Abstract

Background: Worldwide, nursing students comprise a large portion of students in higher education institutions (HEIs). The expectation that HEIs will educate professionally competent nurses is high. To ensure adequate competence, exit examinations play a significant role in evaluation in many countries. However, there has been no comprehensive analysis of the instruments used and the content evaluated in exit examinations globally.

Purposes: The aim of this study was to identify and describe the instruments used in undergraduate nursing students’ exit examinations.

Methods: Five databases were systematically searched, and eleven studies were included. The data of content used in exit exams were analysed using inductive content analysis. The instruments used in exit exams were tabulated and described. The systematic process was followed to identify included papers.

Results: Eleven different instruments were identified, including nine theoretical instruments and two clinical instruments. The exit examinations of undergraduate nursing students varied considerably depending on the country and educational organisation. The content evaluated in the exit examinations covered the holistic nursing perspective.

Conclusions: The findings of this review suggest that HEIs should develop and implement more comprehensive evaluation methods and instruments to ensure students’ competence upon graduation. The results are important for developing exit examinations in nursing education because they indicate that summative evaluation is needed. Clinical examinations have been used marginally in HEIs, which should be considered when implementing new examinations. Digitalisation (e.g. virtual environments) could be one solution for offering objective assessment, validity and cost-effectiveness.

Impact statement

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of undergraduate nursing students’ exit examinations and indicates that more clinical evaluation methods should be developed to ensure adequate competence.

Introduction

The evaluation of students’ competence is a major priority in higher educational institutions (HEIs) globally. Nursing students comprise a large portion of higher education students worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (Citation2020), demands on healthcare systems place high expectations on nursing educational institutions to educate professionally competent nurses. Additionally, multidimensional healthcare systems require nurses who have both specialised and general competence in different areas of nursing (Andersson et al., Citation2013). Faculties that educate nurses have the responsibility to ensure that students acquire high theoretical and practical competence as well as high moral standards in nursing to deliver high-quality and safe patient care (International Council of Nurses, Citation2012; National Council of State Boards of Nursing, Citation2020). The evaluation process should be comprehensive and formative throughout the nursing curriculum (Spector & Alexander, Citation2006). While formative evaluation is conducted to establish students’ progression throughout their training, summative evaluation is also needed to establish the learning outcomes achieved by students at the end of their courses. To ensure adequate competence upon completion of undergraduate nursing degrees, summative assessments, such as exit examinations (exams), are completed (Presti et al., Citation2019; Yates & Sandiford, Citation2013).

The evaluation of nursing students’ competence is a complex process. As defined by the European Federation of Nurses Associations (EFN, Citation2015), nursing education curricula should include the following competence areas: (1) culture, ethics and values, (2) health promotion and prevention, guidance and teaching, (3) decision-making, (4) communication and teamwork, (5) research and leadership, (6) nursing care (theoretical education and training) and (7) nursing care (practical and clinical education and training). Competence consists of knowledge, skills, attitude and values. The requirements of nursing competence areas are mainly parallel globally, but HEIs can determine how these requirements will fit into their curricula (EFN, Citation2015; International Council of Nurses, Citation2012; National Council of State Boards of Nursing, Citation2020).

There is, however, no global standard curriculum or exit exam for nursing education. The curricula, resources, state requirements and length of study programmes vary considerably in different countries. Structured methods, such as theoretical exams, are widely used in nursing education (Lejonqvist et al., Citation2016). Regardless of the purpose of the evaluation, a single evaluation method cannot evaluate all domains of students’ knowledge and skills, as each approach has its own advantages and disadvantages. Therefore, a variety of evaluation methods is required in education so that the shortcomings of one approach may be balanced by the advantages of another (Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013). Different methods of evaluating the clinical competence of nursing students have been developed, such as the bedside test, the Bedside Oral Exam (BOE) (Andersson et al., Citation2013; Athlin et al., Citation2012) and Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCE) (Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013).

