ABSTRACT

The current study evaluated the impact of an interactive website on first-year students’ self-efficacy and intentions to engage in self-help behaviors. After an initial visit to the site, students randomly assigned to a high-exposure condition were directed to content on the website an additional two time. Low-exposure groups were not instructed to re-visit the site. Students in the high-exposure group intended to engage in significantly more self-help behaviors (e.g., yoga, journaling) than those in the low-exposure group. Self-efficacy did not differ significantly by condition, however, for students of color, interaction with the website was associated with increased self-efficacy to seek help for stresses and challenges experienced while on campus. Results suggest that online resources that utilize culturally specific content and focus on developing skills may be effective in improving students’ well-being.

Introduction

College students are suffering stress, anxiety, and depression at alarmingly high rates (Abrams, Citation2022, Casey et al., Citation2022, Eisenberg et al., Citation2013, Zivin et al., Citation2009). Students’ help-seeking behaviors for their mental health care are also limited, with many students lacking the skills and confidence that enable them to make positive changes to maintain well-being or to utilize appropriate in-person services on campus (Gulliver et al., Citation2010, Jorm et al., Citation1997). These findings are concerning, given the variety of academic, social, and health problems that can occur when preventive actions are not taken and mental health issues are left untreated (Hysenbegasi et al., Citation2005, Breslau et al., Citation2008).

To address these concerns, online interventions designed to promote well-being and resilience among college students have grown significantly in the past decade (Davies et al., Citation2014). An example of such intervention is the Student Resilience Project (Oehme et al., Citation2020). The Student Resilience Project is an interactive website that promotes well-being to first-year students through wellness information, skill-building exercises, and connections to institution-wide mental health and wellness services. Prior studies have demonstrated that students respond favorably to the website, however studies evaluating the impact of such a program on student wellness is limited (Ray et al., Citation2019, Ray et al. Citation2021). The goal of the current study, therefore, was to determine the impact of the website as an intervention to improve students’ well-being.

Online interventions for mental health and wellness

The emergence of online mental health and wellness interventions has changed the nature of help-seeking by lifting the barriers of high costs and limited accessibility associated with in-person services. This is particularly true for young adults attending college, who are likely to turn to the internet for answers when concerned with their mental health and general well-being (Batterham & Calear, Citation2017). More than 60% of college students in the United States are willing to use online mental health and wellness resources (Dunbar et al., Citation2018). This includes students with elevated levels of psychological distress, who are often more reluctant to seek professional help (Eisenberg et al., Citation2009). Importantly, these students favor resources that focus on improving mental health through prevention, in contrast to focusing on treating acute mental disorders (Reivich et al., Citation2013).

Prior research suggests that online interventions aimed at prevention are effective when they provide students with information about the challenges that they are likely to encounter in college and teach them the necessary skills that can help overcome them (Walker & Frazier, Citation1993). Meta-analytic evidence indicates that such interventions can lead to substantial reductions in depression, anxiety, and general psychological distress among college students, but that their effectiveness varies (Conley et al., Citation2016). Interventions grounded in behavior change theory tend to be the most successful, as well as interventions that incorporate skill-training and development (Steinmetz et al., Citation2016, Conley et al., Citation2013).

One reason skill-development and behavior change are crucial components to the success of online interventions is that they instill confidence in students to engage in self-help behaviors. The confidence in one’s ability to perform a specific behavior is also referred to as self-efficacy. According to Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), self-efficacy influences “how much effort people expend and how long they persist in the face of obstacles and aversive experiences” (Bandura, Citation1977, p. 194). A substantial amount of research has demonstrated that people with greater self-efficacy beliefs about a particular behavior are more likely to master that behavior (Smith, Citation1989). For example, someone who holds strong beliefs about their ability to learn and perform yoga poses is more likely to sign-up for their first yoga class. Importantly, engaging in these types of self-help behaviors makes individuals more resilient to stressful situations in the future (Schwarzer & Warner, Citation2013).

According to Bandura (Citation1986), individuals with stronger self-efficacy beliefs are more likely to engage in adaptive coping behaviors to manage stress. In support, prior research suggests that interventions that focus on enhancing self-efficacy may be effective at improving student well-being through coping and help-seeking behaviors. For example, positive outcomes associated with a mobile-phone and web intervention for depression, anxiety, and stress were explained by increases in participants’ self-efficacy beliefs about managing their mental health (Clarke et al., Citation2014). Similarly, the effects of a suicide prevention program on help-seeking behaviors were explained by participants’ self-efficacy beliefs to perform help-seeking behaviors (King et al., Citation2011). Taken together, these findings indicate if an intervention enhances self-efficacy beliefs related to the content of that intervention, then a person’s intention to engage in related behaviors (e.g., self-help) is likely to follow.

