African women have been at the forefront of resistance to corporate globalization since neoliberalism struck in the 1980s. They are joined, on an expanding scale, by diverse women of all continents who have also been deeply engaged in ecofeminist politics of resistance (Shiva Citation2008; Gago and Aguilar Citation2018; Giacomini et al. Citation2018). These resistance politics have today converged in the politics of transition to a fossil-fuel-free world. Being more fully and directly reliant on nature for their daily subsistence, specific African women have faced and resisted enclosure of their commons and collectively maintained indigenous knowledge, seeds, practices, food production, and energy technologies that offer clear alternatives to oil and petro-chemical reliant food and energy systems. The prominence of women in defending the commons against commodification has been evident in Africa for many decades. It is now also evident globally.

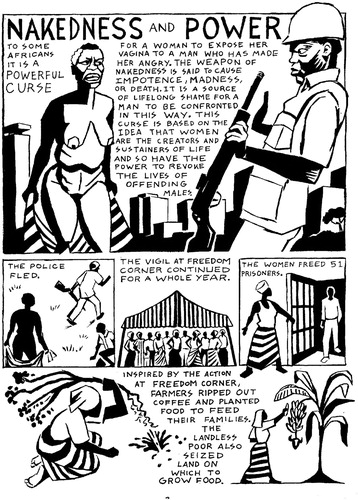

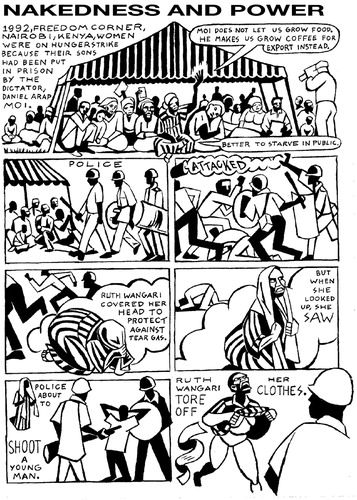

In Kenya in the mid-1980s peasant women coffee farmers refused to be bound into global coffee supply chains under conditions of debt and penury. They affirmed, instead, self-provisioning along with the revitalization of subsistence food systems and producer-controlled local and regional trade. and illustrate Kenyan grandmothers’ non-violent civil disobedience against dictatorship and extractive capitalism in the 1990s. We characterize this heightened class struggle as a “fight for fertility,” at the center of which is women and their allies’ effort to regain and defend their control over the prerequisites of life, especially their own bodies, labors, waters, and lands (Tobocman et al. Citation2004).

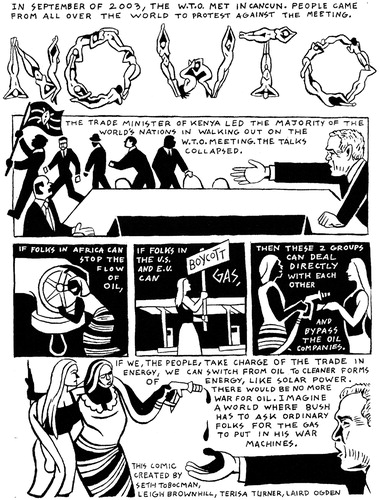

Figure 1. First page of the nine-page graphic narrative, Nakedness and Power, which first appeared in World War 3 Illustrated in 2004, with art by Seth Tobocman, text by Terisa E. Turner and Leigh Brownhill, and ink by Laird Ogden. The comic was selected by Harvey Pekar and Anne Elizabeth Moore as one of the Best American Comics of 2006 (Tobocman, Turner, and Brownhill 2006).

By the late 1990s a new generation of Kenyan activists was engaged in land occupations across the country to bring land into the hands of the poor (Brownhill, Kaara, and Turner Citation1997; Turner and Brownhill Citation2001a, Citation2001b). By the 2010s a globally-networked food sovereignty movement had emerged in East Africa, for example within the small-and-medium scale farmer movement, La Via Campesina. There activists pursued, on a widening scale, the same goals as did the farmers who ripped out coffee trees and planted indigenous bananas and vegetables thirty years before. They also linked food sovereignty to articulations of women’s human rights and to renewable energy potential in this solar-rich part of the world (Brownhill, Kaara, and Turner Citation2016; Merino Citation2017; Otieno Citation2018).

