Abstract

Two single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on oxytocin-related genes, specifically the oxytocin receptor (OXTR) rs53576 and the CD38 rs3796863 variants, have been associated with alterations in prosocial behaviors. A cross-sectional study was conducted among undergraduate students (N = 476) to examine associations between the OXTR and CD38 polymorphisms and unsupportive social interactions and mood states. Results revealed no association between perceived levels of unsupportive social interactions and the OXTR polymorphism. However, A carriers of the CD38 polymorphism, a variant previously associated with elevated oxytocin, reported greater perceived peer unsupportive interactions compared to CC carriers. As expected, perceived unsupportive interactions from peers was associated with greater negative affect, which was moderated by the CD38 polymorphism. Specifically, this relation was stronger among CC carriers of the CD38 polymorphism (a variant thought to be linked to lower oxytocin). When examining whether the OXTR polymorphism moderated the relation between unsupportive social interactions from peers and negative affect there was a trend toward significance, however, this did not withstand multiple testing corrections. These findings are consistent with the perspective that a variant on an oxytocin polymorphism that may be tied to lower oxytocin is related to poor mood outcomes in association with negative social interactions. At the same time, having a genetic constitution presumed to be associated with higher oxytocin was related to increased perceptions of unsupportive social interactions. These seemingly paradoxical findings could be related to previous reports in which variants associated with prosocial behaviors were also tied to relatively more effective coping styles to deal with challenges.

Lay summary

Genetic variants related to the hormone oxytocin have previously been associated with alterations in social behaviors, such as trust, empathy and social support. Among 476 undergraduate students, perceived unsupportive social interactions from peers was associated with greater negative affect, but this association was stronger among participants with a certain genetic variant on an oxytocin related gene, compared to those who did not have this variant (i.e. CC carriers of the CD38 polymorphism rs3796863 compared to A carriers). These findings are consistent with the perspective that in the context of certain negative social environments, oxytocin genes might be related to poor mood outcomes.

Introduction

Oxytocin is a hormone thought to influence a wide range of prosocial behaviors, emotions and attitudes (Bartz et al. Citation2011; Feldman, Citation2012), and may have implications for mental health (McQuaid et al., Citation2014). Prosocial behaviors also vary with genetic variants of the oxytocin receptor (OXTR). Specifically, the OXTR single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs53576, which occurs on the third intron of the OXTR gene and involves a guanine (G) to adenine (A) substitution (Inoue et al., Citation1994), was associated with lower positive affect and self-esteem (Lucht et al., Citation2009; Saphire-Bernstein et al., Citation2011), prosocial behaviors (Krueger et al., Citation2012; Rodrigues et al., Citation2009; Tost et al., Citation2010), increased risk for an alcohol use disorder (Vaht et al., Citation2016), and higher depressive symptoms (Saphire-Bernstein et al., Citation2011). As well, the A allele of the OXTR polymorphism has been associated with less social support seeking during distress (Kim et al., Citation2010) and greater emotional withdrawal among individuals with psychosis (Haram et al., Citation2015). Although several studies have linked the A allele for the rs53576 SNP with lower social functioning and negative affect, a meta-analysis suggested that the evidence for this association was acutally weak (Bakersmans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, Citation2014).

Alternatively, oxytocin may serve to increase sensitivity to social experiences (Bradley et al., Citation2011; Hostinar et al., Citation2014; McQuaid et al., Citation2013). For instance, the G allele of the OXTR rs53576 polymorphism has been tied to heightened sensitivity in the form of greater feelings of rejection following social ostracism (McQuaid et al., Citation2015), and negative mood outcomes following early life stressful experiences, which were limited among A carriers (Bradley et al., Citation2011; Hostinar et al., Citation2014; McQuaid et al., Citation2013). As well, individuals with the GG genotype were more sensitive to the effects of intranasal oxytocin and displayed increased neural responses (in the left ventral caudate nucleus) during a social cooperation game (Feng et al., Citation2015). It was suggested that certain genetic variants could influence neuronal plasticity, so that both positive and negative experiences, would have a greater impact on later behavioral and emotional outcomes (Belsky et al., Citation2009; Belsky & Pluess, Citation2009).

Beyond OXTR variants, recent efforts assessed polymorphisms in the gene which codes for CD38, a transmembrane glycoprotein which is involved in the regulation of central oxytocin release (Higashida et al., Citation2012; Jin et al., Citation2007). The rs3796863 SNP located on intron 7 on the CD38 gene involves a cytosine (C) to adenine (A) substitution (Malavasi et al., Citation2008). Healthy human participants homozygous for the C allele displayed deficits in the processing of social stimuli (Sauer et al., Citation2012) and low plasma oxytocin levels (Feldman et al., Citation2012). Among individuals with severe forms of autism spectrum disorder, the C allele was associated with decreased CD38 expression in lymphoblastoid cells (Lerer et al., Citation2010). However, as with the OXTR rs53576 polymorphism, not all studies supported the perspective that the C allele of the CD38 rs3796863 polymorphism represents a vulnerability factor for negative behavioral and emotional outcomes (Algoe & Way, Citation2014; McQuaid et al., Citation2016; Tabak et al., Citation2016). Given the still limited number of studies examining the relation between the CD38 gene and behavior, it is difficult to discern the link between this gene and specific prosocial behaviors or pathological conditions.

