ABSTRACT

Objectives: Outpatient care is critical in the management of chronic diseases, including sickle cell disease (SCD). Risk factors for poor adherence with clinic appointments in SCD are poorly defined. This exploratory study evaluated associations between modifying variables from the Health Belief Model and missed appointments.

Methods: We surveyed adults with SCD (n = 211) and caregivers of children with SCD (n = 331) between October 2014 and March 2016 in six centres across the U.S. The survey tool utilized the framework of the Health Belief Model, and included: social determinants, psychosocial variables, social support, health literacy and spirituality.

Results: A majority of adults (87%) and caregivers of children (65%) reported they missed a clinic appointment. Children (as reported by caregivers) were less likely to miss appointments than adults (OR:0.22; 95% CI:(0.13,0.39)). In adults, financial insecurity (OR:4.49; 95% CI:(1.20, 20.7)), health literacy (OR:4.64; 95% CI:(1.33, 16.15)), and age (OR:0.95; 95% CI:(0.91,0.99)) were significantly associated with missed appointments. In all participants, lower spirituality was associated with missed appointments (OR:1.83; 95%CI:(1.13, 2.94)). The most common reason for missing an appointment was forgetfulness (adults: 31%, children: 26%). A majority thought reminders would help (adults: 83%, children: 71%) using phone calls (adults: 62%, children: 61%) or text messages (adults: 56%, children: 51%).

Conclusions: Our findings demonstrate that modifying components of the Health Belief Model, including age, financial security, health literacy, spirituality, and lacking cues to action like reminders, are important in missed appointments and addressing these factors could improve appointment-keeping for adults and children with SCD.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited disorder of hemoglobin that affects approximately 100,000 individuals in the U.S., many of whom are African American and many of whom also live in poverty [Citation1–4]. Preventive care is critical to reducing complications and maintaining health and quality of life for patients with SCD [Citation5]. National guidelines recommend routine follow-up appointments every 6 months, and more frequently for patients experiencing complications, or receiving disease modifying therapies (e.g. hydroxyurea or chronic blood transfusion therapy) [Citation6,Citation7].

Most of the literature about barriers to attending clinic appointments in SCD concerns the pediatric population, with very little focus on adults. Published adherence rates for routine clinic appointments in SCD range from 46 to 77% [Citation8,Citation9]. Adolescents with SCD and their caregivers have reported several barriers to clinic attendance, including competing activities, health status (both feeling well and not well enough to attend), poor patient-provider relationships, adverse prior clinical experiences, and forgetfulness [Citation10]. Caregivers have also reported existing barriers to Transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasonography screening that included limited finances, lack of transportation and inconvenient clinic hours [Citation11]. These barriers contrasted with the results from a retrospective medical record review that showed that privately insured patients were three times more likely to be adherent to TCD screenings [Citation12]. Health system barriers can also reduce attendance to health-maintenance visits among individuals with SCD, such as difficulties with contacting providers, extended wait times, and inconvenient clinic hours [Citation13]. Individuals with SCD residing in rural areas experience longer travel distances and limited access to primary and comprehensive outpatient services, resulting in higher rates of healthcare utilization [Citation14,Citation15]. Missed health-maintenance visits are costly to the healthcare system and contribute to increased acute care utilization [Citation16,Citation17]. Better understanding of local barriers to care in adults will help determine future interventions and funding allocations for services.

