Abstract

Phenomenon:

In order to tackle the persistent rise of healthcare costs, physicians as “stewards of scarce resources” could be effective change agents, extending cost containment efforts from national policy to the micro level. Current programs focus on educating future doctors to deliver “high-value, cost-conscious care” (HVCCC). Although the importance of HVCCC education is increasingly recognized, there is a lag in implementation. Whereas recent efforts generated effective interventions that promote HVCCC in a local context, gaps persist in the examination of system factors that underlie broader successful and lasting implementation in educational and healthcare practices.

Approach:

We conducted a realist evaluation of a program focused on embedding HVCCC in postgraduate education by encouraging and supporting residents to set up “HVCCC projects” to promote HVCCC delivery. We interviewed 39 medical residents and 10 attending physicians involved in such HVCCC projects to examine HVCCC implementation in different educational and healthcare contexts. We held six reflection sessions attended by the program commissioners and educationalists to validate and enrich the findings.

Findings:

A realist evaluation was used to unravel the facilitators and barriers that underlie the implementation of HVCCC in a variety of healthcare practices. Whereas research activities regularly stop after the identification of facilitators and barriers, we used these insights to formulate four high-value, cost-conscious care carriers: (1) continue to promote HVCCC awareness, (2) create an institutional structure that fosters HVCCC, (3) continue the focus on projects for embedding HVCCC in practice, (4) generate evidence. The carriers support residents, attendings and others involved in educating physicians in training to develop and implement innovative HVCCC projects.

Insights:

Strategies to promote physician stewardship go beyond the formal curriculum and require a transformation in the informal educational system from one that almost exclusively focuses on medical discussions to one that also considers value and cost as part of medical decision-making. The HVCCC carriers propose a set of strategies and system adaptations that could aid the transformation toward a HVCCC supporting context.

Background

Controlling the growth of healthcare costs in the Netherlands, as well as many Western healthcare systems, poses a complex challenge. In search of solutions to control expenses, it is argued that physicians should become “stewards of scarce resources,Citation1,Citation2 extending the focus on cost savings from governmental policy or insurance companies to the micro level. Studies have shown that cost education positively changes students’ attitudes toward cost-conscious careCitation3 and that residents continue to work in a cost-conscious manner, after completion of medical training.Citation4 The focus on the future generation of doctors also builds on the notion that empowered learners could induce change by rethinking the system in which medicine is practiced and address local system issues by developing innovative projects in order to improve healthcare practices,Citation5–9 thus acting as change agents. Residency training is seen as the key to educate a new generation of doctors to provide high-value care while controlling costs.Citation5,Citation10 Therefore, several authorsCitation1,Citation2,Citation11,Citation12 promote the addition of a medical competency, referred to as “high-value, cost-conscious care” that teaches future doctors about resource stewardship, which has now been incorporated in several competency frameworksCitation3,Citation13,Citation14 and educational programs.Citation15,Citation16 HVCCC is about preserving “the delivery of interventions that provide good value”Citation17(p175) by eliminating marginally effective healthcare and other sources of waste (“low value care”) and delivering health care that provides benefits that commensurate costs (“high value care”).Citation17

Although the importance of education to address these topics is increasingly recognized, there is a lag in implementation.Citation18–20 Empirical studies show that medical residents list time pressure,Citation6,Citation21 medical uncertainty,Citation21,Citation22 fear of missing something,Citation6 and fear of malpractice liabilityCitation22 as barriers to resource stewardship. Furthermore, the current teaching environment may pose barriers to improving high-value care caused by a hierarchy in teams,Citation6,Citation9,Citation18 a lack of clinical role modelsCitation3 and teachers that punish “sins of omission” disproportionately.Citation2,Citation5 Literature suggests that strategies to promote physician stewardship go beyond improving HVCCC competence and also demand alignment of external factorsCitation9,Citation23 to foster HVCCC delivery and the elimination of barriers that inhibit them.Citation24,Citation25 Building a supportive environment is considered a crucial element in order to effectively teach future physicians to deliver HVCCC.Citation23 However, gaps persist in the examination of contextual factors, as most studies only provide evidence of program effectiveness for one intervention in one specific context.Citation23,Citation24

The objective of this study was to provide innovative strategies on HVCCC implementation, by conducting a system analysis that takes the context in which HVCCC needs to operate into account. We examined how contextual barriers triggered physician behavior in relation to resource stewardship, thus identifying what mechanisms underlie problematic implementation of HVCCC in educational and medical practice. Moreover, we translated this contextual analysis of underlying mechanisms into a cohesive set of strategies that drew on the potential of existing structures to foster HVCCC implementation to transform HVCCC barriers into what we coined “HVCCC carriers.” We saw each carrier as a strategy to foster implementation of HVCCC by drawing on existing structures to overcome barriers.

Methods

Design

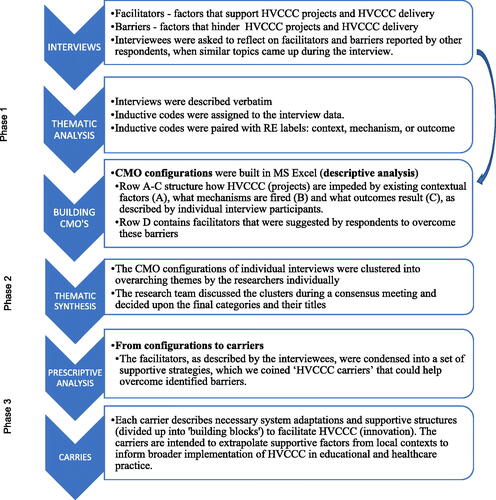

This study examined contextual factors that affected the implementation of HVCCC using Realist Evaluation (RE). RE goes beyond an intervention-focused evaluation and instead focuses on answering “what works, for whom and under which circumstances and how?”Citation26 RE assumes that a single intervention can produce different outcomes when it is introduced in different contexts. This follows from underlying mechanisms that “fire” under specific contextual conditions.Citation27 Mechanisms affect the outcomes of an intervention through the reasoning of individuals involved and the responses of these individuals to the intervention.Citation28 RE aims to expose the facilitating and hindering mechanisms by untangling causal processes in so called Context-Mechanism-Outcome (CMO) configurations, which are “descriptions of causal pathways of how programs activate mechanisms in specific conditions to cause changes in behaviors or events”).Citation28(p1116) The contextual analysis informed the formulation of HVCCC carriers. Each carrier is a strategy to foster implementation of HVCCC by drawing existing structures to overcome barriers. summarizes how data collection and data analysis were guided by the Realist Evaluation approach.