Most studies in the field of graduating nursing students’ exit exams originating from the USA (e.g. Smith et al., Citation2019; Stonecypher et al., Citation2015) have focused on prelicensure exams and how they may improve students’ possibilities of passing the registration exams, such as the National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN). It has been indicated that first-time success rate on the NCLEX-RN exam has significant implications for students, faculty and schools of nursing. Many nursing programs utilise standardised exit exams to quantify student success on knowledge of nursing concepts and to prepare the students for success on the NCLEX-RN. The predictors that indicate success need to be identified early in the study path so that support and remediation programs can be provided to those at risk of failure. There have been identified some factors that may affect to success in NCLEX-RN examination such as academic performance in prenursing courses. Non-academic factors such as demographics, anxiety, stress and motivation can also impact nursing student success (Moore et al., Citation2021). The use of exit exam vary between countries. There is no common understanding what contents the exit exams should include or what kind of instruments should be used. This integrative review addresses the need for a comprehensive understanding of evaluation instruments that have been used globally in the exit exams of graduating nursing students. A comprehensive analysis of graduating nursing students’ exit exams will allow HEIs to create summative evaluation processes. It is anticipated that this integrative review of the literature will enable the systematic identification of exit exams. The aim of this review was to identify and describe the instruments used in undergraduate nursing students’ exit examination.

Methods

Design

An integrative review allows for the combination of findings from different research designs. Integrative reviews are also appropriate for studies in which the phenomenon is not well known (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). This review was conducted following the five stages used in the integrative review methodology by Whittemore & Knafl (Citation2005): (1) identification of the problem, (2) literature search, (3) data evaluation, (4) data analysis and (5) presentation of the results. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method was followed to ensure the correct reporting of the search results (Page et al., Citation2021).

Identification of the problem

To identify the problem, the following research questions were formulated:

What evaluation instruments have been used in undergraduate nursing students’ exit exams?

What content has been assessed in undergraduate nursing students’ exit exams?

Literature search

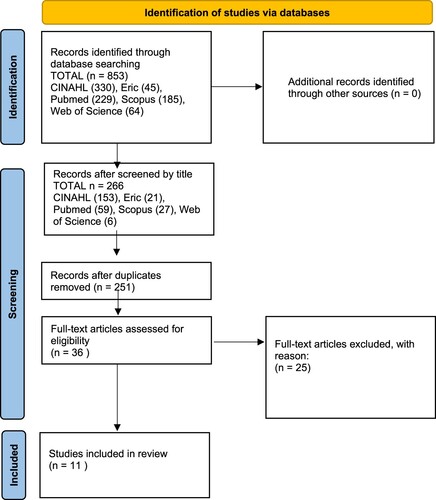

A systematic search of five () databases was conducted, including Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL Complete), The Education Resource information Center (ERIC), PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. The systematic search was first conducted in June 2020 and updated in October 2021. The data search was conducted by using the following keywords, their synonyms and MeSH terms, using Boolean operators: ‘nursing student*’ OR ‘nursing education’ OR ‘student nurs*’ OR ‘undergraduate nurs* student*’ OR ‘students, nursing’ AND ‘final exam*’ OR ‘final test* OR ‘exit exam*’ OR ‘baccalaureate exam*’ OR ‘national exam*’ OR ‘licen* exam*’. The search terms were verified with a university information specialist. In addition, the reference lists of the retrieved articles were manually searched.

Figure 1 PRISMA diagram of literature search. From Page et al. (Citation2021).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) the study was focused on graduating nursing students, (b) the evaluation was concerned with the previous year's nursing studies, not a specific study course, (c) the study was peer-reviewed and (d) the study included the instrument used in the exit exam. Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: (a) the students were other than graduating nursing students, (b) the evaluation was in an early phase of students’ studies (other than last semester/year of study) and (c) the article was not peer-reviewed research. Due to the scarce number of studies concerning exit exams, no year limit was specified. The language was limited to Finnish or English.

