ABSTRACT

Every time a person is booked into police custody in England and Wales, they are assessed for risk of harm to themselves or others. National guidance is provided on what questions should be asked as part of this process; however, each year there are still instances of serious adverse incidents, self-harm and deaths in custody. The purpose of this study is to look at the extent to which the national guidance is being followed and the extent to which the risk assessment process varies between police forces. A Freedom of Information request was sent to all 43 police forces in England and Wales asking for information on their risk assessment process. This data was then analysed alongside findings from police custody inspection visits conducted by Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary. This study provides evidence that the risk assessment process is not consistent across police forces in England and Wales. Not only does the process vary from the national guidance, the content and delivery differs considerably between police forces. The findings highlight a practical problem for police forces in ensuring that risk assessment processes are conducted to a consistent standard and reflect national guidance. The study is, to the authors’ knowledge, the first time that this data has been collated and compared.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

The aim of this study is to investigate variation across police forces in England and Wales within the initial risk assessments carried out when a person is booked into police custody. It is estimated that around a million people are booked and detained in police custody each year (National Preventative Mechanism Citation2016) across the 43 police forces in England and Wales. The arrest and detention of a person is regulated through the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) (UK Parliament Citation1984). The Act provides a legislative framework which governs police powers of investigation covering arrest, detention, interrogation, searches and the taking of samples. The Act is also supported by Codes of Practice which provide a structure to which the police should work. The detention, treatment and questioning of detainees, detained arrested persons, are covered by PACE Code of Practice C (Home Office Citation2017). The document states that a risk assessment should be carried out to ‘consider whether the detainee is likely to present specific risks to custody staff, any individual who may have contact with the detainee (e.g. legal advisers, medical staff) or themselves’ (Home Office Citation2017, 3.6).

The risk assessment of a detainee when they come into custody is essential not only to ensure their safe detention but also to identify any issues, such as learning disabilities, which may affect their rights and welfare. The period of detention is relatively short lasting up to a maximum of 24 hours unless there is special permission to detain the person longer. Deaths in police custody are an exception and have fallen over the last 11 years from 27 in 2006/07 to 14 in 2016/17, as reported by the Independent Police Complaints Commission (Independent Police Complaints Commission Citation2017). However, there are also an unknown number of ‘near-misses’ or ‘adverse incidents’, events which could have led to the serious harm or death of the detainee if intervention had not occurred. Data on near-misses are currently not routinely reported nationally, although a study carried out by the IPCC estimated that there are around 1000 near-miss incidents a year across England and Wales (Bucke et al. Citation2008). This figure may under-estimate the situation though as it is based on retrospectively collated data from forensic medical examiners. A study analysing recorded incidents of self-harm from custody records found that in one force there were 168 recorded incidents out of 48,000 arrests (0.35%) (Cummins Citation2008). Therefore, although incidents of self-harm are not entirely synonymous with near-miss incidents, it does suggest that if there were a million detainees a year, the figure of near-misses would be nearer 3500 than 1000.

In addition to the high volume of detainees passing through custody, detainees often present with complex needs, physical, mental and emotional. A proportion of detainees will also be recognised as vulnerable due to their mental capacity, mental disorder or age and will require an appropriate adult (AA) to be present (Dehaghani and Newman Citation2017). Detainees are not automatically seen by a Healthcare Professional (HCP), however, if they appear physically or mentally unwell, appear in need of medical attention or request a medical examination, the custody officer would request an HCP to provide clinical attention (Home Office Citation2017, 9.5). Dependent on the healthcare model employed by the force, this could be in the form of a forensic medical examiner (FME), forensic nurse or paramedic. The proportion of detainees who are seen by an HCP can vary greatly between forces, and even between different custody suites within the same force (Mitchell et al. Citation2013). Several force-based health needs assessments suggest that this proportion can vary from around a fifth (Brooker et al. Citation2012, Sirdifield and Brooker Citation2012, Brooker et al. Citation2015) to around 40% (Mitchell et al. Citation2013), and one study based in a London custody suite found that nearly a half of detainees saw an HCP (McKinnon and Grubin Citation2010). Again, this may be due to the healthcare model used, as some forces have HCPs based within a custody suite, whereas in others, HCPs are called in when required.

