ABSTRACT

Peterson, Norway, was a former cellulose factory that is in the process of being transformed into new usage. A landmark at the premises is the “digester,” a high-rise steel structure used to make cellulose before the factory closed in 2012. The digester is now facing an uncertain material future, but this does not keep it from being represented and remembered in different ways. Peterson is also known for its elephant logo, which has been resemiotised from a signboard into a three-dimensional elephant sculpture in blank steel. As we will demonstrate, this and other uses of semiotic resources may be viewed as part of a transformative process that indicates looking forward into a post-industrial society where communication is more important than cellulose production. However, as we will demonstrate, this interpretation does not necessarily match the intention of the sign producer.

Introduction

Many industrial landscapes are being transformed for new usage in today’s post-industrial economies. Urban entrepreneurs seek to create unique senses of places and, as part of this goal, cities are, “increasingly semiotised and mediatised” (Järlehed Citation2021, 7). However, different people have different feelings about the best ways to reconcile industrial heritage (Edensor Citation2005, 3), as it may “afford” different things to different people (Gibson Citation1986).

There is a long history of scholars discussing people’s attachment to landscapes and places (Duncan and Duncan Citation2004; Skrede and Andersen Citation2019, Citation2021; Casey Citation1997; Feld and Basso Citation1996). Grubbauer (Citation2014, 336–337) noted that urban scholars have been concerned with architecture as representations to demonstrate that there exist multiple and contested readings of architecture. However, architects, designers, and planners may also use complex “sociosemiotic strategies” to direct users’ interpretation in specific directions for social, cultural, and political purposes, as Nanni and Bellentani (Citation2018, 379) have demonstrated with reference to Fascist architecture and city planning under the Mussolini regime.

There is a growing body of literature investigating the social semiotic dimension of heritage. Abousnnouga and Machin (Citation2011, Citation2013) have analysed the “language” of several British war memorials, and Krzyżanowska (Citation2016) have analysed how we can “read” counter-monuments in urban spaces. She demonstrates how we can interpret Stolpersteine, or stumbling blocks, installed in urban pavements to commemorate the victims of National Socialism, and especially the Holocaust. Waterton has analysed English heritage custodianship brochures by means of concepts from Kress and van Leeuwen (Citation2006), and demonstrated how a series of images of heritage sites are able to evoke a sense of “similarity” rather than difference, and assert the monumental, grand, and national above the local and regional (Waterton Citation2010). Visual representations are able to construe specific “sights of sites” (Waterton and Watson Citation2014, 5); however, it is important to note that deploying certain semiotic resources does not suffice to convey specific meanings, as semiotic resources carry a variety of meaning potentials (cf. Nanni and Bellentani Citation2018, 381–382).

Two decades ago, Scollon and Scollon (Citation2003) coined the term “geosemiotics,” which refers to the importance of researching the semiotic aspects of space and place by scrutinising the social meaning of signs in the material world (Aiello Citation2021, 138). We have attempted something similar in this paper by drawing on a social semiotic approach to meaning-making and analysing both two- and three-dimensional representations of urban industrial heritage. We start by presenting our empirical case followed by a description of our methods. Thereafter, we carry out a social semiotic inspired reading of two visualisations of industrial heritage and analyse the so-called Peterson elephant(s) – one signboard and one sculpture. We then demonstrate that our reading of the latter differs from the intentions of the commissioner and the artist, before concluding the paper.

Case presentation

Peterson was a former cellulose factory in Moss, a midsized city in south-eastern Norway. It was established in 1883 and produced paper until it went bankrupt in 2012. On cold winter days, the factory covered the cityscape in white smoke. The oldest physical remains of industry stem from Moss’s ironworks, which operated on the Peterson premises before it became a place of cellulose production. Several structures have been demolished whilst others have been adapted and reused for new purposes. Höegh Property, the owner and developer of the premises, is in the process of constructing several new apartment blocks and their goal is to build a brand-new city district at the former industrial site. Once completed, this urban regeneration will lead to more than 2000 new homes, as well as businesses, offices, shops, restaurants, and various cultural and recreational services (Skrede and Andersen Citation2021; Swensen and Skrede Citation2018, 12).

One of the most peculiar remaining structures is the digester (), the main component in the process of making cellulose. The digester was installed in 1971, and it stands out in the cityscape due to its height of almost 70 metres. The digester is famous for the smell it produced while “boiling” chemical pulp; a smell so famous that the expression “the smell of Moss” is known all over Norway. However, the fate of the digester has come into question because Höegh Property does not know what to do with it. Preservation procedures need to occur for it to remain standing, but the developer is not willing to carry the cost alone. Höegh Property has said that they are willing to pay a “fair share” for the digester’s preservation if other actors, such as the municipality, residents’ associations, benefactors, or sponsors, would do the same. Thus far, this strategy has been unsuccessful, and the digester’s fate remains uncertain (Skrede and Andersen Citation2021).

