ABSTRACT

The civic unrest in Gwangju in May 1980 marks one of the most important turning points in modern South Korea’s history and collective memory. The so-called Gwangju Uprising did nothing less than herald South Korea’s transition from dictatorship to democracy. Images played an important role in this critical moment of change. Footage of the security forces quelling unrest showed the outside world what was happening in the city. One of the avenues through which the protests have been consistently reimagined is popular film. This article asks how the story of radical political change is articulated in A Taxi Driver, South Korea’s most-viewed and highest-grossing film on the Uprising. Contrasting with previous research, I argue, first, that A Taxi Driver adds to our knowledge of the Gwangju protests a story about the essential role of images in the contentious politics of the democratisation movement. Second, I contend that the film produces a specific account of the Uprising, one that allows us to see the politics of contention as an interrelation of different visibilities, which includes symbolic imagery, inside/outside configurations and male/female agency.

Introduction

In this article, I ask how the story of radical political change is articulated in the motion picture A Taxi Driver, South Korea’s most-viewed and highest-grossing film on the so-called Gwangju Uprising.Footnote1 The Uprising in the city of Gwangju in May 1980 was arguably one of South Korea’s most tragic yet important turning points on its road to democratisation.

I make two arguments. First, in contrast to previous research (e.g. Ahn & Lee, Citation2019; Ghosh, Citation2012; C. H. Kim, Citation2008; K. H. Kim, Citation2002; S. Y. Kim, Citation2006; Citation2010; Morris, Citation2010; Rhee, Citation2019), I contend that A Taxi Driver adds to our knowledge of the upheaval a story about the essential role of images in the contentious politics of the civic movement. For images were crucial in mediating the events of Gwangju to a global public (see also Jackson, Citation2020). Second, I argue that the film produces a specific account of the Uprising, one that allows us to see the politics of contention as an interrelation of different visibilities, which includes symbolic imagery, inside/outside configurations and male/female agency.

Research on the Gwangju Uprising has made a number of important contributions to the study of social movements, examining the protests in light of their memory politics (H. Kim, Citation2011), the socioeconomic contradictions of South Korean society (Ahn, Citation2003), the processes of identity construction during the revolt (Kim & Han, Citation2003) and the active role of women in the resistance (Kang, Citation2003). Scholars have also cited media representations of the protests as a dominant theme of such research (Kim & Han, Citation2003). Within this field of study, focus has been on the (biased) coverage of, for instance, domestic newspapers or television stations.

However, the crucial role that images played in this watershed moment of South Korean history has not been considered by previous studies. For as footage of security forces crushing public protests aired via global media networks, the outside world became aware of what was happening during the nine days of unrest in Gwangju. The important role of images in disseminating and documenting knowledge about the Uprising has also been acknowledged by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which has granted related photographs and video material the status of “world documentary heritage” (Cho, Citation2011). In the nomination form sent to UNESCO, the May 18 Memorial Foundation, the principal advocacy group for the Gwangju Uprising, stated that:

Films depict the scenes [of suppression] even more clearly. Footage of Gwangju in May 1980 (such as that filmed by Jurgen Hinzpeter from NDR, Germany and others representing NHK, Japan) was broadcast worldwide. These films were later imported and secretly televised, playing a major role in revealing the truth about the May 18th Democratic Uprising (May 18 Memorial Foundation, Citation2011, p. 5).

Besides pointing to the well-established logic according to which images play a key role in mediating events to us (see, e.g., Lisle, Citation2019; Moeller, Citation1999; Postman, Citation1987), this statement, interestingly, singles out one particular individual – Jürgen Hinzpeter – within the greater politics of contention.Footnote2 Hinzpeter, a camera operator for the German public broadcaster NDR, was one of the few foreign journalists in Gwangju at the time and is said to have provided most of the footage of the crackdown to the outside world (Choe, Citation2017; Choi & Shin, Citation2016; Jackson, Citation2020; Pfützner, Citation2019). Hinzpeter’s peculiar role in the protests would be dramatised in the highly popular 2017 film A Taxi Driver, which is the central object of analysis for this article.

To understand the significance of the Gwangju Uprising for South Korean history, it is not only important, as Don Baker (Citation2003, p. 87) suggests, to ask what happened but also to question how these events are remembered and represented to a broader public. One of the avenues through which the protests have been consistently reimagined over the years is commercial film productions. Examples are 26 Years (2012), A Petal (1996), Fork Lane (2017), May 18 (2007), Oh! Dreamland (1989), Peppermint Candy (1999), The Song of Resurrection (1991) and The Old Garden (2007). By examining A Taxi Driver’s storytelling of radical political change, I draw on scholarship that maintains that popular culture artefacts such as film, music and video games affect people’s understanding of political events (e.g. Caso & Hamilton, Citation2015; Grayson et al., Citation2009; Neumann & Nexon, Citation2006; Shim, Citation2017; Weldes, Citation1999).

This article is structured as follows. The first section provides a brief outline of the significance of the Gwangju events for South Korea. The second section illuminates the incumbent South Korean president’s predilection for popular film from the perspective of current scholarship on popular culture and politics, and reveals what an interpretive research strategy vis-à-vis film can look like. The third section explains what sets A Taxi Driver apart from other dramas about the Gwangju protests. The fourth section gives a short synopsis of the film, before providing an interpretive discussion of it. The conclusion situates the findings in the broader context of the Special Issue’s overarching theme of visualising Korea.