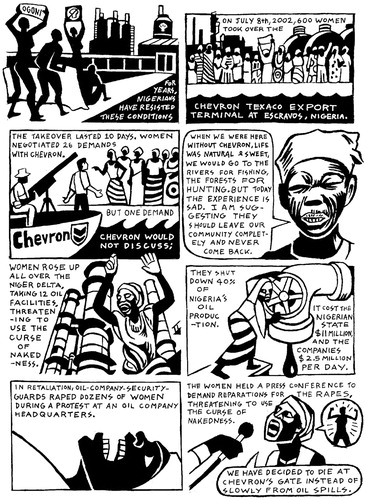

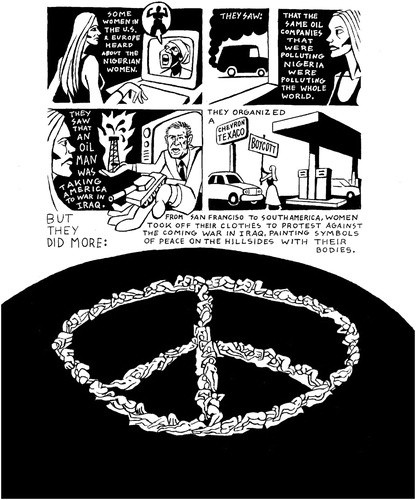

In Nigeria in the early 2000s peasant women continued their earlier struggle of the 1980s and 1990s despite harsh retribution by the state.Footnote1 Across the Niger Delta multi-ethnic women mobilized to stop oil production and the devastation wrought by continuous oil spills and massive gas flares. Their 2002 occupation of Chevron’s Escravos oil export terminal, oil platforms, oil fields, and oil flow stations took place in a context of two global consumer boycotts of Exxon and Chevron-Texaco. These mobilizations segued into unprecedentedly large worldwide protests against George Bush’s 2003 war for oil in Iraq (Turner and Brownhill Citation2004). and illustrate the “globalization from below” of the anti-oil movement that emanated from and was directly reflective of Niger Delta women’s campaigns as well as their tactic of naked protest. By 2019 a new generation of Nigerian environmental activists had taken up the struggles of their mothers’ generation. As sea levels rise and droughts encroach, they confront Big Oil with action for “system change, not climate change,” through food sovereignty, agroecology, and community based renewable energy (Bassey Citation2016).

Two crucial elements of the transition to a carbon-balanced epoch – food and energy sovereignty – were pioneered by African peasant women and their allies.Footnote2 These campaigns have now been taken up by social movements, community-based organizations and activists around the world. African peasant women’s activism, in particular, has revealed the prominence that participants give to replacing the broken, exploitative, and unjust capitalist system that their civil disobedience has aimed to destroy (Federici and Richards Citation2018).

The anti-export crop movement in East Africa and the anti-oil struggle in Nigeria both began as gendered struggles against capitalist resource-grabs. The legacy of this activism can be seen in the widespread and globally-networked food and energy sovereignty initiatives of the generations that followed. This progression characterizes a turning point, around 2016, in global social movement activism. Social movements internationally are, since Standing Rock, increasingly converging “from below” on a global scale in a common cause. These are convergences that, on the one hand, resist the rising fascism of the “force field” of the capital relation (Kovel Citation2002), and, in particular, resist capital’s collapsing “male deals” (Turner Citation1994, 20).Footnote3 On the other hand, social movements seek to actively replace capitalism with an alternative political economy. This alternative, being creatively pursued by alliances among the exploited (with women at the fore), can be characterized as a global, horizontal, subsistence-oriented, decolonized commoning political economy, or what we call “ecofeminist ecosocialism.”

illustrates the theme of “resist and replace” with reference to Big Oil. It portrays the mobilization of a global simultaneous “production-consumption strike” against particular oil companies in 2002–2003 and the potential that these strikes open up for direct deals between producers and consumers.

