ABSTRACT

Police forces are increasing their use of artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities for security purposes. However, citizens are often aware and cautious about advanced policing capabilities which can impact negatively on the perceived legitimacy of policing efforts and police more generally. This study explores citizens’ subjective perspectives to police use by AI, including tensions between security, privacy, and resistance. Using Q methodology with 43 participants in the UK, Netherlands, and Germany we identified five distinct perspectives towards AI use by police forces. The five perspectives illustrate the complex, diverse viewpoints citizens exhibit with respect to AI use by police and highlight that citizens’ perspectives are more complex than often portrayed. Our findings offer theoretical and practical implications for public engagement around general versus personal safety, privacy and potentials for moral dilemmas and counter-reactions.

1. Introduction

In the current era, marked by the growing relevance of artificial intelligence (AI) to most aspects of life, policing has been equally touched by the implementation of AI to advance investigations, safety, and security (Fussey and Sandhu Citation2022, Urquhart and Miranda Citation2022). These advances often trigger citizen concerns about the strategies and technical tools being used as part of modern policing with legitimate concerns about the possible implications and repercussions of implementing new capabilities (e.g. Moses and Chan Citation2016, Fussey et al. Citation2021) as well as concerns about the ‘gradual outsourcing of police work’ (Smith et al. Citation2017, p. 260). Debates in this context are often framed around the notion of a ‘trade-off’ between privacy and security (Pavone and Esposti Citation2012), which in turn contributes to the spread of a narrative that suggests an ‘antagonistic relationship’ between police and the public (Nalla et al. Citation2018, p. 271).

This study aims to question this either-or approach with the objective to obtain a better understanding of the possible complexity within citizens’ views around AI use by police. Our inquiry reacts to calls to refine the ‘privacy versus security’ narrative in the policing domain (cp. for instance, the ‘Freedom AND Security Citation2018 – Data Protection Conference’ organised by EuropolFootnote1). As Solove claims, the current debate ‘has been framed incorrectly, with the trade-off between these values understood as an all-or-nothing proposition’ (Solove Citation2011, p. 2). In this paper, we aim to offer a realistic appreciation of citizens’ perspectives and their sense-making about the complex domain of AI use by police. Our study contributes in theoretical terms to debates on citizen attitudes about policing practices by providing a new framework for the categorisation of subjective perspectives. Specifically, it offers new insights into the way individuals make sense of and aim to resolve tensions between privacy and security raised by police use of AI. This investigation purposefully went beyond questions of attitudes (i.e. acceptance or rejection) by questioning possible behavioural consequences of surveillance fears and the moral dilemmas such behaviours may entail. In practical terms, we highlight the need for a balanced stance that can acknowledge the benefits and the risks of AI to account for their societal concerns and ramifications. This answers important calls for assessing ‘the complexities and uncertainties brought by novel technologies’ in modern-day policing (Fussey and Sandhu Citation2022, p. 11).

In the subsequent sections, we outline the background to the study, followed by an explanation of the empirical approach, an exploration of the findings and their theoretical and practical implications.

1.1. AI use by police forces

Over the past years, surveillance for safety and security purposes has expanded considerably (Turner et al. Citation2019) driven by the adoption of new technologies by police forces. One of the most recent entries is AI, defined as ‘systems that display intelligent behaviour by analysing their environment and taking actions – with some degree of autonomy – to achieve specific goals’ (Committee of the Regions for Artificial Intelligence in Europe Brussels Citation2018, p. 1).

AI algorithms and data analytics capabilities are being adopted by police forces in various functionalities (Babuta and Oswald Citation2020), generally with a view to increase efficiency and reduce resource demands on policing time and personnel. For instance, in the UK, Durham Constabulary adopted the Harm Assessment Risk Tool (HART) to predict the likelihood of re-offending by criminals within two years of being released from prison to determine whether certain individuals might benefit from a rehabilitation programme (Oswald et al. Citation2018). In parallel, the Metropolitan Police joined South Wales police in trialling facial recognition technology to automatically identify people through CCTV, particularly at large events, for crime detection and prevention purposes (Oswald et al. Citation2018, Metropolitan Police and NPL Citation2020). AI capabilities are also considered by police for combatting serious crimes such as terrorism, child sexual exploitation or organised crime (Završnik Citation2020).

The call for police use of AI is often predicated by the growing complexity and globalisation of the crime landscape, specifically the possibility to predict, identify and counter new crime trends (e.g. Fussey and Sandhu Citation2022). An example is cybersecurity which has gained attention due to a ‘technological arms race’ between attacker and defender (Schneier Citation2012), in the sense that the former constantly seeks weaknesses to infiltrate systems and the latter aims to prevent and defend against increasingly sophisticated intrusions (Tounsi and Rais Citation2018). Growing sophistication and shifts in criminal modus operandi and crime patterns in smart societies (Kaufmann et al. Citation2019) provide a motivation for police to advance their frameworks and capabilities with a view to safeguard their operational efficiency (Jahankhani et al. Citation2020), and ultimately the safety of society. Generally, the use of AI capabilities by police forces are seen to hold considerable potential and benefits for safety (Morgenstern et al. Citation2021), evidence collection and the mitigation of threats (Lyon Citation2002).

Yet, advances in AI capabilities also create conflicts between their potential security benefits and concerns about their accuracy and fairness, the potential for discrimination of specific groups and the reinforcement of societal inequalities (e.g. Bushway Citation2020, Quattrocolo Citation2020, Završnik Citation2020, FRA Citation2021). This is often coupled with a perceived lack of evidence for the efficiency of algorithmic-based decisions and a ‘fear of contact’ emanating from alliances of police with the private sector (Trottier Citation2017, p. 475).

In reaction to growing societal concerns about the use of AI capabilities by law enforcement, counter movements have sprung up particularly targeting large-scale automated surveillance in public places or online – ranging from campaigns such as ReclaimYourFace (https://reclaimyourface.eu) to technological solutions to hide one’s online footprint (e.g. Cover your tracks or PrivacyBadger by the Electronic Frontier FoundationFootnote2). In a further example, in June 2020 Amazon, IBM and Microsoft halted their sale of facial recognition software to police forces, demonstrating the impact of strong public opinions towards police use of AI (Lee and Chin Citation2022). Citizen reactions can thus have a considerable impact on the opportunities of police to develop and deploy AI. In consequence, understanding citizen reactions is of vital concern for police forces to retain public trust and the legitimacy of their actions.