Significance of the Gwangju Uprising

The public unrest in the city of Gwangju in May 1980 arguably represents one of the most important turning points in modern South Korean history and collective memory (see, e.g., Ahn, Citation2002; J. Choi, Citation2006; Katsiaficas & Na, Citation2006; Y. Kim, Citation2003; Shin & Hwang, Citation2003). Gi-wook Shin, for instance, has called the Uprising “the single most important event that shaped the political landscape of South Korea in the 1980s and 1990s” (2003, p. 10). Soon after Army General Chun Doo-hwan seized power in a military coup in December 1979, he declared martial law across the country to suppress the public protests that had re-emerged after the assassination of President Park Chung-hee. Park had been killed by the director of the national intelligence agency two months before. Chun gave orders to arrest opposition leaders and shut down the country’s universities and the national parliament.

In Gwangju, hundreds of students gathered on 18 May at a local university to protest its closing and to rally for democratic rights. While the military cracked down on the student demonstration, citizens of Gwangju – some armed with weapons obtained by breaking into police stations and armouries – joined the protests. As violent clashes erupted between protesters and soldiers in the following days, many civilians were shot. On 27 May, the Uprising was crushed – with estimates ranging between 200 (government assessments) and 2,000 people having been killed, most of them civilians (assessments of local civic groups).

Even though the protests did not immediately bring about democratic change in South Korea – Chun would remain in power until 1988 – the events, which became known as the Gwangju Uprising, constitute a critical juncture in South Korea’s transition from authoritarian rule to democratic governance (Y. Kim, Citation2003). Apart from the far-reaching consequences for South Korea’s domestic development, the events of Gwangju also had international dimensions. George Katsiaficas and Gerardo Rénique (Citation2012) contend that the protests served as an inspiration for other democratic movements in Asia (see also Katsiaficas & Na, 2003). South Korea’s democratisation, resuscitated in Gwangju and culminating at the end of the 1980s in the restoration of civil rights and constitutional reforms, fundamentally impacted the country’s international relations with other states as well as with international organisations. Such after-effects included, for instance, South Korea’s accession to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in 1996 and the shift in the United States–Korea security alliance from being interest- to value-based (White House, Citation2017; see also Hwang, Citation2017).

With 18 May becoming a national day of commemoration, the Gwangju Uprising continues to impact contemporary domestic politics. For instance, at the May 2017 ceremony to honour the protests, President Moon Jae-in promised to open a new investigation into the order to use deadly force against civilian protesters. Moon was a prominent human rights lawyer in the 1980s, working to defend activists persecuted for defying the Chun regime. He was imprisoned under Park’s dictatorship in the 1970s for opposing the “Yushin” constitutional reform. Shortly before the ceremony, Chun published his memoirs, in which he denied any responsibility for suppressing the demonstrations and portrayed himself as a victim (H. Choi, Citation2017). Conservative lawmakers continue to describe the events of Gwangju as anti-government and pro-North Korean riots, revealing the lasting, ideologised legacy of the civic movement.

Popular Culture, Politics and the Gwangju Protests

Moon has a special relationship to the events in Gwangju. This is not only evident from his aforementioned defending of civil rights cases during the Chun era or his pledge to reopen the investigation into the shooting of local protesters. Moon also has an avid interest in the cinematic representation of civil rights issues and of the Gwangju Uprising per se. In 2014, Moon, dubbed one of the leading politicians of the centre-left, watched The Attorney, a popular film based on a court case in which human rights lawyer Roo Moo-hyun – president of South Korea between 2003 and 2008, and a close ally of Moon in the 1980s – defended student activists from false claims of espionage in the Chun years (Donga Ilbo, Citation2014).

In 2017, Moon, who had become South Korea’s president earlier that year, watched A Taxi Driver during a special screening at a local cinema in Seoul. The film tells the story of Kim Man-seob, a taxi driver, who gets drawn into Hinzpeter’s reporting on the Gwangju protests. In the film the taxi driver is played by Song Kang-ho, arguably South Korea’s best-known character actor, and the journalist by Thomas Kretschmann, a German actor with a profile for international film productions. In attending this highly publicised event, Moon would be accompanied by Edeltraut Bramstaedt, the wife of Hinzpeter, and Song, who also starred in The Attorney. Moon was quoted as saying:

The truth about the Uprising has not been fully revealed. This is the task we have to resolve. I believe this movie will help resolve it. I also felt that the Gwangju Democratisation Movement was always trapped in Gwangju, but now it seems to spread to the people. I think this is the great strength of the movie (Blue House, Citation2017).Footnote3

What makes Moon’s statement remarkable is not only the reference to the power of popular film to reach a wide audience, but also his belief about what this particular one is capable of delivering: a lesson on a historical event, telling the truth about the Gwangju Uprising. Thus, popular film not only (apolitically) entertains people, but also (politically) educates them about certain issues and events. In this way, Moon’s remarks give an indication of the co-constitution of politics and popular culture.

First, heads of states – and governments at large – make use of film, music or visual art to convey political messages, suggesting that political practice cannot be separated from its visual representation (Neumann & Nexon, Citation2006; Shim, Citation2017). In the present case, publicising the screening of this particular film and not others with, say, an anti-American or anti-Japanese undertone helps build Moon’s profile as a politician promoting civil rights and the rule of law (R. Kim, Citation2017). Second, and more importantly, Moon’s statements point to one of the key contributions of the literature on politics and popular culture: namely, that film and other pop cultural artefacts function as a frame of reference affecting what people – elite and mass audiences alike – know of certain political issues or developments (Caso & Hamilton, Citation2015; Daniel & Musgrave, Citation2017; Light, Citation2001).

A good example of how popular films and television series have shaped people’s understandings of certain issues is the question of torture. Recent scholarship has outlined how films and television series such as Zero Dark Thirty (2012) and 24 (2001–2014) have affected public opinion and political debates about torture, portraying it as an acceptable, legitimate and/or effective strategy of interrogation (e.g. Adams, Citation2016; Birkenstein et al., Citation2010; Pautz, Citation2015; Schlag, Citation2019; Westwell, Citation2014). For instance, Michelle C. Pautz (Citation2015) found that the films Zero Dark Thirty and Argo (2012) positively affected audiences’ opinions about the actions of the US government in its War on Terror. Alex Adams (Citation2016), in a comprehensive study of literary, filmic and other pop-cultural representations of torture, showed meanwhile that these sources – through their embedding in political and military discourse – contribute to the normalisation of the practice.

