ABSTRACT

As well as finding empirical relationships between victimisation, key socio-demographic variables and various psychological and environmental processes, criminologists have long suspected that the feelings now identified, corralled together and labelled as ‘the fear of crime’ have roots in the wider shifts in the social and economic bases of society. In this paper, and using survey data from a nationally representative sample of Britons aged over 16 (n = 5781), we explore the relationships between feelings of political and social nostalgia and the fear of crime. We find that nostalgia is strongly related to crime fears, and, indeed, stronger even than variables such as victimisation, gender and age (three of the frequently cited associates of fear). We go on to explore these relationships further in terms of different socio-economic classes and relate feelings of nostalgia and fear to their recent (ie, post-1945) historical trajectories.

Introducing the fear of crime

Since it was first researched (during the 1970s in the United States of America and the 1980s in the United Kingdom and subsequently in many other countries) the fear of crime has been one of the perennial topics in criminology. Numerous theories have been put forward to explain it, and various processes and factors have been found to be related to it (see Farrall, Jackson, & Gray, Citation2009; Hale, Citation1996 for reviews). Almost all of the main socio-demographic variables one would wish to list (such as age, gender, ethnicity, physical strength, income, location of residence or tenure) have been found to be related to the fear of crime. Various other variables have also been proposed, or been found, to be associated with the fear of crime, such as victimisation, perceptions of the police and the effectiveness of the criminal justice system, awareness of local crime rates and feelings of control over the local environment. Psychological processes have also been found to be related to the fear of crime. In addition to this, some researchers have even suggested that there may be more than one ‘form’ of fear of crime, with Jackson and colleagues (Farrall et al., Citation2009; Jackson, Citation2004) proposing a distinction between experiential forms of fear (direct moments when fear manifests itself in the face of some threat) and expressive forms (which are less ‘concrete’ and encapsulate less coherent fears).

Against this background, it might appear as unproductive (or at least unwise) to propose a new variable as a key factor in exploring the fear of crime, but that is what we intend in this contribution. Our aim is to assess the extent to which it is possible to understand the fear of crime as a consequence of feelings of nostalgia (those feelings of longing for a way of life now past and unrecoverable). Since nostalgia, as we shall come to see, is very specific to time and place, our work is located consciously in the historical experience of the United Kingdom; the world’s first industrial nation, and hence amongst the first of those to experience the processes associated with deindustrialisation. However, the United Kingdom is certainly not the only country to have undergone such processes, and there is therefore the possibility that our findings in the United Kingdom may be applicable to varying degrees in other countries in both Europe and North America and, perhaps, to other societies as they experience economic and social change.

What is nostalgia? Why might it be related to the fear of crime?

Bonnett (Citation2010) has argued that ‘nostalgia’ has been a ubiquitous but often unacknowledged aspect of the public’s political imagination over the last century. Political nostalgia typically creates a bleak historical record of the present; it is a dissatisfaction with one’s current status, in tandem with a fear of the future that evokes a call to return to an earlier, safer and better time (Gaston & Hilhorst, Citation2018). In simple terms, nostalgia renders the ‘doctrine of progress’ redundant. Gaston and Hilhorst (Citation2018) note how nostalgia in Western Europe and the United States was revitalised during the Reagan-Thatcher period, when both leaders promoted socially conservative agendas and spoke of lost ‘family values’. Indeed, scholars have described how nostalgic narratives facilitate a backwards gaze with a promise to reawaken ‘the good old days’—a practice that has been used by politicians on both the left and right (Bonnett, Citation2010; Gest, Reny, & Mayer, Citation2018). More recently, we have witnessed a rise in nationalist populism in Europe which has utilised nostalgic sentiments as a motivating force (Flemmen & Savage, Citation2017; Gest et al., Citation2018). For example, the upswing in support for the UK Independence Party (UKIP) in BritainFootnote1 as well as the ‘Brexit’ referendum in 2016 provides a compelling example of the power of political nostalgia. The campaigns that accompanied these developments spoke of past losses and scepticism about promised futures. They emphasised a loss of tradition and a mythical integrity that was set against a perceived distant and mainland European elite (Gest, Citation2018). In examining these developments, Gest et al. (Citation2018) have introduced the concept of ‘nostalgic deprivation’ which refers to the discrepancy between individuals’ understandings of their current status and their perceptions about their past. This deprivation may be expressed in economic terms (inequality), political (disempowerment) or social status. Their contribution has demonstrated that nostalgic deprivation among white respondents in their study drove support for the ‘Radical Right’ in both the United Kingdom and the United States in the 2010s.

Similarly, anthropologists and sociologists have explored the ways in which ‘accelerated change’ (Eriksen, Citation2016) has altered individuals’ sense of who they are and triggered feelings of longing—often for memories that have ‘reconstructed’ the stability and vigour of previous eras (Lash & Urry, Citation1994, pp. 246–248). The features of the groups in society who may feel nostalgic include those for whom change is identifiable, but who did not initiate the changes, nor feel that they were consulted about those changes (Eriksen & Schober, Citation2016, p. 3). These groups or segments of society have often experienced downward social mobility (Thorleifsson, Citation2016, p. 108), which now feels inescapable. These feelings of nostalgia speak to a set of debates about how social identity and social reproduction are related to one another during periods of rapid economic and social change. Indeed, many have identified recent manifestations of nostalgia with neo-liberal restructuring (Eriksen & Schober, Citation2016, p. 3). Wright notes how during periods of rapid social change, the disruption in values which is associated with these changes and the sense of social hierarchies as being in flux are associated with feelings of nostalgic (and sometimes possibly fictionalised) accounts of ‘the past’ (Citation1985). Thorleifsson (Citation2016, p. 109), for example, notes that for one of her respondents, ‘nostalgia seemed to be the outcome of accelerated change caused by migration and the neoliberal restructuring of the economy’. The self-seeking individualism of the present (on which see also Dardot & Laval, Citation2013) is frequently contrasted with the camaraderie of the past helping to forge a narrative around ‘togetherness’ and ‘traditional values’ (Thorleifsson, Citation2016, p. 108). However, as Thorleifsson’s respondents demonstrate, nostalgic feelings are rooted in specific times and specific places (along with people, practices and values).

