ABSTRACT

Responding to domestic violence and abuse (DVA) poses significant challenges for the criminal justice system, with recent studies highlighting a number of significant gaps and failings in the nature of the police response in particular. This paper reports on findings from a component of the multi-stage ESRC funded project ‘Justice, Inequality and Gender-Based Violence’ (ESRC grant ES/M010090/1) that relates to 400 reported incidents of DVA involving intimate partners recorded by two police force areas in England in 2014. Drawing on this large data set concerning a wide range of incidents, this paper employs quantitative methods to analyse the trajectories of reports made to the police, and the factors that may influence their progress through, or attrition from the criminal justice system. In doing so, this paper finds that certain ‘inequality’ factors such as victim gender, vulnerability (including mental health) and incident type are found to impact the progression of cases through the criminal justice system. This work seeks to build on our understanding of what happens to incidents of DVA that are brought to the attention of the police by victims and survivors, and reflects upon how the outcomes of such incidents impact the broader debate concerning the pursuit of a formal, or criminal ‘justice’ in cases of DVA.

Introduction

Research exploring domestic violence and abuse (DVA) has expanded considerably over the past 30 years. Energised by a feminist movement integral in both establishing DVA as a legitimate subject of academic enquiry and in fostering more nuanced approaches to its study, DVA continues to be reconceptualised and revisited in terms of law, public discourse, and across a range of academic perspectives. In broad terms, our understanding of DVA has, as with other forms of gender-based violence (GBV), benefited significantly from the collective (and often collaborative) endeavours of academics, activists and victim services that have sought to highlight the extent of DVA and those cultural and systemic factors that precipitate it (Buzawa and Buzawa Citation2003, Robinson and Stroshine Citation2005). Such efforts have undoubtedly influenced the debate concerning responses to DVA, with the existing literature recognising its journey, in policy terms, towards a status as a public and social problem, rather than a private matter between individuals (Hester Citation2013). Inevitably so, such a transition has led to the expansion of formal sanctions for DVA and its associated offences through both civil and criminal law, though many concerns about suitability and efficacy of such measures, and whether such formal justice approach are inevitably detrimental, persist in both spheres (Hester et al. Citation2003, Burton Citation2009).

In England and Wales, DVA was during the period of the research defined by the government as

any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive or threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are or have been intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexuality. The abuse can encompass, but is not limited to: psychological; physical; sexual; financial; emotional. (HM Government Citation2013)

Police and criminal justice responses to DVA in England and Wales

According to the Crime Survey for England and Wales, it is estimated that each year, around 1.9 million adults aged 16–59 experience one or more incidents of DVA within a 12 month period. These figures (which in this case include family abuse, stalking and intimate partner violence) indicate a prevalence rate of roughly one in six adults (ONS Citation2018), but do not indicate levels of severity or whether the behaviour is ongoing. Available options for responding to DVA have diversified significantly in recent years. A legislative programme which has included the introduction of a victims commissioner,Footnote1 Domestic Violence Protection Orders,Footnote2 the Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme (or Clare’s law), and the creation of new offences under the Serious Crime Act 2015 sit alongside other initiatives such as the establishment of specialist domestic violence courts and the introduction of Independent Domestic Violence Advisors (IDVAs). In parallel, both Europe and America have seen the emergence of many variations of Domestic Violence Perpetrator Programmes (for example the Mirabel and DRIVE projects in England and Wales) that seek to change offender behaviour, though the impact of such schemes is still in contention (see Hamilton et al. Citation2013, Akoensi et al. Citation2013, Cannon et al. Citation2016, Walker et al. Citation2018, Hester Citation2019). Whilst a thorough review of these and other developments is beyond the scope of this paper, they serve to illustrate that the response to domestic violence has undergone a significant transformation over the past 30 years and that contemporary approaches go well beyond a reliance upon a ‘traditional’ criminal justice. Nonetheless, as the government’s 2016 update to its Ending Violence Against Women and Girls (EVAWG) strategy demonstrates, strengthening criminal justice approaches toward domestic violence offences remains a high priority and suggests that the general trend toward criminalisation (as evidenced by the new the Domestic Abuse Act 2020) that has been identifiable from the 1990s onward, will continue.

Whilst it is true to suggest that the increasing criminalisation of domestic violence provides a powerful and symbolic statement of condemnation (Stanko Citation1992) alongside fulfilling the fundamental retributive function, in reality delivering on the goals of criminal justice is profoundly complex. Supposing that the criminal justice system is equipped to deliver suitable outcomes for all that access it involves making assumptions about its processes and the nature of victimisation, particularly so in cases of DVA. Victims may not wish to engage with formal processes or institutions for a variety of reasons yet may be viewed in negative terms by those institutions as a result (Hanna Citation1996, Robinson and Stroshine Citation2004). Research exploring victim attitudes and feelings about the arrest and potential prosecution of their intimate partners reveals that understandably, many have misgivings about the criminal justice process and may engage with it not to secure the punishment of their abusers, but for other reasons such as the desire to save a relationship, to protect their children, or even to help the offender (Cretney and Davis Citation1997, Hester Citation2006). As a result, the institutional goals of criminal justice agencies that have been reaffirmed in an era of managerialism and the detailed scrutiny of their ‘performance data’ are often unaligned, or in some cases even at odds with the motivations and desires of at least some of those victims entering the system. Victims, cannot be uniformly expected to indulge the systemic expectations of a justice system focused simply on a linear ‘report to court’ approach, yet neither can the system simply fail those seeking precisely that route. The resultant dilemmas for policy and practice, plus long-standing concerns about the low conviction rates for domestic violence offences (see Hester Citation2006) and high rates of victim withdrawal (ONS Citation2017) have led some to question the real value of the justice system’s response. Hoyle and Sanders, who in 2000 began their discussion of the police response to domestic violence by simply asking ‘what is the point?’, concluded that meaningful criminal justice interventions needed to become more attentive to the needs of individual victims via an ‘empowerment approach’ that would place victim choice above the want of the system to obtain successful prosecutions (Hoyle and Sanders Citation2000, p. 33). Interestingly, Hester and Lilley (Citation2016), looking at rape, including domestic abuse rapes, found that a victim-focused approach is more likely to result in conviction. Current policy evidences a commitment to the compromise position of pursuing ‘evidence led prosecutions’ (i.e. prosecutions that proceed without the support of the involvement of the victim), though in practice the number of prosecutions that take this route are small (HMIC Citation2014a). The debate concerning quite what the purpose and aims of the criminal justice system should be in respect to domestic violence cases has enlivened the broader question about what ‘justice’ really means, and led some to explore what may be gained through alternative justice approaches such as community or restorative programmes (Hargovan Citation2005, Stubbs Citation2007, Westmarland et al. Citation2018) despite the wider view that such approaches are ‘not appropriate’ when applied to cases of domestic violence (HMIC Citation2014aa, p. 15). Moreover, our Justice, Inequality and GBV research found that victims were more likely to equate ‘justice’ with ‘empowerment’ than with criminal justice system outcomes.