When looking at the complex needs of detainees, Payne-James et al. (Citation2010) found that a significant proportion (56%) of detainees who saw an HCP in police custody had an active medical condition and around 40% were already on prescribed medication. In addition, mental health issues are prevalent among the detainee population, ranging from 24% (Payne-James et al. Citation2010) to 39% (McKinnon and Grubin Citation2013), of those that saw an FME. The study by McKinnon and Grubin also found that just over 1 in 10 detainees seen by an FME had current suicide ideation and that nearly a fifth had previously attempted suicide (McKinnon and Grubin Citation2013). Although there has been a significant reduction in self-induced deaths in police custody over the last 20 years, mental health needs remain a risk factor. In 2015/16 half of the detainees who died in custody had a mental health issue (Angiolini Citation2017). A greater risk of self-harming behaviour and suicide ideation has also been linked to alcohol and drug misuse (Scott et al. Citation2009), (Forrester et al. Citation2016). It is estimated that two thirds of detainees have drug and/or alcohol problems, with over a third of detainees who saw an FME being intoxicated by alcohol (McKinnon and Grubin Citation2010). Individuals dependent on alcohol can also be at risk of alcohol withdrawal syndrome which can be fatal. The prevalence of drug misusers within police custody is difficult to identify as drug use is not always revealed. However, it has been estimated that one in three detainees who see an FME were dependent on heroin and/or crack cocaine (Payne-James et al. Citation2010). In fact, alcohol and/or drug consumption has been highlighted as a significant risk factor for not just self-harming behaviour but also deaths in police custody. A study examining deaths in custody between 1998/99 and 2008/09 found that nearly three quarters of the detainees included in the report had deaths linked to alcohol and/or drugs (Hannan et al. Citation2010). This was in various guises from alcohol poisoning or withdrawal, to the delay in identification and treatment of other health problems due to intoxication, for example, masking the symptoms of head injuries. More recent figures have shown that this proportion has increased, with 82% of detainees who died in police custody between 2004/05 and 2014/15 associated with drugs and/or alcohol (Lindon and Roe Citation2017). This suggests that screening processes such as the risk assessment play an important part in identifying these risks (Lindon and Roe Citation2017). However, it can often be difficult to assess a detainee for risk of harm as police custody is an environment where emotions can not only run high, but are also uncertain and changeable, with complex detainee needs and unknown risks adding to the emotional flux (Wooff and Skinns Citation2017). The recent review into deaths in custody acknowledges also that custody officers often have to assess risk and complex needs under volatile conditions including where the detainee is violent, drunk or under the influence of drugs (Angiolini Citation2017).

The strengthening of the risk assessment process has been cited by the recent independent investigation into deaths in custody as a possible contributor to the reduction deaths over the last 15 years (Angiolini Citation2017). Between 2003 and 2010, there were several key investigations into deaths in police custody (Havis Citation2003, Best Citation2004, Hannan et al. Citation2010) which highlighted key risks to detainees safety. Alongside these reports came the development of useful practical guidance for custody staff. Produced in 2006 and updated in 2012, ‘Safer Detention and Handling of Persons in Police Custody’ (Association of Chief Police Officers Citation2012) was developed to provide national guidance on practical issues within police custody with the aim of raising standards of care. This guidance has since been superseded by the Authorised Professional Practice (APP) guidance which was first published online by the College of Policing in 2013 (College of Policing Citation2017). This format now provides custody staff with easily accessible, practical guidance on police custody procedures which link back to the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (Citation1984) and Code of Practice C. Although the guidance is not mandatory, it is expected that ‘police officers and staff have regard to APP in discharging their responsibilities’ and would need to have a clear rationale for deviating from the guidance (College of Policing Citation2016).

The APP guidance covers most aspects of the risk assessment process, defining it as ‘assessing the risk and potential risk that each detainee presents to themselves, staff and other people coming into the custody suite’ (College of Policing Citation2017). shows the nine questions that are provided for custody officers to ask detainees along with three supplementary questions which should be asked if the detainee answers yes to any of the previous questions.

Table 1. Risk assessment questions from APP guidance (College of Policing Citation2017).

Although these questions provide the framework for a standardised risk assessment, the guidance does acknowledge that no standard risk assessment model exists for the police service (College of Policing Citation2017). This paper does not suggest that the initial risk assessment should be exactly the same for all detainees as a degree of flexibility is required when dealing with individuals. Currently, however, each police force operates independently, potentially leading to unwarranted and unsafe variation in the implementation of detainee risk assessments across the country. The purpose of the study described in this paper is to identify the extent to which the national guidance is followed in respect to the risk assessment of detainees and how the content and delivery varies across the country.

This paper firstly sets out the methodology used in the study followed by analysis of two sets of data. Firstly, reports from custody suite inspections are examined for variance in the delivery of risk assessments. Secondly, information on the risk assessment process itself is analysed for variation in content between forces. The findings are then summarised and discussed further. It should be stressed that this study does not examine the effectiveness of the risk assessment to identify all risks or vulnerabilities, clinical or otherwise. Recent studies investigating this issue have found that generally, the current risk assessments fail to identify a significant proportion of risks (Carter and Mayhew Citation2010, McKinnon and Grubin Citation2013, Noga et al. Citation2015, Williams et al. Citation2017) or identify vulnerable adults (Dehaghani Citation2016a, Citation2016b).

