ABSTRACT

While the number of elected Indigenous representatives has increased over the past two decades, we know little about their pathways to candidature, which parties they stand for, the winnability of seats they stand in, and whether they are successful. Using election data from 2001 to 2021, and interviews with 50 (or 80%) of all Indigenous candidates between 2010 and 2019, this study provides answers to these questions. It finds, first, that Indigenous candidates are usually winners, as 53.2% of candidatures have resulted in an election victory. Second, most candidates are from the ALP and Indigenous women tend to do better than men. Third, despite some high-profile ‘parachutes’, most Indigenous candidates are ‘partisans’ (i.e. party members for at least a year before standing).

While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders remain under-represented, their presence has increased in Australia’s legislative institutions over the first two decades of the twenty-first century. After the 2001 Federal Election, there were no Indigenous members in the House of Representatives, there was one in the Senate, and there were five in state and territory parliaments/assemblies.Footnote1 Twenty years later, in 2021, there were two Indigenous members in the House of Representatives, four in the Senate, and 14 in state and territory parliaments. Beyond observing that Indigenous representation has risen, however, we lack basic nationwide data about: (1) the numbers of Indigenous candidatures put forward by the major parties; (2) the electorates in which these have occurred; (3) the success rates.Footnote2 Moreover, we have little idea about how Indigenous candidates have come to contest elections for the major parties in the first place. In this article, we, therefore, ask: What are the trends in Indigenous candidatures as regards location, party affiliation, winnability of seats, and success rates? How do Indigenous people become candidates in Australia’s major parties?

As Kittilson and Tate (Citation2004, 1) argue, ‘the numerical representation of minorities in legislatures is important to the quality of the democratic process and an important aspect of democratic inclusion’. Amongst the many benefits is that it may reduce historical patterns of domination and subordination since these representatives can speak on issues ‘with a voice carrying the authority of experience’ (Mansbridge Citation1999, 644). Likewise, Hazan and Rahat (Citation2010, 3) explain that who is chosen to contest elections ‘influences the balance of power within the party, determines the personal composition of parliaments, and impacts on the behavior of legislators. In short, it is central to politics in any representative democracy’. The same authors note, however, that researchers seeking to understand these processes even in one country ‘will need months of fieldwork and access to data that is either not public or perhaps even unavailable’ (Hazan and Rahat Citation2010, 7). This is precisely what we have done and more. In addition to gathering previously lacking election data covering two decades, we have also interviewed 50 (or 80%) of all 62 successful and unsuccessful Indigenous candidates between 2010 and 2019 at federal, state and territory levels for the Australian Labor Party (ALP), Liberal Party (LP), and Country Liberal Party (CLP). We thus provide the most complete picture to date of Indigenous candidatures in Australia.

The article proceeds as follows. In the next section, we explain the background to our study, setting out some of our expectations regarding Indigenous candidatures and discussing two likely pathways to candidature, the ‘partisan’ and the ‘parachute’. In our first results section, we present quantitative data on Indigenous candidates at all state, territory, and federal elections since 2001. We find that Indigenous candidates were put forward by the major parties on 143 occasions between February 2001 and May 2021, with over 70% of these from the ALP. Overall, almost two-thirds of Labor Indigenous candidatures resulted in an election victory, compared to just under one-third of Liberal and Country Liberal candidatures. While those results were in line with our expectations, what was more surprising was to find, firstly, that Indigenous women and men both tend to stand in winnable seats and, secondly, that women win significantly more than men. Based on our interviews, we then examine how Indigenous candidatures have occurred. We find that the majority of candidates (around two-thirds) have been what we term ‘partisans’ – grassroots party members for at least a year before standing – rather than candidates who were ‘parachuted’ into contests. In the final section, we consider the implications of our findings and propose avenues for future research.

Investigating Indigenous candidatures

This study seeks to uncover trends in Indigenous candidatures as regards location, party affiliation, winnability of seats, and success rates, in addition to understanding how Indigenous people become candidates in Australia’s major parties. While we do not have any previous studies focusing on Indigenous candidates in Australia, research on ethnic minority and women candidates may provide some insights into what we might find, given that these groups have also long been under-represented in Western democracies. Specifically, we can investigate whether Indigenous candidatures follow some of the same international trends that have been witnessed in relation to candidatures of ethnic minorities and women. These trends concern the tendency of left-wing parties to put forward more ethnic minority candidates and women than right-wing ones (Sobolewska Citation2013; Kittilson Citation2006); the pattern of (usually left-wing) parties that have quotas for both women and ethnic minorities consequently fielding more women ethnic minority candidates (Hughes Citation2011; Celis and Erzeel Citation2017); the habit of parties, especially of the right (but not only), to place women and ethnic minorities disproportionately in unwinnable seats (Caul Citation2001; Kulich, Ryan, and Haslam Citation2014); and the practice of parties to parachute ethnic minority candidates into electoral contests in order to increase diversity among their representatives (Koop and Bittner Citation2011). At the same time, however, we do wish to emphasise that we are not conflating Indigenous representation with that of ethnic minority groups. On the contrary, we agree with Williams and Schertzer (Citation2019, 679) that ‘Indigeneity is distinct from ethnicity, defined by unique representational needs that stem from Indigenous peoples’ relation to the colonial nationstate Project’. As such, our findings speak to research on minority group candidate selection and representation in Western democracies, but also make a distinct contribution to the separate question of Indigenous representation.

Following on from the discussion above, our first expectation concerns the number of Indigenous candidates fielded by the major parties. While we know that left-wing parties in Western democracies tend to present more ethnic minority candidates than right-wing ones do (Sobolewska Citation2013; Van der Zwan, Lubbers, and Eisinga Citation2019), the opposite has been the case in Australia at Federal level for the House of Representatives (HoR). As Farrer and Zingher (Citation2018, 475) note, the Liberals fielded more ethnic minority candidates than Labor at both the 2007 and 2010 HoR elections. Snagovsky (Citation2019, 86) shows how this trend has continued, with the Liberals consistently putting forward more ethnic minority candidates than Labor at the 2013, 2016, and 2019 elections. At the same time, however, there are also reasons to think that the ALP may select more Indigenous candidates than the Liberals. Just as it has for women across the country (Beauregard Citation2018), the ALP has introduced Indigenous quotas of variously binding degrees in three of the four largest states, Queensland, New South Wales, and Western Australia.Footnote3 By contrast, none of the country’s Liberal and CLP branches have brought in similar measures either for women or Indigenous candidates.Footnote4 Notwithstanding the Liberals’ better record on promoting ethnic minority candidates, we, therefore, envisage that Labor will put forward more Indigenous candidates than the Liberals and Country Liberals.