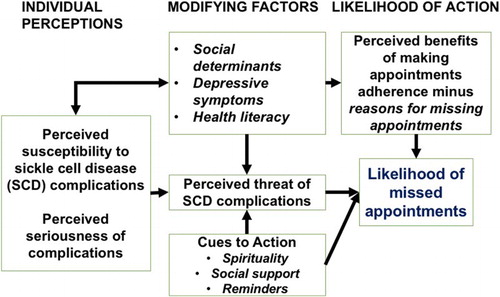

The present study surveys a geographically diverse population of individuals with SCD about factors that affect their utilization of ambulatory services. These surveys were based on the Health Belief Model (HBM –[Citation18]) to improve understanding of variables that influence behaviours that may lead to missed appointments. The HBM posits that taking a ‘health action’ such as keeping outpatient clinic appointments is a function of perceptions of the seriousness of the disease and that there are benefits, but limited barriers to the health action Citation19 . Modifying variables within the HBM may facilitate or hinder positive health actions (). Missing appointments has been associated with social determinants of health within the HBM including female gender, race, and lower socioeconomic status in primary care and other diseases [Citation20–23]. Missed appointments have also been associated with social support in SCD [Citation9,Citation10]. Spirituality and depressive symptoms have impacts in other self-care management like medication adherence in HIV, but have not been explored in relation to clinic attendance in SCD [Citation24]. We examined the association between modifying variables in the HBM model, including several self-report measures, and self-reported missed appointments for individuals with SCD. We explored associations between modifying components of the HBM and missed appointments among adults with SCD and caregivers of children. We also explored reasons for missed appointments and how to decrease them.

Methods

Setting

We surveyed a convenience sample of adults with SCD (age ≥18 years) and caregivers of children with SCD (patients age < 18 years) between October 2014 and March 2016. Surveys were completed at sites in three distinct geographical regions: the Midwest (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago), the Mid-South (University of Tennessee Health Science Center, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and, Vanderbilt University Medical Center), and the West (UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland). Only individuals who could speak and read English were included. Participants completed the survey only once.

The Mid-South Clinical Data Research Network (CDRN) [Citation25] was established in 2014 with funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). The 11 CDRN sites in the U.S. have the following collective goals: to engage at minimum 11 million patients across multiple healthcare systems, build infrastructure to share data and build novel informatics tools, and perform comparative effectiveness research and pragmatic clinical trials. The Mid-South CDRN survey tool was designed to obtain uniform information across obesity, coronary heart disease and SCD cohorts. The Institutional Review Boards of the participating sites approved all study procedures and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Procedure

Individuals with SCD and their caregivers were recruited using flyers placed in clinics, and were introduced to the study by their clinicians during regularly scheduled visit. Procedures were described in more detail by research staff during the informed consent session. The surveys were administered via computer tablet, but if a tablet was not available, by paper-and-pencil. Participants completed the surveys independently, with a member of the research team nearby to answer questions or provide assistance as needed. Participants received a gift card upon completion of the survey.

Survey tool

The Mid-South CDRN researchers and key stakeholders, including healthcare providers, psychologists, social workers, and individuals with SCD designed the survey tool based on selected components of the HBM framework including the following domains: social determinants of health, depressive symptoms, social support, health literacy and spirituality () as potentially influencing healthcare utilization and self-care in SCD [Citation26]. The complete survey consisted of 80 questions and took approximately 30 minutes to complete. The reading level of the questions and survey tools ranged from 5th to 7th grade. Outcome measures included self-reports of whether or not the individual with SCD missed any appointments within the past year.

Social determinants of health

The Mid-South CDRN survey tool gathered social determinants of health including age, sex, race, ethnicity, educational attainment, difficulty paying monthly bills, and marital status. Educational attainment, difficulty paying bills, and marital status were questions asked about caregivers of children, the remaining questions were asked about the child with SCD. We combined some categories of survey responses for ease of interpretation within the regression analyses. The five levels of education, ranging from some high school to post-graduate, were dichotomized into ‘High school graduate or less’ and ‘Some college or more.’ Participants who indicated that they were currently married or living with a stable partner were categorized as ‘Married or living together’ while those who were single, widowed, divorced or separated were categorized as ‘Unmarried.’ The items inquiring about financial status, ‘how difficult is it for you (your family) to pay your monthly bills’ were compressed into ‘Not very or Not at all difficult’ versus ‘Very or Somewhat difficult.’ These social determinants of health are modifying variables in the HBM.

Depressive symptoms

The survey tool provided for evaluation of depressive symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2 [Citation27]), a validated two-item screening for the frequency of depressed mood and anhedonia over the past two weeks. PHQ-2 scores range from 0 (not at all) to 6 (nearly every day), with a score of 3 suggesting the need for further evaluation of depressive disorder [Citation27]. Caregivers were asked to assess their child’s depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms are a psychological modifying variable in the HBM.

