ABSTRACT

While the historical role of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in restorative justice has been marginal, the paradigm has shifted notably since 2020, prompted by the exigencies of the pandemic. This transformation was especially visible in victim-offender mediation (VOM) programs, particularly during the critical phases of the health crisis across Europe. Despite the persistence of some restorative services in utilizing ICT tools, the scholarly discourse on this evolving landscape remains notably scant. Addressing this gap, this research adopts a qualitative approach, delving into the experiences of 26 facilitators in Spain (N = 26). Through in-depth semi-structured interviews and subsequent inductive coding and thematic content analysis, the study seeks to unravel the nuanced dynamics of employing ICTs in restorative justice and restorative mediation contexts. Specifically, the research explores their impact on communication processes, spatial dynamics, process quality, and participant security. The findings not only underscore practical implications for current practices but also open avenues for contemplating the transformative potential of digital tools in shaping the future trajectory of restorative justice. This study aims to propose valuable insights into what works, what doesn’t, and how restorative justice services could optimize their functioning within the broader criminal justice system through judicious use of ICTs.

Introduction

The use of online tools in the restorative justice field, or digital restorative justice, if preferred, is a recent phenomenon. Previous literature on this topic has consistently highlighted that both the community of professional and volunteer facilitators operating in different restorative services, as well as their users, tend to value the virtues offered by in-person interactions, relegating the possibility of using online tools to something practically anecdotal (Olalde, Citation2017). In this regard, previous findings have revealed a widespread attachment to all the elements related to the benefits of face-to-face encounters. It is perceived that in these encounters, communication occurs in a purer form, encompassing both verbal and non-verbal aspects, and providing facilitators with a wider range of tools to manage the moderation of the dialogues (Umbreit, Citation1998; Zehr & Mika, Citation2003; Choi & Gilbert, Citation2010; Bolivar, Pelikan, & Lemmone, Citation2015; Hansen & Umbreit, Citation2018). This reluctance can be easily seen in the results of several empirical works conducted in the last decade, such as the T@lk project (APAV et al., Citation2018), related to an online victim-support program, or the project by Boufard, Cooper & Bergseth (Citation2017), in which a notable number of restorative interventions for juveniles were evaluated.

However, the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic marked a turning point in the use of ICTs by restorative justice providers. With social contact restrictions in place, online platforms became the only means to continue restorative interventions, forcing facilitators to embrace this option and venture into the possibilities of digital restorative mediation. Perhaps due to the urgency of the situation, or maybe due to the potential benefits of using these tools, the experience of implementing technological solutions in the restorative justice field was very positive, as evidenced by Varona (Citation2020), Marder & Rossner (Citation2021) or Romero (Citation2024). It seems that through these forced implementation and adaptation processes, a relevant part of the facilitator’s community might have changed their perspective on the utility of those tools by gaining experience and self-confidence with its use.

In parallel to this, a debate emerged about the integration of these tools within restorative practices. As mentioned earlier, the restorative model relies heavily on the ability to communicate face-to-face the emotional aspects stemming from a conflict or a crime. However, it is also true that in a constantly evolving society and given the technological advancements that have taken place recently, the restorative justice model cannot afford to lag and forgo opportunities to employ new and innovative techniques. In an ‘adapt-or-perish’ scenario, restorative justice services and practitioners have already faced the need to adapt to ground-breaking situations, or current digital trends, in order to develop skills and practices that allow them to use such technologies to better satisfy the different demands, needs, and circumstances that participants in the restorative process may come up with. However, this raises additional obstacles, considering the novelty of the topic and the scarcity of scientific literature on it. This notably complicates the formulation of a theoretical or practical framework that can be of use towards evaluating the implementation of these online tools in this specific context. Nevertheless, there is a gradual development of research aimed at delving into this phenomenon, with the results of these studies presented below.

Literature review

ICTs and restorative justice prior to the COVID-19 pandemic

Prior to the pandemic, the study of digital restorative justice had been virtually non-existent, although some prior works and studies had explored this issue, drawing from elements of other fields, such as the use of the digital environment in previously in-person services within public administrations (Lindgren et al., Citation2019) or the implementation of online dispute resolution methods (or ODRs). The latter format is perhaps the closest to what is being studied here, as it is oriented towards conflict resolution and involves the intervention of a neutral third party (mediator). However, despite the widespread use of ODRs in certain sectors of society, especially in commerce and civil disputes (Mania, Citation2015; Rabinovich-Einy, Citation2021), its application in the field of restorative justice may be contradictory due to its focus on finding a specific solution -usually economic related- to a conflict between parties (Roche, Citation2006). Nevertheless, as we will see below, some primitive experiences of digital restorative justice have drawn characteristics from ODRs in order to implement this online environment into the field of restorative justice.

To this regard, Finn & Lavitt (Citation1994) explored initial possibilities of online restorative justice by developing an online system to aid victims of sexual offenses. The project facilitated a virtual space using forums, fostering group co-support dynamics. Although positive aspects, such as increased accessibility, convenience, and participant anonymity, were identified, challenges arose. The limited ubiquity of computers at the time and participants’ reluctance to share deeply in the digital forum due to privacy concerns were notable obstacles.

Similarly, Fileborn (Citation2017) delved into the digital sphere to understand how victims, especially those facing street harassment, sought support and potential justice online. The study highlighted the effectiveness of online platforms, particularly X (predecessor to Twitter), in providing a space for individuals to share experiences and find support within a digital community. Notably, the study suggested that online support was more effective for less complex experiences, leaving in-person support for more severe cases.

