. They reported many small and large decisions made about them which were not communicated to them. They all shared the alienating experience of having these surrogate decision-makers around them, often talking above them, about them, but not to them. These decisions could be about various aspects of care, from augmentation, injection, fluids, and other forms of medication to non-consensual surgical interventions such as vaginal examination. Urmila’s I-poem ‘The lady doctor was really nice!’ has aspects of surrogate decision-making by the ‘lady doctor’. It also shows her resistance, through repeated denial of consent, to vaginal examination, but the doctor decided to carry on. The poem also shows her strong verbal objection to the episiotomy repair, which appears to have been performed without anaesthesia, but her denial of consent was disregarded (Poem 1). The titles of the poems are given in italics because they are selected from the participants’ transcripts.

Poem 1: The lady doctor was really nice!

It is important to note that even though Urmila had a traumatic experience, she still felt that the ‘lady doctor was nice’. This reflects the low expectations women had of care, and the contrast is reflected in the poem’s title. Similar experiences are noticed in Ria and Sita’s birth stories, where they resist but there is compliance as well.

In the next poem, while Sita was listened to when she denied vaginal examination, for which consent was not sought anyway, she experienced other interventions, such as vaginal examination while being physically restrained from all sides. That made her feel uncomfortable and ashamed. In this poem the bold text shows the enforced passivity in the participant’s own birthing experience, where the people are performing on her, an aspect which is felt and narrated by all the participants in some way. The bold text presents the theme of surrogate decision-making and highlights aspects where women narrate about not being able to decide.

Poem 2: I Felt Bad!

Amrita is seen to be undergoing a traumatic experience, and the second half of her poem also shows that she coped with this by trying to ‘remove it from my mind’. This way of coping, by detaching self from the body or denying the experience, can also be seen in Pairo’s poem, ‘Doll’. In contrast to Urmila and Sita’s experience, Pairo’s poem captures compliance with surrogate decision-making about a major surgical intervention, i.e. cesarean section, that she did not consent to and was not informed about. She was ‘man-handled’ by many healthcare providers whom she had not met before. During her surgery, her clothes were moved up, she was exposed, her body was moved, she was given spinal anaesthesia, was blindfolded and operated on, all without consent and information. She was aware of the surroundings the entire time but could not physically take any action from being anaesthetised. Her poem shows instances where approximately ten people, mostly men, were in the operation theatre, who performed procedures on her in invasive ways without consent, quite literally and figuratively, while she was conscious and not in pain, which made her feel helpless like an inhuman object, a doll (Poem 3).

Poem 3: Doll

Pairo, Amrita and Urmila share their experience of being treated like an object. Their poems have been highlighted in some parts to show this enforced passivity in what is solely their experience. The extensive use of phrases such as ‘made me’, ‘allowed me’, ‘checked me’ and also ones where they are uninformed and trying to ‘imagine’, ‘hearing’ to figure out what was being done to them, shows this subjected alienation of women. Even in Urmila’s poem, her active and strong resistance to the traumatic experience can be noticed in the highlighted portions where she mentions about ‘screaming and crying’ and explicitly and repeatedly pleading ‘don’t do it’ but her requests are seen to be ignored when she says ‘kept suturing me’, ‘didn’t listen to me’, ‘forced hand inside me’ and ‘held me down’.

A surrogate decision-maker from the woman’s family, referred to as ‘guardian’, but often not chosen by the woman as a birth companion, takes on the authoritative role of communicating on her behalf. All the participants were above the age of 18 at the time of giving birth. The role of surrogate decision- makers from home can be seen in Poem 2, where Amrita retained agency when she refused to have a home birth assisted by her mother-in-law, a dagarin and stated her choice to give birth in a hospital. Her mother-in-law still played the role of a surrogate decision-maker in many other instances in the obstetric environment, which included insisting Amrita get vaginal examinations. This is a common observation where the birth companion sides with the hospital-based surrogate decision-makers instead of advocating for the woman giving birth and her choice.