Other familiar examples of the co-constitution of politics and film are popular representations of (certain) people and places to global audiences. States such as Kazakhstan, Egypt and North Korea have protested that the films Borat (2006), Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014) and The Interview (2014) have ridiculed their respective countries, cultures and/or leaders. While their reactions to the release of these films were diverse – Kazakhstan placed advertisements in major media outlets denouncing Borat, Egypt banned Exodus, and North Korea threatened to take action against the US and Sony Pictures Entertainment, the distributor of The Interview – these examples demonstrate the (anticipated) impact of popular film on people’s knowledge of certain places, issues and events.

Returning to A Taxi Driver, the politics of it not only become evident due to the approval expressed by South Korea’s president (“telling the truth about Gwangju”) but also because of the contrasting disapproval voiced by the Chinese government, which banned the film from Chinese theatres, and removed all online posts about it, due to historical resemblances to the Tiananmen Square incident of 1989 (Hong, Citation2017). In this vein, popular culture artefacts not only represent certain events and developments, but articulate particular truth-claims about them too – which, in turn, shape people’s understandings of them. Popular culture is thus implicated in constructing and circulating ideas about people, places and issues, thereby making a separation of the cultural and the political ultimately unsustainable.

So instead of isolating the domain of (popular) culture from the world of politics, both spheres need to be theorised as forming a continuum – one in which “[e]ach is implicated in the practices and understandings of the other“ (Grayson et al., Citation2009, p. 158). As such, it is important to consider how political imaginations are articulated through film and how the medium provides a scheme through which to make sense of the world (Power & Crampton, Citation2005). For (re-)imagination should not be understood as mere fantasy: it is an important political resource that allows one to share a sense of belonging to a political community, something that entails particular identity and/or meaning constructions (Anderson, Citation1991; Said, Citation1978).

To focus on practices of meaning-making, I make use of an interpretive research approach. Therefore, I follow a problem-driven line of inquiry, thereby aligning the analysis to the overall research purpose (Shapiro, Citation2002): here, tracing the story of radical political change in A Taxi Driver. For the discussion of this film, I adopt a research design that is attentive to changes in focus (Schwartz-Shea & Yanow, Citation2012). My analysis can then be best described as a process of back and forth between research question and empirical material. In other words, I watched the film with an eye to distinct or recurring patterns, which in turn informed the analytical categories. In this vein, I have identified particular narrative features as giving meaning to Gwangju’s story of contentious politics. One such example, as the empirical discussion outlines in more detail, is the film’s reference to national symbolic imagery. How the South Korean flag – as a particular marker of national identity – is used in A Taxi Driver reveals the identity politics of the film’s storytelling: namely, helping to depict the struggle for democratic change in terms of a non-patriotic military regime (no flag shown) pitted against patriotic, pro-democratic citizens (flag shown).

Why A Taxi Driver?

The civil unrest in Gwangju has, as noted, continued to capture the imagination of South Korean filmmakers and audiences ever since. Among the array of films that relate to the fateful events of May 1980, A Taxi Driver stands out for several reasons.

First, some authors have noted that the film, in contrast to other cinematic depictions of the Uprising including A Petal (K. H. Kim, Citation2002), May 18 (Morris, Citation2010) and Peppermint Candy (Ghosh, Citation2012), provides an outsider’s perspective on the events (Ahn & Lee, Citation2019; Rhee, Citation2019). To repeat, the film tells the story of a Seoul taxi driver who gets tangled up in Hinzpeter’s reporting on the Gwangju protests. However, as the empirical discussion shows, the position of the outsider is rather multi-layered and should not be taken for granted.

Second, A Taxi Driver is unique because it is by far the most-viewed and highest-grossing film of the cinema genre addressing the Gwangju demonstrations. For Joo-yeon Rhee (Citation2019, p. 91), the film even marks a “new turning point” in what she calls “5.18 cinema”, because it attracted more than 12 million viewers of all age groups. Pointing out the motion picture’s wide social resonance is important from the perspective of the popular culture and politics literature, as its success increases its potential to affect public knowledge about the events of Gwangju.

Third, as noted before, the film also provides a crucial reference point for the country’s highest political class. The South Korean president not only personally endorsed the film, but also suggested that it would help finally reveal the truth about the protests (Blue House, Citation2017).

Fourth, the Korean Film Council – the main government agency working to promote Korean films worldwide – selected A Taxi Driver as the country’s entry for Best Foreign Language Film at the 2018 Academy Awards. In a press release, the Council explained that:

A Taxi Driver manages to illustrate not only the distinct characteristics of South Korea but also how human rights and democratization have been achieved in the Asian region […]. With the film’s universal humanism, [the Council] believes that the core message of A Taxi Driver will be well received by international audiences (cited in Kil, Citation2017).

The selection itself reveals that acclamation and social recognition of A Taxi Driver rest on the understanding that it functions as an authoritative account of a historical event, as well as of issues that have wider international significance – including change, democratisation and human rights.

Finally, and most importantly, A Taxi Driver is essentially a film about filming. As such it reveals a form of reflexivity that is otherwise completely absent in 5.18 cinema (see, e.g., Ghosh, Citation2012; C. H. Kim, Citation2008; K. H. Kim, Citation2002; S. Y. Kim, Citation2006; 2010; Morris, Citation2010; on reflexivity in film, see Stam, Citation1992). That is, by addressing itself as a medium of expression, A Taxi Driver echoes the article’s argument that filming has been constitutive of the contentious politics of Gwangju – a facet overlooked by recent discussions of the film (see Ahn & Lee, Citation2019; Jackson, Citation2020; Rhee, Citation2019).