The study retrieval comprised four phases: (1) the results of the database search led to 853 studies in total; (2) the titles were screened, and 266 studies were selected to be screened by their abstracts; (3) the duplicates were removed, leaving 251 studies in total; and (4) the 251 studies were screened by their full text. Ultimately, 36 studies were left after screening for eligibility because 25 studies were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Altogether, 11 studies were selected for full-text assessment by the authors (K.R. and J.V.) and synthesised (). The study selection process is also described in the PRISMA flow diagram () (Page et al., Citation2021). Refworks was used to record and manage the sources.

Table 1 Studies icluded in the review.

Data evaluation

A quality assessment was conducted on the selected studies (n = 11) using the appraisal tools of the Joanna Briggs Institute, JBI, (Citation2017), and the studies were scored according to these criteria (). The quality appraisal was conducted to ensure that the most methodologically sound studies were represented in the aggregation, integration and synthesis of the primary findings (Lewin et al., Citation2015).

The quality appraisal was first conducted by the authors (K.R. and J.V.) independently. A consensus was achieved through discussion and by using the quality appraisal tool with the answer options ‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘unclear’. The quality of the studies was generally good, but there were some variations between the studies (). The scale for the appraisal scores of the studies varied depending on how many of the criteria were applicable to the study. The quality scores varied from 2/4–3/3 to 6/7–7/10. None of the selected studies were excluded from the quality assessment phase because the research group considered the quality scores adequate.

Data analysis

The systematic process was followed to identify included papers. These papers were appraised using JBI guidelines, then data were extracted and analysed according to recommendations of Whittemore & Knafl (Citation2005). According to Whittemore & Knafl (Citation2005), the first phase of data analysis is data reduction, which involves the determination of an overall classification system for managing data from diverse methodologies. The general information of the studies was tabulated, including the authors, year, country of publication, purpose, design, participants, data collection, analysis and quality appraisal (). The next phase, following Whittemore & Knafl (Citation2005), is data display, which involves an iterative examination of data displays of primary source data to identify patterns, themes or relationships. The data concerning the first research question are tabulated in . A qualitative content analysis, following Elo & Kyngäs (Citation2008), was selected to analyse the second research question. In the data comparison phase, the content used in the exit exams was identified and collated using the original expression stated in the article. After the original subjects were collected and collated, they were analysed so that any similar content could be identified and categorised according to Elo & Kyngäs (Citation2008). The final phase of the data analysis comprised conclusion drawing and verification (Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005). Subjects categorised as having similar content were classified as items. Items were then combined into categories that unified the content, followed by synthesis into the main categories ().

Table 2 Description of the instruments used in exit exams.

Table 3 The contents of evaluating instruments used in exit exams.

Presentation of the results

General description of the studies

Altogether, 11 studies were chosen for this review (). All the studies were original research articles () that were published between 2005 and 2019. The studies originated from the following countries: Australia (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), Slovakia (n = 1), Sweden (n = 4) and the USA (n = 4).

Instruments used in exit exams

Eleven different instruments were identified in this review of undergraduate nursing students’ exit exams (). Nine instruments evaluated theoretical competence (Alameida et al., Citation2011; Andersson et al., Citation2013; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Forsman et al., Citation2019; Frith et al., Citation2005; Gurkova et al., Citation2018; Hobbins & Bradley, Citation2013; Jacob et al., Citation2019; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013; Presti & Sanko, Citation2019; Yates & Sandiford, Citation2013) and two instruments evaluated clinical competence (Andersson et al., Citation2013; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013).