Continuing with regard to previous experiences in online victim support services, the T@lk project (APAV et al., Citation2018) represents a collaborative initiative involving victim support organizations and victimological experts from various European countries. This project explores the potential of online environments in creating telematic victim support services. It addresses critical issues, including the professional preparation of those managing these services, considerations for exclusive or complementary use with in-person services, and assessing the accessibility of these services from the user perspective. The project also delves into implications that may limit or hinder their use, such as obtaining explicit informed consent from users, ensuring privacy and confidentiality, and verifying the victim’s identity.

Turning to the specific study of online restorative justice, Conforti (Citation2018; Citation2020) contributes to the conceptualization of this field from a legal and theoretical standpoint. Although lacking empirical support, the author emphasizes the need to distinguish between digital restorative justice and ODR methods, even though considering them as a role model for online restorative practices. Conforti outlines key requirements for considering an online mediation process as restorative, including suitable participant interaction, adequate user access to platforms and technological tools, and the preservation of process confidentiality. Furthermore, Conforti categorizes tools based on their sophistication, interactivity, and security, identifying potential difficulties and barriers to the development of a digital restorative mediation model. In a similar vein, Freitas & Galain Palermo (Citation2016) and Robalo & Abdul Rahim (Citation2023) contribute to the theoretical discourse on digital restorative justice, exploring its potential application in restorative mediation, particularly in addressing cybercrimes. However, these authors acknowledge the legal and methodological challenges surrounding digital restorative justice. They raise questions about legal implications, oversight, integration into the criminal justice system, and the delicate balance between online and in-person processes. Despite the novelty and relevance of the proposed topics, the authors referenced in this paragraph only explored the issue of an online restorative justice as a mere potential hypothesis or interesting possibility, thus not relying on any empirical data or evidence.

In a more practical sense, Claes et al. (Citation2017) innovatively presented a pilot program in digital restorative justice using digital narratives as an alternative or complement to indirect mediation. This initiative engaged young individuals from a conflict-ridden neighbourhood in Brussels, creating digital materials to depict the reality of their community. This initiative highlighted several challenges in using online tools in the restorative justice field -such as the need for continuity in online restorative practices, the need for specific online tools to use, or the need to target online restorative practices to users with enough digital skills- and underscores the need for further research to overcome these barriers.

Finally, and in an educational environment, Das, Macbeth, and Elsaesser (Citation2019) proposed a digital restorative justice approach by creating a ‘virtual peace room’ for resolving conflicts in Chicago schools. This virtual space includes an evaluation process, preparatory individualized steps, and synchronous chat conversations moderated by a coordinator. The authors recognize limitations and barriers but view the initiative as an innovative tool based on restorative principles for managing various conflicts in schools.

Hence, these multifaceted initiatives collectively underscore the potential applicability of online tools across various contexts, including victim support, gender-based violence cases, or conflict resolution in schools. Even though those previous studies constitute either pilot experiences or purely theoretical works, together, they illustrate the diverse and evolving landscape of digital restorative justice, signalling the need for further empirical studies to inform its development in a nuanced and evidence-based manner, which is precisely what the present research is aimed at achieving.

The pandemic as a paradigm shift in the implementation of online restorative practices

The literature on the use of online tools in restorative justice is relatively limited but notably impactful. Key works by Marder (Citation2020), Varona (Citation2020), Millington & Watson (Citation2020), and Marder & Rossner (Citation2021) have explored this emerging phenomenon. Additionally, empirical insights have been contributed by Bonensteffen et al. (Citation2022) and Romero (Citation2024), drawing from interviews with facilitators and participants in the field. The findings collectively suggest that the integration of online tools in restorative justice processes can introduce a series of improvements, particularly in terms of logistics, communication flow, and enhancing participant commitment to the restorative process.

Varona’s (Citation2020) work in Spain offers a legal and regulatory perspective, examining various texts at both national and international levels related to restorative justice. Surprisingly, the author found no specific mentions of online restorative processes in existing regulations, despite the prevalence of references to conducting other judicial procedures through telematic means. Varona highlights the unique considerations of online dispute resolution (ODR) methods, emphasizing the distinction between ODR and digital restorative justice. The author also underscores the need to address implications related to confidentiality and process security when integrating information and communication technologies (ICT) into restorative processes.

Marder’s extensive contributions (Citation2020a; Citation2020b; Citation2020c) include the coordination of a series of meetings and seminars within the European Forum for Restorative Justice (EFRJ). These discussions involved facilitators from various countries sharing their experiences during the challenging stages of the pandemic. The insights derived from these meetings underscored the adaptations made by restorative justice services forced by the health context. Among the conclusions, the importance of adapting information for participants in online mediation processes and the necessity of having the right technical resources for effective online mediation were highlighted. The positive perceptions of using telematic tools, particularly on platforms like Zoom, and the necessity of training participants in virtual mediations were key takeaways. Marder’s contributions significantly shaped the methodological design of subsequent research projects, emphasizing the importance of understanding the challenges and potential of digital restorative justice.

Millington & Watson (Citation2020) take a practical approach by developing a guide of best practices for digital restorative justice in England and Wales. The guide, created for the organization ‘Why Me?,’ resulted from the evaluation of a pilot test involving different video conferencing platforms and preparation/mediation structures, providing several recommendations. It addresses challenges in online communication and recommends considering aspects related to confidentiality, security, and the emotional content of digital processes. Importantly, the guide acknowledges the potential limitations of access to technology and emphasizes the need for facilitators to assess the appropriateness of online mediation on a case-by-case basis.