1.2. Citizen reactions to AI use by police

Public acceptance of AI use by police has received considerable attention over the last years. Interestingly, results reveal considerable variations in public reactions. For instance, a survey with 154,195 respondents across 142 countries (Neudert et al. Citation2020) suggests clear regional differences whereby 49% of participants from Latin-America and Caribbean, 47% in North America and 43% in Europe considered AI to be ‘mostly harmful’, whereas 59% of participants in East Asia considered AI as ‘mostly helpful’. AI acceptance is also influenced by demographics. A report investigating citizens’ level of trust in AI in Australia revealed that young people, people with knowledge of computer science and people of higher educational levels are more positive towards AI (Lockey et al. Citation2020). A recent survey across 30 countries conducted by the AP4AI project,Footnote3 which focuses specifically on AI use by police forces (Akhgar et al. Citation2022), found that most participants were positive towards AI for specific purposes (e.g. 90% agreed/strongly agreed to its use for the safeguarding of children and vulnerable groups, 79% to its use to prevent crime before they happen). In contrast, an earlier investigation by Amnesty International (Citation2015) revealed strong negative attitudes towards ‘government surveillance’. Although not directly focused on AI use, participants largely disagreed with their governments intercepting, storing, and analysing their data.Footnote4

This short selection of findings is indicative of the diversity and contradictory nature of public attitudes towards AI use by police when framed purely as acceptance versus rejection, and towards their potential for ‘safeguarding’ versus ‘surveilling’ society. Discussions about the threat of technological advances on privacy (e.g. Bradford et al. Citation2020) thus tend to be accompanied by arguments that citizens are willing to sacrifice some degree of their privacy for the benefit of safety (e.g. Davis and Silver Citation2004), which is in line with Solove (Citation2011), who argues that the dichotomy between privacy and security is largely artificial.

Some indications exist on the underlying factors that shape the observed diversity in attitudes and reactions. Gurinskaya (Citation2020), for instance, identified trust in the efficiency of surveillance technologies as part of a cost–benefit assessment that affects citizens’ acceptance or rejection of AI use by police. On the other hand, perceived ramifications on citizens’ rights and abilities to free expression (Benjamin Citation2020) can be one of many factors that trigger resistance to surveillance, defined as ‘disrupting flows of information from the body to the information system’ (Ball Citation2005, p. 104). Resistance can be seen as conscious and strategic choices made by citizens when confronted with AI use by police, ranging from technical and social counterstrategies (such as the use of Electronic Frontiers Foundation tools mentioned above), to obfuscation or the decision to remove oneself from online spheres (Bayerl et al. Citation2021). Marx (Citation2009) further proposed neutralisation strategies as common reactions, which he defined as a ‘dynamic adversarial social dance’ (p. 99) whereby opponents reciprocate in performing innovative moves in a chain reaction of surveyed versus surveyor to neutralise surveillance/ countersurveillance consecutively. In this ‘social dance’ citizens often exhibit moral dilemmas that are conditional to the specifics of the usage context and type of AI deployed (e.g. Carrasco et al. Citation2019).

Overall, these studies indicate that contextual and psychological factors contribute to shaping attitudes. However, past inquiries provide insufficient insights to allow a clear understanding of the sense-making by citizens when it comes to balancing their stance towards AI use by police forces. Investigating citizens’ sense-making affords a view into the rationales and the ‘checks and balances’ when considering the complex issue of AI use by police which provides a foundation for observable disparities in attitudes and reactions. This exploratory study aims to obtain an understanding of the rationales for citizens’ subjective positions about police use of AI with a view to untangle the rhetoric between ‘safety versus privacy’. Such an exploration is particularly important in the light of the impact of expanding technology on citizens’ freedoms and self-expression abilities, whereby a balanced stance is needed to equally acknowledge the benefits and the risks of AI, and to account for societal concerns and ramifications of modern police surveillance in the context of perceptions, acceptance, and resistance. This study therefore had two interlinked aims: (1) to identify subjective positions towards AI use by police beyond mere acceptance–rejection; (2) to identify the rationales and sense-making that underly disparate subjective positions towards AI use by police.

2. Methodology

This study used Q methodology in combination with interviews (Brown Citation1993). As a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches, Q methodology is an exploratory approach that offers ‘a means of capturing subjectivity – reliably, scientifically and experimentally’ (Watts and Stenner Citation2012, p. 44) and as such has been applied to numerous fields in which subjective perspectives and sense-making are relevant (e.g. social and health related studies; cp. Chururcca et al. Citation2021, Stenner et al. Citation2000).

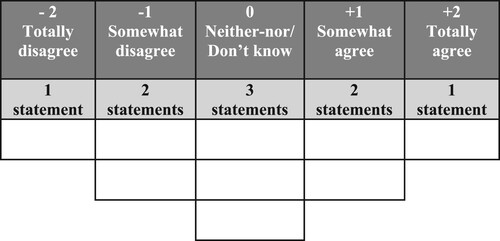

Q methodology uses a set of pre-defined statements that together represent a range of disparate positions towards the issue in questions, in our case AI use by police forces. Participants are then instructed to sort the statements into a predefined distribution according to their agreement/disagreement with each statement (for details see section on data collection below). Using a forced distribution is the standard approach and coincides with Stephenson’s notion of psychological significance (Burt and Stephenson Citation1939) that influences participants into reflecting on the precise psychological significance to each statement.

2.1. Q statement set

The Q statement set consisted of nine statements. The statements were created based on results from previous research by the authors which explored citizen acceptance as well as surveillance reactions (Bayerl et al., Citation2021). The statements were chosen to represent disparate perspectives, which also integrate stances from (supportive) security and (critical) surveillance fields. The set addresses three aspects: (1) the tension between privacy versus safety considerations offering disparate options for resistance from ‘low-key’ to destructive; (2) a differentiation between use of AI capabilities in online (i.e. on digitally enabled platforms) versus offline settings (i.e. real life, on the streets, in public spaces …) and (3) the tension between benefits for oneself versus others. The statements were purposefully formulated as extreme positions (using markers such as ‘need to’, ‘never’, ‘totally’) to elicit strong responses from participants. A pilot-test was conducted with two volunteers who did not take part in the actual study later-on. This was done to ensure that the statements were clear and elicited useful responses. The volunteers suggested adjustments to some of the statements to reduce their complexity and make them clearer. For instance, the abstract formulation ‘avoid facial recognition AI’ was replaced with the more concrete ‘prevent AI systems from capturing my face and movements’ (statement 4) and ‘not to post things’ was replace with ‘to never post pictures or other personal information’ (statement 2). The latter is also an example of strengthening statements to elicit stronger reactions (‘never post’ instead of ‘not to post’; similarly statements 9: ‘if their presence may lead’ to ‘if their presence leads to...’). The resulting statement set can be found in .

