Abstract

Despite well-established evidence on marriage as a psychosocial support for adults, there are studies that indicate loneliness may affect even married adults. Loneliness provokes a dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis. Thus, the study aims to examine the sex-specific association of loneliness and cortisol levels in the married older population. A cross-sectional analysis was conducted among 500 married participants (316 male and 184 female) aged 65–90 years (mean age = 73.8 ± 6.4 years) of the population-based KORA (Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg) – Age study. Linear regression analyses were employed to examine the association between cortisol measurements (salivary cortisol upon waking (M1), 30 min after awakening (M2), late night (LNSC), cortisol awakening response (CAR), diurnal cortisol slope (DCS)) and loneliness (assessed by UCLA Loneliness Scale) in married participants with adjustments for potential confounders. In total sample population, lonely married participants displayed a significantly flatter DCS after M2 peak than their not lonely counterparts. In sex-specific analyses, lonely married men showed flatter DCS and reduced CAR than non-lonely counterparts. The association between loneliness and DCS was robust even after adjustment for lifestyle and psychosocial factors. In married women, no significant associations between loneliness and cortisol levels were observed. These findings suggest a differential impact of loneliness on HPA axis dynamics in lonely married men. Our findings highlight the importance to address loneliness even in married people.

Keywords:

Introduction

A large body of literature implicated that married people are generally healthier than unmarried people (Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, Citation2017). Many studies have shown that marriage is associated with well-being, life satisfaction, and lower depression and anxiety (Akhtar-Danesh & Landeen, Citation2007; Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, Citation2017), lower risk of various health impairments including heart disease (Eaker et al., Citation2007) as well as mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2015). Notwithstanding, marriage can be a source of psychological stress. Eaker et al. showed that marital conflict and strain were associated with adverse health outcomes in a population-based longitudinal study (Eaker et al., Citation2007). In women, “self-silencing” during conflict with their spouse was associated with fourfold increased risk in mortality. Of note, people can even experience loneliness despite being married, especially in old age (Perissinotto et al., Citation2012). The experience of loneliness within marriage has been associated with the quality of the relationship (Dykstra et al., Citation2005) making loneliness a crucial indicator of poor marital quality. Further evidence indicates that men in old age tend to experience loneliness with stronger associations to adverse mental health conditions than women (Zebhauser et al., Citation2014). Given that marital role expectations and the structure of social relations broadly differ between men and women at old age (Moen, Citation2001), gender is a core feature that may influence the associations between marriage and loneliness.

Among various underlying biological mechanisms accounting for the association of marital status and health, the HPA axis has gained utmost attention. Chin et al. found that being married in comparison to single was associated with a steeper daily decline in cortisol slopes (Chin et al., Citation2017). There are also several small-sized clinical studies among young married couples that have investigated the association of poor marital quality and diurnal cortisol slopes (DCSs) but yielded conflicting evidence (Robles et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, none of previous work has focused on older population as well as considered loneliness as a proxy of marriage quality. Therefore, in the present investigation, we tested cortisol levels assessed at multiple time points to evaluate diurnal cortisol secretion patterns by using data from a large representative sample of community-dwelling older adults.

To date, it is still unclear whether the phenomenon of being lonely in a marriage is a potential stress cue among older adults with no study examining the sex difference. Kudielka and Kirschbaum have evidence greater cortisol responses to acute psychological stress in men compared to women (Kudielka & Kirschbaum, Citation2005), providing a valid argument to investigate sex dimorphisms of the relationship between loneliness and cortisol secretion patterns. Thus, this study aims to assess sex-specific associations of loneliness and diurnal cortisol patterns in a representative sample of old aged married population with adjustment for potential confounders. We anticipate that loneliness may alter the association between cortisol secretion patterns and marital relationship in older adults, especially in men.

Methods

Sample and participant selection

The KORA (Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg)-Age study is a follow up examination of the participants (N = 4127, age ≥ 64 years) of previous four cross-sectional MONICA/KORA Surveys in the Augsburg region, Southern Germany and was conducted between November 2008 and November 2009 (Peters et al., Citation2011). From these participants, a randomly drawn subsample of 1079 participants participated in a standardized telephone interview and extensive physical examinations at the study center including collection of blood samples, anthropometric examination, and personal interview.

