Abstract

Mentally tough behaviors (MTbs) entail verbal or physical acts that allow athletes to engage their capacity to produce consistently high performances under pressure. However, researchers of mental toughness (MT) have typically focused on the characteristics that make an athlete mentally tough, rather than how these characteristics are developed through learning to, and reflecting on, the display of MTbs. Consequently, we explored the athlete MT development process within youth international football. Collaborating with a Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) National Association, age-group international players (n = 6), coaches (n = 6), support staff (n = 7), and parents (n = 6) were interviewed regarding MTbs, the specific contexts (e.g., training) that require MTbs, and how key personnel (e.g., coaches, parents, teammates) might help develop players’ MTbs in international youth football. Using thematic analysis, we found MT development to be a relational, multidimensional process, where players transacted with individuals (e.g., coaches) in their environment. These individuals’ behaviors (e.g., autonomy-supportive) influenced players’ propensity to engage in and reflect on contextually relevant MTbs, leading to MT understanding, development, and maintenance. We suggest organizations develop a common understanding of the MT development process and educate all relevant stakeholders regarding their role in supporting athletes to develop the capacity to perform consistently under pressure.

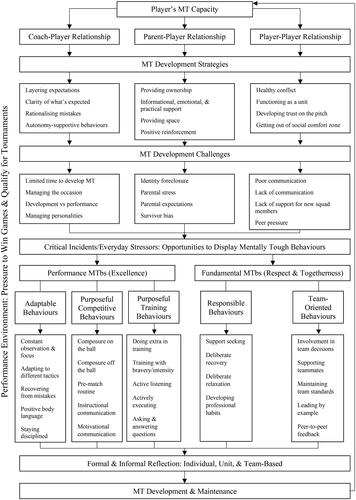

Lay summary: We explored key stakeholders’ perceptions of mental toughness (MT) development in international youth football. We found players’ MT is developed via key relationships, with players encountering opportunities to display this capacity via mentally tough behaviors (MTbs). Players must reflect upon their display of MTbs to further develop and maintain MT.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Practitioners should assist coaches in learning to consistently recognize MTbs in critical moments in training and competition and reinforce the display of these MTbs in players via autonomy-supportive practices.

Practitioners should educate athletes regarding the importance of displaying and reflecting on MTbs under pressure to develop their MT capacity.

Parents of international players need to be educated on what MT is and the role they play in developing their child’s MT at home.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, there has been an increase in research on the psychological characteristics athletes should develop to navigate critical moments on talent development pathways (e.g., Collins & Macnamara, Citation2017; Taylor & Collins, Citation2020). Similarly, researchers have identified how individuals differ in their capacity to use these psychological characteristics when encountering everyday stressors, such as the physical demands of training, and more significant developmental challenges, such as long-term injury (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2016). One such capacity described by coaches, athletes, and sport psychologists as key to performing under such demands is mental toughness (MT; Weinberg et al., Citation2018). MT has received considerable research attention over the last 20 years (see Gucciardi, 2020), yet clarity regarding the role of MT within performance has been hampered by a lack of agreement over its conceptualization. Researchers have portrayed MT as: (a) a uni- or multi-dimensional construct; (b) a trait, a state, or a combination; and (c) a construct linked to an extensive number of characteristics, such as self-belief, determination, and coping with pressure (e.g., Clough et al., Citation2002; Gucciardi et al., Citation2008; Hardy et al., Citation2014; Jones et al., Citation2007). Nevertheless, these views of MT have commonalities, highlighting how MT allows individuals to cope and persevere despite the demands they face, as they strive toward specific goals (Gucciardi, Citation2017).

Drawing on these commonalities, Gucciardi et al. (Citation2015) provided greater conceptual clarity to MT and the link between the characteristics (e.g., optimism), coping processes (e.g., problem-focused), and outcomes (e.g., behaviors) associated with MT. Based on their work across sport, business, academic, and military contexts, Gucciardi et al. (Citation2015) defined MT as “a personal capacity to produce consistently high levels of subjective or objective performance despite everyday challenges and stressors as well as significant adversities” (p. 28). This definition has received growing support, given its acknowledgement that MT plays a key role in the stress process (Piggott et al., Citation2019). Aligned with cognitive-motivational-relational theory (CMRT), Gucciardi et al. outlined how individuals with higher MT levels across performance contexts possessed a greater capacity to appraise stressors in a challenging rather than threatening manner, to utilize appropriate coping resources (Lazarus, Citation1999). Further, Gucciardi et al. provided empirical support for a unidimensional rather than multidimensional MT model, highlighting that individuals do not view MT as a constellation of characteristics (e.g., self-belief, optimism) but as a single resource to be utilized in response to varying levels of stressors.

There is growing consensus regarding MT’s conceptualization as an individual’s potential for action under pressure, and the need to better link this underlying MT capacity to how one displays this resource under pressure, and the subsequent performance outcomes (Jackman et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, much of the MT literature has focused on unobservable aspects of the construct, including MT characteristics and cognitions (e.g., focus), rather than what these aspects allow a mentally tough athlete to do (e.g., communicate effectively; Anthony et al., Citation2020). Observable mentally tough behaviors (MTbs), however, represent an indirect but measurable way to understand what constitutes being mentally tough and how it leads to consistently high levels of performance under pressure. Typically, MTbs entail verbal or physical acts that allow athletes to engage their capacity to produce consistently high performances when faced with pressure (Anthony et al., Citation2018). Importantly, the behavior-based approach to MT development being advocated in this study needs to be distinguished from behaviorism itself. Traditional behaviorism views behavior as a response to external stimuli, with the reinforcement of desired behaviors and punishment of undesirable behaviors resulting in certain outcomes, and the role of an individual’s internal processes (i.e., cognitions, emotions) being overlooked (Bandura, Citation2001). By contrast a behavior-based approach to MT development recognizes that an individual’s internal processes, behaviors, and surrounding context are inseparable. Therefore, a behavior-based approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of MT development through not only examining an individual’s behavioral responses to challenges and adversities, but also their capacity to cope with these challenges, and how their coping response can have a facilitative or debilitative effect on their environmental conditions, development of personal resources (i.e., MT, associated MT cognitions), and future reactions (Lazarus, Citation1999). Recently, researchers have identified observable MTbs within sporting contexts such as football (e.g., taking time on the ball; Diment, Citation2014) and volleyball (e.g., awareness of whether the ball is landing in/out of bounds; Madrigal, Citation2020). These investigators highlighted how, through selecting and displaying MTbs consistently, athletes could develop the underlying cognitions associated with performing under pressure. Nevertheless, these studies did not outline a clear process regarding how the display of MTbs can lead to the development of one’s capacity to cope under pressure. As such, the current study sought to distinguish between MTbs being an indicator of one’s MT capacity, versus the role MTbs play in one’s MT development. Accurately conceptualizing the MT development process, and the role of MTbs within that process, is essential to provide coaches and practitioners with strategies to develop athletes’ capacity to perform under pressure across various contexts.