Methodology

The study in this paper examines data from two different sources and uses a mixed methods approach. The first analysis section concentrates on qualitative data taken from reports based on inspection visits. Police custody suites are subject to inspection visits conducted by HM Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) and HM Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP) (Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services Citation2017). Around 8 to 10 forces are investigated each year, usually on an unannounced visit. The inspections cover all areas of police custody ranging from staffing and the quality of estate, to processes such as handovers and provision of mental health and substance misuse services. Since 2014, there has been an additional remit to focus on the welfare of vulnerable people in their inspections with the aim of identifying how effective police services are in identifying and responding to vulnerabilities (Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary Citation2015). In respect to the risk assessment process, the HMIC expectation is that ‘All detainees are held safely and any risk they pose to themselves and/or others is competently assessed and kept under review’ (Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons and Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary Citation2016, p. 14). This includes staff knowing how to assess and respond to risk as well as using all information available to complete the assessment and having knowledge and understanding of risk factors, particularly self-harm, mental health and the influence of drugs and alcohol (Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons and Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary Citation2016).

The analysis of the HMIC reports includes data from 25 unannounced inspection visits carried out between 2014, when the additional remit was included, and 2016, the latest date for reports available at the time of analysis. This does not include the report for the British Transport Police. In this study, the resulting reports have been analysed thematically in relation to comments and findings on how risk assessments were conducted. The thematic headings used in the analysis were derived from common threads running through the inspection reports in relation to the initial risk assessment process, particularly around the quality and manner of delivery.

The second type of data analysed comes directly from the police forces. In England and Wales information from a public sector organisation can be requested under the Freedom of Information Act (UK Parliament Citation2000). In March 2017, a Freedom of Information (FOI) request was sent to each of the 43 police forces in England and Wales, asking for the following information:

What custody IT system do you use?

Please could you provide the risk assessment questions (in order) that a custody officerFootnote1 must ask a detainee on arrival; are these questions adaptive or are they standard questions to all detainees?

Please could you provide the custody officer observations that must be recorded (in order) as part of the risk assessment.

Responses were received between April and September 2017 from all forces, although one force refused to supply the risk assessment questions or custody officer observations and four other forces did not provide custody officer observations recorded.

Quantitative analysis was used to compare the risk assessment questions from the forces to the questions laid out in the APP guidance as shown in . On comparison, it was found that there were various inconsistencies of how the same question was worded as well as additional questions used which were not covered by the guidance. To account for this, each question was grouped into an overarching subject heading. The 12 APP questions given in were translated into 12 subject areas shown in . The 17 additional questions identified and their subject groups are shown in .

Table 2. APP risk assessment checklist questions and related subject.

Table 3. Additional risk assessment questions and related subjects.

The two sets of subjects shown in and were firstly analysed separately, then combined to analyse the order in which subjects were covered. This analysis was based on the information provided from the forces which showed the order in which the risk assessment questions are covered within the custody record management system. While it is acknowledged that in reality, some subjects may be covered in others, for example, a response to a question about medical conditions may divulge a mental health issue, this analysis focused on the order provided by the forces. A weighted mean rank was calculated for each subject to account for frequency of use across the forces. The weighted rank was then used to provide an ordered risk assessment which would demonstrate the generalised position of subjects within risk assessments and their relative importance as deemed by the forces.

A similar process was carried out for observations that custody officers make as part of the process. Although there is no national guidance within APP as to what data should be captured, there were 20 observation subjects that commonly appeared in responses from the forces, as shown in .

Table 4. Custody officer observation examples and subject.

The analysis also considered the IT systems used for the management of electronic custody records. Currently, each force has the authority to procure its own IT system which has led to a variety of custody record systems being used throughout England and Wales as shown in . This can influence the risk assessment process as forces using the same custody record management system may include similar questions. Additionally, forces that use internally developed systems rather than procured ready-made systems have the autonomy to include any risk assessment questions they see appropriate.

Table 5. Custody IT system by number of Police Forces, 2017.

Findings

Police custody inspection reports

Three key themes emerged from the reports when looking at how the risk assessment was delivered. These were: an overview of the quality of risk assessment, the standard of supplementary questions and the manner in which the risk assessment was delivered. These three themes have been used to analyse the standard of risk assessment delivery across England and Wales.