The present study has excluded unmarried participants (n = 267) and missing data in UCLA Loneliness Score (n = 57), salivary cortisol samples (morning after awakening, M1: n = 292; 30 minutes after awakening, M2: n = 292; late night salivary cortisol, LNSC = 287) and depressive symptoms (n = 61) as well as an outlier from LNSC sample (n = 1). Salivary samples were available from 772 subjects (saliva sampling rate of 72%), as previously described (Johar et al., Citation2016). Therefore, the final dataset for the present analysis consisted of 500 participants (316 male and 184 female) aged 65–90 years (mean age = 73.8 ± 6.4 years). A drop-out analysis of the excluded participants revealed no significant age and sex differences. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Bavarian Medical Association, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Outcome variable

Cortisol measurements

Participants were individually instructed about the saliva sampling procedure and provided with additional detailed written information (Salivette® salivary sampling test kit, Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). At home, participants collected three saliva samples: in the morning after awakening (M1) while sitting in an upright position, 30 min after awakening (M2), and in the late night before bedtime. Participants were instructed not to eat or drink or brush their teeth 15 min before collecting the salivary samples. We did not enforce a specific day for sampling but instructed the study participants to provide the salivary samples all on the same day to reflect normal daily settings, on a day with a normal daily routine that should not involve any special occasions, such as family celebration, travel, or a doctor’s visit. Otherwise, the saliva collection should be postponed to other days. Analysis of self-documented collection times revealed that 95% of the subjects had collected the second morning (M2) sample with less than five minutes deviation from the expected time point. Cortisol levels (ng/mL) were determined in duplicate using a luminescence immunoassay (IBL, Hamburg, Germany). The lower detection limit of this assay is 0.1 ng/mL (0.276 nmol/L), intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) are below 6% and 9% at concentrations of 0.4 ng/mL and 5.0 ng/mL, respectively.

The normal HPA axis diurnal rhythm consists of high morning and low evening cortisol levels. Therefore, we have calculated overall DCS (ratio of M1/LNSC) and also DCS after M2 peak (ratio of M2/LNSC) in the current analysis (). Lower DCS values indicate flattened DCS patterns. As cortisol awakening response (CAR) is regulated by different neurobiological mechanisms than the rest of the underlying diurnal cortisol patterns (Clow et al., Citation2004), we calculated CAR based on the difference of M2 to M1 as done by other studies (Adam and Kumari, Citation2009; Kunz-Ebrecht et al., Citation2004) and the area under the curve with respect to ground (AUCG) was calculated from M1 to M2, as suggested previously (Pruessner et al., Citation2003).

Covariates measurements

Information on covariates was obtained in standardized personal interviews conducted by trained medical staff and a self-administered questionnaire as described elsewhere in detail (Lacruz et al., Citation2010).

Main covariate (independent variable)

Loneliness was measured by using a short German version of the UCLA-Loneliness-Scale (Bilsky & Hosser, Citation1998) containing 12 items and leading to a score that ranges from 0 to 36 points; high score points indicate severe loneliness. We used the continuous UCLA Loneliness Scale for the main analysis. As indicated by previous studies, the prevalence of loneliness in the general population is about 20% (Theeke, Citation2009; Victor & Bowling, Citation2012). Based on the assumptions that 20% of our study population could be considered as being lonely, the 80th percentile was chosen as the cutoff point. A dichotomized loneliness (yes/no) variable was created by cutoff ≥21 points, as also performed previously (Zebhauser et al., Citation2014).

