ABSTRACT

As societies are becoming more heterogeneous and complex, the role of the police is becoming more demanding. To fulfil this role, police officers need several widely recognised skills and personal qualities, but less is known about how they are valued by police recruits. Thus, we have examined views of police recruits in six European countries on three competencies or characteristics of known importance for police work: knowledge, leadership, and the ability to form good relations with citizens. We have also explored variations in views of recruits in different organisations and changes in their views during their training. For these purposes, we used survey data collected in the RECPOL project. Since the data were collected from different populations and at different times, the analysis is based on measurement invariance methodology, and one of the aims was to highlight the importance of rigorous appraisal of the quality and comparability of similar survey data using such methods. The results reveal both differences and similarities in views of recruits in the surveyed countries and changes during training. Police culture appears to be a significant factor, as more items in the applied instrument could be validly used in comparisons of recruits in organisations with similar police traditions. The results also showed interesting contrasts, e.g. new recruits in Sweden rated good relations with citizens more highly than recruits in organisations with a more military history, but this pattern changed during training, presumably due to influences of the recruitment process, training and culture within the organisations.

Introduction

Policing has changed considerably over time, and become an increasingly multifaceted profession, where typical roles and tasks can vary strongly depending on numerous contextual factors (Frydl and Skogan Citation2004, Inzunza, Citation2016). This is partly because societies are becoming increasingly heterogeneous, and there are tensions between various groups of people. Further identified problems include frequent lack of authority and distrust, emergence of new types of crime, and unfamiliar situations (Rosenbaum and Lawrence Citation2017). These problems have been highlighted in frequent reports in the media of misunderstandings, police officers acting improperly, and/or being pressured, abused or threatened by citizens (Frydl and Skogan Citation2004, Korsell et al. Citation2007). Thus, there are clear needs to review, rigorously and continuously, the primary roles of the police, the key characteristics of police officers, and how these characteristics are valued and developed during police training.

In most democratic western societies, the police are expected to maintain order by consent, as discussed by Jones et al. (Citation1996). However, there are contextual variations in this. Notably, police organisations with a history rooted in colonial systems, and some in Europe associated with the more authoritarian ‘continental’ policing tradition, may depend on other actors for their legitimacy (Cole Citation1999, McGloin Citation2003). There are also probably numerous variations between and within organisations linked to diverse practical and cultural factors. Thus, factors affecting decisions to enter the police profession will also vary, and recruits may have varying awareness of what is expected from them. Their views may be influenced, inter alia, by views expressed by peers and other people around them, media reports, portrayals of police work in documentary and fictional films and literature, and increasingly diverse forms of social media. Thus, they may have substantially varying perceptions of the police profession and ideal personal characteristics of a police officer. Nevertheless, students must be prepared, as far as possible, for the diverse demands and challenges they will encounter in their future profession (Ponsaers Citation2001).

For obvious reasons, important aspects for successful policing have been intensively investigated, but often from either an organisational or societal perspective (Frydl and Skogan Citation2004). Views of recruits have been rarely addressed, and generally in studies limited to one country or organisation (Alain and Baril Citation2005, Meadows Citation1985, Phillips Citation2015, Van Maanen Citation1975). For instance, although it has been established that communication skills and empathy are highly important for police officers, it is not clear if this is known or accepted by people who aim to become police officers. Few studies have addressed police recruits’ perceptions of and attitudes regarding important characteristics for successful policing, particularly in multiple countries and organisations. Thus, there is little knowledge of the variations involved, despite the importance of such knowledge for informing potential applicants, planning police training, and guiding reforms (Bayley Citation1999).

Furthermore, despite vast literature on the police profession, and numerous investigations of policing at local, national and international levels, few studies have adopted a rigorous methodological comparative approach. This is partly due to financial, linguistic and cultural barriers, but also practical issues such as access to equivalent instruments for comparisons. However, there are also substantial practical issues, particularly regarding the instruments used for comparisons. As noted by De Maillard and Roché (Citation2018), robust comparative approaches are essential for clearly identifying differences between organisations, and increasing understanding of relations between police, states and societies. They also stress the importance of going beyond simple, but frequently used typologies of policing systems, such as the Anglo-Saxon and Continental. They convincingly argue that traditional models of police systems are too limited and should include features such as organisational traits, priorities, collaborations, and legitimacy.

Purpose and structure of the study

To address some of the problems outlined above, the purpose of this study was to gauge views of recruits in selected police organisations in Europe regarding three personal qualities of known importance in policing: the ability to form good relations with citizens (empathetic communication), knowledge to guide decisions, and leadership. In addition to exploring between-country and -organisation similarities and differences in views, we aimed to examine possible changes in views between the time recruits had just started training and close to the end of their education, when they had spent time in police training and professional practice.

For this purpose, we used survey data from six countries: Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Scotland, Belgium and Spain. These countries were selected for convenience, based on availability of data that met validity criteria described below. However, they covered sufficient diversity in geographical and cultural conditions, as well as in organisation of police work and training (as also described below), to offer potentially illuminating contrasts. This was also important for a further aim of the study to highlight the importance of rigorous appraisal of the quality and comparability of survey data and present a systematic process for such appraisal.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The three focal aspects (important personal qualities of police officers) are described and previous research supporting their importance is presented in the next section. Then background information regarding the participating organisations is presented, to outline some of the cultural and practical factors that potentially influence recruits in the participating countries. After this, the instrument used in the study and acquired data are described. Then, the methodology, modelling and evaluation of a constructed model are described, and results of the analyses are presented. In the final section of the paper, the study and findings are discussed, and some conclusions and suggestions for future research are made.

Focal aspects and characteristics of the organisations

As discussed above, a number of personal qualities have recognised importance for police officers. Clearly, it is essential to have the skills and knowledge of practical and theoretical matters required for professional work (Kakar Citation1998, Roberg and Bonn Citation2004, Paterson Citation2011). However, some things can be taught, while other important qualities are to varying degrees inherent traits, so police applicants are selected on the basis of not only prior knowledge and formal merits, but also personal characteristics. Since police work involves numerous personal encounters with people in various kinds of distress and often highly charged, stressful or dangerous situations, it is important for officers to have the abilities to understand, cope, and communicate effectively in such situations. For example, police officers must have capacities for various kinds of interaction with citizens, including people who have committed, witnessed, or are victims of crime (Bakker and Heuven Citation2006). Teaching recruits about the law and rights that apply in police officers’ work, and some associated skills, is relatively straightforward. However, the personal qualities required to handle personal interactions competently can only be developed to a limited degree through experience and training, so innate qualities are crucial elements. This poses challenges in both selection and training of recruits, partly because personal qualities are difficult to define and measure, and partly because the willingness and ability to change are influenced by diverse individual and contextual factors. For instance, research by Lord and Friday (Citation2008) has shown that college-educated officers tend to be more flexible and possess more effective communication skills, in comparison to officers without college degrees. Constructs associated with communication skills, such as perspective taking, are relevant in this context. Perspective taking is however a complex construct that can be problematic when individuals believe that they see reality more objectively than others, referred to as naïve realism (Roan et al. Citation2009).