Quality of risk assessment

The main theme of the risk assessment section in the inspection reports was to assess the overall quality of the risk assessment, with an overview of whether the risk assessment was conducted and completed to a satisfactory level. Out of the 25 reports, 7 stated that the risk assessments were either properly or appropriately focused. For example:

Risk assessments were comprehensive, properly focused and enhanced by supplementary questions … Our CRA and observations during the inspection assured us that risk assessments were of a good standard and generally recorded relevant information in sufficient depth. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Custody staff interacted well with detainees when completing risk assessments, and these were generally dynamic, thorough and appropriately focused. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

The practice of undertaking risk assessments was generally much better than records suggested. We observed sergeants generally completing risk assessments which were properly focused on identifying and managing risks … . (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Risk assessments were well conducted and any vulnerabilities or self-harm issues raised by detainees were explored. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Most of the risk assessments we observed, and those we reviewed from custody records, were of high quality, with a good amount of relevant detail. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Risk assessments were good, and in some cases excellent. They were completed thoroughly with custody staff paying particular attention to detainees’ mental and physical health … . (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

We were concerned about the overall approach to risk assessment across the spectrum, from booking into custody, through the continued review and on to the pre-release risk assessment. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Overall risk assessment processes across the custody suites were poor … All detainees were risk assessed, but the risk assessment proforma that custody staff completed was too formulaic. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

We saw staff undertake risk assessment that ranged from very good to some that raised some concerns. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Despite this, initial risk assessments were of varying quality … Some risk assessments were very good and staff explored emerging issues but too many were process driven, and some failed to identify risks and take action to address them. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

These statements suggest that on the whole, risk assessment processes are appropriately focused and thorough across most forces. However, this is not consistent across all forces and in some places concerns were raised about the approach and the process to assessing the risk of the detainee.

Supplementary questions

Although supplementary questions are not an explicit criteria, staff are expected to ‘know how to effectively assess and respond to any risk detainees poses to themselves and/or others’ (Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons and Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary Citation2016). Therefore, in order to effectively assess risk, it would be expected that the custody officer would ask follow-up questions where appropriate. Supplementary questions were referred to in all 25 reports. The majority of these (18) were positive in their statements, for example:

They also asked appropriate supplementary questions and paid particular attention to mental and physical health needs. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

… probing questions were used to elicit information from detainees to inform their care plan. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

All custody sergeants asked appropriate supplementary questions when necessary to explore areas of potential concern. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Custody sergeants took a mainly formulaic approach to risk assessments, asking only basic questions following the prompts … Many sergeants were not sufficiently responsive to non-verbal cues, especially when detainees disclosed sensitive information. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

There was little exploration of potential concerns about health and self-harm, and some assessments were rushed. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

We observed custody staff rushing through the questions about health and self-harm without exploring concerns fully. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Custody sergeants sometimes asked useful supplementary questions when assessing detainee risk … (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Most asked supplementary questions when assessing risk … (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Overall, the majority of reports indicate that most custody officers ask supplementary questions, or try to elicit further information, to inform the risk assessment. However, this is not consistently delivered across the forces, and in some cases, within the force itself. Where risks have been identified through the standard questions, often supplementary information is needed to understand the risk further. Without the supplementary information, the risk may not be understood and therefore may not be managed appropriately.

Manner of delivery

The manner in which the risk assessment is delivered can impact the quality of answers from the detainee and it is expected that ‘Police officers and staff engage positively with detainees during their detention, particularly those who are vulnerable and high risk’ (Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons and Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary Citation2016, p. 12). The manner in how the risk assessment was delivered was mentioned in 18 of the 25 reports. Of these, 13 reports had generally positive statements about how custody officers interacted with detainees and delivered the risk assessment. For example:

Responses to demanding behaviour were not over-reactive or heavy handed and we saw officers dealing patiently with difficult situations in a calm and measured way. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Custody staff interacted very well with detainees to complete risk assessments … We saw many examples where custody staff dealt patiently and sensitively with detainees, particularly those who were intoxicated and/or vulnerable. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

The custody records and our observations highlighted some impressive interactions with detainees when completing these assessments … (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Although there were a few notable and commendable exceptions, custody sergeants took a mainly formulaic approach to risk assessments … They did not explain to detainees that the questions were part of a risk assessment or ensure that they were well cared for. Staff did not attempt to establish a rapport with the detainee. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

However, this was an exception and many risk assessments were completed in a mechanistic manner. There was little exploration of potential concerns about health and self-harm, and some assessments were rushed. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Most … were friendly and empathetic with detainees. However, a few approached the risk assessment process in a more mechanistic manner and failed to explain to detainees the meaning and significance of phrases such as ‘mental health’. (HMICFRS Citation2014–2016)

Summary

The combined impression from the analysis of the three themes is that, in general, risk assessments in police custody are appropriately focused, asking probing supplementary questions where appropriate and are delivered in a positive way with good interaction between the custody staff and the detainee. However, it can also be seen that there is variation between the forces as to how well this is accomplished, and also in fact, variation within the force. This suggests that the delivery of risk assessments across police custody suites within England and Wales is not conducted to a standard level.

The risk assessment process across the forces

This section analyses the data received from the FOI request to investigate variation in content across the forces. Firstly, the data is examined to establish if the risk assessment questions are adaptive or standard. Secondly, the risk assessment questions themselves are analysed and then finally the custody officer observations.