Other covariates

Marital status and living arrangements were assessed via interview and dichotomized as married or living in partnership vs. unmarried which includes single, separated, divorced and widowed. Low education was defined as <12 years of schooling. Someone who smoked cigarettes regularly or occasionally was considered as a current smoker. Alcohol consumption was rated as “daily”, “once or several times a week”, and “no”. To assess physical activity, participants were classified as “active” during leisure time if they regularly participated in sports for at least one hour per week; otherwise, they were considered “inactive”. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height2 (m2), which was assessed in a medical examination. T2DM was self-reported by the participants in the self-administered questionnaire and verified from physicians and antidiabetic medications used by the study participants. Actual hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg and/or current use of hypertensive medication. Total cholesterol (TC) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) in mmol/l were measured by enzymatic methods (CHOD-PAP, Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). Multimorbidity was defined as the co-occurrence of more than two disease conditions based on the Charlson Comorbidity Index (Chaudhry et al., Citation2005).

Sleeping problems were assessed based on interview questions using the Uppsala Sleep Inventory (USI) concerning the difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep, as well as sleeping duration (Mallon & Hetta, Citation1997). Depressive symptoms were measured by cutoff point >5 for mild or moderate depression using the 15-item German version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (Sheikh & Yesavage, Citation1985) and anxiety (scores ≥10) using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (Spitzer et al., Citation2006). Stressful life event in the past year and levels of perceived stress (if the subjects suffer from a past stressful event) with answers ranging from “quite”, “very much”, “a little”, or “no” were assessed by questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data of sociodemographic, lifestyle, clinical and psychosomatic characteristics were stratified by marital status as shown in . Bivariate associations of continuous variables and marital status groups were tested using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The χ2 test was used to examine the associations between categorical variables. Regarding mean of cortisol measurements, age- and sex-adjusted least-square (LS) means (95% confidence intervals) were calculated.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants by loneliness status, means (±standard deviation) and N (%) (N = 500).

Multiple linear regression was employed to explore the association of cortisol levels and a continuous loneliness score with different steps of adjustments. Beta (β) estimate, standard error, and p values are shown for the association between marital status and different cortisol measurements. CAR, LNSC, and DCS after M2 peak were chosen as dependent variables. Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex. Model 2 was additionally adjusted for education level and BMI. Model 3 included depressed mood in the previous model 2. The final model 4 added the time of awakening to model 3. Adjustment for regular smoking, alcohol intake, stress resilience, and sleep problems did not substantially alter the estimates; thus, the present analysis included only the aforementioned factors as confounders. Diagnostic plots of the fitted models (Q–Q-plots and plots of standardized residuals vs. the fitted linear predictor portion of the models) visually confirmed that residuals of cortisol measurements to approximate normality. However, the plot of residual vs. predicted value suggests potential outliers and probable heteroscedasticity in the LNSC sample. However, the DFBETAS statistics revealed that the outliers did not influence the parameter's coefficient. The removal of two detected outliers of LNSC left the significant findings unchanged.

We further examined the interaction between loneliness and sex on cortisol levels by including the product of both variables (continuous UCLA loneliness score × sex) in linear regression models with cortisol levels as the dependent variable. Then, sex-stratified analyses were performed on married participants according to their loneliness status (lonely vs. not lonely), and differences between groups were tested with generalized linear model (GLM) procedures with a similar confounder-adjustment strategy. Finally, sex-specific age-adjusted least-squares means (LS-means) and 95% confidence intervals of cortisol measurements were calculated using GLMs as described above in a specific assessment of loneliness (lonely vs. not lonely) in the married individuals.

Results

Description of study population

Among the 500 married participants (316 men, 63.2%; 184 women, 36.8%) with a mean age of 73.8 (SD± = 5.8) (range 65–89) years, a total of 75 (15.0%) participants were identified as lonely by the UCLA Loneliness Scale. Overall, the mean loneliness score did not differ between men and women (16.7 ± 4.2 vs. 16.3 ± 4.2); the frequency of loneliness in the married population was 15.8% (N = 50) in men and 13.6% (N = 25) in women.

As can be seen in , in the total sample population, lonely married participants were more likely to be older, be affected by multimorbidity, and suffer more from various psychological conditions including depression, anxiety, sleep problems, perceived stress, low social network, low life satisfaction, and low resilience in comparison to their not lonely married counterparts. There were sex difference observed in the univariate analysis whereby men (not women) tended to suffer more from sleep problems, perceived stress, low social network, and low resilience.

