ABSTRACT

How do police officers respond to public emergencies in developing countries where state institutions struggle to protect citizens and officers alike? This paper investigates police response to the COVID-19 crisis in Pakistan and develops an analytical framework of ‘procedural informality’, a condition whereby state policies are constructed and conveyed to state officials with the tacit acceptance that these are likely to be implemented through informal practice. Procedural informality, therefore, is central to official state practice. It is argued that procedural informality manifested itself in Pakistan during the COVID-19 pandemic in three ways: (1) due to a lack of support from the government, it enabled officers to rely on interpersonal connections within the private sector; (2) intra-organisationally, it forced the police to make hasty decisions due to contradictory policies that strained the workforce, but also allowed it to creatively manage demand; and (3) it compelled the police to respond to non-compliance with a heavy hand, whilst equipping them to protect vulnerable communities and maintain individual relationships. In this way, procedural informality enabled the police to try to meet demand with flexibility, which was encouraged and expected by those interacting with the police. Procedural informality moves beyond the formal-informal dichotomy to show how informality facilitates the implementation of formal policy goals, and the operations of street-level bureaucrats, especially during a crisis. This paper contributes to debates on informality within state institutions and in state practice, while providing empirical insights on police response to COVID-19 from a developing country.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

The COVID-19 health crisis has created multi-dimensional challenges for police organisations worldwide (Jones Citation2020). This has been especially true in countries where public trust in the police has been fragile and where police action against non-compliance and lockdown violations has witnessed clashes between citizens and state security forces, with scores being arrested in conflict-ridden areas (Stone Citation2020). During the pandemic, these multi-dimensional challenges have included conflicts between political actors (such as between state and federal governments) who may be at odds over lockdown rules (Junaidi Citation2020), and in which the police may become involved; the management of negative traits associated with police culture that result in discrimination and malpractice, such as excessive use of force against non-compliance or those potentially infected (Nolan Citation2020); and, dealing with material challenges and resource constraints that hinder the delivery of good police work (Alcadipani et al. Citation2020). This is in addition to other effects the pandemic is likely to have on law enforcement agencies that are yet to be fully explored, such as intra-organisational problems with communication, negative impact on the mental health of police officers, and strained police-community relations (Laufs and Waseem Citation2020).

This paper asks: How are public health emergencies policed in the global South, where some states are unable to guarantee the short- and long-term wellbeing of their citizens? The onset of the COVID-19 emergency and subsequent lockdowns around the world, have seen some of the strictest enforcement measures, some of which have been condemned due to law enforcement agencies violating civil liberties (Ratcliffe Citation2020, Swart Citation2020). While police abuse cannot be ignored and in the context of public health emergencies it warrants even greater critical investigation, this paper suggests that one way to understand police response to the COVID-19 crisis in parts of the global South is through the analytical framework of ‘procedural informality’. To this end, this paper investigates police response to the pandemic in Pakistan during the first four months of the crisis (March-July 2020). Using qualitative methods, this paper shows how police response to the public health crisis depended heavily on the institutionalisation of procedural informality.

Procedural informality can be defined as a condition in which policies (official and unofficial) are constructed by state institutions and conveyed to state officials (e.g. police officers), with the recognition that they will be implemented through informal practice. This framework captures both how policies travel within and between institutions, as well as their street-level implementation. The focus of this framework is not simply on what state officials do, but how and in what context they rely upon informality and how such informality is enabled procedurally by state institutions, frequently through formal practices such as policy notifications. Through this framework, I show how procedural informality is central to official state and bureaucratic practice, and develop this analytical frame as one that can be extended and applied to capture a variety of police practice and procedure.

This paper demonstrates how procedural informality was in motion during the COVID-19 emergency in the case of Pakistan, that witnessed nation-wide lockdowns from late-March, almost 6,500 coronavirus-related deaths between March and September, an increase in arrests and detentions on the part of the police and reactionary assaults on police officers themselves (International Crisis Group Citation2020). It is argued here that, in Pakistan, procedural informality manifested itself in three primary ways: (1) it enabled police officers to rely on informal arrangements made with members of the private sector, due to a lack of support provided by the provincial and federal governments; (2) intra-institutionally, it led police management to make hasty decisions and interpret haphazardly drafted policies that strained internal communication and stretched the workforce, but also allowed it to creatively meet expectations; and (3) it had mixed effects on police-society relations, in that officers relied on informal practices to deal with non-compliance and internal migration, which resulted in police heavy-handedness and corruption in certain instances but also saw officers make strategic choices that benefited and safe-guarded the interests of civilians. In this way, procedural informality enabled the police to try and meet increasing and competing demands and the formal requirements of the state through improvisation and circumvention of formal barriers, which was encouraged and expected by those interacting with the police, who overlooked the fairness of such procedures, as long as there was a perception that intended outcomes (in this case, compliance and containment of the virus) were produced.

The following sections elaborate upon the framework of procedural informality, after which I explain the methods adopted for this study. The subsequent sections demonstrate procedural informality in motion, both within police departments and in the dynamics between the police and society, in the context of the COVID-19 emergency. These sections show how procedural informality assists police officers in their attempts to deliver on problematic policies during crises. Finally, this paper discusses some of the risks associated with procedural informality and why it demands further exploration.

Informality and governance

Informality has been broadly discussed in the literature on informal state practice (Benit-Gbaffou Citation2018, Pernegger Citation2020) and informal governance (Polese et al. Citation2016, Baez-Camargo and Ledeneva Citation2017). This literature moves beyond economistic interpretations of informality that sees it as a process outside the ambit of the state, that occurs due to state ineffectiveness. Instead, this literature qualitatively suggests that informality can actually be central to the effectiveness of state and state institutions. Research on governance and public administration shows that state and state officials (including police officers and bureaucrats) intentionally utilise informality (Polese et al. Citation2016) and accommodate it (Chiu Citation2013). Writing on development and urban governance, for example, Davis (Citation2017) explains how governance in certain urban spaces requires informality, as informalisation can aid in the delivery of public services. This is echoed by other urbanists who show how informal practices can help state actors deliver, improve the outcomes of certain policies, and strengthen organisational legitimacy (Polese et al. Citation2016, Pernegger Citation2020). Other works on urban development and governance have similarly explored links between informality and urbanisation, showing how informal practices on the part of state officials fall within a ‘grey area’, a tension between formal rules and norms, what is expected and what can be delivered (Benit-Gbaffou Citation2018).

