ABSTRACT

Beginning explorations of civil society organisations (CSOs) from a democratic, political, or regulatory perspective potentially overlooks important aspects of CSO activity. Instead, this paper takes CSOs in action as its starting point – specifically, Australian CSOs responding to the needs of people and communities during the crisis of the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Working between reflections by Australian CSO leaders during the pandemic and selected literature, a multi-grounded theory approach is used to produce a novel theoretical contribution – a typology of 10 distinct CSO activities. These 10 activities are divided into three categories: (1) The ‘Big Three’ activities – advocate systemically, deliver service and build capacity; (2) ‘Business As Usual’ activities – engage community, manage organisation and work collaboratively; and (3) ‘Enabling’ activities – conduct research, coordinate network, hold space and provide funding. The final three activities are revealed as being less integrated into the broader CSO literature than their more commonly explored counterparts.

Introduction

In countries like Australia, the response of civil society organisations (CSOs) to the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic highlighted the various democratic roles performed by this broad swathe of non-government, non-profit, for-purpose entities, associations, alliances, collectives, institutions and groups. From small, community-based, mutual aid and volunteer groups, to some of Australia’s largest charities and interest groups, CSOs were simultaneously meeting people’s material needs, encouraging governments to do the same, and working towards a better post-pandemic future (Coram et al. Citation2021; Foote et al. Citation2023; Riboldi, Fennis, and Stears Citation2022; Seibert, Williamson, and Moran Citation2021; Wearring, Dalton, and Bertram Citation2021). This paper uses the endeavours of 82 Australian CSOs during COVID-19 to generate a typology of 10 CSO activities, through which researchers can better understand the contributions of CSOs in crisis and beyond. In doing so, I highlight gaps in existing literature surrounding CSO activity. I suggest these gaps emerge when the starting point for examining CSOs focusses more on their relationship with the state than how CSOs respond to the needs of people and communities.

This article takes an expansive view of civil society and CSOs, broadly aligning with the three-sector approach, i.e. market, state and civil society or third sector. This connects with ideas of CSOs being predominantly non-profit, non-government organisations – organisations which mediate connections between people and the state (e.g. Bolleyer Citation2021), often in competition with the interests of market-orientated individuals and organisations. This broad conception of civil society and CSOs is also consistent with that of the 2018 Civil Society Futures initiative in the United Kingdom:

Civil society involves all of us. When we act not for profit nor because the law requires us to, but out of love or anger or creativity, or principle, we are civil society … when we organise ourselves outside the market and the state, we are all civil society. (Civil Society Futures Citation2018, 121)

Many excellent scholars have written about subsets of CSOs – non-government, non-profit, and social movement organisations: interest groups, civic associations, charitable service providers, philanthropists, think tanks, community centres, churches, trade unions, political parties, arguably even universities and social enterprises. My interest here is in the whole, having observed in my professional and academic careers that the kind of change I am interested in – largely progressive, largely socially democratic – occurs when various types of groups and organisations work together.

The need for the typology emerged while I was analysing the dataset for a different purpose, through which I discovered a need for a clear picture of the range of activities conducted by CSOs. The data from the interviews and focus groups of CSO activity during COVID-19 was producing stories of Australian CSOs in action – ranging from in-depth case studies that involved multiple participants and CSOs, to short vignettes observed by a single interviewee or focus group participant. When I began exploring these stories through the lens of existing literature, I found that existing lists, frameworks and typologies of CSO activity were insufficient to explain some of the factors and activities emerging through these stories. Essentially, scholars have tended to approach CSOs from a democratic or political function point of view (e.g. Fung Citation2003; Halpin Citation2006; Keane Citation2020; Vromen Citation2005; Warren Citation2001) or from the perspective of how governments regulate CSOs (e.g. Bolleyer Citation2021; Garton Citation2009; Harding Citation2014). These approaches without doubt hold great value, but they weren’t sufficiently answering the question of: what do civil society organisations do? Thus, working back and forth between a selection of literature and the dataset of Australian CSO leaders’ reflections on their experiences during the height of the pandemic, I developed the typology of 10 CSO activities presented in this paper.

Responding to the needs of people and communities in crisis – whether through meeting people’s immediate needs, building the resilience to face future crises, or attempting to change the conditions which cause crises in the first place – is core CSO business. The ways that Australian CSOs responded to the various crises of COVID-19 as presented in this paper therefore potentially encompass a full spectrum of CSO activity. I reinforce this claim in the second half of the paper by analysing the typology through the lens of selected CSO literature. At the same time, having an atypical crisis like COVID-19 as a focal point may elevate certain activities while obscuring others. The frequency with which the activities in the typology are conducted is therefore of less general importance than the emergence of the activities within a wholistic typology of CSO activity. That said, an important potential use of the typology is to examine the extent to which CSOs perform different activities in different contexts. This paper presents a picture of how Australian CSOs responded to COVID-19.

