Abstract

Creating emotionally engaging mobile applications requires consideration of constantly evolving technology, content richness, usability, and user experience (UX). UX plays an important role in promoting long-term usage. We focused on the emotional aspects of UX design of mobile applications. In particular, we adopted the concept of feelings of being (FoB) – also known as existential feelings – in the context of mobile UX design. We presented an in-depth literature review covering 112 articles (2005–2021) on human-computer interaction, UX, mobile application development, mobile learning, and emotional engagement. Of these articles, 16 discussed FoB in the context of mobile applications. Building on the results of literature analysis and other previous research, we presented a FoB model for mobile application design comprising 13 FoB (ownership, engagement, contribution, security, trust, adjustability, enjoyment, empowerment, effectiveness, frustration, excitement, gratification, and needs fulfilment) and the hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of UX. Finally, we validated the FoB model through nine design projects, proposed design recommendations based on the model, and presented considerations on extending the model with additional elements.

1. Introduction

User experience (UX) is an important aspect of mobile application design and development that must be constantly monitored and improved. Identification of the experiential factors that have emotional consequences on users has been a challenge for UX researchers. Consideration of these factors during the design phase help increase user engagement and long-term usage (Goldman et al., Citation2020; Lützhöft & Ghosh, Citation2020). For example, in mobile learning (m-learning), where learning and teaching activities are facilitated through mobile devices (Wains & Mahmood, Citation2008), long-term usage implies that the learner engages emotionally in the learning process which Harley et al. (Citation2017) referred as emotion-aware learning technologies. Moreover, completing a task to the best of one's ability, purposefully, and with proportional effort is referred to as eudaimonia, which was originally translated as happiness (Kashdan et al., Citation2008), but has since evolved into meaningful and purposeful action. Conversely, happiness and joy represent hedonic aspects of product experience (Desmet & Hassenzahl, Citation2012). Both eudaimonia and hedonism have roots in ethical philosophy for exploring the meaning and answering the questions regarding good life and well-being. In this study, we hypothesize that the hedonic aspects (pleasurable) complement eudaimonic aspects (meaningful and purposeful action) (Huta & Waterman, Citation2014), and they all are essential for UX design.

Mobile applications and services are frequently designed and developed to address mobility issues. M-learning applications, for example, aim to overcome the constraints of traditional educational settings, such as learning and teaching in a classroom. To ensure a mobile application's competitiveness, we must emotionally engage users in the same way that entertainment and social media applications do (Goldman et al., Citation2020; Lützhöft & Ghosh, Citation2020).

In a previously study, m-learning UX literature was divided into three eras (Dirin & Nieminen, Citation2018). The first era took place during 2000–2004 (Garrett, Citation2000; Roto, Citation2006) and can be defined as the technical approach to UX. The second era of UX can be traced to the period of 2005–2010, and it concerns functionalities and usability. The third era emerged after 2010 and deals with users’ feelings and emotions toward m-learning applications. In another classification, Hassenzahl and Tractinsky (Citation2006) identified three major types of UX for information technology products: (i) emotion aspects, such as users' emotional expectations and needs; (ii) system design aspects, such as usability, the system's purpose and functionality; and (iii) the context in which the product is used, such as the social setting. Human-computer interaction (HCI) and related technologies rely heavily on emotions (Hudlicka, Citation2003). In this study, the term emotional engagement refers to the feeling that users construct through their emotions (Ekman, Citation1999) and cognitive development in terms of values. Furthermore, our focus is on the feelings of being (FoB), which are existential feelings that affect the way we react to the world as well as our attitudes and dispositions to act (Ratcliffe, Citation2005). Ratcliffe (Citation2005) stated that these feelings contribute to the foundations for emotional and cognitive experiences.

In this study, we reviewed and analyzed related work that address emotions and feelings in UX design of mobile applications, resulting in a FoB model for UX design. illustrates the process of the development of the FoB model. An initial systematic literature review (SLR) on m-learning UX and evaluations of a number of application designs were published in a dissertation in 2016, which proposed a UX design framework for m-learning applications (mLUX) (Dirin, Citation2016). Later, we developed several new application designs, such as a context-aware basketball learning application (Dirin et al., Citation2020) and context-aware driving school application (Dirin & Casarini, Citation2014) that helped us identify additional FoB, and contributed to a context-aware tourism application to validate the identified FoB (Dirin et al., Citation2017). In the current article, we extend the search period for SLR results to 2021 and the scope to the field of human-computer interaction.

Figure 1. The process of developing the FoB model for UX design. SLR: Systematic literature review; FoB: feelings of being; mLUX: mobile learning user experience.

1.1. The importance of emotions and feelings

Recognizing emotions and other affective factors is important in HCI (Calvo, Citation2010). People have different beliefs and desires that they want to fulfil, and their emotional experiences or feelings show how these beliefs and desires have been met through interaction with their surroundings (Reisenzein, Citation2009). Loewenstein et al. (Citation2001) demonstrated that feelings affect our decision making, especially in risky and uncertain situations, indicating that feelings and emotions influence our behavior. According to Jekauc and Brand (Citation2017), desirable activities will be pursued with more engagement and persistence than undesirable activities. We also engage in a variety of actions and behaviors to regulate our emotions; for example, Kemp and Kopp (Citation2011) demonstrated that individuals regulate their emotions by consuming hedonic products. As a result, good UX design not only focuses on increased engagement and persistence but also has an indirect effect on the regulation of the user's emotions.

Carver and Scheier (Citation1990) showed that progress in reaching a goal is associated with many pleasant and unpleasant feelings, such as excitement and frustration. Emotion theories in psychiatric and neuroscience research have demonstrated that humans are endowed with a basic set of emotions (Ochsner & Barrett, Citation2001). Each emotion is linked to psychological and physiological responses. However, there are many feelings that we do not often consider to be standard emotions, such as feelings of unfamiliarity, engagement, isolation, belonging, and ownership. FoB, as defined by Ratcliffe (Citation2008), differ from emotions in that they are not limited to emotions. Examples of FoB are feelings of loneliness, belonging, separation, power, and control. Ratcliffe (Citation2008, p. 36) called these types of feelings “existential feelings” and suggested that such non-emotional feelings are ways of finding ourselves in the world. Stephan (Citation2012) divided existential feelings into three primary relations: with oneself, with the social environment, and with the world. Silvia (Citation2009) added knowledge emotions (interest, confusion, and surprise), hostile emotions (anger, disgust, and contempt), and self-conscious emotions (pride, shame, and embarrassment) to the list. According to the appraisal theory (Nerb, Citation2015), these emotions are invoked on the basis of subjective evaluations of the significance of a situation, object, or event.

1.2. Contributions

In this article, we first conduct an SLR to address the conceptual basis of contemporary UX, in particular, the emotions and feelings in mobile application design processes, with an emphasis on m-learning applications. Then, we construct the FoB model, which is aimed to be used in mobile application UX design, on the foundations of Karapanos et al.’s (Citation2009) Temporality of Experience model, Hassenzahl et al.’s (Citation2013) work on experience design and happiness, Ryan et al.’s (Citation2008) self-determination theory on eudaimonia, and Karahanoğlu and Bakırlıoğlu’s (Citation2020) Path to Long-Term User Experience model. These previous models fail to identify the feelings that users may have at each stage of the application use that the designer must consider. This is the research gap that we seek to fill with our work by proposing a new model that takes into account the user’s feelings during application usage. The FoB model also takes into account the hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of the UX design.

The model is applied to nine mobile application development projects to evaluate the model’s feasibility, performance, and applicability in a broader context of mobile applications beyond m-learning. The outcomes of the evaluations deliver practical examples on the usage of the model, which other practitioners and researchers can refer to. Finally, we elaborate on the performance and position of the model among other UX design models, methods, and practices, and provide design recommendations based on the findings.

