ABSTRACT

Democratic police reform models dominate discussions on police reform in non-Western contexts. Researchers and practitioners often attribute reform failings to personnel and institutional failure within police organisations, the weakness of formal external institutions of control and accountability, lack of inclusion of, or customisation to, hybrid forms of governance or a failure to address social injustice more broadly. Drawing on analysis of political and police transformation in Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Russia this paper suggests low state capacity and authoritarian and neo-patrimonial politics present more prominent barriers to DPR. In low capacity states police pay is insufficient and bureaucratic control weak. Formal reforms have little influence over the police who are influenced by organised crime and corrupt police leaders and politicians. Authoritarian and neo-patrimonial elites often stymie reform initiatives which undermine their political and economic interests. Full DPR is thus unlikely without increasing state capacity and political elite will and capacity to democratise control of the police. But contrary to democratisation being key to successful reform the relationship between regime type and reform outcomes is more nuanced. Partial reform is possible where a partially authoritarian/neo-patrimonial regime has the ability to improve police effectiveness and clampdown on corruption and prioritises these.

Manuscript

Despite the billions of dollars spent on democratic police reform (DPR) in non-Western contextsFootnote1 many initiatives fail to alleviate police-related problems, such as excessive violence, corruption and police repression. International donors promote DPR as a means of addressing theseFootnote2 by reforming the formal political and legal institutions which control police and hold them accountable and police organisations through personnel and internal policy changes (Bayley Citation2005, Peacock Citation2021). Major criticisms argue DPR fails because it is piecemeal and focuses on police organisations and training,Footnote3 lacks adaption to or inclusion of hybrid forms of governanceFootnote4 or is a means for donors to impose neo-liberal forms of governance.Footnote5 This paper argues DPR often fails because of two more proximate causes of failure: low state capacity and the predominance of authoritarian/neo-patrimonial politics. Where there is low state capacity, and a state inadequately pays its police, corrupt police and politicians resist DPR because it harms economic gains made through corruption and police involvement in organised crime. Where authoritarianism and neo-patrimonialism predominate, leaders resist DPR, which aims to distribute police power, because they rely on the police to maintain their political and economic positions.

The relationship between regime type and reform outcomes is, however, nuanced. This paper compares police and political transformation in Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Russia, 1990–2012. In all three cases, low state capacity drove police corruption and police involvement in organised crime, especially in the 1990s. These remained problems in Kyrgyzstan where power was fractured amongst authoritarian/neo-patrimonial elites. The Georgian and Russian governments increased state capacity in the 2000s, retained authoritarian and neo-patrimonial forms of governance and used police to further their own political and economic interests. Neither government democratised control of the police. But in Georgia, after 2003, the government initiated very successful anti-corruption police reforms by re-asserting its economic and bureaucratic control of the police and cracking down on organised crime, a top-down, rapid approach which shares similarities with anti-corruption police reforms in Singapore and Hong Kong (Manion Citation2004, Quah Citation2014). Partial reform, focusing on anti-corruption and police effectiveness, is therefore possible, if unusual, in authoritarian/neo-patrimonial regimes, but requires political elites with the will and ability to deliver these reforms. The Georgian case also indicates that increasing state capacity and clamping down on corruption, where they limit opportunities to block reform, may be more effective at realising democratic outcomes than democratisation of the police or reform, an approach not, however, without limitations and risk.

That authoritarian regimes produce authoritarian police is well knownFootnote6 and through the work of anthropologists, area scholars and criminologists we have a better understanding of how neo-patronageFootnote7 and low state capacityFootnote8 impact policing. But mainstream DPR research and policy and prominent critiques have under-conceptualised the impact of these in three key respects. First, states may not have much direct control of the police. Second, political and police elites may have strong interests in resisting reforms. Third, under particular conditions, political elites may be the main driver of reform but we have limited knowledge of how different types, forms or extent of political will, ability and conditions impact different types of reform (Shahnazarian and Light Citation2018).

This paper explains how low state capacity presents a prominent barrier to DPR and how authoritarian and neo-patrimonial regimes also present barriers to democratic control of the police, though improvements in police efficiency and anti-corruption may be possible if political elites have the inclination and ability to implement such reforms. The period 1990–2012 covers major changes in political and police transformation across the cases. Comparative political and historical analysis was used to analyse political transformations and data on police organisations obtained through historical analysis and over 2.5 years spent in the region between 2009 and 2012 and over 80 interviews in Russian and English with police, politicians, NGO workers and others who regularly interact with police.Footnote9 The cases were chosen because of their different patterns of political and police transformation. They cover three distinct parts of the former Soviet Union – Russia, Central Asia and the South Caucasus – and findings may be relevant to other former Soviet countries, which share similar police models and patterns of political transformation. I conclude the paper with some policy implications for reform in contexts with similar forms of governance.

State capacity, authoritarianism, neo-patrimonialism and police

State capacity, authoritarianism and neo-patrimonialism can be explained as per below. The approach build’s on Taylor’s framework, which classifies states by their ‘capacity’ and ‘quality’, the latter being the extent to which the state and its officials serve the interests of the population in a fair manner that promotes the general welfare (Taylor Citation2011). I replace ‘quality’ with degree of democracy/authoritarianism.

State capacity is a state’s routine power ‘ … to penetrate civil society, and to implement logistically political decisions throughout the realm.’ (Mann Citation1986). States assert their capacity primarily via their core administrative, legal, extractive and coercive capabilities (Skocpol Citation1985). Low state capacity states have little penetration into society and are dominated by personalised forms of governance, an incomplete monopoly of violence and limited control over the state’s territory (Andersen Citation2007). In contrast to routine power, these states’ authority is maintained by the exceptional powerFootnote10 of the organisations and individuals in charge of the state. This is ‘the range of actions which the elite is empowered to take without routine, institutionalised negotiation with civil society groups’ (Mann Citation1986). In sum, exceptional power is the power the state elite has over civil society, whilst routine power is the power of the state to penetrate and centrally coordinate the activities of civil society through its own infrastructure.

How a state exerts its capacity can be distinguished by different combinations of forms of domination – patrimonial, neo-patrimonial and legal-rational. These also give us different types of regime – democratic, hybrid and authoritarian. Neo-patrimonial regimes are a sub-type of authoritarian regimes. Authoritarianism describes regimes which do not organise periodically free and fair elections but here I define it more broadly also as a political practice undertaken by a political actor to sabotage any accountability he/she has to the citizenry by means of disabling their access to information and/or ability to express their political views (Glasius Citation2018). Neopatrimonialism is a mix of patrimonial and legal-rational bureaucratic domination. Under patrimonialism, all power relations between ruler and ruled are personal relations and there is no division between public and private. Under neo-patrimonialism there is that distinction, at least formally, even if, in practice, this is not observed (Erdmann and Engel Citation2007). To maintain a grip on power, a neo-patrimonial ruler relies on patronage to control the major sources of power within the country, including economic resources and control of the state’s coercive apparatus. The state’s legitimacy and survival rest upon its use of exceptional power to distribute resources via patron-client, vertical and personalised networks (Mann Citation1986, Andersen Citation2007).

Regimes are also distinguished by the type of domination dominant at the political level (i.e. the government) and the level of the state bureaucracy. Politicians always govern through an element of patrimonial domination, even in democracies. In a democracy, politicians are subjected to legal rules (i.e. the rule of law) and must be elected but neither is true of an authoritarian regime. A hybrid-regime contains some democratic features (e.g. regular elections) but also authoritarian elements (e.g. suppression of political opposition; manipulation of elections). It is possible to have an authoritarian regime with a legally constituted government and legal-rational bureaucracy but is more common for both to be dominated by neo-patrimonial forms of governance. Together, the aforementioned framework allows us the following typology ():

Table 1. Regime types.