Different approaches to studying CSOs

The community of researchers and regulators around CSOs tend to approach their subject from a perspective and purpose other than the CSOs themselves, in particular the role of CSOs as democratic mediator between the interests of citizens and the state. Halpin observes that ‘for the most part, groups seem to be parachuted into theoretical discussions where a vehicle – or an agent – needs to be introduced to serve a democratic linkage function’ (Citation2010, 14). This perspective arises from the normative expectations on CSOs within a pluralist democratic system – an evolving decentralisation of power from the state through people’s freedom to associate, organise and advocate for their interests (Dahl Citation1978). Most scholars agree this takes the form of: (1) aiming for equality of representation and opportunity through reasoned deliberation and negotiation as a method of solving conflicts; with (2) the need for more confrontational or oppositional power negotiations from time to time to overcome entrenched interests resistant to change (Dryzek Citation2002; Fung Citation2005; Honig and Stears Citation2011; Medearis Citation2015; Wolin Citation2018). Keane poetically describes this as democracy having a ‘punk quality. It is anarchic, permanently unsatisfied with the way things are. The actions unleashed by its spirit and institutions create space for unexpected beginnings’ (Citation2022, 197). At a practical level, this variability can be seen in the types of systemic advocacy that CSOs can engage in – from lobbying decision-makers behind closed doors or partnering with government to deliver public services, to engaging in public debate, public protest and other more antagonistic social movement activities.

Analysis of systemic advocacy and other CSO activities can be found through the work of Fung and Warren. Fung outlines six potential democratic contributions of associations: (1) the intrinsic good of association and freedom to associate; (2) civic socialisation and political education; (3) resistance and checking power; (4) interest representation; (5) public deliberation and the public sphere; and (6) direct governance – situating them variously within three ‘contrasting ideals of democratic governance’ (Citation2003, 529): liberal minimalism, representative democracy, and participatory democracy. Warren (Citation2001), thinking about the democratic effects of CSOs, outlines three broad categories: (1) developmental effects on individuals (efficacy, information, political skills, civic virtues and critical skills); (2) public sphere / discourse effects (public communication and deliberation, representations of difference, representations of commonality); and (3) institutional effects (representation, resistance, subsidiarity, coordination and cooperation, democratic legitimation). More concrete activities can be induced from these – for example, Warren’s three categories map loosely onto the commonly regarded CSO activities of capacity building, systemic advocacy and charitable service delivery, as can Fung’s six democratic contributions. Both also imply the activity of community engagement, which certainly aligns with democratic expectations of CSOs. At the same time, Fung and Warren’s work results from consideration of democratic contributions and effects, and as such potentially overlook less substantive CSO activities in favour of those which have impacts that are less easily connected to these normative roles for CSOs.

From a related perspective, Vromen (Citation2005, 95) approaches CSO activities as ‘the political strategies Australian third sector organisations utilise in partnership, negotiation with, and opposition to, the state’. They do so by identifying seven political strategies within the Insider/Outsider spectrum (e.g. Maloney, Jordan, and McLaughlin Citation1994), with three insider strategies (lobbying, service provision, advocacy), three outsider strategies (community organising, public education and protest) and one insider/outsider strategy (strategic research). While these activities are more focussed and detailed than Warren and Fung’s, at least two of these CSO political strategies, protest and lobbying, are clearly sub-strategies of systemic advocacy, as can be public education and strategic research, depending on the perspective (e.g. Onyx et al. Citation2010). Further, by taking the starting point as the CSO’s political relationship with the state, Vromen’s seven strategies still potentially exclude important CSO activities that are more focussed on delivering direct outcomes for people and communities than interactions with government, or even CSO activities which enable other activities.

Another major starting point for thinking about what CSOs do is from a legal or regulatory perspective. Clearly, the legislative authorising environment that CSOs exist within impacts the choices made around activities. Bolleyer observes that this approach takes a ‘rule and control’ view of the state, wherein CSOs are ‘meaningfully bound by those (legal) constraints in their everyday activity’ (Citation2018, 6). This also problematises the funding relationship between CSOs and governments – CSOs often advocate for public funds to perform activities that the state elects not to do, in particular charitable service delivery; yet entering funding arrangements with the state, or even philanthropic capital, potentially compromises a CSO’s independence and legitimacy. Consistent with democratic theory outlined above, Bolleyer describes this relationship as ‘increasingly close but still contested’ (Citation2018, 6).

In exploring how CSOs are and should be regulated, Garton (Citation2009, 42) outlines seven functions of CSOs which interact with governments and markets:

(a) market support; (b) the provision of public goods; (c) the provision of private goods analogous to public goods; (d) the facilitation of political action; (e) the provision of cultural services; (f) the facilitation of self-determination; and finally (g) the facilitation of entrepreneurship.

Some of the grey regulatory literature relating to CSOs provide a more expansive view outline of what CSOs do, albeit in ways which focus on economic inputs. For example, the Australian Charities and Nonprofits Commission (ACNC), to which around 60,000 Australian CSOs report to annually as part of their requirements for maintaining taxation benefits, reports on the size, location and funding sources of CSOs. Unfortunately, their ‘activity’ categories – the largest of which are education; community development; religion and faith-based spirituality; human services; and health (ACNC Citation2023) – are part activity, part category and part sector. However, the Australian Productivity Commission’s 2010 review of the non-profit sector, or at least those parts of the sector deemed ‘economically significant’ (Productivity Commission Citation2010, 36), provides a framework through which policymakers and funders might gauge the impact of CSOs. CSO activities can largely be inferred through the four categories in the outputs section of the Productivity Commission’s framework: (1) Services (to clients or members); (2) Connecting the community (through events and activities, networks or volunteer engagement); (3) Influence (lobbying, research, education, others); and (4) Community endowment (maintaining and creating assets). While the first three of these output categories map neatly onto the familiar activities of charitable service delivery, community engagement and systemic advocacy, this final output category – community endowment – suggests a role for CSOs in building and holding spaces for community use.