Setting

This study was conducted in teaching hospitals across the Netherlands who participated in the Bewustzijnsproject. The Bewustzijnsproject, roughly translated as “the consciousness project,” is a Dutch initiative that guided the implementation of HVCCC in postgraduate education in the Netherlands between 2015 and 2018. The Bewustzijnsproject gathered existing HVCCC educational tools and initiatives in order to assist fellowship programs to implement HVCCC curricula. Among these educational approaches, the Bewustzijnsproject encouraged motivated medical residents to set up new HVCCC innovative practices, referred to as “HVCCC projects,” which resulted in over 200 resident-led HVCCC projects. Residents could set up a project to address issues they encounter in daily practice that hinder HVCCC delivery. Such projects enabled residents to experience how they could promote quality or efficiency in healthcare practices. The idea was that developing and running a project would help residents gain real-world experience in guiding change processes in healthcare organizations, such as the importance of gaining support from stakeholders and understanding organizational processes, that could facilitate or hinder the implementation of the HVCCC project.

Participants

We conducted semi-structured interviews between January and June 2018 with 49 respondents that were involved in initiating (residents, n = 39) or coordinating (attending physicians, n = 10) a total of 41 HVCCC projects. Respondents were recruited using purposive sampling. The research team strived for a representative sample that included all eight educational regions in the Netherlands, taking into account the potential impact of educational context. In order to select relevant projects for this study, the project plans of the HVCCC projects were screened to select only those that addressed one or more components of HVCCCCitation17 as follows: (1) a focus on the reduction of low-value care, (2) a focus on the delivery of good-value care; (3) a focus on raising cost consciousness and/or (4) a focus on reducing healthcare costs. In addition, the researchers selected projects that were currently running, as opposed to projects that had already been completed, in order to minimize the risk of memory bias, as the interviews were focused on details of the implementation process.

Data collection

The interviews were either conducted or supervised by trained qualitative interviewers GLB and MM. In addition, three research interns, trained in qualitative interviewing during their master’s program, conducted the interviews. Participants from 18 different hospitals were interviewed, with most respondents working at university medical centers (n = 35) and relatively fewer respondents working at local teaching hospitals (n = 14).

The goal of the interviews was to gain a better understanding of how HVCCC projects operated in local contexts. During each interview, respondents were asked to describe factors that were supportive to the execution and implementation of HVCCC projects (facilitators) and factors that hindered HVCCC projects (barriers). A semi-structured interview approach was used to probe contextual factors and mechanisms that lead to facilitation or impediment of the HVCCC project. Such probing questions included: what factors affect the project? (context), who is involved? (context), in what ways does [factor] affect you/your project? (mechanism), how does [factor] affect the outcomes of your project? (outcome). The same approach was used to examine what factors facilitate or hinder HVCCC delivery in daily practice.

The duration of the interview was approximately 45 to 60 minutes. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Described facilitators and barriers and their impact on HVCCC were summarized and sent to the interviewee for member check, in order to verify whether inferences made by the researcher regarding facilitating or hindering factors and their effects on HVCCC were correct. Interviewees were asked to supply changes and additions via email. Summaries and subsequent analyses were adjusted accordingly.

Data analysis

Phase 1 – Identifying potential contexts, mechanisms and outcomes

Recruitment, data collection, thematic analysis and CMO configurations were concurrent activities. Each interview transcript was analyzed by the interviewer to identify contexts, mechanisms and outcomes and produce CMO configurations. Initial CMO configurations (example as Supplement) were drafted by the research interns in collaboration with one of the authors GLB or MM. The CMO configurations were presented to respondents in follow-up interviews in order to enrich the configurations.

Phase 2 – Thematic synthesis

The researchers involved in data collection individually clustered the CMO configurations into themes. The researchers shared clusters during a consensus meeting and agreed upon the final clustering. By cross-referencing findings from individual study participants within each of the clusters, the researchers were able to identify mechanisms that explained causal links between contexts and outcomes.

Phase 3 – HVCCC carriers

Besides using a realist evaluation to unravel how HVCCC projects are hindered by mechanisms (a descriptive analysis), we also used these insights to outline the contextual conditions that are needed to support HVCCC innovation (a prescriptive analysis). A realist evaluation is normally used to unravel causal pathways of contexts that fire underlying mechanisms through which outcomes are produced. Whether or not these mechanisms operate depends on supportive or disabling contexts.Citation27 We used identified facilitators to define supporting contexts that fire mechanisms that are expected to produce desirable outcomes by overcoming barriers to HVCCC. We describe these supporting strategies in so called HVCCC carriers. Each carrier delineates a set of strategies to support residents as HVCCC change agents. Findings were discussed during six reflection sessions attended by the project commissioners and educationalists involved in the Bewustzijnsproject to collect feedback and validate the carriers. Input from the reflection session was documented using detailed field notes that were transcribed after the session. We operationalized each carrier into several building blocks, in order to translate them into practical tools and processes.

Reflexivity statement

We took multiple steps to mitigate the potential biases and subjectivity that could impact the analysis of qualitative data. The CMO configurations were drafted by the research interns in collaboration with one of the authors GLB or MM. The research interns had no prior experience in medical education, and the authors (GLB and MM) were experienced qualitative researchers with prior training and experience researching challenges in contemporary medicine and the financial organization of the Dutch healthcare system. The researchers were not physicians and were not employed by a clerkship department, which provided distance from the data. During the analysis process, the researchers met regularly to develop an iterative and shared conceptual understanding of the data. Finally, six reflection sessions with the project commissioners and educationalists involved in the Bewustzijnsproject were organized to collect feedback from experts in the field of medical education and to validate the HVCCC carriers.

Results

This section describes four high-value, cost-conscious care carriers. A carrier is a strategy to foster implementation of HVCCC by drawing existing structures to overcome barriers. The carriers are: (1) continue to promote HVCCC awareness, (2) create an institutional structure that fosters HVCCC, (3) continue the focus on projects for embedding HVCCC in practice, and (4) generate evidence. The carriers are informed by insights from the CMO configurations that illustrate how contextual factors currently impede the implementation of HVCCC in educational and healthcare practice. Each carrier consists of multiple building blocks. provides an overview of the carriers and building blocks.

Table 1. An overview of HVCCC carriers and building blocks.

