Abstract

Volunteer motivation has been researched in HCI in several application domains. However, motivational complexities of digital volunteerism in science-based domains, such as medical research are under-explored, especially when involving volunteers with marginalized identities. We aim to study the socio-technical complexities of voluntary participation in a digital science-based research platform and propose recommendations to enhance volunteer motivation. We describe a survey study of volunteers on Step-Up for Dementia Research platform (n = 266) to capture nuances in their demographics, experiences, motivations, well-being, and psychological needs. Our findings reveal the features that facilitate or impede sustainable volunteer participation and the 5 identities based on which volunteers derive meaning from their work. We propose 8 recommendations to navigate the digital divide and foster inclusion, build wider participation by engaging with the social construction of volunteering and focusing on prosocial values, and enhance volunteer well-being by fulfilling their cognitive, emotional, and psychological needs.

1. Introduction

Voluntary work takes many forms in the digital realm. Digital or online voluntary services are used during crisis and disasters (Starbird, Citation2011; Starbird & Palen, Citation2011), for advocacy and in civic services (Hansen et al., Citation2014; Warren et al., Citation2014), for capacity building in NGOs (Blythe & Monk, Citation2005; Morse et al., Citation2008), and more. In the last two decades, online voluntary work has additionally extended work associated with knowledge contribution. Whether it is Free Libre and Open Source Software development (FLOSS) (Gardinali, Citation2003) or online wiki creation and management platforms (Nov, Citation2007), these online voluntary workers, also known as “digital volunteers” or “online volunteers” (Naqshbandi, Liu, et al., Citation2020; Starbird, Citation2011), have organized to form thriving communities with their own collaborative practices to create and manage knowledge. The understanding and definition of digital or online volunteerism have therefore expanded to include many forms of online work. This has also provided a design impetus to understand the motivational and social complexities that emerge due to the use of digital platforms for volunteerism.

The research presented in this article explores an online platform that enables digital volunteering for the purpose of participating in scientific research. This is a specific domain of online voluntary work which involves volunteers who employ their intellectual and cognitive efforts to contribute to science. Some existing examples linking science and volunteering include citizen science where volunteers collectively work with scientists as amateur researchers toward a discovery (Nov et al., Citation2011), or science-based research platforms, such as Volunteer Science (Radford et al., Citation2016) where volunteers become research participants. These practices have been subject to research in Human-Computer Interaction (HCI), Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), and other related research communities. However, while citizen science volunteers are often viewed as co-creators of knowledge who collaborate with scientists on specific subjects and objectives of inquiry, voluntary participants in scientific studies are, by and large, themselves the subjects of research inquiry. The perceived difference in the “function” and roles of volunteers in these types of digital scientific volunteering platforms would shape volunteer motivation, engagement, and sense of well-being resulting from their volunteering. The research presented in this article explores these attributes specifically in relation to digital volunteering for science-based research, which is an under-explored area of inquiry.

Motivation, engagement, and well-being are highly interconnected, with many determinants of well-being directly or indirectly impacting engagement (Peters et al., Citation2018). Importantly, volunteering has a strong potential for contributing to meaning in life, which is also a predictor of well-being (Martela & Ryan, Citation2016; Martela et al., Citation2018). Further, volunteer identities are shown to impact their engagement and well-being (Thoits, Citation2012). Science-based research platforms, such as VolunteerScience or Project Implicit have been mostly studied from the perspective of their domain-specific scientific research findings rather than the socio-technical aspects of volunteer engagement with those platforms (Radford et al., Citation2016; Xu et al., Citation2014). Volunteer motivation, identity, and meaning-making on these science-based research platforms remain largely under-explored leaving a gap in HCI that might allow us to better support volunteer engagement in ways that are sustainable, inclusive of various markers of identity and conducive to their well-being. The research presented in this article will address this gap.

Moreover, building volunteer platforms for scientific engagement also means considering a vision of the future for our communities. There is an increased awareness about the need for improving science education and communication with the general public due to the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure people follow public health recommendations. Rather than relying solely on reactive science communication with the public which are sometimes entangled with misinformation and disinformation, there is merit in developing platforms that engage the public with science voluntarily, particularly in relation to issues that directly impact them (e.g., personal health), and their future (e.g., public health policies). To increase participation in volunteering platforms, research and development must seek to understand how we can enhance inclusivity, particularly for those who are underrepresented in scientific volunteering platforms.

In this article, we report a survey study of volunteers on an online platform for science-based research participation. The platform is called StepUp for Dementia Research and helps dementia researchers in Australia to recruit participants for their studies. We characterize those registered with this platform as volunteers because they are registered on an ongoing voluntary basis, they agree to contribute their time and knowledge and engage with the program (through various forms and activities) should they be matched with a research study, without a promise of monetary compensation for their participation. Thus, additionally, our research also seeks to reframe the traditional view of unpaid participation in science-based research as volunteerism, similar to other forms of volunteerism within other domains. Through highlighting the experiential aspects of digital volunteers on the given platform, we validate our current understanding of digital science-based research volunteerism as being the same as other forms of digital volunteerism, i.e., voluntary activities using digital technology for common good and without any financial gain. We aim to empirically explore volunteer motivations, identity and meaning by investigating their past and ongoing experiences of and expectations from voluntary roles. These factors, as we established earlier in this section, are linked to volunteer well-being. In doing so, we view both identity and meaning-making to be value-based. We explore three research questions:

R1: How do past and current experiences, motivations, needs and future expectations of volunteers in digital science-based research platforms shape their well-being?

R2: How do volunteers draw meaning from and form identities around science-based research volunteering?

R3: What design strategies can be used to improve volunteer experiences on digital platforms for science-based research?

Our survey questionnaire included both qualitative and quantitative questions, addressing volunteer demographics, their volunteering history, motivation, expectations, perceptions, and well-being. All recruited participants were registered with the volunteering platform at the time of our study. Through the analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, we contribute an empirical understanding of digital volunteerism for science-based research and highlight five volunteer identities on such platforms. We additionally elaborate opportunities for future technologies to strategise and support plurality focused and volunteer-centric design, an approach proposed in our previous work in other domains such as education and mental health (K. Naqshbandi et al., Citation2019; K. Naqshbandi, Taylor, Pillai, & Ahmadpour, Citation2021; K. Z. Naqshbandi, Liu, et al., Citation2020; K. Z. Naqshbandi, Taylor, Pillai, & Ahmadpour, Citation2020). We hope our findings inform the design of online science-based research platforms, such as StepUp for Dementia Research in the future. Finally, we hope to help researchers and organizers of science-based research programs who rely on volunteer participants to increase the diversity of their programs and remove barriers to participation for volunteers especially those with marginalized identities.

2. Background

2.1. Well-being and motivation in science-based research volunteering

There is an emerging interest in designing technology for psychological well-being and happiness, indicated by the popularity of well-being applications for mood tracking, mindfulness (Cochrane et al., Citation2021), meditation (Cochrane et al., Citation2020), journaling (Tholander & Normark, Citation2020), with many promoting long-term well-being rather than immediate gratification (Calvo & Peters, Citation2014). Along those lines, we focus our attention on volunteerism and well-being. Long-term volunteerism, specifically in a traditional face-to-face setting, is strongly associated with psychological well-being and happiness (Musick & Wilson, Citation2003). This is especially important because this impact on happiness is not subject to hedonic adaptation, making volunteerism a way forward for overcoming the “hedonic treadmill,” and building significant increments toward happiness (Binder & Freytag, Citation2013). It is therefore natural to ask how the well-being benefits of traditional volunteering can be transferred to digital environments.

