ABSTRACT

While many benefits of women in policing have been recognised, sworn female officers have remained mostly underrepresented within the workforce. Recently, policing organisations have sought to rectify this with the implementation of gender targets. However, this aim to increase female officers has been met with resistance and scepticism. This study examines the main support and concerns held by the public regarding women in policing. To do this, 3562 phrases within 3210 public comments were thematically analysed from an Australian Federal Police Facebook recruitment campaign that targeted women. Results showed that most of the comments were positive in nature with three main themes emerging: individual, institutional, and societal perspectives. Furthermore, the findings revealed that there appears to be a shift in public opinions from individual perspective concerns (such as emotional and physical capabilities) to a societal perspective including the balancing of power and the breaking of chains. These findings help to inform policing authorities in the design of gender target campaigns and strategies. Specifically, by knowing the public concerns about women in policing, authorities can address these concerns by rethinking policies and practices, and educating the public about any common misconceptions about female officers. Furthermore, the supportive reasons can be used to promote positive relationships between police and the community enhancing trust and confidence in the police.

Policing agencies have recently recognised the benefits of having sworn female officers in their workforce and have set recruitment targets to achieve a more equal gender representation (Ward et al Citation2021). For example, in the United States, the New York University 30 × 30 initiative aims to increase the representation of female officers nationally to 30%; by 2030 (New York University School of Law Citation2021). In the UK, the Metropolitan Police aspire to meet 50%; female recruitment targets from 2022 onwards (Metropolitan Police Citation2021). In Australia, all state/territory and federal police organisations have engaged in some form of gendered recruitment or advertising to boost the representation of female officers (Ward et al. Citation2021). For example, in November 2015, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) Commissioner announced targets to have 50%; female employees across the organisation by 2026 (Broderick Citation2016, Ward et al. Citation2021) with 35% sworn female officers by 2028 (AFP Citation2018).

However, the sudden increase in female officers in some jurisdictions has met with resistance and scepticism by the public. Ward et al. (Citation2021) identified that both officers and citizens have voiced concerns in response to targeted recruitment campaigns, including the undermining and charity-case status of women that gender targets insinuate, and allegations of reverse sexism and reductions in standards of recruits. Such negative consequences have recently arisen in Australia. Allegations of promoting underqualified females to meet gender targets has ignited public debate centered on the use of gender quotas, discrimination against male applicants, and the eligibility of females to perform the policing role (Crime and Corruption Commission Citation2021).

Recognising and responding to public concerns becomes increasingly important if policing organisations hope to remain legitimate in the eyes of those police. Reinforcing public trust and confidence in police are particularly important now, given the upsurge of civil unrest globally (Institute for Economics and Peace Citation2020) and the declining perceived trustworthiness of Australian criminal justice institutions (Biddle Citation2022). This article aims to identify the current public opinions of female officers in an Australian context including both the public’s concerns and their support of women in policing.

Gender targets in policing

Research commissioned by the British Association of Women police proposes that a minimum representation of 35% policewomen are needed for the cultural integration of women and the benefits of gender diversity to take effect. Stemming from Kanter’s (Citation1977) theory of tokenism, this numerical tipping point allows minority groups enough power and leverage to create positive change within the larger group. Therefore, increasing the representation of women in policing not only serves to benefit the community and the wider organisation, but it also allows women to make cultural changes within policing organisations which protects them from discrimination and other social, psychological, and physical harms.

Despite the rapid growth of women policing during the twentieth century in western democratic countries, growth in the past decade has become stagnate. Currently, the proportion of female sworn officers is approximately 25% (Prenzler and Sinclair Citation2013). Australia is not different with women generally representing only 22–32% of sworn officers in Australia (Northern Territory Police, Fire & Emergency Services Citation2020, South Australia Police Citation2020, Victoria Police Citation2020, Western Australia Police Force Citation2020).

In terms of recruitment strategies for females, approaches around the world have included adjustments to selection criteria, such as gendered fitness assessments to reduce the physical advantages male recruits enjoy, and female-focused advertising, women-only information and orientation sessions, and female mentoring (Home Office Citation2010; Ward et al. Citation2021). These tactics are often used in Australia as well. In Australia, there has been a dominance of passive measures to increase women in policing such as inclusive advertising, representative selection panels, increased rules and training to address discrimination and harassment, and workshops that promote flexible employment to appeal to women (Ward et al. Citation2021).

The benefits of female officers

Researchers have identified many benefits of women in policing. The majority of the research focuses on examining whether sworn female officers can perform the role of a police officer. This body of research consistently finds that women are not only capable police officers, but including women as sworn officers has practical and positive implications for communities and policing organisations (Prenzler and Sinclair Citation2013, Prenzler Citation2015, Broderick Citation2016, Ashlock Citation2019, Brown and Silvestri Citation2020). In general, previous research has focused on three main perspectives for the benefits of female officers in the workforce; individual, institutional, and societal.

Individual perspectives

At the individual perspective, women in policing research mostly take a social psychological approach regarding the interpersonal skills of policewomen and their ability to deal with citizens. Findings show that compared to their male counterparts, female police officers are more empathetic and rely more on effective communication skills which, in turn, strengthens their de-escalation skills defusing potentially violent situations and reduces the need for force (Muir Citation1977, Koenig Citation1978, McDowell Citation1992, Brereton Citation1999; Brown and Heidensohn Citation2000, Rabe-Hemp Citation2008). Subsequently, policewomen receive less citizen complaints for their conduct (Brown and Silvestri Citation2020, Schuck Citation2014a). Further, because of their greater capacity to show compassion and empathy towards community members, women are widely thought to respond more effectively to sensitive crimes such as domestic and family violence, crimes against children or vulnerable persons, as well as victims of sexual violence and assault (Kerber et al. Citation1977, Natarajan Citation2008, Rabe-Hemp Citation2008, Independent Police Commission Citation2013, Broderick Citation2016, Brown Citation2016).

Cumulatively, female officers’ communication, interpersonal skills, and proclivity for procedural justice measures (Rabe-Hemp Citation2008, Hellwege et al. Citation2021) tend to make them better equipped for community-oriented policing which has become one of the most desired policing approaches by policing agencies (Fleming Citation2010, Sarre and Prenzler Citation2018, Hine and Davenport-Klunder Citation2022). When communities believe that police are procedurally just, they are more likely to perceive police as legitimate and therefore comply with police orders (Tyler Citation2004, Hinds and Murphy Citation2007). Thus, it is essential to understand the communities’ opinions about female officers.

Institutional perspectives

Women in policing can have positive impacts on institutional dynamics and operational capacity. An increase in diversity increases creativity (Marinova et al. Citation2010), collective intelligence (Woolley and Malone Citation2011), problem-solving capacity (Williams Woolley et al. Citation2010), positive cultural change (Broderick Citation2016), and decreases incidents of sexism and sexual harassment (Sojo and Wood Citation2012). Even by their mere presence, women can serve as catalysts for positive cultural change by challenging those hegemonic structures which uphold patriarchal and damaging dynamics of power (Rabe-Hemp and Miller Citation2018). Further, the increased presence of women in institutions of power has been shown to reduce engagement with corruption and corrupt practices (Grimes and Wängnerud Citation2010; Rothstein Citation2017). Therefore, not only do female officers influence police practice at the individual level, but they also further perpetuate positive change at the institutional level.