The theoretical instruments included Adaptive Quizzing (Presti & Sanko, Citation2019), the Assessment Technologies Institute (ATI) RN Comprehensive Predictor (Alameida et al., Citation2011; Yates & Sandiford, 2019), an electronic survey (Jacob et al., Citation2019), the Health Education Systems Incorporated Exit Exam (HESI) (Frith et al., Citation2005), the Mosby assess test (Frith et al., Citation2005), the Nursing Student Clinical Performance Competence Scale (NSCPES) (Gurkova et al., Citation2018), the National Swedish Clinical Final Examination (NCFE) (Andersson et al., Citation2013; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Forsman et al., Citation2019; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013), the Nurse Professional Competence Scale (NPC) (Forsman et al., Citation2019) and the Pre-Licensure Exam (Hobbins & Bradley, Citation2013).

The theoretical exams were mainly structured questionnaires with multiple-choice answers utilising objective assessment (Alameida et al., Citation2011; Frith et al., Citation2005; Gurkova et al., Citation2018; Hobbins & Bradley, Citation2013; Presti & Sanko, Citation2019; Yates & Sandiford, Citation2013). In addition, along with the NCFE theoretical assessment, a self-assessment instrument (NPC) was used as an indicator of student's professional growth (Forsman et al., Citation2019). At least two standardised tests, The HESI exit exam (Frith et al., Citation2005; Hobbins & Bradley, Citation2013) and the ATI RN tests (Alameida et al., Citation2011; Yates & Sandiford, Citation2013) were identified. These instruments are both validated, standardised exams that have been widely used as exit exams (Alameida et al., Citation2011; Yates & Sandiford, Citation2013). Reporting of the validity and reliability of the identified instruments varied (). For example, the validity and reliability of the NSCPES were tested in the current study and in previous studies (Gurkova et al., Citation2018). Reliability and validity were poorly reported for the Mosby assess test (Frith et al., Citation2005) and Adaptive Quizzing (Presti & Sanko, Citation2019).

Two clinical instruments were identified: the BOE and the OSCE (Andersson et al., Citation2013; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Forsman et al., Citation2019; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013). The clinical exams were used together with the theoretical exam (NCFE). Together with the NCFE, either OSCE or BOE was used as a clinical assessment method (Andersson et al., Citation2013; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013). In the NCFE, the clinical assessment (i.e. the BOE or the OSCE) was performed after the theoretical part of the exam, and each student was examined separately by an observer using a clearly structured assessment (Andersson et al., Citation2013; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Forsman et al., Citation2019; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013). The OSCE has a high degree of standardisation. While the validity and reliability of the clinical assessment tools have been tested by internal and external groups of experts, further research is needed (Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013).

Exit exams’ content

The content of the exit exams was described in 10 of the 11 studies included in this review () (Alameida et al., Citation2011; Andersson et al., Citation2013; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Forsman et al., Citation2019; Frith et al., Citation2005; Gurkova et al., Citation2018; Hobbins & Bradley Citation2013; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013; Presti & Sanko, Citation2019; Yates & Sandiford, Citation2013), and the descriptions of the content varied. The content of these exit exams was evaluated and defined according to nine main categories: (1) nursing knowledge and skills across the lifespan, (2) areas of nursing, (3) scientific knowledge, (4) nursing process and documentation, (5) fundamental care, (6) quality of nursing, (7) ethics andegislation of nursing, (8) patient encounter and education and (9) leadership and development (). These main categories were further divided into categories and items, which are narratives that describe the analysis unit. The results showed that the content used in undergraduate nursing students’ exit exams formed a holistic perspective of nursing.

The most identified and described main category was nursing process and documentation, which was mentioned in nine studies and seven instruments (Alameida et al., Citation2011; Andersson et al., Citation2013; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Forsman et al., Citation2019; Gurkova et al., Citation2018; Hobbins & Bradley Citation2013; Presti & Sanko, Citation2019; Yates & Sandiford, Citation2013). The ethics and legislation category were described in six studies and six instruments (Alameida et al., Citation2011; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Forsman et al., Citation2019; Frith et al., Citation2005; Gurkova et al., Citation2018; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013). The other content appeared similarly in the studies, varying from four to five studies in each items. The category that appeared the least often was leadership and development (three studies) (Athlin et al., Citation2012; Forsman et al., Citation2019; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013). Quality of nursing was described in a few instruments (Alameida et al., Citation2011; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013), although this main category also contained patient safety and safe medication.

