ABSTRACT

This paper discusses the dialectics of urban place and its public image, approached via an examination of the public process of proposing, debating, and selecting new monuments for the city of Gothenburg, Sweden. The analysis shows that while the proposed monument to the local foodstuff halv special (a type of hot dog) is generally received in a positive way, the proposal of a monument to falafel is met with criticism. The results suggest that the two artworks represent different classed, gendered, and racialized imaginations of the city and its residents: while the hotdog reproduces a long-standing and dominant Social Democrat understanding of Gothenburg as the home of the white male worker, the falafel suggests an updated and more inclusive idea of the city as multilingual and multicultural.

Introduction

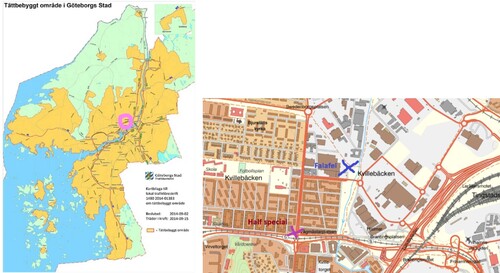

Every three years since 1909, the Charles Felix Lindberg Foundation has financed public art in Gothenburg, Sweden. Each time, citizens are invited to suggest ideas to the politicians at the City Council, who then make the formal nomination. In 2021, two ideas stood out: both were based on what was perceived as local and localizing food, and they generated considerable media commentary and public debate. On the one hand, the Social Democrat Jesper Hallén proposed a halv special (“half special”)Footnote1, a hotdog with mashed potatoes, to be placed at Vågmästarplatsen, a square in the recently gentrified Kvillebäcken neighbourhood (). On the other hand, the cultural association Göthenburgo, which is running integration projects throughout the city, proposed a statue of a man holding a falafel to be placed near Backaplan, a mall area in the same neighbourhood (). While referring to the same neighbourhood, the two proposals highlighted different aspects of its history. The first proposal related to the 1940s, when, according to local hearsay, the first halv special was served in the area by Albert Johansson (Drakenfors Citation2000). Kvillebäcken was then solidly working-class, and Sweden and Gothenburg hosted a homogeneous white population. By contrast, the second proposal referred to the beginning of the twenty-first century, a time when Gothenburg and Sweden had become increasingly diverse. It was made in honour of Nazih Elsheikali, who had run the popular falafel stand Alibaba for 20 years, until the business was closed in 2019 due to the state-led redevelopment and gentrification of Kvillebäcken (Thörn and Holgersson Citation2016).

Figure 1. Left, a map of the municipality of Gothenburg, with the island of Hisingen to the north and the neighbourhood of Kvillebäcken marked in pink. Right, a map of Kvillebäcken is marked with the intended locations of the two monuments.

These temporal differences notwithstanding, both monuments were intended for the southern banks of the stigmatized island of Hisingen. In the last decades, Gothenburg has suffered from increasing inequality and segregation (Andersson, Bråmå, and Hogdal Citation2010; Göteborgs stad Citation2017), and one of the political means to counter this process has been to make Hisingen a natural part of the “inner city”, i.e. the wealthy and white centre of power, among other things by doing away with the public image of Hisingen as “an industrial and working-class area”Footnote2 (Despotović and Thörn Citation2015, 237). The new image is intended to be appealing to “the middle class’ taste and preferences”, since they are “expected to create attractiveness and urbanity” (Despotović and Thörn Citation2015, 238).

While the halv special was supported by Social Democrats at the City Council, the falafel received support from Socialist, Green, and Liberal politicians. However, in August 2021, both proposals were turned down. The City Council decided instead to support the Cultural Committee’s suggestion to finance a monument to Swedish women’s football, and an art installation for a former military camp now being rebranded as “a cultural meeting point” (Kulturnämnden Göteborgs Stad Citation2021).

Against this background, this paper examines the role of public art in relation to urban and social change. I approach the overall theme of this special issue, i.e. street art, not as it is conventionally understood, but as art on the street. Furthermore, the focus is not so much on the emplacement of the art on the street as on its impact on and interaction with public space and the people who inhabit it. Unlike previous research, which looks at urban and social change once the artworks are in place (e.g. Cameron and Coaffee Citation2005; Hall and Robertson Citation2001), I will focus on the social meanings that are ascribed to these two food-based artworks and discursively associated personae and places in medias res. More specifically, the paper is informed by the following research questions: What indexicalities of place and persona are constructed through this process of mediatized enregisterment? And how is it constrained by and contributing to the reproduction of existing and emerging power relations in Gothenburg? By enregisterment, I refer to the semiotic process by which distinct forms of speech and other semiotic resources are recognized as representing and indexing social groups, categories, and places (Agha Citation2005; Johnstone Citation2006). And by mediatized enregisterment, I refer to the ways in which the process of enregisterment is materialized, circulated, and negotiated in different forms of media (Androutsopoulos Citation2014, Milani, this issue).

More generally, the paper considers the current and ongoing negotiation of the public image of Sweden, of which Gothenburg and Hisingen are part, on the one hand, and the access for distinct constituencies of citizens to the public sphere, on the other. Steady migration from non-European countries over the last four decades has increased the ethnic, religious, cultural, and linguistic diversity of the country and city. Simultaneously, cutbacks in the welfare system have hardened the competition between different constituencies of citizens, often along new racial, ethnic, and religious lines of division, as well as longstanding class and gender inequalities (Hübinette and Lundström Citation2014; Pred Citation2000). Hence, Gothenburg and Sweden are in a state of transition, and different stakeholders are engaging in a struggle around what is to (be)come, and who is going to be part of it (see Kramer this issue for a discussion of graffiti, stakeholders and struggles in New York City).