Marder & Rossner’s (Citation2021) work revisits the topic, compiling information on the experience and innovation of different restorative justice services in Australia and Europe. Despite the easing of pandemic restrictions, there is a perception among professionals that users continue to prefer online methods. The authors recognize limitations, including the digital gap, facilitator anxiety, and potential technology-induced inequalities. However, they also emphasize advantages such as geographical flexibility, reduced carbon footprint, and more flexible mediation models. The work stresses the need to adapt or design new protocols for the use of online tools in restorative practices, anticipating the normalization of these technologies.

Also Goldberg & Henderson (Citation2021) contributed insights from a restorative justice program in Longmont, Colorado, USA, during the pandemic. Despite a decrease in referrals due to COVID-19, the program managed around fifty cases, with approximately 80% conducted online. The authors underscore the importance of prior training for online restorative mediations, detailing a comprehensive methodology based on restorative circles through the Zoom platform. Their findings reveal successful outcomes, volunteer satisfaction, and the unexpected quality of communication through digital channels. However, they also identify the potential for technology to exacerbate inequalities due to the digital gap present in society.

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the digital transformation of restorative justice, necessitating the adoption of ICTs for the conduction of remote processes. This shift presents both opportunities and challenges, emphasizing the importance of an ethical, responsible, and interdisciplinary approach. Addressing legal, ethical, and design implications globally is crucial. While technology enhances access to justice, considerations of privacy, security, confidentiality, and comprehensive training for professionals and participants are vital for the evidence-based use of online restorative practices.

The present study

Consequently, the study outlined below aims to contribute to generate evidence-based knowledge on a new and innovative phenomenon, such as the use of ICTs in the field of restorative justice. Therefore, the proposed goals of the research are to determine the facilitators’ perception of these technologies within the restorative justice services included as case studies, to identify differences and similarities between in-person and digital restorative mediation, and to assess the feasibility and applicability of these tools in the context of restorative practices in the medium and long term. To address these objectives, empirical information related to the experiences of facilitation professionals operating in Spain has been compiled. A qualitative research approach has been employed through the conduction of open interviews with facilitators from the restorative justice services in the regions of Catalonia, Navarre, and the Basque Country (Spain),

All of this crystallizes in the following research questions:

What are the main characteristics of digital restorative justice?

What are the main differences and similarities between digital restorative mediation and in-person restorative mediation?

Are ICTs applicable in the restorative justice context and their use viable in restorative justice processes in the medium- and long-term?

Methods

Procedure and setting

The sample participation was achieved through institutional contacts with professionals from the three case studies (regions of Navarre, Catalonia, and the Basque Country in Spain), employing purposive sampling (Palys, Citation2008), followed by subsequent snowball sampling (Creswell, Citation2007) until saturation point (Flick, Citation2007; O’Reilly & Parker, Citation2013). The selection of the three restorative services that comprise the case studies was based in the robustness, experience, and implantation of those restorative programs in the Spanish context, counting all three with more than twenty years of experience (Tamarit, Citation2012). Inclusion/exclusion criteria for individual study participation were a) being an active facilitator member of one of the teams in the case study programs, b) active in these teams for at least 6 months before the health-related lockdown (March 2020), and c) having used some type of online tool during the COVID-19 lockdown. Facilitators were chosen as the primary information source of information due to their indispensable role in the construction and development of the restorative process (Umbreit & Vos, Citation2000; Bazemore & Schiff, Citation2005; Van Camp & Wemmers, Citation2013) and as accessible figures, providing a longitudinal view of the adaptation and use of specific tools (ICTs). Placing facilitators in a central role of this research allowed an exploration of the dynamics and implementation of online tools throughout the restorative justice model. Moreover, this research serves as an initial empirical approach to a phenomenon that is still underexplored, and to which the experiences and perceptions of these professionals, who play a crucial role in ensuring the management, moderation, and facilitation of these restorative processes (Suzuki & Wood, Citation2017), is indispensable.

Ethically, participant confidentiality was ensured through a) signed informed consent committing to guaranteeing this right, and b) anonymization and exclusion of identifying information during interview transcription (omitting names, program details, or geographical area). Additionally, the research project underwent review by the university’s Ethics Committee, obtaining a positive resolution.

Interviews took place at organization offices, judicial headquarters, private offices, and public places. All the interviews were conducted in Spanish, transcribed verbatim and translated into English for the purpose of this study.

Sample and data collection

The examined sample comprises 26 restorative justice facilitators (N = 26) involved in restorative justice programs in Spain. These programs are recognized for their extensive implementation and/or institutionalization in Spanish context. The distribution of participants is as follows: 6 professionals (n = 6) from the Restorative Justice Program of the Department of Justice of the Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalonia, Spain); 6 professionals (n = 6) from the Penal Execution and Restorative Justice Service of the Government of Navarre (Navarre, Spain); 14 professionals (n = 14) from the Restorative Justice Service of the Department of Justice of the Government of the Basque Country (Euskadi, Spain). Demographically, the sample is relatively diverse, comprising 50% women (n = 13) and 50% men (n = 13), with an average age of approximately 41 years (M = 41.1, SD = 7.2). Regarding interview duration, the average was around fifty minutes, with the longest interview lasting one hour and seventeen minutes and the shortest lasting thirty-four minutes (M = 49.7, SD = 9.8, Min. = 34 Max. = 77).