Association of loneliness and cortisol secretion patterns

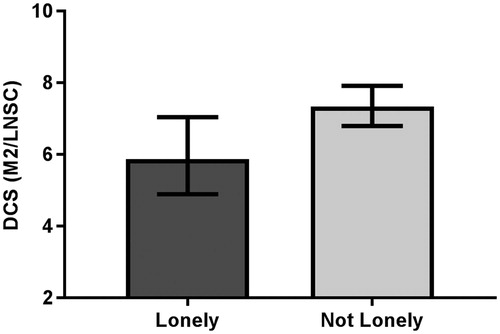

In the total sample population, lonely married participants presented a significantly lower DCS after the M2 peak than not lonely married counterparts (DCS after M2 peak, lonely: 5.86, 4.89–7.04; not lonely: 7.34, 6.80–7.92, p = .03). Multiple linear regression analyses revealed that loneliness was associated with a flatter DCS even after adjustments for important confounders (model 4, overall DCS: β = −0.19, SE = 0.07, p = .01; DCS after M2 peak: β = −0.21, SE = 0.08, p = .01) (). All other cortisol measurements (M1, CAR, and LNSC) were not significantly associated with loneliness in married participants (p>.05).

Sex-specific association of loneliness and cortisol secretion patterns in married participants

We then performed a sex-specific analysis to examine the association between loneliness and cortisol levels. As shown in , the M1 sample was not associated with being lonely while lonely men displayed a significantly lower CAR and flatter DCS after the M2 peak (lower M2/LNSC ratio) compared to non-lonely men. Driven by this finding, we further employed sex-specific regression analyses and found that loneliness was associated with flatter DCS patterns even in the fully adjusted regression models, as shown in (model 4: overall DCS: β = −0.26, SE = 0.10, p = .008; DCS after M2 peak: β = −0.24, SE = 0.12, p = .04) in men. The association of loneliness and flatter DCS (measured by overall DCS) in men remained significant after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was applied (0.05/3, p<.017). However, the association of loneliness and CAR measurement was no longer significant after further adjustment for education, BMI and depression and time of awakening in the linear regression models. Loneliness was not significantly associated with other cortisol measurements (M1, LNSC, and overall DCS) in men (p>.05). Remarkably in women, loneliness was not associated with any cortisol measurement (M1, CAR, LNSC, overall DCS, and DCS after M2 peak).

Table 2. Age-adjusted means (95% CI) and p Value for the association of loneliness (lonely vs. not lonely) with cortisol measurements in married participants (nmol/L) (N = 500).

Table 3. Association of loneliness (in continuous scores) with cortisol measurements: β estimate, standard error (SE) and p value of the married KORA Age study participants (N = 500).

Given the substantial difference in HPA axis dynamic between men and women, we aimed to identify factors which may explain these differences. However, bivariate analyses revealed no significant difference between lifestyle, cardio-metabolic and psychological factors except for lonely men tend to report more sleep problems and had lower stress resilience compared with their not lonely women counterparts.

However, the statistical interaction between sex and UCLA loneliness score (continuous values) on cortisol levels were not significant in both crude and fully adjusted models.

Discussion

Despite sociodemographic shifts away from marriage in industrialized countries, marriage continues to play an integral role in social networks (Robles et al., Citation2014; Treas et al., Citation2014). Evidence indicates that married individuals are healthier than their counterparts. Chin et al. (Citation2017) proposed that elevated levels of cortisol, a potential biological consequence of interpersonal stress, could be most likely a major candidate mechanism accounting for the association of marital status and health. Therefore, the researchers examined the association between currently married vs. non-married with cortisol secretion patterns and a possible disruption of cortisol’s daily rhythm in 572 healthy men and women aged 21–55 years and confirmed that married individuals had lower cortisol levels than their never married or previously married counterparts. Furthermore, they observed a more rapid decline in cortisol through the afternoon in married subjects. The authors did not consider marriage quality because they expected most married people to be relatively satisfied with their marriage.