The above provides a framework to examine the political context in which DPR occurs by classifying regimes by state capacity (high to low) and degree of democracy/authoritarianism (democratic to authoritarian). Classifications, based on ideal-types, have been critiqued for oversimplifying complex political conditions, inadequate conceptualisation of key terms and problems of accuracy and measurement (Saeed Citation2020). Comparison, however, requires simplification and such models can provide an overview which can be supplemented by additional information to better explain types of governance and their impact on police. The framework here separates out governments and bureaucracies and state capacity from degree of democracy/authoritarianism to avoid overly simplistic categorisation (e.g. assuming high state capacity necessarily correlates to democracy or vice-versa). It also allows for a means of measuring the latter two, as per Taylor, using the World Bank’s World Governance Indicators (WGIs). Combining and averaging the Political Stability, Absence of Violence and Government Effectiveness WGIs provides an approximation of state capacity and combining and averaging the Voice and Accountability, Rule of Law and Control of Corruption indicators an approximation of degree of democracy/authoritarianism (Taylor Citation2011).

The framework helps narrow down which factors impact the success or failure of DPR. It focuses attention on the state which has an important influence over police reform because of the key mechanisms it has to influence police behaviour. The state authorises police; has a substantial role in deciding police strategy and, often, operational and tactical choices; can recruit and promote key personnel; and it has substantial economic leverage over the police (i.e. it pays them). In an ideal-type democracy, the state can sufficiently resource and control the police via formal rules and regulations which work in the interests of the democratic polis. Where state capacity is low, however, police behaviour is influenced by economic resources outside the formal structure and police are heavily involved in corruption and organised crime. Where authoritarian forms of governance dominate, politicians and police leaders use formal rules and relationships to control recruitment, promotion and strategy often in the interests of the government, rather than the polis as a whole. In a neo-patrimonial regime, politicians and police leaders also use informal institutions to the same effect and in the interests of their patronage network.

Democratic police reform

The link between low state capacity and authoritarian/neo-patrimonial politics and reform is, however, under-conceptualised in policy and research. DPR is a set of measures that aims to create a police which: is effective; upholds the rule of law equally (i.e. regardless of race; gender; etc.); legitimate; accountable; observes human rights and can be sustainably maintained.Footnote11 In this paper I use DPR and police reform interchangeably, though I also refer to partial reform which only achieves some of these goals. I group the literature into four schools that vary by what practitioners and scholars identify as the main reasons for DPR failing and in the offering of alternatives.

Mainstream approaches to DPR dominate practitioner approaches and are closely related to the broader literature on security sector reform (SSR) (Bayley and Perito Citation2010, DCAF Citation2019, Peacock Citation2021). Bayley’s Citation2005 work offers the most developed example. He argues six strategies are key to the realisation of a democratic police service: providing a legal basis for the new police; creating a specialised, independent oversight mechanism; staffing the police with the right sort of people; developing the capacity of police executives to manage reform; making the prevention of crime as it affects individuals the primary focus of policing; and requiring legality and fairness in officer actions. Bayley, and other commentators, note DPR initiatives often fail because they lack local political support, are rarely comprehensive nor well targeted to contexts and focus mostly on police organisations and reorganisation, training and equipping (Bayley Citation2005, Wozniak Citation2017, Citation2018). But he does not discuss in detail the causes of failure other than referring to disorder and conflict, under-development, weak institutions and legacies of political repression (Bayley Citation2005). Because these are mainly unexamined their importance or relationship to the measures listed above is unclear (i.e. are the priorities the same if disorder and conflict is the main cause of failure as opposed to legacies of political repression?).

Broadly, three main schools critique mainstream approaches: hybrid-governance, post-structural and realist. All three question the feasibility of the Weberian state model propagated by DPR and argue that approaches based upon it causes donors and reformers to ignore indigenous governance and security institutions (Goldsmith and Dinnen Citation2007). The hybrid-governance school emphasises the failure of reformers or donors to develop models and partnerships with non-state actors who can be more effective and legitimate than formal state institutions (Baker Citation2010, Gordon Citation2014). Post-structuralist approaches critique political elites and donors further arguing that concepts such as DPR and SSR are means of projecting Western models of security and governance and promoting international and state neo-liberal elites’ and donors’ interests (Ryan Citation2011, Ellison and Pino Citation2012). The realist school identifies under-development and weak state and police institutions as causes of police-related problems. Like the hybrid-governance school, it is critical of external actors’ ability to reform such structures but it is more critical of non-state actors. It recognises that political elites and non-state actors can act as facilitators but also powerful barriers to reform (Colletta and Muggah Citation2009, Hills Citation2020). Overcoming these barriers may require trying to incentivise powerful but unsavoury actors towards reform goals and more limited goals, such as stabilisation, an approach which has gained some traction in donor circles (Stabilisation Unit Citation2019).

The schools each have their own advantages but the first three only partially account for the influence of low state capacity, authoritarianism and neo-patrimonialism. Mainstream DPR emphasises the importance of reforming formal institutions but says little about how to manage authoritarian/neo-patrimonial or non-state actors opposed to reform. The hybrid-governance school pays insufficient attention to the barriers to reform posed by non-state actors. The post-structuralist school highlights that donors’ and state elites may use reform to further their own interests and the need for broad political and economic reform to address wider social injustice. But it does not offer clear guidance on what is possible where the conditions for broad change are lacking or only partially present. Importantly, all three schools emphasise the importance of democratising control of the security sector and reform processes to include civil society, hybrid or disenfranchised actors. But such an approach can also increase opportunities for state and non-state actors to block reform. The realist school does highlight these potential barriers and suggests prioritising building capacity and political will for reform by prioritising moderate measures and stabilisation, though there are few studies within this school. I shall return to a discussion on the strengths and limitations of the various schools after first explaining how low state capacity, authoritarianism and neo-patrimonialism presented barriers to police reform in the former Soviet Union which were partially overcome in Georgia.

The impact of authoritarianism, neo-patrimonialism and low state capacity on police in Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Russia

In the early 1990s, state capacity was initially low as each state struggled with democratisation, marketisation, attempts at state-building and challenges to Soviet-era conceptions of national identity. The Putin regime increased state capacity in the 2000s by strengthening the executive vis-à-vis other parts of government and Russia’s regions, and it has become increasingly authoritarian (Sakwa Citation2010, Gel’man Citation2021). State capacity was especially low in Georgia in the 1990s as a result of secessionist conflicts and the kleptocratic regime of Eduard Shevardnadze (1995-2003). After the 2003 Rose Revolution, a new government of younger, more democratically-minded reformers led by Mikheil Saakashivili increased state capacity by strengthening executive power, monopolising political patronage under one network and cracking down on lower level corruption across the public sector. The government exhibited some authoritarian tendencies (e.g. an intolerance of political opposition; some suppression of independent media) and high-level corruption remained a problem (Kupatadze Citation2012, Jones Citation2013). But it was less authoritarian and corrupt in comparison to Russia and ceded power in democratic elections in 2012 to a coalition led by the billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili who is widely regarded to control the country via his patronage network (Aprasidze and Siroky Citation2020). Kyrgyzstan’s state capacity was initially low but not unstable under the presidency of Askar Akaev (1991-2005). Instability increased in the 2000s and Akaev and his successor, Kurmanbek Bakiev, were deposed in 2005 and 2010 respectively. Kyrgyz politics remains fragmented and characterised by high levels of corruption and political leaders using their positions to support their patronage networks (Engvall Citation2022).

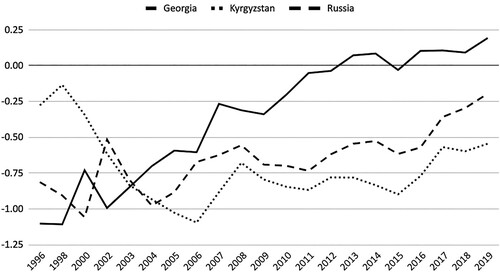

The above transitions are reflected in the Worldwide Governance Indicators for the period 1996-2019. State capacity (high + 2; low −2) was initially low in all three countries, has increased somewhat in Russia and Kyrgyzstan and more considerably in Georgia. State capacity is surprisingly high in the 1990s in Kyrgyzstan which is partly attributable to relative stability under Akaev’s early presidency but probably more to limitations with the data which improved in quality from 2002 onwards ().

