Abstract

Large scale urban planning consultations can elicit public contributions with limited reflectivity and scope in comparison with participatory projects in HCI. We therefore investigated how digital technology can be configured to enable participation at greater depth and at scale in Metro Futures 2020 – an online public consultation on light rail trains. Drawing on participatory methods used in HCI, we devised experience-centered and creative activities at different depths and scales – from “shallow and wide” social media polls to “deep and narrow” online workshops – and a website with three ways of exploring a digital train mock-up. Participation on the website was both at scale and to notable depth according to our analyses of data entry behavior and website comments. Our findings show that the value of online public consultations can be increased through providing experiential context for design proposals, supporting exploration of design details via immersion, and providing interconnected activities of varying depths and scales.

1. Introduction

The prevalence and increased sophistication of digital technology in society has led to its increased use by governments and decision makers for citizen engagement (Balestrini et al., Citation2017; Corbett & Le Dantec, Citation2018). Despite this, approaches to engagement often fail to engage with the innovative potential new forms digital media offer. Cognizant of this, there are opportunities to apply insights from human computer interaction (HCI) to the larger public consultations associated with urban planning and related projects. These insights include means of digitally supporting deeper public involvement in “participatory projects” (McCarthy & Wright, Citation2015). However, public participation in such projects is usually at the scale of communities or workplaces (with some exceptions, e.g., Dalsgaard, Citation2012) whereas urban planning projects usually encompass entire cities or regions. HCI projects, particularly those characterized as Participatory Design (Simonsen & Robertson, Citation2013), can require months or years for designers and participants to generate the transformative outcomes intended (e.g., transformed practices) whereas participation in urban planning is usually over more rigid and shorter timeframes. Such differences between the depth (the degree of detail, reflection, and agency in discussions) and scale (the number of people included in discussions) of participation between HCI projects and planning projects suggest the need for caution in transferring methods and tools between them.

Whilst differing in depth and scale, the importance of involving people in design and urban planning processes has been developed conceptually and in practice for over fifty years, building on foundational research that introduced computer systems into 1970s workplaces (Greenbaum & Kyng, Citation1991) and Arnstein’s (Citation1969) critique of citizen power in urban planning consultation. In HCI, the value of participation has been framed as the democratic right for people to have a strong voice in the design of what affects them and a pragmatic consideration that exploring problems and potential solutions with people is an effective way to design (Robertson & Simonsen, Citation2013; c.f. Carroll & Rosson, Citation2007; Ehn, Citation1988). In urban planning, Rydin and Pennington (Citation2000) discuss a similar pairing, arguing that people have a “democratic right” to shape changes that affect their life, and that people, as experts of the difficulties and potential solutions in their local area, help develop “informed policy.”

Attaining the levels of democratic and pragmatic value observed in Participatory Design is a lofty ambition for participation in urban planning given the typically shorter timescales and bureaucratic processes involved, and a strict definition of what is and is not permissible to discuss (Bedford et al., Citation2002). However, democratic and pragmatic value do offer lenses through which to investigate the extent to which design/HCI methods can enable such value at scale in participatory projects.

Public transport (or mass transit) offers a relevant context in which to explore how methods and tools from design/HCI can be applied to larger-scale public consultations. Despite public transport’s significant role in people’s everyday lives, Vigar (Citation2017) observes that transport planning decisions are too often driven by “hunch, ideology and the push-and-pull of political force” (p. 39), taken through a “decide-announce-defend approach” (p. 44), rather than engaging with the current and prospective users of transport systems. Responding to such critiques, our research investigates how digital media and technology can enable the deeper participation of design/HCI projects at the larger scales of urban planning projects.

Tyne and Wear Metro (henceforth Metro) is a publicly-owned light rail network serving Northeast England. In 2016, we were asked by Nexus, the public body that run Metro, to develop and run a public consultation on passenger needs for replacement trains (a work program called Metro Futures). We devised an approach using principles from design and HCI supported by digital technologies (Bowen et al., Citation2020). The 2016 consultation led to Nexus securing UK Government funding to appoint Swiss manufacturer Stadler to build replacement trains to a specification that incorporated our consultation findings. In 2020, Nexus asked us to coordinate a second regional public consultation on whether Stadler’s proposed train design fitted diverse passenger needs and to obtain public preferences for several remaining design options.

This consultation used a digital mock-up of the proposed train – a high resolution 3 D visualization built by Stadler using Unreal Engine.Footnote1 Nexus planned to use a physical partial mock-up of a train compartment to evaluate accessibility later in the project. We had planned for the 2020 consultation activities to combine in-person and online activities, however, the imposition of COVID-19 measures required all activities to be moved online. Because of this, Metro Futures 2020 provided an opportunity to develop our 2016 work through increased use of interactive visual assets, and in developing entirely online activities.

Our ambition was to develop digital media and tools for Metro Futures 2020 that enabled participants to explore current practices and future possibilities in detail. This was in contrast to the frequent use of digital technologies that aim to expedite participation – allowing more people to engage rather than encouraging deeper engagement. Marres (Citation2015) observes that the design of technology affects how people engage with it, which can encourage reactionary comments rather than more considered engagements (Wilson & Tewdwr-Jones, Citation2022). Metro Futures 2020 provided us with the context to explore the research question: how can entirely online public consultations be configured, via activities and digital interventions, to enable deeper participation at scale? In characterizing the “deeper participation” intended, we drew upon aspects from our 2016 work that proved effective in delivering democratic and pragmatic value: i. engagement through current and potential future experiences of the new trains (henceforth experience-centeredness); ii. the creative envisioning and exploration of design proposals and their implications (henceforth imaginative exploration); and iii. opportunities for those passengers greatly affected by design proposals to positively influence them (henceforth giving voice).

Our Metro Futures 2020 consultation took place through activities on a bespoke website, social media polls, webinars and online workshops, which we designed and delivered for Nexus using assets from Stadler’s digital mock-up of new trains. In addition to providing useful findings for Nexus, our subsequent evaluation showed that participation on the website had the in-depth and exploratory character more typical of workshops than online consultations. Our article, therefore, largely considers the website and provides three contributions. First, in Materials and Methods, we provide an account of our online consultation approach (and its constituent digital media and tools) that enabled interconnected activities at varying depths and scales of participation. Second, in Results, we evaluate the effectiveness of Metro Futures in enabling deeper participation at scale. Finally, in the Discussion, we discuss the value of enabling a space for participation at varying depths and scales where participants engage with design proposals in terms of experience and via creative exploration, and the resulting transferable considerations for configuring public participation in large scale projects through digital technology. We begin with a review of participation in public transport consultations and via digital technology, and background information on Tyne and Wear Metro.

2. Background

2.1. Participation in public transport consultations

There are well-documented and understood benefits to involving people in making decisions that affect their everyday lives in cities (Cascetta & Pagliara, Citation2013; Gordon et al., Citation2011; Steinfeld et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, there are an increasing number of urban planning initiatives led by citizens as “co-creators in a collaborative approach to citymaking” (Foth, Citation2017, p. 28). For example, Carvajal Bermúdez and König (Citation2021) describe such citizen-led initiatives in Vienna that aim to transform residential streets from “spaces into places.” Their study of the role of technology within such initiatives highlights that involving citizen organizations in the co-creation of web-based tools for engagement and participation increased their adoption and use. Increased citizen agency is also becoming evident in public transport service improvement. May and Ross’ (Citation2018) study of a mobile app for reporting issues with public transport demonstrates that simple, usable web platforms are an effective means of enabling wider public participation. However, for the design of public transport systems (e.g., trains and their supporting infrastructure), examples of more in-depth public participation are rare.