Nostalgia, then, appears to be provoked by dramatic change which is foisted upon a section of society, often against their will, and against their interests, and finds expression in particular places, practices and processes which are now perceived to have been expunged once and for all. Such sentiments have been found to lie behind the growth of far-right groups amongst some sections of the white, English working class, who have found ‘that their established place in the world has been withdrawn’ (Winlow, Hall, Treadwell, & Briggs, Citation2015, p. 106). As Pearson (Citation1983) notes, ‘golden ages’ of peacefulness and good orderliness have been woven into discourses about crime, policing and control. Weinburger’s study of retired police officers (Citation1995), for example, also finds a fondness and deep desire for foot patrols (since replaced by patrol by car and then no patrolling at all).

We are not, however, the first to try to locate the fear of crime (or the United Kingdom’s experience of it) to changing national trajectories. Over twenty years ago, Taylor and Jamieson (Citation1998) put forward a set of ideas which sought to locate the fear of crime in the light of the United Kingdom’s historical development. What sets our work apart from theirs is our reliance on empirical data to assess the role played by feelings of nostalgia in explaining the fear of crime and our use of a more explicitly nostalgic framework than that developed by Taylor and Jamieson.

Taylor and Jamieson, taking inspiration from Barbara Ehrenreich’s book Fear of Falling (Citation1989), have suggested that the middle classes have been particularly vulnerable to strategies that emphasise individual risk. Fear of crime, they maintain, is not simply about perceived calculated risks for these people, but about broader insecurities. This group of people are ‘afraid of falling’ from their prominent and secure social and economic position which, due to globalisation and political change, has come increasingly under threat. They go on to argue that the fear of crime is a result of the United Kingdom’s decline from being ‘the workshop of the world’ and empire nation to a member of a global elite (the G20, NATO and until recently the EU), but not the elite nation it once was. Their aim was to understand the relationships between unemployment, anxiety and crime which were embedded in the ‘specific economic, political and social history’ of the United Kingdom (Citation1998, p. 151). The declines which the United Kingdom experienced came from a position of international predominance (especially prior to the 1940s) and domestic prosperity (especially after 1945). Domestically, the number of people working in higher professional occupations rose by 70% between 1951 and 1971 to encompass 20% of male employees (Gunn & Bell, Citation2002, p. 190). The creation of the welfare state, expansion of universities, and relatively prosperous economy of the 1950s and 1960s improved living and working conditions for many in the middle and working classes. Taylor and Jamieson (Citation1998) note, however, that the United Kingdom’s growth rate in the 20 years since the mid-1970s ran at about 2% per annum, having dropped from around 3% from the immediate post-war years (p. 152). Between 1973 and 1980, the United Kingdom’s economic growth rate fell to .6% (Gunn & Bell, Citation2002, p. 199). In 1976 the United Kingdom suffered the ignominy of needing to call in the International Monetary Fund (who loaned the country $3.9bn, or $17.2bn in 2018 figures). Taylor and Jamieson go on to note how the United Kingdom’s manufacturing sectors went into deficit for the first time since the start of the industrial revolution in the early to mid-1980s. There was a miners’ strike in 1974 and a three-day working week between 1 January and 7 March of that year. Alongside this, divorce rates started to rise (legislation in 1969 and 1973 had made divorce easier), and Taylor and Jamieson argue that it rose from around 6000 cases in 1938 to over 160,000 in 1993, putting the United Kingdom at the top of the divorce league table. Single-parent families were a consequence of this. Alongside this, crime rose throughout the 1950s (and continued to do so until the early 1990s). During this period, the British Empire also started to wither. Starting in the very late 1400s, and growing throughout the 1500s, the British Empire expanded to include parts of the Americas, the Caribbean, Australasia, the Indian subcontinent, Eastern and Southern Africa, the Pacific and Indo-China, amongst other places. Its territorial peak is considered to have been in 1921, but the major decline took place in the years after the end of the Second World War. During this same period, the Labour-led government created the welfare state (including the National Health Service), and started to invest in social security systems, state-owned housing and the public ownership of several industries (notably coal mining and car manufacturing) and elements of the country’s infrastructure (such as the transport system). Despite this (some would later argue because of these developments) however, the decline of the United Kingdom’s economic position continued.

Although the 1960s was a period of relative prosperity, especially for the middle and working class, there were still profound social and cultural changes afoot. The loosening of social conventions associated with the rise of ‘youth’ as a social phenomenon and the perceived breakdown of sexual mores and morality emerged as the 1960s progressed and provoked a series of right-wing, socially conservative responses in the form of the National Listeners and Viewers Association (led by Mary Whitehouse, who became involved in the Clean Up TV Campaign, which started in 1964). Alongside this were groups such as the Freedom Association (led by the MacWhirter twins, more famous for their work on the Guinness Book of Records), which also campaigned against the United Kingdom’s membership of the EU, (or EEC as it then was), as well as the Middle Class Alliance and the People’s League for the Defence of Freedom, which campaigned against post-war economic and social reforms (Green, Citation1999, p. 26).

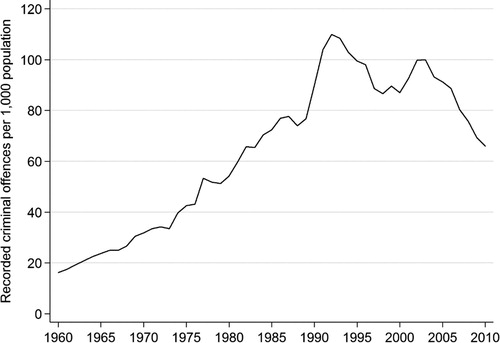

Irrespective of whether or not crime rates had anything to do with the content of television programmes, it remains the case that crime rose throughout the 1960s and 1970s (as shown by below). The rises became steeper again for periods in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, before starting to decline from the early to mid-1990s. Alongside the rise in crime were declines in job security during the 1980s and early 1990s. Working-class jobs (and hence communities) were badly affected by the rampant deindustrialisation of the 1980s (Farrall, Gray, & Jones, Citation2020), whilst middle-class jobs became insecure (although still available in a way that ‘blue collar’ jobs were not) during the 1990s (Gunn & Bell, Citation2002, pp. 188–189). Tenured university positions—a bastion of the middle class—were ended by the 1988 Education Reform Act.

