Abstract

This study explored conceptually and empirically the ways in which those engaged with university-based arts and humanities research (researchers, managers, partners, beneficiaries) construct and respond to the challenges of generating, interpreting, and demonstrating the cultural value of research. Cultural value is a contested concept, beset by philosophical, practical and political tensions. We argue that interpretations of value – cultural or otherwise – are part of complex ecologies of cultural life, creation and understanding, while at the same time underpinning economies of description, prescription, inscription and ascription. Meaning, expression, narrative and practice, combined and recombined in experience, are core themes in our participants’ description of the arts and the humanities. However, more needs to be done across all levels of the research governance system so that meaningful engagement is sustained and narratives in cultural terms are not perceived as a risk in accountability contexts.

Introduction

The value of arts and humanities research has long been the object of scholarly argument, political debate, and administrative regulation, in the UK and internationally (Plumb Citation1964, Selwood Citation2002, Bate Citation2011, Belfiore and Upchurch Citation2013). In a context of ‘silent crisis’ (Nussbaum Citation2010, p. 1), anxieties about fissures and imbalances in knowledge and inquiry (Snow Citation1959/1998) are seen as compounded by the so-called ‘economistic agenda’ (Collini Citation2012, p. xii), ‘politics of metrics’ (Donovan Citation2009) and ‘performative metricisation’ (Kelly and Burrows, in Adkins and Lury Citation2012, p. 130) of universities. On the background of a discourse of ‘doom’ and ‘gloom’ (Belfiore and Bennett Citation2010, p. 133, Belfiore and Upchurch Citation2013, p. 17), a ‘crisis of legitimacy’ (Holden Citation2006) is seen to be plaguing the arts and the humanities, as accountability regimes tighten and funding becomes more concentrated around STEM research.

Responses to these debates have mobilised evidence about the considerable contributions of the arts and the humanities to wealth creation, organisational health, creative capacity, positive community dynamics, individual learning and well-being, as well as arguments for the ‘intrinsic’ value of cultural works, understanding and experiences (e.g. Matarasso Citation1997, McCarthy et al. Citation2004, Staricoff 2004, Hewison Citation2006, Holden Citation2006, Bakhshi and Throsby Citation2010, O’Brien Citation2010, Selwood Citation2010, Knell and Taylor Citation2011, Holden and Balta Citation2012, Carnwath and Brown Citation2014). For example, the essays in Bate (Citation2011) describe the cumulative contributions of humanities research to show that ‘the value of the humanities is neither negligible nor ineffable’ (O’Neill, in Bate Citation2011, p. vi). Parker (in Belfiore and Upchurch Citation2013, p. 60) argues that the humanities ‘give citizens and students the qualities to deal with, operate and flourish in a fearful and uncertain global world’. Zuidervaart (Citation2011, p. 44, 316s) sees the arts as ‘societal sites for imaginative disclosure’ of purposes, meanings and of ‘the potential for a fully democratic society’. In their intellectual history of claims about the impacts of the arts, Belfiore and Bennett (Citation2010, p. 39) offer a ‘taxonomy’ of eight ‘possible impacts’, both negative and positive.

The exploratory study reported in this paper aimed to further the conceptual understanding of how cultural value is interpreted in arts and humanities research, by grounding it in empirical knowledge about how interpretations of value play out in practice. The research question addressed in this paper is: ‘How do those engaged in and with university-based arts and humanities research generate, interpret, and demonstrate the cultural value of research?’.

Cultural value/s, valuing and valorisation

We approached the study with an initial sense of culture as ‘a whole way of life’ (Williams Citation1958) and ‘the whole range of practices and representations through which a social group’s reality (or realities) is constructed or maintained’ (Frow Citation1995, p. 3); of valuing as a set of practices arising out of ‘a complex interplay between institutional structures, interpretive communities, and the idiosyncrasies of individual[s]’ (Felski Citation2008, p. 20) and which involve both ‘prizing’ (holding dear or in high regard), and ‘appraising’ (assigning value through comparison) (Dewey Citation1939, p. 5); and of research as ‘systematic inquiry made public’ (Stenhouse Citation1981, p. 104). However, the nature and diversity of the arts and the humanities and their concern with what it means to be human makes them areas of inquiry that are particularly rich not only in terminology related to value (e.g. about the diversity of cultural values, the cultural framing of processes of valuation, and the valorisation or ‘utilisation’ of cultural goods – Andriessen Citation2005), but also in critiques of its conceptual and normative force. In exploring the different vocabularies and discourses of value, we drew on theoretical resources that enabled us to conceptualise the study and sensitised us to the different perspectives shaping the participants’ accounts, in line with our exploratory and theory-generation aims. The remainder of this section reviews these theoretical resources.

The valorisation of cultural goods

The literature on the valorisation of cultural goods is dominated by cultural economic approaches largely rooted in mainstream economics and rational choice theory. Individual preference and utility, and the relationship between willingness to pay and market price, take centre stage in many studies. Other economic measures attempt to monetise the contributions of universities and of the wider cultural sector to local, national and global economic and social development. This literature often uses dichotomies, such as intrinsic/instrumental, tangible/intangible, monetary/non-monetary value, and private/common goods, to discuss cultural production, distribution and consumption, and to analyse the dynamics of supply and demand involved in, for example, the creative industries, the trade of cultural goods, and the management of cultural heritage.

Yet, there is also increasing critical discussion of these dichotomies, as well as acknowledgment of the importance of narratives, networks and interactions in understanding the plural and contested constructs of value underpinning economic measures and other cultural metrics. Some of this discussion draws on cultural capital theory and cultural anthropology, through critical recognition of the limitations of conventional economic measures in capturing the multi-faceted and constructed nature of cultural value/s (Holden Citation2006, Klamer Citation2004, Hutter and Throsby Citation2011).

For example, Snowball’s (Citation2008, p. 218) discussion of several methods, including net economic impact indicators, contingent valuation, and willingness to pay and choice experiments, concludes that an interdisciplinary, holistic approach would be ‘the best way of valuing complex cultural goods’. Similarly, O’Brien (Citation2010) summarises the tools that have been used to monetise and analyse the cultural benefits of culture, such as contingent valuation, choice modelling, hedonic pricing, and travel cost (HMT Citation2003), but contrasts them with well-being and health approaches to valuation, and with outcome-based and narrative methods from the cultural sector. He notes the ‘need for economic analysis to be placed within robust and detailed narrative accounts of cultural value’ or ‘as part of multi-criteria analysis’ (p. 9).

Donovan (Citation2013) argues for a ‘holistic’ combination of economic and non-economic measures, including qualitative indicators and narrative approaches, which synthesises different types of information and is proportional in cost and effort with the size of the investment being evaluated. Such recommendations chime with debates in economic research. Stiglitz et al. (Citation2009a, Citation2009b), for example, critiqued the excessive focus of current economic measures on ‘inanimate objects of convenience’ (Citation2009b, p. 25), such as the GDP, and recommended enriching policy discussion through the use of ‘new and credible measures’, both objective metrics and subjective assessments, and including non-monetary measures (Citation2009a, p. 216).

Organisational theory complements these techniques with analyses of the creation, conversion and circulation of tangible and intangible value. Normann and Ramirez (Citation1993) and Ramirez (Citation1999) emphasise ‘value constellations’ and the ways in which value is contingent on interactions in networks of co-production: it resides neither in the individuals and their organisations, nor in the goods traded. Something may be considered value in one network, but not in another – ‘value is an emergent property of the network’ itself (Allee Citation2008, p. 8). Spaapen and van Drooge (Citation2011) and Molas-Gallart and Tang (Citation2011) argued that impacts in the social sciences can be captured though understanding the ‘productive interactions’ between researchers and stakeholders. Their argument was picked up in the arts and humanities, for example by Hazelkorn et al. (Citation2013). Molas-Gallart (2014) builds on this work to discuss the diffuse and interactive nature of valorisation processes in the arts and the humanities.