2. Defining and advancing UX

Forlizzi and Ford (Citation2000, p. 419) defined experience as “the constant stream that happens during moments of consciousness,” indicating that UX dimensions include the subconscious, cognition, narratives, and storylines. The user experience is defined as the subjective feeling that the user has about a product (Salehudin et al., Citation2020). Experiences can be interpreted as stories that we recall and share with others in a variety of contexts. They may also cause changes in the user's behavior. UX has been considered an important element in mobile application success (Roto et al., Citation2010) and has become a viable supplement to the traditional HCI design, as indicated in practitioner discussions (Sakhardande & Thanawala, Citation2014). Furthermore, UX design is a multidimensional phenomenon in which many factors influence success. According to the International Organization for Standardization (Citation2019), UX is defined as a “person's perceptions and responses that result from the use or anticipated use of a product, system, or service.” Nielsen and Norman (Citation2016) defined UX as the ease-of-use and elegance of a product that users enjoy owning and using. Hassenzahl and Tractinsky (Citation2006) identified the facets of UX as beyond instrumental, emotion and affect, and experiential, thus providing a broader definition of UX. The beyond instrumental facet mainly concerns humans' non-functional needs to achieve their goals, such as the hedonic aspects that the product or service fulfills. This study focuses on the user's FoB during different stages of mobile application use. In the following sections, we explore the theoretical foundations of the proposed FoB model.

2.1. Temporality of experience

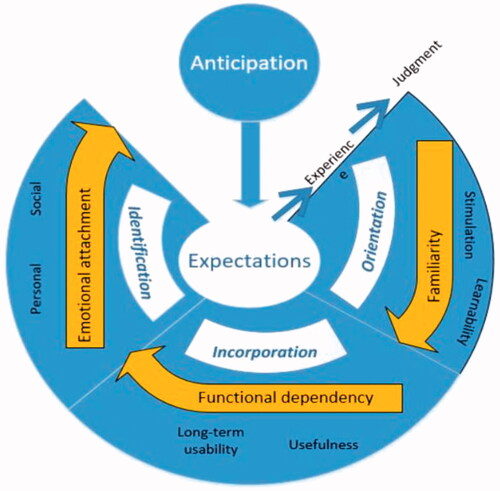

Karapanos et al. (Citation2009) developed the Temporality of Experience model on how UX is constructed over a product's life cycle of usage, which is presented in . The model consists of three main forces: familiarity, functional dependency, and emotional attachment. These forces shift UX in three phases of product adaptation: orientation, incorporation, and identification. In the orientation phase, the concerns are ease-of-use and stimulation. If users encounter problems while using the product, they may become frustrated. However, as users become more familiar with the product, this sensation fades. The usefulness and various features of the product construct the experience during the incorporation phase. Usefulness and usability factors become more important. In the identification phase, emotional attachment to the product increases. The product becomes part of daily life, becomes involved in social interactions, and communicates self-identity. Anticipation leads to these phases, conveying users' expectations before actual new experiences.

Figure 2. The temporality of experience model (Karapanos et al., Citation2009).

2.2. UX in mobile application context

Users seek new mobile applications with a sense of anticipation, which stems primarily from their curiosity about the applications’ potential and capabilities. Moreover, propelled by the anticipation of an experience, expectations are formed before any actual use takes place. In the orientation stage (Karapanos et al., Citation2009), users are greeted with a feeling of excitement as well as frustration as new features are uncovered and problems, such as learnability issues, are encountered. Furthermore, users are required to learn new features and functionalities offered by the new application.

In the incorporation stage of mobile application usage, the user focuses on the application's functionality and usability attributes, such as ease-of-use, effectiveness, and efficiency. The user begins to explore new features, identify novelties, and experience the ease-of-use of the new medium. Exploration of new features and novelty in an application increases interest and excitement (Barto et al., Citation2013). In addition to new functionality, excitement can arise in mobile applications such as m-learning from a new combination and interactivity between educational performance and rewards. Usability and satisfactory features are prerequisites but are not sufficient for developing a positive experience. Intriguing new features need to be realized in a convenient manner from the user’s perspective (Berry et al., Citation2002).

The identification stage involves the formation of emotional engagement with the application based on accumulated experience. For example, in the m-learning context, identification may occur when users feel that the m-learning application is a tool that can help them achieve their educational goals, consequently feeling incomplete without them while performing their educational duties. The existing tools and media may become insufficient for the user to become engaged and fully utilize the application's capabilities. The expectations and needs for the future emerge from the experience of insufficient performance in advanced application usage. Thus, users begin to move to better-performing applications with more technological capabilities and functionalities. In turn, this is followed by the projection of future capabilities and features of the new applications. Therefore, designers and developers of mobile applications must constantly monitor the latest technology and their users’ expectations to keep their application as the preferred mobile application.

2.3. Path to long-term UX model

Karahanoğlu and Bakırlıoğlu (Citation2020) proposed the Path to Long-Term User Experience (PLUX) model for the UX design process based on the Temporality of Experience model. PLUX is intended to aid designers in the product design process to provide a long-term UX. The model consists of four phases: (i) before acquiring, the user's mental model from the previous product must be unfolded by a new product with more extensive experience; (ii) learning, the user explores the new features and starts to understand those; (iii) mastery, the user merges the previous experiences into their experiences with a new product; and (iv) post-mastery, the user utilizes the product daily to perform their tasks. Karahanoğlu and Bakırlıoğlu (Citation2020) extended the model of Karapanos et al. (Citation2009) by designing a new product while keeping the user's existing mental model of previous products in mind.

2.4. Eudaimonia and hedonism in UX

The term eudaimonia, which translates as happiness in English, appears frequently in ancient Greek philosophical texts and books. However, scholars now disagree with this translation and believe that eudaimonia is more associated with achievement, well-being, and living well (Ryan et al., Citation2008). Ryan et al. (Citation2008) argued that eudaimonic living can be achieved by: (i) pursuing own intrinsic goals; (ii) being autonomous rather than heteronomous; (iii) acting with awareness; and (iv) fulfilling the psychological needs for competence. Therefore, current psychology defines eudaimonia as an intrinsic goal for well-being, whereas the original definition mainly considered eudaimonia as an extrinsic motivation or hedonic aspect. As a result, eudaimonia is defined as an individual's best and full capacity to perform.

Mekler and Hornbaek (Citation2016) investigated the eudaimonic and hedonic aspects of UX. They discovered that hedonism is primarily concerned with pleasures, delightfulness, and relaxations, whereas eudaimonia is concerned with recognizing individual beliefs, personal best achievement, ability to grow, and competence through self-determination. Conversely, cognitive psychologists believe that the hedonic aspects are also achieved through eudaimonia, which is rooted in motivations and not the experience itself. Therefore, eudaimonia encourages individuals to learn new things and strive to develop competencies. However, some psychologists, such as Peterson et al. (Citation2013) argued that both pleasure and meaningfulness contribute equally to an individual’s well-being. This is consistent with the recommendation of Hassenzahl et al. (Citation2013) that pleasure and meaningfulness should be prioritized in UX design.

2.5. Emotions and feelings in mobile application UX

Emotional engagement with a mobile application is constructed over time, and as the user increasingly engages with the application, usability ceases to be the main concern. The hedonic aspects of the application become apparent as the functional and non-functional features meet essential needs, thus making application use enjoyable (Lu et al., Citation2017). Aside from developing a dependency on the application based on human nature, additional demands and more features and capabilities are developed in terms of seeking a better and completed product. For example, after using an existing application over time, the user might begin to develop demands for complementary features based on newer applications; e.g., I wish my application to contain these features that the new competing product has. As a result, future application potential and technological capabilities are expected to be projected. This includes utilizing new technologies to empower users in the use of applications.

