ABSTRACT

Focusing on the online fandom of a Thai Boys Love (BL) drama in Japan, called tai-numa, this exploratory study examines its background, fan practices and experiences, and negotiations between fandoms and the mass media and within the fandom. Through interviews with 19 fans active in the fandom, which was shaped by external and internal factors, such as mediascape, characteristics of consuming BL, and the global pandemic, this research argues that the fandom is a transnational, transcultural, and trans-subcultural contact zone, enabling fans to create, learn, reflect, negotiate, and update each other’s values. Fandom activity was facilitated because it was equal and non-hierarchical, allowing for the engagement of a heterogeneous mix of fans from different subcultural backgrounds, and it offered a sense of simultaneity. Through fan voice and discussion, this paper suggests the potential impact of fandom activities on real life and what is needed for such fandoms to be established and sustained.

Introduction

This exploratory study examines how fans consume Thai Boys Love (BL) dramas in Japan, how they construct their fandoms on the Internet, and what practices and negotiations are occurring. Global cultural flows are driven by political and economic state powers and the linguistic hegemony of the English language. Moreover, US popular culture has influenced East Asian popular culture through partnerships with East Asian producers (Huat Citation2004). At the same time, non-US and non-English cultural products without political, economic, and cultural advantages face major barriers when entering foreign markets, as global distribution network systems are not seamless (Lee Citation2016). In this context, while mediated by global media such as YouTube and Netflix, culture is also disseminated globally, with a South Korean drama getting 110 million views on Netflix in 2021 (B.B.C. News Citation2021). Except for the South Korean boom in Japan, which began in earnest in the 2000s, post-war Japan was essentially an exporter rather than an importer of pop culture.

This asymmetry also exists in transcultural exchanges between Japan and Thailand. While Thai TV dramas have made their way to Chinese TV channels and gained interest in many Southeast Asian countries, such as Vietnam, Cambodia, and the Philippines, in the past two decades (Jirattikorn Citation2021), Thai cultural content found in Japan was limited to a few films and novels, and the general awareness of Thai pop culture was low.

This trend changed with the emergence of tai-numa, a cyber-fandom of Thai BL drama lovers that formed on Twitter during Japan’s nationwide ‘stay-at-home’ period at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Tai-numa literally means Thai swamp, where ‘swamp’ is widely used in Japanese otaku culture both as a verb and a noun, as the metaphor to describe the fact that once you get hooked, it’s difficult to get out. It usually refers to both the corrective fandom of Thai BL series and the situation where fans devote themselves to Thai BL contents. It was caused by a viral tweet (now deleted) on Thai BL dramas, beginning with ‘Dear Fujoshi (‘a self-mocking label that transforms a polite term for “women and girls” into a novel term meaning “rotten girls/women”’ (Welker Citation2022b: XIII)), please watch Thai BL drama’. This led to the spread of Thai BL dramas on YouTube, mainly the popular drama 2gether on GMMTV at the time, among the BL-loving population. Subsequently, Thai culture was broadly introduced in Japan, mostly by existing mass media through the acquisition of distribution rights, YouTube-distributed content became unavailable due to geo-blocking, fan events were held, and features appeared in magazines and other two-dimensional media.

In the global distribution of culture, the environment surrounding cultural fandom is ever-changing; diverse and specific digital technologies greatly assist consumers in participating in productive activities around cultural products, and fans have become powerful players rather than just consumers and recipients of culture (see Green and Jenkins Citation2011; Jenkins Citation2006, Citation2021). Audiences are also players and interacting critics in the distribution of culture (Ross and Nightingale Citation2007); voluntarily engage in cultural and linguistic mediation, such as translation, cultural footnoting, editing, and distribution (Lee Citation2016); and build fandoms that, far from being a shadow economy of culture, outstrip the global business of industry in terms of volume, reach, and speed (Lee Citation2011): ‘The twenty-first-century audience is no indistinguishable mass of languid couch potatoes, but a bubbling source of creation and production that challenges the power dynamics of the old producer/consumer binary’ (Kehrberg Citation2015, 86).

Banks and Deuze (Citation2009) described consumers’ participation in creating and distributing media content and experiences as ‘co-creative labour’, fans being actively and proactively committed to their fan activities, especially on digital media. It is also becoming more difficult to divide them into consumer/provider or subject/object. Fan activities on digital platforms are seamless and cannot be defined by traditional time divisions, such as playtime or working time, and Twitter fandom tai-numa activities were indeed ‘full-time fandom’ (Oobi Citation2021).