The student resilience project

The Student Resilience Project is an interactive, multimedia website that offers wellness and mental health information to college students through instructional videos, skill-building activities, links to campus resources and mental-health information, and TED-talk style podcasts by campus experts on topics such as support for students of color, managing grief and loss, and support for LGBTQ+ students. The website is freely accessible to any student attending Florida State University. It was developed in 2018 with the aim of helping first-year students deal with the challenges that they may experience during their transition to college life (e.g., rejection, academic challenges). Since then, additional content has been added to the site to address COVID-19 and campus-wide concerns related to racism, sexism, and homophobia. The website itself was designed to be easy to navigate, visually engaging, and highly interactive. For more information about the development of the Student Resilience Project website, see Oehme et al. (Citation2019) and Oehme et al. (Citation2020).

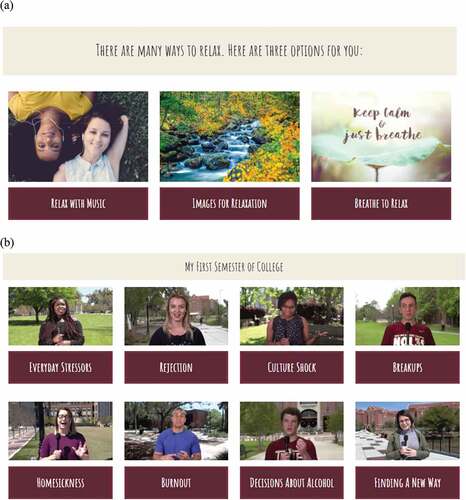

The two most popular (frequently visited) sections on the site, according to site analytics, are called “Learn New Skills” and “What I Wish I Knew (my first semester of college).” Sample screenshots of both sections are provided in .

Figure 1 Sample Screenshots from the Student Resilience Project Website: (a) Learn New Skills and (b) What I Wish I Knew

The “Learn New Skills” component offers students information about skill-building behaviors (e.g., yoga, mindfulness, journaling) that help them manage stress and improve coping skills. According to SCT (Bandura, Citation2004), communication to inspire preventive behaviors is most effective when focused on skill acquisition. When people are provided with information about the skills required to perform a healthy behavior, they can become more confident in their own ability to perform it. The “Learn New Skills” section is designed to encourage students to learn about, develop confidence about (self efficacy), and eventually practice self-help behaviors. For example, first-year students interested in learning yoga are provided a detailed description of how yoga impacts well-being, a video demonstrating yoga poses for beginners, and links to information about online and in-person yoga classes available through the university.

The “What I Wish I Knew” component includes eight brief videos that feature students from the university recounting challenges they faced early in their college careers and explaining how they overcame them with the assistance of a variety of institutional resources (Oehme et al., Citation2019, Oehme et al., Citation2020). For example, in one video, a student describes feeling homesick during her first semester in college and how she was able to overcome it by forming connections with other new students on campus. At the end of each video, links to campus resources for the given challenge are provided. Such videos serve as peer-to-peer restorative narratives (Dahmen, Citation2016, Fitzgerald et al., Citation2020), which, by providing models of strength and resilience for viewers, can increase viewer perceptions of their own resilience (efficacy) as well as perceptions that taking actions recommended (or demonstrated) by those in videos will be efficacious (Ray et al., Citation2019, Bandura, Citation2004). Research indicates that this style of narrative storytelling, which features authentic voices and focuses on hope amid adversity, can evoke positive emotion and increase prosocial behavior (Fitzgerald et al., Citation2020).

The study, a randomized controlled trial (RCT), evaluated the Student Resilience Project website on two outcomes: self-efficacy and behavior intentions. As mentioned previously, content that focuses on modeling resilience and skill development have shown to increase students’ self-efficacy and their likelihood to engage in self-help behaviors to manage stress (Ray et al., Citation2021, Weare and Nind, Citation2011, Bandura, Citation1986). Therefore, it was expected that students that interacted with the website would show greater (H1) self-efficacy to handle or seek help for stresses and challenges experienced while on campus and (H2) greater intent to engage in self-help behaviors, compared to students who did not interact with the website.