Table 1. Complete list of Q sort statements presented to participants for distribution.

2.2. Participants

Participants stemmed from three countries: the UK, Netherlands, and Germany. The rationale for a multi-national sample was to provide scope for the emergence of diverse opinions on AI use by police. The three countries represent similar policing approaches (i.e. an emphasis on community-led policing), while being known for disparities in the uptake of and attitudes towards AI use of police. The selection of these three countries was also owing to the familiarity of the authors with the countries (citizens of UK and Germany, respectively, one with over a decade of experience living in the Netherlands) which assisted in the translation and interpretation of the collected data.

The study was conducted as part of an international research project. The participants were recruited by researchers in the respective countries. Country teams were given freedom to recruit a group of interest in their specific country. The only selection criterion was an age of 18 or older for reasons of ethical consent. Overall, we received information from 43 participants: 16 each from the Netherland and Germany, 11 from UK.Footnote5 The German sample focused on young women (average age 26.3 years), the Netherlands on participants with cybersecurity expertise (seven women, nine men, average age 32.2 years), while the UK sample focused on people with a migration background (nine women, three men, average age 33.4 years), leading to 72.2% women and an average age of 30.4 years for the full sample. shows the demographics and gender characteristics of the selected groups. As this overview shows, the overall sample has an imbalance towards women and younger people, which will be considered in the interpretation of the data.

Table 2. Characteristics of citizens interviewed per country.

2.3. Ethics

The study received approval by the ethics committee of the authors’ university. Additionally, participants received an information sheet to clarify the context and legal basis of the study, details of data handling and participants’ rights. This included the right to withdraw and not provide demographic information if they did not feel comfortable doing so. All data was analysed in pseudonymised form.

2.4. Data collection

Interviews were conducted by the researchers in their respective countries to ensure interviewers were familiar with the national culture and context. In the UK and the Netherlands, interviews were held in English. In Germany, statements were translated into German. The translation was validated by the second author, who is a native German speaker, and thus well-positioned to ensure that the translated statements carried the same meaning and intent as the original versions.

The Q sort interviews were conducted with each participant individually either face-to-face or online. Participants were presented with the nine statements on an A4 paper aligned with the chart represented in . For remote participants (i.e. over Zoom or Microsoft Teams), the Q sort template was sent by email to fill out locally or researchers would share their screen allowing participants to view the document. Participants were then instructed to fit the statements into the forced distribution according to how much they agreed/disagreed with the statement. In face-to-face interviews, participants filled in the paper form. For remote participants, the researcher filled in the statements on a local copy as the participant announced their choice. Participants were encouraged to elaborate on the rationales for their placement of statements which provided critical background information for the interpretation of sorts and factors. All interviews were audio-recorded.

2.5. Data analysis

The analysis of Q sorts allows to identify clusters of participants with similar subjective perspectives (Ellingsen et al. Citation2010). This process is purely exploratory, i.e. the analysis does not use any pre-imposed categories or features in creating the clusters. Hence, clusters (or Factors, in Q sort terminology) emerge bottom-up from the data with individuals who share similar views loading on the same Factor. The subsequent analysis of the Factors, together with participants’ comments, is the core analytical measure of Q methodology (McKeown and Thomas Citation1988) by investigating the pattern of agreements to the items within a Factor, as well as the degree of agreement and disagreement between perspectives.

Using Peter Schmolck’s PQ software package (Schmolck Citation2014), a Centroid Factor analysis was conducted. As a standard the software extracts seven Factors (Brown Citation1980, p. 223). Several criteria are used to determine the correct number of Factors to be extracted. Firstly, Eigenvalue (EV) analysis revealed five Factors with an EV larger than the 1.00 cut-off (see ). A Scree test (Watts and Stenner Citation2012), as a common addition to statistical tests, was less conclusive suggesting between three to five factors, while applying Humphrey’s rule eliminated two Factors due to standard errors below the cut-off point, suggesting retention of three Factors. However, retention of only three Factors would mean disregarding a considerable number of participants (9 out of 43), which would be risky, since significant viewpoints can be overlooked as a result, especially given the diversity of our sample. Following Brown (Citation1980), we proceeded with five Factors to allow the emergence of potentially less prevalent but important viewpoints. The final solution (using Varimax rotation; complemented by manual flagging of Q sorts with loadings greater than 0.39) found that all but one Q sort loaded on the five Factors. Therefore, the 5-Factor solution was chosen representing an explained variance of 79%.

Table 4. Demographic distribution of participants across the five factors (ordered by explained variance).

The content of the five Factors (i.e. subjective perspectives) will be discussed in the Results section. The interpretation must adopt an open-minded, careful, and comprehensive assessment of the patterns found across the perspectives. This was accomplished by examining the relative ranking of each statement to understand the reasoning and viewpoints being reflected in each Factor. Additionally, the interpretation of Factors was crucially supported by the comments and reflections made by participants during or after completing the sort. We conducted a thematic analysis of the transcripts with a focus to understand the rationales for specific sorting decisions. Our analysis approach was primarily inductive (Patton Citation1990, Braun and Clarke Citation2006) in that we did not have pre-determined themes for the potential rationales, participants may use to make their sorting decisions. Rather the rationales emerged from the comments about specific items, which could then be compared across perspectives (e.g. disparate reactions to statement 8: UK06: it’s actually a good thing, knowing that AI systems are working in that way indicating acceptance due to strong safety benefits vs UK10: You shouldn’t change your behaviour, just thinking you’re being watched; especially when, when you’re not doing anything against law indicating high value given to free expression). The analysis was done using the qualitative analysis package NVivo, and revealed complex attitudes and varied themes of acceptance, resistance and reactions to AI use by police forces.