Providing conceptual understanding to the MT development process requires researchers to integrate established theoretical frameworks from the developmental psychology literature. For example, Anthony et al. (Citation2016) created a MT development model underpinned by the bio-ecological model of human development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006). The bio-ecological model portrays individuals as agents of their own development, who use personal characteristics (skill-based resources; motivational forces) to interact and develop relationships in their immediate environment (microsystem, e.g., coach-athlete relationship) and related contexts (mesosystem, e.g., coach-parent relationship; macrosystem, e.g., cultural meaning of MT) across their lifespan (Anthony et al., Citation2016). Thus, resources such as MT are developed over time and across contexts through one’s environmental interactions. Essential to this process is the notion that individuals’ MTbs are partially shaped by transactions with adversity. Individuals also have the capacity to shape similar future transactions and behavioral responses through the processes of coping, reflecting, and adapting (recursive principle; Lazarus, Citation1999). Moreover, athletes must learn to navigate the social and cultural norms associated with consistent high performance in their sport (i.e., what MTbs are valued by key stakeholders within the sport environment?; Anthony et al., Citation2018). Given these contextual nuances, it is arguable that for MT to be developed effectively within a specific environment, a ‘bottom-up approach’ must be adopted (Eubank et al., Citation2017). Such an approach involves researchers collaborating with sport organizations to create frameworks for what MT development entails in their contexts (i.e., MT cognitions, MTbs, adaptational responses, MT development strategies; Coulter & Thelwell, Citation2019). Central to this approach are the lived experiences of athletes, who are constantly appraising the stressors they face in relation to their values and goals and must learn to display MTbs on a consistent basis under varying degrees of strain (Lazarus, Citation1999). Researchers have previously overlooked athletes’ views concerning MTbs and MT development in favor of coaches (Anthony et al., Citation2020), sport psychologists (Weinberg et al., Citation2018) and other stakeholders responsible for facilitating athlete’s psychological development. Such insights have not provided a holistic view of MT development from a person-context perspective.

A behaviour-based approach to MT development: an international football collaboration

This study was conducted in collaboration with a UEFA National Football Association. Previous research conducted with this Association focused on identifying the psychosocial demands players face making the club-to-international transition (McKay et al., Citation2021). Incorporating the perceptions of international youth players and coaches, a range of performance (e.g., new football education), organizational (e.g., managing relationships) and personal demands (e.g., social pressures) were highlighted, as well as the situational properties of these demands (e.g., novelty). A key outcome of McKay et al.’s study was that for players to successfully navigate the international talent pathway, they needed to develop state-like personal resources to cope with the fluctuating demands they faced on this journey, while also performing to a consistently high level to maintain their place in the squad, achieve re-selection, and progress through the age groups and into the senior team. One such individual state-like resource, specifically identified by coaches in McKay et al.’s study as vital to facilitating these outcomes, was MT. Indeed, MT is characterized by an individual’s capacity to endure and adapt to a range of psychological demands in pursuit of both personal and performance-based goals across situations and time (i.e., context-dependent; Gucciardi et al., Citation2015). Therefore, it was decided that MT warranted investigation over similar psychological constructs, such as hardiness, which is typically enduring across situations and time, and resilience, which is a dynamic outcome contingent on a range of individual (e.g., MT), group and sociocultural protective factors (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2013). As such, there was a need to investigate the nature of MT development within this UEFA National Football Association; specifically, the MTbs the Association viewed as critical for players to cope with international football demands and the strategies they used to develop players’ MT capacity. Researchers have previously utilized contextually developed MTbs to solely target players’ behaviors (e.g., responses to punishment-conditioned stimuli; Bell et al., Citation2013) and coaches’ practices (e.g., behavioral coaching framework; Anthony et al., Citation2018). By contrast, the current study sought to create a shared understanding of the MT development process (MT development strategies, MTbs) through constructing a MT development framework. This framework could then be used to inform the design of a MT development programme for coaches in the participating UEFA National Football Association, and to inform coaching practice. Therefore, the aims of this study were to investigate: (1) MTbs in international youth football; (2) the specific contexts (e.g., training, competition) that require MTb in international youth football; and (3) how key personnel (e.g., coaches, support staff, parents, teammates) might develop players’ MTbs in international youth football.

Method

Philosophical position

A constructivist approach underpinned our research. Specifically, we adopted a relativist ontological position through which we understand that individuals’ interpretations of the world around them are based on their experiences and interactions with others (Matz et al., Citation2019). In a research setting, knowledge of participants’ multiple realities relies on the researcher being an “active participant” in data collection (i.e., a subjectivist epistemological position; Krane & Baird, Citation2005, p. 90). The researcher must account for their understanding of reality, including the theoretical frameworks they implement, and the socioeconomic structures and culture in which they are situated (Wiltshire, Citation2018). Our philosophical position meant we considered there to be multiple sets of MTbs across different sporting contexts, which are valued by both the individual and the organization, due to their impact on an individual’s capacity to perform optimally under pressure. Therefore, MT is a socially constructed concept and relies on the researcher accurately portraying participants’ lived experiences to reach consensus on conceptual understanding (Gucciardi, Citation2017). Consequently, theory-free knowledge development was not possible, and we took several measures to identify and minimize researcher bias, including interviewing multiple stakeholders (e.g., players, parents, coaches), stating our conceptual position regarding MT and MTbs at each interview’s outset, and providing interviewees with MTb categories (e.g., competitive, training).

Participants

The sample was selected purposively from the participating UEFA National Association (Patton, Citation2015). We selected participants who: (a) were either playing international youth football, or were parents of youth international football players, or worked in a performance (e.g., coaches) or support role (e.g., physiotherapists) within international football; and (b) had a minimum of two years’ (or four international camps) experience performing or supporting (i.e., parents) in their role. International youth football players attend approximately four to five international camps per year, typically each lasting one week. Therefore, we deemed that recruiting participants’ who had a minimum of two years’ experience being involved with these international camps would ensure we sampled a group of individuals who could provide detailed insight into the nature of MT development and types of MTbs.

Given the sampling criteria (e.g., two years’ experience), approximately 60 players and 120 parents/guardians of players from the under 16s to under 21s age groups, and 46 support staff and 18 coaches from under 15s to under 21s age groups were deemed eligible for participation. Contact lists for players and parents were provided by the National Association, with an initial selection, thought to offer a representative sample, being contacted by the research team (players, n = 12; parents, n = 12—three individuals per age group). With the agreement of the National Association, all support staff and coaches were invited to participate. Following initial email contact, a reminder was sent out to those who had not responded, after which the final sample consisting of everyone who replied positively was confirmed. Due to availability (e.g., some support staff work part-time for the National Association; players are full-time in professional club academies), the final sample included international players (n = 7), coaches (n = 6), support staff (n = 7; five performance analysts; one physiotherapist; one education & welfare officer), and parents of international players (n = 6—all identified as parents rather than guardians). To examine MTbs and MT development across the international pathway, our participants were recruited from across age groups, including under 15s (coaches, n = 1; support staff, n = 2), under 16s (support staff, n = 1; parents, n = 6), under 17s (players, n = 4; coaches, n = 2; support staff, n = 2), under 18s (players, n = 1; support staff, n = 1), under 19s (players, n = 2; coaches, n = 2; support staff, n = 1), and under 21s (coaches, n = 1; support staff, n = 1). Players were aged between 16 and 18 (M = 16.6, SD = 0.73) with between two and six years’ international playing experience (M = 4.29; SD = 1.58). Coaches were aged between 42 and 56 (M = 47.2, SD = 4.71) with between four- and 11-years international coaching experience (M = 7.33; SD = 2.70). Support staff were aged between 27 and 67 (M = 37.3, SD = 13.19) with between two- and fifteen-years’ international football experience (M = 6.71; SD = 4.13). Parents were aged between 41 and 49 (M = 44.6, SD = 2.94).