HVCCC carrier I: Continue to promote HVCCC awareness

Physicians need insight in how to deal with a care practice that asks for cost considerations where there used to be mostly medical discussions. Building on the CMO configurations depicted in , promoting HVCCC awareness was identified as an important first step to induce a shift in thinking and embed considerations of HVCCC in healthcare delivery.

Table 2. Contexts and mechanisms that lead to a lack of awareness and deliberate decision-making.

The four building blocks of Carrier I described below outline facilitators mentioned by respondents to promote HVCCC awareness and implement deliberate decision-making processes in which high-value care interventions are selected and sources of inefficiency are eliminated.

Carrier I – Building block 1: Build a shared understanding of HVCCC

In order to induce a shift in thinking, it is important to develop a shared vision on what HVCCC entails. Respondents noted that the definition of HVCCC should emphasize that delivering HVCCC does not impose constraints on medical decision-making, nor does it have a limited focus on costs alone. Making HVCCC choices requires physicians to justify the value of selected interventions in which invested resources result in high-value care.

[We need to emphasize that] physicians are free to order any diagnostic or therapeutic option, as long as they have critically thought about the clinical indication and necessity [of the medical intervention] and as long as physicians are aware of the fact that each medical intervention costs money. Not to say that spending money is a problem, but you should be able to justify why you made a certain medical choice.A (Attending physician)

Carrier I : Building block 2: Increase knowledge about costs

The vision of HVCCC outlined in Building Block 1 emphasizes the need to justify the value of resources spent. Physicians first consider factors including patient preferences, effectiveness of interventions and guidelines before costs are taken into account, thus avoiding the association of HVCCC as merely a cost control measure. Respondents that were involved in HVCCC projects similarly indicated that reducing costs was never the primary goal of their HVCCC project, but a desirable by-product. Nevertheless, many respondents considered cost education crucial to increase physicians’ cost awareness and foster more diligent use of resources. A resident mentioned that cost awareness is a temporary, but necessary tool to justify the value of selected interventions. This resident noted that,

Ideally physicians consciously reflect on value in everyday practice. Since this is currently not the case, cost awareness can provide an impulse to justify value.

Initiatives to educate trainee doctors about healthcare costs included the development of an online module to teach trainee doctors about the financial structure of the healthcare system. The project initiators argued that this provides an essential starting point for HVCCC projects to truly have an impact on costs. Furthermore, an attending and a medical resident organized cost quizzes. They observed that the introduction of a quiz game engaged trainees and triggered a sense of competition, even though there was no actual prize besides winning.

Carrier I – Building block 3: Provide quantitative feedback

The second building block highlights the role that education could play in raising cost awareness, thus fostering a sense of urgency for delivering HVCCC. Some respondents took it one step further by suggesting that personal feedback on resources spent could trigger personal ownership and involvement in delivering HVCCC. One resident describes:

It would be interesting to receive a monthly overview that shows how much money I spent on supplementary tests (…) honestly, I have no idea. I may wrongly assume that I provide good care for a good price.

Providing feedback to physicians (in training) on the effects of medical decisions could replace what physicians think they do with substantiated insight into what they actually do based on the data of ordering behavior and (costs of) resources used. The quote below highlights the added value of using “real” data in order to achieve this goal.

Traditional education [focuses on]: “you have to do this in this way,” whereas [teaching with personal feedback] is about: “these are the lab tests that you ordered, for you to evaluate”(.) [Traditional education misses out on] really involving people (.) making [ordering behavior] people’s own “problem” (medical resident)

The use of “real data” and other facilitators related to this building block are summarized in Appendix C.

Carrier I – Building block 4: Promote reflective decision-making

So far, the building blocks described strategies to raise awareness of healthcare costs and resources spent. Indeed, several respondents mistook the Bewustzijnsproject, the “consciousness project,” as being a “cost-consciousness project,” which would suggest that raising cost-awareness is the end goal. Nonetheless, in discussing the relationship between cost-awareness and HVCCC, many respondents described cost-awareness as a precursor to HVCCC delivery. What is needed to move from one step to the next is critical reflection. Respondents repeatedly noted that HVCCC essentially revolves around continuously reflecting on medical necessity and appropriateness of interventions, by asking questions such as: “what does this patient need?” and “does this test change management?” One attending describes:

It simply has to be part of every single consideration: (.) in considering what diagnostic tests to order, in preparing your working day at the outpatient clinic.

In addition to internal reflection, respondents suggested that consulting clinical guidelines could support the determination of medical necessity and appropriateness of care.

HVCCC carrier II: Create an institutional structure that fosters HVCCC

Building on the CMO configurations depicted in , a supportive institutional structure is needed to create a foundation for the other HVCCC carriers.

Table 3. Contexts and mechanisms that lead to a lack of room for HVCCC in the information educational system.Footnote 1

The building blocks of carrier II describe strategies to embed HVCCC in institutional structures, in order to promote HVCCC awareness (carrier I) and enable residents to set up innovative HVCCC practices (carrier III).

Carrier II – Building block 1: Install HVCCC ambassadors

Installing HVCCC ambassadors that promote HVCCC awareness (Carrier I) was frequently mentioned as an important facilitator for the initiation of new HVCCC projects by residents. Respondents think that attendings who are personally interested in HVCCC are most suitable to adopt a role as HVCCC ambassador. Ambassadors actively incorporate HVCCC in the training of residents and teach residents about the importance of HVCCC. Residents mentioned that this exposure to HVCCC during residency training helps them to identify which processes can be improved to promote HVCCC. In addition, ambassadors motivate medical residents who are interested in HVCCC and help them to translate their ideas to improve HVCCC into concrete actions. An attending describes how ambassadors can act as catalysts for new HVCCC projects.

It is important to have ambassadors (.) I play a large part in that. I have encouraged or triggered residents by suggesting: “why don’t you?” and then have them make the next step. (.) But most of all, it is about creating awareness among residents. I do not direct them, they have to do it [run a HVCCC project]. But I do catalyze their thinking process (.) [So] you need people that propagate this topic. (Attending physician)

A list of seven identified HVCCC ambassador traits is provided in Appendix D.

Carrier II – Building block 2: Promote open discussion about HVCCC

As illustrated in Building Block 1, a HVCCC ambassador can be valuable in the creation of a supportive institutional structure that fosters the continuous promotion of HVCCC. Eventually, all physicians (especially those with a supervisory role) should be involved in the creation of a reflection-supporting structure to embed HVCCC in the education of current and future medical residents. Supervisors can help residents to reflect on medical necessity during interaction moments, including grand-rounds discussions, multidisciplinary deliberations and shift transfers. The quote below illustrates how supervisors who encourage reflection can help residents break patterns of over-ordering tests, a frequently reported source of inappropriate and unnecessary care produced by inexperienced residents who try to increase medical certainty.

