Abstract

Mental illnesses are the greatest health problems faced by younger people. As a group, tertiary education students demonstrate higher levels of distress than their age matched peers who are not tertiary students, making them an at-risk group for the development of psychopathology. Therefore, this study investigates existing theories of resilience in order to determine how it may be promoted in tertiary education students. Data relating to affect, depression, anxiety, distress, and resilience were collected from 1072 tertiary education students during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of this study found that positive affect was responsible for approximately 25% of the variance in depressive symptoms but less than 10% of the variance in symptoms of anxiety in tertiary students. The results further showed that positive affect was responsible for 21% of variance in overall distress and the 15% of variance in resilience. The findings of this study suggest that positive affect is more closely associated with symptoms of depression than with symptoms of anxiety in tertiary students. The results further suggest that positive affect may be a useful tool for relieving symptoms of depression and overall distress, and improving levels of resilience in this population.

Introduction

Mental illnesses are the greatest health problems faced by younger people (Jurewicz, Citation2015). Whilst medical illnesses tend to impact people later in life, epidemiology studies of mental health disorders show that the majority of mental disorders onset by age 25 (Solmi et al., Citation2022). This earlier onset of mental health problems compared to medical health issues means that mental health problems are responsible for more years lived with a disability than any other health problem (Department of Health, Citation2009). Mental health disorders have negative impacts on both psychological and physical functioning, resulting in large reductions in life expectancy and earnings for people affected by mental ill-health (Productivity Commission, Citation2020). Suicide is the second most common cause of death for people aged 15–29 years worldwide (Karyotaki et al., Citation2020). Individuals living with mental disorder are almost 800% more likely to commit suicide than those who do not have a mental disorder (Brådvik, Citation2018).

As a group, tertiary educations students, who are typically 18–23 years of age, experience higher levels of psychological distress than other young people (Auerbach et al., Citation2016). This is concerning because high levels of psychological distress indicate disordered mental functioning (Kessler et al., Citation2002). The transition from high school to tertiary education settings places new stressors on students such as of moving out of their parents’ home for the first time, more complex social environments, greater independence, increased academic demands whilst experiencing a less scheduled working environment, and financial stress resulting from school fees and lack of paid income (Pidgeon et al., Citation2014; Liu et al., Citation2022). Additionally, the current COVID-19 pandemic is considered by some to be a potentially traumatic event (Bridgland et al., Citation2021), and has been shown to increase levels of distress in tertiary education students (Aristovnik et al., Citation2020). Therefore, addressing the high prevalence of mental health issues in tertiary education students is an important avenue for improving health.

Preventive health practices have long been a component of medical health care systems in developed countries. These systems typically combine preventive and early detection policies with medical care in order to ease the burden of diseases and disability on health facilities, and to help individuals avoid the negative consequences associated with ill health (World Health Organization & United Nations Children’s Fund, 2020). In contrast to medical health services, mental health providers worldwide are still mainly focused on treating mental problems once they arise and place little if any, importance on preventive measures (World Health Organization, Citation2013). This is unfortunate because better preventive mental health practices help individuals avoid further dysfunction associated with the development of mental disorder, such as relationship breakdowns and unemployment, which can lead to further distress in a negative spiral (Productivity Commission, Citation2020). The World Health Organization (Citation2013) has therefore called for more preventive mental health research in order to address the disparity in the understanding and development of effective preventive mental versus medical health practices.

Resilience

A topic in preventive mental health that is receiving an increasing amount of research attention is psychological resilience. There are many definitions of resilience used in mental health research, however the most agreed-on definition is one where an individual does not develop mental health problems after experiencing potentially distressing events (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2013). Although traumatic stress has been shown to cause a number of mental disorders, data indicate that the majority of people are resilient after being exposed to potentially traumatic events (Koenen et al., Citation2017). Our current understanding about how to better promote resilience is limited (World Health Organization, Citation2017). Given the problem of deteriorating mental health of tertiary education students outlined above, this article will investigate existing theories of resilience in order to better understand how to improve mental health in this population.

Theories of resilience

Early work seeking to understand the etiology of mental disorder found that depression is associated with negative affect and a lack of positive affect, whereas anxiety is associated with high negative affect (Clark & Watson, Citation1991). In their review of psychometric measures of various mood disorders, Clark and Watson (Citation1991) found that, like many negative mood states, depression and anxiety shared substantial overlap in nonspecific negative emotionality. Watson et al. (Citation1988a) labeled this nonspecific negatively valanced emotionality as “negative affect”, which is characterized by the negative emotional states of hyperactivity and hyperactivation. Clark and Watson’s (Citation1991) review also found that depression could be differentiated from anxiety by the absence or low occurrence of positive affect, which is defined by positive emotions and feelings of energy and pleasurable engagement (Watson & Clark, Citation1984). Watson et al. (Citation1988a) demonstrated that negative affect shared a similar relationship with symptoms of both anxiety and depression, whereas positive affect was more strongly associated with depression than anxiety.