It is often the case that the design of public transport systems in the UK lean on regulatory requirements of varied prescriptiveness, from high-level principles (such as requiring that transport is accessible to allFootnote2) to specifics (the height of a carriage above a station platformFootnote3). Because of this, there is “little attention to capturing and valuing place-based issues and experiences” (Vigar, Citation2017, p. 40) and acknowledging them within design processes. There is some literature on public participation in strategic infrastructure development, such as consultation on route expansion (Cascetta & Pagliara, Citation2013), transport investment (De Luca, Citation2014; Pagliara & Di Ruocco, Citation2018) or specific accessibility features decoupled from the train (Fujiyama et al., Citation2015). However, when it comes to the design of transport systems, we identified more research on human factors considerations of designing a driver’s cab (e.g., Wilson & Norris, Citation2005) than on the interior design for passengers.

Nevertheless, there are insights from public consultations for public transport planning that could be transferred to the specific context of public transport system design. For example, Sagaris’ (Citation2018) studies of two initiatives in Chile highlight a need to ensure social buy-in (in addition to addressing economic and environmental concerns) for planning sustainable public transport that “generate[s] the political support and the behavioural changes necessary for their success,” and that participation should lead to “genuine transformation of the final product” if it is to be supported by citizens.

There is therefore an opportunity to give citizens a stronger role in public consultation on the design of public transport systems specifically, particularly when improving on minimum requirements (Fujiyama et al., Citation2015), to understand how transport systems can be made more usable, accessible, and enjoyable. Investigations of the role of citizen participation in transport planning sit at the intersections of urban planning, transport, mobility, and – increasingly – HCI. For example, Yoo et al.’s (Citation2013) field study identified opportunities for bus passengers to co-design new service offerings via social computing systems that encourage participants to share rationales and explore consequences of current and proposed services, and to empathize with their impacts.

2.2. Participation through digital technology

Digital technology is increasingly used to enable deeper and more democratic public engagement in the planning and transformation of urban environments. Discussions of civic technology (e.g., May & Ross, Citation2018), urban HCI (e.g., Fredericks et al., Citation2016; Koeman et al., Citation2015), and urban interaction design (Foth, Citation2017) draws attention to the social and experiential aspects of urban places, and the importance of diverse and representative democratic participation in their development and use. Urban HCI and urban interaction design are largely concerned with technology (input devices, sensors, and displays and other presentation mechanisms) that is physically situated in the environment to which it relates. Nevertheless, these approaches offer insights for the design of public engagements accessed entirely online.

From studies of urban technology deployments in Australia, Fredericks et al. (Citation2016) propose the “middle-out design” of situated urban HCI interventions to include both the top-down agenda of civic institutions and the bottom-up collective knowledge of public stakeholders to support more democratic and effective community engagements to inform change.

Rather than technology deployments within a single location, Koeman et al. (Citation2015) designed and deployed technology over an extended area to investigate how it could support community-wide engagement. Their tangible voting devices and pavement (sidewalk) displays distributed between shops along a city street engaged residents across socio-economic and political differences through prompting: curiosity about the engagement, reflection on its topics; conversations between residents; comparison between sites along the street; and, competition between sites on the quantity of public interaction. Koeman et al. (Citation2015) also highlight that involving local stakeholders in generating questions and statements for their public engagement made them more “accessible and relatable to the community” and conclude that the distribution of technology across multiple places with existing social functions offers a way to proceed where there is no single place that unites a geographic community. Finally, May and Ross (Citation2018) highlight the importance of eliciting passengers’ emotions in relation to a service issue – rather than a description of the “problem” alone – to access passengers’ experiences of public transport services.

In urban planning, immersive media and virtual environments have been used to address some of the limitations of traditional consultation methods. Smart phones increasingly being used to encourage people to participate “in place” during their everyday experiences. Beginning in the mid-noughties, governments have rolled out digital tools for people to engage with formal processes (Irani et al., Citation2005). Mass-deployable digital technologies open up new opportunities for engaging people – allowing people to participate from anywhere and at any time.

However, recent work has begun to critique technologies that facilitate place-less engagement, with a move towards those that are more situated, immersed or “placed” within their environments that can serve to broaden engagement (Koeman et al., Citation2015). Fischer and Hornecker (Citation2012, p. 9) argue that engagement should take “situated architectural effects (instead of the anytime, anywhere paradigm) into account… [and focus on]… how to integrate technology into urban everyday life and architectural space.” Howard and Gaborit (Citation2007) note how a lack of interactivity and immersion in how proposals are presented produces comments without the necessary references to specific details. These issues, they argue, are compounded and lead to “non exploitable results for planners and can explain the lack of interest in urban planning from the public” (Howard & Gaborit, Citation2007, p. 233).

To resolve some of these difficulties, Gordon et al. (Citation2011, p. 507) propose that successful public consultations should borrow from “media practices that have proven to be engaging in other realms” notably challenge-based, sensory, and imaginative forms of immersion from videogames. For example, Du et al. (Citation2020) combined an immersive display and smart phone app to enable participants to envisage and explore proposals and include rationales and specific contexts for their comments that made them more useful to decision-makers. Similarly, HCI research has investigated the value of gamifying urban planning. O’Donnell (Citation2018) devised a game that allowed city residents to address concerns over transport and density by adjusting housing types, detailing the increased engagement and reflection that resulted. Thiel (Citation2016) found that gamification of participation processes can impact the quantity and quality of input, being useful for onboarding but having reduced value subsequently.

Immersive visual projections and sound are also increasingly being used to prototype and evaluate “context-based interfaces” (Flohr et al., Citation2020; Hoggenmueller et al., Citation2021) for autonomous vehicles. Flohr et al. (Citation2020) demonstrate the value of room-scale immersive video and sound in providing a sense of presence and realism. Building on this work Hoggenmueller et al. (Citation2021) compared user interactions with prototypes using 360-degree real world video or computer-generated images on virtual reality (VR) head-mounted displays or a PC monitor. Their comparative study demonstrated greater presence using VR, and highlights the usefulness of VR prototypes for holistic and contextual assessment as they are “better suited when seeking user feedback on […] how the interface influences the user’s experiential and perceptual aspects within a particular context.”

A particular concern is that some groups, such as disabled people, are often marginalized in urban planning and consultation (Imrie, Citation2000; Imrie & Kumar, Citation1998). HCI’s “civic turn” has sought to address some of the limits of traditional consultation methods that give rise to exclusion, with a focus on co-designing technologies to amplify marginalized voices. In this context, there has been a focus on the use of technology to share these groups’ experiences of problems and potential solutions (Steinfeld et al., Citation2010), as well as to support the capture of data that might be used in support of advocacy and campaigning with transport providers and civic authorities (Rodger et al., Citation2019, Citation2016).

Despite the transformative potential of digital technologies, it is important to recognize they are not a panacea. Technologies present challenges around access and digital literacy and can serve to entrench existing divisions (Office for National Statistics, Citation2019). Moreover, technologies are not neutral, but actively shape participation (Marres, Citation2015). For example, map-based discussions support lightweight commenting and can encourage reporting problems rather than more substantial discussion (Gordon et al., Citation2011). In trying to stimulate more reflective discussions, Rodger et al. (Citation2019) encouraged participants to discuss and interpret recordings made through a wheelchair mounted smart phone and app, with a view to exploring how the issues raised might be resolved. Participatory approaches such as Action Research (Hayes, Citation2011) highlight the value of shared interpretation and discussion of data, however this often jars with the deployment of digital technologies for engagement at scale, where automated dashboards, interpreted results and clear, quantitative outputs are preferred to inform decision making.