Surrogate decision-making for women’s lives

The conversations with women indicated that major decisions about their lives were made by surrogate decision-makers at home, by their family. This was obvious in the narratives of all participants, who had a limited decision-making role regarding decisions about their lives and their bodies. This powerlessness in the obstetric environment was also learned from women’s narratives about their lives, where connections to the impact of a patriarchal culture, where women exceedingly lack a voice, could be noticed in the obstetric birth environment, which is a part of the social environment. This can be seen in the next two poems by Ria and Urmila. In poem 4, Ria describes her resentment at having birthed a girl - she wished to have had a son—which would be better in a patriarchal culture for the privileges of the ‘male advantage’.

Poem 4: Had I been fairer and had birthed a boy …

Ria describes the female disadvantage well, in a world where decisions are made by men and even relatives in an extended family can cause major disruptions in women’s lives just by spreading rumours. It is due to this experience of gender-based discrimination that she justifies that her family would have been better looked after if there were men in the family. The absence of men across three generations is the biggest challenge her family faces, in her opinion, as it exposes them to criticism and societal ridicule. This is noticed in all the participants’ stories, as presented in poem 5. Urmila describes this normalised lack of agency that she has experienced all her life.

Poem 5: I never made a decision for myself

In both Ria and Urmila’s poems they narrate surrogate decision-making as the usual way of life, which can also be observed in their expectations, where they hold the surrogate decision-maker accountable for not deciding well for them. They display resentment, though not explicitly towards the people ‘responsible’, for the troubles in their life that their decisions led to.

Surrogate decision-making suffuses every aspect of women’s lives, as seen in poem 1 and poem 5 about Urmila. There is compliance with patriarchal societal norms and rules in the obstetric birth environment and the social environment. Being born and conditioned into patriarchy often leaves little to no scope for women to make any decisions about themselves, although there is a narrative of resistance embedded in both of Urmila’s poems. This resistance in the obstetric birth environment is seen in her repeated attempts to stop the doctor and nurses from performing the unanaesthetised episiotomy repair (poem 1). Her success in putting her husband in jail for abuse of alcohol, followed by intimate partner violence and also financial neglect, shows her resistance in the social environment. However, this narrative of such strong resistance is rare in other participants’ stories.

Discussion

Women were uninformed and left to guess what is being done to them in obstetric settings during invasive interventions such as vaginal examination, uterine exploration and caesarean birth. Women were not considered a stakeholder in their own birth experience, let alone as decision-makers. Pairo’s parents were informed by her doctor that she is going to be operated on, but they did not share that information with Pairo, who only realised it after being dragged to the operation theatre, blindfolded and given spinal anaesthesia. Pairo’s passive voice of interventions being done to her are highlighted in her poem ‘Doll’. This is another example of home- and hospital-based surrogate decision-makers joining forces in decision-making, while the birther remains unconsented and uninformed. Pairo was not communicated with at all in the operation theatre, not even to tell her that she gave birth to a girl. There is a sense of detachment which can be noticed when she describes herself as being treated as a doll and an animal, clearly stating that she had no choice in the experience. The care provider’s role in making her feel invisible in her own birthing experience can also be seen in her narrative. This is in line with the women’s role in their routine lives, where a male member of the family (such as father, brother, husband and son) takes over the decision-making for women’s lives, making them feel invisible throughout their lives in the context in which this study is conducted. This is the dominant discourse in many contexts and cultures in different states in India, including Bihar (Dhar et al. Citation2018; Sen, Reddy & Iyer Citation2018; Menon Citation2012).

Villarmea (Citation2020) explains that the reason behind disrespecting women’s autonomy and the frequent disregard of their refusal of interventions is because of the ‘uterine influence’. Women are considered incapable of making rational decisions due to pain, and women’s choice and consent is often superseded because they are merely the ‘container’ for the ‘foetus’, who is considered the key stakeholder in childbirth. This is a clear characteristic of a patriarchal medical model of care (Oakley Citation1984; Hill Citation2019) – evident also in the failure of the doctor to stop upon Urmila’s strong resistance (poem 1). Urmila’s anxiety at her decision to put her husband in prison (poem 5) is a sign of deep-rooted patriarchal conditioning. Her anxiety is about breaking the norms and the realisation of the repercussions of this act of resistance upon her and her children, from her husband’s family and society, and from her husband when he is released from prison.