Research that explores the connections between informality and governance has also studied informal practices in the context of corruption (Baez-Camargo and Ledeneva Citation2017). Here too, the authors recognise that informal practices cannot just be condemned for ensuring corruption, but that they can also ‘promote positive change’ and create pathways to reform, depending upon the functionality of informal practices. This is due to the ability of informality to influence human interactions, which can complement formal, institutional, state-driven interventions (Polese Citation2015). In this way, governance scholars and anthropologists have understood informality as a ‘governance tool’ that prompts both civilians and state officials to take certain initiatives (ibid) and rely on ‘practical norms’, or ‘the various informal, de facto, tacit or latent norms that underlie the practices of actors which diverge from the official norms’ (Sardan Citation2015).

This has also been briefly discussed in the context of policing, also primarily by anthropologists. Kyed (Citation2017), for example, explored ‘informalisation’ on the part of the police in urban Mozambique, to show how certain informal police practices are actually attempts by the police to maintain and better relations with the communities they serve. This is also observed in the work of Jauregui and her exploration of the idea of ‘jugaad’ or improvisation (discussed below). In some jurisdictions, therefore, informal police practices are expected, demanded, and required. This paper departs from a similar logic, that informal practices can aid in the delivery of services and their functionality should be investigated. As the literature on informal state practice cuts across disciplinary boundaries (including governance, urban development, and anthropology), this paper accordingly contributes to an expanding cross-disciplinary interest in informality. In doing so, it echoes the sentiments of scholars who advocate against stigmatising informality and instead ask us to think about informality as co-existing, co-producing or collaborating with formality (Davis Citation2017, Polese Citation2015).

The framework of procedural informality moves beyond the formal-informal dichotomy to further investigate the ‘grey areas’ within which police officials operate, especially during a crisis. This paper thus contributes to debates on informality within and in relation to state institutions and practice (Davis Citation2017), adding to the emerging research on policing COVID-19 in developing countries such as Brazil (Alcadipani et al. Citation2020), South Africa (Stiegler and Bouchard Citation2020), and India (Biswas and Sultana Citation2020). Furthermore, by employing the framework of procedural informality, it shows how police organisations negotiate for legitimacy, thus providing alternative ways to think about police legitimacy (Bottoms and Tankebe Citation2012, Jauregui Citation2013a, Jauregui Citation2016, Kyed Citation2020).

Unpacking ‘procedural informality’

It is widely accepted that ‘informality’ is a complex and contested term (Rubin Citation2018). Broadly, it has strengthened existing understandings of urban politics (Benit-Gbaddou Citation2018), development, and economics, with a growing interest in seeing informality as enabling certain practices of street-level bureaucrats (described as teachers, judges, police officers and others) (Lipsky Citation2010), thereby connecting scholarly concepts to street-level practitioners. Some of the literature that engages with informal practices of state officials tends to focus on corruption and abuse of discretion (Alden Citation2015), that has arguably stigmatised informality and informal practices (Polese Citation2015). Nevertheless, perspectives from the global South have advocated a move beyond the formal-informal dichotomy that tends to see informality as a negative, with formality as the preferred choice, and instead see the two as a ‘dualism’, as complementary practices and processes (Marlow et al. Citation2010), that can form equal parts of state development and governance (Davis Citation2017, Citation2018). These perspectives ask us to avoid seeing ‘informality’ as something negative in or about the developing world that needs to be ‘fixed’. Indeed, this view has been criticised as a ‘double standard’ given that informality can persist in ‘developed’ countries too (Polese Citation2015). Seeing it as a dualism instead of a dichotomy, allows us to realise that informal practices are not just a product of vested interests or greed, but in fact can be sustained by formal procedures, mechanisms and policies, and in return help sustain the formal practices of the state, as the ‘cartilage that keeps solid bones together and allows them to function together’ (Ibid).

As such, the framework of procedural informality offers a chance to view informal state practices through a lens that takes into consideration not just the intra-institutional limitations creating the need for informality, but also the factors and forces beyond the institution that allow, encourage, and enable procedural informality to persist. In doing so, it provides a qualitative lens through which to better grasp aspects of policing in the global South. Furthermore, it challenges whether ‘procedural fairness’ (Boateng Citation2019) can indeed generate greater legitimacy and public trust in the police in violently divided, repressed societies and conflict zones, where formal procedures and authoritarian laws may be designed to disadvantaged certain population groups, and where the quantitative research (such as laboratory experiments) required to empirically investigate the application of procedural justice may be restrictive and even problematic (Davis Citation2020). To borrow from Kyed’s consideration, can informality generate better and more swift outcomes for communities that lack trust in formal legal mechanisms and judicial processes, and by extension, construct greater legitimacy for the police (Kyed Citation2017)? Whilst I do not seek to answer this question entirely, I hope to lay the groundwork for further critical evaluation of informal state and police practices.

As mentioned above, procedural informality can be defined as a condition that captures and describes how state policies are communicated, interpreted and converted into action as informal practices by state officials, to realise the state’s procedural goals (in this case, the enforcement of lockdown restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 outbreak). More precisely, procedural informality refers to the state in which policies permitting departure from formal rules, regulations and procedures, are conveyed to and translated by state officials, and implemented on the ground as informal practices – partly due to the level of discretion already afforded to these figures of authority, and partly due to the impracticality of the policies constructed. Discretion, or the freedom street-level bureaucrats including police officers have to interpret formal rules and procedures through ‘short-cuts’ (Lipsky Citation2010), can thus be construed as a component of procedural informality that is used instrumentally and strategically in the implementation of policies (or lack thereof) through informal practices. Procedural informality, taken as a condition that allows the persistence of informal practices, should be seen as bureaucratic efforts to implement policies that necessitate the ‘bending of rules’ or departure from established procedure, and that can potentially create new institutional norms and practices for actors confronted with the dilemma of what is expected of them and what can be delivered.