Another existing resilience theory, namely Fredrickson’s (Citation2001) Broaden and Build Theory, (), proposes that positive emotions counteract the effect of negative emotions. As per this theory, positive emotions allow individuals to resume normal functioning after being exposed to stressors. The underlying assumption of Broaden and Build Theory is that positive affect counteracts the avoidance orientation of negative affect and motivates individuals to reengage with the environment. Fredrickson believed that this engagement helps to build resources which can be utilized to manage future stressors. Fredrickson (Citation2001) provides the link between joy and pro-social behavior as an example of Broaden and Build theory. Fredrickson explains that joy promotes behavior that helps to build social bonds, and that these social bonds in turn become social support in times of need. Fredrickson (Citation2001) further stated that if positive emotions impact on stress and mental health outcomes, then it may also be useful for promoting psychological resilience. Although Fredrickson presented evidence from previous studies that positive affect reduces the physiological effects of stress, the author did not investigate this association. However, Tugade and Fredrickson (Citation2004) later demonstrated a positive association between positive affect and resilience as measured by the Ego Resilience Scale (Block & Kremen, Citation1996), indicating that positive affect may be useful for enhancing resilience.

Studies investigating Broaden and Build Theory

The association between positive affect and distress has been further explored in multiple studies. A meta-analysis by Khazanov and Ruscio (Citation2016) found that the relationship between positive affect and anxiety was comparable, if slightly less strong, with that of positive affect and depression in both cross-sectional and prospective studies, with no significant difference in effect sizes between the two outcomes. A more recent intervention study showed that improved reward sensitivity had a larger effect on increasing positive affect, and relieving depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal ideation, than an equivalent program designed to relieve negative affect through decreased threat sensitivity (Craske et al., Citation2019). However, a further previous intervention study demonstrated that positive activity interventions reduced anxiety as well as depressive symptoms, but that the effect size for reducing depressive symptoms was approximately twice as strong than for symptoms of anxiety (Taylor et al., Citation2017). Finally, another study found that the level of positive affect while experiencing a stressful event explained 10.4% of the variance in depressive and 54.8% of the variance in anxiety symptoms seven years post-exposure to an adverse event (Rackoff & Newman, Citation2020). Collectively, previous research demonstrates that whilst positive affect has a reliable effect on reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety, the strength of the relationships between variables varied considerably amongst the studies.

In summary, previous studies demonstrate that tertiary education students are an at-risk group for the development of mental disorder due to their high levels of distress. Previous research into the development of anxiety and depressive disorders hold conflicting views about the role of positive affect in the development of anxiety. Clark & Watson’s Tripartite Model (1991) suggests that depression is associated with negative affect and a lack of positive affect, whereas anxiety is associated with high levels of negative affect. However, Fredrickson’s (Citation2001) Broaden and Build Theory proposes that positive affect helps to promote engagement and build stress management resources, such as social support, which individuals can draw on to help overcome future challenges and relieve distress. The majority of previous studies empirical studies found that positive affect has a larger impact on symptoms of depression than anxiety (Craske et al., Citation2019; Khazanov & Ruscio, Citation2016; Taylor et al., Citation2017), whilst one study found that positive affect has a much stronger relationship with symptoms of anxiety than depression in the long term (Rackoff & Newman, Citation2020). Therefore, this study will seek to determine the relationship between positive affect and symptoms of both depression and anxiety in order to further explore the mixed findings in this area.

The current study will also investigate the moderating effect of positive affect on the relationship between negative affect and mental health outcomes in tertiary education students. Finally, it will also explore the relationship between positive affect and psychological resilience as suggested by Fredrickson’s (Citation2001) Broaden and Build Theory as frameworks for improving resilience in tertiary education students.

The research questions of this study are:

Are positive emotions negatively related to symptoms of depression and anxiety in tertiary education students?

Does positive affect moderate the relationship between negative affect and mental health outcomes in tertiary education students?

Are positive emotions related to resilience in tertiary education students?

Method

Procedure

This study utilized a cross sectional, observational method. Ethical approval was provided by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID:25241). A dedicated website and Facebook page were created to advertise the study and refer individuals who were interested in learning more about the study before participating. The web pages included background information about the study area and a direct link to the information sheet and survey on Qualtrics. The study was advertised on the Monash SONA systems participant recruitment webpage, Twitter, and a number of student-run Facebook pages representing their respective tertiary education institutions.

Data were collected for 5.5 months during the COVID-19 pandemic, beginning on 06/09/2020 and ending on 22/02/2021. Participants completed the survey on the Qualtrics survey platform. Instructions on how to complete the survey and support services if adversely affected were contained in an explanatory statement on the first page of the survey. Questions were optional and participants could proceed without answering all questions. The eligibility criteria included: aged 18 years or above, living in Australia, and enrolled in an Australian tertiary education institution. The survey was open to all tertiary students above 18 years old in order to allow analyses investigating the relationship between age and distress. Consent was provided by clicking on the link to begin the survey. Upon completion of the survey, participants could opt to enter a prize draw for one of 100, $20 shopping vouchers.

