ABSTRACT

This paper investigates how the digitized fashion market is transformed through hashtagged visual and textual brand and consumer conversations on Instagram. The study draws on assemblage and performativity theory to investigate how the American Apparel brand and its consumers develop a common visual rhetoric in opposition to mainstream fashion discourse, and uses network analysis to depict its network effects on the digitized fashion market. Drawing on multiple data sets consisting of visual, textual, and networked data, this paper finds that both brand and consumer discourse stabilize brand-related ideological fashion discourse while infiltrating prevalent mainstream fashion rhetorics. Our findings provide evidence of the visual and discursive performativity of the fashion market assemblage on Instagram and related market dynamics on a network level.

Introduction

If markets are plastic, fluid entities (Nenonen et al. Citation2014) constituted by complex exchanges and negotiations of shared understandings (Lusch and Watts Citation2018), digital markets are even more fluid, characterized by massive shifts in communication power and market transformation through networking (Castells Citation2009). By opening spaces and marketplaces that are unprecedented in their levels of ubiquity, fluidity, and interactivity, a more diversified assemblage of market actors shape and change whole markets, such as the fashion market, through networked activities in digital marketplaces (Crewe Citation2013; Scaraboto and Fischer Citation2013). This study seeks to advance the understanding of digital market dynamics and investigates how visual and textual conversations among market actors on Instagram potentially transform shared understandings that constitute the fashion market.

Instagram has become an increasingly important digital fashion marketplace where a multitude of market actors post pictures, interact, communicate, negotiate, and also launch brands or products. The influencer market of Instagram is growing rapidly, and in the meantime consumers can shop on millions of business accounts. Instagram has become a primarily visual digital marketplace where user interests and commercial interests meet and collide when, for instance, business Instagram accounts are linked to retail pages through advertorials by influencers, or direct links in Instagram stories. Marketplaces like Instagram are therefore interesting research contexts for the investigation of how digital markets are socially and materially constituted and transformed through primarily visual and hashtagged consumer-brand conversations.

Digital marketplaces like Instagram are not what we commonly think of in terms of “places” on digital platforms, says Daniel Miller in an interview with Janet Borgerson (Citation2016). Instead, social media is largely about genres of communication content. Accordingly, we regard Instagram not just as a common fashion marketplace, but also as a place where shared understandings of contemporary body aesthetics and beauty are negotiated among market actors – a genre which is firmly connected to the fashion market and which also enjoys massive visibility on Instagram. Consumers employ such communication in the form of fashion posts and brand content to gain publicity and fame (Arvidsson and Caliandro Citation2016; Marwick Citation2015; Rokka and Canniford Citation2016), but also to contest mainstream market ideologies.

On a market-level, prior research has investigated the (de-)stabilizing potential of digital marketplace conversations among consumers (Giesler Citation2008; Presi, Maehle, and Kleppe Citation2016; Rokka and Canniford Citation2016; Scaraboto and Fischer Citation2013), but little attention has been given to conversations among different market actors, such as brands and consumers, and their impact on institutionalized markets. Giesler (Citation2008), for example, offers a resistant, dramatized account of market change in the form of the war on downloading. Scaraboto and Fischer (Citation2013) offer general advancement of how consumers attempt to expand the logics of mainstream markets. On a brand-level, Rokka and Canniford (Citation2016) describe how selfies and selfie sharing practices can destabilize the key layers through which brands are assembled. Similarly, Presi, Maehle, and Kleppe’s (Citation2016) study of brand selfies emphasizes the potential of visual rhetorics to join marketplace conversations and alter existing brand meanings by creating a social imaginary around a focal brand. Murray (Citation2015) finds that the genre of the selfie is also used as a form of aesthetic and political resistance against mainstream ideologies. The networked character of digital markets bears the potential for market actors to scale up conversations to a market level, which, eventually, initiates market change. But how do visual and textual networked marketplace conversations on Instagram challenge dominant market ideologies, or even change market-level understandings of institutionalized markets?

In order to develop an understanding of the market-level consequences of visual and textual conversations on Instagram, we draw on assemblage theory and a performative view as an enabling lens. We explore market dynamics induced by a brand and its consumers, who collectively frame a visual rhetoric that seeks to infiltrate the aesthetic ideologies of the mainstream fashion market (defined by Scaraboto and Fischer (Citation2013, 1235) as an aggregation of “large, high-profile corporations with strong name brands”). In order to understand marketplace dynamics that result from networked visuals and texts, we investigate the visual rhetoric of the fashion brand American Apparel and its consumers related to recent body positivity discourse. We further aim to show how Instagram mediates communicative actions among brands and consumers and how they scale up to a market-level conversation.

This paper is organized as follows. First, we describe fashion marketplace conversations on Instagram, their visual rhetorics, and the recent discourse concerning utopian body aesthetics and body positivity. Second, we introduce our theoretical understanding of digital markets as performative assemblages. Third, we outline our methodology. Finally, we present our findings, discuss these with respect to prior literature, and provide implications for future research.

Fashion marketplace conversations on Instagram

The rise of fashion consumption on Instagram has transformed the dynamics of the fashion marketplace in terms of visual representation, consumption, and the networked flow of discourse (Schneier Citation2014). As the biggest digital fashion marketplace, Instagram frames a discursive space for marketplace conversations manifested in interaction, negotiation, and meaning exchange between brands and consumers related to cultural and aesthetic ideologies. Using Photoshopping and retouching technology, mainstream fashion visuals on Instagram portray the female body as an idealized, hourglass-figure body artefact that is thin, white, and without any flaws – in other words, the perfect body (Patterson and Elliott Citation2002). Consumers on Instagram are scrutinized and evaluated by body attributes, hashtagged as #thighgap or #bodygoals that are frequently attached to fashion-related content. Consequently, consumers who are “unable to live up to increasingly narrow standards of female beauty and sex appeal” (Gill Citation2008, 44) feel socially stigmatized through forms of body shaming (Dillig Citation2017) and aesthetic exclusion from markets that form around the body (Scaraboto and Fischer Citation2013).

However, consumers increasingly join marketplace conversations that contest these narrow standards of the fashion market and the “digital Botox” applied to the human body through the built-in Photoshopping tools of Instagram. Rapper Kendrick Lamar addresses these issues in his song “HUMBLE.,” which was the second most-streamed song of 2017 with over 400 million audio streams (Harling Citation2017):

I’m so fucking sick and tired of the Photoshop

Show me something natural like afro on Richard Pryor

Show me something natural like ass with some stretch marks. (Duckworth, Williams II, and Hogan Citation2017)

The central trope of these contesting marketplace conversations is the culturally scripted #bodypositivity hashtag (Abidin Citation2016), which “ … is about accepting one’s body as it is, regardless of what is deemed socially acceptable or beautiful” (Salam Citation2017), embracing the ethos of aesthetically including each and every body, even the “flawed self” (Featherstone Citation2010, 195; Gill Citation2008). Body-positive consumers strive for emancipation from the beauty imperative and express their concerns by means of networked visual representation, where bodies are “known, understood and experienced through images” (Coleman Citation2008, 163; Tiidenberg and Gómez Cruz Citation2015).

Some brands progressively go along with consumers’ marketplace conversations contesting the ideology-infused practices of Photoshopping and retouching bodies, and align themselves with these consumers’ positions. For example, retailer ASOS recently announced that the company will no longer Photoshop their models (Dillig Citation2017), and Getty Images, the world’s largest stock photo provider, introduced a new policy in October 2017 which complies with a French law that requires Photoshopped images to be labeled (Quinn Citation2017).

