ABSTRACT

This paper extends recent theorising on “market violence”, defined here as a type of structural and cultural violence that takes place through an assemblage in the market environment. The Finnish “instant loan” market (similar to payday loans) has been widely criticised, e.g. for excessively high interest rates; in this paper, debtors’ anonymous narratives on the discussion forum Suomi24 are used to analyse the instant loan market as a case of market violence. The study contributes to a deeper understanding of the role of culture and affect in market violence and presents a model of cultural market violence showing how affects (here: hope, shame, despair and sense of urgency) can play a key role in mediating between cultural ideals (here: those of individual responsibility and the “good life”) and concrete business practices, thus enabling market violence.

Introduction

In this article, we extend recent academic discussion on the concept of “market violence” (Fırat Citation2018; Martin et al. Citation2021; McVey, Gurrieri, and Tyler Citation2021; Zwick Citation2018). We define market violence as structural and cultural violence (Galtung Citation1969; Citation1990) taking place as an assemblage within a market setting. Structural violence is brought about by institutional factors that cause unequal life chances and potentially lead to poorer health and well-being for certain marginalised people and groups. We understand culture primarily as the shared values, concepts, images and ideas which enable a people, community, nation or social group to “think and feel about the world” (Hall Citation1997); cultural violence, in turn, refers to ideals, practices, and discourses that legitimate violence or themselves lead to suffering (Galtung Citation1990; see also “symbolic violence” [Bourdieu Citation1991], and “epistemic violence”, [Spivak Citation1988]). Previous research on market violence that looks at culture has mainly focused on “cognitive” factors such as how knowledge, framings or understandings are controlled (Banerjee Citation2018; Martin et al. Citation2021). However, we argue that the cultural side of market violence contains another important facet: the cultural affects involved in market violence. To avoid any confusion with psychological views on affects, we will refer to such affects as “cultural”, and to the process as “cultural-affective”, to highlight that, from our perspective, these are social processes that are intimately connected to the values, ideals and discourses of a cultural context.

We analyse market violence in the context of consumer credit markets, more specifically that of the “instant loan” market in Finland. Consumer indebtedness and consumer credit are central aspects of current financialised societies, and many studies attest to their negative consequences for some consumers (e.g. Davies, Montgomerie, and Wallin Citation2015; Richardson, Elliott, and Roberts Citation2013; Turunen and Hiilamo Citation2014). The business practices and legal frameworks (or lack thereof) that we see as contributing to market violence have been addressed in previous literature on debt, for example, as “predatory lending” (Gallmeyer and Roberts Citation2009; Hill and Kozup Citation2007). These practices include exceptionally high interest rates (hundreds of percentage points) and excessive fees, aggressive or misleading marketing, and targeting vulnerable groups such as elderly or impoverished consumers as well as racial minorities (Hill and Kozup Citation2007; Stegman and Faris Citation2003).

Analysing the consumer credit industry can help shed light on the role of affect in market violence, because it is already known that there is a strong connection between debt and negative emotions, such as a sense of powerlessness, inadequacy, and heightened responsibility for failures (Davies, Montgomerie, and Wallin Citation2015), anxiety and depression (Richardson, Elliott, and Roberts Citation2013; Sweet, Kuzawa, and McDade Citation2018) but also, at least provisionally, optimism (Davey Citation2019) and relief (Anderson et al. Citation2020; Davey Citation2019). Rather than simply focusing on individuals’ sentiments, as has most previous debt research, we extend the perspective advocated by Deville (Citation2014) of affect as a socio-cultural phenomenon and focus on how affective aspects of debt are utilised on a market level, how “certain markets actually depend on, reshape, and operate through processes that might variously be understood as private, intimate, and/or ‘affective’” (470). We argue that credit markets not only bring about affects but are also enabled by affects and make use of them.

At the same time, this study also sheds light on the cultural meanings of debt and credit in the Finnish context. It is relevant to note that Finland has developed from a poor, agrarian periphery into a consumer society relatively recently and quickly, largely in the 1960s and 1970s (Heinonen and Autio Citation2013). Thus, a traditional mentality of scarcity idealising self-sufficiency, parsimony, and avoidance of debt, still partly exists together with newer consumer ethoses (Heinonen and Autio Citation2013; Huttunen and Autio Citation2010; on the normalisation of credit and debt, see also Peñaloza and Barnhart Citation2011). Furthermore, the Nordic countries, including Finland, are characterised by the values of egalitarianism and conformity, but also individualism (Askegaard and Östberg Citation2019), which have a bearing on how debt problems are seen and addressed.

The Finnish “instant loan” market has provided consumers digitally mediated easy-access, non-secured credit since 2005 (Makkonen Citation2014; Määttä Citation2010). In English-speaking countries, similar short-term, high-interest loans are usually referred to as payday loans. We analyse anonymous debtors’ personal narratives, using data from a large, long-standing Finnish discussion forum, Suomi24 (“Finland24”). With the overall purpose of understanding the cultural nature of market violence, we aim to answer the following research questions: (1) How and why does market violence unfold as a cultural process in the Finnish instant loan market? (2) How does affect enable market violence in this context?

This study contributes to a deeper understanding of market violence as a process involving various interconnected structural and cultural aspects of the market environment. More specifically, we show how market violence is mediated by cultural affects, such as shame. We argue that this enables businesses to make use of economic cultural ideals connected to individual responsibility and the “good life” in order to render their products and practices both acceptable and attractive.

In this article, we first construct the theoretical framework of market violence by discussing previous research on market violence specifically, approaches to structural and cultural violence more broadly, as well as the role of affect in consumer debt and market violence. Second, we provide background information on the instant loan market, with some comparison to payday loans, in order to support the starting assumption that market violence is present in this context. Next, we describe the materials and methods, before moving on to our findings regarding the cultural-affective process of market violence, including four key affects. A discussion concludes the paper.

Theoretical framework: market violence

Dimensions of market violence

Recently, marketing scholars taking a social perspective have begun to theorise the phenomenon of violence in and by markets, termed “market violence” (Fırat Citation2018) or “marketplace violence” (Martin et al. Citation2021). So far, much of the literature forms a theoretical discussion on the connection of market violence to capitalism, neoliberalism, and colonialism (Fırat Citation2018; Varman Citation2018; Zwick Citation2018), while some researchers have begun to empirically study violence in specific markets (Martin et al. Citation2021; McVey, Gurrieri, and Tyler Citation2021; Varman and Vijay Citation2018). It has been argued that it is the logic and functioning of the market itself that causes harm to people (Fırat Citation2018). The interests of the market, in general, “have come to rule contemporary lives” (Fırat Citation2018, 1017); whether as workers or as consumers, it is virtually impossible for us to set ourselves outside of markets as we depend on them for access to necessities such as food and shelter (1016). Markets seem to, then, have a certain base-level potential for violence, though some are clearly more violent than others. For example, the tobacco (Martin et al. Citation2021) and pornography (McVey, Gurrieri, and Tyler Citation2021) industries have been found to be characterised by this phenomenon. Relevantly for our context, it has also been previously argued that there are particular ways in which debt is inherently violent (Graeber Citation2014; Lazzarato Citation2012). Furthermore, market violence targets less powerful actors in the market context (whether workers or consumers), particularly groups that are already in some way victimised or marginalised, such as women (McVey, Gurrieri, and Tyler Citation2021), the LGBTQ community (Duncan-Shepherd and Hamilton Citation2022; Martin et al. Citation2021), or people in the Global South (Varman and Vijay Citation2018).

There is still no agreement on what different forms of market violence exist. To help add conceptual clarity to the discussion on market violence, we draw from Galtung’s typology of violence (Citation1969; Citation1990). The first thing to note is that for something to be understood as violence, there must be harm caused to a victim. According to Galtung’s (Citation1969, 168) basic definition, “violence is present when human beings are being influenced so that their actual somatic and mental realisations are below their potential realisations”; meaning that were it not for the negative influence from outside, people would have lived longer, healthier and/or happier lives. Specifically, violence leads to “avoidable insults” to the basic human needs of survival, well-being, identity, and freedom (Galtung Citation1990).