Focus group and interview guides

One focus group guide (coaches) and three semi-structured interview guides (players, staff, parents; available on request) were created to examine each cohort’s views on MTbs and MT development. Aligned with our philosophical position, these guides contained overarching questions to examine participants’ displays of MTb (e.g., “What MTbs do international players display in response to challenging situations in training?”) while providing flexibility to probe participant responses to better understand their lived experiences (e.g., “What specific actions do you observe this player doing?”). In this way, we attempted to overcome previous issues in MTb research, whereby participants failed to describe MTbs in sufficient detail, compromising the link to effective MT development (Anthony et al., Citation2020). All guides had five sections. First, the interviewer provided a MT definition (see Gucciardi et al., Citation2015) to stimulate discussion and asked all participants to discuss the typical demands a player faces in international youth football (e.g., “What are the major personal challenges players encounter on their journey to being selected for the international team?”). Second, participants were asked to identify key MTbs players need to display across different contexts (e.g., “What observable MTbs does your child display in response to challenging situations at home?” or “What are the key MTbs you need to display on the pitch to perform consistently when dealing with challenges you’ve experienced?”). Third, participants discussed key MT development strategies they implemented in international football (e.g., “How do you develop MT through your coaching sessions to assist players in performing to a consistently high level when faced with challenging situations?”). Fourth, participants’ perspectives on MT maintenance over time were explored (e.g., “How do you, as a coach, get players to reflect after an international camp and refine their MTbs in preparation for the next session/game/international camp?”). Finally, participants were asked for their thoughts on the data collection experience to check for potential researcher bias.

To test the effectiveness of each guide, pilot focus groups were conducted with coaches (n = 3), and pilot interviews with parents (n = 2), support staff (n = 1), and players (n = 2). Subsequently, coaches highlighted the need to consider wider demands of international football (e.g., short duration of international camps) when discussing MT development. Therefore, the guides were updated to better link the introductory question on international football demands to the main questions on MTbs and MT development (e.g., “What are the key MTbs you need to display off the pitch to perform consistently when dealing with the challenges you’ve discussed?”). Further, pilot participants identified the need to provide a lay version of the MT definition (i.e., MT is the ability of an individual to perform to a consistently high level when faced with challenging situations) alongside the published version to clarify its focus on sustaining high performance under pressure.

Procedure

Following Institutional Ethics Board approval, access was granted from the UEFA National Football Association to approach potential participants. Potential participants were contacted via e-mail and informed of the nature of the study. Players, coaches, staff, and parents who agreed to participate provided written consent and were informed of their rights as participants. For players under 18 years of age, their written assent was provided, alongside the consent of a parent/guardian. Participants then took part in one of two focus groups (coaches—three participants in each group) or interviews (all others). Participating coaches had a minimum of four years’ experience working full-time within the National Association and so possessed an in-depth understanding of the talent development pathway. Further, the National Association employs a system whereby the head coach of one age group (e.g., under 17s) also undertakes an assistant role in the following age group (e.g., under 19s). This ensures continuity between age groups, particularly for players making the intra-team transition. Given coaches’ busy full-time schedules and coaches’ familiarity both with the pathway and each other, focus groups were the most appropriate data collection method for this cohort, as it provided the opportunity for them to collectively discuss their experiences of working with players across multiple age groups. Data collection took place online via Microsoft Teams. Coach focus groups lasted an average of 82 minutes (SD = 1.4), while interviews lasted on average 57 minutes for players (SD = 9.23), 64 minutes for support staff (SD = 8.81), and 72 minutes for parents (SD = 6.2). All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, yielding 508 pages of text.

Data analysis and methodological rigour

Data was analyzed and interpreted using reflexive thematic analysis (TA; Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). Aligned with our philosophical approach, we utilized reflexive TA with an experiential orientation to illustrate the multiple realities of our participants, providing detailed quotes and creating overarching themes to reflect their collective experiences of MT development and the MTbs necessary for international football (see Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). The TA process followed six steps. First, interview transcripts were read and re-read by all authors to ensure familiarity and identify initial patterns in the data. Second, the first author created codes to capture concepts related to the overall research aims (e.g., impact of having the courage to fail during critical moments on MT development). In recognition of the need for reflexivity (e.g., recognizing one’s own biases and theoretical positioning when analyzing data), a critical friend approach was employed (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). This involved authors one and two critically discussing generated codes, with author two challenging author one’s potential biases regarding MTb conceptualization and their impact on MT development. Third, authors one and two organized codes into descriptive themes that captured key ideas in relation to the research aims. Here, author two critically assessed author one’s generated themes, offering alternative explanations, and encouraged them to review the coded data as analysis progressed to ensure themes continued to make sense. For example, behaviors linked to one’s ability to recover after negative events were grouped under the descriptive theme positive body language. Fourth, the same authors reviewed each theme to ensure each made sense in relation to the research aims. Fifth, authors one and two created an accurate definition for each theme that linked back to the raw data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). Finally, authors three and four acted as critical friends to clarify the conceptual distinction of each theme and its relevance. The critical friend approach facilitated debate between authors regarding the presentation of themes and the underpinning theoretical frameworks and biases that impacted data interpretation (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018).

Results

Constructed through analysis of our findings, outlines a process for MT development in international youth football. Specifically, a player’s MT capacity is developed via relationships between players and key personnel (e.g., player-coach) across competitive, training, and developmental contexts. Within these contexts, there are also challenges that may hinder MT development (e.g., time-limited environment). As players learn to develop MT within these contexts, they encounter opportunities to display this capacity via performance and fundamental MTbs on and off the pitch. Finally, players must reflect upon their display (or lack of display) of MTbs to further develop and maintain their MT capacity over time. Aligned with the structure of our MT development model in , the results are divided into three sections: (1) how MT capacity is developed via relationships, and MT development challenges (see MT Development Strategies and MT Development Challenges sections in ); (2) when players can display MTbs on and off the pitch and what MTbs players display to develop MT in international youth football (see Opportunities to Display MTbs section in ); and (3) how MT is developed and maintained over time via reflection and learning (see Formal and Informal Reflection section of ). We acknowledge that while the MT development process is presented in a linear format in , MT is developed through an ongoing transaction between the individual and their environment, across contexts and over time (Anthony et al., Citation2016). Due to their collaboration in supporting players on the international development pathway, coach and support staff insights into MT development are combined in the results section. Further, all themes are supplemented with direct quotes from participants to give the reader insight into each population’s lived experiences of MT development.