Meschtscherjakov et al. (Citation2014, p. 2319) argued that mobile phones' ability to empower, enrich, and gratify users contributes to self-concept and emotional attachment. They defined mobile phone emotional attachment as “a cognitive and emotional target-specific bond connecting a person's self and a mobile phone that is dynamic over time and varies in strength.” Such emotional attachment manifests in various forms, such as digital ownership (Greengard, Citation2012) as well as emails, SMS, and other important digital items for users. Moreover, emotions and feelings have proven to influence mobile applications' continuous usage (Dirin et al., Citation2017).

Without constraints to mobile application domain, and with respect to identifying and expressing feelings in general, Willcox (Citation1982) presented the Feeling Wheel, a tool for expanding awareness of emotions, to facilitate more elaborate discussion about feelings that might otherwise remain unexpressed. Willcox’s model contains expressions of six primary feelings connected to supplemental 72 secondary feelings. Willcox reports having used her model to assist people to identify, express, generate, and change feelings. While the Feeling Wheel is intended to be used in therapeutic settings, its use illustrates means to introduce supplemental vocabulary on experiential aspects for people who are not normally exposed to such themes. Drawing on the content and uses of Willcox’s model, we aim at introducing FoB as complementary concepts for mobile service developers to elaborate on experience through more explicitly articulated feelings.

3. Research goal, questions, and methodology

The goal of this study is to develop a UX model for mobile applications that addresses emotional engagement with a focus on FoB. Our study aims at contributing to our understanding of FoB in the mobile application UX design and research domains. We contribute to the development of future mobile applications which can deliver enhanced UX through seamless and pleasurable interaction, long-lasting engagement, meaningful and valuable functionality encompassing the hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions. To achieve this, we seek answers to the following research questions:

What are the FoB in UX for mobile applications?

How can the FoB support UX design of mobile applications?

We seek to answer these questions by using two methods: an SLR, which resulted in the first draft of the FoB model, and a formative evaluation of the model through nine case mobile applications, which contributed to an enhanced model as well as identification of design recommendations.

This work is a continuation of our previous research (Dirin, Citation2016) around m-learning UX. Accordingly, m-learning, as a subset of mobile applications, has a strong presence in the current article. The lack of UX design tools regarding the experiential aspects of mobile application design drove the development of the experiential FoB model described in this article. The model aims to help mobile application designers elicit FoB for positive engagement already at the design phase. Due to the background of this research, the SLR searches were focused to publications within the context of m-learning. However, we the identified FoB are potentially generic and also applicable to other mobile application designs. We verify this by evaluating the model by applying it to design processes of nine different mobile applications for various usage contexts. We acknowledge that the m-learning foundation of the model is a limitation and identify topics and expansion of future research toward broadening the mobile application UX design domain.

3.1. Systematic literature review

We applied a set of guidelines and procedures for performing systematic reviews in software engineering (Kitchenham, Citation2004). Our literature search was also supported by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (Liberati et al., Citation2009). The focus of our literature review was on papers published between 2005 and 2021 on various topics, including HCI, m-learning application development, usability, UX, emotional engagement, and FoB. The aim was to identify primary studies related to the research questions through the use of an unbiased search.

To narrow our focus on high-quality publications, we used the Publication Forum, a Finnish-curated quality assessment system for scientific publication channels, to assess the quality of the selected papers and their places of publication (i.e., conferences/journals). The search and review protocol for identifying the literature was as follows:

In-depth evaluation of research undertaken on emotional engagement, UX, and FoB.

In-depth analysis of research on m-learning design methodology, usability, and UX conducted by accredited scholars and researchers.

Primary keywords/phrases: “user experience AND feelings of being,” “user experience AND emotional engagement,” “user experience AND mobile application,” “usability and mobile application,” “m-learning AND development methodology,” “m-learning AND usability,” and “m-learning AND user experience.”

For the articles identified by the keyword search, we used the following inclusion criteria:

The article is published between January 2005 and April 2021.

The article is written in English.

The main focus of the article is on emotional engagement, UX, FoB, usability, UX design, and/or mobile application development framework.

The article is not a duplicate of a previously found article.

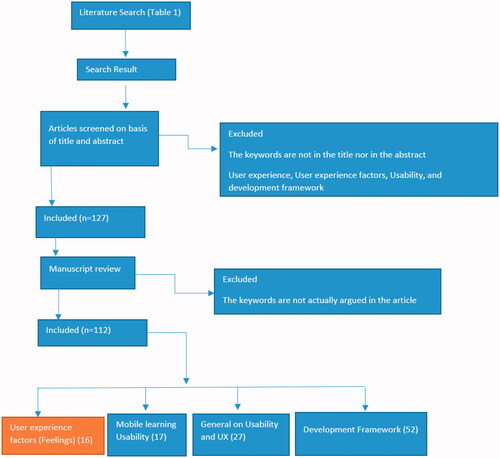

In , we list all the journals and conferences in which we conducted our literature search. The publication counts indicate the numbers of articles that passed the inclusion criteria. The process of searching and selecting the publications is presented in the flow chart shown in .

Figure 3. Flow chart of the process of searching and identifying publications for different categories. The identified 112 publications contribute to user experience factors (feelings) (n = 16), mobile learning usability (n = 17), general on usability and UX (n = 27), and development framework (n = 52). Further details are in Supplemental Appendix A (the PRISMA report).

Table 1. Publication forums and the numbers of initially selected publications in them.

As a result of the keyword search, 127 publications were returned; this number was decreased to 112 after further exclusions based on our analysis. Of these, 16 articles mentioned or referred to particular feelings and 15 of them were published after 2011, which coincides with the beginning of the third era of mobile application UX. This trend indicates that emotional factors have become increasingly important in HCI research.

3.2. Formative evaluation of the FoB model

The aim with our formative evaluation is to give feedback on the characteristics and features of the FoB model. The evaluation was conducted in nine mobile application development projects. The mobile applications were designed by nine teams of students during a variety of courses (e.g., User Experience Design, Digital Service Design, and Digital Service Project) at the Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences. In almost all cases, the design was conducted for a client company. We provided the designers with guidelines including the steps needed to ensure that the application design considers the identified FoB (see the second column in Table B.1 in Supplemental Appendix B). Additionally, in the application evaluation phase, the designers self-assessed their application on how potential end users can perceive the FoB. Therefore, we provided an evaluation form (see Supplemental Appendix B) to the designers concerning how the FoB are expressed in their design. Additionally, the applications were tested at a usability lab with potential end users who were recruited in accordance with the context of the applications (e.g., from the client companies). The designers employed three to seven test users per application to perform a set of predefined tasks. After completing the tasks, the test users filled out a web-based questionnaire (Supplemental Appendix C) that we provided as a template and that aimed to investigate if and how the test users experienced the FoB.

The purpose of using FoB in UX design is to tune developers to consider experiential aspects which would otherwise remain unattended. The designers were able identify relevant FoB and utilize them in their design and development work. The emphasis of different FoB varied between application domains. The FoB facilitate the exploration of the specific experiential aspects of the application, which would not be explored otherwise. More detailed results of the formative evaluation results are presented in Supplemental Appendix D.

4. Modelling FoB for emotional engagement in mobile applications

In this section, we describe the FoB identified in our SLR, followed by an analysis of their connections to emotions, hedonism, and eudaimonia. These findings are then synthesized into a model of FoB, thus forming the main contribution of this study.