With regard to policing specifically, the service in England and Wales has been under significant pressure to improve its response to domestic violence in the face of serious criticism stretching back to the 1990s. Home Office Circular 60/1990 established that the police needed to take a more ‘interventionist’ approach to domestic violence and treat those offences as they would other violent crimes, as well as identifying the need for officers to be more sympathetic towards victims. Further circulars 19/2000 and 9/2005 (which provided guidance on the Domestic Violence Crime and Victims Act 2004) emphasised in particular the need for proactive arrest policies to mirror those existing in the United States, although the value of such policies has been continually debated ever since. The response of the police has continued to evolve in recent years, with a particular emphasis on managing risk. Measures have included; enhanced collaboration with other agencies through MARAC (Multi Agency Risk Assessment Conference) proceedings and the use of apps and mobile phones equipped with TecSOS (Technical SOS) systems (Natarajan Citation2016).

Officers have a key role to play in responding to what are often highly complex incidents between intimate partners and have a range of vital and potentially conflicting considerations to manage when dealing with an incident. Engaging simultaneously with risk management, safeguarding, referrals to support services and making decisions regarding who gets arrested (and on what basis) is a daunting task that requires a high degree of skills and specialist training. However, in finding that the police response to domestic violence was simply ‘not good enough’ a 2014 HMIC inspection report found that in practice, many forces simply ‘lacked the skills and knowledge’ to respond to victims of domestic violence effectively, and that there existed a significant gap between policies on paper and work in practice (HMIC Citation2014a, p. 122). The 2014 report identified a wide range of weaknesses across the board from ineffective training, poor attitudes of officers, a lack of leadership and supervision, as well as specific investigative failings such as neglecting to collect evidence. Follow-up reports (HMIC Citation2015, HMICFRS Citation2017) found that although progress had been made on several fronts (including the training of officers), there remain causes for concern such as falling arrest rates, inconsistencies in assessing risk, the need for stronger case building, and a greater willingness to pursue victimless prosecutions. The report also highlighted the fact that there remains significant variation in the way that forces record domestic violence incidents and that the inefficient production and monitoring of data is a significant issue.

Against a backdrop of an austerity programme prompted by the 2010 spending review that imposed severe cuts on police resources, and significant increases in the reporting of domestic abuse and sexual offences (ONS Citation2017), it is clear that the police service are operating in challenging times; resources are scarcer yet expectations are becoming higher. Reports made to the police of crimes associated with DVA increased from 353,063 in the 12 months to 15 March, to 434,095 in the 12 months to June 2016, representing a 23% increase (HMICFRS Citation2017). Such pressure has resulted in a degradation of the victim experience in cases of DVA, with examples of bad practice highlighted by the HMICFRS reports. These included the downgrading of the severity of incidents reported by victims to justify slower response times, and the downgrading of victim risk assessments meaning that MARAC referrals were not required (HMICFRS Citation2017).

The attrition of DVA cases from the criminal justice system

Much of the reform concerning criminal justice responses to DVA has been targeted at reducing attrition and in particular the decreasing proportion of cases resulting in conviction. Instrumental in evidencing the extent of this gap as relates broadly to GBV, are attrition studies that examine the trajectories of reports made to the police and are able to evidence their progression through, or exit from, the formal criminal justice process. Whilst official data provide statistical insights into the number of incidents reported, arrest rates and outcomes (ONS Citation2017), such data is based on snapshots at one point in time, while more detailed academic studies may explore attrition in much finer detail with regard to individual cases over time. Such studies rely upon access to sizeable amounts of detailed police (and sometimes CPS, and Court) data that allows researchers to establish a number of patterns and observations about those criminal cases that come to the attention of the police, including information about victims and perpetrators, police and CPS decision-making, and criminal justice outcomes, such as victim withdrawal and conviction rates. Such work is known to be laborious and difficult given the dependency on the availability and accuracy of the data sources (see above discussion concerning gaps in criminal justice data), and cannot therefore be considered to produce ‘failsafe’ data about victimisation. Nevertheless, work of this kind that looks at exactly what happens to incidents reported to the police is vital in terms of assessing the quality and nature of the criminal justice response to DVA.

For cases to feature in the analysis, there is a need for them to have come to the attention of the police in the first instance and as a result such work cannot account for differences in reporting patterns on the grounds of gender, ethnicity or age. In addition, some specific challenges present themselves when conducting attrition studies that focus on cases of DVA. As Westmarland et al. (Citation2018, p. 2) point out, studying reports of DVA in this way relies upon police forces identifying or ‘flagging’ the incidents as such on their recording systems. Unlike the recordable offence of rape (or other crimes), DVA is in effect recorded via a broad range of criminal offences such as theft, criminal damage, or any of the offences against the person. It is only through flagging the incoming reports of various incidents as domestic violence/abuse related that the police may be able to join such incidents together, and in doing so overcome some of the serious inadequacies that result from treating incoming reports in isolation. In their consideration of the naming and defining of domestic violence, Kelly and Westmarland (Citation2016, p. 113) suggest that the emphasis on the ‘incidentalism’ of domestic violence misrepresents the experiences of victims and survivors whose experiences cannot be understood in terms of a series of discreet ‘incidents’ and that representing it in such a way both ‘skews’ the knowledge around domestic violence and undermines the efficacy of the response.

In light of the above, it is perhaps unsurprising that comprehensive attrition studies on DVA are few and far between. Testament to this is that Hester’s (Citation2006) study that examined the trajectories of 869 reports of intimate partner violence remains the most comprehensive study of its kind to date. In finding that only 31 of the individuals named as suspects in the 869 cases received convictions (4% of the total) and that only 4 of the cases resulted in a custodial sentence (0.5%), the study provided hard evidence for the gap between reporting and conviction and the role that certain factors play in criminal justice attrition. Of these, victim withdrawal (for various reasons) was found to be crucial, and that certain factors such as the victim and perpetrator having a child together influenced victim decision-making regarding the criminal justice process. Other studies have also highlighted that victim retraction or withdrawal is a critical issue for the progression of cases through the criminal justice system (Robinson and Cook Citation2006, Sleath and Smith Citation2017). Women’s decisions to retract or withdraw have been found to be influenced by a number of factors, including welfare concerns for themselves and their children, frustration or confusion regarding the court process, or a desire not to see the perpetrator face criminal justice sanctions (Bennett et al. Citation1999).

In recent years, research into DVA has been enriched by work that has sought to address significant gaps in our understanding of various group’s experiences of victimisation, including those in same-sex relationships (Donovan and Hester Citation2014), women from BME backgrounds (Banga and Gill Citation2008, Gill and Harrison Citation2016), older women (Womens Aid Citation2007), and men (Hester et al. Citation2015). So too, has the literature taken account of the impact of DVA on victims and how it may contribute to mental health issues, drug and alcohol abuse (NICE Citation2014). Though it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss either these, or the broad range of intersectional works in the area, it should be noted that in the specific context of attrition research, relatively little is known about how such inequalities and related vulnerabilities influence criminal justice outcomes following a report to police. The current study sought to explore these issues as part of a wide-ranging study examining the attrition process as it relates to reported incidents of DVA.