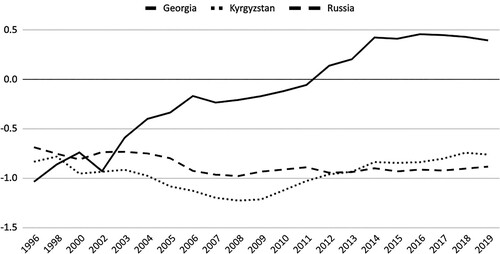

On the degree of authoritarianism/neo-patrimonialism (−2) versus democracy (+2), there has been little change in Kyrgyzstan’s or Russia’s scores but Georgia’s democratic score increased considerably after the Rose Revolution ().

Problems in policing

Policing replicated patterns in political transformation and barriers to reform were caused by low state capacity and the pre-dominance of authoritarian/neo-patrimonial forms of governance. These factors affected the main mechanisms the states had to control their respective police.

Authorisation

Each state inherited policing organisations which, in Soviet times, were politicised, militarised, repressive and accountable only to the leadership through the Communist Party (Shelley Citation1996). In Kyrgyzstan, Russia and pre-Rose Revolution Georgia there were few changes to the formal powers regulating policing, which remained based on this model.

In Russia, the Interior Ministry (MVD)Footnote12 retained a rigid command-structure, accountable only to itself and political elites (Beck and Robertson Citation2005). Legal frameworks inherited from the Soviet era were balanced considerably in favour of the state over the rights of the individual and often written vaguely to enhance the discretion of administrators and provide the regime with legal means to use against opponents (Solomon Citation2008). Subsequent reforms tightened up some of the vagueness but did not curtail the hierarchical subordination of the police by improving transparency or accountability to actors outside of the MVD structure or to adequately constrain the police within the rule of law (Burnham and Kahn Citation2008, Galeotti Citation2012). The Kyrgyz and pre-Rose Revolution Georgian police similarly operated in a legal and institutional framework that changed little from Soviet times (Wheatley Citation2005, Lewis Citation2011).Footnote13

The decline in state economic control of the police

The dislocation caused by transition processes drastically reduced each state’s economic leverage over the police and resulted in a sharp increase in corruption and police involvement in organised crime.

Police in Russia were poorly paid throughout much of the 1990s and 2000s. Salaries doubled between 2005 and 2008 but remained comparatively low (Taylor Citation2011). In St. Petersburg, in 2009, a middle-ranking officer with ten years’ service earned approximately $530 per monthFootnote14 compared to a GDP per capita of approximately $8000 in 2009 (World Bank Citation2022).Footnote15 Low salaries drove high levels of corruption and contributed to a growth in organised crime groups’ influence over the police, which was especially marked in the 1990s (Gerber and Mendelson Citation2008). Police were paid to obtain information to help commit crimes, disrupt investigations, to arrest and start investigations against rival businesses and provide practical support (eg protection; supplying weapons) (Salagaev et al. Citation2006).Footnote16 By 1997, an intense period of violent competition and consolidation had produced fewer, larger, organised crime groups that were also increasingly pushed out of the organised crime market by state actors who offered better protection to businesses because of superior resources and the legal protections they could offer (Volkov Citation2002).

In Kyrgyzstan, the central state lacked any strong economic hold over police (O’Shea Citation2015). The total poverty line was at around $385 in 2008Footnote17 but in 2011, the lowest police ranks earned only around $215 per month and the highest around $320. Before 2010, the basic figure was around $130-$150.Footnote18 The police was a predatory force during the time period in question. Citizens were frequently forced to pay bribes and also chose to do so to avoid violations being processed.Footnote19 The police were also involved in more serious acts of extortion.Footnote20 Towards the end of the 2010s, the influence of the criminal underworld on the police grew because of a greater cross-over between politicians and organised crime groups (Uzakbaev Citation2009). During Bakiev’s presidency, the MVD struggled to retain power over regional and institutional power brokers, including organised criminals and Bakiev and his officials were widely suspected of involvement in the drugs trade (Kupatadze Citation2008).Footnote21

Pre-Rose Revolution police in Georgia were extremely poorly paid. The official poverty line was around $50 in 2002 but official pay was only somewhere in the region of $44-63 per month (World Bank Citation2002, Boda and Kakachia Citation2005).Footnote22 By the mid-1990s, the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) provided racketeering roofs, directly controlled large business, and even owned Georgia’s most famous football club, Dynamo Tbilisi (De Waal Citation2010). The police had a reputation for brutalityFootnote23 and citizens were regularly forced to pay bribes at traffic stops and to get driving licences, registration documents and so on (Hensell Citation2012).

Authoritarian and neo-patrimonial political direction and influence on recruitment and promotion

Police strategy and some operational and tactical choices were dictated by the logic of each country’s politics which were primarily neo-patrimonial with aspects of authoritarianism. State leaders appointed figures within their patronage networks to top policing roles and used this influence to further their own political and economic interests.

In Russia under Yeltsin, formal political elites and other influential figures used the police were used to spy on and wiretap political and economic rivals throughout the struggles of the 1990s (Knight Citation1996, Timoshenko Citation1997). Under Putin, the rule of law is conveniently disregarded when it suits the needs of the Kremlin. The jailing of the oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky in 2005, for example, did not meet the prerequisites of the Criminal Procedure Code which came into effect in 2002 (Hendley Citation2010). The MVD tended to play a secondary role to other security agencies, such as the FSBFootnote24 and procurator, in factional political struggles but was a useful tool for the regime to curtail the mobilisation of any popular political opposition, playing an important role in heavily policing opposition demonstrations (March Citation2012). Political patronage is more centralised under Putin. Under Yeltsin, various regional and local political groupings used their influence to appoint police (Taylor Citation2011). Putin’s regime restored centralised control by installing people from outside the MVD into top positions and by centralising control over important regional appointments and budgets (Taylor Citation2011, Galeotti Citation2012).

The Kyrgyz police remained politicised to protect the interests of incumbent elites and were used for the purposes of political infighting. In 2006, an opposition political figure was jailed in Poland for smuggling heroin only to be released after a Polish investigation concluded the drugs had been crudely planted. A Kyrgyz airport official later claimed he had been instructed by Bakiev’s brother to plant them (Kupatadze Citation2012). The police replicated the authoritarian tendencies of Kyrgyzstan’s political leaders, for example in putting down popular protests, but politicisation did not always work in the interests of the elites controlling the central state and its form mirrored that of Kyrgyzstan’s fractured political environment. Thus, police in Kyrgyzstan’s second-largest city, Osh, were used to intimidate the mayor’s opponents (Marat Citation2010). Patrimonialism was also prominent throughout the MVD, with incoming interior ministers firing senior officials who had advanced under their predecessors and advancing men from their own regions and home towns (Uzakbaev Citation2009, Kupatadze Citation2012).

In Georgia, powerful political and economic figures used the police were used to protect their political and economic interests.Footnote25 After taking control of the presidency, Shevardnadze filled its leadership mainly from the old police elites, with many of whom Shevardnadze had served as head of the MIA during the Soviet era (Kupatadze et al. Citation2006). Although the political environment was relatively open, pre-Rose Revolution police were used to blackmail political opponents and protect patrons’ interests (Kupatadze et al. Citation2006).