In science-based research platforms, the motivations and experiences of voluntary participants may be considered secondary to that of the “actual” scientists, highlighting the need for researching strategies to support volunteers motivations and the values that they associate with their work (Rotman et al., Citation2012). In this study, we use the self-determination theory (SDT) (Deci & Ryan, Citation2002) as a lens to understand volunteer motivation. An influential theory of motivational psychology, SDT has built a strong reputation with regard to designing user experiences with desirable motivational outcomes in sports (Allen & Shaw, Citation2009), education (Park, Citation2013), gaming (Gee, Citation2012), health (Balaam et al., Citation2011), among other disciplines. SDT is generally characterized by its focus on determinants of well-being and motivation, and provides technology researchers with assessment tools and a lens to interpret experiences associated with design features that may enhance or hinder well-being (Peters et al., Citation2018). Specifically, SDT has been used for improving motivation and in the design of well-being-focused technology for volunteers, which makes it a theory relevant for this study (Naqshbandi et al., Citation2021; Naqshbandi, Liu, et al., Citation2020; Naqshbandi, Taylor, et al., Citation2020). Ryan and Deci postulated that the more self-determined the motivation of an individual toward a goal, the happier they are. They envisaged motivation as a spectrum with an increasing level of self-determination, where the lower end is (i) amotivation or lack of motivation, followed by (ii) external motivation to gain external rewards like social acceptance or maintaining a social image, (iii) introjected motivation, which is driven by self-esteem, (iv) identified motivation, where the individual identifies with a cherished value or virtue associated with the goal, (v) integrated motivation, where the individual fully endorses an external value and integrates it with their own values to derive meaning, and (vi) intrinsic motivation, where absolutely no external pressure or values are present and the individual is mainly motivated by the enjoyment associated with the goal (Deci & Ryan, Citation2002). This scale has been applied to the volunteering context successfully by Millette and Gagné (Citation2008).

The self-determination theory also examines three basic psychological needs that a goal should satisfy to fulfill its utmost well-being potential: (i) autonomy is the need to feel in charge of the goal, (ii) competence is the need to feel confident about one’s performance to achieve the goal, and (iii) relatedness is the need to feel meaningfully connected to others via the said goal (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017).

In our previous work on designing for digital volunteers, we used SDT to understand and enhance the experiences of volunteers in the medical education context (K. Z. Naqshbandi, Liu, et al., Citation2020). In the current study, we explore what roles identities volunteers consider for themselves in science-based research volunteering and the impact on their motivation and wellbeing.

Voluntary participation in science-based research is characterised by a quality that is specific to its context – the potential power imbalance between volunteers and researchers. This can have implications for volunteer motivation, well-being, and happiness. Howard and Irani (Citation2019) examined this issue in research subjects who care deeply about their participation on socio-technical platforms, such as Wikipedia, and termed them as research collaborators who shape knowledge production. However, one may argue that voluntary participants in a traditional natural science-based research setting may not enjoy the same agency as Wikipedia contributors. Particularly for scientists in medical health research or similar contexts, these participants source data as “human subjects” (Cox & McDonald, Citation2013) and may be considered “guinea pigs” to be experimented on (Howard & Irani, Citation2019). To further elucidate this, we point to a scathing passage in an editorial published in the Lancet decrying the level of autonomy in voluntary participants in medical research programs where the innocuous use of the term “volunteer” may oversimplify the motivational and ethical complexities in human participation in medical research.

One of the reasons for the richness of English language is that the meaning of some words is continuously changing. Such a word is ‘volunteer’. We may yet read in a scientific journal that an experiment was carried out with twenty volunteer mice, and that twenty other mice volunteered as controls (Poliomyelitis, Citation1952).

The above also raises ethical tensions around what “volunteering” means and how consent in medical and health research can prevent unethical practices, particularly in relation to oppressed peoples with documented grievances, such as various African and Indigenous populations (Graboyes, Citation2015). Understanding consent practices with volunteers necessitates research into the circumstances surrounding their participation including volunteer motivations and values to then eliminate the possibility of coercion (Townsend & Cox, Citation2013). Digital platforms for scientific and medical research enable volunteer recruitment and participation in scientific studies. Digital adds a layer of unknown as the volunteers’ motivations and experiences get shaped by the medium and impact their well-being and happiness in different ways. To address the nuances of volunteers’ well-being and happiness, we investigate the motivations, experiences, and expectations of volunteer digital participation in science-based research programs.

2.2. Identity and meaning-making in volunteering

Identity is an important facet of motivation that is known to contribute to an individual’s well-being (Stets & Burke, Citation2000). This has also been studied in volunteerism, where various facets of volunteer identity predict their participation and experiences (Finkelstein et al., Citation2005).

The social identity theory defines how an individual identifies oneself based on their affinity with a social group. This social identity is then invoked to various degrees in social contexts where differences in power, status, and interests are observed (Hogg & Abrams, Citation1988; Sherif, Citation1936; Tajfel et al., Citation1979). Accordingly, volunteering for any science-based program can be associated with the volunteers’ identification with the community or in-group represented by that cause. The social identity theory can explain why people engage in prosocial (helping) behaviors, such as charity and volunteering to benefit certain groups and causes (they identify with) over others (Hackel et al., Citation2017). Similarly, it has also been used to elucidate the anti-science positions of anti-vaxxers (Motta et al., Citation2021), climate change deniers (Fielding & Hornsey, Citation2016), or anti-maskers during covid-19 (Abrams et al., Citation2021) whose social identity may overwhelm their ability to accept scientific evidence.

Volunteers engage in roles they embrace by choice rather than strong beliefs in obligations, for example, toward workplaces or family. Volunteer roles and their corresponding identities help in deriving meaning in life, which consequently contributes to volunteer well-being (Thoits, Citation2012). Volunteering in many online communities involve specifically defined roles. For instance, open source communities usually have a defined hierarchy of roles, where newer members peripherally participate in small tasks at first and gradually move up to bigger roles (e.g., project leader, core member, active developer) (Ye & Kishida, Citation2003). Role identity has been positively associated with the intention to continue volunteering (Marta & Pozzi, Citation2008). In their study on motivating online volunteer contributions based on local neighborhood, Moreno et al. found that using a gamification mechanism that involves assigning roles based on volunteer perceived neighborhood identity improves volunteer engagement (Moreno et al., Citation2015). Preist et al. found that strategies that focus on generating meaning through role identity in a volunteer community encourage long-term engagement of volunteers (Preist et al., Citation2014).

Service to others and beneficence, traditionally known to be synonymous with the spirit of volunteerism, contributes to a life of meaning (Debats, Citation1999; De Vogler & Ebersole, Citation1983; Martela et al., Citation2018). Meaning in life has been explored in psychology and social sciences from phenomenological as well as empirical points of view. It is shown to have a positive impact wherein an individual feels a sense of fulfillment with respect to their life goals and is thus, strongly associated with well-being and happiness in life (Battista & Almond, Citation1973). The salience of both role identity and social identity, especially in the context of volunteering, is associated with improved motivation and engagement as well as a meaningful and happy life (Gray & Stevenson, Citation2020; Lambert et al., Citation2013; Thoits, Citation2012).