Within this context, the present study focuses on the possibilities and dynamism of the Thai BL fandom, other than as a content recipient, and examines how tai-numa, particularly on Twitter, have developed. Through interviews and participant’s observation, it explores fans’ practices, experiences, and intersections and how they understand and negotiate the various conflicts and tensions within fandom activities. Further, it approaches struggles and negotiations between fans and the Japanese media in the context of the global distribution business of the cultural industry to present possibilities and further challenges of digital fandom.

Research methods

I approached this study from an ‘acafan’ perspective. An acafan is a person who identifies as both a fan and a researcher, treating subcultural knowledge as part of their work as a scholar, and who, as an insider within the fandom, can facilitate relationships with other fans (Lee Citation2021). Being a fan involves emotions while being a scholar involves the power to interview and analyse (Hellekson Citation2011). Consequently, I have participated in and observed the dynamism and sensitivity of the online fandom of tai-numa for over three years, from its early expansion period to April 2023. Specifically, while following Thai BL dramas in real time, I engaged in proactive fan activities on Twitter and other platforms. This research clarifies how fans cross-cultural borders in their transnational consumption and cultural reception and analyses its implications.

A qualitative analysis was conducted through interviews with fans. As they are not simple recipients and consumers of media and content, but creative people who produce meaning, interpret cultural texts and create communities (Jenkins Citation2006), I examined the types and meanings of fan activities, considering their social context. Semi-structured interviews were conducted, with questions prepared in advance, added, and modified during the interview process for in-depth exploration. In total, 19 participants who self-identified as being fans of tai-numa continuously since the first half of 2020 were recruited through Twitter. The participants were provided with an overview of the study and questions and a consent form before the interview. Permission was obtained after informing them that the interview would be conducted in a closed setting via a ZOOM voice call and would be recorded, the recordings would be deleted once the data analysis was complete, and they could stop the interview at any time or request that some or all their data be removed from the study.

As Dym and Fiesler (Citation2020) demonstrated, most fans are not open about their identity; thus, the subjects of this study were never asked to share personal details (e.g. name, age, region of residence, gender, and sexuality) unless and only to the extent that they mentioned them in describing their experiences. When quoting, pseudonyms unrelated to their social networking IDs or personal characteristics were adopted to protect their anonymity (). Although tai-numa is a cyber-community, it can be understood as a ‘hybrid’ context: fans communicate and engage on Twitter, and the connections and details established online are linked to real-life fan activities (Kamm Citation2013).

Table 1. Interviewees and fandoms they belonged.

In the data analysis, the keywords, concepts, and experiences representing fans’ thoughts and actions from the transcripts were coded, and the findings of previous research (fan studies, cultural studies, and cultural sociology) were employed to organize and interpret patterns and themes. The author uses interviews as not as a representative sample of tai-numa, but to illustrate the dynamics of fan discourses and practices. Following the analysis, the findings were divided into the following themes: trans-subcultural multi-layered fandom activities, subjectivity and responsibility, conflict and fragmentation, self-cleansing, and the formation and changing mediascape of the tai-numa fandom.

Complexity of trans-subcultural fandom activities

The power that the fans get from the dramas and actors, all sorts of energies are intermingling in tai-numa. I’ve never seen a fandom like this. Some are translating, some are thinking about it, I just feel the power. Everyone is so alive. Where does this power come from?

Morimoto (Citation2021) pointed out the importance of understanding media fandom as a contact zone, describing it as ‘social spaces where cultures meet, clash and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power’ (Pratt Citation1991, 34). The cultural fandoms that people in tai-numa had previously experienced were extremely diverse, including K-pop, anime, manga, musicals, sports, fan fiction, kabuki, voice actors, female idols, novels, foreign dramas, and films. By contrast, there were those who ‘didn’t even know the word “swamp” or “otaku”’ (Wat) or ‘didn’t like anything enough to get into it’ (Shin), and those who were not direct BL consumers, but had a ‘relationship moe [feeling strong affection about relationships] between members’ (Black) in other circles, enjoyed ‘relationship moe between sports players’ (Air), or ‘liked K-pop and the chemistry between members’ (Ae).