A particularly detailed classification system for CSOs comes in the form of CLASSIE-A Classification System for Social Sector Initiatives and Entities (CLASSIE). This resource, developed by Australian B-Corp Our Community in conjunction with ‘more than 50 Australian subject matter experts’ (Our Community Citationn.d, 15) is used by the ACNC’s charity register to generate their broad activity areas for CSOs and is based on the similarly well-established Philanthropy Classification System (PCS) in the US. The more granular CLASSIE Activities Classification Framework, used for funding CSOs via SmartyGrants, covers both economic inputs and outputs that suggest a variety of activities. The catergories used by the CLASSIE Activities Classification Framework are: Operational costs, Project/program costs, Capacity building, Capital costs, Equipment/vehicle costs, Network building and collaboration, Advocacy, Fundraising costs, Research and development, Monitoring and evaluation, Travel, Legal costs, Unknown or not classified. Of the CSO activities already discussed, the CLASSIE Activities Classification Framework excludes only charitable service delivery and community engagement, potentially attributable to this framework being used for actually funding charitable interventions.

Overall, the various frameworks and lists outlined above – approaching CSOs from a broadly, democratic, political or regulatory position – clearly have their own function and use. At the same not, by starting from where they do, and not what CSOs actually do out in the wild, these approaches potentially miss important CSO activities and contributions. In the next section, this paper attempts to improve on these existing typologies by taking what CSOs do as the starting point.

Creating the typology

The typology presented in this paper has been generated using a multi-grounded theory approach, whereby theory development derives through the interplay between empirical data, research interest and existing theories (Goldkuhl and Cronholm Citation2010). In essence, the typology synthesises inductive analysis from the data as well as deductive analysis based on the work of other scholars, namely those outlined in the previous section. As opposed to more traditional grounded theory, which focusses on the development of theory out of an empirical dataset (e.g. Charmaz Citation2014; Glaser and Strauss Citation2010; Tarozzi Citation2020), multi-grounded theory highlights the importance of relating ‘the evolving theory to established research during the process of theorising. Existing theory can be used as a building block that supports the empirical data forming the new emergent theory’ (Goldkuhl and Cronholm Citation2010, 191). A description of the process of developing the typology might illustrate how this has worked in practice.

The empirical data used in this paper consists of the reflections of 91 Australian CSO leaders – CSO CEOs, staff, consultants, academics, owner-operators and volunteers – representing 82 different organisations. They participated in a total of 41 interviews and 12 focus groups, between June 2020 and August 2021, in which they discussed and reflected on their practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data were collected in the context of a strategic partnership between the Sydney Policy Lab at the University of Sydney and the Paul Ramsay Foundation, which focussed on for-purpose sector capability in the context of the pandemic through the lenses of leadership, community connection, advocacy and influence, and systems and networks (Riboldi, Fennis, and Stears Citation2022). Over the course of data collection, efforts were made to secure a broad range of participants across a variety of types of organisations in terms of structure, size, geography and purpose. Initial participants were selected via their existing connection with the two strategic partners, members of the research team and the project’s advisory group, and generally snowballed from there.

shows that close to 70 per cent of participants’ organisations were registered with the ACNC, which includes universities and churches but excludes trade unions, political parties and social enterprises. Around half of those CSOs were categorised as large by the ACNC, with an annual avenue of over $1 million. Further analysis of the ACNC dataset revealed that of the 39 ‘large’ CSOs, 10 had income and expenditure over $100 million in the 2021 reporting period, including three universities. In comparison, shows the primary focus area of the CSOs to which participants were closely connected. The highest primary focus for participants’ CSOs was Justice & Rights organisations, representing around 16 per cent of the total. CSOs working on issues relating to Children & Youth, various types of immigration (Migration / Multiculturalism; People Seeking Asylum & Refugees) and First Nations communities were also well represented. While effort was made to connect with a wide array of people and organisations, this range of participants, their respective organisations and primary focus areas is not necessarily representative of the CSO sector in Australia. For example, over 70 per cent of the participants’ CSOs were located primarily in New South Wales, whether they worked at a local, state, or national level, and none of the participating CSOs had a priority focus area relating to the environment or climate change, which are clearly important areas of CSO activity. These factors limit certain avenues of analysis, though not necessarily the one at the heart of this paper.

Table 1. Participants’ organisations by ACNC registration status.

Table 2. Primary focus area of participants’ CSOs.

The initial coding process of the transcripts of interviews and focus groups was conducted using qualitative analysis software NVivo, guided by the four CSO thematic capability areas from the overarching strategic partnership that was funding the research. The initial series of codes emerged from participants’ observations, including note of ‘good stories’ of CSOs in action during the pandemic. As noted earlier, these included short vignettes from individuals as well as more detailed case studies involving multiple participants.

After approximately 20 per cent of the data had been entered, a preliminary analysis yielded some interesting results. First of all, participants had typically described what they or their organisations were doing, which aligned more with the idea of ‘activities’ than the more conceptual capability areas on which the project was focussed. Second, the way that activities were being conducted was an important factor that emerged while one of the longer stories was being prepared for a conference paper. For instance, the success of an advocacy campaign by a coalition of CSOs on behalf of international students relied on activities which had not previously been considered; in particular, the way that the coalition was coordinated and the importance of different physical and online spaces, and the CSOs that created and held these spaces. In order to understand how CSOs connected to people and communities, I required a clearer picture of exactly what CSOs did. And the ‘Big Three’ CSO activities of advocate systemically, deliver service and build capacity couldn’t sufficiently explain what was emerging from the data.