The association of identity, meaning, and motivation was observed in online science-based volunteering, where understanding and encouraging the role identities of online citizen science volunteers within a supportive community supported their motivation. This research also indicated that because of this, the volunteers learned the nuances of scientific methodology on a deeper level instead of merely a superficial understanding of science (Jennett et al., Citation2016).

Prior research studies examined the motivations and experiences of participants in online citizen science, which explored how volunteer identity factors into their engagement (Nov et al., Citation2011; Rotman et al., Citation2012). To our knowledge, similar studies are lacking in relation to digital volunteers in science-based research participation. Thus, we examine factors that are associated with science-based volunteers’ motivation, identity, and meaning-making to identify strategies for designing better digital platforms and interactions for the volunteer participants and those who recruit them.

2.3. Inclusion and well-being of the margins

Social margins is a reference to those who fall outside the various socially constructed norms and are systemically pushed to the fringe of the society (Peace, Citation2001) due to perceived differences in ethnicity, religion, race, economic level, class, ability, sexuality, gender amongst other often intersecting identifiers (Crenshaw, Citation1989). Lack of agency and power to determine the outcomes that concern one’s quality of life characterize the process of marginalization (Seeman, Citation1959). The position of margins in a society constantly evolves with the changes in the societal factors, such as technological disruption, market innovation, policy changes, and political upheaval (Vrooman & Hoff, Citation2013). The conventions that alienate marginal groups are enforced by the mainstream populace who possess privilege based on their difference from the “other” in terms of their identities, associations, environments, or experiences (Hall et al., Citation1994).

Design plays a direct role in creating or sustaining the process of marginalization, whether it is through the design of social policies (Jacobi et al., Citation2017), or digital experiences (Sin et al., Citation2021). As an example, design can include people with varied abilities, or exclude them by normalizing ableism, thus, extending marginalization (Newell et al., Citation2011). Similarly, policies and governmental processes can have a similar impact, for example, affirmative actions, such as reservations and quotas for scheduled castes and tribes in India, which intend to increase equity for historically marginal groups. We argue the potential role of design in marginalization extends and is extended by marginalization in science.

The positivist belief in the political neutrality of science has been challenged through post-modern philosophy which legitimizes many ways of knowing (as opposed to one quantified way of knowing) (Wall, Citation2006) and prioritizes equity, justice, and social responsibility in the scientific community (Rose & Rose, Citation1973). Within the field of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI), the consideration of politics of power in socio-technical processes and systems is outlined in several social emancipatory frameworks, such as the critical race theory (Ogbonnaya-Ogburu et al., Citation2020) and feminist theory (Bardzell & Bardzell, Citation2011), emphasizing the social situatedness of research and its outcomes. Moreover, these frameworks advocate for socio-technical design and research that challenges the status quo perpetuated in “engineering” or modular system thinking to critically engage with complex problems through examining context, histories, power structures, and associated praxis (Khovanskaya et al., Citation2018). Narrowing the social margins has, therefore, turned into a design approach that centers on social justice (Dombrowski et al., Citation2016), reflexivity (Rode, Citation2011), openness to collaboration and participation in research (Johnson & Crivellaro, Citation2021), and critiquing existing design practices that may perpetrate marginalization (Tran O’Leary et al., Citation2019).

Digital volunteering has digitized the many traditional ways of in-person volunteering (Amichai-Hamburger, Citation2008). However, the inequities associated with digital volunteering are increasingly visible, challenging the well-being of those involved (or left behind) even when volunteers are motivated to engage (Ackermann & Manatschal, Citation2018; Piatak et al., Citation2019). Lack of power and agency caused by marginalization is directly associated with the loss of meaning in life which also results in adverse well-being outcomes (Hommerich & Tiefenbach, Citation2018; Seeman, Citation1959). Core to examining online volunteering work is, therefore, identifying how designed platforms contribute to social equity, facilitate participation of marginalized groups, and contributing to their well-being. In science-based volunteering platforms, digitization can potentially remove barriers to participation for some marginalized groups (e.g., due to availability of transcription and language translation for linguistically diverse volunteers, accessibility features, and preserving anonymity). However, digital platforms may also hinder volunteer engagement when varied identities and capabilities of volunteers are overlooked in design. Previous research into online volunteers in a medical education platform revealed opportunities to tackle gender-based marginalization by supporting women, whose motivations are often exhausted due to a lack of redressing their emotional investment in their work (Naqshbandi et al., Citation2021). Irani et al. additionally suggest post-colonial computing as a lens to shift design and analytic practice to acknowledge cultural ways of knowing and address uneven relations in research (Irani et al., Citation2010). Through illustrative case studies, they showed how failure to do so can negatively impact knowledge produced through research and even cause harm, for instance when researchers lack understanding of the cultural beliefs of Australian Aboriginal participants (Irani et al., Citation2010).

Finally, technology design has important ethical implications for consent practices (Graboyes, Citation2015), particularly in relation to participants or volunteers from marginalized communities who have routinely endured higher risk and harm in health and science-based research (Alexander et al., Citation2003). The design process must seek insights to sustainably create social change and technology innovations for and with volunteers (Krüger et al., Citation2021). It is this kind of insight that we seek to uncover in our research, to achieve what Noble described as long-term success through engagement Noble (Citation2012) in addition to fostering digital volunteers’ well-being.

2.4. Case study-StepUp for dementia research

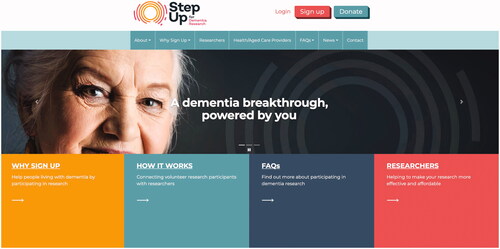

We will now describe the platform and the associated volunteer-involving program used in our case study. StepUp for Dementia Research (https://www.stepupfordementiaresearch.org.au) is an online initiative initially funded by the Australian Government Department of Health, and modeled after and partnered with a UK government program called Join Dementia Research program (see ). All associated processes, such as documentation, research participant recruitment, and handling of data are reviewed by a specially convened Governance group within the University of Sydney consisting of experts in research ethics, data protection and information governance, consumers (people living with dementia and carers), and researchers. Implementation of StepUp for Dementia Research is also approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee.

Stepup for Dementia Research program seeks to facilitate participant recruitment for dementia-related studies by matching a pool of registered adult volunteers located within Australia with appropriate dementia research studies. The researchers are affiliated with universities and research institutions across Australia. The platform includes checks and processes to ensure that the registered research programs comply with ethical standards and policies. Institutions using StepUp for Dementia Research are also required to sign a Data Access Agreement outlining policies specifically developed for the platform implementation and responsibility and accountability for the appropriate use of data by researchers.

For our research, we sought participants from the volunteers who were already registered with this platform and those who joined during the period that our study ran. Some volunteers, especially in the initial stage of recruitment, had not yet participated in any dementia research facilitated via the platform. Therefore, in our survey, we asked about their expectations for the programs and their volunteering history, both online and face-to-face. We did this to understand their motivations, values, expectations, and identities associated with volunteering and explore how their participation in science-based research contributes to their well-being. Details of the survey questions are discussed next.