In most cases, BL media are initially imported physically and digitally from Japan into other Asian counties in the form of manga (Welker Citation2022b), and Thailand is no exception. Prasannam (Citation2019) noted that BL culture in Thailand gradually emerged in the 1990s, with the influx of Japanese popular culture, and it was intertwined with the Korean Wave, with K-pop boy band members being coupled and shipped since 2007. Today, the Japanese genre of BL has proven not only popular and commercially viable but has also melded into the popular culture landscape in Thailand (Bunyavejchewin Citation2022). The Japanese BL genre is commonly called ‘wai’ in Thai, as a blending of Japanese BL and other genres targeted narrowly at gay men. Wai films and drama series have become major form of local BL media since 2012 (Bunyavejchewin Citation2018). Dredge (Citation2022) describes ‘Korpabese’ as an imagined source of East Asian modernity in the contemporary Thai context, where Thai BL enthusiasts assimilate imagination and references from both Korea and Japan. While Thai BL fans acknowledge the origins of BL is in Japan, they use Korean materials to construct their BL images. BL drama series hybridize Thai understandings of sex and gender with explicit Japanese models of reading same-sex attraction to create a ‘glocalized’ code (Baudinette Citation2019) and Sino-Thai or mixed-ethnicity facial features cast in BL dramas reveals the affinity of contemporary Thai popular culture with the Korean wave (Lizada Citation2022).

The reception of Thai BL outside of Thailand has been also studied as a form of challenge to the understandings of the glocalization of cultural products, privilege hierarchies and binary accounts of cultural flow. For example, Filipino fans create new meanings within Thai BL text and re-territorialize their consumptions to Filipino’s specific social experience to produce knowledge that challenges the heteronormative nature of their everyday lives (Baudinette Citation2020). Chinese audiences, on the other hand, consume Thai BL dramas in a carnivalesque manner with strategic self-censorship and watch them ‘to escape into and imagine the better alternatives given the pressures and difficulties most of them are facing in reality’ (Zhang Citation2021, 142).

Even before encountering Thai BL dramas, many Japanese fans actively found BL interpretations in subcultures that do not officially put out coupling or shipping content, such as K-pop, Japanese idols and bands. The ‘retationship moe’ as several interviewees experienced, can be understood as a part of shipping, or ‘coupling’ (kappuringu) in Japanese: the cultural practice of BL fans’ practice of wishing for people to enter a relationship, including fictional characters and real celebrities (Welker Citation2022b). BL readings have found their way into many subcultures as a pervasive or highly compatible attitude.

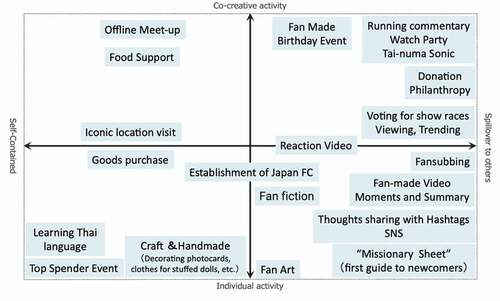

Various fan activities that have emerged in tai-numa have either been brought in by fans from their original subcultural fandom or are shared with other fan cultures (). These include ‘self-contained’ fan activities, such as iconic location tours and language learning, and ‘spill over’ fan activities, such as making missionary sheets (summaries and commentaries on dramas and actors to attract more people to watch the series), fan-subbing, and philanthropic activities. Many fan activities require cooperation in each fandom, and co-creativity and spill over fan activities are prevalent in tai-numa.

These fandom activities can be divided into three main categories in terms of their origin and development: (1) those unique to Thailand (e.g. birthday adverts on local tuk-tuks [transport vehicles]), top spender events, and money note bouquets; (2) those that have spilt over from the K-pop fandom (e.g. decorated photocards of actors/idols, fan-made birthday events, and adverts); and (3) those specifically active in tai-numa (missionary sheets and fan fiction/art).

In tai-numa in particular, missionary sheets existed by drama, actor, actor couples, and agency, or all actors of the same agency. The development of diverse sheets (e.g. by actor’s birthday and age or university) led to the creation of sub-fandoms, which expanded their fanbase by proselytizing the ‘sub-numa’ of interest.

Even in seemingly self-contained activities – uploading derivative works to the web, giving feedback, writing and sharing fiction based on the original, or deepening their understanding by learning Thai – fans were seeking deeper involvement, such as ‘interaction’ with their target, cultural content, love spill over, and a deeper understanding of the target. Behind this participatory culture, as Jenkins (Citation2006, Citation2021) put it, there seems to be a sense of responsibility for and commitment to the fandom as a place where ‘newcomers’ (people) are not seen as ‘new’ because many fans join at the same time.