2.3. Summary of related work

In Metro Futures 2020, our ambition was to develop online media and tools for exploration and dialogue around potential future designs of a transport system through which understanding (rather than merely preferences), feelings and experiences could be shared. The research described above, whilst not sharing the specific context (public consultation on the design of trains, online), does outline considerations for public consultations that resonate with our characterization of deeper participation (experience centeredness, imaginative exploration, giving voice) and subsequent public engagement approach. Namely: to involve public stakeholders (passengers) as well as Nexus in setting the agenda for the consultation and in devising online resources (Carvajal Bermúdez & König, Citation2021; Fredericks et al., Citation2016; Koeman et al., Citation2015); to distribute opportunities for public engagement to online places with existing social functions (Koeman et al., Citation2015); to encourage contextualized consideration of design features – online – using strategies such as immersion and gamification (Gordon et al., Citation2011; Howard & Gaborit, Citation2007; O’Donnell, Citation2018; Thiel, Citation2016), and 360-degree images (Hoggenmueller et al., Citation2021); to capture contextualized place-based experiences and emotions rather than “problems” alone (Vigar, Citation2017; May & Ross, Citation2018); to encourage participants to explain their contributions, and to explore the implications of design changes and empathize with their impacts (Yoo et al., Citation2013); to ensure that typically marginalized voices are amplified, such as by capturing data to support advocacy and campaigning (Rodger et al., Citation2016, Citation2019); and, to ensure that public participation genuinely affects the final design (Sagaris, Citation2018).

2.4. Tyne and Wear Metro and Metro Futures

The Tyne and Wear Metro, which opened in 1980, is “the UK’s busiest light rail system outside London” (Nexus, Citation2021). Ground-breaking at the time, Metro included several novel accessibility considerations, such as system-wide step free access. In 2016, the original trains presented reliability concerns (Powell et al., Citation2016) prompting Nexus to approach the UK Government to fund a new train fleet. The first Metro Futures public consultation supported this application that led to the award of £362 m. Following a competitive tender, Stadler was appointed to develop a train design that addressed passenger preferences and needs from the 2016 consultation.

Stadler’s design, announced early 2020, proposed significant changes from the current train fleet. These included: sideways seating (rather than pairs of forward or backward-facing seats); five connected carriages (rather than two-carriage trains operating in pairs); sliding steps bridging the horizonal gap between train and platform; and air conditioning. However, several internal design options needing resolving (e.g., seating color and pattern). Nexus therefore commissioned the Metro Futures 2020 public consultation to understand public preferences for these design options and whether Stadler’s proposed train design fitted diverse passenger needs, with the intention that these be accommodated in the final train design.

In appointing us to coordinate the Metro Futures 2020 online consultation, Nexus documented the train features to be considered (see ) and the requirements for the consultation. These requirements included: engaging numerous people such that a diverse range of passengers was sufficiently represented (including disabled people, older people, families, those travelling with pushchairs (strollers), luggage or bicycles, and people travelling for work, shopping, leisure, and tourism); and enabling participants to consider the proposed trains in more “realistic” conditions through making the consultation immersive.

Table 1. Data gathered on design options and train features across different parts of the consultation. Shading indicates data collected for an option or feature (row) within specific parts of the consultation (column).

3. Materials and methods

This section describes the digital media and tools we used in the 2020 Metro Futures online public consultation and the rationale behind our approach.

3.1. Approach rationale: Deep-narrow and shallow-wide

Nexus valued our 2016 work and requested that the 2020 consultation followed a similar approach so that findings would be comparable to and build upon it. Developing our public engagement approach provided us with an opportunity to use effective aspects of our 2016 work (experience-centeredness, imaginative exploration, giving voice – as described earlier) as a basis for further research into how entirely online activities and digital technology could support deeper participation at scale.

Our 2016 consultation (Bowen et al., Citation2020) had two interacting strands with differing depth and scale: longer and more reflective (“deep”) discussions in design workshops with a (“narrow”) group of ∼20 public participants, and briefer and more reactive (“shallow”) engagements at informal drop-in sessions and on a website from ∼3000 people (“wide”). Sharing insights and ideas developed in workshops to elicit further responses on the website and at drop-in sessions and online proved an effective strategy for combining deeper workshop discussions and wider regional participation in the consultation. We therefore sought to translate this combination of deep-narrow and shallow-wide participation into the 2020 consultation.

Locating 2016 drop-in sessions in busy public locations (including shopping centres, a travel interchange, and a local market) increased participation, which was consequently more serendipitous and less intentional than workshops (where participants had undertaken an application and selection process). We therefore also considered how to enable such serendipitous participation online.

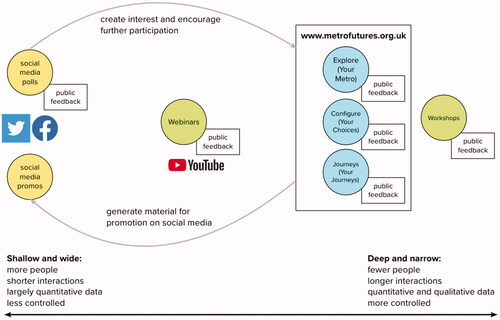

Our resulting approach consisted of several activities across a shallow-wide to deep-narrow spectrum, as illustrated in and plotted across the project duration in . Our research group designed and delivered these activities, and their supporting online resources, using assets from Stadler’s digital mock-up of new trains. To enable more serendipitous participation, we used social media – where Metro has ∼130 K followers on Twitter and ∼50 K followers on Facebook. Our intention was to undertake shallower consultation on social media to create interest and encourage further participation on our website. The website would allow for more immersive, imaginative, and experience-centered activities to provide a deeper level of engagement, and – through enabling website outputs to be shared on social media – raise awareness of the consultation. Three webinars were live streamed to raise awareness and gather additional public feedback. And lastly, a series of twelve online workshops were run, open to all but limited to 30 participants per workshop.

Figure 1. Diagrammatic representation of Metro Futures 2020 consultation approach. Circle colors indicate the media and technology we designed: yellow – creating media for existing platforms; green – facilitating and creating media for events on existing platforms; and, blue – designing activities on the platform (website) we developed.

3.2. Agreeing the agenda for the online consultation

Agreeing the agenda for the online consultation was a process of combining train features of interest to Nexus, design changes that Stadler could accommodate, and public concerns both expressed in the 2016 consultation and evident in 2020. In the early stages of the project, we discussed with Nexus and Stadler which of Nexus’ list of train features could be presented to participants as a series of design options (e.g., different shapes for grab poles). This agreement depended on whether changes to specific train features could be accommodated within the manufacturing schedule and whether corresponding design options could be communicated through Stadler’s digital mock-up. From these discussions seven design options were agreed. It was also agreed that general feedback would also be sought on train features with no corresponding design options. lists these design options and train features, the types of public response elicited (vote for a preferred option, rating of a feature, and/or text comments), and which parts of the consultation elicited responses per option or feature (website section, webinar, social media).

In devising the 2020 consultation activities, we considered how the new trains could be envisaged according to passenger experiences (experience centeredness) in addition to focusing directly on specific features, for example enabling participants to consider how well new trains would perform during busy periods (a concern identified in the 2016 consultation). In doing so, we were able to represent 2016 participants’ experiences and sought to extend this through additional discussions with groups representing relevant passenger experiences (giving voice). We therefore spoke with representatives of the Elders Council (advocating for older people), the Campaign for Level Boarding (many of whom are disabled, and wheelchair or mobility scooter users), regional Youth Councils (younger people advocating for younger people), and Newcastle Cycling Campaign. Through these conversations, we identified further experiences that might be encountered on the new trains to include in consultation activities. For example, the new trains include bicycle storage areas that are not present in current trains and cycling campaigners highlighted the experiences of families travelling with multiple bicycles.