The current study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE, Citationn.d.) reporting guidelines. The study was registered on the Centre for Open Science (Citationn.d.) open science forum website. The participant questionnaire and explanatory statement for the study are available at: https://osf.io/8wc7s/?view_only=68b52e9d0bdd4ceeaae1e1dc7cb7f4b9

Participants

All tertiary education students 18 years and over and studying in Australia were eligible to participate in the study. Participants were recruited online and data were collected using an online survey. In total, 1264 participants enrolled in the study and 1075 completed the entire survey, representing an 85.10% completion rate. Participants self-reported their age (M = 25.54, SD = 8.18), gender (69.7% women, 29.2% men, 0.7% trans/non-binary). Participants were all residing in Australia and enrolled in an Australian tertiary education institution. Categories for participant age were created to mirror the way this variable is presented in Australian Bureau of Statistics data. Participant demographics are displayed in .

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Measures

Kessler 10-item psychological distress inventory

The K-10 (Kessler et al., Citation2002) is a short screening instrument used in national mental health surveys. The K-10 consists of two subscales which measure depression (six items) and anxiety symptoms (four items). Participants indicate their response using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “none of the time” to “all of the time”. Total scores of 19 or below indicate probable non-cases of distress, scores ranging from 20 to 29 indicate moderate to high levels of distress, with scores of 30–50 indicate probable severe mental illness (Kessler et al., Citation2002). Internal consistency reliability was rated as excellent in the original K-10 validation which included data from an Australian Government National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being (Cronbach’s a = 0.92; Kessler et al., Citation2002). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the current study was also calculated as excellent (0.91; Cortina, Citation1993).

International positive and negative affect schedule short form (I-PANAS-SF)

The 10 item I-PANAS-SF (Thompson, Citation2007) is a shortened version of the 20 item PANAS (Watson et al., Citation1988b). Both of these scales contain two separate scales which separately measure positive and negative affect (PA and NA). The I-PANAS-SF was constructed due to criticism of the original PANAS for containing language that is colloquial to North America, and for being too long. The I-PANAS-SF was developed to overcome these problems by making the meaning of items clearer and by halving the number of items in order to reduce participant fatigue. It contains items taken from the 20-item PANAS that are believed to the most relevant for international audiences. Participants indicate the correct response using a five-point Likert rating scale with responses ranging from “very slightly or not at all” to “extremely”, indicating the extent they have felt this way over the past week. A previous validation study of the I-PANAS-SF with a sample of tertiary education students demonstrated acceptable reliability of α = 0.75 for the PA subscale and good reliability of α = 0.80 for the NA scale (Karim et al., Citation2011). Internal consistency measures for the current study were good at α = 0.81 for the PA subscale and α = 0.82 for the NA subscale (Cortina, Citation1993).

Brief resilience Scale

The brief resilience scale is a short, six item measure of resilience (Smith et al. Citation2008). The BRS measures participants’ ability to bounce back or recover from stress. Participants choose the correct response from a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The BRS consists of three positively worded and three negatively worded items in order to avoid repetitive responses. Items 2, 4 and 6 are reverse scored. The BRS was originally validated using two samples of undergraduate students which resulted in good internal consistency of α = 0.84 and α = 0.87 respectively. The BRS demonstrated good reliability for the current study, calculated as α = 0.88 (Cortina, Citation1993).

Data cleaning and analyses

Of the 1264 responses to the study, 189 participants did not complete at least the demographic questions and first inventory and were therefore omitted from the analysis. A further three participants were omitted for repetitive response styles, leaving a total of 1072 participants. Additionally, the trans/non-binary category was automatically deleted by SPSS from analyses involving gender categories due to the small sample size. All data analyses were performed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM Corp, Citation2020). A Little’s MCAR test on the remaining data was significant: χ2 (458, N = 27623) = 582.384, p < .001, indicating that missing data were not missing completely at random. However, the maximum amount of data missing for any variable was only 1.5%. This is below the recommended threshold of 2% where the amount of missingness is likely to impact the results of analyses (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2018). This indicates that missing data should not bias the results of further analyses and that the significant result of the MCAR test may have been impacted by the large sample size. Therefore, listwise deletion was used for all analyses.

Scale scores were calculated according to the author instructions and SPSS explore procedure was utilized to assess normality of the data. Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests were significant for all scale scores, indicating non-normal distribution for all variables. Histograms indicated positive skew for Negative Affect and K-10 Distress (both the depression and anxiety sub scales). However, this was not severe in the histograms or in Q-Q plots. Therefore, it would be unlikely to have much impact on the results given that small departures from normality have little impact on analyses when using a large sample (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2018). A scatterplot matrix further revealed no bivariate outliers for all variables resulting in the retention of the 1072 participants.