3. Methods

3.1. Positionality

Author 1 is responsible for leading the project. “I am an HCI researcher and this article forms a part of my Ph.D. research. My interest in research on volunteerism did not occur by chance, but was deliberately crafted based on my own history of volunteering in a few areas of interest, both in online and traditional face-to-face environments. I have contributed as a volunteer to several scientific projects on citizen science platforms, such as Zooniverse, Galaxy Zoo, and others based on my personal amateur interests in topics, such as astronomy, literature, amongst others. So, I naturally made an effort into getting involved in this project when the opportunity arose. Additionally, several circumstances in my personal life (lived experiences of oppression due to being raised in a politically disputed region, living as a non-Anglo immigrant in a Western nation) in addition to my work associated with several vulnerable groups of people (refugees and asylum seekers, people with spinal cord injuries and neurological conditions, the homeless, among others) have brought a strong awareness of how marginalization can make people invisible and how it routinely occurs through the design of policies, processes and objects around us. The core topic, the design of the study and the lens through which I analyzed the data in this article are inspired by my own stake in the aforementioned topics.”

As a team, we are positioned at the University of Sydney. This affords us access to a wide network of researchers in HCI, Science, and Health. Our collective research on health, volunteerism, and citizen science affords us an intimate understanding of the research context. The second author is the director of StepUp for Dementia Research. Her knowledge of the program guided us in designing and disseminating our survey on their dementia research platform where volunteer participants in our study are registered with. The first and third authors have lived experiences of multiple cultures through their background (South Asian and Middle Eastern) and relocations which afforded them a lens in this study to examine participant comments on culture and marginalization. All authors were involved in the design and dissemination of the survey study. Authors 1 and 3 collaborated on data analysis and manuscript preparation. All authors collaborated on finalizing the manuscript.

3.2. Survey

Our research was approved by the ethics committee at the University of Sydney (reference number 2018/680). This research was conducted at a time when StepUp volunteers were not yet assigned to any dementia research. We chose to use an online survey as it is a fast and efficient way of collecting information from many participants. REDCap, an online survey tool was used to disseminate the survey. The participant information sheet (PIS) was integrated into the survey and shown to participants before starting the survey. Participant consent was obtained via submission of their responses. A pilot survey was tested by the research team and a few pilot participants to ensure the clarity of questions. The survey was then advertised on the StepUp for Dementia platform, after which all registered volunteers were notified about the availability of this study.

There were 22 questions in total with embedded logic and branching to the survey questions. The survey included five major sections as follows:

Demographics—Included questions about age, gender, employment status, highest level of education attainment, and ethnic background.

Volunteering history and experiences—Included seven questions about participant past and current volunteering experiences, both online and face-to-face; the time spent on their volunteering endeavors, as well as dementia-related and other kinds of volunteering. These included a combination of Yes/No questions in survey branching where the participants could choose only one option and then specify the numerical value of hours spent on different kinds of volunteering. Additionally, there was an open-ended qualitative question for further clarification.

Volunteering motivation—We used the standardized motivation rating scales by Millette and Gagné (Citation2008) to assess volunteer motivation, which included six items corresponding to six types of motivations on a spectrum i.e., intrinsic, integrated, identified, introjected, external, and amotivation. The responses to the questions were on 7-point Likert scale (7 being the highest), ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree (Millette & Gagné, Citation2008).

Volunteer well-being—The Personal Well-being Index is one of the scales used in Australian Unity Well-Being Index (Cummins et al., Citation2003) to assess volunteers’ satisfaction in life as a measure of their individual well-being (Stukas et al., Citation2016). Using the seven items on this index, we measured the satisfaction of volunteers with their standard of living, health, achievements in life, personal relationships, personal safety, community connectedness, and future security. The responses to the questions were on 7-point Likert scales (7 being the highest), ranging from strongly dissatisfied to strongly satisfied.

Perceived psychological needs satisfaction—Measured the level of needs satisfaction as perceived by the volunteers. The six items in this scale were adapted from Psychological Need Satisfaction in Exercise scale (PNSE) by Wilson et. al. and included two questions to measure each of the three SDT constructs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Wilson et al., Citation2006). The responses to the questions were on 7-point Likert scale (7 being the highest), ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

The survey contained six open-ended qualitative questions (including a final question) to obtain a nuanced understanding of volunteer experiences, expectations, identity, and meaning-making through this form of volunteering.

Please describe your most memorable experience using an online dementia research platform.

Please describe your most memorable volunteering experience for other volunteering activities. Tell us what motivates you and what your experience is like.

Please tell us the reasons you have chosen to volunteer through online means.

Please tell us about the experience of using online technology for volunteering. Feel free to elaborate on your experience as much as possible (e.g., how easy/difficult it was, what features/services appealed to you, what made you leave or come back to the website/app, or how the experience compared to other types of volunteering).

Please describe your reasons for volunteering for dementia research in your own words. Feel free to elaborate on as many factors as you like.

What could help you in using dementia research platforms in the future and make your participation easier?

While the survey scales provide a measure of volunteers perceived motivation, well-being, and psychological need satisfaction, the open-ended survey questions are designed to gain meaningful information about participant values, identities, and experiences. To be able to answer our research questions, we aim to make connections between the two forms of obtained data. For example, motivation scales provide a classification of volunteer motivation in a science-based research program which can be then compared to volunteer motivations in other programs, such as education programs (Naqshbandi et al., Citation2021). We hope that by making such connections and comparisons, we can provide directions for designing better volunteer experiences on similar platforms in the future.

3.3. Data analysis

Data was collected over a period of 10 months starting from October 2019 to August 2020. The qualitative data provided deep insights into participants’ volunteering on StepUp for Dementia Research and in general. Complementing the qualitative data was the quantitative data collected through rating scales, which established measures of participant well-being, motivations, and expectations, adding more nuance to the overall findings. All quantitative survey data was analyzed using SPSS and Microsoft Excel. The analysis included summary statistics of measures in the five sections of the survey. For reporting the scores of the standardized scales which included the volunteer motivation scale, well-being scale, and perceived psychological needs scale, we used medians instead of mean, due to the asymmetry of data. We also performed a non-parametric correlation analysis to understand how investment in volunteering (hours of volunteering) is linked to types of motivation, psychological needs satisfaction, and perceived well-being. Descriptive analysis of volunteer demographics and volunteering history aimed to make visible potential issues of diversity and group representation. Together, the knowledge produced reveals several avenues for understanding and improving volunteers motivation and well-being. The findings from quantitative analysis were then paralleled with qualitative findings through thematic analysis, to elucidate what the volunteer experiences and expectations entail, highlighting their motivations and needs, answering RQ1. Additionally, we located several volunteer identities based on how they draw meaning from their participation to answer RQ2.

A thematic analysis was performed based on an inductive (bottom-up) approach following the 6-steps outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006): (i) gaining familiarity with the data; (ii) generating initial codes or labels; (iii) searching for themes or main ideas; (iv) reviewing themes or main ideas; (v) defining and naming themes or main ideas; and (vi) producing the report. The codes and labels were first generated by the first author, then reviewed together with the third author before refining and finalizing the themes together. It took a total of four rounds of analysis to finalize the codes and the resultant themes.

In the initial round of thematic analysis, we analyzed the responses to each qualitative question separately using a bottom-up analysis. After two rounds of thematic analysis, we found that there was a notable overlap in the codes and themes generated across the responses to the six questions. For instance, the codes “Family relevance,” “Personal relevance,” and “Helping others,” amongst others were repeated in all questions. Therefore, we found it more insightful to merge all the responses to create a holistic understanding of the experiences, expectations, and values of the volunteers. Therefore, our final themes represent responses to all open-ended questions.