Statements about the significance of images are made several times in the film via, tellingly, the figure of the TV journalist. For instance, as he puts it: “Once this footage [about the violent suppression of the protests] airs, the entire world will be watching” (Jang, Citation2017). In another scene, he pledges: “As soon as I get back to Japan, my footage will hit the news. The whole world will see” (Jang, Citation2017). The importance of visual imagery in communicating the events to a broader (inter)national public is also evident in the scene that shows the bombing of a local TV station by the military. Preventing the circulation of footage of civic unrest being quelled thus has strategic, military value.

Another example that illustrates the self-awareness of the film is its acknowledgement of the presence of the audience in the final scene. In it, the real Jürgen Hinzpeter addresses the taxi driver and the film’s viewers directly with a message. He thus breaks the so-called fourth wall, a convention in the performing arts that assumes an imagined barrier separating actors from spectators – thereby creating social and spatial distance between them (Brown, Citation2012).

As Hinzpeter says: “If I could find you through this footage, and then meet you once again, I would just be so happy. I’d rush over to Seoul in an instant, ride with you in your taxi and see the new Korea” (Jang, Citation2017). Hinzpeter’s reference to the “new Korea” – arguably appreciating the role of the Gwangju Uprising in the country’s transition from dictatorship to democracy – is paraphrased in the following sections.

Visualising the “New” South Korea in A Taxi Driver

Synopsis

At the beginning of the film, the audience first encounters the oppressive force of the autocratic system: protesters in Seoul demanding the lifting of martial law are beaten, chased and attacked with tear gas. While the opening scene shows South Korea’s looming democratic transition, none of this is of interest to Kim, the taxi driver, who rails against the demonstrators. For instance, early in the film he says that the “spoiled bastards [the protesters] need to be shipped off to Saudi Arabia” (Jang, Citation2017), where he had worked in the 1970s as a construction worker. At the same time, he is portrayed as being more concerned with the damage to his car, caused by one of the fleeing protesters, and the ensuing costs for repair. Kim, who is notoriously overdue on his rent, is in desperate need of money. This is due to the medical treatment that his late wife had received. As a widower, he must now take care of their daughter.

At a restaurant, he overhears a conversation among fellow taxi drivers from which he learns that a foreigner, Hinzpeter, would pay a lot of money for a day trip to Gwangju. Kim is portrayed as a clever and enterprising man. As a taxi driver he would always find a way, even eventually to Gwangju, which has been closed off by the military. Kim immediately leaves the restaurant to intercept the journalist. His motto “life is never fair”, which he expounds during a conversation with his pre-teen daughter, is juxtaposed with his work ethic, revealed to the audience in his remark that “a driver has to go where the customer says” (Jang, Citation2017).

The taxi driver has no interest in politics. While world-historical events take place on the streets of Gwangju – that is, the moment when the oppressive nature of the regime becomes evident and the democratic movement is crushed – he is having a sandwich on a rooftop. At the same time, Kim retains a firm belief in the integrity of the military. As he responds to reports about the abuse of protesters, he recounts, “I was an army sergeant. No soldier would ever do that [beating and stabbing anyone who passes by]” (Jang, Citation2017).

The taxi driver stands in contrast to Hinzpeter, a well-connected journalist, who has lived in Japan for the past eight years. Hinzpeter has a sense for big stories. As he states in a later scene, “A journalist has to follow the news” (Jang, Citation2017). He enters the country disguised as a missionary. After meeting with a local journalist, whom he trusts and has known for a long time, in a Seoul café, Hinzpeter learns that the government has declared martial law in Gwangju and is censoring the press. The local contact has organised a taxi for Hinzpeter that can take him to Gwangju and back to Seoul in the same day. Instead, Kim shows up and the two protagonists embark on their journey into the unknown.

Reimagining radical political change and the “new” South Korea

The narrative of change is manifested on different levels and in overlapping sites. There is, for instance, the nature of the interpersonal relationship of the protagonists, which changes from formal to cordial over time. For that, a scene inside the hospital is crucial. It is defined by the depiction of human suffering, with many dead or heavily injured protesters being shown on camera. In this moment, both protagonists come to realise the magnitude of the violent events they are witnessing. A terrified but also determined Kim says to the journalist: “We go together. I taxi driver, you taxi customer. Okay?” To which Hinzpeter replies: “Okay! Together” (Jang, Citation2017).

In other words, the two protagonists find common ground for joint action, despite being worlds apart at the beginning of the film: Kim, working in a low-wage sector, is uneducated and seeks to maximise his own gains; Hinzpeter is an educated, widely travelled, international journalist. The theme of change can also be observed in the site of the film itself, as it crosses different genres including comedy, drama and melodrama.

The character of the taxi driver is another site of change. Kim radically alters from indifference to the democratic uprising to his central involvement in it. In a clear change of beliefs about the military, Kim now asks himself: “Why were those soldiers acting that way? Beating and chasing people who weren’t doing anything” (Jang, Citation2017).

While change in A Taxi Driver is thus reflected in these “micro” sites – the interpersonal relationship of the protagonists, the film’s genre(s) and the taxi driver’s own character development – it is also evident at the “macro” level, in the depiction of the looming transition from dictatorship to democracy. Put differently, the “macro” level – which speaks to the question of how political change is represented in the film – provides the backdrop for those “micro” sites. The “new” South Korea is portrayed in the film by the interplay between the visibility and invisibility of symbolic imagery, the struggle between a Korean “inside” and a non-Korean “outside”, and the absence of active female agency in the civic fight for democratic change.