Our second set of expectations concerns whether the major parties select more Indigenous men or women. In some European countries, such as the Netherlands and Belgium, there is a greater representation of women than men from ethnic minorities (Mugge Citation2016). One supply-side explanation for this is, as Celis and Erzeel (Citation2017, 56) find in the case of Belgium, that parties believe ‘ethnic minority women would be better able to represent the diversity label without alienating the traditional voters of the party’, rather than ethnic minority men, whom parties think will be perceived as more threatening by voters. In the case of Australia, there are specific reasons why the ALP might field more Indigenous women than men but the Liberals would not. Firstly, the ALP’s use of ‘tandem quotas’ (Hughes Citation2011) in some states for both women and Indigenous candidates makes it especially plausible that it will seek to fulfil two quotas/aspirations with one candidate.Footnote5 Secondly, we know that the Liberals and Country Liberals do not use quotas for women or Indigenous candidates and, like right-wing parties generally, have tended to promote women’s participation less than left-wing ones (Kittilson Citation2006). Consequently, as Martinez i Coma and McDonnell (Citation2021) have recently shown, Labor has put forward a greater share of women candidates than the Liberals at every House of Representatives election since 2001. Moreover, if we look at the HoR elections in 2013, 2016, and 2019, we find that, although the Liberals selected more ethnic minority candidates overall, the ALP selected more women ethnic minority candidates (9) over that period than the Liberals (5).Footnote6 We, therefore, expect that Labor will field more Indigenous women than men, but that the Liberals and Country Liberals will field more Indigenous men than women.

Our third expectation regards the competiveness of the seats in which Indigenous candidates will be fielded. Even parties of the left which claim a strong commitment to diversity may ‘box tick’ by selecting candidates from under-represented groups for seats they have little chance of winning. Within the context of women candidates, Caul (Citation2001, 1226) has referred to this approach as ‘more a symbolic gesture and less a reflection of real support for women’. International research has shown that the practice (known as the ‘sacrificial lamb’ hypothesis) is widespread. For example, Thomas and Bodet (Citation2013) demonstrated that – irrespective of their ideology – Canadian parties disproportionately nominated women in other parties’ strongholds. Likewise, Murray, Krook, and Opello (Citation2012) show that women candidates in France are selected by both left-wing and right-wing parties in the most challenging districts, whereas men are more likely to be placed in safe seats. In the case of Australia, Martinez i Coma and McDonnell (Citation2021, 14) recently found that ‘women continue to be disproportionately chosen for unsafe seats by the major centre-left and centre-right forces’. The same ‘sacrificial lamb’ mechanism has been found in the case of ethnic minority candidates, with Kulich, Ryan, and Haslam (Citation2014) showing how the lesser success of non-white candidates in UK elections was due in particular to the low winnability of seats that non-white Conservative Party candidates contested. Based on the above, we, therefore, expect that the Liberals and the CLP, and to a lesser extent Labor, will tend to put Indigenous candidates disproportionately in unwinnable seats.

Finally, we are interested in the pathways by which Indigenous candidates come to be selected. The first possible pathway is what we call the ‘Partisan’ route to candidature: by this, we mean that someone serves as a grassroots party member for at least a year and then runs as a candidate upon securing the endorsement of their local branch. Parties in different Australian states and territories all vary in their rules regarding candidate selection (Cross and Gauja Citation2014, 24), but a standard condition is for aspirant candidates to have been active grassroots members for a set period of time (Gauja and Taflaga Citation2020, 74–75). In most cases, the chosen candidate will be agreed in advance of the formal pre-selection by any relevant factions and party officials, so they will likely not face a contested pre-selection process (Gauja and Taflaga Citation2020).Footnote7 While it has the advantage of allowing party officials and members the possibility of getting to know the potential candidate, the ‘partisan’ strategy necessitates time and resources. As such, it may not be able to produce a major change in the short-term for party leaderships that are eager to diversify their candidates and representatives.

An alternative for the party leadership is to ‘parachute in’ people from under-represented groups and impose them as candidates, whatever the local branches, elites and factions think. For Koop and Bittner (Citation2011, 432), ‘parachuting in’ refers to when the central leadership chooses a candidate who ‘can bypass local nomination races and therefore run under the party banner without winning the consent or support of local party members’. Footnote8 As Hazan and Rahat (Citation2006, 115) observe, when candidate selection is controlled by a small group among the central leadership, which likely has broader party-wide goals than local elites, ‘there are more chances that different ideological and social groups (women, minorities, etc.) within the party will be allocated safe positions on the party list, or safe constituency seats’. This approach has been used by the centre-left Liberal Party in Canada to improve diversity, although not equally for all under-represented groups. Interestingly, given our purposes in this study, Koop and Bittner (Citation2011) found that the Canadian Liberal leadership had employed this strategy to increase the number of women and immigrants being nominated but not Indigenous citizens. In Australia, the option is enabled by the fact that, while each state and territory branch of the major parties has rules about eligibility to stand, they can override these ‘where it may be electorally desirable to do so’ (Gauja and Taflaga Citation2020, 75). Nonetheless, as Cross and Gauja (Citation2014, 26) found in their interviews with Australian party elites, ‘the central party leadership has a finite amount of political capital and spends some of it each time it intervenes in a pre-selection contest. Thus, it does so hesitantly and only in exceptional cases’. Whether increasing Indigenous representation through parachute candidatures (or, what in Australian political vocabulary, are known as ‘captain’s picks’) is an ‘exceptional case’ on which party leaderships are willing to regularly spend political capital is, therefore, an open question which our study seeks to answer.

Indigenous candidatures in Australia, 2001–2021

In order to investigate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander candidatures between 2001 and 2021, we first conducted extensive background research using multiple sources. These included: extant scholarly and grey literature; federal, state, and electoral commission data; parliamentary websites; party websites; candidate webpages; candidate social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram); media reports.Footnote9

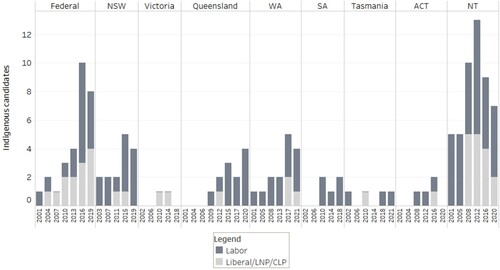

As shows, between 2001 and 2021, Indigenous candidates were chosen by the major parties on 31 occasions at federal level and on 112 at state and territory elections (this includes Indigenous candidates who have stood more than once). At the Federal level, 19 candidatures (61%) were for the House of Representatives and 12 (39%) for the Senate. Overall, and firmly in line with our first expectation, the ALP put forward Indigenous candidates a total of 102 times, well over double the combined 41 of the Liberal Party and the Country Liberals.