At present, we do not know whether the digested will be preserved, adaptively reused, dismantled, and/or recycled. The outcome of large-scale transformations of urban landscapes involving planners, policymakers, private developers, heritage workers, engaged residents, and the media can most likely be accurately determined only in retrospect (also Andersen, Ander, and Skrede Citation2020). However, this does not mean that the digester has not already been represented, reimagined, and resemiotised for different purposes. The same is true for the (locally) famous Peterson elephant logo. After the factory closed, the logo is still used to market different cultural activities in the city, and the elephant is a cherished symbol for many citizens of Moss (Holsvik Citation2019). We will return to the digester and the elephant logo after outlining our research strategies.

Methods

We have been inspired by a social semiotic approach to analyse both two- and three-dimensional representations. Social semiotics is a theory of language and communication that is interested in the many available choices that sign producers can make between semiotic resources (Ledin and Machin Citation2020, 15). The aim is to explore different ideas, moods, attitudes, modalities, values, and identities that can be signified through these resources (Abousnnouga and Machin Citation2011, 178). In our upcoming case study, it is the visual that is prominent. Since no visual representation can fully represent a case, we may ask what and who have been omitted in terms of people, actions, settings, backgrounds, contexts, etc. (also Grubbauer Citation2014). Visualisations also typically add, foreground or subordinate elements, and we may ask how this affects the meaning potential (Skrede and Andersen Citation2020, 4; Abousnnouga and Machin Citation2011). We may also look for several “modality cues” (Hodge and Kress Citation1988, 128). Modality concerns the “perceived reality” of a representation. It is not about whether a given proposition (representation) is “true,” but rather whether it is represented as true (Ravelli and Van Leeuwen Citation2018, 277–288). Kress and van Leeuwen (Citation2006, 154–174) originally defined eight forms of modality in images, including contextualisation of backgrounds (on a scale ranging from fully articulated to the absence of a background) and seven other modality cues.Footnote1 However, it is important to emphasise that this approach is not a formalist one that will always produce the same “correct” reading. Meanings are not frozen and fixed things to be extracted and decoded by analysts. Social semiotics cannot assume that texts produce exactly the meanings and effects that their authors intended; rather, it is the struggle over these meanings that is studied (Hodge and Kress Citation1988, 12; Skrede and Andersen Citation2020, 4).

In addition to the social semiotic reading of two- and three-dimensional representations, one of the authors interviewed the artist behind the sculpture “The elephant and Moss” to learn more about the process of commissioning and producing artworks. He also interviewed a focus group made up of three locals to examine how they interpreted the ongoing urban regeneration project at the former industrial premises.

Heritage as representation

Language is a resource that can be exchanged for other symbolic or material resources (cf. Bourdieu Citation1986; Järlehed Citation2021, 6) and vice versa. Heritage, for example, is not only about objects; it is also about visual, textual, and other forms of representation. One of our interviewees argued that the politicians and property developers are now trying to “brand” Moss in new ways, and they found this to be neglectful of what Moss is or has been. We will return to this after providing some examples of how heritage is visualised in different ways for different purposes.

Envisioning the future

The local heritage management office in Moss commissioned a visualisation to demonstrate the potential of reusing the digester. It is a somewhat ghostlike urban scenery with dark clouds just waiting to pour rain and evokes the paintings of Joseph M. W. Turner (). Several modality markers are “less than real” while others are “more than real” according to the naturalistic standard. People and cars, for example, are rather detailed while buildings and the landscape are less detailed. This is a choice of semiotic resources that combines naturalistic and sensory coding orientations that may evoke both an intellectual and an emotional reading (Machin Citation2007, 48–57; Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006, 160–163). The background is decontextualised and there are no details that specify the location, although we know that it is Moss due to the presence of the digester. Dependent on the viewer, we may say that the landscape indicates something other-worldly, almost a Gotham City-like urban scenery that is not part of our present. The particular use of semiotic resources may be read as an illustration of an adventurous cityscape from the future. The digester is given an ochre colour that blends into the cityscape, which is quite different from its chrome-like appearance in real life. The street is rather darkly lit, a modality trait that directs attention toward the digester. A grey shadow is added to the cylindrical form to blend it into the colour palette of the adjacent buildings. If cities are to compete with each other for visitors, investors, and capital, they must achieve a “fine mixture of distinction and recognition” (Järlehed Citation2021, 2). This cityscape is made unique by the presence of the digester. The strategic use of heritage, which is achieved by choosing certain semiotic resources, makes the urban scenery distinguishable and evokes a sense of “hereness” as opposed to “sameness.” If we imagine removing the digester, the street would become more vernacular, more like other cityscapes. It is therefore evident that the digester adds to the landscape’s “value of difference” (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Citation1998, 152–153).

The viewer is placed rather low, a semiotic choice that is often metaphorically associated with power (Machin Citation2007, 113). This angle gives the digester a salient position. The scene would probably evoke different feelings if, for example, the viewer instead looked down at the digester from one of the adjacent high-rise buildings. Furthermore, the diagonal main street, the cars and the snapshots of people both with and without bicycles work as “vectors” indicating action and movement (see also Zieba Citation2020, 14). This is not a static representation of a cityscape; it is a place where people are interacting both socially and professionally. Yet, there are no one dining at outdoor restaurants or people walking with prams. We may assume that their inclusion could have distorted the somewhat dramatic and adventurous atmosphere, as this is not a real cityscape (see also Grubbauer Citation2014, 347), but a visualisation of how it could be.