A prime example of a brand that embraces body-positive marketplace conversations is the fashion brand American Apparel. American Apparel lobbies for acceptance of all forms of bodies and employs a liberal discourse by playing with social conventions in its assemblage of visual genres. Additionally, the brand frequently initiates campaigns emphasizing their values of naturalness, diversity, empowerment, inclusiveness, human rights, and freedom (American Apparel Citation2017). Along with an overall visual rhetoric that corresponds with mainstream market ideologies, the brand also integrates countercultural visual genres that, as Scaraboto and Fischer (Citation2013, 1252) describe, “lack normative legitimacy in the wider society in which the organizational field of fashion is situated” by, for example, supporting political movements that align with their values (e.g. the LGBTQA+ community). The brand’s visual rhetoric strongly corresponds with consumers’ body positivity discourse, introducing elements of a renewed, shared understanding of fashion and aesthetics on Instagram.

This first empirical evidence of fashion discourse shows that Instagram as a dynamic marketplace does not necessarily imply monetarized exchanges (Kozinets Citation2002; Martin and Schouten Citation2014) but rather massive textual and visual marketplace conversations and negotiations (Bode and Kjeldgaard Citation2017; Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2007; Lusch and Watts Citation2018; Mason, Kjellberg, and Hagberg Citation2015). Market exchange is then a form of collaborative “visibility labor” (Abidin Citation2016, 89): an “affective labor” or “series of activities” that produces “informational and cultural content” (Lazzarato Citation1996, 137; Wissinger Citation2007) in the form of networks and flows, and which seeks to contest mainstream ideologies through circulating, watching, and modifying networked “flows of images” (Carah and Shaul Citation2016, 71).

Our study adopts the concept of visibility labor to illustrate how consumer-brand conversations on Instagram alter fashion discourse and infiltrate the dominant visual rhetoric of the mainstream fashion market on Instagram. We apply a performativity lens to illustrate collaborative visibility labor among brands and consumers as market actors. Assemblage theory helps us to understand the materiality and expressivity of visuals, and informs our analysis of the networks of communicative content and its dynamics on a market level.

A performative approach to digital market assemblages

In our analysis of the digital fashion market on Instagram, we draw on DeLanda’s (Citation2006, Citation2016) perspective of markets as assemblages. Assemblages are ad hoc groupings of elements, vibrant things of all sorts (Bennet Citation2010) interacting with each other, that is, “people and the material and expressive goods people exchange” (DeLanda Citation2006, 17). Assemblage theory draws attention to the agentic aspect of the digital fashion market as being “part and a consequence of an assemblage with different actors, agencies, materialities, and relations” (Bode and Kjeldgaard Citation2017, 253). Assemblages’ agentic characteristic of “to make something happen” (Bennet Citation2010, 24) derives from the vital forces of their elements but also from the assemblage as a whole. An assemblage perspective is therefore a powerful practice lens that directs attention to Instagram as a “locale” (DeLanda Citation2016) where market-level dynamics result from visual “micro” performances, and vice versa. We apply a performativity lens to complement assemblage theory and illuminate the effects of the micro-level socio-material elements of the digitized fashion market on Instagram – in our case, networked visual and textual rhetorics. A performativity lens draws attention to the performative enactment of meanings and materialities that shape the market assemblage as a whole (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2006).

Assemblages consist of multiple heterogeneous components that interact with each other in ways that can either stabilize or destabilize the identity of an assemblage (DeLanda Citation2006). From this perspective, digital markets are not only comprised of people as actors, but also physical elements, texts, visuals, and digital technologies that facilitate access to a brand (Parmentier and Fischer Citation2015). Components of an assemblage exercise different sets of capacities, which are material and expressive. Conjoined material and expressive capacities create socio-materiality through interactive processes which include rhetorics, discourse, and other forms of conversations among actors (DeLanda Citation2006). On Instagram, these capacities become performative or, as Callon (Citation1998) suggests, entities become performative when they create a socio-material assemblage comprised of concrete tangibilities (e.g. visuals and texts) forming social entities (e.g. communities and networks), and vice versa. Our perspective of the fashion market on Instagram as a socio-material assemblage therefore encompasses various actors – such as consumers and brands – as well as products, hashtags, comments, and an abundance of visuals that frame networked marketplace conversations.

Marketplace actors may cite, reiterate, reuse, and re-perform these socio-material components (Butler Citation1993; Derrida Citation1988). Citationality refers to “the property of iterability, the reproducibility of a form, and the norm that governs its intelligibility and producibility, over distinct discursive time-spaces” (Nakassis Citation2012, 626). The digital fashion market on Instagram, for example, is dominated by citations of brand visuals and portrayals of beauty that are used as points of reference. However, citational acts are not simple reproductions but rather reflexive in that they point to ways in which they are not what they reanimate (Nakassis Citation2013). Consumers, for example, may cite conventional beauty ideals and fashion brands to demonstrate either their compliance with these standards and apply this to their self-portrayals, or, in a sarcastic or ironic manner, to instead express their disbelief. Digital markets provide a platform for such reflexive citations, diverse ideological struggles, and attempts to (re-)appropriate cultural significations in diverse fields. Digital markets are therefore hotbeds of cultural production, not only for establishing mainstream ideologies but also for breaking and resignifying the “oppressive” rhetorics of mainstream markets through reiterative performances (Kotz Citation1992, 84). Reiterative performances imply that a “performance” is not a singular “act” or event, but a ritualized production of norms (Butler Citation1993) of, for example, visual body performances in the mainstream fashion market (Wissinger Citation2007).

As such, socio-material assemblages undergo constant formation and negotiation. They are characterized by relations of exteriority, that is, that components of an assemblage may be detached from it, put into another assemblage, or enter new ones (DeLanda Citation2016). Further, assemblage theory’s flat ontology includes entities at all levels – individual and group, as well as macro-level entities – to enhance understanding of the fluid character and dynamics of assemblages. It is this quality of assemblage theory that allows us to understand how the “materiality of bodies” (Butler Citation1993, 1) is negotiated in digitized markets as an assemblage of individuals, brands, materialities and markets. The performative nature of body positivity discourse, for example, enters the market assemblage by naming subversive bodies and body parts and thus bringing them into being, which adds a different rhetoric to the mainstream fashion market. Destabilization in assemblages occurs when distinctions are drawn, or conflicts disassemble existing relations, such as mainstream body depictions. In contrast, assemblages are stabilized when social conventions and field-specific homogenous repertoires are reiterated (DeLanda Citation2016).

On a “micro-level,” we look at visuals and text as discursive articulations of (de-)codified conventions to arrive at a better understanding of the (de-)stabilizing effects of concrete elements on digital market assemblages (DeLanda Citation2016). We investigate material components of visuals referring to tangible physical elements (Parmentier and Fischer Citation2015; Rokka and Canniford Citation2016) and expressive components including language, symbols, and various other forms of expressions (DeLanda Citation2006) which discursively create and shape digital markets through their visual and textual rhetoric. On a market-level, discursive articulations of body-positive visuals and according hashtagging (re-)produce and refigure material bodies that add exteriority to the market assemblage: or in other words, initiate market change. Our study aims to understand these market dynamics of digitized markets through fashion-related, networked communication. Our methodological approach aims to capture the performative rhetoric of visuals, hashtags, and comments and investigates how this rhetoric creates, is molded into, and changes the digital market assemblage.