Table 1. Indigenous candidatures in Federal, State and Territory elections, 2001–2021, by party (n).

In order to understand the extent to which the quantity of Indigenous candidatures differs across the country by party and institutional levels, in addition to over time, we also looked at the distribution of these between 2001 and 2021. As we can see, from , at federal elections, the number rose over the period, but not in a linear fashion, with 2016 seeing a high of 10 candidatures, before falling back to 8 in 2019. Unsurprisingly, given that it accounts for the largest percentage of Indigenous citizens among Australian states and territories, the Northern Territory had the largest amount of candidatures overall (49), while Victoria had the lowest (2). We can also see the growth of candidatures over time. Notably, the three states in which the ALP introduced quotas or aspirations regarding Indigenous candidates – NSW, QLD and WA – all show an evident increase. By contrast, in the Northern Territory, where the ALP has no such quota system, the total number of Indigenous candidatures has declined over the last two territory elections in 2016 and 2020 (this is also due to the CLP standing fewer candidates at each election since 2012).

Figure 1. Indigenous candidatures, by year and jurisdiction, 2001–2021. Note: The data in this figure do not include by-elections. Indigenous people in 2021 represented 3.3% of the total Australian population (AIHW Citation2021). The estimated Indigenous populations in the states and territories were: NSW 3.5%, VIC 0.9%, QLD 4.7%, WA 4.1%, SA 2.6%, TAS 5.8%, ACT 1.9%, NT 30.9%. For specific data on the Indigenous populations in the various jurisdictions at the time of each election, see in the Appendix. also includes data on Indigenous candidatures as proportions of the total number fielded by the parties at each election. in the Appendix provides information on the numbers and percentages of Indigenous candidates who stood in majoritarian and proportional elections.

Moving on to our second set of expectations, regarding the respective numbers of Indigenous women and men the major parties put forward as candidates, again our results are as envisaged. As details, the ALP has stood Indigenous women on 53 occasions and Indigenous men on 49. By contrast, the Liberals and CLP have put forward Indigenous men 33 times and Indigenous women just 8.Footnote10

Table 2. Indigenous candidatures in Federal, State & Territory elections, 2001–2021, by gender (n).

While our first two sets of expectations are therefore confirmed, the result relevant to our third – concerning the winnability of seats with Indigenous candidatures – presents a more mixed picture. In fact, as shows, 62.6% of Indigenous candidatures have been in winnable seats (with ‘winnable’ taken as there being no more than a 5 percentage point difference in votes received, following the distribution of preferences, between the top two candidates at the previous election).Footnote11 This overall percentage masks significant differences between the parties, however, as the respective figures are 70.9% for the ALP and 44.4% for the LP and CLP combined. If we apply a more elastic ‘winnable seat’ measure of 10 percentage point difference in the previous election’s two-party-preferred vote, the gap between the parties remains as 83.5% of the ALP’s Indigenous candidatures and 55.5% of those by the LP and CLP were in winnable seats. Notwithstanding these inter-party differences, we can say that Indigenous candidates tend to run in races that they have a chance of winning. Finally, in terms of gender differences, 73% of ALP candidatures of Indigenous men and 69.1% of the party’s candidatures of Indigenous women were in winnable seats (taken at the 5 percentage point threshold), while the corresponding LP and CLP figures are 48.4% for men and 20% for women (although we need to bear in mind that the number of the latter is very small). As shows, however, these proportions rise notably for the LP and CLP if we define ‘winnable’ using the 10% benchmark.

Table 3. Indigenous candidatures in winnable seats (5 and 10%), by party and gender (% and N).

Finally, we look at the success rates of Indigenous candidatures between 2001 and 2021 (). We find that 53.2% of these have resulted in an election victory. Breaking it down by party, we see that 61.6% of ALP Indigenous candidatures have produced a winner, while 32.5% of LP/CLP ones have done likewise. Interestingly, and despite the fact that there was only a small difference in the numbers of Indigenous men and women fielded by the ALP in winnable seats (at the 5% threshold), we instead find a noticeable gap in their respective success rates: 69.2% of ALP Indigenous women candidatures have gone on to win the seat, compared to 53.2% of ALP Indigenous men ones. Similarly, in the LP/CLP, where we had found a considerable gender gap in favour of men, we observe that 42.9% of Indigenous women were successful, compared to 30.3% of Indigenous men.

Table 4. Indigenous candidate success rates, 2001–2021, by party and gender (% and N).

Parachute and partisan Indigenous candidates

The previous section provided information about who the Indigenous candidates to stand for Australia’s major parties were between 2001 and 2021, where they did so and to what degree they were successful. We now examine how they became candidates and whether, following our earlier discussion, they followed the partisan or parachute routes to candidature. As showed, most Indigenous candidatures have occurred since 2010. For this reason – and also due to the feasibility of contacting candidates from over a decade ago – we focused our fieldwork on those who stood for the ALP, the Liberals and the CLP between 2010 and 2019 (irrespective of whether it was the first time standing or not).Footnote12 In that period, we counted 62 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander candidates at state, territory and federal levels for these three parties. Between August 2017 and June 2020, we were able to interview 50 of these. For our purposes in this study, we coded each interviewee as ‘parachute’ or ‘partisan’ according to the length of time they told us had passed between joining the party and being selected for the first time as a candidate (further information about our data collection can be found in the Appendix). Specifically, we consider as partisan candidates those who had been party members for at least one year, while parachutes are those who, at the time of first standing, had been in the party for less than one year. Our reasoning for this threshold is twofold. Firstly, those in the party for a year or more have demonstrated a degree of lasting partisan commitment by renewing their annual membership at least once. Secondly, parties usually have rules about how long one must have been a member before being able to nominate as a candidate. While these vary across states and party divisions, one year is a common milestone. For example, WA Labor (Citation2019, 47) and VIC Liberals (2019: 50) both stipulate in their rules that anyone nominating for a seat must have been a member for the full 12 months previously. Likewise, they also set out how this 12-month requirement may be relaxed for a parachute candidate.Footnote13

We present details of our interviewees in of the Appendix, so limit ourselves in the text below to noting the dates that cited interviews took place.