Moreover, the importance of specific qualities is likely to depend on the tasks officers are assigned, and differ between police training and police work. For example, in research on the ‘Big Five’ personality dimensions Black (Citation2000) found that agreeableness is an important factor in police performance, but not necessarily in police training. Education level may also be important, but there are highly conflicting indications of the correlations between years in education and officers’ use of force (Rydberg and Terrill Citation2010). The variation in results corroborates the practical difficulties in measuring police officers’ performance and the wide range of qualities required for different kinds of law enforcement (Sanders Citation2003).

To probe these issues, we selected three personal qualities or ‘aspects’ that appear to be highly important and can be measured with available survey data. As already mentioned, these are the ability to form good relations with citizens (empathetic communication), knowledge to guide decisions, and leadership. For convenience, these are called Good relationships (Towards citizens), Knowledge and Leadership, hereafter. We define and describe each of these aspects in more detail below.

Good relationships

The first aspect is the ability to form good relationships with citizens, which as previously mentioned is crucial for policing in democratic societies, where the power of the police should lie in the common consent of the public, rather than power of the state. It is also crucial for successful ‘community policing’, i.e. strategies rooted in establishment and maintenance of good relations between the police and citizens (Frydl and Skogan Citation2004, Brogden Citation1999). A key characteristic in this context is empathy, i.e. the ability to connect emotionally, within appropriate constraints, to other people (Inzunza Citation2015a). It is seen as a key component for human interaction, especially communication, and lack of empathy frequently leads to misunderstandings, or locked positions, which have severely adverse consequences (Davis Citation1996).

The ability to understand other peoples’ perspectives is especially important in situations where police officers are interacting with victims of crime (Maddox et al. Citation2011). However, it is also important when interrogating suspects, as it allows officers to understand other people’s motives and behaviour (Holmberg and Christianson Citation2002). This is important for successful communication and anticipation of people’s responses in situations they encounter. However, the ability to understand perspectives is not a fixed property and varies with social context. Perspective-taking is especially difficult when interacting with people who differ socially and people perceived as being unfair or dishonest, as many suspects and/or victims may be (Singer et al. Citation2006). This is particularly relevant in modern, increasingly heterogeneous societies, where there often are tensions between groups.

Knowledge and leadership

The two other aspects addressed in our study are knowledge and leadership. Knowledge is clearly crucial for police officers (for example, there are obvious requirements for knowledge of the law, rights and procedures), and assumed to be closely related to their ability to make correct practical decisions. Knowledge is a broad concept, but generally associated with theoretical knowledge and the correlation (if any) between higher education and performance as an officer has been debated (Kakar Citation1998, Roberg and Bonn Citation2004, Paterson Citation2011). Interestingly, it has proved difficult to determine if theoretical knowledge or the conditions associated with attaining more knowledge is most important. Paterson (Citation2011) notes that experience of higher education is associated with more frequent exposure to people with different ethnic backgrounds, which is important for developing a more flexible value system and more positive attitudes towards other ethnic groups. However, education levels may also be correlated with rates of officers changing career and leaving the profession when confronted with the demanding routines of a police officer (Kakar Citation1998). For those who stay in the profession, more theoretical knowledge (often attained in higher education) is associated with higher performance in the academy and higher evaluations as police officers (Henson et al. Citation2010, Smith and Aamodt Citation1997). There are some indications in the cited studies that theoretical knowledge may be regarded as more valuable in police training than it is in most practical police work. However, knowledge is clearly associated with decision-making ability, which is important for leadership. The latter is crucial in police work, as officers frequently have to persuade people in distressed states and difficult situations to comply with their wishes (Schafer Citation2009). Thus, in our modelling we treat knowledge as theoretical understanding that is correlated with educational level and linked through its impact on decision-making ability to leadership, which is a crucial quality in working contexts (Eraut Citation2004).

Consequently, in our model of recruits’ views of important aspects in police work we included good relations (towards citizens), knowledge and leadership, as conceptualised in this and the preceding section.

National contexts of the participating organisations

Swedish, Norwegian and Danish police have several common features. They all have roots in the Scandinavian welfare regime model, which is characterised by the state playing a major role, a comprehensive and well-funded welfare system for all citizens and high economic productivity (Høigård Citation2011). Countries adopting such a welfare model are often highly ranked in terms of socio-economic indicators such as income equality, life expectancy, and trust. Høigård (Citation2011) describes some of the ideals for a police organisation in a Scandinavian welfare state. These include high recognition of the importance of democratic and humanistic values, high local integration of the police in the society they serve (to maximise understanding of the problems they address) and a civilian rather than military orientation, focusing not only on criminal control but also service and assistance. Another typical feature is a generalist approach in terms of competence. Each police officer is expected to have all-round competence, with a single organisation covering all duties and jurisdictions.

However, there has been a recent trend to reduce numbers of police districts and establish a more centralised command structure (Holmberg Citation2014), and some general weakening of the welfare model, especially in Sweden. This has affected the police culture and promoted a more ‘tough on crime approach’ (Høigård Citation2011). According to Eurostat statistics published in 2013, per 100,000 habitants there were 217 police officers in Sweden and 196 in Denmark in 2011 (Aebi et al. Citation2014), and about 159 in Norway in 2010 (Clarke Citation2013), with no major changes according to more recent statistics from 2014/2015. The police education and training is also generally similar in the Scandinavian countries, in terms of length and content. However, in Norway police training has academic status, and students are eligible for academic degrees, such as bachelor’s degrees. In Sweden and Denmark it is not formally academic education, although preparations have been made to give it academic status by incorporating the police academies in higher education institutions. The length of the education is two and a half years in Sweden, and three years in Norway and Denmark.

In Scotland there has been a shift, implemented in 2013, from a tradition of autonomous regional police organisations to a national police force. This was expected, among other things, to provide higher efficiency and financial savings, but there were concerns, particularly that closeness to local communities and citizens would be impaired (Terpstra and Fyfe Citation2015). The cited authors argue that the Scottish police act emphasises the importance of localism, stating that the purpose of policing is to improve the safety and well-being of persons, localities and communities, collaborate with other local agencies and minimise harm while preventing crime. They also argue that the centralisation has weakened local work in practice, and led to higher prioritisation of enforcement activities than community relations. The ratio of police officers is considerably higher in Scotland than in the Scandinavian countries, with 329 officers per 100,000 habitants in 2011 (Aebi et al. Citation2014), and no major changes have been subsequently reported. The education and training also differ, being somewhat shorter, 2 years, and with less theoretical content. The training is divided into four modules, one of which focuses on academic skills and lasts 11 weeks at the Police Scotland College. The other modules are more fragmented and include shorter courses throughout the two-year training period (http://www.scotland.police.uk).

