ABSTRACT

AI-enabled smart objects have rapidly become everyday commodities and do not only change the ways in which we consume but also the ethics that guide our consumption. Emerging sociomaterial perspectives viewing consumers and smart objects as assemblages have been employed to study relational aspects of consumption, as well as consumer experience in the digital reality. This article argues that consumer ethics could and should be viewed as emergent properties of such consumption assemblages. Drawing on exemplars ranging from wearables to autonomous robots, this article illustrates the potential of this perspective and outlines fruitful directions for future research on questions of consumer agency and self-determination in the face of AI and the fluidity of consumer ethics in a world of updatable smart objects.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly changing the ways in which we consume goods and services (Airoldi and Rokka Citation2022). AI-enabled recommendations of goods to purchase online and media to consume do not simply reflect consumers’ preferences but shape them to a considerable degree (Adomavicius et al. Citation2018). Puntoni et al. (Citation2020) argue to view AI not only as a neutral technology but as inherently embedded in social and political contexts.

Similar to the commodified television (Chitakunye and Maclaran Citation2014), agentic objects such as AI-enabled smart objects in the form of voice assistants, smartwatches, and robotic vacuum cleaners have rapidly become affordable commodities deeply embedded in everyday consumption practices. Smart objects do not only restructure consumption patterns (Hoffman and Novak Citation2018) but also actively reshape social relations (Schneider-Kamp and Askegaard Citation2022) through both enabling and constraining consumer experiences. AI-enabled recommendations and nudging influence decision-making processes and, ultimately, subtly but consistently erode consumer self-determination (Kopalle et al. Citation2022) and consumer autonomy (Floridi Citation2023). The AI might pre-select and thereby narrow consumption choices, encouraging consumers to partially or even completely delegate decision-making.

The discussion on whether AI has its own ethical compass or is always the result of the choices of human agents is far from being settled (De Cremer and Kasparov Citation2021). Notwithstanding, it is safe to assume that the consumption of smart objects, which recommend and nudge consumers to act in certain ways, has a significant effect on consumer ethics. Alas, research on consumer ethics that takes the agentic nature of smart objects into account is still in its infancy (Fuentes and Sörum Citation2018). Extant perspectives on consumer ethics struggle to accommodate non-human actors into theoretical and methodological frameworks.

In this article, I reflect on how consumer researchers might investigate consumer ethics in the age of AI-enabled smart objects. First, I review the inherent limitations of extant consumer ethics perspectives in unraveling how the consumption of smart objects reshapes what consumers consider to be right or wrong in a specific consumption context. Then, arguing that consumer ethics could and should be viewed as an emergent property, I develop a novel conceptual framework for consumer ethics grounded in assemblage theory. Drawing on exemplars ranging from wearables to autonomous robots, I illustrate the potential of this perspective. Finally, I conclude by outlining fruitful directions for future research on the matter.

Consumer ethics and smart objects

Consumer ethics can broadly be viewed as encompassing what pertains to doing the right thing in a given consumption setting, including both deontological (whether an action is right or wrong based on inherent moral principles) and teleological (what desired and undesired consequences of the consumption are) aspects (Vitell Citation2003). While the last decade has witnessed an explosion in research on specific teleological aspects such as sustainable and responsible consumption (Falcão and Roseira Citation2022), here, I focus less on how ethical the consumption itself is but rather on how the consumption of agentic objects such as AI-enabled smart objects affects and structures consumer ethics.

Fuentes and Sörum (Citation2018) investigated how smart objects assembled from smartphones and ethical consumption apps employ their agency to affect consumer ethics regarding sustainability. This article goes beyond this specific type of smart object and specific understanding of consumer ethics by developing a conceptual framework for how the agency of smart objects affects consumer ethics not limited to sustainability but also able to encompass other ethical aspects. These aspects include consumer self-determination, consumer health and well-being, and moral principles and ethical dilemmas of mundane everyday consumption contexts such as caring for family members or adhering to contractual or informal promises towards others. It is important to note that there are no agreed-upon criteria for what comprises ethical conduct and perspectives are multiple and often diverging even when limited to the context of green consumerism (Moisander Citation2007).

Carrington et al.’s (Citation2021) review of perspectives on consumer ethics uses among others agency as a distinguishing dimension, where agency can either be individual (emanating from a single consumer) or collective (materializing from the relations and interactions of a group of consumers). As we are interested in agentic objects, this dimension deserves express consideration.

Extant consumer ethics perspectives viewing agency as individual are challenged by the agency and capacities of smart objects, which, enabled by AI, possess the capacities to recommend actions to the consumer and, in some cases, even take decisions autonomously. Even when adopting De Cremer and Kasparov’s (Citation2021) view of the agency of the AI always being grounded in human choices, these choices are without loss of generality the choices of other individuals, i.e. of agents external to the consumer.