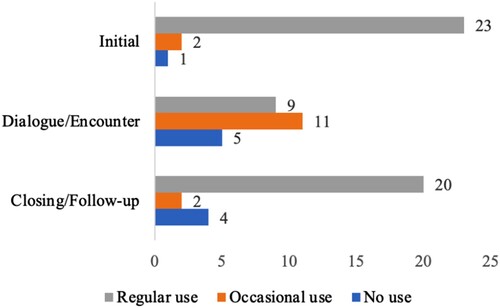

The data collection tool was configured as a semi-structured open questionnaire, which consisted of 26 items divided into five main sections (introduction, initial phase of the process, mediation/dialogue phase, closing phase, and conclusion/reflection). The different items are aimed at gathering practical information about the implementation and user experience of professionals with online tools, as well as addressing issues related to perceived utility, satisfaction level, and other subjective elements regarding the restorative process. The main items were defined following the logical structure of the mediation process (initial contact with participants, preparation phase, dialogue/encounter phase, and closure/follow up phase). Examples of the questions employed are those related to the prevalence and characteristics of use of ICTs among restorative justice practitioners (‘What kind of online platforms have you employed in your practice and how often have you used them?’) the relevance of communication in the restorative process (‘Do you perceive any differences in the willingness to participate in the restorative process when transmitting information remotely?’), its relationship with the process development (‘What would you say are the difficulties of online communication in the restorative process?’), and the potential outcomes of the process, such as ‘How has your relationship with ICT changed since COVID-19?’ or ‘What strategies do you use or have you used to adapt to online communication?’.

Analysis

In this research, a qualitative approach was employed, utilizing semi-structured interviews with restorative justice facilitators as the primary data source. The intentional focus on facilitators stems from the recognition of their underexplored role in previous literature and their significant influence not only in executing the restorative process but also in shaping associated tools and methodologies, as discussed in section 4.1. Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) was applied to the collected data, complemented by elements of grounded theory during the codification phase (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998; Citation2002; Creswell, Citation2013). The codification process encompassed three phases (open, axial, and selective), aiming to distil themes and subthemes from the initial database and facilitate the synthesis of research objectives in response to the research questions.

Methodological limitations

This study has certain methodological limitations. First, relying solely on facilitators for information may be one-sided. Future research should include participant perspectives for a comprehensive view. Second, the research context, post-pandemic in 2021-2022, may evolve; periodic reassessment is advised. Lastly, while qualitative research is valuable, the novelty of the topic suggests a need for a mixed-methods approach. Unfortunately, data limitations prevented this, highlighting the necessity for accessible quantitative data to enhance empirical evidence in the restorative justice field.

Results

Characteristics of online restorative justice

To initiate the results section, and related to the first of the research questions, the main findings regarding the most relevant characteristics of digital restorative mediation, the studied sample confirmed a high implementation of these tools, with over 96% of participants stating that they use some of these tools at some point in the process. Regarding the frequency of use, 30% use them regularly or very regularly, another 30% use them in approximately half of their cases, while 35% use them sporadically, and a residual 5%, corresponding to a single participant, does not use them at all. Concerning the type of tool, the results showed that smartphones are the most commonly used, primarily through messaging apps, followed by computers, using video call platforms.

Regarding these most common used platforms or applications, results showed how WhatsApp and Telegram are predominantly used in the messaging apps sphere, while Zoom, Meet, or Skype are the primary choices for video conferences. As Interviewee E1 states, these results should not be surprising as they clearly correlate with platforms that have a higher adoption within western societies, and that both users and facilitators are more familiar with:

‘The use of WhatsApp, in the end, is not casual … it is the most accessible contact channel, you know? Ultimately, practically everyone with a moderately modern phone has WhatsApp, and this is important because it allows for greater contact’ (Interview E1, 2021)

The obtained data highlights a lack of consistent criteria among facilitators for employing digital tools in the restorative process, showcasing a high degree of discretion in their use. Three primary scenarios emerged: a) overcoming geographical barriers for participants residing far from the service; b) addressing health-related mobility issues; and c) addressing socio-economic challenges hindering participation, such as work constraints or transportation costs:

‘I use what could be called geographical criteria. That is, when one or both parties reside in a location far from our headquarters. Also, with the whole health issue, to prevent contagion and the like. And not just COVID, you know? Also, people who have some other type of health problem.’ (Interview E14, 2022)

‘Even though I still prefer face-to-face interactions, now I usually always offer the possibility to do at least some part of the process online, if that suits the needs of the participants. For example, recently I had this case in which one of the involved parties was admitted in a rehab center … the possibility of having him come all the way here didn’t even cross my mind’ (Interview E9, 2022)

‘Quite often they [the participants] say, ‘Hey, look, I’m okay with mediation, but I don’t want to be in the same space with the other party at all.’ In those cases, the use of video calls can be a very, very useful tool if the right circumstances are present because it’s a middle ground between a joint in-person and an indirect session. Some people might say, ‘I don’t want to be in the same room as this person,’ but with a screen in between, they might be okay with it. In fact, a lot is gained by doing it this way, and in some cases, it has paved the way for them to meet in person later on’ (Interview E13, 2022)