Figure 5. Last page of Nakedness and Power. Ending fossil capitalism requires bringing the alternative world into being, in part by building direct deals within “commoners’ value chains.”

Exploited African women’s diverse forms of activism further constitute refusals to produce labor power and the cheap wage goods that sustain labor power for fossil capital. In struggling against exploitation within coffee and oil commodity value chains, peasant women have also sought to regain control over their own time, labor, and lives. In other words, they seek not to produce labor power and commodities for capital, but rather to create freely associating people with access to and democratic stewardship over the prerequisites of life (McMurtry Citation2001; Kovel Citation2017; Brown Citation2019). In this transformational pursuit they are joined by allies worldwide, including Indigenous women of Idle No More and Standing Rock, as well as activists of Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, and the #TimesUp movements.

When 600 Nigerian women occupied Chevron-Texaco’s Escravos export terminal in July 2002, very few people outside of the Niger Delta were considering the idea of keeping oil in the ground. This demand was first articulated by Accion Ecologica in Kyoto in 1997 (Bond Citation2008). By 2019 “Keep It in the Ground” was a widely-used slogan in ecological and climate justice movements globally (Giacomini and Turner Citation2015). It is also being enacted, at least in part, by governments that are divesting from fossil fuels, from New York City to Ireland and beyond (McKibben Citation2018; WECAN n.d). In April 2002 Costa Rica became the first country to declare itself a no-go-zone for oil and gas exploration and production. By 2018 Costa Ricans had gone further in their efforts to “break free” from “the fossil path” and build a “fossil-free” economy (Araya Citation2018). Today Indigenous, Asian, and African activists also posit “Water Is Life,” “Soil Not Oil” and “Fish Not Oil.” In the face of destruction by the extractive industries these activists protect both the intrinsic value of nature in its own right and its use value for the subsistence of people and all species.

The trajectory of “gendered, ethnicized class struggle” reviewed here characterizes a praxis of revolutionary ecofeminism which is at the heart of ecosocialism. This praxis is evident in the convergence of global popular struggles that both resist capitalist extractivism and strengthen commoning alternatives that will carry humanity into a post-fossil age. Alliances of solidarityFootnote4 with the exploited women and children at the forefront of today’s social movements will strengthen humanity’s capacities to navigate this transition.

Notes

1 Niger Delta women have been militant activists against oil companies for decades. In the 1980s they used the curse of nakedness in protests against Panocean and other multinational oil companies (Turner and Oshare Citation1994), but news hardly reached the world in that pre-internet era. Ken Saro-Wiwa was an ardent and vocal champion of their cause and became a popular face of the movement for environmental justice in Nigeria in the 1990s. Along with eight other men who were together known as the “Ogoni 9,” Saro-Wiwa was executed by hanging on November 10, 1995, having faced trumped up charges and trial in a secret military tribunal (Turner, Brownhill, and Goldstein Citation1999).

2 As descendents of European settlers in North America, we have in our research, teaching, writing, activism, and in our families, sought to act as decolonizing allies in these struggles to overcome the gendered and racialized divisions imposed by capital’s global “hierarchy of labor power,” with the aim of eliminating the class line that binds the (waged and unwaged) working class into the capital relation (more on this in footnote below).

3 By male deal we mean the historically-structured cross-class collaboration uniting capitalist men and those dispossessed men who are thereby most privileged in the hierarchy of labor power (Marx Citation1867, ch. 14) for their mutual though unequal benefit (Turner Citation1994, 20–21). The partner to the deal from the dispossessed class agrees to help capitalists extract profit from those lower down in the hierarchy of labor power: the largely unwaged Black and Indigenous men and women, as well as white women and “more-than-human nature” (McMahon forthcoming). The crisis of capital in 2007–2008, and the threat of a new financial crisis in 2019, involve, centrally, the collapse of the capitalist male deal (e.g. many men’s loss of the guarantee of steady, well-paid employment). Because the male deal culturally and economically binds men’s interests to those of their bosses, the collapse of the male deal threatens capital’s control over working class men as well as over the unwaged, exploited class fractions below them in the hierarchy of labor power. This collapse and its threat to capital’s hold on the hierarchy of labor power explain much of the rise of fascism and its anti-woman, anti-immigrant, anti-nature, racist, militarist, and pro-extractivist expressions. Capitalists try to retain control by sowing deeper divisions and overtly privileging the well-being of able-bodied, working-age, cisgender, moneyed white men over all others in the global hierarchy of labor power. A measure of change today is men's widening rejection of the sexist and racist male deal, reaching deep into mainstream culture, as in Gillette's January 2019 ad campaign.