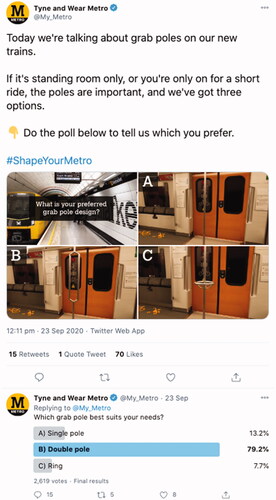

3.3. Social media polls

Engaging people on social media served to both go where people already congregate online and involve them using technology they are familiar with. To do this, polls were conducted on Twitter on each of the seven design options (see ). As we shall describe, more sophisticated ways for participants to envisage combinations of design options were available on the website. Nevertheless, the social media polls engaged a large proportion of participants and encouraged further contributions via the website.

3.4. Metro Futures website

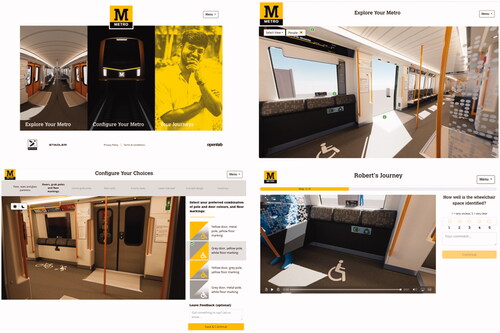

The Metro Futures websiteFootnote4 had three sections designed to contextualize website participants’ consideration of the new trains in different ways, as described below (see ).

Figure 3. The Metro Futures website: homepage, Explore section, Configure section, Journeys section.

3.4.1. Explore Your Metro

The Explore Your Metro section (henceforth Explore) enabled website participants to envisage and provide feedback on train features in-situ within the train (experience-centeredness, imaginative exploration). This section presented 360-degree images of seven locations inside and alongside the trains.Footnote5 Hotspots were placed over relevant train features that revealed a note of the train feature and a request for feedback – either as a Likert rating or text comment.

The Explore section was designed to provide greater context for feedback through providing a visualization of the new train and enabling participants to consider train features alongside the whole train and other train features. Additional realism was provided by allowing participants to switch on and off visual representations of people, wheelchairs, bicycles, pushchairs, and luggage.

3.4.2. Configure Your Metro

The Configure Your Metro section (henceforth Configure) was designed to provide greater context by enabling participants to visualize and experiment with combinations of design options and consider their interrelationship, and thereby create their own interior design (imaginative exploration). Participants moved through a sequence of seven visualizations of each design option, selecting a preferred choice at each stage, with subsequent visualizations showing preceding choices. Once choices for all seven options were made, participants were shown images of their “interior design” and invited to download their design and share it on Twitter or Facebook. Throughout this section, participants could step forwards and backwards through design options to change choices and experiment with combinations. Greater context was provided by enabling participants to visualize choices in daylight and night-time lighting conditions (particularly important when considering color and contrast, and visual accessibility).

Participants’ choices for each design option were captured. However, as participants could go back and change choices for design options, website data was filtered such that only website respondents’ final choices were reported to Nexus on the assumption that these represented participants’ preferred choices.

3.4.3. Your Journeys

A key objective was to highlight the specific needs and experiences of different people that we sought to include in consideration of the new trains (giving voice). The Your Journeys section (henceforth Journeys) therefore encouraged participants to consider how well the new trains fit the needs of others with specific needs: parents/carers with children and pushchairs; younger people; older people; passengers travelling with bicycles; wheelchair users; and, visually impaired people.

Participants were able to follow journeys for six personas representing different passenger experiences and needs that were derived from the 2016 findings and the conversations with relevant groups early in the project. While the personas and journey scenarios were fictional, they were based on real-world experiences shared with us. Rather than focus solely on positive aspects, they presented challenging situations to encourage participants to problematize train features and the extent to which they helped or hindered the persona. These included, for example, antisocial behavior, children wandering close to train doors, or priority seats occupied by passengers without an access need.

For each persona, participants were presented with a short biography followed by their journey illustrated via a series of short video clips that combined photographs, rendered images and animations from Stadler’s digital mock-up, sound effects, and a first-person narration. To illustrate to sighted participants the impact of visual impairments on train features, the video clips for the “Desmond” persona journey were modified to simulate diabetic retinopathy following examples given in online sight loss simulators.Footnote6

After each video clip, participants were asked questions relevant to the unfolding journey from the persona’s point of view, with responses in the form of Likert ratings on train features, design option preferences, and text comments. For example, “Sanjeev” is travelling with his bicycle and several bags, and participants were asked to choose a bicycle fixing option from this perspective. Persona biographies and narration also included details to encourage participants to consider the experience of using the trains. For example, in this case, after a busy day at work and with a long journey ahead. Each journey ended with two further questions about how well the new trains suit the needs of someone like the persona with a Likert scale response, and a prompt to explain what works well and what works less well.

The Journeys section was designed to provide greater context by drawing participants’ attention to others’ more particular journey experiences and encourage empathy with how personal design decisions impact other people’s experiences and needs (experience-centeredness). Attending to diverse passenger needs in this manner could help ensure new trains met relevant accessibility regulations, but also could produce a more usable train for all.

3.4.4. Webinars

The three webinars, broadcast as livestreams (on YouTubeFootnote7 and on Metro’s Facebook page for the final webinar) had a dual purpose in both promoting the consultation and enabling webinar audiences to be involved. Webinars began with a “fly-through” animation of the train rendered from Stadler’s digital mock-up followed by a live segment with one of the project team and a senior Nexus representative. The webinar audience were then asked to vote on design options, demonstrated through the Unreal Engine digital mock-up operated by another member of the project team. Using the digital mock-up rather than the Metro Futures website allowed us to move around and inspect different train features live, in response to discussions, questions and comments in the webinar.

The SlidoFootnote8 tool was used to poll audience participants’ preferences for the design options, and to collate questions from the audience for the Nexus representative. Whilst Slido was effective at determining popular questions, the presenter (and colleagues “backstage”) also took care to ask other questions that, whilst not necessarily as popular, represented relevant or minority topics that had not previously been covered (giving voice).

3.4.5. Workshops

Online workshops had the fewest participants but greatest depth of discussions. The broad themes for these workshops were derived from our 2016 consultation findings and concerned the Shared Spaces of trains (for wheelchairs, pushchairs, luggage, etc.), travelling on trains in Busy Times, how trains affected Personal Safety and Wellbeing, and the Physical Safety and Accessibility of trains. Eight one-hour workshops (using Zoom) were conducted, two for each theme, over two weeks. Individuals, disability groups, and special interest groups were invited to all workshops rather than specific workshops with the intention of representing and engaging multiple perspectives within each forum to afford constructive dialogue between perspectives (giving voice).

This approach worked well to a degree with older people, visually impaired people, and public transport advocates (amongst others) being represented in workshops. However, it became clear that other groups would benefit from targeted workshops. Consequently, four additional workshops were arranged with wheelchair users, youth councils, and D/deafFootnote9 people (bringing the total number of workshops to 12).

Workshop facilitators used the Explore and Configure website sections to conduct a virtual tour of the train with workshop participants via screen sharing, stopping at points to prompt in-depth discussions of train features relevant to the workshop theme. Workshop participants also proactively suggested other aspects of the train that they wished to explore and discuss. When visually impaired participants were present in workshops the facilitator would provide verbal descriptions of the train. The workshop, co-hosted with Deaf Awareness, for hearing impaired people included a live text to speech interpreter to provide captions throughout. The workshop for Deaf people, co-hosted with Becoming Visible, was conducted in British Sign Language (BSL) via a BSL facilitator and a BSL interpreter.