Several codes and themes we identified reference the practicalities in the form of enablers and impediments surrounding volunteering work of the participants. As an example, we identified codes, such as “provide variety of participation options,” “Lower the barrier for participation,” and “Time-based flexibility” where participants expressed a desire for having more flexibility in terms of the technology, applications, and time to be able to volunteer regularly. This was categorized under “Flexibility in participation” theme. Importantly, this type of finding shows that science-based volunteering can be paralleled with other forms of digital volunteering, such as on education focused platforms in our previous work where volunteers desired flexible platforms to balance volunteering and non-voluntary commitments and roles (K. Z. Naqshbandi, Liu, et al., Citation2020). This is important because our study is among the first studies to frame and term participation in scientific inquiry through digital platforms, such as volunteering. The implication of this finding is the wealth of design strategies that can be then used to enhance science-based volunteering. These are later discussed to answer RQ3.

Finally, codes that captured volunteer identities based on their values highlight how they derive meaning through volunteering work. For such codes, the latent meaning was interpreted by the first author based on the underlying values and concepts. For instance, the codes “collaborate with others,” “meet others with similar experiences,” and “build a community with others” were interpreted to surface volunteers desire for connections and characterize an identity labeled “I connect with others.”

To address the two broad groups of themes mentioned above, we finalized the themes along the lines of participation enablers and impediments and volunteer identities. We will describe these themes interspersed with quotes from the participants in the next section.

4. Results

A total of 307 submissions were recorded. Out of these, 266 submissions were complete and used for analysis. We will detail the descriptive analysis followed by the thematic analysis.

4.1. Demographics

The average age of the participants was 61.15 years and the median age was 64. shows the frequency distribution of the participants’ age groups.

Table 1. Age distribution of the participants.

In terms of gender, 77.4% of the participants self-reported as females and 22.6% as males. None of the participants selected “other” for gender. It should be noted that participants were given the option to specify their gender identity in a text field if they chose “other.”

In terms of ethnicity, most of the participants identified themselves as English (57%), followed by Irish (12.7%) and Scottish (12.4%). shows the frequency and percentage distribution of the ethnicity of the participants.

Table 2. Ethnicity distribution of the participants.

Some (n = 58) participants specified their self-identified ethnicity, out of which 24 included variations of Anglo-Australian, 20 more used European and other ethnic identifiers commonly associated with the Global North, such as Swiss, Welsh, Spanish, Slovenian, and Canadian. The remaining 34 participants specified ethnicity associated with the Global South, such as Zimbabwean, Colombian, Indian, and Taiwanese.

Participants specified the highest level of education attainment post-graduate (30%), followed by bachelors (27.4%) and diploma (17.7%). shows the frequency and percentage distribution of the education attainment of the participants.

Table 3. Distribution of the highest level of education attainment of the respondents.

In terms of employment status, a majority of the respondents were retired (51%), followed by employed (40.6%) and other (5.3%). shows the frequency and percentage distribution of the employment status of the respondents.

Table 4. Distribution of the employment status of the respondents.

4.2. Volunteering history and engagement metrics

In total, 32 (12%) of the 266 participants had a history of prior or ongoing participation in dementia research supported by various online platforms. In addition to StepUp for Dementia Research, examples include research platforms, such as the Healthy Brain project (https://www.healthybrainproject.org.au/), Maintain your Brain (https://www.maintainyourbrain.org/) and online courses (MOOCs) to learn about dementia and dementia research, such as the one supported by the university of Tasmania (https://www.utas.edu.au/wicking/preventing-dementia). Participants reported spending an average of 11.3 hr (SD = 27.25) and median = 2 hr on online dementia research in the last 12 months. Some 114 (57%) participants performed other forms of volunteering (either online or face-to-face) for an average of 157.45 hr (SD = 274.80) and median = 60 hr in the last 12 months. Out of these 114 participants, 41 (15.4%) reported having used technology, such as a website or an app for volunteering.

4.3. Volunteer motivation scale

On a 7-point Likert scale where 7 indicated the highest level of motivation and 1 indicated the lowest, participants reported high levels of intrinsic (Mdn = 6), integrated (Mdn = 7), and identified (Mdn = 6) motivations, while as moderate to low levels of introjected (Mdn = 3), external social motivations (Mdn = 2), and amotivation (Mdn = 1).

4.4. Well-being scale

On a 7-point Likert scale where 7 indicated the highest level of satisfaction with domains of subjective well-being and 1 indicated the lowest, participants reported high levels of well-being measures in all aspects of their lives specified on the 7-point rating scales; standard of living (Mdn = 6), health (Mdn = 6), achieving in life (Mdn = 6), personal relationships (Mdn = 6), safety (Mdn = 6), feeling a part of the community (Mdn = 6), and future security (Mdn = 6).

4.5. Perceived psychological needs satisfaction scale

On a 7-point Likert scale where 7 indicated the highest fulfillment of perceived psychological needs and 1 indicated the lowest, participants reported high levels of perceived satisfaction with the fulfillment of their psychological needs of competence (Mdn = 6), autonomy (Mdn = 7), and relatedness (Mdn = 6).

4.6. Correlations

To explore associations between various variables in our survey, we used Spearman’s rho non-parametric correlation analysis. For the sake of brevity and specificity, we will discuss only the significant correlations between motivation, well-being, perceived psychological needs, and hours of volunteering which will help us explore associations of well-being with experiences, motivations, and needs of volunteers as mentioned in our first research question (RQ1).

Results of a bivariate Spearman correlation indicated significant strong positive correlations between integrated motivation and autonomy [r(266) = .224**, p = .0001], integrated motivation and competence [r(266) = .185**, p = .002], integrated motivation and relatedness [r(266) = .295**, p = .0001], integrated motivation and well-being [r(266) = .224**, p = .0001], intrinsic motivation and autonomy [r(266) = 0.179**, p = .003], intrinsic motivation and competence [r(266) = 0.162**, p = .008], intrinsic motivation and relatedness [r(266) = .305**, p = .0001], identified motivation and relatedness [r(266) = .282**, p = .0001], well-being and autonomy [r(266) = .227**, p = .0001], well-being and competence [r(266) = .242**, p = .0001], hours of volunteering and intrinsic motivation [r(152) = 0.225, p = .005], and hours of volunteering and identified motivation [r(152) = 0.231, p = .004]. Findings showed a significant positive correlation between intrinsic motivation and well-being [r(266) = 0.134*, p = .029], and relatedness and well-being [r(266) = 148*, p = .016].

Significant negative correlations were observed between amotivation and relatedness [r(266) = −0.149*, p = .015], introjected motivation and competence [r(266) = −.132*, p = .031], external-social motivation and competence [r(266) = −.123*, p = .045], and amotivation and autonomy [r(266) = −0.123*, p = .046]. shows the correlation matrix displaying correlations between hours of volunteering motivations, well-being, and perceived need satisfaction.

Table 5. Correlations for hours of volunteering, motivations, well-being, and perceived need satisfaction of the participants.