The next step was to create an initial list of CSO activities based on the stories that had emerged through the data up to that point. From the case of advocacy around international students, for example, I added coordinate network and hold space. I then conducted a review of existing typologies and frameworks of CSO activity, namely those in the previous section. While this literature had many of the activities that I had identified from the data, it did not account for all of them. Thus, in order to successfully explore the capability of CSOs to meet community need, I needed a comprehensive picture of exactly what CSOs do – a typology of CSO activities.

An initial typology was created based on the literature and the initial round of coding. Unfortunately, the initial coding process had been thematically broad and did not necessarily map onto CSO activities. For example, when I had coded participants talking about ‘funding’, mostly participants were talking about their funding relationship with governments, though sometimes they were talking about some of the strategic challenges involved in managing their organisation, and sometimes they were talking about providing funding to other CSOs. In the final typology, these fall across three separate activities: work collaboratively (in the context for example, of how funding practices can inhibit collaboration between CSOs), manage organisation (whereby securing resources like funding can be of strategic concern to an organisation’s existence), and provide funding (where well-resourced CSOs, like philanthropic foundations, provide funding to others).

Next, I re-analysed and re-coded the initial 20 per cent of the dataset to refine the initial typology, after which we continued to input and code the remaining data. This led to some adaptation of the initial CSO activities in order: to make them broad enough to encapsulate a range of activities (for example hold space was initially host space); to combine similar activities together (provide charity and deliver service were merged, because within the dataset the two more often than not referred to the same activity – the free provision of meeting a person’s need); or to distinguish two activities from each other. For example, engage community was originally coordinate volunteers, which had some crossover confusion with coordinate network. The clarification helps to distinguish that engage community is about when CSOs attempt to activate or engage people, whereas coordinate network is more about the ways that groups of people interact with each other. By the time 75 per cent of the data had been coded, the typology was finalised and underwent no further revisions – achieving a level of theoretical saturation consistent with both grounded theory and multi-grounded theory practice (Glaser and Strauss Citation2010; Goldkuhl and Cronholm Citation2010).

The final stage of developing the framework involved sorting the ten activities into three different categories. This too was an abductive process, assisted by the analysis of the data presented in and . The ‘Big Three’ activities: advocate systemically, deliver service and build capacity, appear in all the academic literature and most of the grey literature. The ‘Business As Usual’ activities: engage community, manage organisation and work collaboratively appear to varying degrees in the literature. More significantly, none of the participants’ CSOs had these ‘Business As Usual’ activities as their primary one, suggesting that all CSOs conduct these activities in some way, and informing the title of the category. The remaining four, ‘Enabling’, activities I identified: conduct research, coordinate network, hold space, and provide funding – with the exception of conduct research – barely appeared in the academic or grey literature. This suggests they were not primary activities, although clearly there are CSOs which specialise in each of these activities, and thus they were identified as ‘enabling’ activities.

Table 3. CSO activities by main activity of participants’ CSOs and total participant references.

Table 4. CSO activities considered by activity typology and selected democratic and regulatory literature.

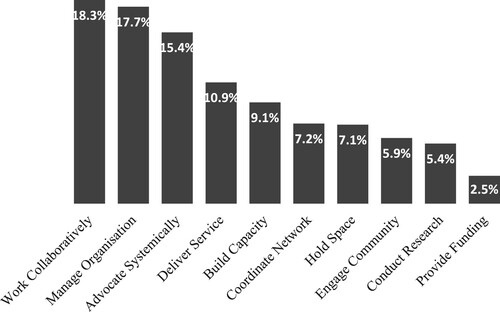

A typology of CSO activities

This section presents the 10 CSO activities which resulted from the process described in the previous section and portrayed visually in . Each activity is accompanied by a brief generalised definition of the activity, followed by examples of how the activity appears in the dataset and finally observations about the prevalence of the activity in the literature. A few issues arise which suggest the need for further discussion and analysis, but are largely outside the scope of this paper. shows the 10 CSO activities based on the proportion of total references to these activities in the dataset. The limitations of the dataset means these results are not necessarily representative of the attention given to these activities by CSOs more generally. Nevertheless, for the purposes of this paper, I have presented the activities in the highest to lowest references in the dataset – i.e. beginning with work collaboratively (18.3 per cent of total references) and ending with provide funding (2.5 per cent of total references). Quotations have been anonymised. Further detail about many of the stories referenced below, as well as a full list of participants and organisations, can be found in the report Nurturing Links Across Civil Society – lessons from Australia’s for-purpose sector’s response to COVID-19 (Riboldi, Fennis, and Stears Citation2022).