In emergency situations, such as public health crises, bureaucratic rules can inevitably become frustrated and policy goals may require implementation through procedural informality. Procedural informality can thus be viewed as an organic component of a system of governance wherein policies are realised and implemented in ways that would not be possible through rigid and formal rules and regulations alone. In a system of governance, formal and informal procedures can thus intersect and complement each other. In other words, procedural informality supplements formal procedures and practices, and by enabling authorities to operate outside the law, helps subvert procedural delays and hindrances created by formal rules (Roy Citation2009, Rubin Citation2018). Procedural informality may be thus become operationalised during a crisis, particularly in the face of institutional pressures and challenges such as resource constraints, increased demand, and a lack of support from other agencies (particularly when other agencies do not have good working relations with the police). Thus, rather than viewing procedural informality as a by-product of institutional weakness or failure, we can perhaps think of procedural informality as a critical component of state practice and governance that allows institutions to proactively, efficiently, and even effectively, get things done. This, of course, can have adverse consequences for individuals perpetuating informality and those on the receiving end of informal practices, as discussed ahead.

This exploratory framework allows us to understand how informality operates on multiple levels: that of the street-level bureaucrats implementing policies (or choosing not to) (what Rubin (Citation2018) calls ‘micro-level practices’), that of the management receiving the policies (through written notifications or verbal commands), and that of the administration or government creating policies. In this way, this framework expands our perceptions about institutions and officials operationalising informality.

Connecting ‘akhpal bandobast’ and ‘jugaad’

To further demonstrate this framework in ways applicable to the case study under consideration, I employ two terms colloquially used in South Asia that embody the informal policy decisions and the informal practices that combine to create the conditions of procedural informality. Together, they help develop the framework proposed.

The first, akhpal bandobast, is derived from conversations with police officers interviewed for this research, who referred to it as ‘how policing is done in our areas’. A Pashto term, akhpal bandobast refers to a direction, order, or advice, that loosely translates to ‘make your own arrangements’, be ‘self-sufficient’ or ‘self-reliant’. As a direction or advice in this context, it is used by the civil administration and police leadership to implicitly or explicitly direct junior officers to use the means necessary to ensure that certain orders are implemented, despite the lack of means necessary to meet these expectations. The direction travels down to the rank-and-file, with a similar expectation and verbal encouragements by the command to ‘just do it, shabash! [well done]’ – a praise that accompanies the request before the latter is complied with, in a fashion that makes the request a socially binding commitment for those on its receiving end. In this manner, akhpal bandobast captures how the creation of policies or instructions that cannot be adequately or legally implemented is translated, communicated, and internalised by police officers responsible for putting it into effect. The slightly impatient command to ‘just do it’ implies a recognition on the part of police management and policymakers that certain orders cannot be met through formal procedure and practice by the rank-and-file, but also hints at a lack of interest on the part of police management on how these policies will be implemented. In this way, it creates a symbolic distance between senior officers, who may not want to be associated with informal practices carried out by juniors should they generate controversy, and the rank-and-file, with the latter being encouraged by the praise ‘shabash’ that gives them the acknowledgement and security they need to know they will be protected after circumventing formal rules and regulations. Akhpal bandobast thus sets the stage for the informal practices that will be carried out through the second concept employed here – jugaad – in the manifestation of procedural informality.

Jugaad (a Hindi word increasingly adopted in the Urdu language) has intrigued scholars working on contemporary South Asia (Jauregui Citation2013a, Prabhu and Jain Citation2015, Bhushan et al. Citation2016). Here, I draw upon Jauregui’s conceptualisation of jugaad, or the routine improvisations, ‘hacks’ or short-cuts, adopted by the Indian police (the subject of Jauregui’s research) to achieve certain outcomes through timeliness, efficiency and effectiveness (Jauregui Citation2013a). Jugaad is similar to other conceptualisations of informal police practices and encapsulates a range of behaviours and interactions between police officers and their audiences, beyond bribe-taking and other forms of police corruption (see Vigneswaran and Hornberger Citation2009, Kyed Citation2017). It can be distinguished from akhpal bandobast in that the former (jugaad) is an activity, practice, or technique (or sets of these), that requires an action, whereas the latter is an unofficial policy guidance given to state actors that can potentially result in the activation of jugaad. I argue that in the event that akhpal bandobast (the guidance) translates into jugaad (the action), procedural informality takes effect.

These two concepts akhpal bandobast (unofficial directions) and jugaad (improvisations) are central components of the persisting condition of procedural informality. In this paper, I show how both ideas were at work during the COVID-19 emergency in Pakistan. The following sections demonstrate how procedural informality can be observed at three different points: (1) in the relationship between the police and other public and private institutions, (2) in the dynamics within the police itself, and (3), in the relationship between police and society.

Methodology

Design

During the COVID-19 pandemic, policing and enforcement generated substantial interest in Pakistan and beyond (Waseem and Rafiq Citation2020). This paper draws on qualitative data gathered remotely through telephonic interviews and an online survey conducted in Pakistan in June and July 2020, while the country was witnessing its first wave of the pandemic. The survey data is used to supplement the data and themes derived from interviews. The purpose behind this mixed-methods approach was to analyse police response to the public health crisis, as well as the impact of the crisis on police officers. This can strengthen our understanding of the policing and public health interface in countries like Pakistan.

Interviews

A total of 28 semi-structured interviews were conducted with serving police officers posted across Pakistan. Police officers were selected based on their role in drafting policies relevant to police work during the pandemic, their posting in a command capacity to oversee the implementation of said policies, or their deployment in the field for the enforcement of public health measures (at police stations, for example). A snowballing technique was used to identify relevant officers and oral consent was taken prior to each interview. Of the officers interviewed, 18 were senior officers, and 5 from the ‘rank-and-file’. All officers were asked about the personal and professional challenges they faced during the first wave of the pandemic, the policies that they had to implement, and their relationship with state and civilian actors, as well as their own colleagues, during this period. Interviews were also conducted with journalists and members of the civil society to gather insights into community perceptions of the police during the pandemic and verify some of the information provided by police officers. Interviews lasted between 15 min to 75 min, depending on the availability of participants. All interviews were translated, transcribed, anonymisedFootnote1 and thematically coded by the author. The themes emerging from these interviews, and the patterns they established, helped construct the framework of ‘procedural informality’.