4. Results – An evaluation of Metro Futures 2020

The program of online activities devised for Metro Futures 2020 sought to enable deeper participation at scale, and enabled us to address the research question: how can entirely online public consultations be configured, via activities and digital interventions, to do so? Metro Futures 2020 provided an opportunity to evaluate the extent to which our approach enabled deeper public engagements at the larger scale of a UK region. Our evaluation of the depth, scale and consequent impact of Metro Futures 2020 is reported in this section. The findings of the public consultation on train features are not the focus of our evaluation here, and are instead available in a report for Nexus and on the consultation website.Footnote10

4.1. Evaluation data and analysis

To evaluate the depth and scale of public engagement in Metro Futures 2020 we used both quantitative and qualitative data sources. Quantitative data consisted of data analytics from Twitter, Facebook, Slido, and YouTube, and the data entered into the consultation website. Qualitative data consisted of comments on the consultation website and workshop transcripts. Both data sources were used in reporting consultation findings to Nexus: preferences for design options and ratings for train features were collated from the social media and Slido polls, and website responses, and participants’ comments relating to design options, train features, and other concerns with the new trains from an initial deductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) of workshop transcripts and website comments. These data were further analyzed to evaluate the effectiveness of our approach.

In addition to demonstrating the overall scale of the consultation, quantitative data was used to explore how visitor interactions on the website – within and between the three sections – evidenced the quantity of deeper engagement. These results are discussed in the section below titled Depth at Scale on the Website.

Our initial analysis of website comments, for the Nexus report, highlighted that they were more reflective and detailed than might be expected from a typical online consultation (workshop transcripts had a similar character to in-person workshops). Hence, a second round of thematic analysis focused on website comments alone to investigate how they evidenced the character of deeper engagement. A first inductive pass coded the character of comments (their manner, inferences of participant’s intentions, etc.), and a second deductive pass coded for evidence of our design approach in action. Authors 1 and 2 coded separately then cross-checked codes and developed themes, which were discussed and agreed with the entire research team. The results of this analysis are described below in three sections relating to the aspects of our design approach titled Considering Experiences of Trains, Exploring Design Details and their Implications, and Having the Ability to Influence Designs.

Informed consent was obtained for all website participants (and workshop participants). Participants information, including the use of anonymized comments, was provided through a modal on the website shown to first-time site visitors, with consent indicated and assumed through clicking a button to proceed. The research project was reviewed and granted ethical approval by the Faculty of Science, Agriculture and Engineering Ethics Committee, Newcastle University with project number 20-BOW-027.

4.2. Public participation

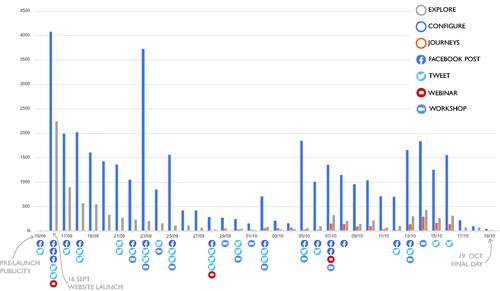

The Metro Futures consultation began at 10:00 on 16th September 2020 with a launch webinar and the website going live. There were promotional social media posts before the launch, but polls did not begin until after the launch and were spread across the consultation (see ). The consultation was announced as closing on 16th October (one month) but practically ended at 16:30 on 19th October 2020 when the website stopped accepting data entries and was switched to a holding page.

The Metro Futures 2020 consultation received over 23,000 public engagements across the website, social media, webinars, and workshops. Over half (14,100) of these engagements were on social media and therefore represented shallower engagements than website engagements (8298) and workshop attendances (53).

The term “engagement” characterizes and quantifies participants’ involvement. One engagement equates to one person responding to a poll on Twitter, participating in a Slido poll during one webinar, or attending a workshop. Hence, for these consultation strands, the number of engagements is not exactly equivalent to the number of people engaging. For example, participants could respond to multiple Twitter and Slido polls and thus create multiple engagements. Website visitors were a given unique identifier (session ID cookie), set when someone visited the website and responded to some basic demographic questions (age, local authority area, etc.), that was recorded with each data entry. 8.7% of participants answering demographic questions did not submit any other data. Whilst this created a greater equivalence between engagements and participants for the website, it was possible for participants to have multiple session IDs. Session ID cookies persisted in visitors’ browsers for typically 6–12 h (differing by web browser), hence if a participant returned to the website outside this period they would receive a new session ID.

We quantify the scale of participation in terms of engagements for two reasons. Firstly, due to the practical difficulties of identifying unique participants as described above. Whilst advanced features of Google Analytics would have enabled us to better ascertain participant numbers on the website, discrepancies remain if participants access via different devices. We also used a privacy-focused implementation of Google Analytics, which collected minimal personal details and so made tracking unique visitors difficult. And secondly, it characterizes participation in terms of actual contributions to the consultation: through data entry, rather than page or post views alone.

4.3. Depth at scale on the website

The data shows that the “shallower” engagements (social media polls) were more numerous (14,100 engagements, 60.6%) than “deeper” engagements (workshops and webinars – 877 engagements, 3.7%). It is less evident whether shallower, larger scale activities encouraged the deeper, smaller scale activities. shows little correlation between engagements and the timing of social media posts, webinars and workshops. There were spikes of increased website activity on the website after the launch webinar on 16th September, and several social media posts on 23rd September. However, two further webinars and similar numbers of social media posts on 28th September and 7th October did not lead to notable increases in website activity.

Our quantitative analysis shows some correlation between depth and scale – shallower participation on social media was wider and deeper participation in workshops was narrower. However, there was notable depth in the somewhat wider 8928 engagements (35.7%) on the website. Further quantitative analysis demonstrates this depth in terms of the quantity of data entered, the duration of engagements, the completion of multi-stage tasks, and the frequency of commenting.

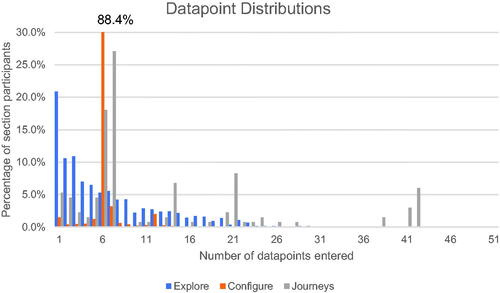

4.4. More data entered

The depth of website engagements compared to social media engagements is illustrated by the larger amounts of consultation data contributed per engagement. Participation in a social media poll equates to one or two datapoints per engagement (vote, plus optional comment) whereas a website visit can include multiple datapoints per engagement (votes, ratings, comments across sections). Our analysis shows higher average datapoint contributions by unique session IDs on the website – Explore (6.65 mean, 5 median datapoints), Configure (6.16 mean, 6 median datapoints), Journeys (12.65 mean, 7 median datapoints). plots the distribution of datapoints entered and shows that most participants contributed 10 or fewer datapoints but that there was a “long tail” effect for the Explore section and a significant number of participants who contributed 20 or more datapoints in the Journeys section. The 88.4% of session IDs contributing 6 datapoints in Configure corresponds to the minimum number of datapoints to complete this section. Similarly, spikes in the Journeys data at multiples of 7 corresponds to the 7 datapoints per persona scenario in this section.