Authoritarian and neo-patrimonial forms of governance also dominated recruitment, promotion and governance of the police at lower levels. In Russia, as in the other cases, the police prioritised orders from immediate supervisors over the rule of law (Gladarev Citation2012). The broader culture of the MVD, and other security agencies, emphasised extra-constitutional loyalties to individuals rather than adherence to rules (Galeotti Citation2010). Ordinary officers had limited formal protections against abuses by their bosses and were liable to be scapegoated in the case of publicised institutional misdemeanours. Immediate superiors also held a strong economic hold over subordinates. 30–60 percent of ordinary Russian officers’ monthly salaries were decided by immediate managers giving them little manoeuvre to resist politicised or criminal directives (Gladarev and Tsinman Citation2011, Gladarev Citation2012).

This pattern was replicated in Kyrgyzstan. Formally, officers were accountable only to their superiors (Marat Citation2013). Despite the centre’s lack of control, the MVD retained a strict militarised hierarchy of subordination.Footnote26 Officer dependence on their superiors for their positions and a lack of external oversight perpetuated high levels of police corruption and violence. Several officers interviewed explained that the causes of bribery and corruption stemmed from the financial demands made of them by their superiors:

There was no corruption during training. That all changed when I started work! It was, ‘How many cars did you stop? Where's the money?’ Footnote27

Like Russia, refusing to participate in corrupt activities threatened one’s position (Lewis Citation2011).Footnote28

The pre-Rose Revolution police in Georgia was dominated by norms familiar to a repressive, criminalised and predatory structure.Footnote29 The Georgian police were formally governed by a Soviet model with little external oversight and, in any case, the executive’s weak economic control meant the fortunes of ordinary officers were dependent on whoever had the strongest patronage over their particular units be it within the MIA, local patrons or criminals (Kukhianidze Citation2003, Fritz Citation2005, Wheatley Citation2005).

Barriers to reform in Kyrgyzstan and Russia. Partial reform in Georgia

From 1990 to 2012 there was little meaningful police reform in Kyrgyzstan or Russia but the post-Rose Revolution government introduced very effective anti-corruption reforms.Footnote30

Reform efforts in Kyrgyzstan are widely regarded to have been co-opted by political and police elites.Footnote31 As one former officer commented, ‘Every new minister declares reforms and usually that means [the] shuffling of [the] MVD’s structure in order to remove unwanted persons and appoint his own favourites’.Footnote32 Akaev and Bakiev strengthened state structures to monopolise the main resource flows to their networks, generating substantial discontent amongst other elites and the wider population and, ultimately, contributing to their own downfall (Temirkulov Citation2010). This had a direct impact on police reform. Without central state capacity for or interest in reform changes to the police were implemented to enhance the political or economic interests of particular factions within, or external to, the MVD (Marat Citation2013). Marat and Isa for example interpret the transfer of responsibility for counter-narcotics from the Drug Control Agency to the MVD in 2007 as an attempt by Bakiev to gain control of the drugs trade (Marat and Isa Citation2010).

There is a general consensus amongst commentators of the Russian police that there has been little meaningful reform (Taylor Citation2014).Footnote33 In the early 2000s increases in state capacity improved executive control of the police and a 2001 change in the law gave the president greater control over keys appointments. But the prime purpose of subsequent reforms has been to strengthen the regime’s ability to respond to external threats and those from within. For example, reforms in the mid-2000s were dictated by the logic of a struggle between factions in the run up to Putin’s departure,Footnote34 before Dmitry Medvedev’s presidency (2008–2012), which Putin is widely regarded to have dominated. Two factions competed to influence Putin’s succession led by Igor Sechin, Putin’s chief of staff, and Viktor Zolotov, head of the presidential security service, and his ally Viktor Cherkesov, head of the Federal Antinarcotics Committee (FAC) (Radio Free Europe Citation2007). In 2006, Vladimir Ustinov, head of the General Procurator’s Office (GPO) and ally of Sechin, was unexpectedly dismissed by Putin, apparently after one of Cherkesov’s deputies recorded a conversation between him and Sechin, in which the idea was put forward that Ustinov could succeed Putin (Sakwa Citation2011). What followed was a series of personnel and administrative changes which were not designed to improve either the workings of the FAC or GPO but rather to reduce the Sechin faction’s power and maintain a balance between other factions (Taylor Citation2011).

The police reform programme announced by Medvedev in December 2009 was also driven by the political and economic interests of political and police elites and suffered from the same problem as earlier efforts (Taylor Citation2014). First, responsibility for the implementation of reform was given to the MVD leadership, which had its own power bases to protect and the least incentive to carry it out effectively (Galeotti Citation2012, Semukhina and Reynolds Citation2013).Footnote35 Second, though there is some division in analysis between commentators who cite considerable turnover in the MVD’s leadershipFootnote36 and those who mark continuation (i.e. senior personnel passing re-attestation processes),Footnote37 changes did not produce a group of empowered reformers within the MVD. Third, no systematic measures were taken to counteract predatory policing or police violence.

Police reform in Georgia was successful because the government increased state capacity and combined this with anti-corruption reforms as part of a broader state-building programme.Footnote38 The government re-integrated a territory that had broken away in the 1990sFootnote39 and implemented constitutional changes to consolidate executive power vis-à-vis the legislature and local government (Areshidze Citation2007, Jones Citation2013). It tripled state revenues from 2003 to 2006, reduced the size of the bureaucracy by firing around a quarter to half of state employees (28,000–40,000),Footnote40 raised civil service pay (up to fifteen times in some cases) and tackled low-level patrimonialism and corruption (e.g. by increasing computerisation of payment of salaries, services, fines and taxes).Footnote41 The reforms established a single dominant neo-patrimonial network that key elites used to enhance their political and private economic interests and to impose their neo-liberal governance model, which did little to alleviate poverty (Kupatadze Citation2012, Jones Citation2013). But they did establish a more than functioning state and move Georgia from being in the bottom ten most corrupt countries in the world, as ranked by Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index, to consistently in the top third by the 2010s, a trend replicated in other sources (Nasuti Citation2016).

Police reform was a key component of the state-building project. The government consolidated a number of agencies into one organisation responsible for policing,Footnote42 fired around 16,000 police and downsized the MIA from 56,000 to 33,000,Footnote43 increased the budget for public order and security from $19.3 million in 2003 to $253 million by 2007Footnote44 and increased average wages around nine to ten times.Footnote45 New police managers introduced more practical-orientated training and professionalised recruitment and promotion processes. These helped to institutionalise lower-level policing within a legal-rational framework which regulated a far greater proportion of police activity via rules rather than patronage. The government also cracked down on organised crime and links between criminals and police in 2004–2005. It rapidly arrested key criminal figures, introduced new anti-racketeering legislation and, albeit with scant regard for the rule of law,Footnote46 seized tens of millions worth of dollars from former officials and known organised criminals.

The government did not democratise control of the police or the reforms to incorporate the legislature, judiciary or civil society and it retained a politicised police. Patronage remained the main mechanism for appointing senior leaders.Footnote47 The police were used to clampdown on both political opposition and popular protest, police impunity remained a prominent issue and the retention of neo-patrimonial forms of governance at upper levels means the reforms’ success remain dependent on personalities (Light Citation2014, Darchiashvili and Mangum Citation2019). The reforms however resulted in a quick and marked decline in corruption and improvements in police efficiency, both of which have been sustained. Multiple surveys in the years after the Rose Revolution indicated that a large majority of Georgians had a favourable opinion of law enforcement agencies’ performance and levels of full or partial trust has not fallen below 45 per cent.Footnote48 Various qualitative sources corroborate these findings.Footnote49

Though state capacity increased in Russia and Georgia, policing improved substantively only in Georgia because the new elites also had the inclination and ability to clamp down on corruption. In Russia the regime lacked both. Though the Putin regime does not gain much from nor need police corruption, as it can manipulate more lucrative economic sectors (e.g. fossil fuels), the centre overall requires a weak rule of law because it relies on farming out rent-seeking opportunities in return for political support (Dawisha Citation2015, Gel’man Citation2021). Russia’s sheer size too limits the ability of a single neo-patronage network to dominate the country,Footnote50 whereas Georgia’s much smaller size made that easier. Compared to the new Georgian elite, the Putin regime is also older and characterised by a Soviet institutional culture where officials seek security via relationships rather than the rule of law, central government sets impossible demands requiring officials to utilise patronage and corruption to protect themselves, and the absence of an impartial civil service to reduce favouritism in public service (Özsoy Citation2007). Police reform has therefore relied on ineffective Soviet-style tactics of advocating tighter discipline and control, punishment of transgressors, and, when these fail, denying a problem exists, and presenting whistleblowers as alarmists, or to look for scapegoats. In Georgia, many of the new elite were young and Western educated, and driven by a sense that tackling at least petty corruption was vital to the very integrity of the country (Nasuti Citation2016). They also had an understanding of bureaucratic and technical means to counter it based in part on Western managerial and governance practices.