Methodology

In October 2015, the research team received Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) funding to undertake the ‘Justice, Inequality and Gender Based Violence’ project (referred to hereafter as ‘the justice project’), a component of which involved the collection and analysis of new police data concerning reported incidents of DVA between intimate partners. In line with the broader research aims of the justice project, the current study was undertaken with a view to answering two specific research questions: ‘how do victims (of DVA) experience justice'? and ‘How does inequality affect access to support pathways and trajectories through the formal justice system’. In addressing these questions, the research team secured access to police data relating to 400 intimate partner DVA incidents flagged as ‘domestic violence’ in two force areas in England.Footnote3 In order to facilitate a quantitative analysis of the police data, a coding framework was developed into which key characteristics could be captured by the research team (building on Hester Citation2006, which also focused on intimate partner DVA). These included (but were not restricted to) victim and perpetrator characteristics, incident details, police actions, nature of evidence, and point of exit from the criminal justice process as well as ‘flags’ identifying particular concerns such as presence of weapons. Each of the 400 incidents was accessed, read by the research team and coded into the framework on-site with care taken to ensure the anonymity of the involved parties. Once coded, the data was extracted and analysed on university premises via the statistical software packages Excel, and SPSS. The sample was comprised of incidents that had taken place in either the months of May or November 2014, that were considered to have been concluded in investigative terms, and in line with the government definition, only concerned victims aged 16 and over. The use of May and November as sampling frame builds on previous work on police data by the team and provide ‘average’ data in the sense of numbers of DVA reports.

Using police data to establish and analyse case progression is valuable in providing individual-level trajectories, though the approach is not without limitations. Whilst data held by police systems is potentially rich in detail, researchers accessing such data are ultimately dependent on records being both complete and accurate. Individual officers may record events in different ways and it must be accepted that a retrospective interpretation of ‘the record’ may sometimes not represent the full picture of either an incident, or the investigative response (Burton et al. Citation2012). It should also be emphasised that the data entered into police records is created by officers themselves and as a result may be influenced by an individual officer’s assessment of evidence and other case features; it is not necessarily reflective of an absolute ‘truth’. Furthermore, it must be accepted that it will not always be possible for the police to ascertain certain case features or victim attributes, such as the presence of a mental health issue or whether weapons were involved. Such issues may not be obvious, and remain undisclosed to officers, particularly in cases that fall away quickly through retraction or withdrawal where officers have less contact with the parties involved. Such limitations are a feature of all works that rely on the analysis of data originating in police recording systems and should be kept in view when interpreting the data.

Terminology

This paper uses the terminology of ‘victim’ and ‘perpetrator’, though recognises that a number of other terms may also be appropriate (survivor, injured party, complainant, suspect, etc.). In doing so, we accept that those involved may self-identify with some, or none of these terms. In the case of DVA, it is also the case that some of those identified as ‘victims’ in some incidents will be identified by the police as ‘perpetrators’ in others. In these cases, we have been led by how the individuals have been entered into the police record. It should also be stated that all references to ‘perpetrators’ are in essence alleged perpetrators, just as victims are alleged victims. We have previously looked at how such ‘dual’ identification as both victim and perpetrator may mask primary perpetration (Hester Citation2013), and applied a more simplified longitudinal approach in the current work looking at the history of previous incidents and arrests to identify possible primary perpetrators.

Reference has also been made to the presence or identification of a ‘mental health issue’ (MHI) on the part of either victims or perpetrators. The identification of this attribute was made by the research team on the basis of it being either ‘flagged’ explicitly in the police record, or derived from the case files. We recognise that the terminology of MHI is broad, and may relate to a wide range of mental health conditions that vary in severity, and may have impacted the incident and investigation in different ways. Similarly, reference is made to victims being identified as ‘vulnerable’ by the research team. What constitutes ‘vulnerability’ is subject to much debate within the scholarly literature, for instance Stanko and Williams (Citation2009, p. 214) describe vulnerability as ‘being exposed to attack or harm, physically or emotionally’. In our research, the focus was on impacts of inequalities and the research team attached a vulnerability marker to any victim identified with: a physical disability, learning difficulties, a criminal record, being pregnant, being homeless or experiencing issues with housing, alcohol or drug issues (including dependency), self-harm, or other mental health issue. In undertaking these assessments, the research team identified far greater numbers of vulnerable victims in the case files than were formally recognised by the police system through the application of a vulnerability ‘flag’. The police flagging system identified just 14.2% of victims (n = 57) in the sample as vulnerable, whereas the research team’s analysis of the wider case materials led to almost half of the sample (48.2% n = 193) meeting the vulnerability criteria stipulated above.

For some victims, it was possible to identify more than one vulnerability. As with MHI, we accept that these factors vary in severity and impact upon individuals, incidents and investigations in different ways, and that a thorough appreciation of the impact of these factors is difficult to discern from the police record.

Once coded, the data was subject to analysis via frequency tables and crosstabs to establish sample features such as the demographics of the parties involved, as well as case type and progression through the criminal justice system. Further, binary regression analyses were used to examine the association between victim vulnerabilities and case outcomes such as victim withdrawal or a police ‘NFA’.

The undertaking of this research was subject to data protection agreements with the constabularies involved, and approved by the relevant university ethics committee.

Findings

An exploratory analysis of the 400 case files flagged as ‘domestic violence’ was conducted to reveal sample features and factors associated with case trajectories and attrition from the criminal justice system. Subsequently, sub-groups were identified and analysed to facilitate a greater understanding of attrition patterns of particular types of incident within the sample. These included looking at incidents only involving female victims, incidents involving only male victims, incidents involving victims identified as having a mental health issue (MHI), those identified as ‘vulnerable’ by the research team, and incidents involving parties with children. These groups provided large enough sub-samples to facilitate more detailed analysis in these areas.

Sample characteristics

Substantially more incidents concerned a female victim than a male victim (80.5% vs. 19.5%). Given the sampling criteria of assessing only those incidents between intimate partners, the parties knew each other in all cases, though the sample featured more incidents between ex-partners than those considered currently in relationships at the time of report (50.6% vs. 43.6%). The vast majority of incidents reported were between heterosexual current or former partners, with same-sex relationships accounting for only 1.5% of the sample (n = 6). Children were a feature of the incidents reported, with 52% of cases involving children living in the house at the time of the incident. Where information was known,Footnote4 56% of incidents reported were between couples who had children together, and in 37.5% of these cases, the research team were able to establish that there were ongoing child contact issues between the parties. In terms of victim age, nearly a third of the sample (29.4%) featured incidents involving those under the age of 25, with the next largest group being those aged between 31 and 40 (27.1%). The youngest victim was aged 16 (n = 1) and the oldest was aged 80 (n = 1), though it emerged that there were very few incidents reported by those over the age of 65 (n = 4). The majority of incidents reported concerned victims identified as ‘white’,Footnote5 though for incidents in force 2, the majority of ethnicity codes (75%) were not populated by police systems and were thus entered as ‘no information’ within the coding framework. This meant that in total, only 15 incidents in the total sample were able to be identified as having been reported by a victim with a Black and minority ethnic group (BME) identity. Notably, the sample contained a relatively high proportion of victims who were identified as having a pre-existing criminal record (20.8%). As illustrates, a range of victim vulnerabilities were captured by police flags or narrative information in the case files, of which almost a quarter identified as having a mental health issue (24.8%). Female victims were significantly more likely to be recorded in the case file as having an MHI than male victims (27.6% vs. 12.8%, P < 0.01), and of all victims identified with MHI, 89% were female. MHI’s were also identified in the police record for perpetrators, where similar proportions were found for both male and female perpetrators (21.3% and 21.7%, respectively). It also emerged that 39% of accused perpetrators in cases with victim MHI had been previously arrested for other DVA incidents, compared to 27.3% for the total sample.