Considering the position of the middle classes, Garland (Citation2001) notes they have historically been insulated from both crime and insecurity, tending to occupy low-crime areas of cities. However, the economic changes wrought by the global downturn of the early 1970s destroyed middle-class feelings of security. Social and spatial changes that gave rise to higher crime rates during the 1960s and the subsequent decades also transformed the middle-class experience of crime—or at least their perception of their experience of crime—for they remained relatively shielded from crime when compared to the working class (Farrall, Gray, Jennings, & Hay, Citation2016). From being something that normally affected the poor, crime, particularly burglary, increasingly became a daily consideration for the middle class. As Garland put it:

The group that had been the prime beneficiaries of the post-war consumer boom now found themselves to be more vulnerable than before in the face of the massively increased levels of property crime that this boom brought in its wake. And the tell-tale signs of crime and disorder became more visible in the streets—in the form of vandalism and graffiti, the incivility of unsupervised teenagers, or the erratic behaviour of the newly deinstitutionalised mentally ill—fear of crime became an established part of daily existence. (Citation2001, p. 359)

As well as losing the security which came with the concept of ‘jobs for life’, the middle class started to lose other aspects of the post-war settlement from which they and their children benefitted; contributions towards the costs of higher education for middle-class children were whittled down and then converted into loans; elderly care (once free within the NHS) now requires reliance upon private nursing homes (which will eat into any inheritance); final salary pension schemes which would once have guaranteed a comfortable retirement are now no longer automatically available for many people, who, encouraged into the marketplace, find it full of hazards and ambiguities (Farrall & Karstedt, Citation2020). At the same time, working hours rose, with 80% of men reporting that they worked in excess of 50 hours a week in 1989 (Gunn & Bell, Citation2002, pp. 203–204). More directly related to matters of routine policing, Walklate (Citation2002, pp. 306–312) notes, upper middle-class residents in England found that their ability to influence local matters (such as day-to-day policing) was swept away by a tide of ‘financial management’ and ‘resource allocation’ which left their local police service unable to continue to pay for a local police station. This situation, and the local police service’s own inability to act differently, left this traditionally powerful and socially engaged section of society with neither a local police officer nor a means of changing this situation. Their resulting anxieties about what the loss of the local police officer meant for crime in their community and their own safety stemmed in part from their dramatic loss of political input into decisions over policing. Where they had once had a voice, they now had no input into decision-making.

The above body of work approaches crime and the fear of crime as a subject through which the middle classes express an array of inter-connected anxieties about their current life experiences. While the threat of a burglary might be a threat in and of itself, it also signifies what might be called ‘the urban other’ and the threat of social disorder which burglars represent. In short, whilst the middle classes remain objectively less exposed to crime than others in poorer regions or parts of our cities (Farrall et al., Citation2016), the threat of crime and disorder symbolises more than an episode of victimisation, but a whole host of meanings about their social, economic and physic position in society. Bauman (Citation2006, p. 130) observes that:

It is the people who live in greatest comfort on record, more cosseted and pampered than any other people in history, who feel more threatened, insecure and frightened, more inclined to panic, more passionate about everything related to security and safety than people in most societies past and present.

Things were, as one might imagine, even worse for the working class during this period of change. As the 1960s came to an end, so levels of industrial strife increased, with strikes in many sectors of the economy and reductions in the worth of salaries. The headlong assault on the working class and their economic livelihoods witnessed during the 1980s left many who had started their working lives looking forward to a career and respectability for both themselves and their children for the duration of their working lives experiencing strikes, under-employment, redundancy and chronic unemployment. As heroin moved into the vacuum created by worklessness (Pearson, Citation1987), so cohesive communities that were once well organised and largely ‘self-policing’ started to experience the worst effects of the economic downturn of the 1980s.

In many ways, the murder of James Bulger (a 2-year-old boy killed by two 10-year-old boys in February 1993) was a signal that crime and disorder were out of control and that the United Kingdom’s streets were no longer safe places to be. The boys who killed James Bulger, as the media were keen to point out, regularly truanted from school, may have watched violent films at home, came from broken families and were ‘known to the authorities’. Their families lived in deprived council-owned housing estates; estates which had been built for the aspirant working class, but which, during the social and economic upheavals of the 1980s, had seen the evaporation of employment, social norms and ‘respectability’. The failure which this murder represented therefore was not just a failure of civil society, but was seen as a failure of regulatory authorities (teachers, schools, housing departments, social services, the police and social workers) to control and deal with these children.

Against these trends, both in terms of the United Kingdom’s global position and the internal dynamics of the United Kingdom’s economy, it is hardly surprising that ‘the past’ looked like a rosy place to have been. Indeed, historians have approached Margaret Thatcher’s appeal to the electorate as partly being about the image of the past (in particular the 1930s; Green, Citation1999, pp. 19–20). Gould and Anderson, for example, argue that ‘the values [Thatcher] admired were those of the inter-war years’ (Citation1987, pp. 42–43). Keith Joseph—one of Thatcher’s closet allies—promoted the idea that the country needed to embrace ‘embourgeoisement’, ‘which went so far in Victorian times and even in the 1930s’ (speech to the Centre for Policy Studies in January 1975; quoted in Green, Citation1999, pp. 19–20). The image of the domestic pastFootnote2 which the Thatcher governments promoted during the 1980s and for much of the 1990s was one in which unemployed men ‘got on their bikes and looked for work’, in which business was not held back by red tape and government interference, in which small-business menFootnote3 were able to hire and fire as needs dictated and in which cricket was played by white men on freshly mowed grass in villages in Kent and Surrey. Christian virtues and morality existed, and the country had not been ‘swamped’ by immigrants (as Thatcher once described it). Social workers had not ‘created a fog in which burglars could operate’, to use one of Margaret Thatcher’s most telling metaphors, and punishments for transgressions were swift, physical and effective. During the early 1980s, her government ministers talked of ‘short, sharp shocks’ as a way of dealing with miscreant youth and promoted the idea of ‘the strong arms of the law’ as a deterrent for those considering breaking the law.