Galtung goes on to state that the usual understanding of violence needs to be extended, arguing notably that we cannot always clearly identify an actor that is responsible for violence; violence can therefore be either personal (performed by a clearly identified subject) or structural (present in social structures) (Galtung Citation1969). Structural violence “shows up as unequal power and consequently as unequal life chances” (Galtung Citation1969, 171); for instance, if people are starving when it is avoidable, then violence is present even if no individual party is clearly culpable. Whereas personal violence is visible as action and usually clearly perceived, structural violence is often invisible because it is inherent in normality. As McVey, Gurrieri, and Tyler (Citation2021) show in their analysis of sexual violence as a form of market violence, violence can also be at once both structural and personal.

Later, Galtung added to his typology the category of cultural violence (Galtung Citation1990), which, similarly to Bourdieu’s (Citation1991) concept of symbolic violence, refers mainly to factors such as religion, ideology, language, art, and science being used to render personal or structural violence acceptable in a specific cultural context. In the context of market violence, the cultural or symbolic dimension has been discussed using several different terms. Similarly to Galtung and Bourdieu, Bouchet (Citation2018) focuses on the “normalisation of violence” by markets, whereby the symbolic value of violence is modified. However, there is also direct harm caused by cultural factors, in addition to the kind that legitimates other forms of violence. For instance, Banerjee (Citation2018) refers to a type of direct harm as “epistemic violence” where “language, law and discourse are used to marginalise and disempower specific groups”. Marginalisation and disempowerment are in and of themselves affronts to the basic human needs of identity and freedom (Galtung Citation1990). Martin et al. (Citation2021), in turn, include in their term “marketplace violence” both the “actions and narratives of powerful market actors that perpetuate inequalities and/or inequities on less powerful market actors” and note that violence can be embedded in cultural discourses.

We conclude, then, that market violence appears primarily as structural or cultural violence in a market setting (although personal violence may be present as well). As argued by Çalışkan and Callon (Citation2010), a market is an arrangement of heterogeneous constituents that deploys, for example, rules and conventions, technical devices, discourses and narratives, knowledge, as well as competencies and skills embodied in living beings. If we apply this perspective, market violence is a complex assemblage that operates through business practices, transactions, legislative frameworks, and also crucially through other cultural dynamics. In this study, we are particularly interested in the connections between such factors and in how they dynamically work together.

So far, much of the literature on market violence has been theoretical (e.g. Fırat Citation2018; Zwick Citation2018). There are scant empirical studies on how and why market violence actually unfolds in specific market contexts; more are needed to advance theoretical development. Those empirical studies that do exist (Martin et al. Citation2021; McVey, Gurrieri, and Tyler Citation2021) have not yet focused on tracing the dynamic assemblages of market violence or drawn attention to the ways that structural and cultural factors are connected. This is the research gap that we aim to remedy as we ask: (RQ1) How and why does market violence unfold as a cultural process in the Finnish instant loan market? This question entails an overview of the assemblage, including how and why consumers come to this market, why they remain on it, and what consequences it holds for them.

The role of affect in debt and market violence

Affect, in socio-cultural studies, is often theorised by drawing on Deleuze and Guattari’s (Citation1987) and Massumi’s (Citation2002) work. In this view, affects are not personal feelings but rather intensities that circulate in assemblages (such as the ones responsible for market violence) and augment or diminish a person’s power to act; affect is the “effectuation of a power of the pack that throws the self into upheaval” (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987, 240). Affect is often described as preceding thought and discourse (Clough and Halley Citation2007; Massumi Citation2002); however, as others have argued, in practice, it becomes difficult to uphold such a division (Wetherell Citation2012; Citation2013). In a world that is inherently social and discursive, affects are entangled in wider practices. Thus, affects are relational and cultural; they constitute subjects rather that originating from or residing within individuals (Bajde and Rojas-Gaviria Citation2021). Furthermore, affects have great power and can be used intentionally and politically (Ahmed Citation2004); as Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987, 356) have put it, affects “transpierce the body like arrows, they are weapons of war”.

Various affective aspects of debt have been discussed from a cultural perspective (e.g. Anderson et al. Citation2020; Davies, Montgomerie, and Wallin Citation2015; Deville Citation2015; Engel and Pedersen Citation2019). For example, Dawney, Kirwan, and Walker (Citation2020) argue that debt involves “entanglements of people, technologies and objects” that produce affective states and that indebtedness involves heightened anxiety and vigilance. Davies, Montgomerie, and Wallin (Citation2015) refer to the lived experience of indebtedness as “financial melancholia”, referring to a Freudian meaning of melancholia: blaming the self for loss instead of accepting it through mourning. When people fail to recognise outside influences on their lives, i.e. the external sources of affect, these become factors that worsen the situation.

The importance of hope has also been discussed in the context of personal debt (Davey Citation2019). One concept that can shed light on how these factors are related to market violence is cruel optimism (Berlant Citation2011; see also Dawney, Kirwan, and Walker Citation2020). This is a cultural-affective dynamic where suffering ensues due to a mismatch between assumed goals and paths towards a good life, as it is conventionally understood, and people’s real-life conditions. In this process, the pursuit of something you desire counter-productively “impedes the aim that brought you to it initially”, often with tragic consequences (Berlant Citation2011, 1). Davey (Citation2019) has noted that although previous literature has pointed out a hope of upward social mobility associated with some forms of debt (mortgages and consumer credit), hope in the context of subprime debtors has little to do with this; rather the optimism is related to avoiding immediate negative outcomes, such as legal enforcement.

Assuming that consumer debt is often connected to credit markets that can be seen as violent, these cultural studies of affects and debt suggest that the detrimental effects of market violence may work partly through internalised cultural affects. This, consequently, makes critical assessment or conscious control particularly difficult for individuals. Market violence theory has, however, so far ignored this potentially important aspect of cultural violence and instead focused on “cognitive” factors such as how knowledge, framings or understandings are controlled (Banerjee Citation2018; Martin et al. Citation2021). Therefore, we set out to answer this second research question: (RQ2) How does affect enable market violence in the Finnish instant loan market?

Context: instant loan and payday loan markets

Since its inception, the many deeply problematic aspects of the Finnish instant loan market have regularly been raised and decried in public discussion, but it has proved difficult to find effective solutions to mitigate their impact. We therefore believe that the Finnish instant loan market is a good example of market violence and that analysing it will help us answer our research questions. As we have argued above, the presence of market violence in instant/payday loan markets entails an influence on consumers by the market, leading to significant negative life outcomes. In order to support this claim and to provide the reader with some context, we will, in this section, summarise some key characteristics of this and similar markets.

Business practices

Instant loans in Finland are quite similar to payday loans in the US, UK and Australia, among other countries. One difference between Finland and many other countries is that, in Finland, the instant loan market sprang up rather late and suddenly in 2005. It has been noted that digital technologies have the ability to bring about significant changes in credit markets (Carlsson et al. Citation2017), and instant loans are an example of this; the instant loan market in Finland was fully digital from the beginning, operating with SMS and the internet, and using automated approval processes (Määttä Citation2010). This allowed for easy application processes as well as quick decisions, which have been seen as the main selling arguments for these loans (Valkama and Muttilainen Citation2008). The companies operating in this market have, thus, never had physical locations and there is no tradition of similar businesses in an offline context. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that Finnish consumers and legislators did not, in the beginning, have a sufficient understanding of the nature of this market. Awareness has increased over the years, however, and online discussion boards such as the one we analyse have arguably played a part in this. This can be seen in the fact that the term “instant loan” is currently viewed quite negatively, and companies in the field have mostly now switched to other terminology (Raijas Citation2019).

Initially, loan periods were short (7–90 days) and the loans were small, €20–300 (Järvelä, Raijas, and Saastamoinen Citation2019; Raijas Citation2019). Therefore, the companies did not need much capital to get started. In 2008, the average annual percentage rate was 554%, although this was often not stated as such, but costs were, rather, given in euros (Valkama and Muttilainen Citation2008). The digital context also allowed the companies to have low fixed costs and for the market to grow quickly. In the autumn of 2005, there were approximately 20 companies in the market, in 2007 there were 50, and in 2012 already 80 (Government bill HE 78/2012). Subsequent changes in legislation have led to a decline in their numbers. In 2018, there were 60 registered and licensed instant loan institutions (Government bill HE 230/ Citation2018).