Policing agencies require female police officers within the workforce for practical reasons. Female perpetrators should be able to request body searchers by a same-sex officer (Natarajan Citation2008) and female victims should also be able to request a same-sex officer, especially for sensitive crimes such as sexual violence (Kennedy and Hormant Citation1983, National Centre for Women and Policing Citation2002). Further, governing bodies should be representative of the communities they serve. Representative bureaucracy can facilitate cooperation, trust, and participation with citizens in ways that non-representative police forces cannot (Krislov and Rosenbloom Citation1981, Kim Citation1994, Schuck Citation2014b, Rabe-Hemp and Miller Citation2018). Increasing the diversity of gender, as well as sexual, cultural, religious, linguistic, and experiential diversity in the police force, serves as a connection between the police and their community. This equips police organisations with broader skills, understanding, empathy, and a diversity of policing styles to meet community needs in ways that traditionally white, male-dominated organisations cannot.

Societal perspectives

There are also broader positive societal impacts from an increase of women in policing. Policing offers a unique and exciting career opportunity which provides financial stability and independence for the rapidly growing female labour market (Broderick Citation2016). Policing offers interesting, dynamic, financially secure work for women, and allows women to contribute their expertise and skills to improving security and prosperity (Broderick Citation2016). Further, employing more women, particularly into leadership roles, has a positive cultural impact for all women in society (Sojo and Wood Citation2012). Seeing successful women in leadership positions motivates younger, or lower ranking, women to succeed which further promotes gendered equality in society (Desveaux et al. Citation2010).

Women in policing can also impact positively on community perceptions of police legitimacy. Societal cohesion can occur when organisations maintain legitimacy with the community and police benefit from enhanced public cooperation, better community relations, obedience, and increased reporting of crime (Tyler Citation1990, Citation2003, Córdova and Kras Citation2019, Shjarback and Todak Citation2019, Brown and Silvestri Citation2020, Hellwege et al. Citation2021). Córdova and Kras (Citation2019) even suggest that increasing perceptions of police legitimacy amongst women could contribute to increased reporting of gender-based and family violence. Given the criticism of hegemonic and masculine responses to gendered violence, combined with the ‘insider’ status that policewomen hold when interacting with female victims (Carrington et al. Citation2020), including more women in Australian police organisations could promote reporting and provide a pathway to combatting the longstanding issue of violence against women in Australia.

Key concerns

Despite these many benefits of female officers in the workforce, there remain some key concerns. The majority of these concerns stem from biological and social-psychological perspectives. Historically, the public and male police officers have questioned the physical ability of women to perform the duties required in the policing role (Bell Citation1982, Grennan Citation1987, Balkin Citation1988, Martin Citation1989, Breci Citation1997). Women have also been stereotyped as lacking the emotional and psychological capacity to handle the demands of police work (Sherman Citation1975). Emotionality has been associated with women being irrational, compassionate, cooperative, physically fragile, subjective, and gentle (Garcia Citation2003). Further, stereotypical ideals of women as warm and nurturing clash with expectations of police officers as authoritative, brave, aggressive, rational, and objective (Carli Citation2001; Garcia Citation2003; Miller Citation1999). Indeed, Morash (Citation1986) and Breci (Citation1997) found that the public believe that women do not have the authoritarian presence to manage violent confrontations.

A second pronounced concern is the unstable and unsupported rise of women in the labour market more generally. ‘Feminization’ of workforces has received heavy criticism from academics such as Bolton & Muzio (Citation2008), who identify the paradoxical relationship between increasing female participation in the labour market with the de-professionalisation of those fields or sub-fields in which women dominate. Here, the performative demand for female participation seemingly cheapens the prestige of the field, causing unintended consequences such as undermining, undervaluing, and de-professionalising the role and the women in those fields (Bolton and Muzio Citation2008; Silvestri, et al. Citation2013).

Overall, previous literature has highlighted that the majority of concerns lie at the individual-level of the physical and psychological limitations associated with the stereotypical view of women being less capable of performing a traditional male role. Subsequently, when women are included in the workplace, it can result in women being undermined by this perceived general view of a woman’s lack of capability. Hence, it is important to understand the public’s opinion of professional woman in male-dominated fields in order to address these concerns and rectify any misconceptions.

Public opinion

Understanding public opinions of police are critical to build and maintain a positive public opinion and maintain police legitimacy. Maintaining police legitimacy not only increases approval of police, but also positive relationships between the community and the police allow officers to do their job as effectively as possible. Indeed, Reiner (Citation2003) posits that policing is as much symbolism as it is substance. Public confidence in police, and therefore the legitimacy of police, rests just as much on what the police are perceived to be doing as what they are actually doing (Lee and McGovern Citation2013). Research suggests that citizens are more likely to obey the law and cooperate with police officers if they perceive the police as ‘legitimate’ and believe that police act in a procedurally fair manner (Tyler Citation2003, Sarre and Prenzler Citation2018, Bolger and Walters Citation2019, Bolger et al. Citation2021). Indeed, the police have become one of the most intently observed institutions by the public, government, and authorities in modern society (Mawby Citation2002).

Public opinion of female officers

The public’s opinion of women in policing is both under researched and outdated. Current understandings of public perceptions of female officers are mostly derived from two US studies in the 1990s. Both studies employed telephone surveys to investigate public opinions of female police on patrol. Leger (Citation1997) surveyed 200 people to find an overall positive perception of female officer ability – apart from the ability to handle violent situations. Breci (Citation1997) surveyed 702 people to find that most respondents found female officers to be as effective as male officers, particularly in situations involving children and family disputes. Combined, these findings suggest a generally positive attitude by the United States' public towards women in policing during the 1990s.

More recent research has examined the public’s opinion of women in other male-dominated spaces such as the military. Attempts to increase inclusion for women in the military has been met with resistance and unintended consequences. For example, in late 2011, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) command and Australian government removed all gender barriers to employment which had previously barred women from joining male-specific and combat roles (Wadham and Citation2018). However, the increase of women into the defence force over the prior decades had slowly undone the ‘hermetically sealed fraternity’ of the ADF, with controversies around sexual harassment, assault, misogyny, and sexism, inciting public outcry, intense media scrutiny, and internal inquiries by the ADF (Wadham et al. Citation2018). Many of the arguments against women’s inclusion in the ADF echo the previous arguments against, and increase of, women in policing; women as weaker, softer, peaceful, domestic, passive, and life-giving (Wadham et al. Citation2018). Indeed, Laurence and colleagues (Citation2016) found that those holding more conservative values were more likely to support the maintenance of tradition, that being the exclusion of women from battle and combat roles. Conflict surrounding the introduction of women into the Australian military may contribute significantly to the discourse surrounding women in policing, as the similarly ‘hermetically sealed fraternity’ of policing is challenged by the surge of female applicants.

While there is no current research examining the public’s opinion of women in Australian policing, recent events and media reports suggest that it is a hot and divisive topic. Aggressive tactics to increase female representation have included specific ratio recruitment targets, such as those 50/50 gender targets introduced by the AFP. These targets have triggered public discourse regarding discrimination against male candidates, the ability of female candidates, and the integrity of police recruitment practices (for example, see Nguyen & Inman Citation2017). However, the actual opinions of women in Australian policing remains unknown.

Since the original public opinion research on women in policing over 30 years ago, there have also been several topical social and cultural events which have presumably shaped opinions around women. For example, the Trump era and recent political debates surrounding abortion access, marriage equality, rape culture, and women’s rights has contributed to a retaliatory rise in conservatism, alt-right activism, and even a rise in ‘tradwife’ feminism around the world (Freeman Citation2020). These rising conservative views and values have been linked to resistance to change in times of stress and uncertainty (Jost et al. Citation2003), particularly when an individual perceives their beliefs to be under attack. If conservative Australians perceive an increase of female officers as a threat to their ideals of traditional heteronormativity, this could place a strain on the relationship between the community and female officers.