To address the research questions of whether positive emotions are negatively related to symptoms of depression and anxiety and positively related to resilience in tertiary education students, correlation analyses were used to determine relationships between positive and negative affect, distress, and resilience. T/F-tests were used to calculate relationships and effect sizes between demographic variables and depression, anxiety, overall distress, and resilience. Multiple Regression analyses were used to calculate the unique association between positive and negative affect and both distress and resilience. Moderation analyses were utilized to investigate the impact of positive affect on the relationship between negative affect and symptoms of depression and anxiety, overall distress and resilience. The threshold for statistical significance for all analyses was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Demographic correlates

There was a statistically significant difference in symptoms of depression between the four age groups: F(3,1036) = 5.12, p < .001, η2 = 0.015, 95% CI [0.005, 0.030], indicating a small effect. Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that the mean depression scores for 18–24 participants were significantly higher than scores from the 45 plus age range.

There was also a statistically significant difference in symptoms of anxiety between the four age groups: F(3,1036) = 7.418, p < .001, η2 = 0.021, 95% CI [0.006, 0.039], indicating a small effect. Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that the mean anxiety scores for 18–24 participants were again significantly higher than scores from the 45 plus age range.

Scores for overall distress (total K10 score) were significantly different between the four age groups: F(3,1036) = 6.82, p < .001, η2 = 0.019, 95% CI [0.005, 0.037], indicating a small effect. Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that mean overall distress scores for 18–24 participants were significantly higher than scores from the 45 plus age range.

There was also a statistically significant difference in resilience between the four age groups: F(3,1057) = 4.033, p = .007, η2 = 0.011, 95% CI [0.001, 0.025], indicating a small effect. However, post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that no group scored significantly higher in resilience than others, possibly due to the small sample size for the 45+ age group.

Women participants reported higher symptoms of depression t(1032) = 4.04, p < .001, d = 0.28, 95% CI [0.141, 0.409], anxiety t(1032) = 3.13, p = .002, d = 0.213, 95% CI [0.079, 0.347], overall distress (total K10 score) t(1032) = 4.04, p < .001, d = 0.28, 95% CI [141, 0.409] and lower levels of resilience t(1053) = −6.38, p < .001, d = −0.43, 95% CI [−0.565, −0.298] than men, indicating small effect sizes for each variable. Scores for depression, anxiety and overall distress are shown in .

Table 2. Levels of depression, anxiety and overall distress.

Correlations between study variables

Bivariate correlations were calculated in order to examine relationships between the variables involved in the study, and to determine the amount of variance in symptoms of depression, anxiety, overall distress and resilience attributable to both positive and negative affect. Correlations between all study variables are shown in .

Table 3. Bivariate correlations between all study variables.

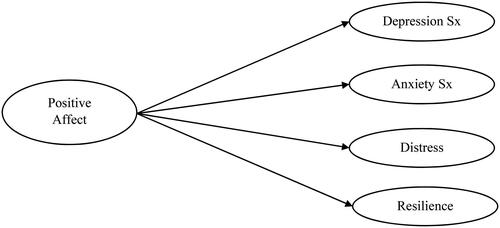

Multiple regression analyses

Multiple regression analyses were performed to investigate the unique variance attributable to symptoms of depression, anxiety, overall distress and resilience by positive and negative affect. Significant regression equations were found for depression [(F(2,1038) = 707.607, p < .001), R2 change = 0.576. Depressive symptoms = 11.962 + 0.603 (NA) −0.327 (PA). Both PA and NA were significant predictors of depressive symptoms, anxiety [(F(2,1042) = 369.170. p < .001, R2 change = 0.414. Anxiety symptoms = 5.578 + 0.599 (NA) − 0.124 (PA). Both PA and NA were significant predictors of anxiety symptoms], overall distress [(F(2,1035) = 787.828, p < .001), R2 change = 0.603. Overall distress = 17.606 + 0.656 (NA) − 0.275 (PA). Both PA and NA were significant predictors of overall distress and resilience [(F(2, 1045) = 241.193, p <.001) R2 change = 0.315. Resilience = 19.093 + 0.269 (PA) − 0.427 (NA). Both PA and NA were significant predictors of overall resilience]. Regression statistics for all variables attributable to positive and negative affect are given in .

Table 4. Variance attributable to positive and negative affect.