Discussion

Main results

The main finding was that the exit exams in undergraduate nursing education vary considerably in different countries and educational institutions, although the competence requirements are mainly similar internationally (EFN, Citation2015). Additionally, the requirements preceding nursing registration vary in different countries, which may affect the existence of exit exams. Some countries (e.g. the USA) place greater significance on using exit exams because of the registration process after graduation (Alameida et al., Citation2011; Frith et al., Citation2005; Presti & Sanko, Citation2019; Yates & Sandiford, Citation2013). These exit exams play a major role in the preparedness of graduating nursing students participating in the NCLEX-RN; therefore, many educational organisations have implemented standardised testing using platforms to better prepare students for success on the NCLEX-RN (Alameida et al., Citation2011; Frith et al., Citation2005; Presti & Sanko, Citation2019; Stonecypher et al., Citation2015; Yates & Sandiford, Citation2013). This explains the higher number of exit exams in the USA than in Europe. According to Hobbins & Bradley (Citation2013), in Canada, the use of exit exams is lower than in the USA and there is no regularly used standardised exit exam model.

Nursing students’ competence consists of several components, yet most exit exams (Alameida et al., Citation2011; Frith et al., Citation2005; Gurkova et al., Citation2018; Hobbins & Bradley, Citation2013; Jacob et al., Citation2019; Presti & Sanko, Citation2019; Yates & Sandiford, Citation2013) evaluate only theoretical competence, which can lead to a lack of a broader assessment of competence. These theoretical instruments have different levels of standardisation. However, competence also covers skills, attitudes and values, which, along with critical thinking skills (Jacob et al., Citation2019), should also be considered when developing exit exams (Andersson et al., Citation2013; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Forsman et al., Citation2019; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013). However, a minority of HEIs use clinical exams (Andersson et al., Citation2013; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Forsman et al., Citation2019; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013), which may undermine the overall assessment of students’ competence. The more common use of theoretical exams may be due to their ease of implementation.

The evaluation of students may be challenging in clinical exams because there are no standardised and validated tools for clinical assessment. Andersson et al. (Citation2013) revealed that in the Swedish model of a BOE and an OSCE (Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013), the students were critical of the fairness of the exams. The BOE was different for each student depending on the caring situation. Due to this inconsistency, it has been proposed that an objective assessment should be further developed and implemented (Andersson et al., Citation2013; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Forsman et al., Citation2019; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013). Gurkowa et al. (Citation2018) revealed that, even if an NCSPE is useful for a summative evaluation, nursing students would benefit from having more complex assessment methods, and a valid and reliable tool may allow an objective evaluation of nursing student performance in clinical settings. The BOE and OSCE clinical exams (Andersson et al., Citation2013; Athlin et al., Citation2012; Forsman et al., Citation2019; Mårtensson & Löfmark, Citation2013) are more complex to implement and require significant teacher resources than theoretical exams.

According to Mårtensson & Löfmark (Citation2013), a single evaluation method cannot assess all domains of students’ knowledge and skills. Therefore, a variety of evaluation methods are required in nurses’ education. These findings support the development of clinical exams in virtual environments (e.g. virtual simulations or virtual games) to assess students’ clinical competence. Useful evaluation methods could be exams that utilise digitalisation to evaluate students’ clinical competence. There have been good learning results from the use of virtual games in nursing education (Kinder & Kurtz, Citation2018; Koivisto et al. Citation2016). Clinical exams implemented in virtual environments allow for an objective assessment. Additionally, the Covid-19 pandemic and students’ heterogeneity demand different kinds of digital solutions for nursing education to promote students’ competence and progress in their studies.