Contrary to this assumption, in a sample of 500 community dwelling older individuals, we identified a proportion of 15% who reported being lonely despite currently married, indicating that they perceived an imbalance between their social needs and the quality of their marital relationships (Hawkley & Cacioppo, Citation2010). Of note, these lonely married individuals clustered further somatic and mental health adversities (including multimorbidity, depression, anxiety, and sleep problems). Furthermore, data from the present investigation demonstrated an association of dysregulated cortisol secretion patterns and sustained feelings of loneliness in a sample of married older men and women. We applied similar measures of HPA-axis disruption as in the study of Chin et al. Here, we show that in married participants, loneliness was associated with a lower CAR secretion particularly in men, which in turn contributed to a significantly flatter diurnal slope. Interestingly, these findings were not confirmed for women.

Some attempts have been made to study the impact of “marital quality” on cortisol slopes and reactivity, however, a meta-analysis by Robles et al. (Citation2014) concluded that the small number of studies with low sample sizes caused significant heterogeneity and precluded examining moderators (Robles et al., Citation2014). No study included in the meta-analysis investigated older community dwelling individuals or focused on loneliness. Recently, Schutter et al. (Citation2017) analyzed the association between loneliness and morning cortisol, CAR, diurnal slope, and dexamethasone suppression ratio in cross-sectional data of 426 lonely and non-lonely older adults in the Netherlands Study of Depression in Older Persons (NESDO) (Schutter et al., Citation2017). In line with the present investigation, they found that cortisol output in the first hour after awakening and dexamethasone suppression ratio was lower in lonely participants. There were no significant interactions between loneliness and depression diagnosis in the association with the cortisol measures. No attempts were made to elaborate the effect of loneliness in married people. Furthermore, several studies have investigated the effects of loneliness on stress responses in a laboratory setting among healthy adults and yielded mixed findings (Edwards et al., Citation2010; Hackett et al., Citation2012; Jaremka et al., Citation2013; Steptoe et al., Citation2004). However, the largest of these studies with a sample of 524 healthy individuals confirmed that loneliness was associated with reduced stress responsivity (Hackett et al., Citation2012). Taken together, preliminary findings in the literature and results from the present investigation support the assumption that a disrupted HPA axis response pattern in lonely people is characterized by a blunted and not by a hyperactive reagibility (Phillips et al., Citation2013).

In the present study, the sex-specific findings showed that the detrimental effect of loneliness was most profound in married men and was not substantially affected by adjustment for lifestyle and psychosocial factors. These sex-specific results are supported by findings from Doane and Adam whereby younger male had a lower CAR and flatter DCS than their female counterparts (Doane & Adam, Citation2010). Furthermore, blunted cortisol secretion patterns leading to a flatter diurnal rhythm has been implicated in various psychological conditions (Adam et al., Citation2017; Pan et al., Citation2018), immune and inflammatory disorders (Heim et al., Citation2000). However, two small-sized studies provided contradicting evidence for gender differences, showing that the impact of low marital quality and DCS was stronger for women compared to men (Borys & Perlman, Citation1985; Fehm-Wolfsdorf et al., Citation1999). Apparently, women are more prone to acknowledge their loneliness, but they do not necessarily suffer severely from loneliness (Borys & Perlman, Citation1985), whereas men tend to experience loneliness with more robust consequences on HPA axis dynamics as well as stronger associations to adverse psychological conditions than female counterparts (Zebhauser et al., Citation2014). Therefore, our results support the idea that men in old age experience higher levels of social loneliness (Dykstra & Fokkema, Citation2007).