Legal framework and regulatory response in Finland

Another difference between the instant loan market in Finland and other similar markets for unsecured loans is the regulatory environment. Instant loan providers operate outside the traditional financial sector and the regulations that apply to that sector do not apply to these companies (Järvelä, Raijas, and Saastamoinen Citation2019). They do, however, benefit from the institutional process for debt collection: the law enables any creditor to have recourse to legal proceedings in debt collection. After a court order, creditors may go on to request enforcement from the National Enforcement Authority.

It is perhaps not an exaggeration to say the early years of the market were a “Wild West”, as legislators were caught off guard by the developments. Since then, legislation pertaining to instant loans has been modified several times (Raijas Citation2019). Still, even in recent years, it has been difficult for legislators to keep up, as the digitalised market has developed and companies have adjusted quickly (Järvelä, Raijas, and Saastamoinen Citation2019). A first set of restrictions, which came into effect in 2010, banned night-time lending and established an obligation to state the effective annual percentage rate of charge and to reliably identify the consumer (Government bill HE 64/Citation2009; Government bill HE 24/Citation2010). A turning point occurred in 2013 when parliament set a maximum interest rate (reference rate plus 50 percentage points) for loans smaller than €2,000, banned paid text messages used to request instant loans, and mandated more systematic checking of borrowers’ payment ability (Government bill HE 78/Citation2012). Since 2013, instant loans in their old form have been replaced by much larger credits with longer maturities (Järvelä, Raijas, and Saastamoinen Citation2019; Raijas Citation2019). A regulation from 2018 (CitationGovernment bill HE 230/2018) standardises not only interest rates but also other costs. More recently, maximum interest rates were further temporarily reduced as a reaction to the COVID-19 crisis.

Targeting vulnerable groups

The business logic of instant loan companies appears to call for attracting as many customers as possible, with little regard to repayment ability. The exorbitant fees and interest rates charged to customers, combined with the availability of low-interest money for the companies, undoubtedly help these companies make a profit despite a relatively large proportion of defaulting loans. The companies have, thus, traditionally done little to assess the creditworthiness of their clients (Järvelä, Raijas, and Saastamoinen Citation2019). This bears some similarity to the US market, where lenders usually do not verify a borrower’s credit score (Langley et al. Citation2019). However, in the US, borrowers must at least show that they have a steady income, for example by providing their most recent pay stub (Bhutta, Skiba, and Tobacman Citation2015; Langley et al. Citation2019); this was, at least early on, not the case in Finland (Valkama and Muttilainen Citation2008).

Payday and instant loans seem to respond to a consumer need (Valkama and Muttilainen Citation2008). In the UK context, Rowlingson, Appleyard, and Gardner (Citation2016) have pointed out that people’s reasons for borrowing money are connected to income insecurity and that there is a “fundamental link between payday lending and changes in the labour market, welfare state and financialisation” (538–9). Bhutta, Skiba, and Tobacman (Citation2015) found that, in the US, first-time payday borrowers already seemed to have major financial difficulties. A key point is that these borrowers often do not have other options for obtaining credit (Bhutta, Skiba, and Tobacman Citation2015). Due to this, and the short loan periods, payday loans have been called a subprime substitute for credit cards (Charron-Chénier Citation2018).

In Finland, instant loan companies have also targeted vulnerable groups. Instant loan borrowers are often young people between the ages of 18–29 (Rantala and Tarkkala Citation2010). Because of the digitally mediated character of the market, lenders are not more widely present in poorer areas, as is the case in the US (Gallmeyer and Roberts Citation2009); nevertheless, Valkama and Muttilainen (Citation2008) found that borrowers were more likely to live in poorer regions of Finland. The loans are often used for basic expenses such as food and rent, as well as repaying other debts, while other forms of consumer credit are typically used for larger purchases (Kaartinen and Lähteenmaa Citation2006).

Consequences for consumers

As a result of taking out instant loans, consumers can often get caught in a debt spiral (i.e. paying loans by taking new ones) (Rantala Citation2012). Furthermore, even though the actual number of people who apply for and get instant loans is relatively low, the loans have a high tendency to lead to debt problems, including payment default (Majamaa, Lehtinen, and Rantala Citation2019). The instant loan market has, therefore, played an important part in the near doubling of payment defaults in Finland since 2008 (Asiakastieto Citation2019; Makkonen Citation2014). Credit data registers in Finland are exclusively based on information about payment default, meaning an individual’s credit is good unless they get a “payment default entry”, which amounts to loss of creditworthiness (Makkonen Citation2014). This, in turn, not only limits access to further credit but also, for example, to rental housing or phone contracts.

A number of studies show a relationship between (unsecured) debt and negative health outcomes, particularly depression and suicidal ideation (Fitch et al. Citation2011; Turunen and Hiilamo Citation2014). This might be due to stress as well as internalised feelings of personal responsibility and failure, a type of “neoliberal subjectivity” (Sweet Citation2018; Sweet, DuBois, and Stanley Citation2018). However, causality has been difficult to show; debt may induce symptoms of depression and other health problems, but poor health can also cause debt problems, or the two may both be caused by a third issue, such as unemployment (Richardson, Elliott, and Roberts Citation2013; Turunen and Hiilamo Citation2014). It seems likely that the causality varies case by case. Although the type of debt is not always specified in these studies, we do know that this relationship exists in the case of payday loans and other unsecured debt (Richardson, Elliott, and Roberts Citation2013; Sweet, Kuzawa, and McDade Citation2018).

Materials and methods: personal narratives of instant loans

In this study, we analyse posts related to instant loan use from a very large Finnish discussion forum, Suomi24 (“Finland24”) (Aller Media Oy Citation2014; Lagus et al. Citation2016). Suomi24 is a moderated, topic-centred discussion forum that was founded in 2001, which thereby allowed us access to data spanning a significant part of the instant loan market history (2005–2017). The amount and span of the data thus provide a good overview of how the market has been discussed and experienced by consumers over the years. Specifically, these consumers have first-hand knowledge about the functioning of the market, including its violent features, and their posts therefore help us answer the question of how the process of market violence unfolds. They know how and why they themselves got involved with instant loans and what their affective experience was. This rich data therefore also allows us to analyse qualitatively how and why the market violence process enfolds, as well as how affect is involved in enabling it.

A survey from 2016 suggests that a majority of Suomi24 users are middle-aged, and have used the site for at least ten years; men are over-represented (Harju Citation2018). However, as the site is well-known and covers a wide array of topics, it can be assumed to be used by people from a range of backgrounds. Suomi24 users write under either a registered or a non-registered nickname (Lagus et al. Citation2016); the anonymous nature of the site might also attract younger users to discuss stigmatised topics such as indebtedness. After all, online forums that allow anonymous posting can mitigate the embarrassment caused by socially shared negative understandings of debtors and debt problems (Peltola Citation2013; Rantala Citation2012) thus enabling people to describe their experiences relatively openly, compared to more formal contexts such as interviews. This kind of naturally occurring data from an anonymous discussion forum consequently provides a good way of accessing personal accounts of instant loans.

The texts from Suomi24 are available as a searchable corpus by the Language Bank of Finland (we used the 2017H2 version). In order to locate personal accounts of experiences with instant loans within this four-billion-word corpus, we started by searching for sentences containing any verb in the first-person singular, possibly followed by a maximum of three other words, and, in turn, followed by the Finnish word for or synonym of “instant loan”. The search yielded phrases such as “I took many instant loans.” The resulting 5,090 sections of text containing the search results were downloaded and duplicates removed. At this stage, to yield an amount of material more amenable to qualitative analysis, we took a 10% random sample of the texts separately for each year. Next, we read this sample of texts and found that, although the search had indeed helped locate many promising narratives, some of the search results contained only short mentions of instant loans or were otherwise irrelevant to our study. Therefore, the next step was to conduct a qualitative selection process where we looked up the original texts in their full context and discarded any that did not fulfil our criterion of a detailed personal narrative of instant loan use. We decided to analyse the full discussion threads, as this provided the context needed to interpret the narratives; usually, these discussions also included additional personal stories from other participants. The final data set consists of 97 discussion threads, totalling 689 pages. All texts are in Finnish and examples given in this article have been translated by the present authors.