Whenever I was ordering lab tests, my attending asked me: “What are you going to do with the results?” If I could not justify the necessity of the lab order, my attending responded by saying: “Then you should not have ordered that test.” These questions encourage me to engage in self-reflection, by asking myself, “Is this test truly necessary?” (medical resident)

Besides bringing HVCCC into discussions regarding patient management, it is equally important to encourage residents to share their own observations. For example, a resident highlighted the importance of attendings inviting medical residents to share their ideas.

As a resident you see a lot, especially when you are just starting out (.) you wonder: “why does this department do it like this?” (.) “Is this the best way?” (.) [But] after a few months you will adopt conventional methods, because that is just the way we work around here (.) it is a shame to let those initial insights go to waste.

The quote describes how each internship brings residents into new departments and organizations that allow them to observe the effects of different procedures used. However, as another resident describes, the lack of experience and residents’ outsider status inhibits them to share their observations with others.

The hierarchy is a potential pitfall (.) the attending has way more experience, so you may start to question your own observations. (medical resident)

In order to benefit from residents’ outsider perspective, two medical residents and two attendings suggested to have attendings schedule meetings with residents to discuss their observations and ideas to improve HVCCC. In addition, it was suggested to invite residents to staff meetings, because these meetings could inform residents about challenges that the department faces (sources of possible HVCCC improvements) and pitch their ideas for projects to staff members.

HVCCC carrier III: Continue the focus on projects for embedding HVCCC in practice

The Bewustzijnsproject encouraged motivated residents to set up HVCCC projects in order to address issues they encounter in daily practice that hinder HVCCC delivery. Building on the CMO configurations depicted in , resources and tools are needed to support project-based working.

Table 4. Contexts and mechanisms that lead to tensions between high work demands and HVCCC innovation projects.

Table A1. Example context-mechanism-outcome configuration.

The building blocks describe tools and resources to sustain continuous cycles of HVCCC innovations. Each cycle provides insight into what works and what does not and facilitates discussions and reflections on lessons learned to generate ideas for new initiatives.

Carrier III – Building block 1: Facilitate motivated residents to develop HVCCC projects

Many residents described that the reservation of project hours could help address barriers posed by the current working and training environment that do not allow residents to run projects during working hours.

I have to multitask and that just does not work. I am most efficient when I can spend consecutive hours focusing on one project. [Now, I am continuously disrupted] by all kind of micro distractions, as other physicians probably are too. (medical resident)

We observed how residents currently maneuver these time constraints by working on projects in their free time and/or implementing HVCCC projects in outpatient clinic settings with relatively less demanding work schedules. The quote above highlights how project hours can temporarily discharge doctors from being approached for questions. Furthermore, project hours could help expand HVCCC projects from being exclusively planned and implemented in outpatient clinic settings, to more high-pressure clinical environments that might benefit the most from HVCCC improvements.

In addition to the reservation of project hours, matching residents to a project supervisor can support residents’ HVCCC projects.

I noticed (.) that if I [as a resident] work on this on my own, then this [project] reaches no one (.) In my opinion, pairing specialists and residents (.) [helps with] continuity (.) specialists’ involvement is also crucial for implementation in the long run, because they sort of propagate the culture from the top down, they speak from a position of authority.

The quote illustrates that sharing project responsibility between a resident and project supervisor from the permanent staff of a department could prevent project discontinuance after residents leave for another internship, a concern that several residents had. Furthermore, residents noted that specialists’ authority position opens certain doors that remain closed to residents, which can prove beneficial to the project when stakeholders need to be involved. Finally, a project supervisor can serve as resident’s contact person for project questions and feedback. The quote below illustrates how this can benefit the success and efficiency of a project.

[My supervisors] will guide me a bit by saying: “no, you are going in circles. This is not going anywhere. Try this and that and see what happens” (.) They know what they are talking about, how to run a change project. I learn a lot more from them than just trial and error on my own. (medical resident)

Carrier III – Building block 2: Provide the principles of project-based working

Besides offering project time and supervision (Building Block 1), it can be valuable to teach residents about principles of project-based working to guide HVCCC change processes. Most interviewed residents had no prior experience with project-based working. The quote below illustrates that medical residents may feel ill-equipped to run a project.

You have to do all kinds of things that have nothing to do with just patient care; you have to invite different stakeholders to the table, while you actually have no idea who to approach and how to arrange this. (medical resident)

Three principles for effective project work were mentioned during the interviews: conducting a problem analysis, establishing project- and outcome measures, and performing a stakeholder analysis.

First, it can be helpful to encourage residents during the preparation phase of the project to conduct a problem analysis. A problem analysis forces residents to analyze the problem that their project intends to address. Insight into the problem and its root causes can help draft an improvement plan that solves the problem effectively.

Second, explicating the goal of the project and monitoring its progress was suggested to guide a project toward its intended outcomes. An attending describes

At the start of a project residents have to think about: what is the underlying reason for setting up this project? What should come out of this project? When can the project be considered successful?

Monitoring project progress by means of process indicators with set deadlines enables supervisors and residents to discuss the progress of the project and adjust their approach in case of (unanticipated) setbacks.

Third, offering strategies to identify and involve stakeholders in a project was frequently described as an important determinant of successfully implementing HVCCC projects. A few residents who had prior experience in project work emphasized that stakeholder involvement is essentially about taking a bottom-up approach to change processes that helps lower the risk of delayed or discontinued projects due to resistance from stakeholders. Strategies that were listed to foster stakeholder involvement included the organization of a kickoff meeting or attendance to staff meetings that can be used to introduce a HVCCC project to stakeholders, explain its goals and thereby convince others of the relevance of the project and gain their support. Meetings provide the advantage of interaction with those who are involved or otherwise affected by the project and provides them with the opportunity to give input. In addition, some residents had discovered the importance of discussing and explicating roles and responsibilities to minimize negative impact of the project on others (e.g. an increase in workload or work complexity), thus prevent the project from going sideways.

[The project relocated measurement tasks from the clinicians to the laboratory] (.) the laboratory employees felt unsure about their role and responsbilities in this new situation: “what if I find out that the patient has significantly low or high blood pressure, do I have to find a doctor instantly?” (medical resident)

Appendix E contains a full list of stakeholder strategies.