Methodology

For our empirical investigation, we chose a brand that consistently rejects mainstream visual rhetorics of mainstream fashion brands in favor of natural representations of the body, the fashion brand American Apparel. The Instagram account of American Apparel (@americanapparelusa) enjoys a large, heterogeneous network of followers who provoke discourse around counter-ideological visual performances of the human body. The brand embraces a “can-do” spirit with their slogan “Ethically made – Sweatshop Free.” American Apparel’s corporate website emphasizes the brand’s dedication to naturalness, empowerment of people, freedom, and diversity. The brand rarely works with influencers, but features visuals of consumers who tag their posts on the brand’s Instagram network with corresponding hashtags. American Apparel’s Instagram account currently attracts 2 million followers.

We applied digital methods (Rogers Citation2009) and critical visual analysis (Rose Citation2012) in order to investigate American Apparel’s hashtagged visuals and complementary consumer-generated content and visualize brand-consumer conversation of American Apparel on a market-level. For a year and a half, we followed and interacted with the American Apparel account and its consumers on Instagram. We downloaded and archived 2528 from a total of 4842 American Apparel Instagram posts manually in April 2017. We focused on brand posts that triggered extensive discourse related to ideological struggles around the human body in the comment section to capture the performativity of brand visuals. We selected posts with (1) the highest number of comments and (2) the highest number of multiple commentators. The final sample of brand-generated content comprised 50 posts with more than 8000 consumer comments in total.

After archiving the sample of brand-generated content and corresponding consumer responses, we focused on hashtagged consumer-generated content on the brand’s Instagram network. The digital data collection tool Netlytic (netlytic.org) allows for such a network analysis enabling the downloading of Instagram data sets with specific search queries, for example, single #hashtags or geographical coordinates. Using Netlytic, we downloaded an additional data set of 10,000 posts tagged with the hashtag #americanapparel. Specifically, we used a single query for a single hashtag, that is, a query identifying 10,000 posts most recently tagged with #americanapparel in April 2017. The Netlytic data set also provided metadata, that is, links to consumers’ posts, timestamps, captions, hashtags, likes, and comments. We used this metadata to access consumer-generated visuals in order to contrast brand and consumer-generated content (Caliandro and Gandini Citation2017). We focused on consumer-generated visuals tagged with body positivity related hashtags to illustrate how brand discourse resonates with consumers. The final sample of consumer-generated content comprised 50 posts to remain congruent with the amount of brand-generated content. To complement our data with contemporary shifts in aesthetic ideologies in the fashion market, we additionally examined related media coverage in newspapers, magazines, and blogs, such as Vogue, Business of Fashion, and The New York Times. In total, we collected 40 articles related to body positivity. Sampled articles supplement our analysis of the ideological discourse surrounding the human body as depicted in the digital fashion market.

We applied critical visual analysis techniques (Rose Citation2012) to contrast the 50 brand posts that triggered textual consumer discourse with the 50 consumer-generated posts tagged with #americanapparel. Critical visual analysis uncovers the composition of visual conversations and how these counter-ideological visuals discursively add exteriority to the marketplace assemblage as a whole. We open coded and counted the frequency of material and expressive visual elements, developed interpretive categories, and identified recurrent patterns in the visuals (Rokka and Canniford Citation2016; Rose Citation2012). Whereas material components are tangible, physical objects, including consumers or physical products (Parmentier and Fischer Citation2015), expressive elements refer to communicative elements, such as brand narratives, brand aesthetics, or consumer gestures used for signaling, for example, class, or gender (Alexander Citation2009; Rokka and Canniford Citation2016). Coding resulted in 36 material and 16 expressive themes which are presented in detail in Appendices A1 and A2. In order to understand the social effects of an image and how it relates to broader cultural meanings and practices, we considered its effects at the site of production, the site of the image itself, and the site of its audience (Rose Citation2012; Schroeder Citation2006), that is, how and where the visual was made, its composition, genre, content, and expressivity. The authors coded the visuals, captions, hashtags, and consumer comments independently and formed an interpretive group for constant comparison and to resolve inconsistencies (cf. Arvidsson and Caliandro Citation2016).

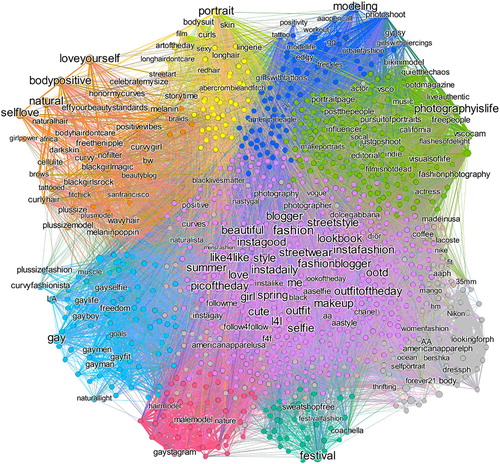

In order to analyze the impact of brand-consumer conversation and to contrast it with the mainstream fashion market on a network level, we conducted a hashtag co-occurrence analysis (Marres and Gerlitz Citation2016) using a python script to identify co-occurring hashtags with the hashtag #americanapparel in consumers’ posts of the Netlytic data set, for example, #americanapparel #bodypositive. We used Gephi to visualize the network of co-occurring hashtags, and analyzed the network by implementing a modularity clustering algorithm embedded in Gephi (Bastian, Heymann, and Jacomy Citation2009; Brandes et al. Citation2008). To ensure readability, we set a cut off level of 40 occurrences of hashtags for the final visualization of the co-hashtag analysis.

Findings

Our findings show that non-conventional visual rhetoric finds considerable resonance in digital markets. First, it initiates consumer compliance that results in three common performances that form and stabilize the brand-related assemblage in the digital fashion marketplace: refocusing; naturalizing/digital detoxing; and re-humanizing the human body. Second, co-hashtag analysis and thematic clustering show that citations in the form of hashtags provoke partial disassemblage of conventional mainstream market ideologies, and reconstruction of new discursive clusters. On a micro and meso-level, material and expressive components of hashtagged brand and consumer visuals accumulate into rhetoric clusters that are clearly distinctive to mainstream fashion discourse. In the following, we describe three visual performances that we distilled from brand and consumer-generated content.

Visual performativity on Instagram’s fashion marketplace

The assemblage of visual components ( and ) in Instagram’s fashion marketplace amounts to three performative effects on aesthetic market ideologies. First, we find that the visual rhetorics of the brand and its consumers aim at refocusing on the human body. Visual performances revolve around the human body itself instead of being framed around objects or products that shape and transform the human body. Second, American Apparel and its consumers engage in naturalizing the human body. Naturalizing implies that market actors perform a body that rejects the “digitally-botoxed” body on Instagram and engage in “detoxing,” that is, embracing the natural body that exhibits natural flaws. Third, we find a humanistic flavor in the visual rhetorics that emphasizes belief in the equality of bodies and people – re-humanizing the human body. In the following, we discuss these visual performances in detail.

Figure 2. Assemblage of visual components of consumer-generated content tagged with #americanapparel on Instagram.