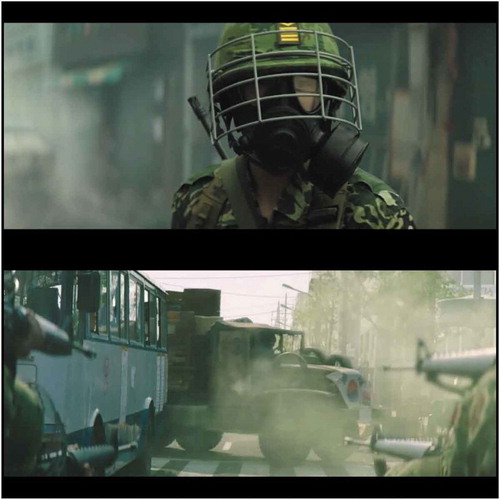

The first narrative feature of A Taxi Driver relates to both the visibility and invisibility of symbolic national imagery. Important to note is the taegukgi, the flag of South Korea, and the question of when this distinct symbol of national identity is shown. For what is striking is that the taegukgi is only seen in the film when the (causes of the) protests and the protesters themselves are depicted. The first such time is when Kim and Hinzpeter encounter students on a truck, but it also appears at other public demonstrations and in one hospital, where coffins are wrapped in the national flag (see ).

Figure 1. The struggle for the “new” Korea and the national flag in A Taxi Driver

All film stills are used with permission. COPYRIGHT © 2017 SHOWBOX AND THE LAMP. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

At the same time, the flag is virtually invisible when the military or other official institutions such as the police are shown. Furthermore, when violent acts are committed by soldiers, their faces are hidden behind gas masks, or the camera is positioned behind them so that the audience cannot see their faces (see below).

Studies in Cognitive and Social Psychology have shown that the hiding of faces impedes the building of emotional links between the viewer and the viewed (Fischer et al., Citation2012; Kret & Fischer, Citation2018). Masking the troops, whose uniforms, helmets, shields and/or weaponry remain clearly visible, thus allows focus to be solely on the generic appearance of a military presence.

Put differently, the depiction of common soldiers in A Taxi Driver – who are not seen displaying national symbols such as the taegukgi (national flag) – serves to imply that they could be from any country. As such, what takes place in Gwangju – that is, the brutal suppression of democratic protest – could realistically take place anywhere in the world.

The presence and absence of these particular markers – the taegukgi as national identity alongside the effacing of soldiers – helps to portray the struggle for the “new” South Korea explicitly in terms of an oppressive apparatus versus patriotic, pro-democratic citizens and not of Koreans versus Koreans, which it is, in fact, as well. Put simply, the film does not tell a story of Koreans shooting at Koreans – something that would have tainted the narrative of building a “new” Korea – but of soldiers firing at protesters.

The emphasis on these social (soldiers and protesters) and not national (Koreans) subjectivities implies that the killings of demonstrators could also happen elsewhere. It is the military system that demands the application of violence, not Korean soldiers. In this way, one can speak of a narrative of opposition between a “de-Koreanised” institutional apparatus and “Koreanised” protesters in A Taxi Driver. Wrongdoing, hence, was ordered from the top down and not committed from below. It is thus the military leadership that is culpable, and not its subordinates.

The second narrative feature of the film concerns the articulation of the “new” Korea as an ambivalent struggle between what can be called a Korean “inside” and a non-Korean “outside”. While others have noted the outsider position of the taxi driver (Ahn & Lee, Citation2019; Rhee, Citation2019), this, in fact, also applies to the figure of the journalist. At the same time, the taxi driver (the Korean) is contrasted with the journalist (the foreigner) – therein depicting a conflictual, inside/outside relationship. Even though their relationship changes from a formal to a cordial one as the film proceeds, both figures remain dependent on each other for their respective undertakings.

On the one hand, the film pays tribute to the real taxi driver, Kim Sa-bok, who has been sidelined in official accounts of the Uprising (Choe, Citation2017). As Hinzpeter puts it in the film, “Without him [Kim Sa-bok], news of the Gwangju Uprising would have never reached the world” (Jang, Citation2017). In this way, the film acknowledges the key role of the “insider” in an event of (inter)national importance. On the other hand, it was Hinzpeter who would be continuously praised, awarded and commemorated – even though he acknowledged the role of the taxi driver during his lifetime (see also Jackson, Citation2020). Hinzpeter was not only honoured with awards by South Korean journalist associations and civic groups, but also with an exhibition in and the honorary citizenship of Gwangju (Nam, Citation2017). Official memory of the Uprising is hence connected to the specific person of Hinzpeter. In May 2016, the local government of Gwangju erected a memorial to the German journalist following his death, and enshrined his remains alongside those of victims of the protests buried there (K. Choi, Citation2016).

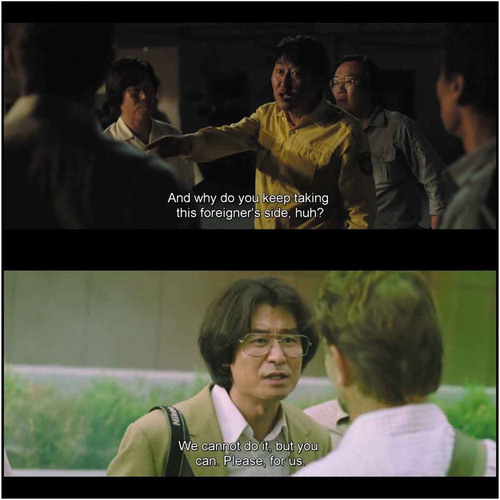

The tension between a Korean inside and a non-Korean outside is made evident in several scenes throughout the film. Some concern disputes between Hinzpeter and Kim, in which the taxi driver is asking his fellow countrymen to take his side. For instance, Kim, who wants to know if Hinzpeter was aware of the dangers of going to Gwangju, asks them: “Why do you keep taking this foreigner’s side, huh?” (Jang, Citation2017; see also ), even though he knew that the trip would be dangerous.