Table 1. Victim demographics and vulnerabilities.

A range of incidents were reported to the police, not all of them crossing the threshold into recorded criminal incidents (see discussion of attrition that follows). 69% (n = 276) of incidents were reported by the victims themselves, with the remainder reported by third parties, statutory agencies, or in a small number of cases (n = 7) self-referrals by the perpetrator. A breakdown of incident classification is detailed in , which evidences that incidents classed as verbal arguments made up the largest proportion of incident type, and unlikely to be deemed criminal offences at the time. Male victims were more likely to report incidents relating to the damage of property, and female victims more likely to report incidents relating to harassment, stalking and malicious communications. In terms of perpetration, a number of key differences relating to gender were observed. Unsurprisingly, given the demographic information on victimisation, most of the perpetrators in the sample were male (80%, n = 321), with

Table 2. Nature of incidents reported.

20% of perpetrators identified as female. Male perpetrators were significantly more likely to have had previous DVA incidents with other partners than their female counterparts (P < 0.05) i.e. were likely serial perpetrators, male perpetrators were more likely to have had previous arrests for DV than female perpetrators (P < 0.05) indicating the violent nature of the abuse, and more likely to have had charges brought against them previously (P < 0.05). Furthermore, just over half (51%, n = 39) of male victims were named as perpetrators in other incidents involving the parties in the sample incident, and in most (62%) of these cases, the male was named as a perpetrator in most, or all of the other DVA incidents thus indicating that the men were the likely primary perpetrators. Furthermore, all perpetrators in the sample who had previous convictions for DVA offences were identified as male.

Regarding the previous experience of abuse within their relationships, and reflecting the general pattern above, 65% of the victims in the total sample had been a victim of some form of domestic violence with the same perpetrator, with more female victims reporting such repeat victimisation than male victims (68% vs. 53%). Also, female victims were more likely to have experienced incidents of DVA with other previous partners than male victims (30.4% vs. 16.7%). Of the ten victims identified as experiencing either homelessness or housing issues, 9 of them had previously reported being a victim of DVA with the sample perpetrator. Of those reporting previous DVA in their relationship, 66.6% of victims reported between one and four previous incidents between the sample parties, though many victims reported more extensive histories of DVA, with one victim reporting a total of 57 previous incidents. Female victims experienced more incidents than male victims, with 89.5 of the female victims compared to only 10.5% of the male victims experiencing more than five incidents from the same partner. In 46% of total sample cases, the research team were able to identify that there were also incidents subsequent to the sample incident that resulted in a report to the police.

Attrition and case trajectories

Of the 400 incidents reported, the majority were not recorded as crimes by the police. In total, 36% of incidents (n = 145) were recorded as crimes. In 85% (n = 123) of crimed cases, an arrest was made (31% of all incidents) and 40% of incidents where an arrest was made resulted in charges being brought (12%, n = 48) of all reported incidents. 60% of charged cases resulted in a conviction (7.25% of all reported incidents) but only a small number (n = 3) of the reported incidents resulted in a custodial sentence for the offender (0.8% of all reports, 10% of all convictions). Some differences were noted in rates of progression according to both victim characteristics (see below), and incident type. While incidents with male victims were marginally more likely to result in conviction overall (8% vs. 7%) incidents with a male victim were less likely to result in an arrest of a suspect than cases involving a female victim (22% vs. 31%), and less likely to result in a charge (9% vs. 13%). Moreover incidents between those who had children had lower conviction rates than those who did not have children together (4.5% vs. 9.4%). As evidences, police records show that victim withdrawal from the criminal justice process was a significant factor in case attrition, with withdrawal occurring in 52.4% of crimed cases, and almost all withdrawals (92.4%) occurring at the pre-charge stage. Though the reason for victim withdrawal was not always apparent in the case files, victim/case attributes had an influence over the withdrawal rate. Withdrawal rates were significantly higher for victims identified as vulnerable as opposed to those who were not (64% vs. 39%, P < 0.05), and for victims identified as having ‘problems with alcohol’, the rate of withdrawal was 75%. Victim withdrawal was also implicated in police decisions to take ‘no further action’ (NFA), with retractions or a decision not to support investigations cited as the main reason for such a decision in 49% of cases that resulted in an NFA.Footnote6

Table 3. Case progression and victim characteristics/case type.

Victims with mental health issues and vulnerabilities

Incidents involving victims identified as having a MHI were significantly more likely to have been crimed by the police than cases where no such issue was identified (46% vs. 33%, P < 0.05), and more likely to result in an arrest of a suspect (40% vs. 28%, P < 0.05). Such cases were also significantly more likely to have been referred to the CPS for a charging decision, with referrals occurring in 20% of all reported incidents vs. 12% of cases where no victim MHI was identified (P < 0.05). However, at the later stages of the criminal justice process, rates of charge, and conviction were lower for these incidents than where no MHI was identified on the part of the victim. Victims identified as ‘vulnerable’ by the research team (using the broader criteria specified above in methodology) also had lower rates of charge and conviction than those who were not identified with vulnerabilities. Within this particular group of cases (n = 193) it was observed that nearly three quarters (73%, n = 142) were repeat victims of abuse.

Binary logistic regression analyses were performed to ascertain the effects of victim’s gender, vulnerability, mental health, whether the victim has children from the perpetrator, and alcohol/drug issues (combined) on police decision to take no further action (n = 67 out 399 or 16.8%) and victim withdrawal for crimed cases only (n = 76 out 145 or 52.4%). Victims with any vulnerabilities listed had more than twice the odds of police decision to take no further action and victim’s decision to withdrawal (see and ). Binary regression analysis revealed that an identification of vulnerability was a statistically significant predictor of both a police decision to take no further action (twice the odds, P = 0.022) and victim withdrawal (more than twice the odds, P = 0.044).

Table 4. Binary logistic analysis – policy decision to take no further action (all cases, n = 399).

Table 5. Binary logistic analysis – victim decision to withdrawal (crimed cases only, n = 145).