Refocusing on the human body

Current fashion discourse in digital environments revolves around the aestheticized body, that is, shifting perception of body ideologies and the transformative quality of fashion on the mainstream fashion market. Refocusing refers to a visual rhetoric that frames discourse around the human body itself instead of fashion products. In contrast to influencer marketing rhetoric concerning products (Abidin Citation2016), we find that American Apparel and its consumers refocus on the human body ( and ). We find that in almost all visual performances of the brand (96%) and its consumers (100%) humans are present (Appendices A1 and A2) where the focal point of visual performances is the human body (brand-generated content (BGC) 94%/consumer-generated content (CGC) 98%). The genre of selfies (CGC 26%), a “self-portrait made in a reflective object or from arm’s length” (Tiidenberg and Cruz Citation2015, 78), automatically shifts the focal point of the visual towards the person taking the picture. Whereas self-shooting may be seen as a way to reach Instafame (Marwick Citation2015, 137), or to become a microcelebrity (Rokka and Canniford Citation2016), selfies taken by American Apparel consumers cite the brand’s rhetorics of body imperfection to proudly present and celebrate their own. This corroborates Murray’s (Citation2015) findings on practices of female selfie posting that are designed to embrace imperfections and advance a body-positive attitude (see also: Tiidenberg and Cruz Citation2015). Additionally, visuals mostly depict only one person (BGC 1.3 humans/CGC 1.2 humans), emphasizing her bodily manifestation with neutrally colored surroundings (BGC 73%/CGC 78%), that is, black, white, or gray with minimal or no décor at all (BGC 29%/CGC 34%). Expressive minimalism (BGC 41%/CGC 26%) is notably apparent. The gaze of the viewer is led directly towards the depicted body. In contrast to common representations on Instagram where bodies are shown in their momentousness, “waking up, enjoying a relaxing coffee moment, surrounded by objects, pointing towards the landscape or objects in the cityscape” (Manovich Citation2017, 125), American Apparel’s and its consumers’ body rhetoric is not contextualized but focused on the body. Brand-related body portrayals use the visual genres of still photography and human portraits, centering on the subject and the bodily existence of the depicted person. The genre of portrait does not “show off people in their most glamorous light” (Holbrook Citation2006, 491), but rather puts the person’s distinctive physical characteristics center stage. Close-ups reveal intimacy; they capture every wrinkle and sign of age or maternity, directing the viewer’s gaze to body parts that do not comply with conventional beauty standards. Visuals also only exhibit a small number of products. On average this is 2.5 pieces of clothing in BGC, and 1.9 pieces in CGC. Depicted humans most frequently wear colorful items (BGC 76%/CGC 40%) and underwear, bodysuits, and bikinis, presenting and focusing on their bodies even more (BGC 80%/CGC 82%). The bodysuit is an iconic product of American Apparel, accentuating and presenting the body silhouette with postures resembling artistic sculptures, mimicked by consumers in a similar sculpturesque manner that seductively exhibits body imperfections (bodysuits BGC 13%/CGC 14%; underwear BGC 16%/CGC 19%).

The visual performances in our sample predominantly focus on specific body parts, rarely depicting the body as a whole (BGC 7%/CGC 28%). Yet, this does not imply that the visuals express an explicit sexual rhetoric. Instead, consumers’ visuals focus on body parts that are prone to imperfection and flaws: stomach (BGC 93%/CGC 86%), chest (BGC 91%/CGC 88%), and thigh (BGC 93%/CGC 79%) – not (yet) to the extent the brand does, but with the same expressivity of seriousness and even more confidence. Another refocusing technique is the use of black and white photography, which we find in 12% of both BGC and CGC. Noir photography is a specific aesthetic genre of “pure” photography, where the photographer is very close to the subject, uses natural light rather than flash devices, and aims for high contrast of tones (Manovich Citation2017). In our case, this genre is used to foreground the body and center the subject in the visuals. Overall, these visuals exemplify consumer appropriations of American Apparel’s rhetoric and visual genres for depictions of their own – perfect or imperfect – bodies, referencing casual “that’s me” and “that’s how I am feeling today” selfie styles, provocatively bold as well as body celebratory brand rhetoric, and often with a rebellious, anti-stigmatization, self-assuring and emancipatory undertone.

Naturalizing/digital detoxing the human body

A second and related performative effect of the assemblage of visual components is naturalizing/digital detoxing of the otherwise filtered and Photoshopped – and thus “digitally-botoxed” – human body on Instagram. Naturalizing rhetorics aim to sever social conventions of the aestheticized body and emphasize its natural diversity and beauty. Naturalizing performances depict and express the human body in its naturalness. We find strong facial (BGC 82%/CGC 71%) and bodily (BGC 86%/CGC 64%) expressions of naturalness. Consumers cite the brand’s visual rhetoric and re-perform this specific form of naturalness in their own visuals.

Naturalizing rejects the fashion market’s normative ideologies of, for example, hairdressing: specifically the conventional expectation of black women straightening their hair. Natural hair is a central body positivity-related theme manifested by hashtag variations, for instance, #wavyhair, #curlyhair, #curls, #braids, and #longhairdontcare (). Naturalizing performances also reject socially and culturally-established body enhancement and beautification objects, for example, the bra. Yet, #nobra performances (BGC 13%/CGC 16%) upset some consumers, manifested in consumer discourse in the comment section, defending #nobra:

@[username] @[username] you should not be criticizing anyone about their appearance or telling them that they need a push up bra. ESPECIALLY someone as beautiful as @[username of the model] who has the nicest boobs in all the land. She. Is. Goals. You. Are. Jealous.

Closely related is the women’s countermovement #freethenipple addressing Instagram’s policy of banning female nipples (Rokka and Canniford Citation2016), which we also find in the body-positive discourse. Nipples under T-shirts on visuals are scarce, but still significant (both 9%), and celebrated as an aesthetic, natural, and life-sustaining feature of the human body that needs no beautifying support.

Naturalizing/digital detoxing also includes not retouching the flaws and imperfections of the human body by forgoing the use of makeup (BGC 82%/CGC 71%), or the retouching of freckles, birthmarks (BGC 24%/CGC 10%) or stretch marks, and cellulite (BGC 1%/CGC 5%). Consumers especially emphasize their stretch marks and cellulite to provoke body-positive comments to blatantly photographed imperfections. Performances of natural but socially-stigmatized features of the human body are accompanied by expressive elements. Self-touching gestures (BGC 31%/CGC 33%), and a playful, challenging (BGC 53%/CGC 40%), or seductive gaze (BGC 43%/CGC 32%) elevate the imperfect human body to the state of “delicate and precious” (Goffman Citation1979, 31). It is worth noting that in most of our cases the touching of the body expresses body pride (BGC 73%/CGC 44%), as appreciated by a consumer commenting on a visual of 62-year-old model Jacky O’Shaughnessy:

Beauty isn’t contained it is expressed “Beautiful Goddess” I hope to learn to go about this life with such pride, élégance and gorgeousness as this woman […] thanks @[username] @[username] for having such gallant attitude. You are def a rare breed of individuals who aren’t blinded by all this fakeness around us! Admiring beauty at its best […].

The slightly lower degree of body pride expressions in consumer-generated content suggests that continual resignifications of conventional body aesthetics in mainstream rhetoric complicates consumers’ endeavors towards accepting and loving their own natural body. Still, consumers highly emphasize their appreciation of the natural human body, uncoupling aesthetic inclusion from fashion’s obsession with perfection and youth, and paving the way for a more humane body rhetoric.