Consumer ethics perspectives viewing agency as collective seem more promising at first, as the consumer might be seen as grouped with the smart object and the agency as materializing from the relations and interactions of the consumer and the object. Alas, extant consumer ethics perspectives are based on assumptions of homogeneity of the members of the collective. These assumptions can vary in strength, from assuming homogeneity of the consumers comprising the collective along multiple dimensions (Scaraboto and Fischer Citation2013) to highly diverse consumer collectives (Chatzidakis and Maclaran Citation2020).

Regardless of strength, the underlying assumption of the collectives comprising exclusively human agents limits the utility of extant consumer ethics perspectives when dealing with collectives comprising both human agents and agentic objects. These collectives are heterogenous and horizontal rather than homogenous and hierarchical in nature (Gehman, Sharma, and Beveridge Citation2022), being not only diverse along psychological, demographic, socioeconomic, and cultural dimensions but also comprised of agents of widely differing functional capacities, properties, and expressive roles (Schneider-Kamp and Askegaard Citation2022).

AI-enabled smart objects are furthermore often embedded in an elusive vast socio-technical ecosystem (Carrington and Ozanne Citation2022) of online peers, data, and information systems (Crawford and Joler Citation2018), necessitating a perspective on consumer ethics able to grasp and unravel this complexity. While the heterogeneity of agents is highlighted and aggravated in the case of smart objects, one might argue that even simple non-smart agentic objects such as seat belt alarms (Latour Citation1992) have the capacities to affect consumer ethics – here, by nudging the consumer into behavior deemed right by external instances interested in road safety.

Assembling consumer ethics

Research into the intricacies of consumption involving heterogeneous consumers and possibly smart objects increasingly relies on socio-material theories in the tradition of Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) assemblages. DeLanda (Citation2006) argues for an assemblage theory taking its point of departure in components as foundational entities that have the capacity to affect other components through the relations within the assemblages they are currently attached to. These relations are conducive to affective flows that continuously subject the assemblage to processes of stabilization and change (Feely Citation2020).

Consumption assemblages

Generalizing Hoffman and Novak’s (Citation2018) concept of consumer-object assemblages, I define consumption assemblages as assemblages comprising both human consumers and non-human material and expressive components relevant to a specific consumption context. More specific consumption assemblages can be viewed as subassemblages (DeLanda Citation2006) nested in larger consumption assemblages, allowing the study of consumption phenomena at different scales (Huff, Humphreys, and Wilner Citation2021). At each scale, the assemblage is a whole that is more than the sum of the parts, i.e. the assemblage transcends the simple aggregation of the individual components. Molander, Ostberg, and Peñaloza (Citation2022) develop subassemblages into a tool for focusing on clearly delineated aspects of a large assemblage such as value creation in consumer subassemblages of brand assemblages.

DeLanda (Citation2006) defines the identity of an assemblage as the properties, capacities, and expressive roles that emerge from the relations and interactions between its components. Note that this use of the term “identity” represents a vital conceptualization from assemblage theory as also employed by Hoffman and Novak (Citation2018) and is distinct from the common use of the term “identity” as a synonym for an individual or group’s understanding of themselves as an entity.

One area that has been studied intensively using assemblage theory is how families consume. Huff and Cotte (Citation2016) study consumption in families with seniors, demonstrating how family assemblages are subject to continuous evolution as changing capacities of its components reconfigure the relations within the assemblage. Hoffman and Novak (Citation2018) employ DeLandian assemblage theory to reconceptualize consumer experiences in consumption assemblages involving families and smart objects such as voice assistants, finding that emergent consumer experiences can be both enabling and constraining. Schneider-Kamp and Askegaard (Citation2022) study how integrating smart objects into family assemblages with elderly consumers affects social roles and relations, increasing the capacities of the elderly at the price of an increased burden on their family members.

The emerging ethics of assemblages have received some attention, though virtually only from a philosophical perspective. The starting point for these discussions of assembled ethics is given by Deleuze and Guattari, who move the characterizing questions of ethics from “What ought I to do?” to “What am I capable of?” and “What might I become?” (Bowden Citation2020). In other words, from questions on what is right and wrong to questions about the formation of capacities and identities.

Moving the fundamental questions and outlook of ethics from reliance on universal standards of morality is a laudable and highly appreciated philosophical project. However, it does little good in investigating how AI-enabled smart objects and consumers jointly reshape classical ethical questions of “What ought I to do?.” The backbone of a consumer ethics aware of and conducive to smart objects is precisely the emergence of new standards of what is considered right and wrong in the context of a concrete consumption assemblage comprising consumers and smart objects.