Other social movements involving themes of inequality and racism specifically focused on police-citizen interactions may have also influenced public opinions. While these are not directly related to women in policing, they may indicate general shifts in opinions about police and rising tensions between police and citizens. The unique skills that women bring to policing, most importantly their ability to connect with the community, may offer police organisations the opportunity to manage and mitigate poor police-community relations which have manifested as instances of civil unrest globally, with a steep rise in the past decade (Institute for Economics and Peace Citation2020). Hence, a more current understanding of the public’s opinion of women in policing is required that is more reflective of modern issues.

A contemporary approach to capturing public opinion

Traditional public opinion research has relied on telephone surveys and polling (see Breci Citation1997, and Leger Citation1997), however, these approaches tend to be outdated and limited. Blumer (Citation1948) argued that these traditional methods fail to accurately assess the nature of public opinions as they ask questions in an individual and private way. This neglects the public and social nature of public opinion. He argues that using traditional surveys to measure public attitudes fails to account for the hierarchical way society shapes opinions, and the control that elites have in opinion formation (Blumer Citation1948, Herbst Citation1998).

Public opinion produced through survey data has also long since rested on the notion that public opinion is defined by the largest number of people holding a particular opinion (Allport Citation1937). However, this ignores the opinions of minorities, which are opinions of growing importance through globalisation, particularly in a culturally diverse country like Australia. Polling and surveys continue to endure as the paradigmatic approach to collecting public opinion, however rising evidence suggests that response rates are declining, and reliability problems compound with the use of telephones, cellular phones, and internet polling (McGregor Citation2019).

An alternative and more contemporary approach to understanding public opinions is via the use of social media platforms. Social media offers a more public, relational, and temporally sensitive representation of public opinion (McGregor Citation2019). Indeed, the benefits of using social media to gain understandings of attitudes towards policing has been gaining popularity within the academic literature. For example, Bragais et al. (Citation2021) and Fleet and Hine (Citation2022) examined YouTube commentary to explore perceptions of police use of facial recognition technology. Additionally, Reddick, et al. (Citation2015) analysed Twitter content to understand public attitudes towards National Security Agency (NSA) mass surveillance programmes.

Of all the social media platforms, Facebook is perhaps the most used by the public. Facebook has approximately 2.85 billion users worldwide, including 11.4 million Australians (Statista Citation2021a, Citation2021b). The Yellow Social Media Report (Citation2020) surveyed Australian adult citizens and found that 89% of respondents use Facebook, with the average Australian spending eight hours on Facebook per week. This suggests that Facebook discourse is likely to capture a broader selection of public opinion due to its ability to provide insights that are not typically found in traditional methods and has the ability to reach a large number of people with a broad range of opinions (McGregor Citation2019, Yellow Citation2020).

The current study

Overall, knowledge and understandings of the public’s opinions of women in policing is outdated and limited. The current study aims to address this gap in knowledge by exploring social media users’ opinions of policewomen. Specifically, it examines whether these users are supportive or unsupportive of female officers. Of those that are supportive, the study aims to identify the supportive reasonings that these Facebook users’ hold toward women in policing. Conversely, for those that are unsupportive, the study aims to establish the main concerns that these Facebook users hold toward women in policing.

To do this, we examined public social media comments using the popular platform ‘Facebook’. Specifically, the current research will draw from public commentary posted to an Australian Federal Police (AFP) recruitment campaign that ‘unashamedly’ targeted potential female recruits. These 50/50 gender targets implemented by the AFP created significant professional and public debate around the idea of a ‘police officer’ in Australia, and how women can or cannot fit into this role. The findings will provide insights into the support for, or concerns of, increasing representation of women in Australian policing. Subsequently, these findings will help to inform policing authorities in designing gendered recruitment campaigns. Authorities may be able to reduce public concerns by rethinking policies and practices to be more aligned with acknowledging and addressing such concerns as well as educating the public about any common misconceptions. Additionally, public support can be used to promote relationships resulting in a more diverse workforce and enhancing public trust and confidence.

Methods

This study aimed to understand the social media users’ opinions of women police officers in Australia. Specifically, their reasons for supporting more women police officers in the workforce and the main concerns about women in Australian policing. To do this, data were captured from public commentary on the social media platform Facebook. Data were thematically coded and analysed to gain understandings of both the supportive reasonings and concerns for an increase of women police in Australia.

Data source

This study examined public commentary on a Facebook post by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) on September 28, 2017 (AFP Citation2017) (see Appendix 1). This post was selected due to its relevance and the public interest it provoked. The post promoted a recruitment campaign that ‘unashamedly’ targeted women in an attempt to achieve a 50% balance of female staff. This post received over 6000 reactions, 8100 comments, and 1600 shares, which evidenced noteworthy public interest. In comparison, a sample of 55 AFP Facebook posts taken between November 2020 and March 2021 showed average engagement metrics of only 2793.04 reactions, 761.91 comments, and 195.98 shares. The selected post showed significantly more user engagement, and also received local media attention for the public interest it provoked (Allen and Sibthorpe Citation2017, Nguyen and Inman Citation2017). Comment responses were harvested from this post to explore public opinions of women in Australian policing.

Data collection process

At the point of data collection, there were over 8100 public responses to the post. Due to Facebook technical limitations, only 5447 responses were collected for analysis. However, this still provides a large and robust sample size representing approximately 67%. Furthermore, the collected responses were those deemed ‘most relevant’ by Facebook’s inbuilt ‘Most Relevant’ algorithmic ranking system. The remaining uncollected responses received the least relevance according to the algorithm.Footnote1 The responses consisted of ‘comments’ and ‘replies’. Comments allow users to respond directly to the original post, most often in the form of text (Facebook Help Centre, Citation2022a). While there were 3117 comments, the data also consisted of 2330 ‘replies’.

Coding and analysis

A thematic analysis was conducted to explore the comments. Coding and theme development was conducted by both authors. During the theme development process, a coding dictionary was created. To establish inter-rater reliability, any comments that did not clearly align with the coding dictionary were discussed between authors until agreement was reached and the coding dictionary refined.

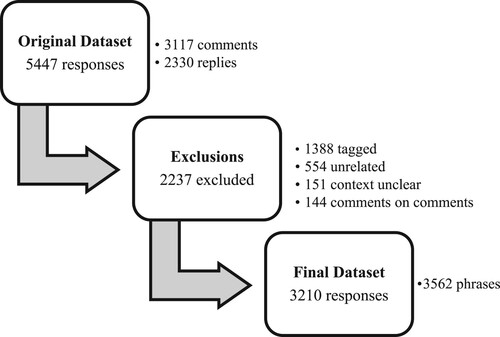

The initial systematic coding phase resulted in 2237 responses being excluded from the original data set of 5447 comments and replies (see ). These responses were excluded due to four reasons; the response was a tag and therefore contained no direct commentary on the topic, the response was unrelated to the topic of interest, the context was unclear and could not be coded, or the response was a comment about the commentary and not a direct commentary on the topic. This process resulted in 3210 responses consisting of 1621 comments and 1589 replies remaining for analysis.

Included responses contained phrases relevant to the broader topic of women, policing, and women in workplaces. Some responses contained multiple phrases which included both supportive phrases and concerned phrases, therefore, phrases were the unit of analysis.

To address the research question, phrases were categorised into supportive phrases and concerned phrases. Supportive phrases were those that demonstrated praise or support towards female officers, while concerned phrases were those that displayed anxiousness, worry, or distress about female officers. Within both the supportive and concerned phrases, three main themes emerged at various levels; individual, institutional, and societal.