In Belgium, the structural organisation of the police is complex, there have been numerous reforms, and tensions between police cultures. There were three police forces before 1994, and they did not work well together, according to Devroe and Ponsaers (Citation2013). One was the municipal police, financed by individual municipalities and authorised to undertake both administrative and judicial tasks in them. Another was the gendarmerie, which had a military origin, training focused on maintenance of order, and the most authority. The third was the judicial police, engaged in judicial matters concerning ‘white-collar crime’, and the force with shortest history. The relationships between these forces was marred by a lack of clear borders of jurisdiction.

Reforms in 1994 were intended to improve their cooperation and coordination. A system called inter-municipal cooperation was introduced to evaluate the possibilities for the forces to cooperate and offer comprehensive community policing. If successful, they would receive additional federal funds (Devroe and Ponsaers Citation2013). After several events heightened distrust in the police, another attempt to re-organise the Belgian police was made, by creating an integrated police force with federal and local level organisation, the latter guided by a community policing vision. This system has been described as one of the most locally-based systems in Europe (Devroe and Ponsaers Citation2013). The number of police officers relative to the population is in line with Scotland: about 340 officers per 100,000 habitants in 2011 (Aebi et al. Citation2014), with no major differences reported in 2014/2015 (Eurostat). The training to become a police officer in Belgium is considerably shorter than in the Scandinavian countries and Scotland. It takes about a year, at one of several police academies throughout the country. The education and training begins with 8 months of theoretical courses and ends with field training with one of the local police forces (De Schrijver and Maesschalck Citation2015). After graduation the recruits need 6 months of work experience before becoming a sworn police officer.

In Spain, the police has also had an interesting history, with a number of forces organised at multiple (national, regional and local) levels, internal tensions and various cultures. However, in this study the focus is on Catalonia, where there is a municipal force at the local level, and a regional force, Policia de la generalitat Mossos d'Esquadra, which in most areas in Catalonia replaced the Spanish national police force and the civil guard during the years 1994–2008 (Blanco Citation2014). Mossos d'Esquadra is an armed force of a civil nature that has a dominant position and a large degree of autonomy in the Catalan region (Recasens and Ponsaers Citation2014). The basic rationale of establishing a regional police force was to provide the Catalonian citizens with police from the same culture, and this idea is also embedded in the requirements for becoming a police officer. For instance, one of the explicit requirements for a police officer is to read and write Catalán (in addition to Spanish) and an implicit requirement is to have a feeling of belonging to the local area (Inzunza Citation2016). The description of the mission includes both to maintain public order and to protect the freedom and safety of the citizens according to the law (van Ewijk Citation2014). The number of police officers relative to the population is considerably higher in Spain than in the other countries included in this study: 536 per 100,000 habitants in 2011 (Aebi et al. Citation2014), although somewhat lower in Catalonia, at 450 (including all levels) per 100,000 inhabitants in 2012 (Prieto Citation2015). Education and training to become a police officer in Catalonia includes theoretical and practical courses and takes about a year at the academy (ISPC) followed by a year of field training at a local police station. Since 2014 there have been opportunities to advance in the police education to attain a university-level bachelor’s or master’s degree (http://ispc.gencat.cat).

Data

The data used in this study were collected in the ‘Recruitment, Education and Careers in the Police: A European Longitudinal Study’ (RECPOL) project, a longitudinal project that several European police organisations participated in. Data were collected from recruits who started training in these organisations in 2010–2011, including background information about the students, their ambitions and their views regarding the police profession. The information was collected in a number of countries and at regular intervals to monitor changes that may occur during a recruit’s professional education (RECPOL Citation2010). The longitudinal nature of the project enables analysis of possible changes in the recruits’ attitudes and views about the police profession and their role as aspiring police officers. The data applied in this study were obtained in the first and second rounds of data collection, when the participating recruits were at the beginning of their basic education/training and shortly before finishing it.

The instrument

The instrument used to collect the data was based on a questionnaire called StudData developed at Oslo University College in Norway, to study attitudes of respondents in different professions. The version of the instrument used in the RECPOL project was adjusted to fit the police profession, and was translated and adapted to the languages of the participating countries. The items in the instrument (about 170 in total) focus on the respondent’s choice of education, views on knowledge and skills, job values, operational orientation, attitudes regarding the police profession, and political attitudes and values. The response format is a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 5, with the alternatives ‘disagreeing’ to ‘agreeing’ and the option to give a ‘Don’t know’ answer. The final part of the instrument includes questions about the recruits’ background, answered by filling in blanks or specific categories.

After reviewing the 170 items in the instrument, 21 were identified as relevant for this study, as they were intended to measure the focal aspects (Good relations (towards citizens), Knowledge and Leadership, as previously defined). These items consist of statements regarding competence, knowledge and skills that respondents are invited to rate according to their perceived importance for policing.

Description of data

The participants in this study were police recruits in six countries: Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Scotland, Belgium and Spain (Catalonia). The other countries included in the RECPOL survey, such as Iceland, were excluded as the samples were too small for the intended analyses. Generally, the response rate was high, and, according to the data collectors, non-responses were mostly caused by absence of students at the school on the day of the survey. The response rates were also calculated and compared in more detail. For instance, there were 368 freshmen recruits in total in Sweden at the time of the first round of data collection (http://www.polisen.se), 356 participated in the survey and 333 provided complete data on the items used on the first measurement occasion. Thus, the response rate was more than 90%. A similar participation pattern was found among the recruits in the other participating countries. However, it should be noted that although the response rate was high, there was internal missing data, which explains the different number of participants in the various analyses. The first and second rounds of data collection are referred to as Phases 1 and 2, hereafter. In phase 1, 3424 recruits provided complete data on the items included in the analyses, distributed as presented in .

Table 1. Distribution of police recruits, allocated by gender and country.

Methodology

In measurement practice, it is very difficult to subjectively determine if or how well an item or a test is measuring what is intended. The standard approach when developing and using an instrument is therefore to investigate its reliability and validity. There are a number of methods for doing this, but a common approach is to use methods based on ‘classical test theory’ (Allen and Yen Citation2002). When aiming to measure latent variables, as in this study, it is also necessary to investigate if the test model is consistent with the theoretical model, i.e. measures what is expected. This is often done by analysing the applied instrument’s factor structure (Hambleton et al. Citation2005).

Furthermore, even if the items seem to work well for one population, they may not work as well for another population, as interpretations of format or content may depend on the context. This can be especially problematic if the test has been translated or adapted, e.g. for administration to groups speaking different languages, and the translation changes items’ meaning. In standardised testing, such controls are standard procedures, but not necessarily in research, which raises problems for interpreting data and drawing valid conclusions. According to Hambleton et al. (Citation2005), five technical factors can influence the validity of tests (and other instruments) adapted for use in other languages and cultures: the test itself, selection & training of translators, the process of translation, judgmental designs for adapting tests, and data collection designs & data analysis for establishing equivalence. In this study, we lacked detailed information regarding the process applied in translating the RECPOL-survey instrument into different languages, so we can solely focus on the last technical factor. Since the intention here is to compare longitudinal responses of police recruits in different countries, that differ both culturally and linguistically, adequate analysis of the comparability of the items (and hence outcome of the surveys) is essential.