Strengths and limitations

The present study collected salivary and serum cortisol measures from a large sample of older community dwelling of men and women with a high response rate and a rigorous and quality assessment. The dataset allows for a robust adjustment for a set of covariates. The study is limited due to the saliva sample collection on one single day. We observed an individual variability in the time of awakening, but 90.4% of the subjects collected the first sample in the early morning after awakening and 95% of the subjects had collected the second sample with less than 5 min deviation from the expected time point (30 minutes after the first sample). Another limitation of this study is that, we do not have additional data on marital quality and years of marriage. The sex-specific results, however, should be interpreted with caution because of the non-significant interaction between loneliness and sex in the analytic sample. Lastly, we recognize that the cross-sectional nature of the study does not imply a cause and effect relationship.

Conclusions

The present investigation shows that a clinical relevant minority of about 15% of older individuals of both sexes suffer from loneliness while being married. Loneliness in marriage may reflect a more silent form of impaired marriage quality, which is most likely more prevalent in old age than predominantly negative attitudes toward one’s partner along with high levels of hostile and negative behavior. Loneliness in these people activates sustained psycho-biological traces of a blunted stress dynamic in the diurnal cortisol secretion pattern which may reflect a diminished and burnt-out capacity to react on daily challenges. Insufficient HPA axis signaling may lead to increased inflammatory responses, and ultimately a higher mortality risk in men (Hermes et al., Citation2006). To date, recent studies have established the sex differences in outcomes with lower morning responses and flatter DCS exclusively in men, but the associations are still poorly understood and require further investigations. Public health interventions show that the prevalence of loneliness can be reduced by offering adequate assessment and support in older people (Poscia et al., Citation2018); however, we recommend that those who are married should not been overlooked.

Author contributions

KHL and MB designed the study. HJ managed the literature searches, statistical analysis, and wrote the first draft. HJ, SA, MB, PH, and KHL wrote and proofread the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the commitment of the study participants and for the work of the MONICA/KORA Augsburg Study staff especially Ina Fabricius and Gerlinde Trischler for the technical assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

For approved reasons, access restrictions apply to the data underlying the findings. The informed consent given by KORA study participants does not cover data posting in public databases. However, data are available upon request by means of a project agreement. Requests should be sent to [email protected] and are subject to approval by the KORA Board.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hamimatunnisa Johar

Hamimatunnisa Johar is an epidemiologist and postdoctoral researcher at the Mental Health Research Unit, Institute of Epidemiology, Helmholtz Zentrum München. Her main research focus is the psychobiological mechanisms linking stress to metabolic diseases.

Seryan Atasoy

Seryan Atasoy is a clinical psychologist and epidemiologist currently undertaking postdoctoral research at the Helmholtz Zentrum München. As part of the mental health epidemiology group, her research focus is on the associations between psychosocial risk factors and chronic disease conditions, such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Martin Bidlingmaier

Martin Bidlingmaier is an endocrinologist, currently works at the Faculty of Medicine, Ludwig-Maximilians-University of Munich. He does clinical and basic research in Endocrinology and Diabetology. His focus is on the development and validation of laboratory methods to diagnose and monitor pituitary and adrenal diseases.

Peter Henningsen

Peter Henningsen is a Professor and Head, Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, University Hospital, Technical University of Munich (TUM). Specialist in Psychosomatic Medicine, Neurology and Psychiatry. Dean of Faculty of Medicine of TUM 2010-19. Primary research Interest in epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of functional somatic disorders.

Karl-Heinz Ladwig

Karl-Heinz Ladwig is a senior lecturer in the Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, Technical Unversity of Munich (TUM) and head of the Mental Health Research Unit in the Institute of Epidemiology, Helmholtz Zentrum München (HMGU). His major research topics focus on epidemiological and clinical stress research in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.

References

- Adam, E. K., & Kumari, M. (2009). Assessing salivary cortisol in large-scale, epidemiological research. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(10), 1423–1436.10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.011

- Adam, E. K., Quinn, M. E., Tavernier, R., McQuillan, M. T., Dahlke, K. A., & Gilbert, K. E. (2017). Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 83, 25–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.05.018

- Akhtar-Danesh, N., & Landeen, J. (2007). Relation between depression and sociodemographic factors. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 1(1), 4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-1-4

- Bilsky, W., & Hosser, D. (1998). Soziale Unterstützung und Einsamkeit: Psychometrischer Vergleich zweier Skalen auf der Basis einer bundesweiten Repräsentativbefragung [Social support and loneliness: Psychometric comparison of two scales based on a nationwide representative survey]. Zeitschrift Für Differentielle Und Diagnostische Psychologie, 19(2), 131–145.