More recent studies of specific communities and their feelings about crime and nostalgia can be found in work by Girling et al. (Citation2000). They note (p. 10) how ‘much “fear of crime” discourse is largely about the protection of certain places or territories (homes, streets, communities, nations) against incursion, usually seen as coming initially from elsewhere’. Their study notes how the fear of crime is wrapped up with other, harder to grasp feelings of changes in the moral order of society; ‘young people’ are often highlighted during such discourses, with accusations that they ‘lack respect’. Such discourses, when explored more deeply, are rooted in a sense that there was once a more peaceful, more socially harmonious ‘past’ which has now ceased to exist (p. 92). However, as Girling et al. note (Citation2000, pp. 92–93) such feelings are not found only amongst the elderly. Nevertheless, the 1960s and changes in school discipline regimes were cited by some in their study as the cause of declines in levels of respect. However, such concerns were not confined to young people; the police and the ‘better policing’ which, as a community the people Girling et al. spoke to were subject to in the 1940s and 1950s, was another common trope (Citation2000, p. 123). Police officers were more respected in the past, it was claimed by their interviewees (Citation2000, pp. 130–131); some of the decline in their position was laid not at the doors of the police, but at ‘do-gooders’ and a more liberal, permissive society.

The question we seek to answer herein is the extent to which feelings of nostalgia are associated with fears about crime. In the next section, we outline our methodology, measurement and analytic strategy before presenting our analyses and concluding with a general discussion.

Methodology, conceptualisation, measurement and analytic strategy

Our data comes from an online survey commissioned to assess the contemporary relevance of Thatcherite values and ideology on the 40th anniversary of the 1979 General Election (n = 5781). It gathered responses from a representative sample of citizens aged over 16 living in Britain and was conducted in January and February 2019 by BMG Research. The survey had a non-completion rate of 34%.Footnote4 Basic data on key demographic variables is presented in the Appendix. Many (although not all) survey items were designed by the authors, following two rounds of cognitive interviewing, two survey experiments and a pilot survey during 2018. These were undertaken to refine key aspects of the items used and to facilitate a reflective discussion of potential question wordings.

Conceptualising ‘expressive’ fear of crime

Our approach to conceptualising the fear of crime follows the work of colleagues such as Taylor and Jamieson (Citation1998), Girling et al. (Citation2000) and Farrall et al. (Citation2009) who approach the fear of crime as being about subjects beyond the confines of crime and safety. As Sparks et al. (Citation2001) note, discourses about crime are a pertinent arena in which to assess the impacts of social and political changes on people’s everyday lives. The fear of crime is thus grounded in people’s senses of location and their appraisal and interpretation of their immediate environments:

[C]rime works in everyday life as a cultural theme and token of political exchange; it serves to condense, and make intelligible, a variety of more difficult to grasp troubles and insecurities—something that tends to blur the boundary between worries about crime and other kinds of anxiety and concern. In speaking of crime, people routinely register its entanglement with other aspects of economic, social and moral life; attribute responsibility and blame; demand accountability and justice; and draw lines of affiliation and distance between ‘us’ and various categories of ‘them’. In short, ‘fear of crime’ research is at its most illuminating when it addresses the various sources of in/security that pervade people’s lives (and the relationship between them) and when it makes explicit (rather than suppresses) the connections that the ‘crime-related’ anxieties of citizens have with social conflict and division, social justice and solidarity. (2001, pp. 895–896)

Sparks similarly argues that:

people’s worries and talk about crime are rarely merely a reflection of behavioural change and ‘objective’ risk (although they represent lay attempts to make sense of such changes and risks), but are also ‘bound up in a context of meaning and significance, involving the use of metaphors and narratives about social change. (Citation1992, p. 131)

The approached adopted by Farrall et al. (Citation2009, p. 79) is very similar to thinking expressed by Sparks and his colleagues. They argue that ‘expressive’ fears (as opposed to experiential fears) are a:

set of feelings which are orientated towards the problem of crime for society. These are quite separate emotionally from one’s own experiences, but possibly strongly linked to them on an experiential level. One’s own victimization experiences do not dictate whether or not one will perceive crime as a problem for society (although, as these experiences accumulate, so they increase the chances that crime will be perceived as a serious problem) since even those who have experienced relatively little victimization will have an opinion about the problem of crime for society.

They go on to add that:

expressive fear is less grounded in day-to-day life, less concerned with the specific details of time and place, and more akin to a set of attitudes or opinions which are brought forth when people are asked to discuss their feelings about crime (a process we have referred to as the invocation of attitude). As such, expressive knowledge may consist of beliefs, perceptions, or attitudes that one has concerning the cultural meaning of crime, social relations, and environmental cues. (p. 153)

Such fears, as Farrall et al. (Citation2009) conceptualise them, speak to the ways in which people make sense of social and economic change and the ‘troublesomeness’ of such changes:

This dimension of the fear of crime we call expressive because it … encapsulates a general sense of uneasiness on their part. In many cases, we feel, this sense of uneasiness is not directly related to crime, but is an expression of wider concerns about the state of society today. (p. 232)

The following three respondents' quotes—which come from Farrall et al. (Citation2009) and their studies of the fear of crime in England & Wales and Scotland—speak to the ways in which the fear of crime is associated with not just crime and policing, but with social and economic change, experienced both locally and globally (emphasis added):

I would say I was more, concerned with the cause than the whole structure of … what seems to be, er, causing crime to be on the increase … and to my mind it’s not just parental control, drugs, violence on television, lack of control by, oh, schools being allowed to control, having discipline. I think it’s a combination of all these factors, plus the limitations that some of the courts have and, in anybody that does commit anyone who is put on probation, not probation, what is the word when they’re waiting for trial again … [SF: remand]. Remand, that’s right, the real danger of remand and let out on bail, pending a court case, they’ve picked up new tricks … I think what judges are allowed to mete out in terms of punishment, the quality of punishments for certain crimes. Especially in case of firearms where, and for the elderly where they get, beaten up and things like that. (pp. 75–76)