The women’s narratives display a patriarchal culture where their voices and choices have limited scope. When patriarchy permeates the birthing environment, medical interventions are prioritised over women’s comfort, dignity and choice (Villarmea Citation2020; Mayra, Matthews & Padmadas Citation2021). Urmila shared praise about her doctor during the interview, regardless of the traumatic experience she narrated (poem 1). This is indicative of a structural issue and part of the cultural conditioning of women. We notice this in women’s expectations, acceptance, and endurance and their reaction to the violence and lack of a decision-making role during childbirth in an obstetric environment, and in their routine life in their social environment.

Several studies report various aspects of women’s lives, mostly violent; however, the description of this as obstetric violence or disrespect and abuse during childbirth is new and rising in Bihar, other parts of India and globally (Sen, Reddy & Iyer Citation2018; Mayra & Hazard Citation2020; Mayra, Matthews & Padmadas Citation2021; Chattopadhyay Citation2018, Dhar et al. Citation2018; Chadwick Citation2018). Women’s right to give consent and to choose is essential for a positive birthing experience, especially in an obstetric setting. Surrogate decision-making is a violation of women’s reproductive rights and a driver of obstetric violence. It is difficult to raise these issues in patriarchal contexts for women who experience different levels and layers of oppression.

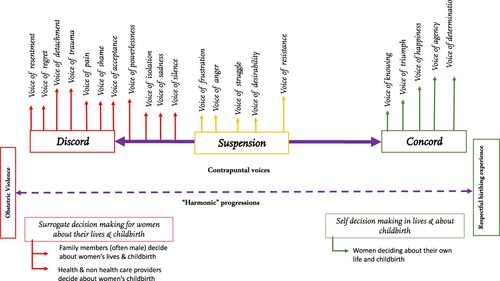

Feminist methods reduce the power-based imbalance between the researcher and participant and voice-centred relational analysis is a unique and novel method which ensures that women’s voices are prioritised and at the centre. This multilayered analysis is a key strength of this study, which guided listening to the contrapuntal voices in the poems. presents a range of contrapuntal voices heard in the women’s poems in this study, through the language of music.

Figure 1. Range of women’s contrapuntal voices about self decision-making and surrogate decision-making during childbirth and in life.

The range shows ‘discord’ at its negative end, where women experience extreme forms of obstetric violence and its consequences. It transitions through the ‘harmonic progressions’, which express women’s struggle and resistance, extending to the extreme positive end of ‘concord’ for a satisfying and positive birthing experience. Women’s experiences are not linear or one-directional.

In all the five poems, the dominant discourse is of the contrapuntal voices of discord and suspension, rather than of concord. Even within the poems, the voices depicting concord were limited, whereas the duration of the voices of discord was longer for all four women’s experiences. Pairo’s poem ‘Doll’ had the voice of determination and happiness only at one instance each, when she is happy that she has given birth to a girl and is determined to take her to school with her. The other voices were those of shame, powerlessness, trauma, fear, silence, isolation, sadness, detachment and struggle. The two poems from Urmila’s experience have an aligned narrative about decision-making in the birthing environment (poem 1) and in her life (poem 5). These voices can be noticed not just in the birth-related poems but in their routine life-related poems as well, and it helps to draw the connections between the two for each participant. The voices of silence, powerlessness, isolation, pain, fear, anger, resistance and struggle can be noticed in both domains; similarly, on the positive side, the less frequent voice of triumph can be heard, with Urmila sending her husband to jail.

Some of the voices prevail more than others, and one of these figures can be created for each participant, focusing on just her contrapuntal voices. This study makes the important contribution of creating new methods of listening to and learning from women’s voices about their experiences of violence in their routine lives and during childbirth. This approach can help care providers to understand what women want and to tailor-make care for women that is informed by their choices and is context and culture appropriate and compassionate.