Parachutes

16 of the 50 candidates we interviewed were parachute candidates the first time they stood for election. 13 of these were from Labor, 2 from the Liberals, and 1 from the Country Liberal Party. Of these, 9 were men and 7 were women. While some of the more prominent parachute candidates such as Patrick Dodson and Nova Peris were hand-picked for effectively guaranteed seats, over half of the parachutes (9) we spoke to were unsuccessful the initial time they ran.Footnote14 That said, we should acknowledge that we also heard in interviews about other successful candidates whom we were not able to speak to but who had clearly been parachutes (for example, Larisa Lee and Francis Xavier Kurrupuwu of the CLP in 2012).Footnote15 It is also worth noting that, on only one occasion that we know of, a defeated parachute remained in the party and was later elected. This is the case of Adam Giles, who first ran as a parachute in the ACT for the Liberal Party in 2004, but then as a ‘partisan’ for the CLP in the NT seat of Braitling in 2008, eventually becoming chief minister in 2013.

We found three main ways that parachute candidatures can occur. From our interviews with those who had stood for the ALP, the main trigger for a parachute candidature in that party was the ‘tap on the shoulder’ from senior party figures. A good example is the former Olympian Nova Peris, who was a ‘captain’s pick’ by Julia Gillard to serve as the ALP’s no. 1 Senate candidate for the NT at the 2013 Federal election.Footnote16 Although she had had a prior conversation about going into politics with the party in 2004, Peris had decided not to pursue the possibility. She also had never been a member of the ALP. As she recounted in her interview with us, she received a phone call in November 2012 from an acquaintance, Tim Barnett, of the New Zealand Labour Party, to say he had heard the ALP had emailed her to see if she might be interested. When she found the mail in her spam folder, it was from a senior party figure asking to talk. Eventually, this led to her being invited to the Lodge to meet prime minister Julia Gillard. As Peris put it, it’s hard to say no ‘when a prime minister taps you on the shoulder and says, “Will you serve?” … ’ (18/6/18). Moreover, as she explained: ‘it was sort of put to me in a way that the bus wasn’t going to stop twice, meaning the bus stopped and you chose not to get on it in 2004 and the Labor Party wanted an Aboriginal person in federal parliament’.

The choice of Senator Pat Dodson (ALP – Western Australia) also came from the top. Like Peris, he had been approached about standing in the early 2000s, with the ALP leader at the time, Kim Beazley, seeking to convince him. Dodson decided not to accept the offer but, over a decade later, the then leader ‘Bill Shorten rang me and asked whether I’d be interested in filling the vacancy, which means you get a free ride into the parliament’ (11/2/19). Again, like Peris, Dodson had never been a party member before he was approached. This was because, as he explained, ‘I’ve always been an advocate outside of the parliamentary party machines and tried to be even-handed in my dealings with the parties’. He told us he said ‘yes’ to Shorten in 2016 because he had concluded that, otherwise, it was hard to get ‘traction inside parties or inside the parliament’ for the issues he cared about. While Dodson and Peris were nationally high-profile figures, similar ‘taps on the shoulder’ have occurred at other levels. For example, Lawrence Costa (ALP member for Arafura in the NT) was encouraged to stand by the former Minister in the Territory government, Jack Ah Kit, who also told him that the previous member for Arafura, Maurice Rioli, had ‘seen me as a future leader or rep, so that really made me think that now might be the right time to get involved in politics and all that stuff’ (16/8/17).

Not all ALP parachute candidates, however, have been picked for winnable seats. Others have been chosen (at least in part) to enable Labor to fulfil its Indigenous candidate quotas in states which have adopted them. This appears to be the case, for example, of Beau Riley in the seat of Bathurst at the 2019 NSW state election. Riley, a police prosecutor, met the Secretary of the NSW Labor Party and began a whirlwind process of becoming a candidate. He explained to us that ‘I said to them, you know, ‘I know nothing about politics.’ I honestly know nothing … I’m not diplomatic. I said, ‘You don’t want me. I’m having fun locking up crooks right now.' And they said, ‘No, you’re our bloke’ (1/2/19). Nominated seven months before the election, Riley was selected unopposed to contest a seat that the ALP had lost by just under 32 points in 2015. He would lose in 2019 by an even larger margin, 68–32, in an election the party put few resources into. Moreover, for unsuccessful parachute candidates, the tumultuous experience of being swiftly thrust into a campaign for which they have had little preparation, and then losing, can often be compounded by never hearing from the party again after the election (as several defeated ALP parachute candidates told us had happened to them).

A second pathway for parachute candidates is when parties ask Indigenous communities and organisations to propose someone (especially in electorates where parties think that having an Indigenous candidate will help them win). For Josie Farrer in the Kimberley, rather than the ALP running the preselection process, it was a community event of public endorsement that led to her standing at the 2013 Western Australia state election. Farrer was approached by party officials and community members during the 2012 Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Cultural Festival, and the next day ‘they said, “If you want to vote for Josie, stand behind her. If you want to vote for this other person, stand there.”’ (14/2/18). Those present lined up behind Farrer in much greater numbers and she was thus pre-selected. The selection by the CLP of Francis Xavier Kurrupuwu for the seat of Arafura at the 2012 NT election also had community involvement. As Adam Giles explained to us: ‘Because I had a pretty good relationship with the Tiwi Land Council, I said to them, “Who is a good person?” So they helped find the candidate for us’ (19/6/18). While the ALP and CLP both seem to have worked with local Indigenous community groups and leaders to find candidates, no Liberal Party interviewees mentioned this.

Finally, a third route is when a candidate approaches the party with a view to standing or joins the party and then swiftly puts themselves forward. This was what Bess Price (former CLP member for Stuart) did prior to the 2012 NT election. Although she had been a Labor voter all her life, she concluded that

they weren’t doing anything for our people … So I decided, no, I’ll put my hand up and throw my hat in and see what happens, but with Country Liberals. And they embraced me and said, ‘Yeah, we’re very happy to have you, Bess.’ (26/4/18).