Although oxytocin has been examined in response to various social stressors (Heinrichs et al., Citation2003; McQuaid et al., Citation2014; Taylor et al., Citation2000), its relation to certain forms of social stressors, such as receiving subtle negative social responses has been minimally assessed. Unsupportive social interactions refer to experiencing negative responses from others when support was reasonably expected (Ingram et al., Citation1999, Citation2001; Song & Ingram, Citation2002). They comprise responses such as, blaming the individual, bumbling attempts to offer support, distancing from the individual, or minimizing the individual’s problems. Unsupportive social interactions, can act as a significant stressor to the individual, and can contribute to depressive symptoms above and beyond the impact of social support. The impact of unsupportive social interactions on well-being might also be dependent on how an individual copes with stressors. Among A carriers of the OXTR polymorphism rs53576, higher unsupportive social interactions were tied to greater depressive symptoms in association with higher emotion- and lower problem-focused coping, whereas these relations were less evident among GG homozygotes (McInnis et al., Citation2015).

The purpose of the present study was to build on existing research as it relates to the associations between social stressors and oxytocin-related polymorphisms on well-being. To date, the conflicting findings could suggest that the links between certain oxytocin variants and well-being are context specific; in particular associations may depend on the nature of the social stressor examined. As such, the current study sought to examine perceived experiences of unsupportive social interactions, and assessed whether the OXTR rs53576 and CD38 rs3796863 SNPs moderated the relation between unsupportive responses and current affective states. The current study was a continuation of a previously reported study (i.e. some of the sample overlaps with the sample used in the McInnis et al., Citation2015 report). As indicated in McInnis et al. (Citation2015), an association was observed between unsupportive social interactions, less effective coping, and in turn greater depressive symptoms among A carriers of the OXTR polymorphism. Because of this, it was similarly expected in the current study that perceived unsupportive social interactions from parents and peers would be associated with higher negative- and lower positive mood among A carriers of OXTR polymorphism. Likewise, it was predicted that these associations would be stronger among CC carriers for the CD38 polymorphism.

Methods

Participants

The data used in the current report was pooled from two studies. The first study had a total of 225 participants and data examining measures of stress coping and depressive symptoms in relation to social interactions have previously been published from this sample (see McInnis et al., Citation2015). The remainder of the data (N = 251) was collected in a second phase of the first study in an effort to increase the sample size in order to examine the research questions of interest to the current study. Individuals were eligible to participate in the current study if they were enrolled as an undergraduate student at Carleton University. Data were included from those participants who were White/Euro-Caucasian. This data inclusion criterion was used in order to control for variability in the genetic variants across ethnic groups (e.g. Kim et al., Citation2010). Unfortunately, the sample sizes in other ethnic groups were too small for analysis to occur separately across the genotypes. A total of 476 White/Euro-Caucasian male (n = 131) and female (n = 345) undergraduate students were recruited through campus postings and a university online-recruitment system. Participants’ ages ranged from 17–35 years (M = 19.44, SD = 2.45). Socioeconomic status (SES) was also assessed, and approximately 26% of participants reported an annual family gross income of $44 999 or under, 43% reported between $45 000–104 999, and 31% reported an income of $105 000 or more.

Procedure

All participants provided written informed consent, and were presented with several questionnaires that measured demographic information, current mood and perceived unsupportive social interactions from parents and peers. Following this, a saliva sample was obtained from participants for subsequent DNA extraction. Upon study completion, all participants were given a written debriefing form, as well as researcher contact information. All procedures for the current study were approved by the Carleton University Ethics Committee for Psychological Research.

Genotyping

Saliva samples for DNA were collected using Norgen collection kits (Norgen Biotek Corp., Thorold, Ontario, Canada). Genomic DNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions and samples were diluted to approximately equal concentration (10 ng/μL). DNA samples were sent for genotyping to McGill University and Génome Québec Innovation Center (Montreal, Canada). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to amplify the DNA, and QIAXcel was used to determine amplification status. Unincorporated dNTPs were removed using shrimp alkaline phosphatase. One probe per marker was used to perform a single base extension and the product was desalted using 6 mg of resin. Using a Samsung Nanodispenser, the product was spotted on a Sequenom 384 − well chip and the chip was read using a Mass Spectrometer. Manual analyses were performed for each marker. Primer sequences were as follows:

OXTR:

rs53576 forward: ACGTTGGATGTCCCCATCTGTAGAATGAGC

rs53576 reverse: ACGTTGGATGGCACAGCATTCATGGAAAGG

rs53576 probe: CTCTGTGGGACTGAGGA

CD38:

rs3796863forward: ACGTTGGATGGTTGCTGCTCCTGCTGTTTT

rs3796863reverse: ACGTTGGATGAAGGTGCACAGACCACTTAG

rs3796863probe: TCCTGCTGTTTTTTTGACCA

Allele frequency for the CD38 polymorphism included 210 individuals homozygous for the C allele, (156 females, 54 males), 199 CA heterozygotes (134 females, 65 males), and 53 homozygous for the A allele (43 females, 10 males). The distribution of genotypes for the OXTR polymorphism comprised: 213 individuals with the GG genotype (161 females, 52 males), 193 with the AG genotype (132 females, 61 males), and 57 with the AA genotype (41 females, and 16 males). Genotype distributions met Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium expectations for both the CD38 polymorphism χ2(1) = 0.31, p =.58, as well as the OXTR polymorphism χ2(1) = 1.64, p =.55. The original sample size was 476 but there were 13 individuals for the OXTR polymorphism and 14 individuals for the CD38 polymorphism for whom the genotype could not be determined. As such, subsequent analyses involving the OXTR and CD38 polymorphisms will comprise 463 and 462 individuals, respectively.

Measures

Mood

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (Watson et al., Citation1988) is a 41-item scale that examines the current mood states of participants. This scale assesses the levels of positive (e.g. “enthusiastic”, “happy”, “inspired”) and negative affective states (e.g. “distain”, “enraged”, “hostile”). Participants were asked to indicate how each adjective described how they felt at the moment, on a seven-point scale that ranged from not at all (0) to extremely (6). As well, participants were reassured there were no right or wrong answers and to be as honest as possible in indicating how they were feeling at the moment. Mean scores across items were calculated for both negative affect (Cronbach’s α =.90) and positive affect (Cronbach’s α =.91).

Unsupportive social interactions

Perceptions of unsupportive interactions were assessed using The Unsupportive Social Interactions Inventory (Ingram et al., Citation2001). This 24-item inventory was administered twice (once for parents and once for peers) to assess how often (from “none” (0) to “a lot” (4)) in recent weeks the participants' received negative or upsetting responses when talking to peers or parents about events in their life. The scale contains four subscales which include minimizing (efforts to force optimism, or to minimize the individual’s problems), distancing (behavioral or emotional disengagement), bumbling (uncomfortable or awkward behaviors), and blaming (criticism or finding fault). The subscales were highly correlated and as such, total mean scores of unsupportive social interactions were used (Peers: Cronbach’s α = .92; Parents: Cronbach’s α = .93).

Statistics

The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 for Windows software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Prior to conducting analyses on gene associations, the influence of potential confounding variables (i.e. gender and SES) on the measures assessed for the current study (i.e. unsupportive social interactions and affective states) were examined using multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) with univariate ANOVAs and Bonferroni’s post hoc follow-up. Analyses comparing genotypes were conducted by comparing A allele carriers to individuals with the GG genotype for the OXTR polymorphism and A carriers to individuals with the CC genotype for the CD38 polymorphism. Analyses assessing CD38 and OXTR genotype differences on perceptions of unsupportive social interactions from parents and peers, as well as positive and negative affect were conducted using MANOVAs with univariate ANOVAs, while controlling for SES and gender. A Bonferroni’s correction was utilized for all ANOVA follow-up comparisons.

Hierarchical regression analyses were performed to determine whether associations between unsupportive interactions from parents and peers and affective states were moderated by CD38 and OXTR genotypes. Due to the potential confounding effects of certain factors, such as gender and SES, these variables were controlled for in hierarchical analysis. Additionally, in keeping with recommendations by Keller (Citation2014) we also controlled for the impact of the interaction between these factors (e.g. Gender X Environment and Gender X Gene etc.) in the hierarchical regression analyses that examine the moderating effects of the genes of interest. Significant moderations were followed up using a web utility for simple slopes (Preacher et al., Citation2006). Standardized scores were used for all regression analyses.

In order to correct for multiple testing a p value threshold was calculated based on the variables of interest assessed in the hierarchical regression analyses. Specifically, because some of the factors of interest were correlated (i.e. unsupportive social interactions from peer and parents, as well as positive and negative affect) the covariance (r2) between these factor was calculated to allow for an estimate of the independence between these variables. The covariance between positive and negative affect was r2 = .007744 and the covariance between unsupportive social interactions from peers and unsupportive social interactions from parents was r2 = .357604. The p value threshold .05 was adjusted by dividing (1+ r2) × (1+ r2) × 2 (for the two SNPs assessed) this yielded a p value of .018233. Correlational analyses to assess relations between the measures separated by genotype groups were conducted using the Pearson Product Moment correlations.