Through the window on the fourth floor of the building on the right, we see a woman and a man communicating. A similar scene is taking place on the roof balcony of the grey three-story building to the left. This may indicate that communication, not cellulose production, is the new economy. Depicting people communicating face-to-face is also a generic representation that can typically be found by searching for “conversation” or “communication” on international image banks like Getty Images. This visualisation may be read as a confirmation of western economies becoming more centred around thoughts and ideas, rather than producing paper.

An entrance of an apartment building

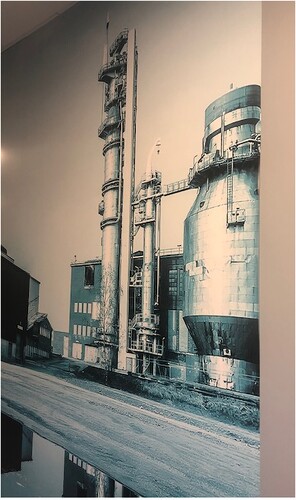

As noted, the former industrial premises will, when completed, contain several apartment buildings in addition to different businesses and social and cultural facilities. At the entrance of one of the first finished structures is a large, processed photograph of the digester on a wall across from the staircase (). Here, two adjacent structures are added to the right of the digester, “Fimpen” and “Massetårnet.” Both were also used in the process of making cellulose but were demolished prior to the creation of the visualisation. Despite this, the sign producer chose to include them. We may assume that the “artistic” quality could have been reduced without the presence of these structures. Additionally, the colour saturation is decreased and made “less than real.” This modality cue may evoke something romantic, eternal, or timeless (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006). The background is decontextualised. Although we understand that this is the former industrial site in Moss, the representation evokes a sense of general industrial structures. The level of detail is lower than the naturalistic standard, and the reflection of sunlight creates a somewhat mystic impression. Although the picture is from the factory’s operating years, there is no sign of actual production – no lorries, no workers with signal-coloured helmets, no emission of industrial toxic waste from the cellulose production, and no indication of indigence. The illustration somewhat recalls Berger’s (Citation2020, 1) remark about “silencing” labour. The steel structure, still standing on the premises just outside the entrance hall, is “resemiotisised” into a timeless two-dimensional artwork recalling middle-class consumption and the aesthetical “habitus” of the residents (cf. Bourdieu Citation1984). References to working-class life are subordinated and made implicit. The visualisation may be read as an example of the “aestheticization of industrial heritage” (Uhl Citation2021, 7), as well as a display of altered power relations that occur in many post-industrial societies (Datta and Odendaal Citation2019; McDonogh Citation2011).

Contextualising the social semiotic reading

Skyscrapers are “the iconography of the city” whether as singular buildings, like the Empire State Building, or as structural urban ensembles like the Manhattan skyline (Specht Citation2013, 51). Though it has a similar iconic elongated shape, we may wonder if the digester, as an instance of working-class heritage, is simply not “beautiful” enough to be preserved as an object (see e.g. Smith Citation2020b). Generally, we can distinguish between the factual status of a city and its imaginary or representational status. In terms of city branding, particular attention is often given to cities’ imaginary status (Klein and Rumpfhuber Citation2013, 79). The digester, in a resemiotisised shape, is correspondingly used to brand the new city district. However, resemiotisation is not just a concept meant to trace how semiotics translate from one mode to another. It is just as important to ask why these semiotic modes are mobilised to do certain things at certain times (Iedema Citation2000, Citation2003). In the case of Moss, it is evident that the digester is being used to attract potential buyers and investors with the value of being on historic ground. Simultaneously, the visualisation subordinates and glosses over the (real) process that will eventually decide the digester’s fate.

As mentioned, a visualisation cannot include everything, making it relevant to ask what has been foregrounded, subordinated, added, or removed. Fairclough (Citation2003) has demonstrated how we can do this with reference to texts, and we shall briefly discuss one example before relating it to Moss:

Finest grade cigar tobaccos from around the world are selected for Hamlet. Choice leaves, harvested by hand, are dried, fermented and carefully conditioned. Then the artistry of our blenders creates this unique mild, cool, smooth smoking cigar. (Fairclough Citation2003, 136)

It may seem somewhat peculiar that Höegh Property, similarly to Fairclough’s tobacco example, has chosen to remove all signs of production in the visualisation of the digester in the entrance hall. In the interdisciplinary scholarship in Heritage Studies, several scholars have claimed that labour-heritage has been “silenced” at the expense of other narratives (Berger Citation2020, 1; Smith Citation2020a, 128; Waterton and Smith Citation2010; Waterton, Smith, and Campbell Citation2006). However, it is important to stress that the social environment at Peterson from the 1970s onward was reported by former workers to be good, partly due to the presence of automation, meaning that there was less gruelling physical work (Grønna Citation2014; Holsvik Citation2015). Höegh Property has still chosen to visualise the digester without offering a sense of how a normal working day really was, with 24-hour operation in periods. As previously mentioned, epistemic modality is not about “truth” but rather about what is represented as real (Ravelli and Van Leeuwen Citation2018, 187). Höegh Property has said that they would like to remove the digester but that they would be willing to split the bill if someone else also contributed economic resources toward the restoration and adaptive reuse of the industrial structure. Thus, the value of the physical object is perhaps less than the value of its visual representation, as the symbolic value of living on historic ground may be imparted semiotically without preserving the three-dimensional physical object. However, several previous workers stated that they need something to “attach” their memories to, meaning that they want to preserve the digester as a material structure in order to more easily memorialise their time at the “Cellulose,” as the workers often called the factory (Skrede and Andersen Citation2021).