The audience also learns that the domestic press is not willing or able to tell the truth due to its (self-)censorship. An example is the national TV news, which misrepresents the democratic protests as pro-Communist riots. Important for the narrative feature of inside/outside is the scene in which a local journalist asks Hinzpeter to “prove all their [the government’s] lies wrong [as] we cannot do it, but you can. Please, for us” (Jang, Citation2017; see also ). Thus, the fate of the “new” Korea is in the hands of an outsider.

Important to note is the overall insinuation that the film is making with this inside/outside dichotomy: namely, the reliance on outside forces in relation to the larger questions of Korean domestic affairs. In the film’s case, this relates to the essential role of the foreign journalist – and, by extension, of images – in South Korea’s struggle for democracy.

In fact, Korea’s dependence on foreign powers is an ongoing national narrative with regards to the policy choices of a country that is said to be surrounded by more powerful players. Often, this situation is summarised with resort to the proverb “a shrimp among whales”, a popular description of South Korea’s position within the regional geopolitics of East Asia (see, e.g., The Economist, Citation2016; Shim & Flamm, Citation2013).

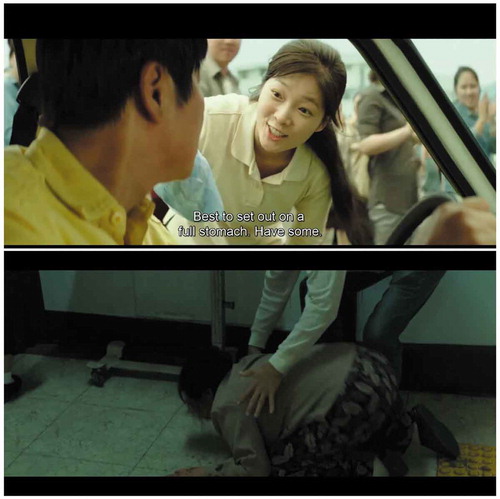

The final narrative strand to how A Taxi Driver tells the story of the “new” Korea refers to the (non-)depiction of women as participating in the protests. For what is striking is the complete absence of active female characters in the film. In these efforts to build the “new” South Korea, women are marginalised and invisible.

Meanwhile, men in the film are portrayed in multifaceted ways. They are, for instance, caring fathers, colleagues, honest workers, professionals, protesters and revolutionists, and individuals driven by noble causes. Women, however, are reduced to mourning mothers who cry for their victimised sons, or are cast as mere providers of food, thus acting in the traditional social position of caregiver (see ).

The relative obscuring of active female characters is in line with the gendered bias of 5.18 cinema previously highlighted by other scholars (e.g. S. Y. Kim, Citation2010; Rhee, Citation2019). The male-dominated tale of Gwangju’s democratic struggle also corresponds to an androcentric, nationalist discourse in South Korea according to which men fight bravely against and protect women (and children) from national enemies (Kim & Choi, Citation1998; Yuval-Davis, Citation1997). The story of brave-men-fighting is captured in the film, such as when taxi drivers risk their lives to save wounded demonstrators and, in a car chase, fight off more powerful government forces.

Kang (Citation2003), in her qualitative study of women’s experiences during the protests, shows that women in fact also played an active role in the contentious politics of Gwangju. As Kang found, women were involved in a wide range of activities during these events: not only “moving supplies, publicizing events, dealing with the dead bodies and cooking” but also motivating others to participate “through their roles as mediators between the leadership of the Uprising and the Gwangju citizens” (Kang, Citation2003, p. 206). Furthermore, women also articulated their opinions in the public and political spheres, revealing active female agency in the civic struggle for democratic change in South Korea (see also Lee & Chin, Citation2007; Shin, Citation2014).

Conclusion

I have investigated how the story of radical political change is articulated in the motion picture A Taxi Driver. I have argued, first, how the film adds to current knowledge of the Gwangju protests a story about the essential role of images in the contentious politics of the democratisation movement. Second, I have demonstrated how the film produces a specific account of the Uprising, one that allows the viewer to see the politics of contention as an interrelation of different visibilities, which includes symbolic imagery, inside/outside configurations and male/female agency.

The Gwangju Uprising of May 1980 marked a turning point in modern South Korean history. Heralding no less than the country’s transition from dictatorship to democracy, images played a crucial role in this critical moment of change, because footage of dead and wounded protesters showed the outside world the extent of the violent suppression of the democratisation movement. To better grasp the significance of Gwangju for Korean history, it is, however, important to ask not only what was going on but also how these events are remembered and represented to a broader public. In this vein, some scholars have interrogated the close relationship between Korean cinema and the country’s key historical events (e.g. Yecies & Shim, Citation2016; see also the Special Issue entitled “A Century of Korean Film: From ‘Joseon Film’ to Global Korean Cinema” in the Korea Journal in 2019).

Visualising Korea, which covers a broad range of different visual media formats, can open new avenues of research for the study of Korean culture, politics and society. Manhwa, Korean-style comic imagery, is a good example here. Instead of dismissing sketched visual art as apolitical, as in the case of entertainment, or as too political, as in the case of “propaganda comics”, re-thinking the peculiarities of this medium helps us to understand the complicity of comics in performing the political (see also Shim, Citation2017). Ideally, visualising Korea will provide scholars with an additional set of questions through which to better understand Korean affairs.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article have been presented at an authors’ workshop on “Visualising Korea” at the University of Queensland, at the Visual Studies Group colloquium of the Faculty of Arts, University of Groningen and at a seminar of the Institute of International Strategy, Tokyo International University. I would like to thank all participants for their feedback. In particular, I am grateful to Tomás Gaete Altamirano, Sandra Becker, Roland Bleiker, David Chapman and Julian Hanich for helpful comments on previous drafts.