4.1. FoB in mobile applications

In this section, we describe the FoB that were identified from the SLR as well as other significant sources. The identified FoB are summarized in and further elaborated in the following subsections. The FoB investigated in this study are primarily focused on mobile application UX. Therefore, in digital service UX at large, the landscape of FoB is likely to be wider than what we present in this article. The definitions and details of the FoB are presented in the following subsections. These FoB have been defined by previous work outside the domain of mobile applications. We present the FoB with references to defining literature and link them to the results of our literature review, thus showing their relevance in the context of mobile applications.

Table 2. Summary of the defined FoB and key sources.

4.1.1. Feeling of ownership

The feeling of ownership in the context of mobile application means, I am in charge, and I can use this the way I want to. The concept of ownership has been debated by researchers in various disciplines, such as anthropology, psychology, and philosophy. We focus on the psychological and socio-psychological aspects of ownership. Pierce et al. (Citation2001, Citation2003) defined psychological ownership as the way in which people develop feelings of ownership for different material and immaterial objects. The feeling of ownership, which Meschtscherjakov et al. (Citation2014) referred to as digital possession and Greengard (Citation2012) called virtual possession, develops as the user finds the mobile application to be satisfactory, effective, and efficient. Isaacs (Citation1933) discovered that ownership as possessiveness develops at a young age and is strong and complex in young children, and Pierce et al. (Citation2001) proposed that psychological ownership is motivated by intra-individual motivations such as efficacy, effectiveness, and self-identity. Moreover, Liu et al. (Citation2012) demonstrated that the positive effects of the control experience are mediated by psychological ownership, whereas Belk (Citation1988) defined possession as storing memories and feelings about the past, present, and future, which we can connect. Sinclair and Tinson (Citation2017) studied psychological ownership and music streaming consumption and found that, among other things, loyalty, empowerment, and social rewards lead to psychological ownership. The findings of these previous studies indicate that psychological ownership is a multi-faceted phenomenon that has the potential to strongly influence the way the user experiences a mobile application.

4.1.2. Feeling of engagement

The feeling of engagement in the context of mobile applications means, the application makes me feel included and I feel engaged with the application. This can be seen in Rovio's cartoon series, Om Nom (Gaudiosi, Citation2015) where the cartoon character stops and asks the children to find differences between two screenshots of the cartoon. A phrase like I cannot wait to see the next new content exemplifies the result of this FoB. By interacting with contents, which is shown by Wang et al. (Citation2018), the user feels as if they are a part of a larger entity, perhaps a story. In other words, the user feels that they are an actor in this storyline. Additionally, Siti et al. (Citation2014) demonstrated that student engagement in learning activities is an indicator of achievement in m-learning.

Enthusiasm is a concept closely related to the feeling of engagement (Russell, Citation2003). The user’s engagement with the application results in active, positive, and vigor feelings that lead to enthusiasm. In the learning context, the feeling of engagement can help learners proactively pursue to learn (Redmond & Macfadyen, Citation2020).

4.1.3. Feeling of contribution

The feeling of contribution in the context of mobile application means, I deliver important things to others and to myself. Already in 1930, Alfred Adler stated that people tend to perceive themselves as useful to their community or to an individual (Adler, Citation1930). As a result, the feeling of contribution brings happiness and makes one feel worthy. The feeling of contribution therefore means helping, giving, and supporting an individual, groups, and themselves. For example, in a positive work reflection, the feeling of contribution increases proactive behavior (personal initiative and creativity) as well as organizational citizenship behavior (Binnewies et al., Citation2009). In line with this, Anik et al. (Citation2009) demonstrated that charitable and giving behavior increases happiness. Gomez et al. (Citation2010) and Ciampa (Citation2014) also showed that motivation, enjoyment, and contributions all have a positive effect on the learning process in the context of m-learning. Moreover, m-learning applications promote the feeling of contribution through construction and sharing of social knowledge (Lan Yu-Feng et al., Citation2012).

4.1.4. Feeling of security

The feeling of security in the context of mobile application means, others do not see my personal data and my information will not be exposed to others, and I can make mistakes with the application without fearing of being improperly monitored. According to the Maslow’s hierarchy or needs (McLeod, Citation2007), security and safety needs are among the primary human needs. The feeling of security includes protection from elements, order, law, stability, and freedom from fear. It is associated with a physical reaction such as a need for protection, and mental security refers to the feeling that we have control over our lives. The sense of security over the use of mobile application is developed over a period of time. Additionally, feeling secure with a mobile application impacts how the user is using the application. This is demonstrated by Androulidakis and Kandus (Citation2012) in their study which discovered that mobile phone users who believe that mobile communications are secure are less cautious about their security practices. According to Redmond and Macfadyen (Citation2020), the feeling of security is a priority to be considered in the learning context.

4.1.5. Feeling of trust

The feeling of trust in the context of mobile application means, I do not lose my data or I am safe using this application, and it is strongly connected to reliability, as poor reliability leads to decreased trust. Trust is a mental attitude that leads to the feeling of confidence. According to J. Kim and Moon (Citation1998, p. 3), the feeling of trust in systems with utility is an important component of “emotional usability.” Wixom and Todd (Citation2005) addressed reliability, stating that the user satisfaction literature explicitly enumerates system and information design attributes such as information accuracy and system reliability. Trust, according to O’Neill (Citation2012), has become an important factor in any information society. Nie et al. (Citation2020) showed how trust plays an important role in online transactions. Moreover, in the context of m-learning, Ibrahim and Walid (Citation2014, p. 1) suggested that the effectiveness of m-learning is still questioned because of the “reliability, accuracy and validity of its content deliverables.” These studies and findings support the inclusion of trust and reliability in the analysis and development of mobile applications.

4.1.6. Feeling of adjustability

The feeling of adjustability in the context of mobile application means, I can fit/adjust the service/application to my needs, and I can use the app at convenient times and locations. Merriam Webster (Citation2022) defines the verb “adjust” as “achieving mental and behavioral balance between one’s needs and the demand of others.” The extent to which a mobile application can be personalized and customized is referred to as adjustability. Marathe and Sundar (Citation2011) defined customization as activities that users take to modify some aspect of an interface to a certain degree based on their own personal relevance. Schmierbach et al. (Citation2012) found that fulfilling the need for personalization leads to enjoyment of a driving game. Marathe and Sundar (Citation2011) discovered that customization is positively associated with the sense of control and sense of identity, and that sense of identity mediates sense of control. Product customization, according to Du et al. (Citation2006), is an effective method of meeting the needs of individual customers. Finally, learners use different learning strategies in the m-learning context (Teklehaimanot, Citation2015) due to their different cognitive styles (Riding & Sadler‐Smith, Citation1997), which can be addressed in m-learning applications through adjustability (Glavinic et al., Citation2008).

4.1.7. Feeling of enjoyment

The feeling of enjoyment in the context of mobile application means, I am enjoying using the app. Izard (Citation1977) defined the feeling enjoyment as a feeling of being satisfied with, or become pleased with or about something. Izard (Citation1977) believed that when the feelings of interest and enjoyment occur together then the user experiences fun. In the Feeling Wheel (Willcox, Citation1982), joyfulness results in content, which invokes the feeling of happiness. Moreover, Davis et al. (Citation1992) identified enjoyment as a key factor in technology adoption. Aligned with this, Brandtzaeg et al. (Citation2018) investigated what makes an experience enjoyable. They found that in an enjoyable design the user is in control with appropriate challenges. Furthermore, the user is able to personalize the product and they feel being a part of the activities. In the context of m-learning, fun and delightfulness can improve learning in children (Fontijn & Hoonhout, Citation2007), and the fun factor of the learning experience is measurable (Tisza, Citation2021). Perry (Citation2017) recognized lifelong learners as those who derive pleasure and enjoyment from discovering new things. Similarly, Haciomeroglu (Citation2017) showed that the student's feeling of engagement of mathematics is determined by the degree to which they enjoy it. This is also aligned with Harley et al. (Citation2019) who suggested that technological competences bring higher feeling of enjoyment, which also correlates with learning among mobile application users.