4.7. Thematic analysis

A total of 805 qualitative response statements were generated from the 266 participants of the survey. Responding to the qualitative questions was optional, not every participant answered these qualitative questions. As a result, the total number of response statements is not the same as the total number of participants. Additionally, some questions were more readily answered or resulted in richer response statements, helping with conceptualizing nuanced themes. For instance, there were 269 very nuanced response statements for question five about the reasons for volunteering in dementia research, mostly pointing to the importance of family and the volunteers’ desire to contribute to future generations as important motives. shows a summary of the number and frequency of overall responses as well as responses to each question. The extensive responses and the rich and illustrative accounts of volunteer experiences that were generously shared by our participants provided a highly nuanced set of data that allowed us to identify the enablers and impediments surrounding volunteer participation as well as the current volunteer identities based on meanings derived through volunteering.

Table 6. Table showing the number of response statements for each question, average length of those response statements (displayed as word count), the standard deviation of those response statement length, and the minimum length and maximum length of responses statements for each question.

4.7.1. Participation enablers and impediments

4.7.1.1. Flexibility in participation

Participants acknowledged technology has expanded their volunteering opportunities in terms of contribution, learning, integration of operations, ease of organizing action, and reducing cost and efforts. The flexibility made their experiences engaging and was mentioned as an expectation as well. This included being able to choose what kind of technology they use for participation. “A phone call or Skype call or using Zoom for focus groups would suit me best as I’m working.” P71. “I do not have a camera for online chats so other electronic communication through forums, message boards, or messenger services would help greatly.” P166. Tasks that had a low barrier to participation, i.e., did not require too much one-off investment were preferred. “Shorter burst to fit in with my busy life.” P234. Finally, flexibility in time, both in terms of duration of the tasks as well as being able to choose the time of participation, were considered conducive to their participation. “Flexible time commitments as I work, have teenagers and my available time fluctuates.” P24. “Great to filter amount of time willing to volunteer[…]” P21. Volunteers also asked for flexibility and consideration of their time and efforts in hybrid volunteering, especially, when travel is involved. “Some type of compensation for my time would be ideal. I am happy to volunteer, but I can’t afford to pay for transport/parking, etc. I would love to get another job but at the moment I have undiagnosed health issues that hinder my ability to work long hours.” P126

4.7.1.2. Clear information and communication

Participants suggested that minimizing ambiguity in information and communication improves their motivation. This may be even more important in science-based research that follows a rigid protocol to maintain data quality and research integrity. Participants referred to aspects of user experience, such as easy access to help and learnability, as well as communication aspect of volunteering platforms, such as notifications about upcoming or existing volunteering opportunities. “If they can email me of any new study with ample notice. I just finished this and another survey but when I received the deadline was over. I tried and managed to get through.” P301. Participants also desired adequate notice or reminder for each volunteering opportunity “I just need notice, I’m a full time student working part time as a nurse plus caring for my mum. If I can get adequate notice of upcoming events/surveys/testings I just need to be able to lock it in early. I want to be as of much assistance as possible.” P286. “All I require is a week or two warning for any activity.” P210. This also extended to access to diverse promotional channels to inform potential suitable volunteers. “I actively searched for a way to help with dementia research and found you. Other people might be happy to be involved but not know about you.” P155. This could involve expanding the mediums of communication to reach a wider pool of potential volunteers. “Last time I was a research participant I accidentally heard about it on the radio[…]” P166.

Finally, participants specified adequate information about the research protocol including how their data or specimen was collected and stored, “[…] I would like to have known more about the data storage plans (i.e., how safe is it, how long do you store my data, etc.). As a general public, there is uncertainty in regards to the data/biological samples collected, and this is a deciding factor for me whether to participate or not- especially if I was giving confidential information.” [sic] P295

4.7.1.3. Impact of digital divide

The results provide a lens into the many ways that the participants are digitally marginalized, highlighting the potential for addressing the digital divide in science-based volunteering platforms. Some participants wished for better technology and internet “A good NBN [National Broadband Network] connection, but I guess that will be one of those things outside your and my circles of influence.)” P31. Other participants expressed frustration over challenges to perform online tasks because of their limited technological abilities. “My computer literacy is very limited. Before I can complete this survey I have great difficulty in opening the link[…]” P233.

Many of the registered volunteers with the program are older adults (see for age distribution of participants). Participants noted the impact of age on their technology use. “Not complex digital, older people not as at ease with apps, etc.” [sic] P29. A few participants found their various physical and cognitive disabilities impede their technology use. “To get someone else to do it [volunteering tasks] for me because I can’t write and read anymore.” P32; “Please note that most people with dementia don’t check emails regularly[…] The concept of information being held online is not useful for us[…] And self-service is the same as no service I’m afraid.” P283.

Several participants reported the impact of geography on participation. “Distance will always be an issue, but people living in rural remote [areas] have unique issues that should be included in research.” P279. Finally, participants felt less motivated to participate in online science-based volunteering when they faced a lack of understanding of their culture and values particularly relating to non-Western and non-Anglo cultures. “I had a negative experience with a survey on aging and diet, because the platform did not accommodate non-European ways of eating[…] Research projects that do not presume an Anglo cultural background [participant’s suggestion for improvement].” P68.

4.7.2. Volunteer identities and meaning-making

In total, five types of identities were identified. These are summarized in , where for each identity, we provide a descriptive archetype (e.g., I am a learner), a description of how meaning was generated and attributed to that identity followed by exemplifying quotes from participants. These are described as follows.

Table 7. Table showing volunteer identities, how volunteers derive meaning from volunteering and corresponding quotes from participants supporting those identities.

4.7.2.1. I am a learner

Participants suggested they volunteer to learn new things that help them grow intellectually. “I find this area of understanding of what happens to the mind extremely interesting and would like to understand it better.” P121. Some were happy with being a research participant as long as it helped them learn, “more time to involve myself in projects I find interesting, i.e., conservation and human health without being the one to take responsibility for successful completion of a study or project - just being a ‘participant’ and gaining some knowledge about my own health[.]” P132. They also mentioned other dimensions of growth through participation based on their past and current experiences, concerns, as well as their perceived identity. “Some of my younger relatives have suffered from dementia, and I have already been diagnosed as having a Mild Cognitive Impairment, so I would like to gain as much insight as I can about new initiatives and theories about the treatment of, and prevention of, dementia.” P110. “I participated in a tape recording in Chinese language re elder abuse information which will be launched by the Government. I am a member of the Northern Settlement Group which supports the retired Chinese migrants in Newcastle[…] It was challenging but good experience.” [sic] P233. Participants mentioned how volunteering helped them use their existing skills or keep their minds active and gain confidence. “I have a health sciences background and am ageing myself. I like to keep up to date and find ways to age gracefully.” P50. This aspect especially stood out as a motive after significant life events, such as retirement “Being a Board Member and suggesting ways to update the methods of contacting the members. I enjoy being in the ‘workforce’ again.” P134; or having been diagnosed with cognitive impairment “Being included even post-dementia diagnosis… I’m motivated by using the talents I still have left” P103.

4.7.2.2. I create impact

Participants desired “making a difference” P102 or “giving back to the community” P72. They achieved this by investing in programs that they deemed worthwhile, such as nature conservation projects like “repairing bushland” P113, research projects, such as “health and well-being” P19; or by helping the disadvantaged communities, such as refugees, “Working for ‘Case’ where we helped Afghan refugees prepare for DIMEA [Department of Immigration and Indigenous Affairs] interviews.” P14; Australian First Nations people, “Working with First Nations people to try to recover some of their stolen wages. I never had my wages stolen.” P292, those who are incarcerated, “Kairos Prison Ministry: when we go most weeks to spend time with them singing, listening to a talk and discussing, to see the appreciation and change in the women’s lives is rewarding for me[…]” P291, amongst many others.