Partisans

While the parachute strategy has been a significant feature of Indigenous candidatures over the last decade, it was the less common route among those we interviewed. Instead, the majority were ‘partisans’. The 34 partisan candidates we spoke to comprised 23 from the ALP, 10 from the Liberal Party and 1 from the CLP. 20 of the candidates were men and 14 women. 15 of the 34 partisan candidatures resulted in a successful first election: 12 ALP and 3 Liberal.Footnote17 A further four partisans, all from the ALP, won a subsequent election.

Partisan Indigenous candidates present several differences to parachute ones. The first derives from the fact that they have had a longer history in the party and have not simply joined to stand for election. In contrast, therefore, to unsuccessful parachute candidates (whose experience with the party is usually short and not particularly sweet), for partisans an initial defeat may instead be part of their long-term commitment to the party and is a steppingstone towards an eventual representative career. Partisans may therefore first run in an election they know they are highly unlikely to win so they can gain experience for future candidatures in more winnable seats. This was the case of Ken Vowles (ALP) when he stood at the 2008 NT election. As he explained, party officials told him: ‘You know, we’ve got a seat we’ve love to put you in, but you’re probably not going to win it, but long term, if you want to have a career in politics … ’ (3/5/18). While Vowles lost in 2008, he ran in a far more winnable electorate in 2012 and was elected. We counted three other ALP partisans who lost their first election but then won later (Leanne Enoch and Billy Gordon, both for the ALP in Queensland, and Chris Bourke for the ALP in the ACT).Footnote18

This is not the case for all partisans, however. Warren Mundine is one notable example of an Indigenous partisan who put his hand up many times to run for the ALP and was placed in an unwinnable senate spot or lost at pre-selection. As he told us, he saw standing in the Nationals’ stronghold of Dubbo at the 1999 NSW state election as doing a service to the party and acquiring experience. ALP officials told him: ‘“Okay, tough guy, run a really tough campaign and we’ll get the independent elected.” So, my job was to have fun, was to destroy the National Party guy and that’s what I did’ (16/1/19). While Mundine had no chance of winning the election, his performance helped an Independent take the seat from the Nationals and he was able to develop his profile inside the party, but never achieved office.Footnote19

A second feature of partisans is that, unlike parachutes, they can rely on support they have built up within the party over time. This often smoothes their path to candidature and ensures backing during the campaign. For example, Chansey Paech (ALP) had been a party member for 9 years before standing at the NT election in 2016. During this time, he had assisted with campaigns for other candidates, had been both secretary and president of the Alice Springs ALP branch, and had been involved with Young Labor. As a result, when he decided to run, ‘everyone knew I was putting my hand up for Namatjira. I went through uncontested there, my branch, and then went to electoral college and went to admin’ (16/8/17). Paech’s former Alice Springs town council colleague, Jacinta Price of the CLP, similarly had many years of party involvement before standing for the seat of Lingiari at the 2019 Federal election. Having joined when her mother, Bess Price, ran in 2012 (as discussed above), she created strong networks both at territory level within the CLP and nationally within the Liberals. As Jacinta Price told us, this enabled her to forge links with senior figures like the former prime minister, Tony Abbott, and receive support for her campaign from donors (25/4/18). Like Paech, she was chosen unopposed to run in her first election in 2019, which she lost, but was subsequently pre-selected in 2021 as the CLP’s number one candidate for the next Senate election.Footnote20

Partisans are also usually able to access strong mentoring within the party, which can help them navigate the route to candidature. For example, Leanne Enoch (ALP) in Queensland told us how, in addition to her involvement with the Queensland Indigenous Labor Network (QILN) for some years, when she decided to run at the 2015 state election, senior party mentors ‘guided me through all these processes’ (16/1/20). Another to benefit from a long period of mentoring was Karl Hampton (ALP), who was identified by the sitting (non-Indigenous) ALP member for Stuart in the NT, Peter Toyne, as the best person to follow in his footsteps. As Hampton told us, prior to standing and winning in 2006, he spent a ‘six to seven years apprenticeship learning about Labor, learning about running an electorate office, running election campaigns, that sort of stuff’ (27/4/18). Linda Burney, who had been an ALP member since 1986, likewise benefited from strong mentorship when she decided to challenge the sitting Labor member for the very safe seat of Canterbury at the 2003 NSW state election. Moreover, as she explained, knowing how the party worked (unlike some of the parachute candidatures we have discussed), she insisted on there being ‘a rank and file preselection’ so she would ‘not be imposed’ by the party elites (14/2/19). She duly spent months visiting the branches of the electorate and convincing grassroots members she was the best choice. This capacity to win over grassroots members is something else that partisans are likely to be better equipped for than parachute candidates, as we can also see in the case of the Liberal Party’s Ken Wyatt. A long-standing member of the Liberals, Wyatt was encouraged by several grassroots members to contest a pre-selection against five other candidates for the federal seat of Hasluck (WA). He duly put himself forward, securing the majority of votes in the pre-selection, and then becoming the first Indigenous member of the House of Representatives in 2010.

Conclusion

While we know that the number of Indigenous representatives at different institutional levels across Australia has grown since the early 2000s, until now we had little idea where they stood, for whom, with what success rates, and how they became candidates in the first place. In this article, we have provided some first answers to these questions. As we detailed, there were 143 Indigenous candidatures by the major Australian parties between 2001 and 2021. Of these, 71% were by the ALP. Thus, although the Liberals in Australia have selected more ethnic minority candidates for House of Representatives elections than Labor since 2007 (Farrer and Zingher Citation2018, 475; Snagovsky Citation2019, 86), Labor has been the greater promoter of Indigenous candidates at all institutional levels over the same period. Likewise, and in line with studies showing that left-wing parties both internationally and in Australia are more inclined to promote women candidates (Kittilson Citation2006; Martinez i Coma and McDonnell Citation2021), the ALP has put forward over five times as many Indigenous women as the Liberals and the CLP. In fact, and reflecting its ‘tandem quotas’ in some states for women and Indigenous candidates, Labor has stood more Indigenous women than Indigenous men (while the Liberals and CLP have fielded over three times as many Indigenous men as women). As we noted, this practice by the ALP aligns with previous findings about the propensity of parties to promote more ethnic minority women than men (Celis and Erzeel Citation2017). If the above findings were not overly surprising, what was striking is that the ‘sacrificial lamb’ hypothesis that affects both women and ethnic minorities in many countries does not seem to be in play since Indigenous candidates generally stand in seats they can win. However, while Indigenous men and women run in approximately equal measures in winnable seats, Indigenous women have a much higher success rate than men (66.1% to 43.8).Footnote21 Finally, Indigenous candidates are usually winners, as 53.2% of Indigenous candidatures have in fact resulted in an election victory.