3. Results

The subsequent sections provide a description of each perspective, followed by a comparison to draw out overlaps and specifics of each. In the descriptions, numbers such as (6: +2) indicate the statement number (cp. ) and its ranking on the specific Factor. For instance, in the example (6: +2), statement 6 has been ranked in the +2 position (totally agree). The comments made by participants during or after sorting are cited in italics to support interpretation and to enhance understanding. We have also provided a title for each perspective to clarify and emphasise the core aspects of each viewpoint.

3.1. Perspective 1: ‘privacy first’

Ten participants shared this viewpoint. To this group of citizens, privacy was the greatest concern. Participants considered it highly appropriate to falsify personal information online to protect their privacy, even if this means that police AI systems fighting against cybercrime and terrorism may be less accurate as a result (1: +2). As the following quote shows, this was less driven by worries about police surveillance than a general fear of revealing too much: If I feel safer behind a pseudonym, then I should be allowed to use it to protect myself against bad actors who might attack me (GER01). This was also supported by negative reactions to statements relating to the moral responsibility of sharing accurate information (6, −1) and putting other people’s safety first (3: −1), further reinforced by participant NL09: I totally disagree with 6, because I personally do that, I hide or distort information like my birthday. I don’t give the correct year or month.

Moreover, asking friends and family to never post anything about them (2: +1) and avoiding public spaces to prevent police AI systems from capturing their personal information (4: +1) were seen as favourable, reinforcing the Privacy First perspective also in the offline domain. At the same time, participants felt neutral towards high-level resistance measures: the destruction of facial recognition cameras and expecting people to act differently in crowds to avoid being flagged by AI systems (9, 8: 0). They further felt neutral about resistance being a bad idea (7: 0). What further distinguishes the Privacy First perspective from other positions is their strong opposition against police monitoring of behaviours online but not offline (5: −2). This was expressed clearly by participant GER02: For me there is no difference between online surveillance and surveillance offline in public places, again indicating the importance of privacy in both contexts.

3.2. Perspective 2: ‘safety first’

At the opposite end stands the ‘Safety First’ perspective in which participants strongly agreed to AI systems by police monitoring their online behaviours for security purposes (5: +2). This viewpoint acknowledges a moral responsibility to put other people’s safety above own privacy concerns (3: +1), which was also clearly phrased by UK02: People’s safety is more important than anything else for me. Safety consciousness extended to asking friends and family to never post pictures about them online (2: +1) or at least be consulted. According to GER05: For me it is OK if pictures of me are posted by others, but I would always like to be asked first. Safety First participants were neutral towards the proposition that hiding or distorting information would be immoral (6: 0) and, in contrast to the Privacy First position, also had a neutral stance towards falsifying personal information online if it may lead to less accurate police systems (1: 0). As put by GER09: The statement 6 does not say for what reason people might wish to hide certain data and information. Such people could have a legitimate interest to do so or their reasons damage society. The same is true for the need to avoid public spaces to prevent police AI systems from capturing personal information (4: 0).

Conversely, Safety First proponents disagreed that people should stop behaving aggressively in crowds when AI systems are being used (8: −1). They also disagreed with the notion that trying to resist or avoid AI systems by police would lead to the development of better AI capabilities by the latter (7: −1) based on the belief that there is somewhat [of an] inevitability about it, being something that will happen in future (UK04). Similarly, these participants completely disapproved the destruction of facial recognition cameras even if they cause over-policing (9: −2). As expressed by GER16: If any policing takes place, then this happens for a good reason which is to keep the area safe. And if the result is over-policing, then the objection should not be destruction of the cameras. This clearly emphasises acceptance and trust in AI police measures for protection.

3.3. Perspective 3: ‘protective AI’

The third perspective saw considerable benefit for AI, as long as it was used for the protection of themselves or society. Unlike the previous perspectives, this group felt very positive towards AI’s potential to stop aggressive behaviours in crowds giving it a preventive purpose (8: +2); e.g. GER06: this scenario seems to prevent aggressive behaviour in advance, but I do not think that every aggressive act would immediately be super suspicious. Nevertheless, I can imagine that overall, the behaviour would become much more pleasant and more respectful through the use of such AI systems. Similarly, people with a Protective AI perspective disagreed with the need to avoid public spaces to avoid AI systems (4: −1) and even more with the destruction of facial recognition cameras (9: −2) demonstrating a strong supportive view of AI. In addition, this perspective felt a moral obligation to put other people’s safety first, even if this meant not masking own behaviours towards AI (3: +1). At the same time, this perspective attaches importance to privacy such as asking friends and family to not share personal information about them online (2: +1); e.g. I find my privacy should be protected and for me, in this respect, the question is what exposes my personal data. If I do not put my data online myself, then my family and friends should not make these data available (GER15). Similarly, UK08: I agree but it has nothing to do with artificial intelligence police system, it’s anybody, I would not want anybody to track me or to see where I am. This indicates that generally, this perspective appreciates privacy, however, sees a clear value in AI systems for safety purposes including as preventive measure.

3.4. Perspective 4: ‘not me’

Participants with this viewpoint want ‘the best of both worlds’, requesting security as long as it does not infringe on their own life and privacy. Security and privacy are seen as opposing options: Because of the natural antagonism between security and privacy, the guarantee of privacy seems to reduce the level of security (GER02). In line with a positive security stance, they strongly disagreed that falsification of information is appropriate if this infringes on police AI systems (1: −2). They moreover strongly agreed with having a moral responsibility to put other people’s safety first (3: +2). On the other hand, they did not find resistance against AI capabilities problematic (7: −1), while seeing the necessity to avoid public spaces to prevent police AI systems from capturing their information (4: +1) and to ask their friends and family to never post pictures of them online (2: +1). Interestingly, statements about the behaviours of others, either in terms of hiding/distorting information, aggression in public spaces or the destruction of facial-recognition cameras received neutral reactions (6, 8: 0). This suggests a focus foremost on their own personal situation, which contrasts with the Safety First perspective which focuses on security including others.