Social support

Participants rated their social supports using the ENRICHD (Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease) Social Support Inventory (ESSI [Citation28]). They rated whether they had someone to whom they felt close, who could give them advice, show love and affection and provide emotional support at difficult times on a scale from None of the time (1) to All of the time (5), so that higher scores indicate better access to social support. Low support in the ENRICHD has been defined as 2 or more items ≤2, or 2 or more items ≤3 and an adjusted overall score ≤18 [Citation29]. Caregivers were asked to assess the social support of their child with SCD. Social support is a potential cue to action in the HBM.

Health literacy

Health literacy, or the ability to obtain, read, understand and use healthcare information to make appropriate health decisions, is an important component of the HBM [Citation30]. Health literacy was evaluated using the Brief Health Literacy Screening, three items rated on a five-point scale indicating confidence in completing medical forms without assistance, need to ask for help in reading health-related materials and problems with learning about SCD due to difficulty understanding written information. Inadequate health literacy can be determined from one or a combination of all three of these questions [Citation31,Citation32]. Responses of ‘somewhat’ or better for the question ‘How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?’ has been used to define ‘good’ health literacy [Citation31]. Caregivers were asked to assess their own health literacy. Health literacy is a modifying variable between education and ultimate health behaviours within the HBM.

Spirituality

An emerging focus of study within the HBM is on spirituality as a barrier or resource for positive health action [Citation33] particularly for African Americans [Citation34]. Participants rated how spiritual they considered themselves to be using a single item ‘how spiritual or religious do you consider yourself (or your child) to be,’ from very (1) to not at all (4). Based on the distribution of the responses and for ease of analysis, we dichotomized the variable into ‘very’ spiritual (option 1) and ‘not very’ spiritual (option 2,3,4). Caregivers were asked about the spirituality of their child with SCD.

Missed appointments

Adults with SCD reported on whether they had missed an appointment within the previous twelve months by selecting from a potential list of contributing factors for missed appointments. Caregivers reported on whether their child with SCD missed an appointment within the previous twelve months in the same manner. The CDRN survey also asked what cues patients and caregivers preferred as reminders about appointments (e.g. text messages, telephone calls).

Statistical analysis

Study data were collected, de-identified, and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Vanderbilt University [Citation35]. Data were entered either directly into the database as participants completed them on computer tablets or transcribed from paper-based surveys. Surveys were excluded if they were missing information on age, site, or sex. We used descriptive statistics to summarize the social determinants of health and responses to questions in the remaining surveys. Means and inter-quartile ranges were used to describe continuous variables, and proportions were used for categorical variables. We also recorded the percent of missing responses for each survey item.

We created logistic regression models for the outcome measure of missing appointments using variables from the HBM i.e. social determinants of health (sex, age, ability to pay bills), depressive symptoms, health literacy, spirituality, and social support. Logistical regression models were based on the constructs of the HBM that were available. We initially created a model for all participants, but given that adults and children with SCD have important differences in health care, we created a variable that dichotomized adults and children. When we saw statistically significant differences in our regression for all adults compared with children, we created two new models for adults and children separately to further evaluate these differences. Analyses were performed in R version 3.2.2, and p-values were considered significant if < 0.05. [Citation36]

Results

Demographics

A total of 573 individuals with SCD (adults and caregivers of children with SCD) completed the surveys. After excluding surveys missed age, sex or site, our final sample for analysis included 211 adults with SCD and 331 caregivers of children with SCD (n = 542). shows distribution by sites of adults and pediatric patients.

Table 1. Socio-demographics for participants with sickle cell disease (N – 542).

Modifying variables in the health belief model vary among adults with SCD and children with SCD (as reported by their caregivers)

The most common education level for both adults with SCD and caregivers of children with SCD was ‘some college education.’ Forty-five percent of the total sample reported it was ‘somewhat’ to ‘very difficult’ to pay monthly bills. Over 76% of the total sample rated themselves as ‘fairly’ to ‘very’ spiritual or religious. The mean score on the PHQ-2 for depression in adults (1.46 ± 1.55) was higher than what caregivers reported for children (0.84 ± 1.26), but both below the cut-off for depression screening of 3.0. However, 49 (23.2%) adults and 47 (14.2%) children (as reported by their caregivers) had scores of 3 and above (). In our population, 18% of all individuals with SCD evidenced moderate to severe depressive symptoms based on the PHQ-2 scores (adults: 23%, children (reported by caregivers): 14%). These numbers are slightly lower compared with other studies in SCD, where rates of moderate to severe depressive symptoms have ranged from 26% to 57% [Citation37–39]. Differences in the depression screening tool used could likely account for this difference. The majority of adults and children (as reported by their caregivers) rated social support and health literacy as ‘good’ (85% and 74.9% respectively).