Player-coach relationship

The player-coach relationship was considered essential in supporting players’ MT development via MTbs. Specifically, coaches talked about how they clarified and reinforced context specific MTbs on and off the pitch, to aid players in learning to display these MTbs on a regular basis and improve performance consistency. Participants identified a range of MT development strategies associated with the player-coach relationship that were categorized into four main themes: layering expectations; clarity of what’s expected; rationalizing mistakes; and autonomy-supportive behaviors. Participants also discussed four main challenges to implementing such strategies: limited time to develop MT; managing the occasion; development versus performance; and managing personalities. When players first transition into international football at the approximate age of 15, coaches spoke about the need to layer expectations. Coaches reported implementing a developmental philosophy, where players are afforded time to foster relationships with coaches and become comfortable with the international football environment, prior to entering the results-orientated culture of competitive international football: “When players arrive at under 15s, they don’t have to be mentally tough, you must layer expectations. Let them get a couple of years international experience … then when they compete in European qualifiers, they can manage that better” (Coach 1). Coaches and staff highlighted how, when players failed to develop this environmental comfort, they were unable to manage the occasion when trying to win competitive games and qualify for tournaments. This was especially true for players transitioning from lower-level clubs, where they had not been exposed to the technical, physical, and mental demands of international football, and so failed to perform under pressure: “Our players are not exposed to consistently high-level competition at club level, particularly playing three games in 10 days (Support Staff 3).” Players also cited struggles making the transition from a development to performance environment and trying to qualify for tournaments. When performing under pressure to win, players spoke about feeling isolated and struggling with the personal ramifications of failing: “Mentally, international football is a lot more challenging, especially qualifiers because you think, ‘If I make a mistake and we’re out, that’s my fault’” (Player 7).

Coaches emphasized the importance of rationalizing mistakes when developing the MT required to cope with international football demands:

I don’t mind players making mistakes, as long as they’re trying to do the right thing. If we’re going to produce players that make it to the senior team, they’re going to end up making mistakes at 15 or 16 and we’ve got to support them through that (Coach 3).

Player-parent relationship

Given international camps only occur four to five times per year, a player’s home environment and relationship with their parents was also considered important for MT development. Participants highlighted several MT development strategies parents implement to support their children, including: providing ownership; informational, emotional, and tangible support; providing space; and positive reinforcement. Participants also mentioned four challenges that impacted these strategies effectiveness: identity foreclosure; parental stress; parental expectations; and survivor bias. Parents emphasized the importance of giving ownership to their child over their MT development for international football. For example, parents encouraged their children to form a greater self-awareness of their own performances via Socratic questioning: “As a parent, it’s important to ask questions like ‘how do you think that went?’ or ‘why did you do that?’ rather than ‘go do this’ or ‘go do that’” (Parent 1). This led to an informal conversation about the performance, with parents providing informational support: “I think it’s important for them [child] to be able to talk the game through with someone and put challenges in place to improve” (Parent 2). Participants reported that these challenges often involved working on specific aspects of players’ performance at home, with parents providing tangible support to help their child develop a skill that could be recreated under pressure: “My son’s right-footed, so to improve his left foot, he’ll go out to the park with my husband and practice” (Parent 4). However, the sacrifices parents made to support their children to play international football often brought high levels of parental expectations: “A lot of the time it’s ferrying them around the country, paying to stay overnight. They need to do well to make it worthwhile” (Parent 3). Further, informational and tangible support were often provided by international coaches, with parents’ primary roles involving emotional support: “I think sometimes your child just wants to talk at you. They don’t want your feedback; they just want you to listen” (Parent 1). Players spoke about how, as they progressed through the international pathway, they relied on their parents to “focus my mind elsewhere after a bad game” (Player 7), meaning parents had to learn to provide space and adopt a diminished role in their development:

It’s about knowing your child and giving them that space, knowing they are reflecting themselves. The car shouldn’t always be the place for post-match analysis, because otherwise they [player] associate the car with ‘oh my god, Dad is gonna give me the third degree.’ If you try push support on them, you’ll be met with a wall (Parent 3).

Player-player relationship

Forging relationships with teammates on and off the pitch was reported as essential for players to develop the MT required to execute their tactical role in a novel environment (e.g., playing against an international team for the first time) under pressure. Participants discussed four main MT development strategies associated with the player-player relationship: healthy conflict; functioning as a unit; developing trust on the pitch; and getting out of your social comfort zone. Challenges linked to the player-player relationship that may affect MT development were: poor communication; lack of support for new squad members; and peer pressure. Due to the changing nature of international squads, international camps typically focused on team-based sessions, with players learning how to function as a unit (e.g., defenders, midfielders): “International training is team and tactics-based. For example, one session involved attacking and defending set pieces. We had to get the right images in our head [of how to play as a team] before going out on the pitch” (Player 6). The purpose of these sessions was for players to develop trust on the pitch in those playing around them:

We’d usually work in units, which helps you build those relationships with other players you might not have played with before. You get to know your teammates by talking to them and training with them more. That really reflects in how we work on the pitch then as well (Player 4).

In developing this on-pitch trust, healthy conflict was also encouraged where coaches asked players to “have the confidence to feedback to each other” (Coach 1) about their performances to enhance MT. It was important, however, that players framed this healthy conflict in a constructive manner, rather than engage in poor communication, which may be detrimental to both an individual’s capacity to perform consistently and team functioning: “If I make a mistake and somebody just says, ‘Oh, you should’ve done this’ straight away, I just think ‘Shut up, ye I know’” (Player 4). As such, while MTbs are displayed individually, players acknowledged that developing the capacity to perform under pressure required them to rely on the MTbs of the players around them as well. Trust between players was also developed off the pitch, where players were encouraged to get out of their social comfort zone, through “sharing their experiences from their different football clubs” (Coach 2), rooming with different teammates: “Being in rooms on international duty, that’s when you talk and get to know a person and form friendships” (Player 7), and engaging in social activities: “In the evenings we put on events, quizzes, games and so on, to get some bonding and camaraderie going” (Support Staff 1). Players emphasized the importance of being authentic in developing these relationships rather than succumbing to peer pressure on international duty. Being authentic in these new relationships allowed players to focus on enhancing their own capacity to perform consistently: “I used to be a sheep [on international camps] and do things I didn’t want to, like stay up to 3am. Off the pitch it’s about not messing about, doing the right things, showing the coach you’re the better player” (Player 7). Players reported transferring the strong relationships and team ethos formed off the pitch into their performances under pressure in competition: “Playing with a stranger is much more uncomfortable than playing with a mate” (Player 2).

Opportunities to display mentally tough behaviours

As players interacted with key personnel within and outside international football, developed relationships, and acquired MT, they encountered opportunities to display MTbs across competitive, training, and developmental contexts. Importantly, behaviors identified in this study were characterized as MTbs because they were verbal or physical acts that allowed players to engage their capacity to produce consistently high performances in critical moments where they encountered the stimulus of pressure (Anthony et al., Citation2018). This capacity to focus on one’s decision-making process and produce the correct action under pressure, distinguishes these MTbs from regular behaviors. In international football, these task-oriented endeavors centered around performing at a consistently high level under pressure in competition (e.g., recovering from mistakes; performance MTbs), learning the behaviors necessary to perform at a reliably high level in training (e.g., asking questions; performance MTbs), and regularly displaying professional behavior off the pitch to maximize one’s chances of successful performance under pressure (e.g., deliberate recovery; fundamental MTbs).