Results

When examining the covariates (i.e. gender and SES) on the factors assessed, self-reported positive and negative mood states significantly varied as a function of gender, Pillai’s Trace, F (2, 469) = 10.05, p < .001, η2 = .041. No gender differences were observed between males and females on current negative affect F(1, 470) = .86, p = .35, η2 = .002, although males reported more positive affect F(1, 470) = 19.83, p <.001, η2 = .040. Multivariate analyses indicated an effect for gender on perceptions of unsupportive social interactions, Pillai’s Trace, F (2, 469) = 7.23, p = .001, η2 = 0.030. Specifically, univariate ANOVAs indicated that males and females did not differ on perceptions of peer unsupportive social interactions, F(1, 470) = 1.37, p = .25, η2 = .003, but there was a significant gender difference on perceived levels of parental unsupportive social interactions, wherein females reported greater levels than males F(1, 470) = 4.68, p = .03, η2 = .010. Perceptions of unsupportive social interactions did not vary as a function of SES, Pillai’s Trace, F (4, 924) = 2.13, p = .08, η2 = .009. Likewise, postive and negative affect did not vary as a function of SES, Pillai’s Trace, F (4, 924) = 1.24, p = .29, η2 = .005. All subsequent analyses controlled for gender and SES. A MANOVA, including all factors of interest together (i.e. covariates and genotypes) revealed that negative and positive affect did not vary as a function of either the CD38 gene, Pillai’s Trace, F (2, 439) = 2.17, p = .12, η2 = .010, or the OXTR polymorphism, Pillai’s Trace, F (2, 439) = .82, p = .44, η2 =.004. In contrast, perceptions of unsupportive social interactions varied by CD38 genotype, Pillai’s Trace, F (2, 437) = 3.07, p = .047, η2 = .014. Specifically, univariate ANOVAs with Bonferroni’s correction indicated that perceptions of peer unsupportive social interactions differed as a function of the CD38 genotype, F (1, 438) = 5.76, p = .017 η2 = .013. Specifically, A carriers perceived higher levels of unsupportive social interactions from peers (p =.01) than those with the CC genotype (See for descriptives). In contrast, parental unsupportive social interactions did not differ by CD38 genotype, although there was a trend in this regard, F (1, 438) = 3.81, p = .05, η2 = .009. The OXTR polymorphism was not associated with levels of perceived parental or peer unsupportive interactions Pillai’s Trace, F (2, 437) = .18, p = .83, η2 = .001 Correlational analyses were also conducted to determine how unsupportive social interactions related to the outcomes, separated by genotypes (see ).

Table 1. Mean and standard deviations of perceived unsupportive social interactions, negative and positive affect as a function of the OXTR rs53576 and CD38 rs3796863 polymorphisms.

Table 2. Correlations between perceived unsupportive social interactions and negative and positive affect as a function of the OXTR rs53576 and CD38 rs3796863 polymorphisms.

Moderating role of the CD38 and the OXTR polymorphism

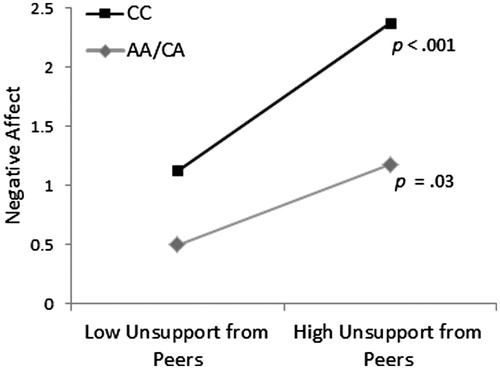

In examining the moderating role of the CD38 polymorphism in the relation between perceived unsupportive interactions from parents and peers to positive affect, no significant effects were observed ΔR2 = .00, ΔF (1, 442) =.08, p = .77, and ΔR2 = .00, ΔF (1, 441) = .01, p = .94, respectively. However, when negative affect was assessed as the outcome in relation to unsupportive social interactions from peers, a significant moderated effect for the CD38 polymorphism was found ΔR2 = .02, ΔF (1, 441) = 8.28, p = .004. The regression analysis revealed that perceived unsupportive social interactions from peers was related to higher negative affect, b = .62, t = 3.92, p <.001, but this was moderated by the CD38 genotype, b = −.28, t = −2.88, p = .004. Simple slopes revealed that the relation between higher perceptions of unsupportive interactions and negative affect was stronger among individuals who carried the CC genotype (p <.001) compared to A carriers (p = .03) (). No moderating effect of CD38 was observed when examining the association between perceived unsupportive relations from parents and negative affect ΔR2 = .00, ΔF (1, 442) = 0.46, p = .50.

Figure 1. The relationship between unsupportive social interactions and negative affect as moderated by the CD38 rs3796863 polymorphism (b = −.28, t = −2.88, p =.004). Perceptions of unsupportive social interactions from peers were associated with greater reports of negative affect, and this association was stronger among those with the CC genotype of the CD38 polymorphism compared to A carriers.

Upon examining the OXTR polymorphism, the associations between perceived unsupportive social interactions from peers and parents and positive mood were not moderated by the OXTR polymorphism ΔR2 = .00, ΔF (1, 443) = .78, p = .38, and ΔR2 = .01, ΔF (1, 444) = 3.12, p = .08, respectively. The relation between perceived unsupportive interactions from peers and negative affective state approached significance, ΔR2 = .01, ΔF (1, 443) = 4.84, p = .028, b = .22, t = 2.20, p = .028, but did not withstand the multiple testing p value threshold (p =.018). The relationship between perceptions of unsupportive interactions from parents and negative affect was not moderated by OXTR genotype ΔR2 = .00, ΔF (1, 444) = 1.29, p = .26.