- Borys, S., & Perlman, D. (1985). Gender differences in loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 11(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167285111006

- Chaudhry, S., Jin, L., & Meltzer, D. (2005). Use of a self-report-generated Charlson Comorbidity Index for predicting mortality. Medical Care 43(6), 607–615. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000163658.65008.ec

- Chin, B., Murphy, M. L. M., Janicki-Deverts, D., & Cohen, S. (2017). Marital status as a predictor of diurnal salivary cortisol levels and slopes in a community sample of healthy adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 78, 68–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.01.016

- Clow, A., Thorn, L., Evans, P., & Hucklebridge, F. (2004). The awakening cortisol response: Methodological issues and significance. Stress, 7(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890410001667205

- Doane, L. D., & Adam, E. K. (2010). Loneliness and cortisol: Momentary, day-to-day, and trait associations. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35(3), 430–441. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.005

- Dykstra, P. A., & Fokkema, T. J. B. (2007). Social and emotional loneliness among divorced and married men and women: Comparing the deficit and cognitive perspectives. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01973530701330843

- Dykstra, P. A., van Tilburg, T. G., & Gierveld, J. d. J. (2005). Changes in older adult loneliness: Results from a seven-year longitudinal study. Research on Aging, 27(6), 725–747. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027505279712

- Eaker, E. D., Sullivan, L. M., Kelly-Hayes, M., D’Agostino, R. B. S., & Benjamin, E. J. (2007). Marital status, marital strain, and risk of coronary heart disease or total mortality: The Framingham Offspring Study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69(6), 509–513. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180f62357

- Edwards, K. M., Bosch, J. A., Engeland, C. G., Cacioppo, J. T., & Marucha, P. T. (2010). Elevated macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is associated with depressive symptoms, blunted cortisol reactivity to acute stress, and lowered morning cortisol. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 24(7), 1202–1208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2010.03.011

- Fehm-Wolfsdorf, G., Groth, T., Kaiser, A., & Hahlweg, K. (1999). Cortisol responses to marital conflict depend on marital interaction quality. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 6(3), 207–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm0603_1

- Hackett, R. A., Hamer, M., Endrighi, R., Brydon, L., & Steptoe, A. (2012). Loneliness and stress-related inflammatory and neuroendocrine responses in older men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(11), 1801–1809. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.03.016

- Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

- Heim, C., Ehlert, U., & Hellhammer, D. H. (2000). The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of stress-related bodily disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 25(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(99)00035-9

- Hermes, G. L., Rosenthal, L., Montag, A., & McClintock, M. K. (2006). Social isolation and the inflammatory response: Sex differences in the enduring effects of a prior stressor. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 290(2), R273–R282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00368.2005

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

- Jaremka, L. M., Fagundes, C. P., Peng, J., Bennett, J. M., Glaser, R., Malarkey, W. B., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2013). Loneliness promotes inflammation during acute stress. Psychological Science, 24(7), 1089–1097. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612464059

- Johar, H., Emeny, R. T., Bidlingmaier, M., Kruse, J., & Ladwig, K.-H. (2016). Sex-related differences in the association of salivary cortisol levels and type 2 diabetes. Findings from the cross-sectional population based KORA-age study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 69, 133–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.04.004

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., & Wilson, S. J. (2017). Lovesick: How couples' relationships influence health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13(1), 421–443. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045111

- Kudielka, B. M., & Kirschbaum, C. (2005). Sex differences in HPA axis responses to stress: A review. Biological Psychology, 69(1), 113–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.11.009

- Kunz-Ebrecht, S. R., Kirschbaum, C., Marmot, M., & Steptoe, A. (2004). Differences in cortisol awakening response on work days and weekends in women and men from the Whitehall II cohort. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(4), 516–528.10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00072-6