By analysing a set of media texts emerging around the two proposals and building on earlier research on urban change in Gothenburg (Holgersson et al. Citation2010; Despotović and Thörn Citation2015; Franzén, Hertting, and Thörn Citation2016; Thörn and Holgersson Citation2016) and the social semiotics of monuments and counter-monuments (Krzyżanowska Citation2016), the paper suggests that the two monuments represent different imaginations of the city and its residents. While the hotdog image reproduces the status quo and a long-standing and dominant Social Democrat understanding of Gothenburg as the home of the white male worker, the falafel suggests an updated and more inclusive idea of the city as multilingual and multicultural.

Setting the scene: fast-food, Gothenburg, and the Charles Felix Lindberg Foundation public art program

While the word falafel (from Arabic falāfil “pepper”) has been attested in Swedish since 1959 and is included in the Swedish Academy’s dictionaries (Svenska Akademien Citation2021), halv special, which dates to the 1940s, has never been included. It was however incorporated into Andersson’s (Citation2021) recent lexicon of Gothenburgish. This signals the enregisterment and social recognition of halv special as a Gothenburg-specific dish and expression, while the term and dish falafel are recognized at a national and international level. Yet, beyond this dictionary testimony, the data examined in this paper suggest that halv special and falafel provoke different, ideologically based feelings, readings, and debate. The fast-food stand thus emerges as a site and symbol of how processes of and political struggles over migration and integration play out in Sweden.

The proposal for a monument to the halv special is based on the local and amply mediatized hearsay that situates the dish’s origin at Vågmästarplatsen (Drakenfors Citation2000; Kulturnämnden Göteborgs Stad Citation2021). For two generations from the 1930s, father and son Johansson sold hot dogs from a stand in the area, until the 1990s when it was taken over by two Swedish-Turkish brothers who began selling kebab and falafel, together with hot dogs and burgers (Drakenfors Citation2000). Nowadays, the typical Swedish fast-food stand sells both older foodstuffs, that are still seen by some as being “more Swedish”, and newer dishes, which some consider “less Swedish”, “foreign”, or “ethnic”, reflecting the ethnic and cultural diversity of the country ().

Figure 2. A typical fast-food stand in modern Gothenburg, Sweden, selling both hot dogs and burgers, and falafel and kebab. Photo by the author, January 2022.

The public image of Gothenburg has changed over time. In the nineteenth century and the first half of the 20th, the city established itself as a working class and industrial port city. In the 1970s, the city entered a period of economic recession and demographic stagnation, perhaps most visible in the closing of the shipyards and the abandonment of the central riverbanks. However, like in other post-industrial Scandinavian and European port cities, the centrally located riverbanks soon became subject to processes of urban “renewal” and “regeneration”, driven by the economic interests of the middle class (Holgersson et al. Citation2010; Thörn and Holgersson Citation2016).

The political handling of the post-industrial crisis of the 1970s-1990s is reflected in the city’s marketing films, where the image has gone from that of a friendly working-class city to an entrepreneurial “city of events” for the creative classes (Florin Persson Citation2021). Thus, the solid enregisterment of the city and its residents as working-class is today being renegotiated (see Snadjr and Trinch this issue for a discussion of gentrifying neighborhoods in Brooklyn). This process of reimagining and rebranding is driven by the urban entrepreneurial mode of governance that currently characterizes the city (Franzén, Hertting, and Thörn Citation2016). A central component of the urban entrepreneurial discourse is the celebration of “diverse and living” neighbourhoods (Järlehed et al. Citation2021). Despite this, there is in Gothenburg “a normative centre associated with ‘Swedishness’” that often resonates in “the official Gothenburg’s ambivalent relation to immigrants” (Holgersson et al. Citation2010, 16).

The ideological tensions that underpin the reimagining and reproduction of Gothenburg’s public image are important to consider when analysing the city’s handling of the Charles Felix Lindberg Foundation (CFLF). Lindberg (1840-1909) was a Gothenburg businessman who bequeathed his fortune to the establishment of a foundation for “the adornment and beautification of the city”. The will exemplifies this with the construction of “parks and plantations” and the erection of “statues and other art works” (Lindberg Citation1909). I argue that the city administration’s handling of the CFLF resonates with a shift towards a more socioeconomically and politically motivated interpretation of the will’s aims. In 2017, the Swedish government adopted the bill Policy for Designed Living Environment, with the following objective: “Architecture and design will help to create a sustainable, equitable and less segregated society with carefully designed living environments in which everyone is well placed to influence the development of their shared environment” (Swedish Government Citation2017, 5). It is not mandatory for the Gothenburg City Council to follow these aims, but it is recommended.

This shift was clearly reflected in Gothenburg in 2018, when the City Council decided to let the CFLF finance three artworks that aimed at recognizing and commemorating silenced minorities, experiences, and histories (Göteborgs Stad Citation2020). Yet, as the analysis will show, even while there is a political will to use public art to address socio-political issues, there is no consensus on what and whose experiences, tastes, and histories to commemorate, and how. And this invites public debate.