Discussion

The contrasting patterns of police reform have implications for understanding the barriers to reform in non-Western states and how they might be overcome.

DPR fails where there is insufficient state capacity. In Kyrgyzstan, pre-Rose Revolution Georgia and Russia in the 1990s, even if political will had been present the state was too weak to counter non-state actors nor prevent the police (or their political patrons) from predating on the population. The success of the Georgian reforms was founded on the government increasing state capacity and using this to assert its economic, political and bureaucratic control over the state and police and to counter organised criminals and corrupt police and politicians who would likely have blocked reform. As the Russian case demonstrates, however, increased state capacity is not sufficient to achieve even partial reform.

The predominance of authoritarianism/neo-patrimonialism may be either a profound or a partial barrier to reform. To explain this, we need to differentiate between democratic control of the police or reform and some democratic outcomes in the form of improved effectiveness and lower corruption. The Georgian government, and the Russian government to a greater extent, did not democratise either the political system or control of the police and both retained politicised police. The most plausible explanation for this is that authoritarian or hybrid-regime leaders are reluctant to fully democratise control because they believe it is necessary for regime security (Greitens Citation2016). But, though it retained authoritarian/neo-patrimonial forms of governance at upper levels, the Georgian government had the political will and ability to reduce corruption by removing corrupt individuals and institutionalising policing within a legal-rational framework at lower levels. Thus, it achieved some democratic goals without democratisation.

The contrasting patterns of reform and the causes for these contrasts can be mapped accordingly ():

Table 2. Contrasting patterns of political and police transformation in Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Russia (1990-2012).

The main barriers to reform are therefore low state capacity and authoritarian and neo-patrimonial political and police elites’ resistance to reform. Democratic control of the police is not possible in a full authoritarian regime and unlikely where neo-patrimonial forms of governance predominate but improvements in police effectiveness and anti-corruption are possible under such conditions where there is a consolidation of power and political elites have the inclination and ability to deliver such reforms.

This explanation for why reform fails or succeeds contrasts with main approaches to DPR. Mainstream approaches rightly identify that reform requires reform of the police organisation and key political institutions. In practice, they often focus on the former and on reorganisation, training and equipping (Bayley Citation2005, Wozniak Citation2018). But police-related problems in the cases were not caused, in the main, by shortfalls in these areas but by formal structures, processes and rules having far less influence over policing vis-à-vis neo-patrimonial politicians and police and, as highlighted by the realist school, the influence of non-state actors on policing. Mainstream approaches also underplay that reform can fail not only because of the absence of political will but because authoritarian and neo-patrimonial politicians and police block it. They also are unclear on what types of reform are possible under different political conditions.

The hybrid-governance school argues success is likely to depend on the inclusion, if not prominence, of non-state actors. Including non-state actors and civil society groups in governance of the police, or institutionalising police accountability to such groups, or anyone other than political and police elites, may be an effective way of reducing police violence, corruption and even repression if accompanied by broader political reform. But hybrid-governance can both overstate non-state actors’ adherence to democratic norms and their potential to overcome vested interests opposed to reform, including those within and external to the state (Andersen Citation2012). In Kyrgyzstan, Russia and pre-Rose Revolution Georgia neo-patrimonial and criminal political elites and powerful non-state actors such as organised criminals have blocked reform. In Georgia, success was achieved by preventing such actors from doing so.

Post-structural critiques focus attention on problems caused by political elites especially within the global politico-economic order (e.g. Western donors). It is important to question in whose interest does DPR actually work, particularly where coercive state structures are to be strengthened to impose one group’s power, as in Russia and post-Rose Revolution Georgia, or without addressing other forms of injustice. But when focusing on international factors these approaches can underplay the extent to which local and national state and non-state actors cause police-related problems and block reform. Post-structural approaches also place insufficient attention to the key role political elites can play in driving reform. The relatively successful Georgian reforms were top-down and driven by state political elites.

Finally, all three approaches argue that DPR requires democratisation of control of the security sector. But, as the Georgian example demonstrates, partial reform is possible without democratisation. A narrow approach may also help to reduce opportunities to block reform. This is not without risk. Neo-patrimonial and authoritarian political elites in the cases, including post-Rose Revolution Georgia, used their consolidated control of the police to further their economic and political interests. I shall discuss the implications of this finding further below in relation to policy.

Conclusion

Lessons drawn from the case studies suggest a number of future directions for policy on DPR.

The first policy implication is that successful police reform requires a state to increase its capacity to control the police organisation, by raising police salaries and enhancing its bureaucratic control vis-à-vis actors external to the police. Such a measure, however, carries risk and may only result in democratic policing outcomes if the regime is dominated by actors with an interest and capacity to deliver these outcomes, even if partially. In many hybrid-regimes, and some democratic, politicians selected by democratic mechanisms may behave in an authoritarian or neo-patrimonial fashion (González Citation2020). Strengthening a state’s capacity over its police may thus enhance its powers of repression or corruption. At the very least though, policymakers, including donors, need to consider if DPR is possible in the absence of sufficient state capacity. Under such conditions, police behaviour will likely be influenced by corrupt patrons and political leaders external to the police and the ability of the police organisation to act as an agent of democratic change will be very limited. Nevertheless, DPR cannot be achieved without some strengthening of state capacity because police authorised to use coercion but severely under-resourced will likely be predatory. Ensuring that increases facilitate democratic outcomes is likely to require some of the methods proscribed by mainstream DPR (i.e. development and enforcement of policies to protect human rights) and a focus on anti-corruption (see below). Where there are prominent political barriers to reform or the risk of enhancing repression is too great, it may be more effective to focus on building coalitions in support of reform or, for donors, supporting civil society with that goal, rather than prioritising working with the state or police organisation.

Full DPR requires reformers to tackle the influences of authoritarianism and neo-patrimonialism within and external to the police. A police organisation cannot be democratic, providing a service equitably, if it favours those within or connected to a regime or its patronage network. As Georgia, and similar cases in Singapore and Hong Kong, demonstrate, a capable and willing government can use anti-corruption measures to reduce the influence of neo-patrimonialism (Manion Citation2004, Quah Citation2014). But it is less clear how effective democratisation of control of the police is and when it should occur. One controversial policy implication following the Georgian example is that police effectiveness and anti-corruption should be prioritised before democratisation of control of the police. This may help to insulate a police organisation from external influences, for example, ensuring that payment of ordinary officers is sufficient and, along with recruitment and promotion, decided on the basis of legal-rational rules rather than personal connections (Transparency International Citation2012). But, again, this also runs the risk of strengthening a regime’s coercive capacity, which it may use for non-democratic ends.

The contrasting patterns of reform nevertheless suggest that successful reform outside the former Soviet Union may also require enhancements in state capacity and a focus on anti-corruption. Even in a hybrid model, for policing to be democratic requires some sort of democratic authority. Sub-national authorities may be democratic but for democracy or democratic policing to be sustained likely requires a national democratic body with authority. In practice, a focus on anti-corruption outcomes may also be more impactful than emphasising democratisation of reform processes. Few people will participate in the latter and wide democratisation can open up opportunities to block reform. Effective anti-corruption measures can mitigate the costs paid by a wider population and, by contrast, have a far-reaching effect.