Carrier III – Building block 3: Build a HVCCC platform

A couple of residents mentioned that building a HVCCC platform where residents can find information would help them in the process of preparing and executing a HVCCC project. The suggestion to build a HVCCC platform builds on the reported absence of any means to disseminate HVCCC projects, which causes residents to be unaware of other running HVCCC projects, even those that are implemented within the same hospital organization in which residents themselves work. The quote below describes that a platform could offer practical information about arranging for project funding and writing a project proposal. This information can prevent residents from feeling discouraged to set up projects because they do not know where to start and what is needed to get a project off the ground.

Residents are only incentivized to learn more about medicine. In order to conduct a HVCCC project, residents have to write proposal to apply for project funding. Residents have never done this and they might approach this process with some dread. Residents wonder: “How do write a proposal? Which subsidy fits my project? It might be helpful to build a national platform where residents can search for information about preparing and executing HVCCC projects (medical resident).

Some residents mentioned that a HVCCC platform can also serve as a source of inspiration by presenting HVCCC projects conducted by other residents. Moreover, one resident highlighted that this may offer the opportunity to implement HVCCC projects that have already proven to be successful in other contexts, which arguably increases the likelihood of the project being supported by others.

HVCCC carrier IV: Generate evidence

An underlying issue that came up repeatedly, with no means to resolve it, was the need to quantify effectiveness. The issue was frequently raised during reflection sessions with the program management team who had to indicate a return on investment of the Bewustzijnsproject. Furthermore, some interview respondents mentioned that they were expected to generate quantitative evidence of the effectiveness of their HVCCC project in a relatively short time-span. The need for an evidence-based approach runs counter to the tendency to favor action over a rigorous, planned approach described in the CMO configuration () accompanying the third HVCCC carrier. This finding resonates with the notion that quality programs need not adhere to the principles of evidence-based medicine. Auerbach et al.,Citation29 however, describe this as a common misunderstanding in quality improvement. They propose that like medical technologies, quality improvement interventions should undergo rigorous testing to determine whether, how, and where the intervention is effective. Indeed, measuring benefits and harms is central to HVCCC delivery in order to distinguish between high-value care and avoid use of low-value care interventionsCitation17 and not blind program initiators to potential harm to patients and squandering of resourcesCitation29 caused by HVCCC projects. Based on our analysis and the literature we suggest a fourth HVCCC carrier “generate evidence” in order to foster the implementation of HVCCC in a system that operates according to principles of evidence-based medicine, provided those do not assume an overly narrow definition of what counts as evidence.Citation30

Carrier IV – Building block 1: Identify the contexts and mechanisms that influence project outcomes

The adoption of a realist evaluation approach can help generate context-rich descriptions of how results are obtained to establish “what works, for whom and under which circumstances.” Such “contextualized evidence” can facilitate innovation in areas where there may be little existing evidence, improve chances of successful implementation and support dissemination of HVCCC practices to other contexts. Unlike randomized controlled trials that isolate the effects of interventions from the complex components of healthcare systems,Citation29 contextualized evidence incorporates the interactions between the system and the innovation needed to truly understand the mechanisms that underlie innovation outcomes.

A realist evaluation monitors the implementation process to identify contexts and mechanisms that explain how outcomes are generated. At the start of a realist evaluation, initial theories are developed that list potentially relevant contextual factors and mechanisms, which together form theoretical paths that describe how project outcomes might be produced. These initial theories can be formulated based on project expectations: “what do I wish to achieve with this project?” and “what do I consider to be relevant contextual factors in order to achieve the goal(s) of the project?” In addition, scientific literature can be consulted to identify contextual factors and mechanisms. Finally, theories can be discussed with peers, preferably individuals that have conducted similar interventions in the past. After candidate theories have been developed, the project is monitored to enrich and refine these theories to eventually produce context-rich descriptions of how HVCCC can be obtained in practice.

Carrier IV – Building block 2: Identify quantifiable variables

In order to generate evidence of project outcomes, it is helpful to define outcome measures at the start of a project. A set of questions to support project initiators to define outcome measures are listed below.

What are my expectations of the project outcomes? When do I consider my project to be successful?

What information is available to me? (Scientific literature, clinical guidelines, care quality indicators, existing measuring instruments, expertise of others [researchers, colleagues].

Which variables can be identified from the existing information?

Are these variables directly applicable to the project?

Can these variables be operationalized to fit the context of the study?

Carrier IV – Building block 3: Generate outcome scenarios to indicate potential HVCCC project impact

Study findings showed that respondents often struggled to measure effectiveness, especially on a short-term basis. Building scenarios, ex ante calculations of project outcomes based on hypothesized degrees of project effectiveness, could help bypass such barriers. Using the PICO system, residents could define the population, the intervention (HVCCC project), the comparison (current situation) and the outcome. The scenario outcome is framed as the expected outcome based on a hypothesized degree of effectiveness. For example: “the HVCCC project is expected to reduce the number of hospital readmissions in hospital X by 0.5%.” This outcome is then compared to the current situation. Ideally, both cost components and a health benefit components are included in the assessment of outcomes, building on work of Owens et al.Citation17 The authors propose measuring the approximate costs of resources spent and the long-term costs. The authors measure “net health benefit” by comparing benefits and harms of the intervention.

Note that scenarios usually make assumptions about the situation. For example, one might assume that care quality remains the same when substituted to another healthcare provider. Furthermore, calculations are restricted to accessible information (e.g. information about patient population sizes and costs of care). It is important to show transparency in assumptions made, in order to indicate in what sense the scenario might not correctly reflect reality.

Discussion

This article reports on an evaluation of the Bewustzijnsproject as a case study to examine the implementation of HVCCC in medical practice. Even though this case study is situated in a Dutch context, discussions about whether and how physicians can combine a role of patient’s advocate with a role of resource steward are also taking place outside the Netherlands.Citation31–33 CookeCitation1 and WeinbergerCitation2 argue that the reason why physicians are uniquely qualified to act as resource stewards that allocate resources based on value is precisely because they also fulfill a role of patients’ advocate. What is needed to translate the stewardship role to healthcare practices is a set of practical strategies in order to embed principles of HVCCC in “the complexities of heterogeneous health systems and in relation to their simultaneous role as advocates for individual patients.”Citation9(p8) In order to achieve this, efforts should not only focus on introducing principles of HVCCC into the formal curriculum, but also requires a transformation in the informal educational systemCitation3,Citation19,Citation20,Citation23 from one that almost exclusively focuses on medical discussions to one that also considers value and costs as part of medical decision-making.Citation3 This study proposes a set of strategies and system adaptations that could aid the transformation toward a HVCCC supporting context.