Consumer ethics assemblages

To develop a novel conceptual framework for consumer ethics conducive to studying and understanding the role of agentic objects, I propose to consider consumer ethics assemblages as focused subassemblages delineated to the components and relations of encompassing consumption assemblages that have a bearing on the enactment of consumer agency. The emergence of ethics from the relations and interactions of consumers with agentic objects maps directly to one of the focal points of assemblage theory, the emergence of properties, capacities, and expressive roles of the whole of the assemblage from the relations and flows between its components.

To formally capture this emergence, I define consumer ethics as the identity of the consumer ethics assemblage, i.e. its emergent properties, capacities, and expressive roles (DeLanda Citation2006). Then, for a given constellation of consumers and agentic objects considered, viewing them as constituting a consumer ethics assemblage allows addressing questions of what the consumer ethics are, how they are coming to be, and what meaning they carry. The answers to these questions are precisely embedded in the emergent properties, capacities, and expressive roles coconstituting the identity of this consumer ethics assemblage. The emergent ethics is both shaped by and shapes the agency of the human and non-human agentic components of the assemblage, instigating an iterative process of adjustment of the moral principles underlying consumer decision-making.

While ethics may not always be the dominant aspect in a given consumption context, any concrete act of consumption is embedded in socioeconomic and cultural contexts. Thus, it is subject to ethical considerations such as those pertaining to its impact on available resources, the mental or physical well-being of the involved or other humans, or its symbolic significance to others (Tikkanen, Heinonen, and Ravald Citation2023). In this sense, consumer ethics can be viewed as necessarily emerging from the capacities and relations of the involved human actors and non-human material and expressive entities.

The emergent ethics in some mundane consumption contexts involving non-agentic objects can be abstracted to be equivalent to the ethics of the consumer. Such an abstraction is challenged by the inherent redistribution of agency in consumption contexts incorporating AI-enabled smart objects such as voice assistants (McLean, Osei-Frimpong, and Barhorst Citation2021). The flows of the assemblage along the relations between human and non-human agents reshape the moral principles guiding the human consumer. This reshaping occurs on a wide spectrum of possibilities. On one side of the spectrum, there are processes of reconsideration of moral principles at the conscious level as a result of the imbuement of new capacities of the consumer through the newly established relations. On the opposite side of the spectrum, the consumer is subjected to and often unaware of the gradual reinforcement of externally determined moral principles based on the reiteration effect.

It is important to note that consumer ethics assemblages, as any assemblages, rarely remain stable for extended periods but undergo processes of deterritorialization and reterritorialization (Feely Citation2020). Whenever an agentic object is attached to a consumer ethics assemblage or the capacities of an already attached object evolve, this causes a process of change as existing relations and interactions become modified or invalidated while new relations and interactions surface. This process is followed by a process of stabilization where a temporary stable state is reached until the composition of the assemblage changes again or relevant capacities of the agentic objects evolve.

Mirroring how Hoffman and Novak (Citation2018) consider multiple levels of consumer experience, the ethical interactions of components in consumer ethics assemblages (with or without agentic objects) can be viewed as occurring on three levels:

Basic ethical interactions occur on a momentary timescale and are based on reflexes. As an example, consider a person noticing another person being about to fall and intervening to prevent that fall without any further cognitive consideration.

Aware ethical interactions occur on an episodic timescale and are based on discriminating and categorizing an episode and reacting with a learned response. A person might, for example, observe two other persons fighting and decide to intervene.

Conscious ethical interactions accumulate, integrate, and reflect on multiple episodes and might also draw on external knowledge. The person observing the fighting couple might base their decision to intervene or not on an experience-based consideration of whether there is a sufficient risk of harm occurring to infringe on their right to privacy.

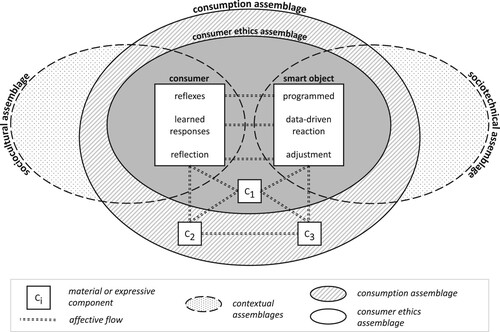

While the above distinction into levels uses a human perspective for exemplifying these three levels, smart objects are also capable of at least basic and aware ethical interactions. characterizes and contrasts how the different levels take shape for human consumers and smart objects.

Table 1. Levels of ethical interactions in consumer ethics assemblages.