These lessons must though be treated with caution. Partial success in Georgia may have depended on factors specific to the country. Georgia is small and relatively homogeneous, which facilitated a single neo-patrimonial network to dominate the state. In a larger, more diverse context, such an approach may instigate elite or broader societal conflict. As per the hybrid-governance school, a reform process which regulates diverse forms of policing but is less centralised than Georgia, may have a better chance of producing democratic outcomes, though will likely require a political settlement/elite pacting that provides stability and a focus on such outcomes. Such arrangements can though introduce more opportunities to block reform where a government is limited in its ability to tackle corruption at the risk of undermining the settlement/pact (Nasuti Citation2016). Georgia also only provides an example of partial institutionalisation. Though they have been sustained for nearly 20 years at lower levels, the reforms have not been institutionalised in a legal-rational framework at upper levels, which leaves them vulnerable should a new regime be formed with a greater tolerance for corruption.

More empirical evidence is required to draw firm conclusions around whether to prioritise anti-corruption or democratisation in police reform. We currently though have few empirical examples of success, based on any of the approaches discussed. Improving DPR requires a better understanding of what political conditions are conducive to both partial and full DPR and how these conditions may be engendered, underpinned by multiple empirical examples and robust comparative frameworks. This paper provides an initial comparative framework to help explain the main factors affecting policing and police reform in low state capacity, authoritarian and neo-patrimonial contexts. It also suggests DPR may be dependent on increasing state capacity and political elites with the inclination and capability to counter corruption, based on the Georgian case. Georgia along with Singapore and Hong Kong provide empirical examples of rapid, large-scale, sustained reforms in non-democratic or hybrid contexts (and, for Georgia, a low state capacity one). Though such cases are few they are greater in number than cases based on other models. A further challenge is to determine how the contributions of these can be incorporated to produce effective and sustainable reforms at scale.

Geolocation information

Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Russia; Former Soviet Union; Global South.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Georgian Institute for Strategic Studies (Georgia), the American University of Central Asia (Kyrgyzstan) and the Centre for Independent Social Research (Russia) for hosting him as a Visiting Fellow and all the participants who offered interviews for the project. He would also like to express his gratitude to Dr Alexander Kupataze (Kings College London), Dr Milli Lake (London School of Economics), Prof James Sheptycki (York University) and colleagues from the LSE Security and Statecraft Cluster for reviewing earlier drafts of this paper.

Ethical approval

The fieldwork which forms the basis of this study was granted ethical approval by the University of St Andrews International Relations School Ethics Committee in November 2010 (IR6950).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Mailhot et al. (Citation2022).

2 Goldsmith and Dinnen (Citation2007), Wozniak (Citation2018).

3 Wozniak (Citation2018), McAuliffe (Citation2021).

4 Baker (Citation2010).

5 Ryan (Citation2011).

6 Bayley (Citation1990), Greitens (Citation2016).

7 Taylor (Citation2011), Jauregui (Citation2016), Beek et al. (Citation2017), Marat (Citation2018), Malik and Qureshi (Citation2020), González (Citation2020).

8 Volkov (Citation2002), Dupont et al. (Citation2003), Gerber and Mendelson (Citation2008), Hills (Citation2020).

9 Because of crackdowns on civil society in Russia and Kyrgyzstan since 2010, and especially in Russia since the invasion of Ukraine, I have anonymised the names of a large proportion of respondents.

10 Mann uses the term ‘despotic’.

11 Adapted from: Jones et al. (Citation1996), Bajraktari et al. (Citation2006).

12 From the Russian: Ministerstvo Vnutrennikh Del.

13 Anonymous, Former MP, Bishkek (May 2011); Anonymous, Senior NGO official 1, Bishkek (April 2011); Former Colonel, Directorate of Criminal Investigations, 25 years+ service, Kyrgyzstan (May 2011); Anonymous, Former MP, Kyrgyzstan (May 2011).

14 Gladarev (Citation2011). Conversion based on historical average conversion rates (2009): http://fxtop.com/en/historates.php

15 Figure is adjusted to provide for inflation: http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl

16 See also Taylor (Citation2011).

17 Chzhen (Citation2010).

18 Major-General Melis Turganbaev, Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs (2008–2014), Bishkek (May 2011); Anonymous, Captain, Department of Social Order, 20 years service, Kyrgyzstan (May 2011); Anonymous, Praporshchik (most senior lower officer rank), GAI, 15 years service, Kyrgyzstan (May 2011); Anonymous, Captain, MVD Academy, 9 years service, Kyrgyzstan (May 2011).

19 Anonymous, Senior NGO official 1, Bishkek (April 2011); Encounter, Anonymous, Taxi driver, Bishkek (April 2011).

20 Anonymous, Senior NGO official 1, Bishkek (April 2011); Anonymous, NGO official 1, Osh (May 2011); Anonymous, NGO official 2, Osh (May 2011).

21 Anonymous, Senior NGO official 2, Bishkek (May 2011).

22 Anonymous, Police Chief, Tbilisi (August 2011).

23 David Darchiashvili, Former Chairman of the parliamentary Committee on European Integration/Ilia State University, Tbilisi (August 2011).

24 The Federal Security Service (Federal'naya sluzhba bezopasnosti), successor agency to the KGB.

25 David Aprasidze, Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi (August 2011); Ekaterine Tkeshelashvili, Former State Minister for Reintegration/Deputy Prime Minister of Georgia, Tbilisi (August 2011).

26 Anonymous, Former Lieutenant, Directorate of Criminal Investigations, 5 years service, Kyrgyzstan (May 2011).

27 Anonymous, Praporshchik (most senior lower officer rank), GAI, 15 years service, Kyrgyzstan (May 2011).

28 Anonymous, OSCE official, Kyrgyzstan (May 2011). The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe has provided small-scale police assistance in Kyrgyzstan since 2003.

29 Anonymous, Police Chief, Tbilisi (August 2011).

30 For an earlier discussion on this, see Kakachia and O’Shea (Citation2012).

31 Anonymous, Senior NGO official 1, Bishkek (April 2011); Former Colonel, Directorate of Criminal Investigations, 25 years+ service, Kyrgyzstan (May 2011); Anonymous, Former MP, Kyrgyzstan (May 2011).

32 Interview, Anonymous, Former Lieutenant, Directorate of Criminal Investigations, 5 years service, Kyrgyzstan (May 2011).

33 Interviews: Anonymous, Academic, St. Petersburg (September 2010); Boris Pustintsev, Director, Citizens’ Watch (NGO) (September 2010); Yakov Gilinskiy, Professor, St. Petersburg Law Institute, St. Petersburg (October 2010).

34 Radio Free Europe (Citation2006).

35 Interview, Anonymous, Senior NGO official, Moscow (October 2010).

36 Galeotti (Citation2012).

37 Semukhina and Reynolds (Citation2013).

38 Kakachia and O’Shea (Citation2012), O’Shea (Citation2014, Citation2022). Shota Utiashvili, Information and Analytical Department, Ministry of Interior (Georgia), Tbilisi (August 2011).

39 Marten (Citation2012).

40 Bolkvadze (Citation2017).

41 World Bank (Citation2012).

42 Darchiashvili (Citation2008).

43 Boda and Kakachia (Citation2005), Kukhianidze (Citation2006), Light (Citation2014).

44 Darchiashvili (Citation2003), Transparency International (Citation2007). Conversions are based on historical average conversion rates (annual): http://fxtop.com/en/historates.php

45 Boda and Kakachia (Citation2005).

46 Kukhianidze et al. (Citation2006), Kupatadze (Citation2012), Slade (Citation2012).

47 Anonymous, Detective, 7 years service, Georgia (August 2011).

48 CRRC (Citation2021), IRI (Citation2021a, Citation2021b).

49 O’Shea (Citation2022).

50 Ross (Citation2010).

References

- Andersen, L., 2007. What to do? The dilemmas of international engagement in fragile states. In: L. Andersen, B. Møller, and F. Stepputat, eds. Fragile states and insecure people? Violence, security, and statehood in the twenty-first century. Hampshire, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 21–43.