Work collaboratively

CSOs working collaboratively with each other, with communities, with government agencies and with industry is perhaps unsurprisingly the most mentioned activity in the dataset and why it is one of the ‘Business As Usual’ activities. Whether in formal or informal networks, and commonly occurring in conjunction with various other CSO activities, the prevalence of participants talking about working collaboratively is a sign of the prevalence of CSO participation in responding to crises in pluralist systems (Oh, Ding, and Kim Citation2024; Simo and Bies Citation2007). Numerous examples of Australian CSOs collaborating with each other during the pandemic emerged through the dataset. These included a coalition of organisations, convened by the Sydney Alliance, which supported temporary visa holders who were excluded from the public support provided to others living in Australia; early childcare organisations working together, through intermediary organisation The Front Project, to ‘model the impact of COVID on the sector’ to ensure the Australian government funding free child-care for a three-month period at the height of the crisis; and communities with established place-based collaborations, such as through Hands Up Mallee in regional Victoria, who were able to ‘mobilise’ and ‘respond quickly in food security – they had the infrastructure and relationships’. Of the scholars mentioned earlier, only Warren highlights the importance of CSO collaboration, via the institutional democratic effects achieved through coordination and cooperation. In the grey literature, both the Productivity Commission framework and the CLASSIE Activities Classification Framework acknowledge collaborative activity – the Productivity Commission through the output of ‘Connecting the community – network activities’, and CLASSIE through ‘Network building and collaboration’.

Manage organisation

This second ‘Business As Usual’ CSO activity – manage organisation – emerged via participants reflecting about the activities required to keep their organisations functioning, particularly during the pandemic. These activities include issues of self-governance, strategic decision making, measurement and evaluation, as well as negotiating relationships with funders, decision-makers and the public. The focus groups and interviews invited participants to be reflective of their practice, which revealed ways CSO leaders adapted to the conditions of COVID-19 as well as past decisions which influenced how CSOs responded to the pandemic. Some organisations had responded by tightening the purse-strings and effectively shutting down, while others had innovated and looked for new ways to engage community members. It also included reflections from Asthma Australia about how they had years previously moved from a federated structure to a single national organisation as a result of extensive consultation, which saw this organisation shift towards a more partnership-oriented approach rather than a direct advocacy one. Other responses raised the general concern of a ‘rise of corporate leaders in our sector driving a for-profit by another name’. Manage organisation as a CSO activity is partly covered by two of Garton’s (Citation2009) functions of CSOs: ‘the facilitation of self-determination’ and ‘the facilitation of entrepreneurship’, but is not specifically mentioned by scholars with a starting point of democratic or political theory. The CLASSIE Activities Classification Framework also covers this CSO activity, through the inclusion of ‘Monitoring and evaluation’.

Advocate systemically

The first ‘Big Three’ CSO activity, systemic advocacy is a well-acknowledged, involving explicit efforts to achieve change or impact on behalf of a group of people (e.g. Onyx et al. Citation2010). Advocacy encapsulates a wide variety of activities, from street protests to directly lobbying MPs, to the utilisation of traditional and social media. Systemic advocacy often goes hand in hand with other CSO activities, with most CSO service providers also engaging in this activity (Minkoff Citation2002). All the major stories emerging from the dataset involved advocacy in some form. For example, the Raise the Rate (of public funding for the unemployed) campaign, led by the Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS), had to adapt to a ‘fundamental shift’ in government policy that ‘doubled unemployment payments’ in April 2020, well above what ACOSS had been advocating for. Other stories ranged from how high-profile Australians like Craig Foster used their national ‘platform in constructive and productive ways in traditionally politicised issues’, particularly in relation to the rights of refugees and people seeking asylum, to the smaller-scale advocacy activity of local bakery owners David and Bev Winter, who lobbied their local council and state Member of Parliament to secure support for a volunteer powered food relief project. Perhaps unsurprisingly, most CSO literature notes advocating systemically as an important CSO activity. The exception is the ACNC, which potentially excludes advocacy because it is an assumed activity or, more likely, a contentious and politicised one in Australia (Onyx et al. Citation2010; Phillips and Murray Citation2023).

Deliver service

Charitable service delivery is the second most referenced ‘Big Three’ CSO activity in the dataset, appearing between advocate systemically and build capacity in terms of frequency of mentions (see ). It is one of the oldest and most recognised CSO activities, funded potentially by membership contributions, public funding or private philanthropy. The social conditions of the pandemic – particularly physical distancing and working remotely – caused significant shifts in how service providers operated. This created new needs amongst communities, which CSOs inevitably attempted to meet. Participants observed multiple instances of CSO collaborations to provide emergency food relief, with the CSOs involved ranging from some of Australia’s largest, like the Australian Red Cross, to small newly emergent groupings that created mutual aid structures to support particular communities. This includes helping thousands of international students who were thrown into destitution when industries such as hospitality and tourism shut down. They received considerable support through professional sports clubs, which were also shut down but had available financial and human resources in the form of players to help. Charitable service delivery appears in most of the literature. The exception is the CLASSIE Activities Classification Framework (which lists all nine other activities). This is presumably because this framework is used explicitly for funding applications for charitable service delivery.

Build capacity

The final ‘Big Three’ CSO activity – build capacity – sees CSOs focussing on supporting community members to develop the skills, strengths and other resources they need to address challenges. This can include coordinating and delivering training, leadership development and education activities for both community members and other CSOs. It can involve CSOs committing long-term to supporting the aspirations of communities in particular areas, for example through community-orientated philanthropy (Pill Citation2019). As noted earlier, participants observed that communities with established place-based initiatives were able to respond effectively to the challenges of the pandemic. CSOs the Brotherhood of St Lawrence and CoHealth employed capacity building strategies when called on to support public housing residents confined to their homes by the Victorian Government. They employed residents to design and deliver strategies to ensure vulnerable community members could access crucial health services. Participants reported residents describing one of the interventions as being ‘the most authentic community engagement approach they’ve ever known’. Some CSOs saw the pandemic itself a capacity building opportunity, given how they ‘had to pivot and solve problems at a pace that they never have before’. In the literature, only the Productivity Commission’s framework for measuring the contribution of CSOs fails to explicitly mention capacity building, although it is implied through a number of the desired high-level impacts for community wellbeing, including ‘Safety from harm’ and the ‘Ability to exert influence’.