Vulnerable student groups

An additional purpose of the current study was to investigate the effectiveness of the Student Resilience Project website among vulnerable student groups, particularly students of color and sexual minority students. In terms of their mental health needs, college students of color remain an underserved population. Results from a survey of students from 60 colleges and/or universities in the United States revealed that students of color are less likely to seek out treatment for their mental health than white students, despite the high prevalence of mental health problems in both groups (Lipson et al., Citation2018). Many factors likely contribute to this disparity, but evidence suggests that self-efficacy beliefs play an important role. For example, Mesidor and Sly (Citation2014) found that self-efficacy beliefs associated with seeking mental health services significantly predicted African American students’ intentions to seek mental health services, even above and beyond psychological distress.

Sexual minority students represent another underserved population with respect to mental health. Compared to heterosexual students, gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender students are disproportionately affected by mental and substance abuse disorders, often as a direct result of discrimination against them (Gonzales et al., Citation2016). While sexual minority adults are more likely to utilize mental health services than heterosexual adults, their satisfaction with these services is low (McNair et al., Citation2011). Moreover, college resources that include targeted content to sexual minority students are limited (Wright & McKinley, Citation2010).

Since it was originally developed, the Student Resilience Project continued to add culturally specific content to address the needs and concerns of students of color and sexual minority students. For example, the “What I Wish I Knew” section of the website includes a video restorative narrative of a Black student describing her experience of culture shock when joining a predominantly white institution. The “What I Wish I Knew” section also includes a video restorative narrative of an LGBTQ+ student describing the difficulties that he experienced breaking up with his same-sex partner. In general, content on the site is presented to communicate to students that the university’s administration, faculty, and staff understand equity issues and want to connect them to helpful resources. For example, there is multi-media, featuring students from diverse backgrounds, focused on “resilience in diversity” that highlights the importance of different values and life experiences on campus. Instructional information on how to access the relevant resources is also provided to enhance self-efficacy among these students and to increase their use of those resources.

Given the above-described needs of students of color and sexual minority students, it seemed possible that the site, which included locally produced content that was tailored to many of their concerns, might be especially influential among vulnerable students who interacted with it. Therefore, the following research questions were posed: Will vulnerable students’ (RQ1) self-efficacy and (RQ2) intentions to engage in self-help activities be affected by interaction with the Student Resilience Project compared to their counterparts?

Methods

Participants

Participants were a convenience sample of first-year students enrolled at a large public institution in southeastern United States, in the 2021–2022 school year. An a priori power analysis indicated that a sample size of 210 participants was needed to achieve 80% power to detect a medium effect size (f = .25) at α = .05 for comparisons between conditions at two measurement points while controlling for baselines scores. We elected to over-sample in anticipation of a high dropout rate. Of the 936 participants who provided baseline data, 247 completed the study (low-exposure = 148; high-exposure = 99). Twenty-one of these participants indicated they were not first-year and were removed from analyses. An additional 10 participants were removed from analyses because they failed more than two attention checks items (i.e., low response time, honesty check) (Abbey Meloy & Meloy, Citation2017). Therefore, the final sample consisted of a total of 216 participants (low-exposure = 125; high-exposure = 91). provides a summary of the demographics for the final sample of participants, as well as separate summaries for participants assigned to the high-exposure and low-exposure groups. The mean age of the final sample was 18.10 (SD = .30).

Table 1 Sample Demographics

Procedure

Students were initially recruited early in the fall semester, through the online Student Resilience Project website. The website is promoted to first year students through administrative e-mail notices, social media posts, and posters displayed around campus. All first-year are required to visit the site once during their first semester. Before leaving the website after an initial visit that students scheduled on their own, students were asked if they would be willing to complete an online, multi-part study for Amazon gift cards. If students consented to participate, they were directed to an initial questionnaire hosted by Qualtrics survey software that assessed their demographics and baseline measures of self-efficacy and intentions to engage in self-help behaviors as well as their demographic and individual characteristics. Upon completion of the initial questionnaire, participants were compensated with a $5 Amazon gift card.