This proposed conceptualization of consumer ethics as the identity of a consumer ethics assemblage nested in a consumption assemblage and with interactions occurring on three distinct levels is illustrated in . While the consumer ethics assemblage focuses on the interactional aspects of consumers and smart objects, the framework explicitly acknowledges that socialization and embodied cultural preferences influence what consumers consider as right and wrong, as well as the embeddedness of smart objects into complex socio-technical ecosystems. The following sections demonstrate how this conceptual framework is not only useful for studying and understanding how extant agentic objects such as AI-enabled smart objects affect consumer ethics but also to identify potential challenges and opportunities associated with the consumption of future technologies yet to be invented and developed.

Exemplars of AI-enabled smart objects

The use of illustrating exemplars has a long tradition in socio-material research perspectives, from Latour’s (Citation1992) seat belt alarm to Hoffman and Novak’s (Citation2018) artificially intelligent voice assistant and Franco et al.’s (Citation2022) refrigerator. This article summons two other categories of consumer goods that have become commonplace commodities during the last decade: the smartwatch and the robotic vacuum cleaner (RVC) which exemplify a wearable smart object that directly and continuously interacts with one dedicated consumer and an autonomous robot that interacts predominantly with the physical surroundings of a household and more loosely with potentially multiple household members, respectively.

These two exemplars represent abstracted cases based on longitudinal immersion with these technologies, as well as observations and discussions with other consumers. They serve the purpose of illustrating the conceptual developments of this article rather than representing independent small-scale studies. Both exemplars represent agentic objects that employ machine learning, where the recursivity of algorithms (Airoldi and Rokka Citation2022) instigates a process of mutual adaptation between consumers and smart objects based on data and feedback from their interactions.

The secluded tandem of consumer and smartwatch

In this first exemplar, the consumer has purchased a smartwatch with a multitude of sensors that track data such as the wearer’s movements, pulse, first derivative electrocardiogram, and blood oxygen level. The consumer and the smartwatch form a relatively stable consumption assemblage, which, at first sight, appears to be a rather secluded tandem that is relatively isolated from other components. An assemblage analysis mapping the capacities of and flows between the components (Feely Citation2020) would reveal a deep and extensive relation along which one could observe a multitude of affective flows. Zooming in on the consumer ethics subassemblage of this consumption assemblage would among others highlight two kinds of affective flows relevant to the emerging ethics.

First, the smartwatch nudges and, at times, nags the consumer via a multitude of mechanisms, ranging from notifications to stand up to workout recommendations. These ethical interactions happen mostly on the aware level, with the smartwatch using its sensor data to assess the type and amount of movement and tailor recommendations and the timing of notifications to the movement patterns of the consumer. Basic ethical interactions can also be found, though, e.g. in pre-programmed warnings about the smartwatch not being a reliable medical diagnostic device.

Second, the flows relevant to the consumer ethics assemblage are not limited to a one-way street. In the reverse direction, i.e. from the consumer to the smartwatch, we have affective flows of disregard, preferences, and intent along the relation. The consumer might, for example, disregard nudging notifications on the basic level, indicate periods in which notifications and recommendations are unwished for on the aware level, or adjust goals for the type and amount of movement on the conscious level. In the third type of interaction, external knowledge, accumulated previous episodic interactions, and reflections on these can be assumed to play into the process of adjusting future goals.

The emergent consumer ethics of the assemblage is clearly neither identical to the ethics of the consumer nor the one ingrained into the workings of the smartwatch in isolation. On the contrary, the emerging ethics are constructed in a complex interplay of affective flows that establishes new moral principles of what the consumer ought to do. This initial “negotiation” of the consumer ethics is an instance of a process of change that at some point in time yields a relatively stable state where the new principles guide the ethical interactions of the consumer. These principles might represent a reinforcement of moral principles the consumer already possesses, but they might also initially clash with existing principles, necessitating a reconciliation process where the reiteration effect favors those principles time and time again encouraged by the agentic smartwatch.

Reality is, as usual, more complex than the abstraction of a tandem consumer ethics assemblage would imply. To capture the emergence of the consumer ethics more fully, other components have to be considered as part of the assemblage. For many consumers, smartwatches also integrate social aspects through data sharing with peers, establishing new norms and, consequently, adjusting guiding principles for a healthy lifestyle.

Furthermore, the consumer ethics assemblage also comprises the hardware and software producers, the operating system and apps of the smartwatch including updates, AI models, and internet databases that the smartwatch consults, and even peers that the consumers share their sensor data with. Processes of change and stabilization might, for example, be kickstarted by a software update from the producer that modifies the AI models the smartwatch relies upon for providing recommendations to the consumer. These modified AI models might, in turn, change the affective flows between the consumer and the smartwatch. Ultimately, such an update can yield significantly modified moral principles and, consequently, consumer ethics.