Results

The final dataset produced 3210 responses, including 1621 comments and 1589 replies. Phrases within these responses were coded as either supportive or concerned for a total of 3562 phrases within the 3210 responses.Footnote2 Most indicated support for the AFP’s drive to increase female recruitment (n = 2028) compared to phrases of concern (n = 1534) (see ).

Table 1. Number of phrases per theme.

Further analysis found that when people were commenting about women in policing, they were discussing it in terms of how women as individuals impact policing (individual perspective), how women in policing impact institutions (institutional perspective), and how women in policing impact society (societal perspective). Most Facebook users were commenting about the societal influences of women in Australian policing with more than two-thirds (68.84%) of the phrases falling into this category compared to institutional (23.61%) and individual (7.55%). Of the societal perspective commentary, most expressed support (72.60%) rather than concern (27.40%). Conversely, comments at the individual and institutional perspectives were mostly expressed as issues of concern compared to support. However, these concerns at the institutional and societal perspectives combined only represented a small proportion of the overall phrases (24.20%).

Individual perspectives

In comparison to the societal and institutional perspectives, there were very few comments at an individual perspective (7.55%). Like the institutional perspective, most were expressed as concerns about women in policing (87.73%). These concerns were expressed in terms of barriers to applying, physical and emotional ability, and other factors such as a preference for male officers and issues with policewomen personalities. When support was expressed, these comments were directly about the ability of female officers including that women could be the best person for the job; categories ‘best-fit’ (n = 20), and personal ‘attributes’ capture attitudes in which users indicate women are suitable for the role (n = 13) (see Appendix 2).

Institutional perspectives

There were 841 phrases which captured institutional level responses with 215 (25.56%) containing supportive phrasing and 626 (74.44%) raising concerns. These institutional-level responses related to the operational need for women police and the institutional impact of their inclusion (see Appendix 3). Sub-themes included standards (both maintaining high standards and increasing recruit standards), operational capacity (in terms of meeting specific female-oriented roles within policing, the general need to meet operational requirements, the benefits of diversifying the workforce, and the evolution of modern policing that is no longer solely about physique). The final theme generated under institutional support addresses the communication of the campaign itself. Commenters convey support at semantic and latent levels. This included clarity provided in the post, and the noble intention of the post.

On the contrary, concerns were raised about the meritocracy of AFP recruitment, the confusing communication of the post, and other concerns regarding culture, corruption, and taxpayer interests. This included sub-themes of merit (in which concerns were raised about meritocracy, lowering of standards, and at the cost of suitable male applicants), communication (that the posting was unclear and a need for further information), as well as other comments such as the police culture, use of taxpayer’s money, and corruption concerns.

Societal perspectives

There were 2452 societal level phrases with 1780 (72.59%) containing support and 672 (27.41%) expressing concerns. These societal-level responses addressed how increasing the number of women in policing may have flow on effects for wider society. Of the total societal comments, the vast majority contained support for policewomen at the societal level (see Appendix 4). This commentary supported the opportunities for women to pursue policing, the progressive nature of breaking chains for women in society, and the benefits of gender balance and representation in policing.

Of societal comments, a substantially smaller proportion of responses raised concern about women police at the societal level. However, this is due to the overwhelming response of societal support. In comparison to other categories, individual and institutional, societal concern indeed raised the most concerned commentary in the dataset. This commentary argues that the AFP’s recruitment approach is discriminatory under Australian law, is performative and politically motivated, fails to meet representation by its unclear definition, disturbs traditional gender roles, neglects a lack of female interest in policing, and other issues such as undermining women in policing and growing anti-police sentiment.

Discussion

This study was the first to explore contemporary public opinions of women in policing. Specifically, it examined Facebook users’ opinions of policewomen by analysing Facebook commentary responding to an Australian Federal Police (AFP) recruitment campaign targeting women. The study identified both the supportive reasonings and the concerns about female officers. Overall, the public responses to the post were mostly supportive. However, there were also some Facebook users who expressed concerns for female police officers. The findings further revealed that the support and concern comments were reflective of three main perspectives: individual (how women as individuals impact policing), institutional (how women in policing impact institutions), and societal (how women in policing impact society). The findings are discussed below in terms of both the support and concern at the three levels along with their implications.

While there were some concerns raised, responses to the 2017 AFP post contained mostly supportive commentary. The supportive commentary was significantly driven at a societal perspective. This finding provides new insights into contemporary opinions of women in policing. While previous research indicated that the public’s primary concerns are about the individual capabilities of women (such as authority, strength, fitness, and emotional and psychological capacity) (Sherman Citation1975, Bell Citation1982, Grennan Citation1987, Balkin Citation1988, Martin Citation1989, Breci Citation1997, Garcia Citation2003), in this study, where concerns were raised, users predominantly addressed the institutional and societal consequences of increased women in policing. This discord in findings between the current study examining contemporary opinions, with previous literature examining opinions from 30 years ago, suggests that the previous concerns of women in policing at the individual level, may have abated or have been suitably addressed. Consequently, opinions of policewomen may be shifting towards higher-level concerns at institutional and societal perspectives.

Individual

Overall, there was relatively little discussion at an individual perspective about women in policing. Indeed, this category was raised the least out of all the themes. When Facebook users did discuss the individual perspectives, this was mostly out of concern. This concern focused on the traditional reasonings such as physicality and fitness levels, as well as the psychological and emotional capacity of females to perform the role. This aligns with the previous generation of academic literature which similarly reported public concern about women in policing due to their perceived physical inability (Grennan Citation1987, Leger Citation1997), and psychological or emotional incompatibility with the policing role (Sherman Citation1975, Jones Citation1986, Breci Citation1997).

Undoubtedly, there is a physical aspect to policing (Bissett et al. Citation2012). Officers who are physically fit are reported to be generally healthier, perform to a higher standard, are more committed to the job, and have greater mental wellbeing than officers who are less physically fit (Boni Citation2004). However, research has also found that traditional fitness standards do not strongly correlate with the requirements of the role, and often officers are not required to keep up any fitness standards after graduation (Leger Citation1997, Bissett et al. Citation2012). Additionally, Sherman (Citation1975) found that suitable training and technique with quick, clear thinking outweigh physical strength when measuring police effectiveness. Furthermore, approximately 90% of policing consists of non-criminal, non-service activities that do not require physical activity (Koenig Citation1978). Hence, policing authorities may need to re-examine and rethink recruitment requirements to be more aligned with these academic findings.

Essentially, there appears to be discord in the discourse between the academic literature and public knowledge. Ultimately, this suggests that misconceptions or lack of knowledge may be influencing public opinion. Hence, providing an opportunity for police organisations to address such misconceptions in both the publicly held perceptions of policewomen and disbanding misconceptions about recruitment requirements (such as strength and fitness) may increase positive perceptions of policewomen and encourage more female recruits to apply.

Institutional

While a moderate number of Facebook users’ expressed support for women in policing at the institutional level, more than twice the number of Facebook users raised institutional concerns regarding the inclusion of women in policing. Interestingly, both support and concern were expressed in similar ways: the quality of recruits, workplace impacts, and the campaign itself.