4.5. Longer engagement durations

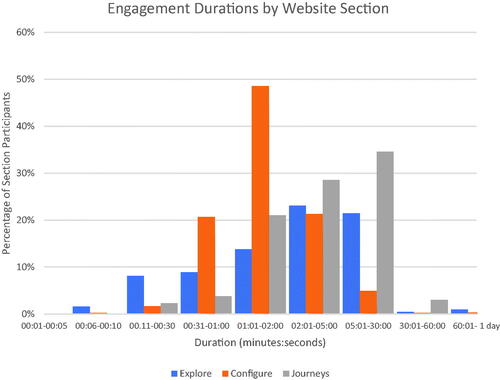

The duration of website engagements also shows deeper engagement, to varying degrees.

plots the duration of engagements within each section according to the difference between earliest and latest datapoint entry per session ID. Durations of less than one second and greater than one day were excluded as not likely to represent genuine participant engagements. Our analysis shows that engagements tended to be shorter in Configure (71.1% 2 minutes or shorter) and longer in Journeys and Explore (72.9% and 66.8% longer than 2 minutes).

4.6. Completing multi-stage tasks

Website engagements were also deeper in terms of the quantity of activities completed within each engagement compared to the single vote and/or comment within each social media engagement. summarizes participants’ behavior on the website quantified according to unique session IDs with one or more data points (ratings, votes, comments). Two website sections both had definite end points for data entry – all design options selected in Configure or all questions within a scenario answered in Journeys. Our analysis shows that the majority of participants remained to complete these multi-stage tasks – 96.5% in Configure, 85.4% in Journeys. This data also shows that Configure was the most engaged with section in terms of data entry (81%) followed by Explore (17.3%) and Journeys (1.7%). The Journeys section was launched on 28th September, part-way part way through the consultation, which partly explains its lower engagement percentage.

Table 2. Engagements within each website section.

We also determined how many participants engaged in more than one section of the site, using engagements since 28th September (once all three sections were live). Again, Configure was the most engaged with section in terms of participant numbers, with 81.3% of participants visiting this section alone. However, it is notable that 12.6% of participants visited two or three sections of the website.

4.7. Frequent commenting

Lastly, the high proportion of participants leaving comments in addition to votes and ratings in each website section also suggests deeper engagement. This behavior was notable in Journeys, where 93.8% participants commented, compared to lower proportions of participants commenting in Explore (49.4%) and Configure (15.5%) – see .

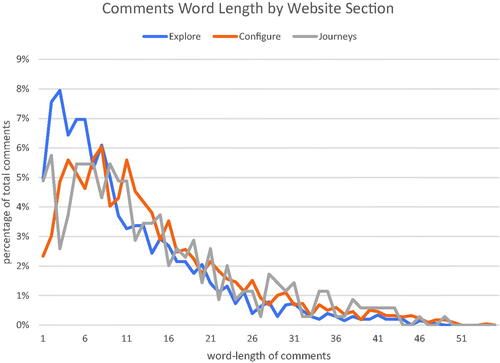

To further understand commenting behavior, we determined the number of datapoints entered for each website section and the proportion of these datapoints that included comments as well as votes or ratings. We also broke down comments within each section according to their word-length (see ). As there were substantially greater engagements overall in the Configure section, all data were normalized as the percentages of total comments within a section. From this analysis, it is clear a higher proportion of data points included comments in the Explore (28.1%) and Journeys (25.1%) sections than in Configure (5.8%), although the word-length of comments follows a similar pattern within each section with the majority of comments being shorter.

The quantitative data shows different patterns of engagement across the three website sections. From this data alone, Configure had the least depth and greatest scale, and Journeys had the greatest depth and least scale. However, our qualitative analysis of the website comments showed depth in participants’ engagements across all sections. We now turn to how this depth can be characterized.

4.8. Considering experiences of trains

Our analysis of website comments demonstrates participants engaged deeper with the proposed train designs through considering current and potential future experiences of trains.

4.8.1. Relating to own and others’ experiences

Participants commented in relation to their own experiences (24 references coded) using phrases such as “in my experience” and “I find [that]” and referring to specific memories in commenting on train features, for example “when I was a small child my foot went down the gap and I really hurt my leg so I support this [sliding step] wholeheartedly.” Participants also alluded to personal experiences by characterizing themselves, for example a participant described themself “as a regular cyclist and train traveller” to comment upon the appropriateness of a certain bicycle fixing design option.

Participants also considered proposed designs in relation to others’ experiences (36 references coded) both the experiences of generalized groups of people (e.g.,“[bicycle fixing] leaves more space for the buggy users”) and of people known to them (e.g.,“my disabled, wheelchair using son… finds it difficult and scary when getting on and off the metro because of the gap”). This consideration of others extended to the Journeys section where participants considered train features in relation to the experiences personas might have. This was notable for visually-impaired “Desmond” (4 references coded) and the young mother “Jessica” (6 references coded). For example, considering the experiences of travelling with children “I think this [double pole] might help if she [Jessica] could put arm through the gap and hold the pushchair when her hand is on the other side.”

4.8.2. Impacts on disabled people

A significant proportion of the experience-related comments demonstrated that participants engaged with the proposed train designs in terms of potential impacts on disabled people. This included personal impacts (e.g., “My disability is unseen and [I] will struggle to get a seat when it’s quiet, this arrangement will prevent me using the metro when it’s even modestly busy”), impacts on personas (e.g., “the pole needs to stand out more than the door so [‘Desmond’] don't walk into it”), and impacts on wheelchair users (e.g., “button might be wrong position for someone in wheelchair”), hearing-impaired people (e.g., “alarms are very high frequency – people with hearing loss may find them hard to distinguish”) and visually-impaired people (e.g., “for those with visual impairment it would be better to have a yellow flooring with black icons for the wheelchair spaces etc.”).

4.9. Exploring design details and their implications

Another illustration of deeper engagement was that participants creatively and imaginatively explored both the proposed train’s design details and their implications via the interactive visualizations on the website. Configure provided the greatest potential to experiment with design options. Explore and Journeys also encouraged participants to envisage new trains – in 360-degrees, and via personas and scenarios – as a basis for eliciting feedback. Our analysis shows how, to varying degrees, the website enabled participants to envisage and explore future scenarios – using the images, sounds and stories presented – and consider the broader implications of design details.

4.9.1. Limited experimentation in configure

In Configure, participants could minimally complete the section by entering preferences for each of the six design options, or choose to move backwards and change preferences and/or repeat the whole section. As discussed earlier and shown in , our quantitative analysis showed that 92.1% of participants entered the fewest data points needed for completion. Whilst this demonstrates that few participants moved back and forth to creatively experiment, the website data cannot show whether participants experimented within design options at each stage as it only recorded their final choice for each of the six stages. However, the Configure section’s popularity, as the most engaged with part of the website, does demonstrate that visualizing design option combinations did encourage numerous people to participate.

4.9.2. Exploring the future

In addition to exploring the future Metro through envisaging scenarios reflecting their own and others’ experiences, our analysis shows that participants also envisaged new scenarios and their consequences via the website. For example, the 360-degree visualizations in Explore enabled participants to imagine themselves inside the train and highlight issues such as the visibility of information screens being “unsuitable for those in the wheelchair space,” and other participants noting “the information board would be behind them” and that screens were “too high for wheelchair users especially neck conditions.”

Participants envisaged how current situations would play out in new trains in considering train features such as exploring how the proposed designs would cope during busy periods. For example, whether floor and door markings would be visible and the suitability of various central pole options, where one person commented “this would be great on a [Football/soccer] match day when it’s busy as I have been in the situation where hands are on top of each other.” Participants also explored how design details might encourage or discourage anti-social behavior (ASB). This included the train’s more open layout where one person suggested “charvas [insulting term] will ruin it for the whole train and not just one carriage” and another reflected that “CCTV is comforting. Single corridor train less so. Should an ASB incident happen it will be difficult to get away on the single corridor.”

Participants were able to project their experiences of the Metro onto the proposed design, and explore the extent the design addressed previous difficulties, such as reflecting on how people might cope with getting off the new trains with bikes and buggies or when using a wheelchair, or locating the wheelchair spaces on a busy or noisy Metro.