Table 2. Scores on standardized measures for the participants (n = 542) with sickle cell disease.

Forgetfulness was the most common reason for missed appointments and participants thought a reminder would help them best

A majority of children (reported by caregivers: 65%) and adults (87%) missed an appointment over the past year (), although most also reported that they called ahead. The most common reason for children and adults missing an appointment was forgetting about the appointment (adults: 36%, children (reported by caregivers): 26%). The next most common reason for adults was that the time did not work for them (29%), and for caregivers of children was not having a ride to get to the appointment (23%). The most common reason for not calling when they missed an appointment was forgetting to call (58%). A majority of participants thought a reminder would help them make sure they got to clinic appointments (75%). Over half wanted a text message (53%) or a phone call (61%). Most people wanted a reminder the day of or day before the appointment (41%).

Table 3. Responses to questions about appointment keeping (n = 542).

Missed appointments were associated with age, financial security, spirituality, and health literacy

Children were less likely to miss appointments than adults (Odds Ratio (OR)% 0.22; 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = [0.10, 0.51]) (). For the full sample, difficulty paying bills (OR = 1.70; 95% CI = [1.04, 2.80]) and less reported spirituality (OR = 1.83; 95% CI = [1.13, 2.94]) was associated with missing appointments. Among adults, younger age was associated with missing appointments (OR = 0.95; 95% CI = [0.91, 0.99]). For adults, difficulty paying bills (OR = 4.99; 95% CI = [1.20, 20.7]) and higher literacy (OR = 4.64; 95% CI = [1.33, 16.2]) were associated with missing appointments. For children with SCD, younger age was associated with more missed appointments (OR = 0.94; 95% CI = [0.88,1.00]).

Table 4. Logistic regression model for missed appointment with variables from the health belief model.

Discussion

Understanding factors that influence missed appointments is important when considering effective strategies to improve the care of individuals with SCD. Our manuscript is one of the first to describe associations between components of the HBM and missed appointments among individuals with SCD. In our study, we identified the reasons for missed appointments at multiple sickle cell centres across the U.S. We found that some, but not all, modifiers within the HBM that were available to us were associated with missed appointments for individuals with SCD. Children and adults with SCD differed with regard to modifiers of the HBM that were associated with the outcome, indicating potentially different targets for improving clinic appointment keeping. Participants also thought that having better cues to action, like reminders for clinic appointments would improve their attendance. Our findings are consistent with findings from other research that have examined barriers and facilitators to appointment keeping for adolescents with SCD and caregivers of children with SCD [Citation9,Citation10]; however, research concerning appointment keeping for adults with SCD is limited.

The CDRN data collection allowed, for the first time, examination of factors associated with appointment keeping for adults with SCD across the U.S. Consistent with other research, younger, transition-age adults (18 to 25 years) were most likely to miss appointments [Citation40,Citation41]. The disconnect between pediatric and adult care is a well-known gap [Citation42], with evidence that patients are unprepared for differing expectations in the adult medical world, i.e. making appointments without the assistance of family or staff. Interestingly, younger children had more missed appointments than older children, which may be due to caregivers of younger children needing to get to work, so they miss more appointments, as the caregiver is responsible to get the appointment. However, once the young adult with SCD transitions to adult care, they miss more appointments because they are more on their own. Further, it was surprising that higher health literacy was associated with missed appointments for adults in our study. Upon closer examination, common reasons that individuals with high health literacy missed appointments were because they did not want to miss school or work, and they did not know or forgot they had an appointment. Adults with higher literacy may have more responsibilities (e.g. school and work) and if they are in better health and perceive that other aspects of their lives are more important, they may not think they needed to be seen. Further study is needed on the role that health literacy plays in appointment keeping and other positive health behaviours for patients with SCD.

We included spirituality as a modifier of the HBM in the present study. In a recent review [Citation43], the importance of spirituality/religiosity in relation to improved coping and decreased health care utilization for patients with SCD was supported. We found significant associations between increased reported spirituality and missed appointments in all individuals with SCD, and further exploration of strategies to explicitly tap into this potentially important coping mechanism is needed.