Conclusion

As women’s agency in decision-making increases, the territory of surrogate decision-making will decrease. Surrogate decision-making is the dominant discourse in the obstetric birth setting in India, as can be seen in this study, where women were not consulted with, their choices were not considered and their consent was not sought. That needs to change, to ensure that women are the key stakeholder, making decisions about their own birth experience for respectful maternity care in every aspect of childbirth and a positive birthing experience.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kaveri Mayra

KAVERI MAYRA is a midwifery, nursing and public health researcher with experience in nursing and midwifery workforce policies and care provision, mainly in India and internationally. Having seen mistreatment during childbirth early on as a student midwife and having experienced the lack of leadership and the decision-making power of midwives and nurses, she started researching and advocating globally on these life experiences and issues. She is currently pursuing her PhD in Global Health at the University of Southampton, UK, exploring the determinants of obstetric violence in India and working as a Subject Matter Expert at the WHO HQ in Geneva. Email: [email protected] Twitter @Mayra_K11

Zoë Matthews

ZOE MATTHEWS is Professor of Global Health and Social Statistics at the University of Southampton, UK. Her research covers women’s health, midwifery, maternal and reproductive health, and also the health of adolescents. Her core interests centre around health systems, the health workforce, and quality of care for women and girls. She is a core member of the analysis and writing team for successive State of the World’s Midwifery reports in collaboration with UNFPA and the WHO. Email: [email protected] Twitter @TheZedster

Jane Sandall

JANE SANDALL is a Professor of Social Science and Women’s Health in the Department of Women and Children’s Health, School of Life Course Sciences, King’s College London, and an adjunct professor at University of Technology Sydney. She is an NIHR Senior Investigator and has a clinical background in nursing, health visiting and midwifery and an academic background in social science. She is leading research looking at mechanisms and impact of models of midwife continuity of care for women at higher risk of pre-term birth and to reduce inequalities in care and outcomes for women and babies. Her research findings have informed the UK government, English, Scottish, US, Brazilian, Irish and Australian reviews of maternity services and the WHO. Email: [email protected] Twitter @SandallJane

Notes

1 MAMTAs are a cadre of unqualified care providers in Bihar who are trained to provide some counseling on breastfeeding and maintaining personal hygiene. ASHAs are Accredited Social Health Activists who mobilise women for institutional birth. Dai and Dagarin are traditional midwives who have been assisting at births in the communities through generations.

References

- Afulani, PA, Phillips, B, Aborigo, RA & Moyer, CA 2019, ‘Person-centered maternity care in low-income and middle-income countries: Analysis of data from Kenya, Ghana and India’, Lancet Global Health, no. 7, pp. 96–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30403-0

- Alzyoud, F, Khoshnood, K, Alnatour, A & Oweis A 2018, ‘Exposure to verbal abuse and neglect during childbirth among Jordanian women’, Midwifery, vol. 58, pp. 71–76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2017.12.008

- Bhattacharya, S, Srivastava, A & Avan, BI 2013 ‘Delivery should happen soon and my pain will be reduced: understanding women’s perception of good delivery care in India’, Global Health Action, vol. 6, no. 22365. doi: https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v6i0.22635

- Chadwick, R 2018, Bodies that birth: vitalizing birth politics, Routledge Publishers, London.

- Chadwick, R 2017, ‘Embodied methodologies: challenges, reflections and strategies’, Qualitative Research, vol. 17, no. 1. pp. 54–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794116656035.

- Chattopadhyay, S 2018, ‘The shifting axes of marginalities: the politics of identities shaping women’s experiences during childbirth in Northeast India’, Reproductive Health Matters, vol. 26, no. 53, pp. 62–69. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2018.1502022

- Dhar, D, McDougal, L, Hay, K et al. 2018, ‘Associations between intimate partner violence and reproductive and maternal health outcomes in Bihar, India: a cross sectional study’, Reproductive Health, vol. 15, no. 109. doi. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0551-2

- Edwards, R & Weller, S 2012, ‘Shifting analytic ontology: using I-poems in qualitative longitudinal research’, Qualitative Research, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 202–217. doi. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111422040

- Espinoza-Reyes, E & Solis, M 2020, ‘Decolonizing the women: agency against obstetric violence in Tinuana, Mexico’, Journal of International Women’s Studies, vol. 21, no. 7, pp. 189–206.

- Fontein-Kuipers, Y, Koster, D, Romjin, C et al. 2018, ‘I Poems - Listening to the voices of women with a traumatic birth experience’, Journal of Psychology and Cognition, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 29–39.

- Frost, J 2008, ‘Combining approaches to qualitative data analysis: synthesising the mechanical (CAQDAS) with the thematic (a voice-centred relational approach)’, Methodological Innovations Online, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 25–37.