Notes

1. According to the Korean Film Council (Citation2020), A Taxi Driver attracted more than 12 million viewers and generated about KW 96 billion [$83.3 million] in revenue. By way of comparison, May 18, another major film on the Uprising, attracted 6.8 million viewers and grossed about 44 billion won [$38.2 million].

2. In an insightful study, Andrew Jackson (Citation2020) pursues the question of why only Hinzpeter’s involvement in the Gwangju protests is remembered while the contributions of other overseas journalists to the democratisation movement have been mostly forgotten. Liora Sarfati and Bora Chung (2018) demonstrate the significance of symbolic imagery for the contentious politics of the so-called Sewol movement, a protest campaign that formed in reaction to the tragic sinking of the Sewol ferry in April 2014, in which more than 300 people died.

3. The original statement reads as follows: “Ajigkkaji gwangjuui jinsili da gyumyeongdoeji mothaetda. Igeoseun uriege nameun gwajeida. I yeonghwaga geu gwajereul puneun de keun himeul julgeotgatda. Ttohan gwangjuminjuhwaundongi neul gwangjue gadhyeoitdaneun saenggagi deuleotneunde, ijeneun gugmin sogeuro hwagsandoeneun geotgatda. Ireon geosi yeonghwaui keun himi anilkka saenggaghanda” (Blue House, Citation2017).

References

- Adams, A. (2016). Political torture in popular culture: The role of representations in the post-9/11 torture debate. Routledge.

- Ahn, J. (2002). The significance of settling the past of the December 12 Coup and the May 18 Gwangju Uprising. Korea Journal, 42(3), 112–138.

- Ahn, J. (2003). The socio-economic background of the Gwangju Uprising. New Political Science, 25(2), 159–176.

- Ahn, Y., & Lee, J. (2019). Narrative strategy in the film A Taxi Driver. Humanities Contents, 53(6), 283–303.

- Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso.

- Baker, D. (2003). Victims and heroes: Competing visions of May 18. In G. W. Shin & K. M. Hwang (Eds.), Kwangju: The May 18 Uprising in Korea’s past and present (pp. 87–107). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Birkenstein, J., Froula, A. & Randell, K. (Eds.). (2010). Reframing 9/11: Film, popular culture and the “war on terror”. Continuum.

- Blue House. (2017, 13 August). Yeonghwa “taegsiunjeonsa” gwanlam gwanlyeon gominjeong budaebyeonin seomyeonbeuliping [Briefing on the movie “A Taxi Driver”]. http://www1.president.go.kr/articles/466

- Brown, T. (2012). Breaking the fourth wall: Direct address in the cinema. Edinburgh University Press.

- Caso, F., & Hamilton, C. (2015). Popular culture and world politics: Theories, methods, pedagogies. E-International Relations.

- Cho, J. (2011, 24 May). UNESCO to list Gwangju Uprising records as world heritage. Korea Herald. http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20110524000557

- Choe, S. (2017, 2 August). In South Korea, an unsung hero of history gets his due. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/02/world/asia/south-korea-taxi-driver-film-gwangju.html

- Choi, H. (2017, 18 May). Moon vows probe of Gwangju Uprising. Korea Times. http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2017/05/356_229621.html

- Choi, J. (2006). The Gwangju Uprising: The pivotal democratic movement that changed the history of modern Korea. Homa & Sekey Books.

- Choi, K. (2016). Memorial in Gwangju for German journalist. JoongAng Daily. http://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/article.aspx?aid=3018263

- Choi, K., & Shin, K. (2016, 17 May). Journalist who filmed Gwangju deaths honored. JoongAng Daily. http://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/article.aspx?aid=3018769

- Daniel, J. F., & Musgrave, P. (2017). Synthetic experiences: How popular culture matters for images of international relations. International Studies Quarterly, 61(3), 503–516.

- Donga Ilbo. (2014, 2 January). Pro Roh-Moo-hyun faction must overcome movie “The Attorney”. Editorial. Donga Ilbo. http://english.donga.com/List/3/all/26/407602/1

- Fischer, A., Gillebaart, M., Rotteveel, M., Becker, D., & Vliek, M. (2012). Veiled emotions: The effect of covered faces on emotion perception and attitudes. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(3), 266–273.

- Ghosh, M. (2012). History, nation and memory in South Korean cinema: Lee Chang-dong’s Peppermint Candy. Asian Cinema, 23(2), 129–140.

- Grayson, K., Davies, M., & Philpott, S. (2009). Pop goes IR? Researching the popular culture–world politics continuum. Politics, 29(3), 155–163.

- Hong, Y. (2017, 10 October). “A Taxi Driver” pulled from Chinese theaters. http://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/article.aspx?aid=3039236

- Hwang, W. (2017). South Korea’s changing foreign policy: The impact of democratization and globalization. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Jackson, A. D. (2020). Jürgen Hinzpeter and foreign correspondents in the 1980 Kwangju Uprising. International Journal of Asian Studies, 17(1), 19–37.

- Jang, H. ( Director). (2017). A taxi driver. The Lamp.

- Kang, H. (2003). Women’s experiences in the Gwangju Uprising: Participation and exclusion. New Political Science, 25(2), 193–206.

- Katsiaficas, G., & Na, K. (Eds.). (2006). South Korean democracy: Legacy of the Gwangju Uprising. Routledge.

- Katsiaficas, G., & Rénique, G. (2012). A new stage of insurgencies: Latin American popular movements, the Gwangju Uprising and the Occupy Movement. Socialism and Democracy, 26(3), 14–34.

- Kil, S. (2017, 4 September). Korea hails “A Taxi Driver” for Oscar race. Variety. https://variety.com/2017/film/asia/korea-selects-a-taxi-driver-for-oscar-race–1202546725/

- Kim, C. H. (2008). Representation of the Kwangju Uprising – A Petal (1996) and May 18 (2007). Asian Cinema, 19(2), 240–255.