I remember years ago, there wasn’t many drugs over here. It was all like glue sniffing and stuff like that. And you only got walk around the corner now and you can ask someone for a bit of gear, they’ll give you what you want. And I don’t want my kids growing up in that sort of shit. (p. 154)

I think everyone needs to have a certain respect and for law, the police, for parents, for elder people. And I think that has disappeared. I don’t think there’s that same caring community spirit that there used to be. Crime seems to be a bit more horrendous, but I don’t know if that’s just because the media’s changed as well. I’m sure a lot of all these things have always happened, the media’s actually exposed to it a bit more. Families have become a little bit more dysfunctional just because I think women working more, you know, for a long time the traditional way, there was a solid base, and now that is not happening. I think there isn’t that same … a bus, an older person, you know, not everyone will [stand up], I’d always give my seat up for an old person, people don’t do that anymore. I just think it’s respect for your environment, for people around you. It certainly has changed. (p. 154)

These quotes speak to changes in not just crime and crime control agents such as the police and the courts, but also to changes in levels of formal (eg, schools) and informal (eg, parents) social control, community spirit, the ‘social base’ of society and implied (but not stated outright) changes in the economic base too. These things ‘have changed’, but in a way that has become worse. Because of our desire to tap into such expressive fears, but also not to over-burden the survey with the use of similar, but repeated survey questions, and because most of the prior work in this area employs stand-alone question to measure the fear of crime, we relied on an item worded How safe do you feel walking around in the area you live in after dark? (with the answer codes very safe (1), quite safe (2), a bit unsafe (3), very unsafe (4)) to measure our dependent variable. This question, as well as being one of the most commonly used, has been criticised for failing to fully capture the experience of the fear of crime (Farrall, Bannister, Ditton, & Gilchrist, Citation1997; Ferraro & LaGrange, Citation1987) and for being too vague and imprecise and for not clearly relating to crime. However, the question, and its implied vagueness, is ideal for our desires to measure the ‘expressive’ dimension to the fear of crime (and as such is more pertinent to our interests than the alternative ‘experiential’ dimension, Farrall & Gadd, Citation2004). The ‘safety walking’ question, with all of its vagueness, captures perfectly the sorts of anxieties about which people speak when they discuss ‘crime’ and ‘wrong-doing’. Relying on it also enables comparison with earlier studies.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Age was measured in whole years at the respondent’s last birthday, and gender as a binary (with males as 1 and females as 2). Our assessment of how well the respondent’s household was coping financially was their answers to the question How does the financial situation of your household now compare with what it was 12 months ago? (respondents could select one response from a lot worse (1), a little worse (2), the same (3), a little better (4), a lot better (5)). Religiosity was measured as responses to the question Would you describe yourself as extremely religious or extremely non-religious? (with the codes ranging from 1 = extremely religious to 7 = extremely un-religious). Degree education was treated as a binary (1 = yes; 2 = no). Respondents were asked if they claimed any of a series of welfare benefits and then coded as either claiming (0) or not claiming (1). All respondents were coded as living in an urban (1) or a rural (2) area. The level of deprivation for the community the respondent lived in was their Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), recoded into quartiles. The question used to identify victimisation was Have you been the victim of any of the following crimes in the last 5 years? (tick all that apply) with respondents able to tick any of the following: domestic burglary, other household theft, robbery/mugging, violence with injury, violence without injury, theft of a motor vehicle, other victimization or one of the following: none, can’t recall, don’t know, prefer not to say.

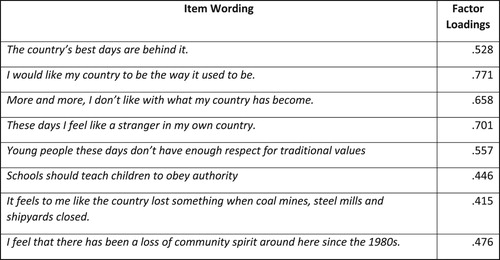

Based on two rounds of cognitive interviews and a series of survey experiments, we designed and fielded a series of questions to measure nostalgia, social and economic values and those variables more commonly associated with the fear of crime. We asked eight questions designed to gauge the degree of expressed nostalgia of respondents. All questions shared the same set of response codes.Footnote5

The nostalgia battery () asked respondents the extent to which they felt the country’s best days were behind it, if they preferred their country to be ‘the way it used to be’, the extent to which they liked ‘what their country had become’, and if they felt like a stranger in their own country. They were also asked about their feelings of remorse and/or regret about changes in the area in which they currently lived and that in which they had grown up. Undoubtedly, such opinions and assessments are formed in a number of ways and from a number of sources (including parents, grandparents, media outlets and other organisations such as schools and colleges). We have not explored the processes by which nostalgia is constructed, however, preferring to deal with the substantive impact of it on the fear of crime. These items were factor analysed to form one battery of items. The KMOFootnote6 was .818, and the eigenvalue was 3.318.

Results

Our modelling strategy was to develop a series of ordinal regression models, running closely related MLRs no less than four times (). The first model (Model I) regresses just socio-demographic variables on to the fear of crime. Model II adds to this variables relating to the area in which the respondents lived. Model III adds the victimisation variable, whilst Model IV includes the nostalgia battery which we developed (outlined in ).

Table 1. Fear of crime and nostalgia models.

What do these models tell us about nostalgia and the fear of crime? Model I suggests that variables familiar to researchers in this field were related to the fear of crime in these data too. Gender (females are more fearful than males, but see Sutton & Farrall, Citation2005), age (younger people are the more fearful relative to older people) and finances (feeling that one’s finances have got worse over the past 12 months) are all related to fear of crime; wealthier people are less fearful, being degree educated (those with degrees are less fearful) and not claiming welfare benefits (non-claimants are less fearful than those who claim) were all statistically significantly related to the fear of crime. Model I only explained about 9% of the variance in fear, however, and age ceased to be statistically significantly related to fear after this model. Entering areal data (Model II) improves the percentage of the variance explained (up to 17%), as both IMD (those in the most deprived areas had higher levels of fear) and living in an urban area (those in urban areas were also most fearful) were statistically significant. Adding victimisation (Model III) improves the percentage of variance explained, but only slightly (to 17.6%). Victimisation is, in keeping with other studies, associated with higher levels of fear. Model IV adds the nostalgia items (as one battery). This is statistically significantly associated with the fear of crime (at the <.000 level). The percentage of variance explained (when compared to Model III) does, however, increase by 2.8 percentage points. In short, the fear of crime appears to be related to gender, age, finances, degree of urbanism, deprivation (IMD), victimisation and nostalgia.