Some of the posts are quite long, consisting of many paragraphs, while others are more succinct but still contain several sentences and a narrative structure. Certain narratives also develop over several separate posts as the discussion thread progresses. Some posts were written while the process was still ongoing, and some tell the “whole” story in retrospect – from the point when a first loan was taken to, often, the narrator’s decision to swear them off completely. Despite these differences, there are significant similarities between the narratives. Given that we specifically searched for stories describing personal experiences with instant loans, and noting these reoccurring characteristics of the stories, we decided to apply a narrative methodology in order to better understand the type of texts we had collected.

Non-fictional narratives often recount (part of) an individual’s personal history. Narrative is a type of language use that provides resources for the cognitive structuring and semiotic representation of the temporality and perceived causality of events; narratives therefore help people make sense of past events and actions (Coates and Thornborrow Citation2005; Czarniawska Citation2004; Herman Citation2009; Riessman Citation2005). Narratives, as any form of language use, are a form of social action and, therefore, they “do not mirror, they refract the past” (Riessman Citation2005, 6). We are never the sole authors of our stories; in addition to the actors in the (market) context that affect our storyline, there is also a social “repertoire of legitimate stories” (Czarniawska Citation2004, 5) that we draw from as we affectively experience and cognitively interpret, for example, the causality and morality of events and craft our own stories. Thus, narratives and narrative methods provide an entry point to the cultural structuration of individual experience.

In our analysis, we combined thematic and structural approaches to narrative analysis (see Riessman Citation2005). According to Labov and Waletzky’s ([Citation1967] Citation1997) classical model of narratives of personal experience, narratives have a typical structure which includes an orientation (to person, time, place, behavioural situation), a complication or complicating action (event sequence), a resolution (outcome) and possibly a coda (referring back to the present) (see also Labov Citation1997). Identifying the narrative phases, we were able to note which recurring themes, particularly which affects and characteristics of the market, were referred to in each stage. This, in turn, helped us start to understand the how different factors of the assemblage were linked. Labov and Waletzky ([Citation1967] Citation1997) also distinguish two functions of narrative discourse: referential and evaluative. Evaluative sections provide commentary on the events; identifying them helped us gain an understanding of normative cultural meanings related to instant loans.

Findings: cultural-affective process of market violence in the instant loan market

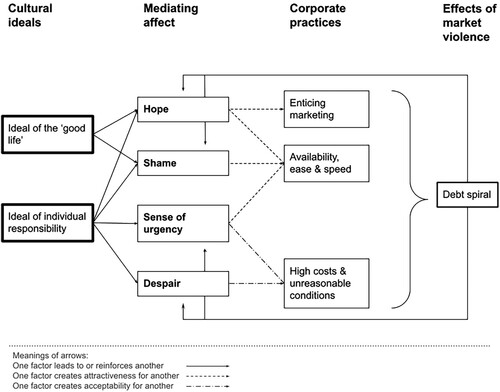

In this section, we present our findings based on the consumer narratives in our data, concerning how market violence unfolds in the instant loan market as a cultural process enabled by affects. Based on our interpretation of the data, we have constructed a model of the cultural-affective process of market violence in the instant loan market, illustrated in . This model captures our central idea that affects can play a key role in mediating between cultural ideals and concrete business practices, thus enabling market violence. As seen on the left in , market violence is in this context rooted in two key cultural ideals of economic life: the ideal of individual responsibility and the ideal of the “good life”. These ideals, mediated by four key affects – sense of urgency, shame, hope, and despair – create both attractiveness and acceptability for various practices of the instant loan companies.

These cultural ideals are powerful, and people therefore hope, and do their best, to comply with them. Instant loan companies are able to further stoke these hopes through enticing marketing; their quickly and easily available products promise access to money that would both enable a good life through consumption, notably easing surprising and difficult life circumstances, and provide a solution for managing financial responsibilities “independently”. Consumers tend to be ashamed if they (anticipate they) are not able to act in accordance with the cultural ideals. Instant loans with their digitally mediated, “anonymous” application process thus also appear attractive because they enable borrowers to save face.

Furthermore, when failure to live up to the ideals is anticipated, this can lead to a sense of urgency, a kind of fearful impatience that promotes rash decisions. Paralysing despair, in turn, can follow when it becomes clear that failure has occurred and no remedy is in sight. These culturally inspired affects make it possible for consumers to accept or disregard terms and conditions that might seem unreasonable while in a different affective state.

Typical business practices (enticing marketing, availability and ease, high costs and unreasonable conditions) together contribute to debt spirals, which can be thought of as an effect of market violence. However, the debt spiral also feeds back into the market violence process; in , the arrows pointing from “debt spiral” back to the affects represent the affective vicious circle inherent to the debt spiral. The debt spiral itself leads to more of the same kind of affects at later stages of the instant loan narratives and those affects, in turn, contribute in their own ways to keeping consumers stuck in the spiral.

The rest of this section is organised around the four key affects – a sense of urgency, shame, hope, and despair – in the debtor narratives.

Sense of urgency

The narratives tend to present an initial reason for taking instant loans by describing a change in life circumstances leading to a problematic situation. These dramatic and unforeseen events bring about an affective sense of urgency that could be described as a kind of panic or a mix of fear and desperate impatience, probably because the crisis threatens the person’s access to what they think are the basics of a good life, a culturally defined decent minimum standard of living (see Aro and Wilska Citation2014; Lehtinen et al. Citation2011). This creates an intense experience that seems to stand in the way of calmly considering options and future consequences of actions and is thus conducive to loan taking. Under these circumstances, instant loans often appear as the only valid option.

In Example 1, indebtedness begins with illness and incapacity to work, and the writer highlights their lack of options stating that they “definitely couldn’t” save any money and “had to resort to” borrowing. Many writers emphasise that they did not take loans for frivolous, hedonistic purposes, but only for necessities such as food (Example 2). Thus, these borrowers draw from a cultural understanding of a responsible person that does not waste money, especially not borrowed money, but does their best at managing life independently. The affective experience of a sense of urgency may or may not, of course, coincide with any “objective” urgency or lack of options. What matters, however, is that the options that might exist are not perceived while in such an affective state.

Example 1

As for me, at 23, I already receive a disability pension and housing allowance for pensioners. Before this, sickness allowance, and with that you definitely couldn’t save or, towards the end, even get much from the store other than tuna and pasta. At that time, I had to resort to instant loans.

Example 2

I have taken instant loans to pay for food, housing (mortgage, electricity, water), insurance, phone bills etc. I sure haven’t wasted anything on any nonsense.

The sense of urgency coupled with such other institutional factors enables concrete business practices by making quick solutions attractive. As seen in Example 3, the digitally mediated instant loan market, in contrast to the welfare system or even traditional banks, is characterised by a quick tempo, and it is thus able to “assist” consumers immediately.

Example 3

There is no bank where you can get a loan in 5 minutes … ! If you have some unforeseen expense (that’s when people usually take instant loans) it is a very easy solution […] The lenders say and it was on the news as well that you can’t get a loan at night. But you can, and it is easy to fool young people when they are out partying and run out of money, then you can take out loans.

Because of this sense of urgency, businesses are able to demand expensive fees, use high interest rates, and dictate conditions that might otherwise dissuade potential customers. In Example 4, the writer again describes a sense of urgency and lack of options.

Example 4

These loan companies know how to strike the right chord, they ruthlessly take advantage of the desperation of the poorest people. I never thought I would support these companies by resorting to instant loans. I thought I would not be so STUPID, I too believed the idea that people fall in this trap because they are stupid. But only one washing machine can change the situation, and so I had to resort to an instant loan for the first time. I tried to think that one €300 loan can’t be the end of the world. But I was wrong.

It is noteworthy that consumers in our data are not by any means the only ones to think that instant loans can become a “trap” for vulnerable people, particularly in circumstances where considering long-term consequences is difficult. This idea has been widely present in public discourse ever since instant loans first became known in Finland. For example Helsingin Sanomat, Finland's largest newspaper, has called for interventions from lawmakers in several editorials such as “Instant loans have become a trap for many” (7.12.2006) and “Instant loans can ruin a young person’s life” (21.6.2011).