Since missed appointments are costly and contribute to increased acute care utilization [Citation16,Citation17], strategies to improve appointment show rates could decrease admissions and readmissions. The most common reason for missed appointments was forgetting, consistent with previous literature [Citation10]. The HBM’s cues to action could be helpful in improving adherence with appointments (). Three quarters of participants thought that reminders would be of help to them in making it to appointments. The most common way they wanted reminders was through phone calls. However, for adults aged 18 to 30 years, compared with older adults, text message reminders were preferred (text message: 63%, phone call: 57%), demonstrating that different age groups prefer different types of reminders. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis looked at reminders for clinic appointments [Citation44]. It was found that people receiving notifications improved clinic attendance by 23%. However, it was also found that multiple notifications were significantly more effective than single notifications and voice notifications were more effective than text notifications. Therefore, clinic reminders, which are not done consistently at all the sites in this study, could help improve attendance.

Among the factors that influenced missed appointments in adults, financial insecurity seemed to have played a major role in missing appointments, as adults with SCD who had difficulty paying bills were five times more likely to miss an appointment. Financial insecurity would be consistent with our findings that participants missed appointments because they couldn’t get to the appointment (transportation issues), didn’t have the money, or did not have health insurance or co-pay for the appointment. Improving the ability to get to appointments and meet expenses associated with appointments could be an important focus in improving clinic attendance. These findings may also highlight cognitive challenges [Citation45] and vulnerability of the SCD population. There is recognition that cognitive impairment in adults with SCD may contribute to the risk of unemployment, while depression has been correlated to the chronic, unpredictable pain events and psychosocial distress associated with SCD [Citation46]. Providers must be vigilant that individuals with SCD and cognitive impairment, and/or those with lower income and depressive symptoms may require more attention to increase outpatient and decrease acute healthcare utilization, where appropriate.

Several limitations in interpreting these results are noted. First, findings are based on survey self-reports, which can lead to recall bias. Although the majority of adults with SCD and children, as reported by their caregivers, had missed an appointment, information about missing appointments was based on self-report only. Future studies should validate self-reports about missing appointments with the electronic health record. Second, while we were able to include respondents from three regions of the U.S. in the survey, responses may differ from other regions. Third, this was a convenience sample of participants who presented to clinical sites providing SCD care. While their responses may or may not be representative of the broader population of patients with SCD and their families, the clinical sites themselves did range from academic medical centres to community clinics. Fourth, spirituality was measured with a single-item. Although the item is part of a validated instrument [Citation47], future studies with a complete spirituality scale could be used to further evaluate the relation between spirituality and missing appointments. Fifth, we do not know if the caregiver may have answered survey questions about themselves in response to the prompt you/your child. However, coordinators who administered the surveys did not report that caregivers expressed confusion with the survey instructions in this regard. Finally, we were limited in what variables we could evaluate in the present study, because we were using an existing survey. Insurance coverage, another potentially important variable in health care utilization, was not captured in these surveys. Also, statistically, some confidence intervals in the regression models were very wide, suggesting a great deal of variability within the sample on some variables. Direct evaluation of other components of the HBM and potentially other important characteristics of participants was not possible. Further research is needed on the impact of relevant variables such as cognitive impairment and access to quality care on missed appointments for populations of individuals with SCD and their families.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrated that modifiers of the HBM influence missed clinic appointments among individuals with SCD across the U.S. Our findings support the importance of understanding social determinants of health and other variables from the HBM in keeping clinic appointments, and highlight strategies individuals with SCD believed would help them with keeping clinic appointments. Among strategies, reminders that are personalized to voice or text messages based on preferences, improving the ability to get to and pay for appointments, and appealing to a person’s spirituality may improve clinic attendance. Our findings suggest potential targets to improve appointment show rates but also suggest areas in need of further study.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the members of the Vanderbilt-Meharry Center of Excellence in Sickle Cell Disease for their thoughtful and helpful comments in reviewing the manuscript; Bertha Davis for regulatory matters; Brittany L. Myers, DNP, RN for support with patient recruitment; and Natasha Dean for assistance with preparation of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Robert M. Cronin http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1916-6521

Marsha Treadwell http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0521-1846

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brousseau DC, Panepinto JA, Nimmer M, et al. The number of people with sickle-cell disease in the United States: national and state estimates. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(1):77–78.