An informative way of analysing the comparability of data is to use measurement invariance methodology. There are several ways to perform analyses within this framework, but a common approach is to compare the psychometric properties and dimensionality (factor structure) of items used in each language version of the applied instrument (Byrne et al. Citation1989).

The approach in this study was to first analyse the items selected from the RECPOL-survey instrument, to see if they fitted the model equally well in the different language versions. To do this, the psychometric parameters, variability of the scores, and dimensionality (factorial structure) of each version were investigated. Since the study has a longitudinal design, with information collected at different time points, the analyses of changes in recruits within the organisations are based on differences between latent variables measured at different points after controlling for having latent variables based on indicators (items) that are comparable. An autoregressive model is used to investigate the stability of the individual differences from the different measurement occasions.

Analysis

Lisrel version 9.10 software (Jöreskog and Sörbom Citation2013) was used to carry out confirmative factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modelling (SEM).

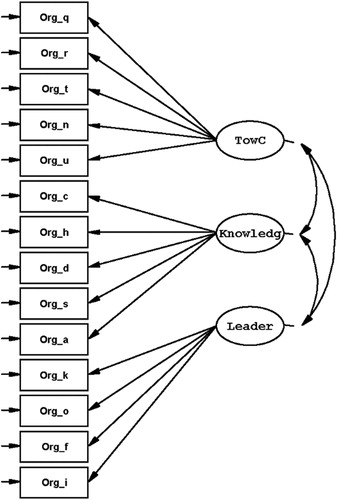

As already described, 21 items from the main survey instrument were initially found relevant for measuring the aspects of interest in this study. These 21 items were then recoded to provide a coherent scale with no opposite orders of agreement. ‘Don’t know’ responses were removed from further analysis. Distributions of responses to the items were also examined to confirm that they met requirements for selected statistical procedures. Items difficult to make sense of (theoretically) were removed from further analyses. Then, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was applied to assess correlations among the items, and extract factors, by principal axis factoring, which is a recommended method when confirmative factor analysis (CFA) is to follow an EFA (Brown Citation2006). The items were grouped into interpretable factors, representing areas relevant to policing according to previous research. Robust maximum likelihood was used to assess the fit of the CFA models, and find potentially significant deviations from normality. The model used for cross-validation, developed by Inzunza (Citation2015b), included the three important aspects (factors named Toward Citizens, Knowledge, and Leadership), all of which were validly measurable according to the applied criteria ().

For cross-validation analysis, we applied following fit indices and thresholds: Pearson’s Chi-square, a low value and non-significant p > .05; comparative fit index (CFI), a value of .90 considered as necessary and a value above or close to .95 indicating a good fit. We also calculated root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) where a value between .05 and −.08 indicative of a reasonable error of approximation and below .05 as good or close fit, and standardised root mean residual (SRMR), deeming values <.08 acceptable (Albright and Park Citation2009, Browne and Cudeck, Citation1992, Hu and Bentler Citation1999).

The analysis showed that 14 of the selected items had potential for valid measurement of the three aspects, and were therefore retained for further analysis, and for forming the scale used in the study. Toward Citizens was measured with five items asking about the importance for a police officer to have tolerance, to appreciate different points of view, to make ethical judgements, to empathise with the situation of others, their values and attitudes, and to handle emotional challenges. Knowledge was measured with five items asking about the importance to have broad, general knowledge, knowledge about planning and organising, an understanding of rules and regulations, practical skills, and theoretical knowledge. Leadership was measured with four items asking about the importance of being able to think in new ways, to have the ability to cooperate with others, to take initiative, and to lead others. The remaining items did not fit the model, either because they were causing cross loadings or being too similar to other items while having a weaker loading on the intended factor. The model of 14 items was therefore used for the following comparative steps.

The presented model was evaluated in several steps. First, it was cross-validated with the Swedish sample as reference. Then, to conduct tests of measurement invariance, multiple-group CFA was applied with constraints on the parameters in a stepwise procedure (Brown Citation2015, Byrne et al. Citation1989). The model was tested to have acceptable fit in equal form, equal factor loadings and equal intercepts based on overall model fit, with a threshold reduction in comparative fit index (CFI) of .01 after applying constraints (Cheung and Rensvold Citation2002). When non-invariant parameters were encountered, partial invariance tests were conducted, and equality constraints of the non-invariant parameters were identified and relaxed.

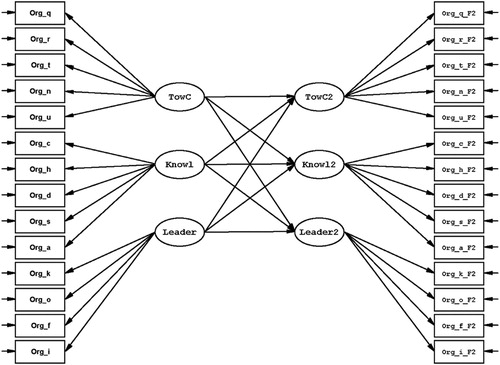

The longitudinal design of the data collection enabled investigation of changes between phases 1 and 2 in views of recruits in countries for which data from both rounds of data collection were available, which was the second purpose of the study. In this analysis, the same multiple-group CFA procedure was applied, followed by autoregressive and cross-lagged panel analysis, to investigate the stability of detected between-country and -organisation differences between Phases 1 and 2. A sizable autoregressive coefficient was regarded as indicative that the reporting on a factor in phase one had not significantly changed among individuals between the two phases, while the cross-lagged analysis tested the stability of relationships between different factors in Phases 1 and 2 (Selig and Little Citation2012). Multi-group differences on factor means represent intra-individual changes while results of the autoregressive and cross-lagged panel analysis indicate inter-individual change.

Results

Differences between organisations

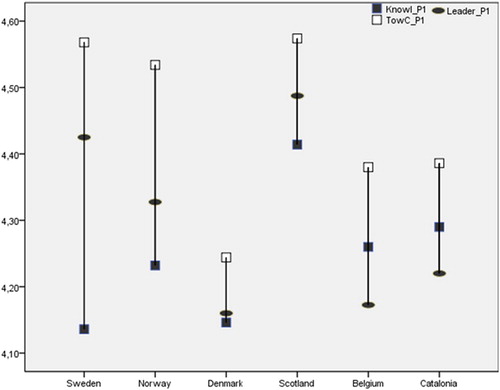

The first aim of this study was to identify possible differences in views of police recruits in the participating European organisations of the three focal aspects, and their importance for policing. For this purpose, the three-factor model developed using data from the Swedish recruits was first cross-validated using data from the other recruits to confirm that it adequately fitted the data (). Descriptive statistics showed that all aspects were considered important for successful policing and that the factor Toward Citizens had the highest scores of the three composite measures. Swedish police recruits reported a mean score of 22.84 (scale from 5 to 25) for TowC compared to 20.68 (scale from 5 to 25) for Knowledge and a mean score of 17.70 (scale from 4 to 20) for Leader. Police recruits in Belgium reported a mean score of 21.89 for TowC, compared to 21.30 for Knowledge, and a mean score of 16.69 for Leader. Composite scores (average/item) for the three focal aspects from each participating country can be seen in .