Shame

Another central affect that we identified in our data is shame. While there are some examples of shame relating to an inability to meet the ideal of the “good life”, such as not being able to go out with friends, which can then lead to borrowing, the dominant cultural ideal here, too, is individual responsibility – managing one’s money competently and without help from others. Variations of this affect are repeated along the narrative journeys; it is present both as a factor that influences the initial decision to take out an instant loan and one that later prevents debtors from asking for help with uncontrollable debt.

Example 5

I don’t judge anyone for borrowing because I have myself borrowed anything and everything I could get, just because it was easy, whereas if you borrow from a friend and don’t pay, you lose face. Although I had imagined I would pay everything back, but with what income.

Example 6

Living in a small community, I’m too embarrassed to even go ask my own bank.

As the narratives develop, another theme related to shame that occurs again and again is that of losing creditworthiness, that is to say getting a payment default entry in one’s credit data, or, more specifically, the anticipation of that shame. Losing creditworthiness is seen as a life-changing turning point that suddenly marks a person as a failure; it is the epitome of failing to meet the ideal of individual responsibility (note the difference between the Finnish on–off system and more complex credit score systems such as those in the US, e.g. Fourcade and Healy Citation2013 and the UK, e.g. Kirwan Citation2021). Example 7 describes the effects of this “fear-shame” on an individual. Putting “death” in quotation marks, the writer expresses that they are aware it is not actually a matter of life and death but that it feels as if it were. Here, we also see another recurring theme related to shame, that of keeping debt problems a secret from even the closest people.

Example 7

I’m in the exact same situation as you, every bang of the door makes me sweat and I feel like I’m choking, wondering if it’s already the bailiff knocking, that would probably mean “death”. I’m also deathly afraid that my spouse will find out about my foolishness

Nevertheless, in the end, debt collection, loss of creditworthiness and even enforcement sometimes present a way out of the debt spiral. Many write that when they finally lost creditworthiness, it was not as bad as they had expected, or that it was even a relief; at least then they escape the violent market.

Hope

The cultural-affective process of market violence also involves hope. Hope plays different roles in different parts of the narratives. In the initial stage, hope is typically entwined with what we have discussed under sense of urgency; dramatic and unforeseen events evoke both a sense of urgency that invites immediate action and the hope that such action will lead to some amelioration of the situation (enabling maintaining a good life). More rarely, no initial shock is described and the loan taking seems to simply involve a hope of living more comfortably in general (attaining a good life). At the same time, importantly, loan taking is also coupled with a hope that the person’s financial situation will somehow improve in the near future, so that paying the loan back will not be a problem.

At later stages, many narratives describe a thought process by which people hoped to find a way out of the debt spiral by taking more loans. This is also connected to the ideal of individual responsibility, as people refer to the idea that loans must be repaid by any means necessary. Slipping into a debt spiral, people become trapped and live from one payment to the next, one loan to the next. However, as demonstrated by Example 8, the hope that everything will work out is persistent. The feeling of urgency is also evident in the short-term perspective: even next week seems distant and a few days without a payment due is experienced as a relief.

Example 8

I had an instant loan payment of €700 due tomorrow so I paid it back using another instant loan today, because I had to. This is what the spiral is like. And of course, like everyone, I have also so-called normal bills all the time. But now I don’t have any bill due before Friday, so I can breathe for a week […] it’s true they are a hell of a bad option but this way I get a little time to think about solutions (and to get my bigger June wages, and maybe tax refunds) but mostly I’m thinking about other options.

At later stages of the narratives, when some writers have managed to escape the debt spiral, another type of hope is to remain debt-free. However, the writers now know through experience that hoping is not enough – in certain circumstances they are defenceless against the market – and therefore they take concrete defensive measures in advance.

Example 9

I have set a credit ban for myself with every instant loan place I have borrowed from!!! And I have stuck by my decision. New companies appear all the time, but I don’t even look at the ads. But still, even though I have the credit ban in place, those companies keep sending messages by SMS and email, ‘apply for a loan’ etc.!!! Are those bans useful at all, if they keep sending messages all the time!!!??? But I don’t intend to give in again, I have been so close to ruining my life so many times that I’m not going to do that anymore!!!!

Despair

The hope that everything will work out is, however, often to no avail, and sometimes the hoped-for changes even materialise without bringing resolution. This, as well as being trapped in the debt spiral in general, has, of course, much to do with the burdensome expense of the loans. Finding the funds to pay back the debt simply becomes less and less likely, as interest and costs start to accumulate, leading to feelings of despair. For this reason, the writer in Example 11 finds it necessary to explicitly warn other consumers.

Example 10

I warn everyone not to take instant loans from this company. Their annual rate can be up to 220%, meaning that you will never get rid of your debt. On a €2,000 loan, I have so far had to pay back €2,300 over a 4-month period, while the principal has decreased by €140.

The debtors also write for example about crying, not getting sleep, appetite loss and even suicidal thoughts. These seem to be forms of suffering caused by market violence, but at the same time despair can also work to maintain the spiral. In Example 11, the reference to being “paralyzed” points to the ability of affect to either move or stop us. The sense of urgency and unrealistic hope tend to move people to act rashly, and shame can lead to inaction when people fail to consider certain actions as valid options. Despair, meanwhile, can paralyse those in debt, causing them to give up any attempts to resolve the situation.

Example 11

There is nowhere I can get help, all options have been used. I’m anxious, depressed, and so paralysed because of these things that I can’t even manage normal everyday routines, I have lost my will to live and given up hope.

In Finland, institutional help for people in excessive debt is available mainly from financial and debt counselling organised by municipalities and from the Guarantee Foundation, a non-governmental organisation that provides restructuring loans for over-indebted individuals. These options are widely discussed in our material, with writers usually, however, pointing out difficulties accessing them because wait times for debt counselling are long and conditions for the Guarantee Foundation guarantees are strict; this can be another cause for despair. Although these options do, of course, still help resolve the situation for many people, what stands out to us particularly is how often escape from the debt spiral involves help from friends or relatives, as in Example 12. This is interesting in light of what has been discussed above concerning individual responsibility, shame and efforts to hide debt from family members.

Example 12

Then one night my mom happened to call me as I was lying on the sofa crying, so I just started sobbing on the phone and telling her how bad things were. Mom was completely shocked about it but said that everything would be ok. I couldn’t manage my instant loans and other debts at all anymore, so my parents guaranteed a bank loan and now I’m repaying that for a couple of years.

Discussion

In this paper, we have analysed Finnish consumers’ narratives of their experiences with instant loans to understand how and why market violence unfolds as a cultural process in the Finnish instant loan market, as well as to shed light on how affects enable market violence. In so doing, we extend a cultural understanding of market violence, which we see as a combination of structural and cultural violence taking place as a dynamic assemblage within a market setting. We bring to market violence theory a new perspective focused on the importance of affects, as opposed to “cognitive” cultural factors such as knowledge, framings or understandings (see Banerjee Citation2018; Martin et al. Citation2021). More specifically, we have shown that affects – in this case a sense of urgency, shame, hope, and despair – can mediate between cultural ideals and concrete business practices, thus enabling market violence, and we have created a model to illustrate the various connections between these factors. In addition, we extend earlier research focusing how cultural meanings drive usage of credit and debt (e.g. Bajde and Rojas-Gaviria Citation2021; Peñaloza and Barnhart Citation2011).

The findings of this study indicate that two key cultural ideals, individual responsibility and a vision of the “good life”, together with affects stemming from them, enable the instant loan market and the adverse effects it has on consumers. The ideal of individual responsibility is connected to the traditional values of self-sufficiency, parsimony, and avoidance of debt (Heinonen and Autio Citation2013; Huttunen and Autio Citation2010), as well as shame when one fails to manage one’s finances responsibly and independently. In our data, one key aspect related to shame was, in fact, the extreme reluctance of the debtors to turn to their family in times of economic hardship. This is also connected to assumptions related to the welfare state and so called “statist individualism” (Berggren and Trägårdh Citation2015; Ulver Citation2019) where people are more comfortable relying on the state than on other people. The debtors in our data often implied that they had primarily expected the state to help them, but when it had not, they felt that they “had to” turn to the instant loan market instead – asking loved ones for help was too shameful to be seen as a valid option.