The most discussed point at the institutional level was the quality of recruits and the critical standards of AFP officers. Historic concerns over diversity targets and the implications for merit-based processes are echoed in the previous research (see Foley and Williamson Citation2018). Facebook users question how gendered recruitment targets will impact the quality of police recruits and if entry-level standards are being lowered to boost female recruitment. This commentary does not directly question the ability of the women but highlights an overarching concern that the critically high standards of the police are being manipulated to advance unsuitable women through the recruitment process. These findings indicate an underlying scepticism of female ability, however, more concerningly, it indicates cynicism in the integrity and practices of the police. Distrust in the police and their practice creates tension between police and the public which strains police legitimacy. Police authorities should consider these findings in aiming to reduce tensions. For example, community-oriented policing approaches have been found to increase public perceptions of legitimacy and strengthen relationships (Joudo Larsen Citation2010). Applied to the current topic, educational awareness and transparency in approach, by engaging with the public via social media, may aid to both address any misconceptions and enhance police-community relationships.

On the contrary, the current study also found contradicting insights regarding the quality of female recruits. Some Facebook users strongly supported the ability of female recruits to maintain, and even increase, the high standards of AFP recruits. This finding is interesting as it moves beyond the public and academic debate that female recruits simply ‘keep up’ with standards. For the first time, these findings suggest that the public view an increase of female applicants as potentially increasing the standards of police recruits. This would indicate a major shift in opinions from women as ‘keeping up’ to women as ‘setting benchmarks’. These findings suggest that there is a growing support and understanding for the role of women in policing and police authorities may be able to utilise and cultivate such support to shift negative perceptions within both the workplace and the community.

Another interesting point discussed at the institutional level was the impact that female officers would have on the police workforce. Supportive comments for women in policing were similar to those found in the academic research. For example, including more women in policing might address some of the current problems found in the policing workplace. These include decreased instances of sexual harassment (Sojo & Wood Citation2012), easier access to female officers when essential (such as searches conducted on female offenders) (Natarajan Citation2008), and the facilitation of trust and cooperation with the community through bureaucratic representation (Rabe-Hemp and Miller Citation2018).

Indeed, some of these current problems within the policing workplace were identified by the Facebook users in the current study as the reason why women were not applying to become police officers in the first instance. Broderick (Citation2016) noted that women are often unwelcome in male-dominated spaces and suffer stressors such as sexual harassment and assault, reduced social support, tokenism, and the emotional and psychological consequences of such treatment. In the current study, some Facebook users argued that the lack of women police was not a reflection of female interest in policing work but a reflection of female aversion to police culture. Facebook users proposed that cultural issues within policing, such as a history of bullying and sexual harassment, discourages women from application or caused women to withdraw from recruitment or sworn service. Policing authorities should examine their policies and practices about harassment and strengthen where possible.

Societal

Predominately, the discussion about women in policing was at a societal perspective. This was positively discussed two and a half times more than negatively driving the overall positive finding. These findings indicate a strong societal shift and support that was not identified in the prior body of knowledge.

The high number of support for women in policing at the societal level consisted of Facebook users showing interest in the opportunity, or encouragement for other women to pursue recruitment. User’s either expressed their personal interest in the recruitment campaign, or ‘tagged’ other women and encouraged them to apply. This is a profound finding, given that policing agencies both in Australia and around the world continually struggle to recruit and retain women (Ward et al., Citation2021) and policing authorities should consider campaign designs that utilise this snowballing effect. This significant amount of discussion around opportunity suggests that between female interest and female recruitment, barriers are preventing women from applying to the force or completing training. Other findings in this research, such as misconceptions about the physiological expectations of female recruits, or workplace culture, might explain this disengagement.

Additionally, some Facebook users insisted that increasing women in policing was indicative of progressive social movements by addressing entrenched power imbalances and setting an example for increasing the representation of other marginalised and minority groups in policing. Indeed, these findings are reflective of the broader literature about the progression of women’s rights and autonomy in modern society (United Nations Citation2009), the utilisation of the growing female labour market (Toohey et al. Citation2009, Broderick Citation2016), supporting women in male-dominated spaces, and the positive impacts this has for women in leadership and younger women (Desveaux et al. Citation2010). Such strong support in terms of the quantity of responses indicates a shift in societal attitudes.

While the societal response was overwhelmingly supportive, there was also a proportion of Facebook users expressing societal concern. Mostly, Facebook users raised issue with the supposed purpose of gender targets. Facebook users speculated on the unforeseen impacts these targets may have, such as discrimination against men and the undermining of women. If the public perceives gender targets as discriminating against men, this could deter suitable male applicants from applying and could further damage public perceptions of police integrity. Police authorities should reassess their recruitment processes for any potential male discrimination and reassure the public with transparency that ethical and appropriate protocols are followed.

Additionally, Newton and Huppatz (Citation2020) captured concerns expressed by 18 Australian policewomen to find a perceived loss of respect and credibility as a result of gender quotas. Raised under the notion of the ‘feminization’ of the workforce, if female officers feel undermined by gender targets, this presents morale and respect issues that may impact performance or may cause women to leave policing in pursuit of work where they feel more valued and respected (Newton and Huppatz Citation2020). Policing organisations need to consider how the existing cohort of female officers perceives gender-targeted recruitment and if this will have lasting impact of workplace cohesion and morale.

Significant concerns were raised about the political nature of gender targets, and this seemingly impacted how the public perceived gendered-recruitment and the increase of female officers. Facebook users accused the AFP of pandering to ‘leftist’ ideology and virtue signalling to appear progressive. These issues isolate growing dissonance between conservative and progressive ideologies in modern Australia. Regardless of political engagement, the AFP is designed to serve all Australians. Jost et al. (Citation2003) found that political conservatism was linked to resistance to change in times of uncertainty, particularly when an individual’s beliefs are under threat. If the increase of female police officers in Australia threatens the ideology of conservative Australians, this raises the potential for distrust between conservative communities and their police. Relationships between police and conservative groups must be carefully navigated when designing and implementing progressive policies. Acknowledging concerns and providing education can help more conservative members of the community understand how gender-diverse policing will benefit both them, and their community at large.

Some Facebook users cite barriers to female recruitment which stem from social and cultural expectations of women as mothers and caretakers. Facebook users imply they would be interested in recruitment however the expectations of recruits, such as full-time training in regional locations, and the expectations of motherhood, such as full-time care, are incongruent. This finding is strongly supported by the existing literature that women, often as primary carers, struggle to balance policing and motherhood responsibilities (Broderick Citation2016). If women feel recruitment is inaccessible to them, policing organisations miss out on opportunities to recruit from broader, more diverse applicant pools (Broderick Citation2016). Opportunities for women and mothers, such as part-time work, need to be promoted effectively to the public (U.S. Department of Justice Citation2019).

Finally, a very small, but increasingly important, group of Facebook users denied interest in the AFP, or policing more generally, due to their anti-policing beliefs. Given the politically charged discourse surrounding race and police brutality globally, and the overrepresentation of deaths of First Nations peoples in Australian custody (ACTCOSS and AJC Citation2008), it would be expected that this discourse has continued to grow since 2017. If anti-police sentiment continues to grow unaddressed in Australia, a serious threat to police legitimacy emerges. Implications range from tensions between police and citizens, to extreme reactions such as protests and police-citizen violence (Lydon Citation2021). Only by engaging with and understanding anti-police discourse can researchers and police organisations implement strategies to heal police-community relations and manage police legitimacy in Australia.

Limitations and strengths

It is important to place these findings in context of the strengths and limitations of the study. First, as with any research design, there are limitations to conducting a thematic analysis. The flexible design and interpretation of the analysis can lead to subjective inconsistencies (Holloway and Todres, Citation2003). We aimed to reduce some of this subjectivity by using multiple coders and creating a coding dictionary (see methods). However, future researchers may consider using an established lexicon and computer-generated sentiment analysis to reduce such subjectivity. However, sentiment analysis software is not without its own limitations such as its failure to identify the diversity and intricacy of sarcastic or ironic commentary (Fleet and Hine Citation2022) which was also evident in the current study. Future research may consider using a mixed methods approach that relies on the combination of both computer-generated sentiment analysis and thematic analysis.