Conceptual and methodological framework

As stated in the introduction, for the analysis in this paper, public art is a more important concept than street art. Public art is “an open and contested term” where the word “‘public’ can range in its designation from simply indicating artistic work that is placed ‘outdoors’ (i.e. not contained within a closed architectural structure) to pointing to the artistic work as the result of the actions of state agencies” (Caminha et al. Citation2018, 4–5). The art works discussed in this paper are public in both senses. Yet, since the proposed monuments have not been realized and the analysis centres on the mediatization and public debate, another relevant dimension of the concept public is its communicative and performative function:

“Public” is also a set of communication practices that take place through mediated, national and international media to give rise to what we perceive as public opinion. In this regard, what public does to art is to make it answerable to demands of taste and involvement in the democratic processes of city building, of which public art commissioning forms a part. (Bingham-Hall Citation2015, 3)

Indexicality is a key concept in processes of enregisterment, where it often operates in dialectically ordered systems (that evolve over time), with the enregistered form being variously recognizable and accessible to different social constituencies (Johnstone Citation2006, 81–84). This means that the capacity to use the form for social meaning making, categorization, and identity performances, is unevenly distributed among the population, and variously received by different audiences.

Hence, indexicality “is not only a process of signification, but also a social process that works to position actors within interactional and ideological frameworks in which some enjoy more access to resources than others” (Hughes and Tracy Citation2015, 5). This underlines the importance of developing a critical and contextualized account of the local structures and relations of power. For this reason, I use intersectionality (Nash Citation2008) as a theoretical and methodological tool for showing how different social categories (class, race, and gender) are cued in the mediatization of the two proposals, and how these categories contribute to the framing of them as a monument (the halv special) and a “counter-monument” (the falafel) (Krzyżanowska Citation2016), thus potentially sustaining or challenging local hegemony.

Since monuments typically commemorate events, people, and places that are embraced by mainstream society, they help in “sustaining the social and political status quo” (Krzyżanowska Citation2016, 468), and can thus be conceptualized “as forms of spatial hegemony” (Krzyżanowska Citation2016, 469). However, the last decades have also featured more counter-monuments, i.e. monuments that serve as “tools of questioning and critiquing – and not only sustaining and institutionalising – social order and the (allegedly) universal values at the core of the society” (Krzyżanowska Citation2016, 470).

The intersectional approach allows me to show how two apparently similar public art proposals trigger political and socioeconomic inequalities in different ways and degrees, and how this depends on the foodstuffs involved being perceived as indexing different social categories. Historically, intersectionality comes out of black feminism and has mainly been used for analysing marginalized and repressed subjectivities and categories. Yet, “all identities are always constituted by the intersections of multiple vectors of power” (Nash Citation2008, 10). I therefore suggest the comparison of monuments and counter-monuments as a methodological response to the theoretical challenge of intersectionality “in conceiving of privilege and oppression as complex, multi-valent, and simultaneous” (Nash Citation2008, 12).

The data

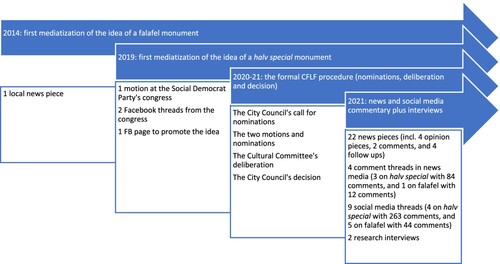

For the analysis I have been looking at a complex series of processes and texts, including, firstly, the early mediatization of the original ideas, the formal invitation to the city’s residents to propose ideas for the CFLF program for the adornment and beautification of Gothenburg and to the City Council’s members to nominate proposals to the Council, the Culture Committee’s evaluation and recommendation, and the City Council’s final decision; and secondly, the parallel news media covering and public commentary on some of these news pieces, as well as on social media. In addition to this, I interviewed the principal spokespersons behind the two proposals: Jesper Hallén (halv special) and Roozbeh Behtaji (falafel). gives a chronological overview of these processes and lists the number and types of texts that were analysed for each stage of the processes.

The media coverage was collected with Retriever Research, the comment threads on the news pieces through the newspapers’ online editions, and the social media threads, by using the search terms halv special-staty and falafelstaty on Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit.

Analysis

In this section, I first make an overall comparative description of key features in the two proposals and their public reception. I then move on to an analysis of the media coverage and audience commentary.

Overall comparative observations

The proposals

The idea to create a monument to the halv special was first presented to a broader audience at the Social Democrat Party’s district congress on 26 October 2019. Jesper Hallén formalized the idea in a motion that was signed by himself and three other party members (Socialdemokraterna Göteborg Citation2019, 51–52). The motion was constructed around four arguments:

local cultural heritage: the halv special is a Gothenburg “culinary” speciality

site history: Vågmästareplatsen is supposedly the place where the halv special was “invented” and served for the first time

current built and social environment: today the square is dominated by a new market hall which brings a lot of people there to enjoy food

cultural scarcity: there are few sculptures in this neighbourhood.

Although the party’s District Board recommended dismissing the proposal – with the threefold argument that (1) fast-food does not have enough “dignity” to qualify as art, (2) the halv special is not typical only of Gothenburg but of a number of West Swedish cities, and (3) there are already too many statues and monuments to men in GothenburgFootnote3 – the congress voted yes. Though shelved at the congress, the Board’s critical arguments resonate in many of the negative comments that were later posted on social media and in the comment fields of the news pieces.

In the spring of 2021, Hallén convinced six members of the Social Democrat Party and one from the Green Party to sign a motion to the City Council/CFLF to erect a monument to the halv special at Vågmästarplatsen. Three new arguments are added to the original ones from the motion at the party congress:

The hot dog serves as a symbol for “the everyday and folk character” of Gothenburgness.

It is time to celebrate the importance of fast-food in contemporary urban life.

Humour is highlighted as a salient feature of Gothenburgness.