Critiques of cultural valuation

Critical literature on cultural (e)valuation (Rescher Citation2004) draws on literary, sociological, and political theory to reveal the structural and normative tensions that underpin attempts to measure and assess cultural value. While some of these contributions also use dualisms (e.g. high/low culture, mass/elite, digital/analogue), they emphasise the plurality and fluidity of the discourses and practices that constitute cultural valuation, and offer alternative readings of networks as configurations of power or as digital distributions.

For example, Marxist, feminist or poststructuralist perspectives seek to expose the inherently ‘paradoxical’ nature of arguments around cultural value (Connor Citation1992, Bohm and Land Citation2009). They point out the selective nature of definitions of culture as ‘high’ art and scholarship, typically institutionalised in cultural provision for elite consumption, and contrast them with ideas of ‘popular’ culture and with anthropological notions of everyday cultural practices. Some draw on Bourdieu (Citation1984) to discuss the association between judgments of worth phrased in aesthetic terms and class (Belfiore and Bennett Citation2007, Bennett et al. Citation2009). Others note how ‘“cultural” questions of aesthetics, taste and style cannot be divorced from “political” questions about power, inequality and oppression’ (Waterman Citation1998, p. 55) and use such insights to reflect on culture as counterhegemonic tool (Snowball and Webb Citation2008). Following Rancière, the links between the aesthetic and the political are made explicit, in particular the role of the arts in ‘the distribution of the sensible’ (Rancière, Citation2004, p. 7, see also Vuyk Citation2010).

Thus, cultural value vocabularies have a multi-level indexical quality that signals affiliation to particular powerful discourses, such as academic connoisseurship, economic pragmatism, or ‘grassroots’ activism. Critical theory, critical discourse analysis, and postcolonial scholarship address the discursive shifts in recent policy towards more performative agendas for the cultural sector (Bohm and Land Citation2009). Duelund (Citation2008), referencing Habermas’s (Citation1987) analysis of conflicts between system rationalities and communicative action, argues that a wave of economic colonisation of cultural policy discourses in (Northern) Europe was followed by political colonisation, which prioritises economic and social cohesion objectives over educational and aesthetic ones. The issue of cultural inequalities in an environment driven by ‘marketplace arrogance’ is raised by Ivey (Citation2008, xix/2/264), who argues instead for an ‘expansive view’ of value that secures citizens’ right to a ‘vibrant expressive life’.

Selwood (Citation2010, p. 20), however, objects that advocacy for the ‘transformative power’ of cultural life, however expansively viewed, is itself ‘instrumentalist’ in assuming a ‘functional relationship between personal and societal transformation’. The ‘apple-pie’ discourse of ‘public value’, with its associated measures of preference and satisfaction, is an instrument for ‘consumerization’ of politics and of citizenship, argue Lee et al. (Citation2011, p. 298).

Further challenge to dualist and linear accounts of cultural value arises from ‘post-critical’ and non-representational notions of digital thinking in distributed networks. Recent work on cultural value and digital culture draws on Thrift’s (Citation2008) idea of rhyzomatic, messy, and mutable cultural practices, as well as on De Certeau (Citation1988) and Latour (Citation2007), to investigate economies and ecologies of experience, image and labour (Walsh et al. Citation2012).

Understanding cultural value/s

The interest in plural and dynamic configurations of value is clear in work that attempts explicitly to move beyond the dichotomies visible in some of the cultural economics literature and its critiques. Matthes (Citation2013) notes the philosophical complications surrounding the ideas of uniqueness, incommensurability, and irreplaceability that may accompany discussions of value. Other philosophers of values seek to transgress ‘unnecessary polarizations’ (Joas Citation2000) between liberal and communitarian, individualist and collectivist, universalist and particularist, materialistic and postmaterialistic, objectivist and subjectivist perspectives on value/s. Dewey’s (Citation1939) discussion of intersubjective valuation underpins proposals that refuse to reduce value to either a quality of the object, or a mental quality of the subject, and reject a dichotomy between intrinsic and extrinsic, or instrumental, value.

Literary and art criticism and cultural studies discuss the historical nature of conceptions of value and the multidimensional nature of aesthetic experience. For example, Belfiore and Bennett (Citation2007) note how artistic experience is shaped by social, cultural and psychological factors, at environmental, artistic, and individual levels. Felski (Citation2008, p. 133) identifies four ‘intertwined’ responses to literary works: recognition; enchantment; knowledge; and shock. Brown (2006) also argues for a multi-dimensional understanding of the benefits of arts, including personal development, human interaction, economic and social benefits, communal meaning and the imprint of the arts experience.

In psychology, long-standing traditions revolve around the construction of multidimensional indices and scales of basic human values, seen as beliefs connected with emotions, motivations and dispositions to act. Schwartz (Citation2006, pp. 139–141) describes tensions such as autonomy vs. embeddedness, egalitarianism vs. hierarchy, and mastery vs. harmony as the ‘bipolar dimensions of culture’ that give the cultural profile of a society, but notes how ‘culture joins with social structure, history, demography, and ecology in complex reciprocal relations that influence every aspect of how we live’. Socio-cultural psychology and cultural ecology have explored contextualised and organic approaches to the study of the development, transmission and transformation of values. These approaches are centred on the synergetic relationships and everyday intersections between human activities and interactions, their wider contexts, and individuals’ characteristics (Bronfenbrenner Citation2005, Tudge et al. Citation2012).

Complexity, ecosystems, and cultural ecological theorists emphasise the complex interactions through which values are enacted. Rather than attempting to capture them in aggregate measures and indicators, they use the notions of dynamic configuration and equilibrium to describe ecologies of cultural value/s. Ideas derived from the natural sciences, such as partial causality, emergence, interpretation, non-linearity, holism, probability and uncertainty (Osberg and Biesta Citation2010, Geyer Citation2012), have been proposed as theoretical tools that may be consistent with the nature of inquiry in the arts and the humanities (Parker Citation2008).

Sharpe (Citation2010, p. 77) finds inspiration in ecological thinking, cognitive science, actor-network theory, and phenomenology to explore ‘the dilemma between money and meaning’ currently besetting cultural policy. He argues that cultural economic activity, particularly in monetary terms, is only one part of the ecosystem of cultural life. Value arises from dynamic patterns of making and sharing meaning in an ecosystem. It is ‘enacted’, or ‘brought forth’ (Varela et al. Citation1993) from a background of meaning or action, by a complex system, through its specific history of structural coupling with the environment.

Notions of fluidity, heterogeneity, and transitory configurations (Little Citation2012) underpin literature that draws on Deleuze and Guattari’s (Citation1988) metaphor of ‘assemblage’ to resist ‘organismic’ metaphors of social ontology (DeLanda Citation2006, p. 8). In a cultural assemblage, relationships are transient and contingent, rather than stable and necessary; the ‘parts’ don’t just make sense relative to the ‘whole’, but interact in meaningful configurations at different levels and in different ‘assemblages’. Thus, while an aggregate picture of the whole may be beyond reach, disentangling the interactions and the components of assemblages of cultural value is still worth the while.

As illustrated by the literature reviewed above, ‘cultural value’ covers a textured family of concepts and practices that is ripe for fuller articulation, but eludes a single definition. A mixture of ‘contestable’ and ‘contested’ concepts (Gallie Citation1955–1956) is used in the literature to explicate the notion of cultural value, including ‘art’, ‘social justice’, ‘democracy’, and ‘religion’ (which are, incidentally, the key examples originally used by Gallie to illustrate his notion of an ‘essentially contested’ concept). Following Gallie, thus, value and culture (and by extension, cultural value) are concepts that are appraisive; internally complex; variously describable; persistently vague and open to modification in the light of changing circumstances; and used ‘both aggressively and defensively’ by the various parties involved in aesthetic and political arguments over their usage, and particularly over their partial operationalisations for performative assessment purposes.