Sense of ownership and responsibility in the fandom

Similar to other successful fandoms (e.g. Stan Twitter), tai-numa is a community of practice in which members communicate, help each other gather information, and learn from their interactions (Malik and Haidar Citation2020). Fans with translation capabilities, design and information gathering skills, missionary sheets development skills, and fan art and fanfiction writers represent the ‘power’ that attracts followers. Referring to Stan Twitter, Malik and Haidar (Citation2020) pointed out that once an account has ‘power’, it becomes almost impossible to overthrow. The older the history of a fandom, the more obvious the discrepancy between ‘new’ and ‘old’ fans, as a structure is formed in which newcomers learn from the information accumulated by fans who have been active for many years. The rapid growth of tai-numa in the first half of 2020 May be attributed to fans’ lacking the awareness of being new, having the feeling that they witnessed the process of fandom hierarchy and that everyone could participate in that ‘power struggle’ if they wished.

There is a sense of ‘we have the same badge’ here. It was comfortable because everyone around us was new, and many people thought they were at the centre of the fandom, as if everyone thought they had created their own culture, so it was easier to speak out.

Fans have a sense of agency as bearers of their own culture and gain followers by disseminating various information and creations, thus gaining an identity as having their own fans within the fandom. The fandom hierarchy is formed over time, and the feeling of being given equal participation in the process is linked to fans’ proactiveness. The asymmetry of cultural exchange and the fact that Thai culture in Japan was still a niche, described as ‘people who like to look for gemstones that nobody else has found’ (Black), also brings a ‘sense of responsibility’ (Pan).

It was a sense of mission. I wanted it [my fandom] to look ‘flourishing’ when people look at it from afar. This is also my first time I have felt so much that ‘I must contribute to it’.

If I don’t draw fan art or write fan fiction, the numbers of fanfics in pixiv [derivative works submission website] won’t increase! I have a sense of responsibility of my own.

The perception of equal opportunities for participating in niche cultural fandoms created a participatory culture of proactive fans with a sense of a mission. In addition to a diverse range of Thai BL dramas, tai-numa fans also enjoy Filipino, Taiwanese, and Korean BL. In this sense, indeed, ‘Thailand plays a medial role in BL dramas regionally, acting as a node where popular culture is indigenized’ (Dredge Citation2022, 194).

Conflicts and fragmentation within the fandom

However, conflicts may arise, usually in the form of shipping or ‘fangirling’, referring to issues of supporting the coupling of real people with same-sex partners. Fans can detect and curate every moment of character ‘intimacy’, and through subtitling, translating, video-making, and gossiping practices, transform them into a ‘hyperreal love’, in which the line between reality and artistic performance is erased through imagination, recreation, instantaneous circulation, and overcompensation (Zhang and Dedman Citation2021, 1041). Consequently, conflicts can arise due to differing opinions and behaviours about creating and interpreting fan narratives regarding what it means to ship real persons. While the norm of enjoying BL content in hiding still exists (Hori Citation2020; Sato and Ishida Citation2022), it has been remarked that many fans who have been in the closet about their love for BL engaging in excessive shipping started producing derivative creative works in the open. Some fans who have created secondary works within their former subculture fandoms pointed out that their pre-tai-numa fandom experiences may have led to significant differences in their understanding of fan fiction shipping real persons. The interviews captured fans’ acknowledgement of objectifying their desires against their idols.

When I see the enthusiasm not only for the dramas but for the actors themselves, who are not in the roles, I feel that we are seeing a gender-reversed version of the sexual exploitation of women in Japan. Of course, I understand that actors are fan servicing for business, but I have some delicate feelings about fans’ behaviour and how much they should be allowed to ask for.

Another example of conflict may arise from fans telling an actor who is working out not to exercise too hard because they want him to stay cute. Those who disagree ask if this is something fans should say to a real person: ‘Isn’t this a kind of body-shaming?’ (Soda). Further, videos containing fans’ fantasies about a couple appeared in the editing of drama videos created by fans: ‘fans think of their biases as free content that can be edited, so they put their own thoughts and interpretations on it and using their celebrity, which is violent’ (Soda). Thus, the feeling of having a mission within the fandom could also involve a negative aspect.

There is great self-awareness of the fact that they are boosting the couple and that their actions are driving the officialdom. I think they inspire each other like they must make the couple they support more exciting, and then they apply it to the persons themselves, which kind of boils down to the worst part of being an ‘otaku’.

Despite the deep-dive invisibility of the creations of some of Japan’s most popular male idols, when it comes to Thai content, creative credits and copyrighted material are loosely handled, and there’s a kind of naivety that ‘Thai people have deep pockets and they’ll forgive you, they’ll laugh it off’.