The tale of the little robotic vacuum cleaner

In this second exemplar, the consumer has just purchased an RVC that represents a distant descendant of the original iRobot Roomba and can be controlled through an AI-enabled voice assistant. The RVC is just starting to be integrated into a household comprising a family with two adults, two children living at home, and a labradoodle. The consumption assemblage is embedded into the family assemblage and contains a multitude of components such as the four human family members, the one canine family member, the RVC with its charging station, the voice assistant, and the physical surroundings of the household including floors, stairs, chairs, tables, sofas, beds, doors, and carpets.

The non-agentic non-human components such as the floors, carpets, and furniture are centrally and inherently involved in central acts of this consumption assemblage but have little to no bearing on ethical aspects and are, thus, not considered as part of the consumer ethics assemblage. Despite this delineation and the RVC being designed to map and clean the household with its static and dynamic obstacles autonomously, the consumer ethics assemblage nevertheless is far from trivial. There are affective flows of supervision and control from the adult consumers to the RVC, which receives either spatiotemporal constraints or obligations, i.e. it is either prevented from cleaning at certain points of time or in certain spaces or tasked to clean certain spaces at certain times. These ethical interactions happen at the conscious and aware levels, respectively. In addition, at the basic and aware levels, the child consumers interfere in this by starting the RVC at random times with the intent of entertainment rather than cleaning.

The RVC uses AI for planning its cleaning path and schedule in an attempt to fulfill its primary mission, i.e. the regular autonomous cleaning of the household while navigating the constraints and obligations imposed by the consumers, as well as the obstacles of the household. In the course of this attempt, the RVC might interact with different components in different ways. On the basic level, it might stop in order to avoid bumping into a suddenly appearing floorstanding vase or one of the five family members. On the aware level, it might discover and map ways around new obstacles or integrate previously inaccessible areas of the household.

The emergent consumer ethics are complex, depend on the algorithms and AI models employed, and are riddled with minor but far from trivial ethical dilemmas. Pars pro toto, the labradoodle might be scared of the RVC and the noise it produces while the human family members would prefer to run the RVC while they are out of the house and the dog is alone with the RVC. As this particular RVC and its cousins currently on the market lack the capacity for conscious ethical interactions, the ethical decision-making regarding when the RVC ought to run remains with the adult consumers.

Conscious levels of consumer ethics as defined in might not principally be out of reach of smart objects, though, as there have been indications that Theory of Mind on the level of a nine-year-old human might recently have emerged in the latest generation of AI-powered chatbots (Kosinski Citation2023). Here, Theory of Mind refers to an agent’s ability to understand and interpret the mental states of other agents, i.e. their knowledge, beliefs, desires, and intentions. While such chatbots exhibit the agency necessary to successfully solve Theory of Mind tasks, following Floridi’s (Citation2023) distinction between agency and intelligence this neither necessarily indicates intelligence nor consciousness. Floridi’s distinction, how philosophically interesting and fruitful it may be, arguably has little bearing on the ability of smart objects to interact on conscious levels of consumer ethics, though, as agency and intelligence are indistinguishable in the face of the process-oriented definition of the levels of ethical interactions.

Notwithstanding these considerations, already in the initial phase of interacting with the RVC, the emergent consumer ethics deviate from those of the adult consumers in control of the RVC. Previously, it was considered the right behavior that a household member who made a mess on the floor would also be the one to clean up the mess to avoid someone else stepping on it or having to clean it up. Already a week into the consumption process, the RVC would be tasked to do so by one of the adult consumers through the voice assistant, forever changing the ethical landscape of the household. This change in ethics can be considered a shift from a deontological (“It is my obligation to clean up after myself!”) to a teleological (“The RVC will take care of it!”) perspective on consumer ethics, mirroring hedonic preferences of the consumers.

While the RVC provides an understandable exemplar, an analysis of the consumer ethics assemblage of self-driving cars would reveal similar but significantly more impactful ethical interactions and dilemmas. This holds even in everyday scenarios that are less contrived than in the purposively exaggerated Moral Machine experiment (Awad et al. Citation2018), where consumers are asked to decide on the ethics of a self-driving car that experiences a sudden break failure and needs to make conscious decisions as to which of two alternative groups of people to run over under a variety of external factors.