Incidents involving physical violence

80% (n = 70/88) of reported incidents that involved the use of physical violence involved a female victim. In addition to these, the total sample also included 5 reports of rape made against female victims.Footnote7 In terms of incident type, there were stark differences in the trajectories of incidents that involved physical violence and those that did not. Reflecting the criminal offences available, reported incidents of physical violence being used were significantly more likely to be crimed (P < 0.01), arrested (P < 0.01), and charged (P < 0.01), than incidents that involved verbal abuse. Of 140 reports of incidents involving verbal abuse (i.e, where physical violence was not reported as a feature), 2 resulted in a charging decision from the CPS. The gender profile of victims involved in both violent, and ‘verbal only’ incidents reflected the profile in the total sample, with female victims accounting for around 80% of reports in both groups. There were no convictions of any kind following the report of an incident involving only verbal abuse in this sample (i.e. where physical violence was not a feature of the incident). Of the incidents involving physical violence, most (86%) were crimed, and resulted in an arrest (69%). In this group, cases involving a female victim were significantly more likely to result in an arrest than those involving a male victim (P < 0.05). In cases involving physical violence, referrals to some source of victim support were more likely to be made than those involving verbal abuse only (40% vs. 26%, P < 0.05). The impact of referral is discussed further in relation to the broader sample below.

Referral to support

Analysis of the case files demonstrated that in addition to conducting investigations, police made referrals to various sources of victim support (beyond that offered by responding and investigating officers themselves) in 31% (n = 116) of cases. These included referrals to both generic and specialist victim support services, social services and health agencies. Incidents in which the victim was referred to /supported by a specialist domestic violence advocate (either via Victim Support, from an IDVA, or another specialist DV agency), were significantly more likely to be crimed (48% compared with 32% without such support, P < 0.01), and there was significantly more likely to be an arrest made (44% compared with 25% without such support, significant at p < 0.01). These cases were slightly more likely to have a charge brought in the case (13% compared with 10% for those without specialist DV advocacy support), and for there to be a conviction (11% compared with 6%).

Discussion

DVA and attrition

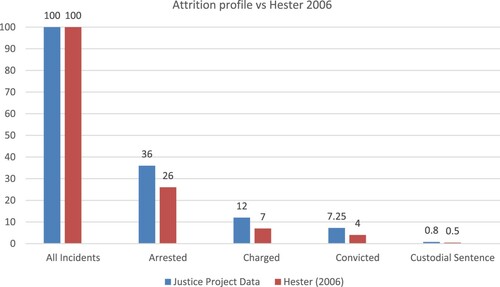

The data generated from the case file analysis allows the opportunity to explore some critical features of the attrition process as relates to those incidents of DVA that are reported to the police. The overall attrition rate (from report to conviction) evidences that only a small proportion of all cases reported resulted in a criminal conviction of some kind (7.25%), and that only a very small number of the reports resulted in custodial sentences for the perpetrator (0.5%). The attrition profile generated from the total sample, also establishes that most of the reports made to the police are dropping out at the front end of the process. Only around a third (36.3%) of what were logged on police systems as ‘incidents’ crossed the threshold to ‘crimed’ status, and that by the arrest stage, 64% of incidents had dropped out of the formal criminal justice process. The collection of the new data allows us to draw comparisons between the attrition patterns found in the justice project, and those established in earlier studies of attrition in DVA cases (Hester Citation2006). These are outlined in , below.

Figure 1. Attrition profile for justice project data vs. Hester (Citation2006).

As the data shows, the broad pattern of progression through the criminal justice system is similar for both studies, though there is some evidence to suggest that in some areas, the system was by the time of the current study more effective than it used to be, with higher rates of arrest ( + 10%), charge, ( + 5%) and conviction ( + 3.25%) found in the justice project data. On the one hand, this suggests that efforts to enhance various elements of the formal response in the intervening period between these studies (see review, above) resulted in some gain. For instance, increased rates of arrest may indicate a greater willingness on the part of the police to respond proactively and secure the safety of victims, whilst an increase in the overall conviction rate may suggest an increased likelihood of a formal justice sanction at the end of the process. However, there are grounds to be cautious in any appraisal of the advances made, not least because (perhaps with the exception of arrest) the current study provides us with only a picture of incremental progress rather than significant change. Indeed, many of the issues found to contribute to attrition in previous work are once more echoed in the current study findings, including high rates of victim withdrawal (52.4% of crimed cases). It remains the case that the majority of cases drop out before an arrest is made (roughly two-thirds) and that the prospect of a custodial sentence is remote from the outset. On this basis, it would seem that some of the serious barriers to achieving the ‘end goal’ of the formal justice process (i.e, a conviction) remain firmly in place if that is indeed what victims want.

The finding that only 36% of the crime reports in the sample result in an official record of a crime is conspicuous when contrasted with other crimes such as rape, where recent work has found that up to 86% of incidents are crimed (Walker et al. Citation2019). Of course, whilst it is difficult to compare the criming rates of rape, a distinct offence, to a collection of offences under the broader DVA umbrella, the low figure reported in this study still gives some food for thought. Our previous work provides an indication that victims of intimate partner DVA are less likely to want a conviction of the perpetrator than victims in cases of rape, although further work is needed in this area (Hester Citation2006, Hester and Lilley Citation2018). In finding the police to be inadequate in their recording practices, HMICFRS (Citation2018a.) found that many incidents tagged as ‘domestic abuse’, including a significant number of violent offences, had not been recorded and remained on police systems only as ‘non-crime incidents’. The HMICFRS report suggested that non-recording carried significant consequences for victims of DVA in that these ‘non-crime incidents’ were less likely to have been investigated fully, and that those involved were less likely to have been the subject of appropriate safeguarding. Whilst on the one hand, it is understandable that support resources may be focused around those events that become officially recognised as ‘crimes’, the consequence is that those involved in incidents that do not cross this threshold (including those that do not because of police recording errors) are less likely to be referred to sources of support. This is an important issue that raises questions about how particular kinds of report may be more likely to result in ‘crimed’ status than others.

On this front, the findings suggest that the police are far more likely to record criminal offences, make support referrals and undertake arrests in cases involving physical violence. It may be understandable to see why these incidents may be considered more ‘serious’ than those without physical violence, as there are possibly recognisable offences attached (such as those associated with the Violence Against the Person Act), but the vast difference in the criming rate (86% vs. 5%)and arrest rate (69% vs. 6%) between cases involving physical violence and those which were verbal in nature suggests that, at least in the period prior to the new criminal offence of coercive control, responses to a report of DVA were still largely driven by the presence or absence of physical violence, and thus reflected that broader patterns of abuse, control or coercion that may be established by verbal abuse stood far less chance of being identified and processed through the formal system. The data collection window for this study preceded the creation of the controlling or coercive behaviour offence, which provides the police with a more secure legal basis to criminalise and prosecute ‘verbal’ (or non ‘violent’) forms of abuse. However, our finding that of 140 incidents of verbal abuse, only two resulted in charges (neither resulting in conviction) underlines the extent of the cultural shift that may be required in terms of the investigation and prosecution of coercive or controlling behaviour which may not always include evidence of physical assault. These cases are doubtless challenging because they require a move away from a traditional ‘incident focused’ police approach to investigation to one that takes a broader view of abusive and controlling behaviour over time and across a constellation of related incidents. Recent data (ONS Citation2018) suggests that although the police service are becoming more skilled in recognising the new coercive control offence, (with recorded incidents doubling from 4246 in 2016–2017 to 9052 in 2017–2018) the vast majority of cases that result in arrest are dropped prior to charge (BBC Citation2018, Brennan & Myhill Citation2021). In our research, it would seem that when tasked with responding to an allegation of verbal abuse in 2014, the criminal justice system was largely unable to record a criminal event, let alone pursue a viable prosecution. It follows that reports of verbal abuse, being proportionally the largest report type in this study (35% of total), had a suppressing effect upon the overall measures of arrest, charge and conviction and stood the least chance of progressing through the criminal justice system.