The Peterson elephant(s)

Aiello (Citation2021) referred to the concept of geosemiotics as developed by Scollon and Scollon (Citation2003), who argued that language is not the only focus in discursive and semiotic approaches to space and place by stressing the importance of the social meaning of the material placement of signs (Aiello Citation2021, 138). However, placement is not the only important factor; materials, shapes, sizes, angles, and so on also have meaning potentials, as they provide different affordances that may evoke different experiential associations (Abousnnouga and Machin Citation2013; Ledin and Machin Citation2020, 157–165). This is also true for the elephant(s) in Moss, which we will now turn to.

The “original” elephant

The digester is not the only important symbol for the people of Moss. The Peterson elephant used to sit atop of one of the industrial buildings, the upper part of which has since been demolished (). The original elephant was in the form of a neon-coloured logo. The elephant’s trunk, feet, and tail were shaped in a way that spelled out “Moss” and it held a log, alluding to the most important raw material for producing paper–wood. The design was also chosen to connote strength and cohesion among the employees, as the elephant is known for being a powerful animal with significant stamina (Grønna Citation2014).

In an interview conducted by one of the authors, the interviewees said that they found it sad that the elephant was just “thrown away in a corner.” It had, quite literally, lost its elevated status. The elephant is no longer visible in the landscape like it was when it was installed on top of the former industrial building (). This comment may be interpreted as a reaction to the “downgrading” of the elephant’s previous symbolic status. Apparently, the developer has treated the elephant logo as no longer deserving of being prominently displayed. It has instead become an “anomaly” or a “matter out of place” (cf. Douglas Citation2005; Campkin Citation2013). However, a former operator at Peterson suggested that the elephant ought to be mounted at the top of the digester, thereby restoring its elevated position. In that way, it could be a visible symbol of the industrial past (Grønna Citation2020). Anyone visiting Moss could then see where the famous “smell of Moss” came from. “Up” will often (but not always) be better than “down.” During the interview, the interviewees said that they found the placement of the elephant logo to be “careless” and “disrespectful.” This illustrates that vertical relations are “real” in terms of the associations they may carry.

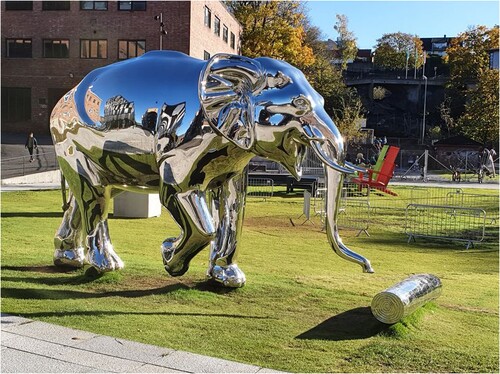

Parallel to the “symbolic downgrading” of the original elephant logo, Höegh Property, in collaboration with the “Trust for the Behoof of Moss,” commissioned a new elephant; a three-dimensional sculpture entitled “The elephant and Moss” (). It is made of acid-resistant blank and shiny steel and is about the size of a real elephant. It is placed behind a preserved administration building at Peterson on a greenfield next to a kindergarten called “The elephant.” What follows is our own social semiotic analysis of the elephant, and then an examination of the commissioners’ and artist's intention for the sculpture.

A social semiotic reading of the “steel” elephant

What meaning potentials are evoked by choosing different semiotic resources? The shiny steel elephant may connote a sense of something modern. Macdonald (Citation2021, n.p.) argues that steel has been described as a sign or expression of Modernity, partly because it is an essential component in modern products such as engines, radiators, and oil tanks. However, in Japan steel can also be used to “express traditional (…) sensibilities” (Kido, Cywinski, and Kawaguchi Citation2020, 63). This demonstrates that materials may have quite different meaning potentials (Abousnnouga and Machin Citation2013, 131). Employing signs does not guarantee that users will interpret them in the similar way, or as expected by the sign producer(s) (Nanni and Bellentani Citation2018, 382). This depends on the specific interpretative community in a specific social and cultural context. At a former industrial site such as Peterson; however, it is reasonable to assume that many will read steel as an expression of something modern.

Bright surfaces are capable of reflecting light and shine and brightness may be associated with positive feelings, in contrast to muted, darker shades, as reflected in the verbal metaphor: “I am feeling bright today” (Abousnnouga and Machin Citation2013, 51). We may ask how the meaning potential would have changed if the sign producer had chosen a different material. Shiny steel may be associated with something luxurious, scientific, and technological, but steel may also evoke a sense of something industrial and different from materials moulded and carved by hand, like marble (Abousnnouga and Machin Citation2013, 48). The fact that the sculpture was placed outside a kindergarten will probably contribute to frequent visits by children. We can imagine that they will find pleasure in examining themselves on the shiny surface, which creates an interpersonal relation.