Mentally tough behaviours

Performance MTbs

In competition and training, participants reported that players encountered opportunities to display and test performance MTbs, which were classified as any observable actions a player displays on the pitch that indicates their intense desire to continuously improve. Performance MTbs included being adaptable, training with purpose, and competing with purpose. Football is a dynamic sport and consequently participating players emphasized the importance of being adaptable. Players discussed the need to constantly observe the game, anticipate all potential scenarios and avoid mistakes: “You’ve always got to stay focused on the game, you can’t just watch it; see where your man is, where the ball is, and position yourself right” (Player 4). However, players also acknowledged it was important to recover quickly when errors happened: “If you make a mistake or lose the ball, you’ve got to get back into position and do your next job” (Player 5). Further, coaches and players emphasized the importance of players displaying positive body language after an error, with some individuals implementing a refocusing routine to recover quickly: “You’ve got to have something, whether it be clapping your hands or hitting your head, that helps you shake off the mistake and play on as if nothing happened” (Player 7) and to show their courage to try again: “If they [player] make a mistake in front of their goal, have they got the bravery to ask for the ball in the same place the next time?” (Coach 2). Staying disciplined during difficult moments was another key MTb discussed by staff, with players needing to remain calm under pressure and not get distracted by external factors: “If they’ve [player] missed a chance, not moaning about it, but jumping back up. If they’re being constantly fouled, not moaning to the referee, or getting despondent” (Support Staff 2).

Players, coaches, and support staff all indicated that players’ ability to remain composed on and off the ball was essential in helping them to compete purposefully. Specifically, coaches discussed how players who exhibited MT possessed a clarity of mind when displaying their technical ability under pressure: “If you can’t deal with the ball in tough situations [getting tackled by the opposition] consistently and act decisively, you won’t play much for this country” (Coach 1). Players broke this technical process down into key steps, which they could reproduce in various pressure situations: “Check my shoulder, see where my opponent is, take my first touch away from them, ready to play the next pass or turn, because if you’re not concentrating and have a poor first touch, you might lose the ball” (Player 5). Off the ball, players highlighted the importance of displaying composure to create the space necessary to receive a pass and help a teammate under pressure: “Not everything good you do is with the ball. Your movement can drag a player away for someone else to score… You need to be constantly affecting the game” (Player 3). Players mentioned how, to be constantly effective and maximize the chance of goal achievement, they needed to observe the game and position themselves appropriately both individually and collectively. This required clear instructional communication: “If I say, ‘Get tighter!’ to my midfielder and he does, then the opponent doesn’t turn, doesn’t run at me, and we prevent a chance. It’s about making sure your whole team is organised” (Player 5). This communication needed to be motivating, and account for the individual: “Some of my teammates, if they make a mistake just want to be told ‘Sort it out’, whereas others want to be encouraged, rather than told what they did wrong” (Player 4) and the situation: “Whether we’re winning or losing 5-0, we need to keep communicating effectively and working as a unit” (Player 3). Therefore, according to the players, and aligned with our earlier findings regarding MT development strategies, effective communication relied on the development of trusting relationships between teammates: “I trust my fellow defenders… Pre-match, we usually have a conversation about what I want from them, and I tell them that I know they can do it” (Player 4).

Players’ capacity to compete with purpose in matches was reported by players and coaches to be developed through training with purpose during international camps. Here, players explained how they engaged in short, sharp tactical sessions with coaches, where engaging in meaningful discussion and asking questions were encouraged based on a strong working relationship: “It’s important for players to be confident to ask questions, otherwise it’s pointless just having information thrown at you” (Player 4). Players detailed how they were tested by coaches on their capacity to execute instructions on the training pitch:

It’s important to listen to the coaches [before training], have those mental images going onto the pitch, and have the mental strength to implement those instructions repeatedly with intent and effort. It would be interesting if the coaches didn’t provide any instructions on the pitch, to find out who has or hasn’t listened. (Player 6).

Fundamental MTbs

In development scenarios, players encountered opportunities to display fundamental MTbs; which were classified as any observable actions an individual displays to improve their ability to learn efficiently and think rationally. These MTbs included being responsible (e.g., deliberate recovery) and being team oriented. Players used their fundamental MTbs to help develop their performance MTbs on the pitch. For example, players spoke about being responsible through developing professional habits at camp to help them recover between games: “Recovery is very important—stretching, getting an ice bath, stuff like that. If you’ve got two games in three days, you’ve got to be fully energised” (Player 7). Players detailed having to balance being performance-focused and the ability to switch off at camp, but also demonstrate a maturity in how they spent their downtime: “The more focused players take a nap or just chill out. You don’t want to mess about in the hotel, twist your ankle and be out for the rest of camp” (Player 6). Coaches viewed the professional habits players displayed as essential in progressing through the international pathway: “If you do cut corners in what you eat, the way you sleep, you won’t get away with it at international level” (Coach 3). Coaches also emphasized players seeking out support as a clear sign of professionalism and desire to continuously improves themselves: “If you’re not sure, be brave enough to ask for clarity. That can be quite difficult for young players to do” (Coach 4).

For coaches and players, taking responsibility for their own development also demonstrated how team-orientated a player was, and their willingness to improve themselves, and those around them, for the good of the team. Players and support staff discussed the important role of the experienced players in the international squad, who were typically looked upon to maintain team standards and rules from camp to camp: “We have a set of rules within camp—punctuality, forgetting training gear—and whoever breaks these rules gets a punishment, such as clearing their table” (Player 3). These experienced players acted as “a link between coaches and players” (Support Staff 4), encouraging players to engage fully in sessions and forming a leadership group to discuss any in-camp issues with coaches. Support staff stressed the importance of teammates supporting each other on and off the pitch throughout the camp, deemphasising competing for a starting spot and instead focusing on creating a family environment, where everyone pushed each other to reach optimal performance levels: “If a player is not starting, are they supporting the rest of the team in training? Are they providing the starting players with the realistic challenges they are going to face or are they just moaning and thinking of themselves?” (Support Staff 6).

Mental Toughness maintenance

Encountering and coping with stressors were important factors in the development of MT in international football. All participant cohorts acknowledged that reflecting on these experiences reinforced and maintained players’ MT. According to the international coaches, reflective practice is a strategy for understanding and enhancing performance that was implemented on an individual, unit-based, and team level, and was adaptable to the time demands of international football. On an individual level, coaches would often sit down with players to discuss their performance. The coaches detailed how their role was to help players understand why they made a mistake, and to learn the reflection process rather than simply reflect on individual mistakes: “Players at youth level make mistakes, but it’s about understanding why, and how they learn that reflection process through analysis” (Coach 1). Coaches positively reinforced this reflection process through emphasizing it was ok to make mistakes and “reaffirming they are good players” (Coach 1). Players discussed how working with international coaches helped foster the autonomy and capacity to think for themselves about their performances under pressure: “I’d watch the game back and think, ‘Why do I keep making those mistakes? What could I do differently?’” (Player 4). Coaches and staff also demonstrated these autonomy-supportive behaviors in unit-based reflections, where players were divided into small groups, usually position-based, to review training sessions or game clips and encouraged to share perceptions of their performances: “When we review training, we get the players to give their view first, to see if they have the solution in their head” (Support Staff 6). Unit-based reflection catered to different personalities within the squad and empowered quieter players to speak up: “Unit reflection allows you to express yourself and ask more questions if you’re not as confident as other players” (Player 5). These unit-based reflections would often link into larger team-based meetings, where players mentioned being asked to “reflect on scenarios in groups, then come together to feedback the points we discussed” (Player 3). Here, coaches emphasized a focus on “effort and tactical application as a group” (Coach 2), rather than singling out individual players in front of a group. This was to maintain trusting relationships and reinforce the family-oriented environment they were trying to create.