4.1.8. Feeling of empowerment

The feeling of empowerment in the context of mobile application means, the application enables/makes/persuades me to use my full capacity, and I can exceed my skills and abilities with the application. Perkins and Zimmerman (Citation1995) defined empowerment as an intentional process, critical reflection, and group participation or the process that makes people be in control over resources. Furthermore, they argued that empowerment is associated with both processes and outcomes where the processes often are based on some activities. Barkhuus and Polichar (Citation2011) demonstrated that mobile phones can empower individuals through various technologies. Amichai-Hamburger et al. (Citation2008) identified four levels of empowerment effects: (1) personal, (2) interpersonal, (3) group, and (4) citizenship. Empowerment as an internal process means that an individual believes in his or her ability to make a conscious decision. Doumen et al. (Citation2021) defined empowerment as a social process that assists people in gaining control of their own lives, and proposed that the focus of empowerment is on the ability to control one's own destiny. Thus, empowerment is a psychological process that occurs within an individual.

4.1.9. Feeling of effectiveness

The feeling of effectiveness in the context of mobile application means, the service and the application help me conduct my daily activities effectively. Merriam Webster (Citation2015b) defines effective as “producing a decided, decisive and desired effect.” Irrespective of their behavioral personality, humans tend to strive toward recognition, belonging (K. J. Kim et al., Citation2012), and being effective. Moreover, being effective is an integral part of our human nature that we develop while growing up. For example, although children's activities are not always associated with a goal, they are often effective and engaging, even if the outcomes are not always efficient, which is different in joint and collaborative tasks they undertake (Hamann et al., Citation2012). This issue was also recognized by Yetim and Yetim (Citation2014), who elaborated on two different human needs: trust and need to belong. The feeling of trust is developed when the user feels that the application has value and effectiveness in various contexts. This is demonstrated Pangil and Moi (Citation2012) who discovered that trust has impacts on knowledge sharing and virtual team effectiveness.

4.1.10. Feeling of frustration

The feeling of frustration in the context of mobile application means, the service frustrates me when it does not work the way I want, and the service does not respond in the way I expect. Merriam Webster (Citation2015a) defined frustration as “the impediment to the advancement, success, or fulfilment of something.” Abler et al. (Citation2005) defined frustration as the emotional reaction to not achieving the desired goal. It is a negative feeling experienced in situations where the system behaves differently from what the user expects. Savioja et al. (Citation2014) asserted that user’s lack of frustration with a complex system is considered a sign of good UX. Furthermore, they argued that the feeling of frustration is the most negative feeling during the application’s usage. Abler et al. (Citation2005) demonstrated that the absence of rewards can lead to a sense of frustration. Moreover, Lee et al. (Citation1994) discovered that defeat and negative experiences can cause frustration. In the context of education, Kapoor et al. (Citation2007) created an intelligent tutoring system that predicts learner frustration and intervenes to help learners who are otherwise likely to quit.

4.1.11. Feeling of excitement

The feeling of excitement in the context of mobile application means, the service thrills me when I explore the unexpected features and functions. In the Feelings Wheel (Willcox, Citation1982), the feeling of excitement is associated with enthusiasm and passion which leads to a joyful emotion. Based on Robert and Lesage (Citation2012), the feeling of excitement is a subjective feeling that can be measured best through an individual’s behavior. Hassenzahl (Citation2008) argued that excitement is used to determine the level of arousal in interactions. Moreover, excitement appears or is expressed in different situations. Brooks (Citation2014) demonstrated that excitement can be derived from anxiety. In accordance with this, Jayawardhena and Wright (Citation2009) showed that a positive word-of-mouth about a product can generate excitement. Moreover, Ciampa (Citation2014) showed that the feeling of excitement as an important factor in engaging users in m-learning applications.

4.1.12. Feeling of gratification

The feeling of gratification in the context of mobile application means, I am grateful that I can perform my tasks through the application. Merriam Webster (Citation2015a) defined gratification as “a source of satisfaction or pleasure.” McCullough et al. (Citation2001) considered gratitude a moral emotion, akin to guilt and empathy, whereas Wood et al. (Citation2008) demonstrated that gratitude increases satisfaction with life. This was also investigated by Welch and Morgan (Citation2018) on a mobile dating application. According to their results, gratification leads to different behaviors and emotional outcomes. This aligned with Possler et al.’s (Citation2020) finding that the gratification in gaming correlates with the player’s enjoyment. Finally, in Willcox’s (Citation1982) Feeling Wheel, thankfulness and love are associated with happiness.

4.2. Interrelations between FoB, emotions, hedonism, and eudaimonia

Emotions are reactions and the driving force of our behavior which can be both helpful and unhelpful. Emotions are the results of our brain, which is always alert for threats or rewards. As soon as either of these activated, the brain releases chemical messages which travel across our body, thus triggering the body to respond accordingly. In the case of a reward, our brain fires dopamine substance which results in a good feeling and motivation factor to continue the action. Feelings are the awareness of the emotions, which often occurs before the thinking starts, hence the reaction to the feeling dominates our thinking; that is why irrational thinking may occur. Therefore, our emotions influence also our behavior. Furthermore, just thinking about something can evoke emotions as well, e.g., thinking about a dangerous situation. Therefore, emotions have a direct role in experiencing the world and achieving our goals. Feelings, on the other hand, are mental reactions to emotions that are often rooted in our temperament, experience, and personal characteristics. Thus, emotions are based on an occurred event, and feelings are learned reactions which are invoked by external stimuli; happiness, for instance, is an emotional state characterized by joy, satisfaction, and fulfillment. We feel joyful without a conscious decision, while becoming happy is dependent on an outside condition. presents the interrelations between the FoB, associated emotions, hedonism and eudaimonia that we identified based on the research.

Table 3. Interrelations between FoB, emotions, hedonism and eudaimonia.

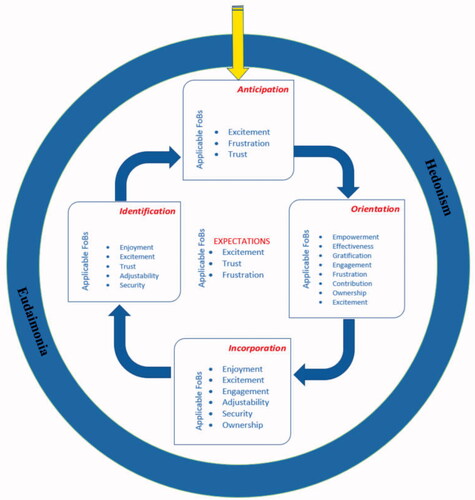

4.3. Fob model for mobile application UX design

Feelings and emotions play a big part in continuous usage of mobile applications (Ding & Chai, Citation2015). On the basis of the evidence gathered from the literature, this study discovered that FoB are important in UX design of mobile applications. In , we propose a model of FoB for mobile application UX design based on the Temporality of Experience model proposed by Karapanos et al. (Citation2009); the elaboration of experience design and happiness by Hassenzahl et al. (Citation2013) in which the fulfilling of psychological needs affects positive feelings, meaning, and hence results in happiness; and the self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia by Ryan et al. (Citation2008) The model suggests that users of a mobile application can experience a wide range of FoB depending on the stage at which they are in application usage.

Figure 4. FoB associated at each stage of the FoB model in conjunction with hedonic and eudaimonic experiences.