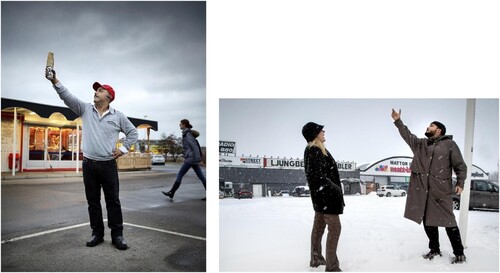

The idea of a monument to falafel first came from Nazih Elsheikali. In a long report on the history and position of kebab, falafel and shawarma in Gothenburg’s fast-food scene, he was cited, with a photo of himself in front of the Alibaba stand and proudly raising a falafel to the sky (): “When I am done here and retire, I will build a statue to myself with a falafel in my hand, and they will rename this place to Alibaba Square” (Askerup Citation2014). In their motion to the City Council in 2021, Göthenburgo includes the 2014 quote and the photo, and creates a narrative around inequality, gentrification, and displacement. Following a description of how Alibaba had to close because of the redevelopment of the area, they pose rhetorical questions about “who is allowed to stay when the city grows? Who can take their place in its streets and be included in the writing of the city’s history?” (Kulturnämnden Göteborgs Stad Citation2021). They argue that a monument to falafel would “express that the city belongs to us all, that we are all as much a part of Gothenburg no matter what our background in terms of class, ethnicity, or food culture” (Kulturnämnden Göteborgs Stad Citation2021).

Figure 5. The original photo of Nazih Elsheikali posing with the falafel (Askerup Citation2014, 9), and Roozbeh Behtaji imitating the pose (Moberg Citation2021). Reproduced with permission of the photographers, Stefan Edetoft and Per Wahlberg.

We see how the two proposals were based on distinct but related arguments. While both proposals included a celebration of local history and cultural heritage, they differed regarding what and who was to be included in this. Importantly, the temporal references of the two proposals differed. The halv special takes us back to the 1930s and 1940s, the heydays of Swedish Social Democratic governance, and the creation of the welfare society – emblematically termed The People’s Home. The falafel is firmly rooted in the period from the 1990s, when the kebab and falafel were established on the Swedish fast-food scene (Askerup Citation2014), until the 2010s, when the new Kvillebäcken was built, and Alibaba was displaced. For the analysis below, it is important to remember that while Sweden and Gothenburg in the first period were primarily divided along class and gender lines, the second period saw new lines of division emerging around categories of ethnicity/race, language, and religion (Hübinette and Lundström Citation2014).

Reader commentary

As illustrated in , the proposal for a monument to the halv special generated considerably more reader comments than the one to falafel. While most of the comments on the halv special were positive, most of the comments on the falafel were negative. Moreover, while the overall tone of the threads on the halv special was witty and light-hearted, the negative comments on falafel were dominated by sarcasm and hate. Though related, wit and sarcasm differ in the important sense that the latter is used to embarrass or insult someone: sarcasm often “work[s] more as social control on the recipient than to present a personality for the joker” (Norrick Citation2003, 1348).

Although these observations are rather basic, I maintain that they are crucial to interpreting the whole process: while the positive commentary on the halv special both indexes and facilitates the maintenance of the status quo, or at least serves in blocking social change, the negative comments on the monument to falafel show that it is rather perceived as a threat to the status quo. For this reading, I follow Krzyżanowska’s (Citation2016) account of the social semiotics of monuments and counter-monuments, and Gramsci’s theory of hegemony as building on and resulting in the majority’s acceptance of unequal relations of power.

As stated by Krzyżanowska (Citation2016, 471), “Counter-monuments […] re-enact discourses of memory that were rejected, omitted, or outright silenced by the (urban/local/national) collectivity and make a virtue of what would otherwise be deemed a difficult or inconvenient past”. With their proposal, Göthenburgo wanted to draw attention to a recent past that is perceived as troublesome to many, perhaps especially the property owners and city politicians, who were criticized in both academic and public debates that followed the displacement of many of the former tenants of the neighbourhood (Despotović and Thörn Citation2015; Thörn and Holgersson Citation2016).

From a scalar perspective, finally, the comments on the halv special are primarily concerned with the local imagination of Gothenburg and Hisingen, whereas the comments on falafel are instead oriented to a national level, circulating, debating, and reproducing ideas about Sweden and Swedishness. As will be illustrated in the next section, Gothenburgness is constructed by a set of semiotic resources which are almost exclusively represented in the texts about the halv special.

Uneven distribution of differentiating and enregistering resources

The data sample contains a set of resources that serve for social semiotic differentiation and the enregisterment of figures of personhood and placehood: wordplay, dialect, accent, wit, sarcasm, renaming, gendering, and racialization. They are unevenly distributed and activated in the commentary on the halv special and the falafel (). I maintain that this uneven distributional pattern of mediatization contributes to the enregisterment of the halv special as “Gothenburgish” (and hence distinct but not necessarily excluded from Swedishness) and white, and falafel as primarily non-Swedish and non-white.

Table 1. Distribution of differentiating and enregistering resources used in the commentary on the two proposals.

Dialect and accent

Whereas both dialect and accent serve in differentiation and distinction making, the first is here framed as positive and the second as negative. While a considerable amount of the commentary on halv special features the local dialect, götebosska, it is not at all present in the comments on the falafel. Instead, the negative comments on the falafel frame it as a marker of deviance, or “an accent of an accent” (Hodge and Kress Citation1988, 86). That is, the falafel is discursively constructed as standing for something other than Gothenburg, as a deviance from and threat to the perceived social and spatial order of the city. In this sense, it differs from the local dialect, which is enregistered as belonging to the place and serving as a marker of both place and persona. In the case of the halv special, the dialect serves as an authenticating resource that produces authority for the proposal (Woolard Citation2016) and contributes to the enregisterment of both the halv special and the dialect as social emblems of Gothenburgness. In Johnstone’s terms, götebosska has reached “third order indexicality”, and proof of this is Andersson’s (Citation2021) Göteborgslexikon, which constitutes “a highly codified list” which both Gothenburgers and non-Gothenburgers draw on to “perform local identity, often in ironic, semi-serious ways” (Johnstone Citation2006, 83).