Participants who completed the initial questionnaire were then randomly assigned to the high-exposure or low-exposure conditions. To match responses to baseline outcomes, all participants were assigned a unique three-digit code. Because all first-year students (and, essentially, those who could be recruited for the current study) were required to visit the site at least once, the high-exposure condition in this study manipulated the amount of exposure to the site by increasing it after the first exposure among participants in that condition. Participants in the high-exposure condition were directed to view content on the Student Resilience Project website at two follow-up times. At those follow-up times, participants were asked to revisit two sections of the site. We focused participants’ attention on two sections of the site (1) to limit participant fatigue, and (2) so that the exposure to specific site content would be consistent among participants within the high-exposure group, allowing for a greater understanding of study outcomes. The two sections of the site that were chosen were the most popular ones on the site in the months preceding this study. Specifically, participants in the high-exposure group were instructed to visit/view at least two “What I Wish Knew (my first semester of college)” restorative narrative videos and at least two “Learn New Skills” activities (see literature review for a description of each section). Participants were then asked to describe two lessons or facts they learned while viewing content from each section. These responses were reviewed later by the research team to ensure that participants viewed and sufficiently attended to the material. Participants in the low-exposure condition were not instructed to view the site again or to view any content from it. At the two follow-up times, they were merely asked to describe two lessons or facts they learned from their classes over the past week. Upon completion of their respective tasks, all participants completed outcome measures and were compensated with a $10 Amazon gift card.

The above procedure was repeated twice: two weeks and four weeks after the initial site visit and questionnaire. Multiple implementations of the treatment were administered to increase the likelihood that participants in the high-exposure condition sufficiently engaged with the content on the website. It is important to note that while outcome measures were administered after each website interaction, the primary interest of the study was outcome scores at four weeks after the initial visit (i.e., post-intervention).

Measures

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy to seek help for stresses and challenges experienced while on campus was measured with five items (α = .91). The wording of each item was changed to reflect the university that participants attended. Sample items included: “I feel like I could take effective actions to deal with personal struggles or challenges with emotional, mental, or physical wellness that I might experience while I am a student at Florida State University” and “If/when I experience personal struggles or challenges with emotional, mental, or physical wellness, I can easily use resources that are available through Florida State University to get help.” Responses for each item ranged from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree. Items were averaged to create a scale (α = .93).

Intention to engage in self-help behaviors

To measure intention to engage in self-help behaviors, participants were asked to select the self-help behaviors they were likely to do within the next month. A list of ten self-help behaviors were presented to them. Seven items were mentioned explicitly in the Student Resilience Project content (e.g., journaling, yoga, breathing skills) and three items were used as distractors. Participants were instructed to select the self-help behaviors they were likely to do within the next month. The seven behaviors related to the Student Resilience Project content were summed to create a total score.

Demographics

Participants were asked to identify their age, gender, racial group, sexual orientation, and class standing.

Site interaction

Although only participants assigned to the high-exposure group were directed to back to the website after their initial visit, all participants had access to it during the study period. To ensure participants in the high-exposure condition interacted with the website on more occasions than participants in the low-exposure condition, all participants were asked to report the total number of times they visited the website within the last three months after the initial visit.

Data analysis

All data analysis procedures were conducted with SPSS 25. Independent t-tests and chi-square tests were used to conduct a randomization check and dropout analysis. A series of analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted to examine our primary hypotheses, namely whether scores on self-efficacy (H1) and intention to engage in self-help behaviors (H2) differed significantly between conditions, while controlling for baseline scores. The analytic strategy decision was based on Locascio and Atri’s (Citation2011) recommendations for analyzing data with a continuous dependent variable, a continuous covariate, and a between-subjects predictor variable. Specifically, self-efficacy (and intention to engage in self-help behaviors) was entered into the model as a dependent variable, baseline scores on self-efficacy (and intention to engage in self-help behaviors) entered as the covariate, and condition (low-exposure; high-exposure) was entered as the between-subjects predictor.

Secondary analyses were conducted to examine whether the effect of the high-exposure condition on the outcome measures differed by race/ethnicity (RQ1) and sexual orientation (RQ2). Race/ethnicity (white; nonwhite) and sexual orientation (heterosexual; sexual minority) were dummy-coded and included in the model as between-subject factors. The alpha value used to determine significance was p < .05 for all primary and secondary analyses. Bonferroni corrections were made to adjust for multiple comparisons when examining conditional effects.