Additionally, work in the three clusters of literature discussed above acknowledges the conceptual relevance to the analysis of cultural value of interaction, intersubjectivity, networks, texture, and flows, and the challenges of transience and fluidity. While their answers to these challenges may diverge, they form a theoretical space that enabled us to develop the initial conceptual and methodological framework of this study and to interpret its findings.

Table 1. Sample description.

Approach

Design and sampling

Our exploratory aims prompted a nested multiple case study research design. The selection of cases involved decisions on four levels: disciplines; higher education institutions (HEI); research projects and initiatives; and individual respondents. At all levels, we sampled for variation, because we wanted to unpack the multiple conceptual facets that would enable us to understand cultural value.

| (1) | Areas of research. By combining the definitions used in REF Citation2014 (Panel D) and RAE 2008 (Panels M-N-O), we selected the following areas: art and design; classics; English language and literature; history; modern languages and linguistics; music, drama, dance and performing arts; library and information management; philosophy; theology and religious studies. On advice from the interviewees, during fieldwork we added to the sample museum studies, archaeology, and digital humanities. | ||||

| (2) | Research units. Using THE (Citation2008), we identified research-intensive institutions (notwithstanding selective submissions by institutions, which limit the use of this table as a sampling tool). A purposive initial sample and a reserve sample were constructed by randomly selecting two institutions from every decile of the ranked table. The institutions were then classified and the sample was adjusted by type of institution (historic types plus specialist) (Boggs Citation2010, Blass et al. Citation2012). We added to the resulting sample two institutions from Scotland and Wales. Using the RAE 2008 sub-panel tables, the units with the highest percentage of 4*research in the disciplines listed above were selected from each institution. If a unit declined participation, we replaced it with its nearest match from the reserve sample. The final sample includes 15 units in 12 disciplines (Table (A)). | ||||

| (3) | Research projects and initiatives. The heads of department and directors of research in each unit were asked to suggest recent (since 2008) research projects in their institution, which they judged as examples of cultural value. Fourteen research projects were identified. From the research units and projects sampled, we identified (through a snowball procedure) further participants: 10 partner organisations (museums; galleries; historic houses; archives; industrial heritage); 8 cross-sectoral value-oriented initiatives (knowledge exchange, creative entrepreneurship, commercialisation, cultural development, executive education, digital resources, public humanities, and a festival); and 2 user or beneficiary organisations (NGO; community organisation). | ||||

| (4) | Individual respondents. In each research unit we interviewed heads of department/school (HoD), directors of research (DoR), research managers, knowledge exchange (KE) officers, project principal investigators (PI) and initiative coordinators (CI). Through the PIs and coordinators, we identified partners, users and beneficiaries of research. Table (B) summarises the demographic characteristics of the 69 interviewees. | ||||

Fieldwork

Fieldwork (in spring 2014) combined semi-structured interviewing with network mapping. The hour-long, face-to-face (some via Skype) interviews explored participants’ interpretations of cultural value from research and their experiences of enacting, promoting and demonstrating such value.

The project- and initiative-based interviews were followed by a mapping activity, which led to the co-construction and validation of qualitative network maps of the links of these projects and initiatives with entities external to the research unit (Oancea, Citation2011). The maps, drawn collaboratively by the participant and interviewer using an outline protocol, were weighted by participants’ subjective ratings of the nature and intensity of flows between academic and non-academic environments. They were subsequently re-drawn and colour-coded in digital format by the researcher. Where more than one respondent had been interviewed about the same project, their maps were compared and merged. The maps were sent to the interviewees for feedback and validation.

The study had ethical clearance from the University of Oxford.

Analysis

The analysis explored the conceptual threads that are the warp and weft of cultural value discourses in the arts and the humanities. We therefore favoured variation and richness of data over representativeness and generalisability; theory-generation over theory-verification (Punch and Oancea Citation2014). The analysis involved the following stages:

| (1) | Preparation. Full transcripts of the audio files were imported in NVivo. The network maps were checked, merged, digitised, and validated. | ||||

| (2) | Data immersion. Three coders read through the data and identified broad themes connected with the research question. They generated an initial coding scheme consisting of topics, such as ‘defining cultural value’, ‘public debates about cultural value’, ‘means of demonstrating value’, ‘research environment’, with operational definitions. | ||||

| (3) | Topic-based coding. The three researchers piloted the coding scheme independently on the same transcripts. The reliability of their coding was checked and discussed qualitatively during calibration meetings. The coding scheme was then refined and the over 0.5 million words worth of interview data (split between the three coders) were allocated to the broad topics, grouped in clusters. | ||||

| (4) | Data-emergent coding. We extracted the full data coded in each cluster. Two researchers independently carried out a fresh round of in-depth coding by hand within each cluster, resulting in extended code books, checked across coders. In parallel, the network maps were analysed for structure (nodes and relationships), flows (between research and other communities) and content (qualitative commentary by participants). | ||||

| (5) | Thematic integration. The data-emergent codes were organised thematically and data were extracted for each theme to generate grounded descriptions. The analysis was then integrated with that of the network maps. Two main themes were thus generated, roughly labelled ‘the economy of valuing’ and ‘the ecologies of values’. The draft report was offered for comment to participants who had expressed an interest. | ||||

Interpretations of cultural value/s and valuing

We asked our interviewees what ‘cultural value’ from research might mean to them. As illustrated below (the references in square brackets are to individual interviews), their answers support the notion that cultural value is a site for conceptual and political contestation. All participants described the attempt to define or capture cultural value as ‘difficult’, ‘hard’, ‘complicated’, ‘tricky’ or ‘problematic’, or the concept itself as ‘complex’, ‘slippery’, ‘fluid’, ‘nebulous’, ‘elusive’, ‘fugitive’, ‘diffuse’, ‘intangible’ or ‘broad’ (and similar terms). The following participants argued that comprehensive definitions and objective measures of cultural value were not just hard to produce, but untenable:

Measuring the value of something is almost impossible …, we can’t talk about the value per se because that's not an objective criterion. [PI, information studies]

Interest in the fine grain of practice and reception … is much more intimate, is much more fugitive, much more elusive but actually much more powerful than any ideologically motivated construct of cultural value. [PI, museum studies].

If you try to create specific criteria … it becomes less flexible. Flexibility is really quite important when we’re thinking about something very broad like cultural value. [HoD, classics]

Furthermore, each component of the concept is a contested term in its own right. The use of the term ‘culture’ may depend on who is defining it and their particular perspectives or ideologies, while the term ‘value’ is made ‘problematic’ by its attachment to economic exchanges. For example:

Culture is ‘one of the most complicated things to pin down’ [CI, initiative]

The term ‘value’ is problematic, because it’s quite hard to move it away from an economic context. [PI, drama]

Not just economic, not just financial, but also cultural, social, educational: there are many understandings of what value creation might be. [partner, digital humanities].

The lack of a ‘common vocabulary’ [partner, digital humanities], shared ‘terminology’ [user, arts and design] or ‘repertoire’ [DoR, music] to sustain conversations about cultural value is compounded by the import of terms, such as KE and impact, from other fields, including science and medicine [KE champion, drama] and business [mentioned in three initiative interviews]. Thus, ‘cultural value’ may end up as a placeholder for ‘what’s left over’ ‘once you subtract the financial, once you subtract the policy, once you subtract the legal’ [HoD, philosophy].