An example of an everyday scenario would be the consumer ethics emerging from the interplay of the self-driving car’s programming to choose the most fuel-economic routes to save costs and benefit the environment, on the one hand, and the consumer’s need for arriving timely to their destination and fulfill their obligation there, on the other hand. Here, the ethics of the smart object, which are grounded in sustainability, clash with the ethics of the consumer, whose situative ethics revolve around professional responsibilities.

Discussion and directions for future research

In this article, I developed a framework for consumer ethics based on viewing it as emerging from consumer ethics assemblages. This framework provides a novel perspective that is able to account for the agency of non-human actors in the production of consumer ethics, transcending assumptions of agency being limited to human actors (Chatzidakis and Maclaran Citation2020). Such a heterogeneous relational perspective is conducive to unraveling the often non-essential but surprisingly intricate and complex ethical dilemmas of everyday consumption (Fuentes and Sörum Citation2018).

Furthermore, equating consumer ethics with the identities of consumer ethics assemblages provides a take on the ethics of assemblages that is able to simultaneously accommodate both deontological and teleological aspects, rendering moot the necessity of entirely abandoning the far from fully outmoded question of “What ought I to do?.” This enables the investigation of consumer ethics to extend beyond specific consumption contexts such as socially responsible consumption (Falcão and Roseira Citation2022) to encompass various forms of AI-enhanced everyday consumption.

Beyond its theoretical and foundational implications for consumer research and the application and further development of assemblage theory, the novel framework for consumer ethics introduced opens up a wide spectrum of sought-after consumer research on many of the fronts of digitalization and artificial intelligence currently considered across disciplinary, societal, and geographical borders (Loureiro, Guerreiro, and Tussyadiah Citation2021).

Health professionals are, for example, already facing ethical issues of how to deal with diagnoses generated by the assemblage of patients and smartwatches through electrocardiogram functions able to detect atrial fibrillation (Shih et al. Citation2022), with overdiagnosis and overuse of medical resources threatening the health and well-being of other consumers (Tikkanen, Heinonen, and Ravald Citation2023). The trend toward patient-generated data and diagnoses can only be assumed to be aggravated by consumers obtaining health information and diagnoses in close interaction with chatbots (Lautrup et al. Citation2023). The increasing reliance on technology for monitoring and assessing their health state bears resemblance to the bio-politicized embodiment of consumer competences in the monitoring and assessment of product quality through food date labeling (Yngfalk Citation2016), demanding consumers researchers’ attention on the impacts of wearable AI.

Another central question is who decides on the ethics that consumer goods or services contribute to: Is it the prerogative of the producer or do consumers have a say in it? To which degree can the ethics of smart objects be configured, adjusted, and tuned to the preferences of the consumer (Chen et al. Citation2022)? And at what time scale are the ethics of the smart object decided, i.e. once and for all in the initial design, updated during the product life cycle, or updated while in use?

De Cremer and Kasparov’s (Citation2021) argument that all ethics ultimately stem from human choices certainly holds for a seat belt alarm, where human-decided ethics are pre-programmed into a basic electronic circuit checking for whether a seat is used, the belt is open, and the car is moving, sounding an alarm if these three conditions concur. But with state-of-the-art voice assistants, chatbots, and self-driving cars increasingly utilizing and learning from previous interactions with consumers (Mariani, Hashemi, and Wirtz Citation2023), AI-enabled smart objects might be in the process of acquiring an inherent ethical compass, particularly, if they were equipped with the ability to autonomously learn from episodic interactions independently of any human-supplied ethics and AI models. How would the commodification of smart objects with the capacity for conscious ethical interactions reshape everyday consumption? How would consumers be restricted and enabled by the presence of AI with the capacity for conscious ethical interactions in every conceivable aspect of their lives?

Critical consumer research should also investigate the degree to which consumers possess the technological and domain literacy (Wallendorf Citation2001) to understand how the consumption of smart objects affects consumer ethics, particularly in the light of a limited consumer understanding of AI algorithms (Floridi Citation2023). One consumer with high levels of literacy might understand the workings of the smartwatch to a degree that they even become able to influence the recorded sensor data by consciously modifying their heart rate or holding their breath to influence measurements of pulse and blood oxygen, respectively. In contrast, another consumer with low literacy might be more vulnerable and struggle to make any sense of the nudging and recommendations of the smartwatch, leaving them with only the option of blindly accepting or rejecting the ethical interactions of the smartwatch.