The sense of initiative and responsibility that enabled participation in democratic fandom can sometimes run out of control and lead to disrespecting behaviour towards actors as real persons; despite actors’ agencies marketing official couples, fans are undeterred. In addition to the less likeliness of emerging rights regulations on the use of actors’ images, the imbalance in cultural exchange between Japan and Thailand might be an explanation. Thai actors are a niche presence in Japan, which connects to the arrogance that one can be involved with a sense of autonomy and responsibility.

Fandom self-cleansing and connection to society

Discussions within fandoms spring up frequently, and while criticism sometimes creates divisions, it has also helped some fans gain new knowledge and values, generating a self-cleansing process. Those who had been in different fandoms were surprised to find that in tai-numa, ‘criticism is possible’ (Sandee) and it ‘can be said’ (Pete).

A fandom where there was always someone who could say, for example, that a single word could be a discriminatory statement or could question unconscious acts of gender bias.

This manifests in conflicts within the fandom and as a countermovement to BL representations, especially those involving the Japanese mass media: ‘when there are obviously strange descriptions of LGBTQ+ on random websites’ (Sandee). The countermovement can be encouraged when fans ‘learn from and are inspired by the people they follow on social networks’ (Porsche), when ‘LGBTQ+ people or people who are interested in the subject point it out’ (Sandee), or when the Thai production team ‘mentions the sexual minority rights movement or shares articles’ (Miw).

When the Japanese mass media reported that many BL dramas are produced because Thailand is ‘tolerant’ of LGBTQ+ people, criticisms were made, and debates arose on if and why these representations are discriminative. Thailand is actually a conservative kingdom where masculine-feminine binarism is considered the only legitimate form. Most Thai people believe that non-normative sexual behaviours should be expressed only in private (Bunyavejchewin Citation2022).

The fact that BL is not just entertainment but also makes me aware of things I was not aware of, and is connected to an interest in social issues, means that I, as a BL fan, can give back to society rather than just being a fan…

When I met Thai BL and used Twitter, I realised that I had internalised prejudices; now, I can stop drawing a line between BL and real-life homosexuality.

Reading as a fan can often be a queer practice (Jenkins Citation2011), and BL/Yaoi reading has the potential to change elite homo-sexual, homo-social, and misogynistic literature into more inclusive and egalitarian narratives/fantasies. By focusing on pairings and relationships, fans can broaden and deepen their understanding of gender construction inside and outside the text (Aoyama Citation2013, 77). By watching Thai BL dramas, tai-numa fans have the potential to go beyond the consumption of cultural content and directly connect with the real world, transforming their understanding and actions towards queerness.

I didn’t know about same-sex marriage and the historical oppression of LGBTQ+ people until now; thanks to tai-numa, I thought I should learn more about it… […] After seeing the points made in the fandom, I became aware […] and started reading books and paying attention to [media] expressions [used to introduce BL]. I realised that what I said could make the parties involved or someone else feel bad.

I felt sorry for consuming BL dramas about people suffering from homosexuality-related issues, but when I came to tai-numa and saw the actors supporting same-sex marriage, I came to think it is important to find positive aspects in myself and face the real world.

While confronting their own identity (even if they were heterosexual), fans relativized themselves and self-reflected on the meaning of being observant about homosexuality. They deepened their understanding, supported BL drama actors who talked about gender fluidity, responded to tweets about marriage equality, spoke out for LGBTQ+ rights, participated in the first Pride Parade post-COVID-19 in Japan, and criticized discriminatory representations by an intolerant society and media. Their respective commitments to the real world were diverse, but BL dramas induced their actions.

Negotiating with media and counteraction

I think ‘geo-blocking’ took away the diversity of fandoms, a great mix of factors, like fans’ position in society. The chaos is gone, and you end up with a homogenous group with similar social positions, hierarchies, and experiences.

Establishing tai-numa

Tai-numa was established because of a multi-layered interplay of external and internal factors, including the mediascape and socio-cultural conditions surrounding BL and its fans in Japan. First, Thai BL dramas were distributed on a seamless global platform (Lizada Citation2022) and has been transformed into a transmedia property, part of Japan’s so-called ‘media mix’ (Welker Citation2022a, 274). Although the East Asian region participated at different and unequal levels in the production and consumption of circulating pop culture (Huat Citation2004, 204), global platforms, such as YouTube, played an innovative role in terms of pop culture export and distribution. According to fans, the advantages of YouTube were free and simultaneous viewing, official English subtitles at the time of broadcasting, and the possibility of fans to create Japanese subtitles and request the official channel to approve them, the latter being a major attraction, as many Japanese fans had difficulties following English subtitles. The platform, which can be viewed on individual gadgets (e.g. smartphones), was also compatible with the individualization of cultural content consumption. As cultural consumption has become transnational and cultural tastes have diversified, cultural content has shifted from being enjoyed with family members to being enjoyed by individuals. In addition, BL has been subjected to a strategy of ‘self-restraint’ (Hori Citation2020, 218), whereby women must hide their tastes outside their circle of friends, with BL being something to be enjoyed alone, in secret (the gender asymmetry preserved in the Japanese society is also a factor). Thus, individualized platforms have become spaces for women and queer identities to mindlessly enjoy, participate in, and create BL-related content.