Figure 2. Composite score (average/item) of each factor from countries with complete data from phase 1. Note that scores are in the upper part of the scale.

Table 2. Fit indices of the three-factor structure model with data from recruits in six participating organisations.

Next, we applied multiple-group CFA, to check that the items in the instrument worked in the same way with participants from all of the organisations. Constraints to test the equality of parameters were applied and non-invariant parameters were identified and freed. After relaxing the parameters causing constraints, meaningful comparisons of the groups representing different organisations could be carried out, with Sweden as the reference group ().

Table 3. Tests of measurement invariance of the model in the six participating organisations.

Unfortunately, the analysis of the data suggested that several items could cause problems if included in a comparison. This could have been due to lack of similar item functioning or differences in the sample sizes between the organisations, as use of equally sized groups generally provides more robust results, especially when comparing complex structures (Brown Citation2015). However, the items probing the Towards citizens factor seemed to work well, except one (see below), and since this was the factor of main interest, the others were dropped and further comparative analyses were based solely on that factor ().

Table 4. Tests of measurement invariance of the factor TowC in the six participating organisations.

The analysis showed that a comparison would become meaningful if item t, the sole item causing a constraint, was omitted. This item asked about values and attitudes and a review concluded that it probably was too vaguely defined and therefore problematic to interpret by the respondents. The differences reported in relation to the Swedish sample (with the latent mean set to zero in the kappa matrix) were all significant. The unstandardised parameter estimate for this factor was significantly lower for recruits in three of the compared countries: estimates for recruits in Denmark, Catalonia and Belgium were .31, .29 and .26 units lower than the estimate for recruits in Sweden, while estimates for recruits in Norway and Scotland were just −.08 and −.05 units lower, respectively.

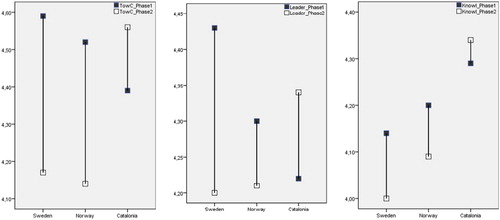

Changes in views over time

A second aim of this study was to investigate if and how time in the organisation would affect recruits’ attitudes. To probe possible changes in recruits’ views about important aspects in policing during their training, information was collected at the beginning of their training (Phase 1) and towards the end of their training (Phase 2). Descriptive information is presented with composite scores (average/item) in . Differences in attitudes were then studied as follows: First, measurement invariance tests (longitudinal factor invariance analyses) were applied to confirm that data from the Swedish, Norwegian and Catalonian organisations (which had provided sufficiently large samples with complete data from the two phases) could be validly applied. This followed the same procedure as before, i.e. investigating the equality of factor loadings and intercepts, but across the two phases. Model fit indices and change, investigated by calculating CFI values, indicated that comparisons were meaningful for most items in the three-factor 14-item model. In the analysis of Swedish and Norwegian datasets, two items were released from constraints, and in the analysis of Catalonian data, one item was released from constraints, before latent mean differences from the measurements in Phase 1 and 2 could be validly investigated. The results show that there was a significant decrease in all three latent means between the two phases (of .45, .14 and .21 in TowC, Knowledge and Leadership, respectively) in Sweden, and two (of .40 and .34 in TowC and Knowledge, respectively in Norway). In Catalonia there was a different pattern, with a significant increase in two latent means, of .17 and .21 in TowC and Leadership, respectively.

Figure 3. Change in composite score (average/item) from countries with complete data from phase 1 and phase 2. Note that scores are in the upper part of the scale.

These differences are unstandardised differences in estimates of latent means and indicate an increase between phases 1 and 2 when positive and a decrease when negative. Thus, for example, a reduction in TowC of .45 units would mean that on average police recruits scored .45 units lower in phase 2 than in phase 1 in this latent factor, indicating that their perception of the importance of good relations towards citizens (as defined here) fell during their training.

The next step in the analysis was to investigate the stability of patterns between phases 1 and 2 by applying an autoregressive cross-lagged model to the data ().

The model with the three latent variables estimated on two occasions showed a reasonable fit to the data (). All autoregressive effects are significant, indicating that individual differences in the measured constructs (TowC, Knowledge and Leadership) were relatively stable between the two occasions. There were no significant cross-lagged effects in Sweden or Norway, but there was a significant negative cross-lagged effect between Knowledge at the first occasion to Leadership at the second occasion in Catalonia. Sizes of the structural model parameters are presented in .

Table 5. Fit indices for autoregressive model with three of the participating organisations.

Table 6. Structural model parameter estimates, standardized parameters.

Discussion

This study addressed views of police recruits regarding characteristics and competencies that are generally regarded as important for good policing. Aims were to explore variations in recruits’ views in countries with sufficient diversity in culture, geographical conditions, police organisation and training to provide illuminating contrasts. A further aim was to explore possible changes in their views during training.

Of course, numerous competences are important for good policing (Inzunza Citation2016), but we focused on three aspects that are often highlighted in the literature, and could be measured by the instrument used for data collection. The first, Towards citizens, refers to the ability to establish good relations with citizens, especially in policing by consent regimes (Jones et al. Citation1996). This is a crucial element of abilities to make ethical judgements, understand situations of others, and handle different perspectives. More operably, it is highly important in strategies such as community policing (Frydl and Skogan Citation2004). The second focal aspect, Knowledge, is highly relevant in any profession, and in policing its importance is probably increasing with increases in the profession’s complexity. Knowledge is a broad concept, but in this context it refers to knowledge that can be formally taught, such as knowledge of rules, regulations, planning strategies, and intelligence-led policing. According to Brodeur and Dupont (Citation2008), the police can be referred to as knowledge workers in this sense. The third factor, Leadership, is of high and probably increasing importance as it is often claimed that police officers are policing increasingly large groups of citizens, and must have the ability to take the initiative, lead others and think in new ways to solve problems. However, the needs for this are likely to vary widely, depending on the role of police in specific contexts, as reflected in variations in police to citizen ratios. In policing, there are also needs to take decisions, often quickly and under pressure, at both operational and management levels (Aepli et al. Citation2011). These three areas are, of course, interconnected, as confirmed by the factor structure of the model used in this study.

When making comparisons based on different language versions of an instrument, as in this study, the comparability of the data should be checked using measurement invariance methodology. This is too often neglected, which can be problematic as it can lead to invalid findings and incorrect conclusions. Thus, another aim of this study was to highlight the importance of measurement invariance analysis and illustrate the procedures. It was, of course, also essential for addressing the research questions regarding variations in police recruits’ views. However, it shows (inter alia) that translating an instrument into multiple languages and administering it in different cultural contexts is not problem-free, even if it seems ideal for comparisons.