- Andersen, L., 2012. The liberal dilemmas of a people-centred approach to state-building. Conflict, security & development, 12 (2), 103–121.

- Areshidze, I., 2007. Democracy and autocracy in Eurasia: Georgia in transition. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

- Aprasidze, David, and Siroky, David S., 2020. Technocratic populism in hybrid regimes: Georgia on my Mind and in my pocket. Politics and Governance, 8 (4), 580–589. http://dx.doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i4.3370

- Bajraktari, Y., et al. 2006. The PRIME system: measuring the success of post-conflict police reform. Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, 208–228.

- Baker, B., 2010. The future is non-state. In: M. Sedra, ed. The future of security sector reform. Ontario: Centre for International Governance Innovation.

- Bayley, D.H., 1990. Patterns of policing: a comparative international analysis. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Bayley, D.H., 2005. Changing the guard: developing democratic police abroad. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Bayley, D.H., and Perito, R., 2010. The police in war: fighting insurgency, terrorism, and violent crime. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Beck, A., and Robertson, A., 2005. Policing in post-Soviet Russia. In: W.A. Pridemore, ed. Ruling Russia: Law, crime, and justice in a changing society. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 247–260.

- Beek, J. (Ed.) et al. 2017. Police in Africa: The street level view. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Boda, J., and Kakachia, K., 2005. The current status of police reform in Georgia. In: P.H. Fluri, and E. Cole, eds. From revolution to reform: Georgia’s struggle with democratic institution building and security sector reform. Geneva: DCAF, Chapter 12.

- Bolkvadze, K., 2017. Hitting the saturation point: unpacking the politics of bureaucratic reforms in hybrid regimes. Democratization, 24 (4), 751–769.

- Burnham, W., and Kahn, J., 2008. Russia’s criminal procedure code five years out. Review of central and eastern European Law, 33, 1–93.

- Chzhen, Y., 2010. Child poverty in Kyrgyzstan: analysis of the 2008 household budget survey. UNICEF / University of York Social Policy Research Unit, Working Paper EC 2410.

- Colletta, N.J. and Muggah, R., 2009. Context matters: interim stabilisation and second generation approaches to security promotion. Conflict, security & development, 9 (4), 425–453.

- CRRC. 2021. Caucasus Barometer 2008-21 - Georgia [online]. Available from: https://caucasusbarometer.org/en/datasets/ [Accessed 18 May 2022].

- Darchiashvili, D., 2003. Power structures, the weak state syndrome and corruption in Georgia. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.

- Darchiashvili, D., 2008. Security sector reform in Georgia 2004-2007. Tblisi: Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy and Development.

- Darchiashvili, D., and Mangum, R.S., 2019. Georgian civil-military relations: hostage to confrontational politics. Caucasus survey, 7 (1), 79–93.

- Dawisha, K., 2015. Putin’s Kleptocracy: Who owns Russia? New York: Simon & Schuster.

- DCAF, 2019. The police. SSR backgrounder series. Geneva: Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance.

- De Waal, T., 2010. The Caucasus: an introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dupont, B., Grabosky, P., and Shearing, C., 2003. The governance of security in weak and failing states. Criminal justice, 3 (4), 331–349.

- Ellison, G., and Pino, N., 2012. Globalization, police reform and development: doing it the western Way? Hampshire, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Engvall, J., 2022. Kyrgyzstan’s poison parliament. Journal of democracy, 33 (1), 55–69.

- Erdmann, G., and Engel, U., 2007. Neopatrimonialism reconsidered: critical review and elaboration of an elusive concept. Commonwealth & comparative politics, 45 (1), 95–119.

- Fritz, A., 2005. Security sector governance in Georgia (I): status. In: P.H. Fluri and E. Cole, eds. From revolution to reform: Georgia’s struggle with democratic institution building and security sector reform. Geneva: DCAF, Chapter 2.

- Galeotti, M., 2010. Terrorism, crime, and the security forces. In: M. Galeotti, ed. The politics of security in modern Russia. Surrey: Ashgate, 123–144.

- Galeotti, M., 2012. Purges, power and purpose: Medvedev’s 2011 police reforms. The journal of power institutions in post-soviet societies. Pipss.org (Issue 13). https://journals.openedition.org/pipss/3813

- Gel’man, V., 2021. Constitution, authoritarianism, and bad governance: the case of russia. Russian politics, 6 (1), 71–90.

- Gerber, T.P., and Mendelson, S.E., 2008. Public experiences of police violence and corruption in contemporary Russia: a case of predatory policing? Law & society review, 42, 1–44.

- Gladarev, B., 2011. Osnovnye printsipy i usloviia raboty militsii obshchestvennoi bezopasnosti. In: V. Voronkov, B. Gladarev, and L. Sagitova, eds. Militsiia i etnicheskie migranty: Praktiki vzaimodeistviia. St. Petersburg: Aletheia, 97–135.

- Gladarev, B., 2012. Russian police before the 2010-2011 reform: a police officer’s perspective. The journal of power institutions in post-soviet societies. Pipss.org (Issue 13).

- Gladarev, B., and Tsinman, S., 2011. Povysilis’ li ‘Migratsionnaia Privlekatel’nost’’ Rossii? Analiz vzaimodeistviia sotrudnikov militsii i FMS s migrantami posle izmenenii migratsionnogo zakonodatel’stva. In: V. Voronkov, B. Gladarev, and L. Sagitova, eds. Militsiia i Etnicheskie Migranty: Praktiki Vzaimodeistviia. St. Petersburg: Aletheia, 508–564.

- Glasius, M., 2018. What authoritarianism is … and is not: a practice perspective. International affairs, 94 (3), 515–533.

- Goldsmith, A., and Dinnen, S., 2007. Transnational police building: critical lessons from Timor-Leste and Solomon Islands. Third world quarterly, 28 (6), 1091–1109.

- González, Y.M., 2020. Authoritarian police in democracy: contested security in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gordon, E., 2014. Security sector reform, statebuilding and local ownership: securing the state or its people? Journal of intervention and statebuilding, 8 (2–3), 126–148.

- Greitens, S.C., 2016. Dictators and their secret police: coercive institutions and state violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hendley, K., 2010. The Law in post-Putin Russia. In: S.K. Wegren and D.R. Herspring, eds. After Putin’s Russia: past imperfect, future uncertain. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 83–108.

- Hensell, S., 2012. The patrimonial logic of the police in Eastern Europe. Europe-Asia studies, 64 (5), 811–833.

- Hills, A., 2020. The dynamics of prototypical police forces: lessons from two Somali cities. International affairs, 96 (6), 1527–1546.

- IRI. 2021a. Georgia National Voter Study, 2003–2007.

- IRI. 2021b. Georgia National Study 2008–2012.

- Jauregui, B., 2016. Provisional authority: police, order, and security in India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Jones, S., 2013. Georgia: a political history since independence. London, NY: I.B.Tauris.

- Jones, T., Newburn, T., and Smith, D.J., 1996. Policing and the idea of democracy. British journal of criminology, 36 (2), 182–198.

- Kakachia, K., and O’Shea, L., 2012. Why does police reform appear to have been more successful in Georgia than in Kyrgyzstan or Russia? The journal of power institutions in post-soviet societies (Issue 13).

- Knight, A.W., 1996. Spies without cloaks: the KGB’s successors. New Brunswick: Princeton University Press.

- Kukhianidze, A. 2006. Korruptsiia i prestupnost’ v Gruzii posle ‘Rozovoi’ revoliutsii [Corruption and Crime in Georgia after the Rose Revolution; Russian].