Results

Preliminary analyses

The dropout rate, defined as lost to post-intervention, was 73.61% (689/936). A Little test (Little & Rubin, Citation2019) was nonsignificant, χ2 (237) = 252.63, p = .231 indicating that the assumption held that data were missing completely at random (MCAR). Under this assumption, a complete case analysis is unbiased (Pugh et al., Citation2022). Baseline comparisons between conditions revealed no significant differences in participants’ gender (man; women; other), χ2 (216) = 1.89, p =.389, participants’ race/ethnicity (white; nonwhite), χ2 (216) = 3.45, p =.063, participants’ sexual orientation (heterosexual; sexual minority), χ2 (216) = .19, p =.667, and intentions to engage in self-help behaviors at baseline, t(215) = 1.16, p = .245. However, there were significant differences between conditions on self-efficacy at baseline, t(215) = 2.23, p = .027. Specifically, participants in the low-exposure condition reported significantly greater self-efficacy at baseline than participants in the high-exposure condition.

Main effects of site interaction

Means and standard deviations for all outcome measures at baseline and post-intervention are provided in . As expected, participants in the high-exposure condition (M = 2.96 SD = 1.53) reported visiting the website on more occasions than those in the low-exposure condition (M = 2.40, SD = 1.37), t(214) = 2.41, p = .017. Of note, there was a significant, positive correlation between site interaction and self-efficacy (r = .34) and site interaction and intentions to engage in self-help behaviors (r = .18).

Table 2 Mean and Standard Errors for the Low-Exposure and High-Exposure Conditions at Baseline and Post-Intervention

show the effect of condition on self-efficacy and intentions to engage in self-help behaviors post-intervention, controlling for baseline measures. There were no significant differences in self-efficacy between the high-exposure condition (Madj = 4.21, SE = .06) and low-exposure condition (Madj = 4.11, SE = .06), F(1, 213) = 1.42, p = .235, ηp2 = .01. However, there was a main effect of condition on intentions to engage in self-help behaviors, F (1, 213) = 7.92, p = .005, ηp2 = .04. That is, compared to participants in the low-exposure condition (Madj = 2.18, SE = .11), participants in the high-exposure condition (Madj = 2.66, SE = .13) intended to engage in more self-help behaviors.

Effects of site interaction among vulnerable student groups

When race/ethnicity was added as a between-subjects factor, a significant interaction effect between race/ethnicity and condition emerged for self-efficacy, F(1, 211) = 13.96, p < .001, ηp2 = .06. Post hoc tests revealed that participants who identified as nonwhite in the high-exposure condition (Madj = 4.37, SE = .08) reported significantly greater self-efficacy than participants who identified as nonwhite in the low-exposure condition (Madj = 4.02, SE = .09, p = .003, ηp2 = .04. Conversely, participants who identified as white in the high-exposure condition (Madj = 4.19, SE = .08) did not differ significantly from participants who identified as white in the low-exposure condition (Madj = 4.05, SE = .08) on self-efficacy, p = .157, ηp2 = .01. The interaction effect between race/ethnicity and condition predicting intentions to engage in self-help behaviors was nonsignificant, F(1, 211) = .04, p = .852, ηp2 = .00 ().

Figure 4 The Interaction Between Condition and Race/Ethnicity Predicting participants’ Self-Efficacy at Post-Intervention Controlling for Baseline Score

When sexual orientation was added as a between-subjects factor, the interaction effect between sexual orientation and condition was nonsignificant for self-efficacy, F(1, 211) = .05, p = .817, ηp2 = .00 and was nonsignificant for intentions to engage in self-help behaviors, F(1, 211) = .08, p = .776, ηp2 = .00.

Discussion

In response to the high prevalence rate and severity of mental health problems, several higher education institutions have implemented web-based interventions that promote well-being and resilience (Davies et al., Citation2014). Prior research suggests that interventions that focus on encouraging students to seek out mental health and wellness resources and engage in preventative behaviors to reduce stress may be particularly effective at improving student well-being (Reivich et al., Citation2013, Clarke et al., Citation2014). The objective of the present study was to evaluate the impact of an interactive website on first-year students’ self-efficacy and intentions to engage in self-help behaviors. Our findings suggest that such a website may have beneficial effects, particularly for students of color.