These considerations, as well as the exemplars from the previous section, raise the questions of how agency and responsibility are distributed in the consumption of extant commodified smart objects and how this distribution would be affected by the development and commodification of smart objects capable of conscious ethical interactions with consumers (Iphofen and Kritikos Citation2021). Consumer researchers arguably have a moral obligation to study the implications of the weathering and erosion of human hegemony regarding consumer agency, consumer self-determination, and consumer ethics brought about by the consumption of AI-enabled services and goods.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna Schneider-Kamp

Anna Schneider-Kamp is an Associate Professor of Health and Consumption at the University of Southern Denmark. Her research primarily focuses on social determinants of health, with applications to health inequality and the digitalization of healthcare. Her work contributes to debates in medical sociology, health consumerism, and public health, shaping these interdisciplinary fields through socio-material and resource-based views on health. Her research appears in medical-sociological outlets such as Social Science & Medicine, Health, and Social Theory & Health, consumer outlets such as the Journal of Marketing Management and Consumption Markets & Culture, as well as in medical outlets such as the Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice and BMJ Open Heart.

References

- Adomavicius, G., J. Bockstedt, S. P. Curley, J. Zhang, and S. Ransbotham 2018. “The Hidden Side Effects of Recommendation Systems.” MIT Sloan Management Review. [Preprint]. Accessed November 21, 2022. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-hidden-side-effects-of-recommendation-systems/.

- Airoldi, M., and J. Rokka. 2022. “Algorithmic Consumer Culture.” Consumption Markets & Culture 25 (5): 411–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2022.2084726.

- Awad, E., Sohan Dsouza, Richard Kim, Jonathan Schulz, Joseph Henrich, Azim Shariff, Jean-François Bonnefon, and Iyad Rahwan. 2018. “The Moral Machine Experiment.” Nature 563 (7729): 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0637-6.

- Bowden, S. 2020. “Assembling Agency: Expression, Action, and Ethics in Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus.” The Southern Journal of Philosophy 58 (3): 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjp.12384.

- Carrington, M., Andreas Chatzidakis, Helen Goworek, and Deirdre Shaw. 2021. “Consumption Ethics: A Review and Analysis of Future Directions for Interdisciplinary Research.” Journal of Business Ethics 168 (2): 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04425-4.

- Carrington, M. J., and J. L. Ozanne. 2022. “Becoming Through Contiguity and Lines of Flight: The Four Faces of Celebrity-Proximate Assemblages.” Journal of Consumer Research 48 (5): 858–884. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucab026.

- Chatzidakis, A., and P. Maclaran. 2020. “Gendering Consumer Ethics.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 44 (4): 316–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12567.

- Chen, S., Han Qiu, Shifei Zhao, Yuyu Han, Wei He, Mikko Siponen, Jian Mou, and Hua Xiao. 2022. “When More is Less: The Other Side of Artificial Intelligence Recommendation.” Journal of Management Science and Engineering 7 (2): 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmse.2021.08.001.

- Chitakunye, P., and P. Maclaran. 2014. “Materiality and Family Consumption: The Role of the Television in Changing Mealtime rituals.” Consumption Markets & Culture 17 (1): 50–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2012.695679.

- Crawford, K., and V. Joler. 2018. Anatomy of an AI System: The Amazon Echo as an Anatomical map of Human Labor, Data and Planetary Resources. New York, NY: AI Now Institute and Share Lab. Accessed February 28, 2023. http://www.anatomyof.ai.

- De Cremer, D., and G. Kasparov. 2021. “The Ethical AI—Paradox: Why Better Technology Needs More and Not Less Human Responsibility.” AI and Ethics 2: 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-021-00075-y.

- DeLanda, M. 2006. A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London: Continuum.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Falcão, D., and C. Roseira. 2022. “Mapping the Socially Responsible Consumption gap Research: Review and Future Research Agenda.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 46 (5): 1718–1760. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12803.

- Feely, M. 2020. “Assemblage Analysis: An Experimental new-Materialist Method for Analysing Narrative Data.” Qualitative Research 20 (2): 174–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794119830641.

- Floridi, L. 2023. The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence: Principles, Challenges, and Opportunities. Edited by L. Floridi. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198883098.003.0002.

- Franco, P., R. Canniford, and M. Phipps. 2022. “Object-Oriented Marketing Theory.” Marketing Theory 401. https://doi.org/10.1177/14705931221079407.

- Fuentes, C., and N. Sörum. 2018. “Agencing Ethical Consumers: Smartphone Apps and the Socio-Material Reconfiguration of Everyday Life.” Consumption Markets & Culture 22 (0): 131–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2018.1456428.

- Gehman, J., G. Sharma, and ‘Alim Beveridge. 2022. “Theorizing Institutional Entrepreneuring: Arborescent and Rhizomatic Assembling.” Organization Studies 43 (2): 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406211044893.

- Hoffman, D. L., and T. P. Novak. 2018. “Consumer and Object Experience in the Internet of Things: An Assemblage Theory Approach.” Journal of Consumer Research 44 (6): 1178–1204. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx105.