Discussion

MT development programmes have previously been created based on the MTbs identified as essential within specific sporting contexts (e.g., Anthony et al., Citation2018). However, little shared understanding exists of how MTbs contribute to MT development (Anthony et al., Citation2020). To address this gap, we conceptualized the MT development process in an international youth football setting and explored how MTbs are reinforced through various processes (e.g., relationships) and contexts (e.g., training versus home environment). Through multiple stakeholder interviews, we suggest MT development consists of players transacting with individuals and their environment, appraising the stressors they face (e.g., transitioning to a new organizational culture), attempting to display MTbs to cope with these stressors to support consistently high performance, and reflecting on these experiences to enhance their MT capacity when faced with future adversities. Thus, MT development is aligned with the cognitive-motivational-relational theory of stress and emotion (CMRT; Lazarus, Citation1999). Based on our findings, to develop MT, athlete’s coping strategies involve consistently displaying specific MTbs (e.g., fundamental MTbs) thus taking agentic action over their development across performance contexts. Further, while environmental demands and personal characteristics combine to influence how players behave in stressful situations, how they learn from these responses, through the processes of reflection and adaptation of underlying cognitions, affects their environmental conditions, MT development, and future MTbs (Anthony et al., Citation2016).

All MT development strategies outlined in our study relied upon relationships players had with key individuals in their support network, including coaches, parents, and teammates. Relationships were the vehicle through which athletes learned to cope with stressors in their environment, displaying MTbs, and developing the MT to perform under pressure (Lazarus, Citation1999). In international football, the highly cohesive relationship between the coach and athlete is evidenced through mutual respect, trust, and clear, honest communication, leading to successful performance (Davis et al., Citation2019). These qualities were evident within the coach-player relationships in the current study, where international coaches’ assisted players to develop their ability to perform consistently under pressure through re-appraising these pressures as challenges. Coaches outlined a structured learning process all players undergo to develop MT on the international development pathway, and the MTbs players need to display (e.g., quick recovery from mistakes) to navigate this pathway successfully. Where possible, coaches used autonomy-supportive behaviors to foster each player’s sense of control, and subsequently their motivation over their own learning and MT development (Carroll & Allen, Citation2021). However, due to the time-limited nature of international football, coaches acknowledged they often needed to display controlling behaviors to get their message across quickly. Such insights highlight the need for practitioners to be flexible when working in the time poor, solution-focused environments of high-level sport, and to accommodate these contextual needs when developing MT interventions to ensure stakeholder buy-in (Eubank et al., Citation2017). For example, when creating a punishment-based MT development programme in the time-limited context of international youth cricket, Bell et al. (Citation2013) highlighted how a high challenge-high support framework was required to adequately prepare players to perform under pressure. Within this framework, players were challenged during high-pressure training days, where they received a punishment for not matching performance expectations (e.g., cleaning the changing rooms). Alongside this, players had relaxed training days, where they were provided with opportunities to engage in workshops and received coach feedback regarding their ongoing performance. Coaches adopted a transformational leadership style during these camps, imbuing players with a clear vision of the actions they needed to take to perform to a consistently high level. As such, Bell et al. demonstrated how MT can be developed in a limited timeframe, through challenging players to perform to a consistently high level under pressure and supporting players to reach this consistently high level through delivery of a clear, context-specific vision.

Bell et al. (Citation2013) high-challenge-high support framework typifies a shift from the individualistic approach to MT development, where onus was placed on the performer to withstand pressure (e.g., Jones et al., Citation2002). To expand, pursuit of consistently high performance under pressure is not solely driven by what the individual perceives as valuable, but by what their cultural context perceives as valuable (Anthony et al., Citation2018). However, cultural influences on psychosocial development have led to conceptual issues within the MT literature, where environments in which MT is viewed as an integral part of high performance have often conceptualized the construct in unrealistic and stereotypically masculine terms, including playing through injuries, sacrificing one’s identity for the team, and hiding vulnerabilities (Coulter et al., Citation2016). Critics of this conceptualization have argued that to develop the ideal mentally tough athlete requires engagement in unethical coaching practices, including bullying and threatening deselection for lack of conformity, leading to long-term mental health issues (Bauman, Citation2016). In our study, however, all MT development strategies were underpinned by an autonomy-supportive coaching climate, with players and staff working to create an environment where individuals held each other accountable for their actions, and players are encouraged to seek guidance to develop their MT. Therefore, MT development entailed a relational, multidimensional process contingent on a range of intra-individual (i.e., MTbs, MT cognitions), inter-individual (i.e., relationships), organizational (i.e., adapting to a time poor environment) and cultural factors (i.e., adopting organizational values and beliefs).

Parents of international players also discussed the importance of autonomy-supportive behaviors and providing their child space to reflect after international matches. For example, parents reported when they discussed performances with their children, the most meaningful conversations occurred when they asked open-ended rather than closed questions (e.g., what did you think of your performance today?). Similarly, Thrower et al. (Citation2022) recorded parent and child’s pre-tennis tournament car conversations and found parents who asked open questions engaged in more constructive dialogue as they allowed their child to dictate the discussion. Such questions allow children to process their performances and develop self-knowledge regarding their ability to perform under pressure (Holt et al., Citation2021). A parent’s role within their child’s psychosocial development, however, gradually becomes secondary across talent development contexts (Amorose et al., Citation2016). This shift is due to the athlete moving from early years of engagement, where the focus is enjoyment, to the intermediate years, where the athlete becomes more reliant on their coach’s knowledge to develop resources (e.g., MT) to control their performance-related behaviors when experiencing strain (Connaughton et al., Citation2010).

Adopting a peripheral role within their child’s MT development was a major stressor for numerous parents in our study, as they grew concerned with their child’s over-investment in their football career to the detriment of their wider social development and were often kept out of the loop by international coaches concerning their child’s in-camp performances. This finding aligns with previous research in academy (youth) football, where parents reported struggling to balance supporting their child’s pursuit of a football career with protecting their child from the likely detrimental consequences of failure and felt ignored by coaches concerning their child’s psychosocial development (Harwood et al., Citation2019). If not properly managed, the strain parents experience from the uncertainty regarding their child’s international football development could detrimentally affect their child’s perception of the international football environment and capacity to display the MTbs required to perform in this environment (Lazarus, Citation1999). Consequently, parents must learn to adapt their behaviors to their child’s current emotional needs, knowing when to provide positive reinforcement or engage in healthy conflict regarding their child’s performances and MT development (Thrower et al., Citation2022).

The notion of healthy conflict was a key MT development strategy in player-player relationships too. Specifically, during performance review sessions players were often divided into smaller groups, provided with video clips highlighting positive and negative aspects of their performance, and encouraged to feedback to each other in an honest and constructive manner. These conversations often led to differing perceptions and disagreements between players within groups and required players to work together toward a mutual understanding. Collins and Cruickshank (Citation2015) highlighted how a team’s ability to enter this zone of uncomfortable debate can assist in navigating the uncertainty of high-performance sport, including overcoming injuries and adapting tactics against different opposition. Given MT in international youth football involves one’s capacity to persist toward consistently high levels of performance in the face of varying levels of stressors (Gucciardi et al., Citation2015), the ability of athletes to embrace failures and engage in healthy conflict seem fundamental to MT development. Acceptance and willingness to learn from teammates in a performance context relies on players fostering a sense of relatedness, through the creation of trusting friendships (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). Mutually caring relationships between teammates can assist athletes in managing the stressors associated with high performance sport through promoting a collaborative approach within a performance context and allowing athletes to unwind and relax away from the performance arena (Burns et al., Citation2019). The quality and quantity of relationships between teammates also contributes to a stronger sense of team social identity and collective efficacy (Shah et al., Citation2022). Our study highlights how relatedness can create an environment where players are willing to be vulnerable and honest, reframing stressors associated with international football (e.g., playing talented opposition) as a challenge and supporting each other in developing the MTbs required to consistently cope.