Second, there are limitations to who this sample represents. Primarily, due to the demographic limitations of Facebook privacy settings, characteristics of users who respond to these posts could not be identified. This means that the opinions raised might be contextualised for the user, without the researcher’s ability to note. Research suggests that the characteristics of an individual likely impact their opinion of police officers. Indeed, age (Breci Citation1997), race (Brooks and Friedrich Citation1970), sex (Milton Citation1972), gender identity (Miles-Johnson Citation2015), sexual identity (Miles-Johnson Citation2013), and level of education (Kerber et al. Citation1977) have been associated with public opinions of police. Further, the nationality of users may contextualise opinions of police due to laws, events, or the structure of policing that are unique to their own country. Due to the third-party nature of collecting and analysing this data in an ethical manner, this research is unable to produce demographics on the age, gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, or other influencing characteristics that may inform these public opinions. However, Facebook analytics allow group admins to review the demographic characteristics of users who interact with posts; including age, gender, and city/country of origin (Facebook Help Centre Citation2022b). Future research should partner with police social media teams to gather further demographic information on users who interact with posts.

Third, though social media use (particularly Facebook) is increasingly common in western democracies, and social media provides broad access to previously unreachable groups, there are still groups who may not be represented through this platform. Namely, remote and rural communities, those without internet access, and those who do not use Facebook for various personal choices. This may exclude low socio-economic groups, First Nation Australians, those with low literacy and reading skills, and culturally and linguistically diverse Australians, amongst others. This presents issues when we consider that groups such as First Nation Australians come into contact with police at higher rates than non-Indigenous Australians (ACTCOSS and AJC Citation2008). If groups like this are not represented through social media samples, key opinions of women police in Australia may be missing. Future research should aim to target the opinions of such communities.

Fourth, among those who do use social media it is also important to consider the limitations of how users enact their social media membership. People use social media in different ways, and it is possible that those users who comment on posts have polemic opinions or enjoy engaging in debate online. As the literature lacks understanding of how users engage with social media, it becomes increasingly difficult for researchers to decipher tone and attitude, such as sarcasm and irony, within text responses. The literature is also lacking understanding on how Facebook affords anonymity to its users. Whether users post under their real name or a pseudonym will impact the anonymity they feel on the platform and further impact their behaviour. Those who use their real name and connect with peers online may offer socially desirable opinions. However, those who do not use their real name may feel a sense of anonymity which causes them to be more honest and potentially polarising in their opinions. It is critical to consider how users engage with the Facebook platform to present their own identity, and how this might impact what opinions they share.

Despite these limitations, social media data offers a breadth of data that could not be collected through the scope of regular survey or interview research. Indeed, the use of Facebook commentary as a data source provided over 5,000 comments which is much higher than the previous telephone surveys which consisted of 200 and 702 participants (Leger Citation1997, Breci Citation1997). The larger sample size in the current study results in access to broader opinions and potentially a deeper understanding of public opinion. Furthermore, the anonymity of social media also aids to the reduction of some of the social desirability biases often found in other methods such as interviews and surveys.

Conclusion

This study explored how social media users perceive women in Australian policing. By analysing social media commentary, we found both support and concerns across three perspectives: individual, institutional, and societal. Overall, there was mostly a positive opinion about women in Australian policing. Moreover, the findings indicated that a shift had occur in public opinions when compared to previous research. Previous research indicated that public concerns regarding women in policing would likely centre around the individual capabilities of women to perform the role. However, our findings suggest that contemporary public opinions have shifted. Indeed, our results indicate that individual concerns seem to have abated, where institutional and societal concerns have grown. Concerns raised at the societal level primarily indicate disapproval of changing gender roles in policing through accusations of discrimination against men, the questioning of representation, and performative diversity.

These concerns are indicative of growing dissonance between conservative ideals which aim to maintain traditional gender roles, and the progressive views which promote gender diversity. This resistance to change may impact how the public view the increase of policewomen. This may suggest that modern opinions of women in policing are perhaps not reflective of actual policewomen but reflect discomfort with changing gender roles in society. Future research should investigate how changing attitudes towards gender, gender identity, and gender diversity and inclusivity may be shaping public opinion towards women in policing. The police exist to serve the whole community, which includes catering for the growing discord between conservative and progressive views.

This research highlights important public opinions that policing organisations should consider when managing their gender diversity targets and community relations. First, by understanding the concerns that community members hold towards gendered recruitment and female officers, such as discrimination against men or the physiological capabilities of women, police organisations can rethink policy and redesign practices to maintain integrity in the eyes of the public. This includes publicly addressing concerns regarding discriminatory practices and increasing transparency of process, and providing education to the public on the benefits and capabilities of female officers. Second, police organisations can benefit from the supportive commentary provided by the public to further promote the benefits of gender diversity and gendered recruitment in policing to both increase the public understanding and support for these processes, and to encourage more diverse groups to join the police. Addressing concerns and benefitting from the support raised in regard to gendered recruitment and the subsequent increase of female officers in Australian policing gives police organisations the opportunity to promote respect between the police and the community they serve, while cultivating a more diverse workforce and consequently enhancing community trust and confidence in the police.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The remaining uncollected data contained the least amount of user contributed text. This primarily included ‘tagged comments’, e.g. one user ‘tagging’ another user. Irrespective of collection capacity, these comments could not be analysed as they solely contained a username. Therefore, this technological barrier introduces minimal systematic bias.

2 Responses codes were not mutually exclusive and, therefore, some phrases may occur in multiple categories.

References

- ACT Council of Social Services and the Aboriginal Justice Centre. 2008. Circles of support, towards indigenous justice: prevention, diversion & rehabilitation [online]. Available from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi = 10.1.1.899.7291&rep = rep1&type = pdf [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Allen, C., and Sibthorpe, C. 2017. AFP announces female-only recruitment round. ABC News, 28 Sept [online]. Available from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-09-28/afp-female-only-recruitment-drive/8995484 [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Allport, F.H., 1937. Toward a science of public opinion. Public opinion quarterly, 1 (1), 7–23.

- Ashlock, J., 2019. Gender attitudes of police officer: selection and socialization mechanisms in the life course. Social science research, 79, 71–84.

- Australian Federal Police. 2017. We’re recruiting! Yes, again. The AFP needs more women in its ranks. Facebook Status update, 28 September. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/AusFedPolice/posts/1487742954699636:0 [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Australian Federal Police. 2018. International Command Gender Strategy 2018-2024, Australian Federal Police, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. Available from: https://www.afp.gov.au/sites/default/files/PDF/23082021-InternationalCommandGenderStrategy.pdf [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Balkin, J., 1988. Why policemen don't like policewomen. Journal of police science & administration, 16 (1), 29–38.

- Bell, D., 1982. Policewomen: myths and realities. Journal of police science and administration, 10, 112–120.

- Biddle, N. 2022. Do we trust our criminal justice system? What Australia Thinks … [online]. Australian National University Social Research Centre. Available from: https://whataustraliathinks.org.au/data_story/do-we-trust-our-criminal-justice-system/ [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Bissett, D., Bissett, J., and Snell, C., 2012. Physical agility tests and fitness standards: perceptions of law enforcement officers. Police practice and research, 13 (3), 208–223.

- Blumer, H., 1948. Public opinion and public opinion polling. American sociological review, 13 (5), 542–549.