A “rational” approach to resource stewardship

We found that continuing to raise awareness among doctors (in training) about the meaning and necessity of delivering HVCCC is essential. This finding builds on the reported need to increase our understanding of what cost-conscious care does and does not mean for medical professionalism.Citation9,Citation34 This study found that the role of doctors as stewards of scarce resources is contested, because it is rooted in the necessity of controlling healthcare costs. Doctors fear that patients will lose trust in medical professionals if they are pressured to consider costs. In addition, physicians associate high-value, cost-conscious care with an imposed limitation to their efforts to act in the patient’s best interest. This notion of imposed limitation in medical decision-making can be linked to rationing.Citation17 Rationing is often located in political discourses of cost control and implicitly refers to restricting the use of any intervention, regardless of its effectiveness or value.Citation17 Educators should be mindful of this unintended association with cost saving when implementing cost-awareness programs. Furthermore, authorsCitation17,Citation23,Citation34,Citation35 have emphasized that an exclusive focus on cost containment should be avoided. Instead, HVCCC should be framed as a means of offering “rational care” in which access to good-value care is preserved by considering value as part of each medical decision thereby eliminating wasteful practices and delivering care that offers high value.Citation35

Even though authors consider HVCCC a “rational” approach to healthcare delivery that balances quality and costs, this “rationality” is not easily translated to practice. This study showed that barriers pose challenges to the delivery of HVCCC and innovations that promote HVCCC. These barriers include uncertainty about how to embed cost considerations in medical decision-making and ambiguity about the exact meaning of the concept HVCCC (Carrier I). As physicians are considered better placed to make value- and cost-sensitive judgements,Citation36 we formulated HVCCC carriers as means to navigate the difficult position physicians are put in as stewards of scarce resources.

HVCCC delivery; a risk for top-down interference?

In order to preserve medical decision-making based on value, the active involvement of physicians in the reflection on and justification of care value is considered key. However, physicians’ active involvement in the delivery of HVCCC sits uncomfortably with the potential intertwinement of HVCCC efforts with top-down interference. Though HVCCC is intended as a bottom-up approach, some of the building blocks, such as “provide quantitative feedback” (Carrier I, Building Block 3), were not supported by all respondents. Opponents of Building Block 3 argued that data of ordering behavior and resources used could be abused by managers to check on or even sanction physicians that “underperform” based on test results. It follows that building a HVCCC supportive system should involve efforts to ensure that HVCCC is positioned as part of medical professionalism and not as a managerial tool. Stammen et al.Citation37 also emphasize that a safe learning environment is needed to foster HVCCC, allowing residents to reflect on current practices as opportunities to learn. Once such a protective learning environment is created in which quantitative feedback and mutual learning can take place, continued efforts will be needed to preserve this format.

Limitations

This study included a series of single-center projects, even though a realist evaluation is ideally conducted on one project that is implemented in different settings. One of the assumptions of a realist evaluation approach is that a single intervention can produce different outcomes when it is introduced in different contexts. We evaluated the implementation of different projects in different settings. The projects were similar with respect to the promotion of HVCCC, albeit by different means. The inclusion of single-center projects makes it more challenging to make inferences about the influence of project characteristics versus the influence of contextual factors. Another limitation was that almost all examined HVCCC projects were implemented in university medical centers. Future research should examine whether the HVCCC carriers are applicable to a variety of healthcare organizations or whether a further customized approach is more appropriate.

From barriers to carriers

Not all respondents agreed that the most effective way to embed HVCCC in healthcare practices is a continued focus on projects (as proposed in Carrier III). Opponents were concerned about the temporary nature of HVCCC projects. Instead, HVCCC should become embedded in standard practice, not something that is confined to temporary projects. The decision to include a continued focus on projects as one of the HVCCC carriers is based on the theoretical notion of system innovation. A system innovation can be seen as a fundamental, long term, change process, based on a continuous set of incremental and iterative interventions. This approach is based on the notion that a system continuously reproduces itself, including its flaws, meaning that the enduring problem of controlling healthcare costs has a systemically embedded nature.Citation38 In order to tackle such persistent problems, a system innovation that involves both innovative practices and system adaptations, is needed in order to address systemically embedded structuresCitation39 that (re)produce unsustainability in the healthcare system.Citation38 We analyzed the Bewustzijnsproject, a system innovation program that, through education and small-scale innovations, tries to embed HVCCC in the minds and actions of future doctors who question existing practices and thus can act as change agents. From a system innovation perspective, small-scale innovation practices provide insight into what works and what does not, and facilitate discussions and reflections on lessons learned and ideas for new initiatives.Citation38 These developments are seen as necessary (though not sufficient) conditions for wider diffusion of innovative practices to address, in this case, unsustainably high healthcare costs. The HVCCC carriers, based on the realist evaluation that takes the context into account, delineate a set of strategies to support residents as change agents and proposes necessary system changes for residents to fulfill this role effectively.

Conclusion

This study identified several barriers that hinder successful application of HVCCC as newly proposed medical competency in educational and healthcare practices. Whereas research activities regularly stop after the identification of facilitators and barriers, we involved stakeholders to establish their role in shaping HVCCC and the settings in which it is implemented to create a HVCCC supporting context. This study proposes a set of strategies and system adaptations condensed in four high-value, cost-conscious care carriers: (1) continue to promote HVCCC awareness, (2) create an institutional structure that fosters HVCCC, (3) continue to focus on projects for embedding HVCCC in practice, and (4) generate evidence that could aid the transformation toward a HVCCC supporting context. Furthermore, the carriers support residents, attendings and others involved in educating physicians in training to develop and implement practices that promote HVCCC delivery.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Science (BETHCIE) of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam approved this research as exempt. Consent for the interviews was confirmed upon agreement to participate in this study. Interviewees were asked to agree to the proposed terms of the interview verbally. Anonymity of all study participants was guaranteed.

| Abbreviations | ||

| BWP | = | Bewustzijnsproject |

| HVCCC | = | High-value, cost-conscious care |

| RE | = | Realist Evaluation |

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate assistance in data collection and analysis from Floris Horst, Marianne Lageweg, Faduma Mukhtar and Dirk Klumper. We also greatly appreciate the time spent by medical residents and attendings to participate in this interview study. Finally, we would like to thank the project managers, program directors and educationalists involved in the Bewustzijnsproject for their participation in our reflection sessions to validate and enrich the data.