- Mvundura M, Amendah D, Kavanagh PL, et al. Health care utilization and expenditures for privately and publicly insured children with sickle cell disease in the United States. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53(4):642–646.

- Steiner CA, Miller JL. Sickle cell disease patients in US hospitals, 2004. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006.

- Yusuf HR, Atrash HK, Grosse SD, et al. Emergency department visits made by patients with sickle cell disease: a descriptive study, 1999–2007. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 Suppl):S536–S541. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.001. PubMed PMID: 20331955; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4521762.

- Mehta SR, Afenyi-Annan A, Byrns PJ, et al. Opportunities to improve outcomes in sickle cell disease. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Jul 15;74(2):303–310. PubMed PMID: 16883928.

- Yawn BP, Buchanan GR, Afenyi-Annan AN, et al. Management of sickle cell disease: summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. JAMA. 2014;312(10):1033–1048. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10517. PubMed PMID: 25203083.

- Ware RE. How I use hydroxyurea to treat young patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2010;115(26):5300–5311. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-04-146852. PubMed PMID: 20223921; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2902131.

- Thornburg CD, Calatroni A, Telen M, et al. Adherence to hydroxyurea therapy in children with sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr. 2010;156(3):415–419. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.09.044. PubMed PMID: 19880135; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3901082.

- Modi AC, Crosby LE, Hines J, et al. Feasibility of web-based technology to assess adherence to clinic appointments in youth with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34(3):e93–e96. doi:10.1097/MPH.0b013e318240d531. PubMed PMID: 22278205; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3311776.

- Crosby LE, Modi AC, Lemanek KL, et al. Perceived barriers to clinic appointments for adolescents with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(8):571–576. doi:10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181acd889. PubMed PMID: 19636266; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2750821. eng.

- Bollinger LM, Nire KG, Rhodes MM, et al. Caregivers’ perspectives on barriers to transcranial Doppler screening in children with sickle-cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(1):99–102. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22780. PubMed PMID: 20842753.

- Raphael JL, Shetty PB, Liu H, et al. A critical assessment of transcranial Doppler screening rates in a large pediatric sickle cell center: opportunities to improve healthcare quality. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51(5):647–651. doi:10.1002/pbc.21677. PubMed PMID: 18623200.

- Jacob E, Childress C, Nathanson JD. Barriers to care and quality of primary care services in children with sickle cell disease. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(6):1417–1429. doi:10.1111/jan.12756. PubMed PMID: 26370255.

- Schlenz AM, Boan AD, Lackland DT, et al. Needs assessment for patients with sickle cell disease in South Carolina, 2012. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(1):108–116. doi:10.1177/003335491613100117. PubMed PMID: 26843676; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4716478.

- Brodsky MA, Rodeghier M, Sanger M, et al. Risk factors for 30-day readmission in adults with sickle-cell disease. Am J Med. 2017. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.12.010. PubMed PMID: 28065771.

- Kheirkhah P, Feng Q, Travis LM, et al. Prevalence, predictors and economic consequences of no-shows. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;16:533. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-1243-z. PubMed PMID: 26769153; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4714455. eng.

- Davies ML, Goffman RM, May JH, et al. Large-scale no-show patterns and distributions for clinic operational research. Healthcare (Basel). 2016;4(1). doi:10.3390/healthcare4010015. PubMed PMID: 27417603; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4934549. eng.

- Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Behav. 1984;11(1):1–47.

- Stretcher VJ, Rosenstock IM. The health belief model. In: Baum A, editor. Cambridge handbook of psychology, health and medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. p. 113–117. ISBN 0521430739.

- Campbell B, Staley D, Matas M. Who misses appointments? An empirical analysis. Can J Psychiatry. 1991;36(3):223–225. PubMed PMID: 2059940.

- Dove HG, Schneider KC. The usefulness of patients’ individual characteristics in predicting no-shows in outpatient clinics. Med Care. 1981;19(7):734–740. PubMed PMID: 7266121.

- Goldman L, Freidin R, Cook EF, et al. A multivariate approach to the prediction of no-show behavior in a primary care center. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142(3):563–567. PubMed PMID: 7065791.