For students of color (e.g., African American, Hispanic/Latinx), interaction with the website was associated with a significant increase in self-efficacy to seek help for stresses and challenges experienced while on campus. As previous research has found that college students of color are less likely to seek out treatment for their mental health (Lipson et al., Citation2018), this is a notable finding. It also supports prior research that suggests tailoring mental health and wellness content to different racial groups is important in impacting behavior change (Kreuter et al., Citation2003). Conversely, interaction with the website did not lead to significant differences in self-efficacy for sexual minority students. Previous studies have demonstrated that LGBTQ+ students are disproportionally affected by mental health concerns (Gonzales et al., Citation2016) and may need additional resources in college to overcome stress and stigma (Johns et al., Citation2019). Therefore, future RCTs and outcome studies are needed to determine how to deliver mental health and wellness resources most effectively to this population.

In general, students who interacted with the website intended to engage in more self-help behaviors than students who did not interact with the website. These included behaviors such as yoga, journaling, and meditation, which have been shown to improve mental and physical health (Jorm & Griffiths, Citation2006). This finding lends support to the notion that information that focuses on skill acquisition (i.e., “Learn New Skills”) may be effective at inspiring behavior change.18 It is also important to note that the current study captured students’ intent to engage in these behaviors but not whether they actually engaged in them. Despite theoretical and empirical evidence demonstrating a strong link between intention and behavior, not all self-help behavior intentions are actualized (Sheeran et al., Citation2016, Webb & Sheeran, Citation2006). Nonetheless, future research should aim to capture the effects of such interventions on intentions and actual self-help behaviors.

In addition, because first-year students at the university at which this study was conducted were required to participate in the intervention/visit the site at least once, the current study utilized a convenience sample of college students. Such samples limit generalizability. Future studies should, if possible, utilize random sampling methods to enable researchers to generalize findings to other populations. Findings from the current study suggest that it may be worthwhile to investigate larger samples of other categories of vulnerable students (e.g., students with disabilities) as these students may benefit most from such an intervention.

Another important limitation of the current study was the potential for diffusion of treatment. Although only participants assigned to the experimental condition were directed to the website on multiple occasions, participants in the low-exposure condition could have accessed it (and clearly did so) during the study period. This was unavoidable given the university requirement of making the website available to all students. Although participants in the high-exposure condition reported visiting the website significantly more often than participants in the control condition, that difference was less than one visit. It is worth noting that diffusion tends to equalize outcomes between conditions, and therefore, results in the current study likely underestimated effects of the website (Trochim & Donnelly, Citation2007). One potential method to minimize the threat of intervention diffusion in future studies would be to examine effects at the school-level (i.e., comparing schools that have implemented the website versus schools that have not). Such a study would also provide the opportunity to measure the effects of the website on school-wide indicators of student well-being (e.g., course completion rate).

Finally, while nearly half of our sample identified as nonwhite, it’s noteworthy that most participants identified as female and heterosexual. This composition posed a challenge in terms of conducting meaningful demographic comparisons. To address this limitation, we encourage future researchers to gather more diverse samples, allowing for the exploration of potentially vulnerable subgroups (e.g., nonwhite and non-heterosexual students).

Practical implications

This study has several practical implications. First, multiple exposures to website content aimed at promoting student well-being may be critical for influencing behavior change. For example, prior research on the effects of health campaigns indicates behavior change is better facilitated by multiple exposures to a diverse array of relevant messages over time (Atkin & Rice, Citation2013). Accordingly, sites such as this should be refreshed and repeatedly promoted to students to achieve sufficient student exposure to the content. Return interactions can be encouraged through campus campaign messages (posters, e-mail, and social media) and through partnerships with faculty and staff who can help promote such sites to students via interpersonal communication. Student peer groups that initially promote this or similar sites (such as the peer groups that engage in peer-to-peer promotion of this Student Resilience Project and site) can encourage students to return to it again to gain more confidence and learn more about the many resources on campus available to them.

Moreover, students of color who were repeatedly exposed to the website expressed greater self-efficacy to seek help. Because the Student Resilience Project is web-based, it is relatively easy for administrators of the site to directly add content related to the challenges experienced by underrepresented students on campus (e.g., news about campus groups for underrepresented students, information about training that faculty and staff receive on equity issues and inclusive class dynamics). Such content might help these underserved students feel more supported and empowered to seek help when they need it.