Participants expressed satisfaction knowing that felt the impact of their work, via some indicators, such as “seeing joy on others’ faces” P170, seeing “an important organization grow” P50, or receiving “feedback from the researcher/organization” P103. Participants also mentioned how helping elevated them personally, “A warm and fuzzy feeling that I’ve made someone’s day, that I’ve helped the planet, just made the world a better place for one teeny, tiny moment.” P209. It improved their sense of self-worth and made participants feel needed, “I am motivated by the feelings that come from giving. A personal and ongoing sense of worth that comes from sharing.” P123. “We enjoy doing this as it gets us out and helps my self-esteem, it give me a purpose.” P163. Conversely, lack of appreciation was termed as “emotionally draining” P206 and could possibly lead to volunteer disengagement.

4.7.2.3. I connect with others

Our participants expressed interest in collaborating with other volunteers based on their shared interests, “It’s great to be with like minded people helping a cause that matters.” P274. Connecting with others over shared experiences, such as dementia diagnosis or caring for relatives with dementia was meaningful to participants, where volunteering helped the participants to “meet others in the same boat” P94. Additionally, participants wished to get to know the researchers who they perceived to be in a position of authority, suggesting that the researchers should build confidence and trust with them “Answering questions from researchers who seem to know what they are doing” P60. Importantly, participants desired to build a community that included the researchers. “Maybe an annual event where participants could network with the researchers would be a nice way to build community.” P148.

4.7.2.4. I build on familiarity

Volunteers were keen to learn new things via their roles, but at the same time, they mentioned how the inspiration or pathway for volunteering came from already existing and familiar social institutions. Some of these were selected because they were within the participants’ comfort zone. This included work, “I have worked as an Occupational therapist for many years in aged care and the last few years specifically with people who have dementia.” P21; and education, “I am a medical student with a strong interest in neurology and I find the lack of hope for people with neurodegenerative disorders, due to lack of disease modifying therapy, absolutely outrageous. I want to play whatever part I can in fixing this.” P196. Other participants identified with social institutions that were a source of support for them. These included family as a pathway for volunteering, whether it was volunteering for children’s schools, clubs, programs, “Volunteering as a Cub Scout leader - it was hard work!” P24; or volunteering because they witnessed their family member go through a health challenge, “Father has Lewy Body Dementia. As the child of someone with dementia, I believe I should be involved in dementia research.” P15. Some participants engaged in faith-inspired volunteering, “I visit the residents at the local Aged Care facility, I help out at Scope and I assist at a Community Kitchen. I am motivated by a Christian faith and a desire to help others.” P250. Among this group of participants, some mentioned their faith-based institution helped to facilitate volunteering, “We held a cake store organized though my church to help raise money for leukemia.” P107. Thus, using familiar social institutions that the volunteers identify with seems to play a role in adding meaning to their lives.

4.7.2.5. I care about my legacy

Many participants volunteered to know that their work would not necessarily benefit anyone from their own generation, “Motivation for me, is more about planting the tree that I will not enjoy the shade of. It’s not about accolades or certificates or badges, never has. It’s about informing and educating for the future.” P33. Many mentioned they want their work to “help future generations” P1. Participants referred to motivation to contribute to “science” P67, “medical science” P200, or a community they identified with. In a way, they wanted their volunteering to transcend time and build a legacy. Often, but not always, the comments that suggested caring for their legacy were accompanied by participants recalling some traumatic event that occurred in their lives, such as them or their loved ones getting afflicted with neurodegenerative disorders. Voluntary participation in science-based research seemed to provide catharsis for participants by helping them understand the science behind their personal experiences. Participants viewed this as taking proactive steps toward finding a solution for others who share that experience in the future. This helped participants construct something positive from adverse events in their lives and extend their legacy.

5. Discussion

Our study revealed that science-based volunteering is nuanced and complex, with motivations beyond simply advancing science. In this section, we discuss our findings in relation to volunteer motivations, needs, future expectations, and well-being (RQ1). This is achieved by examining the measures based on well-being, motivation, and psychological needs satisfaction scales and putting them in the context of participant comments and their demographics. Further, our thematic analysis presented earlier uncovered the identities based on participant values and motivations through which volunteers derive meaning from their work (RQ2). While these identities do not serve as an assessment tool, such as those provided in theories like SDT, they allow us to conceptualize the design and ideate design strategies for science-based research volunteering platforms. Accordingly, throughout the discussion section, we specify how understanding the above can help improve volunteer engagement and experiences with digital platforms for science-based research. We then propose a set of recommendations and design strategies (RQ3). For example, our research findings suggest many older adult participants have the desire and ability to contribute to science-based research and even learn new things through their volunteering. Yet, despite their cognitive resources, their participation is impeded by the digital divide or barriers to the inclusion of linguistic needs, cultural values, and identities. We further explore our findings in this section to show the importance of recognizing that privileged and marginalized identities in volunteers can exist side by side. Finally, we propose how future research can be tailored to capture more diverse voices through better study design, e.g., by considering resources for participation by proxy. The first three discussion sections correspond to the first three subsections in our related work, to emphasize our empirical contribution to the existing knowledge. The final section of our discussion presents a summary of eight design strategies to enhance volunteer experience and well-being on science-based research platforms.

5.1. Mapping the divide

Our thematic analysis shows that participants were aware of a notable digital divide in science-based volunteering. The digital divide is the varied use of technological resources demarcated along socio-economic lines (Gunkel, Citation2003) that lead to disadvantaging some user groups. Further, research on this topic suggests that exclusion can be linked to many domains. The Australian digital inclusion index outlines the digital divide for people in Australia due to (i) access to internet, technology, data; (ii) affordability; and (iii) digital ability which includes attitudes, capabilities, and skills (Wilson et al., Citation2019). The ways that some participants felt excluded (outlined in section 4.6.1) also confer with the categories specified in this index.

The findings also show that the demographic data is highly skewed toward participants from an Anglo background, a majority of them females, retired, and highly educated. Participants were aware of the limited cultural diversity and commented on the lack of representation of cultures and values of non-Anglo volunteers in scientific studies. Recent research also points to the lack of cultural diversity in dementia research in general, and specifically dementia research on online platforms (Jeon et al., Citation2021). Jeon and colleagues noted that communities, such as Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who would benefit from dementia research, given the high prevalence of dementia in these communities, remain significantly underrepresented in online platforms. This was true for many other culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities as well (Jeon et al., Citation2021). While comments on cultural disparities in our survey responses were not frequent, we note this may demonstrate a self-selection bias where disengaged groups do not participate in research on science-based platforms and therefore their needs and values do not surface in research findings. This could be considered a limitation in our study, which we aim to address in the future through engaging with the participant cohort in more reflexive and participatory ways and creating safe spaces for a diverse group of (potential) volunteers. We propose that online volunteering platforms would benefit from such plurality-focused considerations.