Lastly, participants suggested design changes that would resolve the issues they had raised (e.g., “Could there be an additional button lower down for lone disabled users at these designated disabled doors?”) and satisfy unmet needs (e.g., “would be great if you were able fit an additional seat in here for carers/people traveling with a person in a wheelchair [who] may need someone near them to help them”).

4.9.3. Thinking through implications

Participants also went beyond envisaging future experiences to consider the broader implications of design details. For example, participants regularly discussed the ease of maintaining a new feature, asking “how long will it last?” with some being seen to have “a greater chance to be broken” or “to be broken and therefore cost for replacement.” Others asked rhetorical questions about whether features would “deal with high levels of use for decades on end? Maybe” and thus reduce the overall reliability of the train, noting if a feature “seems like a potential source of issues and unreliability” that has the chance of “failing and putting the carriage out of service.” Others noted features led to a “higher chance of faults and breakdowns. Leading to trains been removed from service.”

Comments frequently considered vandalism, graffiti, and the cleaning of trains as implications. Concerns were raised about muddy feet that “will make the metro look dirty” or whether an image should be used over a blank wall (e.g., “All over design or picture – it will get scuffed or vandalised graffiti if left clear”).

The center grab pole provoked discussion about misuse and how certain design options might stop “kids climbing on it,” “swinging and spinning round it” or “some idiot trying to put there [sic] head through there.” Others gave their preferences based upon whether certain options could cause injury, noting that an option “could cause potential accidents” and that “Children will bump their heads,” and with certain options “you are less likely to bump into it than the others which protrude significantly.” Others imagined the risk to children, noting “There are so many doors, there is a higher risk of the toddler running away.”

A frequently raised implication of the proposed design was that more passengers would be standing because of fewer seats. This was frequently commented upon despite not being part of the consultation, as we describe later. Some participants linked this to the UK’s ageing population asking “should seating not be a priority?” and another noting “seats would be much more useful, … for the young or elderly” and that “it can be dangerous if someone who is unsteady on their feet to have to stand on moving train.” Predicting the increased number of standing passengers, participants turned their attention to the provision of grab poles, asking “how are people meant to keep balanced and stable standing in the middle when there’s nothing there to hold on to??.”

Participants interpreted the implications of the proposed train design and, significantly, not just the design choices that they were offered but on the entire design. Comments demonstrate a deeper engagement with the implications of the design, and some of the difficulties participants thought the design might introduce.

4.10. Having the ability to influence designs

Our approach was intended to ensure that consultation participants could positively influence the final train design via their contributions, in addition to voting on design options and ratings of train features. This was particularly the case for those most likely to be affected by design details, including disabled people. Workshop discussions provided many of these contributions, and workshops had high proportions of visually impaired people, wheelchair and mobility scooter users, D/deaf people, cyclists, younger people, and older people attending. However, broader consideration of the needs of these diverse groups (as people most likely to be affected by train features) was also evident in website comments. Whilst it was not always clear whether a participant was commenting from personal experience, numerous comments considered the experiences of and impacts on disabled people, carers, those travelling with young children, and cyclists. The Journeys section was particularly effective in eliciting such responses.

We should note that the diversity of website participants was low, with participants 58.1% 17–34 years old, 64% male, 92.6% white, and 90% not declaring themselves as having a disability (age and local authority were the only compulsory demographic questions). This would be more problematic had we only reported consensus views in our consultation report and not emphasized concerns expressed by those who might otherwise be marginalized, and had we not developed the website content (notably personas) with diverse groups of people to encourage others to consider more diverse passenger needs.

4.10.1. Making their voices heard

Tyne and Wear Metro evokes strong feelings, positive and negative, across the region. Website comments suggest that many participants tried hard to ensure their voices were heard.

The design options for bicycle fixings prompted some of the strongest responses with several participants questioning whether cycles should be allowed on Metro at all, for example, one person “would NEVER allow bikes in the first place!” whilst other participants were pleased that bikes will be allowed having previously been restricted. The center grab pole, priority seats, and lack of front seat view also prompted strong responses.

Participants expressed strong reactions to design options and train features in their comments through: exclamation marks and emotional language (e.g., “You can’t see out of the front anymore! [sad face],” “[double pole] gives me anxiety just looking at it”); strong language (e.g., It’s awkward as fuck when you touch someone else's hand so this is a must”); and, capitalization (e.g., “Bikes other than folding bikes should ONLY be allowed on trains FULL STOP”).

Participants also used the website to give their choices more weight through adding a comment justifying their choice, with some going as far as discussing other options (e.g., “White looks amazing, but it will quickly turn dirty and discolour with shoes scuffing it […] so dark grey would work instead”), or reflecting on their personal experiences to give weight to their choices (e.g., “After living in London and using the tube everyday, its easier to hold on vertically than horizontally, and the double pole works well to stop people having to reach really high up or low down”).

Finally, numerous participants expressed their feelings in short or single-word responses, the majority of which were positive (123 references coded, e.g., “amazing,” “beautiful,” “cool,” “fantastic,” “outstanding,” “love it”) although several were negative (29 references coded, e.g., “awful,” “couldn’t care less,” “shit”).

4.10.2. Expressing concerns beyond the scope of the consultation

In some instances, participants’ strength of feeling led them to use website comments to express concerns beyond the design details presented, including topics outside Nexus’ scope for the consultation. For example, one participant used a form in Configure to comment “Nowhere else to post this so, please DO NOT have seats that scrotes [insulting term] can put their feet up on,” another participant used a question on the clarity of information screens in Explore to comment “Unrelated Question: Does the main interior lights turn off or dimm to save energy when outside is very bright? i.e. sunny days? This could save energy and money. Maybe just a light sensor on the roof of the metro carriage?.” And, a participant discussed COVID-19 and ventilation when commenting on seating styles: “The worst thing on the metro is the lack of decent ventilation. And heaters that are on when they don’t need to be. This is now particularly important given the COVID situation.”

There were numerous comments expressing dissatisfaction with the number and layout of seats within trains, which was an agreed detail of the proposed train design and therefore not part of the consultation. Some participants expressed annoyance with not being given the opportunity to comment (e.g., “appalled by the lack of seats, you have not considered how elderly will cope, it looks like a cattle truck,” “Not bothered about the colour scheme. More seats are needed for people like me who can’t stand for more than 5 minutes”). Some participants were more direct (e.g., “Get rid of this more seats”), and others raised important issues to back up their claims (e.g., “this new seatkng [sic] arrangements are not family friendly nor friendly to those with disabilities who may not be wheelchair users”).

Although to a lesser degree, participants also discussed whether bicycles should be allowed on trains despite this not being part of the consultation as it related to transport policy in the region. Again, participants commented on unrelated parts of the website, were direct, and justified their viewpoints (e.g., “l would never allow bikes on the Metro because they often block peoples movements on and off the trains even though there is a designated space for them”).

Some participants chose to directly address Nexus or Tyne and Wear Metro in their comments (e.g., “Can I get on in my wheelchair at every station? With out help”).

4.10.3. Participants’ influence

Participants’ voices were clearly present throughout the consultation. However, how well this translated into positive influences on new trains was dependent on how Nexus balanced consultation findings with the practical constraints of supplying new trains within the manufacturing budget and timescale agreed with Stadler.

Our consultation did provide Nexus with useful insights on the proposed train design both within and beyond Nexus’ original scope for the consultation. In some cases, the consultation showed an overall public preference for one of the design options (e.g., double central grab pole), in other cases it demonstrated that none of the design options was suitable and further consideration was required. For example, workshop discussions and website comments revealed that none of the four design options for color combinations of internal doors, grab poles, and floor markings was suitable for visually impaired passengers. Workshop and website participants also suggested design amendments that could resolve this, which Nexus are considering for the final trains.