3.5. Perspective 5: ‘Anti-surveillance’

The Anti-surveillance viewpoint is characterised by its clear acceptance of resistance. This group approved most strongly of asking friends and family to never post pictures of them online (2: +2), and not only for police avoidance. According to participant GER10: I would ask my family and friends not to post pictures of me for other reasons than to prevent AI systems of the police from collecting them. Moreover, this group was the only one that approved of the destruction of facial recognition cameras in areas where they may lead to biased over-policing (9: +1). This is clearly expressed by participant UK05: It doesn’t matter. If it’s bothering someone, they can destroy it, if it’s harming them. Moreover, they did not perceive hiding/distorting of personal information online as immoral even if it infringes on security (6: −1). The Anti-Surveillance stance was also expressed in emphasising that people should be able to act as they wish without worrying about police AI systems flagging them up as suspicious (8: −1) and strong disagreement to the claim that people should avoid public spaces to prevent police AI systems from capturing their personal information (4: −2; e.g. No, I do not agree with this statement because the restriction to freedom is way too high. For me, it is not acceptable if it became impossible to walk around incognito as nobody, GER12). At the same time, they acknowledged a moral responsibility to put other people’s safety before their personal privacy concerns (3: +1), which indicates that even the Anti-Surveillance position sees merit in some policing measures.

3.6. Comparison of perspectives

provides a direct comparison of statement rankings. Comparing the five viewpoints reveals several shared and common reactions towards AI use by police, but also presents insightful disparities in the sense-making and the challenge of balancing between privacy and safety. Essentially, the Privacy First group comprises citizens who prioritise privacy. However, they are neutral towards the destruction of facial recognition cameras, resistance, and aggressive behaviours in crowds, which signals a non-violent stance that contrasts strongly with the Anti-surveillance perspective. The Anti-Surveillance perspective encourages resistance, including but not only against police. This indicates a generalised opposition to sacrificing their freedoms of expression (both online and offline/in public spaces) as a price for safety, if needed condoning aggressive means. The Safety First perspective is strongly concerned about safety in a broad sense that includes a moral responsibility to sacrifice personal privacy concerns for the sake of other’s protection. The Safety First perspective thus represents a strong collective orientation towards safety and security, which surpasses many concerns around AI use by police forces that are pronounced in other perspectives. The Not Me viewpoint can be seen as representing the other end of the spectrum. Proponents are generally in favour of AI use by police if it safeguards themselves, although preferably not on their own data. Not Me individuals thus primarily prioritise the own personal safety along with personal privacy. The Protective AI viewpoint emphasises the benefit of AI systems if applied for security purposes. At the same time, privacy concerns ranked high, while moral responsibility did not receive much attention. This perspective thus represents a narrower stance about AI with a somewhat ambiguous view that lacks a clearly integrated position.

Table 3. Statement rankings across the five factors (ordered by increasing disagreement across factors).

Considering the demographic characteristics across perspectives, no single Factor was dominated by participants from a single country or group: all perspectives included representatives from all three countries and similar gender distributions (cp. ). This suggests that perspectives are founded on individual aspects and experiences rather than overt demographics such as country origin, gender, or age. That is, for the sense-making about AI use by police forces, other personal aspects seem more relevant than national context or membership in a specific professional or demographic group.

One person did not fall into the 5-factor solution. This participant (NL, male, 20 years) expressed views that oscillated between concerns for privacy and wanting to ethically contribute to safeguarding society. The participant was in favour of AI generally but believed that AI tools should only be owned by the police. This participant thus represents a view that wavered across factors, integrating aspects from several perspectives.

4. Discussion

This study set out to gain an understanding of citizens’ perspective to AI use by police forces. The five perspectives identified in our data demonstrate the variation in citizens’ viewpoints with disparate foci on general versus personal safety, privacy and potentials for moral dilemmas and acceptance of (aggressive) counter-reactions. The findings have important theoretical and practical implications by providing insights into the complexities of citizen reactions around AI use in the policing and security domain.

Crucially, our observations demonstrate the different ways in which individuals make sense of AI use by police, highlighting the checks-and-balances and moral or rationale bases for their views. For instance, citizens of the Safety First group did not oppose surveillance or AI use (online and offline), because they argue that monitoring is essential if police want to keep citizens safe, especially with the increasing challenges that police forces face with respect to social media and cybercrimes (David and Williams Citation2013). This resonates with the proposition of ‘fear of crime’ as a corner stone in community policing (Leman-Langlois Citation2002). Similarly, for citizens adhering to a Protective AI perspective, AI’s positive outcomes – reflected in possibilities for the successful identification, screening, case linkage and other labour and time reducing functionalities (UNICRI and INTERPOL Citation2019) – can overcome some concerns about their privacy.

Discussions around police surveillance have been marked by notable theories drawing from Jeremy Bentham’s early Panopticon (Citation1791) that motivated numerous discussions around the costs versus benefits of surveillance (Foucault Citation1991, Orwell Citation2000), and deliberations around privacy and legality of overt and covert police surveillance (Foucault Citation1977, Marx Citation1988, Regan Citation1995). These were also issues, citizens sharing the Safety First and Protective AI viewpoints touched upon when stressing the need for a balanced implementation of AI to safeguard society, while ensuring basic human rights are not violated. This coincides with the ‘trade-off’ approach proposed by Pavone and Esposti (Citation2012), where citizens trade, to a certain degree and in specific situations, their privacy, in exchange for enhanced security. The position is also in line with past studies which have shown that citizens are often more supportive of surveillance mechanisms than police officers would perceive (Nalla et al. Citation2018, Gurinskaya Citation2020). Crucially, only a small number of participants exhibited a complete rejection of the implementation of AI tools by police (visible in the Anti-Surveillance stance).

Subtle differences emerged in terms of the balance between privacy (emphasised by the Privacy First and Anti-Surveillance groups) versus safety (emphasised by the Safety First and Protective AI groups) and foci of considerations – most notably a limited, personal conception versus a more generalised conception of safety. Moreover, we identified subtleties between stances that accept peaceable counter-reactions (e.g. not posting content) and those that accept more radical ones (e.g. destruction of cameras). These disparities in viewpoints provide explanations underlying the different positions observed in ongoing debates as well as overt citizen reactions.

Strong privacy perspectives correlate with those of various civil parties, members of academia and expert advisors who question the efficacy of AI technologies by deeming their performance ‘limited’ and their potential to reduce risk of algorithmic decisions as ambiguous and imprecise (Rovatsos et al. Citation2019), as well as those who call for in-depth evaluations and determination of the cost-benefits analysis incurred on civil rights and freedoms (Benjamin Citation2020). These perspectives also correlate to studies revealing that individuals frequenting public and private areas are wise to, and capable of, eluding and deceiving surveillance (EDRi and EIJI Citation2021).