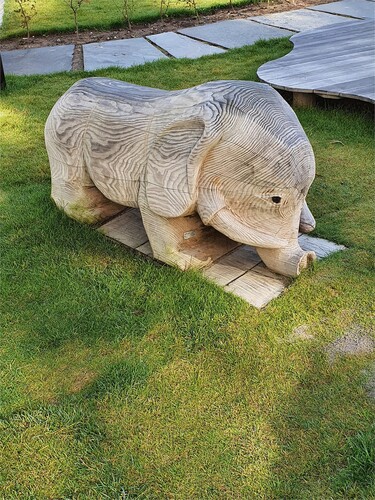

We previously examined how the digester was resemiotised from a three-dimensional object with some elements being removed whilst others are added. We can also see that this elephant sculpture no longer carries the wooden log with its trunk, as it did in the original Peterson logo. The elephant has put down the log, potentially symbolising that Peterson’s industrial period is a bygone chapter. The original elephant is resemiotised from a blue neon logo into a shiny elephant in blank steel. The main point of identifying resemiotisations goes beyond just describing how different modes are transformed and materialised in different ways. It is also important is to ask why something is resemiotised and what it means in terms of its altered meaning potentials (Iedema Citation2000, Citation2003). The elephant’s knee joint may be read as a “vector” indicating movement. It is almost as if the elephant is saying: “It is now time to move on.” Heritage is clearly important to Höegh Property, but visual representations thereof are just as important. The property developer maintained the use of the elephant as a brand, although it has not achieved the same elevated status as its predecessor did in the factory’s operating days. However, it is not only Höegh Property that uses the elephant as a brand and symbol of industrial history. At a playground not far from the steel elephant, it has been resemiotised into a small-scale elephant made of pine (). Its size means that it can be climbed and that children can sit on it; it has a different affordance than the steel elephant (Gibson Citation1986). However, although it can be assumed that the wooden elephant is popular among children, it would probably not brand Höegh Property in the same way that the shiny steel elephant does.

Nobody can anticipate exactly how a specific combination of semiotic resources will be interpreted. Every communicative event may also include implicit meaning, whether acknowledged or not, and we must consider the unintended consequences (and readings) of visual representations. We cannot expect that a social semiotic toolkit always will provide the same answers. In an interview, van Leeuwen explained that he received daily questions from both students and professors regarding the “correct” reading of a specific semiotic example. He said:

I wonder whether I created a monster. That happens when I get to see work of people who think that Reading Images is a kind of machine: you put images in and then something called analysis comes out of the other end. Or when people think that there is just one exactly right answer to every question. (…) That bothers me. (…). I try to explain that my ideas are just made by me, why I made them that way, and that they are not some kind of objective truth. (Andersen et al. Citation2015, 110, emphasis in original)

Hodge and Kress (Citation1988, 12) have offered a similar argument, indicating that traditional semiotics likes to assume that meaning(s) “were frozen and fixed in the text itself, to be extracted and decoded by the analyst by reference to a coding system that is impersonal and neutral.” This is not in accordance with a social semiotic approach to meaning-making. It is therefore interesting to talk to the sign producers to gain additional knowledge whether the object in question is a text, an image, or an elephant made of shiny steel.

An interview with the artist

Commissioning an artwork that will be placed in a public space can be intricate and time-consuming; many voices are normally involved in the decision-making (Abousnnouga and Machin Citation2011, 192–193; Citation2013, 77–100). This was different in Moss because the sculpture is on private property and was financed by private capital. No competition took place beforehand, and the commission was given directly to the artist. In an interview with the artist on 17 March 2021, one of the authors asked if she could explain the process that led to the sculpture a bit. She stated that the commissioners wanted a “magnificent specimen” of an elephant in shiny steel. Initially, Höegh Property wanted something that was built on the original elephant, but the sculpture took a rounder shape throughout the process. They said that they still wanted the elephant to hold the log with its trunk; however, it soon became evident that this could be difficult for technical reasons. It could cause situations where people climbed on the log and onto the top of the sculpture, leading to risks of falling. It was eventually decided that the log should not be carried by the trunk and should instead be integrated into the sculpture in another way. After trying various placements, the artist suggested laying the log on the ground in front of the elephant. She told the commissioners that this could evoke a metaphor of a closed industrial chapter and they decided that this was a good solution.

In our analysis, we suggested that it was probably Höegh Property that decided that the elephant should lay down the log, which was incorrect. In fact, it was a combination of technical and security reasons that led to the decision, and it was the artist that suggested laying the log in front of the elephant, not the commissioners. She saw, as we did, that this could evoke a post-industrial symbolism that could confirm that the old industrial era is a bygone as we look forward toward new and exciting possibilities. This demonstrates that contextualising a social semiotic reading may bring along new and interesting knowledge. Additionally, one of the authors indicated his belief that the placement of the elephant next to the kindergarten made it popular among children. The artist could not comment on that because she had not observed the usage of the sculpture in everyday life. However, she had seen children looking at themselves and interacting with the sculpture Seed, which is placed outside a school in Oslo and is made of the same shiny steel (). The artist also explained that the placement of the elephant was somewhat incidental. Initially, the idea was that it should be placed at another location on the industrial premises, but it finally ended up next to the kindergarten due to various considerations. Thus, the placement was not an act to entice children and their parents to view the commissioners as benefactors. The elephant ended up where it is today simply by chance.