Second, the provision of visual content on these global platforms and their linkage with social networking sites was compatible with fans’ behaviour of intensively consuming what they like to promote. Fans can attract and recruit new fans through their networks and the distribution of secondary works (Wood Citation2013). All participants in this study began watching Thai BL through buzzed tweets and missionary sheets by fans, recommendation functions on social networking sites, or friend suggestions. The social aspect of fandom was also evident, and the spillover of fan activities had a linear and immediate effect on attracting new fans.

A parallel and important context was the global pandemic: in Japan, the first state of emergency under the COVID-19 pandemic was declared in March 2020; commuting was drastically reduced nationwide, and people were advised to stay home. As a result of a substantially diminished direct contact with people, both students and workers had more time available for themselves, and coupled with the situations mentioned above, ‘there was nothing to stop the desire’ (Kao). In addition to drama viewing, there was an abundance of different visual content (e.g. lives on Instagram, event streaming) provided by BL actors on SNSs, ranging from official to unofficial fan-made content, and it was possible to ‘explore endlessly because the supply was so large and there were works I haven’t seen’ (May). However, with the Japanese media acquiring distribution rights and the geo-blocking of YouTube, the early expansion of tai-numa changed significantly, affecting the fans’ viewing landscapes.

Consequence of geo-blocking and fandom’s response

From the second half of 2020, many Thai BL dramas, including those that had already been broadcasted, were acquired by Japanese distributors, and disseminated through various satellite channels and video distribution sites, such as Rakuten TV, U-NEXT, TELASA and Amazon Prime. Access from Japan to global platforms was geo-blocked, so watching these dramas simultaneously around the world for free became impossible without a virtual private network (VPN).

I think the intervention of geo-blocking and Japanese media has created a ‘gap’ among us. One of the things that made Thai dramas more interesting was the ability to get excited with people from all over the world in real-time through social networking. It’s a shame that this has been taken away from us.

The geo-blocking-caused ‘gap’ represented the high barrier to viewing due to the need for information gathering skills to understand where and how dramas were available on the various platforms, literacy and financial resources regarding VPN and its subscription, language skills to understand the official English subtitles, and the high cost and complicated contract for viewing satellite broadcasts. Consequently, individuals were divided into those who could watch and those who could not, depending on their skills and financial capital. While Japanese distribution services tried to attract customers with advertising claims such as ‘exclusive broadcasts’ and ‘fastest in Japan’, distribution was delayed by a week or more from that in Thailand and other countries, reinforcing fans’ disappointment.

It’s created a divide between those who can watch the show in real-time and those who can’t. There’s a kind of self-restraint that’s created, like, ‘not everyone has a VPN, so you don’t want to spoil too much’.

Fans are the kind of people who like to encourage everyone to like what they like. But because it’s geo-blocked, we don’t know what we can recommend.

Simultaneity and missionary potential were two things that gave tai-numa its early momentum. From the geo-blocking and delayed distribution, fans’ free expression of feelings, impressions, and thoughts after watching dramas in real-time became less likely to be actively discussed in a ‘no spoilers’ atmosphere. Furthermore, interaction with overseas fans became difficult, and opportunities for democratic dialogue were reduced.

Conclusion

Tai-numa was an online fandom created by Japanese speakers and a transnational and trans-subcultural contact zone: a place to create, learn, reflect, negotiate, and update values. The initial stage of fandom was supported by the equal, non-hierarchical, heterogeneous mix of fans from different subcultural backgrounds, allowing for simultaneity in fandom activities. Furthermore, the mediascape of Thai BL drama, the characteristics of BL content and fans, and the external factors of the pandemic created the ‘sense of ‘togetherness’ (Porsche) in tai-numa.

Border-crossing does not only occur between different nations and their assumed cultures. ‘BL is a transnational and transcultural media phenomenon’ (Welker Citation2022b, 3) and BL dramas from Thailand were found to be not only transnationally and transculturally, but also trans-subculturally accepted. They resonated with the values and culture of Japanese society and other subcultures, providing diverse meanings, experiences, reflections, and value transformations for their fans. The mediascape changes of Thai BL dramas over the past three years also revealed a contradiction between local (Japanese) based cultural business and transnational consumer desires, creating dissatisfaction and fragmentation within the fandom.