Another issue that should be considered is the risk of measurement error, which is always present to some degree. One such source of error is ‘social desirability’, i.e. respondents adjusting their responses according to what they think is expected or desired. This can be especially prominent in self-reported measures, when respondents try to identify the ‘right’ or politically correct answers instead of giving their honest opinions. This ‘casting’ effect may cause police recruits to answer in ways they think are correct (Alain and Grégoire Citation2008) and should be considered a potential threat to validity in all self-report measures, especially if there are stakes for the respondents involved. Previous research has also shown that the propensity to inflate an image is especially problematic in hiring situations (Donovan et al. Citation2003). However, social desirability may also be a subconscious process, influenced by the social context, such as the recruits’ organisations. It is not easy to account for this methodologically, but the risk can be evaluated to some degree by considering incentives for the respondents and the likelihood that they will provide honest information. In this study there were no stakes attached to responses, so the problem of social desirability is expected to be minimal. This is supported by the finding that some recruits’ responses differed in the two phases, suggesting that experience and the acquisition of more knowledge during their training genuinely influenced their responses.

Regarding the issue of validity, the analysis confirmed that the factor structure was consistent with theoretical expectations, i.e. three factors were identified, but it also showed that there were some problems in terms of data not being entirely comparable between countries. This is not surprising since it is a common problem when using data obtained from participants with different languages and/or cultures. However, it strongly supports the notion that comparisons of theoretical constructs that are not directly observable should be made with caution. It also shows the necessity of carefully investigating the validity of items, and raises concerns about using the particular datasets for comparisons. Since some of the items in the model were identified as problematic in some of the analyses, partial invariance was tested. It should be noted, that this does not mean that items were the only problem, it could have been an effect of the constructed three-factor model, or the differences in sample sizes (Brown Citation2015).

Despite these caveats, the main purpose of the study was to compare views of recruits between and within organisations, and some of these comparisons could be validly made. Six organisations from six countries were originally selected for comparisons: Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Scotland, Catalonia (Spain) and Belgium, constituting most of the participating countries in the RECPOL survey. Naturally, broader geographic coverage would have been desirable, for instance, inclusion of countries from eastern and south-eastern Europe. However, the countries included were interesting for comparisons, as they provided sufficient diversity in geographical conditions and police cultures. Sweden, Norway and Denmark all have Scandinavian policing models, characterised by a centralised police system with relatively long police education and training (Holmberg Citation2014, Høigård Citation2011). These provide interesting comparisons to Scotland, where the police training is shorter, with less academic content, but there are higher proportions of police officers than in the Scandinavian countries. Scotland also has a different type of system, with a traditional local police culture involving close relations with citizens, although it is moving towards higher centralisation following recent reforms (Terpstra and Fyfe Citation2015). The organisations in Belgium and Catalonia also provide interesting comparisons, due to their relatively short police training, military origin of the police, and complex systems (Blanco Citation2014, Devroe and Ponsaers Citation2013). However, it should be noted that even if these are ‘typical’ characteristics of other organisations, the results should not be generalised beyond the countries included in the study.

Some interesting findings were made. Overall, the results indicate that recruits in organisations in similar police systems have similar views regarding the focal aspects. More items could be included in comparisons between Sweden, Denmark, Scotland and Norway, and fewer when including Catalonia, Spain and Belgium, which indicates differences that may be at system level. The first group of police organisations are closer to the Anglo-Saxon tradition, while the others are closer to the continental tradition, with a fragmented organisation and military origin (den Boer Citation1999). This could affect the findings in several ways. The three-factor structure with the dimensions Knowledge and Leadership did not work well for comparisons between the Scandinavian countries and Belgium or Catalonia. This may be due to differences in the answer patterns, arising from differences in interconnections of the two dimensions. The contrast between the hierarchical structures in Catalonia and Belgium, with regional or federal and local police, and longer history of national police in Scandinavia and Scotland may also be relevant. Another indication of the relation between these two dimensions was seen in the longitudinal model, which indicated a significant cross-lagged effect in Catalonia. This is indicative of a contextual change between the first and second measurements that influenced the police students’ responses.

Regarding the aspect of most interest in this study; the relations towards citizen-factor (TowC), most items seemed to work well. The between-organisation comparisons showed that police students in Sweden, Norway and Scotland regarded this as more important for successful policing than students in Denmark, Catalonia and Belgium at the beginning of their training. This suggests a division that may be linked to different policing philosophies, for instance the military traditions in Catalonia and policing by consent traditions in Sweden and Norway. The police culture in Scotland also reportedly focuses on dialogue and community interaction, with indirect promotion of strategies such as de-escalation, keeping things calm and building trust (Gorringe and Rosie Citation2010). The difference may also reflect differences in perceptions of the police by the public, since the students responses’ in Phase 1 were collected approximately three weeks after commencing their training to become police officers.

For the longitudinal analysis, data from both measurement occasions were used. For this step, data from only three countries were included, due to insufficiency of data from the second occasion from participants in Belgium, Scotland, and Denmark. A limitation of the chosen approach is that it provides indications of whether or not items measured the latent variables in a similar way, but not reasons why some worked differently in different settings. This is because measurement non-equivalence may be due to translation or adaptation problems, or cultural differences that lead recruits to interpret similar items in different ways. To probe such reasons, qualitative approaches are needed, which were not applied in this study.

In this comparison of recruits within organisations, it was found that all three factors could be included in analyses of the data from Sweden, Norway and Catalonia. This is because the measurement invariance tests indicated that views of recruits in these countries regarding all three factors (Towards citizens, Knowledge, and Leadership) on the two occasions could be compared. Interesting patterns emerged when studying changes in their views over time. Police students from Sweden and Norway regarded good relations with citizens more highly than recruits from other countries at the start of their training, but their rating of its importance was lower on the second occasion. Swedish students also rated the importance of leadership skills and theoretical knowledge lower on the second occasion. Patterns of responses of students in Norway were similar, except that their views on the importance of leadership did not change. An opposite trend in views of recruits in Catalonia was detected, as they regarded good relations with citizens as much more important towards the end of their training than at the start. They also regarded leadership as more important towards the end of their training.

We can only speculate about reasons for these differences in changes over time. However, the differences in length of the education and training programmes may be important factors. In the organisations with relatively long training and practice, the extensive information provided about requirements to perform well as a police officer may shift prioritised aspects. In Sweden for instance, there is a clear message in the recruiting information that communication with citizens is highly important, so applicants learn this and are careful to show their awareness of the message to the recruiters. When they enter the organisation, they may still feel a need to show and communicate this awareness, accounting for their high initial scores in this respect. However, after socialisation in the organisation and encountering all the other required competences and practical expectations in the work settings, the service-oriented aspects may be downgraded to some degree. Other sources of evidence that indicate a mismatch between intentions of the Swedish police organisation and practices in the organisation can be seen in other closely related fields. This may also indicate that the content of what is taught at the academy is not always consistent with what is seen in the field, for various reasons. For example, the idea that police work should be based on research, and the importance of adopting an evidence-based policing approach is often expressed by the Swedish police organisation. However, some studies indicate that the academic content taught at the academy is not reflected in the practical work environment. For instance, Brante et al. (Citation2015) compared Swedish police employees with employees in 17 other fields such as nursing, teaching and social work, and found they were the least likely to adhere to relevant research.