As indicates, expectation has influence on all stages of the proposed model. However, in this study, the specific expectations of each stage are not elaborated on but are left for a future study. The user's emotional dependency on a mobile application depends on the stage at which they are using the application. As illustrated in , however, the application's ability to promote eudaimonia will determine the user's level of engagement. In the following sections, we describe the stages and the FoB included at each stage.

4.3.1. Entering the UX cycle: forming of expectations

The tendency of humans to stick with the current behavior and pattern and ignore alternative approaches is known as inertia or resistance to change in human-computer interaction (H.-J. Kim et al., Citation2017). A designer must, therefore, learn the behaviors and patterns of their users to overcome the inertia; this is the prerequisite for entering the UX cycle and forming an emotional attachment, which indicates that the user values the application. As a result, the user is reminded to keep an eye out for similar services, products, features, and technologies in his or her surroundings. New and emerging features and technologies, as well as competing services, raise expectations for improvements to the existing application. According to Karapanos et al. (Citation2010), anticipation leads to formation of expectations. Furthermore, at this stage, excitement over the seminal, novel, and surprising features leads to deliberation over whether to continue or discontinue the current application use. At the stage of forming expectations on the anticipated product or service, which frequently occurs during marketing and sales activities, increasing excitement towards product, familiar and trusted actors and brands have a greater ability to pique the user’s interest than unknown actors and brands. Moreover, users may feel frustrated during this phase because the current application's functionalities do not meet their needs. They may thus look forward to an intriguing application to empower them to perform tasks more efficiently and effectively. In the exploration of new opportunities regarding new applications, users anticipate and expect improved abilities that reach beyond the capabilities of their currently used applications.

4.3.2. Orientation stage

At the orientation stage, functional dependency is salient. First, functional dependency necessitates the existence of the anticipated functionality. Second, given the expected benefits, the user must be able to learn the function and adapt to the application in a reasonable amount of time. If the learning time exceeds the expected benefit threshold, the user may become frustrated and stop using the application. Third, the functions of the application must appear meaningful to the user. During this stage, the user begins to use the application and gains firsthand experience with it. Karapanos et al. (Citation2009) identified two different feelings associated with this stage: the feeling of excitement in exploring new features and the feeling of frustration in learning new ways to handle tasks. At the orientation stage, which often deals with experimenting with the use of the application, users encounter novel concepts and opportunities that require attention to learn and adapt to the application.

4.3.3. Incorporation stage

The incorporation of an application is enabled through long-term use. Smooth usage promotes the development of ordinary, everyday practices, thereby transforming the application into a habit. Long-term use leads to the resolution of minor complexities in application usage. Users develop feelings of engagement and ownership at this stage, especially when they can adjust and customize the application to their own needs and preferences. Moreover, users feel excited when the application works well with other applications in their device, which help ensure that tasks are performed more efficiently. Karapanos et al. (Citation2009) referred to this stage as the realization of usability and usefulness, in which users experience feeling of engagement with the application. Furthermore, the user can customize the application, creating a feeling of adjustability and ownership.

4.3.4. Identification stage

Identification with emotional attachment and dependency on the application arise from orientation and incorporation. Everyday use of the application enables seamless operation and the utilization of the functionalities, leading to deeper human–technology interaction. Positive feelings and emotional attachment result from the feeling of outperforming individual capabilities through joint performance. This is reflected in the hedonic aspect of the UX models of Hassenzahl et al. (Citation2013) and Karapanos et al. (Citation2009).

In the identification stage, the FoB play a central role in deepening the previously published UX models. As the name of the stage implies, it can be considered to be the recognition phase where the user develops loyalty toward the application and, as a result, retains the application for future use. The user builds firm trust in the application and feel excited and enjoyed about using it to perform daily tasks.

4.4. Limitations and applicability of the model

In our study, we have focused on the mobile application UX domain. Although we have conducted an initial validation of the FoB model through the nine case studies, the applicability of the model in other UX contexts needs to be investigated more thoroughly. In particular, because the FoB model is new, we lack data on its real-world applications by other researchers and practitioners. Interesting questions related to the relevance and design benefits of the included FoB, as well as the procedure for identifying and defining users' feelings and deriving features for mobile services and applications remain to be answered. Moreover, the identification of FoB was based on an SLR and a formative evaluation of the model through the case application designs. As a result, a more systematic study is needed to generalize the identified FoB involved in the UX design process. Finally, there was no backward and forward literature search in the SLR, and the selected forums did not cover all forums in the areas of m-learning, mobile applications, and HCI. As a result, it is likely that more FoB will be identified in the future.

Although our SLR focused on m-learning, the proposed FoB model aims at being applicable to a wider range of mobile applications, as demonstrated by the formative evaluation covering nine mobile application design processes. Further, our study aimed to develop a model for designers´ use that could be used as a tool to facilitate positive emotional engagement; this was confirmed by the results of our SLR that resulted in all positive FoB except for frustration. The underlining idea of the model was to provide a tangible approach and tools to tackle the UX of mobile software and services already at the concept design phase. From this point of view, negative FoBs are typically not a target of the affect for mobile application's usage and experience. However, we acknowledge that negative feelings are influential in the context of UX, especially at the UX evaluation phase, and should be explored further in a future study. Furthermore, we are aware of the emerging need of an evaluation tool for assessing the levels of the FoB experienced by users. This could be done with help of a psychometric scale. However, the design and development of such a scale is beyond the scope of this study.

5. Discussion

5.1. The FoB model and other UX models

The consideration of FoB in previous UX research has been limited. Devendorf et al. (Citation2020) proposed the Design Memoirs method where designers elicit first-person emotional narratives to facilitate application or product design. They demonstrated the use of Design Memoirs by investigating what do mothers experience emotionally while using parent-focused smart gadgets and data-tracking platforms, and identified negative feelings such as rage, loss, and regret as FoB (although the term was not explicitly mentioned). The Design Memoirs method is suitable for designers who are themselves potential application users and who want to investigate the emotions and feelings related to the application usage and context. This is similar with the recommendations of the PLUX model (Karahanoğlu & Bakırlıoğlu, Citation2020), which considers users' existing mental models from a third-person perspective.

Previous UX models show how UX evolves over time, but they do not provide practical methods for incorporating FoB into the design process (Karapanos et al., Citation2009, Citation2010; Ryan et al., Citation2008). The proposed FoB model fills this gap by identifying a number of FoB associated with different stages of mobile application UX. These FoB contribute to both the hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of UX, allowing for the best in individual engagement. Our FoB model focuses on the existential feelings that are beneficial in the design, development, and use of mobile applications. The model, which was validated through an evaluation of nine mobile application design projects, aims to provide a practical approach to how design can explicitly invoke appropriate FoB at various stages of the UX life cycle (Mekler & Hornbaek, Citation2016). Our study aimed to introduce feelings and emotions as contextual features in system design, which can be systematically addressed.

The importance of emotions and feelings in UX has been investigated in various disciplines. Saariluoma and Jokinen’s (Citation2014) competence-frustration model indicates that individual problem-solving capabilities affect users' competence levels, and frustration tendency trait affects an individual’s frustration level. The model's goal is to reveal how emotions are elicited when people interact with technology. Furthermore, Saariluoma and Jokinen aimed to quantify the emotions elicited during interactions with technologies. They built the model using users' mental representations by asking them to express their emotional experiences using emotional words. They divided the expressed emotions into two groups: (i) the competence group is about positive basic emotions, such as determination, vigilance, pride, excellence, and efficacy; (ii) the frustration group is about negative emotions or negative states of mind, such as frustration, annoyance, anxiety, confusion, and struggle. Through the competence–frustration model, it is possible to define the emotional consequences, both positive and negative, associated with the use of technology. The competence-frustration model proves that emotions affect the construction of UX, and that emotions depend on many factors, including individual mental capacities.