In an effort to control for factors that might be associated with oxytocin system functioning and therefore could potentially impact associations between the genes and the variables assessed, a supplementary analysis was conducted. Although not all factors that could potentially influence the oxytocin system were collected in the current study (e.g. estradiol, menstrual cycle phase etc.), participants were asked about medication use, including oral contraceptives. When controlling for oral contraceptive use, results remained relatively unchanged. For example, when examining the significant relation between perceptions of unsupportive social interactions and the CD38 genotype, the p value for the MANOVA increased slightly from p = .047 to p = .049. The univariate ANOVA follow-up analysis p value decreased from p = .017 to p = .014. Results of the reported moderation analyses also remained relatively unchanged. Specifically, the p value for the regression model remained at p = .004 and the significance of the beta interaction term increased from p< .001 to p = .004.

Discussion

Together, the current findings indicated a modest association between A carriers of the CD38 polymorphism rs3796863 and greater perceptions of peer unsupportive social interactions compared to those homozygous for the CC genotype. However, findings indicated a stronger relationship between unsupportive social interactions from peers and negative affect for individuals with the CC genotype of the CD38 polymorphism in comparison A carriers. As well, there was a trend toward a significant moderation of the OXTR polymorphism on the relation between unsupportive social interactions from peers and negative affect; however, this did not withstand multiple testing corrections. Finally, a moderating effect for either polymorphism (OXTR and CD38) was not apparent when assessing unsupportive social interactions from parents as the predictor, or positive affect as the outcome.

Previously, the AA genotype of the CD38 polymorphism has been related to higher peripheral levels of plasma oxytocin (Kiss et al., Citation2011). As such, the observation that A carriers perceived more negative social interactions is in line with the view that oxytocin might promote elevated sensitivity to social cues. However, this effect was small and replication is required to determine the robustness of this association. Nonetheless, this finding is consistent with reports that the AA genotype of the CD38 polymorphism promotes greater social sensitivity to chronic interpersonal stress (Tabak et al., Citation2016).

The OXTR rs53576 polymorphism was not associated with perceptions of unsupportive social interactions, a finding consistent with our previous report with a smaller sample indicating that this polymorphism is not directly related to perceived levels of unsupportive interactions (McInnis et al., Citation2015). Of note, some of the sample used in the current study overlaps with the sample reported in McInnis et al. (Citation2015). Other studies that have examined the relation between the OXTR rs53576 polymorphism and perceptions of other forms of negative social interactions, such as a laboratory manipulation of ostracism, have observed that the G allele is directly associated with greater perceptions of rejection. However, experiences of unsupportive social interactions and social ostracism are qualitatively different, and therefore it is not surprising that the OXTR polymorphism might be related differently to these factors. As well, unlike other studies that have observed the OXTR 53576 is directly associated with negative mood (e.g. Saphire-Bernstein et al., Citation2011; Lucht et al., Citation2009), the current study did not observe this. This may be due to differences in study design, for example, the current study utilized a homogenous ethnic sample, whereas other studies (e.g. Saphire-Bernstein et al., Citation2011) included a mixed ethnic sample. This could have impacted differences in findings across the studies, particularly as the OXTR polymorphism is known to vary widely depending on ethnicity (e.g. Kim et al., Citation2010). However, Saphire-Bernstein et al. (Citation2011) did conduct an analysis examining ethnicity, which indicated that findings were relatively consistent across ethnic groups. In addition to ethnicity, the measures used across the studies differed. For example, Lucht et al. (Citation2009) assessed affective states within the last 4 weeks, whereas this study asked participants to report on their current mood states.

Despite the observation that the A allele of the CD38 polymorphism was associated with higher perceptions of peer unsupportive responses, our findings did not suggest a stronger association between perceptions of unsupportive social interactions and current negative affective states among A carriers compared to those with the CC genotype. Instead, it appeared that the association between perceived unsupportive interactions from peers and current negative affective state was stronger among individuals with the CC genotype compared to A carriers. In previous reports, the CC genotype of the CD38 polymorphism has been associated with lower peripheral oxytocin (Feldman et al., Citation2012). The observation in the current study that individuals with the CC genotype reported negative mood in association with higher perceptions of unsupportive social interactions is consistent with studies that have suggested it might represent a vulnerability factor to lower social functioning (Feldman et al., Citation2012b; Sauer et al., Citation2012). It is uncertain why associations between the CD38 polymorphism and unsupportive social interactions were present for peers, but not parents. Although entirely speculative, given the nature of the sample (i.e. undergraduates) it could be that during this time period, peers are more germane to current affective states and therefore differences in associations may exist as a result. Despite this, the current findings are entirely correlational and it is unclear whether negative mood was a result of experiences of unsupportive interactions or whether mood states influenced participants’ perceptions of their social interactions.