Standard or adaptive risk assessment questions

To help understand if the risk assessment questions are asked of every detainee, police forces were asked if the questions were adaptive or standard. All 43 forces stated that the questions were standard. However, some forces expanded on this answer to suggest that although the questions are standard to all detainees, custody officers have the freedom to ask any additional questions that they feel are appropriate, as demonstrated by the following examples:

These are standard questions that are asked to every detainee but the custody Sergeants are encouraged to push for more information if they feel it is necessary.

The template provides space for responses which allows the individual case-by-case nature of the issued to be recorded. It there is a particular risk that is obvious to a Custody Officer which is not provided for and not captured above, they have the ability to record the information in the free text detention log.

The initial questions are standard and then depending on the answers provided, further exploration will take place.

Risk assessment questions

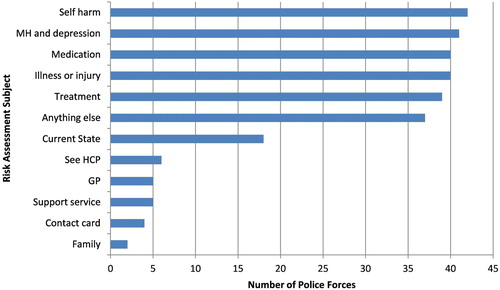

Each force was asked to list the risk assessment questions that custody officers must ask a detainee on booking into custody. These were then compared to the 12 subjects covered by the APP detention and custody guidance as shown in . Out of the 42 police forces providing this information, Self-harm was the only subject to be covered by all of them. Overall, six of the subjects in the APP guidance were covered by over 90% of the forces. However, the five least common APP subjects were only covered by fewer than 15% of forces. This can be seen in where See HCP, GP, Support service, Contact Card and Family are covered by six or fewer forces. This does not necessarily mean that these subjects are not covered at all by the other forces, just that they are not part of the standard risk assessment for that force. Across all forces, the most common number of APP subjects covered was six and the lowest was four, out of a possible 12.

Only one force covered all of the recommended subjects within their standard risk assessment. shows the number of IT systems that covered each APP subject. The table shows that there was a core set of six APP subjects covered by forces that used NICHE; however, there were a couple of NICHE forces that covered more subjects, including the force that covered them all. The next most frequently used system, NSPIS, had all of their forces cover the same seven of the subjects.

Table 6. Crosstab of APP risk assessment questions covered by custody record management system.

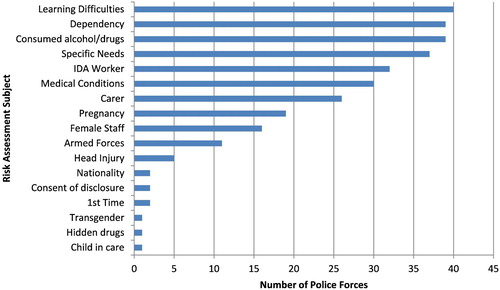

In addition to the APP subjects, there were 17 additional subjects covered by the forces as shown in . The highest number of additional subjects covered by a force was 11 and the lowest was 2. Although this did not appear to be linked to the IT system, forces with an internally developed system generally covered more additional subjects, with a mode average of 9 compared to a mode average of 5 for procured systems. Overall, the most commonly covered additional subjects concerned: Learning difficulties; Consumption of alcohol/drugs; Dependency and Specific needs (). Five forces specifically ask about head injuries, a risk factor that can be mistaken for intoxication.

Combining the subjects in and produces 29 different subjects identified from the information submitted by police forces. shows the 29 subjects in order of frequency covered, with the most commonly covered subject first. Overall, the top 10 subjects were covered by nearly 90% of forces and 6 of these subjects were from the APP checklist, as shown by the * in the table. However, there are also five APP subjects in the bottom half of the table as they were only covered by fewer than 15% of forces.

Table 7. Identified risk assessment subjects in order of frequency (* denotes the subject is from the APP guidance).

Interestingly, the number of subjects covered by the different IT software systems varies. The number of subjects covered ranges from 8 to 23, with most forces either covering 11 or 16 subjects in the risk assessment. However, all but one of the forces that cover 11 subjects uses NICHE, whereas all but one of the NSPIS forces covers 16 subjects.

As a way to demonstrate the perceived importance of the subjects by the forces, the subjects were ranked according to the order they appeared in the risk assessment, starting at 1 for the first subject covered. Some subjects, such as Treatment or Medication, appeared several times in the risk assessment questions. Therefore, the ranking of these subjects is based only on the first time the subject appears.

The mean rank of a subject has then been calculated by dividing the sum of ranks by the number of forces covering the subject. This was then used to calculate a weighted rank which account for the frequency of occurrence across the different forces. For example, 19 out of 42 forces (45.2%) covered the subject of pregnancy, and it had a mean ranking position of 7.9. Therefore, the weighted rank would be 7.9/0.452 = 17.5. The order of risk assessment subjects by weighted rank is shown in .