Previous MTb investigations have focused solely on coaches’ perceptions of the MTbs athletes require to perform consistently under pressure (e.g., Anthony et al., Citation2020; Madrigal, Citation2020) or on coaches’ assessments of MTb development (e.g., Beattie et al., Citation2019; Bell et al., Citation2013). By contrast, our study also explored the lived experiences of athletes and what they perceived MTb to look like, in- and outside of the performance environment. We found that players played an agentic role in their own MT development, choosing MTbs that allowed them to adapt to the varying levels of stressors they faced, but also behaving purposively, in line with their overarching goal of consistently high performance. Further, players acted responsibly off the pitch, developing the professional habits required to perform consistently under pressure on the pitch and supporting teammates to develop similar habits. Such findings extend previous research that certain athletes develop self-regulated MTbs in training, which then equip them to handle pressures of competition more consistently (Beattie et al., Citation2019). Our findings also build on the idea that MT is not about the characteristics one possesses, but about one’s capacity to utilize their characteristics to consistently display MTbs to cope with stressors faced within their wider environment (Coulter et al., Citation2018). Additionally, how individuals cope, or fail to cope, using MTbs can also affect environmental conditions, personal resources, and future reactions (Lazarus, Citation1999). Consequently, resources such as MT are developed and maintained through reflecting on experiences and the MTbs deployed across situations over time (Anthony et al., Citation2016). Specifically, individuals must reflect on the experience itself (what happened?), the wider meaning of the experience in relation to their goal of consistent high performance (so what does this mean?), and the MTbs they must display when encountering a similar experience in the future to develop or maintain MT (now what do I need to do?; Driscoll, Citation1994).

Engaging in reflective practice has been highlighted as a key factor in helping athlete’s develop self-efficacy, interpreting competitive anxiety as facilitative, and enhancing the goal setting procedures of teams (e.g., Neil et al., Citation2013). Reflective practice has also been identified as essential in MT’s development and maintenance (Bell et al., Citation2013; Connaughton et al., Citation2010). However, there is a lack of research highlighting how reflective practice impacts an individual’s MT development. To fill this gap, our current study outlined how coaches taught players the reflection process, helping players make sense of their experiences and take action to improve. Coaches also learned how each player perceived the game; their understanding of tactical language and their perceptions of their own performances. The importance of engaging in reflective practice to develop players’ understanding of a particular skill and ability to decisively execute that skill under competitive pressure has been well-documented (e.g., Koh & Tan, Citation2018; Richards et al., Citation2012). Further, team reflections on the development of psychological constructs such as MT can lead to the creation of shared mental models (Pierce et al., Citation2016), where players and coaches form a collaborative understanding of what MT looks like within their context. Similarly, in our study, coaches used the process of reflective practice to solidify players’ on-pitch learning and contribute to a creating a common language regarding what MT looked like (e.g., training with intensity). Researchers have previously been disconnected in this regard, outlining the importance of an athlete’s support network but failing to link these relationships in a coherent manner, with a clear blueprint for how MT should be developed through relationships and rationalizing one’s decision-making process (e.g., Anthony et al., Citation2018; Beattie et al., Citation2019). By contrast, with a foundational awareness of MT, players in our study could develop the clarity of mind to know what MTbs they needed in critical moments and learn to execute these behaviors consistently.

Implications for practice

Through this study, a shared understanding has been created of the MT development process within a UEFA National Football Association. Based on our findings, we advocate for a systems-led approach to support the development of a psychologically informed environment, where psychological concepts such as MT are understood and implemented by all stakeholders operating within the Association (cf. Wagstaff & Quartiroli, Citation2023). In this regard, creating a psychologically informed environment would involve the education of all staff within the organization regarding what MT is and the importance of displaying autonomy-supportive behaviors to support athletes’ MT development. Implementing our MT development framework would also contribute to creating an environment in which players feel comfortable when experiencing adversity and seek the support of coaches and significant others regarding both performance and personal issues, leading to an image of MT that includes embracing vulnerability (Eubank et al., Citation2017). Therefore, MT development can be viewed as a complex and long-term process, requiring the holistic support of a multidisciplinary team to create contextualized training programmes to facilitate consistent high performance under pressure.

During international camps, coaches could implement the MT development strategies outlined in , with a sport psychologist observing and nudging coach behaviors, as well as checking and challenging coaches regarding the psychological outcomes of on-pitch training and off-pitch review sessions. Through this process, coaches would learn to consistently recognize MTbs in critical moments in training and competition and reinforce the display of these MTbs in players. Players could attend workshops highlighting the importance of displaying context specific MTbs to perform consistently under pressure. Within these workshops, players could be shown videos of other players from across different international age groups displaying the required MTbs in training (e.g., active listening) and competition (e.g., constant observation). Coaches would also have a key role to play here, through role modeling MTbs (e.g., staying calm during matches) and assisting players to develop a rational decision-making process for the display of MTbs under pressure. Given the extensive time youth players spend interacting with and learning from their parents, relative to time spent in an international football environment, it is also important to educate parents on what MT is and the fundamental role they play in developing their child’s MT at home. Further, parents should be provided with potential MT development strategies to implement, such as engaging in healthy conflict when needed to support their child’s holistic development. Implementing these recommendations within international football settings would make a significant contribution toward creating a shared understanding of how MTbs can be reinforced, and how MT can be developed through various processes and contexts over time.

Summary, limitations, and future directions

From a MT development perspective, it is evident that athletes rely on a complex, interactive social network to develop the capacity to cope and consistently perform under pressure, with individual roles and relationships in this network varying across contexts and time (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006; Lazarus, Citation1999). Consequently, MT development is relational and multidimensional, relying on the creation of shared mental models regarding the MT development process (Gucciardi et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the notion that an individual’s MT capacity is developed through their transactions with stressors dovetails with the development process of similar psychological resources, such as resilience (cf. Sarkar & Page, Citation2022). By providing a thorough outline of the MT development process and the strategies required for players to both initiate and maintain their MT development via MTbs, we have provided a shared mental model for who should be developing MT (athletes, coaches, staff, parents), when and where MT should be developed (e.g., off the pitch in individual or team meetings), what should be developed (e.g., performance MTbs) and how MT should be developed through the environment (e.g., autonomy support, open communication). Nevertheless, our findings fall short of understanding how an individual uses reflective practice to make sense of their own developmental journey and the role MT plays within that journey (Clark et al., Citation2022; Coulter et al., Citation2018). For example, understanding an athlete’s capacity to persist and remain motivated under varying levels of strain (i.e., their MT), the strategies required to foster this persistence, and the behaviors they might exhibit during this persistence (i.e., MTbs) fails to explain why they seek this persistence in the first place (cf. Coulter et al., Citation2016). However, the major aim of our study was to investigate and map out the relational process of MT development within a National Football Association. In so doing, we have answered recent calls in the literature to ascertain the MT development strategies athletes require to develop the MTbs necessary to perform under pressure (Anthony et al., Citation2020; Gucciardi et al., Citation2020).