- Bolger, M., Lytle, D., and Bolger, C., 2021. What matters in citizen satisfaction with police: a meta-analysis. Journal of criminal justice, 72 (1), 1–10.

- Bolger, P., and Walters, G., 2019. The relationship between police procedural justice, police legitimacy, and people’s willingness to cooperate with law enforcement: a meta-analysis. Journal of criminal justice, 60, 93–99.

- Bolton, S., and Muzio, D., 2008. The paradoxical processes of feminization in the professions: the case of established, aspiring and semi-professions. Work, employment and society, 22 (2), 281–299.

- Boni, N., 2004. Exercise and physical fitness: The impact on work outcomes, cognition, and psychological well-being for police. Australian centre for policing research, 10, 1–8.

- Bragais, A., Hine, K.A., and Fleet, R., 2021. Only in our best interest, right?’ public perceptions of police use of facial recognition technology. Police practice and research, 22 (6), 1637–1654.

- Breci, M., 1997. Female officers on patrol: public perceptions in the 1990s. Journal of crime and justice, 20 (2), 153–165.

- Brereton, D. July 1999. Do women police differently? Implications for police–community relations. Paper presented to the Second Australasian Women and Policing Conference, Brisbane.

- Broderick, E. 2016. Cultural change: gender diversity and inclusion in the Australian Federal Police, Australian Federal Police, Canberra. Available from: https://www.afp.gov.au/sites/default/files/PDF/Reports/Cultural-Change-Report-2016.pdf [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Brooks, W.D., and Friedrich, G.W., 1970. Police image: an exploratory study. Journal of communication, 20 (4), 370–374.

- Brown, J., 2016. Revisiting the classics: women in control? The role of women in law enforcement: frances heidensohn. Policing and society, 26 (2), 230–237.

- Brown, J., and Heidensohn, F., 2000. Gender and policing: comparative perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brown, J., and Silvestri, M., 2020. A police service in transformation: implications for women police officers. Police practice and research, 2 (5), 459–475.

- Carli, L., 2001. Gender and social influence. Journal of social issues, 5 7 (4), 725–741.

- Carrington, K., et al., 2020. How women’s police stations empower women, widen access to justice and prevent gender violence. International journal for crime, justice and social democracy, 9 (1), 42–67.

- Córdova, A., and Kras, H., 2019. Addressing violence against women: the effects of women’s police stations on police legitimacy. Comparative political studies, 53 (5), 775–808.

- Crime and Corruption Commission. 2021. Investigation Arista: a report concerning an investigation into the Queensland Police Service’s 50/50 gender equity recruitment strategy, Crime and Corruption Commission, Queensland Available from: https://www.ccc.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/Docs/Publications/CCC/Investigation-Arista-A-report-concerning-an-investigation-into-the-Queensland-Police-Services-50-50-gender-equity-recruitment-strategy.PDF [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Desveaux, G., Devilland, S., and Sancier-Sultan, S. 2010. Women matter: women at the top of corporations: making it happen. McKinsey & Company. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/women-at-the-top-of-corporations-making-it-happen [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Facebook Help Centre. 2022a. How do I comment on something I see on Facebook? Facebook. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/help/187302991320347/?helpref = search [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Facebook Help Centre. 2022b. Where can I see insights for a Facebook group that I admin? Facebook. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/help/ipad-app/312362745877176 [Accessed 23 December 2022].

- Fleet, R.W., and Hine, K.A. 2022. Surprise, anticipation, sadness, and fear: a sentiment analysis of social media’s portrayal of police use of facial recognition technology. Policing, Online First, https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paab083.

- Fleming, J., 2010. Community policing: the Australian connection. In: J. Putt, ed. Community policing in Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, 1–7.

- Foley, M., and Williamson, S., 2018. Managerial perspectives on implicit bias affirmative action, and merit. Public administration review, 79 (1), 35–45.

- Freeman, H. 2020. ‘Tradwives’: the new trend for submissive women has a dark heart and history. The Guardian, 28 Jan [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2020/jan/27/tradwives-new-trend-submissive-women-dark-heart-history [Accessed 10 October 2022].

- Garcia, V., 2003. Difference in the police department: women, policing, and doing gender. Journal of contemporary criminal justice, 19, 330–344.

- Grennan, S, 1987. Findings on the Role of Officer Gender in Violent Encounters with Citizens. Journal of Police Science and Administration, 15 (1), 78–85.

- Grimes, M., and Wängnerud, L., 2010. Curbing corruption through social welfare reform? The effects of Mexico’s conditional cash transfer program on good government. The American review of public administration, 40 (6), 671–690.

- Hellwege, J., Mrozla, T., and Knutelski, K., 2021. Gendered perceptions of procedural (in)justice in police encounters. Police practice and research, 23 (2), 143–158.

- Herbst, S., 1998. Reading public opinion: How political actors view the democratic process. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Hinds, L., and Murphy, K., 2007. Public satisfaction with police: using procedural justice to improve police legitimacy. The Australian and New Zealand journal of criminology, 40 (1), 27–42.

- Hine, K.A., and Davenport-Klunder, K.M., 2022. From the aspirational to the tangible: mapping key performance indicators in Australian policing. International Journal of Police Science and Management, 24 (4), 382–396.

- Holloway, I., and Todres, L., 2003. The status of method: flexibility, consistency and coherence. Qualitative research, 3 (3), 345–357.

- Home Office, 2010. Assessment of women in the police service. Home Office.

- Independent Police Commission, 2013. Policing for a better Britain. London: The Commission.

- Institute for Economics and Peace, 2020. Global peace index 2020: measuring peace in a complex world. Sydney: Institute for Economics and Peace. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/reports [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Jones, S., 1986. Women police: caught in the Act. Policing, 2, 129–140.

- Jost, J.T., et al., 2003. Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological bulletin, 129 (3), 339–375.

- Joudo Larsen, J., 2010. Community policing in culturally and linguistically diverse communities. In: J. Putt, ed. Community policing in Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, 25–31.

- Kanter, R M, 1977. Some Effects of Proportions on Group Life: Skewed Sex Ratios and Responses to Token Women. American Journal of Sociology, 82 (5), 965–990.

- Kennedy, D.B., and Homant, R.J., 1983. Attitudes of abused women toward male and female police officers. Criminal justice and behavior, 10, 391–405.

- Kerber, K.W., Andes, S.M., and Mittler, M.B., 1977. Citizen attitudes regarding the competence of female police officers. Journal of police science and administration, 5 (3), 337–347.

- Kim, P.S., 1994. A theoretical overview of representative bureaucracy: synthesis. International review of administrative sciences, 60, 385–397.

- Koenig, E.J., 1978. An overview of attitudes toward women in Law enforcement. Public administration review, 38 (3), 267–275.

- Krislov, S., and Rosenbloom, D., 1981. Representative bureaucracy and the American political system. New York: Praeger.

- Laurence, J.H., et al., 2016. Predictors of support for women in military roles: military status, gender, and political ideology. Military psychology, 28 (6), 488–497.

- Lee, M., and McGovern, A., 2013. Force to sell: policing the image and manufacturing public confidence. Policing and society, 23 (2), 103–124.

- Leger, K., 1997. Public perceptions of female police officers on patrol. American journal of criminal justice, 21 (2), 231–249.

- Lydon, D., 2021. The construction and shaping of protesters’ perceptions of police legitimacy: a thematic approach to police information and intelligence gathering. Police practice and research, 22 (1), 678–691.