Survey

Recruitment

An online survey was also conducted with police officers serving between late-March to late-June, during the peak of the first wave, in one city.Footnote2 The survey was distributed between June and July to 400 police officers after buy-in from senior officers who were requested to circulate the survey link across a police unit operational during the crisis. The survey recruited active-duty police officers only and participation was voluntary. It was designed using a software that allowed the survey to be completed in Urdu, anonymously. Because police officers do not have regular access to emails, but a majority use smartphones and WhatsApp for regular correspondence, the link to this survey was distributed via WhatsApp. In the survey, respondents were asked about their access to personal protective equipment (PPE), their stress levels, their communication their peers and supervisors, and their levels of satisfaction with institutional responses to COVID-19.

Response

Of the 400 participants who received the survey, a total of 288 entered it, 117 responded, and 110 completed the survey (completion rate: 38.2%), resulting in a response rate of 27.5%. The low response rate can be attributed to a number of factors: (1) this was the first digital survey distributed across this particular unit, (2) the rank-and-file are unfamiliar with and untrained in digital surveys, (3) there was no incentive or cost attached to completing the survey, and (4) the survey was conducted when the department was under unprecedented pressure due to the public health crisis.

Participants

All responses were generated anonymously, with the rank and gender being the only identity markers collected. The participants consisted mainly of rank-and-file officers (90.66%), including police constables (34.58%), sub-inspectors (50.47%) and inspectors (5.61%). The remainder consisted of superintendents of police (7.48%), senior superintendents of police (0.93%) and deputy inspectors general of police (0.93%). Majority of these participants were male (88.07%), although the number of female respondents was higher than the gender representation typically found in police departments in Pakistan, where female representation remains below two percent (Dawn Citation2017).

Limitations

This research is largely a product of self-reported perceptions and experiences. Because access to the field was not possible due to lockdown restrictions, all interviews were conducted remotely for the safety of the researcher and participants. Access to police officers was sought through telephonic and digital platforms, obstructing the inclusion of observational findings from fieldwork. To address these limitations, open sources such as newspaper reports and webinars produced during the pandemic, as well as data provided by police departments, have also been consulted.

Policing COVID-19 in Pakistan

Police response to COVID-19 in Pakistan makes for an interesting site upon which procedural informality can be observed. In Pakistan, one of the first cases of COVID-19 was reported in February 2020. The first province-wide lockdown was imposed in Sindh on 23rd March 2020, with subsequent provinces following suit. To complement state-mandated lockdowns, provincial governments applied a range of legal frameworks to contain the virus. The frameworks crucial for enforcing lockdown restrictions and policing and punishing violations included Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code, a colonial-era legislation that prohibits public assembly of more than four people in a given area during emergencies, and Section 188 of the Pakistan Penal Code (1860) that prohibits disobedience to orders promulgated by public servants. Together, these two provisions empowered law enforcement agencies to arrest and fine individuals violating lockdowns (Hasan Citation2020). However, a common complaint among all officers was the government’s negligence in consulting police officers prior to imposing lockdown restrictions.

When the lockdown started, very little input was taken from the police by the government and civil administrators. No one asked what sort of challenges we would face. They went ahead and issued orders. Ministers and bureaucrats discussed it between themselves. (PO-19)

According to one officer interviewed, ‘It was complete chaos! My unit received 20–25 contradictory notifications from provincial and federal governments in the first four weeks [of lockdown]. We felt that administration services were really absent from our areas. We were never consulted by them or anyone else for policymaking’ (PO-24). Other officers lamented the lack of clarity within these notifications and their own inability to communicate policy changes to the rank-and-file. ‘The notifications were predominantly in English. They should have been in [local languages] for our rank-and-file who cannot read English. The terminology was difficult to translate’ (PO-05).

Every few days, the government was revising notifications and communication with government officials was confusing. Some notifications were about exemptions but these exemptions were also confusing. For us, this lack of clarity was a signal to be self-reliant. The health department failed us; they were not testing officers properly, even though we were transporting sick patients. (PO-24)

‘Make your own arrangements’

The formal policies constructed beyond of the institution of the police, paved the way for procedural informality, making senior police officers ‘middle-men’ in the path between formal policy and informal practice. To compensate for the gap between state expectations and what the police could deliver (in the absence of a strong working relationship with the public health sector), the officers relied upon ‘gifts’ and ‘personal contacts’ to meet exceeding expectations, and essentially ‘made their own arrangements’ by getting assistance from ‘contacts within the upper class’ (PO-24).

In some cases, this meant turning away from the public sector and relying upon interpersonal relations within the private sector. Some even admitted to turning to NGOs and retired police officers for ‘gifts’ and ‘donations’ to procure food and PPE (PO-23). Others relied upon existing departmental resources and procuring PPE from their own salaries, even though the cost of such equipment increased due to price gouging (PO-24).

Funds had to be repurposed from other departments and we had to procure PPE ourselves. Individual officers used their networks to get masks and soaps, because these supplies were limited due to looting and hoarding. The government did not give adequate support. (PO-08)

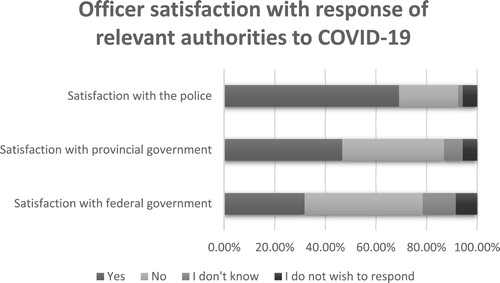

Figure 1. Officers’ levels of satisfaction with the response of the police, provincial government and federal government.

Furthermore, senior officers attributed procedural informality as a condition partly created by these dynamics, in which the role of the police was discounted. The lack of consultation with the police on the part of policymakers, coupled with resource constraints, encouraged officers to engage in additional informal practices (in other words, ‘do jugaad’), including petty corruption (discussed below). Police officers, attributed such informal practices to being left ‘to their own devices’, which fuelled resentment between police and other bureaucrats and public administration services due to unequal allocation of emergency funds.