Compared to the model presented by Karapanos et al. (Citation2010), the FoB model addresses the user's emotional experience in greater detail throughout the product's life cycle. In our model, we elaborated on various FoB that the user encounters with the application usage at different phases of the application life cycle. For example, when the user is not familiar with a product (orientation), the FoB they experience differ from those experienced when they have developed competencies (incorporation). This is aligned with the results of Saariluoma and Jokinen’s (Citation2014) study. Additionally, our model incorporates the concepts of hedonism and eudaimonia, which were not considered by Karapanos et al. (Citation2009).

Norman (Citation2004) argued that emotions assist us in making decisions by assessing situations. He classified emotions into three levels: visceral, behavioral, and reflective. The visceral emotions assist us in determining what is bad, good, safe, and dangerous. The behavioral level is unconscious and consists of routine automated operations. At the reflective level, we consciously generalize findings and transfer learning and experience to other fields. The behavioral changes depend on a variety of factors, such as perceived trust, influence, and cognitive feedback, as demonstrated by Nikou and Economides (Citation2017). Norman's model aids in the design of robust applications that aim to elicit a positive judgment from users, but it does not consider how the user's emotions and feelings evolve over the course of an application's life cycle.

Our model identified FoB that mediate and construct hedonic or eudaimonic experiences for users, as described by Hassenzahl et al. (Citation2013) in their Experience Design framework that focuses on meaningful and pleasurable experiences. As part of the discussion, they provide a conceptual tool that helps designers understand why they should focus on experiences, such as a model of an artifact consisting of both material and experiential components. Hassenzahl et al. (Citation2013) further proposed psychological needs and experience patterns as means of understanding and categorizing experiences. Moreover, concentrating solely on hedonic aspects is inadequate for doing one's best to accomplish a task meaningfully.

Ryan et al. (Citation2008) argued that living a thoughtful or reflective life is necessary for doing our best. We believe that feelings, particularly FoB, have a thoughtful and significant effect on user performance. The identified FoB assist designers in the concept design phase to emphasize the hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of the product, and facilitate user engagement in a meaningful way whilst avoiding burden or frustrations. Designers can use interactive technologies, design theories, and appropriate methodology, such as user-centered design, to create a robust, pleasurable, and meaningful applications.

The interrelationship of hedonic and eudaimonic experiences is unclear and has been debated by psychologists and philosophers. Similar ambiguous views and arguments on hedonism and eudaimonia can be found among UX scholars (Mekler & Hornbaek, Citation2016). Our model pursues to demonstrate that hedonic and eudaimonic experiences are interconnected and complement each other from the FoB perspective. As a result, we expanded on Bargas-Avila and Hornbaek’s (Citation2011) criticism on UX evaluation to include measuring enjoyment and aesthetics.

5.2. On positive and negative FoB

The development of the FoB model originates from the practical need for clear-to-apply tools for UX design in real mobile application and service development projects. Usually, the focus of development is on the aspects and features of the application/service that deliver positive UX. This aspect is illustrated in the study of Desmet (Citation2012) who demonstrated that positive emotions are a source of opportunities for designers. Therefore, the focus in the identified FoB are on the positive feelings, which can result in the improvement of the user´s cognitive performance (Iordan & Dolcos, Citation2017). Out of the 13 FoB explored in this article, only frustration addresses negative feelings in a direct way. However, even with this FoB, the aim is to keep away from the negative feeling and consider the positive aspects that avoiding this characteristic delivers for the service or application. Our assumption, which is aligned with the work of Desmet (Citation2012), is that the developers are keener on constructing and focusing on features that deliver positive experiences. This aspect was also evident in the results of our SLR: previous UX research appears to emphasize positive feelings. Therefore, for the context of this study, we considered that focusing on positive aspects will deliver broader opportunities to apply the model in practice.

Having now mentioned the emphasis on positive feelings in our current model, we acknowledge, aligned with Fokkinga and Desmet (Citation2012), the important aspects that dealing with negative feelings in design work would introduce; however, their role may be different and specific to certain application types, such as games (Mekler et al., Citation2016), that would benefit from elaboration of broader emotional range. Exploration of negative feelings (even e.g., “productive negativity”; see Gauthier and Jenkinson (Citation2018)) may support the ideation of previously uncovered surprising features and deliver interesting “out-of-the-box” insights for the design work – even though the results would not be applicable in a straightforward manner. Addressing negative feelings as an explicit part of development efforts will add to the knowledge and understanding of the interactions with the application and deliver further innovative viewpoints to address in the design and development work. Moving toward this direction, Fokkinga and Desmet (Citation2013) identified the following steps to employ negative emotions in product design from the UX perspective: First, identify the negative emotions; second, define when and how the negative emotions emerge; and third, identify the right protective frame based on the product concept.

We assume that the flexible structure of our model enables further exploration and adding of new FoB to the model. The additional FoB may well include also aspects that have a focus on negative feelings. Nevertheless, dealing with negative feelings may require different approaches in the design work and practices for the elaboration. Such aspects are yet unknown to us and require additional research. Therefore, we have left aspects relating to negative feelings outside the focus of this article.

Furthermore, we wish to point out that our aim has not been in the development of a psychometric tool for assessing the UX – even for the context of services that are under development. In our current work, we have not considered a balanced negative-positive psychometric scale of critical importance for the intended design purpose at this stage. The work of Diener et al. (Citation2010) on a scale for measuring positive and negative experiences and feelings could be a starting point toward this direction. Should there be interest towards developing a more complete and balanced assessment of the negative and positive aspects of UX, the research and development approach for designing the method should be different including proper factoring of parameters and corresponding quantitative studies with sufficient number of subjects for the studies – all in the context of FoB. Again, we acknowledge the opportunities and need for such a tool, but such development has been beyond the scope of this article.

5.3. Exploring additional feelings: adding the feeling of needs fulfilment to the FoB model

We acknowledge that our current list of FoB is not complete. Based on the nine case study application evaluations, we identified a new FoB that did not emerge in the literature survey: the feeling of needs fulfilment, which in the context of mobile application means, the application fulfils my essential needs and I can customize the application to meet my needs. This FoB connects to the feeling of adjustability as it can be facilitated by enabling adjustability and personalization of the application to match the user’s individual needs (Capuano et al., Citation2014; Du et al., Citation2006; Teklehaimanot, Citation2015). Additionally, Kraus et al. (Citation2016) identified security and privacy as essential needs for mobile applications to fulfil, and Kang and Jung (Citation2014) showed that the need of safety can be fulfilled by the smartphone, along with the need of self-actualization. Incorporation and identification are both stages that can induce the feeling of needs fulfilment. Through the application, or its integration with other features on the phone, the user gains the experience that their needs are being met. In addition, the fulfilment is among the feelings that make the application an essential part of the daily tasks.

5.4. Recommendations for using the FoB model

On the basis of our findings, we share concrete recommendations on activities in mobile application UX design related to FoB in different stages of the model.

5.4.1. Anticipation

Anticipation is about forming expectations towards an anticipated product or service. With respect to the user’s existing and forming needs and preferences, the user anticipates (explores and assesses) possible future activities with the appropriated product or service. This anticipation leads to expectations and attempts for closer familiarization with the product/service. In order to accommodate these attempts, an aim of UX design is to identify user preferences concerning the future possibilities of the application. Designers may consider the role of new emerging and intriguing approaches for interacting with the application. They may utilize users' existing mental models, metaphors, and preferences, which can be identified with a semi-structured interview. Furthermore, designers can extend the application's functionalities through user research methods to make the application more robust and easy to use (projections on potential). The FoB related to anticipation may be supported by design activities in the following way:

Feeling of trust: Make sure that the offering and the presentation of the product/service for the user is trustworthy with respect to the user’s expectations. Ensure that the system can be considered reliable and trustworthy in the user's social context (Moradi & Ahmadian, Citation2015). The feeling of trust can be elaborated in a user study by probing users about applications that they trust: what makes these applications trustworthy?