Of course, other cultures also have individualistic features, for example, the desire to be independent from family and friends was found in the cultural context of white middle class Americans and the meanings they connect to credit and debt (Peñaloza and Barnhart Citation2011). However, in Peñaloza and Barnhart’s data such independence was not commonly prioritised by individuals with debt problems in particular; instead, hopes for ever-higher standards of living – or the ideal of the good life – were more apparent. This is connected to a normalisation of credit and debt as an enabler of consumption (and the aspects of a good life it makes possible) in the American consumer society (Peñaloza and Barnhart Citation2011). Finland is also experiencing a gradual shift from a mentality of scarcity to a mentality of abundance, accompanied by decreasing moralising regarding both consumption and debt (Heinonen and Autio Citation2013), and thus there are conflicting cultural tendencies that exist simultaneously. In addition, related to the Nordic welfare state and its egalitarian values (see also Askegaard and Östberg Citation2019), Finns tend to think that a good life requires a certain minimum standard of living which, in theory at least, everyone is entitled to. Elements of this constantly evolving minimum standard are culturally defined as “necessary consumption” (see Aro and Wilska Citation2014; Lehtinen et al. Citation2011).

When people are not able to access these things that are seen as essential in the cultural context, our findings indicate that they experience a sense of urgency which is one reason why they end up taking instant loans. The term “instant loan” is fitting; the market responds to a sense of urgency by providing a quick and easy solution. This is, therefore, a type of product that takes advantage of people who are, for one reason or another, so focused on the immediate future that a longer-term future or the past (such as previous experiences with instant loans) become blurred (on the time perception of instant loan borrowers, see also Autio et al. Citation2009, 412). The speed of the process, in part, may mean that people fail to understand fully what they are committing to. When one is affectively highly tied to the immediate future, any longer-term future appears further away, and even exorbitant interest rates may seem acceptable.

The sense of urgency is, then, connected to the hope that, on the one hand, a small loan can alleviate a difficult situation and make life better and, on the other hand, finances can improve between now and the time when loans are due, enabling repayment. In our data, hope is therefore often what Berlant (Citation2011) calls “cruel optimism”: there is a certain kind of “good life” that people believe should belong to them, but it never seems to materialise, and simply entertaining this hope actually results in the debtors being worse of, while the lenders profit, of course. Investigating the online microloan market, Bajde and Rojas-Gaviria (Citation2021) identify a similar dynamic where a hope for a brighter future and optimistic narratives are utilised by market actors to fuel a credit market; however, the debtors might not actually gain access to a significantly better life, and may even end up in worsening debt spirals.

In our material, despair often comes to play with the experience of entrapment in such a debt spiral. A tendency to cause debt spirals has also been noted in studies on payday loans (e.g. Anderson et al. Citation2020; Langley et al. Citation2019; Szilagyiova Citation2015); in fact, this has been called a defining feature of these markets (Stegman and Faris Citation2003). Deville (Citation2015) has also argued that consumer credit, in general, produces sticky attachments – it is a “financial instrument that is designed with attachment in mind.” Like us, Davies, Montgomerie, and Wallin (Citation2015) note that the origin of problem debts tends to be an external shock, followed by a spiral out of control accompanied by anxiety, depression and guilt.

Furthermore, the narratives in our material often involved blaming oneself: the self and others should learn from these stories to act more intelligently and responsibly. Self-blame and learning lessons have also been discussed by Davies, Montgomerie, and Wallin (Citation2015) as well as Peñaloza and Barnhart (Citation2011). It seems, then, that the cultural-affective processes of market violence on credit markets operate partly through consumers themselves, who have internalised cultural ideals. Therefore, the victims of market violence ostensibly seem responsible for their own problems, even to themselves. This is obviously connected to the ideal of individual responsibility that we have highlighted throughout the analysis, and an individualistic, “neoliberal subjectivity” (see also Sweet Citation2018; Sweet, DuBois, and Stanley Citation2018) constituted by market-mediated “affective encounters” (Bajde and Rojas-Gaviria Citation2021). The similarities we have noted with studies from other contexts might thus stem from a combination of shared “Western” and “neoliberal” cultural features as well as shared characteristics of the specific credit markets and of capitalism itself.

Reflecting on our findings and previous research on market violence, it seems that culture has at least two key roles to play in market violence: in cases of market violence that predominantly involve structural violence and domination, including physical forms of violence (“instrumental violence”, as Banerjee Citation2018 puts it), culture mainly works to legitimate or normalise violence (Bouchet Citation2018), for example, through discursive processes that dehumanise victims (Varman and Vijay Citation2018). At least so far, this first type appears to be found mostly in the Global South (Banerjee Citation2008; Citation2018; Varman and Vijay Citation2018). Culture plays another role when the market violence itself is primarily cultural; the violence is thus “embedded in cultural discourses” (Martin et al. Citation2021) and often involves discrimination and psychological suffering more than direct physical injury. This second role of culture has so far been discussed in markets of the Global North (Martin et al. Citation2021; McVey, Gurrieri, and Tyler Citation2021). Our study extends this research by demonstrating how market violence can be enabled by cultural ideals and affects that are internalised by consumers. We might hypothesise that a similar process involving ideals and affects is probably present in other cases where normative ideals (of personal responsibility, for example) are central, such as weight loss and diet.

Overall, market violence theory helps draw attention to and critique the suffering caused by markets – as opposed to the neoliberal view where the “normal functioning” of markets is prioritised and individuals are blamed for problems. From the market violence perspective, the latter is not only problematic victim-blaming but also politically inefficient as it focuses on fixing the consumer (e.g. through education) instead of the market in its wider cultural and legislative context. From the perspective of consumer debt, market violence theory provides a new approach to contrast with the view that over-indebtedness is due to consumers’ shortcomings – a view also reflected in academic discussions about inadequate financial literacy (e.g. Bolton, Bloom, and Cohen Citation2011) and consumer vulnerability (Baker, Gentry, and Rittenburg Citation2005; Shultz and Holbrook Citation2009). Our study has extended market violence theory to include the importance of cultural ideals and affects connected to them, and thereby it also has an implication on the role of consumer education; information may not help in dealing with intense affects and it is, then, a necessary but wholly insufficient condition of alleviating market violence. Therefore, the complex assemblages of market violence, including the cultural-affective processes involved, must also be considered.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ella Lillqvist

Ella Lillqvist, Postdoctoral Researcher at the Centre for Consumer Society Research, University of Helsinki, and at the University of Vaasa, School of Marketing and Communication. Her current research interests concern cultural studies of the economy and include economic discourses and imaginaries, investment cultures and consumer debt.

Päivi Timonen

Päivi Timonen, Research Director at the Centre for Consumer Society Research, University of Helsinki. Her current research interests relate to politics of consumption, such as democracy of innovations, market violence and consumer-generated data.

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Aller Media Oy. 2014. Suomi24 corpus [text corpus]. Edited by the Language Bank of Finland.

- Anderson, Ben, Paul Langley, James Ash, and Rachel Gordon. 2020. “Affective Life and Cultural Economy: Payday Loans and the Everyday Space-Times of Credit-Debt in the UK.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45: 420–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12355.

- Aro, Riikka, and Terhi-Anna Wilska. 2014. “Standard of Living, Consumption Norms, and Perceived Necessities.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 34 (9/10): 710–728. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-06-2013-0064.

- Asiakastieto. 2019. “Kuluttajien maksuhäiriöissä vaikea vuosi: tuomiomerkinnät lisääntyivät ja summat kasvoivat (Payment default statistics 2018, Finland).” https://www.asiakastieto.fi/web/fi/asiakastieto-media/uutiset/2019/01/kuluttajien-maksuhairioissa-vaikea-vuosi-tuomiomerkinnat-lisaantyivat-ja-summat-kasvoivat.html.