Interactions with social class

Given the changes to different social classes’ experience of socio-economic change (reviewed above) over time, we also ran analyses to assess the extent to which feelings of nostalgia were associated with different social classes. All of our 5781 respondents provided data about their occupational classification. These were recoded into working class (unskilled, semi-skilled and skilled labourers, n = 1247, 29%), lower middle-class (junior managerial, clerical, senior office workers and students, n = 1872, 44%), middle class (intermediate and higher professional, managerial and administrative staff, n = 1182, 28%) and others (casual workers, homemakers, retired, unemployed and full-time carers, n = 1480, 26%, who were dropped from further analyses).

When their average scores on our three measures of nostalgia were analysed (using Anovas), we found that the working class had the highest levels of feelings of nostalgia (.2052), the middle class the lowest (−.1962), and the lower middle-class was somewhere in between the two (−.1127). All differences were statistically significant at at least the .05 level. For example, the working class scored .2052 on the nostalgia measure, higher than the lower middle-class −.1152 (p < .000) and the middle class −.1962 (p < .000). The middle class themselves reported lower levels of nostalgia than the lower middle-class (p = .030). So, the working class appeared to report higher levels of nostalgia then the lower middle-class or the middle class.

Middle-class people tended to be older (52 years old, p < .000) than the working class (47) or lower middle-class (46) (NS). Middle-class people tended to live in places with lower IMD scores, followed by lower middle-class people and then working class with the highest (p < .000). The middle class and lower middle-class both felt that their finances had improved over the past year (mean scores of 2.95 and 2.88 respectively, NS), whilst for the working class this was lower (at 2.81, p < .000 when compared to the middle class, but NS when compared to the lower middle-class). Middle-class people felt safest (1.91), followed by the working class (2.09) and then the lower middle-class (2.12). There were no statistically significant differences between the lower middle-class and the working class, but there were between the middle class and the two other groups (p < .000). There were no statistically significant differences in terms of these groups’ rates of victimisation in the past year (which were all about .35–.36).

repeats the analyses presented as Model IV in , this time controlling for the social class of the respondents. Let us start with the middle-class respondents. For them, the fear of crime was predicted by their gender (men reporting less fear than women) and the assessment of their finances compared to the previous year (such that those who rated their finances as being in a worse state had higher levels of fear), if they were degree educated (which reduced their levels of fear), IMD quartile (those in areas with greater levels of deprivation had more fear), living in an urban area (which increased their fear) and their feelings of nostalgia (those with greater feelings of nostalgia reported more fear). For the middle class, age, religiosity, claiming benefits and victimisation were not associated with their fear of crime.

Table 2. Social class, fear of crime and nostalgia models.

For the junior middle-class, gender was again associated with fear (and again men were less fearful than were women), and younger members of the junior middle-class (those aged below 35) were more likely to report high levels of the fear of crime than were the other age bands. Assessments of one’s finances were again associated with higher levels of fear of crime such that those who felt that their finances had got worse reported more fear. Claiming benefits was also associated with higher levels of the fear of crime, as were IMD quartile and living in an urban area. For this group, nostalgia was especially strongly related to their fear of crime.

In the model for the working-class respondents in our survey, gender was again associated with the fear of crime along the same lines as for other social classes, as were assessments of their finances, their IMD and if they were living in an urban area. Being a victim of crime in the past year was associated with higher levels of the fear of crime for the working class, and feelings of nostalgia were positively associated with higher levels of the fear of crime.

Discussion and conclusion

We wish to start this concluding section with a reflection on the measurement of nostalgia. Nostalgia is a concept that can be approached—and indeed needs to be approached—in a number of different ways. The context-specific nature of what people may feel nostalgic about means that there are few universal measures of nostalgia. The closest one gets to universal measures are those outlined in relating to feelings about the/my ‘country’. As such, anyone wishing to replicate the findings we have reported on herein will need to design measures of nostalgia that are meaningful to respondents in the country or culture which they are studying. Similarly, studies undertaken with cohorts of respondents of a different age or living in a different era will need to develop measures that speak to their feelings and experiences of the pasts they have lived through (and also those they have learnt about vicariously via discussions with parents and grandparents) (see Gray, Grasso, Farrall, Jennings, & Hay, Citation2019 for a discussion of fear of crime over different political cohorts in England and Wales from 1930–2010). In periods of abrupt social and economic change (for example, the reunification of Germany during the late 1980s, or the collapse of Soviet Communism throughout the 1990s), feelings of nostalgia may be easier to identify and to design measures of. In other instances, when the changes experienced are less abrupt and therefore harder to identify (either for the populations affected, or the researchers), the tracing of such feelings and the design of measures of nostalgia may prove more complex. Nostalgia, therefore, or more precisely, the measurement of nostalgia, is an ever-changing task. Nevertheless, whilst the objects and processes about which nostalgic values are held may change and develop over time, the underlying concept has proven useful in explaining contemporary developments (see Gest, Citation2016 and Farrall, Hay, Gray, and Jones, Citation2020 for examples) and would appear to be of use in explaining the fear of crime. Nostalgia, it also needs to be acknowledged, needs some sort of ‘distance’ (usually temporal, but in some instances geographic too, in the case of migrants) in order to be identified. One can only feel nostalgic about what is no longer present. As such, research that unpacks historic processes and their contemporary manifestations (even if these are the manifestations of absence, Winlow et al., Citation2015) is best suited to studying processes of nostalgia.