Feeling of frustration: Study and assess the current gaps in the existing application as well as the reasons for frustration through user study methods such as observation, shadowing, and semi-structured interview. Investigate the user's preferences for content presentation and application interactivities in different contexts, for example, the user’s learning preferences in m-learning (Capdeferro & Romero, Citation2012).

Feeling of excitement: Investigate novel and fresh technologies that could make the application more robust and feature rich. Determine the user’s expectations toward emerging technologies and how and what additional features and services can increase the user’s abilities) (Kaunda, Citation2013). This FoB is measurable during user evaluation of a lo-fi prototype. Personalization and customization, such as the use of human or pet-like avatars, have been shown to increase excitement in game-based applications (Asadzandi et al., Citation2020).

5.4.2. Orientation: familiarity

In the orientation stage, the aim is to study new and emerging technologies and functionalities in the hands of users. The FoB in this stage can be supported by the following activities:

Feeling of ownership: Evaluate how much the user feels that the application is tailored to their needs, and how much they are able to customize the application. The application should behave in the way the user desires and expects. It should be flexible enough for the user to make changes to the settings as needed.

Feeling of engagement: Assess and measure how the user engages with the application. This can be done for example by observing and measuring how the user attempts to use different features, and how they provide, manipulate, and share information (O’Brien & Toms, Citation2010). The designer must determine the factors that lead to the user's involvement with the application. Interactivity and engagement with the application are two types of involvement that can be measured during the usability and UX evaluation phases.

Feeling of contribution: provide ways for the user to contribute content, communicate, and develop competencies with peers and networks. Examine how the application allows the user, for example, a learner, to contribute in social settings and learning situations (Barki & Hartwick, Citation1994).

Feeling of empowerment: Study how the use of the technology may empower the user in their current way of handling tasks; e.g., the user feels that the application empowers them to do their best. Furthermore, flexibility, freedom, and extended capabilities (Hanus & Fox, Citation2015) result in an empowerment feeling.

Feeling of effectiveness: Conduct user studies to identify the existing effectiveness gaps in the current application. Investigate how to improve the user’s effectiveness by incorporating novel technology to smooth out the interactivities. Analyze the amount of cognitive load (Wang et al., Citation2018) and physical efforts expended on the application's operation (All et al., Citation2014).

Feeling of frustration: Conduct user studies to learn what frustrates users about existing systems. Analyze the frustrating factors in the new technology and application, and avoid features that frustrate users. Use appropriate technologies to make the system faster and more reliable. Analyze how the technology supports various user demands (Hazlett, Citation2003) in different contexts.

Feeling of gratification: Analyze the gratifying outcomes of users' initial explorations of the new technology and system, as well as the gratifying factors in users' contexts. Use preferred novel technologies that allow users to perform required tasks more joyfully.

5.4.3. Incorporation: functional dependency

The goal of the incorporation stage is to investigate the application's efficiency and the user's satisfaction with it. The responses of users to the application's usability should be investigated. We recommend the following design activities for the FoB in this stage:

Feeling of ownership: Evaluate users' attitudes toward the application’s proprietorship and whether the application is perceived as an integral part of their targeted activities, such as learning. Examine the user's view on application usage, benefits, and how the application reflects and expands on the user as a person (Meschtscherjakov et al., Citation2014).

Feeling of engagement: Examine how the application keeps users engaged in the process both during and between performance intervals. Evaluate how eagerly and willingly the user uses the application and its features. For example, during the user research phase, learn how the user prefers to interact with the application, such as by asking yes or no questions or by receiving quick notifications that require user action. On the basis of the context of use of the application, the engagement needs to be defined; e.g., engagement in games is different from that in learning applications.

Feeling of security: The user is confident that the application is secure. Moreover, the application interacts and performs securely with other applications on the phone. As the product matures and data can be stored and retrieved, the usability evaluation phase can assess and evaluate this feeling.

Feeling of adjustability: Investigate how the system enables users to adjust the application according to their preferences (Belk, Citation1988). Troussas et al. (Citation2020) demonstrated that personalization can increase the learning outcomes of students. In order to ensure full adaptability, it is crucial to identify and envision adaptable components of the application during the design process. Users must have the options to cancel the adaptable settings.

Feeling of enjoyment: This is an important feeling that is a result of the user’s engagement with the application. At the user study phase, the designer need to investigate and determine what users enjoy; assess how they enjoy and have fun using the application. The designer may identify users’ enjoyment preferences at the user study phase by asking, e.g., user’s favorite applications on the phone, and why and how the applications are selected. This FoB can be evaluated during the lo-fi prototype phase and again during the hi-fi prototype phase of usability and UX evaluation.

Feeling of excitement: The user feels that the application is easy to use and most of all it performs the way they want. During the user study phase, investigate users' preferences for application features and components that excite them. Furthermore, this feeling may be assessed and measured during the design process of an application.

5.4.4. Identification: emotional attachment

In the identification stage, the aim is to investigate users' attitudes toward mobile application use. Florence and Ertzberger (Citation2013) demonstrated that using mobile technology enhances user engagement, since it motivates and excites users. The emotional attachment of users to the application should be investigated. The following design activities are of use:

Feeling of security: In order to protect the user's privacy, the application's data should be encrypted, but user should be able to access them easily. A stable and constant security policy is essential for a successful application. During the usability evaluation phase, when the product is mature and data can be stored and retrieved, this feeling can be assessed and evaluated.

Feeling of trust: Make sure that the contents in the system are correct and reliable, and take precautions to avoid losing the user’ data. Ensure that the system is reliable and trustworthy in the user's social context (Moradi & Ahmadian, Citation2015). This feeling is measurable and evaluated already in the concept design phase and continues to the high-fidelity prototype's usability and user experience evaluation.

Feeling of adjustability: Users expect the application to be flexible and perform the way they want. Results and features are delivered as users would expect to see them. This feeling is measurable and evaluated during the lo-fi prototyping phase, where the focus of the evaluation is on functionality of the proposed application.

Feeling of enjoyment: In elaborating the new features, determine what users enjoy; assess how they enjoy and have fun using the application. The designer may identify users’ enjoyable preferences at the user study phase by asking, e.g., user’s favorite applications on the phone, and what are the user’s favorite applications on the phone, and why. This FoB can be evaluated during the lo-fi prototype phase and again during the hi-fi prototype phase of usability and UX evaluation.

Feeling of excitement: New applications are much anticipated by users who are eager to see if they meet their expectations. Designers should identify the features that users want in an existing application or a new application. It is possible to determine if the FoB is addressed in the concept design, for example through the construction of scenarios and storyboards.

5.5. Reflections on the FoB model usage

The following list presents our reflections on how the FoB model affected the design of the nine case application designs:

The FoB form reminded the designers to re-evaluate their app's design, including double-checking how different FoB have been incorporated in the design.

The FoB model helped the designers verify and assess how different emotional engagements can be implemented, e.g., which part of the design inspires enjoyment.

UX is already impacted during early design, not after evaluation or development of a functional prototype in the lab.

The FoB model facilitates constructing FoB through the guidelines (Supplemental Appendix B). For example, the designer may decide how and what type of FoB needs to be incorporated depending on the phase of the design process, e.g., to construct trust during the application login phase.