Differences and similarities between online and face-to-face restorative justice

Regarding the distinctions between digital and in-person restorative processes, results reveal that key differences lie in communication fluidity, quality, accessibility, and participation. Digital processes pose challenges, hindering smooth communication and emotional content transmission due to difficulties in perceiving non-verbal cues. Facilitators have highlighted issues like the absence of human warmth or the inability to utilize physical resources. In the digital context, capturing nuances in non-verbal communication becomes pivotal for facilitators, emphasizing its role in moderation, management, and participant engagement within the restorative process. This might have an impact on how the facilitator manages the meetings, as Interviewee E25 describes:

‘Something I realize is that perhaps I have been much more directive, strict with the rules and regulations of the sessions, compared to how I am in the office. In the end, the fluidity that I mentioned before is generated by a bond of trust that you must build beforehand. Here in person, I have more resources to generate that, right? From touching, eye contact, body language … and online, this is more challenging, so you must be … that: more directive.’ (Interview E25, 2022)

‘When interacting face-to-face, the emotional connection—the ability to see, touch, and interpret body language in a more spontaneous and dynamic way—these aspects are indeed more challenging through a screen. In an online session, you lose some of this. For example, it also complicates the logistics of taking a pause for any reason, whether one of the parties needs a moment or a break. It’s much simpler logistically when you’re face-to-face.’ (Interview E5, 2021)

‘[ICTs] allow us to communicate with users in a much more agile way, so that they can quickly understand what all this is about and decide if they want to participate or not. In a way, it saves us time, both for them [users] and for us. The use of video calls in this phase gives us an extra quality in transmitting information in a non-face-to-face manner, especially if you compare it with how we used to do this before … ’ (Interview E22, 2022)

Table 1. Strategies and resources to control the communicational flow during encounter phase.

In contrast, regarding the process accessibility, results show the advantages of the online environment and the potential of a digital restorative space over traditional methods. The virtual setting offers tailored solutions to diverse needs and circumstances, enhancing participant engagement. The use of ICTs in creating an online restorative space is highly valued, providing a more humanized space, particularly beneficial for victims. This digital approach represents a significant improvement compared to indirect mediation processes in terms of possibilities and quality:

‘For me, the main advantage [of ICTs] is that it gives us the possibility to adapt much more to the needs of the individuals, and it allows us to work on cases that would have escaped us or would have been unfeasible before all this [before March 2020]’ (Interview E8, 2022)

‘We have also observed that some people may feel more secure with the physical distance provided by video calls, especially those individuals more affected by the incident we are mediating. In these cases, the video call gives us a tremendous advantage because individuals who may not have wanted to participate in the process now see it as an option’ (Interview E3, 2021)

Applicability and viability of online tools in the restorative justice model

Addressing the third research question, the results showed a high perception of utility in the sample of facilitators studied, as long as ICTs play a subsidiary, complementary, or alternative role to in-person interactions. It is worth highlighting that there was an initial surprise at the positive reception and the myriad of possibilities offered by these technologies. Considering the initial literature review, it is relevant to highlight once again how historically the use of ICTs in restorative justice had been marginal due to a lack of necessity for their promotion, but also due to a low acceptance among professionals. Therefore, it is interesting to see how this forced use and adaptation to the online environment during the lockdown period prompted a shift in this trend, causing a significant portion of the interviewed professionals to reposition themselves:

‘At first, I wasn’t sure about using technology, and I thought this would only be a temporary solution during the lockdown. Then, I had to facilitate a case with quite complex emotional issues, and I said, ‘Wow!’ It’s true that you have to think everything through and figure out how to do this and that; there’s more preparation, maybe because I lack experience, of course. But it surprised me positively, and although I don’t think it’s useful for every case, it’s a very interesting option to work with’ (Interview E25, 2022)

‘Between you and me … I don’t think there is any difference with the in-person process … if you carry a hidden recorder … or even your phone, you could record the session, and I wouldn’t know. But well, it’s absurd; I don’t think anyone—or I haven’t encountered anyone—who might want to misuse the content of what we talk about here. Besides, they wouldn’t have anywhere to go to with that’ (Interview E16, 2022)

‘It would be ideal to have a specialized mediation platform that takes into account these security aspects but allows us to have everything in one place. A platform where we can send documentation, enables parties to sign PDFs, for example, and provides resources for conducting joint sessions. I think something like this would help us a lot and make it easier for us to intervene online’ (Interview, E8, 2022)

‘There was a colleague who, at a certain point, found that … in about 80% of his cases, the only online access medium his users had was a mobile phone. And, of course, no matter how many protocols or platforms you want to implement, it’s ridiculous to consider it. You always have to offer the option of coming here in person. When we talk about the digital divide, I can assure you that it does exist, even if we don’t always see it. But we have seen it very clearly.’ (Interview E4, 2021)

Table 2. Needs detected regarding the implementation and establishment of ICTs in restorative justice services.

In summary, the results obtained underscore the need for training in both established and emerging online platforms and tools, with a primary focus on those with potential use within the restorative justice landscape. Overall, facilitators perceive online tools as highly beneficial, particularly when complementing in-person interactions, detecting a positive shift in attitudes after the pandemic experience that challenges historical scepticism.

Discussion

Transitioning now into the discussion of the obtained results, several implications for the restorative justice practice can be derived from the present findings.