- Kim, E. H., & Choi, C. M. (Eds.). (1998). Dangerous women: Gender and Korean nationalism. Routledge.

- Kim, H. (2011). The commemoration of the Gwangju Uprising: Of the remnants in the nation states’ historical memory. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 12(4), 611–621.

- Kim, K. H. (2002). Post-trauma and historical remembrance in recent South Korean cinema: Reading Park Kwang-su’s “A Single Spark” (1995) and Chang Sŏn-u’s “A Petal” (1996). Cinema Journal, 41(4), 95–115.

- Kim, R. (2017, 14 August). Presidents’ choice of films shows political messages. Korea Times. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2017/08/356_234727.html

- Kim, S. Y. (2006). Do not include me in your “us”: Peppermint Candy and the politics of difference. Korea Journal, 46(1), 60–83.

- Kim, S. Y. (2010). Gendered trauma in Korean cinema: Peppermint Candy and My Own Breathing. New Cinemas, 8(3), 179–187.

- Kim, Y. (2003). The shadow of the Gwangju Uprising in the democratization of Korean politics. New Political Science, 25(2), 225–240.

- Kim, Y., & Han, S. (2003). The Gwangju people’s uprising and the construction of collective identity: A study on the Fighters’ Bulletin. New Political Science, 25(2), 207–223.

- Korean Film Council. (2020). Box office statistics. http://www.kobis.or.kr/kobis/business/stat/boxs/findFormerBoxOfficeList.do?loadEnd=0&searchType=search&sMultiMovieYn=N&sRepNationCd=K&sWideAreaCd=#

- Kret, M. E., & Fischer, A. (2018). Recognition of facial expressions is moderated by Islamic cues. Cognition and Emotion, 32(3), 623–631.

- Lee, A., & Chin, M. (2007). The women’s movement in South Korea. Social Science Quarterly, 88(5), 1205–1226.

- Light, A. (2001). Reel arguments. Lynne Rienner.

- Lisle, D. (2019). How do we find out what’s going on in the world? In J. Edkins & M. Zehfuss (Eds.), Global politics: A new introduction (pp. 147–169). Routledge.

- May 18 Memorial Foundation. (2011, 30 January). Memory of the world register. Human rights documentary heritage 1980. Archives for the May 18th democratic uprising against military regime. May 18 Memorial Foundation.

- Moeller, S. (1999). Compassion fatigue: How the media sell disease, famine, war and death. Routledge.

- Morris, M. (2010). New Korean cinema, Kwangju and the art of political violence. Japan Focus, 8(5), 1–20.

- Nam, S. (2017, 21 August). Exhibit of late German journalist begins in S. Korea. Yonhap. http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/culturesports/2017/08/21/0701000000AEN20170821009700315.html

- Neumann, I., & Nexon, D. (2006). Harry Potter and international relations. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Pautz, M. (2015). Argo and Zero Dark Thirty: Film, government and audiences. PS: Political Science & Politics, 48(1), 120–128.

- Pfützner, T. (2019, 24 April). Südkorea’s deutscher Held. Welt. https://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/plus192118445/Suedkorea-Der-Kameramann-Juergen-Hinzpeter-wird-als-Held-gefeiert.html

- Postman, N. (1987). Amusing ourselves to death: Public discourse in the age of show business. Methuen.

- Power, M., & Crampton, A. (2005). Reel geopolitics: Cinemato-graphing political space. Geopolitics, 10(2), 193–203.

- Rhee, J. (2019). Beyond victims and heroes: The 5.18 cinema across gender boundary: Introduction: The problem of representing historical trauma in cultural productions. Korean Studies, 43(1), 68–95.

- Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

- Sarfati, L., & Chung, B. (2018). Affective protest symbols: Public dissent in the mass commemoration of the Sewŏl ferry’s victims in Seoul. Asian Studies Review, 42(4), 565–585.

- Schlag, G. (2019). Representing torture in Zero Dark Thirty (2012): Popular culture as a site of norm contestation. Media, War & Conflict. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1750635219864023

- Schwartz-Shea, P., & Yanow, D. (2012). Interpretive research design: Concepts and processes. Routledge.

- Shapiro, I. (2002). Problems, methods and theories in the study of politics, or what’s wrong with political science and what to do about it. Political Theory, 30(4), 596–619.

- Shim, D. (2017). Sketching geopolitics: Comics and the case of the Cheonan sinking. International Political Sociology, 11(4), 398–417.

- Shim, D., & Flamm, P. (2013). Rising South Korea: A minor player or a regional power? Pacific Focus, 28(3), 384–410.

- Shin, G. (2003). Introduction. In G. Shin & K. Hwang (Eds.), Contentious Kwangju: The May 18 Uprising in Korea’s past and present (pp. 10–25). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Shin, G., & Hwang, K. (Eds.). (2003). Contentious Kwangju: The May 18 Uprising in Korea’s past and present. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Shin, Y. (2014). Protest politics and the democratization of South Korea: Strategies and roles of women. Lexington Books.

- Stam, R. (1992). Reflexivity in film and culture: From Don Quixote to Jean-Luc Godard. Columbia University Press

- The Economist. (2016, 27 October). A shrimp among whales. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/asia/2016/10/27/a-shrimp-among-whales

- Weldes, J. (1999). Going cultural: Star Trek, state action and popular culture. Millennium, 28(1), 117–134.

- Westwell, G. (2014). Parallel lines: Post-9/11 American cinema. Columbia University Press.

- White House. (2017). Joint press release by the United States of America and the Republic of Korea. United States Government. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/joint-press-release-united-states-america-republic-korea/

- Yecies, B., & Shim, A. (2016). The changing face of Korean cinema: 1960 to 2015. Routledge.

- Yuval-Davis, N. (1997). Gender and nation. Sage Publications.