The content evaluated in the exit exams of this review covered nurses’ competence from a holistic nursing perspective. The main categories () comprised the scientific knowledge of nursing and its related sciences and covered all areas of nursing across the human lifespan. Although the descriptions of the content in the exit exams varied, this review identified that the main content areas of nursing education, as defined by the EFN (Citation2015), are similar globally, regardless of the HEI. Having similar content globally creates a uniform basis for the development of exit exams.

This integrative review demonstrated that, in addition to the USA and Sweden, quite a few countries have reported using exit exams. This may be because there are no standardised exit exams in use in educational institutes or because all HEIs have not reported the use of them. The overall reliability and validity were quite poorly reported, which should be considered when assessing the results. The expectations for clinically ready graduating nursing students are high. Considering the criticality of patient safety matters, it is important that HEIs have standardised exit exams in use to guarantee their students’ competence and quality of care.

Ethics, strengths and limitations of this review

This review followed the guidelines for research ethics (TENK, Citation2012) to ensure honest and ethically sustainable results’ reporting. The search terms were modified by an information specialist and the co-authors before the search of the relevant studies. Preliminary searches were conducted before the final search. The studies included were assessed by the authors (KR and JV) to ensure the inclusion of valid studies. A thorough literature search was conducted to enhance the rigour of the review, and it was evaluated in phases (Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005). To enhance authenticity, attention was paid to the reporting phase of this review. Although the studies included in this review originated from different places around the world, the review results can be considered generalisable in terms of the content and instruments used for exit exams in nursing education globally. Due to the scarce number of studies that met the inclusion criteria, data analysis was one of the challenges of this review.

Impact paragraph

Graduating nursing students’ exit exams vary globally in HEIs, with most using theoretical exams. Greater emphasis should be placed on developing more comprehensive exams, including objectively assessed clinical testing, and virtual learning environments should be implemented more broadly.

Conclusion

There is considerable variability in existing exit exams which has implications for nursing education, research and policy makers. The use of exit exams varies extensively in different educational institutions. The findings of this review suggest that HEIs should develop and implement more comprehensive evaluation methods and instruments to ensure students’ competence upon graduation. The results are important for developing exit exams in nursing education because they indicate that summative evaluation is needed. Clinical exams have been used marginally in HEIs, which should be considered when implementing new exams. Digitalisation (e.g. virtual environments) could be one solution for offering objective assessment, validity and cost-effectiveness.

Authorship contribution statement

Conception and design: KR, JMK, EH, acquisition of data: KR, JV analysis of data: KR, JMK, JV, EH, drafting the manuscript: KR, revising manuscript critically: KR, JMK, JV, EH.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alameida, M., Prive, D., Davis, A., A, H., Landry, L., Renwanz-Boyle, A., & Dunham, M. (2011). Predicting NCLEX-RN success in a diverse student population. Journal of Nursing Education, 50(5), 261–267. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20110228-01

- Andersson, P., Ahlner-Elmqvist, L., Johansson U-B, M., Larsson, M., & Ziegert, K. (2013). Nursing students’ experiences of assessment by the Swedish National Clinical Final Examination. Nurse Education Today, 33(2013), 536–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2011.12.004

- Athlin, E., Larsson, M., & Säderhamn, O. (2012). A model for a national clinical final examination in the Swedish bachelor programme in nursing. Journal of Nursing Management, 20(2012), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01278.x

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- European Federation of Nurses Associations. (2015). EFN Guideline for the implementation of Article 31 of the Mutual Recognition of Professional Qualifications Directive 2005/36/EC, amended by Directive 2013/55/EU. http://www.efnweb.be/wp-content/uploads/EFN-Competency-Framework-19-05-2015.pdf.