Hold space

The ability of CSOs to create and hold spaces emerged as important in the dataset but is less prominent in the literature. This activity involves CSOs providing spaces where people, communities and other CSOs can meet, without cost, and conduct other CSO activities, whether virtual or in person, permanent or temporary. It is one of the four ‘Enabling’ activities. The prominence of this activity in the dataset was perhaps due to the conditions of the pandemic forcing CSOs to be more conscious of the spaces that they usually occupy, or the number of participants whose CSOs specialise in this activity – including intermediaries, peaks and a handful of consultants. During the pandemic, CSOs used to convening people and communities in person, including faith-based organisations, had to find ways to shift practices online. Many service providers grappled with balancing the need to protect their workforces from contracting COVID-19 versus the need to continue supporting vulnerable communities. Some CSOs reported being forced to shut their doors by the local councils their services were embedded in. The CSOs which collaborated to support international students in Sydney could not have happened without the spaces held by two key CSOs: (1) the physical space of Addison Road Community Organisation, which turned itself into a mutual aid food distribution hub during the pandemic; and (2) the online space held by the Sydney Alliance in convening the coalition which advocated successfully for student access to emergency relief funding for food and housing. Hold space is not recognised in any of the academic literature. At the same time, the importance of ‘spaces’ exists in various diverse literatures, from the performativity of advocacy (Alexander Citation2017) or the importance of space in mutual aid and senses of public identity (Honig Citation2017). The CLASSIE Activities Classification Framework acknowledges hold space through the capital costs that a CSO might have, whereas the Productivity Commission’s framework arguably references this activity through categorising ‘maintaining natural & built assets’ as a ‘Community endowment’ output.

Coordinate network

This activity, the second most referenced of the four ‘Enabling’ activities, focuses on the act of holding a network together, from formal representative functions performed by peak bodies or many intermediary organisations, to more informal facilitation or convening of policy committees or advocacy coalitions. CSO leaders raised this activity in the context of the pandemic in various forms. This included reflections about which organisations were the most appropriate to convene a network – in the example of a coalition of legal service providers attempting to secure crisis funding from the government, it was decided that an organisation that would not directly benefit from the funding was the best CSO to bring other CSOs together. It also included observations about the ‘how’ of network coordination, with the facilitation of the Sydney Alliance around the coalition supporting international students being described as ‘absolutely extraordinary’, driven by a focus on outcomes and recognising ‘that everyone’s time is really valuable’. In terms of the literature, only the CLASSIE Activities Classification Framework acknowledges this CSO activity, and then only by association, through the category of ‘Network building and collaboration’. However, this activity can be seen emerging in more practice-focused literature – for example around CSO advocacy coalitions in practice (Mogus and Liacus Citation2016; Tattersall Citation2010) or some of the literature around CSO leadership (Ospina and Foldy Citation2010). This activity is closely connected to work collaboratively, with the differentiation being a focus on the ‘how’ of CSO collaboration.

Engage community

The final ‘Business As Usual’ activity is engage community. While engagement with citizens and other community members may be core business for CSOs, there is of course variability in the ways the CSOs engage with people and communities. This activity includes the coordination, training and activation of volunteer labour that typically contributes to other CSO activities, including mobilisation and organisation towards systemic advocacy targets, coordinating volunteers for charitable service delivery, and getting guidance from a CSOs stakeholders, formal or otherwise, on the strategic priorities for the organisation. Participant observations relating to this activity include ‘it’s amazing to see politicians really do listen to people’ and ‘the amount of free labour that underpins civil society is really important and should be recognised and we need to account for it’. Some participants were very aware of the potential for community engagement in core CSO activities. This includes ACOSS’s Raise the Rate campaign attempting to ‘enhance and amplify the voices of people affected’, as well as the internal consultation that Democracy in Colour conducted with its volunteer base that revealed the need for people to be able to air grievances after ‘the real crisis moments started to subside’. Of the literature explored, neither the CLASSIE Activities Classification Framework nor Garton’s seven functions of CSOs explicitly acknowledge engaging community members as something that CSOs do. In terms of CLASSIE, it is arguably implicit and thus unstated, whereas given Garton’s starting point being CSO interactions with the state and the market, interactions with community members are perhaps overlooked.