Table 8. Ranking order of risk assessment subjects by weighted mean rank.

The findings from the analysis of the risk assessment question shows that the ‘standard’ checklist of questions provided in APP is not standardly used by police forces across England and Wales. In fact, police forces commonly include additional subjects covering questions on drug/alcohol use, medical conditions and learning difficulties, suggesting that these are important factors which should actually be included in the guidance. There is also a variance in the order that the subjects are covered within the risk assessment. Overall, this demonstrates a variance away from the national guidance and also between forces.

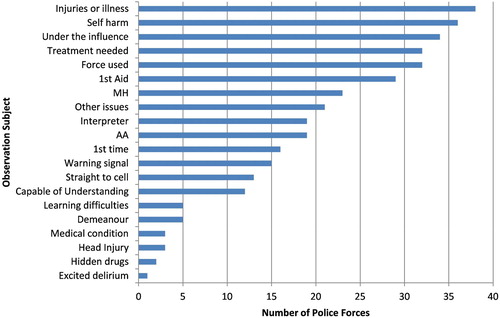

Risk assessment custody officer observations

In addition to self-assessment questions, many forces also require custody officers to record their observations of the detainee as part of the risk assessment process. Custody officer observations are not specifically mentioned in the APP guidance; however, the guidance refers to the PACE Code of Practice C which states that ‘proper and effective’ risk assessments should be implemented (Home Office Citation2017). The APP guidance also states that the risk assessment should be guided by the National Decision Model which requires decision makers to record reasons for their decisions (College of Policing Citation2017). Although there were 5 police forces that did not provide any information, some form of observation recording appeared to be standard within the 38 police forces that provided this information.

As there is no checklist to suggest what observations should be recorded, there is the potential of content to vary between forces. Overall, there were 20 observation subjects, as shown in , some of which covered similar topics to the risk assessment questions, for example, self-harm and medical condition.

shows the observation subjects covered by the number of forces. The average number of subjects that a police force requests a custody officer to record is nine, and nearly two thirds of forces cover between 9 and 10 subjects. The most number of subjects covered by a force was 13 and the least was 4. The number of subjects covered does appear to be slightly linked to the IT system. For example, the majority of forces that use NICHE covered between 9 and 11 subjects, and over 80% of forces using Capita systems covered nine subjects. The most common observation subjects concern: Injuries or illness (38); Self-harm (36); Under the influence (34); Treatment needed (32); and Force used (32). It is interesting to note that only two forces had asked detainees if it was their first time in custody; however, 16 forces record it as part of their observations.

There are a small number of forces that ask for observations specific to risks of death in custody. For example, three forces ask for observations about head injuries, two forces cover hidden drugs and one force asks for observations about excited delirium. On investigation, these forces have all previously had incidents or deaths in custody due to these factors.

Using the same methodology and calculations used in , the custody observation data has also been ranked according to a weighted mean where N = 38. This is shown in .

Table 9. Ranking order of custody officer observations by weighted rank.

Although not specified in the guidance, there appears to be a common set of observations recorded by police forces. In particular, the five subjects of Self-harm, Injuries and illness, Under the influence, Treatment need and Force used are recorded by the vast majority of police forces. These are all factors that contribute to the risk of harm. In addition, the recording of whether an AA or interpreter is needed or if the detainee is capable of understanding are key to identifying vulnerable detainees. Additional observations recorded vary amongst forces and may be dependent on IT software or historical incidents, highlighting variance between the forces.