The ironic and semi-serious tone is constant in the commentary on the halv special, where, for instance, Patrik Höstmad exclaims “Hallo eller!? Ni ä la änna goa” (“Hello or!? Aren’t you really something”) (Hallén Citation2019). The expression hallo eller!? appeared in Gothenburg in the 1980s and serves as a greeting phrase or call for attention with a light sceptical stance (Andersson Citation2021). In another Facebook thread, Reine Milder comments on the halv special with the expression “Gôtt mos!  ” (Radio P4 Citation2021), which since the 1990s has been Gothenburgish for “great”. Since the literal meaning of the expression is “good mashed potatoes’, using it in this context of course adds an extra dose of wit.

” (Radio P4 Citation2021), which since the 1990s has been Gothenburgish for “great”. Since the literal meaning of the expression is “good mashed potatoes’, using it in this context of course adds an extra dose of wit.

Witty word play and sarcastic and racist renaming of places

Comparing the commentaries on the halv special and the falafel, it is notable that while the comments on halv special frequently feature wordplay and the comments on falafel do not, the 2014 news piece that first mediatized the idea of raising a monument to falafel describes how Nazih Elsheikali draws on the local ludic repertoire of Gothenburg puns to brand his food. According to Askerup (Citation2014), Elsheikali was well-known not just for his falafel, but also for his linguistic performance and word play. He is cited as saying: “Vill man ha alla såser i (den är givetvis populärast i såslandet Sverige) får man en ‘Alingsås’” (‘If you want falafel with all the sauces, which of course is the most popular one in the sauce-country Sweden, you get an “Alingsås”’). The pun is based on the similarity of the word for sauce, sås, with the name of the small town Alingsås. This indicates that humour and word play is not recognized by the public as an enregistered feature of the falafel; it seems rather restricted to the halv special. For instance, in a Facebook thread, Per Irwert comments on the proposal of the halv special exclaiming “Wurst idea, ever!!!” (Radio P4 Citation2021). This is a trilingual pun that builds on the orthographic similarity between the Swedish and English forms of the adjective worst (värsta in Swedish) and the German noun Wurst (‘sausage’).

Another enregistered feature of Gothenburgness and the Gothenburger is the performance of a competitive stance towards the capital, Stockholm. This performance is often paired with wordplay. In the Facebook thread initiated by Jesper Hallén at the Social Democrat Party congress in 2019, Linda Fransson exclaims: “Nästa gång motionerar vi om en matchande puckostaty!” (“Next time we propose a matching monument of the pucko”) (Hallén Citation2019). Pucko is the name of a classic drink made of milk, sugar, and chocolate, which is traditionally ordered together with a halv special. Pucko is also a Swedish slang word for “idiot”, thus charging the post with ambiguity and paving the way for Lars Carlström’s response to Fransson’s post with an inferential pun: “kan ju inte ha en stockholmare som staty i gbg!” (“you can’t have a Stockholmer as a statue in Gothenburg!”). Similar puns are created in several of the comment threads on the halv special in 2021.

The first news piece on the falafel proposal appeared in the newspaper Göteborgs-Posten the day after they first reported on the halv special. Except for one outspoken positive and one neutral comment, all are negative. The negative comments are generally sarcastic and focus either on the politicians or on the migrants, reproducing political contempt, racism, and Islamophobia. For instance, Daniel Johansson alludes to the theory of replacement by stating that “a sculpture of a camel should be erected on the central square in Angered”, the most migrant dense neighbourhood in Gothenburg, and the square should be renamed “the Farm” (Moberg Citation2021). The suggested renaming of the square is based on the perception of the falafel as an index of replacement and racializes the residents of the Angered neighbourhood by presenting them as camel-breeders (or even as animals themselves).

On the same day, February 23, 2021, the extreme right digital news portal Samnytt published an article entitled “Här är rödgrönas plan för Göteborg: Langarnas torg med falafelstaty” (“Here is the red-green’s plan for Gothenburg: The Dealer Square with a monument to falafel”). Although it is not part of Göthenburgo’s motion to the City Council, they pick up on Elsheikali’s original suggestion in 2014, to rename the place Alibaba Square, commemorating his falafel stand. The central argument of the text is that the spokespersons for the falafel are naïve – “these people support their own decay without even understanding it” – and that what is presented as a gesture of tolerance and integration is rather “to signal their own goodness”. The argument is constructed by citing a Yemenite migrant, Luai Ahmed, who, based on his origins and access to the Arabic language and culture, supposedly confers authority to it (Woolard Citation2016): “Alibaba means a bandit, a horrible person, or a criminal throughout the Middle East. It comes from an Arab story about Alibaba and his 40 thieves. In everyday speech, a dealer is called Alibaba in the Middle East” (Kristoffersson Citation2021). However, this meaning of Alibaba is not recognized among scholars of Arabic; the story about Alibaba and the 40 thieves was added to the Arab collection of tales in a French translation and Alibaba is in fact part of an orientalist understanding of the Arab world (Pernilla Myrne, personal communication 2022-01-24).