The current findings regarding the CD38 polymorphism are somewhat paradoxical, but nonetheless speak to the challenges in delineating its role as a “risk” versus a “protective” allele. On the one hand, A carriers reported higher perceptions of peer unsupportive social interactions, which supports the perspective that this genotype is accompanied by elevated social sensitivity. On the other hand, the finding that higher negative affect was associated with higher perceived unsupportive social interactions among individuals with the CC genotype compared to A carriers is in line with the view that low oxytocin would be related to negative mood outcomes. Together, these findings demonstrate the complex nature of gene associations with environment and well-being. In this regard, the effects of certain genetic variants might vary depending on the context of the stressor experience, as well as in relation to the specific outcome measured.

In contrast to the moderating role of CD38 in the relation between perceived unsupportive social interactions from peers and negative mood, we did not observe that the OXTR polymorphism rs53576 moderated this association. However, there was a trend whereby A carriers displayed somewhat stronger relations between perceptions of peer unsupportive interactions and current negative affect. However, this finding did not withstand multiple comparisons correction. We previously reported that the A allele of the OXTR polymorphism rs53576 was associated with ineffective coping methods in relation to perceived unsupportive interactions, which was, in turn, linked to greater depressive symptoms compared to individuals homozygous for the G allele (McInnis et al., Citation2015). As well, other studies have observed that compared to individuals with the GG genotype, adolescents who carried an A allele for the OXTR polymorphism demonstrated a stronger relation between negative social experiences and loneliness (van Roekel et al., Citation2013). The observation that the OXTR polymorphism did not moderate the relation between unsupportive social interactions and negative mood could be due to type of mood outcomes assessed in the present study (i.e. current affective states vs measures that assess general well-being). As well, the current study controlled for several covariates and the interactions between these factors and the variables of interest, and utilizing this approach could also be accounting for the different findings observed in this study in comparison to other reports. Finally, given the trend toward a moderating effect of the OXTR it may be premature to discount its potential association entirely and replication in a larger sample would be ideal.

The findings of this study should be interpreted cautiously given that both the OXTR and CD38 polymorphisms are located on intronic regions, and their functionality remains unknown. It would have been ideal to examine levels of oxytocin in association with these genetic variants to determine if levels of oxytocin varied according to the SNPs as well as with the psychosocial measures examined. Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated previously that lower endogenous oxytocin levels accompanied the CC genotype of the CD38 polymorphism, suggesting that this SNP might be linked to a functional SNP on the CD38 gene (Lin et al., Citation2007). Alternatively, because the molecular structure of oxytocin and vasopressin is quite similar, it has been suggested that some of the effects linked to oxytocin may be due in part to oxytocin binding to vasopressin receptors (Leng & Ludwig, Citation2016). Some of the current findings are difficult to explain in that the CD38 polymorphism was associated with certain variables and not others (e.g. unsupportive interactions from peers and not parents, and negative affect and not positive affect). Previous reports have identified serious statistical concerns in Gene × Environment gene association studies. For example, effect sizes associated with certain genetic variants are typically very small (i.e. with odd ratios (OR) on the order of 1.1) (Dick et al., Citation2015). In the current study, a post hoc power analysis revealed that the minimum sample size required to detect an OR of 1.1 would be 11 904. Given this, the sample was significantly underpowered and these findings should be interpreted with caution.

The questionnaire used to assess mood states measured current emotions, and as such it is not possible to determine whether the emotional states were in any way the result of unsupportive social interactions. It is recognized that other proximal factors such as food intake, sleep and daily stress might contribute to current mood states. Ideally, the current study would have controlled for such measures. As well, factors that might influence the oxytocin system and thus could have impacted the gene associations observed were not assessed in the current study (e.g. estradiol, menstrual cycle phase etc.). Finally, in the present investigation the number of females was markedly greater than the number of males, and as such gender was controlled for in analyses. In our studies with university students (e.g. McQuaid et al., Citation2013, Citation2015; McInnis et al., Citation2015) this skewed distribution was commonly observed, possibly because of the greater number of females enrolled in an Introductory Psychology course, and/or females were more disposed to volunteering in experiments. Regardless of the source, it would be advantageous to be able to assess the relations between oxytocin polymorphisms and behavioral responses, particularly as there is reason to suppose that oxytocin might not have identical effects in the two sexes. In females, for instance, oxytocin may contribute to tend-and-befriend characteristics (Taylor et al., Citation2000), whereas in males, it has been observed that oxytocin promotes a tend-and-defend behavioral response, although it is uncertain whether this is also present in females (De Dreu et al., Citation2010).