To dig deeper into the pathways to candidature, we then presented the findings of our interviews with 50 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander candidates from the 2010–2019 period. Similar to what Koop and Bittner (Citation2011) found for the Canadian Liberal Party, around two-thirds of the Indigenous candidates we spoke to were what we have termed ‘partisans’, and the remainder were ‘parachutes’. Amongst the latter, we discussed how their routes to candidature consisted mainly of ‘taps on the shoulder’ by senior party figures or the involvement of Indigenous organisations in their selection. In the case of partisans, we observed how their longer experience in the parties – and the mentoring and other advantages this gave them – had helped candidates navigate some of the challenges of standing for election.Footnote22 Overall, of the 34 partisans we spoke to, 19 eventually achieved office: 15 at the first time of asking, and a further four at a later election. Of the 16 parachutes, 8 made it into parliament at some point: 7 when they initially stood and 1 four years later.

There are several areas of future research that could build on our study. One concerns the logics underpinning the decisions of parties to choose Indigenous candidates. Tentatively, from our work over the past few years, we believe there are at least three. The first logic is normative and concerns only the ALP: simply put, the national party leadership believes it must increase the visibility and presence of Indigenous people among its representatives, if necessary with parachute candidates. The selections of Nova Peris and Pat Dodson, for example, seem to respond to this. The second logic is pragmatic: especially in parts of the Northern Territory and Western Australia, parties believe that choosing an Indigenous candidate will increase their chances of winning. This logic is present in both major parties. For example, in the NT seat of Arafura, both the ALP and CLP have fielded Indigenous candidates at the last three elections.Footnote23 The third logic is what, for want of a better term, we might call ‘standard’. This is when parties are not driven primarily by normative or pragmatic strategies and the chosen candidate is simply the one that fits the bill for their election strategy. This is the case, for example, of the Liberal Ken Wyatt in Western Australia.

Another important area of further research would be to go beyond our focus on candidates and look at Indigenous grassroots party members. In our experience, Australian parties are very reluctant to divulge any information about their membership numbers and even more so to give precise figures about how many Indigenous grassroots members they have.Footnote24 This may be for good reason. When asked if he had come across other Aboriginal members during his time in the Liberal Party, Ken Wyatt told us that ‘If I looked across all the branches, I doubt that the coalition would have too many Indigenous people as members. You’d probably be able to count them on one hand’ (14/2/19). While the ALP may do better in this respect, our interviews on the ground in many electorates suggest that the party has difficulties fostering active participation among its Indigenous members. Finally, future survey research might examine why – as suggested by our findings – voters indeed favour Indigenous women candidates over male ones, even though they both stand in similar percentages of winnable seats. While our work has begun to unpack the supply-side explanations of Indigenous candidatures, the demand side of Indigenous electoral success remains unexplored. Understanding both is crucial if we are to fully understand how and why Indigenous citizens enter Australia’s legislative institutions.

Acknowledgements

We extend our thanks and respect to the 50 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander former candidates who agreed to be interviewed for this article. We owe an immense debt of gratitude to Josh Holloway, who gathered the election data for this article, and to Poppy de Souza and Bartholomew Stanford, who conducted some of the interviews with us. In addition, Josh and Bartholomew commented on the draft manuscript, as did our colleagues Sofia Ammassari, Ferran Martinez i Coma, and Pan Petter. We thank them all for their valuable insights. Thanks also to the journal's editors and reviewers for their constructive criticism. We acknowledge Wurundjeri, Wiradjuri, Jagera, and Turrbal People and Countries on which we live and work, their ancestors, elders and knowledges.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michelle Evans

Michelle Evans is Associate Professor of Leadership and Associate Dean (Indigenous) at Melbourne Business School and the University of Melbourne's Faculty of Business and Economics. Her main research interests are Indigenous leadership, Indigenous business, and Indigenous economic development. Michelle is the founding Director of the Dilin Duwa Centre for Indigenous Business Leadership.

Duncan McDonnell

Duncan McDonnell is Professor of Politics at Griffith University in Brisbane. His main research interests are political parties and populism. From 2022 to 2026, he is an Australian Research Council Future Fellow. His most recent book, co-authored with Annika Werner, is International Populism: The Radical Right in the European Parliament (2019), published in the UK by Hurst and in the US by Oxford University Press.

Notes

1 Senator Aden Ridgeway (Democrats) was the sole Indigenous member of the federal Parliament in 2001. He served from 1999 to 2005. Ridgeway was only the second Indigenous member of parliament, after Senator Neville Bonner of the Liberal Party (1971–1983).

2 Given that the vast majority of candidates elected at state, territory and federal levels come from one of the two major parties in each jurisdiction, we focus on those parties in this study. These are: (1) the Australian Labor Party (ALP), the main party on the Left in all states and territories; (2) the Liberal Party, the main party on the Right in all states and territories except Queensland and Northern Terrority; (3) the Liberal National Party (LNP), the main party on the Right in Queensland; (4) the Country Liberal Party (CLP), the main party on the Right in the Northern Territory. Given that the LNP is a merger of the Liberal Party and National Party in Queensland, all references to ‘the Liberal Party’ in the article include the LNP.

3 The strongest quota is that of Queensland Labor whose rules state that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander candidates for Federal and State parliaments must constitute ‘a minimum of 5 per cent of held and winnable seats’ (Emphasis added, Queensland Labor Citation2019). New South Wales Labor does not stipulate that this 5% quota needs to be winnable (Australian Labor Party NSW Branch Citation2020, 56), while Western Australian Labor refers to the 5% threshold as an ‘aspirational objective’ for its state parliamentary representation (WA Labor Citation2019: 40).

4 See McCann and Sawer (Citation2019, 490) on the Liberal Party’s rejection of quotas for women candidates and its use instead of ‘aspirational targets’ which are unlikely to be met.

5 See Hughes (Citation2011, 604), who discusses how ‘minority women are especially likely to benefit when national gender policies are adopted alongside minority quotas’.

6 We thank Feodor Snagovsky for making his dataset of ethnic minority candidates available to us.

7 Analysing the 2019 Federal Election, Gauja and Taflaga (Citation2020, 72–73) could find evidence of contested House of Representatives pre-selections in only 33 cases across Australia (6% of all pre-selection processes).