- Marinova, J., Plantegna, J., and Remery, C. 2010. Gender diversity and firm performance (Tjalling C. Koopmans Research Institute Discussion Paper Series 10-03). Available from: https://www.uu.nl/sites/default/files/rebo_use_dp_2010_10-03.pdf [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Martin, S.E. May 1989. Women on the move? A report on the status of women in policing. Police Foundation Reports. Available from: https://www.policefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Martin-1989-Women-on-the-Move-Status-of-Women-in-Policing.pdf [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Mawby, R.C., 2002. Continuity and change, convergence and divergence: The policy and practice of police-media relations. Criminal justice, 2 (3), 303–324.

- McDowell, J. 1992. Are women better cops? Time Magazine, 17 Feb, p. 70–72. https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/are-women-better-cops.

- McGregor, S., 2019. Social media as public opinion: how journalists use social media to represent public opinion. Journalism, 20 (8), 1070–1086.

- Metropolitan Police. 2021. STRIDE: the Met’s strategy for inclusion, diversity and engagement. Metropolitan Police, United Kingdom. Available from: https://www.met.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/media/downloads/force-content/met/about-us/stride/strategy-for-inclusion-diversity-and-engagement-stride-2021-2025.pdf [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Miles-Johnson, T., 2013. Confidence and trust in police: How sexual identity difference shapes perceptions of police. Current issues in criminal justice, 25 (2), 685–702.

- Miles-Johnson, T., 2015. They don’t identify with Us”: perceptions of police by Australian transgender people. International journal of transgenderism, 16 (3), 169–189.

- Miller, S.L., 1999. Gender and community policing: walking the talk. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

- Milton, C., 1972. Women in policing. Washington: Police Foundation.

- Morash, M., 1986. Perspective: understanding the contributions to police work. In: L. Radelet, ed. The police and the community. New York: Macmillan, 290–295.

- Muir, W.K., 1977. Police: streetcorner politicians. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Natarajan, M., 2008. Women police in a changing society: back door to equality. 1st ed. x: Routledge.

- National Centre for Women and Policing. 2002. Equality denied; the status of women in policing. National Centre for Women and Policing, Los Angeles. Available from: http://www.womenandpolicing.org/PDF/2002_Status_Report.pdf [Accessed 10 October 2021].

- Newton, K., and Huppatz, K., 2020. Policewomen’s perceptions of gender equity policies and initiatives in Australia. Feminist criminology, 15 (5), 593–610.

- New York University School of Law. 2021. Advancing women in policing 30% women recruits by 2030 [online]. Available from: https://30 ( 30initiative.org/ [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Nguyen, H., and Inman, M. 2017. AFP Facebook post targeting female recruits causes social media meltdown. The Canberra Times, 28 Sept, [online]. Available from: https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6027711/afp-facebook-post-targeting-female-recruits-causes-social-media-meltdown/ [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Northern Territory Police, Fire & Emergency Services. 2020. Annual Report 2019-20. Northern Territory Government: Australia.

- Prenzler, T., & ProQuest (Firm). 2015. 100 years of women police in Australia. Samford Valley: Australian Academic Press.

- Prenzler, T., and Sinclair, G., 2013. The status of women police officers: an international review. International journal of Law, crime and justice, 41 (2), 115–131.

- Rabe-Hemp, C.E., 2008. Female officers and the ethic of care: does officer gender impact police behaviours? Journal of criminal justice, 36 (5), 426–434.

- Rabe-Hemp, C.E., and Miller, S., 2018. Special issue: women at work in criminal justice organizations. Feminist criminology, 13 (3), 231–236.

- Reddick, C.G., Chatfield, A.T., and Jaramillo, P.A., 2015. Public opinion on national security agency surveillance programs: A multi-method approach. Government information quarterly, 32 (2), 129–141.

- Reiner, R., 2003. Policing and the media. In: T. Newburn, ed. Handbook of policing. (1st ed.) London: Taylor & Francis, 259–281.

- Rothstein, B. 2017, June. Gender equality, corruption and meritocracy (Blavatnik School of Government Working Paper Series). https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-05/BSG-WP-2017-018.pdf.

- Sarre, R., and Prenzler, T., 2018. Ten key developments in modern policing: an Australian perspective. Police practice and research, 19 (1), 3–16.

- Schuck, A.M., 2014a. Gender differences in policing: testing hypotheses from the performance and disruption perspectives. Feminist criminology, 9 (2), 160–185.

- Schuck, A.M., 2014b. Female representation in law enforcement: the influence of screening, unions, incentives, community policing, CALEA, and size. Police quarterly, 17 (1), 54–78.

- Sherman, L., 1975. An evaluation of policewomen on patrol in a suburban police department. Journal of police science and administration, 3, 434–438.

- Shjarback, J.A., and Todak, N., 2019. The prevalence of female representation in supervisory and management positions in American law enforcement: an examination of organizational correlates. Women & criminal justice, 29 (3), 129–147.

- Silvestri, M., Tong, S., and Brown, J., 2013. Gender and police leadership: time for a paradigm shift? International journal of police science & management, 15 (1), 61–73.

- Sojo, V., and Wood, R. 2012. Resilience: women’s Fit, functioning and growth at work: indicators and predictors, centre for ethical leadership, Melbourne Business School. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/8458442/Resilience_Womens_Fit_Functioning_and_Growth_at_Work_Indicators_and_Predictors [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- South Australia Police, 2020. Annual reporting 2019-20: personnel information summary. Australia: Government of South Australia.

- Statista. 2021a. Number of monthly active Facebook users worldwide as of 1st quarter 2021.Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/#professional [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Statista. 2021b. Number of Facebook users in Australia from 2015 to 2022. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/304862/number-of-facebook-users-in-australia/ [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Toohey, T., Colosimo, D., and Boak, A. 2009. Australia’s hidden resource: the economic case for increasing female participation, Goldman Sachs & JB Were. Available from: https://www.asx.com.au/documents/about/gsjbw_economic_case_for_increasing_female_participation.pdf [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Tyler, T., 1990. Why people obey the law. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Tyler, T., 2003. Procedural justice, legitimacy, and the effective rule of law. Crime and justice, 30, 283–357.

- Tyler, T., 2004. Enhancing police legitimacy. The ANNALS of the American academy of political and social science, 593 (1), 84–99.

- United Nations, 2009. 2009 world survey of the role of women in economic development. New York: United Nations.

- U.S. Department of Justice, 2019. Women in policing: breaking barriers and blazing a path. Washington: National Institute of Justice Special Report). U.S. Department of Justice.

- Victoria Police. 2020. Annual Report 2019-2020. State of Victoria (Victoria Police): Australia.

- Wadham, B., et al., 2018. War-fighting and left-wing feminist agendas’: gender and change in the Australian defence force. Critical military studies, 4 (3), 264–280.

- Ward, A., Prenzler, T., and Drew, J., 2021. Innovation and transparency in the recruitment of women in Australian policing. Police practice and research, 21 (5), 525–540.

- Western Australia Police Force. 2020. 2020 Annual Report. Western Australian Police Force: Australia.

- Williams-Woolley, A., et al., 2010. Evidence of a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science, 330 (6004), 686–688.

- Woolley, A., and Malone, T., 2011. What makes a team smarter? More women. Harvard business review, 89 (6), 32–33.

- Yellow, 2020. Yellow social media report. part One – consumers. Melbourne: Thryv Australia Ptd Ltd.

Appendices

Appendix 2

Supportive and concerned individual perspective phrases for women in policing.

Appendix 3

Supportive and concerned institutional perspective phrases for women in policing.

Appendix 4

Supportive and concerned societal perspective phrases for women in policing.