The thing about funds is that even if provincial and federal governments release [emergency funds], they won’t necessarily come down to the police. They go to the administration services. There is a lack of defined criteria on where the money goes but, overall, it is for SOPs, quarantine facilities, etcetera. But the governments and administration services do not keep the police in mind. So, the police don’t adequate money through this process. When funds are released to the administration services, they should be given directly to the police as well. They don’t. That’s why the police have to repurpose existing funds or make their own arrangements. (PO-08)

However, although procedural informality allows the police to try and deliver in the presence of weak state and bureaucratic support, it complicates the relationship between the police and other public institutions partnering with them during a crisis. Nevertheless, it allows the police to bypass formal agencies and their protocols and find other sectors – in this case, the private sector – to work with, thus blurring the ‘public’ and the ‘private’ in certain circumstances whilst highlighting a mutually beneficial relationship between the two. As explained by another interviewee, the informal provision of PPE to the police during the crisis allowed industrialists and businesses to develop stronger interpersonal connections with individual police officers, thus enabling dependency upon the latter in case the favour needs to be returned (PO-30).

The following section explores how procedural informality manifested itself within the institution of the police.

‘Just manage somehow’

A lack of clarity in policy notifications symbolises problematic communication between the civil administration and the police, due to which confusion within the police resulted in reliance upon informal practices. In producing confusing notifications, policymakers were indirectly relying upon a pre-existing recognition that police officers traditionally rely upon informal practices in the face of resource constraints. ‘The biggest hurdle was the influx of information being communicated to us’, noted one officer.

This really affected us and our junior officers who were getting confused during the first few weeks about what they were being told. And communication suffered between supervisors and the rank-and-file. We had to convince them to just manage somehow. So, for instance, individual officers used their existing connections to get PPE. (PO-08)

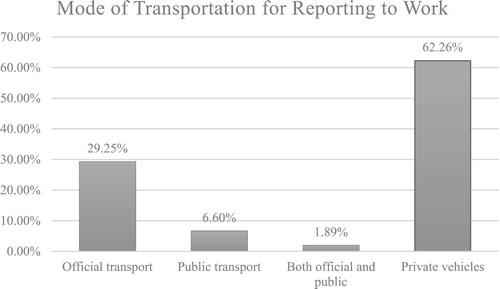

Resource constraints meant that the police had less equipment to rely upon, such as vehicles. This affected officers in two ways. First, several reported using public transport to work, even though the use of public transportation was suspended during the peak of the outbreak (). Survey responses suggest that less than 30% of survey participants had access to official transport, whereas over 62% relied on private vehicles (e.g. motorcycles), indicating that a majority of officers had to get to work on their own accord.

Second, officers reported that suspected individuals (both those violating lockdowns and potential criminals) had to be transported in the same police vehicles available, thus exposing the police and suspected criminals to potentially infected persons and limiting the possibility of physical distancing, particularly due to the lack of testing equipment (such as thermometers) available across police departments.

The rank-and-file also have to transport the accused at this time, in police pick-ups, with fuel constraints, and sometimes officers use their own private vehicles. The accused and the police need to sit together in these vehicles. The police don’t know who is COVID-positive and who isn’t. (PO-21)

The government does not think and makes new legislation. It puts more duties on the police. It does not ask: ‘How will the police perform these duties?’. It doesn’t give the police enough money for additional duties. That’s why the police resort to informal practices – like asking drivers of pick-up trucks to transport violators and their motorcycles to police stations – because the police do not have enough resources to do so themselves. Then, the police have to make arrests, transport individuals [to the police station or courts], and also provide food for people in lock-ups … with no extra resources. So, it is assumed that the police will continue with this informal way of policing. It’s almost as if to enable such practices, we are encouraged to engage in corruption. Now, if the police engage in corruption to meet state demand, why should they not engage in corruption to feed their own children? (PO-17)

Yes, we have resource shortages. But I also don’t see police command and leadership giving material support to junior officers. It’s very much an akhpal bandobast type scene. Continuous provision of PPE isn’t possible. But officers don’t ask the rank-and-file about their needs either. It’s understood, that the juniors will make their own arrangements. The rank-and-file are not prioritised. Senior cops, management, need to ask about the well-being of juniors. (PO-10)

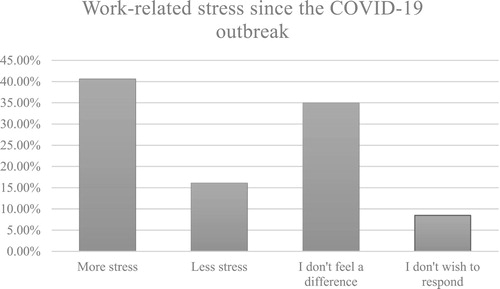

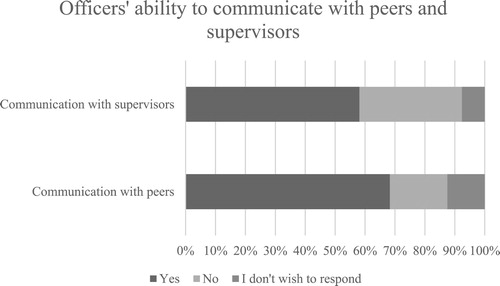

Furthermore, the survey also found that the prevalence of akhpal bandobast (or the direction to ‘just do it, shabash!’) strained channels of communication between senior officers giving the command and junior officers who were expected to implement orders. As shows, while 68% of respondents were able to talk about their problems with their peers, only 58% felt they could speak with their supervisors during the pandemic, indicating a potentially adverse effect of procedural informality on rank-and-file officers in terms of their relationship with junior and senior officers, in addition to the overarching occupational culture that creates a divide between rank-and-file officer and upper management.

Therefore, intra-organisationally, procedural informality creates both possibilities and strains for officers. The following section looks at how procedural informality affected interactions between police officers and civilians more broadly.

‘Business was good!’