The modelling we have undertaken suggests that the concept of nostalgia is an important one in explaining the fear of crime. When used in ordinal regressions, we find that the measurement of nostalgia we had constructed improved the percentage of the model explained. The nostalgia coefficients in the analyses in which we controlled for social class were highest for the lower middle-class (.461), with the working class (.288) and the middle class (.236) much lower. So those arguably least affected negatively by the changes since the 1980s (the established middle class) have the weakest relationship between nostalgia and fear (and the lowest levels of nostalgia). The lower middle-class (junior either due to their age or their position in the social and economic hierarchy) appear therefore to have the strongest relationship between their feelings of nostalgia and their fear of crime (in that nostalgia plays a larger part in explaining their levels of fear, these analyses would suggest). Age—although not statistically significant in the above analyses—appears to influence the nostalgia-fear relationship, such that it is the younger (rather than the older) members of society who exhibit the strongest relationship between their feelings of nostalgia and their fear of crime. This may seem counter-intuitive, however, as Ditton and Chadee note in their review of the literature on age and the fear of crime up to the year 2000 (Citation2003, pp. 417–420), equal numbers of studies find younger people to be more fearful as do older people to be more fearful. Moreover, older respondents (unlike younger respondents) lived through both the 1980s and the period leading up to the changes associated with that decade. For them, the problems faced by Britain during the 1970s in particular will have been experienced firsthand, whilst for younger respondents the challenges of the 1970s were more abstract. An awareness of the deficiencies of the 1970s on the part of older respondents may go some way to accounting for why it is that the nostalgia-fear relationship is stronger for younger respondents; older respondents were less nostalgic for this period and may see the 1980s as heralding a new, better arrangement for the country. Victimisation in the past year continues to predict fear of crime for the working class, but neither of the middle-class groups. However, higher IMD scores (which could be read as the perceived threat of victimisation) are related to fear of crime. Nevertheless, nostalgia appears to be a strong predictor of the fear of crime, and hence future studies ought to seek to explore this relationship in greater depth.

For several decades, researchers and policy-makers have sought to relate the fear of crime to rates of crime, victimisation, feelings of immediate (and crime-related) security, psychological processes and features of the built environment, such as human or electronic surveillance. On the basis of previous findings, many interventions involving CCTV, door-buzzer entry systems, street-lighting, visible (‘reassurance’) policing and cleaner streets with clearer sightlines have been introduced in many urban communities. Doubtless, these have gone some way, even if only temporarily, to reducing levels of fear of crime. However, this paper suggests an additional aetiology to the fear of crime—that of concerns borne out of the wider and longer-term societal and economic changes. This, at least in part, casts a new set of explanatory processes in our thinking on the, arguably, ‘more remote’ (that is, structurally located and historically embedded) drivers of the fear of crime. It suggests that the fear of crime is not as readily reduced to features of the local environment and can be read (at least in part in the United Kingdom’s recent experiences) as one of the symptoms of ‘decline’ and the narratives (from politicians on both the left and right) developed about ‘declinism’ (Gamble, Citation1981).

These results indicate that fear of crime is not only an ‘expression’ of current social arrangements, but may stretch back to assessments of social arrangements and changes to these which are rooted in the past. Our analysis points to the impermanence of foundations that may once have been considered solid, but are now mourned or longed for nostalgically. Intuitively, Goldie (Citation2004, p. 593) emphasised the backwards-facing nature of emotions:

In much of our life … the ‘event’ is not so tightly connected to the emotion that it elicits. We feel emotions in looking backwards at events that took place long ago in our own lives: nostalgia, grief, sadness, regret and shame.

Accordingly, some experiences of fear of crime may be difficult for a respondent to ‘anchor’ in their memory or to a specific event. Instead it might be the result of a collective grief connected to an unsettling past; it may be inflated by imagination, reappraised at will or invoked by memories of the social and economic climate one grew up in (Gray et al., Citation2019). For those without direct experience of what has been lost, it may be provoked by conversations with those with direct experience of the past and with what has passed into history. Emotions about crime, as explored herein, demonstrate how feelings about the present can be shaped by the past and may also influence how the future is anticipated. In sum, by employing the lens of ‘nostalgia’, we can identify how distant political and cultural undercurrents can have the enduring potential to influence perceptions and imaginations of crime. This, arguably, takes us full circle back to the somewhat murky origins of this concept and the use of it by Republican politicians in the 1960s (Ditton & Farrall, Citation2000; Farrall et al., Citation2009; Loo, Citation2009) to mobilise the ‘silent majority’ against the changes in the United States Constitution and wider society, which extended civil rights to black Americans. If this is the case, the fear of crime is as much a barometer of social and economic changes as it is a feature of crime rates, the criminal justice system or responses to crime.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the ESRC for their generous funding (as award number ES/P002862/1). At BMG Research, we extend our thanks to Rob Struthers for organising the survey fieldwork so smoothly. We would also like to extend our thanks to two anonymous reviewers for their comments on draft versions of the paper, which undoubtedly helped to improve the quality and clarity of our arguments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 UKIP collected 27.5% of the British vote in the 2014 European elections (BBC News, 2014) and 12.6% in the 2015 Parliamentary election (BBC News, 2015).

2 As distinct from the overseas past, in which Britain ‘ruled the waves’ and the Empire could be relied upon to bolster any challenges to national greatness, should these arise.

3 Despite her gender, Margaret Thatcher rarely spoke of business women and promoted few other women in her Cabinets.

4 The figure of 34% includes those who did not participate following the invitation (29%), those who started but dropped out prior to completing the survey (4%) and those who were removed for completing the survey at excessive speed (1%). Of the remaining 66%, 14% were willing to complete the survey, but were unable to, as regional targets had been met, whilst 51% were able to complete the survey in full. A range of steps were undertaken during the development of the survey. This included two pilot surveys, two rounds of cognitive interviews and a pilot survey during which questions were adapted and re-tested. A small number (200) of face-to-face interviews were conducted with groups who have low-levels of Internet usage to increase the representativeness of the sample.

5 Respondents were invited to use the following scale: strongly agree; agree; neither agree nor disagree; disagree; strongly disagree. This scale was used for all questions unless otherwise noted.