8 This strategy can be used both for candidates who were not previously party members and also for candidates who may be party members, but have no connection to the constituency.

9 There exists no official list of Indigenous candidates, hence our need to investigate the array of sources listed. While we dedicated an extensive amount of time to this part of the data gathering and examined sources exhaustively, we cannot fully exclude the possibility that we may have missed out some candidates, particularly in the earlier years of the 2000s, for which there are less sources available. This relates also to one of the main reasons (beyond the fact that very few Indigenous candidates were elected prior to 2001) why we established 2001 as a cut-off point: the longer before 2000 one seeks to investigate candidatures, especially at state and territory levels, the higher the risk of errors and omissions.

10 Where explicit confirmation of gender was not available, our men/women distinction is an assumption based on name and appearance. In presenting our findings, therefore, we acknowledge that there could be non-binary or intersex candidates where gender identity was not publicly reported.

11 The 5% difference approach is in line with the definition of ‘fairly safe seat’ by the Australian Electoral Commission as ‘a seat where the elected candidate received between 56 per cent and 60 per cent of the vote’. See https://www.aec.gov.au/footer/glossary.htm. Given, however, the increased electoral volatility in some state elections over the past decade (e.g. Queensland 2012 and 2015), we also consider the 10% margin.

12 As part of our broader project, we also interviewed a number of candidates who stood successfully in early periods. These included prominent figures such as Jack Ah Kit (who became the first Indigenous minister in the Northern Territory in 2001) and Marion Scrymgour (who became the first Indigenous woman elected to a parliament in Australia when she won the NT seat of Arafura in 2001).

13 WA Labor State Executive may waive it ‘where it is deemed to be in the Party’s interests’ (WA Labor Citation2019: 48), while the VIC Liberals Administrative Committee can decide ‘by a threequarters majority of those present and voting that there are exceptional circumstances for abridging the time limit’ (VIC Liberal Party Citation2019, 50).

14 Patrick Dodson is a nationally renowned Indigenous leader often called the Father of Reconiliation due to his roles as a Royal Commissioner into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody and as the Founding Chair of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation 1991–1997. Nova Peris is a famous athlete and hockey player who, in 1996, became the first Aboriginal Australian to win an Olympic gold medal (for hockey).

15 See Table B1 in the Appendix for more details.

16 Since the NT has consistently elected 1 ALP and 1 coalition Senator at federal elections, being chosen as the number 1 Senate candidate in the NT by either of the two major parties effectively guarantees a successful outcome.

17 See in the Appendix for more details.

18 No Liberal partisans lost their first election and then won a later one, although, at the time of writing, Jacinta Price appears highly likely to do so in the 2022 Federal election.

19 As noted in the introduction, Mundine would in 2019 become a parachute candidate for the Liberal Party.

20 See the explanation in footnote 16 about why being first on the NT Senate list for the ALP and CLP essentially guarantees that candidate a seat.

21 Although she did not stand between 2010 and 2019, we interviewed Marion Scrymgour in December 2021. She recalled how, ‘when I went to the Labor Party, when I sought preselection, I was told that only a man can win a bush seat’. Despite that opposition, she stood for the NT seat of Arafura in 2001 and became the first Indigenous women elected to a state, territory, or Federal parliament in Australia.

22 We should note that successful Indigenous candidates may also face specific and significant challenges once they actually get into office. On this point, see Maddison (Citation2010).

23 According to the 2016 census, the population of Arafura was 90.1% Indigenous. See: https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/SED70001

24 After repeated requests, one state Labor party secretary eventually disclosed to us that 2.7% of their membership was Indigenous. When we replied ‘thank you, but how many people actually is that?’, we were told they could not possibily reveal such information.

References

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare). 2021. Profile of Indigenous Australians. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/profile-of-indigenous-australians.

- Australian Labor Party (NSW Branch) Rules. 2020. Viewed June 12, 2021. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/nswlabor/pages/820/attachments/original/1588746623/2020_NSW_Labor_Party_Rules.pdf?1588746623.

- Beauregard, Katrine. 2018. “Partisanship and the Gender Gap: Support for Gender Quotas in Australia.” Australian Journal of Political Science 53 (3): 290–319.

- Caul, Miki. 2001. “Political Parties and the Adoption of Candidate Gender Quotas: A Cross-National Analysis.” Journal of Politics 63 (4): 1214–1229.

- Celis, Karen, and Silvia Erzeel. 2017. “The Complementarity Advantage: Parties, Representativeness and Newcomers’ Access to Power.” Parliamentary Affairs 70 (1): 43–61.

- Cross, William, and Anika Gauja. 2014. “Designing Candidate Selection Methods: Exploring Diversity in Australian Political Parties.” Australian Journal of Political Science 49 (1): 22–39.

- Farrer, Benjamin David, and Joshua N. Zingher. 2018. “Explaining the Nomination of Ethnic Minority Candidates: How Party-Level Factors and District-Level Factors Interact.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 28 (4): 467–487.

- Gauja, Anika, and Marija Taflaga. 2020. “Candidates and pre-Selection.” In Morrison's Miracle: The 2019 Australian Federal Election, edited by Anika Gauja, Marian Sawer, and Marian Simms, 71–89. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Hazan, Reuven Y., and Gideon Rahat. 2006. “Candidate Selection: Methods and Consequences.” In Handbook of Party Politics, edited by R. S. Katz and W. Crotty, 109–121. London: Sage.

- Hazan, Reuven Y., and Gideon Rahat. 2010. Democracy Within Parties: Candidate Selection Methods and Their Political Consequences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hughes, Melanie M. 2011. “Intersectionality, Quotas, and Minority Women's Political Representation Worldwide.” American Political Science Review 105 (3): 604–620.

- Kittilson, Miki C. 2006. Challenging Parties, Changing Parliaments. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

- Kittilson, Miki C., and Katherine Tate. 2004. Political Parties, Minorities and Elected Office: Comparing Opportunities for Inclusion in the U.S. and Britain. Working Paper, Center for the Study of Democracy. Viewed June 13, 2021. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9j40k1m0.

- Koop, Royce, and Amanda Bittner. 2011. “Parachuted Into Parliament: Candidate Nomination, Appointed Candidates, and Legislative Roles in Canada.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties 21 (4): 431–452.

- Kulich, Clara, Michelle K. Ryan, and S. Alexander Haslam. 2014. “The Political Glass Cliff: Understanding How Seat Selection Contributes to the Underperformance of Ethnic Minority Candidates.” Political Research Quarterly 67 (1): 84–95.