Conclusions

The present findings are in line with two different, but not necessarily competing, perspectives regarding oxytocin-related polymorphisms and social experiences. The observation that a genetic variant speculated to be linked to lower oxytocin functioning was associated with poor mood which was tied to perceived negative social interactions is consistent with the view that oxytocin is linked to prosocial behaviors that, in turn, limit negative affect. Yet, individuals who presumably have higher oxytocin (A carriers of the CD38 polymorphism) also reported greater perceptions of negative social interactions, which is in line with the perspective that elevated oxytocin increases sensitivity to social cues, irrespective of whether these are positive (Bradley et al., Citation2013) or negative (Bradley et al., Citation2011; Hostinar et al., Citation2014; McQuaid et al., Citation2013). While individuals with higher oxytocin might be more socially sensitive, the possibility remains that they are also more likely to engage in advantageous coping involving social support seeking, which could limit the extent of negative mood outcomes. Moreover, the current study was based on normal conditions, and hence does not provide information concerning the influence of the polymorphisms in the presence versus absence of a challenge. Ultimately, closely examining the context under which certain genetic variants are assessed is key for delineating if, or to what extent, they might impact well-being.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) under grant MOP −106591. H.A. holds a Canadian Research Chair in Neuroscience. R.J.M. is supported by the CIHR Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship. The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of scientists and staff of the McGill University and Génome Québec Innovation Center, Montréal, Canada for genotyping.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Algoe SB, Way BM. (2014). Evidence for a role of the oxytocin system, indexed by genetic variation in CD38, in the social bonding effects of expressed gratitude. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 9:1855–61.

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. (2014). A sociability gene? Meta − analysis of oxytocin receptor genotype effects in humans. Psychiatr Genet 24:45–51.

- Bartz JA, Zaki J, Bolger N, Ochsner KN. (2011). Social effects of oxytocin in humans: context and person matter. Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.) 15:301–9.

- Belsky J, Pluess M. (2009). Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychol Bull 135:885–908.

- Belsky J, Jonassaint C, Pluess M, Stanton M, Brummett B, Williams R. (2009). Vulnerability genes or plasticity genes?. Mol Psychiatry 14:746–54.

- Bradley B, Davis TA, Wingo AP, Mercer KB, Ressler KJ. (2013). Family environment and adult resilience: contributions of positive parenting and the oxytocin receptor gene. Eur J Psychotraumatol 4:21659. eCollection.

- Bradley B, Westen D, Mercer KB, Binder EB, Jovanovic T, Crain D, Wingo A, Heim C. (2011). Association between childhood maltreatment and adult emotional dysregulation in a low-income, urban, African American sample: moderation by oxytocin receptor gene. Dev Psychopathol 23:439–52.

- De Dreu CK, Greer LL, Handgraaf MJ, Shalvi S, Van Kleef GA, Baas M, Ten Velden FS, et al. (2010). The neuropeptide oxytocin regulates parochial altruism in intergroup conflict among humans. Science 328:1408–11.

- Dick DM, Agrawal A, Keller MC, Adkins A, Aliev F, Monroe S, Hewitt JK, et al. (2015). Candidate gene–environment interaction research reflections and recommendations. Persp Psychol Science 10:37–59.

- Feldman R. (2012). Oxytocin and social affiliation in humans. Horm Behav 61:380–91.

- Feldman R, Zagoory-Sharon O, Weisman O, Schneiderman I, Gordon I, Maoz R, Shalev I, Ebstein RP. (2012). Sensitive parenting is associated with plasma oxytocin and polymorphisms in the OXTR and CD38 genes. Biol Psychiatry 72:175–81.

- Feng C, Lori A, Waldman ID, Binder EB, Haroon E, Rilling JK. (2015). A common oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) polymorphism modulates intranasal oxytocin effects on the neural response to social cooperation in humans. Genes, Brain Behav 14:516–25.

- Haram M, Tesli M, Bettella F, Djurovic S, Andreassen OA, Melle I. (2015). Association between genetic variation in the oxytocin receptor gene and emotional withdrawal, but not between oxytocin pathway genes and diagnosis in psychotic disorders. Front Hum Neurosci 9:Article number 9. eCollection.

- Heinrichs M, Baumgartner T, Kirschbaum C, Ehlert U. (2003). Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biol Psychiatry 54:1389–98.

- Higashida H, Yokoyama S, Kikuchi M, Munesue T. (2012). CD38 and its role in oxytocin secretion and social behavior. Horm Behav 61:351–8.

- Hostinar CE, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. (2014). Oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism, perceived social support, and psychological symptoms in maltreated adolescents. Dev Psychopathol 26:465–77.

- Ingram KM, Betz NE, Mindes EJ, Schmitt MM, Smith NG. (2001). Unsupportive responses from others concerning a stressful life event: development of the unsupportive social interactions inventory. J Soc Clin Psychol 20:173–207.

- Ingram KM, Jones DA, Fass RJ, Neidig JL, Song YS. (1999). Social support and unsupportive social interactions: their association with depression among people living with HIV. AIDS Care 11:313–29.

- Inoue T, Kimura T, Azuma C, Inazawa J, Takemura M, Kikuchi T, Kubota Y, et al. (1994). Structural organization of the human oxytocin receptor gene. J Biol Chem 269:32451–6.

- Jin D, Liu HX, Hirai H, Torashima T, Nagai T, Lopatina OS, …Higashida H. (2007). CD38 is critical for social behaviour by regulating oxytocin secretion. Nature 446:41–5.