Finally, the arts and the humanities are criss-crossed by many voices, all vying for expression. Thus definitions of cultural value are embedded in particular power relations:

I am more interested in (…) how could we understand this process and act and performance of definition as revealing different power relations and different stakes in what and how cultural value might be pinned down. [CI, initiative]

I’m interested in the way cultural value is rendered and what it represents in terms of power in society. Conversely, I am also interested in what is not understood as culture. [PI, multidisciplinary].

Non-restrictive notions of cultural value would cover different activities and include different perspectives – researchers, participants, partners, users and beneficiaries of research:

If there is a cultural value, I think it’s got to involve a lot of people, and it’s not something that you can compartmentalise and cut up into discrete lumps. It’s about an engagement with the wider culture … That’s a very holistic, general thing. [PI, philosophy]

‘The word “cultural” begs an awful lot of questions, doesn’t it? (…) you’ve got to think in terms of a spectrum of cultural value.’ A ‘fluid’ concept of cultural value would be ‘more receptive to the variety of different activities that can go on within a faculty.’ [DoR, English].

Such holistic, fluid and receptive vocabulary may offer a counterpoint to the emphasis on economic value in public policy, thus stimulating more fundamental and nuanced discussions in research policy and governance. The following participants argued that the discourse of cultural value may prompt researchers to think differently about their own work, with practical, administrative and political implications:

(Cultural value) does at least push us in the direction of thinking about what value is and what the sources of value might be. [PI, English].

By being explicit and saying “Well what is cultural value?”, it’s making colleagues think about it…, how they already contribute to it and what they could do in the future. So a lot of this is making explicit what colleagues already do. [HoD, modern languages]

However, while keenly aware of current policy and political discussions around valuing research and of the institutional mechanisms created in response to REF impact demands, the interviewees challenged any attempt to produce all-encompassing constructs of value that are not ‘sensitive to subject-specific boundaries’ [HoD, philosophy]. For example, respondents from philosophy, modern languages, English, history, religious studies and classics emphasised how the cultural value of research for non-university groups is difficult to predict in the design stage of a project, as it may emerge throughout the process, sometimes after several years of research. They also argued that cultural value is not amenable to precise measurement and quantification.

Participants from music, drama and performing arts, and arts and design described themselves as naturally oriented to an audience and to professional practitioners, including to ways of articulating value outside academia. Their view of research as intertwined with practice in a constant feedback cycle called into question the boundaries between ‘research’ and other forms of creative practice.

Finally, respondents from museum studies, library and information and digital humanities emphasised their user-orientation (‘naturally … part of the scene for us’ – PI, information) and their capacity to mobilise new technologies in order to enrich and re-signify the value of the arts and humanities.

Notwithstanding these caveats, across the corpus of data collected we identified several generic uses of the term ‘cultural value’ in relation to research:

| • | articulating, expressing and intensifying the value of cultural works, organisations and activities for society and individuals; | ||||

| • | shaping the processes involved in the evaluation and critique of cultural works, activities and policies; | ||||

| • | valuing the diversity of cultures and cultural practices; and | ||||

| • | countering narrow views of the value of the arts and humanities. | ||||

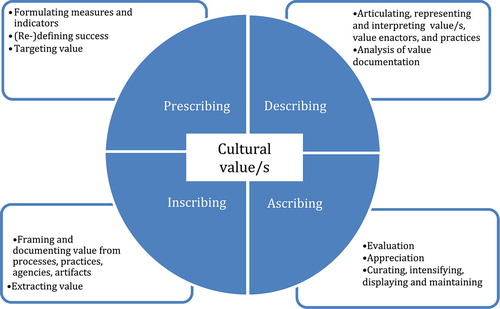

Further exploration, through interviews and network maps, of these multiple meanings and of the practices associated with them at individual and institutional level brought to the fore two interwoven layers in the understanding and practice of cultural value. First, our data show diverse and nuanced conceptions of how culture connects with different fields and modes of inquiry. We describe these connections below as ecologies of cultural value. Second, the interviews elicited accounts of how cultural value may be defined, produced, distributed and consumed within and across institutional bounds; that is, ‘the various, different ways in which people try to understand the building of value/s’ [DoR, music]. We describe this below as the economy of cultural valuing.

Ecologies of cultural value

The arts and the humanities are both ‘fields’ of inquiry and practice, and forms of scholarship or ‘roads of inquiry’ (Johnston, in Belfiore and Upchurch Citation2013, p. 137). As fields, they are centrally concerned with the human condition and with being and becoming human. The following quotes illustrate this point through the accounts of two participants from different disciplinary and organisational backgrounds:

Humanities research is about people’s understanding of humanity and who they are and how they fit in with the world … Arts and humanities help us live with that. [PI, information]

We believe in the fundamental human right to express themselves in their knowledge, in using their mind, intellect, learning, expressing, creating, all those things are fundamental to being human. [manager, humanities/social sciences]

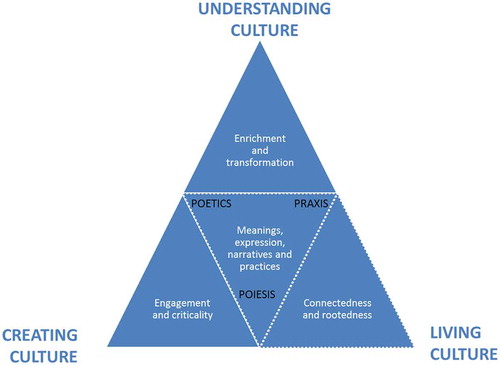

As paths to inquiry, the arts and humanities combine action (praxis) with craft (poiesis) and with meaning and expression (poetics). Meaning, expression, narrative and practice, combined and recombined in experience through the inter-action between self and others, were core themes in our analysis of participants’ descriptions of the arts and the humanities. The notion of culture connects with this core through experiences of understanding, of creation, and of living, which give engagement with culture its ‘long term value, just in terms of richness of human experience’ [HoD, information]. The following respondents make such connections explicit:

There is a cultural value for the research produced in terms of getting a deeper understanding of our place in the world, and our place in our culture, and perhaps the contingencies of our cultures. [PI, philosophy]

The cultural value is to persuade people to be vigilant about their own cultural rights, and I see that as being fundamentally important. [PI, history]

If you take away the arts and humanities you are left with mechanical parts of life (…) In order to ‘Live’ with a capital L, you wrap yourself in culture, in social interaction, in language, and beautiful objects, and that’s the difference between existing and living. [partner, museum]

To be able to express your body, and to express what other people’s bodies and bodies in general feel, is something that is quite valuable. [beneficiary, drama]

Quality of life and taste (…) we don’t have a translation for bildung, but a sense of being better in some way for your aesthetic experience. [PI, music]

Figure integrates the codes and categories generated through the analysis of the ‘meanings of cultural value’ cluster of data, organised around the experiences of understanding, living and creating culture.

While these categories are analytic (e.g. ‘understanding’ covers codes for cognition, self-knowledge, sense-making, etc.), they were also terms that the participants used many times without specific prompting in the interviews. For example (as counted in NVivo), in the interview with a non-academic partner to a project in history, the word ‘understand/ing’ comes up 48 times and in another interview, with a PI in philosophy, 28 times. ‘Creating’ (and stemmed words) is mentioned 23 times in an interview about an arts entrepreneurship initiative, and 19 times in that with the DoR in an arts institution; while multiple references to ‘living’ and ‘life’ were made in interviews from all the disciplines and groups studied (22 times in the interview with a PI in drama). A PI in English mentions each of these terms 9 times.