Data sharing statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

Funding

Notes

1 The informal educational system refers to the workplace where most of residency training takes place.

References

- Cooke M. Cost consciousness in patient care — what is medical education’s responsibility?N Engl J Med. 2010;362(14):1253–1253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1002530.

- Weinberger S. E. Providing high-value, cost-conscious care : a critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):386–388. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-6-201109200-00007.

- Post J., Reed D., Halvorsen A. J., Huddleston J., McDonald F. Teaching high-value, cost-conscious care: improving residents’ knowledge and attitudes. Am J Med. 2013;126(9):838–842. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.05.015.

- Sirovich B. E., Lipner R. S., Johnston M., Holmboe E. S. The association between residency training and internists’ ability to practice conservatively. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1640–1648. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3337.

- Levy A. E., Shah N. T., Moriates C., Arora V. M. Fostering value in clinical practice among future physicians: time to consider COST. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1440. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000496.

- Tartaglia K. M., Kman N., Ledford C. Medical student perceptions of cost-conscious care in an internal medicine clerkship: a thematic analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1491–1496. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3324-4.

- Gupta R., Arora V. M. Merging the health system and education silos to better educate future physicians. J Am Med Assoc. 2015;314(22):2349–2350. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.13574.

- Gilmour J. A., Weisman A., Orlov S., et al. Promoting resource stewardship: reducing inappropriate free thyroid hormone testing. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(3):670–675. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12698.

- Leep Hunderfund A. N., Dyrbye L. N., Starr S. R., et al. Attitudes toward cost-conscious care among U.S. physicians and medical students: analysis of national cross-sectional survey data by age and stage of training. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):275. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1388-7.

- Courtright K. R., Weinberger S. E., Wagner J. Meeting the milestones. Strategies for including high-value care education in pulmonary and critical care fellowship training. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(4):574–578. doi:https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201501-035OI.

- Chandawarkar R. Y., Taylor S., Abrams P., et al. Cost-aware care: critical core competency. Arch Surg. 2007;142(3):222–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.142.3.222.

- Fred H. L. Cutting the cost of health care: the physician’s role. Tex Heart Inst J. 2016;43(1):4–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.14503/THIJ-15-5646.

- Frank J. R., Snell L., Sherbino J. E. CanMEDS 2015 physician competency framework. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/canmeds/resources/publications. Published 2015.

- The Accreditation Council for Graduate Education, The American Board of Internal Medicine. The internal medicine milestone project. https://acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/InternalMedicineMilestones.pdf?ver=2017-07-28-090326-787. Published 2015. Accessed May 2, 2020.

- Moriates C., Soni K., Lai A., Ranji S. The value in the evidence: teaching residents to "choose wisely". JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):308–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2286.

- Williams D., Clancy C., Dine J. High value care curriculum (HVC) 4.0. https://www.Acponline.Org/Clinical-Information/High-Value-Care/Medical-Educators-Resources/Newly-Revised-Curriculum-for-Educators-and-Residents-Version-40. Published August 16, 2013. Accessed September 1, 2020.

- Owens D. K., Qaseem A., Chou R., Shekelle P., Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Clinical High-value, cost-conscious health care: concepts for clinicians to evaluate the benefits, harms, and costs of medical interventions. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(3):174–180. doi:https://doi.org/10.1059/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00007

- Manja V., Monteiro S., You J., Guyatt G., Lakshminrusimha S., Jack S. M. Incorporating content related to value and cost-considerations in clinical decision-making: enhancements to medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2019;24(4):751–766. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-019-09896-3.

- Patel M. S., Reed D. A., Loertscher L., McDonald F. S., Arora V. M. Teaching residents to provide cost-conscious care: a national survey of residency program directors. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):470–472. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13222.

- Hall J., Mirza R., Quinlan J., et al. Engaging residents to choose wisely: Resident Doctors of Canada resource stewardship recommendations. Can Med Educ J. 2019;10(1):e39–e55. doi:https://doi.org/10.36834/cmej.43421.

- Ackerman S. L., Gonzales R., Stahl M. S., Metlay J. P. One size does not fit all: evaluating an intervention to reduce antibiotic prescribing for acute bronchitis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):462. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-462.

- Tilburt J. C., Wynia M. K., Sheeler R. D., et al. Views of US physicians about controlling health care costs. J Am Med Assoc. 2013;310(4):380–388. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.8278.

- Stammen L. A., Stalmeijer R. E., Paternotte E., et al. Training physicians to provide high-value, cost-conscious care: a systematic review. J Am Med Assoc. 2015;314(22):2384–2400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.16353.

- Colla C. H., Mainor A. J., Hargreaves C., Sequist T., Morden N. Interventions aimed at reducing use of low-value health services: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(5):507–550. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558716656970.

- Lesser C. S., Lucey C. R., Egener B., Braddock C. H., Linas S. L., Levinson W. A behavioral and systems view of professionalism. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;304(24):2732–2737. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1864.

- Wong G., Westhorp G., Manzano A., Greenhalgh J., Jagosh J., Greenhalgh T. RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0643-1.

- Dalkin S. M., Greenhalgh J., Jones D., Cunningham B., Lhussier M. What’s in a mechanism? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0237-x.

- Reddy S., Wakerman J., Westhorp G., Herring S. Evaluating impact of clinical guidelines using a realist evaluation framework. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(6):1114–1120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12482.

- Auerbach A. D., Landefeld C. S., Shojania K. G. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):608–613. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb070738.

- Sackett D. L., Rosenberg W. M. C., Gray J. A. M., Haynes R. B., Richardson W. S. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. Br Med J. 1996;312(7023):71–72. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29730277. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71.

- Grochowski E. C. Ethical issues in managed care: can the traditional physician-patient relationship be preserved in the era of managed care or should it be replaced by a group ethic?Univ Mich J Law Reform. 1999;32(4):619–659.

- Larkin G. L. Ethical issues of managed care. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1999;17(2):397–415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70067-5.

- Pearson S. D. Caring and cost: the challenge for physician advocacy. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(2):148–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-133-2-200007180-00014.

- Korenstein D. Charting the route to high-value care: the role of medical education. J Am Med Assoc. 2015;314(22):2359–2360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.15406.