The perspectives further provide insights into the underlying strategies and reasonings for resistance. Numerous studies revealed that the public’s resort to resistance and counterstrategies, in various forms of ‘veillance’ (Mann and Ferenbok Citation2013), is an effort to ‘equalize’ the power that the surveyor has over the surveyed (Dencik et al. Citation2016). This is particularly true for the ‘Anti-Surveillance’ stance. For some citizens, AI is best employed by police for protection and safeguarding purposes only (Protective AI group), while others support AI tools to be implemented, just not on themselves (Not Me group). The latter may be attributable to the uncertainty around AI’s ethical and moral implications (Lyon Citation2002, DiVaio et al. Citation2022, Westacott Citation2010), which is also visible in citizens’ reactions to the statements, despite the general acknowledgment of its potential for public protection.

By comparing the perceptions and viewpoints emerging from the Q sorts, it becomes apparent that the reality of attitudes and potential resistance responses towards AI use by police forces is highly complex, and that the notions of privacy and security or acceptance and rejection of AI use by police can often exist next to each other. The Not Me group can serve as a unique exemplar of the paradox of thought between safety and privacy, as these citizens want the advantages of safety and the benefits of privacy, all at once. They are generally in favour of AI use by police, which ultimately contributes to general safety, but not on their own personal data, which allows them to enjoy their own privacy. Hence, they want the best of both worlds. According to Solove (Citation2011, p. 14), ‘privacy is often misunderstood and undervalued when balanced against security’. This study revealed that citizens perceptions of privacy are much more complex than often portrayed. In fact, most individuals did not perceive AI use by police as an either/or scenario but offered differentiated arguments and contextualisation hinting towards situational, demographic, cultural and political factors.

Overall, our study provides an in-depth view on the range and complexity of attitudes justified by moral, ethical, and practical considerations around collective and personal safety and benefits of AI tools. The discrepant perspectives also explain the nature of accepted resistance (legal resistance routes versus destructive and illegal behaviours) and the personal duties and contributions towards general safety. This demonstrates that citizen perspectives towards AI use by police are much broader than often assumed, driven by reflections and propositions around acceptance, safety considerations and moral responsibility. Understanding the underlying rationalisations expands and refines pre-existing notions on surveillance and resistance and provides new pathways for the exploration of citizen reactions to the rapidly changing security environment. Our findings also shed light on the antimony between acceptance versus rejection of new technologies in the context of policing, along with the shifting attitudes towards personal privacy compared to personal and general safety.

In other words, the findings of this study not only expand on existing approaches to surveillance and resistance in the security area, but also address the gap in understanding the rationales behind the often ambiguous stance of citizens about acceptance and rejection of AI capabilities deployed by police. The contributions further include under-researched aspects, namely resistance factors and triggers that warrant the resort to counterstrategies in response to police use of AI. This research contributes to unpicking the binary narrative about ‘safety versus privacy’ by evaluating the rationale behind the costs and benefits of security measures, and how citizens balance privacy and security.

In practical terms, our exploration of citizens’ perspectives offers a more promising avenue for police forces and policy makers to engage with public opinions and reactions. Engagements are often based on the assumption of a generalised resistance. This study helps recognise the complexity of sense-making, including benefit perspectives as well as moral and personal tensions and reflections on counter-reactions. Understanding this range and disparity of perspectives allows practitioners to better address and integrate the specific citizen concerns and expectations.

4.1. Limitations and future work

Q methodology as a qualitative interpretation method (Watts and Stenner Citation2012) is well-suited to the study of subjective viewpoints by people within a specific context (Curt Citation1994), but it is not without limitations. The reflections and open-ended comments made by participants during and after the sorting exercise revealed that participants, although unaccustomed to the nature of a forced choice distribution, found that the Q sort challenge provided them with a unique opportunity to reflect on their opinions and stances towards AI application by police and that item rankings triggered reflection processes. Some statements contained two propositions and negative formulation (e.g. I don’t) which for some participants required further clarification. This was not addressed by the participants in the pilot yet emerged during a small number of interviews. These items yielded important insights into reasons for agreement or disagreements towards specific aspects within a statement. In the rare event where participants agreed with one aspect of the statement but not the other, their rationales for focusing on one specific aspect provided crucial pointers to their sense-making.

This study did not include older participants (over 60s) and a higher number of women. We would therefore be cautious to claim that the five perspectives which emerged in this study are comprehensive of the viewpoints and perspectives around AI deployments generally. However, they do provide important insights into the complexity of reasoning around AI use by police, and the cognitive, and at times emotional, balancing acts that individuals perform. Future work can benefit from exploring these disparate viewpoints for a broader investigation into rationalisations and sense-making around AI-based surveillance and the morality of resistance. Relatedly, the three groups across the three countries differed in important aspects, most markedly cyber-expertise, and migration experience. Although our analysis did not reveal a pattern, it cannot be ruled out that they are confounding influences. A quantitative approach to comparing perspectives amongst demographics different groups would help to ascertain potential influencing factors as underlying reasons for disparate views.

Lastly, this study is a first exploration and should be followed up by studies that address the behavioural manifestations of subjective perspectives in its various forms, including counter-reactions towards police use of AI tools. The impact of the disparate perspectives towards AI deployments by police on actual behaviours and reactions remain important questions for future studies and the different factors that shape citizens’ opinions and reactions.

5. Conclusion

Doubtless, applications of AI in policing can trigger uncertainty and scepticism around the ethical and moral ramifications of AI deployments (Feldstein Citation2019, Heaven Citation2020, McGuire Citation2020). In the light of on-going debates around AI implementations and the needed regulations and legislations, public opinions need to be taken seriously to allow informed decision-making about the adoption of AI for policing purposes. A pre-requisite, however, is an equally informed understanding of citizen perspectives. Current debates are often framed around binary positions of ‘either security or privacy’ which, as our study illustrates, is too restrictive. Our study offers a crucial window into the areas between these two extremes as expressed by citizens themselves. Generating a bird’s eye view into societal concerns emanating from expanded technological advances in the security field is essential in the process of establishing legitimate means for AI applications in policing. A realistic understanding of citizen perspectives allows to account for citizen concerns adequately and ultimately to safeguard the relationship between the police and the public, whether through policy, regulations, or incorporating aspects that trigger concerns into the design and usage of AI tools.