Primarily, the study reaffirms the paramount importance of the preparatory phase, as crucial for users’ initial contact, process adherence, and planning for subsequent phases (Prenzler & Hayes, Citation1998; Nuguent, Williams, & Umbreit, Citation2004). A notable revelation is the newfound significance of online tools in this phase, possibly influenced by experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. These insights align with the historical underpinning of restorative practices, emphasizing adaptability to the environment and the necessity for a responsive approach beyond conventional criminal justice systems (Van Ness, Morris, & Maxwell, Citation2001; Braithwhite, Citation2003; Velez et al., Citation2021). The professionals’ adaptability to the virtual context during the pandemic reflects the demand for restorative justice to be adaptable and responsive, corroborated by positive results (Varona, Citation2020; Marder & Rossner, Citation2021; Romero, Citation2024).

Contrary to prior perceptions of a lack of ambition in the restorative model, the integration of technology is showcased as beneficial, correcting reluctance to adapt to an increasingly digitalized society (Bonensteffen et al., Citation2022). Online tools prove instrumental in the closure and follow-up phase, streamlining procedural tasks and enhancing organizational efficiency, aligning with the positive outcomes noted by Bonensteffen et al. (Citation2022).

However, the study underscores the limited utility of ICTs in the joint encounter or dialogue phase, underscoring the enduring significance of in-person contact. Factors contributing to this perception include a lack of experience with ICTs, challenges in translating mediation strategies online, and difficulties in perceiving or utilizing non-verbal communication in digital sessions. These elements are relevant to reject any approach that might suggest any assimilation between online restorative practices and ODRs (Freitas & Galain Palermo, Citation2016). Given the emotional nature of restorative justice (Rossner, Citation2017) it is important to emphasize again the significant differences between the two types of practices (Romero, Citation2024). Therefore, and despite that the restorative model can draw insights from certain aspects of ODRs when implementing online tools (for example streamlining bureaucracy, the immediacy in the communication, etc.), the results of this study underscore once again the vast differences between both models.

Regarding the criteria for using online tools, the study identifies patterns related to geographical location, socio-health circumstances, socio-economic aspects, or social vulnerability, aligning with the restorative model's adaptability and capacity for tailored responses (Zehr, Citation2015).

The study addresses the dilemma surrounding victims’ right to participate in a restorative process (Kirkwood, Citation2010), echoing supranational directives emphasizing accessible and inclusive restorative services (Directive 2012/29/EU; Recommendation CM/Rec/8, 2018). Persistent criticism of the lack of accessibility to restorative justice services is acknowledged, attributed partly to the functioning of the criminal justice system and cultural factors (Laxminarayan et al., Citation2014; Wood & Suzuki, Citation2016; Marder, Citation2022; Romero, Citation2023).

While ICTs enhance communication between users and facilitators, improving accessibility, concerns about the digital gap are also highlighted. The study identifies reservations among professionals regarding extensive technology use, citing limitations in internet access and digital skills. Facilitators advocate for ICTs as a complement or alternative to in-person mediation, emphasizing their subsidiary role (Bonensteffen et al., Citation2022). Understanding the context in which the study was conducted, where online was the only possible option due to physical contact restrictions, this seems nowadays more feasible, thus securing that the preferences of all potential users are well taken into consideration.

However, and contrary to previous assertions (Varona, Citation2020), this research underscores the applicability and viability of online tools in the restorative process, as a more nuanced approach suggests that a gradual incorporation of these tools could help to expand the operational range of restorative services, improving victims’ participation without limiting their rights, as Dzur (Citation2003) suggested two decades ago. The results obtained suggest the vision of a future where online tools coexist with traditional practices, enhancing flexibility and accessibility based on identified needs, and aligning with supranational directives and policies. Despite this study being conducted in a pandemic or recent post-pandemic context, its implications are still relevant for the current restorative practice. In this sense, and as mentioned above, the use of technology in the field of restorative justice has proven to be viable, placing its role as a complement or an alternative to cases where direct contact is not possible or advisable. This may allow for an increase in the operational range of restorative services and programs in the medium and long term, facilitating access for more people while streamlining their participation. Furthermore, the results obtained in this study also pave the way to explore new types of intervention, such as hybrid restorative processes (part online and part in-person), as well as models of restorative practices halfway between traditional mediation and shuttle mediation, increasing the resources that the latter can employ, such as audio-visual elements or synchronous communications.

Conclusions and recommendations

Coming to the final part of this paper, the main conclusions of this research are presented below.

Firstly, it has been determined that the online environment and ICT do not aim to replace traditional restorative practices but rather serve as complements in certain phases of the process or as an alternative in specific contexts when in-person interaction is not possible or advisable. On the other hand, it has been observed that the primary differences between digital restorative mediation and in-person mediation lie in their communicational aspects, emphasizing the quality of communication and associated strategies to ensure it. Additionally, online tools can be employed to encourage and ensure participation in the restorative process, proving differentially useful in cases where particularly vulnerable victims wish to engage in such a process. It is also concluded that the subjective opinion or perception of facilitators regarding ICT is not a decisive factor for their use; rather, the potential benefits will take precedence in cases where recommended. This implies that online tools are viable and applicable to the restorative process, although it must be ensured that the needs identified by the research are considered. Finally, with all this, it can be concluded that there has not been a shift in the restorative justice model towards a digital restorative justice, but rather towards a model where ICTs can play a useful role, contributing to improving accessibility and participation in restorative justice programs.