Conclusion

In summary, the results of the current study suggest that a website that promotes well-being may increase the likelihood that college students will engage in self-help behaviors to manage stress. In addition, the website may help students of color increase confidence to seek help for stresses and challenges that they experience while on campus. Moreover, as studies on this and similar projects continue, the need for increased emphasis on multiple uses of such resources might be required to enhance students’ sense of self-efficacy over time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Abbey Meloy, J. D., & Meloy, M. G. (2017). Attention by design: Using attention checks to detect inattentive respondents and improve data quality. Journal of Operations Management, 53-56(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2017.06.001

- Abrams, Z. (2022, October 12). Student mental health is in crisis. Campuses are rethinking their approach. Monitor on Psychology, 53(7). https://www.apa.org/monitor/2022/10/mental-health-campus-care

- Atkin, C. K., & Rice, R. E. (2013). Public communication campaigns—the American experience. In R. E. Rice & C. K. Atkin (Eds.), Public communication campaigns (pp. 20–33). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bandura, A. (1986). Fearful expectations and avoidant actions as coeffects of perceived self-inefficacy. The American Psychologist, 41(12), 1389–1391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.12.1389

- Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 31(2), 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660

- Batterham, P., & Calear, A. L. (2017). Preferences for internet-based mental health interventions in an adult online sample: Findings from an online community survey. JMIR Mental Health, 4(2), e26–e26. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.7722

- Breslau, J., Lane, M., Sampson, N., & Kessler, R. C. (2008). Mental disorders and subsequent educational attainment in a US national sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 42(9), 708–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.016

- Casey, S., Varela, A., Marriott, J. P., Coleman, C. M., & Harlow, B. L. (2022). The influence of diagnosed mental health conditions and symptoms of depression and/or anxiety on suicide ideation, plan, and attempt among college students: Findings from the healthy minds study, 2018–2019. Journal of Affective Disorders, 298(Pt A), 464–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.jad.2021.11.006

- Clarke, J., Proudfoot, J., Birch, M.-R., Whitton, A. E., Parker, G., Manicavasagar, V., Harrison, V., Christensen, H., & Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. (2014). Effects of mental health self-efficacy on outcomes of a mobile phone and web intervention for mild-to-moderate depression, anxiety and stress: Secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 272–272. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0272-1

- Conley, C. S., Durlak, J. A., & Dickson, D. A. (2013). An evaluative review of outcome research on universal mental health promotion and prevention programs for higher education students. Journal of American College Health, 61(5), 286–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2013.802237

- Conley, C. S., Durlak, J. A., Shapiro, J. B., Kirsch, A. C., & Zahniser, E. (2016). A meta-analysis of the impact of universal and indicated preventive technology-delivered interventions for higher education students. Prevention Science, 17(6), 659–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0662-3

- Dahmen, N. (2016). Images of resilience: The case for visual restorative narrative. Visual Communication Quarterly, 23(2), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/15551393.2016.1190620

- Davies, E. B., Morriss, R., & Glazebrook, C. (2014). Computer-delivered and web-based interventions to improve depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being of university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(5), e130–e130. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3142

- Dunbar, M. S., Sontag-Padilla, L., Kase, C. A., Seelam, R., & Stein, B. D. (2018). Unmet mental health treatment need and attitudes toward online mental health services among community college students. Psychiatric Services, 69(5), 597–600. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700402

- Eisenberg, D., Downs, M. F., Golberstein, E., & Zivin, K. (2009). Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Medical Care Research and Review, 66(5), 522–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558709335173

- Eisenberg, D., Hunt, J., & Speer, N. (2013). Mental health in American colleges and universities: Variation across student subgroups and across campuses. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 201(1), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31827ab077

- Fitzgerald, K., Paravati, E., Green, M. C., Moore, M. M., & Qian, J. L. (2020). Restorative narratives for health promotion. Health Communication, 35(3), 356–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1563032

- Gonzales, G., Przedworski, J., & Henning-Smith, C. (2016). Comparison of health and health risk factors between lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults and heterosexual adults in theUnited States: Results from the national health interview survey. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(9), 1344–1351. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3432

- Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1), 113–113. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-113

- Hysenbegasi, A., Hass, S. L., & Rowland, C. R. (2005). The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 8(3), 145.