4 A particularly powerful example of such solidarity in action can be seen in the 2002–2003 production-consumption strikes reviewed above. These simultaneous, cross-border, joint actions to break capitalist value chains (Alimahomed-Wilson and Ness Citation2018) are prefigurative, peaceful actions that highlight peoples’ power and suggest lines of future development for solidarity and transition struggles worldwide. One example:

Earth Strike is planning to ‘organize worldwide actions, culminating in a global strike’ [on September 27, 2019] with a key demand of ‘unambiguous and binding agreements’ that would halve carbon net emissions by 2030 and achieve zero net emissions by 2050. (Patterson Citation2018)

References

- Alimahomed-Wilson, Jake, and Immanuel Ness, eds. 2018. Choke Points: Logistic Workers Disrupting the Global Supply Chain. London: Pluto.

- Araya, Monica. 2018. “Fossil-Free Costa Rica: How One Country Is Pursuing Decarbonization Despite Global Inaction.” Democracy Now!, December 13. https://www.democracynow.org/2018/12/13/fossil_free_costa_rica_how_one.

- Bassey, Nnimmo. 2016. Oil Politics: Echoes of Ecological Wars. Montreal: Daraja Press. (See also Health of Mother Earth Foundation, https://www.homef.org/)..

- Bond, Patrick. 2008. “The State of the Global Carbon Trade Debate.” Capitalism Nature Socialism 19 (4): 89–106. doi: 10.1080/10455750802575810

- Brown, Jenny. 2019. Birth Strike: The Hidden Fight Over Women’s Work. Oakland: PM Press.

- Brownhill, Leigh S., Wahu M. Kaara, and Terisa E. Turner. 1997. “Gender Relations and Sustainable Agriculture: Rural Women’s Resistance to Structural Adjustment in Kenya.” Canadian Woman Studies/Les Cahiers de la Femme 17 (2): 40–44.

- Brownhill, Leigh, Wahu M. Kaara, and Terisa E. Turner. 2016. “Building Food Sovereignty through Ecofeminism in Kenya: From Export to Local Agricultural Value Chains.” Canadian Woman Studies 31 (1/2): 106–112.

- Crass, Chris. 2013. Towards Collective Liberation: Anti-Racist Organizing, Feminist Praxis, and Movement Building Strategy. Oakland: PM Press.

- Federici, Silvia, and Jill Richards. 2018. “Every Woman is a Working Woman.” Boston Review, Interview, December 19. http://bostonreview.net/print-issues-gender-sexuality/silvia-federici-jill-richards-every-woman-working-woman.

- Gago, Verónica, and Raquel Gutiérrez Aguilar. 2018. “Women Rising in Defense of Life.” NACLA Report on the Americas 50 (4): 364–368. doi: 10.1080/10714839.2018.1550978

- Giacomini, Terran, and Terisa E. Turner. 2015. “The 2014 People’s Climate March and Flood Wall Street Civil Disobedience: Making the Transition to a Post-Fossil Capitalist, Commoning Civilization.” Capitalism Nature Socialism 26 (2): 27–45. doi: 10.1080/10455752.2014.1002804

- Giacomini, Terran, Terisa E. Turner, Ana Isla, and Leigh Brownhill. 2018. “Ecofeminism Against Capitalism and for the Commons.” Capitalism Nature Socialism 29 (1): 1–6. doi: 10.1080/10455752.2018.1429221

- Kovel, Joel. 2002. Enemy of Nature: The End of Capitalism or the End of the World? London: Zed Press.