In our social semiotic reading, we implied that blank steel may be viewed as modern and positive while shiny steel may be associated with something technological and luxurious, different from a material moulded by hand, like a sculpture made of marble (Abousnnouga and Machin Citation2013, 48). The artist shared these associations, saying: “Marble provides an ‘antique’ feeling.” She added that the material is “warm” and easy to work with while steel is “cold.” Yet, she said that the main reason for choosing steel was not symbolic but rather pragmatic: “Steel is almost maintenance-free, and scratches are hardly visible. The material lasts almost forever, and it is easy to maintain.” This demonstrates that a solely symbolic interpretation of the material may miss the fact that the commissioner may have considered pragmatic and economic elements as well.

The artist also explained that creating sculptures like the elephant in Moss demands a lot of handcrafting. Masters like Michelangelo and Bernini were not the only ones to mould their sculptures in laborious and time-consuming ways. The elephant in Moss was first given shape through clay and fibreglass models. Thereafter, the production team made a puzzle of small pieces of steel that were welded together before the sculpture was polished. Joints become invisible, which contributes to the sculpture’s industrial feeling. The artist said that the artisanal dimension is just as present in this type of sculpture as in marble, which is easier to work with. Here, we are witnessing an inversion of the example of the tobacco farmers. The tobacco producers wanted to evoke a sense of handcrafting, and this impression may have been weakened by rendering visible the industrial and impersonal conditions of production (Abousnnouga and Machin Citation2013, 26; Fairclough Citation2003, 137). The opposite is true in the case of the new Peterson elephant; the laborious and time-consuming work is kept secret from the audience to evoke a sense of technology and modern progress. This demonstrates that the idea is not always to display manual labour, even if craftsmanship is a vital part of the work. This depends on the experimental associations that the sign producers may want to induce.

Concluding discussion

Thus far, Höegh Property has not succeeded in getting others to pay for a share of the digester’s preservation. This can be assumed to be due to the challenge of getting someone to invest in other people’s private property without gaining something. This would be unappealing to anyone but (well-off) philanthropists. However, this has not prevented the digester from being used semiotically in different ways, both in attempts to save it and for the purpose of selling apartments. The case of the digester demonstrates that heritage is a multifarious phenomenon that contains both tangible and intangible dimensions (Skrede and Andersen Citation2021; Skrede and Hølleland Citation2018). The digester exists as an object and is visualised for different purposes, most pertinently to “brand” the new urban district (cf. Grubbauer Citation2014, 349).

The elephant is also used to brand Höegh Property. In our analysis, we implied that it was the commissioners that wanted the log to be laid in front of the elephant. After speaking to the artist, we found this interpretation to be wrong. This demonstrates that a contextualisation of a social semiotic reading may bring forth new and interesting knowledge; however, does that mean that an analysis without a conversation with sign producers loses its value? An artwork, whether it is a painting, a novel, a piece of music, or a sculpture shaped like an elephant, exists independently of any social semiotic reading thereof. In the classical essay The Death of the Author, Barthes (Citation2008) argued that it is possible to read and interpret a written text without considering the author’s life, taste, or personal inclinations. This is analogous to the New Criticism literary movement, where literature is seen as a self-contained aesthetical object that can be read and analysed without contextualising it. This view has been criticised for being a somewhat naïve conception of an “innocent” reader and an “autonomous” work, since a text is always read in the light of other texts (Bourdieu Citation1994, 113; Culler Citation1981, 13). An artwork can be interpreted without knowing anything about the intentions of the sign producer; however, talking to the creator may bring forth new and interesting knowledge about what he or she intended. Uncovering a gap between artists’ or commissioners’ intentions and users’ interpretations (cf. Nanni and Bellentani Citation2018, 383) – the latter group here includes the authors of this paper – demonstrates the fruitfulness of talking to the artist(s). Heritage is often used strategically for different purposes; however, our case study has demonstrated that the shape and placement of an object, for example, a sculpture of an elephant, might also be (partly) pragmatic and by chance. At the very least, awareness of this topic can help us avoid ascribing objectives to people or companies, which was demonstrated by our interview with the artist behind the “steel” elephant.

Future directions

In a previous study of “spectacular architecture” in the Norwegian capital by Andersen and Røe (Citation2017), they interviewed the architects about their role and strategies, but they did not discuss the working conditions of the workers constructing the high-rise buildings in question. Correspondingly, in this paper, we have talked to the artist behind the elephant but did not talk to the craftspeople involved in producing the sculpture. This could have provided valuable knowledge of the social, cultural, physical, political, and economic conditions of urban artworks that may add to the semiotic analysis.

Furthermore, in this paper, we prioritised to study the Moss case in (some) depth as we did not have empirical data or funding to do comparison; however, we see a potential in comparing Moss with similar cases in Norway, Europe, or elsewhere in future projects. Comparative analyses of other uses of symbols for the creation of urban landmarks could have strengthened our arguments and provided interesting knowledge of the semiotics of industrial heritage in both different and similar contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joar Skrede

Joar Skrede (PhD) is a Sociologist and Research Professor at the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research. His research interests include multimodal critical discourse studies, heritage studies, and urban studies.