- Johns, M. M., Poteat, V. P., Horn, S. S., & Kosciw, J. (2019). Strengthening our schools to promote resilience and health among LGBTQ youth: Emerging evidence and research priorities from the state of LGBTQ youth health and wellbeing symposium. LGBT Health, 6(4), 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2018.0109

- Jorm, A., & Griffiths, K. M. (2006). Population promotion of informal self-help strategies for early intervention against depression and anxiety. Psychological Medicine, 36(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291705005659

- Jorm, A., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B., & Pollitt, P. (1997). Mental health literacy: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical Journal of Australia, 166(4), 182–186. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140071.x

- King, K., Strunk, C. M., & Sorter, M. T. (2011). Preliminary effectiveness of surviving the teens® suicide prevention and depression awareness program on adolescents’ suicidality and self-efficacy in performing help-seeking behaviors. The Journal of School Health, 81(9), 581–590. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00630.x

- Kreuter, M. W., Lukwago, S. N., Bucholtz, D. C., Clark, E. M., & Sanders-Thompson, V. (2003). Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: Targeted and tailored approaches. Health Education & Behavior, 30(2), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198102251021

- Lipson, S. K., Kern, A., Eisenberg, D., & Breland-Noble, A. M. (2018). Mental health disparities among college students of color. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(3), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.04.014

- Little, R. J., & Rubin, D. B. (2019). Statistical analysis with missing data (3rd) ed. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119482260

- Locascio, J. J., & Atri, A. (2011). An overview of longitudinal data analysis methods for neurological research. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra, 1(1), 330–357. https://doi.org/10.1159/000330228

- McNair, R., Szalacha, L. A., & Hughes, T. L. (2011). Health status, health service use, and satisfaction according to sexual identity of young Australian women. Women’s Health Issues, 21(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2010.08.002

- Mesidor, J. K., & Sly, K. F. (2014). Mental health help-seeking intentions among international and African American college students: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of International Students, 4(2), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v4i2.474

- Oehme, K., Clark, J., Perko, A., Ray, E.C., Arpan, L., & Bradley, L. (2019). A trauma-informed approach to building college students’ resilience. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 16(1), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/23761407.2018.1533503

- Oehme, K., Perko, A., Altemus, A., Ray, E.C., Arpan, L., & Clark, J. (2020). Lessons from a student resilience project. Journal of College Student Development, 61(3), 396–399. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2020.0037

- Pugh, S. L., Brown, P. D., & Enserro, D. (2022). Missing repeated measures data in clinical trials. Neuro-Oncology Practice, 9(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npab043

- Ray, E. C., Arpan, L., Oehme, K., Perko, A., & Clark, J. (2019). Testing restorative narratives in a college student resilience project. Innovative Higher Education, 44(4), 267–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10755-019-9464-4

- Ray, E. C., Arpan, L., Oehme, K., Perko, A., & Clark, J. (2021). Helping students cope with adversity: The influence of a web-based intervention on students’ self-efficacy and intentions to use wellness-related resources. Journal of American College Health, 69(4), 444–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2019.1679818

- Reivich, K., Gillham, J. E., Chaplin, T. M., & Seligman, M. E. (2013). From helplessness to optimism: The role of resilience in treating and preventing depression in youth. In Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 201–214). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3661-4_12

- Schwarzer, R., & Warner, L. M. (2013). Perceived self-efficacy and its relationship to resilience. In Resilience in children, adolescents, and adults (pp. 139–150). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4939-3_10

- Sheeran, P., Maki, A., Montanaro, E., Avishai-Yitshak, A., Bryan, A., Klein, W. M. P., Miles, E., & Rothman, A. J. (2016). The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 35(11), 1178–1188. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000387

- Smith, R. E. (1989). Effects of coping skills training on generalized self-efficacy and locus of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 228–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.228

- Steinmetz, H., Knappstein, M., Ajzen, I., Schmidt, P., & Kabst, R. (2016). How effective are behavior change interventions based on the theory of planned behavior?: A three-level meta-analysis. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 224(3), 216–233. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000255

- Trochim, W. M., & Donnelly, J. P. (2007). The research methods knowledge base (3rd ed.). Atomic Dog Publications.

- Walker, R., & Frazier, A. (1993). The effect of a stress management educational program on the knowledge, attitude, behavior, and stress level of college students. Wellness Perspectives, 10(1), 52–60.

- Weare, K., & Nind, M. (2011). Mental health promotion and problem prevention in schools: What does the evidence say? Health Promotion International, 26(suppl_1), i29–i69. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dar075

- Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 132(2), 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249

- Wright, P. J., & McKinley, C. J. (2010). Mental health resources for LGBT collegians: A content analysis of college counseling center web sites. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(1), 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.533632

- Zivin, K., Eisenberg, D., Gollust, S. E., & Golberstein, E. (2009). Persistence of mental health problems and needs in a college student population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 117(3), 180–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.001