- Government of India 2011, Census of India, accessed 20 February 2021. https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-common/censusdata2011.html

- Government of India 2020, National Family Health Survey-5 (2019-20), accessed 20 February 2021. http://rchiips.org/nfhs/factsheet_NFHS-5.shtml

- Hammani, MM, Balkhi, AA, Padua, SSD & Abuhdeeb K 2020, ‘Factors underlying surrogate medical decision-making in middle eastern and east Asian women: a Q-methodology study’, BMC Palliative care, vol. 19, no. 137. doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00643-9

- Hill, M 2019, Give birth like a feminist, HarperCollins, London.

- hooks, b 2000, Feminism is for everybody, South End Press, Boston.

- Hutton, M & Lystor C 2021, ‘The listening guide: voice-centered-relational analysis to private subjectivities’, Qualitative Market Research, vol. 24, no. 1. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-04-2019-0052

- Jejeebhoy, SJ & Santhya, KG 2018, ‘Preventing violence against women and girls in Bihar: challenges for implementation and evaluation’, Reproductive Health Matters, vol. 26, no. 52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2018.1470430

- Lambert, J, Etsane, E, Bergh, AM, Pattison, R & Broek, N 2018, ‘“I thought they were going to handle me like a queen but they didn’t”: A qualitative study exploring the quality of care provided to women at the time of birth’, Midwifery, no. 62. pp. 256–263. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2018.04.007

- Koski, AD, Stephenson, R & Koenig, MR 2011, ‘Physical violence by partner during pregnancy and use of perinatal care in Rural India’, Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 245–254.

- Mayra, K & Hazard, B 2020, ‘Why South Asian women make extreme choices during childbirth’, in H Dahlen, B Hazard & V Schmied (eds), Birthing outside the system: The canary in the coalmine, Routledge, London, pp. 189–210.

- Mayra, K, Matthews, Z & Padmadas, S 2021, ‘Why do some health care providers disrespect and abuse women during childbirth in India?’, Women and Birth. In press.

- Madhiwala, N, Ghoshal, R, Mavani, P & Roy, N 2018, ‘Identifying disrespect and abuse in organizational culture: A study of two hospitals in Mumbai, India’, Reproductive Health Matters, vol. 26, no. 53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2018.1502021

- McKenzie, G 2021, ‘Freebirthing in the United Kingdom: The Voice Centered Relational Method and the (de)construction of the I-Poem’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 20, pp. 1–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406921993285

- Menon, N 2012, Seeing like a feminist, Zubaan, New Delhi.

- Montgomery, E 2012, Voicing the silence: the maternity care experiences of women who were sexually abused in childhood, Doctoral thesis, University of Southampton, Southampton, accessed 20 February 2021. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/349089/

- Oakley, A 1984, The captured womb: A history of the medical care of pregnant women, Oxford Publishing Services, Oxford.

- Patel, P, Das, M & Das, U 2018, ‘The perceptions, health seeking behaviours and access of Scheduled Caste women to maternal health services in Bihar, India’, Reproductive Health Matters, vol. 26, no. 54, pp. 114–125. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2018.1533361

- Sen, G, Reddy, B & Iyer, A 2018, ‘Beyond measurement: the drivers of disrespect and abuse in obstetric care’, Reproductive Health Matters, vol. 26, no. 53, pp. 6–18.

- Sen, G & Iyer, A, 2012, ‘Who gains, who loses and how: Leveraging gender and class intersections to secure health entitlements’, Social Science and Medicine, no. 74, pp. 1802–1811.

- Sorsoli, L & Tolman, DL 2008, ‘Hearing voices: listening for multiplicity and movement in interview data’, in SN Hesse-Biber & P Leavy P (eds), Handbook of Emergent Methods, The Guildford Press, New York, pp. 439–515.

- United Nations 2019, Report of the special rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences on a human rights based approach to mistreatment and violence against women in reproductive health services with a focus on childbirth and obstetric violence. 74th session on Advancement of women. A/74/137, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3823698

- Villarmea, S 2020, ‘When a uterus enters the room, reason goes out the window’, in C Pickles & J Herring (eds), Women’s birthing bodies and the Law, Hart Publishing, Oxford, pp. 63–78.