The impact of gender

The sample characteristics support the already extensive evidence that the vast majority of victims reporting to the police in DVA cases are female (ONS Citation2017, Citation2018), with 80.5% of victims in the study identified as such. Differences were observed between cases reported by males and females with cases involving a male victim having a somewhat lower arrest and charge rates than those cases involving female victims, although there were similar rates of conviction. This may in part be explained by the differing profile of offences experienced by these two groups (see ), but also by issues concerning the gendered dynamics between the parties. Female victims were more likely to have experienced unidirectional DVA in the context of their relationships with male perpetrators (in that they were only ever categorised as a victim and not a perpetrator), whereas male victims were often named as perpetrators in other incidents between the parties. It is possible that this may have affected decision-making around the potential arrest of female ‘perpetrators’ who, were known by the police as ‘victims’ in other reported incidents and the wider context of their relationships. The context in which allegations and counter allegations are made is crucial given that an ‘incident focused’ crime recording system may fail to recognise the broader direction of travel in terms of DVA perpetration and thus to identify primary perpetrators (Hester Citation2013). The evidence on number of incidents and types of DVA suggest that women experienced higher levels of repeat victimisation and probably severity of DVA. However, although women made up the overwhelming majority of victims in all offence categories, there were few differences in overall conviction rates between cases involving male and female victims (7% vs. 8%). It was also observed that those cases where the victim and perpetrator had children together exhibited greater levels of attrition at the arrest, charge and court stage, with the conviction rate in those cases being half (4.5%) that in cases where the parties involved did not have children (9.4%). This echoes the previous research which suggested that such cases carry particular complexities and challenges such as high withdrawal rates and leniency at the court stage due to mothers not wanting their children to lose fathers, or defence lawyers using child contact arrangements as a means of pushing for lower sentences (Hester Citation2006).

Important differences were identified in the trajectories of cases involving victims identified with vulnerabilities. Whilst such cases were more likely to be crimed, and to result in an arrest than cases where no victim vulnerability was identified, thus suggesting that the police saw them as ‘serious’, such cases were characterised by higher rates of victim withdrawal and police decisions to take ‘no further action’, with regression analysis showing vulnerability to be a predictor of both such outcomes. It has been acknowledged that responding effectively to vulnerability is a vital function for the state and its institutions (Fineman Citation2008). Though the extent and nature of interventions made in this context risk being considered ‘paternalistic’ or ‘coercive’ (Mackenzie et al. Citation2014, p. 2), typically, criminal justice systems tend to frame vulnerability in such a way that suggests extra preventative measures, investigative strategies and even criminal justice outcomes need to be utilised and pursued in the goal of protecting vulnerable persons, and it must be remembered that such considerations are explicitly stated via current state authored strategies to combat GBV (see earlier review). Moreover, research has indicated that victims, and women in particular, may withdraw if they do not consider the system to create safety for them and if criminalising the perpetrator may encourage further abuse. Thus, the current study findings give some cause for concern, for even if the victimisation of vulnerable victims should come to light, and subsequently be investigated; high withdrawal rates prevent the justice process reaching its latter stages and may indicate concerns about revictimisation. Other studies that have also explored the link between victim vulnerability and case progression in rape investigations have returned similar findings (Hester and Lilley Citation2016, Rumney et al. Citation2019). In the current study, cases involving victims identified with mental health issues were significantly more likely to be crimed and result in the arrest of a perpetrator, though they were still found to have lower conviction rates, and higher withdrawal rates. Previous research has suggested that for victims of DVA, engagement with the criminal justice process can cause, as well as exacerbate existing mental health issues (Herman Citation2003, Douglas Citation2018). The current study findings show that following an initial report, most victims with an MHI (60%) withdrew from the formal justice process at an early stage, but also that those victims with MHI reaching the courts may perhaps not be deemed ‘robust’ or ‘credible’ witnesses.

Identifying inequalities in police data: gaps and challenges

Very few incidents in the sample related to same-sex couples (n = 6, 1.5%), making it impossible to produce a detailed analysis of the progression of such cases through the justice system. This is despite studies suggesting that prevalence rates for DVA in same-sex relationships are similar or even slightly greater than those for heterosexual relationships (Stiles-Shields and Carroll Citation2015). The low numbers of such reports may support the view that those from the LGBTQ+ community face more barriers in reporting to the police (Donovan and Hester Citation2014, Guadalupe-Diaz Citation2016). Furthermore, in collecting the police data, it soon became apparent that information on victim ethnicity was not generally available; in one of the two force areas it was largely absent. Of the 400 incidents of reported DVA, only 15 of these were able to be identified as relating to a BME victim, and as a result it was not possible to subject these cases to a rigorous statistical analysis. That information on the ethnicity of victims of DVA is not readily held on police recording systems is a cause for concern, not least because their experiences are not accounted for in the current study. BME victims of domestic violence may benefit from support services that are sensitive to their particular needs (Clinks Citation2016, Safer London Citation2016) and failing to record ethnicity data accurately may impede the police service in making direct referrals and developing meaningful relationships with these organisations where they exist. There were other critical areas where it seemed police mechanisms for capturing important information were lacking. In a recent HMICFRS review, it was reported that:

It is regrettable that … . forces continue to define a vulnerable victim in different ways and record vulnerability inconsistently across the country. (HMICFRS 2018, p. 71)

Reflecting on CJS ‘performance’ and the pursuit of formal justice

Attrition studies place an emphasis on using traditional performance indicators such as rates of arrest, charge and conviction to gain an understanding of case trajectories and pathways through the formal system. This of course, is the approach taken in this work. In finding that only a very small proportion of reports make it to the court stage, it would be tempting to conclude that the high rates of attrition represent a complete ‘system failure’ in respect of its obligations to victims, though such a conclusion would be overly simplistic. Although there are many elements of the formal approach that require improvement, as other studies have also suggested, in the current study, many reports of DVA were unable to progress as a result of an early withdrawal. Victim withdrawal is a conspicuous feature across all case types in this study, as is so in other works examining DVA attrition. These studies have found that more than half of victims reporting domestic violence to the police do not have the intention to press charges (Boivin and Leclerc Citation2016), and that many victims withdraw from the CJS having achieved what end was sought through report or arrest only (Hoyle and Sanders Citation2000, p. 23). It is for these (and other) reasons that some have argued against using withdrawal rates as a measure of criminal justice performance (Robinson and Cook Citation2006, p. 208). Furthermore, it has been pointed out that there are dangers in prioritising the exercise of ‘inspiring confidence’ in the CJS (for instance, via an obsession with boosting performance data) ahead of a broader consideration of victim needs (Walklate Citation2008, p. 43). From the perspective of a victim, a withdrawal may in some cases be the best way to secure their own safety (Hirschel and Hutchinson Citation2003). As such issues illustrate, the complexities of intimate-partner violence are profound and any assessment of performance data must avoid making assumptions about ‘what is best’ in every instance. As Robinson and Cook (Citation2006, p. 209) suggest, it is important to treat victims as ‘people, not cases, and take account of the complex realities of their daily lives’. This is important to remember when considering quantitative studies of attrition and CJS performance. That said, whether through choice or coercion, it would appear that for many, pursuing ‘justice’ outcomes in the formal arena is difficult to reconcile with their needs. In light of this, it would seem that further development of more holistic approaches to DVA that facilitate alternative forms of seeking ‘justice’, such as those in community or restorative settings are at least as important as those strategies aimed at improving the response of the CJS.