Bengt Andersen

Bengt Andersen (PhD) is an Urban Anthropologist and Research Professor at the Oslo Metropolitan University. His research interests include urban studies and neighbourhood research.

Notes

1 The other seven modality cues are colour saturation; colour differentiation; colour modulation; representation of detail; depth; illumination; brightness (cf. Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2021, 160–162).

References

- Abousnnouga, Gill, and David Machin. 2011. “The Changing Spaces of War Commemoration: A Multimodal Analysis of the Discourses of British Monuments.” Social Semiotics 21 (2): 175–196.

- Abousnnouga, Gill, and David Machin. 2013. The Language of War Monuments, Bloomsbury Advances in Semiotics. Huntingdon: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Aiello, Giorgia. 2021. “Communicating the “World-Class” City: A Visual-Material Approach.” Social Semiotics 31 (1): 136–154. doi:10.1080/10350330.2020.1810551.

- Andersen, Bengt, Hannah Eline Ander, and Joar Skrede. 2020. “The Directors of Urban Transformation: The Case of Oslo.” Local Economy 35 (7): 695–713. doi:10.1177/0269094220988714.

- Andersen, Thomas Hestbæk, Morten Boeriis, Eva Maagerø, and Elise Seip Tønnesen. 2015. Social Semiotics. Key Figures, New Directions. London: Routledge.

- Andersen, Bengt, and Per Gunnar Røe. 2017. “The Social Context and Politics of Large Scale Urban Architecture: Investigating the Design of Barcode, Oslo.” European Urban and Regional Studies 24 (3): 304–317. doi:10.1177/0969776416643751.

- Barthes, Roland. 2008. The Death of the Author, 97–100. Malden: Blackwell.

- Berger, Stefan. 2020. “Introduction. Preconditions for the Making of an Industrial Past. Comparative Perspectives.” In Constructing Industrial Pasts. Heritage, Historical Culture and Identity in Regions Undergoing Structural Economic Transformation, edited by Stefan Berger, 1–26. New York: Berghahn.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handboook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by John G. Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1994. Symbolsk Makt. Oslo: Pax Forlag A/S.

- Campkin, Ben. 2013. “Placing ‘Matter Out of Place’: Purity and Danger as Evidence for Architecture and Urbanism.” Architectural Theory Review 18 (1): 46–61. doi:10.1080/13264826.2013.785579.

- Casey, Edward S. 1997. The Fate of Place: A Philosophical History, A Centennial Book. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Culler, Jonathan. 1981. The Pursuit of Signs. London: Routledge.

- Datta, Ayona, and Nancy Odendaal. 2019. “Smart Cities and the Banality of Power.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (3): 387–392. doi:10.1177/0263775819841765.

- Douglas, Mary. 2005. Purity and Danger. An Analysis of Concept of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge.

- Duncan, James S., and Nancy G. Duncan. 2004. “Culture Unbound.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 36 (3): 391–403. doi:10.1068/a3654.

- Edensor, Tim. 2005. Industrial Ruins. Spaces, Aesthetics, Materiality. New York: Berg Publishers.

- Fairclough, Norman. 2003. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. London: Routledge.

- Feld, Steven, and Keith H. Basso, eds. 1996. Senses of Place, School of American Research Advanced Seminar Series. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

- Gibson, J. J. 1986. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. New York: Psychological Press.

- Grønna, Bjørn A. 2014. Et Arbeidsliv på Cellulosen. Prosjekt Arbeidsarven, Moss. Rælingen: Flisby'n Forlag.

- Grønna, Bjørn A. 2020. “Symboler og signalbygg på Verket: La kokeren stå og få elefantlogoen opp på toppen.” Moss Avis. https://www.moss-avis.no/symboler-og-signalbygg-pa-verket-la-kokeren-sta-og-fa-elefantlogoen-opp-pa-toppen/o/5-67-1168641.

- Grubbauer, Monika. 2014. “Architecture, Economic Imaginaries and Urban Politics: The Office Tower as Socially Classifying Device.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38 (1): 336–359. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12110.

- Hodge, Bob, and Gunther Kress. 1988. Social Semiotics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Holsvik, Bjørg. 2015. “Den fleksible operatør. Omstilling, opplæring og fleksibilitet ved Peterson Moss 1990–2006.” Arbeiderhistorie 29: 113–134.

- Holsvik, Bjørg. 2019. “Elefanten fra Moss [The Elephant from Moss].” https://digitaltmuseum.no/021188199308/elefanten-fra-moss.

- Iedema, Rick. 2000. “Bureaucratic Planning and Resemiotisation.” In Discourse and Community. Doing Funcional Linguistics, edited by Eija Ventola, 47–69. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag Tübingen.

- Iedema, Rick. 2003. “Multimodality, Resemiotization: Extending the Analysis of Discourse as Multi-Semiotic Practice.” Visual Communication 2 (1): 29–57.