- Liberal Party of Australia, Victoria Division. 2019. Constitution. Viewed February 7, 2022. https://members.liberalvictoria.org.au/uploads/memberresources/190710-025504_Liberal%20Party%20-%20Vic%20Div%20-%20A%20-%20Constitution%20-%20amended%20by%20166%20SC%20APPROVED.pdf.

- Maddison, Sarah. 2010. “White Parliament, Black Politics: The Dilemmas of Indigenous Parliamentary Representation.” Australian Journal of Political Science 45 (4): 663–680.

- Mansbridge, Jane. 1999. “Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? A Contingent “Yes"‘.” The Journal of Politics 61 (3): 628–657.

- Martinez i Coma, Ferran, and Duncan McDonnell. 2021. “Australian Parties, Not Voters, Drive Under-Representation of Women.” Parliamentary Affairs. doi:10.1093/pa/gsab042.

- McCann, Joy, and Marian Sawer. 2019. “Australia: The Slow Road to Parliament.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Women’s Political Rights, edited by S. Franceschet, M. Krook, and N. Tan, 483–502. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mugge, Liza M. 2016. “Intersectionality, Recruitment and Selection: Ethnic Minority Candidates in Dutch Parties.” Parliamentary Affairs 69 (3): 512–530.

- Murray, Rainbow, Mona Lena Krook, and Katherine A. R. Opello. 2012. “Why Are Gender Quotas Adopted? Parity and Party Pragmatism in France.” Political Research Quarterly 65 (3): 529–543.

- Queensland Labor. 2019. 2019 Rules of the Australian Labor Party (State of Queensland). Viewed June 12, 2021. https://www.queenslandlabor.org/members/party-rules-html/.

- Snagovsky, F. 2019. Representation and Legitimacy: Diffuse Support and Descriptive Representation in Westminster Democracies, Unpublished PhD Thesis, Australian National University.

- Sobolewska, Maria. 2013. “Party Strategies and the Descriptive Representation of Ethnic Minorities: The 2010 British General Election.” West European Politics 36 (3): 615–633.

- Thomas, Melanee, and Marc André Bodet. 2013. “Sacrificial Lambs, Women Candidates, and District Competitiveness in Canada.” Electoral Studies 32 (1): 153–166.

- Van der Zwan, Roos, Marcel Lubbers, and Rob Eisinga. 2019. “The Political Representation of Ethnic Minorities in the Netherlands: Ethnic Minority Candidates and the Role of Party Characteristics.” Acta Politica 54: 245–267.

- WA Labor. 2019. 2019 WA Labor Rules & Constitution. Viewed June 12, 2021. https://walabor.org.au/media/prijkyex/2019wa-labor_rules-constitution_web.pdf.

- Williams, Meaghan, and Robert Schertzer. 2019. “Is Indigeneity Like Ethnicity? Theorising and Assessing Models of Indigenous Political Representation.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 52 (4): 677–696.

Appendix

Section A: Election Data

Table A1. Labor, Liberal and CLP Indigenous candidates at federal, state and territory elections, February 2001–May 2021.

Table A2. Indigenous candidates, federal and state, by electoral system type: 2001–2021.

Section B: Interviews

As explained in the article’s section on ‘Indigenous candidates since 2001’, we identified candidates by consulting federal, state, and electoral commission data; parliamentary websites; party websites; candidate webpages; candidate social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram); and media reports. We were able to use this list to establish that 62 Indigenous candidates had stood for the ALP, CLP and Liberal Party at state, territory, and federal levels between 2010 and 2019. We then attempted to locate all of these using multiple strategies. In the cases of those who were current representatives, our task was straightforward since we could simply contact their offices. For those who had either been unsuccessful or retired, it was more complicated to locate them (especially the further back in time they were). To get in touch with them, we relied on internet and email address searches, social media accounts, in addition to conversations with representatives and party officials who could provide help. In the end, we succeeded in finding a contact for almost all candidates, although some of these either declined to be interviewed or did not respond to numerous invitations.

For the purposes of this paper, we focused on the initial journey to candidature of those interviewed, i.e. the experience of being selected as a candidate for the first time. For some interviewees, their first time was during the 2010–2019 period, while for others it was earlier (e.g. if they had won prior to 2010 and stood again during the 2010–19 period or they had lost prior to 2010 and then stood again after that date). In other words, eligibility for inclusion was made on the basis of running as a candidate during 2010–2019, even if the first candidacy occurred earlier. This has ramifications for how party affiliation is represented in the paper as some candidates resigned and changed parties during their tenure or ran for different parties after their initial candidature (e.g. Alison Anderson in the NT was elected for the ALP in 2004 and 2008, but subsequently for the CLP in 2012). It also has implications for the geographical locations cited in Table A3 as a small number of interviewees moved jurisdictions and ran again for public office (this was the case, for example of former NT Chief Minister Adam Giles who initially ran for the Liberal Party in the ACT in 2004, but then for the CLP in the NT in 2008).

Table A3. Interviews with candidates who stood between 2010 and 2019.

Forty-six semi-structured interviews were conducted in person, with four taking place over Zoom. They lasted on average one hour. In person interviews were conducted by one or two interviewers. Each interview commenced with an introduction of the researchers, an overview of the project, acknowledgement of consent protocols, and explanation of the outputs of the research. Questions relevant to this paper explored the interviewee’s interest in joining a political party, their initial experiences in the party as a grassroots member (in the case of partisans), how they became candidates, what happened during the campaign, and the aftermath of the process. All interviewees who had been candidates were asked those questions. Although not relevant to this paper, in the case of elected representatives, we also discussed their careers in office, relationships with the party, and the challenges they have faced. At the end of the interview, we provided interviewees the opportunity to talk off the record, to share further contacts that might be helpful to the research, and to give any feedback on the project.

Interviews were discussed by the research team immediately afterwards to clarify any differing interpretations and to assist in consistency for the analysis process. Interviews were then transcribed, read multiple times by the team, and discussed. The transcripts were imported into NVIVO where a qualitative thematic coding protocol was undertaken following these stages: (1) reading the transcripts carefully to identify themes, interesting quotes, network connections across the interview transcripts; (2) the interview schedule was used to structure the coding tree; (3) additional thematic coding arose to characterise experiences and perceptions described by the interviewee and the emerging theoretical contributions deemed significant by the researchers.