The majority of MT literature has been situated within one layer of personality, trait-based dispositions, and examined this ‘thing’ called MT with little regard for how an individual develops MT within different contexts (e.g., Jones et al., Citation2002). Our research expanded this narrow focus, through investigating MT as a characteristic adaptation; namely, how international footballers developed their underlying MT through relationships across different contexts, learning and adapting their MTbs where relevant. Therefore, researchers building on our findings are encouraged to move beyond the MT characteristics and MTbs athletes possess or develop through environmental interaction, and to instead explore athlete’s narrative identity regarding MT (Coulter et al., Citation2018). This idiographic approach to MT development would signify a shift away from the traditional nomothetic focus of MT research, and allow researchers to make sense of an athlete’s goals, values, and beliefs in driving their desire to develop MT. Further, individuals’ narratives in developing MT could be used to map out the transactional pathways of the stressors they experience on their developmental journeys, and make greater sense of their appraisal mechanisms, (i.e., relational meaning), their perceptions of their capacity to cope (i.e., MT) and the coping strategies they deploy (Lazarus, Citation1999). Finally, in the current study a clear MT development framework for international youth football was outlined, illustrating what MTbs are required by players in training, competitive, and developmental contexts, and how MT can be developed by players, coaches, and parents. Therefore, future research should focus on how this framework could be implemented in practice. Namely, when and where coaches could implement the outlined MT development strategies to clarify and reinforce MTbs for players, within international training camps (i.e., on-pitch training, off-pitch review sessions) and across age groups. Conducting such applied research will help to inform practice through highlighting how mechanisms for development of psychological resources, such as MT, can be integrated alongside technical, tactical, and physical development strategies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Amorose, A. J., Anderson-Butcher, D., Newman, T. J., Fraina, M., & Iachini, A. (2016). High school athletes’ self-determined motivation: The independent and interactive effects of coach, father, and mother autonomy support. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 26, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.05.005

- Anthony, D. R., Gordon, S., & Gucciardi, D. F. (2020). A qualitative exploration of mentally tough behaviour in Australian football. Journal of Sports Sciences, 38(3), 308–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2019.1698002

- Anthony, D. R., Gordon, S., Gucciardi, D. F., & Dawson, B. (2018). Adapting a behavioural coaching framework for mental toughness development. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 9(1), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2017.1323058

- Anthony, D. R., Gucciardi, D. F., & Gordon, S. (2016). A meta-study of qualitative research on mental toughness development. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 9(1), 160–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2016.1146787

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

- Bauman, N. J. (2016). The stigma of mental health in athletes: Are mental toughness and mental health seen as contradictory in elite sport? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(3), 135–136. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095570

- Beattie, S., Alqallaf, A., Hardy, L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2019). The mediating role of training behaviours on self-reported mental toughness and mentally tough behavior in swimming. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 8(2), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000146

- Bell, J. J., Hardy, L., & Beattie, S. (2013). Enhancing mental toughness and performance under pressure in elite young cricketers: A 2-year longitudinal intervention. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 2(4), 281–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033129

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol 1. Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). John Wiley.

- Burns, L., Weissensteiner, J. R., & Cohen, M. (2019). Supportive interpersonal relationships: a key component to high-performance sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(22), 1386–1389. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-100312

- Carroll, M., & Allen, J. (2021). Zooming in’ on the antecedents of youth sport coaches’ autonomy-supportive and controlling interpersonal behaviours: a multimethod study. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 16(2), 236–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954120958621

- Clark, J. D., Mallett, C. J., & Coulter, T. J. (2022). Personal strivings of mentally tough Australian Rules footballers. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 58, 102090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102090

- Clough, P., Earle, K., & Sewell, D. (2002). Mental toughness: The concept and its measurement. In I. Cockerill. (Ed.), Solutions in sport psychology (pp. 32–45). Thomson.

- Collins, D., & Cruickshank, A. (2015). Take a walk on the wild side: Exploring, identifying, and developing consultancy expertise with elite performance team leaders. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.002

- Collins, D. J., & Macnamara, A. (2017). Making champs and super-champs. Current views, contradictions, and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 823. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00823

- Connaughton, D., Hanton, S., & Jones, G. (2010). The development and maintenance of mental toughness in the world’s best performers. The Sport Psychologist, 24(2), 168–193. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.24.2.168

- Coulter, T. J., Mallett, C. J., & Singer, J. A. (2016). A subculture of mental toughness in an Australian Football League club. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 22, 98–113. http://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2015.1016085

- Coulter, T. J., Mallett, C. J., & Singer, J. A. (2018). A three‐domain personality analysis of a mentally tough athlete. European Journal of Personality, 32(1), 6–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2129

- Coulter, T. J., & Thelwell, R. C. (2019). Mental toughness development in football. In E. Konter, J. Beckmann, & T. M. Loughead (Eds.), Football psychology: From theory to practice (pp. 23–37). Routledge.

- Davis, L., Jowett, S., & Tafvelin, S. (2019). Communication strategies: The fuel for quality coach-athlete relationships and athlete satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2156. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02156

- Diment, G. M. (2014). Mental toughness in soccer: A behavioral analysis. Journal of Sport Behavior, 37(4), 317–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1382019

- Driscoll, M. P. (1994). Psychology of learning for instruction. Allyn & Bacon.

- Eubank, M. R., Nesti, M. S., & Littlewood, M. A. (2017). A culturally informed approach to mental toughness development in high performance sport. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 48(3), 206–222. https://doi.org/10.7352/IJSP2017.48.1

- Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts and theory. European Psychologist, 18(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

- Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2016). Mental fortitude training: An evidence-based approach to developing psychological resilience for sustained success. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 7(3), 135–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2016.1255496

- Gucciardi, D. F. (2017). Mental toughness: progress and prospects. Current Opinion in Psychology, 16, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.010

- Gucciardi, D. F., Gordon, S., & Dimmock, J. A. (2008). Towards an understanding of mental toughness in Australian football. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 20(3), 261–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200801998556

- Gucciardi, D. F., Hanton, S., Gordon, S., Mallett, C. J., & Temby, P. (2015). The concept of mental toughness: Tests of dimensionality, nomological network, and traitness. Journal of Personality, 83(1), 26–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12079

- Gucciardi, D. F., Tenenbaum, G., & Eklund, R. C. (2020). Mental toughness: Taking stock and considering new horizons. Handbook of Sport Psychology. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119568124.ch6

- Hardy, L., Bell, J., & Beattie, S. (2014). A neuropsychological model of mentally tough behaviour. Journal of Personality, 82(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12034

- Harwood, C. G., Knight, C. J., Thrower, S. N., & Berrow, S. R. (2019). Advancing the study of parental involvement to optimise the psychosocial development and experiences of young athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.01.007

- Holt, N. L., Jørgensen, H., & Deal, C. J. (2021). How do sport parents engage in autonomy-supportive parenting in the family home setting? A theoretically informed qualitative analysis. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 43(1), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2020-0210