Acknowledgements

For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

5 The range emerged as countries were allowed to recruit a mixed sample of citizens (minimally 11) and security stakeholders (up to five). Since Q sorts are intended to capture subjective perspectives on an individual level, the interviews with security stakeholders – focusing on an organisational perspective – did not contain a Q sort. While the other countries only interviewed citizens, the UK conducted interviews with a mix of stakeholder (citizens and Civil Society Actors representing organisations engaged in fighting cybercrime and terrorism) leading to 11 citizen Q sorts for the UK.

References

- Akhgar, B., et al., 2022. Accountability principles for artificial intelligence (AP4AI) in the internet security domain. AP4AI Project. Available from: https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/Accountability_Principles_for_Artificial_Intelligence_AP4AI_in_the_Internet_Security_Domain.pdf [Accessed 12 March 2022].

- Amnesty International., 2015. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2015/03/global-opposition-to-usa-big-brother-mass-surveillance/

- Babuta, A. and Oswald, M., 2020. Data analytics and algorithms in policing in England and Wales. RUSI. Available from: https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/projects/data-analytics-and-algorithms-in-policing [Accessed 22 March 2022].

- Ball, K., 2005. Organization, surveillance, and the body: towards a politics of resistance. Organization, 12 (1), 89–108.

- Bayerl, P.S., et al., 2021. Artificial intelligence in law enforcement: cross-country comparison of citizens in Greece, Italy and Spain. S. N.-R. Intelligence: Springer Nature, 11769.

- Benjamin, G., 2020. Facial recognition is spreading faster than you realise. The Conversation. Available from: https://theconversation.com/facial-recognition-is-spreading-faster-than-you-realise-132047 [Accessed 15 February 2022].

- Bentham, J., 1791. Panopticon, or, the inspection-house. Dublin, Ireland Printed: London Reprinted: T. Payne.

- Bradford, B., et al., 2020. Live facial recognition: trust and legitimacy as predictors of public support for police use of new technology. SocArXiv. doi:10.31235/osf.io/n3pwa.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3 (2), 77–101.

- Brown, S.R., 1980. Political subjectivity: applications of Q methodology in political science. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Brown, S.R., 1993. A primer on Q methodology. Operant subjectivity, 16 (3/4), 91–138.

- Burt, C. and Stephenson, W., 1939. Alternative views on correlations between persons. Psychometrika, 4 (4), 269–281.

- Bushway, S., 2020. Nothing is more opaque than absolute transparency: the use of prior history to guide sentencing. Harvard data science review, 2 (1). doi:10.1162/99608f92.468468af.

- Carrasco, M., Mills, S., Whybrew, A. and Jura, A. 2019. The Citizen’s Perspective on the Use of AI in Government. BCG Digital Government Benchmarking. Retrieved from https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/citizen-perspective-use-artificial-intelligence-government-digital-benchmarking.aspx

- Churruca, K., Ludlow, K. and Wu, W, 2021. A scoping review of Q-methodology in healthcare research. BMC Med Res Methodol, 21, 125.

- Committee of the Regions for Artificial Intelligence in Europe Brussels, 2018. AI Communication from the Commission to the EU Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the regions on Artificial Intelligence for Europe. Brussels: Europe. Available from: AI Communication (europa.eu).

- Curt, B., 1994. Textuality and tectonics: troubling social and psychological science. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- David, S.W. and Williams, L.M., 2013. Policing cybercrime: networked and social media technologies and the challenges for policing. Policing and society, 23 (4), 409–412. doi:10.1080/10439463.2013.780222.

- Davis, D. and Silver, B., 2004. Civil liberties vs. security: public opinion in the context of the terrorist attacks on America. American journal of political science, 48 (1), 28–46. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00054.

- Dencik, L., Hintz, A., and Cable, J., 2016. Towards data justice? The ambiguity of anti-surveillance resistance in political activism. Big data & society, 3 (2). doi:10.1177/2053951716679678.

- Di Vaio, A., Hassan, R., and Alavoine, C, 2022. Data intelligence and analytics: A bibliometric analysis of human–Artificial intelligence in public sector decision-making effectiveness. Technological Forecasting and Social Change (174), 121201. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121201.

- EDEN Europol Conference Report, 2018. Freedom AND security killing the zero-sum process #kill0sum. Available from: https://www.europol.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/report_of_eden_conference_freedom_and_security_2018.pdf.

- Ellingsen, I., Størksen, I., and Stephens, P., 2010. Q methodology in social work research. International journal of social research methodology, 13 (5), 395–409.

- European Digital Rights and Edinburgh International Justice Initiative, 2021. The rise and rise of biometric mass surveillance in the EU report. Brussels: EDRi and EIJI. Available from: https://edri.org/wpcontent/uploads/2021/11/EDRI_RISE_REPORT.pdf [Accessed 3 April 2022].

- Feldstein, S., 2019. The global expansion of AI surveillance. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available from: https://www.carnegieendowment.org/2019/09/17/global-expansion-of-ai-surveillance-pub-79847/ [Accessed 17 April 2022].

- Foucault, M., 1977. Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. New York: A Division of Random House, INC. Vintage Books.

- Foucault, M., 1991. Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. London: Penguin Books.

- Fussey, P., Davies, B., and Innes, M., 2021. ‘Assisted’ facial recognition and the reinvention of suspicion and discretion in digital policing. The British journal of criminology, 61 (2), 325–344. doi:10.1093/bjc/azaa068.

- Fussey, P. and Sandhu, A., 2022. Surveillance arbitration in the era of digital policing. Theoretical criminology, 26 (1), 3–22. doi:10.1177/1362480620967020.

- Getting the future right: artificial intelligence and fundamental rights. European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2021. Available from: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2021-artificial-intelligence-summary_en.pdf.

- Gurinskaya, A., 2020. Predicting citizens’ support for surveillance cameras. Does police legitimacy matter? International journal of comparative and applied criminal justice, 44 (1–2), 63–83. doi:10.1080/01924036.2020.1744027.

- Heaven, W., 2020. Predictive policing algorithms are racist. They need to be dismantled. MIT Technology Review. Available from: https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/07/17/1005396/predictive-policing-algorithms-racist-dismantled-machine-learning-bias-criminal-justice [accessed April 4, 2022].

- Jahankhani, H., et al., 2020. Policing in the era of AI and smart societies. Champ: Springer.

- Kaufmann, M., Egbert, S., and Leese, M., 2019. Predictive policing and the politics of patterns. The British journal of criminology, 59 (3), 674–692. doi:10.1093/bjc/azy060.