Re-humanizing the human body

Re-humanizing is a performative effect that partly builds on the two prior performances and de-objectifies the human body. It rejects the human body as an object of consumption (Bauman Citation2005) and aims to break objectification and the (male) gaze (Patterson and Elliott Citation2002; Schroeder and Zwick Citation2004). Instead, it emphasizes the body as a vital component of being human after all.

Women, by being aware of the male gaze and being the surveyed female (Berger Citation1972), intentionally assume the male gaze and break through it using unconventional angles, ironic gestures, and blatant postures in their visual representations. A self-confident (BGC 67%/CGC 70%) and genuine (BGC 65%/CGC 46%) look directly into the camera (BGC 83%/CGC 50%), a standing body position (BGC 70%/CGC 79%) with head and face visible in most cases, and photographed frontally, the body is portrayed at an equal eye level, leading the beholder’s gaze to direct eye contact with the depicted human. Eye contact further accentuates seriousness, emphasizing the problematic nature of stigmatizing humans whose bodies do not conform to the mainstream beauty regime. In comparison with the mainstream market, female breasts are not shown blatantly and not very often (BGC 30%/CGC 22%), unless in an ironic emphasis on imperfections to contrast sexualized depictions. Consumers embrace body performances of the brand as illustrated by the following consumer comment on a brand visual depicting 62-year-old Jacky:

I think she’s beautiful, confident and is doing what some women in their 20s and 30s don’t have the confidence to do. Society has poisoned several minds to think you have to look a certain way to be beautiful. You are and are going to be the way God intended and that is beautiful.

Here the female body is contrasted with “the passive object, the observed sexual/sensual body, eroticized and inactive” (Schroeder and Zwick Citation2004, 34). We also find a reversal of the male body rhetoric, that is, men express softness (BGC 70%/CGC 60%) and vulnerability (BGC 83%/CGC 30%), suggesting that all genders are entitled to this expressivity. However, the discrepancy in expressing vulnerability between brand and consumer-generated content suggests that male identity construction still focuses on conventional gender expression. Women’s expressions of vulnerability (BGC 17%/CGC 70%), in turn, manifest in lengthy remarks describing their struggle with self-perception and acceptance of their body. Visual de-constructions of gender and body norms reverse cultural ideologies of the representation of men and women, and instead emphasize equality and humanist thinking. Related to this, a common, repetitive feature in the brand’s visuals is the introduction of the persons featured, indicating whether the depicted person is a professional model or an employee:

Meet Annamarie. She is a web developer and programmer who is originally from Georgia. She cannot live without her ability to post-rationalize. Read more about her on our Facebook page. @annamarie_orsi #AmericanApparel #WCW

We find that repetitive personifications of visual body performances are valued by consumers as de-objectifications of the human body, empowering and transforming the depicted bodies into humans. As one consumer commented on the depiction of American Apparel employee Annamarie:

(I’m guessing this woman is a model) I really love how you guys added the caption about what she likes and what she does. It diminishes objectification. She is not a body, she is not an object, she is a thinking human being. (thumbs-up-emoji)

Complementarily, consumers’ visual performances showcase thoughtful captions (26%). Consumers note honest (54%), “love yourself” (22%) narratives of their “road” to body positivity and their experiences with body shaming, body perceptions, and feelings towards their bodies that do not conform with mainstream ideologies.

In contrast to Marwick (Citation2015, 139), who suggests that “textual description and replies to followers are de-emphasized in favor of images,” our findings suggest that textual discourse also plays a crucial role in counter-conformity discourse. We find extensive consumer discourse in the comment section of brand visuals where consumers respond to posts, exchange opinions, and argue about societal ideologies and norms imposed on the human body. Body positivity discourse prevails by and large, eventually also attacking the brand for its appropriation of the body positivity movement and exploiting consumers’ vulnerabilities regarding their bodies and sexualities. Consumer-generated content, in our case, did not “emulate the visual iconography of mainstream celebrity culture” where microcelebrities re-perform or “re-produce conventional status hierarchies of luxury, celebrity, and popularity” (Marwick Citation2015, 139). In contrast, we find that consumers, in our case, engaged in “visibility labor,” and used the body as central currency in a re-humanizing sense. Re-humanizing is also demonstrated by a more general humanist discourse on equality, ethnic diversity, and freedom of sexuality, linking body-positive narratives to metaphysical beliefs.

Overall, the visual brand assemblage frames a collective rhetoric that repetitively infiltrates mainstream fashion market rhetorics. To illustrate how the assemblage of visual components manifests in brand and consumer-generated content, we extracted fragments of the analyzed images and creatively assembled these parts into an abstract brand () and consumer () visual. The assemblages summarize a visual rhetoric that translates into a collective humanist narrative that aims to aesthetically refocus, naturalize, and re-humanize the mass-marketed “digitally-botoxed” body. This mutually reinforcing visual rhetoric leads to interesting digital marketplace dynamics related to the “materiality of bodies” (Butler Citation1993, 1), which we turn to in the following.

(De-)stabilizing market dynamics on Instagram

Uncovering macro-level market dynamics on Instagram requires not only a thorough analysis of market actors’ visual performances which infiltrate dominant ideological aesthetics, but also an in-depth understanding of the primarily networked character of digital markets. Our case is an example of collective “visibility labor” where two groups of market actors, the brand American Apparel and its consumers, (de-)stabilize aesthetic ideologies by means of diffusing visual content into the network of the mainstream market (). The brand American Apparel “becomes part of a frame” (Bode and Kjeldgaard Citation2017, 289) of a visual rhetoric that consumers may draw on to perform a central project, in our case, to (de-)stabilize aesthetic ideologies of the mainstream fashion market. Body-positive consumers’ visuals coalesce with American Apparel’s communicative performances based on shared values of natural beauty, empowering people, freedom, and diversity. These shared values allow for a collective visual rhetoric that forms an assemblage of components stabilizing the brand-related network on the one hand, and infiltrating the network of the mainstream fashion market on the other.

depicts the network of co-occurring hashtags and correspondent modularity classes which represent distinctive thematic clusters. The mainstream fashion cluster (purple) represents the biggest part of the networked assemblage (26.96%). The most dominant hashtags of this thematic cluster are #fashion (2610 occurrences), #ootd (2089), and #instagood (1288). The mainstream fashion cluster mostly contains “attention capital” hashtags, that is, hashtags such as #dior or #chanel, which fame-seekers use to diffuse their content into trending hashtag feeds in order to collect as many likes as possible (Rokka and Canniford Citation2016). illustrates exteriority relations connected to the core of the network. In other words, depicts which discourse frames the contemporary fashion market as a whole. Closely related to the mainstream fashion market, we find the (green) thematic cluster related to photography (8.65%). Most dominant hashtags in this cluster encompass #vsco (690) and #vscocam (482), referring to the popular photography app of the Visual Supply Company. Discourse on the LGBTQA+ community also relates to the mainstream fashion network, colored in light blue (7.35%). Variations of the hashtag #gay (145), such as #gayboy (126) or #gaymen (81), form this part of the assemblage. Body ideology discourse manifests in the orange cluster (4.16%). Hashtags that thematically relate to #bodypositive (182), #natural (143), and #loveyourself (84) frame the discourse within this part of the assemblage. Discourse on modeling (blue), portrait art (yellow), and festival (turquoise) also relates to the digitized fashion market on Instagram.