Recommendations include investing in cross-cutting training for professionals, ensuring proper resources, and proactive sharing of best practices for restorative justice services. Facilitators are advised to actively incorporate ICTs, particularly in initial or final phases, adapting their use based on evident needs. Individualized treatment and strategies for quality communication in the online environment are essential.

Author BIO.docx

Download MS Word (12.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- APAV. (2018). T@LK handbook for online support for victims of crime. https://apav.pt/publiproj/images/yootheme/PDF/Handbook_TALK.pdf

- Bazemore, G., & Schiff, M. (2005). Methodology for the qualitative study and description of conference stages and phases. In G. Bzemore, & M. Schiff (Eds.), Juvenile justice reform and restorative justice (pp. 136–152). Taylor & Francis.

- Bolivar, D., Pelikan, C., & Lemonne, A. (2015). Victims and restorative justice: Towards a comparison. In I. Vanfraechem, D. Bolivar, & I. Aertsen (Eds.), Victims and restorative justice (pp. 170–199). Routledge.

- Bonensteffen, F., Zebel, S., & Giebels, E. (2022). Is computer-based communication a valuable addition to victim-offender mediation? A qualitative exploration among victims, offenders and mediators. Victims & Offenders, https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2021.2020946

- Bouffard, J., Cooper, M., & Bergseth, K. (2017). The effectiveness of various restorative justice interventions on recidivism outcomes among juvenile offenders. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 15(4), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204016647428

- Braithwhite, J. (2003). The fundamentals of restorative justice. en S. Dinnen, A. Jowitt, & T. Newton (Eds.), A kind of mending: Restorative justice in the Pacific Islands (pp. 35–45). The Australian National University.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Choi, J. J., & Gilbert, M. J. (2010). Joe everyday, people off the street’: A qualitative study on mediators’ roles and skills in victim–offender mediation. Contemporary Justice Review, 13(2), 129–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282581003750145

- Claes, E., Leckhar, I., Huysmans, M., & Gulinck, N. (2017). Digital stories and Restorative Justice. en I. Aertsen, & B. Pali (Eds.), Critical restorative justice (pp. 211–240). Hart Publishing.

- Conforti, O. D. (2018). How to improve the criminal law though the online restorative justice a new field within the ODR genre, an opportunity for all those who are affected by a crime, conditions for its success. International Journal of Recent Scientific Research, 9(2(B)), 23831–23839. https://doi.org/10.24327/ijrsr.2018.0902.1545

- Conforti, O. D. (2020). Prácticas restaurativas online en el ámbito penal. en O. Fuentes (dir.), P. Arrabal (coord.), Y. Doig (coord.), A. Ortega (coord.), & I. Turégano (coord.) (Eds.), Era Digital, Sociedad y Derecho (pp. 481–493). Ed. Tirant lo Blanch.

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Five qualitative approaches to inquiry. In J. W. Creswell (Ed.), Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (pp. 53–84). SAGE Publications.

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th Edition. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Das, A., Macbeth, J., & Elsaesser, C. (2019). Online school conflicts: Expanding the scope of restorative practices with a virtual peace room. Contemporary Justice Review, 22(4), 351–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580.2019.1672047

- Dzur, A. W. (2003). Civic implications of restorative justice theory: Citizen participation and criminal justice policy. Policy Sciences, 36(3), 279–306. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:OLIC.0000017480.70664.0c

- Fileborn, B. (2017). Justice 2.0: Street harassment victims’ use of social media and online activism as sites of informal justice. The British Journal of Criminology, 57(6), 1482–1501. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azw093

- Finn, J., & Lavitt, M. (1994). Computer-based self-help groups for sexual abuse survivors. Social Work With Groups, 17(1-2), 21–46. https://doi.org/10.1300/J009v17n01_03

- Flick, U. (2007). An introduction to qualitative research. SAGE Publications.

- Galain Palermo, P., & Freitas, P. (2016). Restorative justice and technology. In P. Novais, & D. Carneiro (Eds.), Interdisciplinary perspectives on contemporary conflict resolution (pp. 80–94). IGI Global.

- Goldberg, J., & Henderson, D. (2021). An ode to volunteers: Reflections on community response through restorative practices before and after COVID-19. The International Journal of Restorative Justice, 4(2), 315–320. https://doi.org/10.5553/TIJRJ.000080

- Hansen, T., & Umbreit, M. (2018). State of knowledge: Four decades of victim-offender mediation research and practice: The evidence. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 36(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.21234

- Kirkwood, S. (2010). Restorative justice cases in Scotland: Factors related to participation, the restorative process, agreement rates and forms of reparation. European Journal of Criminology, 7(2), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370809343036

- Laxminarayan, M., Aertsen, I., & Biffi, E. (2014). Accessibility and initiation in restorative justice. European Forum for Restorative Justice: Leuven. https://www.euforumrj.org/sites/default/files/201911/accessibility_and_initiation_of_rj_website.pdf

- Lindgren, I., Ostergaard, C., Hofmann, S., & Melin, U. (2019). Close encounters of the digital kind: A research agenda for the digitalization of public services. Government Information Quarterly, 36(3), 427–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.03.002

- Mania, K. (2015). Online dispute resolution: The future of justice. International Comparative Jurisprudence, 1(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icj.2015.10.006

- Marder, I. (2020a). Restorative justice and COVID-19: Responding restoratively during/to the crisis. A report from the first European meeting on restorative justice and COVID-19. www.euforumrj.org/en/restorative-justice-and-COVID-19-responding-restoratively-duringto-crisis (accedido por última vez 21 de marzo de 2023)

- Marder, I. (2020b). A restorative transition to the post-lockdown world. A report from the third European meeting on restorative justice and COVID-19. www.euforumrj.org/en/restorative-transition-post-lockdown-world (accedido por última vez 21 de marzo de 2023).