Conclusion

DVA remains a high profile, and high priority issue for the current government. This paper provides new evidence on the extent of attrition in reported incidents of DVA in England, demonstrating that the likelihood of conviction at the end of the criminal justice process is low, and that certain case characteristics such as victim vulnerability, whether the parties involved have children together, and the absence of physical violence can reduce these prospects further. It suggests that the experience of seeking ‘formal’ justice is dependent on both case type and victim characteristics, and that there are significant challenges in progressing a report of DVA through the system. At a time when strategies for combating DVA are being examined via the introduction of the Domestic Abuse Act (2020), it would seem that the evidence on attrition presented here is a timely reminder of the challenges of pursuing formal justice in the aftermath of DVA.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Domestic Violence Crime and Victims Act 2004.

2 Crime and Security Act 2010.

3 Though this flag also generated incidents of familial abuse, only cases between intimate partners were considered for this analysis.

4 Information regarding whether the involved parties had children together available in 312/400 case files.

5 In this instance ‘white’ is presented in its widest application and includes ‘white British’, ‘white Irish’ and ‘any other white background’.

6 In analysing the cases files it was often difficult to distinguish between a decision to classify an incident as NFA, and victim withdrawal as an incident outcome. Generally, the quality of information concerning the NFA outcome code was less consistent than the ability to identify a victim withdrawal from the police record.

7 It is important to recognise that this figure is likely to be a gross underestimate of rape in DVA cases given that the sampling criteria for this research was dependent on a ‘DVA’ flag, rather than a ‘Rape’ flag on police coding systems. See Hester and Lilley (Citation2016) Rape investigation and attrition in acquaintance, domestic violence and historical rape cases. J. of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 1–14.

8 Where information known.

9 Withdrawal rate data for cases crimed by police

References

- Akoensi, T.D., et al., 2013. Domestic violence perpetrator programs in Europe, part II: a systematic review of the state of evidence. International journal of offender therapy and comparative criminology, 57 (10), 1206–1225.

- Banga, B. and Gill, A., 2008. Supporting survivors and securing access to housing for black minority ethnic and refugee women experiencing domestic violence in the UK. Housing, care and support, 11 (3), 13–24.

- Barnish, M. 2004. Domestic violence: a literature review. HM Inspectorate of Probation. Available from: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/www.justice.gov.uk/inspectorates/hmi-probation/docs/thematic-dv-literaturereview-rps.pdf [Accessed 17.10.19].

- BBC News. 2018. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-46429520 [Accessed 17.10.19].

- Bennett, L., Goodman, L., and Dutton, M.A., 1999. Systemic obstacles to the criminal prosecution of a battering partner: A victim perspective. Journal of interpersonal violence, 14 (7), 761–772.

- Boivin, R., and Leclerc, C., 2016. Domestic violence reported to the police: correlates of victims’ reporting behavior and support to legal proceedings. Violence and victims, 31 (3), 402–415.

- Brennan, I., and Myhill, A., 2021. Coercive Control: Patterns in Crimes Arrests and Outcomes For a New Domestic Abuse Offence. British Journal of Criminology. azab072

- Burton, M., 2009. Civil Law remedies for domestic violence: Why are applications for non-molestation orders declining? The Journal of social welfare & family law, 31 (2), 109–120.

- Burton, M., et al. 2012. Understanding the progression of serious cases through the criminal justice system: evidence drawn from a selection of casefiles. Ministry of Justice Research Series 11/12.

- Buzawa, E.S., and Buzawa, C.G., 2003. Domestic violence: the changing criminal justice response. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cannon, C., et al., 2016. A survey of domestic violence perpetrator programs in the United States and Canada: findings and implications for policy and intervention. Partner abuse, 7 (3), 226–276.

- Clinks. 2016. Angelou Centre: supporting BAME victims of domestic abuse and sexual violence: a case study of a voluntary sector organisation in the North East. Available from: https://www.clinks.org/sites/default/files/2018-09/angelou_case_study_final_090316.pdf [Accessed 17.10.19].

- Cretney, A., and Davis, G., 1997. Prosecuting domestic assault: victims failing courts, or courts failing victims? The Howard Journal of criminal justice, 36 (2), 146–157.

- Crisp, D., and Stanko, B., 2001. Monitoring costs and evaluating needs. In: J. Taylor-Browne, ed. What works in reducing domestic violence? A comprehensive guide for professionals. London: Whiting & Birch, 211–226.

- Donovan, C., and Hester, M., 2014. Domestic violence and sexuality: what's love got to do with it? Bristol: Policy Press.

- Douglas, H., 2018. Domestic and family violence, mental health and well-being, and legal engagement. Psychiatry, psychology and law, 25 (3), 341–356.

- Fineman, M.A., 2008. The vulnerable subject: anchoring equality in the human condition. Yale Journal of Law and Feminism, 20 (1), 1–24.

- Gill, A.K., and Harrison, K., 2016. Police responses to intimate partner sexual violence in south Asian communities. Policing, 10 (4), 446–455.

- Guadalupe-Diaz, X., 2016. Disclosure of same-sex intimate partner violence to police among lesbians, gays, and bisexuals. Social currents, 3 (2), 160–171.

- Hamilton, L., Koehler, J.A., and Lösel, F.A., 2013. Domestic violence perpetrator programs in Europe, part I: a survey of current practice. International Journal of offender therapy and comparative criminology, 57 (10), 1189–1205.

- Hanna, C., 1996. No right to choose: mandated victim participation in domestic violence prosecutions. Harvard law review, 109 (8), 1849–1910.

- Hargovan, H., 2005. Restorative justice and domestic violence: some exploratory thoughts. Agenda, 19 (66), 48–56.

- Herman, J.L., 2003. The mental health of crime victims: impact of legal intervention. Journal of traumatic stress, 16 (2), 159–166.

- Hester, M., et al., 2003. Domestic violence: making it through the criminal justice system. University of Sunderland. Northern Rock Foundation.

- Hester, M., 2006. Making it through the criminal justice system: attrition and domestic violence. Social policy and society, 5 (1), 79–90.

- Hester, M., 2013. Who does what to whom? Gender and domestic violence perpetrators in English police records. European Journal of criminology, 10 (5), 623–637.