In other systems, such as in Belgium or Catalonia, other factors may be influential. Given the historical closeness to the military, recruits’ initial image of the police may be largely as crime fighters, but the training may present another more service-oriented image. The relative amounts of time spent in the academy and outside the academy in training may also influence recruits’ perceptions of the importance of each aspect. For instance, in Catalonia there is a tradition of promoting localism and thus closeness to the citizens in police work, which is expressed in the description of the mission, requirements and selection (Inzunza Citation2016, van Ewijk Citation2014). During the data collection period, this was particularly pronounced as one of the arguments for replacing Spanish national police with Mossos d’Esquadra was to have a force that was close to the citizens. Thus, the amount of time spent in the field may be of interest in future investigations of recruits’ attitudes. It is also noteworthy that the rise in Catalonian students’ rating of the importance of towards citizens during their training brought their rating closer to that of the Swedish and Norwegian students than it was at the start of their training.

To conclude, this study has shown that it is possible to create a useful scale for measuring the three focal qualities from the main instrument, although some data had to be sacrificed for valid between-organisation comparisons and changes in views over time. It shows that quality of the data is important (as always), but also that sufficiently large samples are essential for these kinds of comparisons. Measurement invariance must also be rigorously checked, and this is not a problem solely restricted to the RECPOL survey data, it is a well-known problem when using translated instruments, or instruments developed for one population to survey another population.

The study did provide some interesting findings. First, that views of what is important in a future profession can change in different ways during education, but perhaps mostly during practical training, when both theoretical knowledge and practical understanding are acquired, with and through exposure to the culture in particular context. Specifically, our results revealed variations of this kind in views of police recruits in different organisations regarding the importance of good relations with citizens.

The limited number of participating countries with sufficient data from the first and second phases was a limitation of the study, and a common problem in longitudinal studies, especially for comparisons of several populations or groups.

Future research will focus on qualitative investigations of reasons for differences and changes in police recruits’ and officers’ views, to assess the validity of assumptions in this study, and other possible mechanisms. Another aim is to include more information from the main survey, such as the recruits’ ages and gender, in similar analyses to see if any patterns in the recruits’ views can be explained by demographic variables.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aebi, M.F., et al., 2014. European sourcebook of crime and criminal justice statistics. 5th ed. European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI). Helsinki: Hakapaino Oy.

- Aepli, P., Ribaux, O., and Summerfield, E., 2011. Decision making in policing: operations and management. Lausanne: EPFL Press.

- Alain, M., and Baril, C., 2005. Crime prevention, crime repression, and policing: attitudes of police recruits towards their role in crime control. International Journal of comparative and applied criminal Justice, 29 (2), 123–148. doi: 10.1080/01924036.2005.9678737

- Alain, M., and Grégoire, M., 2008. Can ethics survive the shock of the job? Quebec's police recruits confront reality. Policing & society, 18 (2), 169–189. doi: 10.1080/10439460802008702

- Albright, J.J., and Park, H.M., 2009. Confirmatory factor analysis using Amos, LISREL, Mplus, and SAS/STAT CALIS, The Trustees of Indiana University, Vol. 1, 1–85.

- Allen, M.J., and Yen, W.M., 2002. Introduction to measurement theory. Long Grove, IL: Waveland.

- Bakker, A.B., and Heuven, E., 2006. Emotional dissonance, burnout, and in-role performance among nurses and police officers. International Journal of stress management, 13 (4), 423–440. doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.13.4.423

- Bayley, D.H., 1999. Policing: the world stage. In: R. I. Mawby, ed. Policing across the world: issues for the twenty-first century. London: UCL Press, 3–12.

- Black, J., 2000. Personality testing and police. New Zealand journal of psychology, 29 (1), 2–9.

- Blanco, S.H., 2014. Pandillas en Cataluña. El abordaje desde la Policia de la generalitat–mossos d’Esquadra. Revista Policía y Seguridad pública, 1 (2), 95–130. doi: 10.5377/rpsp.v1i2.1360

- Brante, T., et al., 2015. Professionerna i kunskapssamhället, En jämförande studie av svenska professioner. Stockholm: Liber.

- Brodeur, J.-P., and Dupont, B., 2008. Introductory essay: the role of knowledge and networks in policing. In: T. Williamson, ed. The handbook of knowledge-based policing: current conceptions and future directions. West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 9–33.

- Brogden, M., 1999. Community policing as cherry pie. In: R.I. Mawby, ed. Policing across the world: Issues for the twenty-first century. London: UCL Press, 167–186.

- Brown, T.A., 2006. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Brown, T.A., 2015. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Browne, M.W., and Cudeck, R., 1992. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological methods & research, 21 (2), 230–258. doi: 10.1177/0049124192021002005

- Byrne, B.M., Shavelson, R.J., and Muthén, B., 1989. Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological bulletin, 105 (3), 456–466. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.456

- Cheung, G.W., and Rensvold, R.B., 2002. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural equation modeling, 9 (2), 233–255. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

- Clarke, S., 2013. Trends in crime and criminal justice, 2010. Eurostat: statistics in focus, 8. Luxembourg: European Union.

- Cole, B.A., 1999. Post-colonial systems. In: R. Mawby, ed. Policing across the world: issue for the twenty-first century. London: UCL Press, 88–108.

- Davis, M.H., 1996. Empathy: a social psychological approach. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- De Maillard, J., and Roché, S., 2018. Studying policing comparatively: obstacles, preliminary results and promises. Policing and society, 28 (4), 385–397. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2016.1240172

- De Schrijver, A., and Maesschalck, J., 2015. The development of moral reasoning skills in police recruits. Policing: an international Journal of police strategies & management, 38 (1), 102–116. doi: 10.1108/PIJPSM-09-2014-0091

- den Boer, M., 1999. Internationalization: a challenge to police organizations in Europe. In: R.I. Mawby, ed. Policing across the world: issues for the twenty-first century. London: UCL Press, 59–74.

- Devroe, E., and Ponsaers, P., 2013. Reforming the Belgian police system between central and local. In: N.R. Fyfe, J. Terpstra, and P. Tops, ed. Centralizing forces? comparative perspectives on contemporary police reform in northern and Western Europe. Eleven: The Hague/Boom Legal Publishers, 77–98.