- Marder, I. (2020c). What does justice look like during and after COVID-19? A report from the fourth European meeting on restorative justice and COVID-19. www.euforumrj.org/en/what-does-justice-look-during-and-after-COVID19 (accedido por última vez 21 de marzo de 2023).

- Marder, I. (2022). Mapping restorative justice and restorative practices in criminal justice in the Republic of Ireland. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 70, 100544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2022.100544

- Marder, I. D., & Rossner, M. (2021). Restorative justice during and after COVID-19. The International Journal of Restorative Justice, 4(2), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.5553/TIJRJ.000079

- Millington, L., & Watson, T. (2020). Virtual restorative justice: Good practice guide. Why Me? https://why-me.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Why-Me_-Virtual-Restorative-Justice-with-video-links.pdf

- Nugent, W. R., Williams, M., & Umbreit, M. S. (2004). Participation in victim-offender mediation and the prevalence of subsequent delinquent behavior: A meta-analysis. Research on Social Work Practice, 14(6), 408–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731504265831

- Olalde, J. A. (2017). 40 Ideas para la práctica de la justicia restaurativa en la jurisdicción penal. Madrid.

- O’Reilly, M., & Parker, N. (2013). Unsatisfactory saturation’: A critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 13(2), 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112446106

- Palys, T. (2008). Purposive sampling. In L. Given (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (pp. 697–698). Sage.

- Prenzler, T., & Hayes, H. (1998). Victim-offender mediation and the gatekeeping role of police. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 2(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/146135570000200103

- Rabinovich-Einy, O. (2021). The past, present, and future of online dispute resolution. Current Legal Problems, 74(1), 125–148. https://doi.org/10.1093/clp/cuab004

- Robalo, T. L. A., & Abdul Rahim, R. B. B. (2023). Cyber victimisation, restorative justice and victim-offender panels. Asian Journal of Criminology, 18(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-023-09396-9

- Roche, D. (2006). Dimensions of restorative justice. Journal of Social Issues, 62(2), 217–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2006.00448.x

- Romero Seseña, P. (2023). El desarrollo de la Justicia Restaurativa en España y su prohibición en casos de violencia sexual y de género: Reflexiones a partir de la LO 10/2022 y la nueva Ley Foral 4/2023 de Navarre. Revista de Derecho Penal y Criminología, 30, https://doi.org/10.5944/rdpc.JUNIO.2023.37637

- Romero Seseña, P. (2024). Applicability and uses of ICTs in restorative justice: Online restorative mediation experiences in Spain [Doctoral dissertation]. Universitat Oberta de Catalunya.

- Rossner, M. (2017). Restorative justice in the 21st century: Making emotions mainstream. In A. Liebling, S. Maruna, & L. McAra (Eds.), The oxford handbook of criminology (pp. 967–989). Oxford University Press.

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (2002). Bases de la investigación cualitativa: técnicas y procedimientos para desarrollar la teoría fundamentada (1. ed.). Editorial Universidad de Antioquia.

- Suzuki, M., & Wood, W. R. (2017). Restorative justice conferencing as a ‘holistic’ process: Convenor perspectives. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 28(3), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2017.12036075

- Tamarit Sumalla, J. M. (coord.). (2012). La justícia restaurativa: desarrollo y aplicaciones. Editorial Comares.

- Umbreit, M. (1998). “Restorative Justice through victim-offender mediation: A multi-site assessment.” Western Criminology Review Vol. 1 n° 1. [Online]. http://www.westerncriminology.org/documents/WCR/v01n1/Umbreit/umbreit.html.

- Umbreit, M., & Vos, B. (2000). Homicide survivors meet the offender prior to execution. Homicide Studies, 4(1), 63–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767900004001004

- Van Camp, T., & Wemmers, J.-A. (2013). Victim satisfaction with restorative justice: More than simply procedural justice. International Review of Victimology, 19(2), 117–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269758012472764

- Van Ness, D., Morris, A., & Maxwell, G. (2001). Introducing restorative justice. en A. Morris, & G. Maxwell (Eds.), Restorative justice for juveniles: Conferencing, mediation and circles (pp. 3–16). Hart Publishing.

- Varona Martinez, G. (2020). Digital restorative justice, connectivity and resonance in times of COVID-19 Revista de Victimología, n°. 10/2020 pp. 9-42. http://www.huygens.es/journals/index.php/revista-de-victimologia/article/view/160/61.

- Velez, G., Butler, A., Hahn, M., & Latham, K. (2021). Opportunities and challenges in the age of COVID-19: Comparing virtual approaches with circles in schools and communities. In T. Gavrielides (Ed.), Comparative restorative justice (pp. 131–151). Springer.

- Wood, W. R., & Suzuki, M. (2016). Four challenges in the future of restorative justice. Victims & Offenders, 11(1), 149–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2016.1145610

- Zehr, H. (2015). The little book of restorative justice: Revised and updated. Good Books.

- Zehr, H., & Mika, H. (2003). Fundamental concepts of restorative justice. In E. En McLaughlin, E. Fergusson, G. Hughes, y L. Westmarland (Eds.), Restorative justice: Critical issues (pp. 40–43). Sage.