We find that the brand and its consumers mutually leverage each other’s content, that is, American Apparel cites and re-performs consumer-generated content by re-posting and tagging the content creator in the image. American Apparel provides hashtags, such as #AAswim, #AAcampus, #AAclassics, #AAdenim, and #AAbasics, which define the context of the visuals. Consumers cite and re-perform these contextual hashtags when they diffuse their content into the brand-related network on Instagram. Consumers further tag the brand in the picture itself. Tagging the brand in consumer-generated content lists the visuals in the “linked images feed” on the brand’s account, leveraging even casual consumers’ content to a potential audience of 2 million brand followers. The brand, in turn, identifies consumer-generated content, and asks consumers for their permission to repost their content on the brand’s Instagram account.

American Apparel thus provides a leveraging platform for consumer-generated content. In other words, the brand’s Instagram account helps produce a megaphone effect for consumer-generated content (McQuarrie, Miller, and Phillips Citation2013). In a similar vein, consumers leverage the brand by repetitively citing and re-performing brand-related cultural scripts in their visuals, which accumulates into mutual, complementary “visibility labor” (Abidin Citation2016, 89). This additive and linked form of “visibility labor” infiltrates the “body-positive” agenda into the mainstream fashion market by producing and circulating visuals that destabilize corporeal standards, norms, ideologies, and public opinion (Wissinger Citation2007). American Apparel rarely collaborates with influencers; instead the brand leverages content of “the girl next door” – the casual consumer with a small number of followers. In turn, these performances create a socio-material assemblage of visual components that stabilize the brand-related network on the one hand, as well as a network of contesting ideologies and aesthetics on the other, creating a “doppelgänger” fashion assemblage (cf. Giesler Citation2012).

Accordingly, we find that consumer content in our sample does not focus solely on the brand itself, but on a shared visual rhetoric: a naturalistic, visual genre which both the American Apparel brand as well its consumers draw upon. This common rhetoric accumulates into a considerable communicative network that infiltrates the visual rhetorics and discursive frames of the mainstream fashion market. This effect visibly extends the network of the mainstream fashion market, as the thematic clusters surrounding the mainstream fashion network show. Overall, the network illustrates how relations of exteriority (DeLanda Citation2006) characterize the digital fashion market on Instagram as a whole. Autonomous exterior parts of the market assemblage, such as the #bodypositive cluster, develop a distinct visual rhetoric and vision regime (Berger Citation1972). Body-positive rhetoric neither imitates mainstream celebrity culture based on cultural capital (cf. Marwick Citation2015), nor collects “attentional capital […] in an attempt to reach followers and likes” (cf. Rokka and Canniford Citation2016, 1803). In contrast, body-positive consumers hijack mainstream hashtags, such as #fashion, and re-assemble them with body-positive hashtags, for example, #bodypositivity. Body-positive trending hashtags encompass #loveyourself, #positivevibes, #honormycurves, #effyourbeautystandards, #natural, #bodyhairdontcare, or #freethenipple amongst others. By attaching such hashtags to visuals, consumers take advantage of Instagram as a fluid, plastic, and interactive network, creating a social imaginary around collaborative cultural discourse (Caliandro and Gandini Citation2017). In other words, consumers use the archival, mediating, and hyperlinking quality of hashtags to join and extend the assemblage, and synthesize autonomous elements with the wider fashion market.

Our co-hashtag analysis shows that, for instance, the hashtag #bodypositive co-occurs with attention capital hashtags of the mainstream fashion network, like #outfitoftheday, #fashion, #picoftheday, #fashionblogger (). We find the same for other body-positive hashtags. Consumers cite and re-perform not only the hashtags related to body positivity, but also mainstream hashtags to intentionally diffuse body-positive content into the mainstream exploration feeds of Instagram such as #fashion (Carah and Shaul Citation2016). As a consequence, these citations accumulate into a networked assemblage of actors, hashtags, visuals, and text, forming an important part of the digitalized fashion market.

Overall, our findings show how micro and meso-level citations performatively change fashion discourse on a macro-level. Postings that combine attention capital hashtags and body-positive hashtags connect the body-positive with the mainstream network. The corresponding effects are twofold. First, consumers and American Apparel frame a collective visual rhetoric that mutually stabilizes the brand-related assemblage. Second, this rhetoric adds exteriority to the whole fashion network in that it undermines the conventional fashion hashtag assemblage with contesting hashtags. These two effects are mutually reinforcing through the visual rhetorics and mediating performances of hashtags on Instagram.

Discussion

Our empirical investigation illustrates how different market actors – the fashion brand American Apparel and its consumers – develop a common visual rhetoric of body performances that seeks to destabilize the current logic of the mainstream fashion market on Instagram. We identify three performative effects of the assemblage of visual components, and demonstrate how visual performances of two groups of market actors coalesce into potentially (de-)stabilizing elements of the mainstream fashion market on Instagram. The theoretical contribution of our study is threefold. First, we contribute to an increased understanding of macro-level consequences of micro and meso-level visual performances in digitized markets. Second, this study offers an illustrative case of the plasticity and fluidity of digital markets, and shows how consumers and brands form networks of hashtagged genres in digital marketplaces. Third, we offer an encompassing methodological approach that respects and integrates visual and textual modalities of digital content with the dynamic performativity of digital market assemblages.

Our performative approach to digital market assemblages illustrates how digital environments bring forth “visibility labor” that effectively infiltrates prevalent visual, textual, and hashtagged rhetorics in digital markets, eventually exerting a destabilizing effect on markets. When non-conventional visual performances accumulate in a market that resembles and links to hegemonic market discourse, linking or hashtagging easily multiplies and appropriates mainstream market logics. Accordingly, we find that brands and consumers do not draw on the institutional logics of the field (Scaraboto and Fischer Citation2013), but rather on the catalytic “logics” of the digital assemblage (cf. Martin and Schouten Citation2014) as they intentionally hijack mainstream hashtags in an attempt to diffuse destabilizing content into the mainstream fashion network. Our study vividly demonstrates that consumers, on a micro-level, decide to enter “markets” and contribute to market change. The digital fashion market on Instagram is continuously contested by various actors, including consumers and other interested stakeholders, who collectively shape and (de-)stabilize established markets (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2007; Nenonen et al. Citation2014), and reorganize the fashion market assemblage – in our case, by developing a shared understanding of body-positive discourse (Lusch and Watts Citation2018).

Adding to the notion of brand publics (Arvidsson and Caliandro Citation2016), which are manifested by interest and mediation rather than interaction, structured by affect rather than discourse, and based on publicity rather than a collective identity, our study suggests that digitized markets also manifest through strong interaction structured by extensive discourse when based on a collective identity or common ideal. In our case, consumers do not simply jump on the bandwagon of #bodypositivity to acquire publicity by collecting likes and followers, or exploit the momentousness of events or venues for accumulating Instafame (Boy and Uitermark Citation2017; Carah and Shaul Citation2016). Our study adds to prior research in that it shows that consumers also join market assemblages to fight for (aesthetic) inclusion in mainstream markets, encourage other consumers, and lend them support. However, as compared to the Fatshonistas’ “Fatosphere” (Scaraboto and Fischer Citation2013), visual brand assemblages are by no means a “closed” community, but rather a collective assemblage of quite different market actors with a shared humanist concern.