Moderation analyses

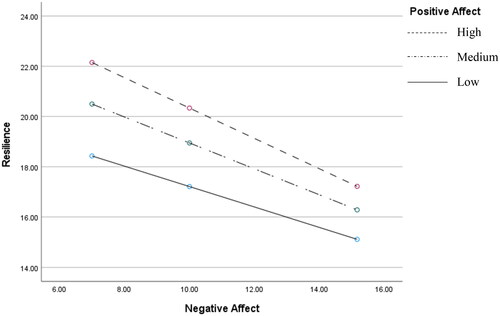

Moderation analyses were performed to determine the impact of positive affect on the relationship between negative affect and symptoms of depression, anxiety, overall distress and resilience. The results of the moderation analyses were not significant for symptoms of depression R2 = 0.001, F(1,1037) = 1.496, p = .222, b = 0.025, t(1037) = 1.223, p = .222, anxiety R2 = 0.002, F(1,1041) = 3.739, p = .053, b = 0.047, t(1041) = 1.934, p = .053, or overall distress R2 = 0.001, F(1,1034) = 3.258, p = .071, b = 0.036, t(1034) = 1.805, p = .071. However, the moderation analysis for positive affect on negative affect by resilience was significant R2 = 0.006, F(1,1044) = 9.023, p = .003, b = −0.079, t(1044) = −3.004, p = .003. These results indicate that positive affect has a significant impact on the relationship between negative affect and resilience, but positive affect did not impact on the relationship between negative affect and symptoms of depression, anxiety or overall distress. The pattern of results for the moderation by positive affect on the relationship between negative affect and resilience indicates that resilience decreases as both positive and negative affect increase. The Moderation of the relationship between Negative Affect and Resilience by Positive Affect is displayed in .

Discussion

This project aimed to investigate whether positive affect is involved in the presentation of symptoms of depression, anxiety, and resilience in tertiary education students. Previous findings from research on the beneficial effect of positive affect on mental health outcomes are conflicting. The Tripartite Model of Depression and Anxiety (Clark & Watson, Citation1991) states that depression is associated with both positive and negative affect whereas anxiety is more closely related to negative affect than positive affect. In comparison, Fredrickson’s (Citation2001) Broaden and Build Theory implies that positive affect is equally important in the development of both depression and anxiety. Multiple empirical studies have found evidence for the impact of positive emotions in the development of symptoms of both depression and anxiety (Craske et al., Citation2019; Khazanov & Ruscio, Citation2016; Rackoff & Newman, Citation2020; Taylor et al., Citation2017). However, the strength of the relationship between positive affect and symptoms of anxiety and depression vary considerably between studies. Therefore, this study investigated the relationship between affect and depression, anxiety, overall distress, and resilience to determine the role of both positive and negative affect across these dimensions of mental functioning in tertiary education students.

In the present study, multiple regression analyses indicated that both age and gender are related to levels of depression, anxiety, overall distress, and resilience. The results demonstrated that women and younger people experienced higher levels of depression, anxiety, and distress, and lower levels of resilience than men and older students respectively. These findings are similar to the results of previous studies which also found that women and younger students experienced higher levels of these negative mental health outcomes than men and older students (Jurewicz, Citation2015; Kuehner, Citation2017; Li & Graham, Citation2017; Solmi et al., Citation2022). The finding that younger tertiary students experience higher levels of distress than older students is similar to previous research showing that younger people in the general population experience higher levels of psychological distress than older people (Auerbach et al., Citation2016). This may be because of the stressors faced by tertiary students outlined in the introduction (Pidgeon et al., Citation2014; Liu et al., Citation2022). In the case of women students, Kuehner (Citation2017) and Li and Graham (Citation2017) explain that higher levels of distress in this population may be due to a range of factors including higher levels of rumination, interpersonal stressors, discrimination and abuse, higher biological susceptibility to distress and lower self-esteem and a lack of gender equality compared to men.

The findings of the multiple regression analyses from the present study also demonstrate that positive and negative affect are both involved in the presentation of symptoms of depression, anxiety, overall distress, and resilience. However, symptoms of depression, anxiety, overall distress, and resilience generally had stronger relationships with negative affect than they did with positive affect. This was particularly evident for anxiety, whose relationship with negative affect was approximately four times stronger than it was with positive affect. In contrast, the relationship between depression and negative affect was less than twice as strong as that with positive affect. Therefore, the findings of the current study show more support for Clark and Watson’s (Citation1991) Tripartite Model which states that anxiety is more closely associated with negative affect than positive affect. This finding indicates that negative affect in tertiary education students would be expected to have a stronger relationship with symptoms of anxiety than depression. Therefore, any intervention which aimed to improve positive affect in tertiary education students would also most likely improve symptoms of depression than anxiety.

The results of the current study further indicated that the only relationship that is moderated by the level of positive affect is that between negative affect and resilience. However, contrary to expectations, the analysis demonstrated that as positive and negative affect increases, resilience decreases. Whilst this seems counterintuitive to the notion that positive affect promotes resilience, the regression analysis showed that positive affect does increase the level of resilience overall. The moderation analysis merely demonstrates that this relationship is higher at lower levels of negative affect than at higher levels. This may be explained by the fact that negative affect has a larger impact on mental health outcomes than positive affect (Yoon et al., Citation2022). Fredrickson (Citation2001) theorized that this occurs because during our evolutionary history it was more important to avoid harm from dangerous events than to perform the kinds of activities promoted by positive affect. This means that tertiary students who are experiencing low levels of negative affect may benefit more greatly from positive affect to improve their resilience than those experiencing high levels of negative affect.