Discussion

It is perhaps not unexpected that the HMIC investigation reports showed variation in how the initial risk assessment process was delivered across the forces in England and Wales. Delivery of the detainee risk assessment by a custody officer is heavily dependent on human factors such as personality, experience of issues covered and experience in the role. What could be seen as unexpected is the amount of variation in the content of risk assessments, particularly as a national checklist of questions is available. Although some variance would be expected and a degree of flexibility is needed within the process to adapt to individual situations as appropriate, it is also reasonable to assume that the core content would be the same across all police forces. The lack of consistency in which risk factors and issues are addressed may lead to important and relevant information being missed. This coupled with the variance in how the initial risk assessment is delivered would have a negative impact on the process as a whole. It could be argued that the core set of questions and observations that address the highest risk factors and vulnerabilities should be the same no matter which custody suite a detainee is booked in at. However, this would need to be balanced with an adaptive approach to the individual so that the process is not merely a ‘tick-box’ exercise which is mechanistic and formulaic, potentially discouraging detainees from revealing important information. It is also interesting to note that although there are only a few commercially produced custody record management systems used by the majority of forces, the systems do not incorporate all of the national guidance questions and there can also be differences in content within the same software depending on the version used. Conversely, it is interesting that some main risk factors are not incorporated into the national guidance. For example, intoxication or withdrawal from alcohol has been shown to be a major factor previously in deaths in custody (Best Citation2004, Hannan et al. Citation2010); yet it is not included in the APP standard risk assessment questions. Similarly, asking about learning difficulties or observing a detainees capability of understanding helps to identify vulnerable detainees in need of an appropriate adult, however, these are not part of the APP questions either. Perhaps these oversights in the national guidance has reduced the perceived integrity of the recommended checklist and led to some forces including questions they feel are more relevant and which will enable their custody officers to assess risk and vulnerability more accurately. In addition, there are a few forces where a previous incident has led to the incorporation of targeted questions, for example, about hidden drugs or excited delirium. It could be argued that these questions which have arisen due to lessons learnt should, maybe, be expanded and incorporated into all forces risk assessments. This also touches upon the issue of the 43 forces operating independently to each other, therefore, leading to a natural variation in the process. There is currently a drive through the National Custody Strategy to bring all forces together and to follow best practice. However, as with the current guidance, this would not be mandatory. It is hoped that this current study of what content police forces include in their initial risk assessments will be helpful in developing any future guidelines.

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, the inspection reports considered only looked at the processes within custody suites over a two-year span from 2014 to 2016. It would be hoped that any improvements suggested by the HMIC have been made in those forces since then. Secondly, the information requested from police forces on questions asked and observations recorded has been provided directly from the custody record management systems and does not show what happens in practice. For example, supplementary questions could be asked in addition to the standard questions and therefore the risk assessment could cover more subjects than reported. Conversely, some questions in the standard risk assessment may be, in practice, overlooked if not deemed relevant. This study has not attempted to analyse to what extent custody officers follow the forces process. The initial risk assessment has also been looked at in isolation to the rest of the booking in process and it may be that some questions are asked at a different point of the process. It is also worth noting that risk assessment within police custody is a dynamic process carried out throughout the detainees stay. The observation level set as a result of the initial risk assessment can be changed at any time, depending on changing factors such as behaviour or health.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper has shown that there is a wide scope for further research around the detainee risk assessment process and the degree of standardisation required to ensure that police forces across England and Wales not only deliver to a consistent standard but also collect information on key issues in order to determine risk and vulnerability. This initial look at variation within the detainee risk assessment process has demonstrated that, in general, police forces do not consistently follow national guidance in terms of questions asked of detainees. However, it may be that some of the lesser covered questions, such as if the detainee wants to see a healthcare professional, are asked as a follow-up question as both the analysis of HMIC reports and FOI data showed that most custody officers ask supplementary questions. The findings also highlight that the national guidance questions do not cover some of the high risk issues such as drugs and alcohol, leaving police forces to include these important factors themselves. Both the inspection reports and the analysis into risk assessment content demonstrate that there is a large variance in both the delivery and content of risk assessments by police forces across England and Wales, more than that might be expected given the APP guidance. However, the evidence also shows that police forces generally collect more information around the risk and vulnerability of the detainee than the guidance recommends. This is particularly evident with risk factors, such as alcohol use and medical conditions, which are not included in the guidance questions. These findings suggest that the APP guidance may need revising, not only to include the questions that police forces deem important, but to also target previously identified risk factors that contribute to the harm or death of detainees.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Melanie-Jane Stoneman http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7492-3316

Lisa Jackson http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7463-2989

Sarah Dunnett http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6357-4376

Louise Cooke http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6155-4339

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In practice, custody officers are often referred to as custody sergeants, however, as the term ‘custody officer’ is used within the Police and Criminial Evidence Act (Citation1984) and all relevant guidance is used within this study.

References

- Angiolini, E., 2017. Report of the independent review of deaths and serious incidents in police custody. London: Home Office.

- Association of Chief Police Officers, 2012. Guidance on the safer detention and handling of persons in police custody. London: National Policing Improvement Agency.

- Best, D., 2004. The role of alcohol in police-related deaths: analysis of deaths in custody (category 3) between 2000 and 2001. London: Police Complaints Authority.

- Brooker, C., et al., 2012. Northumbria police custody health needs assessment. United Kingdom: Improving Health & Wellbeing U.K.

- Brooker, C., et al., 2015. Police custody in the north of England: findings from a health needs assessment in Durham and Darlington. Journal of forensic and legal medicine, 1–5.

- Bucke, T., et al., 2008. Near misses in police custody: A collaborative study with forensic medical examiners in London. London: Independent Police Complaints Commission.

- Carter, J., and Mayhew, J., 2010. Audit of hospital transfers January to March 2006 from Sussex police custody. Journal of forensic and legal medicine, 17, 38–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2009.07.014

- College of Policing, 2016. About us [online]. College of Policing. Available from: https://www.app.college.police.uk/about-app/ [Accessed 30 Nov 2017].