Previous sections explored how a lack of consultation by provincial and federal governments, resource constraints, and a general confusion over how to implement lockdowns, encouraged officers to engage in additional informal practices. This section looks at how procedural informality affected police-citizen interactions.

Some of these informal practices were indeed controversial and problematic, such as corporal punishment, and the use of stun-guns against violators in one city (even though it was not deployed elsewhere and there was no official notification authorising its use) (Mubarak Citation2020).Footnote3 Other informal practices, however, such as ‘petty corruption’ that were intended to meet conflicting demand (Baez-Camargo and Ledeneva Citation2017), did not arguably benefit the police alone but also local businesses that were suffering economically during lockdowns. Procedural informality enabled officers to exercise greater discretion when dealing with violators, especially market vendors who needed to stay open to maintain their livelihood.

As one officer explained, ‘When the burden on the police increased, officers … found ways to make money during this period, by taking bribes for letting people go for violating lockdowns’. (PO-05). Others, took money from shopkeepers in exchange for keeping shops open. ‘So, business was good!’ (PO-05).

People started coming up with loopholes when restrictions were in place. They would keep the [shop] shutters down when they knew the police were patrolling. When the police left, the shopkeepers put their shutters up again. Some kept their side-entrances open which officers chose to ignore. (PO-27)

The police really troubled us. They were taking money to allow shops to stay open, or re-open. They were making ‘settings’ with some shop-keepers. Stores and bakeries were paying money to keep their businesses open. (C-08)

A few weeks into the lockdown, the police did not like arresting people. Those who come into custody, might need to be tested. This creates addition strain on the police. The jail and prisons officials also do not want more prisoners. So, we started making less arrests. Because if we arrest them, where will we take them? (PO-27)

Perhaps the most obvious intersection, however, upon which procedural informality can be observed is the relationship between street-level officers and communities at risk of infection, including religious groups that refused to abide by lockdown restrictions that prohibited congregations for Friday prayers at mosques and other religious activities. The lack of compliance on the part of selected groups also led to sporadic assaults on officers in some cities (The News Citation2020). Police officers complained that non-cooperation by religious groups, including those in quarantine, gave officers ‘trouble’. ‘There were more than 600 members of [one congregation] quarantined in our area, out of which maybe 50 or 60 tested positive for COVID-19’, explained one officer in charge of monitoring religious gatherings. ‘They gave us a lot of trouble when they were in quarantine. They were constantly complaining and wanting to leave’ (PO-31). Similar sentiments were expressed by journalists covering state response to COVID-19, who noted that by directing the police to enforce restrictions on religious groups instead of communicating with religious leaders directly, governments risked the lives of police officers, including one officer who was stabbed while preventing a member of a religious organisation from escaping quarantine (Naya Daur Citation2020).

The religious groups were not compliant. Frankly, the police should not have been forced to stop religious groups from congregating. The governments should have engaged local representatives of mosques and religious committees and other local leaders and told them about the new rules, not just leave the enforcement to the police. By asking the police to enforce, they are creating problems for police-community relations. (C-01)

Beyond routine congregations, the group most at risk of contracting and spreading COVID-19 was the Zaireen (religious pilgrims) returning from Iran who needed to be quarantined in the province of Balochistan and then escorted home to other provinces.

Zaireen posed a challenge for us as we had to quarantine them in different provinces. But the police were not properly trained, and the Zaireen were getting tired. We were worried that it would create a volatile situation because some of them kept running away from quarantine facilities and it was difficult to ensure compliance. Some of them had to be transferred to [the provinces of] Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Gilgit Baltistan from Punjab and Balochistan. This transportation had to be arranged by the police, paramilitary and the civil administration. We had to make arrangements for them – sometimes, using our own money. (PO-16)

In other interviews, officers admitted to receiving instructions that advised them to practice informality when dealing with citizens. Post-lockdown, pockets of Pakistan’s major cities saw smart lockdowns imposed to curb infection rates. Some of these measures required officers to rely on practices traditionally used to monitor traffic and control crowds in the face of security threats and resource-constraints.

The civil administration was issuing orders without consulting us. We were doing what they asked. When the policies changed to enforce smart lockdowns, the police were expected to seal certain localities. Basically, we were told to seal them by bringing in water tankers and large containers, and placing them at strategic junctures to seal roads and inhibit the movement and traffic of people. (PO-19)

This section thus demonstrates that procedural informality allowed police officers to employ informal practices to deliver on a range of demands, from transporting pilgrims and preventing congregations, to punishing violators, preventing movement and ensuring that shopkeepers abided by lockdown regulations. However, procedural informality also allowed police officers to employ greater flexibility and ignore the ‘short-cuts’ being taken by those violating lockdowns. The effects of procedural informality on police-civilian interactions, however, were mixed: the police resorted to heavy-handedness in some areas; elsewhere procedural informality allowed officers to maintain individual relations with prominent members of the Pakistani elite. As one officer explained,

When the lockdowns were eased, parlours and salons had to remain shut. But one of the biggest salon owners called me repeatedly and said, ‘You are ignoring the parlours that are open in other neighbourhoods, but your officers are not allowing me to open mine’. I explained to her that those areas did not fall within my jurisdiction. Nevertheless, I had to maintain relations, so I asked my officers to stop pestering the employees at her salon. (PO-19)

Conclusion

This paper argued that in some countries in order to police a crisis such as COVID-19, police officers need to rely on procedural informality, a condition facilitated by state-driven policies that, when communicated officers tasked with implementing these policies, result in dependency upon informal practices. Not only is this process known to state institutions enabling procedural informality, it is allowed for successfully implementing formal procedures. In this way, state institutions and officials collectively create the dualism between formality and informality, facilitating informal governance. In the case of policing the COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan, it was argued that state response to the crisis, and the subsequent enforcement of public health measures, were channelled through procedural informality, resulting in informal practices adopted by police officers, which had mixed impact on inter- and intra-institutional dynamics and on officer-civilian interactions.