- Lee, N. and Chin, C., 2022. Police surveillance and facial recognition: why data privacy is an imperative for communities of color. Brookings. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/research/police-surveillance-and-facial-recognition-why-data-privacy-is-an-imperative-for-communities-of-color/.

- Leman-Langlois, S., 2002. The myopic panopticon: the social consequences of policing through the lens. Policing and society, 13 (1), 43–58. doi:10.1080/1043946022000005617.

- Lockey, S., Gillespie, N., and Curtis, C., 2020. Trust in artificial intelligence: Australian insights. The University of Queensland and KPMG Australia. Available from: https://www.assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/au/pdf/2020/public-trust-in-ai.pdf [Accessed 10 March 2022].

- Lyon, D., 2002. Everyday surveillance: personal data and social classifications. Information, communication & society, 5 (2), 242–257. doi:10.1080/13691180210130806.

- Mann, S. and Ferenbok, J., 2013. New media and the power politics of sousveillance in a surveillance-dominated world. Surveillance & society, 11 (1/2), 18–34.

- Marx, G., 1988. Undercover: police surveillance in America. Berkley: University of California Press.

- Marx, G., 2009. A tack in the shoe and taking off the shoe neutralization and counter-neutralization dynamics. Surveillance & society, 6 (3), 294–306.

- McGuire, M., 2020. The laughing policebot: automation and the end of policing. Policing and society, 31 (1), 20–36.

- McKeown, B. and Thomas, D., 1988. Q methodology: quantitative applications in the social sciences. London: Sage.

- Metropolitan Police and NPL, 2020. Metropolitan police service live facial recognition trials. Available from: https://www.met.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/media/downloads/central/services/accessing-information/facial-recognition/met-evaluation-report.pdf.

- Morgenstern, J., et al., 2021. ‘AI’s gonna have an impact on everything in society, so it has to have an impact on public health’: a fundamental qualitative descriptive study of the implications of artificial intelligence for public health. BMC public health, 21 (1), 40. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-10030-x.

- Moses, B.L. and Chan, J., 2016. Algorithmic prediction in policing: assumptions, evaluation, and accountability. Policing and society, 28 (7), 806–822. doi:10.1080/10439463.2016.1253695.

- Nalla, K.M., Gorazd, M., and Maja, M., 2018. Assessing police–community relationships: is there a gap in perceptions between police officers and residents? Policing and society, 28 (3), 271–290. doi:10.1080/10439463.2016.1147564.

- Neudert, L.M., Knuutila, A., and Howard, P., 2020. Global attitudes towards AI, machine learning & automated decision making. Implications for involving artificial intelligence in public service and good governance. Oxford: University of Oxford: Oxford Commission on AI & Good Governance.

- Orwell, G., 2000. 1984 nineteen eighty-four. Berkley: Penguin Random House.

- Oswald, M., et al., 2018. Algorithmic risk assessment policing models: lessons from the Durham HART model and ‘experimental’ proportionality. Information & communications technology law, 27 (2), 223–250. doi:10.1080/13600834.2018.1458455.

- Patton, M.Q., 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd ed. New Bury Park, CA: Sage.

- Pavone, V. and Esposti, S., 2012. Public assessment of new surveillance-oriented security technologies: beyond the trade-off between privacy and security. Public understanding of science, 21 (5), 556–572. doi:10.1177/0963662510376886.

- Quattrocolo, S., 2020. Equality of arms and automatedly generated evidence. In: Lorena Bachmaier Winter, ed. The artificial intelligence, computational modelling and criminal proceedings. Italy: Springer International Publishing, 73–98.

- Regan, P., 1995. Legislating privacy: technology, social values, and public policy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Rovatsos, M., Mittelstadt, B., and Koene, A., 2019. Bias in algorithmic decision making. The University of Edinburgh: Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation. UK Government. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/landscape-summaries-commissioned-by-the-centre-for-data-ethics-and-innovation.

- Schmolck, P. 2014. PQMethod Software Package [Computer Software]. Retrieved from http://schmolck.org/qmethod/downpqwin.htm

- Schneier, B., 2012. How changing technology affects security. IEEE security & privacy magazine, 10 (2), 104–104. doi:10.1109/msp.2012.39.

- Smith, G., Moses, B.L., and Chan, J., 2017. The challenges of doing criminology in the big data era: towards a digital and data-driven approach. The British journal of criminology, 57 (2), 259–274. doi:10.1093/bjc/azw096.

- Solove, D., 2011. Nothing to hide: the false tradeoff between privacy and security chapter in NOTHING TO HIDE: THE FALSE TRADEOFF BETWEEN PRIVACY AND SECURITY. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Stenner, P., Dancey, C., and Watts, S., 2000. The understanding of their illness amongst people with irritable bowel syndrome: a Q methodological study. Social science and medicine, 51 (3), 439–452.

- Tounsi, W. and Rais, H., 2018. A survey on technical threat intelligence in the age of sophisticated cyber attacks. Computers & security, 72, 212–233. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2017.09.001.

- Trottier, D., 2017. ‘Fear of contact’: police surveillance through social networks. European journal of cultural and political sociology, 4 (4), 457–477. doi:10.1080/23254823.2017.1333442.

- Turner, E., Medina, J., and Brown, G., 2019. Dashing hopes? The predictive accuracy of domestic abuse risk assessment by police. The British journal of criminology, 59 (5), 1013–1034. doi:10.1093/bjc/azy074.

- United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI) and International Criminal Organization (Interpol), 2019. Artificial intelligence and robotics for law enforcement. UNICRI and Interpol. Available from: http://www.unicri.it/artificial-intelligence-and-robotics-law-enforcement [Accessed 20 April 2022].

- Urquhart, L. and Miranda, D., 2022. Policing faces: the present and future of intelligent facial surveillance. Information & communications technology law, 31 (2), 194–219. doi:10.1080/13600834.2021.1994220.

- Watts, S. and Stenner, P., 2012. Doing Q methodological research: theory, method, and interpretation. London: Sage.

- Westacott, E., 2010. Does surveillance make us morally better. Philosophy now, 79, 6–9.

- Završnik, A., 2020. Criminal justice, artificial intelligence systems, and human rights. ERA forum, 20, 567–583. doi:10.1007/s12027-020-00602-0.