The above finding that the relationship between positive affect and mental health outcomes is weaker when levels of negative affect are high suggests that tertiary students with higher levels of negative affect would benefit more from reducing levels of negative affect than improving positive affect. This illuminates a deficiency with models of mental health service delivery that mostly rely on delivering mental health care once people are unwell. This model does not prioritize reducing negative affect in individuals with pre-clinical levels of mental illness before they develop into full syndrome disorders. As stated earlier, the definition of a resilient trajectory is one where an individual does not experience psychological disorder following potentially traumatic events (Fletcher and Sarkar, Citation2013). Therefore, by definition, only interventions that aim to prevent the development of clinical level of disorder can achieve resilient outcomes. Based on the results of the current study, it is likely that finding avenues to reduce negative affect in students with pre-clinical levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms is just as important, if not more important, as promoting positive affect in order to improve resilience and reduce pathological mental health outcomes in this population.

The results of the current study support the assertion of Broaden and Build Theory (Fredrickson, Citation2001) that positive affect promotes resilience. The multiple regression analysis supported that positive affect is positively related to resilience. This finding is in line with Tugade and Fredrickson’s (Citation2004) study which also investigated the relationship between positive affect and resilience and found a positive relationship between these variables. However, Tugade and Fredrickson’s (Citation2004) study used a much different measure for resilience, the Ego Resilience Scale (Block & Kremen, Citation1996). The Ego Resilience Scale was constructed to measure the Freudian concept of “ego-functioning” (Block & Kremen, Citation1996, p. 350), which the authors explain as the ability of an organism to regulate behavior. In comparison to the Ego-Resilience Scale, the BRS (Smith et al. Citation2008) used in the current study was designed to measure the construct of bouncing back or recovering from stress. These differences in the underlying constructs being measured by these scales mean that these two studies may not be investigating exactly the same relationship between constructs. Therefore, this must be kept in mind when interpreting the similar findings between the two studies.

In summary, the findings of the current study most closely align with Clark and Watson’s (Citation1991) Tripartite Model of Depression and Anxiety, which states that the relationship between positive affect and anxiety is much weaker than that between positive affect and depression. However, the findings of the current study are also partially supportive of Fredrickson’s (Citation2001) Broaden and Build Theory which states that positive affect reduces distress, considering that a relationship was found between positive affect with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and resilience. Therefore, the current study demonstrates that the relationship between positive affect and mental health outcomes in tertiary education students is not as strong as that between negative affect and mental health. The current study further demonstrates that the relationship between positive affect and symptoms of anxiety in tertiary education students is not as strong as that found in previous studies (Craske et al., Citation2019; Khazanov & Ruscio’s, Citation2016; Taylor et al., Citation2017). Finally, the results suggest this may be due to high levels of negative affect experienced by tertiary students considering the finding that negative affect moderates the relationship between positive affect and mental health outcomes in this population

Theoretical and practical implications

The finding that the relationship between positive affect and depression, anxiety, overall distress, and resilience is not as strong for tertiary students experiencing higher levels of negative affect is intuitive. It would be expected that positive affect only helps to relieve negative symptoms up to a certain point. This is because the majority of the problems an individual may be experiencing and which are responsible for producing negative affect would be unlikely to simply disappear with the addition of positive affect. Whilst it is possible that positive affect may help to attenuate the impact of negative affect as suggested by Fredrickson (Citation2001), this is unlikely to have much effect on the underlying causes of negative affect in the short term. It may be that the case that positive affect encourages greater stress management and reductions in anxiety in the longer term as suggested by the results of Rackoff and Newman’s (Citation2020) study. However, this phenomenon is beyond the scope of the current study and would be a potentially useful avenue for future research.

In terms of improving resilience in tertiary education students, the results of the current study suggest that positive affect may have some impact on alleviating negative mental health symptoms and improving resilience. However, the relationship between positive affect and symptoms of depression and resilience is much stronger than with symptoms of anxiety. This is a useful finding because it demonstrates that simple interventions that promote positive affect in tertiary education students may reduce symptoms of depression, improve resilience and have some, however less, impact on symptoms of anxiety. The current study also demonstrates that alleviating negative affect in tertiary education students would most likely have a larger impact on reducing negative mental health symptoms in the short term than the promotion of positive affect. Therefore, interventions aiming at reducing negative affect as well as improving positive affect should help to reduce the high prevalence of distress and mental disorder and improve the quality of life in tertiary education students.