Furthermore, the discussion above demonstrated that reliance upon procedural informality created opportunities for better interactions with civilians, to an extent, improved police effectiveness at implementing lockdown restrictions, and ensured compliance in the absence of clear policies and resource constraints. In this way, I suggest that procedural informality – if channelled correctly – may improve police legitimacy in certain contexts, and thus as a conceptual framework it warrants greater ethnographic exploration. Further research on informal police practices can help explain the causes and effects of procedural informality, which can create evidence for better policies applicable to policing in the global South. Accounting for informal police practices in police reform efforts in developing countries may produce localised policies that are socially and culturally better suited for certain contexts. In countries such as Pakistan where fair treatment by the police is unrealisable due to socio-political factors and class divides that negate the possibility of equal provision of public services, procedural informality helps the police have better interactions with civilians – especially those more marginalised (such as vendors), and those with lesser social capital who need the police to ‘look the other way’, perhaps in exchange for monetary compensation. In the absence of conditions that can facilitate an equal and indiscriminate provision of public services, therefore, procedural informality can, to an extent, allow the police to deliver, meet competing expectations, and fight to maintain their legitimacy.

However, procedural informality also carries the risk of straining relations. Although it allows officers to avoid implementing problematic policies that can hurt public trust in the police, procedural informality can similarly be abused by elites, or other state institutions, to capture the police for political or economic gains. This risks the manifestation of procedural informality in ways that can compromise the citizenship of marginalised groups and minority residents, especially those likely to be discriminated against by police officers, as shown in a study on the policing of the transgender community in Pakistan (Nisar and Masood Citation2019). This, too, warrants further research. Nevertheless, as a condition procedural informality can be channelled and optimised in ways that foster relations between officers and civilians, particularly civilians who benefit more from bypassing the formal rules and procedures. The idea here is not to advocate for a blanket application of informality, nor to stigmatise it or propose reforms that deny officers from relying on procedural informality when necessary. Rather, it is to show its application and functionality, proposing that informality be channelled appropriately rather than eradicated or exploited, along the lines of Polese (Citation2015) who recommends its management and direction so that it ‘complements’ formal procedure. Conceptually and empirically, however, procedural informality and its effects on police legitimacy should be explored further in policy-driven research on policing and informal governance in the global South.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sharmeen Khan, Yasser Kureshi, Adnan Rafiq and the United States Institute of Peace team in Pakistan for their assistance with this research, and anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A random coding of a letter and a number has been assigned to each interview. So, ‘PO’ represents an interview with a police officer, and ‘C’ an interview with a civilian (e.g. PO-08 represents an interview conducted with a police officer).

2 Location details have been withheld to protect the anonymity of survey participants.

3 This ‘stun gun therapy’ was subsequently discontinued after public outcry and appeals by Amnesty International.

References

- Alcadipani, R., et al. 2020. Street-level bureaucrats under COVID-19: Police officers’ responses in constrained settings. Administrative theory and praxis [online]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10841806.2020.1771906 [Accessed 12 September 2020].

- Alden, S., 2015. Discretion on the frontline: The street-level bureaucrat in English statutory homelessness services. Social policy and society, 14 (1), 63–77.

- Baez-Camargo, C., and Ledeneva, A., 2017. Where does informality stop and corruption begin? Informal governance and the public/private crossover in Mexico, Russia and Tanzania. The Slavonic and East European review, 95 (1), 49–75.

- Benit-Gbaffou, C., 2018. Unpacking state practices in city-making, in conversations with Ananya Roy. The journal of development studies, 54 (12), 2139–2148.

- Bhushan, B., et al. 2016. Understanding jugaad: multidisciplinary approach. Project Report. Department of Human and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, India.

- Biswas, D., and Sultana, P. 2020. Policing during the time of Corona: The Indian context. Policing: A journal of policy and practice [online]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/policing/advance-article/doi/10.1093/police/paaa024/5849182 [Accessed 20 August 2020].

- Boateng, F.D. 2019. Perceived police fairness: exploring the determinants of citizens’ perceptions of procedural fairness in Ghana. Policing and society [online]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10439463.2019.1632311 [Accessed 25 September 2020].

- Bottoms, A., and Tankebe, J., 2012. Beyond procedural justice: A dialogic approach to legitimacy in criminal justice. Journal of criminal law and criminology, 102 (1), 119–170.

- Bradford, B., and Quinton, P., 2014. Self-legitimacy, police culture, and support for democratic policing in an English constabulary. British journal of criminology, 54, 1023–1046.

- Chiu, C., 2013. Informal management, interactive performance: street vendors and police in a Taipei night market. International development planning review, 35 (4), 335–352.

- Daur, N. 2020. Quarantined Tableeghi Jamaat member stabs policeman to escape isolation centre. Naya Daur. Available from: https://nayadaur.tv/2020/03/quarantined-tableeghi-jamaat-member-stabs-policeman-to-escape-isolation-centre/ [Accessed 25 September 2020].

- Davis, D.E., 2017. Informality and state theory: some concluding remarks. Current sociology monograph, 65 (2), 315–324.

- Davis, D.E., 2018. Reflections on ‘the politics of informality’: what we know, how we got there, and where we might head next. Studies in comparative international development, 53, 365–378.

- Davis, J.M., 2020. Manipulating Africa? Perspectives on the experimental method in the study of African politics. African affairs, 119 (476), 452–467.

- Dawn. 2017. Women make up less than 2pc of the country’s police force: report. Dawn. Available from: https://www.dawn.com/news/1329292 [Accessed 24 September 2020].

- Hasan, S. 2020. Why are police in the Indian subcontinent humiliating quarantine violators? TRT World. Available from: https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/why-are-police-in-the-indian-subcontinent-humiliating-quarantine-violators-34911 [Accessed 24 September 2020].

- International Crisis Group. 2020. Pakistan’s COVID-19 crisis. Crisis Group Asia Briefing No. 162. 07 August 2020. Available from: https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-asia/pakistan/b162-pakistans-covid-19-crisis [Accessed 24 September 2020].

- Jauregui, B., 2013a. Provisional agency in India: Jugaad and the legitimation of corruption. American ethnologist, 41 (1), 76–91.

- Jauregui, B., 2013b. Beatings, beacons, and big men: police disempowerment and delegitimation in India. Law and social inquiry, 38 (3), 643–669.