Our study further suggests that the visibility labor of two groups of market actors mutually reinforces a visual rhetoric on a micro and meso-level that effectively changes macro-level discourse. This collective visual rhetoric manifests as exteriority that relates and connects to the fashion market assemblage on Instagram. In other words, the repetitive and reflexive visual citations and re-performances of macro-level hashtags result in inclusions of exteriority into the market assemblage as a whole (DeLanda Citation2006; Derrida Citation1988; Nakassis Citation2013). In our case, brand and body-related visual content and hashtags form a collective assemblage around the human body that infiltrates conventional reiterations of body norms in the fashion market. Social media empowers actors to generate content through their repetitive visual performances and seek to challenge “dominant market forms, ideologies, and/or practices” (Nenonen et al. Citation2014, 9). It is in this sense that market actors engage in visibility labor that, in turn, dynamically shapes the market (Lusch and Watts Citation2018). However, in contrast to studies on luxury brand assemblages (Presi, Maehle, and Kleppe Citation2016; Rokka and Canniford Citation2016), the relation between consumers and the brand is not unidirectional, that is, an instrumental relationship where consumers use the brand as attentional capital, but rather a bidirectional relationship of mutually leveraging performances. Increasingly, consumers not only join or exploit marketplace conversations but also perform markets with brands that link to and leverage consumer content in digital marketplaces.

Digital environments also reconfigure the composition of market actors and their interactions. The diffusion of body-positive rhetoric into the network of the mainstream fashion market further illustrates the plasticity of digital markets (Nenonen et al. Citation2014). Market actors – through iterative performances and through referencing these performances in fashion networks – destabilize classic mainstream rhetoric, and add significant clusters of thematic content that is different from mainstream cultural signification. As such, digital markets enable consumers not only to join marketplace conversations on a micro and meso-level, but also to partake in the networked flows of macro-level discourse. This, in turn, emphasizes the dynamic and fluid nature of digitized fashion markets created and altered through interconnected practices. Yet, networked content does not undermine classic rhetoric unless its sheer quantity conquers and fully destabilizes the market assemblage. Markets tend to multiply into overlapping versions as multiple actors create the market through constant interaction and negotiation (Geiger, Kjellberg, and Spencer Citation2012; Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2006). Investigation into timelines of market assemblage plasticity could therefore significantly add to our understanding of the evolution of digitized markets. We also delimited our study to market dynamics that result from exchanges of two groups of market actors, that is, a singular brand and its consumers. Future studies could investigate networks of multiple market actors who seek changes in these markets.

Finally, we offer an encompassing methodological approach with which to investigate market dynamics in digital environments. Following the guidelines of Caliandro and Gandini (Citation2017) and extending prior studies on visual market performativity (Presi, Maehle, and Kleppe Citation2016; Rokka and Canniford Citation2016), our methodological framework includes visual, textual, and networked data in order to fully account for the material and expressive capacities and socio-material dynamics of digital markets. We see considerable potential in supplementing the multi-modal data of socio-material assemblages with performative data of networked visual labor for future investigations into the dynamics of digital markets.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Jonathan D. Schöps is a PhD student at the University of Innsbruck, Faculty of Business and Management. His research revolves around fashion consumption, body performativity, and digital rhetorics, as well as digital market dynamics on Instagram. Methodologically, he focuses on digital and visual research methods.

Stephanie Kogler is a PhD student at the University of Innsbruck, Faculty of Business and Management. Her main research area is the visual, and revolves around how consumer culture is shaped through digital media, and how that impacts branding and market dynamics. Methodologically, she focuses on visual research methods.

Andrea Hemetsberger is Professor of Branding at the University of Innsbruck, Faculty of Business and Management. She is academic director of the Brand Research Laboratory at the University of Innsbruck. Her research revolves around branding and brands as mediators; moments of luxury; brand experiences and self-transformation; consumers’ pursuit of being different; creative consumer online crowds; visual brand rhetorics on Instagram, and charismatic brand leadership.

References

- Abidin, Crystal. 2016. “Visibility Labour. Engaging with Influencers’ Fashion Brands and #OOTD Advertorial Campaigns on Instagram.” Media International Australia 161 (1): 86–100. doi: 10.1177/1329878X16665177

- Alexander, Nicholas. 2009. “Brand Authentication: Creating and Maintaining Brand Auras.” European Journal of Marketing 43 (3/4): 551–562. doi: 10.1108/03090560910935578

- American Apparel. 2017. http://www.americanapparel.com.

- Arvidsson, Adam, and Alessandro Caliandro. 2016. “Brand Public.” Journal of Consumer Research 42 (5): 727–748. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucv053

- Bastian, Mathieu, Sebastien Heymann, and Mathieu Jacomy. 2009. “Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks.” ICWSM 8: 361–362.

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2005. Liquid Life. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Bennet, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Berger, John. 1972. Ways of Seeing. London: BBC and Penguin.

- Bode, Matthias, and Dannie Kjeldgaard. 2017. “Brands Doings in a Performative Perspective – An Analysis of Conceptual Brand Discourses.” In Contemporary Consumer Culture, edited by John F. Sherry and Eileen Fischer, 251–282, London: Routledge.

- Borgerson, Janet, and Daniel Miller. 2016. “Scalable Sociality and ‘How the World Changed Social Media’: A Conversation with Daniel Miller.” Consumption Markets & Culture 19 (6): 520–533. doi: 10.1080/10253866.2015.1120980

- Boy, John D., and Justus Uitermark. 2017. “Reassembling the City Through Instagram.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42 (4): 612–624. doi: 10.1111/tran.12185

- Brandes, Ulrik, Daniel Delling, Marco Gaertler, Robert Görke, Martin Hoefer, Zoran Nikoloski, and Dorothea Wagner. 2008. “On Modularity Clustering.” IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 20 (2): 172–188. doi: 10.1109/TKDE.2007.190689

- Butler, Judith. 1993. Bodies that Matter. New York: Routledge.

- Caliandro, Alessandro, and Alessandro Gandini. 2017. Qualitative Research in Digital Environments. London: Routledge.

- Callon, Michel. 1998. The Laws of the Market. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Carah, Nicolas, and Michelle Shaul. 2016. “Brands and Instagram: Point, Tap, Swipe, Glance.” Mobile Media & Communication 4 (1): 69–84. doi: 10.1177/2050157915598180

- Castells, Manuel. 2009. Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Coleman, Rebecca. 2008. “The Becoming of Bodies.” Feminist Media Studies 8 (2): 163–179. doi: 10.1080/14680770801980547

- Crewe, Louise. 2013. “When Virtual and Material Worlds Collide: Democratic Fashion in the Digital Age.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 45 (4): 760–780. doi: 10.1068/a4546

- DeLanda, Manuel. 2006. A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London: Continuum.

- DeLanda, Manuel. 2016. Assemblage Theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1988. Limited, Inc. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Dillig, Annabel. 2017. “Das Ende des Digitalen Botox.” Süddeutsche Zeitung, July 8. http://sz-magazin.sueddeutsche.de/texte/anzeigen/46200/Das-Ende-des-digitalen-Botox.

- Duckworth, Kendrick, Michael L. Williams II, and Asheton Hogan. 2017. “Humble.” Damn. Aftermath Entertainment, Interscope Records, and Top Dawg Entertainment.