The interviewees resisted the temptation to over-tighten the term ‘cultural value’; their accounts gave a sense of openness, fluidity, and conceptual assemblage, while also echoing longer-term discussions in cultural policy and practice (Selwood Citation2002). Thus, while the themes below are grounded in our interview data, they do not amount to a fully-fledged ‘definition’ of cultural value as articulated by our participants.

Personal and interactional enrichment and transformation

The contribution of the arts and humanities, as described by our interviewees, ranged from ‘(cultural) knowledge’ [PI, religious studies; HoD, English; HoD, classics; partner, classics; initiative, multidisciplinary; partner, museum], ‘(freedom of) expression’ [PI, history; partner, history; initiative, arts; PI, arts; HoD, English; also all beneficiary interviews, drama], ‘depth of thinking’ [partner, classics] and ‘widening of intellectual horizons’ [HoD, English], to ‘release’ [beneficiary, drama/ music], ‘escape’ [beneficiary, drama/arts], ‘coping in traumatic situations’ [KE, drama], and ‘health’ or ‘therapy’ [CI, festival; dean, art; two beneficiaries and PI, drama], as well as ‘enjoyment’ and ‘pleasure’ [two partners, museum; beneficiary, drama; PI, archaeology; HoD, classics; PI, architectural history]. The corollary of ‘enrichment’ [beneficiary, drama; dean, arts; PI, library and information] and ‘transformation’ [beneficiary, drama/art; initiative, multidisciplinary; KE champion/PI, drama; PI, philosophy] is personal ‘growth’ [partner, history] and ‘well-being value’ [beneficiary, art]. Enrichment and transformation through research and education are thus deeply connected to being and becoming human, and making sense of human action and experience in different material, social and cultural environments.

Connectedness and rootedness

The views clustered around ‘living culture’ emphasise the importance of arts and humanities research in cultural ‘interpretation’, ‘re-contextualisation’, ‘reconstruction’ and ‘imagination’ [partner, history; partner, museum; PI, heritage; PI, English; partner, classics] or in ‘understanding different cultures’ (PI, classics); in ‘enhancing empathy, compassion and relationships’ [PI/KE champion, drama]; but also in ‘social cohesion’, ‘community coherence’ [PI/KE champion, drama; partner, classics], cultural ‘security’ [beneficiary, drama; PI, history], and a sense of ‘(cultural) connection’ with others, with the past, with place and landscapes [PI, English; initiative, arts; partner, history; PI, arts; PI, drama; beneficiaries, drama/art; PI, philosophy]. The boundaries of the collective range from a minority group [PI and beneficiaries, drama/arts], to a locality [PI, initiative and dean, all arts; HoD, archaeology; partner, museum; partner, classics/heritage; partner, drama; PI, heritage; PI, philosophy; PI, library and information], to ‘different cultures’ [PI, history; PI, philosophy; PI, classics; partner, museum; PI, drama], to a nation or specific society [PIa,b, history; partner, museum; PI, drama; PI, music; PI, archaeology] and beyond, to the international or global context [dean, arts; PIa,b, history; partner, history]. By this sense of ‘connection’ [PI, English], ‘rootedness’ [manager, interdisciplinary] and ‘belonging’ [HoD, archaeology; PI, drama], the arts and humanities return something valuable to society, whilst continuing to sustain their key perennial project of understanding humanness.

Engagement and criticality

The ‘creating culture’ sub-theme encompasses aesthetic, political, economic and social connotations of the term. Research in the arts and the humanities plays an important role in enabling, as well as problematizing, individual and collective ‘(cultural) access’ [HoD, English; HoD, classics; partner, classics; PI, philosophy; initiatives, arts; partner, history; partner, museum; PI, drama; PI, information; PI, history]; opportunities for cultural expression and ‘interaction’ [PI, digital humanities]; ‘engagement’ with a diversity of cultural works, practices and institutions [PIa/b, philosophy; PI, drama; PI, heritage; partners a/b, museum; initiatives a/b, multidisciplinary; DoR, arts], including productive engagement with cultural or creative industries [dean, arts; PI/KE champion, drama; PI, drama; PI, heritage; initiative a,b, arts; DoR, arts]; ‘generating new cultural forms’ [dean, arts]; and participation in wider cultural practices [PI, library and information; dean, arts]. Research teases out the connections between aesthetic expression and appreciation [PI, music; partner, museum; PI, digital humanities; PI, arts], on the one hand, and social change, voice and resistance, on the other. Additionally, the participants suggested that arts and humanities research has a valuable role in ‘democratizing culture’ and ‘strengthening (cultural) identities’ [PI/KE champion, drama], making ‘marginalized’ identities more visible and ‘vocal’ [PI, arts; initiative, multidisciplinary; partner, museum], supporting ‘active citizenship’ [PI, drama] and affirmation of ‘cultural rights’ [PI, history; partner, history], ‘challenging views’ and ‘activating resistance’ [PI/KE champion, drama], and in motivating ‘cross-cultural’ dialogue [PI, history] and ‘appreciating (cultural) difference’ [partner, museum; initiative, arts; DoR, arts; PI, religious studies]. Further sub-themes include the creative industries, creative entrepreneurship, and economic regeneration.

The economy of cultural valuing

The interviewees described elements of a dynamic economy constituted by producers, distributors and consumers of cultural value in different fields and contexts of practice and inquiry. We grouped the activities identified in our thematic analysis of the interviews into four categories: description, ascription, prescription and inscription of value. The sub-themes encompassed by these analytic categories are illustrated in Figure .

Description

Cultural value/s may be generated, framed, performed, and expressed in many contexts. Value is continuously articulated, or described, in and through cultural interactions (Smith Citation1995). As a PI [museum studies] notes, ‘cultural value depends and is enacted through the interaction with the project participants’ and is ‘articulated by institutions past and present’. Such articulations may arise from research, practical and everyday conversations, grassroots activism, performative acts, or political debate. Scholarly inquiry combines the meticulous construction of warrants with systematic attempts to deconstruct them critically. By virtue of these characteristics, research is an important component of social descriptions of value:

It’s rather important to draw some distinctions between creating value and identifying value (…) In the museum, in the gallery, in the department – we identify what is of cultural significance and value. [HoD, humanities]

The more professional and experienced and the more you can frame that [exchange of value], the better the value is understood. [enterprise, arts].

A tension is visible, sometimes within a single interview [e.g. PI, drama; manager, multidisciplinary] between the discursive functions of ‘cultural value’ to either co-opt research into instrumentalist ‘agendas’, or to counter them. On the one hand, ‘market’-driven and ‘political’ [enterprise, arts; KE champion, drama; PI, drama] uses of the concept may prioritise measures of impact with a ‘whiff of instrumentalism’ [DoR, modern languages; also, DoR, arts]:

Institutions will echo a top-down rhetoric in order to make a case for resources but it’s not how people describe what they do. [PI, museum]

Sometimes there’s a strong tension between the cultural value side and the commercial side … I wouldn’t say they were necessarily intrinsically opposed but their timescales are often difficult to map across. [partner, heritage]

Academics can come up with a way of articulating that value that isn’t a quasi-instrumental/scientific way of doing it. I know that’s what is often done because it is x amount of money and you want to see what are the outputs for that money; but I don’t think that’s the best way of articulating what culture actually does for society. [PI, library and information]

On the other hand, the notion of ‘cultural value’ may also fulfil a discursive function to ‘protect’ [manager, multidisciplinary] arts and humanities research against the reduction of value to purely monetary terms or to short-term impact measures:

How do we square what is intrinsic, and what should be intrinsically valued, with instrumental needs to demonstrate that value? And I suppose [funding body] are trying very hard to do that, on the sector’s behalf … to protect the intrinsic through the instrumental. [manager, multidisciplinary]

We have to talk in an instrumentalist language in order to get a seat at the table for local strategy, we have to talk in a business language (…) as a means to an end to get across the more intrinsic point that culture is a good thing. [coordinator, heritage initiative]