- Donovan, J.J., Dwight, S.A., and Hurtz, G.M., 2003. An assessment of the prevalence, severity, and verifiability of entry-level applicant faking using the randomized response technique. Human performance, 16 (1), 81–106. doi: 10.1207/S15327043HUP1601_4

- Eraut, M., 2004. Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in continuing education, 26 (2), 247–273. doi: 10.1080/158037042000225245

- Frydl, K., and Skogan, W., 2004. Fairness and effectiveness in policing: the evidence. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Gorringe, H., and Rosie, M., 2010. The ‘Scottish’Approach? The discursive construction of a national police force. The sociological review, 58 (1), 65–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2009.01875.x

- Hambleton, R.K., Merenda, P.F., and Spielberger, C.D., 2005. Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross-cultural assessment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Henson, B., et al., 2010. Do good recruits make good cops? Problems predicting and measuring academy and street-level success. Police quarterly, 13 (1), 5–26. doi: 10.1177/1098611109357320

- Holmberg, L., 2014. Scandinavian police reforms: can you have your cake and eat it, too? Police practice and research, 15 (6), 447–460. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2013.795745

- Holmberg, U., and Christianson, S.Å., 2002. Murderers’ and sexual offenders’ experiences of police interviews and their inclination to admit or deny crimes. Behavioral sciences & the law, 20 (1-2), 31–45. doi: 10.1002/bsl.470

- Hu, L.T., and Bentler, P.M., 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6 (1), 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

- Høigård, C., 2011. Policing the north. Crime and justice, 40 (1), 265–348. doi: 10.1086/659840

- Inzunza, M., 2015a. Empathy from a police work perspective. Journal of scandinavian studies in criminology and crime prevention, 16 (1), 60–75. doi: 10.1080/14043858.2014.987518

- Inzunza, M., 2015b. Suitability in law enforcement: assessing multifaceted selection criteria. Doctoral thesis. University of Umeå, Umeå. Avaialble from http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A866376&dswid=2527.

- Inzunza, M., 2016. Selection practitioners’ views on recruitment criteria for the profile of police officers: a comparison between two police organizations. International journal of law, crime and justice, 45, 103–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlcj.2015.12.001

- Jones, T., Newburn, T., and Smith, D.J., 1996. Policing and the idea of democracy. The British journal of criminology, 36 (2), 182–198. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a014081

- Jöreskog, K.G., and Sörbom, D., 2013. LISREL 9.1 for Windows [Computer software]. Skokie, IL: Scientific Software.

- Kakar, S., 1998. Self-evaluations of police performance: an analysis of the relationship between police officers’ education level and job performance. Policing: an international journal of police strategies & management, 21 (4), 632–647. doi: 10.1108/13639519810241665

- Korsell, L., Wallstrom, K., and Skinnari, J., 2007. Unlawful influence directed at public servants: from harassment, threats and violence to corruption. European journal of crime criminal Law and criminal Justice, 15 (3/4), 335–358.

- Lord, V.B., and Friday, P.C., 2008. What really influences officer attitudes toward COP? The importance of context. police quarterly, 11 (2), 220–238. doi: 10.1177/1098611108314569

- Maddox, L., Lee, D., and Barker, C., 2011. Police empathy and victim PTSD as potential factors in rape case attrition. Journal of police and criminal psychology, 26 (2), 112–117. doi: 10.1007/s11896-010-9075-6

- McGloin, J.M., 2003. Shifting paradigms: policing in Northern Ireland. Policing: an international journal of police strategies & management, 26 (1), 118–143. doi: 10.1108/13639510310460323

- Meadows, R.J., 1985. Police training strategies and the role perceptions of police recruits. Journal of police and criminal psychology, 1 (2), 40–47. doi: 10.1007/BF02823248

- Paterson, C., 2011. Adding value? A review of the international literature on the role of higher education in police training and education. Police practice and research, 12 (4), 286–297. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2011.563969

- Phillips, S.W., 2015. Police recruit attitudes toward the use of unnecessary force. Police practice and research, 16 (1), 51–64. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2013.845942

- Ponsaers, P., 2001. Reading about “community (oriented) policing” and police models. Policing: an international journal of police strategies & management, 24 (4), 470–497. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000006496

- Prieto, G., 2015. Mapa de la policía en España por comunidades autónomas. [Map of the police in Spain by autonomous regions]. http://geografiainfinita.com/2015/01/mapa-de-la-policia-en-espana/.

- Recasens, A., and Ponsaers, P., 2014. Policing Barcelona. In P. Ponsaers, A. Edwards, A. Verhage, and A. Recasens i Brunet, eds. European journal of policing studies, special issue policing European metropolises. Antwerpen/Apeldoorn: Maklu, Vol. 2, nr 1, 110-128.

- RECPOL project at Norwegian Police University College., 2010. Avaialble 20 October, 2017, from https://www.phs.no/en/research/forskningsomrader/politiets-organisasjon-kultur-og-adferd/recpol/.

- Roan, L., et al., 2009. Social perspective taking. Technical Report No. 1259, US Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, Arlington, VA.

- Roberg, R., and Bonn, S., 2004. Higher education and policing: where are we now? Policing: an international journal of police strategies & management, 27 (4), 469–486. doi: 10.1108/13639510410566226

- Rosenbaum, D.P., and Lawrence, D.S., 2017. Teaching procedural justice and communication skills during police–community encounters: results of a randomized control trial with police recruits. Journal of experimental criminology, 13 (3), 293–319. doi: 10.1007/s11292-017-9293-3

- Rydberg, J., and Terrill, W., 2010. The effect of higher education on police behavior. Police quarterly, 13 (1), 92–120. doi: 10.1177/1098611109357325

- Sanders, B.A., 2003. Maybe there’s no such thing as a “good cop”: organizational challenges in selecting quality officers. Policing: an international journal of police strategies & management, 26 (2), 313–328. doi: 10.1108/13639510310475787

- Schafer, J.A., 2009. Developing effective leadership in policing: perils, pitfalls, and paths forward. Policing: an international journal of police strategies & management, 32 (2), 238–260. doi: 10.1108/13639510910958163

- Selig, J.P., and Little, T.D., 2012. Autoregressive and cross-lagged panel analysis for longitudinal data. In: B. Laursen, T. D. Little, and N. A. Card, ed. Handbook of developmental research methods. New York: Guilford, 265–278.

- Singer, T., et al., 2006. Empathic neural responses are modulated by the perceived fairness of others. Nature, 439 (7075), 466–469. doi: 10.1038/nature04271

- Smith, S.M., and Aamodt, M.G., 1997. The relationship between education, experience, and police performance. Journal of police and criminal psychology, 12 (2), 7–14. doi: 10.1007/BF02806696

- Terpstra, J., and Fyfe, N.R., 2015. Mind the implementation gap? Police reform and local policing in the Netherlands and Scotland. Criminology & criminal Justice, 15 (5), 527–544. doi: 10.1177/1748895815572162

- van Ewijk, A.R., 2014. Meanings and motives before measures: The ‘what’and ‘why’of diversity within the Mossos d’Esquadra and the Politie Utrecht. Social inclusion, 2 (3), 60–74. doi: 10.17645/si.v2i3.28

- Van Maanen, J., 1975. Police socialization: a longitudinal examination of job attitudes in an urban police department. Administrative science quarterly, 20, 207–228. doi: 10.2307/2391695