Limitations and future directions

The most important limitation of the current study is that it uses cross-sectional data. Therefore, this study can only measure relationships between variables rather than the impact of positive affect on the measured outcomes. It would be beneficial to conduct further longitudinal or experimental studies using the same variables in order to better instigate the utility of existing resilience theories for informing resilience training programs in tertiary education students. Another limitation of this study is that the measurement of the constructs all relied on self-report. This could potentially introduce common method bias due to differences in the overlapping variance and ultimately influence the strength of the relationships between the study variables. Additionally, all of the participants in this study are tertiary education students, which means that the results may not generalize to non-tertiary students. It would therefore be beneficial to repeat the study using a more general sample to determine whether positive affect has the same impact on mental health outcomes in the wider population. Finally, the data for this study were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is possible that this event impacted mental health of participants during this period, and therefore the results may not be applicable to times where students are experiencing lower levels of distress and disorder.

Though the findings align with the majority of previous work which also found that a positive effect has a stronger relationship with depression than it does with anxiety (Khazanov & Ruscio’s, Citation2016; Taylor et al., Citation2017; Craske et al., Citation2019), one previous study found that positive affect had a much stronger impact on symptoms of anxiety than depression many years after exposure to a stressful event (Rackoff & Newman, Citation2020). Therefore, it may also be useful to investigate whether positive affect has a greater impact on anxiety in the long term rather than in the present. This may also be a better way to examine Fredrickson’s Broaden and Build Theory (2001), which explicitly states that positive affect helps to build coping resources which can be used for managing future stressors. This interpretation of Broaden and Build theory means it would most likely take some time for positive affect to help individuals to build these coping resources and for them to have an impact on mental health outcomes.

Conclusion

The findings of the current study help to alleviate some of the confusion around the role of positive affect in the presentation of anxiety and depression due to conflicting ideas contained in existing models of resilience and stress management. The findings of the current study indicate that the Tripartite Model of Depression and Anxiety (Clark & Watson, Citation1991) is the most suitable model for estimating the relationship between positive affect and symptoms of anxiety in tertiary education students. In line with the Tripartite Model, the current study found that the relationship between positive affect and anxiety is much weaker than that between negative affect and anxiety as well as between positive affect and depression. This means that interventions that aim to improve mental health outcomes in tertiary education students need to reduce negative affect as well as improve positive affect. However, although the results of the current study demonstrate better support for the Tripartite Model, this does not necessarily mean that Fredrickson’s (Citation2001) Broaden and Build Theory is wrong. In line with Broaden and Build theory, our findings suggest that positive affect is involved in the presentation of symptoms of depression, as well as with symptoms of anxiety to some degree. Additionally, the combined results of this study and previous research investigating the relationship between positive affect and mental health suggest that positive affect may have a stronger relationship with symptoms of anxiety in the long term. This indicates that the impact of positive affect on mental health outcomes of tertiary education students may occur in the longer term rather than having an immediate effect, however this idea requires further empirical investigation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

David Tuck is a PhD candidate in the School of Educational Psychology and Counselling at Monash University. His work mainly focuses on preventive mental health approaches in young people and other vulnerable populations.

Lefteris Patlamazoglou, PhD (he/him) is a counselling psychologist and lecturer in the School of Educational Psychology and Counselling at Monash University, Australia. In his counselling practice, teaching and research, Lefteris adopts the framework of intersectionality whereby individuals’ multiple identities intersect to create novel experiences of mental health and illness. Lefteris has a particular research interest in the wellbeing, grief and belonging of LGBTQIA+ young people and adults.

Dr. Joshua Wiley is a behavioural medicine researcher at Monash University in the School of Psychological Sciences and Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health and Honorary Research Fellow at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre. His research includes basic science and applied intervention work, particularly around understanding and improving sleep and mental health after cancer.

Dr Emily Berger is an Australian researcher who specialises in the areas of childhood trauma, trauma-informed practice, disasters and rural health, suicide and self-injury, child and youth mental illness, and teacher professional development. She is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Educational Psychology and Counselling, Faculty of Education, Monash University, and an Adjunct Senior Research Fellow with Monash’s School of Rural Health, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences. Dr Berger is a Registered and Endorsed Educational and Developmental Psychologist and Board-Approved Supervisor with the Psychology Board of Australia. She has worked as a child, adolescent and family psychologist in schools and private clinic settings. For over 15 years as an academic and psychologist, Dr Berger has maintained collaborative partnerships across various educational settings, not-for-profit organisations, government departments and community groups.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aristovnik, A., Keržič, D., Ravšelj, D., Tomaževič, N., & Umek, L. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability, 12(20), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208438

- Auerbach, R. P., Alonso, J., Axinn, W. G., Cuijpers, P., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hwang, I., Kessler, R. C., Liu, H., Mortier, P., Nock, M. K., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N. A., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Andrade, L. H., Benjet, C., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., Demyttenaere, K., … Bruffaerts, R. (2016). Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organisation World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 46(14), 2955–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001665

- Block, J., & Kremen, A. M. (1996). IQ and ego-resiliency: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 349–361. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.349

- Brådvik, L. (2018). Suicide risk and mental disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(9), 2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15092028

- Bridgland, V. M. E., Moeck, E. K., Green, D. M., Swain, T. L., Nayda, D. M., Matson, L. A., Hutchison, N. P., & Takarangi, M. K. T. (2021). Why the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic stressor. PLOS One, 16(1), e0240146. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240146