Ascription

Cultural valuation involves contextualised attributions, or ascriptions, of value; three participants introduced and explained the term:

Ascribed value is ‘not the value, but it’s the way the value is shown to be meaningful’. [user, art and design]

You can come at cultural value from all sorts of different angles: one is the value that is attributed or ascribed to it by its audience, one is the value that you see it as disseminating or carrying, and I suppose I’m seeing it as a mixture of the two. Those things are all very hard to measure. [PI, art history]

Ascribing value to anything in terms of culture is very, very difficult because that implies emotional well-being type, psychological-type areas, which it is extremely hard to judge. [PI, information]

Ascriptions of value involve subjective judgment and intersubjective evaluation within specific institutional and societal contexts, from formal evaluation processes, costing, and peer judgement, to everyday expressions of preference. Value may be ascribed through, for example, rating, comparison, selective ‘display’ [PI, English], or ostension (Eco Citation1976). As a result, particular practices, works, agencies, networks, spaces and processes may be re-described as bearers of value in these contexts:

It’s all about the context in which value is given … Instead of trying to define it as something with these values, we need to understand the way in which it’s produced, who produces it and why. [PI, multidisciplinary]

It’s an expression of power dynamics in our society, so what’s given value, what value’s attached to it depends on the dominant discourse. I don’t think any of those are intrinsically valuable, so it’s all contextual. [CI, multidisciplinary].

There’s a direct relationship between the money that went in and the value placed by society on that cultural event and the objects within it; and the statistics and the evaluating process (are) the mediation between the two. [user, art and design].

Although headcounts and monetisation may play a role in political discussions about research, overly simplistic economic indicators were rejected by all respondents as measures of its value. For example, ‘I don’t think it’s appropriate – or even useful – to think of it economically, in valuative terms’ [HoD, English]. However, ‘proper validated economic models’ and techniques [DoR, arts] were recognised, particularly by interviewees connected with entrepreneurial and public-oriented activities [PI, heritage initiative; initiative a,b, arts; initiative, multidisciplinary; partner, heritage; PI, music], as appealing and effective in making a case for the humanities and the arts. For example:

We need strong people, making strong economic cases, and I think we need to get quite militant about this. [initiative, multidisciplinary]

The multiplier effect on the money you’d hopefully get in through tourism is pretty good and also (…) it’s our research that’s directly contributing to small, medium enterprises and local business growth. (…) Does the interest in the commercial angle denigrate us as scholars (…) or is the process of trying to market ideas and market stories actually very useful? [CI, heritage initiative]

Talk about visible income raising is (…) a very naïve way of understanding money; there is a lot of invisible, unquantifiable benefit which would cost money if you put a price tag on it … a social benefit which translates into monetary terms. [KE champion, drama]

Yet, even those who saw the merits of economic arguments were prepared to do so only as long as the uses of financial indicators were restricted to areas naturally amenable to monetisation (leaving other areas to other forms of value articulation), and as long as the transactional and political nature of using financial arguments to justify public support for research in the arts and the humanities was made explicit and subjected to challenge.

Inscription

There is a ‘natural’ [PI, library and information] impulse among scholars in the arts and the humanities to document and archive sensitively and systematically – what we label ‘inscribe’ – the processes, values, outcomes and reception of inquiry and creative practice. This impulse is quite distinct from the ‘obsessive auditing of everything’ [PI, English] that may have been prompted in some institutions by external research assessment requirements:

We want to document, capture, we want to archive, we don’t want this to be the ephemeral thing that arts practices often are. [PI, performing arts]

Capturing and articulating narratives of values in a systematic way: research has been doing it for decades. [PI, cultural studies]

Cultural value from research may be documented as it unfolds, for example ‘woven into a narrative’ or re-told as ethnographic case studies [PI, drama; partner, heritage; initiative, multidisciplinary; DoR, arts]. It may also be deliberately ‘extracted’ [enterprise, arts] through measures of ‘audience impact’ (including snapshots and before-and-after measures) [PI, library and information; partner, museum], ‘reception’ [HoD, classics; manager, humanities], ‘public engagement’ [PI, classics; partner, heritage; partner, museum], ‘transactions’ and interactions [partner, museum; PI, digital humanities; PI, library and information; PI, drama; enterprise, arts], media ‘resonance’ [head, English], ‘commercial success’ [HoD, English; HoD, philosophy; enterprise, arts; partner, heritage; coordinator, heritage initiative], or practical or ‘public application’ [dean, arts; DoR, music; HoD, information; enterprise, arts; PI, drama].

The inscription of value through records is related to the descriptions and prescriptions that constitute its axiological environment. For example, some of the respondents [HoD, PI, both library and information; PI, drama; PI, English; initiative, arts] argued that channelling the impulse to document towards externally-defined metrics and prescriptive definitions of ‘research performance’ means that ‘the wrong approach is being taken in seeking to record things that aren’t really recordable’ [PI, English].

Prescription

Particular articulations of cultural value may be officialised or institutionalised into organisational and national targets, performance measures and indicators, criteria and thresholds of success. Through officialisation and institutionalisation within particular structural relationships and dynamics of power, articulations of value may turn into normative prescriptions.

The majority of the interviewees commented on the role of research assessment exercises and of grant competitions in shaping the language and methods through which researchers are expected to demonstrate the value of their work. Those participants who had been involved in REF Citation2014 preparations explained how the writing of an impact case study had involved a reconstruction of what the researchers had done throughout the years and a ‘retrospective’ articulation of the contribution of their work in line with the ‘prescriptions’ of the exercise [manager, humanities; DoR, arts; KE champion, drama]. Even beyond the case studies, the measurement and reporting of impact for performance management purposes, however sophisticated or sympathetically conducted, was still likely to affect the fine-tuned ecologies of practice and inquiry that enable the humanities and arts to make their specific contributions to knowledge and society:

When we’re told that we have to have impact we want to run a mile or more, because that means we’ve got to influence religions, we’ve got to change the stuff that we’re out there to observe and analyse, and so on. Our job historically we’ve said is understanding, analysing, discussing. [HoD, religious studies]

The art historian, like the theologian (…) is there to do that analytical critical work, which in a reflexive and articulate way might have cultural value down the line. Indeed, I passionately believe it does. But the capturing of it is a very dangerous thing, because once you capture a wild bird (…) it ceases to have its place in the ecology. [HoD, humanities]

We have a very regimented target culture, where we have to produce this output, and then do this workshop, and then do this seminar, and its cultural value is the sort of thing that resists … putting in discrete blocks. [PI, philosophy]

Table summarises the concerns and caveats identified in the interviews about attempting to operationalise the cultural value from research into quantifiable indicators of performance.

Table 2. Indicators of cultural value: risks and caveats.

More holistic notions of cultural value may have the potential to avoid co-option into instrumental compliance to policy demands, and to be deployed as a form of resistance to the influence of target- and performance-based governance on the nature of academic work. A partner to an initiative on digital humanities commented on the mismatch between collective, networked processes and current regimes for academic work:

We’re starting to think about these collective types of endeavour more and more in web contexts, which would have potentially more cultural value. But in terms of thinking about how that fits in with individual acknowledgments, scholarly activity, career development, all the other things that we look for in an academic environment, goodness knows.

Conclusions

This study has furthered our understanding of cultural value as a contested concept, beset by philosophical, practical and political tensions. Ecologies of value and economies of valuing were intertwined discursively in our data, but they also clashed occasionally, particularly in relation to the research performance measures shaping higher education activity. The study has also provided insights into the practice, governance and policy of research in the arts and the humanities. The following reflections draw on the data collected and the analytic themes explored.