- Hester, M., et al., 2015. Occurrence and impact of negative behaviour, including domestic violence and abuse, in men attending UK primary care health clinics: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open, 5, 1–10.

- Hester, M, et al. 2019. Evaluation of the drive project – a three-year pilot to address high-risk, high-harm perpetrators of domestic abuse. http://driveproject.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/DriveYear3_UoBEvaluationReport_Final.pdf.

- Hester, M. and Lilley, S.-J., 2016. Rape investigation and attrition in acquaintance, domestic violence and historical rape cases. J.of investigative psychology and offender profiling, 14, 1–14.

- Hester, M., and Lilley, S., 2018. More than support to court: rape victims and specialist sexual violence services. International review of victimology, 24 (3), 313–328.

- Hirschel, D. and Hutchinson, I.W., 2003. The voices of domestic violence victims: predictors of victim preferences for arrest and the relationship between preference for arrest and revictimization. Crime & delinquency, 49 (2), 313–336.

- HM Government, 2013. Circular: new government domestic violence and abuse definition. London: Home Office. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/new-government-domestic-violence-and-abuse-definition.

- HMIC. 2014a. i Everyone’s business: Improving the police response to domestic violence. Available from: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/improving-the-police-response-to-domestic-abuse.pdf [Accessed 17/10/19].

- HMIC. 2014b. ii Crime recording: making the victim coun. Available from: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/wp-content/uploads/crime-recording-making-the-victim-count.pdf [Accessed 17/10/19].

- HMIC. 2015. Increasingly everyone’s business: a progress report on the police response to domestic abuse. Available at https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/wp-content/uploads/increasingly-everyones-business-domestic-abuse-progress-report.pdf.

- HMICFRS. 2017. A progress report on the police response to domestic abuse. Available from: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/wp-content/uploads/progress-report-on-the-police-response-to-domestic-abuse.pdf [Accessed at 17/10/19].

- HMICFRS. 2018a. Cleveland Police: Crime data integrity inspection 2018. Available from: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/publications/cleveland-police-crime-data-integrity-inspection-2018/ [Accessed 17.10.19].

- HMICFRS. 2018b. Peel: Police effectiveness 2017, A National Overview. Available from: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/wp-content/uploads/peel-police-effectiveness-2017-1.pdf [Accessed 17.10.19].

- Hoyle, C., and Sanders, A., 2000. Police response to domestic violence: from victim choice to victim empowerment? The British Journal of criminology, 40 (1), 14–36.

- Institute for Government, 2020. The Criminal Justice System; How government reforms and coronavirus will effect policing, courts and prisons. https://instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/criminal-justice-system_0.pdf accessed 16/12/2021.

- Kelly, L., and Westmarland, N., 2016. Naming and defining ‘domestic violence': lessons from research with violent men. Feminist review, 112 (112), 113–127.

- Mackenzie, C., Rogers, W., and Dodds, S., 2014. Vulnerability: New essays in ethics and feminist philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Natarajan, M., 2016. Police response to domestic violence: A case study of TecSOS mobile phone use in the London metropolitan police service. Policing (Oxford), 10 (4), 378–390.

- NICE, 2014. Domestic violence and abuse: How social care, health services and those they work With Can respond effectively. London: NICE. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph50 [Accessed 18.10.19].

- ONS. 2017. Domestic Abuse in England and Wales: year ending march 2017. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/domesticabuseinenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2017 [Accessed 17.10.19].

- ONS. 2018. Domestic abuse in England and Wales; year ending March 2018. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/domesticabuseinenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2018 [Accessed 17.10/19].

- Robinson, A., and Cook, D., 2006. Understanding victim retraction in cases of domestic violence: specialist courts, government policy, and victim-centred justice. Contemporary justice review, 9 (2), 189–213.

- Robinson, A.L., and Stroshine, M.S., 2005. The importance of expectation fulfilment on domestic violence victims’ satisfaction with the police in the UK. Policing: An International Journal of police strategies & management, 28 (2), 301–320.

- Rumney, P.N.S., et al., 2019. A police specialist rape investigation unit: a comparative analysis of performance and victim care. Policing and society, 30 (5), 1–21.

- Safer London. 2016. Pan-London Domestic violence needs assessment report: Summer 2016. Available from: https://saferlondon.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/PLDV-Needs-Assessment-Final-low-res.pdf [Accessed 18.10.19].

- Sleath, E., and Smith, L.L., 2017. Understanding the factors that predict victim retraction in police reported allegations of intimate partner violence. Psychology of violence, 7 (1), 140–149.

- Stanko, E.A., 1992. Domestic violence. In: G.W. Cordner, and D.C. Hale, eds. What works in policing: operations and administration examined. Anderson, OH: Routledge, 49–61.

- Stanko, B., 2008. Managing performance in the policing of domestic violence. Policing: A Journal of Policy and practice, 2 (3), 294–302.

- Stanko, B., and Williams, E., 2009. Reviewing rape and rape allegations in London: what are the vulnerabilities of the victims who report to the police? In: M.A.H. Horvath, and J.M. Brown, eds. Rape: challenging contemporary thinking. Cullompton: Willan, 207–228.

- Stark, E., 2007. Coercive control—men’s entrapment of women in everyday life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stark, E. and Hester, M., 2019. Coercive Control: Update and Review. Violence Against Women, 25 (1), 81–104.

- Stiles-Shields, C. and Carroll, R.A., 2015. Same-sex domestic violence: prevalence, unique aspects, and clinical implications. Journal of sex & marital therapy, 41 (6), 636–648.

- Stubbs, J., 2007. Beyond apology?: domestic violence and critical questions for restorative justice. Criminology & criminal justice, 7 (2), 169–187.

- Walker, S.L., et al., 2019. Rape, inequality and the criminal justice response in England: The importance of age and gender. Criminology & criminal justice, 21 (3), 297–315.

- Walker, S.-J., Hester, M., and Turner, W., 2018. Evaluation of European domestic violence perpetrator programmes: toward a model for designing and reporting evaluations related to perpetrator treatment interventions. International journal of offender therapy and comparative criminology, 62, 868–884.

- Walklate, S., 2007. What is to be done about violence against women? The British journal of criminology, 48 (1), 39–54.

- Walklate, S., Fitz-Gibbon, K., and McCulloch, J., 2018. Is more law the answer? seeking justice for victims of intimate partner violence through the reform of legal categories. Criminology & criminal justice, 18 (1), 115–131.

- Westmarland, N., Johnson, K., and McGlynn, C., 2018. Under the radar: The widespread Use of ‘Out of court resolutions’ in policing domestic violence and abuse in the United Kingdom. The British journal of criminology, 58 (1), 1–16.

- Westmarland, N., McGlynn, C., and Humphreys, C., 2018. Using restorative justice approaches to police domestic violence and abuse. Journal of gender-based violence, 2 (2), 339–358.

- Womens Aid. 2007. domestic abuse and equality: older women: Briefing 3, Available from: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/domestic_abuse_equality_-_older_women.pdf [Accessed 17.10.19].