- Järlehed, Johan. 2021. “Alphabet City: Orthographic Differentiation and Branding in Late Capitalist Cities.” Social Semiotics 31 (1): 14–35. doi:10.1080/10350330.2020.1810547.

- Kido, Ewa Maria, Zbigniew Cywinski, and Hidetoshi Kawaguchi. 2020. “Tradition and Modernity in the Structural Art of Steel-Glass Structures in Japan.” Steel Construction. Design and Research 14 (1): 55–63. doi:10.1002/stco.202000025.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. 1998. Destination Culture. Tourism, Museums, and Heritage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Klein, Michael, and Andreas Rumpfhuber. 2013. “The Possibility of a Social Imaginary: Public Housing as a Tool for City Branding.” In Branded Spaces. Experiences Enactments and Entanglements, edited by Stephan Sonnenburg and Laura Baker, 75–85. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. 2021. Reading Images. The Grammar of Visual Design. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Krzyżanowska, Natalia. 2016. “The Discourse of Counter-monuments: Semiotics of Material Commemoration in Contemporary Urban Spaces.” Social Semiotics 26 (5): 465–485. doi:10.1080/10350330.2015.1096132.

- Ledin, Per, and David Machin. 2020. Introduction to Multimodal Analysis. 2nd ed. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Macdonald, Angus. 2021. Steel Architecture: The Designed Landscape of Modernity. e-book ed. Marlborough: The Crowood Press.

- Machin, David. 2007. Introduction to Multimodal Analysis. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- McDonogh, Gary W. 2011. “Learning from Barcelona: Discourse, Power and Praxis in the Sustainable City.” City & Society 23 (2): 135–153. doi:10.1111/j.1548-744X.2011.01059.x.

- Nanni, Antonio, and Federico Bellentani. 2018. “The Meaning Making of the Built Environment in the Fascist City: A Semiotic Approach.” Signs and Society 6 (2): 379–411.

- Ravelli, Louise J, and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2018. “Modality in the Digital age.” Visual Communication 17 (3): 277–297. doi:10.1177/1470357218764436.

- Scollon, Ron, and Suzie Wong Scollon. 2003. Discourses in Place. Language in the Material World. London: Routledge.

- Skrede, Joar, and Bengt Andersen. 2019. “A Suburban Dreamscape Outshining Urbanism: The Case of Housing Advertisements.” Space and Culture, 1–13. doi:10.1177/1206331219850443.

- Skrede, Joar, and Bengt Andersen. 2020. “Selling Homes: The Polysemy of Visual Marketing.” Social Semiotics, 1–19. doi:10.1080/10350330.2020.1767398.

- Skrede, Joar, and Bengt Andersen. 2021. “Remembering and Reconfiguring Industrial Heritage: The Case of the Digester in Moss, Norway.” Landscape Research 46 (3): 403–416. doi:10.1080/01426397.2020.1864820.

- Skrede, Joar, and Herdis Hølleland. 2018. “Uses of Heritage and Beyond: Heritage Studies Viewed Through the Lens of Critical Discourse Analysis and Critical Realism.” Journal of Social Archaeology 18 (1): 77–96. doi:10.1177/1469605317749290.

- Smith, Laurajane. 2020a. Emotional Heritage: Visitor Engagement at Museums and Heritage Sites. London: Routledge.

- Smith, Laurajane. 2020b. “Industrial Heritage and the Remaking of Class Identity. Are We All Middle Class Now?” In Constructing Industrial Pasts. Heritage, Historical Culture and Identity in Regions Undergoing Structural Economic Transformation, edited by Stefan Berger, 128–145. New York: Berghahn.

- Specht, Jan. 2013. “Architecture and the Destination Image: Something Familiar, Something New, Something Virtual, Something True.” In Branded Spaces. Experiences Enactments and Entanglements, edited by Stephan Sonnenburg and Laura Baker, 43–73. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Swensen, Grete, and Joar Skrede. 2018. “Industrial Heritage as a Culturally Sustainable Option in Urban Transformation. The Case of Skien and Moss.” Form Academic 11 (6): 1–22.

- Uhl, Magali. 2021. “Marshland Revival: A Narrative Rephotography Essay on the False Creek Flats Neighbourhood in Vancouver.” Visual Studies, 1–22. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2021.1876527.

- Waterton, Emma. 2010. “Branding the Past: The Visual Imagery of England's Heritage.” In Culture, Heritage and Representation. Perspectives on Visuality and the Past, edited by Emma Wateron and Steve Watson, 155–172. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Waterton, Emma, and Laurajane Smith. 2010. “The Recognition and Misrecognition of Community Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 4–15. doi:10.1080/13527250903441671.

- Waterton, Emma, Laurajane Smith, and Gary Campbell. 2006. “The Utility of Discourse Analysis to Heritage Studies: The Burra Charter and Social Inclusion.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 12 (4): 339–355. doi:10.1080/13527250600727000.

- Waterton, Emma, and Steve Watson. 2014. The Semiotics of Heritage Tourism, Tourism and Cultural Change. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

- Zieba, Anna. 2020. “Visual Representation of Happiness: A Sociosemiotic Perspective on Stock Photography.” Social Semiotics, 1–21. doi:10.1080/10350330.2020.1788824.