These expressions of orientalism and replacement theory came as no surprise to the spokesperson for the falafel: “It was obvious […] they feel like we are taking over the culture somehow” (interview with Behtaji). The critical response towards the falafel, or all that it stands for, can be compared to the entrance of the hamburger onto the Swedish fast-food scene in the late 1950s. It soon became a “favourite hate object” for the political left, who saw the hamburger as a key symbol of American imperialism (Eriksson Citation2004, 110). Like the falafel, the hamburger was an imported dish that met criticism. Although these groups are ideologically opposite, they shared similar concerns about protecting what they perceived as Swedishness from foreign influence.

Goa gubbar: gendering and regendering class

Almost 20 years ago, the cultural critic Ulrika Stahre (cited in Jacobson Citation2005) wrote a column dreaming about “the definite extinction of the city of men (grabbstaden)”. Gothenburg had, in her view, been a “masculine ideal city”, where “the working-class and industrial culture has had only one gender”, for too long. Though she saw signs of the masculine hegemony being challenged, she was not optimistic: “An eroded male culture that does not cope with differences promises no lively future. In short, Gothenburg’s good guys (goa gubbar) are not very good.” A central notion in her narrative is that of goa gubbar. In Agha’s (Citation2011) terminology, goa gubbar is a figure of personhood tightly linked to a traditional local identity or form of Gothenburgness. While go and the plural goa is Gothenburg dialect for “good”, the term gubbar literally means old men, but the expression is commonly used in Gothenburg as a strongly value-laden appellative for men of all ages, perhaps particularly in sports and male dominated workplaces (Andersson Citation2021, 79–80).

This figure of personhood is sometimes cited in the media commentary on the halv special. In the Facebook thread initiated by Radio P4 on the proposal for a monument to the halv special, Peter Lorentzon defends the idea by stating that “för att vi är Goa gubbar. Ni som inte är föda här fattar inte” (“because we are Goa gubbar. You who were not born here don’t get it”). The comment combines the enregisterment of Gothenburg identity as male with the performance of place-based power/knowledge to produce exclusion. By stating that “you who were not born here don’t get it”, the comment reproduces the logic of descent and territory as criteria for collective understanding and ultimately belonging.

In the extract below from the interview with Jesper Hallén, he associates the halv special with the figure of goa gubbar (line 8) and reflects on its ambivalent and contentious social meaning as potentially framing the monument as reactionary (lines 2-4, 9):

JESPER: What image of Gothenburg do we want to send out? I do not

know, maybe – yes, I’m not sure you want to send out that picture, the halv

special city, kind of, <laughs > it is not very fun, it is s– it is also a bit

backward-looking maybe, but, uh, yeah, I do not know.

JOHAN: In what sense would it be backward-looking?

JESPER: No, I do not know. … It’s well – I do not know –

JOHAN: Who, who eats halv special?

JESPER: Maybe it’s associated with, with goa gubbar, or something.

Such, such a goa gubbar mentality may not always be so fun.

In a review of the new lexicon of Gothenburgish (Andersson Citation2021), Lundberg (Citation2022) ends with a critical note on what she perceives as a “subjective” selection of word-entries, which is male-biased and does not reflect the influence on the dialect of the city’s current linguistic and cultural diversity. The figure of personhood, goa gubbar, is then evoked with a critical ironic stance:

With an overly one-sided selection, a dialect lexicon risks being reduced to a collection of madeleine cakes for good old men [goa gubbar]. In a vital Gothenburgish, both Ada [the name of a traditional female Gothenburg persona] and Angered [the name of Gothenburg’s most migrant-dense neighbourhood] should be included instead. (Lundberg Citation2022)

The middle class’s ambivalent attitude towards gentrification

By celebrating fast-food and folk taste, both the falafel and the halv special seem to “question the elite-oriented as well as elite-driven nature of public commemoration that, closed within the meanings produced by/for the symbolic elites, [have] remained distant from public understanding and expectations of collective history.” (Krzyżanowska Citation2016, 470). However, the two spokespersons, in different ways, both represent the Swedish middle class, a symbolic elite, that by its social position and semiotic labour in favour of the halv special or the falafel necessarily remains distant from the historically marginalized positions of class, gender, and race that they aim to commemorate. The interviews show how this class position produces an ambivalent attitude towards social and urban change: Hallén describes gentrification as “unavoidable” if the city is to “develop”, although he thinks the process was too radical and quick in Kvillebäcken. Behtaji, who runs the Jenin Grill art gallery in Kvillebäcken, states on the one hand that art generally “marks whiteness”, and that this racial indexicality of art constrains its audience: “art does not attract people from ‘the hood’ (orten)”. On the other hand, an art gallery can contribute to gentrification by making the neighbourhood more attractive; Behtaji therefore conceptualizes himself, as an artist and gallery owner, as “part of the problem” (see Gonçalves and Milani this issue, Pennycook this issue, who discuss artists as cultural mediators).

Conclusion

The analysis has shown how citizens engage in the process of erecting public monuments, and how they link this to the identity formation of places and personae, as well as to local power regimes: who has the right to say and decide what persons, foods, cultures, etc. shall be turned into monuments, and hence be publicly recognized as part of Gothenburg and Swedish society. They also link it to wider processes and concerns, such as Swedish welfare policies, migration, and integration, and the commentary signals how the citizens’ engagement is influenced by and potentially influences power relations.

In analogy to how colonial history and structures of power hinder the marketization of a typeface designed for expressing a modern and positive image of Arabic and the Arab world by drawing on local dialect and humour (Järlehed and Fanni Citation2022), low status and accentuated foodstuffs like the falafel are judged as not appropriate for public art, nor for play. The “continued rearticulation of colonial distinctions between Europeanness and non-Europeanness – and, by extension, whiteness and non-whiteness” (Rosa and Flores Citation2020, 90) determines who has the right and legitimacy to play with the nation’s and the city’s language and culture.