- Lacruz, M. E., Emeny, R. T., Bickel, H., Cramer, B., Kurz, A., Bidlingmaier, M., Ladwig, K. H. (2010). Mental health in the aged: Prevalence, covariates and related neuroendocrine, cardiovascular and inflammatory factors of successful aging. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 10, 36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-10-36

- Mallon, L., & Hetta, J. (1997). A survey of sleep habits and sleeping difficulties in an elderly Swedish population. Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences, 102(3), 185–197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/03009739709178940

- Moen, P. (2001). The gendered life course. In R. H. Binstock & L. K. George (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the social sciences (5th ed., pp. 179–196). Academic Press.

- Pan, X., Wang, Z., Wu, X., Wen, S. W., & Liu, A. (2018). Salivary cortisol in post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 324. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1910-9

- Perissinotto, C. M., Stijacic Cenzer, I., & Covinsky, K. E. (2012). Loneliness in older persons: A predictor of functional decline and death. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(14), 1078–1084. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993

- Peters, A., Döring, A., Ladwig, K.-H., Meisinger, C., Linkohr, B., Autenrieth, C., Baumeister, S. E., Behr, J., Bergner, A., Bickel, H., Bidlingmaier, M., Dias, A., Emeny, R. T., Fischer, B., Grill, E., Gorzelniak, L., Hänsch, H., Heidbreder, S., Heier, M., … Holle, R. (2011). Multimorbidität und erfolgreiches Altern. Zeitschrift Für Gerontologie Und Geriatrie, 44(S2), 41–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-011-0245-7

- Phillips, A. C., Ginty, A. T., & Hughes, B. M. (2013). The other side of the coin: Blunted cardiovascular and cortisol reactivity are associated with negative health outcomes. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 90(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.02.002

- Poscia, A., Stojanovic, J., La Milia, D. I., Duplaga, M., Grysztar, M., Moscato, U., Onder, G., Collamati, A., Ricciardi, W., & Magnavita, N. (2018). Interventions targeting loneliness and social isolation among the older people: An update systematic review. Experimental Gerontology, 102, 133–144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2017.11.017

- Pruessner, J. C., Kirschbaum, C., Meinlschmid, G., & Hellhammer, D. H. (2003). Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28(7), 916–931.10.1016/S0306-4530(02)00108-7

- Robles, T. F., Slatcher, R. B., Trombello, J. M., & McGinn, M. M. (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 140–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031859

- Schutter, N., Holwerda, T. J., Stek, M. L., Dekker, J. J. M., Rhebergen, D., & Comijs, H. C. (2017). Loneliness in older adults is associated with diminished cortisol output. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 95, 19–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.02.002

- Sheikh, J. I., & Yesavage, J. A. (1985). A knowledge assessment test for geriatric psychiatry. Psychiatric Services, 36(11), 1160–1166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.36.11.1160

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Steptoe, A., Owen, N., Kunz-Ebrecht, S. R., & Brydon, L. (2004). Loneliness and neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory stress responses in middle-aged men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(5), 593–611. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00086-6

- Theeke, L. A. (2009). Predictors of loneliness in U.S. adults over age sixty-five. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 23(5), 387–396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2008.11.002

- Treas, J., Lui, J., & Gubernskaya, Z. (2014). Attitudes on marriage and new relationships: Cross-national evidence on the deinstitutionalization of marriage. Demographic Research, 30, 1495–1526. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2014.30.54

- Victor, C. R., & Bowling, A. (2012). A longitudinal analysis of loneliness among older people in Great Britain. The Journal of Psychology, 146(3), 313–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.609572

- Zebhauser, A., Hofmann-Xu, L., Baumert, J., Häfner, S., Lacruz, M. E., Emeny, R. T., Döring, A., Grill, E., Huber, D., Peters, A., & Ladwig, K. H. (2014). How much does it hurt to be lonely? Mental and physical differences between older men and women in the KORA-Age Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(3), 245–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3998