- Forsman, H., Jansson, I., Leksell, J., Lepp, M., Andersson, C. S., Engström, M., & Nilsson, J. (2019). Clusters of competence: Relationship between self-reported professional competence and achievement on a national examination among graduating nursing students. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(2020), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/Jan.14222

- Frith, K., Sewell, J., and Clark, P., & J, D. (2005). Best practices in NCLEX-RN readiness preparation for Baccalaureate student success. Nurse Educator, 23(6), 322–329.

- Gurkova, E., Ziakova, K., Zanovitová, M., Gibriková, S., & Hudáková, A. (2018). Assessment of nursing student performance in clinical settings – usefulness of rating scales for summative evaluation. Central European Journal of Nursing and Midwifery, 9(1), 791–798. https://doi.org/10.15452/CEJNM.2018.09.0006

- Hobbins, B., & Bradley, P. (2013). Developing a prelicencure exam for Canada: An International collaboration. Journal of Professional Nursing, 9(2), 48–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.06.005

- International Council of Nurses, ICN. (2012). Position statement of patient safety. https://www.icn.ch/nursing-policy/icn-strategic-priorities/patient-safety.

- Jacob, E., Duffield, C., & Jacob, A. M. (2019). Validation of data using RASCH analysis in a tool measuring changes in critical thinking in nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 76(2019), 196–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.02.012

- JBI. (2017). The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies. http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.

- Kinder, F. D., & Kurtz, J. (2018). Gaming strategies in nursing education. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 13(4), 212–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2018.05.001

- Koivisto, J.-M., Multisilta, J., Niemi, H., Katajisto, J., & Eriksson, E. (2016). Learning by playing: A cross-sectional descriptive study of nursing students’ experiences of learning clinical reasoning. Nurse Education Today, 45, 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.06.009

- Lejonqvist, G.-B., Eriksson, K., & Meretoja, R. (2016). Evaluating clinical competence during nursing education: A comprehensive integrative literature review. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 22(2016), 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12406

- Lewin, S., Glenton, C., Munthe-Kaas, H., Carlsen, B., Colvin, C. J., Gülmezoglu, M., & Rashidian, A. (2015). Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: An approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Medicine, 12(10), e1001895. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001895

- Mårtensson, G., & Löfmark, A. (2013). Implementation and student evaluation of clinical final examination in nursing education. Nurse Education Today, 33(2013), 1563–1568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.01.003

- Moore, L., Goldsberry, J., Fowler, C., & Handwerker, S. (2021). Academic and nonacademic predictors of BSN Student Success on the HESI Exit Exam. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 39(2021), 570–577. https://doi.org/10.1097/CIN.0000000000000741

- NCSBN. (2020). National Council of State Boards of Nursing. https://www.ncsbn.org/boards.htm.

- Page, M.J., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Presti, C., & Sanko, R., & S, J. (2019). Adaptive quizzing improves End-of-Program Exit Examination Scores. Nurse Educator, 44(3), 151–153. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000000566

- Smith, G., Ellen, M., Dreher, H., & Schreiber, J. (2019). Standardized testing in nursing education: Preparing students for NCLEX-RN® and practice. Journal of Professional Nursing, 35(6), 440–446. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2019.04.012

- Spector, N., & Alexander, M. (2006). Exit exams from a regulatory perspective. Journal of Nursing Education, 45(8), 291–293. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20060801-01

- Stonecypher, K., Young, A., Langford, R., Symes, L., & Willson, P. (2015). Faculty experiences developing and implementing policies for exit exam testing. Nurse Educator, 40(4), 189–193. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000000152

- The Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity (TENK). (2012). Responsible conduct of research and procedures for handling allegations of misconduct in Finland. Helsinki, 2013. https://tenk.fi/en/research-misconduct/responsible-conduct-research-rcr.

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

- World Health Organization. (2020). State of the World´s Nursing Report 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/nursing-report-2020.

- Yates, L., & Sandiford, J. (2013). Community college nursing student success on professional qualifying examinations from admission to licensure. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 37(2013), 319–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920903530013