- Hood V. L., Weinberger S. E. High value, cost-conscious care: an international imperative. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23(6):495–498. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2012.03.006.

- Abbo E., Volandes A. Teaching residents to consider costs in medical decision making. Am J Bioeth. 2006;6(4):33–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15265160600755540.

- Stammen L., Slootweg I., Stalmeijer R., et al. The struggle is real: how residents learn to provide high-value, cost-conscious care. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(4):402–411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2019.1583566.

- Schuitmaker T. J. Identifying and unravelling persistent problems. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2012;79(6):1021–1031. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2011.11.008.

- Grin J., Rotmans J., Schot J. Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change. New York/Oxon: Routledge; 2010. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2015.1028808.

Appendix A:

Example CMO configuration

Appendix B:

Interview guide

1. Could you tell me something about the project that you are currently working on?

What problem does your project address?

What is the main goal of your project?

Who are involved in your project/are supervisors involved? What is their level of involvement?

2. How would you define high-value, cost-conscious care?

3. What facet(s) of high-value, cost-conscious care align with the goals of your project? What aspects does your project address or promote?

Promotion of good-value care delivery

Elimination of low-value care delivery

Reduction of healthcare costs

Raising cost awareness

Facilitators

We are trying to identify high-value, cost-conscious care carriers. We are curious to explore the facilitators that foster the implementation of HVCCC in practice and what barriers may hinder the implementation of HVCCC in practice.

4. If you were to pinpoint factors that support your project, what facilitators come to mind?

Explicate: What is the facilitator, How does it work?, Who is needed?

Barriers

5. What factors hinder your HVCCC project? What barriers have you encountered that make it more difficult?

How does it affect your project exactly?

What is needed to overcome this barrier? (facilitators)

Outcomes

8. What are the envisioned outcomes of your project? What do you wish to accomplish?

What is needed to accomplish that goal?

HVCCC delivery (in general)

10. What factors facilitate HVCCC delivery on a daily basis?

11. What factors hinder HVCCC delivery on a daily basis?

*Questions in italic are probing questions. Depending on the interview, these or other probing questions could be used to identify mechanisms that underlie the implementation of HVCCC in educational and medical practice.

Appendix C:

Facilitators for provision of quantitative feedback (carrier I: Building block 3)

Create a learning culture that incorporates quantitative feedback as part of physicians’ education: Some respondents mentioned that feedback can be abused by managers to check on or even sanction physicians that underperform based on test results. It is crucial that quantitative feedback is incorporated in education and is framed as an opportunity to learn and improve.

Provide real data: According to five respondents “real” (nonanonymous) data of resources used by physicians is strongly preferred over simulated data in order “confront” physicians with reality and thereby induce a sense of urgency to adjust working procedures among physicians. Nevertheless, it should be stressed that anonymity of the data can only be discarded if the abovementioned condition of providing a safe training environment is met.

Provide comparative quantitative data: Ideally, physicians receive data about their ordering behavior combined with reference data, such as performances of colleagues. Education meetings can be organized to facilitate colleagues to reflect on interpersonal data differences together. A discussion of reasons for interpersonal differences can trigger the exchange of HVCCC strategies applied by colleagues. Some respondents suggested that education meetings could finish with the formulation of personal action points in which attendees concretely describe which adjustments they will implement to enhance HVCCC. Planning a follow-up education meeting in which physicians update on action points could help to encourage physicians to turn ideas into actions and “test” whether formulated strategies produce the desired effects.

Identify parties within the hospital organizations that can provide quantitative data: Respondents stressed that attention for improving HVCCC requires physicians to be constantly reminded of it. This could be facilitated by providing quantitative feedback regularly in order to keep physicians aware of their performances and trigger them to adjust working methods to improve HVCCC. Regular provision of quantitative data can also be used to determine if implemented strategies to enhance HVCCC are actually effective.

Appendix D:

Identified characteristics of an effective HVCCC ambassador (carrier II, building block 1)

A HVCCC ambassador makes sure that residents and supervisors are continuously informed about the importance of HVCCC (e.g. they frequently give presentations about this topic, they put HVCCC on meeting agendas, they make the topic visible by means of posters);

A HVCCC ambassador acts as a role model. Their status as a figure that residents look up to legitimizes the importance of HVCCC;

HVCCC ambassadors are well-informed about HVCCC developments and projects.

HVCCC ambassadors encourage medical residents to pursue their intrinsic motivation to improve healthcare in terms of HVCCC. Ambassadors actively discuss the topic of HVCCC during progress reviews with residents and thereby encourage residents to incorporate HVCCC in their personal career development and turn ideas into projects;

HVCCC ambassadors look for ways to create time for the resident to execute the project as part of their residency training and help them to write a proposals for their HVCCC project;

HVCCC ambassadors have a network. They can connect residents to relevant stakeholders who can support their HVCCC project;

HVCCC ambassadors organize network meetings and symposia in which they invite project initiators to present their HVCCC project ideas and the outcomes of running projects. These meetings have two advantages: running projects can benefit from the feedback of colleagues. In addition, it can inspire residents to think of their own ideas for HVCCC improvements.

Appendix E:

Strategies for identifying and involving stakeholders (carrier III, building block 2)

Give residents the opportunity to present their project to others: allow residents to pitch their proposal during (staff) meetings. Pitches not only inform others of the project, it also allows the audience to provide feedback which helps to refine the project. In addition, the resident can establish whether the project addresses a problem that is recognized by the staff.

Encourage residents to organize a project kickoff event: in order to gain support for the project, it is crucial that others are convinced of the relevance of the project. Communicating a strong problem statement and clear project goals helps to gain support from others.

Encourage residents to get acquainted with the roles and responsibilities of other healthcare professionals in the healthcare chain. Most projects require the cooperation of other healthcare providers in project execution, which could add additional tasks and complexity to other’s work. Respondents recommended that project initiators invest time to inform others about the project outcomes that will be yielded through their effort. In order to facilitate this process, residents could get acquainted with the roles of other healthcare providersCitation6 in order to make an assessment of the project’s impact. Finally, residents can use these insights to deliberate ways to minimize negative impact (e.g. increase in workload, work complexity) of the project together with the other healthcare professionals.

Explicate roles and responsibilities: unclarity of the roles and responsibilities within the project can lead to project delay, because people do not know how they have to contribute to the project. In addition, unclarity of roles can lead stakeholders to feel unsure, which could lead to resistance. Explicating the roles and responsibilities verbally as well and in the project plan helps to reduce unclarity.