- Huff, A. D., and J. Cotte. 2016. “The Evolving Family Assemblage: How Senior Families “do” family.” European Journal of Marketing 50 (5/6): 892–915. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2015-0082.

- Huff, A. D., A. Humphreys, and S. J. S. Wilner. 2021. “The Politicization of Objects: Meaning and Materiality in the U.S. Cannabis Market.” Journal of Consumer Research 48: 22–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucaa061.

- Iphofen, R., and M. Kritikos. 2021. “Regulating Artificial Intelligence and Robotics: Ethics by Design in a Digital society.” Contemporary Social Science 16 (2): 170–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2018.1563803.

- Kopalle, P. K., Manish Gangwar, Andreas Kaplan, Divya Ramachandran, Werner Reinartz, and Aric Rindfleisch. 2022. “Examining Artificial Intelligence (AI) Technologies in Marketing Via a Global Lens: Current Trends and Future Research opportunities.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 39 (2): 522–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2021.11.002.

- Kosinski, M. 2023. ‘Theory of Mind May Have Spontaneously Emerged in Large Language Models’. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.02083.

- Latour, B. 1992. “Where are the Missing Masses? The Sociology of a few Mundane artifacts.” In Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change, edited by W. E. Bijker, and J. Law, 225–258. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Lautrup, A. D., Tobias Hyrup, Anna Schneider-Kamp, Marie Dahl, Jes Sanddal Lindholt, and Peter Schneider-Kamp. 2023. “Heart-to-Heart with ChatGPT: The Impact of Patients Consulting AI for Cardiovascular Health Advice.” Open Heart 10 (2): e002455. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2023-002455.

- Loureiro, S. M. C., J. Guerreiro, and I. Tussyadiah. 2021. “Artificial Intelligence in Business: State of the Art and Future Research Agenda.” Journal of Business Research 129: 911–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.001.

- Mariani, M. M., N. Hashemi, and J. Wirtz. 2023. “Artificial Intelligence Empowered Conversational Agents: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Business Research 161: 113838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113838.

- McLean, G., K. Osei-Frimpong, and J. Barhorst. 2021. “Alexa, Do Voice Assistants Influence Consumer Brand Engagement? – Examining the Role of AI Powered Voice Assistants in Influencing Consumer Brand Engagement.” Journal of Business Research 124: 312–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.045.

- Moisander, J. 2007. “Motivational Complexity of Green Consumerism.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 31 (4): 404–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2007.00586.x.

- Molander, S., J. Ostberg, and L. Peñaloza. 2022. “Brand Morphogenesis: The Role of Heterogeneous Consumer Sub-Assemblages in the Change and Continuity of a Brand.” Journal of Consumer Research, ucac009. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucac009.

- Puntoni, S., Rebecca Walker Reczek, Markus Giesler, and Simona Botti. 2020. “Consumers and Artificial Intelligence: An Experiential Perspective.” Journal of Marketing 85: 131–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242920953847.

- Scaraboto, D., and E. Fischer. 2013. “Frustrated Fatshionistas: An Institutional Theory Perspective on Consumer Quests for Greater Choice in Mainstream Markets.” Journal of Consumer Research 39 (6): 1234–1257. https://doi.org/10.1086/668298.

- Schneider-Kamp, A., and S. Askegaard. 2022. “Reassembling the Elderly Consumption Ensemble: Retaining Independence Through Smart Assisted Living technologies.” Journal of Marketing Management 38 (17–18): 2011–2034. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2022.2078862.

- Shih, P., Kathleen Prokopovich, Chris Degeling, Jacqueline Street, Stacy M. Carter, et al. 2022. “Direct-to-consumer Detection of Atrial Fibrillation in a Smartwatch Electrocardiogram: Medical Overuse, Medicalisation and the Experience of consumers.” Social Science & Medicine 303: 114954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114954.

- Tikkanen, H., K. Heinonen, and A. Ravald. 2023. “Smart Wearable Technologies as Resources for Consumer Agency in Well-Being.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 58 (2–3): 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/10949968221143351.

- Vitell, S. J. 2003. “Consumer Ethics Research: Review, Synthesis and Suggestions for the Future.” Journal of Business Ethics 43 (1): 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022907014295.

- Wallendorf, M. 2001. “Literally Literacy: Table 1.” Journal of Consumer Research 27 (4): 505–511. https://doi.org/10.1086/319625.

- Yngfalk, C. 2016. “Bio-Politicizing Consumption: Neo-Liberal Consumerism and Disembodiment in the Food Marketplace.” Consumption Markets & Culture 19 (3): 275–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2015.1102725.