At the same time, the analysis indicated ongoing shifts in the enregisterment of both halv special and götebosska – features traditionally associated with the figure of personhood of the Gothenburger –, with entrenched indexicalities of masculinity and whiteness being challenged by voices from a new and more diverse Sweden.

The CFLF and Gothenburg city have developed a standardized procedure for embellishing the city with public art. The analysis reveals how the semiotic resources and practices involved in the procedure contribute to the legitimization and challenge of power interests. Since the procedure relies on the participation of the citizens, it generates questions about cultural inclusivity, “addressing class, race and other systems of hierarchy and exclusion” (Caminha et al. Citation2018, 12). The analysis of the media commentary in this article illustrates, on the one hand, how aesthetic and ideological criteria are evoked and debated in the selection of public art. On the other hand, the procedure invites a critical discussion regarding the city administration’s deployment of the beautification program to legitimize power and make the citizens feel they are participating in the governance of the city (Caminha et al. Citation2018, 13).

According to Charles Felix Lindberg’s will, the interest on the fund is to be used every three years for the city’s decoration and beautification. This creates opportunities for citizens to influence the city’s public environments with proposals, which can have a positive impact on citizens’ commitment to and participation in the city’s transformation processes. Participating in and influencing one’s local environment strengthens the feeling of community and security in public places, which in turn strengthens the city of Gothenburg from a democratic perspective. (Kulturnämnden Göteborgs Stad Citation2021)

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback on this paper, as well as Jesper Hallén and Roozbeh Behtaji for sharing their thoughts on the two monuments with me.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Johan Järlehed

Johan Järlehed is an Associate Professor in Multilingualism and Sociolinguistics at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. He is doing research on the interaction of language, images, and space in processes of social and economic change. His work can be read in journals such as Social Semiotics, Language & Communication, Linguistic Landscape, Visual Communication, Multilingual Margins, and the International Journal of Multilingualism.

Notes

1 Before this dish was invented, hotdogs in Sweden were served with either bread or mashed potatoes. A “special” includes both, a “whole special” comes with two sausages and a “half special” with one.

2 All translations from Swedish to English have been made by the author.

3 The last point seems to have missed the proposers’ explicit statement that a woman should be represented in the artwork, since “Gothenburg is lacking monuments to women”.

References

- Agha, Asif. 2005. “Voice, Footing, Enregisterment.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 15 (1): 38–59. doi:10.1525/jlin.2005.15.1.38.

- Agha, Asif. 2011. “Large and Small Scale Forms of Personhood.” Language & Communication 31 (3): 171–180. doi:10.1016/j.langcom.2011.02.006.

- Andersson, Lars-Gunnar. 2021. Göteborgslexikon. Stockholm: Morfem.

- Andersson, Roger, Bråmå Åsa, and Hogdal Jon. 2010. Fattiga och rika - segregerad stad: flyttningar och segregationens dynamik i Göteborg 1990-2006. Göteborg: Göteborgs stad.

- Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2014. “Mediatization and Sociolinguistic Change: Key Concepts, Research Traditions, Open Issues.” In Mediatization and Sociolinguistic Change: Key Concepts, Research Traditions, Open Issues, edited by Jannis Androutsopoulos, 3–48. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110346831.3.

- Askerup, Fredric. 25 January 2014. “Klassikern som Möter Motstånd.” Göteborgs-Posten, 8–13. https://www.gp.se/1.432697.

- Bingham-Hall, John. 2015. “Public Art as a Function of Urbanism.” In The Everyday Practice of Public Art, edited by Cameron Cartiere, and Martin Zebracki, 161–176. Oxon: Routledge.

- Cameron, Stuart, and Jon Coaffee. 2005. “Art, Gentrification and Regeneration – from Artist as Pioneer to Public Arts.” European Journal of Housing Policy 5 (1): 39–58. doi:10.1080/14616710500055687.

- Caminha, Kjell, Håkan Nilsson, Oscar Svanelid, and Mick Wilson. 2018. Public Art Research Report. Stockholm: Swedish Public Art Agency. https://statenskonstrad.se/app/uploads/2019/03/Public_Art_Research_Report_2018.pdf.

- Despotović, Katarina, and Catharina Thörn. 2015. Den Urbana Fronten: En Dokumentation av Makten över Staden. Stockholm: Arkitektur.

- Drakenfors, Thomas. 25 May 2000. “Han Uppfann Specialen – Kunde Inte Välja Mellan mos och Bröd.” Göteborgs-Posten. Accessed 2021-01-19. https://drakenfors.tumblr.com/post/43387141735/han-uppfann-specialen-kunde-inte-v%C3%A4lja-mellan.

- Eriksson, Leif. 2004. Korv, mos och Människor. Stockholm: Bonnier Fakta.

- Florin Persson, Erik. 2021. Film i Stadens Tjänst: Göteborg 1938–2015. Lund: Mediehistoriskt arkiv.

- Franzén, Mats, Nils Hertting, and Catharina Thörn. 2016. Stad Till Salu: Entreprenörsurbanismen och det Offentliga Rummets Värde. Göteborg: Daidalos.

- Göteborgs stad. 2017. Jämlikhetsrapporten 2017: Skillnader i livsvillkor i Göteborg. http://goteborg.se/wps/wcm/connect/3fe012fe-9367-4bd9-a0e9-52999da2ee7d/J%C3%A4mlikhetsrapporten2017_171219.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

- Göteborgs Stad. 2020. “Charles Felix Lindbergs Donationsfond-Arkiv.” Göteborg Konst. Accessed 2021-03-30. https://goteborgkonst.se/category/charles-felix-lindbergs-donationsfond/.