- Keller MC. (2014). Gene × environment interaction studies have not properly controlled for potential confounders: the problem and the (simple) solution. Biol Psych 75:18–24.

- Kim HS, Sherman DK, Sasaki JY, Xu J, Chu TQ, Ryu C, Suh EM, et al. (2010). Culture, distress, and oxytocin receptor polymorphism (OXTR) interact to influence emotional support seeking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:15717–21.

- Kiss I, Levy − Gigi E, Kéri S. (2011). CD 38 expression, attachment style and habituation of arousal in relation to trust-related oxytocin release. Biol Psychol 88:223–6.

- Krueger F, Parasuraman R, Iyengar V, Thornburg M, Weel J, Lin M, Clarke E, et al. (2012). Oxytocin receptor genetic variation promotes human trust behavior. Front Hum Neurosci 6:Article number 4. eCollection.

- Leng G, Ludwig M. (2016). Intranasal oxytocin: myths and delusions. Biol Psychiatry 79:243–50.

- Lerer E, Levi S, Israel S, Yaari M, Nemanov L, Mankuta D, Nurit Y, Ebstein RP. (2010). Low CD38 expression in lymphoblastoid cells and haplotypes are both associated with autism in a familybased study. Autism Res 3:293–302.

- Lin PI, Vance JM, Pericak − Vance MA, Martin ER. (2007). No gene is an island: the flip-flop phenomenon. Am J Hum Genet 80:531–8.

- Lucht MJ, Barnow S, Sonnenfeld C, Rosenberger A, Grabe HJ, Schroeder W, Völzke H, et al. (2009). Associations between the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) and affect, loneliness and intelligence in normal subjects. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 33:860–6.

- Malavasi F, Deaglio S, Funaro A, Ferrero E, Horenstein AL, Ortolan E, Vaisitti T, Aydin S. (2008). Evolution and function of the ADP ribosyl cyclase/CD38 gene family in physiology and pathology. Physiol Rev 88:841–86.

- Mcinnis OA, McQuaid RJ, Matheson K, Anisman H. (2015). The moderating role of an oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism in the relation between unsupportive social interactions and coping profiles: implications for depression. Front Psychol 6:1133.

- McQuaid RJ, McInnis OA, Abizaid A, Anisman H. (2014). Making room for oxytocin in understanding depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 45:305–22.

- McQuaid RJ, McInnis OA, Matheson K, Anisman H. (2015). Distress of ostracism: oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism confers sensitivity to social exclusion. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 10:1153–9.

- McQuaid RJ, McInnis OA, Matheson K, Anisman H. (2016). Oxytocin and social sensitivity: gene polymorphisms in relation to depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. Front Human Neurosci 10:Article number 358.

- McQuaid RJ, McInnis OA, Stead JD, Matheson K, Anisman H. (2013). A paradoxical association of an oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism: early-life adversity and vulnerability to depression. Front Neurosci 7:Article number 128.

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J Educ Behav Stat 31:437–48.

- Rodrigues SM, Saslow LR, Garcia N, John OP, Keltner D. (2009). Oxytocin receptor genetic variation relates to empathy and stress reactivity in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:21437–41.

- Saphire − Bernstein S, Way BM, Kim HS, Sherman DK, Taylor SE. (2011). Oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) is related to psychological resources. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:15118–22.

- Sauer C, Montag C, Wörner C, Kirsch P, Reuter M. (2012). Effects of a common variant in the CD38 gene on social processing in an oxytocin challenge study: possible links to autism. Neuropsychopharmacology 37:1474–82.

- Song YS, Ingram KM. (2002). Unsupportive social interactions, availability of social support, and coping: their relationship to mood disturbance among African Americans living with HIV. J Soc Pers Relat 19:67–85.

- Tabak BA, Vrshek − Schallhorn S, Zinbarg RE, Prenoveau JM, Mineka S, Redei EE, Adam EK, Craske MG. (2016). Interaction of CD38 variant and chronic interpersonal stress prospectively predicts social anxiety and depression symptoms over 6 years. Clin Psychol Sci 4:17–27.

- Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, Gruenewald TL, Gurung RA, Updegraff JA. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychol Rev 107:411–29.

- Tost H, Kolachana B, Hakimi S, Lemaitre H, Verchinski BA, Mattay VS, Weinberger DR, Meyer–Lindenberg A. (2010). A common allele in the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) impacts prosocial temperament and human hypothalamic-limbic structure and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:13936–41.

- Vaht M, Kurrikoff T, Laas K, Veidebaum T, Harro J. (2016). Oxytocin receptor gene variation rs53576 and alcohol abuse in a longitudinal population representative study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 74:333–41.

- van Roekel E, Verhagen M, Scholte RH, Kleinjan M, Goossens L, Engels RC. (2013). The oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) in relation to state levels of loneliness in adolescence: evidence for micro-level gene-environment interactions. PLoS One 8:e77689.

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 54:1063–70.