- Kukhianidze, A., 2003. Managing international and inter-agency cooperation at the border. Working group on the democratic control of internal security services of the Geneva centre for the democratic control of Armed Forces March 13–15 Geneva.

- Kukhianidze, A., Kupatadze, A., and Gotsiridze, R., 2006. Smuggling in Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali Region in 2003 - 2004. In: L. Shelley, E.R. Scott, and A. Latta, eds. Organized crime and corruption in Georgia. London: Routledge, 69–92.

- Kupatadze, A., 2008. Organized crime before and after the tulip revolution: the changing dynamics of upperworld-underworld networks. Central Asian survey, 27 (3), 279–299.

- Kupatadze, A., 2012. Organized crime, political transitions and state formation in post-soviet Eurasia. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kupatadze, A., Siradze, G., and Mitagvaria, G., 2006. Policing and police reform in Georgia. In: L. Shelley, E.R. Scott, and A. Latta, eds. Organized crime and corruption in Georgia. London: Routledge, 93–110.

- Lewis, D., 2011. Reassessing the role of OSCE police assistance programming in Central Asia, Central Eurasia Project Occasional Paper Series, No. 4.

- Light, M., 2014. Police reforms in the republic of Georgia: the convergence of domestic and foreign policy in an anti-corruption drive. Policing and society, 24 (3), 318–345.

- Mailhot, C., Kriner, M., and Karim, S., 2022. International involvement in (Re-)building police forces: a comparison of US and UN police assistance programs around the world. Small wars & insurgencies, 1–27.

- Malik, N., and Qureshi, T.A., 2020. A study of economic, cultural, and political causes of police corruption in Pakistan. Policing: A journal of policy and practice, 1–17.

- Manion, M., 2004. Lessons for mainland China from anti-corruption reform in Hong Kong. China review, 4 (2), 81–97.

- Mann, M., 1986. The autonomous power of the state: its origins, mechanisms, and results. In: J.A. Hall, ed. States in history. Oxford, NY: Blackwell, 109–136.

- Marat, E., 2010. Kyrgyzstan’s fragmented police and armed forces. The journal of power institutions in post-soviet societies (Issue 11).

- Marat, E., 2013. Reforming the police in post-soviet states: Georgia and Kyrgyzstan. Carlisle PA: Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press.

- Marat, E., 2018. The politics of police reform: society against the state in post-soviet countries. New York, NY: OUP USA.

- Marat, E., and Isa, D., 2010. Kyrgyzstan relaxes control over drug trafficking. Eurasia daily monitor, 7 (24).

- March, L., 2012. Nationalism for export? The domestic and foreign-policy implications of the New ‘Russian idea’. Europe-Asia studies, 64 (3), 401–425.

- Marten, K., 2012. Warlords: strong-arm brokers in weak states. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- McAuliffe, P., 2021. The conceptual–contextual gap between non-recurrence and transformative police reform in post-conflict states. Policing: A journal of policy and practice, 15 (1), 1–14.

- Nasuti, P., 2016. Administrative cohesion and anti-corruption reforms in Georgia and Ukraine. Europe-Asia studies, 68 (5), 847–867.

- O’Shea, L. 2014. Police reform and state-building in Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Russia. Thesis. University of St Andrews.

- O’Shea, L., 2015. Informal economic practices within the Kyrgyz police (militsiya). In: J. Morris and A. Polese, eds. Informal economies in post-socialist spaces. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 270–293.

- O’Shea, L., 2022. Democratic police reform, security sector reform and spoilers: lessons from Georgia. Conflict, security & development., Forthcoming

- Özsoy, I., 2007. Human transformation in the transition economies – the case of Georgia. Journal of east-west business, 12 (4), 71–103.

- Peacock, R., 2021. Bayley’s six critical elements of democratic policing: evaluating donor-assisted reform in Armenia, Georgia, and Ukraine. International journal of comparative and applied criminal justice, 45 (3), 1–13.

- Quah, J., 2014. Curbing police corruption in Singapore: lessons for other Asian countries. Asian education and development studies, 3 (3), 186–222.

- Radio Free Europe. 2006. Corruption scandal could shake Kremlin [online]. Available from: http://www.rferl.org/content/article/1071621.html [Accessed 2 Mar 2022].

- Radio Free Europe. 2007. Russia: as elections near, rivalries In Putin circle heat up [online]. Available from: http://www.rferl.org/content/article/1078960.html [Accessed 2 Mar 2022].

- Ross, C., 2010. Federalism and inter-governmental relations in russia. Journal of communist studies and transition politics, 26 (2), 165–187.

- Ryan, B., 2011. Statebuilding and police reform: the freedom of security. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Saeed, R., 2020. The ubiquity of state fragility: fault lines in the categorisation and conceptualisation of failed and fragile states. Social & legal studies, 29 (6), 767–789.

- Sakwa, R., 2010. Political leadership. In: S.K. Wegren and D.R. Herspring, eds. After Putin’s Russia: past imperfect, future uncertain. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 17–38.

- Sakwa, R., 2011. The crisis of Russian democracy: the dual state, factionalism, and the Medvedev succession. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Salagaev, A., Shashkin, A., and Konnov, A., 2006. One hand washes another: informal ties between organized criminal groups and law-enforcement agencies in Russia. The journal of power institutions in post-soviet societies (Issue 4/5).

- Semukhina, O.B., and Reynolds, K.M., 2013. Understanding the modern Russian police. London: CRC Press.

- Shahnazarian, N., and Light, M., 2018. Parameters of police reform and non-reform in post-soviet regimes: the case of Armenia. Demokratizatsiya: The journal of post-soviet democratization, 26 (1), 83–108.

- Shelley, L., 1996. Policing soviet society: the evolution of state control. New York: Routledge.

- Skocpol, T., 1985. Bringing the state back in: strategies of analysis in current research. In: P.B. Evans, D. Rueschemeyer, and T. Skocpol, eds. Bringing the state back in. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press, 3–43.

- Slade, G., 2012. Georgia’s war on crime: creating security in a post-revolutionary context. European security, 21 (1), 37–56.

- Solomon, P., 2008. Law in public administration: how Russia differs. Journal of communist studies and transition politics, 24 (1), 115–135.

- Stabilisation Unit. 2019. The UK’s approach to stabilisation.

- Taylor, B.D., 2011. State building in Putin’s Russia: policing and coercion after communism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Taylor, B.D., 2014. Police reform in Russia: the policy process in a hybrid regime. Post-Soviet affairs, 30 (2–3), 226–255.

- Temirkulov, A., 2010. Kyrgyz “revolutions” in 2005 and 2010: comparative analysis of mass mobilization. Nationalities papers, 38 (5), 589–600.

- Timoshenko, S., 1997. Prospects for reform of the Russian militia. Policing and society, 8 (1), 117–124.

- Transparency International. 2007. Budgetary priorities in Georgia: Expenditure dynamics since the Rose Revolution.

- Transparency International. 2012. Arresting corruption in the police – the global experience of police corruption reform efforts.

- Uzakbaev, T., 2009. ESCAS XI conference 2009. Studying central Asia: in quest for new paths and concepts?. 3–5 September. Central European University, Budapest, Hungary.

- Volkov, V., 2002. Violent entrepreneurs: the Use of force in the making of Russian capitalism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Wheatley, J., 2005. Georgia from national awakening to rose revolution: delayed transition in the former soviet union. Hampshire: Ashgate.

- World Bank, 2002. Georgia poverty update. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- World Bank, 2012. Fighting corruption in public services: chronicling Georgia’s reforms. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

- World Bank. 2022. World development indicators [online]. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator [Accessed 3 Mar 2022].

- Wozniak, J.S., 2017. Iraq and the material basis of post-conflict police reconstruction. Journal of peace research, 54 (6), 806–818.

- Wozniak, J.S., 2018. Post-conflict police reconstruction: major trends and developments. Sociology compass, 12 (6).