‘From the beginning, it has been the fans that kept the BL genre alive. In the twenty-first century, their technological skills and acumen often far exceed that of government and industry entities that seek to regulate their participatory culture’ (Wood Citation2013, 60). Echoing back to Welker’s analysis of BL ‘as a device for rethinking LGBT(Q) issues’ (Welker Citation2022b, 9), ‘BL is political’ (Welker Citation2022b, 4). Hence, the paper suggested potential approaches that fandoms could incorporate into their fan activities (e.g. raising awareness, debating, and giving back to the community) and what is needed for such fandoms to be established and sustained (e.g. member equality, openness, and involvement).

As a limitation of this research, the author is aware of the difficulty of presenting a full picture of fandoms when they are changing and becoming more diverse and fluid. Even between the time this paper was first written and its publication, engagement with the existing media and the size of the fandom surrounding Thai BL dramas have changed, and the nature of fandom has become more diverse. In this sense, this paper documents the situation and fans’ voices in the early years of the Thai BL drama boom. Further research is necessary on more diverse people, including those who became tai-numa fans after Japanese mass-media mediation and how fandom dynamism is different. In the context of the global pandemic, physical interaction has been almost impossible, increasing the number and size of online fandom activities. This study contributes to existing fandom research on online fandoms, the expected conflict, and the development and sustainability of transnational fan contact zones. As an acafan, ‘giving back’ this knowledge to fandoms can be a way of giving back to the community (Dym and Fiesler Citation2020) to help academic and fan communities understand each other (Lee Citation2021). This research also demonstrates how online fandom activities could be transposed into real-life action and provides fandoms with a perspective to identify future possibilities for the development of fandoms and how to reach real society and seek positive change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aoyama, T. 2013. “BL (Boys’ Love) Literacy: Subversion, Resuscitation, and Transformation of the (Father’s) Text.” US Japan Women’s Journal 43 (1): 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1353/jwj.2013.0001.

- Banks, J., and M. Deuze. 2009. “Co-Creative Labour.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 12 (5): 419–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877909337862.

- Baudinette, T. 2019. “Lovesick, the Series: Adapting Japanese ‘Boys Love’ to Thailand and the Creation of a New Genre of Queer Media.” South East Asia Research 27 (2): 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/0967828X.2019.1627762.

- Baudinette, T. 2020. “Creative Misreadings Of“thai BL” by a Filipino Fan Community: Dislocating Knowledge Production in Transnational Queer Fandoms Through Aspirational Consumption.” Mechademia: Second Arc 13 (1): 101–118. https://doi.org/10.5749/mech.13.1.0101.

- BBC NEWS. 2021. “Squid Game: The Rise of Korean Drama Addiction.” Accessed April 11, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-58896247.

- Bunyavejchewin, P. 2018. “The Wai (Y [Aoi]) Genre: Local BL Media in Thailand.“ In Mechadamia Conference on Asian Popular Cultures, May 27, 2018, Kyoto, Japan, 1–32.

- Bunyavejchewin, P. 2022. “The Queer if Limited Effects of Boys Love Manga Fandom in Thailand.” In Queer Transfigurations: Boys Love Media in Asia, edited by J. Welker, 181–193. University of Hawaii Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1xcxqw2.19.

- Dredge, Kang-Nguyễn Byung’chu. 2022. “Faen of Gay Faen:.” In Queer Transfigurations: Boys Love Media in Asia, edited by J. Welker, 194–208. University of Hawaii Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1xcxqw2.20.

- Dym, B., and C. Fiesler. 2020. “Ethical and Privacy Considerations for Research Using Online Fandom Data.” Transformative Works & Cultures 33. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2020.1733.

- Green, J., and H. Jenkins. 2011. “Spreadable Media: How Audience Create Value and Meaning in a Networked Economy.” In The Handbook of Media Audiences, edited by V. Nightingale, 109–127. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444340525.ch5.

- Hellekson, K. 2011. “Affect and Interpretation.” Acafandom and Beyond: Week Two, Part One. Accessed June 20, 2011. http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2011/06/acafandom_and_beyond_week_two.html-s.

- Hori, A. 2020. “Shakai mondai ka suru”. [“BL Becoming a Social Problem”].” In BL No Kyokasho. [Textbook of BL], edited by A. Hori and Y. Mori, 206–220. Tokyo: Yuhikaku.