Conduct research

Research by CSOs is well-explored and the most familiar of the four ‘Enabling’ CSO activities. From universities, to think-tanks, to the in-house policy units of larger CSOs, conducting formal or informal research plays a crucial role in policy development, agenda setting, capacity building and various other activities. The comparably low number of references to this activity in the dataset is perhaps attributable to the nature of the crisis prioritising meeting people’s immediate needs over research. That said, research played an important role in the example of the childcare sector providing crucial information to help the government model and design policy responses. ‘That’s when I realized that a lot of expertise in the public sector has been stripped out’, one participant observed. CSO research also played a crucial role in advocacy around international students. Researchers from the Migrant Justice Initiative worked with a group of students to design and roll out a ‘national survey of people on temporary visas on the impact of COVID across a range of areas’, the results of which were used by service delivering collaborators like the Australian Red Cross to adjust how they were providing aid to this community, and by interest group GetUp to create a satirical video and inform media strategies to try and influence governments. In the literature, Vromen includes strategic research as one of her seven political strategies of the Australian third sector, while the Productivity Commission, the ACNC and CLASSIE all also recognise research as a contribution made by CSOs.

Provide funding

Our final CSO activity is the least mentioned within the dataset. Provide funding is the activity of coordinating, managing and distributing funding to community groups and other CSOs – clearly an ‘Enabling’ activity. Provide Funding can be seen in the way that some CSOs act as peak or umbrella organisations which collect and then distribute funding to smaller CSOs through recurrent funding or grant programs. It also exists in the primary function of philanthropic and other charitable foundations, which can be conducted with a wide degree of variability (Pill Citation2019). One of the ways this activity emerged in the dataset was the way the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) acted as a funnel for contributions to smaller community-based CSOs, taking on an administrative task that would be burdensome for the community organisations focussing on crisis response. Philanthropic foundation Dusseldorp Forum played a complimentary role convening, coordinating and encouraging philanthropic contributions to NACCHO and other First Nations organisations. Another participant observed the role of Australian Progress in providing advocacy grants to start-up campaigners, complemented by capacity building activities like constructing peer-to-peer networks. Along with coordinate network, this CSO activity is the one which appears least in the academic and grey literature. Garton highlights ‘the facilitation of entrepreneurship’ but this does not particularly cover the activity.

Conclusion

This paper has described the generation of a typology of 10 distinct activities for civil society organisations (CSOs), which have then been separated into three activity categories: (1) The ‘Big Three’ – advocate systemically, deliver service and build capacity; (2) ‘Business As Usual’ – engage community, manage organisation and work collaboratively; and (3) ‘Enabling’ activities – conduct research, coordinate network, hold space and provide funding. Derived using a multi-grounded theory approach from a dataset of Australian leaders’ reflections on their experiences during the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic, the typology has been tested against key academic and grey literature relating to the contributions of CSOs, and explored using the CSO leaders’ reflections and experiences. The typology has a potential utility in terms of constructing case studies of CSOs in action – the interactivity of CSOs and their activities that emerges from the dataset suggests high levels of complexity in terms of understanding CSO impact. The typology would also benefit from testing in other contexts – including other democracies with an active civil society, and in contexts where CSOs are responding to different types of crises. Although a limited dataset of 91 people from 82 organisations, there are further ways in which the typology can be utilised. For example, combining the typology with a more representative sample of Australian CSOs would likely provide insights into the workings of the diverse ecosystem of groups work to address some of the most significant challenges that people and communities face. Cross-sectoral comparisons, such as comparing how these activities play out in the housing sector compared to the environmental sector, may facilitate knowledge transition across what are on the surface quite diverse issues. Finally, the process has revealed three CSO activities which appear less integrated into the broader literature than their seven counterparts: coordinate network, hold space and provide funding. Their emergence as important activities within the focussing event of the pandemic, sitting alongside the well-recognised conduct research as activities which enable some of the more ‘frontline’ CSO activities, suggests that these activities warrant further attention, including integrating literature from other disciplines on these activities into broader discussions of what CSOs do and how they do it.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mark Riboldi

Mark Riboldi is a lecturer in social impact and social change at the UTS Business School, University of Technology Sydney.

References

- ACNC. 2023. Australian Charities Report [9th ed.]. Australian Charities and Not-for-Profits Commission.

- Alexander, Jeffrey C. 2017. The Drama of Social Life. Malden, MA: Polity.

- Bolleyer, Nicole. 2018. The State and Civil Society. Oxford University Press.

- Bolleyer, Nicole. 2021. “Civil Society – Politically Engaged or Member-Serving? A Governance Perspective.” European Union Politics 22 (3): 495–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165211000439.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. “Constructing Grounded Theory.” In Introducing Qualitative Methods. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Civil Society Futures. 2018. Civil Society in England – Its current state and future opportunity. Civil Society Futures – The Independent Inquiry. https://www.phf.org.uk/programmes/inquiry-future-civil-society.

- Coram, Veronica, Jonathon Louth, Selina Tually, and Ian Goodwin-Smith. 2021. “Community Service Sector Resilience and Responsiveness during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Australian Experience.” Australian Journal of Social Issues 56 (4): 559–578. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.167.

- Dahl, Robert A. 1978. “Pluralism Revisited.” Comparative Politics 10 (2): 191–203. https://doi.org/10.2307/421645.

- Dryzek, John S. 2002. Deliberative Democracy and Beyond. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/019925043X.001.0001.

- Foote, Wendy L., Amy Conley Wright, Jennifer Mason, and Tracy McEwan. 2023. “Collaboration between Australian Peak Bodies and Governments in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: New Ways of Interacting.” Australian Journal of Social Issues February: ajs4.260. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.260.

- Fung, Archon. 2003. “Associations and Democracy: Between Theories, Hopes, and Realities.” Annual Review of Sociology 29 (1): 515–539. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100134.