A major issue that arises specifically for culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) online volunteers is the issue of science communication and translating scientific concepts. While language has been mentioned as a barrier to inclusivity in online volunteering (Cravens, Citation2006), it becomes even more pronounced in science-based research volunteering. English, being the current International Language of Science (ELIS), encapsulates complicated cerebral concepts in unique ways that might not readily exist (or have been developed yet) in other languages (Tardy, Citation2004). This may result in a knowledge gap due to inadequate vocabulary to capture research concepts. For instance, in their research on medical ethics in Eastern Africa, Graboyle captures medical researchers’ quandary with a not-so-hypothetical scenario where they have to translate concepts, such as “experimental medicine” into Swahili language. (Graboyes, Citation2015). The issue also extends to field-specific vocabulary which might be challenging to understand even in the English language. For instance, in our previous research on a volunteering platform for medical education-focused volunteers found medical student assessment to be ambiguous and difficult to understand because of the specialized vocabulary and pedagogical terminology used in the assessment rubric (Naqshbandi, Liu, et al., Citation2020). This issue would be potentially compounded for volunteers with intersectional and marginalized identities, e.g., volunteers with limited technology skills as well as English language communication skills.

Our finding highlighted the importance of enhancing information and communication for engaging volunteers. This would result in clear and unambiguous communication that improves volunteer experience in general, but more specifically it could improve the experiences of those who have accessibility and other specific needs as was indicated by many participants. Based on our findings, design strategies could focus on having regular desired notifications or reminders with ample notice for when a new relevant opportunity is available. It could also focus on providing information when needed (e.g., “FAQs” option), and tailoring the learnability of the platform to suit the demographics, e.g., by adequate training and onboarding mechanisms.

Ambiguous communication and lack of culturally and linguistically diverse options can also deter engagement for those who are underrepresented on digital research platforms, such as many CALD groups as indicated in our findings. Previous research has shown that many culturally marginalized groups are varied in participating in science-based research volunteering because of the harm caused through the research process when their specimen, data, or artifacts are used without their consent (Scharff et al., Citation2010). To address this issue in the design of online platforms, we suggest building more language options in the volunteering platforms which could help with adequate clarification of the research protocol for these participants. In addition to providing language options, strategies that include language accessibility features, e.g., translation and definition would be useful in this regard. Additionally, language support options that involve getting help from skilled staff in addition to “Help” and “FAQs” features could be useful.

Our findings confirm volunteers in science-based research programs intimately experience challenges outlined by the latest Australian Digital Inclusion Index which highlighted a steep divide between rural vs. non-rural Australians due to issues of internet access, infrastructure, and geographic remoteness (Wilson et al., Citation2019). In general, this issue is also relevant to volunteer participation in the Global South and places where inadequate or restricted access to technology, infrastructure, and resources could be a barrier. Possible solutions may lie in improving flexibility of participation by providing a range of technological options and channels, and the time and duration of volunteering. This is also important to accommodate volunteering with the other priorities and circumstances (work, family, health, accessibility, etc.), thus making volunteering more accessible to a wider range of people in life as was mentioned by some volunteers. Based on our findings, design strategies include increasing the options for technology, such as allowing a variety of devices, and applications. Flexibility in terms of scheduling the volunteer tasks (e.g., flexibility in booking appointments) and duration of the volunteer tasks (e.g., breaking volunteer work into smaller tasks) is also desirable. Mapping the digital divide could also require providing a choice to volunteer face-to-face or digitally, thus providing flexibility by using a hybrid volunteering model. An important aspect of approaching this issue is to acknowledge that over-reliance on digital solutions may not always suit the populations that we want to include in such volunteering endeavors. Therefore, socio-technical investigations should allow alternate ways of being and knowing where the resultant solutions focus on the people rather than the technology (Milan, Citation2020).

Our experience in conducting the study also touched upon the importance of supporting proxies for participants that may not be able to perform the research tasks independently on their own. Some participants required assistance to perform research tasks for a variety of reasons, such as their old age, physical mobility issues, and neurological or neurodegenerative disabilities. The contact researcher (first author) received a few enquiries from relatives of potential survey participants about this issue. While working with proxies has received much attention in medical research (Overton et al., Citation2013; Sugarman et al., Citation2007), we focus on the socio-technical aspect of it. Dai and Moffat have outlined guidelines for socio-technical research with proxies in dementia care, including careful consideration from research design to data interpretation to avoid proxies overshadowing the voices of the vulnerable participant (Dai & Moffatt, Citation2021). For our study, we faced a few challenges. First, we did not have the resources to support proxy participants. Further, our research design and ethics approval did not extend to including responses completed by proxy participants. Finally, our data collection was completed in 2020 after the COVID-19 pandemic hit, resulting in limited opportunities to meet with participants face-to-face. Thus, we had to turn down those requests. We recommend these considerations for improving inclusivity in future research involving similar socio-technical systems and research participants who may need proxies to assist with research task completion.

5.2. When social is personal: Construction of a “good” identity

Data obtained through the motivational scales in our survey shows that participants regard their volunteering participation as good social conduct. Integrated and identified motivations that are linked to prosocial values in volunteering (Grant, Citation2007; Naqshbandi, Liu, et al., Citation2020), scored very high, with integrated motivation scoring higher than even intrinsic motivation. However, the thematic analysis revealed that values that focus on benefiting the self frequently accompanied those that focus on benefiting others. For instance, the desire to benefit others was often paired with the immediate and larger concern for one’s own health and family. Participants frequently mentioned “doing good,” “giving back,” and “making a difference,” which are expressions commonly associated with prosocial behavior, such as volunteering and charity (D’Archangelo, Citation2009; Germann Molz, Citation2017). While it is meaningful to capture the perspective of the volunteer, the volunteer’s social circles (e.g., family, work, school), and the organizations/platforms that facilitate volunteering, it is also important to understand the wider social construction of volunteering. This construction is shaped by the various altruistic notions surrounding volunteering and charity work and linked to socio-political and moral discourses that situate volunteering as a culturally and socially valuable act (Evans & Lewis, Citation2018).

As an example, the government social policies in many countries, such as Australia (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australian Government, Citation2021; Department of Social Services, Australian Government, Citation2021) and the UK (Holmes, Citation2009; Hutchison & Ockenden, Citation2008) promote volunteerism through civic engagement discourses. Likewise, the altruistic aspects of volunteering are highly regarded in several religious traditions, such as “the Good Samaritan” in the Christian tradition, “Sadaqah” in Muslim tradition, “Seva” in Sikh tradition, and more. Many of our survey participants also self-identified with some form of higher calling as their inspiration or pathway to volunteering, some based on interest (passionate about “science,” “medical science”) and others based on religion (service to “God,” “Church”). We propose that by understanding these wider social discourses and capturing how they contribute to the values and motivations of volunteers, we can improve volunteer engagement and experience in science-based programs. For instance, some of our participants lamented not knowing online science-based research volunteering programs that may interest them. Broadening the promotion and communication channels for such programs and reaching out to and involving institutions that help shape the volunteers’ identities and motivations, such as religious institutions, and value-based non-governmental organisations, may be useful. The lack of inclusiveness of identity-shaping entities and values, specifically those concerning faith, religion and spirituality in HCI with respect to the design of volunteering platforms has been noted in our previous work (Naqshbandi, Mah, & Ahmadpour, Citation2022). Strategies on highlighting collaborations with relevant institutions, people, and influencers in promotional campaigns for the volunteering program as well as within the platform could help indicate involvement and build trust, thus, attracting potential volunteers.

5.3. Well-being of science-based research volunteers