- Huat, C. B. 2004. “Conceptualizing an East Asian Popular Culture.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 5 (2): 200–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464937042000236711.

- Jenkins, H. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University.

- Jenkins, H. 2011. The Origins of “Acafan”. (20 June 2011) Retrieved 26 April 2022. http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2011/06/acafandom_and_beyond_week_two.html.

- Jenkins, H. 2021. Convergence Culture: Fan to Media Ga Tsukuru Sankagatabunka [Participatory Culture Created by Fans and Media]. Tokyo: Shobun-sha.

- Jirattikorn, A. 2021. “Between Ironic Pleasure and Exotic Nostalgia: Audience Reception of Thai Television Dramas Among Youth in China.” Asian Journal of Communication 31 (2): 124–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2021.1892786.

- Kamm, B. O. 2013. “Ethics of Internet-based Research on Japanese Subcultures.“ Social innovation and sustainability for the future : recreating the intimate and public spheres: The 5th Next-Generation Global Workshop, edited by W Asato and Y Sakai, November 6–7, 2012, Kyoto, Japan, 525–540. Kyoto: Kyoto University.

- Kehrberg, A. K. 2015. “‘I Love You, Please Notice Me’: The Hierarchical Rhetoric of Twitter Fandom.” Celebrity Studies 6 (1): 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2015.995472.

- Lee, H.-K. 2011. “Participatory Media Fandom: A Case Study of Anime Fansubbing.” Media, Culture and Society 33 (8): 1131–1147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443711418271.

- Lee, H. K. 2016. “Transnational Cultural Fandom.” In The Ashgate Research Companion to Fan Cultures, edited by L. Duits, K. Zwaan, and S. Reijinders, 195–207. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315612959-15.

- Lee, K. 2021. “Acafan Methodologies and Giving Back to the Fan Community.” Transformative Works & Cultures 36. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2021.2025.

- Lizada, M. A. 2022. “A New Kind of 2Getherness: Screening Thai Soft Power in Thai Boys Love (BL) Lakhon.” In Streaming and Screen Culture in Asia-Pacific, 125–143. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-09374-6_7.

- Malik, Z., and S. Haidar. 2020. “Online Community Development Through Social Interaction—K-Pop Stan Twitter as a Community of Practice.” Interactive Learning Environments 31 (2): 733–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1805773.

- Morimoto, L. 2021. “Transcultural Fan Studies as Methodology.“ In A Fan Studies Primer: Method, Research, Ethics, edited byP. Booth, and Williams,51–64. University of Iowa Press.

- Oobi, Y. 2021. “Chapter 9. “Digital Fandom No Shatei [The Projection of Digital Fandom Research].” In Post-Media Theories, edited by M. Ito, 208–232. Kyoto: Minervashobo.

- Prasannam, N. 2019. “The Yaoi Phenomenon in Thailand and Fan/Industry interaction.” Plaridel 16 (2): 63–89. https://doi.org/10.52518/2020.16.2-03prsnam.

- Pratt, M. L. 1991. “Arts of the Contact Zone.“ Profession (91): 33–40.

- Ross, K., and V. Nightingale. 2007. Media and Audiences: New Perspectives. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press.

- Sato, M., and H. Ishida. 2022 Survey of BL Readers/Nonreaders Report. https://researchmap.jp/multidatabases/multidatabase_contents/index/671481/limit:50?frame_id=1260138.

- Welker, J. 2022a. “Afterword: Boys Love as a World-Shaping Genre.” In Queer Transfigurations: Boys Love Media in Asia, edited by J. Welker, 272–276. University of Hawaii Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780824892234-023.

- Welker, J. 2022b. “Introduction: Boys Love (BL) Media and Its Asian Transfigurations.” In Queer Transfigurations: Boys Love Media in Asia, edited by J. Welker, XIII–15. University of Hawaii Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780824892234.

- Wood, A. 2013. “Boys’ Love Anime and Queer Desires in Convergence Culture: Transnational Fandom, Censorship and Resistance.” Journal of Graphic Novels & Comics 4 (1): 44–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2013.784201.

- Zhang, J. 2021. “The Reception of Thai Boys Love Series in China: Consumption, Imagination, and Friction.“ https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/honors_theses/jm214z157.

- Zhang, C. Y., and A. K. Dedman. 2021. “Hyperreal Homoerotic Love in a Monarchized Military Conjuncture: A Situated View of the Thai Boys Love Industry.” Feminist Media Studies 21 (6): 1039–1043. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2021.1959370.