- Askegaard, Søren, and Jacob Östberg. 2019. “Introduction: The Institution and the Imaginary in a Nordic Light.” In Nordic Consumer Culture: State, Market and Consumers, edited by Søren Askegaard, and Jacob Östberg, 1–21. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Autio, Minna, Terhi-Anna Wilska, Risto Kaartinen, and Jaana Lähteenmaa. 2009. “The Use of Small Instant Loans among Young Adults – a Gateway to a Consumer Insolvency?” International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (4): 407–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2009.00789.x.

- Bajde, Domen, and Pilar Rojas-Gaviria. 2021. “Creating Responsible Subjects: The Role of Mediated Affective Encounters.” Journal of Consumer Research 48 (3): 492–512. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucab019.

- Baker, Stacey Menzel, James W. Gentry, and Terri L. Rittenburg. 2005. “Building Understanding of the Domain of Consumer Vulnerability.” Journal of Macromarketing 25 (2): 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146705280622.

- Banerjee, Subhabrata Bobby. 2008. “Necrocapitalism.” Organization Studies 29 (12): 1541–1563. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607096386.

- Banerjee, Subhabrata Bobby. 2018. “Markets and Violence.” Journal of Marketing Management 34 (11–12): 1023–1031. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2018.1468611.

- Berggren, Henrik, and Lars Trägårdh. 2015. Är Svensken Människa? Gemenskap Och Oberoende i Det Moderna Sverige. Stockholm: Norstedts.

- Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bhutta, Neil, Paige Marta Skiba, and Jeremy Tobacman. 2015. “Payday Loan Choices and Consequences.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 47 (2-3): 223–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmcb.12175.

- Bolton, Lisa E., Paul N. Bloom, and Joel B. Cohen. 2011. “Using Loan Plus Lender Literacy Information to Combat One-Sided Marketing of Debt Consolidation Loans.” Journal of Marketing Research 48 (SPL): S51–S59. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.48.SPL.S51.

- Bouchet, Dominique. 2018. “Marketing, Violence and Social Cohesion: First Steps to a Conceptual Approach to the Understanding of the Normalising Role of Marketing.” Journal of Marketing Management 34 (11–12): 1048–1062. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2018.1521114.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Edited by John B. Thompson. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Brookes, Gavin, and Kevin Harvey. 2017. “Just Plain Wronga? A Multimodal Critical Analysis of Online Payday Loan Discourse.” Critical Discourse Studies 14 (2): 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2016.1250651.

- Çalışkan, Koray, and Michel Callon. 2010. “Economization, Part 2: A Research Programme for the Study of Markets.” Economy and Society 39 (1): 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140903424519.

- Carlsson, Hanna, Stefan Larsson, Lupita Svensson, and Fredrik Åström. 2017. “Consumer Credit Behavior in the Digital Context: A Bibliometric Analysis and Literature Review.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 28 (1): 76–94. https://doi.org/10.1891/1052-3073.28.1.76.

- Charron-Chénier, Raphaël. 2018. “Payday Loans and Household Spending: How Access to Payday Lending Shapes the Racial Consumption Gap.” Social Science Research 76: 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.08.004.

- Clough, P. T., and J. Halley, eds. 2007. The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Coates, Jennifer, and Joanna Thornborrow. 2005. “The Sociolinguistics of Narrative: Identity, Performance, Culture.” In The Sociolinguistics of Narrative, edited by Jennifer Coates, and Joanna Thornborrow, 1–16. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Czarniawska, Barbara. 2004. Narratives in Social Science Research. London: Sage.

- Davey, Ryan. 2019. “Mise en scène: The Make-Believe Space of Over-Indebted Optimism.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 98: 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.10.026.

- Davies, Will, Johnna Montgomerie, and Sara Wallin. 2015. Financial Melancholia: Mental Health and Indebtedness. London: Political Economy Research Centre.

- Dawney, Leila, Samuel Kirwan, and Rosie Walker. 2020. “The Intimate Spaces of Debt: Love, Freedom and Entanglement in Indebted Lives.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.11.006.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Deville, Joe. 2014. “Consumer Credit Default and Collections: The Shifting Ontologies of Market Attachment.” Consumption Markets & Culture 17 (5): 468–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2013.849593.

- Deville, Joe. 2015. Lived Economies of Default: Consumer Credit, Debt Collection and the Capture of Affect. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Duncan-Shepherd, Sophie, and Kathy Hamilton. 2022. ““Generally, I Live a Lie”: Transgender Consumer Experiences and Responses to Symbolic Violence.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 56: 1597–1616. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12482.

- Engel, Susan, and David Pedersen. 2019. “Microfinance as Poverty-Shame Debt.” Emotions and Society 1 (2): 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1332/263168919X15653391247919.

- Fitch, Chris, Sarah Hamilton, Paul Bassett, and Ryan Davey. 2011. “The Relationship Between Personal Debt and Mental Health: A Systematic Review.” Mental Health Review Journal 16 (4): 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/13619321111202313.

- Fırat, A. Fuat. 2018. “Violence in/by the Market.” Journal of Marketing Management 34 (11–12): 1015–1022. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2018.1432190.

- Flores-Pajot, Marie-Claire, Sara Atif, Magali Dufour, Natacha Brunelle, Shawn R. Currie, David C. Hodgins, Louise Nadeau, and Matthew M. Young. 2021. “Gambling Self-Control Strategies: A Qualitative Analysis.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 586. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020586.

- Fourcade, Marion, and Kieran Healy. 2013. “Classification Situations: Life-Chances in the Neoliberal Era.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 38 (8): 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2013.11.002.

- Gallmeyer, Alice, and Wade T. Roberts. 2009. “Payday Lenders and Economically Distressed Communities: A Spatial Analysis of Financial Predation.” The Social Science Journal 46 (3): 521–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2009.02.008.

- Galtung, Johan. 1969. “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research.” Journal of Peace Research 6 (3): 167–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234336900600301.

- Galtung, Johan. 1990. “Cultural Violence.” Journal of Peace Research 27 (3): 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343390027003005.

- Government bill HE 230/2018. 2018. “Hallituksen esitys eduskunnalle kuluttajaluottosopimuksia ja eräitä muita kuluttajasopimuksia koskevien säännösten muuttamisesta [Government's proposal to Parliament to amend the provisions concerning consumer credit agreements and certain other consumer agreements].” https://www.finlex.fi/fi/esitykset/he/2018/20180230.

- Government bill HE 24/2010. 2010. “Hallituksen esitys Eduskunnalle laeiksi kuluttajansuojalain muuttamisesta ja eräiden luotonantajien rekisteröinnistä sekä eräiksi niihin liittyviksi laeiksi (Government's proposal to Parliament for laws amending the Consumer Protection Act and the registration of certain creditors, as well as certain related laws).” https://finlex.fi/fi/esitykset/he/2010/20100024.

- Government bill HE 64/2009. 2009. “Hallituksen esitys Eduskunnalle laeiksi kuluttajansuojalain 7 luvun, rikoslain 36 luvun 6 §:n ja korkolain 4 §:n muuttamisesta (Government's proposal to Parliament to amend Chapter 7 of the Consumer Protection Act, Chapter 36, section 6 of the Crimnal Code and Section 4 of the Interest Act).” https://www.finlex.fi/fi/esitykset/he/2009/20090064.

- Government bill HE 78/2012. 2012. “Hallituksen esitys eduskunnalle laeiksi kuluttajansuojalain 7 luvun, eräiden luotonantajien rekisteröinnistä annetun lain sekä korkolain 2 §:n muuttamisesta (Government's proposal to Parliament to amend Chapter 7 of the Consumer Protection Act, the Act on the Registration of Certain Lenders and Section 2 of the Interest Act).” https://www.finlex.fi/fi/esitykset/he/2012/20120078.

- Graeber, David. 2014. Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Brooklyn: Melville House.

- Hall, Stuart. 1997. “Introduction.” In Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, edited by Stuart Hall, 1–11. London: Sage.

- Harju, Auli. 2018. “Suomi24-keskustelut kohtaamisten ja törmäysten tilana.” Media & viestintä 41 (1): 51–74. https://doi.org/10.23983/mv.69952.