Accountability and research assessment

A lesson to be learnt from REF Citation2014 is that risk-averse impact reporting can lead to favouring quantitative indicators of short-term reach and outcomes over qualitative accounts of longer-term and collective significance and influence. Narratives of process are key to tapping into the richer, more subtle and longer-term contributions made by research. Clearer messages are needed at all levels of the research governance system so that narratives in qualitative and non-economic terms are not perceived as a risk in accountability contexts.

Infrastructure and governance arrangements for academic work

Two of the initiatives studied agreed to the public release of their non-anonymised network maps. They supported a process-based, ground-up approach to articulating value and engaging with partners from beyond the HE sector. However, current arrangements for academic work and mechanisms for recognition and career progression may need adjustment to sustain the ecology of flows and interactions that is the basis of meaningful engagement and partnerships. In addition, creating and delivering the kind of value-oriented initiatives discussed in this paper requires structural adjustments to modes of work that cut across sectors, organisations and disciplines.

Research practice

This study reminded us of the tight relationships between different aspects of academic practice in the arts and the humanities, including creative practice, teaching, outreach, and research. Management structures that impose too strict boundaries between these practices are likely to be counterproductive in these fields. Even the parsing of research into ‘projects’ on grounds of direct external funding is only meaningful in relation to a part of the scholarship in the arts and humanities. The meaning of ‘project’ can stretch from a short-term, bounded activity, to a career-long endeavour, and to a collective tradition of inquiry. Funding and management arrangements for research need to reflect this diversity.

The value of ‘cultural value’

Cultural value has been offered variously as a solution to bigger debates about the distribution of public funding, the social accountability of academic research, and the relationships between the state and universities. Our respondents were aware both of the merits and of the limitations of these attempts. The richness and reflexivity of their accounts of cultural value and valuing in relation to research, assessment, and wider cultural practices do not support the idea that the sector unreflectively ‘neglects’ and attitudinally resists engagement with these issues (Scott Citation2009, Holden and Balta Citation2012). The fact that our data yielded no single, cohesive articulation of cultural value and no commonly accepted techniques and indicators to measure it is a consequence of the conceptual, practical and political complexities besetting the attempt to use ‘cultural value’ as a straightforward alternative to ‘economic value’ in the arts and the humanities. As a contested concept, cultural value may not settle long-term debates; but it may enrich them through prompting efforts to articulate, challenge and recognise valid arguments and their political consequences.

Notes on contributors

Alis Oancea is an associate professor in the Philosophy of Education at the University of Oxford, where she is also Deputy Director for Research in the Department of Education. She writes on philosophy of research, higher education governance, research policy, research assessment, impact and knowledge exchange, research methods, and disciplinarity.

Maria Teresa Florez-Petour is an assistant professor in the area of Assessment of and for Learning at the University of Chile, Department for Pedagogical Studies, as well as a Research Associate of the Oxford University Centre for Educational Assessment. Her research interests include assessment policies and discourses in connection with history, politics and ideology.

Jeanette Atkinson is a heritage professional with a background in both academic research and heritage practice, working as a Distance Learning Associate Tutor for the School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester. She is also Project Administrator for the Globalising and Localising the Great War Research Network in the History Faculty at the University of Oxford.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the funding support from the AHRC, through its Cultural Value project (grant AH/L005131/1, PI: A. Oancea). We are grateful to the numerous academics and other professionals from a wide range of organisations who gave us so much of their time and insight. We have learned from, and grown through, the conversations with them, which in most cases spilled well beyond the agreed hour. We are also grateful to the parents and the young people who allowed us to get close to their complex and fascinating circumstances and experiences. Prof Ron Barnett, Dr Eleonora Belfiore, Dr Claire Donovan and Prof Donna Kurtz, as members of our Advisory Group, generously shared their knowledge and perspectives. Three research interns to the project contributed to the early literature mapping: Samantha Seiter, Sijung Cho and Kyeonghwa Lee. Due to the confidential nature of some of the research materials supporting this publication, not all of the data can be made accessible to other researchers. Please contact the corresponding author for more information.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adkins, L. , and Lury, C. , eds., 2012. Measure and value . Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Allee, V. , 2008. Value network analysis and value conversion of tangible and intangible assets. Journal of intellectual capital , 9 (1), 5–24.10.1108/14691930810845777

- Andriessen, D. , 2005. Value, valuation, and valorisation. In: S. Swarte , ed. Inspirerend innoveren; meerwarde door kennis . Den Haag: Krie, 1–10.

- Bakhshi, H. and Throsby, D. , 2010. Culture of innovation: an economic analysis of innovation in arts and cultural organisations . London: NESTA.

- Bate, J. , ed., 2011. The public value of the humanities . Jonathan Bate. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Belfiore, E. and Bennett, O. , 2007. Determinants of impact: towards a better understanding of encounters with the arts. Cultural trends , 16 (3), 225–275.

- Belfiore, E. and Bennett, O. , 2010. Beyond the “Toolkit Approach”: arts impact evaluation research and the realities of cultural policy-making. Journal for cultural research , 14 (2), 121–142.10.1080/14797580903481280

- Belfiore, E. and Upchurch, A. , eds., 2013. Humanities in the twenty-first century. Beyond utility and markets . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bennett, T. , et al. , 2009. Culture, class, distinction . London and Basingstoke: Routledge and Palgrave.

- Blass, E. , Jasman, A. , and Shelley, S. , 2012. Postgraduate research students: you are the future of the academy. Futures , 44 (2), 166–173.10.1016/j.futures.2011.09.009

- Boggs, A. , 2010. Evolution of university governance and governance types in England & Scotland. In: S. Miller , ed. The new collection . Oxford: New College, 1–8.

- Bohm, S. and Land, C. , 2009. No measure for culture? Value in the new economy. Capital & class , 33 (1), 75–98.

- Bourdieu, P. , 1984. Distinction: a social critique of the judgement of taste . London: Routledge.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. , 2005. Making human beings human: bioecological perspectives on human development . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Brown, Alan S. , 2006. An architecture of value. Grantmakers in the Arts Reader , 17 (1), 18–25.

- Carnwath, J.D. and Brown, A.S. , 2014. Understanding the value and impacts of cultural experiences. A literature review . London: Arts Council.

- Collini, S. , 2012. What are universities for? . London: Penguin Books.

- Connor, S. , 1992. Theory and cultural value . Oxford: Blackwell.

- De Certeau, M. , 1988. The practice of everyday life . Berkeley: University of California.

- DeLanda, M. , 2006. A new philosophy of society: assemblage theory and social complexity . London: Continuum.

- Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. , 1988. A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia . London: Athlone Press.

- Dewey, J. , 1939. The theory of valuation. International encyclopedia of unified science , vol. II (4). Chicago, IL : University of Chicago Press.

- Donovan, C. , 2009. Gradgrinding the social sciences: the politics of metrics of political science. Political studies review , 7 (1), 73–83.10.1111/psr.2009.7.issue-1

- Donovan, C. , 2013. A holistic approach to valuing our culture: a report to the Department for Culture, Media and Sport . London: DCMS.

- Duelund, P. , 2008. Nordic cultural policies: a critical view. International journal of cultural policy , 14 (1), 7–24.10.1080/10286630701856468

- Eco, U. , 1976. A theory of semiotics . Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Felski, R. , 2008. Uses of literature . Oxford: Blackwell.10.1002/9781444302790

- Frow, J. , 1995. Cultural studies and cultural value . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gallie, W.B , 1955–1956. Essentially contested concepts. Proceedings of the Aristotelian society , 56, 167–198.