- Featherstone, Mike. 2010. “Body, Image and Affect in Consumer Culture.” Body & Society 16 (1): 193–221. doi: 10.1177/1357034X09354357

- Geiger, Susi, Hans Kjellberg, and Robert Spencer. 2012. “Shaping Exchanges, Building Markets.” Consumption Markets & Culture 15: 2: 133–147. doi: 10.1080/10253866.2012.654955

- Giesler, Markus. 2008. “Conflict and Compromise: Drama in Marketplace Evolution.” Journal of Consumer Research 34 (April): 739–753. doi: 10.1086/522098

- Giesler, Markus. 2012. “How Doppelgänger Brand Images Influence the Market Creation Process: Longitudinal Insights Form the Rise of Botox Cosmetic.” Journal of Marketing 76 (6): 55–68. doi: 10.1509/jm.10.0406

- Gill, Rosalind. 2008. “Empowerment/Sexism: Figuring Female Sexual Agency in Contemporary Advertisement.” Feminism & Psychology 18 (1): 35–60. doi: 10.1177/0959353507084950

- Goffman, Erving. 1979. Gender Advertisements. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Harling, Danielle. 2017. “Kendrick Lamar’s ‘HUMBLE.’ Is 2nd Most Streamed Song of 2017.” HIPHOPDX, October 2. https://hiphopdx.com/news/id.44796/title.kendrick-lamars-humble-is-2nd-most-streamed-song-of-2017#

- Holbrook, Morris B. 2006. “Photo Essays and the Mining of Minutiae in Consumer Research: ‘Bout the Time I got to Phoenix.” In Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Marketing, edited by Russell W. Belk, 476–493. Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

- Kjellberg, Hans, and Claes-Fredrik Helgesson. 2006. “Multiple Versions of Markets: Multiplicity and Performativity in Market Practice.” Industrial Marketing Management 35 (7): 839–855. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2006.05.011

- Kjellberg, Hans, and Claes-Fredrik Helgesson. 2007. “On the Nature of Markets and their Practices.” Marketing Theory 7 (2): 137–162. doi: 10.1177/1470593107076862

- Kotz, Liz. 1992. “The Body You Want: Liz Kotz Interviews Judith Butler.” Artforum 31 (3): 82–89.

- Kozinets, Robert V. 2002. “Can Consumers Escape the Market? Emancipatory Illuminations from Burning Man.” Journal of Consumer Research 29 (June): 20–38. doi: 10.1086/339919

- Lazzarato, Maurizio. 1996. “Immaterial Labour.” In Radical Thought in Italy: A Potential Politics, edited by Paolo Virno and Michael Hardt, 133–148. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Lusch, Robert F., and Jameson K. M. Watts. 2018. “Redefining the Market: A Treatise in Exchange and Shared Understanding.” Marketing Theory 18 (4): 435–449. doi: 10.1177/1470593118777904

- Manovich, Lev. 2017. Instagram and Contemporary Image. http://manovich.net/content/04-projects/145-instagram-and-contemporary-image/instagram_book_manovich.pdf.

- Marres, Noortje, and Carolin Gerlitz. 2016. “Interface Methods: Renegotiating Relations Between Digital Social Research, STS and Sociology.” The Sociological Review 64 (1): 21–46. doi: 10.1111/1467-954X.12314

- Martin, Diane M., and John W. Schouten. 2014. “Consumption-Driven Market Emergence.” Journal of Consumer Research 40 (5): 855–870. doi: 10.1086/673196

- Marwick, Alice E. 2015. “Instafame: Luxury Selfies in the Attention Economy.” Public Culture 27 (1): 137–160. doi: 10.1215/08992363-2798379

- Mason, Katy, Hans Kjellberg, and Johan Hagberg. 2015. “Exploring the Performativity of Marketing: Theories, Practice and Devices.” Journal of Marketing Management 31 (1–2): 1–15. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2014.982932

- McQuarrie, Edward F., Jessica Miller, and Barbara J. Phillips. 2013. “The Megaphone Effect: Taste and Audience in Fashion Blogging.” Journal of Consumer Research 40 (June): 136–158. doi: 10.1086/669042

- Murray, Derek Conrad. 2015. “Notes to the Self: The Visual Culture of Selfies in the Age of Social Media.” Consumption Markets & Culture 18 (6): 490–516. doi: 10.1080/10253866.2015.1052967

- Nakassis, Constantine V. 2012. “Brand, Citationality, Performativity.” American Anthropologist 114 (4): 624–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1433.2012.01511.x

- Nakassis, Constantine V. 2013. “Citation and Citationality.” Signs and Society 1 (1): 51–77. doi: 10.1086/670165

- Nenonen, Suvi, Hans Kjellberg, Jaqueline Pels, Lilliemay Cheung, Sara Lindeman, Cristina Mele, Laszlo Sajtos, and Kaj Storbacka. 2014. “A New Perspective on Market Dynamics: Market Plasticity and the Stability-Fluidity Dialectics.” Marketing Theory 14 (3): 269–289. doi: 10.1177/1470593114534342

- Parmentier, Marie-Agnès, and Eileen Fischer. 2015. “Things Fall Apart: The Dynamics of Brand Audience Dissipation.” Journal of Consumer Research 41 (5): 1228–1251. doi: 10.1086/678907

- Patterson, Maurice, and Richard Elliott. 2002. “Negotiating Masculinities: Advertising and the Inversion of the Male Gaze.” Consumption Markets & Culture 5 (3): 321–349. doi: 10.1080/10253860290031631

- Presi, Caterina, Natalia Maehle, and Ingeborg Astrid Kleppe. 2016. “Brand Selfies: Consumer Experiences and Marketplace Conversations.” European Journal of Marketing 50 (9/10): 1814–1834. doi: 10.1108/EJM-07-2015-0492

- Quinn, Ben. 2017. “Getty Images Orders Photographers Not to Alter Body Shapes.” The Guardian, October 1. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/sep/30/getty-images-ban-photoshop-pictures.

- Rogers, Richard. 2009. Digital Methods. MIT Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hhd3c.

- Rokka, Joonas, and Robin Canniford. 2016. “Heterotopian Selfies: how Social Media Destabilizes Brand Assemblages.” European Journal of Marketing 50 (9/10): 1789–1813. doi: 10.1108/EJM-08-2015-0517

- Rose, Gillian. 2012. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials (3rd ed., reprinted.). London: Sage.

- Salam, Maya. 2017. “Why ‘Radical Body Love’ is Thriving on Instagram.” The New York Times, June 9. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/09/style/body-positive-instagram.html.

- Scaraboto, Daiane, and Eileen Fischer. 2013. “Frustrated Fatshonistas: An Institutional Theory Perspective on Consumer Quests for Greater Choice in Mainstream Markets.” Journal of Consumer Research 39 (April): 1234–1257. doi: 10.1086/668298

- Schneier, Matthew. 2014. “Fashion in the Age of Instagram.” The New York Times, April 9. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/10/fashion/fashion-in-the-age-of-instagram.html?_r=1.

- Schroeder, Jonathan E. 2006. “Critical Visual Analysis.” In Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Marketing, edited by Russell W. Belk, 303–321. Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

- Schroeder, Jonathan E., and Detlev Zwick. 2004. “Mirrors of Masculinity: Representation and Identity in Advertising Images.” Consumption Markets & Culture 7 (1): 21–52. doi: 10.1080/1025386042000212383

- Tiidenberg, Katrin, and Edgar Gómez Cruz. 2015. “Selfies, Image and Re-Making of the Body.” Body & Society 21 (4): 77–102. doi: 10.1177/1357034X15592465

- Wissinger, Elizabeth. 2007. “Modelling a Way of Life: Immaterial and Affective Labour in the Fashion Modelling Industry.” Ephemera 7 (1): 250–269.