- Hall, Tim, and Iain Robertson. 2001. “Public Art and Urban Regeneration: Advocacy, Claims and Critical Debates.” Landscape Research 26 (1): 5–26. doi:10.1080/01426390120024457.

- Hallén, Jesper. 2019. “Riktigt kul att vår Motion om en Halv Special-Staty Gick Igenom!.” Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/hisingen/posts/10160308878454988.

- Hodge, Bob, and Gunther R. Kress. 1988. Social Semiotics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Holgersson, Helena, Catharina Thörn, Håkan Thörn, and Mattias Wahlström. 2010. Göteborg Utforskat: Studier av en Stad i Förändring. Göteborg: Glänta.

- Hughes, Jessica M. F., and Karen Tracy. 2015. “Indexicality.” In The International Encyclopedia of Language and Social Interaction, edited by Cornelia Ilie and Todd Sandel, 1–6. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9781118611463.wbielsi078.

- Hübinette, Tobias, and Catrin Lundström. 2014. “Three Phases of Hegemonic Whiteness: Understanding Racial Temporalities in Sweden.” Social Identities 20 (6): 423–437. doi:10.1080/13504630.2015.1004827.

- Jacobson, Maria. June 9, 2005. “Gryende Insikter om Manlighet.” Alba 3: 1–9. https://www.alba.nu/sidor/18700.

- Järlehed, Johan, and Maryam Fanni. 2022. “The Politics of Typographic Placemaking: The Cases of TilburgsAns and Dubai Font.” Visual Communication. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/14703572211069612.

- Järlehed, Johan, Maria Löfdahl, Tommaso Milani, Helle Lykke Nielsen, and Tove Rosendal. 2021. “Entrepreneurial Naming and Scaling of Urban Places: The Case of Nya Hovås.” In The Economy in Names: Values, Branding and Globalisation, edited by Katharina Leibring, Leila Mattfolk, Kristina Neumüller, Staffan Nyström, and Elin Pihl, 71–86. Uppsala: Institute for Language and Folklore.

- Johnstone, Barbara. 2006. “Mobility, Indexicality, and the Enregisterment of “Pittsburghese”.” Journal of English Linguistics 34 (2): 77–104. doi:10.1177/0075424206290692.

- Kristoffersson, Simon. 23 February 2021. “Här är Rödgrönas Plan för Göteborg: Langarnas Torg med Falafelstaty.” Samnytt. https://samnytt.se/har-ar-rodgronas-plan-for-goteborg-banditernas-torg-med-falafelstaty/.

- Krzyżanowska, Natalia. 2016. “The Discourse of Counter-Monuments: Semiotics of Material Commemoration in Contemporary Urban Spaces.” Social Semiotics 26 (5): 465–485. doi:10.1080/10350330.2015.1096132.

- Kulturnämnden Göteborgs Stad. 2021. “Yttrande till kommunfullmäktige över motioner samt förslag till fördelning av disponibla medel ur Charles Felix Lindbergs donationsfond”. https://www4.goteborg.se/prod/Intraservice/Namndhandlingar/SamrumPortal.nsf/81FA4F47EF2E8FCBC12586D80022DE86/$File/8%20Yttrande%20till%20KF%20motioner%20CFL%20donationsfond%20NY.pdf?OpenElement.

- Lindberg, Charles Felix. 1909. “Charles Felix Lindbergs testamente”. https://goteborgkonst.se/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/CFL-Testamente.pdf.

- Lundberg, Rebecca. 15 January 2022. “Ada och Beda Fattas i Nytt Göteborgslexikon.” Göteborgs-Posten. https://www.gp.se/1.63591912.

- Moberg, Carl Petersson. 23 February 2021. “De Vill ha en Falafelstaty på Backaplan.” Göteborgs-Posten. http://www.gp.se/1.41758112.

- Nash, Jennifer C. 2008. “Re-Thinking Intersectionality.” Feminist Review 89: 1–15.

- Norrick, Neal R. 2003. “Issues in Conversational Joking.” Journal of Pragmatics 35: 1333–1359.

- Pred, Allan. 2000. Even in Sweden: Racisms, Racialized Spaces, and the Popular Geographical Imagination. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Radio P4. 2021. “Vad Tycker du? Ska Göteborg få en Sådan här ‘Matig’ Staty? Och var ska den stå i så Fall? Kommentera Gärna!.” Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/P4SRGoteborg/posts/10159090317853529.

- Rosa, Jonathan, and Nelson Flores. 2020. “Reimagining Race and Language.” In The Oxford Handbook of Language and Race, edited by H. Samy Alim, Angela Reyes, and Paul V. Kroskrity, 90–107. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190845995.013.3.

- Socialdemokraterna Göteborg. 2019. “Kongresshäfte, del 2”. Accessed 2021-01-28. https://socialdemokraternagoteborg.se/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Kongressh%C3%A4fte-del-2-1.pdf.

- Svenska Akademien. 2021. “falafel.” In Svensk Ordbok, 2nd ed. Stockholm: Svenska Akademien. https://svenska.se/tre/?sok=falafel&pz=2.

- Swedish Government. 2017. Policy for Designed Living Environment. https://www.government.se/information-material/2019/01/policy-for-designed-living-environment/.

- Thörn, Catharina, and Helena Holgersson. 2016. “Revisiting the Urban Frontier Through the Case of New Kvillebäcken, Gothenburg.” City 20 (5): 663–684. doi:10.1080/13604813.2016.1224479.

- Woolard, Kathryn A. 2016. Singular and Plural: Ideologies of Linguistic Authority in 21st Century Catalonia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.