- Jauregui, B., 2016. Provisional authority: police, order, and security in India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Jones, D.J., 2020. The potential impacts of pandemic policing on police legitimacy: Planning past the COVID-19 crisis. Policing: A journal of policy and practice, 14 (3), 579–586.

- Junaidi, I. 2020. Centre, Sindh at odds on lockdown; Punjab extends ‘shutdown’. Dawn. Available from: https://www.dawn.com/news/1543292 [Accessed 24 September 2020].

- Kokane, P.P., Maurya, P., and Muhammad, T. 2020. Understanding the incidence of Covid-19 among the police force in Maharashtra through a mixed approach. MedRxiv [online]. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.11.20125104v1 [Accessed 20 August 2020].

- Kyed, M., 2017. Inside the police stations in Maputo city: between legality and legitimacy. In: J Beek, et al., ed. Police in Africa: The street-level view. London: Hurst & Co., 213–230.

- Kyed, M., 2020. Provisional police authority in Maputo’s inner-city periphery. Society and space, 38 (3), 528–545.

- Laufs, J., and Waseem, Z. 2020. Policing in pandemics: A systematic review and best practices for police response to COVID-19. International journal of disaster risk reduction [online]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212420920313145 [Accessed 27 September 2020].

- Lipsky, M., 2010. Street level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. 30th anniversary expanded edition. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Marlow, S., Taylor, S., and Thompson, A., 2010. Informality and formality in medium-sized companies: Contestation and synchronization. British journal of management, 21, 954–966.

- Mubarak, S. 2020. Punjab police use stun gun therapy on SOP violators. Dawn. Available from: https://www.dawn.com/news/1561843 [Accessed 24 September 2020].

- The News. 2020. Clerics booked for inciting violence against female police officers acquitted. The News. Available from: https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/667002-clerics-booked-for-inciting-violence-against-female-police-officer-acquitted [Accessed 15 July 2020].

- Nisar, M., and Masood, A. 2019. Dealing with disgust: Street-level bureaucrats as agents of Kafkaesque bureaucracy. Organization [online]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1350508419883382 [Accessed 12 September 2020].

- Nolan, T. 2020. Militarization has fostered a policing culture that sets up protesters as ‘the enemy’. The Conversation. Available from: https://theconversation.com/militarization-has-fostered-a-policing-culture-that-sets-up-protesters-as-the-enemy-139727 [Accessed 25 September 2020].

- Pernegger, L. 2020. Effects of the state’s informal practices on organisational capability and social inclusion: Three cases of city governance in Johannesburg. Urban Studies [online]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0042098020910111 [Accessed 20 August 2020].

- Polese, A., 2015. Informality crusades: Why informal practices are stigmatized, fought and allowed in different contexts according to an apparently ununderstandable logic. Caucasus social science review, 2 (1), 1–26.

- Polese, A., Rekhviashvili, L., and Morris, J., 2016. Informal governance in urban spaces: Power, negotiation and resistance among Georgian street vendors. Geography research forum, 36, 15–32.

- Prabhu, J., and Jain, S., 2015. Innovation and entrepreneurship in India: understanding jugaad. Asia pacific journal of management, 32 (4), 843–868.

- Qureshi, Z. 2020. COVID-19: Police using shock device to punish violators of coronavirus preventive measures in Pakistan. Gulf News. Available from: https://gulfnews.com/world/asia/pakistan/covid-19-police-using-shock-device-to-punish-violators-of-coronavirus-preventive-measures-in-pakistan-1.71933319 [Accessed 24 September 2020].

- Ratcliffe, R. 2020. Teargas, beatings and bleach: the most extreme COVID-19 lockdown controls around the world. The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/apr/01/extreme-coronavirus-lockdown-controls-raise-fears-for-worlds-poorest [Accessed 26 September 2020].

- Roy, A., 2009. Why India cannot plan its cities: informality, insurgence and the idiom of urbanization. Planning theory, 8 (1), 76–87.

- Rubin, M., 2018. At the borderlands of informal practices of the state: Negotiability, porosity and exceptionality. The journal of development studies, 54 (12), 2227–2242.

- Sardan, J.O., 2015. Practical norms: informal regulations within public bureaucracies (in Africa and beyond). In: T. Herdt and J. O Sardan, ed. Real governance and practical norms in Sub-Saharan Africa. Routledge, 19–62.

- Stiegler, N., and Bouchard, J., 2020. South Africa: challenges and successes of the COVID-19 lockdown. Annales Medico-psychologiques, 178 (7), 695–698.

- Stogner, J., Miller, B.L., and McLean, K., 2020. Police stress, mental health, and resiliency during the COVID-19 pandemic. American journal of criminal justice, 45, 718–730.

- Stone, R. 2020. Covid-19 in South Asia: Mirror and Catalyst. Asian Affairs [online]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03068374.2020.1814078 [Accessed 20 September 2020].

- Swart, M. 2020. S Africa court issues orders to end police abuse during lockdown. Al Jazeera. Available from: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/05/17/s-africa-court-issues-orders-to-end-police-abuse-during-lockdown/ [Accessed 25 August 2020].

- Tankebe, J., 2019. In their own eyes: an empirical examination of police self-legitimacy. International journal of comparative and applied criminal justice, 43 (2), 99–116.

- Vigneswaran, D., and Hornberger, J., 2009. Beyond ‘good cop’/’bad cop’: understanding informality and police corruption in South Africa. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand.

- Waseem, Z. 2020. Covid-19 in South Asia: ‘Hard policing’ approach has left police ill-prepared to respond to a pandemic. Policing insight. Available from: https://policinginsight.com/features/analysis/covid-19-in-south-asia-hard-policing-approach-has-left-police-ill-prepared-to-respond-to-a-pandemic/ [Accessed 17 September 2020].

- Waseem, Z., and Rafiq, A. 2020. Coronavirus pandemic puts police in the spotlight in Pakistan. United States Institute of Peace [online]. Available from: https://www.usip.org/publications/2020/06/coronavirus-pandemic-puts-police-spotlight-pakistan [Accessed 27 September 2020].