- Heinonen, Visa, and Minna Autio. 2013. “The Finnish Consumer Mentality and Ethos: At the Intersection Between East and West.” In Finnish Consumption: An Emerging Consumer Society Between East and West, edited by Visa Heinonen, and Matti Peltonen, 42–85. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

- Herman, David. 2009. Basic Elements of Narrative. Hoboken, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Hill, Ronald Paul, and John C. Kozup. 2007. “Consumer Experiences with Predatory Lending Practices.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 41 (1): 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2006.00067.x.

- Huttunen, Kaisa, and Minna Autio. 2010. “Consumer Ethoses in Finnish Consumer Life Stories – Agrarianism, Economism and Green Consumerism.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 34 (2): 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2009.00835.x.

- Järvelä, Katja, Anu Raijas, and Mika Saastamoinen. 2019. “Pikavippiongelmien laatu ja laajuus (The Nature and Scope of Problems with Instant Loans).” Finnish Competition and Consumer Authority.

- Kaartinen, Risto, and Jaana Lähteenmaa. 2006. Miten ja mihin nuoret käyttävät pikavippejä ja muita kulutusluottoja? [For What Purposes and How Do Young People Use Instant Loans and Consumer Credit?]. Helsinki: Ministry of Trade and Industry. Finland.

- Kirwan, Samuel. 2021. “Between a Knock at the Door and a Knock to Your Score: Re-Thinking ‘Governing Through Debt’ Through the Hopeful ‘Imaginaries’ of UK Debtors.” Journal of Cultural Economy 14 (2): 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2020.1818602.

- Krishnamurthy, Parthasarathy, and Sonja Prokopec. 2010. “Resisting That Triple-Chocolate Cake: Mental Budgets and Self-Control.” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (1): 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1086/649650.

- Labov, William. 1997. “Oral Versions of Personal Experience.” Journal of Narrative and Life History 7 (1–4): 395–415. https://doi.org/10.1075/jnlh.7.49som.

- Labov, William, and Joshua Waletzky. (1967) 1997. “Narrative Analysis: Oral versions of personal experience.” Journal of Narrative and Life History 7: 3–38. https://doi.org/10.1075/jnlh.7.02nar.

- Lagus, Krista, Mika Pantzar, Minna Ruckenstein, and Marjoriikka Ylisiurua. 2016. SUOMI24: Muodonantoa aineistolle [SUOMI24: Describing a Data set], Publications of the Faculty of Social Sciences 10. Helsinki: Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Helsinki.

- Langley, Paul, Ben Anderson, James Ash, and Rachel Gordon. 2019. “Indebted Life and Money Culture: Payday Lending in the United Kingdom.” Economy and Society 48 (1): 30–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2018.1554371.

- Lazzarato, Maurizio. 2012. The Making of the Indebted Man: An Essay on the Neoliberal Condition, Semiotext(e) Intervention Series. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

- Lehtinen, Anna-Riitta, Johanna Varjonen, Anu Raijas, and Kristiina Aalto. 2011. “What Is the Cost of Living? Reference Budgets for a Decent Minimum Standard of Living in Finland.” Working Papers 132. Helsinki: National Consumer Research Centre.

- Määttä, Kalle. 2010. “Pikaluottojen sääntely oikeustaloustieteellisestä näkökulmasta.” [Regulation of Instant Loans from the Perspective of law and Economics]. Lakimies 108 (3): 265–279.

- Majamaa, Karoliina, Anna-Riitta Lehtinen, and Kati Rantala. 2019. “Debt Judgments as a Reflection of Consumption-Related Debt Problems.” Journal of Consumer Policy 42: 223–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-018-9402-3.

- Makkonen, Antti. 2014. “Instant Loans: Problems and Regulations in Finland.” Juridica International 22: 96–119. https://doi.org/10.12697/JI.2014.22.09.

- Martin, Diane M., Shelagh Ferguson, Janet Hoek, and Catherine Hinder. 2021. “Gender Violence: Marketplace Violence and Symbolic Violence in Social Movements.” Journal of Marketing Management 37 (1–2): 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2020.1854330.

- Massumi, Brian. 2002. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham: Duke University Press.

- McVey, Laura, Lauren Gurrieri, and Meagan Tyler. 2021. “The Structural Oppression of Women by Markets: The Continuum of Sexual Violence and the Online Pornography Market.” Journal of Marketing Management 37 (1–2): 40–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2020.1798714.

- Nureeva, Liliya, Karen Brunsø, and Liisa Lähteenmäki. 2016. “Exploring Self-Regulatory Strategies for Eating Behaviour in Danish Adolescents.” Young Consumers 17 (2): 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-10-2015-00565.

- Peltola, Sari-Maarit. 2013. “Holtitonta kulutusta vai selviytymistaistelua?” In Kulutuksen kuvat, edited by Minna Lammi, Johanna Mäkelä, and Veera Mustonen, 84–103. Helsinki: Kuluttajatutkimuskeskus.

- Peñaloza, Lisa, and Michelle Barnhart. 2011. “Living U.S. Capitalism: The Normalization of Credit/Debt.” Journal of Consumer Research 38 (4): 743–762. https://doi.org/10.1086/660116.

- Raijas, Anu. 2019. “Pikavippimarkkinoiden kehitys ja sääntely Suomessa.” Kansantaloudellinen aikakauskirja 115 (4): 620–637.

- Rantala, Kati. 2012. Vippikierteen muotokuva. OPTL:n verkkokatsauksia 24/2012: 1-27.

- Rantala, Kati, and Heta Tarkkala. 2010. “Luotosta luottoon: velkaongelmien dynamiikka ja uudet riskiryhmät yhteiskunnan markkinalogiikan peilinä.” [Debt Problems and Their Management as Mirrors of the Market Logic in Society]. Yhteiskuntapolitiikka 75 (1): 19–33.

- Richardson, Thomas, Peter Elliott, and Ronald Roberts. 2013. “The Relationship Between Personal Unsecured Debt and Mental and Physical Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Clinical Psychology Review 33 (8): 1148–1162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.009.

- Riessman, Catherine Kohler. 2005. “Narrative Analysis.” In Narrative, Memory & Everyday Life, edited by Nancy Kelly, Christine Horrocks, Kate Milnes, Brian Roberts, and David Robinson, 1–7. Huddersfield: University of Huddersfield.

- Rowlingson, Karen, Lindsey Appleyard, and Jodi Gardner. 2016. “Payday Lending in the UK: The Regul(Aris)Ation of a Necessary Evil?” Journal of Social Policy 45 (3): 527–543. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279416000015.

- Shultz, Clifford J., and Morris B. Holbrook. 2009. “The Paradoxical Relationships Between Marketing and Vulnerability.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 28 (1): 124–127. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.28.1.124.

- Spivak, G. C. 1988. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by N. Carry, and L. Grossberg, 271–313. Urbana-Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Stegman, Michael A., and Robert Faris. 2003. “Payday Lending: A Business Model That Encourages Chronic Borrowing.” Economic Development Quarterly 17 (1): 8–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891242402239196.

- Sweet, Elizabeth. 2018. ““Like you Failed at Life”: Debt, Health and Neoliberal Subjectivity.” Social Science & Medicine 212: 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.017.

- Sweet, Elizabeth, Zachary DuBois, and Flavia Stanley. 2018. “Embodied Neoliberalism: Epidemiology and the Lived Experience of Consumer Debt.” International Journal of Health Services 48 (3): 495–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731418776580.

- Sweet, Elizabeth, Christopher W. Kuzawa, and Thomas W. McDade. 2018. “Short-term Lending: Payday Loans as Risk Factors for Anxiety, Inflammation and Poor Health.” SSM - Population Health 5: 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.05.009.

- Szilagyiova, Silvia. 2015. “The Effect of Payday Loans on Financial Distress in the UK.” Procedia Economics and Finance 30: 842–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01334-9.

- Turunen, Elina, and Heikki Hiilamo. 2014. “Health Effects of Indebtedness: A Systematic Review.” BMC Public Health 14 (1): 489. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-489.

- Ulver, Sofia. 2019. “Market Wonderland: An Essay About a Statist Individualist Consumer Culture.” In Nordic Consumer Culture: State, Market and Consumers, edited by Søren Askegaard, and Jacob Östberg, 49–70. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.