- Neal RD, Lawlor DA, Allgar V, et al. Missed appointments in general practice: retrospective data analysis from four practices. Br J Gen Pract. 2001 Oct;51(471):830–832. PubMed PMID: 11677708; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1314130.

- Mellins CA, Havens JF, McDonnell C, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral medications and medical care in HIV-infected adults diagnosed with mental and substance abuse disorders. AIDS Care. 2009;21(2):168–177. doi:10.1080/09540120802001705. PubMed PMID: 19229685; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5584780. eng.

- Rosenbloom ST, Harris P, Pulley J, et al. The mid-south clinical data research network. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):627–632. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002745. PubMed PMID: 24821742; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4078290. eng.

- Haywood CJ, Lanzkron S, Bediako S, et al. Perceived discrimination, patient trust, and adherence to medical recommendations among persons with sickle cell disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1657–1662. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2986-7. PubMed PMID: 25205621; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4242876.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292.

- Vaglio JJ, Conard M, Poston WS, et al. Testing the performance of the ENRICHD social support instrument in cardiac patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:24. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-2-24. PubMed PMID: 15142277; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC434528.

- Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, et al. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the enhancing recovery in coronary heart disease patients (ENRICHD) randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3106–3616.

- Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1.

- Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561–566.

- Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, et al. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):874–877. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x. PubMed PMID: 16881950; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1831582. eng.

- Miller WR, Thoresen CE. Spirituality, religion, and health: An emerging research field. Am Psychol. 2003;58(1):24–35. PubMed PMID: 12674816.

- Swanson L, Crowther M, Green L, et al. African Americans, faith and health disparities. Afr Am Res Perspect. 2004;10(1):79–88.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. PubMed PMID: 18929686; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2700030.

- R Core Team, Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R foundation for Statistical Computing; 2005.

- Benton TD, Boyd R, Ifeagwu J, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis in adolescents with sickle cell disease: a preliminary report. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(2):111–115.

- Hasan SP, Hashmi S, Alhassen M, et al. Depression in sickle cell disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95(7):533.

- Jenerette C, Funk M, Murdaugh C. Sickle cell disease: a stigmatizing condition that may lead to depression. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2005;26(10):1081–1101. doi:10.1080/01612840500280745. PubMed PMID: 16284000.

- Wojciechowski EA, Hurtig A, Dorn L. A natural history study of adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease as they transfer to adult care: a need for case management services. J Pediatr Nurs. 2002;17(1):18–27. doi:S0882596302311047 [pii]. PubMed PMID: 11891491; eng.

- Paulukonis ST, Harris WT, Coates TD, et al. Population based surveillance in sickle cell disease: methods, findings and implications from the California registry and surveillance system in hemoglobinopathies project (RuSH). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(12):2271–2276. doi:10.1002/pbc.25208. PubMed PMID: 25176145; eng.

- Crosby LE, Quinn CT, Kalinyak KA. A biopsychosocial model for the management of patients with sickle-cell disease transitioning to adult medical care. Adv Ther. 2015;32(4):293–305. doi:10.1007/s12325-015-0197-1. PubMed PMID: 25832469; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4415939. eng.

- Clayton-Jones D, Haglund K. The role of spirituality and religiosity in persons living with sickle cell disease: a review of the literature. J Holist Nurs. 2016;34(4):351–360. doi:10.1177/0898010115619055. PubMed PMID: 26620813; eng.

- Robotham D, Satkunanathan S, Reynolds J, et al. Using digital notifications to improve attendance in clinic: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(10):e012116. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012116. PubMed PMID: 27798006; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5093388. eng.

- Sanger M, Jordan L, Pruthi S, et al. Cognitive deficits are associated with unemployment in adults with sickle cell anemia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2016;38(6):661–671. doi:10.1080/13803395.2016.1149153. PubMed PMID: 27167865; eng.

- Edwards CL, Green M, Wellington CC, et al. Depression, suicidal ideation, and attempts in black patients with sickle cell disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(11):1090–1095. PubMed PMID: 19998636; eng.

- Kass JD, Friedman R, Leserman J, et al. Health outcomes and a new index of spiritual experience. J Sci Study Relig. 1991;30: 203–211.