- College of Policing, 2017. Detention and Custody Authorised Professional Practice [online]. College of Policing. Available from: http://www.app.college.police.uk/app-content/detention-and-custody-2/ [Accessed 30 Nov 2017].

- Cummins, I., 2008. A place of safety? self-harming behaviour in police custody. The journal of adult protection, 10, 36–47. doi: 10.1108/14668203200800006

- Dehaghani, R., 2016a. Custody officers, code C and constructing vulnerability: implications for policy and practice. Policing: A journal of policy and practice, 11, 74–86.

- Dehaghani, R., 2016b. He's just not that vulnerable: exploring the implementation of the appropriate adult safeguard in police custody. The howard journal of crime and justice, 55, 396–413. doi: 10.1111/hojo.12178

- Dehaghani, R. and Newman, D., 2017. “We’re vulnerable too”: an (alternative) analysis of vulnerability within English criminal legal aid and police custody. Oñati socio-legal series, 7 (6), 1199–1228.

- Forrester, A., et al., 2016. Suicide ideation amongst people referred for mental health assessment in police custody. Journal of criminal psychology, 6, 146–156. doi: 10.1108/JCP-04-2016-0016

- Hannan, M., et al., 2010. Deaths in or following police custody: An examination of the cases 1998/99 - 2008/09. Available from: https://www.ipcc.gov.uk/page/deaths-custody-study: Independent Police Complaints Commission.

- Havis, S., 2003. Drug-related deaths in police custody: a police complaints authority study. London: Police Complaints Authority.

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, 2015. The welfare of vulnerable people in police custody. London: HMIC.

- Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services. 2017. Police Custody Joint Inspection Report Publications [online]. HMICFRS. Available from: http://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/?s=&cat = custody-suites-cat&force=&year=&type = publications [Accessed 2 Dec 2017].

- Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons and Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary, 2016. Expectations for police custody; criteria for assessing the treatment of and conditions for detainees in police custody. London: HMIP and HMIC.

- HMICFRS. 2014–2016. Police Custody Facilities - Joint Inspections Force Reports [online]. Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services. Available from: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/our-work/article/criminal-justice-joint-inspection/joint-inspection-of-police-custody-facilities/ [Accessed 2 Dec 2017].

- Home Office, 2017. Code C revised: code of practice for the detention, treatment and questioning of persons by police officers: police and criminal evidence act 1984 (PACE). London: The Stationery Office.

- Independent Police Complaints Commission, 2017. Deaths during or following police contact: statistics for England and Wales 2016/17. London: Independent Police Complaints Commission.

- Lindon, G. and Roe, S., 2017. Deaths in police custody: A review of the international evidence. London: Home Office.

- Mckinnon, I., and Grubin, D., 2010. Health screening in police custody. Journal of forensic and legal medicine, 17, 209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2010.02.004

- Mckinnon, I., and Grubin, D., 2013. Health screening of people in police custody – evaluation of current police screening procedures in London, UK. The european journal of public health, 23, 399–405. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks027

- Mitchell, D., et al., 2013. Warwickshire and West Mercia police custody health needs assessments. United Kingdom: Improving Health & Wellbeing U.K.

- National Preventative Mechanism. 2016. Detention population data mapping project [online]. National Preventative Mechanism. Available from: http://www.nationalpreventivemechanism.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/NPM-Detention-Population-Data-Mapping-Project-FINAL.pdf [Accessed 20 Mar 2017].

- Noga, H.L., et al., 2015. The development of a mental health screening tool and referral pathway for police custody. The european journal of public health, 25, 237–242. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku160

- Payne-James, J., et al., 2010. Healthcare issues of detainees in police custody in London, UK. Journal of forensic and legal medicine, 17, 11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2007.10.011

- Scott, D., Mcgilloway, S., and Donnelly, M., 2009. The mental health needs of women detained in police custody. Journal of mental health, 18, 144–151. doi: 10.1080/09638230701879193

- Sirdifield, C., and Brooker, C., 2012. Detainees in police custody: results of a health needs assessment in Northumbria, England. International journal of prisoner health, 8, 60–67. doi: 10.1108/17449201211277183

- UK Parliament, 1984. Police and criminal evidence Act 1984. London: The Stationery Office.

- UK Parliament, 2000. Freedom of information Act 2000. London: The Stationery Office.

- Williams, E., Norman, J., and Sondhi, A., 2017. Understanding risks: practitioner’s perceptions of the lottery of mental healthcare available for detainees in custody. Policing A journal of policy and practice, pax067, 1–14.

- Wooff, A. and Skinns, L., 2017. The role of emotion, space and place in police custody in England: towards a geography of police custody. Punishment & society, 1–18.