- Kovel, Joel. 2017. The Lost Traveler’s Dream: A Memoir. Brooklyn: Autonomedia.

- Marx, Karl. 1867 (1967). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume One. New York: International Publishers.

- McKibben, Bill. 2018. “At Last, Divestment is Hitting the Fossil Fuel Industry Where it Hurts.” The Guardian, December 16. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/dec/16/divestment-fossil-fuel-industry-trillions-dollars-investments-carbon.

- McMahon, Martha. Forthcoming. “Farmed and Dangerous: Sheep and the Politics of Nature.” Capitalism Nature Socialism.

- McMurtry, John. 2001. “The Life-Ground, the Civil Commons and the Corporate Male Gang.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies (Special Issue Gender, Feminism and the Civil Commons) XXII: 819–854. doi: 10.1080/02255189.2001.9669944

- Merino, Jessica. 2017. “Women Speak: Ruth Nyambura Insists On A Feminist Political Ecology.” Ms. Magazine Blog, November 15. http://msmagazine.com/blog/2017/11/15/women-speak-ruth-nyambura-feminist-political-ecology/.

- Otieno, David Calleb. 2018. “Ignore IMF Reform Package and Stop Repaying Debts.” Committee on the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt, August 19. http://www.cadtm.org/Kenya-Should-Ignore-IMF-Reform-Package-and-Stop-Repaying-Debts.

- Patterson, Brent. 2018. “Climate Justice Movements Multiply as 2030 Climate Deadline Looms.” rabble.ca Blog, December 4. http://rabble.ca/blogs/bloggers/brent-patterson/2018/12/climate-justice-movements-multiply-2030-climate-deadline.

- Shiva, Vandana. 2008. Soil Not Oil: Environmental Justice in an Age of Climate Crisis. London: Zed Books.

- Tobocman, Seth, Terisa E. Turner, and Leigh Brownhill. 2006. “Nakedness and Power.” In Best American Comics 2006, edited by Harvey Pekar, and Anne Elizabeth Moore, 203–211. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Tobocman, Seth, Terisa E. Turner, Leigh Brownhill, and Laird Ogden. 2004. “Nakedness and Power.” World War 3 Illustrated 35: 55–63.

- Turner, Terisa E. 1994. “Rastafari and the New Society: Caribbean and East African Feminist Roots of a Popular Movement to Reclaim the Earthly Commons.” In Arise Ye Mighty People! Gender, Class and Race in Popular Struggles, edited by Terisa E. Turner, 9–56. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

- Turner, Terisa E., and Leigh S. Brownhill. 2001a. Gender, Feminism and the Civil Commons. Special Issue of Canadian Journal of Development Studies XXII.

- Turner, Terisa E., and Leigh S. Brownhill. 2001b. “African Jubilee: Mau Mau Resurgence and the Fight for Fertility in Kenya, 1986–2002.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies (Special Issue Gender, Feminism and the Civil Commons) XXII: 1037–1088. doi: 10.1080/02255189.2001.9669954

- Turner, Terisa E., and Leigh Brownhill. 2004. “‘Why Women are at War with Chevron’: Nigerian Subsistence Struggles Against the International Oil Industry.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 39 (2/3): 63–93. doi: 10.1177/0021909604048251

- Turner, Terisa E., Leigh Brownhill, and Jonathan Goldstein. 1999. “Life in (S)Hell.” World War 3 Illustrated 27: 21–27.

- Turner, Terisa E., and M. O. Oshare. 1994. “Women’s Uprisings Against the Nigerian Oil Industry in the 1980s.” In Arise Ye Mighty People! Gender, Class and Race in Popular Struggles, edited by Terisa E. Turner, 123–160. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

- WECAN (Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network). n.d. “Rising for Fossil Fuel Divestment and a Just Transition to Renewable Energy.” https://wecaninternational.org/pages/wecan-divest.