- Geyer, R. , 2012. Can complexity move UK policy beyond ‘evidence-based policy making’ and the ‘audit culture’? Applying a ‘complexity cascade’ to education and health policy. Political studies , 60 (1), 20–43.10.1111/post.2012.60.issue-1

- Habermas, J. , 1987. The theory of communicative action , Vol. 2: lifeworld and system. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hazelkorn, E. , et al. , 2013. Recognising the value of the arts and humanities in a time of austerity: report . Dublin: HERA.

- Her Majesty’s Treasury , 2003. The green book: appraisal and evaluation in central government . London: HMT. (updated 2014).

- Hewison, R. , 2006. Not a sideshow: leadership and cultural value – a matrix for change . London: Demos.

- Holden, J. , 2006. Cultural value and the crisis of legitimacy . London: Demos.

- Holden, J. and Balta, J. 2012. The public value of culture. A literature review. European Expert Network on Culture, Barcelona.

- Hutter, M. and Throsby, D. , 2011. Beyond price value in culture economics and the arts . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ivey, B. , 2008. Arts Inc.: How greed and neglect have destroyed our cultural rights . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Joas, H. , 2000. The genesis of values. (transl. G. Morre). Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Klamer, A. , 2004. Cultural goods are good for more than their economic value. In: V. Rao and M. Walton Cultural and public action . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 138–162.

- Knell, J. and Taylor, M. , 2011. Arts funding, austerity and the big society . London: Royal Society of Arts (RSA).

- Latour, B. , 2007. Reassembling the social. An introduction to actor-network-theory . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lee, D.J. , Oakley, K. , and Naylor, R. , 2011. ‘The public gets what the public wants’? The uses and abuses of ‘public value’ in contemporary British cultural policy. International journal of cultural policy , 17 (3), 289–300.10.1080/10286632.2010.528834

- Little, D. , 2012. Assemblage theory . Understanding Society Blog. Available from: http://understandingsociety.blogspot.co.uk/2012/11/assemblage-theory.html.

- Matarasso, F. , 1997. Use or ornament? The social impact of participation in the arts . London: Comedia.

- Matthes, E.H. , 2013. History, value, and irreplaceability. In: Ethics 124 (1), 35–64.

- McCarthy, K. , et al. , 2004. Gifts of the muse: reframing the debate about the benefits of the arts . Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Molas-Gallart, J. , 2015. Research evaluation and the assessment of public value. Arts and humanities in higher education February, 14 (1), 111–126, online-first May 8.

- Molas-Gallart, J. and Tang, P. , 2011. Tracing ‘productive interactions’ to identify social impacts: an example from the social sciences. Research evaluation , 20 (3), 219–226.10.3152/095820211X12941371876706

- Normann, R. and Ramirez, R. , 1993. From value chain to value constellation: designing interactive strategy. Harvard Business Review , 71 (4), 65–77.

- Nussbaum, M.C. , 2010. Not for profit. Why democracy needs the humanities . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- O’Brien, D. , 2010. Measuring the value of culture: a report to the Department for Culture Media and Sport . London: DCMS.

- Oancea, A. , 2011. Interpretations and practices of research impact across the range of disciplines. Report . Oxford: Oxford University.

- Osberg, D. and Biesta, G. , eds., 2010. Complexity theory and the politics of education . Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Parker, J. , 2008. What have the humanities to offer 21st-century Europe?: reflections of a note taker. Arts and humanities in higher education , 7, 83–96.10.1177/1474022207080851

- Plumb, J.H. , 1964. Crisis in the humanities . London: Penguin Books.

- Punch, K. and Oancea, A. , 2014. Introduction to research methods in education , 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Ramirez, R. , 1999. Value co-production: intellectual origins and implications for practice and research. Strategic management journal , 20, 49–65.10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0266

- Rancière, J. , 2004. The politics of aesthetics . London: Continuum.

- REF , 2014. Research excellence framework 2014: overview report by Main Panel D and sub-panels 27 to 36 . Available from: http://www.ref.ac.uk/media/ref/content/expanel/member/Main%20Panel%20D%20overview%20report.pdf [Accessed 19 Oct 2015].

- Rescher, N. , 2004. Value matters: studies in axiology . Frankfurt: Ortos verlag.10.1515/9783110327755

- Schwartz, S.H. , 2006. Basic human values: an overview . Available from: http://segr-did2.fmag.unict.it/allegati/convegno%207-8-10-05/schwartzpaper.pdf [Accessed 27 October 2015].

- Scott, C. , 2009. Exploring the evidence base for museum value. Museum management and curatorship , 24 (3), 195–212.10.1080/09647770903072823

- Selwood, S. , 2010. Making a difference: the cultural impact of museums . London: NMDC.

- Selwood, S. , 2002. Measuring culture. Spiked culture , 30 December. Available from: http://www.spiked-online.com/newsite/article/6851#.VieU18tdGAg [Accessed 21 October 2015].

- Sharpe, B. , 2010. Economies of life: patterns of health and wealth . Axminster: Triarchy Press/ International Futures Forum.

- Smith, B.H. , 1995. Value/ evaluation. In: F. Lentrucchia , and Th. McLaughlin , eds. Critical terms for literary study . 2nd ed. Chicago, IL : University of Chicago Press, 177–185.

- Snow, C.P. , 1959/1998. The two cultures . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Snowball, J.D. , 2008. Measuring the value of culture. Methods and examples in cultural economics . Berlin: Springer.

- Snowball, J.D. and Webb A.C.M. , 2008. Breaking into the conversation: cultural value and the role of the South African National Arts Festival from apartheid to democracy. International journal of cultural policy, 14 (2), 149–164.

- Spaapen, J. and van Drooge, L. , 2011. Introducing ‘productive interactions’ in social impact assessment. Research evaluation , 20 (3), 211–218.10.3152/095820211X12941371876742

- Stenhouse, L. , 1981. What counts as research? British journal of educational studies , 29 (2), 103–114.10.1080/00071005.1981.9973589

- Staricoff Lelchuk , and Rosalia , 2004. Arts in Health: A review of the medical literature . London: Arts Council England.

- Stiglitz, J. , Sen, A. , and Fitoussi, J.-P. , 2009a. Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress . Available from: http://www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr/.

- Stiglitz, J. , Sen, A. , and Fitoussi, J.-P. , 2009b. The measurement of economic performance and social progress revisited . Available from: http://www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr/.

- THE (Times Higher Education) , 2008. The times higher education table of excellence . Available from: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/sites/default/files/Attachments/THE/THE/18_December_2008/attachments/RAE2008_THE_RESULTS.pdf [Accessed 4 November 2015].

- Thrift, N. , 2008. Non-representational theory . Abingdon: Routledge.

- Tudge, J.R.H. , Piccinini, C.A. , Lopes, R.S., Sperb, T.M. , Chipenda-Dansokho, S. , & Freitas, L.B.L. (2012). The cultural ecology of human values. In: A. Branco & J. Valsiner (Eds.), Cultural psychology of human values (pp. 63–83). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishers.

- Varela, F.J. , Thompson, E. , and Rosch, E. , 1993. The embodied mind: cognitive science and human experience . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Vuyk, K. , 2010. The arts as an instrument? Notes on the controversy surrounding the value of art. International journal of cultural policy , 16 (2), 173–183.10.1080/10286630903029641

- Walsh, V. , Dewdney, A. , and Dibosa, D. , 2012. Post-critical museology: theory and practice in the art museum . London: Routledge.

- Waterman, S. , 1998. Carnivals for elites? The cultural politics of arts festivals. Progress in human geography , 22 (1), 54–74.10.1191/030913298672233886

- Williams, R. , 1958. Moving from high culture to ordinary culture. In Convictions , ed. N. McKenzie . London: MacGibbon & Kee, 24–34, Convictions .

- Zuidervaart, L. , 2011. Art in public. Politics, economics, and a democratic culture . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.