Nexus also took account of concerns outside the original consultation scope, notably participants’ dissatisfaction with the number and layout of seats. Whilst layout changes could not be accommodated within budget and timescale constraints, Nexus were able to add 12 tip-up seats in the multipurpose areas of trains.

Workshop discussions also raised specific design details that Nexus had not previously considered. Wheelchair users highlighted two concerns in particular with the wheelchair space – the need for something to hold whilst the train was moving, and social discomfort associated with frequently having to ask non-disabled people to vacate the wheelchair space. This led to the removal of perch seats from this area and the addition of a horizontal grab pole, as well as in-person involvement of several wheelchair-using participants in follow-up testing of the physical partial mock-up of the train interior.

5. Discussion

In Metro Futures 2020, we investigated how can entirely online public consultations be configured, via activities and digital interventions, to enable deeper participation at scale. The activities and digital tools we devised and employed addressed limitations previously observed in planning consultations (Howard & Gaborit, Citation2007) through enabling participants to interact with and immerse themselves in the proposed train designs, and link their feedback to particular design details. They also explored opportunities for the sorts of “deeper participation” observed in our 2016 work and highlighted in related research: experience-centeredness – including contextualized place-based experiences and emotions rather (Hoggenmueller et al., Citation2021; May & Ross, Citation2018; Vigar, Citation2017); imaginative exploration – including immersion and gamification (Gordon et al., Citation2011; Howard & Gaborit, Citation2007; O’Donnell, Citation2018; Thiel, Citation2016) and the exploration of design consequences (Yoo et al., Citation2013); and, giving voice – including involving those greatly affected by train design details designing the consultation (Carvajal Bermúdez & König, Citation2021; Fredericks et al., Citation2016; Koeman et al., Citation2015; Rodger et al., Citation2016, Citation2019), providing multiple opportunities for public engagement in online places (Koeman et al., Citation2015) and ensuring that public participation genuinely affects the final design (Sagaris, Citation2018).

Metro Futures 2020 is distinct from previous work in its specific context of a public consultation on train design, conducted entirely online via media and activities accessed through participants’ personal devices (smartphones, tablet computers, computers, etc.). Our analysis offers insights on how such projects can be configured to enable deeper participation at scale. Our evaluation showed that Metro Futures did enable large numbers of people to participate on the website whilst also demonstrating in-depth consideration of proposed train designs that went on to influence final designs. We did enable deeper participation at scale (at larger scales than workshops alone). To unpack how we enabled such deeper participation it is worthwhile returning to the concepts of moral and pragmatic value within Participatory Design (PD) (Simonsen & Robertson, Citation2013). Whilst being a “participatory project” (McCarthy & Wright, Citation2015) rather than explicitly claimed as PD, the effective aspects of our approach (in terms of experience-centeredness, imaginative exploration, and giving voice) demonstrate how public transport and urban planning consultations can deliver increased moral and pragmatic value. Our discussion therefore returns to these two concepts before proposing three practical strategies to enable a space for participation of varying depths and scales that can be transferred to other contexts.

5.1. Democratic value

The democratic value of design participation has been linked with empowerment through respecting participants’ personal and professional competencies, and transforming their practices. It is pertinent, then, to question how transformative public consultations can be if they are constrained to details such as the color and shape of grab poles on trains. Whilst radical transformation is unrealistic given the short rigid timescales of public consultations, Metro Futures 2020 does show that their democratic value can be increased.

Giving the findings Metro Futures 2020 produced across its different activities equal weight would have been problematic as it would have emphasized a consensus view and under-represented diverse and minority viewpoints. However, we addressed these issues in two ways. Firstly, we developed the website content with particular groups (including marginalized groups) to encourage others to consider more diverse passenger needs. This brought concerns from in-depth, narrow activities to activities at a wider scale. In particular, early discussions with representative groups enabled us to develop activities and media (notably personas and scenarios) that represented their concerns. Throughout the project, we also ensured that these groups were made aware of the consultation, and discussed how these participation opportunities could be made accessible (e.g., via British Sign Language interpretation).

Secondly, in reporting findings to Nexus, we took care to highlight significant concerns that were raised in workshops and website comments alongside consolidated quantitative data. In an internal report to their senior leadership team, Nexus noted that “Open Lab’s researchers were assertive in representing the passenger during the review stage which followed the final public consultation, and this has helped ensure that suggestions made were fully considered.” How Nexus chose to act upon consultation findings also plays a part here, both in applying their own expertise and in being open to changes beyond the consultation’s original scope.

This highlights that the democratic value of public consultations depends both on the activities and tools that configure them, and the manner in which they are reported and acted upon. Designers and coordinators of public consultation have a responsibility to surface relevant concerns that may result from deeper and narrower participatory activities with particular groups. And decision makers have a responsibility to balance the breadth and depth of feedback.

5.2. Pragmatic value

The pragmatic value of design participation depends on professional designers and participants learning together about concerns and potential solutions (Robertson & Simonsen, Citation2013). Such “mutual learning” (Robertson & Simonsen, Citation2013), therefore means that those who commission public consultations should be open to revising the scope of consultations in the light of their findings. The budgetary and time constraints, and momentum of large-scale projects, such as urban and public transport planning, may limit the ability of decision makers to respond to inputs. Too many constraints can hamper learning – a rigid agenda does not allow learning on concerns outside of it (Bedford et al., Citation2002). However, again, Metro Futures 2020 shows that constraints can be revisited and changes beyond the initial scope accommodated. Careful thought should go into the design of consultation opportunities so that they are commensurate with both what is being consulted on, and the opportunities that exist to shape the subject of the engagement.

The digital media and technology used in Metro Futures was central to delivering pragmatic value. Envisaging and exploring new trains enabled participants (and us) to understand them in relation to everyday lives and future experiences for ourselves and others. Such consideration of both “tradition” and “transcendence” (Ehn, Citation1988) provided valuable insights.

Unsurprisingly, deep-narrow activities such as workshops better enabled discussions and mutual learning between public and professional participants. But it is notable that the website also enabled exploration of concerns (e.g., in Journeys) and potential solutions (e.g., in Configure) from which valuable insights were derived.

5.3. Enabling a space for participation of varying depths and scales

It is tempting to equate the value of public participation in terms of its depth. However, Metro Futures 2020 demonstrates that large-scale public consultations can produce democratic and pragmatic value through enabling interconnected activities at varying depths and scales. Rather than considering people as those who want to engage and those who do not, a more sophisticated understanding is needed that allows people to have different interests, and accordingly, different levels of involvement with different topics and at different stages of engagement. Given the increased use of digital technology to facilitate engagement, there are opportunities to use it to provide a variety of topics, speeds and formats of involvement. This therefore suggests a space of participation rather than a linear continuum between the poles of non-participation and participation.

In Metro Futures 2020, we used digital media and technology to configure activities that both ensured representation at scale through allowing people to take part quickly and easily and supported more reflective and discursive engagements with design proposals. In doing so, we attempted to recreate the value of the in-person drop-in sessions in the 2016 consultations where we interested people during their everyday lives and invited them to become further involved. Online, lightweight activities such as Twitter poll votes were the gateway to more involved, deeper activities including workshops. The inclusion of links to the website in all social media posts encouraged participants’ further involvement on the website.

Vines et al. (Citation2013) observe that “rather than engaging in participatory design HCI researchers instead engage in acts of configuring participation” (p. 431, their emphasis), whilst Marres (Citation2015) notes that digital technology itself shapes participation. Our analysis of Metro Futures 2020, as a participatory project with democratic and pragmatic value, can therefore suggest transferable considerations for configuring public participation in large scale projects through digital technology.

5.3.1. Provide experiential context for design proposals