- Fung, Archon. 2005. “Deliberation before the Revolution: Toward an Ethics of Deliberative Democracy in an Unjust World.” Political Theory 33 (3): 397–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591704271990.

- Garton, Jonathan. 2009. The Regulation of Organised Civil Society. Oxford: Hart Pub.

- Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. 2010. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. 5. Paperback print. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction.

- Goldkuhl, Göran, and Stefan Cronholm. 2010. “Adding Theoretical Grounding to Grounded Theory: Toward Multi-Grounded Theory.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 9 (2): 187–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691000900205.

- Halpin, Darren R. 2006. “The Participatory and Democratic Potential and Practice of Interest Groups: Between Solidarity and Representation.” Public Administration 84 (4): 919–940. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00618.x.

- Halpin, Darren R. 2010. Groups, Representation and Democracy Between Promise and Practice. Oxford: Manchester University Press.

- Harding, Matthew. 2014. Charity Law and the Liberal State. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139136358.

- Honig, Bonnie. 2017. Public Things: Democracy in Disrepair. Fordham University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780823276431.

- Honig, Bonnie, and Marc Stears. 2011. “The New Realism: From Modus Vivendi to Justice.” In Political Philosophy versus History, edited by Jonathan Floyd and Marc Stears, 177–205. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Keane, John. 2020. “Hopes for Civil Society.” Global Perspectives 1 (1): 14130. https://doi.org/10.1525/gp.2020.14130.

- Keane, John. 2022. The Shortest History of Democracy. Collingwood, Vic: Black Incorporated.

- Maloney, William A., Grant Jordan, and Andrew M. McLaughlin. 1994. “Interest Groups and Public Policy: The Insider/Outsider Model Revisited.” Journal of Public Policy 14 (1): 17–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00001239.

- Medearis, John. 2015. Why Democracy Is Oppositional. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Minkoff, Debra C. 2002. “The Emergence of Hybrid Organizational Forms: Combining Identity-Based Service Provision and Political Action.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 31 (3): 377–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764002313004.

- Mogus, Jason, and Tom Liacus. 2016. Networked Change: How Progressive Campaigns Are Won in the 21st Century. NetChange Consulting.

- Oh, Namkyung, Minshuai Ding, and Yunkwon Kim. 2024. “How Do Non-Western Authoritarian Countries Respond to Disasters? Structural Difference from the Pluralistic Model.” International Review of Administrative Sciences March, https://doi.org/10.1177/00208523241231703.

- Onyx, Jenny, Lisa Armitage, Bronwen Dalton, Rose Melville, John Casey, and Robin Banks. 2010. “Advocacy with Gloves on: The ‘Manners’ of Strategy Used by Some Third Sector Organizations Undertaking Advocacy in NSW and Queensland.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 21 (1): 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-009-9106-z.

- Ospina, Sonia, and Erica Foldy. 2010. “Building Bridges from the Margins: The Work of Leadership in Social Change Organizations.” The Leadership Quarterly 21 (2): 292–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.01.008.

- Our Community. n.d. CLASSIE-A Classification system for Social Sector Initiatives and Entities. Our Community. Accessed January 22, 2024, from https://www.ourcommunity.com.au/classie.

- Phillips, Ruth, and Ian Murray. 2023. “The Third Sector and Democracy in Australia: Neoliberal Governance and the Repression of Advocacy.” Australian Journal of Political Science May: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2023.2213215.

- Pill, Madeleine C. 2019. “Embedding in the City? Locating Civil Society in the Philanthropy of Place.” Community Development Journal 54 (2): 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsx020.

- Productivity Commission. 2010. Contribution of the Not-for-Profit Sector. Canberra: Australian Government Productivity Commission.

- Putnam, Robert D. 1995. “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital.” Journal of Democracy 6 (1): 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1995.0002.

- Riboldi, Mark, Lisa Fennis, and Marc Stears. 2022. Nurturing Links Across Civil Society – The Australian For-Purpose Sector’s Response to COVID-19. Sydney Policy Lab, The University of Sydney. https://www.sydney.edu.au/sydney-policy-lab/our-research/nurturing-links-across-civil-society.html.

- Seibert, Krystian, Alexandra Williamson, and Michael Moran. 2021. “Voluntary Sector Peak Bodies during the COVID-19 Crisis: A Case Study of Philanthropy Australia.” Voluntary Sector Review 12 (1): 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1332/204080520X16081188403865.

- Simo, Gloria, and Angela L. Bies. 2007. “The Role of Nonprofits in Disaster Response: An Expanded Model of Cross-Sector Collaboration.” Public Administration Review 67 (s1): 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00821.x.

- Tarozzi, Massimiliano. 2020. What Is Grounded Theory? Bloomsbury ACADEMIC. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350085275.

- Tattersall, Amanda. 2010. Power in Coalition: Strategies for Strong Unions and Social Change. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

- Vromen, Ariadne. 2005. “Political Strategies of the Australian Third Sector.” Third Sector Review 11 (2).

- Warren, Mark. 2001. Democracy and Association. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Wearring, Andrew, Bronwen Dalton, and Rachel Bertram. 2021. “Pivoting Post-Pandemic: Not-for-Profit Arts and Culture Organisations and a New Focus on Social Impact.” Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 13 (2), https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v13.i2.7729.

- Wolin, Sheldon S. 2018. Fugitive Democracy and Other Essays. Edited by Nicholas Xenos. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.