6 The KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) Test is a measure of how suited the data is for Factor Analysis. The test measures sampling adequacy for each variable in the model and for the complete model. KMO values range between 0 and 1. A rule of thumb for interpreting the statistic is that KMO values between 0.8 and 1 indicate the sampling is adequate, whilst those below 0.6 indicate the sampling is not adequate and that remedial action should be taken.

References

- Bauman, Z. (2006). Liquid fear. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bonnett, A. (2010). Left in the past. New York: Continuum.

- Dardot, P., & Laval, C. (2013). The new way of the world. London: Verso.

- Ditton, J., & Chadee, D. (2003). Are older people most afraid of crime? British Journal of Criminology, 43, 417–433.

- Ditton, J., & Farrall, S. (2000). Introduction. In J. Ditton & S. Farrall (Eds.), The fear of crime. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Ehrenreich, B. (1989). Fear of falling. New York: Pantheon.

- Eriksen, T. (2016). Overheating: An anthropology of accelerated change. London: PlutoPress.

- Eriksen, T., & Schober, E. (Eds.). (2016). Identity destabilised. London: PlutoPress.

- Farrall, S., Bannister, J., Ditton, J., & Gilchrist, E. (1997). Questioning the measurement of the ‘fear of crime’: Findings from a major methodological study. British Journal of Criminology, 37(4), 658–678.

- Farrall, S., & Gadd, D. (2004). The frequency of the fear of crime. British Journal of Criminology, 44(1), 127–132.

- Farrall, S., Gray, E., Jennings, W., & Hay, C. (2016). Thatcherite ideology, housing tenure and crime: The socio-spatial consequences of the right to buy for domestic property crime. British Journal of Criminology, 56(6), 1235–1252.

- Farrall, S., Gray, E., & Jones, P. (2020). Politics, social and economic change and crime: Exploring the impact of contextual effects on offending trajectories. Politics and Society, 48(3), 357–388.

- Farrall, S., Hay, C., Gray, E., & Jones, P. (2020). Behavioural Thatcherism and nostalgia. British Politics. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41293-019-00130-7

- Farrall, S., Jackson, J., & Gray, E. (2009). Social order and the fear of crime in contemporary times. Oxford: OUP.

- Farrall, S., & Karstedt, S. (2020). Respectable citizens – shady practices: The economic morality of the middle classes. Oxford: OUP.

- Ferraro, K., & LaGrange, R. (1987). The measurement of fear of crime. Sociological Inquiry, 57(1), 70–97.

- Flemmen, M., & Savage, M. (2017). The politics of nationalism and white racism in the UK. British Journal of Sociology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12311

- Garland, D. (2001). The culture of control. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press.

- Gamble, A. (1981). Britain in decline. London: MacMillan.

- Gaston, S., & Hilhorst, S. (2018). Nostalgia as a cultural and political force in Britain, France and Germany: At home in one’s past. London: Demos. Retrieved 7 January 2021, from https://demosuk.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/At-Home-in-Ones-Past-Report.pdf

- Gest, J. (2016). The new minority. Oxford: OUP.

- Gest, J. (2018). The white working class: What everyone needs to know. Oxford: OUP.

- Gest, J., Reny, T., & Mayer, J. (2018). Roots of the radical right: Nostalgic deprivation in the United States and Britain. Comparative Political Studies, 51(13), 1694–1719.

- Girling, E., Loader, I., & Sparks, J. R. (2000). Crime and social order in middle England. London: Routledge.

- Goldie, P. (2004). The life of the mind: Commentary on ‘emotions in everyday life’. Social Science Information, 43(4), 591–598.

- Gould, J., & Anderson, D. (1987). Thatcherism and British society. In K. Minogue & M. Middiss (Eds.), Thatcherism. London: Palgrave.

- Gray, E., Grasso, M., Farrall, S., Jennings, W., & Hay, C. (2019). Political socialization, worry about crime and antisocial behaviour: An analysis of age, period and cohort effects. British Journal of Criminology, 59(2), 435–460.

- Green, E. (1999). Thatcherism: An historical perspective. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 9, 17–42.

- Gunn, S., & Bell, R. (2002). The middle classes. London: Phoenix.

- Hale, C. (1996). Fear of crime: A review of the literature. International Review of Victimology, 4(1), 79–150.

- Jackson, J. (2004). Experience and expression: Social and cultural significance in the fear of crime. British Journal of Criminology, 44(6), 946–966.

- Lash, S., & Urry, J. (1994). Economies of signs and space. London: Sage.

- Loo, D. (2009). The ‘moral panic’ that wasn’t: The sixties crime issue in the US. In M. Lee & S. Farrall (Eds.), Fear of crime. London: Routledge.

- Pearson, G. (1983). Hooligan. London: Macmillan.

- Pearson, G. (1987). The new heroin users. London: Wiley.

- Sparks, R. (1992). Reason and unreason in left realism: Some problems in the constitution of the fear of crime. In R. Matthews & J. Young (Eds.) Issues in realist criminology (pp. 119–135). London: Sage.

- Sparks, R., Girling, E., & Loader, I. (2001). Fear and everyday urban lives. Urban Studies, 38(5–6), 885–898.

- Sutton, R., & Farrall, S. (2005). Gender, socially desirable responding and the fear of crime: Are women really more anxious about crime? British Journal of Criminology, 45(2), 212–224.

- Taylor, I., & Jamieson, R. (1998). Fear of crime and fear of falling: English anxieties approaching the millennium. European Journal of Sociology, 39(1), 149–175.

- Thorleifsson, C. (2016). Guarding the frontier. In T. Eriksen & E. Schober (Eds.), Identity destabilised (pp. 99–113). London: PlutoPress.

- Walklate, S. (2002). Issues in local community safety. In A. Crawford (Ed.), Crime and insecurity. Cullompton, Devon: Willan Publishing.

- Weinburger, B. (1995). The best place in the world. Aldershot: Scholar Press.

- Winlow, S., Hall, S., Treadwell, J., & Briggs, D. (2015). Riots and political protest. London: Routledge.

- Wright, P. (1985). On living in an old country. London: Verso.