- Centre for Open Science. (n.d.). OSFREGISTRIES The open registries network. Retrieved April 3, 2023, from https://www.cos.io/registries

- Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

- Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 316–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.316

- Craske, M. G., Meuret, A. E., Ritz, T., Treanor, M., Dour, H., & Rosenfield, D. (2019). Positive affect treatment for depression and anxiety: A randomized clinical trial for a core feature of anhedonia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(5), 457–471. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000396

- Department of Health. (2009). Mental health in Australia. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-pubs-f-plan09-toc∼mental-pubs-f-plan09-con∼mental-pubs-f-plan09-con-mag

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218

- Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist, 18(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

- IBM Corp. (2020). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY.

- Jurewicz, I. (2015). Mental health in young adults and adolescents – supporting general physicians to provide holistic care. Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 151–154. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.15-2-151

- Karim, J., Weisz, R., & Rehman, S. U. (2011). International positive and negative affect schedule short-form (I-PANAS-SF): Testing for factorial invariance across cultures. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 2016–2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.046

- Karyotaki, E., Cuijpers, P., Albor, Y., Alonso, J., Auerbach, R. P., Bantjes, J., Bruffaerts, R., Ebert, D. D., Hasking, P., Kiekens, G., Lee, S., McLafferty, M., Mak, A., Mortier, P., Sampson, N. A., Stein, D. J., Vilagut, G., & Kessler, R. C. (2020). Sources of stress and their associations with mental disorders among college students: Results of the World Health Organization world mental health surveys international college student initiative. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 1759. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01759

- Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., Walters, A. M., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006074

- Khazanov, G. K., & Ruscio, A. M. (2016). Is low positive emotionality a specific risk factor for depression? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 142(9), 991–1015. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000059

- Koenen, K. C., Ratanatharathorn, A., Ng, L., McLaughlin, K. A., Bromet, E. J., Stein, D. J., Karam, E. G., Meron Ruscio, A., Benjet, C., Scott, K., Atwoli, L., Petukhova, M., Lim, C. C. W., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Bunting, B., Ciutan, M., de Girolamo, G., … Kessler, R. C. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 47(13), 2260–2274. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717000708

- Kuehner, C. (2017). Why is depression more common among women than among men? The Lancet. Psychiatry, 4(2), 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30263-2

- Li, S. H., & Graham, M. D. (2017). Why are women so vulnerable to anxiety, trauma-related and stress-related disorders? The potential role of sex hormones. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30358-3

- Liu, X. Q., Guo, Y. X., Zhang, W. J., & Gao, W. J. (2022). Influencing factors, prediction and prevention of depression in college students: A literature review. World Journal of Psychiatry, 12(7), 860–873. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v12.i7.860

- Pidgeon, A. M., Rowe, N., Stapleton, P. B., Magyar, H. B., & Lo, B. C. Y. (2014). Examining characteristics of resilience among university students: An international study. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 02(11), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2014.211003

- Productivity Commission. (2020). Mental health, report no. 95, Canberra https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/report

- Rackoff, G. N., & Newman, M. G. (2020). Reduced positive affect on days with stress exposure predicts depression, anxiety disorders, and low trait positive affect 7 years later. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129(8), 799–809. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000639

- Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. International journal of behavioral medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

- Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., Salazar de Pablo, G., Il Shin, J., Kirkbride, J. B., Jones, P., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Carvalho, A. F., Seeman, M. V., Correll, C. U., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2022). Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(1), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

- STROBE. (n.d.). What is STROBE? Retrieved August 11, 2021, from https://www.strobe-statement.org/

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2018). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Taylor, C. T., Lyubomirsky, S., & Stein, M. B. (2017). Upregulating the positive affect system in anxiety and depression: Outcomes of a positive activity intervention. Depression and Anxiety, 34(3), 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22593

- Thompson, E. R. (2007). Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106297301

- Tugade, M. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 320–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320

- Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin, 96(3), 465–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.96.3.465

- Watson, D., Clark, L., & Carey, G. (1988a). Positive and negative affectivity and their relation to anxiety and depressive disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(3), 346–353. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.97.3.346

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988b). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063

- World Health Organization. (2013). The European mental health action plan. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/194107/63wd11e_MentalHealth-3.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2017). Building resilience: a key pillar of health 2020 and the sustainable development goals. Examples for the WHO small countries initiative. WHO Regional Office for Europe. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/341075/resilience-report-050617-h1550-print.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organization & United Nations Children’s Fund. (2020). Operational framework for primary health care: transforming vision into action. World Health Organisation https://www.who.int/health-topics/primary-health-care#tab=tab_1

- Yoon, D. J., Bono, J. E., Yang, T., Lee, K., Glomb, T. M., & Duffy, M. K. (2022). The balance between positive and negative affect in employee well-being. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(4), 763–782. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2580